ABSTRACT

Participatory processes are a democratic tool in the field of cultural heritage, but what happens when the whole process revolves around a set of expert premises? How symbolic and authoritative would such participation be? This article will reflect on the dynamics of citizen participation and the power of institutional narratives focused on urban cultural heritage. Thus, this work proposes a methodological review and discussion through a case study where citizen participation is addressed as a process within the service of citizens: the refurbishment and design of new spaces within La Model prison complex in Barcelona. The aim is to explore whether institutionalised participation continues to be a symbolic tool that supports the authorised heritage discourses or if, conversely, it is enabling the embodiment of the multivocality of the stakeholders involved in the heritage management process in an effective way. This study concludes with a discussion that invites cultural heritage researchers to reflect on the difficulties involved in organising less-authorised proposals in the field of cultural heritage management.

1. Introduction

Cultural heritage, its discourses, and experiences of inclusiveness and enjoyment play a relevant role in urban dynamics, providing opportunities to improve, among other aspects, strategies of social cohesion linked, in many cases, to the social value of heritage (Jones Citation2017). This heritage is understood as a dynamic cultural process (Smith Citation2006), an assemblage of tangible and intangible features that is transformed as society evolves, in some cases by re-signifying urban heritage spaces and giving new uses and discourses to objects, traditions, or buildings (Lesh Citation2022). However, the dynamics of enhancement, reuse, and management of those urban heritage sites are not always carried out in a participatory way (Colomer Citation2021), as proposed by the Faro Convention (Council of Europe Citation2005). Furthermore, if this participation takes place through a process, it is not always linked to effective community sovereignty. In this article we propose to analyse, from a methodological, reflexive, and critical perspective, what discursive dynamics are at play in participatory processes related to urban cultural heritage in the city of Barcelona. In particular, we have chosen a contested heritage site, La ModelFootnote1 prison in Barcelona (Fontova Citation2010), since the conservation of some of its structures has been decided through a recent participatory process which has been very well documented both at the level of the process itself and its results. Although this location is a place whose history of repression has been linked to many types of prisoners and historical moments (de Miguel and Martin Citation2023), the discourses addressed as part of its remembrance do not fully take into account this facet of contested heritage milieu (Hammami Citation2016), as occurs with other re-signified prisons at different sites across the world and in Spain (Borges Citation2021; McAtackney Citation2014).Footnote2 Nevertheless, this case will lead to a new exploration of how the asymmetries or inequalities of power related to authorised heritage discourses (Smith Citation2006) operate in participatory processes where citizenship apparently takes responsibility on the local agendas (Colomer Citation2023), resulting in an endorsement of the authorities’ desires (Sánchez-Carretero and Roura-Expósito Citation2021) and conferring a symbolic character to these bottom-up practices.

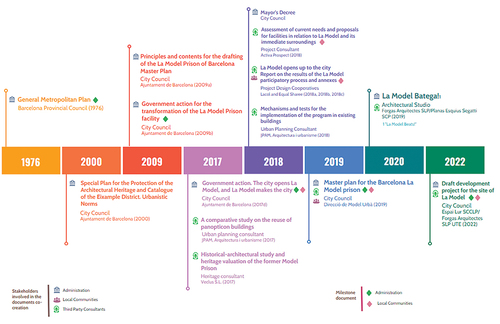

This article highlights how participatory processes in cultural heritage can become unintentional spaces for silencing voices and endorsing authorised heritage discourses. This work explores how a well-structured process for citizen participation is instead driven towards a narrow heritage discourse determined by the authorities. We achieve this through a deep analysis of the documentation generated and derived from the participatory process (see ). Thus, following a robust contextual and methodological examination of the process applied to the transformation of La Model prison (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2009a; Ajuntament de Barcelona, Citation2009b), we explore which participatory tools and strategies promote proactive approaches for heritage management co-creation. Hereafter, the discussion section describes the nature of what we call symbolic or authorised participation within decision-making processes applied to cultural heritage, a concept that connects to a series of reflections on the role and the challenges we face as experts when it comes to contesting our own authoritative heritage discourses.

1.1. The Barcelona of the shared sovereignty

The city of Barcelona has a long tradition of grassroots and associative movements involved, in a variety of forms, in the management of social and cultural spaces at a local level (Parés Citation2017). diagram, 2018: ‘La Modelo’ needs to be changed to ‘La Model’ Under the broad umbrella of citizen participation, the municipal government began to recognise and institutionalise participatory processes at the beginning of the new democratic era in the late 1970s, and increasingly during the 1980s (Casellas Citation2016). In 1985, the decentralisation of the local government into neighbourhood councils began, facilities with mixed governance were opened, and the first regulations for citizen participation were published (Andreu Acebal Citation2015). In the post-Olympic Barcelona of the early 1990s, this new participatory policy underwent a process of bureaucratisation, which developed notably after the financial crisis of 2008 (Flores Lucero Citation2020). After some years of institutional back and forth, the 2011 anti-austerity movements brought the vindication of the public against a mercantilist municipal managerial model; peppered with a series of critiques on the possible tokenism of the existing participatory model (Blanco and Gomà Citation2002; Collado Calle Citation2015). During the 2015 municipal elections, the parties that emerged from the ‘Indignados’ movement, best known as the 15 M, were victorious in cities such as Barcelona and Madrid and, consequently, direct democracies, community self-management (cooperativism), and urban commons became part of local governance (Blanco, Salazar, and Bianchi Citation2020). It is within this political context that a renewal of the dynamics of participatory municipal governance in Barcelona took place, of which La Model’s process is a major example.

In 2016, a year after winning the elections, the newly formed Barcelona City Council approved the creation of the ‘Directorate for Active Democracy Services’Footnote3 (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2017b), whose mandate is to produce and facilitate processes, channels, and tools to promote the active role of citizens and the effective implementation of participation in the city. This involves strengthening citizen initiative in proposing, determining, and deciding local interest processes while expanding the delegation of power to municipal districts. Three strategic lines are also established: participatory budgets, diverse participation programmes, and community management of municipal common goods (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2017a, Citation2017d). Ultimately, a system – or architecture of participation – is designed wherein participation is understood ‘not as a set of spaces where to report on government actionsFootnote4 at city or district level, but as a set of institutional actions that aim to redistribute resources (economic, political, symbolic, and cultural) and a change in power relations to consolidate and guarantee municipal democracy’ (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2017d, 11). In 2022, the ‘Citizen Participation Regulation’ was renewed, strengthening existing channels and committing to new initiatives such as the aforementioned participatory budgets, generating a space for citizens to also intervene in economic issues (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2022).Footnote5

2. A brief context of participation and power in cultural heritage

Participation and power are recurrent dichotomies in the field of cultural heritage, but their commodification can result in ‘favouring the exclusion of the subaltern actors of heritage’ (Roura-Expósito Citation2019, 95). This means an omission of multivocal discourses in favour of a series of monolithic and biased narratives (Hanson et al. Citation2022), with the addition of a distasteful endorsement by the community. Local policy expert José Manuel Ruano points out these biases when he indicates that, on the one hand, they are due to the asymmetry between participating actors and, on the other, to the inequality of technical knowledge about decision-making processes, which leads to the exclusion of the most vulnerable groups (Citation2010). All of this raises the question of how to make fairer cultural heritage participatory processes and how to contextualise what the outlines and limits of this participation are (Bonet i Martí Citation2012; Colomer Citation2023). In recent times, local governments have promoted citizen initiatives and community participation, however, the plurality of voices in this shared governance in the urban environment and its egalitarian context can be widely questioned (Ganuza, Baiocchi, and Summers Citation2016; Herzt Citation2015). For instance, not everyone is able to participate and sometimes these processes are organised for endorsement and consultation rather than decision-making. In addition, every participatory process involves ‘non-participants’ due to a series of intersectional inequalities that are primarily shaped by gender, ethnicity, social class, or level of education (Freire Citation1970), as well as technical skills or access to technology (Folguera Citation2007), resulting in not everyone being able to access those spaces for negotiation (Eichler Citation2021).

In 1969, Sherry R. Arstein conceptualised the ‘ladder of participation’ and argued that participation ‘can do no harm to anyone’, since it is theoretically the ‘cornerstone’ of democracy (Citation1969, 216). The author placed ‘symbolic participations’ linked to tokenism practices at the centre of her analysis. This means a symbolic inclusion of minority group voices in the participatory ritual, which essentially enables endorsement of power-holder discourses while stating that all parties were consulted and involved in the decision-making process (Arnstein Citation1969). Extrapolated to the field of cultural heritage, those participants could be described as ‘authorised participations’, meaning a symbolic way of participating in heritage decisions (Colomer Citation2021). In those cases, citizens are invited and able to participate, but their dialogues and starting points for debate will be provided in documents shaped by expert voices, including those of scholars and practitioners (Pastor Pérez Citation2019). Those symbolic or authorised participations, which other authors also describe as cynical consultations (Ruiz-Blanch and Muñoz-Albadalejo Citation2019), rather than discussing co-created new proposals, in fact encourage an endorsement of cultural heritage top-down initiatives. In addition, such authorised participations promote a sense of unique and proactive co-creation, which motivates participants to feel that they are an essential and active part of the decision-making process (Pastor Pérez et al. Citation2021). This sense of proactiveness can become a poison dart that not only supports politicised or authorised decisions but also those arising from expert academic discourses (Pastor Pérez and Ruiz Martínez Citation2021), doubly phagocytising social demands and achievements at both the practical and academic levels (Grosfoguel Citation2016).

Participatory processes in Barcelona are currently exploring ways of democratising participation through different strategies such as making changes to sessions and timetables (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2018c), or the use of evaluation procedures that aim to improve the plurality and diversity of participants (Spora Consulta Social Citation2019). Although these measures mitigate social inequalities in heritage participation workshops, if the topics and resources used in these workshops convey an authorised heritage discourse (Smith Citation2006), how symbolic would such participation be? In multicultural societies due to immigration, the diversity of voices is reduced by a series of factors such as participant availability, economic and employment stability, (dis)trust in political institutions, the degree of rootedness or belonging, knowledge – or lack thereof – of local social and political networks, and, above all, limitations in the linguistic knowledge of the host society to enable the effective articulation of political ideas and opinions (Bueker Citation2005; Crowley Citation2001; Quintelier Citation2009). As mentioned above, a range of inequalities based on gender, ethnicity, social class, educational attainment, and technical skills hamper diverse participation (Folguera Citation2007). Therefore, how can we propose a multivocal, plural, and realistic intersectional participation where the communities of interest are able to be truly heard? The recent Spanish ratification of the Faro Convention in June 2022 (Council of Europe Citation2005), showed that participatory strategies for cultural heritage management need to be put in place, but their implementation should be in a critical format that generates an innovative and dialogic space for negotiation linked to effective participation (Martí et al. Citation2016).

In the following pages, different discourses generated by administrations and associations or individuals will be contrasted through the projective analysis of documents linked to the participatory process of La Model prison, focusing on the heritage and memory section. The intention is to dissect the strategies that are considered effective in terms of real participation and how these can be diluted and help validate political decisions that convey an expert and politicised discourse (Smith Citation2006), and consequently an authorised participation.

3. The transformation process of La Model prison

The transformation of La Model prison (2017–2019) () was a milestone in Barcelona City Council’s participation programmes since, for the first time in the new government, it included a detailed study of the development of the process itself (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018b, Citation2018c). This process, as we shall see, is closely linked to social demands and is supported and articulated by a compendium of documents that we have analysed and summarised in the following roadmap (see ). We have included the stakeholders involved in the generation of the different manuscripts: administration, local communities, and experts. As a result of the document analysis, we have also indicated which of these documents are considered milestones for both the administration and the local communities, and which will be mentioned at different times throughout this section. The roadmap includes both legal actions and discussion documents produced by different companies that have collaborated with the municipality and, in turn, worked with the local communities. This has been the main source of this work, as well as an exploratory analysis of the physical environment on several occasions in 2017, 2020, and 2023.

Figure 1. La Model prison complex. Picture taken from Josep Tarradellas street (Barcelona). April 2023. Ana Pastor.

3.1. La Model as a piece of local history

La Model is a penitentiary building that has accompanied Barcelona’s contemporary social and political history since its inauguration in 1904, until its closure in June 2017. Its construction began in 1887 and applied the architectural renovation ideas of Jeremy Bentham, who established a new model of penitentiary authority and discipline with the panopticon prison (Schofield Citation2009). Due to progressive overcrowding, La Model began to abandon its exemplary character and it became an uncontrollable penitentiary facility. In addition, during Franco’s dictatorship (1939–1977), it was also used as a place of political repression. Consequently, Barcelona’s La Model became a reference point for the enforcement of such repression, and at the same time a fortress of anti-Franco and Catalan nationalist political vindication. After the political amnesty of 1977, the history of La Model continued to be characterised by overcrowding, facility malfunction, hunger strikes, self-injury, and violent riots (Fontova Citation2010). The 1980s were the prison’s hardest years, when heroin and HIV were added to the list of grievances. During this period, La Model acquired a cinematographic character, dubbed the ‘quinqui phenomenon’, as its walls housed famous delinquents involved in robberies and thefts that made it to the big screen (González del Pozo Citation2020). All of this demonstrates the inexorable process of degradation that led the authorities to decide to close the prison in 1984, although it took three more decades for this to take effect. It was only in 2017 that the final prisoner was released, and ownership of the building was passed into the hands of the municipality.

Since the 1970s, the restoration of La Model as an open urban space has been supported by a long-term neighbourhood campaign to claim both the land and the buildings for public and cultural use (Comisión Provincial de Urbanismo de Barcelona Citation1976). As can be seen in , in 2009, after a period of institutional stagnation, two fundamental documents were published: ‘Principles and contents for the drafting of the La Model prison of Barcelona Master Plan’ (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2009b), and ‘Government action for the transformation of the La Model prison facility’ (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2009a). These documents form the basis of the subsequent ‘Government Action: The city opens to La Model and La Model makes the city’ (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2017c), a strategic plan to finally change the uses of the space after the closure of the prison in June 2017 (). This action is an important milestone at both the social and political levels of the process, as it adapts 2009’s previous Master Plan of uses, while maintaining the four pillars that defined it: green spaces, social housing, heritage and memory, and public facilities (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2009b). The document specifies that this update of uses must be carried out through a participatory process, according to the guidelines stipulated for such procedures by Barcelona City Council (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2017a). However, the narrative is very rigid about preserving some architectural features, such as the panopticon building, or the recommendation of the demolition of adjoining buildings such as the workshop areas; moreover, it does not appear that the memory section is part of the participatory process. This leads us to consider that the participatory process embodies a heritage-authorised discourse intention that situates the agency of the process in the expert sphere and not in the citizenry, as we will explore in the next section. The document also sets out the creation of a memorial space for the interpretation of repression and social movements (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2017c), where exhibitions, seminars, courses, conferences, and other cultural activities would be programmed (), however it is not clear whose memories and discourses will be used, and if they will represent the multivocality of the narratives and the intangible values of the site.

3.2. Examining La Model’s participatory process on heritage and memory

From March to July 2018, a participatory process managed by the expert cooperatives Lacol and Equal Saree was launched to reach a common agreement around the re-use of La Model’s spaces for educational and housing facilities, green space, and the inclusion of a memorial site. Our analysis will focus on the specific participatory process named ‘Heritage and Memory’, as it was the only workshop, of the three organised, that was dedicated to cultural heritage issues. The questions discussed intended to define which structures should be preserved in terms of their historical relevance or significance, and where the new Memorial Site should be located. The latter was hosted by a ‘Commissioner for Memory Programmes’, an organisation belonging to the ‘Democratic Memorial Department’ of the City Council, that is, an expert administration agent.

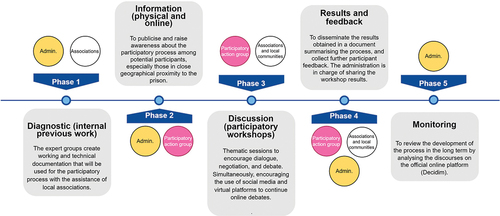

From a methodological point of view, the participatory process was divided into five distinct phases (): internal previous work, information, discussion, feedback, and monitoring. These phases were carried out by different stakeholders: the administration (in charge of commissioning expert reports), a participatory action group formed by the union of the Lacol and Equal Saree cooperatives (also commissioned by the administration but with a certain autonomy in the organisation of the participatory process and the neighbourhood), and local and cultural associations that comprise the organised society for the resignification of La Model. The main recipients of the participatory process can be named ‘local communities’, understood as the whole society and not only the organised groups for the recovery of the space.

The initial diagnostic phase was carried out at an internal level by the ‘Driving and Follow-up Group’Footnote6 composed of more than 28 organisations, including neighbourhood associations and City Council members with expertise in cultural heritage (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018c, 4). The strategy to build up the core documents to negotiate in the workshops involved a breakdown of the criteria already proposed in the 2009 master plan (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2009b), and a compilation of technical reports made by experts for covering the different topics of debate (see year 2017): 1) architectural heritage (Veclus S.L. Citation2017); 2) re-use of panopticon spaces (JPAM arquitectura & Urbanisme Citation2017); 3) neighbourhood facilities (Actíva Prospect Citation2018); and 4) green zones (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018b, 209). It can be argued that during the elaboration of these working documents, citizen participation was limited to the members of the aforementioned associations and organisations.

To encourage ‘plural participation’, as their facilitators call it, a series of advertisements on social networks such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, and the City Council (Decidim) and La Model websites, was organised, in conjunction with open-day sessions. These actions, which took place in both the digital and printed press, served to improve the visibility of the process and increase participation; also playing a key role in the latter phases of sharing results and monitoring outcomes. The documents were openly shared through the City Council’s online ‘Decidim’ platform and remain accessible to all citizens. Like we already mentioned above, the discussion workshops were structured around three different topics: 1) heritage, memory, and conservation of buildings; 2) facilities and social housing: prioritisation and location of facilities, and 3) green space and characteristics of public space. A fourth workshop was scheduled for a final discussion about a compendium of proposals. The workshops were conducted in accordance with the Barcelona City Council’s participation regulations (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2017b), which state that ‘participation must be accompanied by the empowerment of the people who participate’ (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018b, 5), mentioning that the participants are active subjects who contribute to a real transformation of the environments since they are the ones who inhabit them. This plural or real participation is based on a series of guidelines: 1) a series of ‘open days’ with an onsite guide; 2) specific approaches to each social collective and individual situation, including visual and audiovisual impairments, and care of minors or care-dependent people; 3) activities with targeted audiences such as teenagers and children; 4) flexible schedules adapted to the requirements of attendees, and 5) the duplication of workshops in order to increase the number of participants. For the results sharing and feedback phase, the participatory facilitators, reflecting on the degree of citizen consensus for each proposal discussed in the workshops (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018a, 12–20), produced a series of documents that synthesised the information gathered in the discussions (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2018c). These documents are extremely helpful in exploring the narratives that have formed across the process and in reviewing the community’s role throughout it.

As part of the ‘Heritage and Memory’ workshop – which was the first to take place and had the least participation – there was a debate over the maintenance of older structures and the demolition of more recent ones. The participants, whose degree of consensus was very high, decided to preserve the most representative old structures and demolish the newer ones (less representative) in the interest of developing green zones and public facilities. In addition, they proposed including commemorative elements, such as visual indications of where rooms or corridors used to be, to symbolically recall the missing facilities (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018a, 15–18).

However, to a certain extent, some of these responses were conditioned by the discourses of the working document, particularly in terms of which spaces could or should be preserved and remembered, and which should not (JPAM arquitectura & Urbanisme Citation2017; Veclus S.L. Citation2017). Reviewing the documents used in the workshop from a critical point of view, we perceive that there is a dominant single expert discourse that suggests the demolition of certain buildings, which in the report are indicated as having ‘lesser historical value’ (Veclus S.L. Citation2017, 69–82). The criteria followed here are mainly chronological and architectural historical, giving less or no importance to other multivocal social values related to the intangible memories or emotions of the site (Pastor Pérez and Díaz-Andreu Citation2022). As an example, the area where prisoners received visitors will be demolished, regardless of its materiality and value that it may have had for a prisoner wanting to communicate with the outside world, and despite the arguments from participating citizens to preserve the ‘access corridor’ which generates strong symbolic appeal (). It must be noted that the citizen debate section of this workshop was quite limited in duration, lasting 75 minutes, and that not all participant groups had time to intervene in reviewing and voting on all areas of the architectural complex, as stated in the workshop reports (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018a).

Another relevant aspect to consider is that the location and discourse of the heritage memorial space, the ‘La Model Memorial Space’, were not discussed, even though it was indicated that the aim of this workshop (on heritage and memory) was to gather a collective imaginary for its discourse co-creation. The uses and location of this place, previously named the ‘Space of Memory of La Model’ in the 2017 ‘Government action’ (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2017c), were briefly debated during the workshop on the use of cultural facilities (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018a), but what will be displayed on the site on a discursive level does not appear to have been decided, or even discussed, in any participatory session. Currently, this site is managed, as a place of historical importance for the understanding of repression and social movements, by the Democratic Memory department of the City Council, which is providing free guided tours of the facilities.

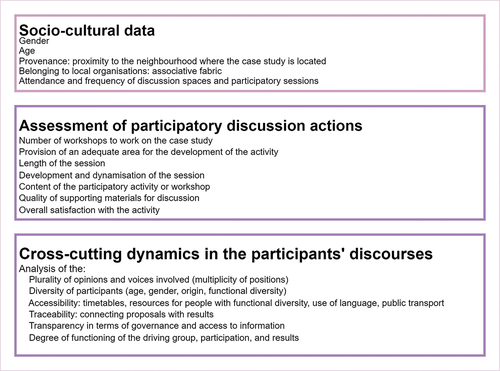

3.3. Evaluation and projection of the participatory process

To argue to what extent this participation in terms of memory and heritage has been ‘plural’, or, on the contrary, symbolic or authorised, we propose an analysis of the mechanisms applied to the process to assess how citizen participation was structured in the discussion workshops and also in the information gathered from the evaluation surveys during the results and feedback phases. Lacol and Equal Saree, the facilitators, evaluated the process through a series of indicators and a variety of standardised criteria proposed by the municipal programme ‘Active democracy’Footnote7 (Citation2018a). These include categories of diversity and plurality, accessibility, and traceability, which is the project’s ability to connect proposals with results (Spora Consulta Social Citation2019). These assessment criteria reflect a high degree of plurality and transparency, and the data shows that the participants agreed that they had been given the opportunity to express their views, with a wide range of opinions and options being represented. Furthermore, the participants themselves perceived the process as an opportunity to negotiate and share proposals, highlighting its transparency, in particular due to the periodic schedules for publishing the outcomes carried out by the facilitators (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018c).

The indicators used for the evaluation tasks, which we have grouped together in this graph (see ) are, from our perspective, fundamental for: 1) reviewing the participation structure in this process; 2) rectifying actions that are not working properly, and 3) promoting a horizontalisation of participatory dynamics, both at a general level and in the field of cultural heritage. Most of the surveys were carried out to determine the degree of satisfaction and development of the debate workshops and results sharing sessions, but also to find out the profiles of the participants, including socio-demographic factors, geographical origin, and belonging to social organisations in the territory.

Graphic 2. Phases of the participatory process carried out in the La Model. Author’s own elaboration based on Lacol and Equal Saree (Citation2018b, 2). Ana Pastor.

Graphic 3. Main indicators used in the evaluation of the participatory La Model process. Final evaluation indicators are marked in bold. Authors, based on Lacol and Equal Saree (Citation2018a; Citation2018b).

The fostering of non-authorised and plural participation is fundamental to carrying out assessment and diagnostic actions, especially in the field of cultural heritage where the narratives should achieve maximum multivocality. This should theoretically be more feasible when the debate’s participating audience is socially diverse and allows a plurality of opinions (Ross Citation2018). Thus, the analysis of the data extracted from the evaluation of the workshop debates indicates that, out of a total of approximately 200 participants, only seven participated in all the workshops, and that less than 50% of them lived in the neighbourhood where La Model is located. As mentioned above, the cultural heritage workshop had the lowest participation (61 individuals) and was mainly attended by men between 66 and 79 years of age, who came from both the immediate and surrounding neighbourhoods; furthermore, most of them were members of local social and cultural entities, delimiting the diversity of voices in the workshop (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018b, 22). Responses show that attendees rated the suitability of the space as poor (it took place in a prison corridor, see ) and the informative content of the session, which refers to the working documents drawn up by the experts, as good (JPAM Arquitectura & Urbanisme Citation2017; Veclus S.L. Citation2017). Data from the other sessions on the development of green zones and public facilities showed slightly higher participation and satisfaction rates, but no major differences.

Overall, the participants gave a positive score to the organising group’s management of participation (7.9 out of 10), although in the general evaluations they felt that the quality of the debates (5.8 out of 10) and how the results reflect their opinions (6,4 out of 10) were somewhat lower. However, the documents reflect that participants felt that their voices counted; in other words, they experienced a sense of proactive collaboration or co-creation in the decision-making for this heritage site; they felt their voices were heard and their participation was real. This message is found in the new Master Plan of the ‘Direcció de Model Urbà’ (Citation2019) which explains in its introduction that the strategy is born from the voices of residents through a participatory process and, as the document states, it ‘makes the debate legitimate’ (Direcció de Model Urbà Citation2019, 4–5). This document, in turn, was the basis for the public bidding process where the architectural project Model, Beats!Footnote8 (Flores Lucero Citation2020), was successful and is currently being developed (Espai Lur SCCLP Forgas Arquitectes SLP UTE Citation2022). In our opinion, and in line with what has been explained above, the reality of heritage participation in this case illustrates a great asymmetry of power in terms of what one party considers it is doing and what is actually taking place, which is the endorsement of the authorities’ decisions.

4. Discussion: the symbolic voices of heritage participation

This work has led us to understand the participatory process of La Model, which started years ago and was linked to neighbourhood demands and a series of institutional meetings between the government and local entities. The ‘Platform for La Model’ was created in 2016, and gave root to the subsequent ‘Driving and Follow-up group’, an amalgam of entities that has accompanied the whole process, acting as the main voice of the social fabric, and a pillar of the participatory process, in the documentation and diagnosis phase prior to the workshops. In this section, we will talk about the documents used, the lack of references to memory in them, and how participant diversity does not bring multivocality to cultural heritage if only monolithic discourses are endorsed.

In this sense, it could be argued that the individual voices of local communities (ones not linked to the influential groups of the process) arrived during the discussion-debate phase, and worked with documents that had already been made by experts (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2009b; Citation2017b; JPAM Arquitectura & Urbanisme Citation2017; Veclus S.L. Citation2017). Therefore, the heritage discussion of La Model, which aimed to ‘disseminate the will to preserve the different buildings and elements’ and ‘bring out reasoned sensitivities regarding heritage’ (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018b, 5), was not a space for listening and negotiation. It followed a series of cultural heritage criteria pre-established by the experts, explaining which buildings should be preserved and for what reasons, and diluting the voices of local communities, which could have added a plural and diverse layer to the process. These voices were used to ratify institutionalised dialogues that result in symbolic or authorised participation, making us question the veracity of this participation, which is diverse in terms of the profiles of participants but not in terms of what can be decided regarding preservation. These premises reveal a symbolic or tokenistic undertone insofar as they are expressed by expert voices that ‘aim to raise awareness’ among less-educated or non-expert citizens (Direcció de Model Urbà Citation2019, 40).

In addition, the debate about the memorial space lacked the presence of documents that embedded the materiality of the site, and at no point was there any debate about what discourses or narratives of memory to highlight; this in turn was left in the hands of experts linked to the public authorities. In the workshops, there was no mention of the heritage complexity of this contested space in which numerous stories of life, repression, and trauma have coexisted in different chronologies. These histories were not explained, along with the criteria defining the unique spaces that the participants should have debated protecting. Therefore, what was proposed in the 2009 ‘Government action’ (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2009a) and the results of the participatory process in terms of heritage and memory are very similar (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018b, 7). The question that should be asked is why society is not allowed to make decisions about cultural heritage, and why it is allowed to make decisions about green spaces (Lacol and Equal Saree Citation2018c, 19–20).

From our point of view, what emerges is a heritage-authorised participatory process in which decisions can only be made based on a series of criteria, pre-established by the experts and the administration, and endorsed by the ‘Driving and Follow-up group’, which is partially made up of their own entities. Conversely, the participatory process evaluation sends a cosmetic message: that society ‘seems to participate’ in the heritage policy decision-making process, but, in the end, what is found in the official documents (see ) is a semi-participatory and authoritative patrimonial discourse that endorses ideas shaped by a commission of experts (see Direcció de Model Urbà Citation2019, 87–89).

The intention of the facilitators (Lacol and Equal Saree) was to achieve real and diverse participation, and, to this end, promotion was carried out at street level and on social networks for events organised by both the social and governmental fabric: events for academic debate, memorial seminars, and guided tours of the site. They also provided a range of timetables, childcare, and the promotion of workshops in virtual and non-virtual spaces. The City Council itself felt proud of a process that encouraged broad and strategic participation. However, despite establishing systems that fostered participant diversity, these participants were invited to give their opinion on a series of documents presenting monolithic arguments that reduce the idea of heritage to that of the conservation of architectural structures. Thus, a symbolic participation was encouraged whose ultimate aim was to endorse the discourse of a few expert voices and that also reduced the idea of heritage to an instrument instead of a multivocal process itself. This is particularly negative when we work towards the repurposing of contentious spaces such as prisons.

5. Concluding remarks

The Barcelona City Council has regulated participatory processes to be inclusive, plural, and innovative, guaranteeing or promoting good practices and a sense of proactivity with and for the public. However, the strategy fails when the tools used to discuss cultural heritage processes are contingent on authoritative expert discourses based, for example, on limited criteria such as monolithic discourses about the aesthetics applied to architecture. Throughout this article, we have explored how citizen participation agency is applied to decide on the resignification and reuse of a particular cultural heritage asset: a prison. La Model’s, as a heritage site, has not been considered as an assemblage that endorses tangible and intangible memories, and the experts limited its materiality to its architectural features, restricting the scope of the participatory process. Thus, the case can be argued as a clear example of a semi-authorised participatory process that harbours a series of palpable contradictions. On the one hand, it conveys a ‘sense of proactive co-creation’, due in part to the transparency and plurality of voices emanating from the process at a superficial level and promoted by an abundance of open and accessible documentation, and a communicative and self-evaluative strategy that could be described as innovative. On the other hand, and as we have seen, this is a case where the heritage debate is opaque and therefore its societal participatory agency is considered cosmetic or symbolic, leading to expert endorsement, that is to say, tokenistic participation.

Since what this example shows may be happening in other similar case studies, we encourage scholars to revise whether they are applying an authoritarian discourse when dealing with a community participatory process in cultural heritage management (Colomer Citation2021). From our perspective, participation must be understood as an intergenerational hub for the co-creation of multitemporal histories that can improve the multivocality of heritage discourses and, consequently, their social value and sense of belonging that they offer to a wide portion of the local communities. This requires practitioners to propose participatory processes that involve different layers of society developing a realistic proactive role in the configuration of memories and heritage discourses. A process involving cultural heritage can be involuntarily biased if participation does not generate spaces for negotiation, discussion, and active listening between stakeholders. If the plurality of voices and the potential niches of multivocal site resignification are silenced, it will be considered a symbolic or authorised participation in cultural heritage. To counterbalance those practices, undertaking a participatory mapping of the uses and discourses of the site as an initial phase is proposed. This will help to discover written and oral memories of the spaces, and to explore the materiality of the heritage assemblages. Authorities must invest in generating experiences that foster opportunities for negotiation on an equitable level, and where, from the initial phases, discussions and evaluation tasks are facilitated so that the shared meanings and discourses that emerge from the plural voices are more realistic.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted while Dr Ana Pastor Pérez was enjoying a one-year post-doctoral stage at the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU), as part of the Margarita Salas Program of the University of Barcelona. We would like to thank the people who carried out this participatory process for all their efforts and dedication, as well as for providing us with one of the images in this article. Finally, we would also like to express our gratitude to the anonymous reviewers and the editorial team for their invaluable contributions in enhancing the quality of this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ana Pastor Pérez

Ana Pastor Pérez is a researcher and lecturer in cultural heritage management, conservation, community archaeology and critical heritage studies. Her work focuses on the development of innovative socially committed research and knowledge-transfer strategies to connect cultural heritage with contemporary social challenges. Part of her work involves an in-depth study of ethnographic methodologies to analyse participatory processes and multivocality in cultural heritage. Ana’s research interests stem from the need to innovate in the field of social heritage studies from an intersectional perspective and the ethics of care. She has a postdoctoral position within the Margarita Salas Programme of the State Research Agency (AEI) of Spain at the University of Barcelona.

Laia Colomer

Laia Colomer is Senior Researcher at the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU). Her work focuses on the way heritage is involved in the process of remembering, meaning-making and construction of identity today, involving key concepts such as mobilities, care ethics, participation, and gender.

Notes

1. We have decided to use the term ‘La Model’, in Catalan, which is how it is known by the inhabitants of Barcelona.

2. See the transformation of an old prison in Murcia (Spain) to a centre for cultural events https://murciacultura.es/es/carcel-vieja (accessed 1 July 2023).

3. ‘Direcció de Democràcia Activa i Descentralització’ in Catalan. Translation by authors.

4. ‘Mesura de Govern’ in Catalan. Translation by authors.

5. For further reading on the topic of the evolution of participatory democracy governance in Barcelona, see Colomer, and Pastor Pérez “‘City governance, participatory democracy, and cultural heritage in Barcelona, 1986–2022’. Manuscript submitted in 2023.

6. ‘Grup Impulsor I de seguiment’ in Catalan. Translation by authors.

7. ‘Democràcia Activa’ in Catalan. Translation by authors.

8. ‘La Model, batega!’ in Catalan. Translated by authors.

References

- Actíva Prospect. 2018. Balanç de les necessitats actuals i propostes d’equipaments en relació a la Model i al seu entorn proper. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona. Area d'ecologia urbana. https://ajbcn-decidim-barcelona.s3.amazonaws.com/decidim-barcelona/uploads/decidim/attachment/file/2677/Balan%C3%A7_Equipaments_La_Model_15_03_2018.pdf.

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. 2009a. “Mesura de Govern per a la transformación del recinte de la presó Model.” Barcelona. https://bcnroc.ajuntament.barcelona.cat/jspui/bitstream/11703/84634/1/13604.pdf.

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. 2009b. “Pla Director. Criteris i continguts per a la redacció del pla director de transformació de la presó Model de Barcelona.” Barcelona. https://ajbcn-decidim-barcelona.s3.amazonaws.com/decidim-barcelona/uploads/decidim/attachment/file/2636/Pla_director_2009__La_Model.pdf.

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. 2017a. “Criteris i propostes per a una participació diversa a l’Ajuntament de Barcelona.” Barcelona. https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/participaciociutadana/sites/default/files/documents/annexos_informe_criteris_i_propostes_per_a_una_participacio_diversa.pdf.

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. 2017b. “Direcció de Democràcia Activa i Descentralització. Línies de treball 2016-2019”. Barcelona. https://bcnroc.ajuntament.barcelona.cat/jspui/bitstream/11703/115388/1/Pladetreball _ Direcció Democràcia Activa i Descentralització _ Febrer 2017.pdf.

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. 2017c. “Mesura de Govern. La ciutat obre la Model, la Model fa ciutat.” Barcelona. https://ajbcn-decidim-barcelona.s3.amazonaws.com/decidim-barcelona/uploads/decidim/attachment/file/2634/Mesura_de_Govern__La_Model.pdf.

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. 2017d. Reglament de participació ciutadana. Bracelona. https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/participaciociutadana/sites/default/files/documents/reglament_participacio_catala.pdf.

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. 2022. Reglament de participació ciutadana. Barcelona. https://media-edg.barcelona.cat/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/29075940/REGLAMENT_2022-web.pdf.

- Andreu Acebal, M. 2015. “Barcelona, els moviments socials i la transició a la democràcia: hegemonia gramsciana, referent espanyol i ruptura catalana.” Segle XX Revista catalana d’història 8:105–134.

- Arnstein, S. 1969. “A Ladder or Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Blanco, I., and R. Gomà. 2002. “Gobiernos locales y redes participativas.” In Ariel Social, edited by I. Blanco and R. Gomà. Barcelona: Ariel.

- Blanco, I., Y. Salazar, and I. Bianchi. 2020. “Urban Governance and Political Change Under a Radical Left Government: The Case of Barcelona.” Journal of Urban Affairs 42 (1): 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1559648.

- Bonet i Martí, J. 2012. “Territory as Space for the Democratic Radicalization. A Critical Approach to the Processes of Citizen Participation in Urban Policies in Madrid and Barcelona.” Athenea Digital: Revista de Pensamiento e Investigación Social 12 (1): 15. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/athenead/v12n1.914.

- Borges, V. T. 2021. “Collections confinées : le patrimoine pénitentiaire et ses objets (au Brésil et au Portugal aujourd’hui).” Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais 124 (124): 27–52. https://doi.org/10.4000/rccs.11454.

- Bueker, C. S. 2005. “Political Incorporation Among Immigrants from Ten Areas of Origin: The Persistence of Source Country Effects.” The International Migration Review 39 (1): 103–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2005.tb00257.x.

- Casellas, A. 2016. Desarrollo Urbano, Coaliciones de Poder y Participación Ciudadana En Barcelona: Una Narrativa Desde La Geografía Crítica. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 70. https://doi.org/10.21138/bage.2162.

- Collado Calle, A. 2015. “Podemos y El Auge Municipalista. Sobre Partidos-Ciudadanía y Vieja Política.” Empiria Revista de metodología de ciencias sociales (32): 169–190. https://doi.org/10.5944/empiria.32.2015.15313.

- Colomer, L. 2021. “Exploring Participatory Heritage Governance After the EU Faro Convention.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-03-2021-0041.

- Colomer, L. 2023. “Participation and Cultural Heritage Management in Norway. Who, When, and How People Participate.” International Journal of Cultural Policy. Advance online publication http://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2023.2265940” Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2023.2265940.

- Comisión Provincial de Urbanismo de Barcelona, Pla General Metropolità d'Ordenació Urbana 1976 (Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona). https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/ecologiaurbana/ca/serveis/la-ciutat-funciona/urbanisme-i-gestio-del-territori/informacio-urbanistica/normativa-del-pla-general-metropolita

- Council of Europe. 2005. “Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. Faro”. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publications.

- Crowley, J. 2001. “The Political Participation of Ethnic Minorities.” International Political Science Review 22 (1): 99–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512101221006.

- de Miguel, J., and S. Martin. 2023. Històries de La Model. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona.

- Direcció de Model Urbà. 2019. Pla director per a la Presó Model de Barcelona. Barcelona. https://bcnroc.ajuntament.barcelona.cat/jspui/bitstream/11703/114040/5/Pla_director_model_2019.pdf.

- Eichler, J. 2021. “Intangible Cultural Heritage, Inequalities and Participation: Who Decides on Heritage?” The International Journal of Human Rights 25 (5): 793–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2020.1822821.

- Espai Lur SCCLP Forgas Arquitectes SLP UTE. 2022. Projecte d’ordenació Del Conjunt de La Model. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona.

- Flores Lucero, M. L. 2020. “Gobernanza Participativa, La Experiencia de Barcelona.” Cuadernos de Vivienda y Urbanismo 13:1. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.cvu13.gpeb.

- Folguera, P. 2007. “La Evaluación Participativa de Un Programa de Formación Para Una Participación Activa e Intercultural.” Revista de Investigación Educativa 25:491–511.

- Fontova, R. 2010. La Model de Barcelona. Històries de La Presó. Barcelona: Generalitat de Catalunya. Departament de Justícia.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogía Del Oprimido. México D.F: Siglo XXI.

- Ganuza, E., G. Baiocchi, and N. Summers. 2016. “Conflicts and Paradoxes in the Rhetoric of Participation.” Journal of Civil Society 12 (3): 328–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2016.1215981.

- González del Pozo, J. 2020. Quinqui Film in Spain: Peripheries of Society and Myths on the Margins. London: Anthem Press.https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvq4c19b

- Grosfoguel, R. 2016. “Del Extractivismo Económico Al Extractivismo Epistémico y Ontológico.” Revista Internacional de Comunicación y Desarrollo (RICD) 1 (4): 33–45. https://doi.org/10.15304/ricd.1.4.3295.

- Hammami, F. 2016. “Issues of Mutuality and Sharing in the Transnational Spaces of Heritage – Contesting Diaspora and Homeland Experiences in Palestine.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 22 (6): 446–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2016.1166447.

- Hanson, K. E., S. Baumann, T. Pasqual, O. Seowtewa, and T. J. Ferguson. 2022. “‘This Place Belongs to Us’: Historic Contexts as a Mechanism for Multivocality in the National Register.” American Antiquity 87 (3): 439–456. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2022.15.

- Hertz, E. 2015. “Bottoms, Genuine and Spurious.” Between Imagined Communities of Practice: Participation, Territory and the Making of Heritage. Göttingen: Göttingen University Press. https://books.openedition.org/gup/210.

- Jones, S. 2017. “Wrestling with the Social Value of Heritage: Problems, Dilemmas and Opportunities.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 4 (1): 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/20518196.2016.1193996.

- JPAM Arquitectura and Urbanisme. 2017. “Estudi comparatiu sobre la reutilització d’edificis panóptics.” Barcelona. https://ajbcn-decidim-barcelona.s3.amazonaws.com/decidim-barcelona/uploads/decidim/attachment/file/2637/Comparatiu_de_panoptics.pdf.

- Lacol and Equal Saree. 2018a. “La Model s’obre a la ciutat. Presentació a la Comissió de seguiment del Consell de Barri.” Barcelona.

- Lacol and Equal Saree. 2018b. “Annexos. Informe de resultats del procés participatiu de La Model.” Barcelona.

- Lacol and Equal Saree. 2018c. “Informe de resultats del procés participatiu de La Model.” Barcelona.

- Lesh, J. 2022. Values in Cities. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429352713.

- Martí, M., I. Blanco, M. Parés, and J. Subirats. 2016. “Regeneración Urbana y Gobernanza ¿Cómo Evaluar La Participación En Una Red de Gobernanza? Tres Perspectivas Teóricas y Un Estudio de Caso.” In Participación, Políticas Públicas y Territorio, edited by A. Rofman, 27–52. Buenos Aires: Ediciones UNGS.

- McAtackney, L. 2014. An Archaeology of the Troubles: The Dark Heritage of Long Kesh/Maze Prison. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199673919.001.0001.

- Parés, M. 2017. Repensar La Participación de La Ciudadanía En El Mundo Local. Barcelona. https://www1.diba.cat/uliep/pdf/58740.pdf.

- Pastor Pérez, A. 2019. “Conservación Arqueológica Social. Etnografías Patrimoniales En El Barri Gòtic de Barcelona.” PhD diss., Universitat de Barcelona. https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/668161.

- Pastor Pérez, A., D. Barreiro Martínez, E. Parga-Dans, and P. Alonso González. 2021. “Democratising Heritage Values: A Methodological Review.” Sustainability 13 (22): 12492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212492.

- Pastor Pérez, A., and M. Díaz-Andreu. 2022. “Evolución de Los Valores Del Patrimonio Cultural.” Revista de Estudios Sociales 80 (80): 3–20. https://doi.org/10.7440/res80.2022.01.

- Pastor Pérez, A., and A. Ruiz Martínez. 2021. “Metodologías Para Una Conservación Preventiva Participativa En Arqueología.” Vestígios - Revista Latino-Americana de Arqueologia Histórica 14 (2): 121–149. https://doi.org/10.31239/vtg.v14i2.26085.

- Quintelier, E. 2009. “The Political Participation of Immigrant Youth in Belgium.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (6): 919–937. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830902957700.

- Ross, S. 2018. “Strategies for Municipal Participatory Governance and Implementing UN-Habitat’s New Urban Agenda: Improving Consultation and Participation in Urban Planning Decision-Making Processes Through Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Procedure.” Canadian Bar Review 96 (2): 294–323. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3008945.

- Roura-Expósito, J. 2019. “El Discreto Encanto de La Participación En El Proceso de Patrimonialización de La Casa Del Pumarejo (Sevilla).” In El Imperativo de La Participación En La Gestión Patrimonial, edited by C. Sánchez-Carretero, J. Muñoz-Albadalejo, A. Ruiz-Blanch, and J. Roura-Expósito, 79–108. Madrid: CSIC. Ministerio de Educación Ciencia y Universidades.

- Ruano de la Fuente, J. M. 2010. “Contra La Participación: Discurso y Realidad de Las Experiencias de Participación Ciudadana.” Política y Sociedad 47 (3): 93–108. https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/POSO/article/view/POSO1010330093A.

- Ruiz-Blanch, Ana, and José Muñoz-Albadalejo. 2019. “Participación Ciudadana: Del Welfare Al Do It Yourself.” In El Imperativo de La Participación En La Gestión Patrimonial, edited by C. Sánchez-Carretero, J. Muñoz-Albadalejo, A. Ruiz-Blanch, and B. JoanRoura-Expósito, 41–57. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas.

- Sánchez-Carretero, C., and J. Roura-Expósito. 2021. “Participación: Usos, Límites y Riesgos En Los Proyectos Patrimoniales.” In Patrimonio y Museos Locales: Temas Clave Para Su Gestión/Patrimoine et Musées Locaux : Clés de Gestion, edited by I. A. Urtizberea and I. D. Balerdi, 339–357. Tenerife: PASOS.

- Schofield, J. 2009. “Being Autocentric: Towards Symmetry in Heritage Management Practices.” In Valuing Historic Environments, edited by L. Gibson and J. Pendlebury, 93–114. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Company.

- Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London; New York: Routledge.

- Spora Consulta Social. 2019. “Sistema de seguiment i avaluació del programa Democràcia Activa. Manual d’ús.” Barcelona. Manual d’ús actualitzat.pdf. https://bcnroc.ajuntament.barcelona.cat/jspui/bitstream/11703/115389/1/190517.

- Veclus S. L. 2017. “Estudi històrico-arquitectònic i valoració patrimonial de l’antiga Presó Model (Barcelona).” Barcelona. https://ajbcn-decidim-barcelona.s3.amazonaws.com/decidim-barcelona/uploads/decidim/attachment/file/2642/Estudi_històric_Model.pdf.