?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

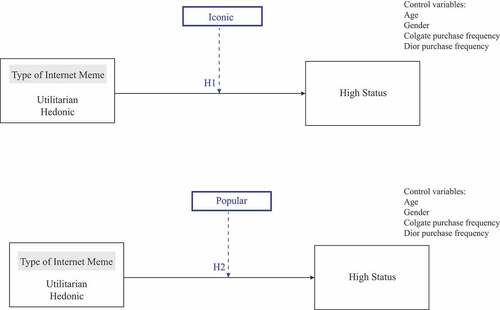

This study aims to explore the moderator role of popular and iconic coolness dimensions on the relationship between hedonic versus utilitarian beauty product brands and high-status perceptions, using internet memes as stimuli. An experimental study was conducted to analyse whether two dimensions of brand coolness (popular and iconic) moderate the relationship between type of internet meme (utilitarian versus hedonic) and high-status. After conducting a pre-test, two internet memes were created for each condition, utilitarian and hedonic. In total, 428 completely answers were collected from an online MTurk panel, and the hypotheses were tested using moderation analysis. The results indicate that (i) hedonic brands are perceived as being high-status in the presence of both moderators (iconic and popular); (ii) utilitarian brands can be associated with high-status perceptions, if moderated by the popular dimension. Findings demonstrate that the popularity of the brand plays an important role in consumers perceptions. This study contributes to the marketing literature by analysing the relationship between three core dimensions of brand coolness, namely, iconic, popular, and high-status, regarding brands associated with hedonics and utilitarian products.

Introduction

Digital platforms are one of the best tools to connect consumers worldwide (Nieubuurt Citation2021). Specifically, in the first quarter of 2021, Facebook alone had an active user base of 2.91 billion users, YouTube had 2.29 billion active users, while Instagram had 1.39 billion active users (Statista Citation2021). Content is key in the digital environment (Tong Citation2021). With such high numbers of online users, and the need to keep them interested, memes have become content often used to interact with consumers.

A meme is informative and easy to share online among consumers (Wang and Wood Citation2011). Internet memes (IMs) can be defined as ‘an image, video, piece of text, etc., typically humorous in nature, that is copied and spread rapidly by internet users, often with slight variations (Lonnberg, Xiao, and Wolfinger Citation2020, 1). Overall, IMs are a product of a culture used to communicate through visual images and texts (Brubaker et al. Citation2018). Thus, IMs are a unique way for people to share their ideas with a wider audience (Jenkins et al. Citation2009).

IMs usually take the form of animations, GIFs, videos, images, and image macros. Although all these forms are relevant, image macros are the most common (Vasquez and Aslan Citation2021). Brands can easily integrate this type of IMs into their communication strategy as image macros are flexible and able to relate to many expressions (e.g., humour, advice, irony, sarcasm).

In addition to connecting brands and consumers around the world, social media also allows users to check out the latest trends and, most importantly, what’s cool today. Coolness reflects consumers’ perceptions of a brand or product’s quality, distinction, or novelty (Sundar, Tamul, and Wu Citation2014). Consequently, being a cool brand and having cool content is becoming increasingly important to managers and practitioners. IMs can be cool, funny, and because they are easy to share IMs can have a positive impact on consumer behaviour (Nieubuurt Citation2021).

Brand coolness (hereafter BC) demonstrates to have a positive influence on the consumer decision-making process (Mohiuddin et al. Citation2016). Prior studies on brand coolness have focused on explaining the meaning of brand coolness and the motives behind being cool (Warren et al. Citation2019; Loureiro, Jimenez, and Romero Citation2020), associating the concept with other relevant constructs – such as brand love (Tiwari, Chakraborty, and Maity Citation2021), self-brand connection (Suzuki and Kanno Citation2022), or perceived luxury values (Loureiro, Jimenez, and Romero Citation2020) – and further detailing about specific coolness dimensions (e.g., rebelliousness) (Sundar, Tamul, and Wu Citation2014), or even exploring brand coolness on the service environment (Jimenez-Barreto et al. Citation2022). Yet, academics still did not attempt to analyse how individual dimensions of coolness influence consumers’ perceptions. Although, it is known that the cool characteristics of a brand affect the perceptions, attitudes, and behaviour of consumers (e.g., Warren et al. Citation2019; Swaminathan et al. Citation2020; Suzuki and Kanno Citation2022). The literature does not explain how these cool characterises affect consumers’ perceptions. Particularly, (1) there is no literature establishing a connection between IMs and brand coolness and (2) the impact of independent brand coolness dimensions (e.g., high-status, iconic and popular) on consumers’ perceptions, in the context of hedonic versus utilitarian products.

The present study aims to fulfil the abovementioned knowledge gap and contribute to the scholarly literature by exploring the influence of popular and iconic coolness dimensions on high-status perceptions, considering hedonic versus utilitarian beauty product brands using IMs as stimuli. Further, we strive to answer the following research question, hence, when comparing utilitarian and hedonic familiar brands, how does being popular or iconic contribute to strength or weakness in high-status perceptions? Answering this question contributes theoretically to better understanding the coolness phenomenon, putting the focus on three specific characteristics – popular, iconic, and high-status – and analyse how popular and iconic can or cannot strengthen the relationship between the type of internet meme and high-status.

The hedonic/utilitarian dichotomy mirrors differences in terms of functions, attributes, and perceptions. Some authors (Ki, Lee, and Kim Citation2017; Shahid et al. Citation2022; Kim, Park, and Shrum Citation2022) argue that pleasure versus utility may be applied to online designs, linked to appealing value propositions. Research has also evidenced that consumers’ engagement with brand-related content on social media is also influenced differently by utilitarian and hedonic brand values (Schivinski et al. Citation2020). Therefore, utilitarian, and hedonic values will have a direct and different preferences for different consumers (Kastanakis and Balabanis Citation2012).

High-status represents social class and sophistication, traditionally more associated with hedonic products (Belk, Tian, and Paavola Citation2010; Nancarrow, Nancarrow, and Page Citation2003; Milner Citation2013). Yet, other dimensions of brand coolness, such as iconic or symbolic (Holt Citation2004) can be expected to strengthen the perception of high-status, even in a situation of a utilitarian product. In the same way, the fact of a brand being popular or trendy (Dar-Nimrod et al. Citation2012; Potter and Heath Citation2004), can also influence the perception of high-status because being liked by most people can be regarded as a mass cool brand and associated with esteem and value (Milner Citation2013). Therefore, status seekers are role anxious consumers since they are concerned with significant others and their social standing or rank in the social system (Kastanakis and Balabanis Citation2012; Kim, Park, and Shrum Citation2022). As utilitarian behaviour is associated with goal-oriented and conscious responses, while hedonic behaviour is linked to fun, enjoyment, and unconscious responses we expect differences in high-status perceptions for both IMs in the presence of iconic and popular moderators.

The insights presented in this study have the potential to enlighten practitioners who wish to leverage the symbolic values, popularity, and high-status perceptions embedded in IMs to boost their communication on social media and enhance the coolness of their brands. When communicating through IMs, it is important to make sure that the tone of the message is in line with the brand values.

Given these assumptions, the remaining parts of the article are organized to present the literature review and the development of hypotheses. Then the methodology is described, and the results are presented and discussed. The end of the article shows the implications and future research agenda.

Theoretical background and hypothesis development

Brand coolness

The meaning of coolness is seen as subjective, of positive valence, autonomous and dynamic (Warren and Campbell Citation2014; Anik et al. Citation2017). The brand coolness concept shows a positive multi-attribute association with ten-dimension (Warren et al. Citation2019; Loureiro, Jimenez, and Romero Citation2020), namely (1) useful/extraordinary, the brand offers high quality and tangible benefits (e.g., Belk, Tian, and Paavola Citation2010; Dar-Nimrod et al. Citation2012); (2) aesthetically appealing, the brand offers attractive and designs different from its competitors (Bruun et al. Citation2016); (3) energetic, the brand is perceived as being active, outgoing and youthful (Runyan, Noh, and Mosier Citation2013); (4) original, an original brand is a creative, unique brand (Runyan, Noh, and Mosier Citation2013); (5) authentic, the brand has a set of true authentic values from production to customer care (Biraglia and Brakus Citation2020); (6) rebellious, the brand strives to set apart by being nonconformist (Potter and Heath Citation2004); (7) high-status, the brand is associated with prestige and sophistication (Nancarrow, Nancarrow, and Page Citation2003; Loureiro, Jimenez, and Romero Citation2020); (8) subcultural, cool brands are often associated with groups of people who are perceived to work independently from mainstream society (Warren et al. Citation2019; Sundar, Tamul, and Wu Citation2014); (9) iconic, the brand reflects the individuals’ values and beliefs, being recognized as a cultural symbol (Holt Citation2004); and (10) popular, a cool brand is perceived to be fashionable, trendy, and liked by most people (Dar-Nimrod et al. Citation2012; Warren et al. Citation2019). Although cool brands present these characteristics, the perceptions and the importance of each dimension vary from brand to brand. Most recently, studies have demonstrated that brands do not need to be perceived as having the ten coolness characteristics to be regarded as cool (Warren et al. Citation2019; Loureiro, Jimenez, and Romero Citation2020).

In the literature, BC was also linked to uniqueness i.e., consumers tend to seek products/brands that are different, novel, and unique (Septianto et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, BC is reflected on the consumers as a way to identify themselves and socially with the brand (Septianto et al. Citation2020), which consequently impacts their consumption behaviour in terms that illustrates the tendency to consume products for status display (Pino et al. Citation2019). As BC influences the extent to which consumers hold a more favourable attitude towards the brand, their willingness to pay is likely to increase (Pham, Valette-Florence, and Vigneron Citation2018). Coolness is both subjective and dynamic in the sense that objects or people that consumers consider to be cool, change over time and across consumers (O’Donnell and Wardlow Citation2000).

Brands, regarded as cool by consumers can be categorized as niche cool and mass cool (Pham, Valette-Florence, and Vigneron Citation2018). Niche cool brands are perceived to be cool by a particular subculture, but not adopted by the masses, while mass cool are brands perceived to be cool by the general population (Warren Citation2010; Mohiuddin et al. Citation2016). It is beyond the scope of this study to investigate both categorizations of brands. Although both are relevant to the literature, the current study adopts this reductive perspective and focuses on three specific dimensions of BC, i.e., popular, iconic, and high-status. Following Warren et al. (Citation2019), it is possible to link specific coolness dimensions with being mass or niche cool. The three dimensions – popular, iconic, and high-status – are commonly associated with mass cool brands. Even though hedonic products can be perceived as niche cool, there is not an established association in the literature connecting both concepts (Loureiro, Jimenez, and Romero Citation2020; Hirschman and Holbrook Citation1982; Alba and Williams Citation2013; Deb and Lomo-David Citation2020). For instance, the Louis Vuitton brand is a luxury brand, perceived as being mass cool as it is known by the general population. We can further associate the popular, iconic, and high-status dimensions with the brand Louis Vuitton, as the brand is familiar to the masses (popular), it sells premium-priced high-standard products (high-status), and classic products (iconic).

Coolness and hedonic versus utilitarian products

Hedonic consumption is defined as ‘the facets of buying behaviour that relate to multisensory, fantasy and emotive aspects of one’s experience with products’ (Hirschman and Holbrook Citation1982, 92) and is a way for consumers to seek pleasure and pleasure. Thus, pleasure is an important component of hedonic consumption as it acts as a guidepost. A vital component of hedonic consumption is whether the experience of consuming the product or event is pleasurable or not (Alba and Williams Citation2013). Hedonic reactions to aesthetic features can overwhelm utilitarian, independent of the type of memes. For instance, consumers develop a preference for a more aesthetically pleasing product when they have the choice.

Hedonic products are perceived to offer pleasure and excitement, representing indulgence or nonessential products (Alba and Williams Citation2013; Dhar and Wertenbroch Citation2000; Lu, Liu, and Fang Citation2016; Nikhashemi and Delgado-Ballester Citation2022). Therefore, hedonic consumption is positively associated with BC perceptions (Warren et al. Citation2019; Warren Citation2010). Conversely, utilitarian goods are functional, effective, and practical (Alba and Williams Citation2013; Dhar and Wertenbroch Citation2000; Lu, Liu, and Fang Citation2016). Although utilitarian products are often connected to needs, the literature proposes that utilitarianism and brand coolness perceptions are linked (Runyan, Noh, and Mosier Citation2013). Runyan, Noh, and Mosier (Citation2013) propose a model of coolness which can be conceptualized through a two-dimensional factor composed of utilitarian cool and hedonic cool.

Products can have both hedonic and utilitarian characteristics. A product can present functionality and provide the consumer with a feeling of joy (Chernev Citation2004). An example of this duality is given by Lu, Liu, and Fang (Citation2016), who mentions athletic shoes’ attributes. That kind of shoe presents its utilitarian value by providing protection and enhancing the individual’s performance while delivering an enjoyable and exciting experience – the hedonic value.

High-status, iconic, and popular as dimensions of brand coolness

Status can be defined as the position in a society or within a group that others ascribe to an individual (Goffman Citation1959). Researchers conceptualize status consumption as a characteristic of people who wish to improve their social standing through items that symbolize status, both for the individual and the significant others (Eastman, Goldsmith, and Flynn Citation1999). Status is linked to the symbolic uses of luxury products (Belk Citation1988; Braun and Wicklund Citation1989; Goffman Citation1959), as consumers acquire, own, use, and display them to enhance their sense of self, and to produce types of social relationships they wish to have. Packard (Citation1959, 5) defines status seekers as ‘people who are continually straining to surround themselves with visible evidence of the superior rank they are claiming’.

High-status represents prestige, upper social class, and sophistication (Belk, Tian, and Paavola Citation2010). A high-status brand usually has a higher price, high standards of excellence, superior quality, and luxurious features (Jiménez-Barreto et al. Citation2022; Bellezza and Berger Citation2020). Consumers who use high-status brands are perceived as wealthy, successful and elite people (O’Cass and McEwen Citation2004). However, considering the status consumption theory, individuals who seek to buy for status display are independent of both income and social class (Mason Citation1992; Latter et al. Citation2010). Status-seekers usually perceive luxury (vs. non-luxury) consumers to hold high (vs. low) levels of status (Nelissen and Meijers Citation2011). Although prior literature points to this association, it is still unclear how different types of luxury signals can be associated with different statuses of individuals. Thus, luxury products that signal high levels of status may not always symbolize individuals’ high achieved status (Pino et al. Citation2019).

According to the symbolic consumption literature (Griskevicius, Tybur, and Van den Bergh Citation2010), the iconic luxury concept is a representation of the owners’ status. An iconic product remains on sale from season to season, which entails the luxury brands’ heritage, and it is consistent with what customers expect from the brands’ classic style and aesthetics. For instance, the Hermès Birkin bag, or the Louis Vuitton canvas are iconic products (Napoli et al. Citation2014; Grayson and Martinec Citation2004). Being iconic is also associated with symbolism, as iconic products can be a source of status display, with the growing demand for exclusivity. Consumers are looking for specific products which can give them the power to feel unique (Siepmann, Holthoff, and Kowalczuk Citation2022). Iconic products are popular for being classical, stable, and having predictable qualities or providing predictable experiences (Grayson and Martinec Citation2004).

Prior literature asserts the link between high-status and iconic constructs, as iconic pieces are frequently associated with high-status brands (Pino et al. Citation2019). However, the literature also claims that even though iconic products/brands can be perceived as having superior quality and price, an iconic piece is above all, a classic one (Griskevicius, Tybur, and Van den Bergh Citation2010). For example, the Volkswagen Beetle is a classic iconic model, thus, it is not defined as a luxury brand. Therefore, iconic pieces can be hedonic or utilitarian in nature (Alba and Williams Citation2013; Dhar and Wertenbroch Citation2000; Napoli et al. Citation2014; Grayson and Martinec Citation2004). Following the same line of reasoning, utilitarian and hedonic attributes will not reveal the same dissonance during consumer decision-making (Sung and Phau Citation2019; Kim, Park, and Shrum Citation2022). Thus, the differences between these attributes can be crucial for consumer choice, and perceptions. While utilitarian attributes require higher mental processing, hedonic attributes are motivated by sensory enjoyment (Kang and Park‐poaps Citation2010; Schivinski et al. Citation2020).

Hence, considering status consumption theory and taking the above considerations, we argue that the iconic dimension of brand coolness will have an impact on the type of internet meme and high-status perceptions relationship. We expect that utilitarian pieces/products will be perceived as high-status when associated with low-iconic levels, and hedonic products will be perceived as high-status when associated with high-iconic levels. Based on this argumentation we anticipate:

H1:

Iconic BC dimension moderates the positive relationship between IM type and high-status perceptions, so that (H1a) the utilitarian IM will be perceived as high-status with low-iconic perceptions and (H1b) the hedonic IM will be perceived as high-status with high-iconic perceptions.

Status and popularity mean that consumers buy specific popular pieces that can act as status symbols (Kastanakis and Balabanis Citation2014). The popular concept defines brands as being fashionable, trendy, and liked by most people (Dar-Nimrod et al. Citation2012; Kumagai and Nagasawa Citation2021). Popularity comes in two ways; it can be a positive connotation or being too popular may lead brands to be considered too mainstream, losing the ‘cool factor’ (Kastanakis and Balabanis Citation2012). When brands become too cool for a wider population (the masses), so does the level of familiarity (Sharma et al. Citation2021). Consumers engaged in this type of consumption are not only followers of trends in luxury markets, but also seek recognition within a social context. They seek status gains through association with or actual membership in the right status groups, using appropriate branding (Lascu and Zinkhan Citation1999; Skitovsky Citation1992). With luxury goods becoming more mainstream for individuals who seek to display status to others, iconic products rise in importance (Siepmann, Holthoff, and Kowalczuk Citation2022). In this vein, the more people use a brand and/or a product to claim status, the less status it will confer, as it will lose uniqueness and decrease desirability (Dion and Borraz Citation2017). In contrast, popular pieces allow consumers to feel part of a group (Lascu and Zinkhan Citation1999). A popular product may be utilitarian or hedonic (Kastanakis and Balabanis Citation2014).

Hedonic motivations, being more associated with emotions, tend to create a positive predisposition for marketing messages, which further stimulate not only consumers’ perceptions but also purchase intention (Kastanakis and Balabanis Citation2012; Shahid et al. Citation2022). Thus, emotional responses using a hedonic and popular brand IM as a marketing cue can lead to a greater perception of a brand’s status. In contrast, utilitarian consumers, being more rational, and concerned with efficacy and instrumental value, are expected to develop an association with low popularity.

Hence, regarding the above considerations, we propose that the popular dimension will act as a moderator between the type of internet meme and high-status perceptions. Utilitarian pieces will be perceived as high-status when associated with low-popularity, and hedonic ones will be perceived as high-status when associated with high-popularity (See ). Considering this argumentation, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H2.

Popular BC dimension moderates the positive relationship between IM type and high-status perceptions, so that (H2a) the utilitarian IM will be perceived as high-status with low-popularity perceptions and (H2b) the hedonic IM will be perceived as high-status with high-popularity perceptions.

Methodology

Design and procedure

Pre-test. The purpose of the pre-test was to select which hedonic and utilitarian brands to investigate throughout the main study. Data was collected using the Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) (Buhrmester, Talaifar, and Gosling Citation2018). Participants were compensated USD 1.00 for their time in fulfilling the survey. Following guidelines from the literature, a total of 186 participants were asked to identify the more utilitarian and the more hedonic products out of eight preselected brands (Li et al. Citation2020), in the context of personal beauty products. The brands were assigned from the Brand Directory Ranking (Citation2021) and Interbrand: Ranking the Brands (Citation2021), so that we could analyze the highest ranked brands for both, utilitarian and hedonic conditions. Four brands were tested for each condition (utilitarian and hedonic). The brands Colgate Total toothpaste, Pantene Shampoo, Nivea deodorant and Dove body wash represented the utilitarian brands. Hedonic brands included O.P.I nail polish, Chanel Perfume, Dior eye shadow, and Colour WoW hairspray. Through the analysis of the results and considering the highest frequency for each category (hedonic and utilitarian) the selected brands were Colgate, as 98,4% (n = 183) of participants associated the brand with being utilitarian; and Dior with 89.9% (n = 167) of participants associating the brand with being hedonic.

In terms of the structure of the sample, there was a balanced distribution of gender (56.4% were female, n = 105). Regarding age, the sample was well balanced across age gaps i.e., 29.6% (n = 55) were between 18–20 years old; 17.2% (n = 32) between 21–30 years old; 22.0% (n = 41) between 31–40 years old; 31.2% (n = 58) were 41 and above.

Stimuli. After selecting the brands to test for both conditions, we pursued with the stimuli development of an Internet Meme for the hedonic and utilitarian categories. The IM used was created using the Imgflip website, an online meme generator tool that has a database of the most popular IM images. An image belonging to the ‘Lolcat’ meme family (one of the most used IMs), was selected. The same IM image was used for both conditions, to avoid bias. However, to differentiate between the hedonic and utilitarian IMs, brand logos and two different captions were created for each IM. The choice of captions was based on the brand and product associations (i.e., Dior – makeup and Colgate – toothpaste) and semantically prepared to emphasize hedonism and utilitarianism characteristics of both selected products and brands. The captions were pre-tests following the same procedures as described above.

Main Study. To compute the minimum sample size required for the analysis a priori, power analysis was conducted using (version 3.1.9.6) (Faul et al. Citation2009). The analysis was based on a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), α = 0.05, and pre-set power (1 – β = 0.95), with three predictors (i.e., type of internet meme, iconic and popular) and four sociodemographic and usage variables (age, gender, Colgate purchase frequency and Dior purchase frequency). The calculations yielded a minimum sample size of 74 participants for an expected power of 0.95. The main survey was conducted using MTurk online crowdsourcing platform (Buhrmester, Talaifar, and Gosling Citation2018), similarly to the pre-test, participants were compensated USD 1.00 for their time. The survey was administered in English, and all instructions were provided in the beginning. A total of 428 respondents participated in the study (n(Utilitarian) = 214, 50%; n(Hedonic) = 214, 50%).

At first, participants were presented with a small introduction to the survey question regarding their knowledge of what a meme is. Subsequently they were randomly assigned to one of the two available conditions (utilitarian IM or hedonic IM), and were presented with a set of questions, considering the brand coolness scale. In the end, they were presented with a set of demographic questions.

Measures

To measure BC dimensions, namely iconic, high-status, and popular we followed Warren et al. (Citation2019), adapting a 5-point Likert-type scale (from 1 ‘Strongly Disagree’ to 5 ‘Strongly Agree’. To measure the iconic dimension, respondents were asked their level of agreement with the following items: ‘this brand is a cultural symbol’ and ‘this brand is iconic’ (Spearman’s ρ = 0.75). To measure the popular dimension, respondents were asked their level of agreement with the following items: ‘this brand is liked by most people’, ‘this brand is in style’, ‘this brand is popular’ and ‘this brand is widely accepted’ (α = 0.92). As for the high-status dimension, respondents were asked their level of agreement with the following items: ‘this brand is chic’, ‘this brand is glamorous’, ‘this brand is sophisticated’ and ‘this brand is ritzy’ (α = 0.87).

The sociodemographic variables concerned participants’ gender (male, female), age and education level. Furthermore, purchase frequency was measured adapting a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 ‘Never’ to 5 ‘Very Often’). Participants were asked how often they buy the brand. The survey controlled for the following variables: age, gender, Colgate purchase frequency and Dior purchase frequency.

Data management and data analysis

All analysis were conducted using IBM SPSS 28.0. The data management was conducted as follows: (1) missing and unusual values and (2) univariate normality. First, missing values were eliminated (n = 25; 5.5%) (Goodman, Cryder, and Cheema Citation2013). As for the univariate normality, the skewness and kurtosis were calculated for each of the measured items. Following our results, no absolute values above 8 (for kurtosis) and above 3 (for skewness) (Kline Citation2011) supporting no evidence of univariate non-normality. Thus, we proceeded with our analysis, with a final sample of 428 participants. Respondents were evenly presented in the two conditions: nUtilitarian = 214 (50%) and nHedonic = 214 (50%).

The statistical analyses were conducted following the steps: (1) sample description, (2) Pearson-correlation across the BC dimensions, (3) moderation analysis using PROCESS macro for IBM SPSS 28.0 (model 1; Hayes Citation2018). In the context of social sciences, PROCESS is still the most recommended and used macro for moderation and mediation analysis when using univariate data (Field Citation2017; Hayes Citation2018).

Results

Descriptive statistics

In total, 428 datapoints were analyzed. The sample was balanced (50.9% female, n = 218). Concerning the sample age groups, 29.9% (n = 128) were between 18–20 years old, 15.4% (n = 66) between 21–30 years old and 24.8% (n = 106) between 31–40 years old, and 29.9% (n = 128) above 41 years old (see ).

Table 1. Univariate normality results.

To test for the conceptual model and hypotheses, two linear regression models were estimated to test the effects of the effects of utilitarian and hedonic IMs on high-status perceptions whereas moderated by iconic (H1) and popular (H2) BC dimensions. The models were controlled for age, gender, Colgate purchase frequency and Dior purchase frequency respectively.

High-status

Pearson correlation (r) was used to assess the correlates of high-status with all the investigated variables. For the statistical calculations, we computed the aggregated mean scores for each variable. High-status was positively associated with popular BC (r = 0.55; p < 0.001), and iconic BC (r = 0.56; p < 0.001). High-status negatively correlated with gender (rFEMALE:1 = −0.13; p < 0.05), age (r = −0.21; p < 0.01) and with purchase frequencies for the utilitarian IM (rCOLGATE = −0.15; p < 0.05). There were no statistically significant effects for the hedonic IM (p > 0.05). The direction and significance of the correlations corroborate with the literature and previous empirical findings (Deb and Lomo-David Citation2020). reports the correlation matrix and descriptive statistics for the variables.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlations across variables.

Hypothesis testing

Assuming a continuous dependent variable, a continuous moderator (popular and iconic brand coolness dimensions) and a dichotomous independent variable (IM type), the moderation analysis is tested by estimating a linear regression model (Hayes Citation2013, Citation2015)(see ). Popular and iconic dimensions linearly moderate the effect of product type on the dependent variables if the regression coefficient for the interaction is different from zero between lower and upper levels confidence intervals (Hayes Citation2013, Citation2015) (see for detailed results).

Figure 2. Moderation results, with iconic and popular as moderators (PROCESS: Model 1; Hayes, Citation2018).

Figure 3. Moderation results, popular as a moderator (PROCESS: Model 1; Hayes, Citation2018).

Table 3. Moderation results, with iconic and popular as moderators (PROCESS: Model 1; Hayes, Citation2018).

The results after controlling for age, gender, Colgate purchase frequency and Dior purchase frequency reveal a significant interaction was obtained for both type of internet meme x iconic (β = 0.43, SE = 0.11, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [0.22; 0.64]) and type of internet meme x popular (β = 0.59, SE = 0.11, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [0.38; 0.80]). A significant effect was obtained for both moderators when analysing the hedonic brands, (Iconic: β = 1.23, SE = 0.20, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.83; 1.63]; Popular: β = 1.63, SE = 0.19, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [1.25; 2.01]). As for the utilitarian brands, there is no significant effect for the iconic moderator in high-status perceptions. However, there is a significant effect for the popular moderator in high-status perceptions, so that utilitarian brands are associated with low levels of popularity (Popular: β = 0.46, SE = 0.19, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.09; 0.84]). Thus, partially validating H1 and fully validating H2.

Conclusions

Discussion

Consumption behaviour is constantly changing; thus, it is important to continuously analyse what drives consumers to choose one brand versus the other (Dubois et al. Citation2021). With the evolution of marketing communication, brands are adapting the way they communicate, and they can now advertise their products through IMs, online videos and use other online platforms. The current study explores the relationship between brand coolness dimensions and the type of internet meme, through the usage of IMs.

Our findings are aligned with prior literature, which claims that coolness perceptions differ from brand to brand, and across consumers (Jimenez-Barreto et al. Citation2022; Loureiro, Jimenez, and Romero Citation2020). Thus, different coolness dimensions will have different influences on different brand and product categories (Eckhardt et al. Citation2015; Makkar and Yap Citation2018; Berger and Ward Citation2010). The present study contributes to the literature by demonstrating that the iconic moderator strengthens the relationship between IM type and high-status, so that, for high levels of iconic, hedonic brands will be associated with high-status perceptions. This relationship was not supported for the utilitarian IM. A possible explanation is that utilitarian products are frequently associated with functional and simple characteristics, while hedonic items are associated with pleasure and extravagance (Deb and Lomo-David Citation2020). A similar effect was found in a study within the context of collaborative consumption on social media (Schivinski et al. Citation2020), which revealed that for both utilitarian and hedonic brands to influence consumers’ behaviours, the relationship should be mediated by positive brand associations (i.e., brand equity).

An iconic item can be a way to symbolize status, thus, following prior literature utilitarian brands are not purchased for this reason, rather, items of this category are purchased for necessity (Alba and Williams Citation2013).

On another hand, the popular BC dimension moderates both, utilitarian and hedonic brands, so that for low levels of popularity the utilitarian brand is associated with high-status perceptions, and for high levels of popularity the hedonic brand is connected to high-status perceptions. Therefore, the findings demonstrate that: (1) not only luxury brands are perceived as high-status, but also utilitarian products can be perceived as high-status; (2) when referring to different brand categories, the popular dimension plays a very important role, as both hedonic and utilitarian products of well-known brands are associated with high-status perceptions.

Theoretical implications

Brand coolness represents a crucial attribute behind the preferences of consumers. As consumption patterns are constantly changing, it is expected that brand coolness will have an influence on consumers decisions, attitudes, and behavioural responses (Swaminathan et al. Citation2020; Jiménez-Barreto et al. Citation2022). However, as the concept of coolness is subjective, it is more important than ever to anticipate the choices of consumers and understand their perceptions and tastes.

High-status is a complex construct as status consumption attempts to satisfy both the person’s need for self-recognition and the need for others’ recognition. In the case of the iconic and popularity effect, status consumption associated with coolness drives people not only toward group membership but also to attain social distinction. Cool consumers try to satisfy the need for status by consuming luxuries that other high-status consumers buy and use.

The current research contributes to the marketing and branding literature by exploring the moderated role of iconic and popular BC dimensions on the relationship between utilitarian and hedonic IMs and high-status perceptions. More specifically, utilitarian IMs, which advertise utilitarian products, can be perceived as high-status when they are considered popular. Secondly, this research contributes to the literature by demonstrating the relevance of the iconic and popular dimensions in strengthening the relationship between hedonic products and high-status. Thirdly, the three dimensions of brand coolness reveal to be key in the case of mass cool brands and hedonic products. Finally, this is the first attempt to analyse specific dimensions of brand coolness in the context of hedonic versus utilitarian products as reflected by IMs.

Managerial implications

We also acknowledge the importance of the results to practitioners. First, the popularity of a brand is one of the most important influences in the decision-making process. Thus, brands can use digital marketing channels to enhance popularity through IMs.

Second, in terms of implementing IMs in the marketing strategy, IMs are a simple and engaging way of communicating with consumers. As this communication tool can take many forms and is easily adaptable, the tool is a cool way to promote products. Indeed, it is easy to share among consumers, which increases the chances of going viral on social media.

Third, by understanding which coolness dimensions are associated with each type of internet meme, marketing and brand managers can invest time and money specifically on those dimensions for specific targets. Different consumers need different appeals, brands can empower consumers by providing personalized and unique products or experiences that allow consumers to express their preferences. For example, following our results, it would be interesting for managers to invest in marketing efforts to leverage the iconic factor in hedonic products. This would entail developing communication tools such as instant messaging, photos or videos that promote an iconic message. The communication message is one of the most important tools for a successful positioning strategy. In addition, the content provided by brands should promote interaction with consumers, as a way of encouraging their behaviour towards the brand.

Fourth, managers can categorize their communication practices into dimensions such as popular (bought by many) versus exclusive (bought by few) and carefully craft silent ways of communicating with consumers who develop a preference for utilitarian IMs. For instance, messages can emphasize the normative function of products and/or brands (expressive value, utilitarian, or combination of several); and status messages related to social benefits to distinguish a consumer from the masses (rank recognition) using celebrities.

Finally, while our findings help professionals manage their brands online, it’s important to recognize that the consumer decision-making process is complex and influenced by many other variables (e.g., emotions, traits of personality), especially on social media. Therefore, brands should continually update information regarding their targets so that they can provide the most appropriate content.

Limitations and future research

Despite the positive contribution of our study, it comes with several limitations, which can also be considered as possible suggestions for future research. We analysed the impact of one single meme on the perceptions of high-status. In the future, the study should be repeated with other types of memes. Furthermore, we limited the brands to the personal beauty industry. To extend findings, the same methodology can be applied in different contexts (e.g., with services, food, technology) (Alimamy and Al-Imamy Citation2021; Rojas-Lamorena, Alcántara-Pilar, and Rodríguez-López Citation2021).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to address IMs associated with coolness dimensions. Although it is a very important communication tool, IMs are still overlooked. The digital environment is crucial to the success of a brand and being cool can be a source of competitive advantage (Pham, Valette-Florence, and Vigneron Citation2018; Warren et al. Citation2019; Loureiro, Jimenez, and Romero Citation2020). Pursuing studies on these topics would be beneficial to both academics and practitioners. For example, it would be interesting to analyse the reasons behind each brand’s perceptions of coolness, as well as the impact of product engagement.

Another suggestion, as personal values vary by culture (Czarnecka and Schivinski Citation2019), this model can be used to explore how and whether the association between hedonic/utilitarian IMs with dimensions of coldness varies across different cultures and values (Faschan et al. Citation2020). Measuring the association between internet meme type and perceptions of sustainability would also be beneficial for brands.

Finally, we provide a set of research questions concerning the effects of internet memes on brand coolness: what kind of meme works best for different generations? What type of brands should use IMs in their communication? Are IMs more useful for specific industries, or do they work for all? Are different IMs formats associated with different industries, brands, or targets? Does culture have a positive or negative impact on the association between hedonic/utilitarian products and high-status perceptions? How does conspicuous/inconspicuous consumption influence the relationship between hedonic/utilitarian products and high-status perceptions? Are hedonic and utilitarian products equally associated with sustainability perceptions? Given the new trends and mentalities within the brand coolness subject and digital environment, the topics presented in the study deserve particular attention and further investigation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Aihoor Aleem

Aihoor Aleem is a PhD in Management, with specialization in Marketing Candidate at ISCTE - IUL. Her research activity is focused on luxury trends, consumption and the future of how brands will communicate and create a relationship with their targets. Her background counts with a MSc in Management with specialisation in Strategic Marketing by the Católica Lisbon School of Business and Economics, where she started the research on what influences (or not) consumers to engage into luxury consumption. She has professional experience in academia as a researcher and professor, specifically in teaching marketing strategy, finance applied to marketing and digital marketing (at IADE and invited at ISCTE-IUL, during her PhD).

Sandra Maria Correia Loureiro

Sandra Maria Correia Loureiro, Ph.D., is Professor of Marketing at ISTE-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Portugal. She features on Stanford University’s Top 2% Scientists in Marketing. Her research interests include relationship marketing, tourism marketing, and the VR, AR, and AI adoption in these contexts. Her work has published in journals including Journal of Marketing, Tourism Management, Journal of Travel Research, Journal of Retailing, and Journal of Business Research, among others. She is the recipient of several Best Paper Awards (22019, 2016, and 2012), Highly Commended Paper Awards (20114, 2016), and a 2021 Best Reviewer Award (Psychology & Marketing).

Bruno Schivinski

Dr Bruno Schivinski, Ph.D., MA, BSc, FRSS, FHEA is a sociologist and senior lecturer in Advertising at RMIT University, Australia. He consults for online service providers, websites, and scientific institutions such as the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (MNiSW) and the National Science Centre (NCN) in Poland. Dr. Schivinski is associate editor for SAGE Open and the Journal of Management and Business Administration–Central Europe. Dr. Schivinski specializes in quantitative research methods with focus on multivariate data analysis and generalization methods. His latest work can be found in the Journal of Business Research, Journal of Advertising Research, Industrial Marketing Management, and Journal of Clinical Medicine. His personal website: https:// brunoschivinski.wordpress.com/.

References

- Alba, J. W., and E. F. Williams. 2013. “Pleasure Principles: A Review of Research on Hedonic Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 23 (1): 2–18. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2012.07.003.

- Alimamy, S., and S. Al-Imamy. 2021. “Customer Perceived Value Through Quality Augmented Reality Experiences in Retail: The Mediating Effect of Customer Attitudes.” Journal of Marketing Communications (March) (March) 1–20. doi:10.1080/13527266.2021.1897648.

- Anik, L., J. Miles, R. Hauser (2017). A General Theory of Coolness. Lalin Anik and Johnny Miles and R. Hauser, A General Theory of Coolness. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3027026.

- Belk, R. W. 1988. “Possessions and the Extended Self.” The Journal of Consumer Research 15: 139–168.

- Belk, R. W., K. Tian, and H. Paavola. 2010. “Consuming Cool: Behind the Unemotional Mask.” Research in Consumer Behavior 12: 183–208. doi:10.1108/S0885-2111(2010)0000012010.

- Bellezza, S., and J. Berger. 2020. “Trickle-Round Signals: When Low Status is Mixed with High.” The Journal of Consumer Research 47 (1): 100–127. doi:10.1093/JCR/UCZ049.

- Berger, J., and M. Ward. 2010. “Subtle Signals of Inconspicuous Consumption.” The Journal of Consumer Research 37 (4): 555–569. doi:10.1086/655445.

- Biraglia, A., and J. Brakus. 2020. “Why are Autonomous Brands Cool? The Role of Value Authenticity and Brand Biography.” ACR North American Advances 48: 1048–1051.

- Brand Directory. 2021. “Global 500 2021 Ranking.” Accessed 30 November 2021. https://brandirectory.com/rankings/global/2021/table

- Braun, O. L., and R. A. Wicklund. 1989. “Psychological Antecedents of Conspicuous Consumption.” Journal of Economic Psychology 10: 161–187.

- Brubaker, P. J., S. H. Church, J. Hansen, S. Pelham, and A. Ostler. 2018. “One Does Not Simply Meme About Organizations: Exploring the Content Creation Strategies of User-Generated Memes on Imgur.” Public Relations Review 44 (5): 741–751. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.06.004.

- Bruun, A., D. Raptis, J. Kjeldskov, and M. B. Skov. 2016. “Measuring the Coolness of Interactive Products: The COOL Questionnaire.” Behaviour & Information Technology 35 (3): 233–249. doi:10.1080/0144929X.2015.1125527.

- Buhrmester, M. D., S. Talaifar, and S. D. Gosling. 2018. “An Evaluation of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, Its Rapid Rise, and Its Effective Use.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 13 (2): 149–154. doi:10.1177/1745691617706516.

- Chernev, A. 2004. “Goal–Attribute Compatibility in Consumer Choice.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 14 (1–2): 141–150.

- Czarnecka, Barbara, and Bruno Schivinski. 2019. “Do Consumers Acculturated to Global Consumer Culture Buy More Impulsively? The Moderating Role of Attitudes Towards and Beliefs About Advertising.” Journal of Global Marketing 32 (4): 219–238. doi:10.1080/08911762.2019.1600094.

- Dar-Nimrod, I., I. Hansen, T. Proulx, D. Lehman, B. Chapman, and P. Duberstein. 2012. “Coolness: An Empirical Investigation.” Journal of Individual Differences 33 (3): 175–185. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000088.

- Deb, M., and E. Lomo-David. 2020. “On the Hedonic versus Utilitarian Message Appeal in Building Buying Intention in the Luxury Hotel Industry.” Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 45: 615–621. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.10.015.

- Dhar, R., and K. Wertenbroch. 2000. “Consumer Choice Between Hedonic and Utilitarian Goods.” Journal of Marketing Research 37 (1): 60–71. doi:10.1509/jmkr.37.1.60.18718.

- Dion, D., and S. Borraz. 2017. “Managing Status: How Luxury Brands Shape Class Subjectivities in the Service Encounter.” Journal of Marketing 81 (5): 67–85. doi:10.1509/jm.15.0291.

- Dubois, D., S. Jung, and N. Ordabayeva. 2021. “The Psychology of Luxury Consumption.” Current Opinion in Psychology 39: 82–87. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.07.011.

- Eastman, J. K., R. E. Goldsmith, and L. R. Flynn. 1999. “Status Consumption in Consumer Behavior: Scale Development and Validation.” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 7: 41–51.

- Eckhardt, G. M., R. W. Belk, and J. A. J. Wilson. 2015. “The Rise of Inconspicuous Consumption.” Journal of Marketing Management 31 (7–8): 807–826. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2014.989890.

- Faschan, M., C. Chailan, and R. Huaman-Ramirez. 2020. “Emerging Adults’ Luxury Fashion Brand Value Perceptions: A Cross-Cultural Comparison Between Germany and China.” Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 11 (3): 207–231. doi:10.1080/20932685.2020.1761422.

- Faul, F., E. Erdfelder, A. Buchner, and A.-G. Lang. 2009. “Statistical Power Analyses Using G*power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses.” Behavior Research Methods 41 (4): 1149–1160. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149.

- Field, A.2017. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. 5th ed. Sage Publications. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04270_1.x.

- Goffman, E. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Goodman, J. K., C. E. Cryder, and A. Cheema. 2013. “Data Collection in a Flat World: The Strengths and Weaknesses of Mechanical Turk Samples.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 26 (3): 213–224. doi:10.1002/bdm.1753.

- Grayson, K., and R. Martinec. 2004. “Consumer Perceptions of Iconicity and Indexicality and Their Influence on Assessments of Authentic Market Offerings.” The Journal of Consumer Research 31 (2): 296–312. doi:10.1086/422109.

- Griskevicius, V., J. M. Tybur, and B. Van den Bergh. 2010. “Going Green to Be Seen: Status, Reputation, and Conspicuous Conservation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98 (3): 392–404. doi:10.1037/a0017346.

- Hayes, A. F. 2013. An Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press.

- Hayes, AF. 2015. ”An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation.” Multivariate Behavioral Research 50 (1): 1–22. PMID: 26609740. doi:10.1080/00273171.2014.962683.

- Hayes, A. F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (Methodology in the Social Sciences). 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Hirschman, E. C., and M. B. Holbrook. 1982. “Hedonic Consumption: Emerging Concepts, Methods and Propositions.” Journal of Marketing 46 (3): 92–101. doi:10.1177/002224298204600314.

- Holt, D. B. 2004. How Brands Become Icons: The Principles of Cultural Branding. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Jenkins, H., R. Purushotma, M. Weigel, K. Clinton, and A. J. Robison. 2009. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Jiménez-Barreto, J., S. M. C. Loureiro, N. Rubio, and J. Romero. 2022. “Service Brand Coolness in the Construction of Brand Loyalty: A Self-Presentation Theory Approach.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 65. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102876.

- Kang, J., and H. Park‐poaps. 2010. “Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Motivations of Fashion Leadership.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 14 (2): 312–328.

- Kastanakis, M. N., and G. Balabanis. 2012. “Between the Mass and the Class: Antecedents of the “Bandwagon” Luxury Consumption Behavior.” Journal of Business Research 65 (10): 1399–1407. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.005.

- Kastanakis, M. N., and G. Balabanis. 2014. “Explaining Variation in Conspicuous Luxury Consumption: An Individual Differences’ Perspective.” Journal of Business Research of Business Research 67 (10): 2147–2154. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.04.024.

- Ki, C., K. Lee, and Y. K. Kim. 2017. “Pleasure and Guilt: How Do They Interplay in Luxury Consumption?” European Journal of Marketing 51 (4): 722–747. doi:10.1108/EJM-07-2015-0419.

- Kim, S., K. Park, and L. J. Shrum. 2022. “Cause‐related Marketing of Luxury Brands: Nudging Materialists to Act Prosocially.” Psychology & Marketing 39 (6): 1204–1217. doi:10.1002/mar.21648.

- Kline, R. B. 2011. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 3rd ed. New York, USA: The Guilford Press.

- Kumagai, K., and S. Y. Nagasawa. 2021. “Moderating Effect of Brand Commitment on Apparel Brand Prestige in Upward Comparisons.” Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 12 (3): 195–213. doi:10.1080/20932685.2021.1912630.

- Lascu, D. N., and G. Zinkhan. 1999. “Consumer Conformity: Review and Applications for Marketing Theory and Practice.” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 7 (3): 1–12.

- Latter, C., I. Phau, and C. Marchegiani. 2010. “The Roles of Consumers Need for Uniqueness and Status Consumption in Haute Couture Luxury Brands.” Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 1 (4): 206–214. doi:10.1080/20932685.2010.10593072.

- Li, J., A. Abbasi, A. Cheema, and L. B. Abraham. 2020. “Path to Purpose? How Online Customer Journeys Differ for Hedonic versus Utilitarian Purchases.” Journal of Marketing 84 (4): 127–146. doi:10.1177/0022242920911628.

- Lonnberg, A., P. Xiao, and K. Wolfinger. 2020. “The Growth, Spread, and Mutation of Internet Phenomena: A Study of Memes.” Results in Applied Mathematics 6: 100092. doi:10.1016/j.rinam.2020.100092.

- Loureiro, S. M. C., J. Jimenez, and J. Romero. 2020. “Enhancing Brand Coolness Though Perceived Luxury Values: Insight from Luxury Fashion Brands.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 57: 102211. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102211.

- Lu, J., Z. Liu, and Z. Fang. 2016. “Hedonic Products for You, Utilitarian Products for Me.” Judgment and Decision Making 11 (4): 332–341.

- Makkar, M., and S. F. Yap. 2018. “Emotional Experiences Behind the Pursuit of Inconspicuous Luxury.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 44: 222–234. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.07.001.

- Mason, R. 1992. Modelling the Demand for Status Goods. ACR Special Volumes.

- Milner, M. 2013. Freaks, Geeks, and Cool Kids. New York: Routledge.

- Mohiuddin, K. G. B., R. Gordon, C. Magee, and J. K. Lee. 2016. “A Conceptual Framework of Cool for Social Marketing.” Journal of Social Marketing 6 (2): 121–143.

- Nancarrow, C., P. Nancarrow, and J. Page. 2003. “An Analysis of the Concept of Cool and Its Marketing Implications. Journal of Consumer Behaviour:.” An International Research Review 1 (4): 311–322. doi:10.1002/cb.77.

- Napoli, J., S. J. Dickinson, M. B. Beverland, and F. Farrelly. 2014. “Measuring Consumer-Based Brand Authenticity.” Journal of Business Research 67 (6): 1090–1098. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.06.001.

- Nelissen, R. M. A., and M. H. C. Meijers. 2011. “Social Benefits of Luxury Brands as Costly Signals of Wealth and Status.” Evolution and Human Behavior 32 (5): 343–355. doi:10.1016/J.EVOLHUMBEHAV.2010.12.002.

- Nieubuurt, J. T. 2021. “Internet Memes: Leaflet Propaganda of the Digital Age.” Frontiers in Communication 5: 547065. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2020.547065.

- Nikhashemi, S. R., and E. Delgado-Ballester. 2022. “Branding Antecedents of Consumer Need for Uniqueness: A Behavioural Approach to Globalness Vs. Localness.” Journal of Marketing Communications 28 (4): 392–427. doi:10.1080/13527266.2021.1881807.

- O'Cass, A., and E. McEwen. 2004. “Exploring Consumer Status and Conspicuous Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Behavior 4 (1): 25–39. doi:10.1002/cb.155.

- O’Donnell, K. A., and D. L. Wardlow. 2000. “A Theory on the Origins of Coolness.” ACR North American Advances 27: 13–18.

- Packard, V. 1959. The status seekers. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Pham, M., P. Valette-Florence, and F. Vigneron. 2018. “Luxury Brand Desirability and Fashion Equity: The Joint Moderating Effect on Consumers’ Commitment Toward Luxury Brands.” Psychology & Marketing 35 (12): 902–912. doi:10.1002/mar.21143.

- Pino, G., C. Amatulli, A. M. Peluso, R. Nataraajan, and G. Guido. 2019. “‘Brand Prominence and Social Status in Luxury Consumption: A Comparison of Emerging and Mature Markets’.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 46: 163–172. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.11.006.

- Potter, A., and J. Heath. 2004. Nation of Rebels: Why Counterculture Became Consumer Culture. New York: Harper Business.

- Ranking the brands. 2021. “Best Global Brands 2021 by Interbrand.” Accessed 30 November 2021. https://www.rankingthebrands.com/The-Brand-Rankings.aspx?rankingID=37

- Rojas-Lamorena, A. J., J. M. Alcántara-Pilar, and M. E. Rodríguez-López. 2021. ”The Relationship Between Brand Experience and Word-Of-Mouth in the TV-Series Sector: The Moderating Effect of Culture and Gender.” Journal of Marketing Communications. 10.1080/13527266.2021.2011376. December 1–22.

- Runyan, R. C., M. Noh, and J. Mosier. 2013. “What is Cool? Operationalizing the Construct in an Apparel Context.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 17 (3): 322–340.

- Schivinski, B., D. Langaro, T. Fernandes, and F. Guzmán. 2020. “Social Media Brand Engagement in the Context of Collaborative Consumption: The Case of AIRBNB.” Journal of Brand Management 27 (6): 645–661. doi:10.1057/s41262-020-00207-5.

- Septianto, F., Y. Seo, B. Sung, and F. Zhao. 2020. “Authenticity and Exclusivity Appeals in Luxury Advertising: The Role of Promotion and Prevention Pride.” European Journal of Marketing 54 (6): 1305–1323. doi:10.1108/EJM-10-2018-0690.

- Shahid, S., J. Paul, F. G. Gilal, and S. Ansari. 2022. “The Role of Sensory Marketing and Brand Experience in Building Emotional Attachment and Brand Loyalty in Luxury Retail Stores.” Psychology & Marketing 1–15. doi:10.1002/mar.21661.

- Sharma, A., Y. K. Dwivedi, V. Arya, and M. Q. Siddiqui. 2021. “Does SMS Advertising Still Have Relevance to Increase Consumer Purchase Intention? A Hybrid PLS-SEM-Neural Network Modelling Approach.” Computers in Human Behavior 124: 106919. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2021.106919.

- Siepmann, C., L. C. Holthoff, and P. Kowalczuk. 2022. “Conspicuous Consumption of Luxury Experiences: An Experimental Investigation of Status Perceptions on Social Media.” Journal of Product and Brand Management 31 (3): 454–468. doi:10.1108/JPBM-08-2020-3047.

- Skitovsky, T. 1992. The Joyless Economy. NY: Oxford University Press.

- Statista. 2021. Instagram Statistics and Facts. Accessed 25 November 2021. https://www.statista.com/topics/1882/instagram/#dossierKeyfigures

- Sundar, S. S., D. J. Tamul, and M. Wu. 2014. “Capturing “Cool”: Measures for Assessing Coolness of Technological Products.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 72 (2): 169–180. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2013.09.008.

- Sung, B., and I. Phau. 2019. “When Pride Meets Envy: Is Social Superiority Portrayal in Luxury Advertising Perceived as Prestige or Arrogance?” Psychology & Marketing 36: 113–119. doi:10.1002/mar.21162.

- Suzuki, S., and S. Kanno. 2022. “The Role of Brand Coolness in the Masstige Co-Branding of Luxury and Mass Brands.” Journal of Business Research 149: 240–249.. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.04.061.

- Swaminathan, V., A. Sorescu, J.-B. E. M. Steenkamp, T. C.G. O’Guinn, and B. Schmitt. 2020. “Branding in a Hyperconnected World: Refocusing Theories and Rethinking Boundaries.” Journal of Marketing 84 (2): 24–46. doi:10.1177/0022242919899905.

- Tiwari, A. A., A. Chakraborty, and M. Maity. 2021. “Technology Product Coolness and Its Implication for Brand Love.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 58: 102258. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102258.

- Tong, S. C. July 2021. ”Public Relations Practice in the Digital Era: Trust and Commitment in the Interplay of Interactivity Effects and Online Relational Strategies.” Journal of Marketing Communications 1–21. doi:10.1080/13527266.2021.1951814.

- Vasquez, C., and E. Aslan. 2021. “Cats Be Outside, How About Meow”: Multimodal Humour and Creativity in an Internet Meme.” Journal of Pragmatics 171: 101–117.

- Wang, L., and B. C. Wood. 2011. “An Epidemiological Approach to Model the Viral Propagation of Memes.” Applied Mathematical Modelling 35 (11): 5442–5447. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2011.04.035.

- Warren, C. 2010. “What Makes Things Cool and Why Marketers Should Care.” Doctoral dissertation, Department of Marketing, University of Colorado, Boulder.

- Warren, C., R. Batra, S. M. C. Loureiro, and R. P. Bagozzi. 2019. “Brand Coolness.” Journal of Marketing 83 (5): 36–56. doi:10.1177/0022242919857698.

- Warren, C., and M. C. Campbell. 2014. “What Makes Things Cool? How Autonomy Influences Perceived Coolness.” The Journal of Consumer Research 41 (2): 543–563. doi:10.1086/676680.

Appendix

Figure A1. Stimuli: Hedonic and Utilitarian Meme.