ABSTRACT

As Syrian refugee numbers in Lebanon have increased, so has the hostility directed towards them, with targeted attacks against informal encampments and public restrictions on Syrian mobility through localized curfews and military checkpoints. The Syrian experience is constrained by both their precarity as refugees and the volatility of Lebanese urban politics. Syrians must navigate the complex terrain of moral and socio-spatial Lebanese boundaries: when to keep silent or remain publicly invisible, how to navigate sectarian street dynamics, and how to respond to heightened public sensibilities. This article, based on six months ethnographic research (2017–2018) among Syrian refugees in Tripoli (Bab al-Tabbaneh) and Beirut (Nab’a) examines how Syrian refugees navigate Lebanese urban spatial realities—adapting and responding to its complex hybrid sovereignties, sectarian atmospheres and everyday security practices. The findings attest to how Syrian refugees seek ‘security within borders’ through practices of rootedness, invisibility and ‘safe space’ boundary marking, while also accepting that crossing boundaries—physical military checkpoints and immaterial social barriers—can result in public confrontations, detention, and violence. Although Syrian refugees attempt to remain apolitical and deliberately disengaged from Lebanese sectarian networks of power, their everyday choices (rent, electricity fees) and physical presence connect them to local political contests and rivalries.

Introduction

I don’t leave the area very much, but my husband and my son do, and they say there are aggravations, problems. Sometimes they can deal with it and sometimes they can’t. They want to talk back, but you won’t be harassed if you stay within the morals [adab], inside the boundaries [ḥudūd]. You can’t cross the boundaries.Footnote1

The everyday spatial behaviour of Syrian migrants in Lebanon is constrained and restricted by both their precarity as refugees and the volatility and sensitivity of Lebanese urban politics. As Batul, a middle-aged mother from Homs now living in Tripoli confides, Syrians must navigate the complex terrain of moral and socio-spatial Lebanese boundaries: when to keep silent or remain publicly invisible, how to navigate sectarian street dynamics, when to risk crossing military or police checkpoints, and how to respond to heightened public sensibilities. As Syrian migrant numbers in Lebanon have increased (now around 1.5 million, a quarter of the whole Lebanese populationFootnote2), so has the hostility directed towards them, with direct attacks against informal encampmentsFootnote3 and public restrictions on Syrian mobility through localized curfews, military checkpoints, limiting access to public space and transport between cities.Footnote4

Although growing research has been directed towards Syrian urban refugee experiences, often drawing on discursive frames of ‘securitization’Footnote5 or ‘self-reliance’,Footnote6 less attention has been focused on spatialized practices and the way in which Syrian (im)mobility reflects a dynamic everyday engagement with city spaces, local histories, and assemblages of power. This article seeks to examine how Syrian refugees navigate Lebanese urban spatial realities—adapting and responding to its complex hybrid sovereignties,Footnote7 sectarian atmospheres and everyday security practices. The precarity of Syrian migrant lives is exacerbated by Lebanon’s urban fragility in which intrusive security measures (tanks, barriers, checkpoints) and territorial marking (posters, flags, surveillance cameras) continue to fragment and demarcate streets, neighbourhoods and public spaces.Footnote8

The findings of this article are based on six months of ethnographic research, carried out during 2017–2018 with Syrian refugees in Lebanon’s capital, Beirut and its second largest city, Tripoli. More than a third of all registered Syrian refugees (851,717) reside either in Tripoli or Beirut,Footnote9 while over half a million Syrian refugees in Lebanon lack legal papers or UNHCR registration.Footnote10 The authors conducted over 40 in-depth interviews of refugees (25 female and 15 maleFootnote11) split equally between Beirut and Tripoli, also incorporating narrated guided walks and participant observation of Syrians at community centres, humanitarian agencies and NGOs. Participants were identified and approached through local NGOs and snowballing techniques; interviews were conducted in Arabic in settings chosen by the participants and later transcribed by the authors. Given the sensitivity of the topic, interviewees’ names have been changed to offer anonymity. The ethnographic research approach encouraged Syrian narratives and stories to emerge, often grounded and linked to their surrounding topography and elicited through refugee led walks around their neighbourhoods. This interview data was contextualized and triangulated with humanitarian reports, local media accounts and scholarly research on Syrian refugees in Lebanon.Footnote12

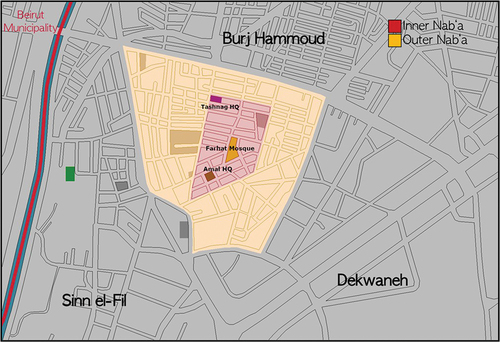

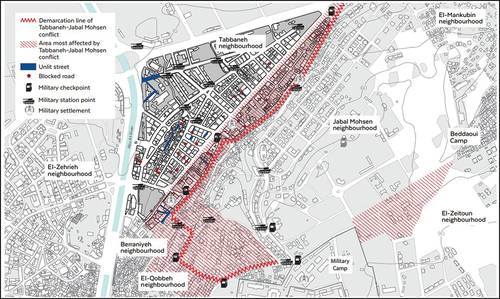

The research focuses on two diverse urban Lebanese settings: Nab’a in Beirut and Bab-al-Tabbaneh in Tripoli. Both contexts provide fascinating comparative backdrops to observe Syrian refugee dynamics intertwined within local power struggles and communal realities. Nab’a, a poor densely populated neighbourhood of Bourj Hammoud in Eastern Beirut, is notable for its religious and ethnic diversity (Shi’a Muslim, Maronite, Armenian and Kurd) and clientelist networks established through political parties—Hizbullah, Amal, Lebanese Forces and Tashnag (the Armenian Revolutionary Federation) and is now home to Syrian refugees who make up the largest demographic estimated at 63% of the population.Footnote13 Syrians represent the latest and largest influx of migrant labour to this dynamic neighbourhood, but they must negotiate sectarian infrastructures and power networks, while seeking to remain invisible and detached from the ongoing Syrian conflict.Footnote14 Tripoli, Lebanon’s Sunni-majority second city, similarly hosts a large number of Syrian refugees, many of whom live in socially deprived and under-invested eastern suburbs of Bab-al-Tabbaneh. Tripoli has deep historic cultural and economic ties to Syria, but intercommunal violence between religiously conservative Sunni Bab al-Tabbaneh and the neighbouring Alawi enclave of Jabal Mohsin has been exacerbated by Syrian military and Ba’athist incursions during the Lebanese civil war (1975–1990)Footnote15 and Islamist opposition fighters fleeing the ongoing conflict in Syria (2011-).Footnote16

This article examines both the spatial claims and urban practices of Syrian refugees, recognizing that a Lefebvrian ‘right to the city’Footnote17 is often subsumed beneath the demands and restrictions that urban networks of power impose upon its inhabitants. Drawing on Mohamad Hafeda’s conception of bordering practices in Beirut, it recognizes that boundaries (material, immaterial) within Lebanon are simultaneously arbitrary and dynamic, temporal and intransigent, rhizomatic and polysemic, responsive to, and reflective of ‘political affiliation, the social, cultural, and religious differences, and the geographic location of city dwellers as they engage in the spatial practices of everyday lives in cities of conflict’.Footnote18 Just as Lebanese residents must negotiate urban borders of surveillance and sectarian demarcation, Syrian refugees are similarly subject to neighbourhood security and a public gaze which crosses into private spaces and daily encounters.

This research reveals how urban Syrian migrants in Lebanon prefer to remain invisible and anonymous, often retreating within narrow cloistered neighbourhoods, avoiding as far as possible any public encounter with local authorities or political groups. Their vulnerable status and lack of communal protection makes them dependent on initial economic networks and reluctant to move around Lebanon. Refugee mobility is influenced by a number of key factors: gender, class, ethnicity, religion, residency permits; but personal safety and security remains the pre-eminent consideration, with interviewees creating mental maps of ‘so-called safe spaces’Footnote19 in which they can navigate cautiously. While Syrian households are often located in marginalized low-income suburbs, providing cheaper housing, employment opportunities and less state scrutiny, this comes at the cost of limited public services, higher crime, and localized militia policing. Our findings suggest that although Syrian migrants may attempt to remain apolitical and deliberately disengaged from Lebanese sectarian networks of power, their everyday choices (rent, electricity fees, shopping) and physical presence connect them to local political contests and rivalries, just as their displacement indelibly links them to the unresolved conflict in Syria.

This paper initially outlines Lebanon’s shifting policy towards Syrian migrants, providing a historic context to then situate relevant literature on refugee mobility and urban spatial practice. What is emerging is perhaps less growing demands for a refugee ‘right to the city’ but rather tactical and temporal practices to merely inhabit and navigate Lebanese streets. The following empirical sections examine how Syrians negotiate Beirut and Tripoli’s urban divides through an elusive search for ‘security within borders’ through practices of rootedness, invisibility and ‘safe space’ boundary marking, while accepting that crossing boundaries—physically and socially—can result in public confrontations, detention, and targeted violence.

Syrians in Lebanon: a contextual overview

The lives of Syrians in Lebanon are complicated by the legacies of overlapping factors: deep historic social ties and porous borders; a constant Syrian migrant labour force; Syrian military intervention during the Lebanese civil war and occupation until 2005; and the ongoing political and economic fallout of the Syrian conflict.Footnote20 Historically, Syrian migrants have been a significant presence in Lebanon, constituting a majority of workers in construction and agriculture. Syrian workers are seasonal and predominantly male, and the Lebanese government maintained an open border policy despite occasional cosmetic policy changes.Footnote21 Even during the Lebanese Civil War (1975–90), Syrians living in Lebanon never fled en masse, and instead their numbers increased with the Syrian Post-Ta’if military presence (1990–2005). Due to general Lebanese discontent that Syrian workers undermined the Lebanese workforce and collaborated with Syrian military and intelligence services, migrants were often subject to public disdain, harsh working conditions and offered very little protection by either government. During moments of Lebanese political tension Syrian workers were often subject to attacks and communal pressure resulting in migrant flows back to Syria. For example, large numbers of Syrian workers left Lebanon in the face of attacks after Prime Minister Rafik Hariri’s assassination in 2005 and a similar exodus occurred when the Israeli army launched an assault on Lebanon in 2006.Footnote22

Lebanon’s shifting refugee policy

Since the beginning of the uprising in Syria in 2011, over 1.5 million Syrians have fled to Lebanon and have been subject to shifting Lebanese policy and practice. The initial ‘no policy policy’Footnote23 which rejected Syrian refugee status, formal refugee camps or representation, was replaced with an increasingly restrictive Lebanese approach which entailed limited residency permits, worker sponsorship (kafala) and repatriation in co-ordination with the Syrian authorities.Footnote24 Syrian refugees became entangled in a complex web of regulations and permits, which were deliberately opaque and often carried a significant financial burden. Nora Stel argues this Lebanese approach amounts to strategic ambiguity or governance through uncertainty, in which refugees are stripped of legal and political protection and are instead subject to abuse and exploitation by landlords, sponsors, politicians and security agents.Footnote25 Consequently, Syrian migrants in Lebanon have been forced to navigate both Lebanon’s traumatic past and its uncertain present, circumventing divisive urban border practices that Hafeda describes as “waiting for a trouble that is ‘about to happen’ while accepting that ‘recurrence and the state of being on hold’ characterize Lebanon’s daily reality.Footnote26

Research methods

The Syrian migrants in this study occupy both a liminal legal space and a precarious spatial existence. Anya Cardwell draws on a Lefebvrian ‘Right to the City’ framework to suggest an emerging Syrian ‘Right to Inhabit’ in Lebanon, in which particularly Syrian refugee women struggle for ‘rights to housing, property and urban social life’ amidst patriarchal power relations and clientelist political dynamics.Footnote27 The Syrians interviewed in this study were reluctant to make visible claims to Lebanese urban spaces (individually or collectively) but settled instead for invisible or hidden spaces they could inhabit without being integrated within Lebanese sectarian dynamics or local rivalries. Our research, conducted over 6 months (2017–2018) in Tripoli (Bab al-Tabbaneh) and Beirut (Nab’a) combines 40 in-depth interviews, guided walks and observation at refugee hubs (NGO aid centres). Interviews were split equally between both sites and a small number of interviewees (5) agreed to follow up guided walks, in which they narrated their urban setting. This research approach encouraged ‘empathetic witnessing’Footnote28 while providing both insight into daily spatial encounters and how the landscape evokes migrant memories of home, loss and dislocation. Our research provides a complex and compelling picture of the Syrian refugee struggle to navigate Lebanese boundaries and barriers.

Refugee precarity

For most Syrian interviewees, life in Lebanon remains unsafe, uncertain and insecure. Some spoke of existential weariness (ta’b) or the daily pressure (ḍaǧṭ) of simply getting by; as Nur, a Syrian student in his mid-twenties living in Tripoli, explains ‘As a Syrian, you don’t know what’s going to happen to you tomorrow’.Footnote29 For Karima, the challenge of Lebanon is less temporal and more relational, ‘you don’t know who is your enemy and who is your friend’.Footnote30 One consequence of such precarity and mistrust is that Syrians limit mobility and public visibility, choosing to remain in the neighbourhood of their first entry, seeking to delineate between safe areas and potentially dangerous spaces.

While Syrian migrants are dispersed all over Lebanon, often their choice of location is due to family connections, social networks or previous seasonal employment.Footnote31 Within Nab’a’s dynamic migrant population, a Syrian Kurdish and Syrian Armenian community already had established a presence before the Syrian conflict began in 2011. These communities became important hosts and intermediators, for Syrians whose sudden displacement left them ill-equipped and unprepared for life in Lebanon. Nawal, an educated Syrian Kurdish teacher in her mid-forties who lived alone in Nab’a with her teenage son, having sent her husband and two other children to Germany, explains her traumatic arrival in Beirut.

We stayed with my husband’s niece, who was here [in Nab’a] … We went into a sort of entry room, off the corridor, and immediately to a room on the ground floor. I said to her, ‘This is your house?’ She said, ‘Yes’. I said, 'This room is the whole house?' She said, 'Yes.' And I started to cry. I had imagined that I would be living in my own room. I had no idea that I would have to be living like this.Footnote32

Nawal’s humiliation was further compounded by frequent house moves within Nab’a due to building defects, persistent damp and insect infestations. Approximately 93% of Nab’a housing is private rental, controlled by a small number of realtors and absentee landlords, who are driving up rental costs but providing truncated housing with limited services based on unwritten contracts.Footnote33 Several interviewees confirmed the need for multiple moves within the neighbourhood due to poor housing and unscrupulous landlords. As Darling reminds us, too frequently refugee dispersal is treated as a self-contained process in which displaced people themselves, as well as the urban space around them, are not invested with sufficient agency to shape the process.Footnote34 Syrian migrant experiences certainly attest to housing precarity but also reveal that few Syrians are willing to risk leaving the familiar locales and social connections initially established. The only exception to this was in extreme cases of personal security, with one interviewee, Shadi, a man in his late twenties from Aleppo, leaving Beirut’s southern suburbs and moving to Tripoli in order to escape the attention of Shi’a militia groups.Footnote35

Seeking security within borders

Rootedness and invisibility

Syrian rootedness to particular neighbourhoods is often a consequence of education and aid provision. By late 2012, Lebanese public schools offering separate afternoon sessions for Syrian children became oversubscribed, forcing Syrian students to travel further afield, pay private school fees, or drop out of education altogether. Local networks and individual connections, however, were often able to circumvent these restrictions, especially for families who arrived in Lebanon during the first few years of the conflict, while the education situation was still fluid. In Tripoli this was particularly true, as many ‘Syrians have been in Tripoli longer than the Syrian conflict and are therefore often seen as part of the local population’.Footnote36 Syrians Afaf and Yasmin, based in Bab al-Tabbaneh, as well as their sister Farah, who resided in the Palestinian camp at Beddawi, were all able to enrol their children together in mixed sessions (Lebanese-Syrian) at a public school in Abu Samra, an adjoining neighbourhood of Tripoli.Footnote37 As the dual-session system arose and solidified, it did so around the individual provisions many Syrians had already made, rather than replacing them. For such families, there was nothing to be gained by moving to a different area of the country, where the contacts they had built up with schools and other local services would be squandered. In Nab’a five private schools (Mar Takla, Mar Sarkis, Al Tarakki, Al Mowaten, Mar Maroun) also provided limited spaces for Syrians, but these were often constrained by religious affiliation or the ability of families to pay private fees.

In both sites, Syrians were heavily reliant on local NGOs and aid providers, which had visible offices that recipients could attend, but more often staff would visit Syrians in their homes. As Ahmed, a father of four from Idlib explains, ‘It’s better they bring aid here [to this house], rather than standing around waiting in long queues on the street. It’s safer and we are not watched as much. It protects the little dignity we have left’.Footnote38 Accompanied house visits alongside NGO staff confirmed Syrian sedentary and restrictive lifestyles, as unannounced visits never resulted in family absences. Similar studies of Syrian communities in Lebanon confirms that they are almost never absent: Lyles et al., for instance, visited over 2,000 households without prior notice and found an absence rate of only 1.9%.Footnote39 Most of the time, Syrians are siloed in their own homes, disconnected from each other and lacking any social space in which to gather or meet.

A UN Habitat 2017 report on the Nab’a neighbourhood highlights how the dense urban fabric, illegal buildings, and lack of public space contributes to the neighbourhood’s chaotic and volatile atmosphere. Understandably, Syrian women feel unsafe to traverse its unlit streets at night, but men and youth are also wary of public gatherings as an overwhelming ‘sense of insecurity at night is prevalent due to fights in the streets, gang gatherings, alcohol and drug abuse and weapon possession especially amongst young men’.Footnote40 By day Syrians also admitted frustration at the lack of accessible green spaces in Beirut and Tripoli, some of which are privately guarded or prohibited from use by Syrians. The Dahr al-Jamal public park in Sinn al-Fil, containing a flower garden and a children’s playground, is fenced off, and Syrian families are barred from entering it by a security guard.

Moral and social spatial boundaries

For many Syrian refugees, spatial exclusion is not only publicly enforced but privately preferred—a deliberate moral and social response to avoid the Lebanese gaze and awkward public encounters. Syrian interviewees expressed social discomfort and unease at visiting shopping malls, civic squares (Beirut Downtown), and even mosques for Friday prayers. In Tripoli, the bombings of Taqwa and Salam mosques in 2013 created an anti-Syrian backlash which affected Syrian public religious attendance in the city. In Nab’a, the majority Sunni Syrian migrants are hindered instead by sectarian dynamics, as the main neighbourhood mosque, al-Farḥāt, is Shi’a and associated with Hizbullah. Few interviewees left the neighbourhood to attend a Sunni Mosque; most preferred to pray privately in the safety of their homes. Fear, mistrust and uncertainty encourage Syrian religious insularity, as Ziad from Dar’a explains, ‘In Lebanon you never know who runs this mosque and what hizb (party) they belong to and what their position on Syria is’.Footnote41 A Lebanese Sunni Cleric and Islamic court judge suggests that while Syrian displaced imams have been asked to ‘preach and support migrants in informal settlements’ many refugees are distanced from their faith—‘it is more culture and customs than real faith obligations’. His personal experience of the destructive impact and legacy of the war on Syrian refugee families, with increasing domestic violence and high numbers of women divorcing their husbands though the Islamic court system lead him to a stark warning: ‘I believe that now [in Lebanon] the Syrian family has collapsed. Even if the war is finished tomorrow, the Syrian family, Syrian relationships on social and family level are destroyed for 30 or 40 years’.Footnote42

Given the pervasive feeling of insecurity and pressure on everyday family life, some Syrians concluded that moving around the neighbourhood puts them in no more danger than simply sitting at home. Amirah, who lived in an Armenian-owned house in western Nab’a, said that on her local walks with her husband ‘we try to extend the route’ [nḥāwil nṭawwil al-ṭarīq], and widen the area of the neighbourhood they are used to inhabiting.Footnote43 The habit of taking walks to relax and expand urban familiarity could also be read as an example of Bayat’s quiet encroachment of the ordinary.Footnote44 Those interviewees who were willing to engage in walking for leisure, however, were a minority, particularly in Tripoli. They were also highly aware of which areas were more insecure and to be avoided. Their practice reflects the existence of a graded scale of safety and moral sensibilities around which Syrian understanding of space was structured.

Imagining ‘safe spaces’ within sectarian street dynamics

The logic of sectarianism remains one of the underlying principles for how post-war Lebanese society and politics are organized, feeding into the production of urban space and spatial mobility. Everyday Sectarianism, as Joanne Nucho explains, is not found in timeless religious conflict, but in temporal urban infrastructures and modes of differentiation:

In Lebanon, the relationship between infrastructures in urban spaces and sectarianism is dialogic – many urban infrastructures and services are produced by sectarian political and religious organizations at the same time that they are the channels through which sectarian belonging and exclusion are experienced, produced and recalibrated.Footnote45

Sectarianism is therefore embedded in Lebanese streets through services, networks, discourses, and visual topography through which sectarian actors stake claims to territorial control, political jurisdiction and religious hegemony. Residents in Lebanon learn how to navigate or negate these spaces, judging threat and appropriate behaviour, and adapting their use of and movement around such urban spaces.Footnote46 Despite having spent several years immersed in Lebanon’s sectarianized urban environment, and although they are familiar with the boundaries and identities it produces, Syrians have not yet internalized it into their way of thinking about the city. Syrian imagined boundaries in Nab’a and Bab al-Tabbaneh are not based solely on sectarian readings but are guided by safety-based understandings which also intersect with class, gender and refugee status.

In Nab’a Syrian interviewees distinguish between inner (juwwa) Nab’a and outer (barra) Nab’a, despite the lack of explicit boundary markers or clear religio-political borders (See ). The differentiation between juwwa and barra instead describes a spatial distribution of power: Syrians feel a more acute sense of their own precarity in ‘inner’ Nab’a, due to its association with social unrest and surveillance given the presence of three political party headquarters (Amal, Tashnag and Hizbullah linked to al-Farḥāt Mosque). As Nawal explained that ‘I don’t live far inside [juwwa] Nab’a, because basically I’m afraid to live in Nab’a, in the centre of Nab’a. I feel that it’s not very safe’.Footnote47 Layla, who had fled the Damascus suburb of Mezzeh with her husband early in the conflict, lived above the office of a Syrian-run NGO where she worked. She insisted that ‘this area is considered Dekwaneh or Bourj Hammoud more than Nab’a. But beyond this street, going inside (juwwa), that’s considered Nab’a … There are clashes and conflict, but in the interior of Nab’a’.Footnote48 This imaginary division may serve as a narrative device for Syrians to create security buffers, class differentiation or distance themselves from sectarian linkages.

Elind, a Syrian Kurd from Afrin, distinguishes her home as being on the outskirts of Nab’a, distinct physically and socially from inner Nab’a; ‘The neighbourhoods [in juwwa] are very like slums, they’re very narrow. In our neighbourhood, for example, it is more structured, it’s light, there are some trees, nature’.Footnote49 The housing distinction that Elind suggests is not so apparent. The UN-Habitat report on Nab’a affirms that 38% of housing in the whole district is substandard/critical condition (67% of which is rented by Syrians) and most need better electricity, water supply and waste disposal.Footnote50 Site observation suggests the most visible distinction between these two areas is the density of sectarian markings (flags, posters) and the large numbers of men outside cafes and shops who provide a visible layer of public social surveillance. The guided walk interviews confirmed Syrian spatial boundary making in Nab’a, with those who lived barra preferring to stick to the outer limits of the neighbourhood, and those who lived juwwa walking directly to their homes without any detours. These walking itineraries mirror a broader feature of Lebanese urban mobility which Lefort labels everyday ‘strategies of adaption’, in which city residents seek to circumvent disorder and securitization by taking routes which restrict and inhibit their own movement.Footnote51

In Tripoli, Syrian interviewees distinguished between sha’bī (literally, popular, but also meaning common or ordinary) neighbourhoods and more unfriendly or hostile districts, with socio-economic cleavages appearing to trump religio-political apprehensions. This is in part a consequence of Tripoli’s religious demographics (the city is 90% Sunni) and its historic proximity to Syria, which allows easier cultural integration of Syrian refugees. Nur, a Homsi man in his mid-twenties, who shares an apartment with three other Syrian men in Qobbeh, a socio-economically marginalized and relatively insecure part of eastern Tripoli, describes the neighbourhood as sha’bī, saying ‘there’s a lot of familiarity, charity between people … in sha’bī areas they eat together, they stay out together, they go out for coffee’. This positive reading of sha’bī is balanced by a darker undercurrent of potential violence. As Nur continues, as a ‘sha’bī place in Lebanon, or in any Arab country, there is a certain level of, you might say [pause] hostility from some of the guys there’.Footnote52

Such hostility towards outsiders seems to be the counterpoint to the strong sense of neighbourliness Nur previously described. Shadi, another single Syrian migrant like Nur, described a long and difficult process of integration within Qobbeh and his attempts to become a trusted member of the community. Although the worst cycle of violence between Bab al-Tabbaneh and Jabal Muhsin began not long after both men arrived in Tripoli, the end of hostilities in 2014 did not significantly improve the situation for Syrians. After six years, Syrians were more tolerated by the Lebanese in Qobbeh than they were accepted; in Nur’s words they were treated with ‘understanding without co-operation’ (tafāhum min dūn ta’āwun). His observation mirrors existing research that co-existence among Lebanese confessional groups is as much about mutual estrangement as it is about cohabitation.Footnote53 For Nur and Shadi, a sha’bī area is one in which Syrians can pragmatically survive in the informal shadows at the price of security and trust.

Other Syrian interviewees drew positive similarities between Bab al-Tabbaneh and their former homes in Syria. Batul, a mother from Homs in her early 40s living with her children, said:

I feel, especially in Tabbaneh, that it’s a lot like the areas where we were living before, it’s sha‘bī. But if you go into the areas outside Tabbaneh, like Abu Samra or Qobbeh, you feel that people are a bit more distant from each other. In Tabbaneh you feel that everyone knows everyone else, people are friends.Footnote54

Batul is heavily involved with the neighbourhood’s aid networks and organizes classes in both traditional Syrian cooking and women’s hygiene for a local NGO. Her experience of Bab al-Tabbaneh’s social life is undoubtedly coloured by this involvement. However, a number of interviewees, particularly women, felt more at ease and comfortable in the Tabbaneh neighbourhood—perhaps a consequence of extended family networks, communal life and a shared history of suffering and loss at the hands of Assad’s forces.Footnote55 As Farah explains, ‘Here in Tabbaneh it’s very sha’bī, but there are a lot of Syrians. Not in Qobbeh, there aren’t. Here it’s families, but in Qobbeh people live by themselves’.Footnote56 For Farah the presence of Syrian families provides a social cohesion and sha’bī atmosphere differentiated from the masculine fragmented neighbourhood of Qobbeh. Despite overcrowded streets, high levels of poverty and unemployment (58.8%Footnote57), poor public services and sporadic violence, Tabbaneh is imagined as a safe space. This may be a coping mechanism, but it also reflects Syrian engagement with Lebanon’s sectarian spatial dynamics. Syrian migrants in Tripoli generally seek to avoid the confrontation zones () around Jabal Muhsin, steering well clear of military checkpoints and avoiding entering the neighbourhood due to the suspicions it would invariably raise among their host Tabbaneh community due to the historic animosity between the two districts.

Figure 2. Map of Tripoli’s contested neighbourhoods (Source: UN-Habitat and UNICEF Lebanon (2018) Tabbaneh neighbourhood profile 2018, Beirut: UN-Habitat Lebanon).

In summary, Syrian imaginary geographies are based on an individual sense of personal safety; sectarian dynamics intersect with gender and socio-economic concerns. In Nab’a, mobility is voluntarily restricted due to fear of political surveillance while in Tripoli Syrians mirror Lebanese spatial dynamics, seeking communal solidarity rather than isolation when opportunity provides it. The next section will examine what happens to Syrians when they are forced to cross boundaries both physical and immaterial.

Crossing boundaries: navigating physical and immaterial barriers

Mobility and transportation

Syrians residing in both Nab’a and Bab al-Tabbaneh rarely leave these neighbourhoods, motivated by a desire to avoid the security infrastructure which monitors their movement. The nature of this infrastructure differs from area to area, with checkpoints in Nab’a more likely to be set up by local political parties and those in Tripoli largely under the purview of the Lebanese military.

The only activity which regularly induces Syrians to leave their neighbourhood and travel to other parts of the city is employment. Most employed Syrian interviewees have jobs in the local neighbourhood where they live, but many, particularly men, have to look further afield. Mustafa, a Kurdish man from the outskirts of Aleppo who lives in Nab’a with his wife and three daughters, regularly travels to Dora, on Beirut’s eastern outskirts, for his job at a metalworker’s shop. Nawal, who has a qualification in Islamic jurisprudence, had been travelling in the evening to Ras al- Nab’a, a journey of around 25 minutes, to teach Qur’anic recitation techniques (tajwid) before she was employed by the local school in Nab’a. Batul gives talks and workshops on women’s health and other topics in various places around Tripoli, organized by a local NGO. However, when the talk is concluded, she always comes straight back to Bab al-Tabbaneh.Footnote58

Journeys outside the city are increasingly rare and taken usually on special occasions to visit family members in other cities. Batul used to leave Bab al-Tabbaneh every Ramadan to see relatives to the north in Akkar; Karima and Khalida, who work together in the kitchens at a volunteer school in Bourj Hammoud, only leave Nab’a on group journeys along the Mediterranean coast or into the Metn mountains with their colleagues. Khalida stopped visiting her brother in Tripoli due to her apprehension of passing through checkpoints along the Beirut-Tripoli highway. Karima is in the same situation with regard to her brother in Byblos, a much shorter journey. The general impression from our research is that Syrian refugees are facing increased restrictions on an already limited scope for travel outside the immediate vicinity of Lebanese cities. Most of the Syrians interviewed in Nab’a reported not having left Beirut at all since their arrival in Lebanon, a period usually exceeding five years.

Security concerns are not the only factor inhibiting Syrian mobility: they are impacted by cost and availability of public transport, and unpredictable interactions with Lebanese commuters. Kristin Monroe argues that transportation and mobility in Beirut (and Lebanon as a whole) is highly stratified and dependent on class. Even before the Syrian War many wealthy Lebanese considered it beneath them to take a shared taxi, for example, arguing that they were for Syrian workers.Footnote59 Cheaper methods of transportation, such as shared taxis, take more time to arrive at their destinations. From this perspective, Monroe explains that urban mobility is a spatial demonstration of power; the limitations that Syrians face in getting around Beirut function as proof of their relative powerlessness. Syrians often travel around the city on foot, despite the distances and time involved and the lack of public footpaths: Mustafa walks to Dora, which takes more than an hour each way. However, this is not the most common method of transport; Mustafa has a bicycle, which he shares with his brother, who lives on the floor above him. In Tripoli, some Syrians have more freedom of movement: Shadi owns a motorcycle, which he uses to travel to areas of North Tripoli to visit his relatives, as well as to get around the city to run errands and to relax.

Shared taxis are the other transport option for journeys around the city. Syrians judge whether or not to use them based on the safety of the situation, and most frequently take them when they are able to travel in groups. The lengths to which Syrians go to avoid individual use of shared taxis may seem extreme. However, during research and site observation, the derogatory language and hostile views expressed by Lebanese drivers towards Syrians, was all too apparent. On one particularly jarring occasion, a driver transporting one of the researchers stopped at an intersection next to a few women begging by the side of the road. Rolling down his window, he shouted, ‘Look at these Syrian whores!’Footnote60 His attitude was by no means unique.

Curfews and military checkpoints

One of the most prominent ways in which Lebanese authorities have attempted to control and police Syrian movement is the deliberate restriction of their mobility through local curfews.Footnote61 Banners announcing a curfew, effectively preventing Syrians from being outdoors for an extensive part of the evening, are a frequent sight in many of Lebanon’s towns and villages. By 2014, 45 Lebanese municipalities had imposed curfews from the Akkar to the Metn Mountains and the South, restricting Syrian movement, and even denying them the right to ride scooters without special permits, punishing breaches with fines, detention or expulsion.Footnote62 Although curfews are less common in major cities, some urban neighbourhoods tried to enforce their own. No formal Syrian curfews were in effect in Nab’a or Bab al-Tabbaneh, although Bourj Hammoud has occasionally implemented them.

For the Syrians interviewed, physical checkpoints rather than social curfews, impose the most significant restrictions on their everyday movements. Syrians in Nab’a, who traverse fewer static roadblocks or armed checkpoints, expressed a heightened sense of fear of being detained, abused or ultimately sent back to Syria. Syrians in Bab al-Tabbaneh, who are surrounded by an oppressive but predictable military presence, have been able to develop everyday routines and do not experience the same level of anxiety concerning checkpoints. These diverging attitudes perhaps reveal more of the urban contexts than they do of Syrian refugee responses, yet they highlight the normalization of a securitized Tripoli.

Tripoli’s history of violence and unrest is etched into its urban topographyFootnote63; the military presence is more visible than in any other large Lebanese city. In central Tripoli, in districts such as the Old City, Sahet Nur, and Sahet al-Tall, there are often small groups or mobile patrols of armed police or soldiers walking the streets. In the suburbs, including Bab al-Tabbaneh, Jabal Muhsin, and Qobbeh, the police presence on the street diminishes, replaced instead by permanent military checkpoints. Trying to enter or leave Qobbeh or Jabal Muhsin requires passing through a checkpoint, and the major roads are lined with concrete barricades. There are also tanks on the street in many strategic intersections (See ). The shift from police to military represents a change in security emphasis from pacification (in the Old City) to containment (in the outer districts); the military is aware that its control over the interior of Bab al-Tabbaneh and Qobbeh is limited, but they are at least able to metaphorically wall them in. Both of Lebanon’s military forces, the Internal Security Forces (ISF) and the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF), patrol eastern Tripoli, but in different areas. The ISF, which is accused of ties to Hariri’s Future Movement and of focusing on the protection of the Sunni population, patrols Bab al-Tabbaneh and Qobbeh. The LAF, which is accused of coordination with the Syrian government and Hizbullah, patrols Jabal Muhsin. Each force also has its own intelligence bureaux, which are themselves connected to different sectarian leaders.Footnote64 Eastern Tripoli has thus become one of the places where the fragmentation of the country’s security forces, and their involvement in regional political conflicts, is felt most keenly.

The military policy of essentially sealing ‘problem’ districts, rather than attempting to resolve underlying issues, causes residents to feel victimized by the security presence. Unlike in Nab’a, where a local political power, Hizbullah, is considered responsible for bringing issues of (in)security into people’s lives, in Tripoli this is done by the LAF and the ISF. The limitations on travel that the Syrians face in Bab al-Tabbaneh are in many ways similar to those faced by the other residents of the neighbourhood. In addition, Bab al-Tabbaneh is one of the most deprived areas of an already marginalized city, where ‘access to the most basic state-provided infrastructure or services is virtually nonexistent’,Footnote65 mirroring in some respects the socioeconomic isolation of Syrians in Lebanon. These shared grievances build on the pre-existing sense of solidarity between the neighbourhood’s Lebanese and Syrian inhabitants.

Nevertheless, the consequences of being apprehended at a checkpoint in Tripoli are often limited. Batul described what happened to her husband when he was arrested: ‘He was due home at about 6 or 7 o’clock, and he didn’t come home until about 11 at night!’Footnote66 A delay of four or five hours, while contributing to a sense of precarity, is far tamer than the consequences interviewees in Nab’a feared. For them, to be apprehended at a checkpoint could be the first step towards being deported back to Syria. It is this frightening and totalitarian power which has driven them to curtail their own movements around Lebanon and Beirut:

If you want to go outside [Beirut] to Chtoura or to Zahle, any checkpoint, it’s very dangerous for people without [papers]. If there’s an incident in the area, if something happens and someone doesn’t have their papers, it’s very dangerous. Even in Nab’a, suddenly they could set up a checkpoint and you’d need to have official papers to get through. If you don’t have anything, that’s it, you’d get arrested by General Security.Footnote67

While most Syrian interviewees in Tripoli have been detained by Lebanese soldiers at checkpoints, they were often released within a few hours. Those in Nab’a told more threatening stories with risker outcomes, including imprisonment and deportation. The more ambivalent attitude towards checkpoints on the part of Syrians living in Tripoli may stem from familiarity with the political and security context which led to their establishment in the first place. Shadi spoke about his experience living in Qobbeh in 2014, at the height of the clashes: ‘I couldn’t leave Tripoli to go to Beirut or to Akkar, because there were checkpoints all over the place. If you got arrested, people who got arrested, they would be held for about a week, and then they’d let them go. So you couldn’t move around, you had to stay within the old city of Tripoli’.Footnote68

Shadi’s description of the security situation in 2014 draws an implicit comparison with the situation four years later, at the time of the research. The checkpoints may be an imposition, Shadi suggests, but Syrians have much more freedom of movement than they used to. This subtext becomes explicit a few minutes later when he explains: ‘the checkpoints are good. It’s very good for security. Just imagine if there were no checkpoints, there wouldn’t be any security! […] There are Syrians making trouble and there are Lebanese making trouble. Neither of them are angels’. Shadi was not the only interviewee who addressed the security situation in a wider context. Nur outlined the history of the checkpoints in Tripoli and the shifting justifications for their continued existence as identity of the local ‘enemy’ changed:

When the Syrian army withdrew [from Lebanon in 2005], the checkpoints they left behind became Lebanese army checkpoints. These checkpoints divide sectarian areas […] so when you come up to the Alawi area, Jabal Muhsin, there are checkpoints at the start of the Jabal and at the end of the Jabal, and it’s Alawi between the checkpoints, just so that nobody goes in, a Sunni perhaps, to inflame sectarian tension. Afterwards, when these sectarian things started happening, the checkpoints were because of the clashes … When the clashes finished and they arrested the militants, the checkpoints were for the Islamists, Jabhat al-Nusra and Daesh, because once upon a time they were widespread in Tabbaneh […] Then when they dealt with the Islamists, they stayed so they could look out for Syrians. Why? So they could take someone away, leave him for a few days, and then bring him back. That’s all they’re there for. They don’t stop anyone, ever!Footnote69

Nur’s detailed political and historical assessment of the Lebanese military’s shifting priorities in Tripoli sharply contrasts the limited and apolitical understanding of Syrians in Nab’a. His personal experience of ineffective and haphazard stop searches differs from the targeted military checkpoints often erected at governorate boundaries, which terrify Nab’a Syrians, particularly those without registration papers. Most significant in Nur’s account is an awareness that Syrians are simply the latest targets for the checkpoints, coupled with Shadi’s characterization of the improved security situation since the army moved into Bab al-Tabbaneh in 2014. Such comments reveal some Syrian support for the city’s security response. It is likely that Syrians, who grew up in a society under the autocratic control of the Ba’th party, prefer the predictability of the physical barriers which exist in Tripoli, which leave little room for negotiation, over the uncertainty and fluidity of the situation in Nab’a. In short, Syrians in Nab’a do not conceive of themselves as joint benefactors of a Lebanese-enforced ‘security’ system, but rather as its victims.

Immaterial boundaries and threat of violence

Finally, there are more unpredictable restrictions placed upon the movement of Syrians, often depending on the area and political timing. In Nab’a, such problems can occur largely at the whim of one of the neighbourhood’s dominant parties, such as Hizbullah. Mustafa, a Kurdish man who lives with his wife and three daughters across the road from the Farḥāt Mosque, recounted:

On the Day of Ashura, I was coming home, I was returning from work. They [Hizbullah] told me to go away and come back again at ten in the evening. I said, ‘I’ve finished work and I’m going home, where should I go?’ They said, 'It’s forbidden to come in here.' And this was going to go on for ten days! Somebody recognized me, he talked to them and told me to go back home. When the children came back from school they searched their backpacks! […] The Shi’a, they’re a bit, they like to make problems for us.Footnote70

Ashura is a major religious holiday among the Shi’a Muslim community, commemorating the death of the prophet Muhammad’s grandson Hussein at the Battle of Karbala in 680. It involves mass marches and public performances retelling the story of Hussein, as well as collective lament and communal practices of self-flagellation (laṭam). The Ashura ceremonies serve as a public reinforcement of the Shi’a community’s togetherness, asserting this identity through use and occupation of urban space.Footnote71 Because of its role in the production of Lebanese Shi’a identity, and due to its own tendency towards securitization and secrecy, Hizbullah considers the Ashura festival to be extremely sensitive. Areas with a large Shi’a population are routinely sealed off from outside visitors each year around the time of the festival. Since the party’s involvement in the Syrian conflict, Hizbullah dominant neighbourhoods, such as al-Dahiyya, have been the target of bombing attacks carried out by Lebanese affiliates of Syrian Sunni Islamist groups.Footnote72 The security measures in Nab’a are not unusual from this perspective and are likely set up explicitly to ward against the entrance of Syrian Sunnis like Mustafa. The circumstances surrounding Ashura create overlapping security frameworks, in which Syrians are regarded as threats both because of their nationality and because they are sectarianized as Sunni actors.

It is the unpredictability of the security landscape around Nab’a, as much as any other aspect of it, which has contributed to the significant lack of safety, Syrians feel in the area. İlcan, Rygiel and Baban have described this constantly shifting security architecture as contributing to ‘precarity of movement’, and although their focus is on the national level, we can see similar effects on an everyday basis.Footnote73 Although Syrians living in Nab’a are unlikely to come into contact with state or party security checkpoints on a daily—or even a weekly—basis, the potential for encountering them disrupted Syrians’ ability to maintain a regular routine. In addition, the presence on the street of members of hostile local parties, who are able to operate outside the rule of law without serious consequences, makes the potential danger difficult to forget. Daily life in these circumstances becomes less ‘normal’ and more like a repeated series of exceptional dangers, where it is impossible to gain control over ‘one’s time, space and future’.Footnote74

Such precarity was also reflected in the fact that more than half of the interviewees related instances of violence perpetrated by Lebanese against Syrians. Some of these were second-hand accounts, but in many cases the interviewees witnessed the incidents personally. The violence ranged from fist fights, knife attacks, throwing stones, military aggression, jostling on the street; some spontaneous and others deliberate, calculated to intimidate and frighten Syrians into submissive retreat and self-policing. Layla’s story was the most brutal:

Not so long ago we were standing on the balcony [in Nab‘a], me and my husband. There was a Lebanese guy who passed a Syrian. The Syrian was on a motorcycle, and the Lebanese guy was in his car, and he [the Syrian] knocked against the car. The Lebanese guy got out of his car and beat the Syrian guy, threw him to the ground, and nobody dared to go near him. There were lots of people around, but because one was Lebanese and the other one was Syrian, he just beat him, he kept beating him, until he died. Nobody even dared to move him. Just because one was Syrian and the other Lebanese, just because he knocked against the car, nothing more! The people around were Syrians, and he was Lebanese, so none of the Syrians would dare to approach him. And he got back in his car and drove away. And nobody came near him to speak to him or anything like that, they just waited until the Lebanese guy left, and then they took the body away.Footnote75

This story of murderFootnote76 is particularly unusual because of who told it. Layla was consistently the only interviewee in Nab’a to demonstrate any level of comfort with her present situation: she accepted that her exile from Syria was permanent, and she said she would prefer to stay in Lebanon rather than take the opportunity to emigrate to a third country. The dissonance between this traumatic scene and Layla’s acceptance of her situation can perhaps be explained as the normalization of violence among Syrian refugees and the bitter realization that Syrian lives remain vulnerable to acts of unaccountable brutality. Another coping mechanism may be the construction of imagined boundaries, as Layla had a strong sense of the division between ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ Nab’a. In her interview she describes a clear distinction between the safety levels for Syrians in the two areas, and she depicted the boundary between them not as a gradual change but an abrupt transition, centred on the street corner on which she lived. From the story the exact position of the attack remains ambiguous, but it is very likely for Layla this is within ‘dangerous inner Nab’a’, symbolically if not geographically distant.

The incident Layla describes illustrates one of the dramatic effects such public violence has on Syrians: their inability to respond to attacks without putting themselves in significant danger. As Layla says, ‘none of the Syrians would dare approach [the attacker]’. The generalized fear of retribution was reported by a number of interviewees, even preventing them from responding to individual daily acts of harassment. Khalida, for example, said that ‘if someone insults you, you wouldn’t dare insult him back’.Footnote77 Nor is this attitude restricted to women. It was echoed in Mustafa’s interview: ‘Every day they insult us. Sometimes we’re just walking in the street, and people insult us, but we don’t hear it. If we responded to it, it would cause a big problem’.Footnote78 These types of violence often paralyze victims, terrifying them into quiescence or into hiding out of the public eye. The spontaneity and unpredictability of such violence further increases Syrian vulnerability. The Lebanese attacker in Layla’s story may not have set out to kill a Syrian; however, after the initial collision nobody in the vicinity was able or willing to stop him from escalating his violent response until the man was dead. Although a terrifying act for Syrians to witness, it was carried out not with the intention of scaring them, but in response to a perceived slight. Such incidents illustrate to Syrians the absence of any protective structure, as no Lebanese authorities (police, military, political parties) intervened to prevent the murder or punish the perpetrator.

Liminal sites, diverging Syrian experiences

Syrian refugee experience in both urban sites runs contrary to popular conceptions of Nab’a’s plural co-existence and Bab al-Tabbaneh’s violent instability. Fewer Syrians interviewees in Bab al-Tabbaneh recounted local episodes of violence or physical threat. This does not mean they experienced Tripoli as a safe city; but rather they were affected indirectly by the structural violence of clashes between Bab al-Tabbaneh and Jabal Muhsin and the securitized climate of military patrols and permanent checkpoints. In Tripoli, fixed boundaries simultaneously restrict and protect Syrians from random acts of violence. In Beirut and Nab’a, Syrians are forced to navigate everyday social boundaries, policing their behaviour and responses, to avoid confrontation or potential retaliation during mundane daily activities. The threat of violence is not just a consequence of refugee precarity but also Syrians may be perceived as potential Islamists, Syrian state agents, historic occupiers, and unwanted guests depleting resources, jobs and humanitarian aid.

Syrian migrants in Tripoli, however, have a longer historic connection and cultural affinity with Lebanese Sunni communities, resulting in less fear over public harassment and acceptance of security responses. As a consequence, Syrian interviewees in Tripoli recognized that their problems were the result of city-wide deprivation and lack of security which requires broader community interventions. Syrians routinely identify that the problems and frustrations they encounter daily are shared by other Tripoli residents and are not unique to them as Syrians. Nur exemplifies this attitude of urban solidarity in his critical description of Tripoli: ‘Here, there’s nothing, here it’s a dead land […] There’s no development, no progress, it’s standing still. Tripoli is standing still’.Footnote79 Syrian migrants in Nab’a, on the other hand, largely saw their problems as the fault of the Lebanese and expressed little interest in finding ways to solve them. These migrants have not found the same communal support or understanding; instead, their presence has intensified local sectarian suspicions and extenuated Syrian fears off run ins with members and supporters of local political parties.

Conclusions

The plight of Syrian refugees in Lebanon remains one of the most critical regional dilemmas, further exacerbated by Lebanon’s ongoing economic demise and political uncertainty.Footnote80 This paper has demonstrated that the Syrian refugee experience is diverse and complex, dependent both on personal status but also significantly impacted by local context and urban power dynamics. In Nab’a, Syrians must negotiate Hizbullah suspicions, in Bab al-Tabbaneh respond to periodic episodes of inter-communal violence, in the Metn conform to local curfews or in the Beqaa navigate between a network of unscrupulous mediators. Despite best attempts to avoid and disengage from Lebanese sectarian networks of power, Syrian everyday presence implicates them within local contests and rivalries. While Syrians are often treated as sectarian actors by local Lebanese communities, they are afforded none of the benefits, services or protection that comes with such affiliations. Syrian refugees have thus learnt to circumvent sectarian spaces rather than confront them, but their spatial practice is impacted just as much by gender, class, refugee status and local prejudices as by sectarian exclusion.

Secondly, the paper confirms that the restrictions placed upon urban Syrian migrants in Lebanon have significantly curtailed their ability to move around Beirut and Tripoli. In both research sites, Syrians seek security by retreating within homes, avoiding public encounters and remaining ensconced in the neighbourhood of initial entry. Such practices of rootedness and invisibility, diminishes prospects of social integration and may lead to the proliferation of exclusive Syrian neighbourhoods and enclaves over time. While the Bab al-Tabbaneh case suggests that Lebanese regions with a long history of Sunni Syrian presence may be better equipped to facilitate communal and cultural integration, this rarely applies to overcoming economic disparities, employment pressures and social welfare provision.Footnote81

Finally, this research affirms that when Syrian refugees move beyond restrictive ‘safe spaces’—both imagined or geographically inscribed—they mostly do so in order to survive (employment, school, shopping, aid collection) rather than out of a sense of defiance or to assert urban rights within the neighbourhood. Military, police, and political party checkpoints continue to represent significant threats to Syrian everyday life, as much for their unpredictability as for the possibility of arrest, harassment and arbitrary return. Within Nab’a, Syrians also take steps to avoid the immaterial demarcations between claims of political control in different parts of the neighbourhood resulting in public withdrawal and confinement. As Lebanon continues to suffer the social and economic ills of endemic corruption and political ineptitude, Syrian refugees will be subject to increased pressure (state and local community) to further retreat from Lebanese public space or eventually return across the border.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Author interview with Syrian refugee in Tripoli, 25 April 2018.

2 According to UNHCR estimates 1 million Syrians are registered and half a million informally reside in Lebanon. Maha Yahya, Jean Kassir, and Khalil El Hariri, ‘Unheard Voices: What Syrian Refugees Need to Return Home’, Carnegie Middle East Centre, 16 April 2018, https://carnegie-mec.org/2018/04/16/policy-framework-for-refugees-in-lebanon-and-jordan-pub-76058

3 Deliberate burning of Syrian settlements in the Akkar and Beqaa. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/12/27/syrian-refugee-camp-in-lebanon-set-ablaze-after-row

4 Tamirace Fakhoury and Derya Özkul, ‘Syrian refugees return from Lebanon’, Forced Migration Review 62 (2019), 27.

5 Sefa Secen, ‘Explaining the Politics of Security: Syrian Refugees in Turkey and Lebanon,’ Journal of Global Security Studies, Vol. 6, Issue 3 (2021); B., Toğral Koca, ‘Syrian refugees in Turkey: From “guests” to “enemies”?’ New Perspectives on Turkey, 54 (2016): 55–75.

6 Estella Carpi, ‘Learning and Earning in Constrained Labour Markets: The Politics of Livelihoods in Lebanon’s Halba’, in Making Lives: Refugee Self-reliance and Humanitarian Action in Cities, ed. J. Fiori and A. Rigon (London: Humanitarian Affairs Team, Save the Children, 2017), 11–36.

7 Sara Fregonese, ‘Beyond the “Weak State”: Hybrid Sovereignties in Beirut’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 30,4 (2012): 655–674

8 Scott Bollens, Scott. City and soul in divided societies. (London: Routledge, 2012), 145–172.

9 UNHCR Lebanon Fact Sheet, August 2021. Available from: https://reporting.unhcr.org/document/474 (accessed 13 December 2021)

10 Khalil El Hariri ‘Analysing the Evolution of Lebanon’s Syrian Refugee Policy: The Role of Foreign Policy’ in Syrian Crisis, Syrian Refugees. Mobility & Politics, ed. Juline. Beaujouan and Amjed. Rasheed (Palgrave Pivot, Cham, 2020), 65–82.

11 Although gender parity was sought the imbalance reflected the demographic realities of a more numerous female Syrian refugee population in Lebanon.

12 There is a growing body of work on Syrian refugees in Lebanon: Lewis Turner, ‘Explaining the (non-) encampment of Syrian refugees: Security, class and labour market in Lebanon and Jordan’, Mediterranean Politics 20, no. 3 (2015): 386–404; Maja Janmyr, ‘Precarity in exile: The legal status of Syrian refugees in Lebanon.’ Refugee Survey Quarterly 35.4 (2016): 58–78; Robert G. Rabil, The Syrian refugee crisis in Lebanon: the double tragedy of refugees and impacted host communities (Lexington Books, 2016); Are John Knudsen, ‘Syria’s refugees in Lebanon: brothers, burden, and bone of contention,’ in Lebanon facing the Arab uprisings, ed. R. Di Pieri and D. Meier (London, Palgrave Pivot, 2017), 135–154.

13 UN-Habitat. (2017). Nabaa Neighbourhood Profile: Bourj Hammoud, Beirut. Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/59497 (accessed 1 July 2021)

14 Joanne Randa Nucho, Everyday sectarianism in urban Lebanon (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016).

15 Craig Larkin and Olivia Midha, ‘The Alawis of Tripoli: identity, violence and urban geopolitics’, in The Alawis of Syria: War, faith and politics in the Levant, ed. Michael Kerr and Craig Larkin (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 181–203.

16 Tine Gade,‘Sunni Islamists in Tripoli and the Asad regime 1966–2014,’ Syria Studies (2015)

17 Henri Lefebvre, Le Droit à la Ville (Paris: Anthropos, 1968).

18 Mohamad Hafeda, Negotiating Conflict in Lebanon: Bordering Practices in a Divided Beirut (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019), 27.

19 The term ‘so-called safe spaces’ was used by one Syrian interviewee, although he confessed, ‘Nowhere is ever really safe these days’, 10 September 2018.

20 Samer Abboud, Syria (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016), 200.

21 John Chalcraft, The Invisible Cage: Syrian Migrant Workers in Lebanon (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), 17–23.

22 John Chalcraft, ‘Labour in the Levant,’ New Left Review 45 (2007): 34.

23 Karim El Mufti, ‘Official response to the Syrian refugee crisis in Lebanon, the disastrous policy of no-policy’, Civil Society Knowledge Centre, Lebanon Support, 1 January 2014 https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/official-response-syrian-refugee-crisis-lebanon-disastrous-policy-no-policy

24 Juline Beaujouan and Amjed Rasheed, ed. Syrian Crisis, Syrian Refugees: Voices from Jordan and Lebanon (Springer Nature, 2019).

25 Nora Stel, Hybrid political order and the politics of uncertainty: Refugee governance in Lebanon (London: Routledge, 2020).

26 Hafeda, Negotiating Conflict, 260.

27 Anya Cardwell, ‘Refugee women and the Right to Inhabit Reconceptualising refugee women’s Right to the City in Bourj Hammoud, Lebanon’, DPU Working Paper No. 197, University College London, 5.

28 Maggie O’Neill & Phil Hubbard, ‘Walking, sensing, belonging: ethnomimesis as performative praxis’, Visual Studies 25:1 (2010): 46–58.

29 Interview, 20 April 2018.

30 Interview, 27 February 2018.

31 Mona Fawaz, ‘Planning and the refugee crisis: Informality as a framework of analysis and reflection’, Planning Theory, 16, No. 1 (2016): 99–115.

32 Interview, 22 February 2018.

33 UN-Habitat Report, Nabaa Profile, 17.

34 Jonathan Darling, ‘Forced migration and the city: Irregularity, informality, and the politics of presence’, Progress in Human Geography 41.2 (2017), 183.

35 Interview, 21 April 2018.

36 Lebanon Support, ‘The conflict context in Tripoli: Chronic neglect, increased poverty, & leadership crisis’, Conflict Analysis Support, 2016, 23, https://civilsociety-centre.org/sites/default/files/resources/ls-carnov2016-tripoli_0.pdf (Accessed 3 October 2020)

37 Interview, 25 April 2018.

38 Interview, 7 September 2018.

39 Emily Lyles et al., ‘Health Service Access and Utilization among Syrian Refugees and Affected Host Communities in Lebanon,’ Journal of Refugee Studies 31, no. 1 (2017): 109

40 UN-Habitat Report, Nabaa Profile, 7.

41 Interview, 8 September 2018.

42 Interview, 6 Sept 2018

43 Interview, 20 February 2018.

44 Asef Bayat, ‘The Quiet Encroachment of the Ordinary’, in Life as Politics, (Stanford University Press, 2020),33–55.

45 Nucho, Everyday sectarianism, 6.

46 Mona Fawaz, Mona Harb, and Ahmad Gharbieh, ‘Living Beirut’s Security Zones: An Investigation of the Modalities and Practice of Urban Security’, City & Society 24, no. 2 (2012), 184.

47 Interview, 22 February 2018.

48 Interview, 23 February 2018.

49 Interview, 2 March 2018.

50 UN-Habitat Report, Nabaa, 14 & 24.

51 Bruno Lefort, ‘Cartographies of encounters: Understanding conflict transformation through a collaborative exploration of youth spaces in Beirut’, Political Geography 76 (2020), 5.

52 Interview, 20 April 2018.

53 Hanna Ziadeh, Sectarianism and Intercommunal Nation-Building in Lebanon (London: Hurst & Co., 2006), 181

54 Interview, 25 April 2018.

55 For more details on the Syrian attack in Bab al-Tabbaneh in the 1980s see Raphaël Lefèvre’s Jihad in the City: Militant Islam and Contentious Politics in Tripoli. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

56 Interview, 25 April 2018.

57 UN-Habitat and UNICEF Lebanon, Tabbaneh Neighbourhood Profile 2018 (Beirut: UN-Habitat Lebanon), 5.

58 Interview, 25 April 2018.

59 Kristin Monroe, ‘Being mobile in Beirut,’ City & Society 23, no. 1 (2011), 99–100.

60 Fieldwork notes, 20 February 2018.

61 El Mufti, ‘Official Response’, 2.

62 https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/10/03/lebanon-least-45-local-curfews-imposed-syrian-refugees (Accessed 1 July 2021)

63 Åre John Knudsen, ‘Patrolling a Proxy War: Citizens, Soldiers and Zuʻama in Syria Street, Tripoli’, in Civil-Military Relations in Lebanon, ed. A.J. Knudsen and T. Gade (Springer, 2017), 71–99.

64 Larkin and Midha, ‘The Alawis of Tripoli’, 193.

65 Lefèvre, ‘The Roots of Crisis’, 7.

66 Interview, 25 April 2018.

67 Interview, 21 March 2018.

68 Interview, 21 April 2018.

69 Interview, 20 April 2018.

70 Interview, 8 March 2018.

71 Lara Deeb,”Living Ashura in Lebanon: Mourning transformed to sacrifice.” Comparative studies of south Asia, Africa and the Middle East 25.1 (2005), 122–137.

72 Bassel Salloukh, ‘The Syrian war: spillover effects on Lebanon,’ Middle East Policy 24, no. 1 (2017).

73 İlcan, Suzan, Kim Rygiel, and Feyzi Baban, ‘The ambiguous architecture of precarity: temporary protection, everyday living and migrant journeys of Syrian refugees,’ International Journal of Migration and Border Studies 4, nos.1–2 (2018), 56–57.

74 Hafeda, Negotiating Conflict, 264.

75 Interview, 23 February 2018.

76 The details of this attack have not been independently verified; however, a Syrian man was stabbed to death in the Bourj Hammoud district on 14 May 2017, as documented by the Civil Society Knowledge Centre’s archive of Conflict Incident Reports (CSKC, ‘Syrian killed in Bourj Hammoud in personal dispute,’ 16 May 2017, civilsociety-centre.org/sir/syrian-killed-burj-hammoud-personal-dispute).

77 Interview, 27 February 2018.

78 Interview, 8 March 2018.

79 Interview, 20 April 2018.

80 Anda David, Mohamed Ali Marouani, Charbel Nahas, and Björn Nilsson. ‘The economics of the Syrian refugee crisis in neighbouring countries: The case of Lebanon.’ Economics of Transition and Institutional Change 28, no. 1 (2020), 89–109.

81 Alexander Betts, Fulya MemiŞoĞlu, Ali Ali, ‘What Difference do Mayors Make? The Role of Municipal Authorities in Turkey and Lebanon’s Response to Syrian Refugees’, Journal of Refugee Studies, 34,1 (2021), 491–519.