ABSTRACT

Does UN peacekeeping reduce the number of people forcibly displaced by violence? While previous research has found that the presence and size of peacekeeping deployments can reduce violence, little is known about how peacekeepers affect other aspects of civilian protection. Using original data on sub-national events of forced displacement and the location and size of UN troop deployments this study systematically evaluates the criticized efforts of UNMISS in South Sudan, while simultaneously testing hypotheses on peacekeepers and forced displacement. It is hypothesized that increasing numbers of troops affect the flight equation among civilians through the promise of and actual deterrence of violence. These deterrence-based hypotheses are also discussed in relation to the South Sudan context, creating scope conditions for their possible application in this case. The statistical analysis provides, however, no robust evidence for peacekeepers reducing the occurrence or levels of forced displacement, and only weak evidence of displaced congregating in larger numbers around peacekeeping locations. The paper ends by arguing that the theoretical argument provided may still be valid, but that an effect was not feasible to identify in South Sudan where the peacekeeping mission – despite its comparatively large numbers – lacks credible deterrent capacity.

Introduction

Can UN peacekeepers reduce the scourge of forced displacement? In 2016 the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre estimates that some 6.9 million new conflict displacements took place, adding to some 40.1 million people already displaced.Footnote1 In specific countries such as Syria and South Sudan, the scale of displacement and the suffering it brings is staggering. In South Sudan the conflict that began in December 2013 has to date produced some 2.5 million refugees and 2.2 million internally displaced: entailing displacement of more than 1/3 of the population.Footnote2

Previous research on the sub-national effects of peacekeeping has demonstrated that the presence and size of armed peacekeepers reduces the number of civilians killed, as well as the number of battle-related deaths.Footnote3 Thus, UN peacekeepers appear to be doing their job in this important sphere of protection of civilians (PoC). Research has, however, focused practically only on this one dimension of PoC, although civilians in civil wars also face heightened levels of disease, starvation, and – not least – forced displacement.

This paper presents what is probably the first study of UN peacekeeping deployments and the occurrence and magnitude of forced displacement on the sub-national level. This is done via a systematic statistical analysis of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan’s (UNMISS) PoC efforts in South Sudan. Theoretically, the study departs from the standard model of displacement as a choice made by weighing costs and benefits of staying, combined with theory on the conflict-mitigating effects of peacekeeping. It is argued that peacekeepers can act both as push and pull factors in affecting displacement, and are effective when they alleviate the push factor of violence through deterring the use of violence. The theory section, additionally, proposes that peacekeepers may also act as a pull factor: peacekeepers may attract those forcibly displaced to areas of higher security and opportunity. These general hypotheses are also scrutinized through the lens of the case of South Sudan. It is argued that this particular case has left little room for UNMISS to create credible deterrence, and that results should be evaluated with this in mind.

Hypotheses are tested using two sub-national data sources: the Geo-PKO,Footnote4 which tracks the sub-national location and size of UN deployments, and an original dataset on events of displacement in South Sudan’s 74 counties between 2011 and 2017. South Sudan is a case with not only interesting variation on the dependent and independent variables, but interesting also because UNMISS has been the target of scathing criticism for its failures in PoC.Footnote5 Little if any research has been systematically conducted on South Sudan in this regard, however, making it difficult to evaluate UNMISS’ efforts in an unbiased manner. The study thus contributes the first systematic analysis of UNMISS and forced displacement.

The results point, however, in favour of UNMISS’ critics, as no robust evidence is found for peacekeeping reducing the occurrence or magnitude of forced displacement. It is shown, additionally, that peacekeepers might act also as pull factors, as those displaced tend to seek shelter in protected sites around peacekeeping bases. The results are discussed within the context of South Sudan, and with a focus on the mechanism of deterrence. The study ends with a discussion on the theoretical scope conditions that need to be in place for PoC efforts to function as theorized.

UN Peacekeeping and the Protection of Civilians

To study peacekeeping’s effects on PoC a new wave of peacekeeping studies has begun to move away from the mission- and country-level analyses of previous studies,Footnote6 disaggregating both dependent and independent variables in time and space. These studies have produced hopeful results. Hultman, Kathman and Shannon identified that increasing the size of UN police and military deployments decreased the number of civilians killed in conflict,Footnote7 Kathman and Wood demonstrated the same effect in the post-conflict period,Footnote8 and Bove and Ruggeri that increasing troop diversity decreased civilian victimization.Footnote9 In the same vein, Fjelde, Hultman and Nilsson demonstrated that local-level increases in peacekeepers reduced the level of rebel-instigated civilian targeting.Footnote10 In sum, the second generation of studies points towards peacekeeping being important for peace and PoC.

Although protecting civilians from harm has always been a core normative issue for peacekeeping, it became a focal point only at the turn of the century, after which most missions included a focus on PoC.Footnote11 The bulk of cross-case research on PoC has, however, focused on only one specific dependent variable: direct deaths. While an important topic there are other forms of victimization, safeguarding against which also translates into PoC: for instance sexual violence and abuse, food security, and this paper’s focus of forced displacement. Although forced displacement has been studied for years,Footnote12 practically no studies have analysed if and how it is affected by peacekeeping. One exception is a working paper by Costalli and Ruggeri.Footnote13 They demonstrate, tentatively, that the presence and size of peacekeeping has a positive effect on the return of refugees, but that size and presence has no effect on the creation of displaced. Ruggeri and Costalli’s country-level analysis has one significant limitation though: the aggregated level of analysis does not allow us to study if UN troops decrease refugee outflows from the locations where they are present vis-à-vis where they are not. Seeing as we know that UN peacekeeping mainly decreases levels of organized violence in the sub-national locations where they are present, a country-level analysis might not give us the full picture. This study addresses this gap, through analysing the effects of the location and size of peacekeeping on forced displacement.

Why and When Do People Flee?

Research on forced displacement – encompassing both IDPs and international refugees – has established that, even under challenging circumstances, individuals make choices of whether or not to flee.Footnote14 The most prominent model is ‘choice-centered’ and calculates, from the rational choice perspective of utility maximization, what push and pull factors weigh into individuals’ choices to flee.Footnote15 Push factors are those phenomena from which individuals want to escape, such as violence or difficulties in procuring food. Pull factors are those that promise individuals better utility in a different location: what are the levels of security available elsewhere? When push and pull factors combine to outweigh the utility available in a location of origin, people make the choice to flee towards locations deemed more fruitful and/or accessible. Consequently, much previous research has focused on what factors make displacement more or less likely and what factors increase or decrease the magnitude of flight?

Violence has been identified as the primary push factor. Logically, people often choose to flee when they deem their lives to be at risk. Davenport and colleagues found, at the country-level, that violence and threats of violence were major determinants of refugee flows.Footnote16 Melander and Öberg demonstrated that both the intensity of ongoing violence and its geographical spread were associated with forced displacement, as more individuals risk violence.Footnote17 Adhikari, in his studies of Nepal, also concluded that the anticipation of and acts of violence are the core reasons for forced displacement. In short, the literature agrees on the primacy of violence and the threat of violence as determinants of flight,Footnote18 while factors such as infrastructural and economic opportunities are secondary considerations.

Peacekeepers and the Flight Equation

How may the presence and size of UN peacekeeping contingents feed into these decisions? The above discussion on the factors found to influence flight provides a set of ways in which peacekeepers may affect push and pull factors.

First, peacekeeping presence and size may serve to decrease the two push factors of actual violence and the perceived threat of violence. After all, PoC mandates dictate that peacekeepers should protect civilians from harm. Previous studies have also shown this to be the case to some extent: when the size of a peacekeeping contingent increases, levels of civilian victimization and violence between warring parties decrease.Footnote19 Previous research consequently points towards peacekeepers abating levels of violence, and thus possibly diminishing the threat and actual exposure to violence. Seeing how previous research identifies violence or the anticipation of it as the primary factor in the flight equation, peacekeeping may decrease forced displacement.

At least two possible pathways are available for how this violence-mitigating effect may factor into decision-making. First, a substantial peacekeeping presence may reduce actual levels of violence in a locale, and subsequently mitigate this push factor. The less violence is present in an area, the less an individual should deem her/himself to be at risk. As the size of a peacekeeping contingent increases and diminishes levels of violence further, this should have additional effects on the approximated utility of staying. Second, not only the presence of violence, but the anticipation of it may be modified by peacekeeping presence. Individuals in conflicts where peacekeepers are present expect that their presence is at least some form of safeguard against abuse. Thus, as a UN presence grows, people’s anticipation of violence should decrease; again affecting this push factor negatively. The logic in this second pathway differs from that in the first in at least one important way. While violence is actually decreased in the first, this need not be so in the second. In this pathway, it is the anticipation of protection that affects the flight equation.

The chief theoretical mechanism relied on by previous research to explain the violence-mitigating effects of peacekeeping is that of deterrence.Footnote20 While the exact argument differs across studies, the general claims include that peacekeepers mitigate violence through establishing effective control of areas, patrolling these and showing presence, interceding and interpositioning themselves between parties: thus deterring the use of force through raising the costs of aggression. Lindberg Bromley identifies two poles on a continuum of the mechanism: deterrence in the form of displaying presence and mobility and thus signalling the possible cost of engaging in violence, and enforcement in the form of offensive action to punish transgressions.Footnote21 Often, the deterrent capacity of a peacekeeping mission is equated with its national and/or sub-national presence and size: larger size entails higher deterrent capacity.Footnote22 At the other end of the continuum lies enforcement: more offensive actions taken by peacekeepers to protect civilians, including interpositioning, forced disarmament, and offensive posturing. Also at this end of the spectrum, presence and size are thought to be indicative of deterrent capabilities.Footnote23 Put simply, increasing deterrent capacity translates into less violence.

Peacekeeping may serve to decrease forced displacement also through other mechanisms. One possibility is that the interpositioning of peacekeepers between warring parties decreases displacement as the geographical spread of violence is hindered. For example, levels of violence may remain at similar levels as before the intervention in some localities, but is hindered from spreading to new locations. This situation would, however, be dependent on the size of the force being large enough to deter warring actors from movement towards UN locations. The size of UN forces should thus matter also if this mechanism is at play. From the above two hypotheses are derived:

H1: All else equal, as the number of peacekeepers in an area increases, the probability of events of mass displacement decreases.

H2: All else equal, as the number of peacekeepers in an area increases, the number of forcibly displaced decreases.

At least two implications are necessary to approach in more detail. First, when people are forcibly displaced they should be more likely to flee towards peacekeeping areas, rather than locations without peacekeepers. This can take the form of either intra-area movement towards a peacekeeping location, or as extra-area flight towards a peacekeeping location. Second, increases in this pull factor may also entail that the individual’s propensity to flee is increased if he or she is proximate but not under the direct protection of peacekeepers. In formal terms, if push factors across locale A and B are equal while the pull factor is higher in locale B (closer to a peacekeeping base), individuals may be more inclined to flee from B than from A. It is thus possible that peacekeeping deployments also increase the propensity to flee.

With the data available the latter implication cannot be tested in any convincing manner, but the reader should note that these processes can coexist with displacement-mitigating effects. The first implication – that faced with violence the displaced move towards peacekeeping areas – can, however, be tested, and forms the basis of hypothesis 3 below:

H3: All else equal, areas with higher numbers of peacekeepers will be more likely to be net-receivers of displaced people.

The Limited Deterrence of UNMISS(?)

All three hypotheses rely on the presence of the mechanism of deterrence: that the warring parties will shy away from violence when aggression appears too costly. Interestingly, much of the critique that has been levelled against UNMISS in terms of PoC failures can in large parts be related to a lack of deterrent capacity.

UNMISS was established when South Sudan became independent from Sudan on 9 July 2011. UNMISS’ original Chapter VII mandate tasked the operation with a wide range of missions, including supporting the new government in peace consolidation, assisting in PoC, and helping establish state influence. Initial mandated troop levels stood at 7000 troops and some 900 UN police.Footnote26 Both mandate and troop levels were to change with the December 2013 government crisis, when the President, Salva Kiir, accused his Vice President Riek Machar of attempting a coup and fighting broke out between their loyalists. The ruling SPLM/A split along ethnic lines, with Machar’s faction becoming known as the SPLM/A – In Opposition. From its initial concentration to South Sudan’s major urban areas the civil war expanded to encompass almost the entirety of the country and many other ethnic communities. The expansion of the civil war led to both a strengthened PoC mandate and increases in troop sizes, with the latest figures standing at 17,000 troops, including 4000 for the Regional Protection Force (RPF).Footnote27

Despite this comparatively large troop size and a strong mandate UNMISS’ PoC efforts have been harshly criticized. Several reports highlight many events where inaction by UNMISS has led to disasters in the form of killings, sexual violence and displacement.Footnote28 Reviewing these reports it appears that UNMISS has not succeeded in posing as a credible deterrent, since (1) UNMISS has not engaged in practically any offensive action or conducted operations to punish transgressors, nor (2) has it acted with force when strategic locations have been threatened or attacked.

Turning first to the offensive spectrum, one reason for this failure appears to be that UNMISS’ freedom of action is restrained by the necessity of government consent for deployment: undercutting possibilities to act against the many transgressions of the government itself.Footnote29 Little seems to have changed with the deployment of the Regional Protection Force (in 2016), which mandated UNMISS to protect civilians using ‘all means necessary’ and ‘engage any actor’ threatening civilians.Footnote30 Additionally, UNMISS’ freedom of movement has been restricted by several actors, and the mission has not used force to assert its rights in this sphere. As demonstrated by Duursma in a study on obstruction of peacekeepers in Darfur, such actions can be used by warring parties to undermine protection efforts and open up for civilian targeting.Footnote31 Deterrence through punishment has thus barely existed since the inception of UNMISS, nor have come into place later.

Secondly, there is ample evidence that the warring parties have no qualms about attacking locations where UNMISS is present. Consider the town of Malakal where the UN’s own reports note the town changing hands a full 12 times: this despite some 1000–2500 troops present.Footnote32 Similar disregard of UNMISS’ presence can be noted in the repeated battles for Wau and Bor. In all these instances UNMISS failed to intervene or interposition themselves, and their mere presence seems to have done little to deter attacks. There are also ample reports that militias and other armed actors act with impunity in committing atrocities right on the perimeter and in the vicinity of UNMISS bases.Footnote33

Consequently, the case of South Sudan can be seen as a hard test for the deterrence-reliant hypotheses; or alternatively as a least-likely case. It is important to keep in mind, however, that the reports referenced above have not been conducted systematically and can thus not paint a full picture of failures and successes. The majority of incidents reported on concern locales where UNMISS is present; leaving us to speculate on the scale of violence and displacement in areas where peacekeepers are not present. In addition to hypothesis-testing a further contribution made in this study is, thus, conducting the first systematic evaluation of UNMISS’ effects on forced displacement in South Sudan.

Materials and Methods

The hypotheses are evaluated by analysing spatially and temporally disaggregated data on UN peacekeeping and forced displacement in South Sudan between 2011 and 2017. The time period studied is bounded by the creation of South Sudan in July 2011, and the last year for which there is data on all variables (2017). The unit of analysis is the county-month, with corresponding data for the presence and size of UN peacekeeping and the number of forcibly displaced. The original data structure contains 6164 county-months.

Dependent Variables

Dependent variables were constructed from an original dataset on forced displacement in South Sudan 2011–2017. The author identified all situation reports, bulletins, and humanitarian updates on South Sudan from OCHA (Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs), IRNA (Integrated Rapid Needs Assessment), Humanitarian Response, and all Protection Situation, Camp Coordination and Camp Management Cluster, Operational, and Situation updates, reports, and fact sheets, from UNHCR (via Reliefweb).

From these reports events of displacement were manually coded within and from South Sudan’s 74 counties. Each event is a reported incident of mass displacement, with ‘mass’ signifying that it was large enough to be noticed and recorded by humanitarian organizations. Each event contains the month of the exodus, its geographic origin (at the county-level), the approximated number of individuals displaced, and the known point/s of arrival of the displaced. Events were then aggregated to the county-month level, providing a month-by-month estimate of both where the forcibly displaced escaped from and where they went. Note that forced displacement does not necessarily mean that individuals leave their county of origin. A substantial proportion of events entail fleeing to neighbouring areas within the same county. Approximately 600 events of mass displacement were coded between 2011 and 2017 period, totalling some 4.2 million IDPs and refugees. A more in-depth description of the coding practice and its challenges are given in the Online Appendix, Section A.

Using these data I constructed the three main dependent variables: displaced_exit, displaced_exit_dummy, and netreceiver. Displaced_exit is a count variable of the number of displaced people in a specific county-month (irrespective of whether they were displaced away from or within their county of origin). This variable is used to evaluate H2 on the number of people forcibly displaced. Displaced_exit_dummy is a dichotomized variety, capturing county-month events of mass displacement. This variable records if a county-month experienced one or more events of mass displacement or not, and is used to evaluate H1. Finally, netreceiver is a dichotomous county-month variable which captures if a county was a net-receiver or net-giver of displaced. This variable is constructed by, per county-month, subtracting the number of people displaced from a county from the number of people seeking refuge in the same county, and then dichotomizing it (with a score of 1 entailing that a county-month is a net-receiver). This variable thus captures the two different processes of (1) people being displaced but remaining in their county, and (2) if displaced people move towards other counties after being displaced. The variable should thus consider both of the two routes suggested in the theory section of either remaining close to a peacekeeping location or moving towards such a location. For H3 to be supported, larger numbers of peacekeepers should correlate with a county being a net-receiver (all else equal). Descriptive statistics are available in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Independent Variables

To create the independent variables I extend and make use of the Geocoded Peacekeeping Operations Dataset (GEO-PKO),Footnote34 which codes the sub-national location and size of all UN peacekeeping missions in Sub-Saharan Africa 1994–2014. I expanded the dataset to include South Sudan 2015–2017, following available coding rules. I make use of the month as the temporal level of analysis, and match the geographical locations and deployment-month to the county-month data structure.

For robustness purposes, I construct several independent variables. First, notroops1 measures the size of the peacekeeping contingent in each county-month. Data comes in the form of the number of deployed platoons, companies, and battalions, following NATO and UN standards of 35 peacekeepers in a platoon, 150 in a company, and 650 in a battalion. The variable is rescaled to correspond to increases on the platoon basis, and is the main independent variable. Notroops2 takes heed to peacekeeping’s magnitude of responsibility in each county by dividing the troop number with a county’s population level, creating a ‘peacekeepers per capita’ score. Lastly, notroops3 takes heed to the landmass that peacekeepers have to cover, dividing county size by the number of troops. The size of a county relative to the number of peacekeepers affects the mission’s possibilities for patrolling territory and reacting to events. Descriptive statistics are available in .

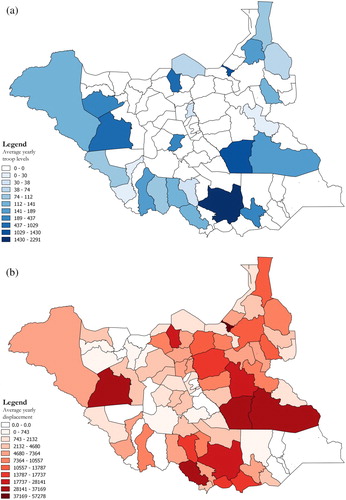

displays the spatial variation in the raw scores of independent and dependent variables. Panel (a) shows, per county, the average number of peacekeepers per year over the 2011–2017 period, while Panel (b) shows yearly averages of forced displacement.

Matching Approach

Using a naïve observational design comes with the problem of the non-random nature of where peacekeepers deploy.Footnote35 The main analytical problem in such a design is that peacekeepers are likely to deploy to certain ‘hot spots’: locations that attract peacekeepers while simultaneously having a higher likelihood of experiencing forced displacement. If the design does not account for this, results will yield incorrect inference, for instance, showing that peacekeeping increases levels of displacement (visible as a potential issue in ). This analytical problem occurs both for the analysis of from where the displaced leave (H1 and H2), as well as for where they go (H3). To account for this selection I make use of nearest neighbour and exact matching, distinguishing between county-months with peacekeeping deployment (treated cases) and counties without peacekeeping deployment (control cases). ‘Peacekeeping deployment’ (deployed) entails that the UN had established a base in an area with at least one platoon.

Matching and Control Variables

I begin by identifying a set of variables to be used for matching and control purposes. First, I include a measurement of previous violence, as studies demonstrate that peacekeepers are more likely to deploy to ‘hot spots’: areas that are more likely than others to see both deployment and renewed violence.Footnote36 To account for this I construct a measurement capturing fatalities from organized violence (fiveyear_violence) in a county in the five years before the observation period (i.e. five years before the start of the dataset in summer of 2011). This variable is coded using events of organized violence from the UCDP GED.Footnote37 In the main models, I do not match on more recent violence as this would induce post-treatment bias.Footnote38

Second, infrastructure and terrain (in the form of the magnitude of physical obstacles or opportunities) have been identified by previous research as factors that affect the choice to flee, as well as the feasibility of deployment and armed clashes.Footnote39 Transportation infrastructure is measured by each county’s road density (road_density), calculated by dividing the length of motorable roads in each county with its size using data from OCHA (https://data.humdata.org/dataset/south-sudan-roads). I additionally match on levels of forestation (frst2000), and county size (c_size2). Forestation measures the proportion of a county covered in dense forests.Footnote40 County size was calculated by the author using QGIS and PostGIS.

Third, I match on distance to international border (bdist) and distance to capital (cap_dist). As argued by Ruggeri, Dorussen, and Gizeliz distances to the capital and to international borders affect the ‘feasibility and cost of deploying’, while peripheral areas may attract more fighting, and thus more displacement.Footnote41 Both these variables were calculated in QGIS and PostGIS.

Fourth, I match on population (lpop) and average GDP per capita (gcppc05) in each county. Population is argued to correlate with the occurrence of organized violence and the deployment of peacekeepers,Footnote42 and GDP per capita may attract more violence, as well as a higher feasibility of peacekeeping deployment. The natural log of population is used, with data from South Sudan National Bureau of Statistics,Footnote43 while data on GDP per capita is from De Juan and Pierskalla.Footnote44

Finally, I include two controls in the form of spatial lags (not used for matching). Troopspatlag is a spatial lag of troop deployments, capturing per county-month the number of troops in neighbouring counties, as these may affect both push and pull factors. Similarly, to account for other nearby spatial push and pull factors I include a spatial lag of nearby fighting (bestlagdummy). This variable captures, per county-month, the number of neighbouring counties experiencing violent events (based on the UCDP GED) with at least one fatality.

Correlation Analysis

As the objective with matching is to balance covariates that influence the probability of the occurrence of both dependent and independent variables I first correlate these variables with the matching variables. Separate correlation analyses were conducted for the three dependent variables, as the processes of displacement production may differ. Variables identified to have an influence on both dependent and independent variables (signified by significance stars) are used in the matching process. Standardized variables were used for ease of interpretation.

Matching Procedures

Having identified confounders (see ), I apply these variables in two separate matching procedures: nearest neighbour and exact matching. Nearest neighbour matching (Mahanalobis distances) provides a more ‘generous’ matched dataset, matching all treated cases (county-months with peacekeepers) with the most similar untreated cases (county-months without peacekeepers). The exact matching model provides a more trimmed dataset of matches within the exact same coarsening strata. This process is repeated for all three dependent variables, creating separate datasets.

Table 2. Matching variable correlations.

Results of the matching were not perfect (see ). The original naïve dataset is highly unbalanced, with multivariate distance scores (L1) of 0.93, 0.61, and 0.86 for the three dependent variables. The naïve dataset is thus not particularly suitable for hypothesis-testing, as units with and without peacekeeping deployments are very different. The nearest neighbour matching shows good improvement for the count data on displacement, decreasing L1 to 0.52, but only slightly decreasing it in the other two datasets (from 0.93 to 0.88, and 0.86 to 0.76). Finally, the exact matching approach reduces the multivariate L1 distances substantially and represent – across variable means – the best matching solutions. All matching solutions, however, have remaining imbalances, meaning that results should be interpreted carefully.Footnote45 For transparency purposes, I make use of all three varieties of the data in the analyses. A detailed table of matching results is available in the Online Appendix (Table B1).

Table 3. Matching scores for dependent variables.

Statistical Considerations

The three dependent variables call for different statistical approaches. To evaluate hypotheses 1 and 3 binomial logistic regressions are applied, with robust standard errors clustered on county. For hypothesis 2 the dependent variable is over-dispersed with a long right-leaning tail and an abundance of zeros. Pre-analysis testing indicated that the dispersion was not Poisson, and both Vuong tests and BIC and AIC comparison preferred zero-inflated negative binomial models for the naïve and nearest neighbour datasets.Footnote46 The exact matching dataset lacks an abundance of zeros and prefers negative binomial models, with robust standard errors clustered on county.

In all models, I avoid controlling for covariates that may induce post-treatment bias, for instance, the levels of ongoing conflict in a locality. As peacekeepers set out to minimize casualties and to some extent redeploy to do so, including this variable may bias estimated effects.Footnote47 Put differently, I avoid covariates that are in themselves dependent in the post-treatment stage on the score of the independent variable.

Results

Hypothesis 1

I begin the analysis by evaluating hypothesis 1: that increasing deployment size decreases the probability of the occurrence of mass displacement events. Models 1–3 are bivariate models, each using one of the three datasets: the naïve original data, the nearest neighbour matching, and the exact matching. In Models 4–6 control variables corresponding to those used in the matching are introduced, and finally, in Models 7–9 additional control variables. displays results for these models.

Table 4. DV: Dummy variable of displacement events.

Results in refute H1, however, as there are no negative and statistically significant coefficients (which would indicate a decreased probability of mass displacement). In Models 1–3 the coefficient on troop size is positive and significant for the naïve and nearest neighbour datasets, and negative but insignificant for the exact matching. The positive coefficients in Models 1 and 2 imply a positive correlation between the probability of mass displacement and troop deployment. This association is, however, most likely an artefact of the unbalanced data (L1 = 0.93 in the naïve dataset and 0.88 in the nearest neighbour). As the imbalance decreases in the exact matching data, the coefficient becomes negative (albeit not significant). Bivariate correlations do not, however, support H1.

In Models 4–6 matching variables are introduced, to exploit the last available variation.Footnote48 Results do not change when controlling for these additional variables. Support for H1 is, however, not forthcoming in the full models with additional controls either (Models 7–9). In these models, the troop coefficient is positive and significant in the naïve and nearest neighbour data, while negative but insignificant in the exact matching. Consequently, the main models demonstrate no support for H1. One should keep in mind, again, that the naïve and nearest neighbour datasets are relatively unbalanced.

Hypothesis 2

I now turn to H2: that increases in troop levels will be associated with decreases in the count of displaced people. As discussed in the section on statistical considerations, the different datasets prefer different count models: these are noted at the top of .

Table 5. DV: Count of displacement.

Results in are similar to what was found for H1, in that the coefficients on the troop size variable are positive in the naïve and nearest neighbour datasets, and negative in the exact matching data. Of more direct interest for evaluating H2, no coefficients have statistically significant negative effects. That is, there is no evidence that increases in troop size in a location is related to lower levels of displacement, speaking against H2.

Models 10–12 show the bivariate relationships across the three datasets. Here, coefficients are positive and significant for the two first datasets, but negative (not significant) in the exact matching data. Again, however, these positive associations are more likely caused by imbalances in the data, rather than an actual association in which peacekeepers cause more displacement. There are also no significant negative effects of troop size in the models that introduce the matching variables (Models 13–15), nor in the full models (Models 16–18). Coefficients in the exact data models are consistently negative, but not significant. Across models, positive and significant coefficients on the main independent variables are more common, although many models produce no significant effect in any direction. Results in thus refute H2, as increasing troop size is not associated with lower counts of displaced.

Hypothesis 3

Finally, I evaluate H3: that counties with comparatively higher numbers of peacekeepers will be more likely to be net-receivers of displaced people. The dependent variable is a dummy of whether or not a county-month is a net-giver (0) or net-receiver (1) of displaced.

Results are presented in and provide only some support for H3. Across the full set of models (19–27) there are several positive and significant coefficients, denoting that as troop size increases so does the probability that a county-month will be a net-receiver of displaced.

Table 6. DV: Dummy of net-receivers.

The first three models (Models 19–21) show bivariate relationships, where the troop size coefficient is positive and significant in the naïve and nearest neighbour datasets, while the coefficient is negative but not significant in the exact matching data. In interpreting this output one should again keep in mind the imbalances in the different datasets: L1 scores of 0.86 and 0.76. The bivariate patterns are stable across all models with controls (Models 22–27), thus demonstrating at least some support for H3.

Consequently, the analysis of H3 yielded some, but not clear-cut, evidence in favour of the proposition that larger troop contingents attract displaced people to a higher degree. Although a majority of the coefficients spoke in favour of the hypothesis the evidentiary value is lowered as these relationships were identified only in relatively unbalanced datasets. Support for the hypothesis should thus be classified as tentative.

Robustness Analyses

To check for model and variable dependency I conducted several robustness analyses. First, I reran the regression models using notroops2 and notroops3, denoting a ‘peacekeepers per capita’ score and a ‘peacekeepers per square kilometer’ score. These variables can be construed as capturing different aspects of the density of peacekeepers in a sub-national locality, which may matter for efficiency.

Results using these variables are, however, for all purposes the same as in the main models (Tables B2–B7, Online Appendix). Throughout models with both notroops2 and notroops3 as the main explanatory variables coefficients in the naïve and nearest neighbour datasets tend to be positive and significant, and coefficients in the exact dataset are negative but insignificant. Thus, across these models, there is no support for H1 or H2, while the tentative support for H3 remains.

In additional analyses, other varieties of the dependent variable were also studied. In two sets of models the count variable of displacement (used in H2) was transplanted with its natural log, and in the second set with a transformation to the proportion of a county’s population displaced. The coefficient on troop size remains positive and significant using the naïve and nearest neighbour datasets, and negative but not significant in the exact matching data (B8–B9, Online Appendix).

In tests on different cuts of the data, I subsetted the data to take as the unit of analysis only county-months with a peacekeeping deployment, leveraging within-unit variation to reduce non-random deployment bias. I reran models for all three hypotheses (B10–B12, Online Appendix), but with no implications for H1 and H2. These models, however, spoke against H3, as all positive coefficients were insignificant. Additionally, I eliminated potential outliers in the datasets: observations with deviant displacement scores. I then reran the main and subsetted models with results remaining virtually unchanged. I additionally reran the main models (with full controls) while ignoring the post-treatment bias issue: thus including a measurement of ongoing violence in each county-month. Although post-treatment bias is a serious issue, levels of violence are important push factors that might require modelling. In these models (B13–15) levels of violence (best) are (as expected) strong push factors for displacement, but the main findings do not change. Finally, I reran the main models but with a fixed-effects specification (clustering on county) and using controls with temporal variation: this did not produce evidence in favour of any of the hypotheses. Consequently, alternative specifications do little to change the main conclusions.

Discussion and Conclusion

The statistical analysis failed to demonstrate support for H1 or H2, and provided only weak evidence in favour of H3. Increasing troop levels were not associated with declines in the frequency of mass displacement or the number of displaced, and only in the unbalanced datasets did increasing troop size attract more displaced. A few models – mainly the ones using the naïve and nearest neighbour datasets – found positive correlations, implying that peacekeepers increase the number of displaced. Seeing, however, to results in the more balanced datasets, the soundest conclusion is that troop size is not directly associated with forced displacement in this sample. Although some evidence was found in support of H3 – implying that peacekeepers act as a pull factor for displaced people – issues with data balance are relevant here too.

Of major interest is what can account for this lack of an association? Below I discuss potential explanations and what they may entail for the case of South Sudan and UNMISS, as well as peacekeeping theory.

Turning first to data issues, the lack of balance in the data diminishes possibilities of unbiased estimation. The maximal reductions in L1 distances were only to 0.53, 0.38, and 0.52, and even the best matching solutions could balance data only at the means, and not consolidate distributions. Thus, units that were similar on all aspects but the independent variable were difficult to identify, and effects thus difficult to evaluate. A strong claim that peacekeeping does not reduce levels of forced displacement is hardly feasible.

Second, the possibility should be considered that even if peacekeepers do lower levels of displacement-inducing violence, these reductions may not be enough to mitigate displacement. Two recent studies conducted on the violence-mitigation of peacekeeping underline points in this regard. Ruggeri, Dorussen and Gizelis find that although local deployments shorten conflict episodes, there is little evidence that peacekeepers stop local conflict from occurring.Footnote49 Fjelde, Hultman and Nilsson identify that local deployments do well in reducing rebel violence against civilians, but does not have the same effect on government-initiated killings.Footnote50 Seeing as civilians in South Sudan need to escape violence both by government and rebel actors, and as they are unlikely to factor in – to any high degree – the duration of fighting, it is worth considering that a minor reduction in violence does not alter civilian calculations enough to reduce displacement. Future research should attempt to investigate cut-off points, or if a complete reduction of violence is necessary to make people stay put.

Third, recall from theory that the underlying premise of peacekeeping’s ability to mitigate forced displacement was credible deterrence. In outlining the case of South Sudan I argued that UNMISS has almost completely lacked such a capability. This first systematic analysis of peacekeeping and forced displacement supports this assertion. UN peacekeeping may fare better in mitigating forced displacement in cases where more deterrent capacity is present. Such research should be undertaken before any broader claims are made regarding the relationship between peacekeeping and forced displacement.

The above should not be taken, however, as UNMISS not having protected civilians. Hundreds of thousands have sought and found relative refuge in PoC sites.Footnote51 The evidence identified in favour of H3, in that county-months with more troops had higher probabilities of being net-receivers of displaced, is thus not unsurprising. Tentative evidence thus suggests that larger UN contingents act as pull factors in individuals’ calculations of where to go once uprooted. Although this may be viewed as a perverse side-effect that can increase rates of displacement, one should consider that compared to impromptu IDP camps, PoC sites offer better opportunities for survival. Even the reports and analyses that criticize UNMISS’ failures highlight that many thousands of lives have been saved via this ad hoc solution.Footnote52 Support for H3 was, however, not clear-cut, and further research is necessary to better understand the strength and drivers of this possible effect.

Finally, it should be considered what these findings imply for our theories of peacekeeping, deterrence, and PoC. First of all, the case of UNMISS calls into question equating mission size with deterrent capacity: UNMISS had the highest number of military peacekeepers of all missions in 2018 yet displays little deterrent capacity. Although more recent studies have identified that troop quality and mission diversity also matter for mitigating violence,Footnote53 theory and measurement are still focused on troop size as a proxy for deterrence. Of importance for the disaggregated approach, this lack of equivalence between size and deterrence seems to exist also at the local level, as even the stationing of thousands of troops in some areas did not stop the warring parties from seizing strategic locations. These results run counter to what has been found in the latest studies on peacekeeping and civilian victimization, where local increases in troop size served to lower levels of violence via deterrence.Footnote54 This study suggests that this correlation is conditional or context-sensitive. Mandate strength does not appear to be such a condition, as UNMISS came armed with and received a reinforced PoC mandate with wide-ranging possibilities for the use of force.

Costalli, in his study of Bosnia also notes a UN PoC failure, and suggests that the main deterrence-decreasing factors were the ‘highly motivated internal actors’, and the ‘necessity’ to stay neutral.Footnote55 Similar factors have been identified as hindering effective PoC also in cases such as Cyprus and East Timor. In both these latter cases, the UN faced parties that were strongly motivated to push their agendas of civilian displacement. In Cyprus the UN failed to use capabilities that were at hand – partly in order to remain neutral – while a lack of capabilities in East Timor made it impossible to stop marauding pro-Indonesian militias even if willingness had been present.Footnote56 These are relevant factors to consider also for UNMISS, and more broadly theoretically. Deterrence and its credibility are relational concepts, where not only the strength of peacekeepers weighs in, but also the strength and motivation of the warring actors, and the commitment and willingness of the peacekeepers. To exemplify Costalli’s factors in regard to UNMISS, the warring actors proved early on in the conflict that they were indeed ‘highly motivated’ to commit brutal atrocities, at the same time as UNMISS’ felt constrained due to necessary government consent, and as their movements were obstructed without response.Footnote57 In places such as Malakal and Bor UNMISS had enough troops for a show of force, but the aforementioned factors decreased their willingness and/or opportunities to do so: leading to failed deterrence. When levelling such critique it is relevant, however, to consider Posen’s theorizing regarding the difficulties inherent in the military options available to halt displacement disasters.Footnote58 Posen notes that those trying to stave off displacement-inducing violence often find themselves unable to deter an attacker, and instead rely on compelling the attacker to change behaviour: something that is difficult due to the attacker often being stronger than the intervener in terms of force capabilities, coherence, and willingness. As became the case in South Sudan, Posen notes that the creation of ‘safe havens’ (PoC sites in this context) is often the most expedient solution to the urgent needs created by mass displacement in contexts where capacity and capability are lacking.

Seeing to the above, this study echoes Haas and Ansorg’s call for better measurements of mission capacity/capability,Footnote59 as well as more research to better understand the conditions – local and mission-wise – that affect the application of credible deterrence. It seems imperative to gain a much deeper understanding of the local-level mechanisms that facilitate or hinder PoC.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful for feedback from the Ending Atrocities working group, especially Lisa Hultman, Corinne Bara, Sara Lindberg Bromley, and Sabine Otto. Other feedback was given at the Ending Atrocities workshop, Uppsala (2018): special thanks to Jacob Kathman and Andrea Ruggeri. The author is also grateful for comments from Annekatrin Deglow, Johan Brosché and Chiara Ruffa.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data Availability Statement

The online appendix is available at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7484804.

Notes on Contributor

Ralph Sundberg (born 1981) is a lecturer and researcher at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University. His current research focus is on peacekeeping, where he has studied both the effects of peacekeeping, as well as the effects on peacekeepers of conducting interventions. His work has been published in journals such as Journal of Peace Research, Military Psychology, and Journal of Personality.

ORCID

Ralph Sundberg http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1167-2799

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 IDMC, “Global Report.”

2 Reliefweb, “South Sudan Situation”; and UNHCR, “UNHCR-South Sudan Emergency.”

3 Bove and Ruggeri, “Kinds of Blue”; Hultman, Kathman, and Shannon, “UN Peacekeeping and Civilian Protection”, Ruggeri, Dorussen, and Gizelis, “Winning the Peace Locally”; and Kathman and Wood, “Stopping the Killing During the ‘Peace.’”

4 Cil et al., “Mapping Blue Helmets.”

5 Hovil, “UN Peacekeepers in South Sudan”; IOM, “If We Leave We Are Killed”; and Williams, “Key Questions.”

6 For instance, Fortna, “Does Peackeeping Keep Peace?”; Gilligan and Sergenti, “Do UN Interventions Cause Peace?”; and Koops et al., “Peacekeeping in the Twenty-First Century.”

7 Hultman, Kathman, and Shannon, “UN Peacekeeping and Civilian Protection.”

8 Kathman and Wood, “Stopping the Killing.”

9 Bove and Ruggeri, “Kinds of Blue.”

10 Fjelde, Hultman, and Nilsson, “Protection Through Presence.”

11 Koops et al., “Peacekeeping in the Twenty-First Century.”

12 Adhikari, “The Plight of the Forgotten Ones”; Adhikari, “Conflict-Induced Displacement”; Davenport et al., “Sometimes You Just Have to Leave”; and Melander and Öberg, “Time to Go?”

13 Ruggeri and Costalli, “Peace at Home?”

14 Adhikari, “The Plight of the Forgotten Ones”; Adhikari, “Conflict-Induced Displacement”; and Steele, “Seeking Safety.”

15 Adhikari, “Conflict-Induced Displacement”; Davenport et al., “Sometimes You Just Have to Leave”; and Steele, “Seeking Safety.”

16 Davenport et al., “Sometimes You Just Have to Leave.”

17 Melander and Öberg, “Time to Go?”

18 Adhikari, “The Plight of the Forgotten Ones”; Adhikari, “Conflict-Induced Displacement”; also Moore and Shellman, “Fear of Persecution”; and Weiner, “Bad Neighbors, Bad Neighborhoods.”

19 Hultman et al., “UN Peacekeeping and Civilian Protection”; Hultman et al., “Beyond Keeping Peace”; and Kathman and Wood, “Stopping the Killing.”

20 Lindberg Bromley, “MINUSMA and Mali’s Precarious Peace”; Ruggeri, Dorussen, and Gizelis, “Winning the Peace Locally”; and Hultman et al., “UN Peacekeeping and Civilian Protection.”

21 Lindberg Bromley, “MINUSMA and Mali’s Precarious Peace.”

22 Fjelde et al., “Protection Through Presence”; Hultman et al., “Beyond Keeping Peace”; and Ruggeri Dorussen, and Gizelis, “Winning the Peace Locally.”

23 Lindberg Bromley, “MINUSMA and Mali’s Precarious Peace”. See also Posen, “Military Responses” for a discussion on types of military means to halt displacement.

24 Beber et al., “Challenges and Pitfalls of Peacekeeping Economies”; and Carnahan, Gilmore, and Durch, “New Data on the Economic Impact of UN Peacekeeping.”

25 Müller and Bashar, “UNAMID Is Just Like Clouds”. See also Stefanovic and Loizides, “Peaceful Returns,” for an overview of perceptional factors that guide the choices of displaced.

26 UNMISS, “UNMISS: Mandate.”

27 UNSC, “UNSC 2304 (2016)”; and UNMISS, “UNMISS: Mandate.”

28 IOM, “If We Leave We Are Killed”; IRRI, “Protecting Some of the People”; Sharland and Gorur, “Revising the Mandate in South Sudan”; and Williams, “Key Questions.”

29 Sharland and Gorur, “Revising the Mandate in South Sudan”; and Williams, “Key Questions.”

30 UNSC, “UNSC 2304 (2016).”

31 Duursma, “Obstruction and Intimidation.”

32 UN HQ Board of Inquiry, “Notes to Correspondents.”

33 Hovil, “UN Peacekeepers in South Sudan”; IOM, “If We Leave We Are Killed”; and IRRI, “Protecting Some of the People.”

34 Cil et al., “Mapping Blue Helmets.”

35 Fjelde et al., “Protection Through Presence”; and Ruggeri, Dorussen, and Gizelis, “On the Frontline Every Day.”

36 Costalli, “Does Peacekeeping Work?”; Powers, Reeder, and Townsen, “Hot Spot Peacekeeping”; and Ruggeri et al., “On the Frontline Every Day.”

37 Sundberg and Melander, “Introducing the UCDP GED.”

38 Ho et al., “Matching as Nonparametric Preprocessing.”

39 Adhikari, “The Plight of the Forgotten Ones”; Adhikari, “Conflict-Induced Displacement”; and Townsen and Reeder, “Where Do Peacekeepers Go.”

40 De Juan and Pierskalla, “Manpower to Coerce and Co-opt”; Ruggeri, Dorussen, and Gizelis, “On the Frontlines Every Day”; also Powers et al., “Hot Spot Peacekeeping.”

41 Buhaug and Gates, “The Geography of Civil War”; and Powers et al., “Hot Spot Peacekeeping.”

42 Powers et al., “Hot Spot Peacekeeping.”

43 National Bureau of Statistics, “Statistical Yearbook for Southern Sudan 2009.”

44 De Juan and Pierskalla, “Manpower to Coerce and Co-opt.”

45 As pointed out by one anonymous reviewer the static nature of many of the control variables accounts for much of the difficulty in removing imbalance.

46 In the zero-inflated negative binomial models I use the UCDP best estimate of fatalities (taken from the UCDP GED), the log of population, and historical violence to model excess zeros.

47 Ho et al., “Matching as Nonparametric Preprocessing”; and King and Zeng, “When Can History Be Our Guide?”

48 Gilligan and Sergenti, “Do UN Interventions Cause Peace?”

49 Ruggeri, Dorussen, and Gizelis, “Winning the Peace Locally.”

50 Fjelde, Hultman, and Nilsson, “Protection Through Presence.”

51 IOM, “If We Leave We Are Killed”; and UNMISS, “UNMISS PoC Sites.”

52 IRRI, “Protecting Some of the People”; and Sharland and Gorur, “Revising the Mandate in South Sudan.”

53 Bove and Ruggeri, “Kinds of Blue”; and Haas and Ansorg, “Better Peacekeepers, Better Protection?”

54 Fjelde et al., “Protection Through Presence”; and Ruggeri, Dorussen, and Gizelis, “Winning the Peace Locally.”

55 Costalli, “Does Peacekeeping Work?” 375.

56 Marin and Mayer-Rieckh, “The UN and East Timor”; and Sambanis, “The UN Operation in Cyprus.”

57 Duursma, “Obstruction and Intimidation.”

58 Posen, “Military Responses.”

59 Haas and Ansorg, “Better Peacekeepers, Better Protection?”

Bibliography

- Adhikari, Prakash. “The Plight of the Forgotten Ones: Civil War and Forced Migration.” International Studies Quarterly 56 (2012): 590–606.

- Adhikari, Prakash. “Conflict-Induced Displacement, Understanding the Causes of Flight.” American Journal of Political Science 57, no. 1 (2013): 82–9.

- Beber, Bernd, Michael Gilligan, Jenny Guardado, and Sabrina Karim. “Challenges and Pitfalls of Peacekeeping Economies.” Unpublished Manuscript, 2017.

- Bove, Vincenzo, and Andrea Ruggeri. “Kinds of Blue: Diversity in Un Peacekeeping Missions and Civilian Protection.” British Journal of Political Science 46, no. 3 (2016): 681–700.

- Buhaug, Halvard, and Scott Gates. “The Geography of Civil War.” Journal of Peace Research 39, no. 4 (2002): 417–33.

- Carnahan, Michael, Scott Gilmore, and William Durch. “New Data on the Economic Impact of UN Peacekeeping.” International Peacekeeping 14, no. 3 (2007): 384–402.

- Cil, Deniz, Hanne Fjelde, Lisa Hultman, and Desirée Nilsson. “Mapping Blue Helmet: Introducing the Geo-Coded Peacekeeping Operations (Geo-PKO) Dataset.” 2018.

- Costalli, Stefano. “Does Peacekeeping Work? A Disaggregated Analysis of Deployment and Violence Reduction in the Bosnian War.” British Journal of Political Science 44, no. 2 (2013): 357–80.

- Costalli, Stefano, and Andrea Ruggeri. “Peace at Home? Un Peacekeeping Operations, Refugees, Returned Refuees and IDPs.” Folke Bernadotte Workshop, Addis Ababa, October 2017.

- Davenport, Christian, Will H. Moore, and Steven Poe. “Sometimes You Just Have to Leave: Domestic Threats and Forced Migration, 1964–1989.” International Interactions 29, no. 1 (2003): 27–55.

- De Juan, Alexander, and Jan Henryk Pierskalla. “Manpower to Coerce and Co-Opt: State Capacity and Political Violence in Southern Sudan 2006–2010.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 32, no. 2 (2015): 175–99.

- Duursma, Allard. “Obstruction and Intimidation of Peacekeepers: How Armed Actors Undermine Civilian Protection Efforts.” Journal of Peace Research 56, no. 2 (2019): 234–48.

- Fjelde, Hanne, Lisa Hultman, and Desirée Nilsson. “Protection Through Presence: UN Peacekeeping and the Costs of Targeting Civilians.” International Organization 73, no. 1 (2019): 103–31.

- Fortna, Page. “Does Peacekeeping Keep Peace? International Intervention and the Duration of Peace After Civil War.” International Studies Quarterly 48, no. 2 (2004): 269–92.

- Gilligan, Michael, and Ernest Sergenti. “Do UN Inverventions Cause Peace? Using Matching to Improve Causal Inference.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 3, no. 2 (2008): 89–122.

- Haass, Felix, and Nadine Ansorg. “Better Peacekeepers, Better Protection? Troop Quality of United Nations Peace Operations and Violence against Civilians.” Journal of Peace Research 55, no. 16 (2018): 742–58.

- Ho, Daniel E., Kosuke Imai, Gary King, and Elizabeth A. Stuart. “Matching as Nonparametric Preprocessing for Reducing Model Dependence in Parametric Causal Inference.” Political Analysis 15 (2007): 199–236.

- Hovil, Lucy. “UN Peacekeepers in South Sudan: Protecting Some of the People Some of the Time.” African Arguments, 2015.

- Hultman, Lisa, Jacob Kathman, and Megan Shannon. “United Nations Peacekeeping and Civilian Protection in Civil War.” American Journal of Political Science 57, no. 4 (2013): 875–91.

- Hultman, Lisa, Jacob Kathman, and Megan Shannon. “Beyond Keeping Peace: United Nations Effectiveness in the Midst of Fighting.” American Political Science Review 108, no. 4 (2014): 737–53.

- IDMC. “Global Report on Internal Displacement 2017.” Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 2017.

- IOM. “If We Leave We Are Killed: Lessons Learned from South Sudan Protection of Civilians Sites 2013–2016.” International Organization for Migration and Government of Switzerland, 2016.

- IRRI. “Protecting Some of the People Some of the Time: Civilian Perspectives on Peacekeeping Forces in South Sudan.” International Refugee Rights Initiative, 2015.

- Kathman, Jacob, and Reed M. Wood. “Stopping the Killing During the ‘Peace’: Peacekeeping and the Severity of Postconflict Civilian Victimization.” Foreign Policy Analysis 12, no. 2 (2016): 149–69.

- King, Gary, and Langche Zeng. “When Can History Be Our Guide? The Pitfalls of Counterfactual Inference.” International Studies Quarterly 51 (2007): 183–210.

- Koops, Joachim A., Norrie MacQueen, Thierry Tardy, and Paul D. Williams. “Introduction: Peacekeeping in the Twenty-First Century.” In Oxford Handbook of United Nations Peacekeeping Operations, ed. Joachim A. Koops, Norrie MacQueen, Thierry Tardy, and Paul D. Williams. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Lindberg Bromley, Sara. Minusma and Mali’s Precarious Peace: Challenges for United Nations Peacekeeping in Contexts of Insecurity. Uppsala: Department of Peace and Conflict Research, 2018.

- Martin, Ian, and Alexander Mayer-Rieckh. “The United Nations and East Timor: From Self-Determination to State-Building.” International Peacekeeping 12, no. 1 (2005): 125–45.

- Melander, Erik, and Magnus Öberg. “Time to Go? Duration Dependence in Forced Migration.” International Interactions 32, no. 2 (2006): 129–52.

- Moore, Will H., and Stephen M. Shellman. “Fear of Persecution: Forced Migration, 1952–1995.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 40, no. 5 (2004): 723–45.

- Müller, Tanja R., and Zuhair Bashar. “‘UNAMID Is Just Like Cloudes in Summer, They Never Rain’: Local Perceptions of Conflict and the Effectiveness of UN Peacekeeping Missions.” International Peacekeeping 42, no. 5 (2017): 756–79.

- National Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Yearbook for Southern Sudan 2009. Ed. National Bureau of Statistics. Juba: Republic of South Sudan, 2010.

- Posen, Barry R. “Military Responses to Refugee Disasters.” International Security 21, no. 1 (1996): 72–111.

- Powers, Matthew, Bryce W. Reeder, and Ashly Adam Townsen. “Hot Spot Peacekeeping.” International Studies Review 17, no. 1 (2015): 46–66.

- Reliefweb. “South Sudan Situation – Responding to the Needs of Displaced South Sudanese and Refugees, Supplementary Appeal January–December 2018.” 2018.

- Ruggeri, Andrea, Han Dorussen, and Theodora-Ismene Gizelis. “On the Frontline Every Day? Subnational Deployment of United Nations Peacekeepers “.” British Journal of Political Science (2016.

- Ruggeri, Andrea, Han Dorussen, and Theodora-Ismene Gizelis. “Winning the Peace Locally: UN Peacekeeping and Local Conflict.” International Organization 71, no. 1 (2017): 163–85.

- Sambanis, Nicholas. “The UN Operation in Cyprus: A New look at the Peacekeeping-Peacemaking Relationship.” International Peacekeeping 6, no. 1 (1999): 79–108.

- Sharland, Lisa, and Aditi Gorur. “Revising the UN Peacekeeping Mandate in South Sudan: Maintaining Focus on the Protection of Civilians.” The Stimson Center and the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2015.

- Steele, Abbey. “Seeking Safety: Avoiding Displacement and Choosing Destinations in Civil Wars.” Journal of Peace Research 46, no. 3 (2009): 419–30.

- Stefanovic, Djordje, and Neophytos Loizides. “Peaceful Returns: Reversing Ethnic Cleansing After the Bosnian War.” International Migration 55, no. 5 (2017): 217–34.

- Sundberg, Ralph, and Erik Melander. “Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 50, no. 4 (2013): 523–32.

- Townsen, Ashly Adam, and Bryce W. Reeder. “Where Do Peacekeepers Go When They Go?” Journal of International Peacekeeping 18, no. 2 (2014): 69–91.

- UNHCR. “UNHCR – South Sudan Emergency.” http://www.unhcr.org/south-sudan-emergency.html.

- UN Headquarters Board of Inquiry. Note to Correspondents: Board of Inquiry Report on Malakal. Ed. UN Department of Field Support. New York, NY: UN, 2016.

- UNMISS. “UNMISS PoC Sites Update No.195.” Ed. Media and Spokesperson Unit and Communications and Public Information Section: UNMISS. 2018.

- UNMISS. “UNMISS: Mandate.” https://unmiss.unmissions.org/mandate.

- UN Security Council. “United Nations Security Council Resolution 2304 (2016).” New York, USA, 2016.

- Weiner, Myron. “Bad Neighbors, Bad Neighborhoods: An Inquiry into the Causes of Refugee Flows.” International Security 21, no. 1 (1996): 5–42.

- Williams, Paul D. “Key Questions for South Sudan’s New Protection Force.” IPI Global Observatory (2016.

- Wood, Reed M., Jacob Kathman, and Stephen E. Gent. “Armed Intervention and Civilian Victimization in Intrastate Conflicts.” Journal of Peace Research 49, no. 5 (2012): 647–60.