Introduction: Enhancing Dialogue and Research

Louise Olsson and Angela Muvumba Sellström

Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and Uppsala University

Since the adoption of UNSCR 1820 in 2008, United Nations peacekeeping operations have come under increased pressure to prevent conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) conducted by local security actors. Still, the outcomes from peacekeeping preventive actions are reported to often fall far short of public expectations.Footnote1 To address that problem, there is an ongoing debate on how to enhance peacekeeping operations’ effectiveness. For example, the UN Security Council held a Debate on CRSV on 23 April 2019 with the Nobel Peace Prize laureates Ms. Nadia Murad and Dr. Denis Mukwege speaking before the Council. The resolution adopted, UNSCR 2467, stated that the Security Council ‘[r]ecognizes the need to integrate the prevention, response and elimination of sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict situations […] including in relevant authorizations and renewals of the mandates of peace missions through the inclusion of operational provisions’. In preparations for the anniversary of UNSCR 1325 in 2020, the first resolution to recognize that violence targeting women is relevant for international peace and security, further calls on the UN to improve its track record of preventing CRSV is a critical theme. At the practitioner level, military forums are discussing how to clarify military responsibilities and improve their practical contributions to prevention.Footnote2 As noted by Lotze in this Forum: ‘Consolidating the gains made to date, and building on these for the future, will be key if the Security Council’s call to bring a total halt to CRSV is to be realized’ (see page 27).

Engaging with this debate on how to strengthen peacekeeping prevention of CRSV, this Forum explores the role of uniformed, primarily military, peacekeeping contingents and their interactions vis-à-vis local state- and non-state military organizations. As noted in the entries, state militaries tend to be more commonly represented among the perpetrators. This can constitute a specific challenge given the relationship between the host state and the peacekeeping operation.Footnote3 All entries in this Forum do, however, consider CRSV as preventable, here defined as systematic, proactive and/or reactive effort(s) to limit the perpetration of conflict-related sexual violence.Footnote4 While it is a frequent feature of many wars, research clearly demonstrates that CRSV is not an inevitable consequence. Many warring parties choose not to use it as a strategy or policy and simultaneously seek to prevent their members from engaging in its practice. This understanding of prevention thereby means that we discuss what research says are risk factors for military organizations’ carrying out, or allowing CRSV (see entries by Moncrief and Wood, Hoover Green, and Muvumba Sellström in this Forum) and how traits and practices of military peacekeeping contingents relate to such factors (see Johansson, Ruffa, Sjoberg and Lotze).Footnote5 We further take as a starting point that when severe and persistent CRSV does occur, there is variation in form, targeting, and frequencies between and within warring parties and conflicts. Such variations and nuances mean that peacekeeping policy can learn from the warring actors’ successful and unsuccessful efforts to control and limit this violence.

Enhancing Dialogues on CRSV and Peacekeeping Operations

To support research and practical learning, this Forum brings together leading researchers on CRSV and on peacekeeping operations in dialogue. This is important, as few research projects on peacekeeping operations thus far have directly studied CRSV.Footnote6 In engaging with the policy debate, the Forum seeks to deepen the dialogue between researchers and key decision-makers, including contributions comprising direct experiences of working to prevent CRSV. This is critical as there appears to be a widening gap between a quickly developing systematic research front and the dominant policy narrative in two respects.

First, we are currently seeing a rise in the production of high-quality evidence and results relevant for peacekeeping operations and CRSV (see Moncrief and Wood and Johansson in this Forum for an overview). These results can be used to enhance political will and for formulating targeted mandate objectives which can contribute to successfully preventing violence. That said, recent results have additionally entailed that research now takes issue with some of the more fundamental policy statements on CRSV. Most notably, research remains hesitant to the persistent labelling of CRSV as a ‘weapon of war’ and with the claim that CRSV is primarily driven by societal gender inequality. As demonstrated in this Forum, empirical research often finds the opposite; while CRSV occasionally can be ordered as a weapon, it is generally more likely to be tolerated or to be perceived as impossible to stop by a weak military leadership.Footnote7 This means that peacekeeping operations need to increasingly focus on understanding the features of the groups responsible and to be able to differentiate between CRSV which is the result of leadership orders (a strategy/policy), and CRSV which is the result of the leadership’s lack of control (a practice).Footnote8 Importantly, as the Forum will show, the fact that sexual violence can occur in different forms and varies across different types of actors as well as within armed organizations in the same geographical area makes the explanation of societal gender inequality unlikely.Footnote9 We agree that support to gender equality is imperative and can serve to provide vital support to the voices of victims of violence; central for strengthening processes where women survivors mobilize for rights and resources.Footnote10 But research does clearly suggest that only focusing on gender equality might not be the most effective peacekeeping strategy for preventing further CRSV by a warring party.

Second, concurrently, peacekeeping prevention policy has been shaped by fairly extreme instances of CRSV as interventions have had to prioritize responses to atrocity.Footnote11 This has entailed gathering empirical information about the violence committed in detention camps by Bosnian Serbs, the Interhamwe during the Rwandan genocide, the myriad militia and state actors in the DRC, and, more recently, the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham Islamic State (IS). These are very serious situations. However, in addition to these, research clearly shows that only a minority of armed political and security organizations commit widespread or pernicious sexual violence in conflict. While there are always difficulties to document and count CRSV,Footnote12 Cohen and Nordås, covering 129 active conflicts involving 625 armed actors for the period 1989–2009, find that 43% of the individual conflicts had no reports of this form of violence.Footnote13 Muvumba Sellström’s events-based dataset between 1989 and 2011 of 23 armed actors in sub-Saharan Africa,Footnote14 shows that only eight actors were reported as responsible for 68% of abuses and assaults. While policies to anticipate violence through peacekeeping mandates and intervention practices have thus originated in models of pathology, it is important to now continue to move toward including lessons on institutions, norms, and preferences that exist where there are robust measures against sexual violence. This move toward nuance further underlines the need for continuously improved collaboration between researchers, policy-makers and practitioners in order to collect and analyse better data.

This Forum engages in dialogue with these two contentions in several important respects. The first three contributions set the frame by outlining key findings from systematic empiricist research on CRSV (Moncrief and Wood) and on peacekeeping operations (Johansson), and provide insights from ongoing operations (Lotze). Johansson notes that it has been nearly twenty years since Skjelsbaek observed that CRSV poses a particular challenge to peacekeeping operations. Johansson suggests that (a) a more systematic approach is needed in the response to CRSV; and that (b) peacekeeping operations are not as effective in preventing CRSV as they are in stopping the killing of civilians. To address this, Moncrief and Wood argue that there is a need to better understand the military organizations responsible for CRSV – their culture, structures, ideology, leadership and social norms in relation to training – before effective preventive measures can be developed (a point backed up by Ruffa, Hoover Green and Muvumba Sellström). Moreover, an analysis in preparation for an operation cannot assume civilian women victims. We need to take seriously that men and boys, and sexual minorities, are also targeted and we need to consider the risk for intra-force victims (see also Sjöberg and Lotze).Footnote15 Lotze, drawing on research and his own peacekeeping experiences, thereafter provides key insights on these dynamics from the internal viewpoint of UN peacekeeping operations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) working in cooperation with the DRC Government to prevent CRSV. Lotze outlines a two-tracked approach: (1) by conditioning that elements of the state armed forces which committed violations against the civilian population would not be eligible for UN support; and (2) by providing assistance to the government’s military justice system in the fight against impunity, including a focus on holding higher ranking officers responsible.

Two entries then scrutinize what key traits the military peacekeeping contingents bring with them when deployed – military culture and understanding of professional responsibilities (Ruffa) and command and control and discipline (Hoover Green) – mean for prevention of CRSV, finding common concerns relevant for also addressing sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA). Ruffa’s commentary underlines that preventing CRSV has never been seen as a core task of most state military organizations. This means that the understanding of the problem, the sense of responsibility, as well as the practical capacity are likely to be low among many peacekeeping contingents when they are deployed. But while military contingents bring additionally potential problematic traits with them to the field, it can be difficult to realize prevention of CRSV through other channels. Hoover Green argues that CRSV more frequently is the result of a failure of military organizations to uphold command and control rather than it being a strategy. This means, she argues, that core military traits affecting the military personnel’s expectations about detection and discipline can drive the perpetration of unordered sexual violence. As suggested by both Ruffa and Hoover Green, formal and informal learning between military organizations – peacekeeping contingents and the host state’s military organization – could constitute a venue for prevention but only under the condition that it is used in an aware and conscious manner by the peacekeeping contingents.

The Forum further nuances this discussion by empirically illustrating prevention dynamics in local non-state military organizations. Muvumba Sellström offers insights from two different rebel groups from Burundi’s civil war (1994–2008), the CNDD-FDD and Palipehutu-FNL, which despite their many similarities, developed different approaches to CRSV. This resulted in one creating a more permissive environment and the other establishing a preventive culture. The result was different levels of CRSV conducted by these groups. Drawing on her own experiences from working with armed non-state actors to create such preventive regimes, Sjöberg suggests that there often is a need to improve the responsible organization’s understanding of international humanitarian law and support the development of codes of conduct and rules of engagement in order to be able to prevent CRSV. Such military documents, she claims, have to be owned by the group itself. In creating space for such policies, broader discussion on both gender equality and sexual violence have proven important for progress in spite of expectations of the opposite.

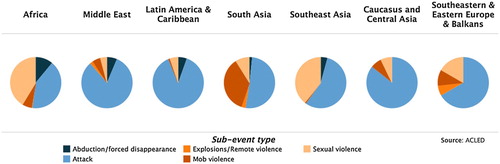

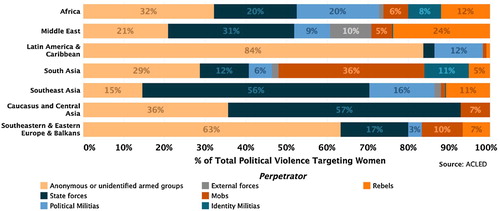

Finally, a common underlying theme in the Forum is the discussion of how efforts for peacekeeping prevention of CRSV should be understood in relation to the prevention of other forms of violence, such as, SEA (Ruffa and Hoover Green), and sexual violence more broadly (Sjöberg). Kishi makes a central contribution to this theme by arguing that it is important for a peacekeeping operation to better understand trends in many forms of violence targeting women and how these relate to women’s political agency. This allows for (a) more contextually appropriate and comprehensive protective measures which enable continued participation, and (b) ensures that preventive peacekeeping measures avoid contributing to a stereotyping of women as only victims of CRSV.Footnote16 For example, in addition to CRSV, abductions, forced disappearances, and mob violence, disproportionately affects women. The gender aware conflict analysis called for by the UN Secretary General in his 2019 report on Women, Peace and Security (S/2019/800) is consequently central.

Future Research: Moving Forward on Peacekeeping Prevention

By engaging in dialogue between research fields and with policy, the authors in this Forum collectively provide additional essential insights for developing research on peacekeeping prevention, that is, systematic, proactive and/or reactive effort(s) to limit the perpetration of conflict-related sexual violence, beyond this Forum. The shared insights and exchanges contribute in two respects: (a) they underline the need to move toward understanding prevention as a multi-level, multi-actor interactive process which is more comprehensive than fighting impunity; and (b) we need to develop indicators which offer insights into ongoing internal processes of military organizations in order to estimate risk and to understand how to effectively prevent CRSV.

Let us look closer at these two aspects. First, impunity is much in focus of current efforts. We agree that enacting legal recourse and justice are critical. However, the Forum demonstrates that prevention can be thought of as a multi-level, multi-actor process involving the peacekeeping operation interacting with the host government and local security forces. We claim that prevention involves removing the root causes through these interactions by altering the conditions in the organizations that precipitate CRSV. Practically, in the short term, peacekeeping prevention means promoting the exchange of information between military organizations in order for them to develop the capacity to effectively interact on CRSV prevention, create and guard humanitarian safe spaces, and other efforts which can reduce opportunity. Such efforts need to enhance the understanding of diverse victim groups, including men and boys. As this Forum has demonstrated, there are additional long-term measures needed. These should clarify and integrate the responsibility for preventing CRSV in the military profession – in countries contributing to peacekeeping operations and in those hosting operations – and involve discussions on military culture and training. That state military organizations deploying troops to a peacekeeping operation practice at home what they preach in theatre has to be a cornerstone. This is imperative for credibility and for overcoming state-to-state sensitivities.

Second, as all multi-actor processes, implementing prevention is contingent upon the nature and position of the involved organizations and their role within a conflict. To contribute to this continuous adaption to context, this Forum suggests that it is difficult to discuss prevention solely based on reported incidents of violence. Such reports are difficult to interpret when analysed separately from other indicators. For example, reports of violence might indicate either a rampant problem or an established accountability mechanism. Thus, this Forum proposes that we should capture prevention by combining formal and informal indicators. Formal indicators might include adopted codes of conduct; political education messaging; documentation to name and shame, such as listing credibly suspected perpetrators; sanctions; and penalties and judgments. These demonstrate active efforts by an organization to stop or deter violence. Informal indicators seek to capture social norms which can involve what can be construed as sexual misconduct and include sexual symbolism that disparages sexual coercion; or socialization among peers that promotes sexual cultures of consent and stigmatizes sexual predators. A combination of formal and informal indicators, we argue, would make it possible to create typologies of particular regimes of prevention and then to systematically examine their respective potential impact on the level of CRSV. Thereby, research and policy can jointly contribute with knowledge relevant for meeting the Security Council’s objective of eliminating CRSV.

Understanding Conflict-Related Sexual Violence: What Peacekeepers Should Know

Stephen Moncrief and Elisabeth Jean Wood

Yale University

Conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) poses a difficult challenge for peacekeeping operations in the aftermath of armed conflict. Sexual violence by combatants, or former combatants, may continue after conflict’s supposed end. It often leaves profound legacies of displaced families, transformed communities, and ruptured social networks in its wake.

That rape and other forms of sexual violence by combatants during and after war now loom large on the peacekeeping agenda is an achievement of the international women’s movement, one largely driven by the narrative that, when frequent, rape during war is a strategy.Footnote17 Peacekeeping operations are increasingly tasked with preventing and addressing CRSV; to do so effectively requires understanding its patterns and drivers. Some armed actors do purposefully adopt rape as a strategy (that is, in pursuit of military objectives); others adopt rape as a policy for some other purpose (often, to manage the sexual and reproductive lives of combatants). However, members of other organizations engage in high levels of rape not because it is a policy, but because it is driven by social dynamics among combatants and tolerated by commanders. In such cases, it is a ‘practice’ of war.

In this commentary, we analyse the implications of recent social science research for efforts by peacekeeping operations to prevent, or at least mitigate, CRSV. We first document the sharp variation across armed actors (state forces, rebel organizations, or militias) in patterns of CRSV, emphasizing that some engage in little sexual violence of any form. Rape is thus not inevitable during war, which suggests that peacekeeping policy can make a difference if properly attuned to why it occurs. We distinguish between CRSV as a policy of the armed organization (whether adopted as a military strategy or to manage the sexual and reproductive lives of combatants), and its occurrence as a practice. We then analyse challenges to prevention posed by the complex patterns of CRSV. Finally, we discuss the implications for efforts by peacekeeping operations to address CRSV, and suggest how peacekeepers might most effectively combat sexual violence.

Variation in Patterns of Conflict-Related Sexual Violence

Perhaps the most important social science finding is that CRSV varies sharply in form (rape, sexual torture, forced abortion, etc.), targeting (against what social group), and frequency across armed organizations.Footnote18 Some organizations target only women and girls, while others target males as well; still others also target sexual and gender minorities.Footnote19 And some organizations target specific social groups with particular forms of sexual violence, as in the case of the Islamic State, which sexually enslaved Yazidi but not Sunni Muslim girls and women.

Crucial for peacekeeping operations is the particular finding that rape by combatants can be effectively prohibited. For example, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front engaged in little CRSV during El Salvador’s civil war (1980–1992) – even as state forces committed widespread rape during massacres and sexually tortured political prisoners.Footnote20 There is of course severe under-reporting of rape and other forms of sexual violence, but the documented differences are too sharp to only reflect differences in reporting.

Because CRSV can be effectively prohibited, it is not inevitable in war or its aftermath. Peacekeeping policy toward sexual violence therefore matters. If state forces are susceptible to international sanction, or interact frequently with peacekeeping personnel in the context of reform programs, there is an opportunity to advance CRSV prevention efforts, especially because the fraction of state forces that engage in moderate to high levels of CRSV is higher than the fraction of rebel organizations that do so.Footnote21

To be sure, some armed organizations do engage in high levels of CRSV. Some do so as a military strategy purposefully adopted as organizational policy during ethnic cleansing, genocide, or sexual torture (in some settings). Examples include state forces during Guatemala’s civil war, Bosnian Serb militias in the former Yugoslavia, Janjaweed militias in Sudan, Hutu forces in Rwanda, and the Myanmar military.Footnote22

However, some armed actors adopt some form of sexual violence as organizational policy not as a military strategy, but as a way to manage and regulate the sexual and reproductive lives of combatants.Footnote23 Examples include the sexual enslavement of Yazidi women and girls by the Islamic State and the forced prostitution of women held in brothels by the Japanese military during World War II.

When some form of CRSV against some social group(s) is adopted as an organizational policy (whether for strategic or other reasons), it may be authorized by commanders, but not ordered. Neither Japanese soldiers nor Islamic State combatants were ordered to sexually abuse civilians, but were authorized to do so under specific conditions.

A fundamental challenge to the effective prevention of CRSV is that it may be committed frequently by combatants without having been ordered or authorized as an organizational policy. Rape by American soldiers in the Vietnam War was frequent because it was tolerated by US commanders and driven by peer social dynamics – rape was a practice. During formal and civic investigations, US soldiers claimed that they had been ordered or authorized to kill civilians but did not make the same claim for rape.Footnote24 Several, however, mentioned social pressure to participate; very few were prosecuted.

Patterns of rape in other wartime contexts are also well characterized as a practice. Gang rape builds cohesion among the recruits of those insurgencies and state forces that rely on abduction and press-ganging (respectively).Footnote25 Rape in these cases is not purposefully adopted by commanders as policy; rather, members of small units participate and insist that all recruits – including women – participate.

When entrenched as a practice, rape (or other forms of sexual violence) may be difficult to eradicate. For example, a pattern of sexual assault of both men and women within the ranks of the US military has persisted despite two decades of claimed but not realized ‘zero tolerance’.Footnote26 Each year, almost 5% of active duty servicewomen and 1% of men experience sexual assault by a colleague(s). The frequency of gang rape and retaliation by peers as well as the perpetrator against the survivor for reporting suggest that sexual assault is largely driven by social dynamics.

Rape, or some other form of CRSV, is likely to be frequent as a practice when both combatants and commanders act on gendered norms and beliefs that license sexual violence against certain populations as acceptable despite its formal prohibition. Combatants may believe in such norms and hold such beliefs if they are recruited from a society that itself permits sexual violence against a particular population. Or they may come to hold new norms and beliefs through a process of peer socialization, which may itself be violent, that transforms recruits’ norms, proclivities, and beliefs toward participation in CRSV, often including exceptionally brutal forms of rape, including gang rape (very frequent in war). Commanders may tolerate CRSV for various reasons. The commander may think its effective prohibition would be too costly because it would require disciplining otherwise effective subordinates; might divert scarce resources to an issue he sees as unimportant; or might undermine vertical cohesion, perhaps because it would lessen the respect of subordinates for him. Or he may tolerate rape because he is little troubled by the suffering of those targeted, because it is too much trouble, because he himself engages in rape, or is too weak to effectively enforce the organization’s norms and rules. The commander acts on an understanding of the benefits and costs of toleration that reflect his own gendered norms and beliefs.

Implications for Peacekeeping Operations

Peacekeeping operations are increasingly mandated to respond to, and prevent, conflict-related sexual violence.Footnote27 However, as Johannson (this issue) notes, research on peacekeeping operations and CRSV is at a relatively early stage. Johannson and Hultman argue that peacekeeping operations may not be efficient tools for responding to CRSV, and may be most effective when (1) the peacekeeping operation has a protection mandate and (2) armed organizations have strong internal control.Footnote28 Kirshner and Miller’s results are more optimistic, and they note the role civilian personnel may play in promoting institutional responses to CRSV.Footnote29 Peacekeeping personnel can reduce the power of combatants to victimize civilians, and the presence of international observers who document and punish CRSV may discourage potential perpetrators.Footnote30 Further, some peacekeeping operations now attempt to reform security institutions and strengthen formal justice mechanisms in conflict-affected areas, which can complement efforts to mitigate CRSV and prevent sexual violence in the future.Footnote31 In this section, we highlight nine implications of recent academic research on CRSV, and discuss these implications in the context of peacekeeping.

First, whether an armed group commits high or low levels of CRSV, its institutions and organizational culture must be understood. CRSV – its form, targeting and frequency – varies across armed organizations, sometimes within the same conflict.Footnote32 While an organization’s sexual practices may reflect the broader society’s gender hierarchies, it is imperative to understand an armed group’s internal institutions and organizational culture. These features can help explain whether (and why) a particular armed organization practices restraint, or engages in frequent CRSV. This is crucial information for peacekeeping operations that seek to understand and address CRSV. For example, Johannson and Hultman (see note 28) suggest that the nature of armed group institutions, particularly as they relate to internal control, might condition the effectiveness of peacekeeping operations seeking to reduce CRSV.

Second, CRSV does not only affect women. Although commonly framed as a ‘women’s issue’, we emphasize that there is a wider range of CRSV survivors (and perpetrators) than is often assumed, and sensitivity to this diversity can help strengthen peacekeeping operations’ responses to CRSV. Many of the UN’s early warning indicators justifiably emphasize threats to women and girls, and Women’s Protection Advisors play a key role in monitoring and analysing CRSV during peacekeeping operations. However, we note that men and boys, as well as sexual and gender minorities, may also be targeted. This has implications for how CRSV should be addressed after it occurs. The needs of diverse survivors may differ because of social and legal contexts, especially in places where homosexual acts (even if by violence) are considered crimes, or are deeply stigmatized.Footnote33 Specialized services may also be necessary if diverse survivors were targeted for different types of CRSV (e.g. women for forced pregnancy or abortion, but men for sterilization or sexual mutilation). Further, female combatants may also be perpetrators, particularly among groups that recruit forcibly and practice gang rape. As evidence from Sierra Leone suggests, this is a more common phenomenon than prevailing assumptions about CRSV would predict.Footnote34

Third, CRSV does not only affect civilians. While many peacekeeping imperatives justifiably emphasize threats to civilians, intra-force sexual assault may also be prevalent.Footnote35 When peacekeeping operations are implementing or facilitating DDR programs, some demobilized combatants may require additional, specialized services if they were targeted for intra-force sexual assault.

Fourth, peacekeeping personnel documenting CRSV should look for evidence of its emergence not just as a policy, but also as a practice. Rhetoric suggesting that sexual violence has been authorized, rather than directly ordered, may constitute evidence of sexual violence as an organizational policy.Footnote36 However, peacekeeping personnel should also look for evidence that commanders do not punish CRSV, despite its formal prohibition. This can advance the cause of post-conflict justice and accountability, and advance prevention efforts.

Fifth, whether a policy or practice, commanders are responsible for restraining, promoting, or tolerating combatants’ use of sexual violence. Toleration by commanders is a necessary condition for the emergence of CRSV as a practice by members of an organization. When an armed organization perpetrates CRSV, commanders as well as individual perpetrators should be held legally accountable. If peacekeeping personnel are able to gather evidence of CRSV as a practice, it may strengthen justice and accountability efforts. Seelinger and Wood (Citationforthcoming) suggest that sexual violence, even when it occurs as a practice rather than a policy, can be charged and prosecuted as a core international crime.Footnote37

Sixth, the emergence of CRSV as a practice entails a difficult challenge for peacekeeping operations. Because CRSV may emerge as a practice and become embedded within an armed organization’s culture, peacekeeping personnel may face a particular challenge in addressing this type of violence, especially if it is a long-running feature of life in the armed organization.Footnote38 However, there are avenues for addressing CRSV as a practice. Changing the gendered norms that facilitate both the violence itself, and commanders’ toleration of it, will be crucial to ending CRSV as a practice, and will require cooperation among civil society groups, government entities, and other international actors, not just peacekeepers. Peacekeeping personnel may be able to promote long-term changes in attitudes toward sexual violence in society by supporting domestic justice institutions, as well as awareness-raising campaigns and support for survivor services.Footnote39 Ruffa (this issue) also highlights how military peacekeeping contingents might transfer norms of CRSV prevention. However, the short-term protection efforts of peacekeeping operations will remain indispensable.

Seventh, groups that continue to commit CRSV frequently should be identified, and pressured to end sexual violence. Because engaging in CRSV constitutes a choice, rather than an unavoidable wartime phenomenon, the UN should pressure commanders to declare and enforce prohibitions on sexual violence by their subordinates. This may be especially effective when an armed organization has strong internal institutions that allow commanders to punish combatants. Recent research suggests that organizations with high levels of internal control may be more responsive to the presence of peacekeeping personnel, and therefore more likely to show restraint.Footnote40

Eighth, organizational change should be encouraged. Both state and non-state organizations should be encouraged to declare and enforce prohibitions on sexual violence. Peacekeeping personnel interact with members of state security institutions, especially in the context of security sector reform, and several police and military institutions have worked with the Special Representative on CRSV ‘in order to develop specific, time-bound commitments and action plans to address violations’.Footnote41 However, the UN should continue to pressure non-state forces to prohibit and punish sexual violence as well. Geneva Call’s Deed of Commitment for the Prohibition of Sexual Violence in Situations of Armed Conflict and Towards the Elimination of Gender Discrimination may provide an example for how such commitments from armed non-state organizations could be structured.

Ninth, local efforts to address sexual violence through formal institutions should be supported. In the long term, the international community should support local efforts to build domestic institutions that address sexual violence. This may involve support to domestic justice institutions, as well as awareness raising and services for survivors. Recent research has also suggested that UN peacekeeping operations can help to rebuild the rule of law after a civil war ends,Footnote42 and formal justice institutions that prosecute sexual violence may deter its occurrence in the future. Peacekeeping personnel may also provide specialized training for members of the security sector that is specific to preventing sexual violence. However, we caution that while gender balancing efforts in post-conflict armed forces may be beneficial, they may not be sufficient to prevent CRSV. A recent study of the Liberian National Police does not find evidence that adding women to police teams increases a team’s sensitivity to gender-based or sexual violence.Footnote43

Conclusion

Conflict-related sexual violence constitutes a major challenge for peacekeeping operations. We have summarized recent research on CRSV and derived several implications for peacekeeping operations seeking to address this type of violence. We have described variation in form, targeting, and frequency, while also distinguishing between CRSV as a policy and CRSV as a practice. In particular, we highlight the importance of tailoring policy to whether the organization has adopted CRSV as a policy, or is tolerating CRSV as a practice. We emphasize holding both perpetrators and their commanders accountable for sexual violence, and we note the value of encouraging organizational change. Ultimately, both short and long-term efforts will be required to eradicate CRSV, and attention to the gender norms and internal institutions of armed organizations will be necessary for this endeavour.

Peacekeeping and Protection from Conflict-Related Sexual Violence

Karin Johansson

Uppsala University

Nearly twenty years have passed since SkjelsbaekFootnote44 concluded that conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) poses a particular challenge to United Nations (UN) peacekeeping operations. Since then, we have witnessed an increased attention to CRSV and a number of adjustments have been made within the UN Department of Peace Operations to adequately address CRSV in mandate implementation. For reasons related to data availability, it has only recently been possible to begin assessing the impact of these efforts statistically, over time, across peacekeeping operations and warring parties. Findings are not yet conclusive, leaving significant questions unanswered. To progress, I argue that we need to further strengthen partnerships between researchers, policy-makers, and practitioners. This would allow for more fine-grained analyses with higher external validity.

In this commentary, I share insights from empirical research focusing on peacekeeping operations effectiveness in mitigating CRSV perpetrated by warring parties. While bearing in mind the delimitations of our current data and the – only partial – conclusions we should draw from them, I highlight four findings: (1) the Security Council does respond to information about CRSV although not in a consistent way; (2) current peacekeeping operations practices succeed in curbing CRSV under certain circumstances, but the average success-rate in protecting civilians from CRSV is unclear; (3) peacekeeping operations, and their police contingents in particular, have an important role to play in securing that survivors’ voices are heard; and (4) despite the expectation that female peacekeeping personnel would be particularly well suited to combat CRSV, this remains largely unverified. To put the findings in perspective, I regularly conclude by clarifying what we still do not know and what is needed in order to improve our understanding of how peacekeeping operations adequately could prevent CRSV.

Evidence suggests that policy-makers increasingly pay attention to CRSV: The heightened number of country-specific resolutionsFootnote45; the increased probability of both peacekeeping deploymentFootnote46; and gender-mainstreamed mandatesFootnote47 indicate that the Security Council pays attention to CRSV. The amount of attention and responsiveness however varies. The link between CRSV and peacekeeping deployment seems to depend on the origin of the CRSV reports.Footnote48 Furthermore, the language in resolutions generallyFootnote49 and in peacekeeping mandates specificallyFootnote50 is inconsistent in the extent to which it reflects the overarching Women Peace and Security agenda. Equally concerning as the inconsistent response, is the limited knowledge we have about the adequacy of today’s peacekeeping practices as tools to address CRSV. This is the issue to which I turn next.

While a robust body of research demonstrates the life-saving impact of peacekeeping operations,Footnote51 the same cannot be said about its effect on CRSV. Theoretically, we could expect some of the mechanisms that prevent killings to protect against CRSV too. But there are also reasons to expect that CRSV requires specific considerations. Unless staged for a wider audience, CRSV often takes place in the private sphere far from military confrontations. Relatedly, military peacekeeping personnel – which constitutes the lion’s share of the entire operation – generally has very limited experience of managing and preventing CRSV.Footnote52 It is also worth considering that CRSV historically has been excluded from ceasefire and peace agreement stipulations,Footnote53 suggesting lower priority for peacekeeping operations and hence lower costs associated with such violations from the perspective of the warring parties. Notably, this has changed in recent years.Footnote54 Other aspects may hinder CRSV even being reported: the reputation, and sometimes practice, of peacekeeping personnel to commit sexual offences themselvesFootnote55; the tradition in certain communities to shame survivors of sexual violence rather than perpetratorsFootnote56; the risk of reprisal following reporting,Footnote57 all reduce the likelihood that CRSV becomes recorded. The hesitation or inability to report (which varies across contexts) represents a fundamental challenge to peacekeeping operations and practitioners in the field. It complicates our understanding of its prevalence, in particular across cases and over time, which in turn puts boundaries on possible research and reachable conclusions. The scarcity of data is notably also a consequence of the previously low interest in CRSV, and the assumption that CRSV is an inevitable side effect of any war.

Until now, cross-national research on CRSV has relied on one data collection covering CRSV worldwide 1989–2015: Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict (SVAC).Footnote58 Drawing on reports from the US State Department, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, SVAC holds a collection of yearly prevalence estimates for every warring party during conflict and five years thereafter.

Based on these data, researchers have begun to investigate the impact of peacekeeping operations on CRSV. Judging by the outcome of all UN peace operations deployed 1989–2009, peacekeepers do not mitigate CRSV very well. Using a global sample, Johansson and HultmanFootnote59 (hereafter referred to as the ‘global’ sample) find on average no reduction in state-perpetrated CRSV the year after peacekeeping operations deployment. Importantly, this non-finding does not hold true across all cases of CRSV and all types of peacekeeping operations.Footnote60 In a subset of conflicts in Africa during the same time period, Kirschner and Miller (hereafter referred to as the ‘African’ sample) do find a dampening effect of peacekeeping operations on CRSV perpetrated by state forces as well as rebel groups.Footnote61 In what follows, I review the findings of both these studies in relation to peacekeeping operations characteristics and armed groups’ command structures. While the latter is beyond the control of peacekeeping operations, it still gives valuable insights into why the challenge to mitigate CRSV is difficult and when extra and/or different resources need to be invested.

Beginning with peacekeeping operations characteristics, the global sample finds that the number of personnel is particularly important in relation to CRSV as it sometimes takes place in remote and more private spaces than violence intended for a wider audience. Also crucial is a mandate focused on civilian protection. In a conflict where CRSV is frequent, the risk of continuously high levels of sexual violence by rebel groups decreases substantially the year after a sizable police contingent mandated to protect civilians has been deployed. Without protection-mandate, the risk of rebel-perpetrated CRSV instead increases.Footnote62 In the study of African conflicts, which does not differentiate between protection mandates and other mandates, the authors instead find a reducing effect of police contingents on CRSV by state forces.Footnote63 The findings also diverge in relation to military contingents. In the global sample, there is no discernible impact of military peacekeeping personnel, suggesting that prevention of CRSV to a large degree hinges upon UN police.Footnote64 The African sample leads to a different conclusion as the authors find a mitigating effect of military peacekeeping personnel on CRSV by both state forces and rebel groups.Footnote65 The same study argues for the pacifying effect of civilian contingents. While the knowledge about this impact is limited, it remains an important avenue for future research. Overall, more research is needed to teas out why these studies differ in outcome. Possibly, they reflect heterogeneity across geographical regions. In addition, they highlight a sensitivity of the analyses to different modelling choices including whether or not to single out protection mandates, what time lags to use as well as how to deal with the non-random deployment of peacekeeping personnel. In addition, they point to the crudity of current measurements in quantitative research. To better understand when peacekeeping operations succeed in improving the situation on the ground, we would need more detailed information on both the specific undertakings of various peacekeeping contingents at different points in time, across different territories, and periodical reports of CRSV with more precise information about location and timing than conflict-year. To strengthen the external validity of our measurements and models, stronger partnerships between researchers (qualitative and quantitative), policy-makers and practitioners is needed.

The success of current peacekeeping operations is not only a product of composition and mandate. It is also a matter of the degree to which an armed actor exercises central command over its forces. While the international spotlight that follows from a large international operation expectedly has the power to impact warring parties’ political will, their actual capacity to act upon it lay more in how the armed group functions and is organized. In an organization such as the Integrated Armed Forces in the Democratic Republic of Congo (FARDC) where the relationship between the leadership and the rank-and-file soldiers has been characterized by disdain and broken promises,Footnote66 we cannot expect adjustments in the incentive structure at the top leadership to leave much of a footprint at lower levels of the echelons, at least not in the short term.

Based on rough measures of control, there is statistical evidence in support of this notion: While military contingents on average do not leave a measurable impact on CRSV in the global sample, they do indeed have a substantive, violence-reducing effect on those warring parties that exercise control over their forces.Footnote67 While centralized groups also commit CRSV,Footnote68 there is a substantial proportion of perpetrating forces lacking such command. Indeed, recent researchFootnote69 shows that rebel group fragmentation often correlates with CRSV which further speaks to the importance of developing alternative strategies to make peacekeeping operations better equipped to gain control over CRSV by decentralized or fragmenting groups. From a research perspective, more precise measures of control as well as in-depth case studies are needed to better nail down the processes through which the effects of peacekeeping operations resonate (or not) throughout the line of command. It will also be important to examine how other types of group characteristics, such as within-group prohibitions, influence peacekeeping operation effectiveness in curbing CRSV.Footnote70

Until now I have discussed the impact of peacekeeping in terms of increases or decreases in reported prevalence levels of CRSV, but peacekeeping has additional implications for CRSV through other pathways. Recent studies have found that CRSV makes women more likely to collectively mobilizeFootnote71 and pushes warring parties to the negotiation table.Footnote72 The importance of women’s ability to mobilize is demonstrated in yet another study, which finds that CRSV by rebels makes negotiated settlements more likely only in societies where women’s voices are acknowledged in the public sphere.Footnote73 Thus, to increase the probability that negotiation efforts are successful, UN police contingents play an important role to help create a safe environment for nonviolent mobilization where survivors’ voices can be heard.Footnote74 Needless to say, conflict settlements are key to long-term elimination of CRSV.

Lastly, I turn to the policy expectation that peacekeeping operations with female peacekeeping personnel are better equipped to deal with CRSV.Footnote75 According to the UN, women are critical in all types of positions (civilian as well as uniformed).Footnote76 Indeed, women expectedly widen the overall skillset, are more approachable to local women and ‘act as role models’Footnote77 in any capacity. While research has corroborated the positive impact of diversity in terms of cultural background of peacekeeping personnel,Footnote78 there is no published cross-national study testing the impact of gender diversity specifically.Footnote79 There are at least two reasons for why such a study is difficult to conduct: (1) female peacekeeping personnel is less likely to be deployed to areas suffering from CRSV than other areasFootnote80 (which induces selection bias); (2) a study of Liberia describes how female personnel deployed to high-risk conflicts rarely leave the compound and actually meet civiliansFootnote81 (requiring research to use fine-grained information seldom accessible to comparative scholars). These obstacles aside, the aspiration rests on a biased yet common understanding of CRSV only affecting women.Footnote82 Even if female personnel were successful in reaching local women, this could never be more than a partial solution considering that CRSV against men would remain unaddressed.

Conclusions

There are strong theoretical reasons to believe that CRSV requires specific considerations when designing peacekeeping operations. Initial studies of the average effect of peacekeeping operations on CRSV are inconclusive, suggesting that the impact differ depending on various factors such as peacekeeping mandate and command structure of armed groups. Some empirical evidence suggests that police contingents may have a particularly important role to play. Similarly, there are theoretical reasons to expect that diverse operations (in terms of gender and cultural background of personnel) would be more effective but this is not yet supported by statistical evidence. Partnerships where unique insights from policy, practitioners and researchers are used to extend and improve our current measurements and data collections would have the capacity to further teas out how peacekeeping operations most effectively could prevent CRSV.

The Evolving United Nations Approach to Preventing and Addressing Conflict-Related Sexual Violence: Experiences from the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Walter Lotze

Mason Fellow for the Mid-Career Masters in Public Administration Programme with the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

For more than a decade, the United Nations (UN) has been increasingly concerned by acts of sexual violence when used as a tactic of war or terrorism, and when systematically used to target civilians, both because this targeting of the civilian population exacerbates conflict, and because it hinders the restoration of international peace and security (see Johansson this Forum). The Security Council has therefore increasingly mandated UN presences in conflict and post-conflict areas to work both to prevent and respond to the use of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV). The efforts of UN peace operations have become central to these efforts, and the work which has been undertaken in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), first through MONUCFootnote83 and later MONUSCO,Footnote84 has perhaps been most formative for the organization in this regard. This commentary builds on research and personal views, in part arising from my experience as Head of Office of the Office of the UN’s Special Representative of the Secretary General in the DRC (January 2017 – June 2019) and Deputy Chief of Staff of MONUSCO (August 2016–January 2017).

The role of UN peace operations in Addressing CRSV

Over the years, the UN has worked to prevent and address CRSV in conflict and post-conflict settings across the globe. The bulk of these efforts have taken place in zones of conflict or instability, including Afghanistan, the Central African Republic, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Libya, Mali, Myanmar, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Yemen. Yet the organization has also worked to address sexual violence crimes in post-conflict settings, such as in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Côte d’Ivoire, Nepal and Sri Lanka, and monitors situations of concern, such as in Burundi and Nigeria.Footnote85The work of peace operations has been given particular attention in recent years. By the end of 2018, five UN peace operations (in the Central African Republic, Darfur, the DRC, Mali, and South Sudan) and two UN special political missions (in Afghanistan and Somalia) had been mandated to address CRSV. When issuing mandates, the Security Council has specifically tasked these operations to establish the required Monitoring, Analysis, and Reporting Arrangements (MARA), to engage with parties to secure time-bound commitments to end CRSV, to support parties to implement these commitments, and to support Security Sector Reform (SSR) efforts to build capacity to address this form of violence.Footnote86 By 2018, all peacekeeping operations with protection of civilians mandates had also established monitoring arrangements and incorporated early warning indicators for CRSV into their protection structures.Footnote87

The role of the Women Protection Advisors (WPAs) has proven important. Tasked with ensuring that the CRSV aspects of mandates are implemented, and are regularly reported on, by 2019, 21 WPAs were working in peace operations.Footnote88 Whereas such individuals previously worked alongside the human rights components, in recent years these functions have been integrated, with WPAs now reporting directly to the heads of human rights components. Efforts that were previously viewed as complementary were thus better recognized as being integral to one another. Today, WPAs work with the senior mission leadership to mainstream conflict-related sexual violence considerations into various aspects of mandate implementation; coordinate the monitoring and reporting arrangements; ensure regular reporting to the Security Council; engage with parties to the conflict to secure commitments to end violations, and support parties to implement these commitments; and work to strengthen capacities of national actors and all stakeholders to prevent and address conflict-related sexual violence.Footnote89 It is in the DRC that the work of UN peace operations has perhaps been most formative to how UN peace operations work to prevent and address conflict-related sexual violence.

Partnering in Support of National Efforts

In late 2008, the United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC) was mandated to support the Forces Armeés de la RDC (FARDC) in their operations against armed groups, as a way of enhancing the protection of the civilian population. The challenge was that Congolese armed forces were not fully adhering to international humanitarian law and human rights law when conducting these operations, and violations of the civilian population, including the use of sexual violence, were being recorded. In response, MONUC developed a two-tracked approach. First, a conditionality policy was developed, which stipulated that elements of the armed forces which committed violations against the civilian population would not be eligible for UN support. This would later serve as the foundation for the United Nations Human Rights Due Diligence Policy, applied globally wherever the UN provides support to state security actors or other parties. Second, the mission started to provide assistance to the military justice system, supporting the Congolese government in the fight against impunity. Here, priority would be placed on high-ranking military officers, to demonstrate that where abuses were committed, justice would be served, no matter the rank. The approach was new, as until that time the UN had been hesitant to support national military justice systems.Footnote90 Key to this evolving thinking was that survivors of CRSV often risk being violated twice; once through the violent acts which are committed against them, and again by the reactions, or the lack thereof, by the state and society.

The Government of the DRC and the UN thus started working hand in hand in the fight against armed groups, the protection of civilians, the fight against impunity, and the rule of law. Combatting CRSV and violations against children featured strongly in this two-tracked approach. Three key areas of engagement were identified, namely the fight against impunity, judicial reform, and establishing functioning justice institutions and prisons in areas affected by armed conflict. The initial prioritization of emblematic cases of war crimes and crimes against humanity in three provinces most affected by conflict helped to establish precedents.Footnote91 Some high-level cases have attracted most of the attention at global level in recent years, yet it is also important to note that on an almost annual basis FARDC officers have been tried for, and convicted of war crimes or crimes against humanity for rape and sexual violence. Indeed, it has been remarked that as efforts have progressed, military justice officers have often displayed greater rigour in investigations, in upholding fair trial principles in proceedings, and in implementing measures to protect victims and witnesses. Some Congolese authorities have also indicated that the threat of prosecution is the only credible deterrent to the commission of crimes within the FARDC and Police National Congolaise (PNC) ranks.Footnote92 The first-ever UN Comprehensive Strategy against Sexual Violence in Conflict was then developed in the DRC, which the Government endorsed through its zero-tolerance policy and included in its own gender-based violence National Strategy.

With time, these efforts started to show real results. Whereas before, rape was being used by state security forces as a weapon of war, in recent years this slowly stopped being the case. Although security forces did still commit acts of sexual violence, this was increasingly done in an opportunistic manner, rather than being organized at command level. In 2012, still around half of the recorded violations were attributed to the FARDC and the PNC.Footnote93 By 2014, a significant change had been recorded, and for the first time since reporting began, less than half of the reported cases of sexual violence were attributed to Congolese security forces.Footnote94 These efforts were reinforced and given executive level attention when President Joseph Kabila established an advisory role in his office on sexual violence and child recruitment in July 2014. In her new role, the Presidential Advisor placed the fight against impunity and providing better support to victims at the very centre of her efforts. That same year, the FARDC launched its first Action Plan against sexual violence, and a National Commission was established to oversee its implementation.

Overall, the number of recorded violations on the part of state actors has continued to decrease over the years, with most violations committed by non-state armed actors since 2014. Between 2017 and 2019 some worrying trends did emerge, when a rise in recorded violations on the part of the FARDC and the PNC was observed, as the country experienced political tensions. Of concern was that violations were being committed in new areas by armed groups (the Kamuina Nsapu and Bana Mura groups in the Kasai region), but also by the FARDC deploying in the same areas, and a significant rise in sexual assault by the PNC of persons in police custody was observed.

Cooperation continued nevertheless, and by early 2018, joint efforts had resulted in the prosecution of over 1200 accused, of whom 963 had been convicted, including senior elements of the FARDC, armed groups and a provincial parliamentary deputy.Footnote95 Importantly, between 2016 and 2018 316 military field commanders signed undertakings to prevent and address sexual violence, and 570 commanders were trained on their legal obligations.Footnote96 In this period, the UN also documented 159 convictions of members of the state security forces for sexual violence crimes. Verdicts were also handed down to members of numerous armed groups during this period, highlighting that justice was served to both state and non-state actors who committed violations.

Partnership has remained key to progress throughout. The Ministry of Justice and Human Rights and military judicial authorities, supported by the UN Team of Experts, the United Nations Development Programme, MONUSCO and the International Centre for Transitional Justice, have continued to work to prioritize the most grave cases for prosecution. The United Nations Children’s Fund has also worked to support victims, through the provision of medical, psychosocial, legal and socio-economic support to survivors of rape by combatants. Challenges remain, and reaching all victims and being able to provide the same level of support to those who may need it cannot always be assured. This is particularly so when it comes to providing access to post-exposure prophylaxis, treatment for sexually transmitted diseases, and the provision of mental health support. To address some of these and other challenges, the Government in 2016 developed a three-year roadmap (2017–2019) of national priorities to further advance progress in this regard, which is supported by the UN.Footnote97

In early 2018, with the support of MONUSCO, the national police developed an action plan against sexual violence.Footnote98 Later that same year, the DRC launched its second National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security (2019–2022), which contains core elements of work to eliminate impunity for sexual violence.

Having higher number of women peacekeepers has also played a key role. By early 2019, MONUSCO had over 3% of its military component and over 12% of its police component staffed by women. While these numbers may seem low, their impact has been profound. Women officers take part in patrols, visit detention facilities, form part of all-Female Engagement Teams (FETs), and undertake special missions. Women serve both to strengthen engagement by the mission with communities, and with state security actors. Women Protection Advisors also continue to engage with newly deployed FARDC and PNC personnel, provide training, sensitize state security actors and non-state armed actors alike, and work to reinforce local early warning and protection mechanisms (see also Johansson, in this Forum).

Consolidating Efforts: Implications for UN Peacekeeping

The UN approach to preventing and addressing CRSV in the DRC has thus evolved significantly over the years. Similarly, the experiences and lessons of other contexts is shaping the direction which the Security Council sets, and how the UN will implement these efforts going forward. Two key recent developments are indicative of this.

First, since 2017 the Secretary-General has taken numerous measures to improve the way the organization responds to sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) by UN personnel and those deployed under its banner. This involves placing victims’ rights at the centre of response mechanisms, re-doubling efforts to end impunity, and working with Member States to better detect, control and prevent incidents of SEA within the context of a zero-tolerance framework. Leading by example is essential, if the UN is seen to be a credible partner in the fight against sexual violence (see Ruffa and Hoover Green in this Forum for a discussion).

Second, drawing on the formative experiences in the DRC and from across its work in other countries, the UN in 2018 started work to develop its first comprehensive set of guidance on preventing and responding to CRSV through UN peace operations.

The policy would do three key things. First, it outlines the six guiding principles which should govern all efforts in relation to preventing and responding to CRSV – do no harm; confidentiality of victims and families; informed consent by all those cooperating with the UN; the use of a gender-sensitivity; maintaining a victim-centred approach; and protecting and promoting the best interests of the child where applicable. Second, it outlines the five priority objectives of UN peace operations in relation to addressing conflict-related sexual violence – the prevention of such acts and the protection of populations vulnerable to them; ending impunity; raising awareness of such acts, and condemning them where they occur; strengthening the capacity of national actors to address conflict-related sexual violence; and empowering victims through political process and referring them for support where possible.Footnote99 Third, the policy offers specific guidance on roles and responsibilities in field operations, and how the conflict-related sexual violence mandates are to be implemented in a comprehensive manner with a range of stakeholders.Footnote100

Conclusions

While progress is being made in terms internal policy consolidation, and measures are being undertaken to reinforce delivery on the ground, attention will also need to be paid to a few dynamics going forward. First, the importance of partnerships with national security actors should be further emphasized. The UN is most effective when it is working in support of national efforts, and reinforcing these. Second, the provision of support to justice systems, both military and civilian, has been a key to success, and is the best means of ensuring that the gains made can be sustained in the long term. Investing in justice for victims is also an investment in sustainable peace. Yet investments in this area have been varied. Third, the risks of not properly applying the Human Rights Due Diligence Policy are high, and this should not be compromised. However, the risks of not engaging at all with actors who commit violations are even higher. The policy should be applied to manage the risks of violations in the best manner possible, but it should not become a reason to not engage at all. Fourth, reparations for victims matter, both symbolically and materially where lives and where livelihoods have been impacted. In some cases courts award damages, but this is not always the case. Working to ensure uniformity of approach would go a long way towards the equitable administration of justice. Fifth, while reporting has improved in recent years following the establishment of dedicated reporting mechanisms, the deployment of the WPAs and the mainstreaming of reporting on CRSV, barriers to reporting remain. Peace operations generally report lower numbers of violations than other UN actors (like the United Nations Population Fund – UNFPA, or UNICEF). It is therefore often difficult to know the true extent of the violations, and where the most support may be needed. And sixth, a deeper understanding of vulnerability may be required. Although it is recognized that CRSV is not solely a women’s issue as men and boys are both victims of and deeply affected by such violations, for male survivors, sexual violence remains shrouded in cultural taboos. In 2018, in over 60 countries no provisions for male victims existed within the scope of national sexual violence legislation, leaving male and boy victims particularly vulnerable to accusations of homosexuality, in particular in countries where this is criminalized. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex individuals who are victims of violations are often vulnerable to stigmatization, exclusion or criminal persecution if they come forward.Footnote101

The UN has made significant progress on preventing and addressing CRSV in a very short span of time. In the course of just over a decade, the issue has been placed at the centre of Security Council deliberations, an organizational architecture has been developed, peace operations have been provided with increasingly strong mandates to focus on this, and Women Protection Advisors have been deployed to all major peace operations to both drive and consolidate these efforts. And significant progress has been attained, such as in the DRC. Yet as conflicts continue to evolve, so too the complexity of the challenge has evolved, and in turn the UN’s approach must continue to be built and shaped. Consolidating the gains made to date, and building on these for the future, will be key for the Security Council’s call to bring a total halt to CRSV to be fully realized.

Peacekeeping Military Contingents in Preventing CRSV by Local State Forces

Chiara Ruffa

Uppsala University/Swedish Defence University

Research findings on whether or not military peacekeeping contingents can prevent conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) perpetrated by local state forces are contradictory and inconclusive (see Johansson, this Forum).Footnote102 This lack of knowledge is highly problematic as local state forces constitute the largest group of perpetrators. When addressing this knowledge gap, I argue that we can improve prevention if we explore the role of two core traits that military peacekeeping contingents bring along when they deploy to an operation – military culture and self-understanding of professionalism – and how these are transferred to the local state security forces. By borrowing analytical tools from the field of security studies, this commentary contributes to this enhanced understanding and thereby also outlines how military peacekeeping contingents can further develop the capacity to become credible interlocutors when supporting the prevention of CRSV.

While a wealth of literature has explored sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) perpetrated by peacekeeping personnel (see Hoover Green in this Forum), no study has so far explored the effect of culture and self-understanding of professionalism that military peacekeeping contingents may have on the perpetration of sexual violence by local actors.Footnote103 My argument for why these are central for prevention is presented in three steps. First, I outline how the military culture and the self-understanding of professionalism in military peacekeeping contingents may harbour ideas that affect the prioritization of CRSV and which include a set of gendered conditions that can tolerate sexual violence and abuse. If the peacekeeping contingent has issues of this kind, it is less probable to prevent CRSV and may even contribute to harm. Second, once peacekeeping contingents deploy, their culture and ideas of professionalism are likely to be imitated by local state forces. We need to understand how these play into prevention. Third, and relatedly, we need to understand that the norm of prevention is more likely to transfer from peacekeeping contingents to local state forces via informal learning rather than formal programs.Footnote104 In discussing these arguments, I further relate them to understandings of military responsibilities and capacity. After discussing the arguments, I outline opportunities of addressing the problems and transferring more preventing norms of CRSV to local security forces given the internal dynamics of the military peacekeeping contingents themselves. I conclude by outlining ways ahead for future research and policy.

Military Contingents’ Traits and the Prevention of CRSV

I argue that we need to consider the state military organizations which are deployed to peacekeeping operations as organizations with special traits. Fundamental to this consideration is the fact that preventing CRSV has never been a core concern nor a core task of state military training and norms. At present, across the spectrum, military organizations still hold combat as their clear core task and conflate ‘masculinity with idealized traits of the warrior’.Footnote105 When they deploy, they tend to fall back into those core operational tasks. This entails that we need to start from the expectation that the understanding of CRSV, the sense of responsibility for preventing it, as well as the practical capacity to have an impact, are all likely to be low among many military peacekeeping contingents when they are deployed. To make matters worse, I argue, some military organizations implicitly seem to tolerate sexual violence which can make a military peacekeeping contingent a potential problem in and by itself. Before a military peacekeeping contingent can become effective at preventing CRSV, they therefore need to consider the roles that their own military culture and professional understanding of responsibility play, and the adherent capacity issues which follows from these.

Let us start by looking closer at these traits on culture and profession. Often depicted as ‘total’ or ‘greedy’ institutions, the military profession requires high levels of commitment and embracement of a collective identity.Footnote106 Key in this respect is military culture, ‘the set of beliefs, attitudes, norms and values that become deeply embedded and profoundly ingrained within a military unit and that guide the way the unit manages its internal and external life, the way it interprets its tactical and operational objectives and the way it learns and adapts to external influences’.Footnote107 Research finds that state militaries and their culture are also ‘inherently gendered’ and male-dominated, rooted in the idea that war should be fought by men.Footnote108 Few militaries in the world allow women to serve in any role, and many perform notably poorly at retaining women. When women deploy in peacekeeping operations, Karim and Beardsley showed that female peacekeeping personnel are often relegated to safe spacesFootnote109 and King demonstrated that in the large boots-on-the-ground operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, female personnel has taken great risks but has not ben awarded as much as male personnel in terms of carrier progression. To make it worse, they have often boxed women in ancillary care roles.Footnote110

While military organizations have changed substantially over the past thirty years, they retain some of the above characteristics. Notably, most state military organizations struggle to prevent sexual violence and assault even within their own ranks. In the US, ‘between 9.5% and 33% of women report experiencing an attempted or complete rape while serving in the military’ and ‘male victims are reported between 1% and 12%’.Footnote111 If an organization with such a problem deploy contingents to a peacekeeping operation, this may logically hamper a military’s ability to transfer a norm on preventing CRSV in its interaction with local state forces, worsened by the fact that such behaviour may continue to take place during deployment. Some literature even suggests that the experience of deployment, the long period out-of-area may make problems of sexual violence and assault even worse.Footnote112 In any case, the presence or persistence of sexual violence, assault and abuse would profoundly delegitimize the contingent but also open a space of reflection of unsolved problems.

These issues thereby have potential practical implications when a contingent is deployed. Research suggests that peacekeeping personnel act as role models for the local population, including members of security sector institutions, just by routine interactions. Arguably, these dynamics should be enhanced if peacekeeping personnel takes on the roles of monitors and trainers of local security forces and/or undertake joint operations. If peacekeeping contingents then fall back into those core operational tasks of combat where preventing sexual violence is not considered as a priority, this implies signalling to the local forces that CRSV is not important. This signal is even stronger if tasks in the peacekeeping mandate on CRSV are not implemented at all. While in recent years, military organizations have started to adapt to more complex peacekeeping tasks – ranging from the delivery of humanitarian aid to reconstruction – internal promotion logics and dynamics in military organizations persist.Footnote113 This unfortunate structural problem hence have additional perverse consequences for the ability of soldiers to implement important components of peacekeeping mandates such as the prevention of CRSV.

That said, the issues with organizational culture and ideas of professional responsibilities discussed above are neither a necessity – some military organization may prioritize prevention – nor a justification. Recent trends within the field of war studies suggests that military culture varies profoundly across military organizations and that it may shape norms, behaviour, and indirectly misconduct, in different ways. While some organizations cannot prioritize restraint, others have been more successful in doing so.Footnote114 Importantly, this means that military culture is not an inherently toxic driver of behaviour, it is changeable and should be deprived of its gendered and toxic masculinity nature to help prevent sexual violence. This suggests that while preventing CRSV might not have been a priority thus far, there is potential for unpacking important variations across state militaries in terms of propensity to support local security actors in preventing sexual violence. The first condition, however, for norm transfer to happen is to have a well-established norm punishing sexual abuse, assault and violence within the contingent that deploys to the peacekeeping mission.

How Peacekeeping Contingents Could Transfer a Prevention Norm

While previous research has identified the UN as an international norm entrepreneur,Footnote115 I argue that one of its most important components – the military contingents deployed – could and do act as a ‘norm transfer entrepreneur’. In this section, I outline two main channels that could help military peacekeeping personnel address existing internal problems and transfer a set of norms that could contribute to the prevention of CRSV to local security actors.Footnote116