ABSTRACT

Why is the implementation of civil war peace agreements comparatively higher in some countries than in other countries? In this study, I address this puzzle by investigating the effects of insider-outsider leader turnover on the execution of peace agreements. The idea is that leaders should be the fundamental units of analysis to explain the implementation of peace agreements due to more frequent leadership changes than state-level variables, such as the level of democracy, political system, military capability, and GDP per capita. Besides, leader turnover poses a commitment problem in peace processes if outsider leaders differ in their resolve and revise inherited agreements. I test this hypothesis quantitatively using feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) regressions to analyze the panel dataset of this research that covers 34 comprehensive peace agreements of 31 countries from 1989 to 2015. The findings of this study demonstrate the positive impacts of insider leader turnover and the adverse effects of outsider leader turnover on the execution of peace agreements. Hence, whether the implementation of peace agreements will continue depends on who comes to power.

Introduction

Does it matter who leads countries that are in the transition from war to peace? The willingness of a government to use force depends on who is in power. Leaders’ cost–benefit analysis and risk-taking behaviour decide between war and peace.Footnote1 Wolford argues that leaders instead of states should be the fundamental unit of analysis in studying international conflicts and civil wars.Footnote2 Similarly, Uzonyi and Wells assert that the leader-centric approach to studying civil war is more appropriate than the state-centric approach since leaders can hinder or facilitate the bargaining process and peace negotiations.Footnote3 The successive leaders might differ in their resolve and revise inherited peace agreements. Besides, leadership changes more frequently than state-level variables, such as political system and military capability.Footnote4 Hence, the study of conflicts and peace processes will be incomplete without analyzing the role of political leaders.Footnote5

Leader turnover is an emerging field of study in international conflict and civil war studies.Footnote6 In the recent past, scholars of comparative politics, international political economy, alliance formation, foreign policy, and international conflicts have focused on individual leaders.Footnote7 While few scholars, such as Ryckman and BraithwaiteFootnote8 and Croco,Footnote9 have studied the effects of leader turnover on peace negotiation and settlement, no study has examined the impacts of leader turnover on the performance of peace agreements. Earlier research has concentrated mainly on peace negotiation but less on the implementation of peace agreements.Footnote10 In this study, I examine the association between leader turnover and the implementation of peace agreements to address this research gap.

Analyzing the panel dataset of this study, I find insider leader turnover's positive and statistically significant influence on the implementation of peace agreements. In contrast, the performance of peace agreements decreases following an outsider leader assuming office. The findings of this study align with existing researchFootnote11 that insider leaders can advance the peace process due to their prior knowledge about earlier peace attempts and the status of the current peace process. Besides, insider leaders continue the policy of their predecessors to maintain the party's reputation, which is vital to winning in the next elections.Footnote12

Conversely, outsider leader turnover, considered the shift of policy preferences,Footnote13 can decline the implementation of peace agreements for several reasons. First, outsider leaders might have different political preferences and alternative interpretations of the same issue.Footnote14 Second, they might revise inherited policies since they come to power with the support of different electoral bases.Footnote15 Third, an information gap might exist about the intentions of new leaders on the rebel side.Footnote16 Fourth, outsider leaders might lack information and understanding about the peace process of the preceding government.Footnote17

The findings of the study will make an original contribution to civil war studies in three distinct ways. First, this research integrates international relations theories with the civil war studies literature to explain how leader turnover influences the implementation of peace agreements. Second, it explores the impacts of leader turnovers within signatory parties of a peace agreement, which is unknown in the existing literature. Third, the discussion of the effects of insider-outsider leader turnover is limited to peace negotiation and settlement. This study extends the debate by examining insider-outsider leader turnover effects on the execution of civil war peace agreements.

This study might offer fresh insight into the discourse of international peacebuilding operations, which seek to prevent the recurrence of violence in countries that have emerged from civil wars. Since 1989, the United Nations, the World Bank, the Organization of American States (OAS), the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the US Agency for International Development (USAID), and other international organizations have engaged in peacebuilding missions in many countries such as Cambodia, El Salvador, and the former Yugoslavia. However, many international peacebuilding missions have failed to produce the intended outcome.Footnote18 Why? Multiple answers to this question might exist, but this study suggests that an unlikely leader might thwart the implementation of peace agreements. Hence, this research suggests international peacebuilding actors focus on leader turnover trap – who comes to power – following the signing of peace agreements to prevent the recurrence of conflict.

The article proceeds as follows. The first section introduces the research puzzle of this study, while the second section reviews existing literature on how political leaders play a decisive role in civil war peace processes. The third section discusses the theoretical framework to develop the hypothesis of this study, whereas the fourth section explains the research design. The fifth section presents an empirical analysis based on statistical results, and the sixth section summarizes key findings and highlights implications of this study in theory and policy.

Political Leaders in Peace Processes

Does leader-centric politics offer a new research agenda in civil war studies? Put differently, do political leaders, as the influential actors, determine the course of peace processes? RoslerFootnote19 argues that political leaders perform multiple roles, from starting negotiations and signing peace agreements to making tough decisions on controversial issues like granting amnesty for rebels. Moreover, they mobilize their political parties and citizens to construct a shared future with their former enemies. Three bodies of scholarly literature – the personalization of politics thesis, leadership style, and the hawk-dove dichotomy – explain how political leadership plays a decisive role in peace processes.

The first stream of conflict negotiation literature is related to the personalization of the politics thesis. Political leaders hold government office, exercise power, and control decision-making in collective actions. Previous studies on political leadership are concentrated mainly on executive leadership exercised by heads of state.Footnote20 Executive leadership is founded upon the concept of personalization of politics. Leaders wield influence in appointing cabinets, public services, judiciary, and defense.Footnote21 Nowadays, political leaders fully control the day-to-day activities of their parties since they hold executive positions and excessive power. This fundamental political change demonstrates that individual political actors are more prominent at the expense of their political parties.Footnote22

Due to the rise of personalized politics, the importance of leader turnover has increased for civil war peace processes. Conflict negotiation literature indicates that political leaders in power represent a policy of recognition and even reconciliation to negotiate with the opponents to initiate a peace process. In contrast, they need to take a tough stance to maintain their political base, which is reluctant to accept the political concessions of the governments.Footnote23 For instance, Cristiani, who won the 1989 El Salvador presidential election, negotiated the Chapultepec Peace Accord (1992) that ended the decade-long brutal civil war, which culminated in the deaths of 75,000–100,000 people. As the government leader and big shot of his political party, he had been persuading members of his political party to coexist with the former combatants of the Farbundo Martí Liberation Front (FMLN) since the accord.Footnote24

The second stream of conflict negotiation literature is concerned with a pragmatic and reconciliation-oriented leadership style that is necessary to initiate peace negotiations successfully.Footnote25 Colombia, as an exemplary case, reveals that the leadership of President Santos was crucial for the 2016 peace agreement signed between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People’s Army (FARC) for two main reasons. First, Santos learned from the past mistakes of his predecessors and adopted a more pragmatic approach which made his leadership style different from his predecessors. He consulted top military Generals about his peace plan and neutralized two hard-liner Generals – Jorge Enrique Mora (former chief of the military) and Naranjo Trujillo (former head of the police) – by including them in the negotiation team.Footnote26 Besides, he established the tri-partite monitoring and verification system, which consisted of representatives from the government, the FARC, and the UN, to facilitate the disarmament and demobilization of former combatants.Footnote27

Second, he was trustworthy to the FARC due to his accommodative leadership style. He had a reputation with the FARC due to his neutral and respectful tone. He never used the term ‘terrorist’ for the FARC guerrillas and never blamed the FARC for previously failed peace processes. For this reason, he was an esteemed politician to the FARC for his pragmatist and reconciliation-oriented leadership style.Footnote28 In sum, his image and reconciliation-oriented leadership style made the 2012 Havana meeting successful in negotiating six aspects of the peace process: land redistribution, political participation of the FARC, reintegration of former guerrillas, drug trade, transitional justice and reparation of victims, and implementation of the accord.Footnote29

The third stream of conflict research literature concentrates on the hawk-dove dichotomy.Footnote30 Why are some leaders more likely to facilitate the peace process while others hinder it? For instance, Yitzhak Rabin in Israel and Juan Manuel Santos in Colombia signed peace agreements with their enemies. In contrast, several other leaders, like Benjamin Netanyahu in Israel and Iván Duque in Colombia, rejected peace agreements with their enemies in the same country.Footnote31 Why do leaders behave differently on the question of the same conflict? One of the explanations is that leaders may differ in their assessments of the cost of conflict since they hold different underlying beliefs as rational individuals and interpret the same political world from divergent perspectives.Footnote32 For instance, both Israeli leaders – Netanyahu and Peres – emphasized peace and security during their election campaign in 1996. However, their position on two issues – peace and security – fundamentally differed. While Netanyahu believed in establishing peace through security, Peres claimed that regional peace and stability could enhance security.Footnote33 The electoral victory of hawkish Netanyahu hindered the Oslo peace process due to his refusal to meet and discuss with Arafat as a partner for peace.Footnote34

The above discussion suggests that political leadership and leader turnover should receive more scholarly attention in the study of the implementation of peace agreements. The central argument is that substantial policy reversals occur when unlikely leaders come to the office.Footnote35 Following the leader turnover and policy change literature,Footnote36 I argue that the implementation of peace agreements depends on who comes to power. In the next section, I discuss the relationship between the type of leader turnover and the execution of peace agreements based on peace negotiation and settlement literature due to the lack of research on the implementation.

Leadership Changes and Peace Agreement Implementation

A scholarly line of investigation explains three significant benefits of leader changes for negotiating and settling civil wars. First, leader turnover helps overcome the problem of information updating, which is crucial to ending the conflict and initiating peace negotiations.Footnote37 Second, culpable leaders want to continue wars for their economic gain and the fear of punishment such as removal from office, imprisonment, exile, and death.Footnote38 New leaders with different personal preferences can change the previous government's position, facilitating negotiations and resolving conflicts.Footnote39 Third, new leaders might assume the office with a holistic interpretation of policy dilemmas and replace or sideline those key persons committed to old policies.Footnote40

However, another scholarly line of inquiry finds the adverse impacts of leader turnover on bargaining and commitment problem in three ways. First, personal background factors such as age, military experience, and educational qualifications can make a difference in the conflict behaviour of leaders. Second, the preferences of successive leaders of the same country might differ over war and peace from their predecessors. Third, successive leaders might not implement the policies they inherited since leaders are rational actors and assess the same political world from different underlying beliefs.Footnote41 Hence, leader turnover reflects the shift in policy choices of domestic governing coalitions. The preferences and support bases of newly elected leaders might differ from those of preceding leaders.Footnote42 Thus, leadership change impedes the likelihood of settlement since it creates a commitment problem toward the inherited policies.Footnote43

In brief, existing literature on the impacts of leader turnover in peace processes is ambiguous since one scholarly line of inquiry finds positive effects of leader turnover. In contrast, another line of investigation argues that a negative relationship exists between leader turnover and peace processes. Hence, a question remains about why leader turnover can influence peace processes negatively and positively. In this regard, Ryckman and BraithwaiteFootnote44 add that insider leaders are more likely to facilitate a peace process, while outsider leaders obstruct it.Footnote45

Why is insider leadership change beneficial for a peace process? Insider leaders can kick-start the peace process in several ways. First, they maintain the policy of their predecessors and facilitate peace processes. Second, they can overcome lags in the rational updating process by addressing information problems on relative military capability and concessions. Third, they are aware of earlier peace attempts and the current status of the peace agreement. Fourth, they can reduce the transaction costs of rebuilding relationships with rebels who understand incumbent leaders. Ryckman and BraithwaiteFootnote46 have conducted a large-N study to test these theoretical expectations quantitatively. They find that insider leadership changes are more likely to influence peace processes positively.

Outsider leaders can obstruct the peace process as shadow veto players since they come to power with different interests and support bases.Footnote47 For this reason, outsider leader turnover, defined as the shift in interests,Footnote48 reflects the change in policy choices of domestic governing coalitions.Footnote49 Besides, outsider leaders might revise inherited policies after they assume office because of their different personal backgrounds and underlying beliefs.Footnote50 Thus, they create a commitment problem that might undermine peace processes.Footnote51 In addition, they might lack information and understanding about the status of peace processes and the rebels’ demands. Furthermore, insurgents can be skeptical about the intentions of new leaders due to their lack of information about outsider leaders.Footnote52

The Philippines is an illustrative case of how outsider leader turnover influences the implementation of a peace agreement. Fidel Ramos, who won the 1992 presidential election, adopted a policy of accommodation and co-optation of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) guerrillas. He reopened peace talks with MNLF and signed the Mindanao Final Agreement (1996) with the rebels. Besides, he established the Southern Philippines Council for Peace and Development (SPCPD) and the Consultative Assembly to facilitate peace and development activities in the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). Moreover, he appointed the MNLF leader Misuari as the Chairman of the SPCPD after signing the 1996 peace agreement.Footnote53

After the Mindanao Final Agreement (1996), Joseph Estrada, an outsider leader of this agreement, came to power after winning the 1998 presidential election. The new government policy towards the execution of this agreement altered fundamentally. For instance, Estrada shut down the President’s Mindanao office, which Fidel Ramos established to get early warnings on Mindanao. Further, Estrada took a tough stance towards the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), leading to violence in the region with the deaths of civilians, looting, and inter-ethnic hostility. The government forces captured Camp Abubakar, the headquarters of the MILF, in July 2000. Salamat Hashim, the Chairman of the MILF, called on the Moro people to wage Jihad against the enemy of Islam.Footnote54

Gloria Macapagal Arroyo took office from the same electoral platform as Fidel Ramos in the 2001 presidential election. The implementation score of the agreement increased during the administration of Arroyo since she ended Estrada’s all-out-war strategy against the MILF and continued the policy of her predecessor Fidel Ramos in the early of her administration.Footnote55 Drawing on the illustrative case of the Philippines and earlier research on the benefits of insider leader changes and the adverse impacts of outsider leader turnovers, I develop the following hypothesis to test the effects of leader turnover on the implementation of peace agreements in democratic countries.

HYPOTHESIS (The effects of leader turnover): Insider leader turnover is more likely to increase the likelihood of implementing civil war peace agreements than outsider leader turnover.

Research Design

To investigate the effects of insider-outsider leader turnover on the execution of peace agreements, I use the Peace Accord Matrix (PAM) dataset,Footnote56 which covers 34 comprehensive peace agreements in 31 countries from 1989 to 2015, as a principal source of information on the dependent variable. I use two datasets – the Archigos dataset and the Change in Source of Leader Support (CHISOLS) datasetFootnote57 – for my independent variables. I also collect information on control variables from several existing datasets, such as the Polity dataset and World Development Indicators. The unit of analysis of this study is agreement-year, whereas I determine the temporal scope between 1989 and 2015 based on data availability. In the following sub-sections, I explain how I operationalize the dependent variable, independent variables, and control variables in this study.

Dependent Variable

Two main approaches to measuring the implementation of peace agreements exist in the literature. Pettersson, Högbladh, and ÖbergFootnote58 measure the implementation status of peace agreements on a binary scale in their UCDP Peace Agreement Dataset. However, methodologically, a binary approach cannot explain the variation in the implementation of peace agreements, potentially leading to the estimation of inefficient parameters. Apart from this limitation, the implementation is an incremental outcome instead of a binary outcome: implemented or not implemented.Footnote59

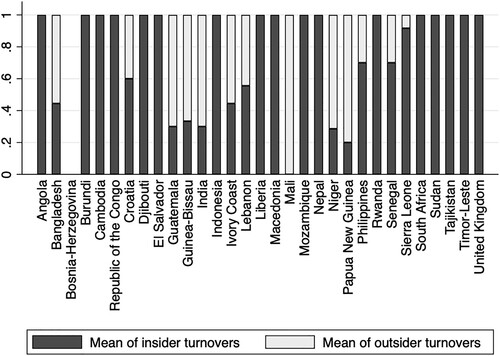

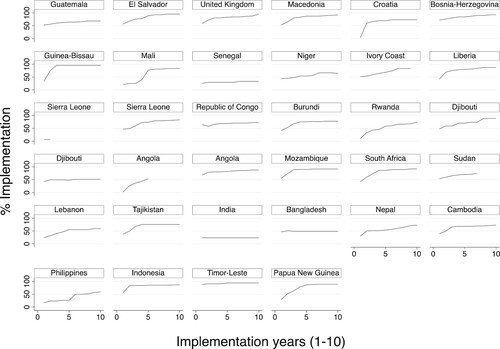

Hence, Joshi, Quinn, and ReganFootnote60 use a 4-point ordinal scale (0 = no implementation, 1 = minimal implementation, 2 = intermediate implementation, and 3 = full implementation) to measure the annual implementation rate of every peace agreement in their PAM dataset. They use the following formula to calculate the implementation rate of peace agreements: (actual implementation value/expected implementation value) x 100. It first sums up the actual implementation value of a peace agreement's provisions. Then it divides the sum by the expected value of a peace agreement's provisions. Finally, the outcome is multiplied by 100. In this study, I use this measure of implementation of peace agreements – IMPLEM – as the dependent variable (N = 323, Mean = 65.95, SD = 21.73). demonstrates the variation in the implementation rate of 34 peace agreements of 31 countries.

A question might arise about whether peace agreements with more provisions will achieve higher implementation scores than those with fewer provisions. The PAM dataset has standardized implementation scores to make them comparable given different lengths of peace agreements. Two hypothetical examples can explain this standardization process. Northern Ireland’s Good Friday Agreement (1998) contains 28 provisions, and the expected value for fully implementing 28 provisions would be [(28 × 3) = 84]. Let us assume that 7 provisions of this peace accord are coded minimal (1 point each), 7 provisions are coded intermediate (2 points each), and the remaining 14 provisions are coded full implementation (3 points each) after seven years of implementation. The actual value of the implementation would be [(7 × 1) + (7 × 2) + (14 × 3)] = 63. Then the implementation rate of this peace agreement would be (63/84) x 100 = 75%.

Let us consider another example – the Accord for a Firm and Lasting Peace of Guatemala (1996) – which has 32 provisions. The expected value for fully implementing 32 provisions would be [(32x 3) = 96]. Let us assume that 8 provisions of this peace accord are coded minimal, 8 provisions are coded intermediate, and the remaining 16 provisions are coded full implementation after five years of implementation. The actual implementation score would be [(8 × 1) + (8 × 2) + (16 × 3)] = 72. The implementation rate of this peace agreement would be (72/96) x 100 = 75%. These two hypothetical examples show that the implementation rate of both peace agreements – the Good Friday Agreement and the Accord for a Firm and Lasting Peace – is 75% despite the former having fewer provisions (28) than the latter (32). Hence, peace agreements with more provisions will not get higher scores than those with fewer provisions on a 100-point scale.

Independent Variables

The fundamental interest of this empirical research is to estimate the effects of leader turnover on the implementation of peace agreements. Ryckman and BraithwaiteFootnote61 have discussed two types of leader turnover – insider and outsider. They code insider turnover as a political situation when a new leader assumes office from within the existing regime. In contrast, they code outsider leader turnover if a new leader comes to power in a given year from outside the previous regime. They also use the Change in Source of Leader Support (CHISOLS) dataset,Footnote62 which code an outsider leadership change that brings a new governing coalition to power in a given year.

The coding procedures of Ryckman and Braithwaite and Mattes, Leeds, and Matsumura need to consider the direction of insider-outsider leadership change. They code leader turnover only for the year when leadership change occurred. I code leader turnover for every year by assigning the value of either 1 (insider turnover) or 0 (outsider turnover) due to my interest in the impact of the direction of the leadership changes on the implementation of peace agreements. Apart from this, some countries, such as Nepal and South Africa, have witnessed rebel leaderships come to power following the signing of peace agreements. According to Ryckman and Braithwaite and the CHISOLS dataset, these power transfers between signatories of the peace deal will be considered outsider leader turnovers.

However, my argument is that signatory parties will continue the implementation of peace agreements due to their commitment to the same policy agenda – the implementation of peace agreements – when they are in office. In contrast, non-signatory parties are not accountable to citizens for implementing the peace agreement when they run the government. Hence, I code 1 for insider leader turnover, when the transfer of power occurs in a country in a given year within the peace agreement's signatory parties. In contrast, I code 0 if a leader assumes office from an entirely new governing coalition and outsider parties of the peace agreements. shows country-wise insider-outsider leader turnovers of 31 countries in the first decade since the signing of peace agreements.

Why should we expect all signatories to be committed to implementing peace agreements? Prorok and CilFootnote63 argue that implementation is more likely when leaders publicly commit to peace. Because of the accountability of leaders, they cannot renege on their commitments even under conditions that make implementation costly and the spoiler risk high. They tested their expectations using a novel dataset on the performance of peace agreements between 1989 and 2014. Their findings suggest how leaders, who have made pro-peace public statements, affect the implementation of peace agreements. In line with Prorok and Cil,Footnote64 I theoretically expect that leaders, who had publicly committed to peace by signing peace agreements, are more likely to implement peace deals.

A question might arise about countries which witness multiple leader turnovers in the early year, mid- year, or after mid-year. Which leader should be the effective leader in this situation? The DPI codes the effective leader for partial years who was in power as of January 1 or was elected but had not taken office as of January 1. I have revised the coding procedure of the DPI by considering ‘long-served leaders’ as chief executives based on the assumption that long-tenured leaders might have comparatively more policy implications than short-tenured leaders. Following this simple coding procedure, I consider Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono as the chief executive of Indonesia for 2014, although Joko Widodo replaced him in the same year on October 20, 2014.

There was a coding difficulty in the case of Nepal when three leaders – Madhav Kumar Nepal, Nath Khanal, and Baburam Bhattrai – served as the chief executives in the year 2011. Nath Khanal was in power more than two other leaders. Then, I apply the coding procedure of leader turnover mentioned above and consider Nath Khanal as the chief executive for 2011. Similarly, I do not count Radmila Sekerinska, the chief executive of Macedonia, for her short-term acting prime ministership (12 May 2004–2 June 2004). I consider Hari Kostov the chief executive this year since he was comparatively the long-served leader.

Control Variables

I include several control variables in my empirical analysis to address rival explanations of the implementation of peace agreements. First, I construct a variable – YCOUNT – to control the temporal dependence of this study following the research of Joshi, Lee, and Ginty.Footnote65 Second, I construct a variable – LEADAGE – to control the effects of the age of leaders on the implementation of peace agreements in my empirical analysis since a substantial body of literature has examined the relationship between the conflict behaviour of leaders and their age. For instance, Horowitz, McDermott, and StamFootnote66 find that younger leaders adopt a more aggressive stance due to their higher testosterone level, as opposed to older leaders.

Second, there is a growing body of literature on women in peacebuilding that emphasizes the role of gender in conflict and peace processes. For instance, CharlesworthFootnote67 finds that women think and act differently and have distinct qualities to offer peacebuilding. They favour peace over conflict since they constitute one of the most vulnerable groups in conflict. Krause, Krause, and BränforsFootnote68 find a robust correlation between female signories of peace agreements and durable peace. Following this literature, I construct a dummy variable – GENDER – to control the effects of gender on the implementation of peace agreements. I code 1 for male and 0 otherwise.

Third, political leaders play a decisive role in initiating and terminating the war. While many political leaders favour wars and military victory, several other leaders prefer peace negotiations with the enemies during the war.Footnote69 What explains the variation in the conflict behaviour of leaders? Horowitz, McDermott, and StamFootnote70 find that the increase in the age of leaders is more likely to initiate and escalate militarized disputes. Hence, in my empirical analysis, I expect that the rise in the age of national leaders will decline in the implementation of peace agreements. I construct a continuous variable – LEADAGE – to control the effects of the age of political leaders on the performance of peace agreements.

Fourth, a substantial amount of literature explains how leaders’ tenure influences the war's outcome.Footnote71 Long-tenured leaders are more likely to terminate the conflictFootnote72 and overcome the government's commitment problem since rebels understand incumbent leaders.Footnote73 Hence, an increase in leaders’ tenure will positively influence the implementation of peace agreements. To control the effects of leader tenure on the performance in this study, I construct a continuous variable – LEADTEN – and operationalize it as the number of days a leader holds the office since they come to power.

Fifth, the likelihood of military coups increases following civil war peace agreements which threaten the interests of the military.Footnote74 Hence, I expect the implementation scores of peace agreements to be lower when military officers come to power. To account for the effects of the military background of leaders, I construct a dummy variable – MILITARY – by coding 1 for the military experience of leaders and 0 otherwise.

Sixth, intrastate conflicts are of two types – territorial and governmental – according to Pettersson, Högbladh, and Öberg.Footnote75 Territorial conflicts are more difficult to resolve through negotiations than governmental conflicts.Footnote76 Hence, I expect the implementation to be higher for government conflicts than territorial ones. Previous studies code 1 for the conflict over government and 0 for the conflict over territory.Footnote77 However, Harbom, Högbladh, and WallensteenFootnote78 code 1 if the incompatibility of the conflict is over the territory and 0 otherwise. To rule out the effects of the conflict type on the implementation of peace agreements, I construct a dichotomous variable – CONTYPE – following existing measures. I code 1 for governmental conflicts and 0 for territorial conflicts.

Seventh, RamziFootnote79 argues that conflicting parties do not accept compromise and negotiation to end the conflict peacefully when the conflict endures with increased costs of war. The longer the conflict lasts, the lower the implementation scores will be. To control the effects of conflict duration on the implementation, I construct – CONDUR– as a continuous variable that counts the number of days a conflict prolongs until conflicting parties sign a peace agreement. To meet the assumption of normal distribution, I use the log transformation of this control variable.

Eighth, existing literature has used battle deaths as a proxy measure for the costs of the war.Footnote80 The higher causality rate of previous civil wars determines the level of recruitment of rebels for a new rebellion. Costly wars might be less vulnerable to another round of civil war due to the lack of resources, the reluctance of soldiers, and the absence of public support.Footnote81 Hence, the implementation of peace agreements should be higher for costly wars. To control the effects of the cost of war on the performance of peace agreements, I construct a continuous variable – BDEATH – that counts the total number of people killed in the civil war until a peace agreement is signed.

Ninth, many civil wars with multiple rebel groups are difficult to solve since all the rebel groups might not be interested in peace negotiations.Footnote82 In contrast, peace is less likely to endure if all the rebel groups do not participate in the peace settlements.Footnote83 Hence, I construct a variable on the number of rebel groups – REBGRP – to control the effects of the number of active conflicting parties on the execution of peace agreements.

Tenth, a scholarly line of peace research focuses on three built-in safeguards of peace agreements – transitional power-sharing provisions, dispute resolution, and verification mechanisms. These three types of built-in safeguards can prevent the collapse of peace agreements and increase the execution of peace agreements by more than 47 percent. The idea is that verification mechanisms can establish transparency in gathering and circulating information on implementing peace agreements.Footnote84 To control the effects of verification mechanisms on the performance of peace agreements, I construct a dummy variable – VERPROV – by coding 1 for a peace agreement with verification provisions and 0 for a peace agreement without verification provisions based on information from the PAM dataset.

Eleventh, single-party majority governments are comparatively less constrained in policymaking than minority governments. By contrast, majority government leaders have fewer constraints than leaders of minority governments.Footnote85 Hence, I expect single-party governments to implement peace agreements more than multiparty governments due to comparatively fewer domestic institutional constraints. I construct a binary variable – GOVTYPE – based on the DPI, which provides information on three government parties to control the effects of government type on the implementation of peace agreements. I code 1 if a single party controls the government and 0 if two or more political parties control the government following the signing of a peace agreement.

Twelfth, infant mortality results from multiple factors, such as limited access to health care, clean water, nutrition, air quality, and the level of education.Footnote86 Previous studies have used informant mortality as the proxy measure of state capacity. For instance, in their study titled ‘State Capacity, Regime Type, and Sustaining the Peace after Civil War,’ Mason and GreigFootnote87 have controlled infant mortality's effects. Joshi, Melander, and Quinn,Footnote88 in their research titled ‘Sequencing the Peace: How the Order of Peace Agreement Implementation Can Reduce the Destabilizing Effects of Post-Accord Elections,’ have also used infant mortality to control state capacity.

Thirteenth, I control the level of electoral democracy in my empirical analysis since the election is a core element of democracy. According to the democratic civil peace thesis, elections can foster domestic peace by increasing inclusiveness and encouraging opposition parties to pursue their political interests non-violently.Footnote89 Notably, many peace agreements have included provisions concerned with post-conflict elections to establish peace by providing democratic space to dissidents. To control the effects of the level of electoral democracy on the implementation of peace agreements, I construct a continuous variable – EDINDEX. I use the electoral democracy measure of V-Dem, an aggregated index of freedom of association, clean and fair election, freedom of expression, elected officials, and suffrage on a scale of 0–1.Footnote90

Fourteenth, liberal democracy is beyond ‘the rule by the people’ due to its emphasis on the executives’ constraints, independence of the judiciary, protection of civil liberty, property rights and minority rights, and freedom of religion and media.Footnote91 International peacebuilding missions emphasized establishing liberal democracy and a market economy in conflict-affected countries such as Cambodia, El Salvador, Mozambique, Nicaragua, and Rwanda.Footnote92 To control the positive effects of liberal democracy on the implementation of peace agreements, I construct a continuous variable – LDINDEX – on a scale of 0–1 following the measure of the V-Dem.Footnote93

Fifteenth, the UN has brokered a dozen civil war peace agreements in many countries, for instance, El Salvador, Cambodia, Bosnia, and Guatemala, since 1989.Footnote94 The UN missions can strengthen weak political institutions such as the election commission and provide security without functional security forces in conflict-affected countries.Footnote95 Hence, I expect that the UN intervention will positively impact the implementation of peace agreements. To control the effects of UN intervention on the performance of peace agreements, I construct a dummy variable – POLMIS – from the Dataset of Maekawa, Arı, and Gizelis.Footnote96 I code 1 for the UN political mission in a country in a given year and 0 otherwise following the signing of a peace agreement ().

Table 1. Country-Wise Elections and Party Changes.

Results and Discussion

The PAM dataset is a time-series data and has serial autocorrelation. This implies that classical panel data models – pooled OLS, fixed-effects model, random-effects model, and linear mixed-effects model – will not be appropriate estimation techniques for this dataset. Joshi, Lee, and GintyFootnote97 used feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) regressions with a first-order autoregressive process or AR(1) to address serial correlation. To deal with the temporal dependence issue, they included the number of years that have passed in the implementation process. Since I use the same dataset to test the hypothesis of this study, I apply the FGLS models and include the temporal dependence variable in the empirical analysis in models 1–8 in .

Table 2. FGLS Regression Results of the Leader Turnover Effects on the Implementation.

The main difference in the FGLS models lies in selecting control variables. Model 1 includes only the leader turnover variable – LEADTURN – and the year of the implementation of peace agreements variable – YCOUNT – to control the temporal dependence of the implementation process of the peace agreements. Model 2 presents the empirical results of the relationship between the primary explanatory variable, LEADTURN, and the outcome variable, IMPLEM, controlling YCOUNT and leader-centric controls, such as GENDER, LEADAGE, LEADTEN, and MILITARY.

Models 3–6 include all the predictors of model 2, but models 3–6 provide deeper insights into leader turnover effects on the implementation of peace agreements in democratic versus non-democratic countries. Notably, several democracy measures, for instance, Polity IV and Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem), exist in the literature. To avoid sample selection bias, I use Polity and V- Dem polyarchy scores to conduct sub-sample analyses. A large volume of literatureFootnote98 in political science has used Polity scores to define political regimes on a 21-point scale: non-democracy (- 6–5) and democracy (6–10). Models 3–4 are confined to non-democratic and democratic countries on the Polity scores.

However, two components of the Polity Index – government restriction on political competition and the degree of regulation of political competition – exhibit a strong relationship with civil war, indicating potential endogeneity of the Polity Index with civil war.Footnote99 To address the sample selection procedure concern, I also use V-Dem polyarchy cut-off points to check whether any country which qualifies as a democracy is excluded from my sub-sample analyses. The scale of V-Dem polyarchy ranges from 0 to 1, with ≥ .05 as democracy.Footnote100 Only six countries – Guatemala, India, Indonesia, Philippines, Senegal, and the United Kingdom – qualify as democracies if I use the V-Dem polyarchy scores. Models 5–6 are limited to non-democratic versus democratic countries on V-Dem polyarchy scores. By contrast, models 7–8 are the full FGLS models that include all the predictors of this study except for EDINDEX and LDINDEX.

My theoretical expectation was that insider-outsider leader turnovers would significantly influence the implementation of peace agreements. The statistical results presented in models 1–8 support my theoretical expectation, indicating a positive influence of insider leader turnover on the implementation of peace agreements. The results are statistically significant at β = 4.27 and p < 0.01 (model 1), β = 5.06 and p < 0.01 (model 2), β = 14.89 and p < 0.001 (model 3), β = 26.09 and p < 0.001 (model 5), β = 3.37 and p < 0.05 (model 7), and β = 3.48 and p < 0.05 (model 8). In contrast, the results of model 4 (which is limited to non-democratic countries on Polity scores) and model 6 (which is confined to non-democratic countries on V-Dem polyarchy scores) are not statistically significant at p < 0.05, but they still show the positive impacts of insider leader turnovers on the execution of peace agreements. Notably, model 3 and model 5 demonstrate that insider leader turnovers are more likely to increase the implementation of peace agreements in democratic countries at p < 0.05.

Based on these statistical results, I argue that insider leader turnover is more likely to execute civil war peace agreements than outsider leader turnover. Overall, the results of this study align with existing research, which reveals the impacts of outsider leaders on policy discontinuity.Footnote101 The main idea is that outsider leaders obstruct the implementation of peace agreements as shadow veto players since they lack information about the peace process. Besides, their personal preferences and support bases differ from the preceding leaders.Footnote102

Several examples suggest that the implementation of peace agreements increases when the alternation of power remains within insider parties of peace agreements. For instance, the NP of South Africa signed the Interim Constitution Accord on 17 November 1993 with opposition parties. Although leader turnover occurred from De Klerk (NP) to Nelson Mandela (ANC) during the 1994 presidential election after this peace agreement, this leader turnover did not affect the implementation of this peace agreement since the successive leader was one of the signatories of this peace agreement. Similarly, Nepal and El Salvador are two case studies where rebel leaderships – the CPN-M and the FMLN – won national elections and formed the government. These cases suggest that insider parties of peace agreements, which made public commitments to peace, aware of the earlier peace attempts and the progress of peace processes, remained in power, and hence the implementation of peace agreements continued in these countries.Footnote103

The control variables in also offer insights into the determinants of implementing peace agreements in democratic countries. Among the control variables, YCOUNT has a positive and statistically significant influence on performance at p < 0.05. This result is in line with Joshi, Lee, and Ginty that the current peace agreement scores correlate with implementation scores of previous years. CONTYPE (1 = governmental conflict and 0 territorial conflicts) is positively associated with IMPLEM at p < 0.05. This result aligns with earlier studies that territorial conflicts are difficult to solve, and the implementation scores are higher for governmental conflicts.Footnote104 Both variables of electoral and liberal democracy – EDINDEX, LDINDEX, and POLMIS – positively influence the implementation of peace agreements. These results are statistically significant at p < 0.05 and concur with the findings of the democratic civil peace thesis literature.Footnote105

I also find three control variables – GENDER, LEADAGE, and REBGRP – to negatively and statistically significantly influence the implementation of peace agreements. The statistical results presented in models 1–8 support my theoretical expectation that the implementation of peace agreements is more likely to decrease following male leaders assuming office. The results are statistically significant at β = −8.86 and p < 0.05 (model 1), β = −12.01 and p < 0.05 (model 3), β = −12.74 and p < 0.001 (model 7), β = −12.29 and p < 0.001 (model 8). However, the implementation of peace agreements increases following male leaders taking office in democratic countries. The coefficients of LEADAGE are statistically significant at p < 0.001 in model 3, model 5, and model 6, indicating the negative influence of the age of leaders on the implementation of peace agreements. These results align with Horowitz, McDermott, and Stam,Footnote106 who find that the increase in the age of leaders is more likely to initiate and escalate militarized disputes. Consistent with earlier studies,Footnote107 models 7–8 show a decrease in the implementation when the number of rebel groups increases at p < 0.001.

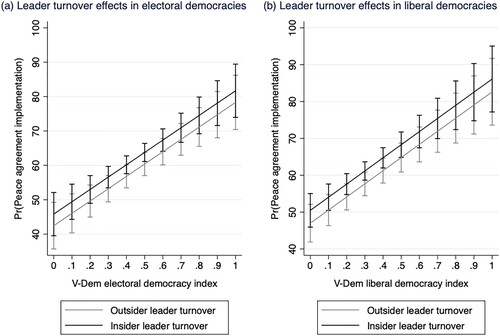

Based on the estimates of models 7–8 in , displays the predicted marginal effects of insider-outsider leader turnover effects on the implementation of peace agreements. The left panel of shows that the mean predicted level of the performance of peace agreements is 45.82 points for an insider turnover and 42.45 points for an outsider turnover at the low level of electoral democracy (0.00). Similarly, the mean predicted level of the performance of peace agreements for an insider turnover (81.69 points) is higher than the mean predicted level of the implementation of peace agreements for an outsider turnover (78.32 points) at a higher level of electoral democracy (1.00). Similarly, the right panel of demonstrates that the mean predicted level of the implementation of peace agreements is higher for an insider leader turnover than an outsider leader turnover at a lower and higher level of liberal democracy. These findings support my hypothesis that insider leader turnover positively impacts the implementation of peace agreements.

Conclusion

Existing research confirms the effects of leader turnover on peace negotiation and settlement. However, little is known about the impacts of insider-outsider leader turnover on the implementation of comprehensive peace agreements. This study has addressed this research gap by examining the relationship between leader turnover and the performance of peace agreements. The statistical results of this study reveal that insider leaders are more likely to facilitate the implementation of peace agreements. In contrast, an outsider leader turnover is more likely to hinder the performance of peace agreements in democratic countries. The findings of this empirical research are consistent with previous studies, which find outsider leaders as veto players and spoilers in the peace processes.

What are the policy implications of this empirical research? Many leading states are involved in international peacebuilding, for instance, India in Nepal's civil war and Japan's Mindanao conflict (Ochiai, Citation2016).Footnote108 Moreover, several regional and international organizations, including the United Nations (UN), European Union (EU), and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), play three kinds of peace-brokering roles: mediation, economic sanctions, and peacekeeping.Footnote109 After the end of the Cold War, the UN launched its first flurry of international peacebuilding missions to assist the implementation of peace agreements in conflict-affected countries such as El Salvador, Namibia, Cambodia, and Mozambique.Footnote110

International assistance is necessary to facilitate post-conflict reconstruction due to the war-torn economy, the absence of conflict resolution skills, and dysfunctional state institutions in conflict-affected countries. Surprisingly, international peacebuilding sometimes fails to achieve its main objectives despite good intentions.Footnote111 Existing literature on international peacebuilding does not offer insights into why and how leader turnover influences the implementation of peace agreements. This study suggests international peacebuilding actors conduct policy research on how to save peace agreements from failure when hawkish leaders come to power in conflict-affected countries.

To conclude, the generalizability of the results of this empirical research is subject to certain limitations. For instance, the impacts of government turnover on the execution of peace process and partial peace agreements are unknown in this study. Besides, whether younger, more polarized, and less consensus-oriented democracies have a lower implementation rate has remained unaddressed in this study. Additionally, some provisions, such as power-sharing and verification, might be easier to implement. In contrast, some provisions, such as provisions concerned with victim reparation and truth and reconciliation, might remain unimplemented for a long time. The question of what specific provisions is more likely to delay and complicate the implementation in the contexts of leader turnovers is beyond the scope of this research.

Acknowledgement

This research article is partially related to my PhD project, supervised in the School of Politics and International Relations (SPIR) at the Australian National University by Distinguished Professor of Political Science Ian McAllister, Professor Benjamin Goldsmith, and Dr. Svitlana Chernykh. I express my heartfelt gratitude to all of them for their excellent supervision and outstanding support throughout my PhD program. I am also grateful to Dr. Allard Duursma and two anonymous reviewers who provided me insightful feedback on this paper.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anurug Chakma

Anurug Chakma is a Research Fellow in the School of Regulation and Global Governance (RegNet) at the Australian National University. His research interests span from terrorism, civil conflict, and peacebuilding to migration, indigenous rights, and computational social science. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Notes

1 Chiozza and Geomans, “Leaders and International Conflict”; Wolford, “Wars of Succession”.

2 Wolford, “The Turnover Trap”.

3 Uzonyi and Wells, “Domestic Institutions”.

4 Wolford, “The Turnover Trap”.

5 Brown, “Ethnic and Internal Conflicts”.

6 For instance, Colaresi, “When Doves Cry”; Wolford, “The Turnover Trap”; Prorok, “Led Astry”.

7 For instance, Uzonyi and Wells, “Domestic Institutions”; Rivas and Tarín, “Leadership Style”.

8 Ryckman and Braithwaite, “Changing Horses in Midstream”.

9 Croco, “The Decider’s Dilemma”.

10 Warden, “Why Wanning Wars Wax”; Bokoe, “Toward a Theory of Peace Agreement Implementation”; Lyons, “The Successful Implementation”.

11 For example, Ryckman and Braithwaite, “Changing Horses in Midstream”.

12 ibid.

13 Beuno De Mesquita et al., “Testing Novel Implications”.

14 Lieberfeld, “Leadership Change and Negotiation”.

15 Ryckman and Braithwaite, “Changing Horses in Midstream”; Wolford, “The Turnover Trap”.

16 Uzonyi and Wells, “Domestic Institutions”.

17 Ryckman and Braithwaite, “Changing Horses in Midstream”; Wolford, “Incumbents, Successors, and Crisis Bargaining”.

18 Paris, “International Peacebuilding”.

19 Rosler, “Leadership and Peacemaking”.

20 Zajc, “Parliamentary Leadership”.

21 McAllister, “Political Leaders in Westminster System”.

22 Yovcheva, “Who Survives”.

23 For instance, Gormley-Heenan, “Chameleonic Leadership”.

24 Colburn, “The Turnover in El Salvador”.

25 Ortiz, “Political Leadership for Peace Process”.

26 Filippidou and O ́Biren, “Trust and Distrust”.

27 Maher and Thompson, “A Precarious Peace”.

28 Ortiz, “Political Leadership for Peace Process”.

29 Tellez, “Peace Agreement Design”.

30 Clare, “International Conflict Behavior”.

31 Gutiérrez D, “Towards a New Phase of Guerrilla Warfare”; Cohen-Almagor, “The Failed Palestinian-Israeli Peace Process”.

32 Wolford, “The Turnover Trap”.

33 Sela, “Difficult Dialogue”.

34 ibid.

35 For instance, Imbeau, Pétry, and Lamari, “Left-Right Party Ideology”; Tavits and Letki, “When Left is Right”.

36 Imbeau, Pétry, and Lamari, “Left-Right Party Ideology”; Ryckman and Braithwaite, “Changing Horses in Midstream”.

37 Stanley and Sawer, “The Equifinality of War Termination”.

38 Prorok, “Led Astray”.

39 Ryckman and Braithwaite, “Changing Horses in Midstream”.

40 Lieberfeld, “Leadership Change and Negotiation”.

41 Wolford, “The Turnover Trap”.

42 Rooney, “Sources of Leader Support”.

43 Wolford, “Incumbents, Successors, and Crisis Bargaining”.

44 Ryckman and Braithwaite, “Changing Horses in Midstream”.

45 ibid.

46 Ryckman and Braithwaite, “Changing Horses in Midstream”.

47 Ryckman and Braithwaite, “Changing Horses in Midstream”; Wolford, “Incumbents, Successors, and Crisis Bargaining”; Thyne, “Information, Commitment, and Intra-War Bargaining”.

48 Beuno De Mesquita, “Testing Novel Implication”.

49 Rooney, “Sources of Leader Support”.

50 Wolford, “Incumbents, Successors, and Crisis Bargaining”.

51 Wolford, “Wars of Succession”.

52 Ryckman and Braithwaite, “Changing Horses in Midstream”; Wolford, “Incumbents, Successors, and Crisis Bargaining”.

53 Quimpo, “Back to War in Mindanao”.

54 International Institute for Strategic Studies, “Separatists Rebellions”; Quimpo, “Back to War in Mindanao”.

55 Anson, “Mindanao on the Mend”.

56 Joshi, Quinn, and Regan, “Annualized Implementation Data”.

57 Mattes, Leeds, and Matsumura, “Measuring Change in Sources of Leader Support”.

58 Pettersson, Högbladh, and Öberg, “Organized Violence, 1989-2019”.

59 Joshi, Lee, and Ginty, “Built-in Safeguards”.

60 Ibid.

61 Ryckman and Braithwaite, “Changing Horses in Midstream”.

62 Mattes, Leeds, and Matsumura, “Measuring Change in Source of Leader Support”.

63 Prorok and Cil, “Cheap Talk or Costly Commitment?”.

64 ibid.

65 Joshi, Lee, and Ginty, “Built-in Safeguards”.

66 Horowitz, McDermott, and Stam, “Leader Age, Regime Type”.

67 Charlesworth, “Are Women Peaceful?”.

68 Krause, Krause, and Bränfors, “Women’s Participation in Peace Negotiations”.

69 Croco, “The Decider’s Dilemma”.

70 Horowitz, McDermott, and Stam, “Leader Age, Regime Type”.

71 Croco and Weeks, “War Outcomes”; Chiozza and Geomans, Leaders and International Conflict”.

72 Prorok, “Led Astray”.

73 Thyne, “Information, Commitment, and Crisis Bargaining”.

74 White, “The Perils of Peace”.

75 Pettersson, Högbladh, and Öberg, “Organized Violence, 1989-2019.

76 For instance, Duffy Toft, “Indivisible Territory”; Joshi, Lee, and Ginty, “Built-in Safeguards”.

77 Krause, Krause, and Branfors, “Women’s Participation in Peace Negotiations”.

78 Harbom, Högbladh, and Wallensteen, “Armed Conflict”.

79 Ramzi, “Intrastate Peace Agreements”.

80 For instance, Ramzi, “Intrastate Peace Agreements”.

81 Walter, “Does Conflict Beget Conflict?”.

82 Nilsson, “Turning Weakness into Strength”.

83 Nilsson, “Partial Peace”.

84 Joshi, Lee, and Ginty, “Built-in Safeguards”.

85 Clare, “International Conflict Behavior”; Palmer, London, and Regan, “What’s Stopping You?”.

86 Ross, “Does Democracy Reduce Infant Mortality?”.

87 Mason and Greig, “State Capacity”.

88 Joshi, Melander, and Quinn, “Sequencing the Peace”.

89 Harish and Little, “The Political Violence Cycle”.

90 Coppedge et al., “V-Dem Codebook”.

91 Rhoden, “The Liberal in Liberal Democracy”.

92 Paris, “International Peacebuilding”.

93 Coppedge et al., “V-Dem Codebook”.

94 Fortna, “Does Peacekeeping Work?”.

95 Maekawa, Arı, and Gizelis, “UN Involvement”.

96 ibid.

97 Joshi, Lee, and Ginty, “Built-in Safeguards”.

98 For instance, Mattes, Leeds, and Matsumura, “Measuring Change in Source of Leader Support”; Norrevik and Sarwari, “Third-party Regime Type”.

99 Vreeland, “The Effects of Political Regime”.

100 Yuko and Mori, “Better Regime Cutoffs”.

101 Rooney, “Sources of Leader Support”.

102 For instance, Ryckman and Braithwaite, “Changing Horses in Midstream.”

103 For instance, Thapa and Sharma, “From Insurgency to Democracy”; Colburn, “The Turnover in El Salvador”.

104 For instance, Duffy Toft, “Indivisible Territory”; Joshi, Lee, and Ginty, “Built-in Safeguards”.

105 Harish and Little, “The Political Violence Cycle”.

106 Horowitz, McDermott, and Stam, “Leader Age, Regime Type”.

107 For instance, Nilsson, “Partial Peace”; Nilsson, “Turning Weakness into Strength”.

108 Ochiai, “The Mindanao Conflict”.

109 Lundgren, “Conflict Management Capabilities”.

110 Paris, “Saving Liberal Peacebuilding”.

111 ibid.

References

- Anson, Ryan. “Mindanao on the Mend.” The SAIS Review of International Affairs 24, no. 1 (2004): 63–76.

- Beuno De Mesquita, Bruce, James D Morrow, Randolph M. Siverson, and Alastair Smith. “Testing Novel Implication from the Selecorate Theory of War.” World Politics 56, no. 3 (2004): 363–388.

- Brown, Michael E. “Ethnic and Internal Conflicts: Causes and Implications.” In Turbulent Peace: The challenges of managing international conflict, eds. Chester A. Crocker, Fen Osler Hampson, and Pamela Aall, 209–226. Washington, DC: USIP Press, 2001.

- Charlesworth, Hillary. “Are Women Peaceful? Reflections on the Role of Women in Peace-Building.” Feminist Legal Studies 16, no. 3 (2008): 347–361.

- Chiozza, Giacomo, and Hein Erich Goemans. Leaders and International Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Clare, Joe. “International Conflict Behavior of Parliamentary Democracies.” International Studies Quarterly 54, no. 4 (2010): 965–987.

- Cohen-Almagor, Raphael. “The Failed Palestinian-Israeli Peace Process 1993–2011: An Israeli Perspective.” Israel Affairs 18, no. 4 (2012): 563–576.

- Colaresi, Michael. “When Doves Cry: International Rivalry, Unreciprocated Cooperation, and Leadership Turnover.” American Journal of Political Science 48, no. 3 (2004): 555–570.

- Colburn, Forrest D. “The Turnover in El Salvador.” Journal of Democracy 20, no. 3 (2009): 143–152.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, et al. “V-Dem Codebook v12” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, 2022.

- Croco, Sarah E. “The Decider's Dilemma: Leader Culpability, War Outcomes, and Domestic Punishment.” American Political Science Review 105, no. 3 (2011): 457–477.

- Croco, Sarah E., and Jessica LP Weeks. “War Outcomes and Leader Tenure.” World Politics 68, no. 4 (2016): 577–607.

- Duffy Toft, Monica. “Indivisible Territory, Geographic Concentration, and Ethnic War.” Security Studies 12, no. 2 (2002): 82–119.

- Filippidou, Anastasia, and Thomas O’Brien. “Trust and Distrust in the Resolution of Protracted Social Conflicts: The Case of Colombia.” Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 14, no. 2 (2022): 1–21.

- Fortna, Virginia Page. Does Peacekeeping Work? Shaping Belligerents’ Choices after Civil War. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- Gormley-Heenan, Cathy. “Chameleonic Leadership: Towards a New Understanding of Political Leadership during the Northern Ireland Peace Process.” Leadership 2, no. 1 (2006): 53–75.

- Gutiérrez, D., and José Antonio. “Toward a New Phase of Guerrilla Warfare in Colombia? The Reconstitution of the FARC-EP in Perspective.” Latin American Perspectives 47, no. 5 (2020): 227–244.

- Harbom, Lotta, Stina Högbladh, Peter Wallensteen, Armed Conflict, and Peace Agreements. “”.” Journal of Peace Research 43 5 (2006): 617–631.

- Harish, S. P., and Andrew T. Little. “The Political Violence Cycle.” American Political Science Review 111, no. 2 (2017): 237–255.

- Horowitz, Michael, Rose McDermott, and Allan C. Stam. “Leader Age, Regime Type, and Violent International Relations.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 49, no. 5 (2005): 661–685.

- Imbeau, Louis M., François Pétry, and Moktar Lamari. “Left-Right Party Ideology and Government Policies: A Meta-Analysis.” European Journal of Political Research 40, no. 1 (2001): 1–29.

- International Institute for Strategic Studies. “Separatist Rebellions in the Southern Philippines: A Simmering Crisis.” Strategic Comments 6, no. 4 (2000): 1–2.

- Joshi, Madhav, Sung Yong Lee, and Roger Mac Ginty. “Built-in Safeguards and the Implementation of Civil War Peace Accords.” International Interactions 43, no. 6 (2017): 994–1018.

- Joshi, Madhav, Jason Michael Quinn, and Patrick M. Regan. “Annualized Implementation Data on Comprehensive Intrastate Peace Accords, 1989–2012.” Journal of Peace Research 52, no. 4 (2015): 551–562.

- Krause, Jana, Werner Krause, and Piia Bränfors. “Women’s Participation in Peace Negotiations and the Durability of Peace.” International Interactions 44, no. 6 (2018): 985–1016.

- Krause, Jana, Werner Krause, and Piia Bränfors. “Women’s Participation in Peace Negotiations and the Durability of Peace.” International Interactions 44, no. 6 (2018): 985–1016.

- Lieberfeld, Daniel. “Leadership Change and Negotiation Initiatives in Intractable Civil Conflicts.” International Journal of Peace Studies 21, no. 1 (2016): 19–43.

- Lundgren, Magnus. “Conflict Management Capabilities of Peace-Brokering International Organizations, 1945–2010: A New Dataset.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 33, no. 2 (2016): 198–223.

- Lyons, Terrence. “Postconflict Elections: War Termination, Democratization, and De-Militarization Politics.” Working Paper No. 20. Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, George Mason University, Washington DC, 2002.

- Maekawa, Wakako, Barış Arı, and Theodora-Ismene Gizelis. “UN Involvement and Civil War Peace Agreement Implementation.” Public Choice 178, no. 3–4 (2019): 397–416.

- Maher, David, and Andrew Thomson. “A Precarious Peace? The Threat of Paramilitary Violence to the Peace Process in Colombia.” Third World Quarterly 39, no. 11 (2018): 2142–2172.

- Mason, T. David, and J. Michael Greig. “State Capacity, Regime Type, and Sustaining the Peace after Civil War.” International Interactions 43, no. 6 (2017): 967–993.

- Mattes, Michaela, Brett Ashley Leeds, and Naoko Matsumura. “Measuring Change in Source of Leader Support: The CHISOLS Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 53, no. 2 (2016): 259–267.

- McAllister, Ian. “The Personalization of Politics.” In Oxford Handbook of Political Behaviour, eds. Russell J. Dalton, and Hand-Dieter Klingemann, 571–588. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Nilsson, Desirée. “Partial Peace: Rebel Groups Inside and Outside of Civil War Settlements.” Journal of Peace Research 45, no. 4 (2008): 479–495.

- Nilsson, Desirée. “Turning Weakness into Strength: Military Capabilities, Multiple Rebel Groups, and Negotiated Settlements.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 27, no. 3 (2010): 253–271.

- Norrevik, Sara, and Mehwish Sarwari. “Third-party Regime Type and Civil War Duration.” Journal of Peace Research 58, no. 6 (2021): 1256–1270.

- Ochiai, Naoyuki. “The Mindanao Conflict: Efforts for Building Peace through Development.” Asia-Pacific Review 23, no. 2 (2016): 37–59.

- Ortiz, Juliana Tappe. “Political Leadership for Peace Process: Juan Manuel Santos – Between Hawk and Dove.” Leadership 17, no. 1 (2021): 99–117.

- Paris, Roland. “International Peacebuilding and the ‘Mission Civilsatrice’.” Review of International Studies 28 (2002): 637–656.

- Paris, Roland. “Saving Liberal Peacebuilding.” Review of International Studies 36, no. 2 (2010): 337–365.

- Pettersson, Therése, Stina Högbladh, and Magnus Öberg. “Organized Violence, 1989–2019.” Journal of Peace Research 57, no. 4 (2019): 597–613.

- Prorok, Alyssa K. “Led Astray: Leaders and the Duration of Civil Wars.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 62, no. 6 (2018): 1179–1204.

- Prorok, Alyssa K., and Deniz Cil. “Cheap Talk or Costly Commitment? Leader Statements and the Implementation of Civil War Peace Agreements.” Journal of Peace Research 59, no. 3 (2022): 409–424.

- Quimpo, Nathan Gilbert. “Back to War in Mindanao: The Weakness of a Power-Based Approach in Conflict Resolution.” Philippine Political Science Journal 21, no. 44 (2000): 99–126.

- Ramzi, Badran. “Intrastate Peace Agreements and the Durability of Peace.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 31, no. 2 (2014): 193–217.

- Rhoden, T. F. “The Liberal in Liberal Democracy.” Democratization 22, no. 3 (2015): 560–578.

- Rivas, José Manuel, and Adrián Tarín. “Leadership Style and War and Peace Policies in the Context of Armed Conflict.” Problems of Post-Communism 64, no. 1 (2017): 1–19.

- Rooney, Bryan. “Sources of Leader Support and Interstate Rivalry.” International Interactions 44, no. 5 (2018): 969–983.

- Rosler, Nimrod. “Leadership and Peacemaking: Yitzhak Rabin and the Oslo Accords.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 54 (2016): 55–67.

- Ross, Michael. “Does Democracy Reduce Infant Mortality?” American Journal of Political Science 50, no. 4 (2006): 860–874.

- Ryckman, Kirssa Cline, and Jessica Maves Braithwaite. “Changing Horses in Midstream: Leadership Changes and the Civil War Peace Process.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 37, no. 1 (2020): 83–105.

- Sela, Avraham. “Difficult Dialogue: The Oslo Process in Israeli Perspective.” Macalester International 23 (2009): 105–138.

- Stanley, Elizabeth A., and John P. Sawyer. “The Equifinality of War Termination: Multiple Paths to Ending War.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 53, no. 5 (2009): 651–676.

- Tavits, Margit, and Natalia Letki. “When Left is Right: Party Ideology and Policy in Post-Communist Europe.” American Political Science Review 103, no. 4 (2009): 555–569.

- Tellez, Juan Fernando. “Peace Agreement Design and Public Support for Peace: Evidence from Colombia.” Journal of Peace Research 56, no. 6 (2019): 827–844.

- Thapa, Ganga B., and Jan Sharma. “From Insurgency to Democracy: The Challenges of Peace and Democracy-Building in Nepal.” International Political Science Review 30, no. 2 (2009): 205–219.

- Thyne, Clayton L. “Information, Commitment, and Intra-War Bargaining: The Effect of Governmental Constraints on Civil War Duration.” International Studies Quarterly 6, no. 2 (2012): 307–321.

- Uzonyi, Gary, and Matthew Wells. “Domestic Institutions, Leader Tenure and the Duration of Civil War.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 33, no. 3 (2016): 294–310.

- Vreeland, James Raymond. “The Effects of Political Regime on Civil War: Unpacking Anocracy.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 52, no. 3 (2008): 401–425.

- Walter, Barbara F. “Does Conflict Beget Conflict? Explaining Recurring Civil War.” Journal of Peace Research 41, no. 3 (2004): 371–388.

- Warden, Edwin Wuadom. “Why Waning Wars Wax; a Relook at the Failure of Arusha Peace Accord, the Peace Agreement-Implementation Gap and the Onset of the Rwandan Genocide.” Journal of Global Peace and Conflict 4, no. 1 (2016): 33–47.

- White, Peter B. “The Perils of Peace: Civil War Peace Agreements and Military Coups.” The Journal of Politics 82, no. 1 (2019): 104–118.

- Wolford, Scott. “The Turnover Trap: New Leaders, Reputation and International Conflict.” American Journal of Political Science 51, no. 4 (2007): 772–788.

- Wolford, Scott. “Incumbents, Successors, and Crisis Bargaining: Leadership Turnover as a Commitment Problem.” Journal of Peace Research 49, no. 4 (2012): 517–530.

- Wolford, Scott. “Wars of Succession.” International Interactions 44, no. 1 (2018): 173–187.

- Yovcheva, Teodora. “Who Survives and Who Does Not? The Rise and Decline of Personalized Parties.” East European Politics and Societies and Cultures 36, no. 1 (2022): 75–95.

- Yuko, Kasuya, and Kota Mori. “Better Regime Cutoffs for Continuous Democracy Measures.” https://v-dem.net/media/publications/users_working_paper_25.pdf.

- Zajc, Drago. “Parliamentary Leadership – Problems, Dilemmas and Opportunities of Legislative Leaders: The Case of Slovenia.” Journal of Comparative Politics 10 (2017): 57–68.