In a context in which the idea of globalisation is now routinely condemned in the name of a nationhood that should once again assert its sovereign pre-eminence, to question the purpose or place of this idea is both politically and intellectually risky. If the era of globalisation is coming to an end, it is often posited, then it is because the idea of the nation – as a territory and a population with a defined social and cultural character – is again in the ascendant. Any critical or intellectual challenge to globalisation today risks being perceived either as enabling neo-nationalist anti-globalism or as seeking to preserve neoliberalism’s crumbling narrative of open movement and free exchange. If we are to avoid these risks then one option is to look to Peter Sloterdijk’s observation that a structural shift is under way not because of the nation-state’s resurgence but because ‘we are today living through a dramatic crisis of reformatting’.1 In this drama, the disavowal of the foreign is aligned to a micropolitics in which groups and individuals are fixated on self-preservation and self-care, but the nation too is rejected as a principle and as a mechanism that permits shared association.

The essays in this special issue explore how this transformation and crisis demands a range of critical and theoretical manoeuvres which allow us to question the conceptual frame within which the global is conceived and reconsider territories, contexts and cultures in terms of globalised social and aesthetic production. Thus, Spivak’s acknowledgement in Citation2012 of a comprehensive geo-political shift in the era of globalisation is accompanied by a plea to rethink what she terms the profound ‘bipolarity’ or double-bind of globalisation’s effects.2 Against the familiar association of transborder exchange with the emergence of global community are accounts of a neoliberal moment that is characterised by the precarity of labour, the hardening of sovereign power and the financialisation of cultural exchange.3 And, against perceptions of the world as a site of ontological certainty, there is the growing sense that perceptions of globality rely on an uninterrogated concept of the world as a universal and comprehensible ground.4 It is by paying greater attention to responses to globalisation such as these that cultural theory and criticism can not only refine its borrowed social science repertory of tropes for picturing global connectivity and exchange, but also contest the assumption that the term ‘global’ allows us adequately to understand and capture humanity’s contemporary condition.

The starting point for this collection was a series of linked symposia that took place in Nottingham and Manchester.5 Our concerns were to share work that sought to engage with globalisation theory broadly conceived in the social sciences, and to explore a range of perspectives within arts and humanities that sought to ‘trouble’ the terms of these discussions, conceptions and mobilisations in cultural, philosophical and political discourse. Like many others, our project was overtaken by the global event(s) of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our confrontation with, and experience of being overtaken by, this event has involved a further reassessment of the ways that this pandemic has brought an apprehension of the global into view in new ways, on a ‘troubled’ worldwide scale. In Ulrich Beck’s account of the world risk society, perceptions of global risk ought to generate a cosmopolitan realpolitik, and he argues that ‘one of the most striking and heretofore least recognised key features of global risks is how they generate a kind of “compulsory cosmopolitanism” a “glue” for diversity and plurality in a world whose boundaries are as porous as Swiss Cheese at least as regards communication and economics’.6 This account might seem wildly optimistic in the current political moment, as the White House chief medical adviser Dr Anthony Fauci notes, ‘the only way that you’re going to adequately respond to a global pandemic is by having a global response [and that] means equity throughout the world. […] that’s something that, unfortunately, has not been accomplished’.7 Fauci’s comments might be construed as paraphrasing Latour’s view of the co-determination of the biological with the social, with a natural/cultural understanding of the pandemic as ‘simultaneously real, like nature, narrated, like discourse, and collective, like society’.8 Ursula K. Heise offers an extensive engagement with Beck’s model from the perspective of the environmental humanities, arguing it has much to bring to the theorisation of risk and its relation to globalisation.9 Risk perception, articulation or dissemination of these assessments to broader publics all involve mediation that relies on narrative, text, and other strategies of representation, where an environmentally inflected imagining of the relationship of local to global can develop an attentiveness to the ways that worldwide phenomena are foundational to personal experience.

Ironically, COVID-19 hit the world at a moment when the political disavowal of a global imperative was reaching new heights in ethno-nationalist neo-liberal discourses in countries such as the US, UK, India, Brazil and Hungary. In this environment COVID-19 has revealed a dysfunctional system of global governance and exacerbated other barriers to reform with a rise of racist and nationalist agendas that fail to see the damage is everywhere and is global. The pandemic played out an immediate realisation of our interconnectedness even while it also saw nations, necessarily, withdrawing into national boundaries in an attempt to dampen the communication of the disease. This experience obviously stands in sharp contrast to the claim made by many commentators that globalisation ended in the first decade of the twenty-first century. Such claims appeared to rest upon a singular and narrow economic conception of globalisation. Starting from the assumption that globalisation represented a particular model of late-capitalism – intensified by low-tariff trade regimes, efficient trade logistics and the dematerialisation of production – the financial crisis of 2007-2008 seemed to sound the death knell for a particular kind of financialised economics. This prediction was given further energy by the growth of an increasingly nationalist political populism which found favour in countries such as Australia, Greece, Hungary, and, most persuasively, in the USA. When the 45th President of the United States of America deployed a slew of executive orders to insulate the nation and to wage trade skirmishes against its international trading partners, it was easy to see why some felt that an era of globalisation had come to an end.

Though it can be hard to pinpoint truly ‘global’ events, the experience of the global pandemic has felt like something that has been genuinely planetary in its reach. There have certainly been different national experiences of COVID-19, with some nations experiencing relatively low infection rates and mortality figures, while others have experienced alarming public-health crises. Nevertheless, even successful mitigation has been achieved through challenging social restrictions that have widely altered the relationship of individuals to their social environment, even where these had previously seemed relatively stable. Whether this was through regional quarantining or restrictions on international travel, the relationship between people and place have undergone substantial reassessment. In her shattering account of the Indian lockdown instigated by Narendra Modi in April 2020, Arundhati Roy brings into sharp relief the entwined trajectories of COVID-19 and global finance, commenting, ‘the virus has moved freely along the pathways of trade and international capital’.10 She notes the reporting of the first COVID-19 case in India just days after Brazilian premier Jair Bolsonaro was guest of honour at the Republic Day parade and only weeks before the arrival of President Trump on an official visit. Both far-right premiers have been ostentatious COVID deniers, and are accused of personally acting as vectors for the disease through their own international travel, lack of care whilst ill and extensive social events that flouted their respective country’s recommended distancing or masking. Roy’s article bears witness to the disaster that unfolded as India finally went into lockdown with four hours’ notice to its citizens: as all transport ceased, hundreds of thousands of migrant workers started unfeasibly long journeys back to their village homes on foot. This internal displacement enacted a violence on the lives of the migrant poor in India where the concept of locking down transformed into a mass exodus as ‘megacities began to extrude their working-class citizens – their migrant workers – like so much unwanted accrual’.11 Roy’s bleak predictions for the spread and (loss of) control of COVID-19 in India in 2020 have begun to play out horrifyingly in 2021. In the meantime, Bolsonaro would become globally visible in a way that his rise to power in Brazil had not been, circulating on social media under the hashtag #bolsonarogenocida.

The pandemic has also produced an array of instances where our everyday frames of reference have become internationalised. Whether it is the regularity of international comparisons around a variety of indices, from infection rates to vaccinations; whether it is the precipitous collapse of the aviation industry; or whether it is the xenophobic rhetoric of conspiracy theorists, the public story of COVID-19 has been undeniably transnational in scale. This argues for the continuing attention to the global as an object of analysis. Even if the economic elements of globalisation are altered, which was always debatable, there are substantial social and cultural components of globalisation which appear to be as prominent as always.12 Phenomena such as distanciation, weightlessness, mass migration or environmentalism, which are all hallmarks of globalisation theory, are as prominent now as they were at the turn of the millennium.13 In Arjun Appadurai’s canonical explanation of global modernity, he proposed globalisation as a set of uneven global scapes which globally-dispersed communities occupy in varying and discontinuous ways.14 Such a conception still appears to have substantial explanatory potential. Sitting in Britain, watching Black Lives Matter protests in US cities on television and through social media, and then seeing – also on television and social media – protestors in the UK city of Bristol, carrying images of George Floyd’s face, go on to pull down the statue of an infamous slave-trader, was to see the collision of Appadurai’s ethnoscapes, mediascapes and ideoscapes. The ability of cultural images to travel and translate almost immediately onto different political and historical realities seems unquestionably an example of globalisation. The role of global social-media corporations is certainly part of this story. However, the fact that many of the most visible global brands are effectively electronic publishing platforms has meant that the cultural flows of globalisation have become increasingly prominent.15 One of the stories of globalisation has always been the desire to rescue the idea of the global from a narrow market-led conception. This is evident in a number of social movements – such as the World Social Forum, which first met in Brazil 2001 as an alternative to the World Economic Forum – as well as in the academic work from the social sciences and the humanities.16 Theories of cosmopolitanism, planetariness or worldliness, have all sought to articulate conceptions of globalisation that sit slightly offset from one another and which cannot be comfortably reduced to a single unified notion of the term.

This idea of globalisation as a contested term finds a symmetry in other theories of globalisation, which have emphasised the way that places exist in relation to scale. The theorist Anna Tsing has given prominent attention to a concept like place-making as a way to think about the manner in which places simultaneously coexist locally and globally. In an account of speculative foreign investments in Indonesian gold mining during the 1990s, Tsing considers how competing imaginaries of place challenge the idea of an evolutionary movement from the local to the global. Instead, she suggests, places are constantly projected as global spaces by new globalist projects. Looking at the way that locally Canadian myths of frontierism combined with locally Indonesian dreams of an economic miracle in order to project a narrative of globally dynamic finance, Tsing traces the way that a global scale is ‘brought into being’ by a performative drama that proposes and enacts one perspective on Indonesian specificity.17 Tsing’s emphasis on how a global scale is made and remade through particular kinds of performative enactments proposes long histories for globalisation but it also should encourage a scepticism about the predictions of the demise of globalisation. From this perspective, globalisation is and always was contingent and mutable.

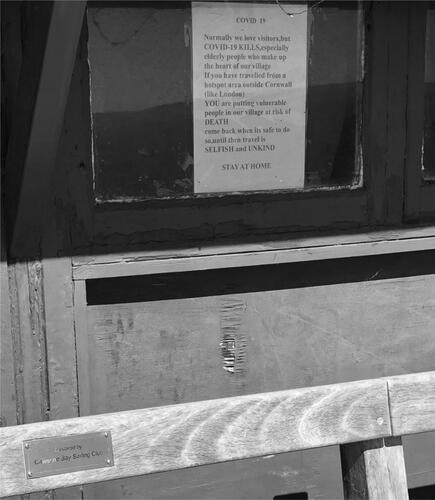

Tsing’s account of globalisation as one kind of place-making that exists synchronously with other forms of spatial meaning-making might usefully explain the cultural experience of living thorough a global pandemic. Culturally, COVID-19 had a significant spatial component, engaging geographical terrains in multiple ways, which produced differential meanings for place. In the UK, for instance, the pandemic was simultaneously a global, a national and a local event. In some ways, the UK’s response to the virus typified internationalist or globalist visions of the nation, especially when it emphasised the connected nature of modern nations with reference to the global spread of the virus. The development of COVID vaccines by British-based biotech researchers in collaboration with European pharmaceutical conglomerates and manufacturers dispersed across Europe, Asia and Australia might be an exemplary illustration of globalisation as integration. At the same time, the pandemic engaged the national border as a meaningful boundary, something that could be policed in an effort to limit the spread of the virus by quarantining the nation. However, this same logic also saw the hardening of the UK’s internal borders, which appeared to give life to the nationalist claims of the UK’s constituent nations. Public health has been devolved to the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly (now the Welsh Parliament) since the late 1990s. Consequently, policies on COVID mitigation were formulated at the level of the constituent nations. One aspect of this was to limit travel across the Welsh and Scottish borders with England in an attempt to slow transmission between different parts of the UK. As a result, the internal borders of the UK became functioning frontiers in ways not witnessed since the 1707 Act of Union. In addition, fear of the virus has also seen a more ad hoc and informal retreat into local communities throughout the UK. For instance, shows a poster from the small Cornish village, Cawsand, discouraging tourists from visiting the village in an attempt to protect an elderly local population.

Similarly, shows posters outside a general store in the Sussex village of Newick inviting villagers to #shoplocal. Although this slogan has been used in the UK for some time and has been deployed as a twitter handle since 2012, the message took on a new meaning as it chimed with Government advice to ‘stay local’ as a measure against COVID transmission. The combination of the slogan with the injunction not to panic also clearly addresses the immediate context of the pandemic.

The commerce of the pandemic has paradoxically pulled in both directions, boosting global brands but also sustaining local retailers. The growth of online shopping as a response to the COVID crisis has hastened the decline of high-street shopping in the UK and swelled the market-share of global retailers such as Amazon. However, at the same time, the pandemic has been a boost for some local businesses. During early periods of panic-buying, for instance, local shops were sometimes found to hold stock that had sold out in larger supermarkets. Similarly, wary shoppers hoping to avoid large queues were sometimes lured to smaller retailers and the growth of homeworking led to a similar tilt to local shopping.

All these iterations of place played out in the same year, which makes it hard to describe the present moment through a simple temporality of globalisation. At points, it would be possible for UK inhabitants to think of themselves as living in an array of places all of which emanate from the same geographic location. The UK did not become incrementally more or less global, it simply engaged with globalism to different degrees depending upon circumstances. While there are evidently interests that are served by these engagements (political, economic, and social), it remains important to be attentive to what Tsing calls a ‘dramatic performance’ of place.18 In this respect Tsing represents a branch of theories of globalisation which emphasise its discursive nature. For instance, Peer Fiss and Paul Hirsch approach globalisation as a kind of ‘discursive framing’ through which ‘material change and symbolic construction’ combine. They highlight the autonomy of ‘meaning and meaning creation’ which work within the structural constraints of empirical data to produce an explanatory frame for material change.19 In The Imagined Economies of Globalization, Angus Cameron and Ronen Palan offer a similar analysis, arguing that globalisation is a narrative frame that is realised as ‘a story of temporal change’ through which ‘the world is becoming “more global”’ and a spatial transformation in which global space replaces the territorial state.20

These approaches to globalisation signal the important space for cultural theory and criticism as apparatuses that are capable of interrogating the discourses or narrative of the global. The essays gathered together in this special issue distance themselves from early descriptions of transnational culture as internationally unifying or all-encompassing – descriptions which serve to underpin a ‘cultural logic’ of globalisation where cosmopolitanism becomes the critical bedfellow of the ultra-mobility of markets and data. By contrast, these explorations of travel, internationalisation and migration focus on globalisation’s failure at homogenisation and its radically polarising consequences. They detect in the trajectories taken by globalisation not a fruitfully hybridising Third Space of intercultural encounter, but a markedly unsettling condition that gives rise to much more compelling accounts of how global culture is experienced discrepantly and anxiously. Cultural theory and criticism can and must take debates about global culture further by instigating a more fundamental interrogation of the conceptual and creative frames within which the global has so far come to be conceived. Against the historiography of rupture and rift that confines globalisation to the contemporary period, and against the perception that early transnationalisms functioned merely as global culture’s prehistory, it is now necessary to address a longer history that begins in earlier efforts to imagine the complex entanglement of worldly connectivities, for example in early modern cartography, navigation, traffic and trade. If, in this manner, contemporary cultural theory and criticism can be shown to open up globalisation to an alternative archaeology, then it ought also to be able to project different (anti)teleologies that challenge both pronouncements of a world finally in contact with itself and declarations of national or ethnic exceptionality.

The sense of multiple, incommensurate, facets to globalisation is important to the contributions to this themed issue. Focusing on post-apocalyptic fiction, Diletta De Cristofaro considers how contemporary writing confronts the prospect of global climate collapse that defines our Anthropocene present, identifying patterns of repetition that link these fictions’ environmentally devasted futures to the colonial past. These patterns, De Cristofaro argues, highlight a long history of imperialist practices of capitalist exploitation that lead to the environmental risks of today’s globalised world. For Liam Connell, border fortification and securitisation need to be understood as a new expression of contradictions that always inhabited globalisation. Focusing on how the border is depicted as a textual object in recent literary fiction, Connell suggests that readers’ capacity to interpret depictions of border crossing is shaped by the aesthetic framing of the border as object, which in turn is shaped by the extra-textual discourse of securitisation as the expression of the contradictions within state-power in relation to extant forms of transnationalism. Bringing together artworks and poetry that respond to migrant deaths in the Mediterranean in the early twenty-first century, Ellie Byrne considers how directions in contemporary Black Studies and postcolonial criticism can contribute to how we are to understand these tragedies and the EU’s current water border policing strategies that have helped to produce them. This work, Byrne argues, provokes a departure from the spectacle of disaster that has dominated media responses to deaths in the Mediterranean, situating them instead within the global afterlives of slavery and empire. Also reflecting on maritime migration in the early twenty-first century, Philip Leonard’s essay discusses what life and death mean in Europe’s littoral spaces. Not only suspending the normal operations of territorial rule, these spaces also, he proposes, require us to rethink the global regulation of life in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Arin Keeble and James Annesley examine two contemporary novels that confront the failings of globalism and multiculturalism. For them, what these texts show are the many conceptual and material deficiencies that shape neoliberal ideas about meritocratic and inclusive connectedness, revealing instead the structural inequality and systemic violence that have been enabled by global discourses and practices. In the final essay in this issue, Martin Crowley examines recent theoretical responses to the planetary ecological crisis in order to address what human action means in the context of this crisis. What is needed, Crowley concludes, is a geopolitically sensitive approach to agency, one that combines the capacity to act with a recognition of an ecologically distributed and plural ontology.

Acknowledgements

This issue develops from a series of symposia hosted by Nottingham Trent University and Manchester Metropolitan University in 2017. The editors thank the British Academy and Leverhulme Trust for supporting these symposia.

Notes

1 Sloterdijk, What Happened in the 20th Century?, 53.

2 Spivak, An Aesthetic Education, passim.

3 See, for example, Hardt & Negri, Multitude; Agamben, State of Exception; Ong, Neoliberalism as Exception; Stiegler, States of Shock.

4 See, for example, Nancy, The Creation of the World or Globalization; Cazdyn & Szeman, After Globalization; Apter, Against World Literature; Sloterdijk, Globes; Naas, The End of the World; Cheah, What is a World?: Cohen & Elkins-Tanton, Earth.

5 “Troubling Globalisation.”

6 Ulrich Beck, World at Risk, 188.

7 Davey, “‘We’re all in this together’.”

8 Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, cited in Alaimo, Bodily Natures, 28. Italics in original.

9 Heise, Sense of Place Sense of Planet.

10 Roy, “The Pandemic is a Portal.”

11 Ibid.

12 In Globalization in Question, Hirst and Thompson argue that contemporary trade internationalisation closely resembles the levels of transnational transactions in the late-nineteenth century and challenge the assumption that the economics of globalisation are much different from earlier forms of economic activity.

13 Giddens, The Consequences of Modernity; Morley and Robins, Spaces of Identity; Bauman, Liquid Modernity; Castles and Davidson, Citizenship and Migration; Horn and Bergthaller. The Anthropocene.

14 Appadurai, Modernity at Large, 31-37.

15 The legal arguments between social-media platforms and legislators over who has responsibility for the content that they publish indicates something of the degree to which this content does not precisely align with the market interests of twenty-first-century capitalism.

16 World Social Forum, “About the World Social Forum.”

17 Tsing, Friction, 55-77.

18 Ibid. 57.

19 Fiss and Hirsch, “The Discourse of Globalization.”

20 Cameron and Palan, The Imagined Economies of Globalization.

Bibliography

- Agamben, Giorgio. State of Exception. Translated by Kevin Attell. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Alaimo, Stacey. Bodily Natures: Science, Environment and the Material Self. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

- Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

- Apter, Emily. Against World Literature: On the Politics of Untranslatability. London: Verso, 2013.

- Bauman, Zygmunt. Liquid Modernity. Polity Press: Cambridge, 2000.

- Beck, Ulrich. World at Risk. Translated by Ciaran Cronin. Cambridge: Polity, 2009.

- Cameron, Angus and Ronen Palan. The Imagined Economies of Globalization. London: Sage, 2004.

- Castles, Stephen, and Alastair Davidson. Citizenship and Migration: Globalization and the Politics of Belonging. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2000.

- Cazdyn, Eric, and Imre Szeman. After Globalization. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

- Cheah, Pheng. What is a World? On Postcolonial Literature as World Literature. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

- Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome, and Linda T. Elkins-Tanton. Earth. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

- Davey, Melissa. “‘We’re all in this together’: Dr Fauci says world has failed India as Covid cases surge.” The Guardian, April 28, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/28/were-all-in-this-together-dr-fauci-says-world-has-failed-india-as-covid-cases-surge.

- Giddens, Anthony. The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity, 1990.

- Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire. London: Penguin, 2004.

- Heise, Ursula K. Sense of Place Sense of Planet: The Environmental Imagination of the Global. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Hirst, Paul, and Grahame Thompson. Globalization in Question: The International Economy and the Possibilities of Governance. Cambridge: Polity, 1999.

- Horn, Eva, and Hannes Bergthaller. The Anthropocene: Key Issues for the Humanities. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Morley, David, and Kevin Robins. Spaces of Identity: Global Media, Electronic Landscapes and Cultural Boundaries. London: Routledge, 1995.

- Naas, Michael. The End of the World and Other Teachable Moments: Jacques Derrida’s Final Seminar. New York: Fordham University Press, 2015.

- Nancy, Jean-Luc. The Creation of the World or Globalization. Translated by François Raffoul and David Pettigrew. New York: State University of New York Press, 2007.

- Ong, Aihwa. Neoliberalism as Exception: Mutations in Citizenship and Sovereignty. Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

- Peer, C. Fiss and Paul M. Hirsch. “The Discourse of Globalization: Framing and Sensemaking of an Emerging Concept.” American Sociological Review 70, no. 1, (2005): 29–52.

- Roy, Arundhati. “The Pandemic is a Portal”. The Financial Times, April 3, 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca.

- Sloterdijk, Peter. Globes: Spheres Volume II: Macrosphereology. Translated by Wieland Hoban. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2014.

- Sloterdijk, Peter. What Happened in the 20th Century? Towards a Critique of Extremist Reason. Translated by Christopher Turner. Cambridge: Polity, 2018.

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

- Stiegler, Bernard. States of Shock: Stupidity and Knowledge in the 21st Century. Translated by Daniel Ross. Cambridge: Polity, 2015.

- “Troubling Globalisation: New Approaches in the Arts and Humanities.” Accessed April 29, 2021. https://troublingglobalisation.wordpress.com/.

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- World Social Forum. “About the World Social Forum.” Accessed July 18, 2017. https://fsm2016.org/en/sinformer/a-propos-du-forum-social-mondial/.