Mother Nature is the greatest bioterrorist of them all, with no financial limitations or ethical compunctions.Footnote1

Introduction

Just few months after the first cases were identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, the World Health Organisation declared the novel coronavirus disease (Covid-19) a pandemic on March 11, 2020. Besides its significant impact on health and the human body, Covid-19 has affected many aspects of everyday life, reconfiguring how we work, study, shop, travel, and meet. Some of these effects are also related to the acceleration, intensification, and normalisation of surveillance practices that might outlive the pandemic itself. As David Lyon argues, pandemic surveillance has resulted in a “surveillance pandemic”, given the marked increase in tracking and monitoring practices, and the growing cultural acceptance of these practices.Footnote2

Drawing on global examples of Covid-19 technologies, this article examines some of the socio-political and ethical implications of these technologies. It frames the discussion within ‘immunopolitics’ – a form of governance that takes the immunity of individuals and populations as the basis for interventions and management techniques. As defined by Benoît Dillet, immunopolitics is ‘the permanent demand for preventive measures in the search of a total immunisation from others, bacteria, terrorism, problems, or simply, negativity’.Footnote3 By examining Covid-19 technologies as a modality of what I call “governing through immunity”, I aim to bring into sharper focus the intertwinement of biology, technology, and politics, articulating what is at stake in living in what Nick Brown refers to as an ‘immunitary life’.Footnote4 Along the way, I will also highlight the economic dimension of immunopolitics, manifest, on the one hand, in the public-private partnerships that have supported the development of Covid-19 technologies (such as tracing apps), and, on the other, in the forms of inequalities that have been exacerbated by the pandemic, such as the inequitable access to Covid-19 vaccines and the disproportionate exposure to coronavirus of those who did not have the option of working from home. Immunopolitics thus inevitably connects to issues of agency; it remediates perceptions of risk and delineates the conditions of possibility within which the agential subject of immunity can act. Since the beginning of the pandemic, agency has been shaped and, often, constrained, in the name of protection and in pursuit of immunisation.

Covid-19 Management Technologies

To begin with, it is worth pointing out that this is not the first time in history that we are faced with an outbreak of a highly infectious disease. What is perhaps unique about the current pandemic is that it has been unfolding against the backdrop of a digital world that is increasingly ruled by data, algorithms, apps, and online platforms. One could argue that other recent outbreaks, such as H1N1 in 2009, unfolded against a similar background and that the ‘novelty’ of the current pandemic and its implications is not that new after all. However other outbreaks did not spread with the same speed. From an epidemiological perspective, Covid-19 led to many more deaths and critical cases.Footnote5 Importantly, for our present discussion, the digital world, too, has changed since 2009, both quantitatively and qualitatively. We now generate and collect more data than ever before; our everyday activities are increasingly appified and digitalised. Culturally, there is also more acceptance of intrusive digital technologies.

Consider, for instance, biometrics. This technology, which genealogically goes back to anthropometry – a technical approach to human measurement and classification developed by the French police officer Alphonse Bertillon in the 1880s – was initially deployed in the context of criminal investigations. A ‘biometric boom’ was then experienced in the late 1960s when fingerprinting and semi-automated facial recognition became widely used in law enforcement.Footnote6 Gradually, biometrics started to seep into other fields such border control, immigration management, and the workplace. While for many years biometrics remained confined to these specific spaces and contexts, over the last decade, it has become a ‘technology of the everyday’, mainly due to its rapid adoption in the consumer sphere, and embedment in everyday products and spaces such as mobile phones, smart watches, fitness trackers, internet banking, gyms, and schools. So, by infiltrating the consumer sphere rather than remaining within the governmental and policing spheres, biometrics has been normalised and accepted as a convenient technology of the everyday. Similarly, technologies and techniques that would have seemed intrusive a few years ago are now so commonplace that it can seem paranoid to resist them.Footnote7

It is, therefore, important to remind ourselves that the culture of surveillance we live in is not always entirely imposed from above in a top-down Big Brother way. It relies on consumer consent, citizen participation, the power of technological seduction, and the promise of ease, convenience, and safety. Many Covid-19 technologies promise protection and, ultimately, a return to ‘normality’. Speaking of data technologies in general, Natasha Lushetich argues that the current relentless data extraction has ‘little to do with the totalitarian ambition to master the entire semantic field in order to control everyone’.Footnote8 Instead, ‘data extraction is a mode of production as well as a mode of exchange’.Footnote9 I would add that this form of exchange is not based on reciprocity but on imbalanced power relations in the sense that there is a plethora of private and public institutions, commercial companies, and law enforcement agencies that are constantly extracting data from us, but we rarely get to extract data from them, or contest the categorical assumptions made on the basis of the extracted data. It is a one-way knowledge production involving various information asymmetries.Footnote10

Given the combination of digital developments, the proliferation of data extraction mechanisms, and their increasing cultural acceptance, it is not surprising that the governmental responses to the Covid-19 pandemic have sought to harness the power and normalisation of the existing technologies to contain the spread of coronavirus and get to grips with the indeterminacy of the pandemic. By and large, responses to Covid-19 across the world have been driven by digital solutionism and a technocratic approach to health and disease management. Mobile tracking applications, biometric techniques, and AI solutions have been adopted around the world to manage the pandemic and detect cases before individuals become symptomatic. While such technologies vary from country to country in terms of design, function, and policy ecosystems, they typically rely on smartphones and make use of GPS, Bluetooth technology, QR codes, AI, and biometrics to track movement, monitor temperature, predict outbreaks, and trace contact between individuals. Some of the most widely used technologies are Covid-19 tracking apps which determine proximity between users and alert them to potential exposure to the virus. As Covid-19 vaccination programmes continue to be rolled out across the world, many Covid-19 tracking apps now contain information about the individuals’ vaccination status and are being used as vaccine/immunity passports. They have been deployed as a means to restore a sense of normality and re-open the economy after many lockdowns.

One of the main challenges of mapping the implications of such technologies and techniques is their heterogeneity. There is no common ground nor unified global standards regarding Covid-19 design or the policy requirements concerning data collection and use. For instance, in some countries, such as the UK and US, Covid-19 tracking apps have been developed under the principle of ‘privacy by design’, adopting a decentralised management strategy whereby the collected data are stored on the user’s phone and not transferred to a cloud system or database. In other countries, such as China and South Korea, the tracing apps enable linking with governmental agencies and data storage on centralised systems. The use of the tracing apps is also variously compulsory and voluntary, depending on the country as is the level of informed consent. The way technologies and digital systems are designed, deployed, and used, is often reflective of the political milieu, societal contexts, and the policy ecosystems within which they operate.

One of the most discussed and controversial examples is China’s Health Code app. This app, which is now mandatory, was developed by Alibaba affiliate, Ant Financial, and the social media company, Tencent. Both are private companies with a strong presence in the Chinese society. The Health Code, developed out of this partnership, operates in the form of a mini programme that is integrated into existing app services, including the widely used WeChat and Alipay.Footnote11 What this means is that users do not need to explicitly consent to accessing the app since access is already established through other apps such as WeChat.

The Health Code app provides users with a designated QR colour code to determine the users’ risk and right to move and travel. People with green status are permitted to travel freely; yellow imposes some restrictions on mobility; red indicates the highest risk of being Covid-19 positive and requires quarantine.Footnote12 To obtain the QR code, users are required to enter reams of personal data including passport number, contact details, current location, and contact with Covid-19 patients in the past 14 days. Data are also pulled from many other sources including medical records. A code is then automatically generated. As a centralised system, the app feeds the collected data into a national database, which, according to media reports, is also shared with the police.Footnote13 But as Shin Bin Tan and co-authors argue, the exact data sources, parameters and algorithms generating these health codes remain shrouded in mystery.Footnote14 This leaves no space for negotiating or contesting possible misclassification due to erroneous data or correlations, which drastically reduces the agential power of users. The authors suggest that the generation of health codes may be embedded in parameters such as location records generated from GPS and telecom signal, records of fever clinic visits and fever-reducing drug purchase, travel history in high-risk regions, close contact with confirmed or suspected cases, and self-declared physical symptoms. Recent media reports and users’ testimonies suggest that simple transactions like the purchase of cold remedies over the counter or online, are uploaded to the database, triggering an alert and a possible change in colour code, which can lead to individuals being forced to self-isolate.Footnote15

What is interesting about the Health Code app is that it is an example par excellence of the state’s strong ties with private companies, a form of ‘alliance capitalism’ which encourages public-private partnerships.Footnote16 Writing about the Chinese context, Victoria Higgins argues that China has been at the forefront of alliance capitalism given the embeddedness of ‘relational ties and collaborative R&D activity’ within the innovation ecosystem,Footnote17 which brings government actors and technological actors even closer.Footnote18 This, according to the author, results in ‘open systems’ that are characterised by interconnectedness and information sharing, as is the case with the wireless communication sector and the way Chinese digital platforms have been widely integrated in state governance.Footnote19 In the context of Covid-19, such established alliances between the state and tech companies have allowed the government to seamlessly access a wealth of users’ data, including location data received from telecoms carriers, Tencent and Alibaba.Footnote20

While many countries around the world are keen to move onto the ‘next normal’ and seem to be embracing what epidemiologist Michael Osterholm refers to as ‘collective amnesia’, China is still maintaining a strict and cautious approach to the management of Covid-19.Footnote21 At the time of writing, the Health Code app continues to be a crucial tool in managing the pandemic, acting as a condition of possibility for performing everyday activities and accessing services, including public transport and schools. This has already resulted in many segments of the Chinese society being excluded from vital spaces and services. For instance, some elderly people are not able to enter supermarkets and do their grocery shopping due to not having a smartphone on which to run the Health Code app and obtain a QR code.Footnote22 Technosolutionism, in this sense, ends up excluding the most vulnerable populations as the design of such technologies is often calibrated on the assumption of total digital access and technical aptitude.

A different example is the UK’s NHS Covid-19 app, which, unlike China’s Health Code app, is both decentralised and voluntary. It functions according to the principle of ‘privacy by design’. The user remains anonymous to the system but can choose to share information with the server. Unlike the Health Code app, the process is exclusively performed on the device and does not link to a centralised database. Whereas the Heath Code app focuses on location, the NHS app focuses on proximity.Footnote23 It uses Bluetooth technology to understand the distance, over time, between app users. Users are sent an exposure notification with guidance if they have been within 2 meters of someone for 15 minutes or longer who has since tested positive. Unlike China’s Health Code app whose function and algorithm remain opaque to the public, the NHS published detailed information on how its Covid-19 algorithm app works and how risk levels are calculated. The NHS app is also an example of the private-public alliance, mentioned earlier, in that it uses Apple and Google exposure notification system to conduct Bluetooth-enabled contact tracing rather than being developed by the government itself. The system uses Application Programming Interface (API), a software intermediary that allows two applications to communicate. This process requires the latest iOS and Android operating systems, which was the reason why many users with older smartphones were unable to use the app. The ‘digital divide’, in this case, is not just between those who own and those who do not own smartphones, but between different smartphone models since most Covid-19 apps around the world require the latest operating systems.

As such, technological affordances play a crucial role in shaping users’ agency, access, and experience of Covid-19 related apps, resulting, at times, in forms of exclusion, even if this is a byproduct rather than the intended outcome. The scope of exclusion ranges from access to training, to embodied aspects related to disabilities – for instance, the fact that many people with weak eyesight and/or hearing cannot discern many digital signals, or the way that digital prostheses have an implicit reliance on ‘healthy bodies’ even when they are designed to overcome an impediment, which in turn can create more problems for the user than it solves. But while, in China, individuals who do not have or cannot use a smartphone are unable to access vital services and spaces, in the UK, one could still access everyday necessities despite not having the NHS Covid-19 app. The digital divide, in this sense, is not experienced in the same way nor does it have the same implications.

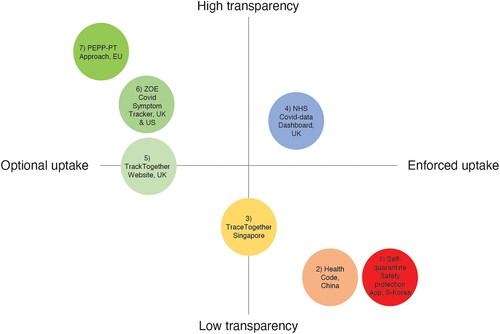

In terms of effectiveness and ‘usefulness’, it is argued that Covid-19 apps which use the Google-Apple system are less useful for public health, given that no data are transferred to a centralised system for follow-up or disease modellingFootnote24 – although such data constitute raw material for platform companiesFootnote25, feeding the surveillance capitalism Shoshana Zuboff speaks of.Footnote26 Apps such as China’s Health Code are considered more effective given the wealth of data they gather and the higher rate of participation due to their mandatory aspect. While such apps are functionally superior, they are also ethically more disconcerting. As Lyon argues, more sophisticated technical solutions tend to be less supportive of privacy, human rights, trust, and transparency.Footnote27 Sanna Rimpiläinen et al. created a diagram (), which presents a spectrum of Covid-19 apps and platforms, arranged on the axis of high versus low transparency in terms of both development and user privacy, and optional versus enforced uptake.Footnote28

Figure 1 Sanna Rimpiläinen et al., Spectrum of Apps from enforced to optional, 2020. Courtesy of Sanna Rimpiläinen.

As can be seen, Covid-19 apps from Asia tend to fall within the low-transparency and mandatory category, whereas apps from the UK, the EU, and the US are more transparent and less compulsory. That is not to say that Western countries have more ethical technologies. However, this visualisation is a useful reminder that Covid-19 technologies have not been developed in a homogenous way or out of context, but are embedded in a political, social, cultural, and historical milieu, reflecting the norms, values, and style of governance of their given ecosystem. Speaking of the comparison between the ‘West’ and the ‘East’, even the EU, which is arguably the leader in the fight for data protection, has adapted to what is seen as an inevitable need for more surveillance and data collection to manage Covid-19.Footnote29 The following statement by the European Data Protection Supervisor, Wojciech Wiewiórowski, made at the beginning of the pandemic, is a case in point:

Thinking about the EDPS’ strategy for the next five years, we have to look again at our text. Whatever happens in the next few weeks, we know the words will not be the same. We will all be confronted with this game changer in one way or another. And we will all ask ourselves whether we are ready to sacrifice our fundamental rights in order to feel better and to be more secure.Footnote30

Apps, obviously, are not the only response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Biometric thermal imaging is also a technique that became widely used across the world in airports, supermarkets, banks, stadiums and schools.Footnote33 Given the link between Covid-19 and fever, thermal imaging techniques intercept heat to detect individuals who might have higher temperature than normal. Since the beginning of the pandemic, many companies and start-ups jumped at the opportunity to develop and market these biometric solutions despite the limitations of thermal imaging and its potential inaccuracies. As we know now, not everyone develops a fever after catching coronavirus and asymptomatic people can also be highly infectious. AI and machine learning are used, too. For example, in France, the start-up company Clevy launched an AI chatbot powered by real-time information from the French government and the World Health Organisation. The chatbot assesses symptoms and answers questions about current government regulations. It has been used in many French cities to decentralise the distribution of accurate, verified information and reduce strain on the resources of healthcare.Footnote34 Another example is BlueDot which uses machine learning algorithms to sift through news reports in 65 languages, along with airline data and animal disease networks to detect and anticipate outbreaks. BlueDot provides these insights to public health officials, airlines, and hospitals to help them anticipate and manage risks and resources.Footnote35

Although different in their design, structure, and function, the unificatory feature of these technologies is that they all rely on the convergence of body and data to perform surveillance and contribute to the ‘immunisation’ of the population against coronavirus. And here, immunisation, is not only about inoculation or exposure to the virus to achieve immunity. It also gestures towards the techniques of separation and differentiation which seek to distinguish between levels of risk and determine mobility and access rights, as is the case of Covid-19 apps and vaccination passports. These acts of differentiation and categorisation are by no means mere technical acts. They are also highly political as they shape the functioning of society and everyday life. As such, and by way of critique, let us look at Covid-19 technologies through the lens of ‘immunopolitics’ to better articulate what is at stake in the governmental responses to the pandemic.

Immunopolitics of Covid-19

Like the more widely used concept of biopolitics, immunopolitics is concerned with how life itself is governed and managed in contemporary societies but extends the biopolitical debate further by zooming into the notion of immunity and considering how it connects biological life to political life. Theorists such as Roberto Esposito,Footnote36 Donna Haraway,Footnote37 Nik Brown,Footnote38 and Ed Cohen have been instrumental in bringing awareness to the social meaning and political function of immunity before the outbreak of coronavirus.Footnote39 Crucial to their arguments is that immunity is not merely a medical or scientific term but a powerful socio-political metaphor which structures the boundaries between the inside and outside, self and other, and individual and common, foregrounding the logic of separation. As Haraway argues, ‘the immune system is a map drawn to guide recognition and misrecognition of self and other in the dialectics of western biopolitics. That is, the immune system is a plan for meaningful action to construct and maintain the boundaries for what may count as self and other in the crucial realm of the normal and the pathological’.Footnote40 It is in this sense that Esposito considers immunity as the basis of contemporary politics and a framework for modernity itself. He writes:

Whether the danger that lies in wait is a disease threatening the individual body, a violent intrusion into the body politic, or a deviant message entering the body electronic, what remains constant is the place where the threat is located, always on the border between the inside and the outside, between the self and the other, the individual and the common.Footnote41

Biomedicine’s later interpretations and appropriation of the concept of immunity have faithfully preserved its original legal meaning. Just as in Roman law immunity meant an exemption from certain communal obligations, in biomedicine and its offshoot field of immunology, immunity means an exemption from the experience of certain infections and diseases. More importantly, biomedical notions of immunity have mobilised war-like metaphors and discourses of self-defence, often found in the political arena, to describe biological phenomena, even when the latter do not resemble the original politico-legal meaning of immunity. Cohen thus argues that:

the language of friend and enemy in no way derives from the matter of the world; it does not describe the unfolding of biochemical processes according to immutable natural laws; it does not constitute an unmediated representation of an essential physical truth; rather, the trope of friend and enemy has circumscribed Western politics since Aristotle. In fact, it has provided a canonical framework for defining ‘the political’ as such ever since there first was a polis. More important for my purposes, it has also underwritten the bioscientific investment in immunity as a biological form of self-defence for the last one hundred years.Footnote46

What is more, politicians are not the only ones invoking war metaphors. Health workers have often been portrayed as ‘combatants’ risking their lives at the ‘frontline’ to treat Covid-19 patients. For instance, in early 2021, immunologist and Oxford professor John Bell urged the UK government on TV to react to Covid-19 as to an enemy invading the country:

People have rightly pointed to the Israelis, who have managed to immunise lots of people. You have to view it as if it were a war. The Israelis are good at getting on a war footing – everyone is waiting for the 2am call anyway. Here, it is not clear whether it’s a national security issue, but it is.Footnote47

It is no wonder that Roberto Esposito saw governmental responses to Covid-19 as symptomatic of a ‘veritable immunization syndrome that has long characterized the new biopolitical regime’.Footnote49 Such defensive immunopolitics manages life by shifting from ordinary processes to emergency measures, blurring the difference between care and control. This is also related to the inherently paradoxical nature of immunity itself; for life to be preserved in the immunitary sense, ‘something needs to be introduced into it that negates it to the point of supressing it’.Footnote50 This is the case in the immunological and political sense. Immunologically, vaccines protect life by incorporating the external threat within the body rather than keeping it at a distance. As Esposito argues, immunity ‘can prolong life, but only by continuously giving it a taste of death.’Footnote51 In other words, within the immunitary paradigm, the body defeats a virus by making it part of itself rather than expelling it; it makes life possible through its own negation. This logic also informs politics in the sense that the protection of life often involves the mobilisation of mechanisms that are illiberal, all in the name of defence and protection, as in the case of the war on terror, immigration, border policies, and Covid-19.

Governing through immunity, therefore, means defending society from disease and those who carry it at the cost of mobilising controversial, and/or unprecedented measures. For the striving for immunity, both in a biological and a political sense, often justifies exceptional interventions with potentially long-term effects. But as Michel Foucault reminds us, defending society also involves scarifying segments of it and exposing some to risk so that the rest can keep on living, a logic that is at the heart of modern politics and its power to ‘make live and let die’, as Foucault put it.Footnote52 So, to fully understand the immunopolitics of Covid-19 and its technologies, one should not only look at the defensive aspect, but also at the ‘letting die’ aspect. In the context of Covid-19, this manifested rather dramatically through the contentious notion of herd immunity, or more precisely “natural herd immunity” through mass infection, which, in the early phase of the pandemic and before the rollout of Covid-19 vaccines, was embraced by some governments as a way of avoiding economic damage that would have resulted from strict containment measures. We have seen how, despite scientists’ warnings, several countries such as Sweden have shown willingness, both explicit and implicit, to accept the death of the elderly and the sick by following this type of immunity as an alternative to closing their economies.Footnote53 We can recall the governor of Texas, Dan Patrick, who famously told Fox News in March 2020 that ‘he would rather die than see public health measures damage the US economy and that he believed “lots of grandparents” across the country would agree with him’.Footnote54

In Brazil, the government was criticised for failing to develop a national plan to fight Covid-19, and for prioritising economic growth over public health concerns. This resulted in Brazil becoming one of the countries with the highest Covid-19 mortality rate.Footnote55 So, while some country leaders have been criticised for their excessive interventions and heavy-handed approach to pandemic management, other governments have been criticised for blatant inaction which had dramatic effects on the lives of their populations. The sacrificial aspect of Covid-19 immunopolitics was also apparent in the disproportionate exposure to coronavirus of those who did not have the option of working from home. In the UK, this has led to more deaths among groups from BAME backgrounds as they are overrepresented in frontline roles and precarious occupations, including nursing, care, delivery, and public transport. Such reality demonstrates that the current pandemic does not affect everyone in the same way nor is its impact equally felt. This is not only in terms of Covid-19′s health implications for old versus young generations, but also in terms of the familiar class and racial aspects that are deeply entrenched in society and in the exploitative workings of capitalist systems.

In its intersection with politics and economics, immunity becomes more than a matter of defending society from the spread of disease, but also a matter of exposing some to danger for the sake of the survival of the economy.Footnote56 One may quibble here that with the rollout of Covid-19 vaccines worldwide, many of these issues have been resolved as herd immunity is now being sought through inoculation rather than natural exposure, which neutralises the sacrificial issues discussed hitherto. However, not all countries have equal access to Covid-19 vaccines. While some countries are giving more booster shots to their citizens, others are still struggling to acquire enough first doses of the vaccine.Footnote57 Sweden, for instance, is now planning to administer the fifth dose of Covid-19 vaccine to those over 65 and pregnant people, while many low-income countries are still relying on Gavi’s COVAX programme which, reportedly, can only achieve 20% vaccination coverage.Footnote58 This has ramifications not only for equity but also for the pandemic itself. If developed countries keep on administering booster shots while the rest of the world is still struggling with vaccine access, it is unlikely that there will be an end to the pandemic any time soon, as the virus will keep mutating and spreading. Vaccine inequity is not only morally problematic but also pragmatically. In addition to vaccine inequity, there is also the challenge of vaccine hesitancy. There is now an established body of research showing a high level of vaccine hesitancy among minority ethnic groups because of their past (negative) experience with government and healthcare institutions that have affected their trust.Footnote59

What all this highlights is the inevitability of struggle over how societies are governed not only during times of crisis but also in ‘normal’ times. This is primarily a struggle over the interplay between politics, biology, immunity, and technology. So, while tracking apps, thermal imaging, vaccine passports, and other surveillance mechanisms are packaged and promoted as a potent solution to Covid-19, they are merely examples of the techno-capitalist solutions and digital plasters applied to quickly compensate for the long-standing failures to address pre-existing health inequalities and a lack of adequate preparedness.Footnote60 To devise a truly ethical response to the pandemic, governments must resist the seduction of technological determinism fostered by alliance capitalism and invest instead in more equal and fair forms of living in which everyone has equal agency, and no life can be sacrificed in favour of another.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Btihaj Ajana

Btihaj Ajana is Professor of Ethics and Digital Culture at the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College London. Her academic research is interdisciplinary and focuses on the ethical, political and ontological aspects of digital developments and their intersection with everyday cultures. She is the author of Governing through Biometrics: The Biopolitics of Identity (2013) and editor of Self-Tracking: Empirical and Philosophical Investigations (2018); Metric Culture: Ontologies of Self-Tracking Practices (2018); and The Quantification of Bodies in Health: Multidisciplinary Perspectives (2021). Ajana also uses filmmaking to explore social issues. Her most recent films include Quantified Life (2017); Surveillance Culture (2017); Fem's Way (2020); and Borderscapes (2022). Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Osterholm and Olshaker, Deadliest Enemy, 466.

2 Lyon, Pandemic Surveillance, 17.

3 Dillet, “Suffocation and the Logic of Immunopolitics,” 1.

4 Brown, Immunitary Life.

5 Da Costa et al, “Comparative Epidemiology,” 1800.

6 BioConnect, “A Brief History of Biometrics.”

7 Lynskey, “The tech industry’s disregard,” 2019; Ajana. “Biometric Datafication,” 64.

8 Lushetich, “Prologue: Why Ask the Question?,” 4.

9 Ibid.

10 Aas, “‘The body does not lie.’”; Ajana, “Recombinant Identities.”; Ajana, “Augmented Borders.”

11 Yang et al, “China, Coronavirus and Surveillance,” 2020.

12 Rimpiläinen et al, “Global Examples of COVID-19 Surveillance Technologies,” 13.

13 Mozur et al, “In Coronavirus Fight,” 2020.

14 Tan et al, “From SARS to COVID-19,” 2020.

15 Long and Chingman, “China's COVID-19 ‘Health Code’ App,” 2022.

16 Eichhorn, “The Public Private Partnership,” 225.

17 Higgins, Alliance Capitalism.

18 Ibid., 11.

19 See also Wanshu Cong, “From Pandemic Control to Data-Driven Governance: The Case of China’s Health Code.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2021, 7. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3787996.

20 Yang et al “Comparative Analysis of China’s Health Code,” 182.

21 Osterholm and Wurzer, “Osterholm: A Blueprint,” 2022.

22 Li, “‘We Are Left Behind by Technology,’” 2020.

23 NHS X, “NHS COVID-19 App,” 2021.

24 Lyon, Pandemic Surveillance, 32.

25 Ibid., 9.

26 Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

27 Lyon, Pandemic Surveillance, 32.

28 Rimpiläinen et al., “Global Examples of COVID-19 Surveillance Technologies.”

29 See also Mercedes Bunz, “Contact Tracing Apps: Should We Embrace Surveillance?” April 29, 2020. https://mercedesbunz.net/2020/04/29/630/.

30 Wiewiórowski, “The Moment You Realise,” 2020.

31 Liu, “Chinese Public’s Support,” 89.

32 Omanovic, “A Recipe for Hypocrisy,” 2020.

33 Van Natta et al, “The Rise and Regulation of Thermal Facial Recognition Technology,” 6.

34 Sivasubramanian, “How AI and Machine Learning.”

35 Tang, “How BlueDot Leverages Data Integration,” 2020.

36 Esposito, Immunitas.

37 Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs and Women.

38 Brown, Immunitary Life.

39 Cohen, A Body Worth Defending.

40 Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs and Women, 204.

41 Esposito, Immunitas, 2.

42 Ajana, “Immunitarianism.”

43 Cohen, A Body Worth Defending, 274.

44 Davis et al “Immunity, Biopolitics and Pandemics,” 133.

45 Esposito, Immunitas, 16.

46 Cohen, A Body Worth Defending, 277.

47 Bell in Otte, “NHS Could Caccinate UK.”

48 Caso, “Are We at War?.”

49 Esposito, “Biopolitics and Coronavirus.”

50 Esposito, Immunitas, 33.

51 Ibid., 9.

52 Foucault, “Society Must Be Defended.”

53 Basu, “The ‘Herd Immunity’ Route to Fighting Coronavirus” 2020; Rossman, “Coronavirus: Can Herd Immunity Really Protect Us?.”

54 Beckett, “Older People Would Rather Die.”

55 Worldometers, “Coronavirus Seaths.”

56 Ajana, “Immunitarianism,” 24.

57 Rydland et al “The Radically Unequal Distribution of Covid-19 Vaccinations,” 1–6.

58 Berkley, “COVAX Explained.”

59 Hussain et al “Overcoming COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy.”; Majee et al “The Past Is so Present.”

60 Morozov, “The Tech ‘Solutions’ for Coronavirus.”

Bibliography

- Aas, Katja Franko. “‘The Body Does Not Lie’: Identity, Risk and Trust in Technoculture.” Crime, Media, Culture: An International Journal 2 (2) (2006): 143–58.

- Ajana, Btihaj. “Recombinant Identities: Biometrics and Narrative Bioethics.” Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 7 (2) (2010): 237–258.

- Ajana, Btihaj. “Augmented Borders: Big Data and the Ethics of Immigration Control.” Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society 13 (1) (2015): 58–78.

- Ajana, Btihaj. “Biometric datafication in Governmental and Personal Spheres.” In Big Data: A New Medium? (1 st ed.), edited by Natasha Lushetich. London and New York: Routledge. 2021a.

- Ajana, Btihaj. “Immunitarianism: Defence and Sacrifice in the Politics of Covid-19.” History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 43 (1), 2021b.

- Basu, Arindam. “The ‘Herd Immunity’ Route to Fighting Coronavirus Is Unethical and Potentially Dangerous.” The Conversation. 2020. https://theconversation.com/the-herd-immunity-route-to-fighting-coronavirus-is-unethical-and-potentially-dangerous-133765. Accessed 18 March 2020.

- Beckett, Lois. “Older People Would Rather Die than Let Covid-19 Harm US Economy – Texas Official.” The Guardian, March 24, 2020, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/24/older-people-would-rather-die-than-let-covid-19-lockdown-harm-us-economy-texas-official-dan-patrick. Accessed 24 March 2020.

- Berkley, Seth. “COVAX Explained.” www.gavi.org. September 3, 2020. https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/covax-explained. Accessed 10 January 2021.

- BioConnect. “A Brief History of Biometrics”. December 8, 2021. https://bioconnect.com/2021/12/08/a-brief-history-of-biometrics/. Accessed 20 August 2022.

- Brown, Nik. Immunitary Life: A Biopolitics of Immunity. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

- Bunz, Mercedes. “Contact Tracing Apps: Should We Embrace Surveillance?” April 29, 2020. https://mercedesbunz.net/2020/04/29/630/. Accessed 10 September 2021.

- Caso, Federica. “Are We at War? The Rhetoric of War in the Coronavirus Pandemic.” The Disorder of Things. April 10, 2020. https://thedisorderofthings.com/2020/04/10/are-we-at-war-the-rhetoric-of-war-in-the-coronavirus-pandemic/. Accessed 3 December 2020.

- Cohen, Ed. A Body Worth Defending: Immunity, Biopolitics, and the Apotheosis of the Modern Body. Durham: Duke University Press, 2009.

- Cong, Wanshu. “From Pandemic Control to Data-Driven Governance: The Case of China’s Health Code.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2021.

- Da Costa, Vivaldo Gomes, Marielena Vogel Saivish, Dhullya Eduarda Resende Santos, Rebeca Francielle de Lima Silva, and Marcos Lázaro Moreli. “Comparative Epidemiology between the 2009 H1N1 Influenza and COVID-19 Pandemics.” Journal of Infection and Public Health 13 (12) (2020): 1797–1804.

- Davis, Mark, Paul Flowers, Davina Lohm, Emily Waller, and Niamh Stephenson. “Immunity, Biopolitics and Pandemics.” Body & Society 22 (4) (2016): 130–54.

- Dillet, Benoît. “Suffocation and the Logic of Immunopolitics.” In Biopolitical Governance: Race, Gender and Economy, edited by Hannah Richter, 235–54. London: Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd, 2018.

- Eichhorn, Peter. “The Public Private Partnership.” In From Alliance Practices to Alliance Capitalism, edited by Sabine Urban, 225–239. Wiesbaden: Gabler Verlag, 1998.

- Esposito, Roberto. Immunitas: The Protection and Negation of Life. Editorial: Cambridge; Malden MA: Polity, 2011.

- Esposito, Roberto. “Biopolitics and Coronavirus: A View from Italy.” The Philosophical Salon. March 31, 2020. https://thephilosophicalsalon.com/biopolitics-and-coronavirus-a-view-from-italy/. Accessed 10 January 2021.

- Foucault, Michel. “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–76. New York: Picador, 2003.

- Haraway, D.J. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, 1991.

- Higgins, Victoria. Alliance Capitalism, Innovation and the Chinese State the Global Wireless Sector. Houndmills, Basingstoke Hampshire Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Hussain, Basharat, Asam Latif, Stephen Timmons, Kennedy Nkhoma, and Laura B. Nellums. “Overcoming COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Ethnic Minorities: A Systematic Review of UK Studies.” Vaccine, 2022.

- Long, Qiao and Chingman. “China’s COVID-19 ‘Health Code’ App Reaps Huge Datasets on Population.” Radio Free Asia, 2022. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/app-01272022102806.html. Accessed 20 August 2022.

- Li, Zhengqi. “‘We Are Left behind by Technology’: Chinese Elderly Are Facing the Digital Divide.” Life360. August 31, 2020. https://cardiffjournalism.co.uk/life360/we-are-left-behind-by-technology%EF%BC%9Achinese-elderly-are-facing-the-digital-divide/. Accessed 10 January 2021.

- Liu, Chuncheng. “Chinese Public’s Support for COVID-19 Surveillance in Relation to the West.” Surveillance & Society 19 (1) (2021): 89–93.

- Lushetich, Natasha. “Prologue: Why Ask the Question?” In Big Data: A New Medium? (1 st ed.), edited by Natasha Lushetich. Oxon: Routledge, 2021.

- Lynskey, Dorian. “The Tech Industry’s Disregard for Privacy Relies on the Consent of Its Customers.” New Statesman. 2019. https://www.newstatesman.com/science-tech/social-media/2019/06/tech-industry-s-disregard-privacy-relies-consent-its-customers. Accessed 17 June 2019.

- Lyon, David. Pandemic Surveillance. S.L.: Polity Press, 2022.

- Majee, Wilson, Adaobi Anakwe, Kelechi Onyeaka, and Idethia S. Harvey. “The Past Is so Present: Understanding COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among African American Adults Using Qualitative Data.” Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 10 (2023): 462–474.

- Morozov, Evgeny. 2020. “The Tech ‘Solutions’ for Coronavirus Take the Surveillance State to the next Level.” The Guardian, April 15, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/15/tech-coronavirus-surveilance-state-digital-disrupt. Accessed 10 January 2021.

- Mozur, Paul, Raymond Zhong, and Aaron Krolik. “In Coronavirus Fight, China Gives Citizens a Color Code, with Red Flags.” The New York Times, March 1, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/01/business/china-coronavirus-surveillance.html. Accessed 10 January 2021.

- NHS X. “NHS COVID-19 app.”, 2021. https://www.nhsx.nhs.uk/covid-19-response/nhs-covid-19-app/. Accessed 10 May 2022.

- Omanovic, Edin. “A Recipe for Hypocrisy: Democracies Export Surveillance Tech without Human Rights.” about:intel. July 9, 2020. https://aboutintel.eu/surveillance-export-human-rights/. Accessed 10 May 2022.

- Osterholm, Michael and Mark Olshaker. Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs. S.L.: John Murray Publishers Lt, 2017.

- Osterholm, Michael and Cathy Wurzer,. “Osterholm: A Blueprint on Moving to the ‘next Normal’ in Pandemic.” MPR News, 2022. https://www.mprnews.org/story/2022/03/07/osterholm-a-bluepint-on-moving-to-the-next-normal-in-pandemic. Accessed 10 May 2022.

- Otte, Jedidajah. “NHS could vaccinate UK against Covid in five days, says Oxford professor.” The Guardian, January 9, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/09/nhs-vaccinate-uk-covid-five-daysoxfordprofessor?CMP=fb_gu&utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Facebook&fbclid=IwAR1yYfM8qj1Fu3disew1O_D6VODMegK6-EJLPT4aJphnvnYD3aR69dUDsoY#Echobox=1610210628. Accessed 9 January 2021.

- Rimpiläinen, Sanna, Jennifer Thomson, and Ciarán Morrison. Global Examples of COVID-19 Surveillance Technologies: Flash Report. April 16, 2021. https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/72028/1/Rimpilainen_etal_DHI_2020_Global_examples_of_Covid_19_surveillance_technologies.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2022.

- Rossman, Jeremy. “Coronavirus: Can Herd Immunity Really Protect Us?” The Conversation, March 13, 2020. https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-can-herd-immunity-really-protect-us-133583. Accessed 13 March 2020.

- Rydland, Håvard Thorsen, Joseph Friedman, Silvia Stringhini, Bruce G. Link, and Terje Andreas Eikemo. “The Radically Unequal Distribution of Covid-19 Vaccinations: A Predictable yet Avoidable Symptom of the Fundamental Causes of Inequality.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 9 (1) (2022): 1–6.

- Sivasubramanian, Swami. “How AI and Machine Learning Are Helping to Tackle COVID-19.” World Economic Forum. May 28, 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/how-ai-and-machine-learning-are-helping-to-fight-covid-19/. Accessed 10 May 2022.

- Tan, Shin Bin, Colleen Chiu-Shee, and Fábio Duarte. “From SARS to COVID-19: Digital Infrastructures of Surveillance and Segregation in Exceptional Times.” Cities 120 (103486), 2020.

- Tang, Vivian. “How BlueDot Leverages Data Integration to Predict COVID-19 Spread.” 2020. Safe Software. October 15, 2020. https://www.safe.com/blog/2020/10/bluedot-leverages-data-integration-predict-covid-19-spread/. Accessed 10 January 2021.

- Van Natta, Meredith, Paul Chen, Savannah Herbek, Rishabh Jain, Nicole Kastelic, Evan Katz, Micalyn Struble, Vineel Vanam, and Niharika Vattikonda. “The Rise and Regulation of Thermal Facial Recognition Technology during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Law and the Biosciences 7 (1), 2020.

- Wiewiórowski, Wojciech. “The moment you realise the world has changed: re-thinking the EDPS Strategy.” European Data Protection Supervisor, March 20, 2020. https://edps.europa.eu/press-publications/press-news/blog/moment-you-realise-world-has-changed-re-thinking-edps-strategy_en. Accessed 20 July 2020.

- Worldometeres. “Coronavirus deaths.” 2022. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Accessed 25 July 2022.

- Yang, Fan, Luke Heemsbergen, and Robbie Fordyce. “Comparative Analysis of China’s Health Code, Australia’s COVIDSafe and New Zealand’s COVID Tracer Surveillance Apps: A New Corona of Public Health Governmentality?” Media International Australia 178 (1): 1329878X2096827, 2020.

- Yang, Yuan, et al. “China, coronavirus and surveillance: the messy reality of personal data.” Financial Times, April 1, 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/760142e6-740e-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca. Accessed 10 January 2021.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for the Future at the New Frontier of Power. London: Profile Books, 2019.