?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The promotion of self-employment through financial inclusion initiatives has been adopted as a means of harnessing the entrepreneurial and productive capacities of women within the neoliberal developmental policy framework. This study presents a simple analytical model in the Post-Keynesian tradition to investigate the linkages between self-employment, aggregate demand, and unpaid care work by developing a two-sector model. It shows that a developmental strategy based on fostering women’s self-employment is constrained, on the one hand, by the macroeconomic conditions driving aggregate demand and, on the other, by the trade-off between the time allocation between unpaid care and paid work that the gendered division of care work responsibilities imposes on the self-employed woman worker. The promotion of self-employment cannot serve as a viable development strategy without policies that directly boost aggregate demand and at the same time relieve the burden of care responsibilities on women through public investment and social provision of care.

HIGHLIGHTS

Self-employment is too often uncritically prescribed as a vehicle for improving women’s livelihoods.

Increased self-employment creates competing claims on women’s time between paid work and unpaid care.

Women’s self-employment perpetuates gendered asymmetries of care responsibilities within the household.

Macroeconomic demand conditions constrain the potential for women’s self-employment to increase livelihoods and support development.

Financial inclusion policies alone have limited scope in sustaining women’s self-employment.

INTRODUCTION

Self-employment constitutes about 45 percent of women’s employment globally (International Labour Organization [ILO] Citation2020) and is an important source of livelihood for women in low-income households in developing countries across Latin America, Asia, and Africa. While self-employed workers form a heterogenous group, ranging from street vendors and food-stall operators to home-producers of goods like garments, bags, and baskets, self-employment, particularly home-based production, remains a precarious form of informal work. In the hierarchy of informal employment categories such employment is characterized by low average earnings and high poverty risk (Chen et al. Citation2005). There is also evidence that self-employment acts as a safety net for workers without access to stable wage employment and tends to be larger in countries that have lower labor productivity (Loayza and Rigolini Citation2011).

In light of the significance of self-employment in developing countries, identifying constraints and impediments that self-employed workers face in transforming into viable small entrepreneurs has assumed importance for development policy. An important constraint that is identified is the lack of access to credit. With the promotion by the World Bank in the 1990s of the “financial systems approach” emphasizing financial viability (Robinson Citation2001), followed by the adoption of “financial inclusion” as a developmental priority (and not simply a poverty alleviation strategy), most significantly after the Great Financial Crisis (World Bank Citation2008), neoliberal policy prescriptions have focused on buttressing access to credit as the path to support and promote self-employment. Instead of state-funded development-oriented policies that promote decent and stable wage employment, financial inclusion schemes such as microfinance has been held up as a kind of deux-ex-machina that would enable women to set up microenterprises that harness their entrepreneurial and productive capacities (Bateman Citation2012; Bateman and Chang Citation2012; Taylor Citation2012; dos Santos and Kvangraven Citation2017).

However, the lack of clear evidence for transformative effects of microfinance for poverty reduction or improvement in standard of living (Marr Citation2012; Banerjee Citation2013; Banerjee, Karlan, and Zinman Citation2015) suggests that the success of microenterprises and self-employment strategies, in general, are not related simply to access to credit. This underscores the need to understand the key constraints that impede the mobilization of the productive capacities of women in low-income households in developing countries. In this context, the interdependence of women’s self-employment opportunities with the wider macroeconomy and with the care economy have received less analytical attention. This study aims to address this gap in the literature.

We present a two-sector model within the Post-Keynesian tradition that addresses the linkages between self-employment, the macroeconomy, and unpaid care. The two sectors are distinguished in terms of institutional structure and mode of employment. We develop a model to study the interaction of non-market provision of care with demand dynamics in a context where self-employment is seen as a vehicle for economic development. The model is meant to clarify, analytically, how the effectiveness of this developmental strategy depends on macroeconomic conditions driving aggregate demand on one hand, and on the other, by the trade-off between the allocation of time between care work and paid work imposed by the gendered division of care work responsibilities on the self-employed woman entrepreneur-worker.

THE DUAL CONSTRAINTS ON SELF-EMPLOYMENT AS A DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY

Self-employment accounts for as much as 88 percent of women’s employment in low-income countries and 67 percent in low middle-income countries (Table ). The high dependence on self-employment can be seen as a symptom of a dearth of stable wage employment (Banerjee and Duflo Citation2011). About two-thirds of self-employment in developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America results from individuals having no better alternatives (Margolis Citation2014). For developing countries, the resort to self-employment reflects rationing or involuntary exclusion from stable wage employment rather than a voluntary exit from the labor market in pursuit of entrepreneurial opportunities (Gindling and Newhouse Citation2014).

Table 1 Employment status by country groupings (percentage of employed)

T. H. Gindling and David Newhouse (Citation2014) find that only a small proportion (between 17 and 33 percent) of the self-employed in low-income countries are successful or have a potential for being successful, with these proportions rising as per-capita incomes rises. The lack of evidence that self-employment in the form of household microenterprises constitutes a viable path to stable livelihoods has been ascribed to limited access to formal institutional credit. This is seen as a critical constraint for pursuit of self-employment opportunities in low-income rural households and by women in particular who are subject to limited property rights and access to collateral in the credit market, and to patriarchal norms that restrict their capacity to participate in labor markets. The impetus for financial inclusion as a development policy has been informed by the view that access to credit through microfinance enables women to start their own microenterprises, and is therefore a significant step in providing opportunity for gainful self-employment, income generation, and empowerment. These household-based microenterprises include activities like cattle and poultry rearing, basket-weaving, food-processing, tailoring, and petty trade.

However, the household is also the principal site for provisioning of care-labor, including activities like cleaning, cooking, childcare and, eldercare. Care work is crucial for the maintenance and reproduction of labor capacities and capabilities, and consequently also for labor productivity. Outside the private sphere of the family, care can be provided socially through community and state organizations – for instance, community kitchens or public creches, or privately though markets. While community ties can be an important source of social provisioning of care in rural economies, public investment in the social provisioning of care in rural areas in many developing countries has been curtailed as a consequence of the structural reforms that enforced a cutback in state spending. Further, the market for care may not provide a perfect substitute for the unpaid care provided within the family, and access would be limited for low-income rural households. Thus, given gendered norms that impose the primary responsibility for care on women, the scope for market participation is circumscribed.

Self-employment in home-based microenterprises is potentially less disruptive to these gendered norms around care labor. There is a greater scope for blurring the boundaries between unpaid care work and paid self-employment, which allows greater complementarity between paid and unpaid work, but also further cements the gendered norms for care work. The nature of the household microenterprises is such that the isolation of the woman within the household is not broken, despite the increased access to economic resources (Goetz and Gupta Citation1996; Ehlers and Main Citation1998). It is not surprising that the evidence on the capacity of such microenterprises to empower women is mixed and depends not only on increased access to resources but also on the scope for building organizational capacities and bargaining power (Kabeer Citation2002). The structure of gender asymmetries and unequal interdependence within the household could lead to women seeking more equality within the family, through access to credit and self-employment rather than greater independence from the family (Kabeer Citation2002).

Increased self-employment implies a claim on the time of working women. This claim on the labor time of women (as principal providers of unpaid care labor) leads to different possible outcomes. Earnings could be used to replace unpaid care with market substitutes (for example, daycare), or market goods (for example, more efficient stoves), which could be used to alleviate the burden of unpaid care work by enabling more effective use of care labor. The paucity of affordable good quality market substitutes in rural areas constrains the scope of such substitutions and limits the extent to which women can participate in paid employment without a squeeze on their time.

In such a situation, self-employment impinges on the time available for unpaid-care for the family and the time available for the worker herself (whether for skill-development, leisure, self-care, or rest), what we term own-care.Footnote1 While unpaid care for the family promotes overall labor productivity, the time that the woman worker claims as her own is of crucial importance to the sustenance and development of her own capabilities. A squeeze of own-care – for instance reduced sleep, rest, leisure, and skill-building – can leave the woman worker struggling to fulfill the needs of care work and market work and exact a toll on her well-being and drain her capacities and productivity. It also has a knock-on effect on the unpaid care labor that sustains and replenishes the physical, mental, and emotional capacities of other household members. A squeeze of own-care time of women workers would therefore erode labor productivity.

The implications of self-employment on decisions about time allocated to unpaid care work become even more crucial in the face of cutbacks to state provision of care. If income generated by self-employment are inadequate to sustain recourse to good quality market care or more effective care labor, then participation in the labor market would reduce the time available for care labor. In the context of the low-income households in rural areas in developing countries, the scale of income generated and the amount of own-care time available to women in households, where survival depends on unpaid subsistence work, is likely to be small.Footnote2 The scale of earnings from this sector is important, but the lack of adequate substitutes for care, especially in rural areas, must also be acknowledged.

Further, the scope for successful self-employment is also affected by the macro-environment of demand that underpins the growth of microenterprises. Even though studies point to an increase in business activity, the mere provision of credit to kickstart microenterprises does not open the door for sustainable self-employment (Bateman Citation2012). Slowdowns in the wider economy lower the demand for the output of such microenterprises affecting their viability. While the importance of decent infrastructure (including for marketing products) for the success of microenterprises has been underscored (Marr Citation2012), there has been a relative neglect of their linkages with wider macroeconomy. Since the enterprises are small in scale and there is typically a replication of products and services among microenterprises in a particular region, prices and earnings tend to get squeezed due to competitive pressures. The earnings of self-employed microentrepreneurs depend on the growth of the demand for their products, which hinges on strong linkages both within and outside the local rural economy.

The structural constraints on the income-generating potential of microenterprises via self-employment thus arises on the supply side from the limits posed by responsibility of provision of care, on one hand, and the inadequacy of infrastructure and social provision of care, on the other. At the same time, aggregate demand poses a structural constraint on the transformative potential of self-employment promotion. Therefore, the growth and success of microenterprises depends crucially on the interaction between these twin constraints. The model developed in this study explores these linkages.

ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

The analytical model presented here lies within the Structuralist/Post-Keynesian tradition. The gender-inequitable biases implicit in mainstream macroeconomic approaches that Diane Elson and Nilüfer Çağatay (Citation2000) emphasize, particularly in the context of economies dominated by financial interests,Footnote3 make them unsuitable for our purpose. The Post-Keynesian approach, on the other hand, with its focus on the interconnection between demand and distribution, is a more appropriate point of departure for our purpose because it provides a framework of analysis that is amenable to studying the interaction between class distribution and gender relations.

Advances have been made in embedding gender and care work within the broad Post-Keynesian macro-economic framework (Akram-Lodi and Hanmer Citation2001; Ertürk and Çağatay Citation1995; Çagatay and Ertürk Citation2004; van Staveren Citation2010; Braunstein, van Staveren, and Tavani Citation2011; Seguino Citation2013; Braunstein, Bouhia, and Seguino Citation2020). Two-sector models within the structuralist tradition have explored the interaction of a subsistence/informal sector and a modern capitalist sector (Rada Citation2007; Thakur and Guha Citation2017). In this article, we use the dual-sector model as the point of departure to investigate the interaction between women’s self-employment, the macroeconomy, and unpaid care work.

In order to focus more sharply on the key analytical relationships that are of interest for our purpose, we elaborate a stylized two-sector model in the Post-Keynesian tradition with the sectors embodying distinct institutional features. The first sector, the wage-employment sector (henceforth wage-labor sector), is modeled along the lines of the conventional Post-Keynesian analysis with two classes: capitalists and workers, while the self-employment sector comprises microenterprises that are developed and run by self-employed workers. These enterprises are generally small in scale and predominantly consumption goods (like production and sale of garments or food products).

We further assume a gendered division of labor in the sectors – men work in the wage-labor and women work in the self-employed sector. This reflects the stylized facts in regions across the developing countries, where men in low-income households tend to work outside as wage-labor while women remain more tied to the home and home-based enterprises that allow them to continue to fulfill care responsibilities. Access to credit, for instance through microfinance allows the woman worker the opportunity for earning by setting up a microenterprise.Footnote4 She is faced with the choice of allocating her labor between paid self-employment and unpaid care (including own-care). Care labor poses a structural constraint on the capacity to undertake paid employment. It is also a critical determinant of overall labor productivity. While the household is the site where decisions about consumption and allocation of labor are made, we do not focus on the micro-level decision making of household allocation of income and labor time but are more interested in investigating macroeconomic outcomes of those decisions. We also do not explicitly differentiate a market-care sector in the present model.

The viability of the microenterprise depends on demand conditions in both sectors. We make the simplifying assumption that the goods produced in the self-employed sector (consumption goods like food products) are consumed solely by workers in both sectors. Increased wage-income in the wage-labor sector would lead to a greater demand for the self-employment sector’s output, whereas higher earnings in the self-employed sector would also stimulate demand for the wage-labor sector’s output. The wage-labor sector’s output (which encompasses a range of industrial products from household consumptions goods and consumer durables and tools and machinery) is consumed by men and women workers and capitalists. It also constitutes the investment good in both sectors. Thus, the two sectors have a mutual feedback effect on each other and the growth in one sector can stimulate demand for the product of the other sector suggesting the possibility of a benign upward trajectory in the overall income level.

The two sectors are also linked from the supply side. The self-employed sector is constituted by women workers who allocate their labor between self-employment and care labor (including own-care). Income-generating opportunities through self-employment could have an impact on how care is provided. If the scale of income is not enough to lead to increased recourse to market substitutes (and complements) there will be an erosion of care provision. This would affect labor productivity in both sectors by impacting men and women workers. The other possibility is that care labor is provided at the expense of the own-care of the woman worker, with a consequent adverse impact, specifically, on the productive capacities of the woman worker. Both these channels are explored as the model developed in the following allows us to investigate the interaction between the sectors from both demand side and supply side, through the relation between care work and labor productivity.

THE TWO-SECTOR MODEL

We use the subscripts wl and se for the wage-labor and self-employed sectors respectively. We assume that enterprises in the self-employment sector cannot achieve economies of scale, and therefore labor productivity in this sector is likely to be lower than that of the wage-labor sector. While we do not construct micro-level behavioral models of the allocation of labor between unpaid care work and self-employment and paid work, or of consumption between the two sectors, the parameters defining allocative shares reflect these micro-level decisions.

The sectors

The wage-labor sector is modeled with two classes: capitalists and workers. We assume that only male workers have access to wage employment. Income in this sector, , is distributed between the two classes as wages

and profits

,

(1)

(1)

Capitalist profit is given by

, where

= profit share.

Total wage income of the (male) worker is given by

(2)

(2)

where w denotes the wage

, labor productivity in the wage-labor sector, and

the labor employed in the wage-labor sector.

The self-employed sector, on the other hand, is constituted solely by self-employed women workers.Footnote5 The self-employed sector’s income (Ese) is their revenues in excess of interest costs (ignoring other costs for expositional purposes), and can be represented as:

(3)

(3)

where pse is the price of the output of this sector,

is borrowings, and

the interest rate. The quantum of borrowing and the interest rate is treated as exogenous, and interest cost is a leakage in this model.

Determinants of demand in the two sectors

The dynamics of adjustment are modeled in a distinct way for each of these sectors. The wage-labor sector is modeled along standard Post-Keynesian lines as output adjusting to excess demand. Prices are determined as a mark-up over variable costs. In the self-employed sector, in contrast, we assume prices are demand driven and adjusts to excess demand. The intuition is that in the wage-labor sector, the capitalist employer adjusts output in accordance with variations in demand, while in the self-employment sector the price at which their products are sold adjusts according to the demand conditions.

To determine the aggregate demand in the economy we make certain simplifying assumptions.

The male worker employed in the wage-labor sector does not save and spends a share

of his income on the wage-labor sector good and

on the self-employed sector good. Thus, the male worker demand for the wage-labor sector output is

, and that for self-employed sector output,

. We assume that the capitalist in the wage-labor sector saves

proportion of the profits and spends the rest

on wage-labor sector output, to simplify the exposition.

The woman worker in the self-employed sector saves

of her income. Of the remainder, she spends a proportion

on the wage-labor sector output and

on the self-employed sector output. The woman worker thus spends

on wage-labor sector output, and

on self-employed sector output.

The assumption that the male worker does not save is a carryover from the original Kaleckian model and is a stylized representation of the relatively lower capacity of workers to save out of wages. The assumption that self-employed woman worker saves, reflects her role as a self-employed worker who reinvests her savings to expand her production within the self-employed sector (see Equation 5 below).Footnote6 The extent to which the self-employed woman worker bears the responsibility for providing care affects the amount that she saves. Increased earnings allow some substitution of unpaid care labor with market care goods. Thus, increased employment need not involve a diminution of the provision of “care,” but rather its transformation from a non-market to a market form. However, at the margin, there is a trade-off between earnings and the cost (and adequacy) of market substitutes as the worker choses between market and non-market forms of production and savings (van Staveren Citation2002). In this context, it has also been argued that microfinance is a mechanism for saving, where the large one-time spending enabled by microfinance is then paid back by restricting consumption (Banerjee Citation2013). But the borrower could also fall into a low-savings trap, where low-income and the compulsion of debt repayment, make it impossible to save. The constraint on savings is reflected in the empirical findings of the lack of investment growth in this sector.Footnote7

The literature on the gendered pattern of consumption suggests that male workers are likely to spend a larger share of their income on capital-intensive and luxury goods that are produced in the wage-labor sector, underpins the assumption that in the model.

The investment goods demanded by both sectors are produced in the wage-labor sector. Investment demand (real) in the wage-labor sector is given by

(4)

(4)

the conventional Kaleckian investment demand function where α represents animal spirits, and

and

represents the responsiveness of investment to output and the profit-share respectively. Investment varies directly with output (capacity utilization) profit share and animal spirits.

Investment demand in the self-employed sector on the other hand is given by

(5)

(5)

where

is the savings rate out of net earningsFootnote8 and

represents exogenous availability of credit through financial inclusion-related schemes, for example, cash transfer schemes or microfinance schemes. Investment in this sector conforms to the Classical model in the sense that it is determined by the reinvestment of savings (after interest payments on existing loans) and the quantum of new injection of funds.Footnote9 We do not explicitly consider the term of the loan in the present analysis.

The total (real) demand for the wage-labor capitalist sector output is:

(6)

(6)

On the right hand side, the first term represents consumption demand of the self-employed worker, the second term represents the investment demand in the wage-labor sector, the third and the fourth terms represent the consumption demand of the wage-labor sector worker and capitalist respectively and the last term represents the investment demand in the wage-labor sector.

The total (real) demand for self-employed sector is given by:

(7)

(7)

On the right-hand side of (7), the first term and the second term denote consumption demand of the self-employed workers and the wage-labor sector workers, respectively.

The model allows us to highlight the demand interlinkages between the two sectors. Specifically, it follows from (7) that for the self-employed sector to be in equilibrium the positive impact of the consumption demand from the wage-labor sector should outweigh the demand leakages in the self-employed sector, that is, via savings.

However, there is another crucial aspect that is often missed in the genre of two-sector models – that of the role of women’s time allocation between care work and market work, which impacts both the sectors and the interaction between the sectors. Since the woman worker in the self-employment sector is also the principal provider of unpaid care labor, her time allocation between care work and market worker has implications to both the sectors. For instance, higher demand from the wage-labor sector for the self-employment sectors’ products would increase the women workers’ labor time for paid self-employment at the expense of unpaid care labor time. The resulting time squeeze for women workers in terms of their market labor time decreases their productivity, and thus output and earnings of the self-employment sector. The adverse impact of the time squeeze of the women workers’ market labor time may outweigh the prospect of higher earnings brought about the positive demand shock from the wage-labor sector. Therefore, the intersectoral analysis is not complete without considering the time constraint faced by the woman self-employed worker who bears the primary responsibility for care work.

Care work and the self-employment sector

We extend the two-sector model to investigate the consequences of how the woman worker allocates her time between unpaid care and paid self-employment. The extended model will allow the incorporation of the impact of care labor on the labor capacities and capabilities of both men and women workers.

We assume a gendered division of labor where the self-employed woman worker is also the principal provider of both direct and indirect care. Unpaid subsistence production is included within the unpaid care labor since it contributes to the material needs of both men and women workers. The own-care time left after self-employment and unpaid care work could be spent be spent on leisure activities, rest, or some form of self-care. The time squeeze, as women workers increase their participation in paid employment, is a significant dimension of how self-employment exacerbates the pressure on the own-care time of the self-employed worker, with detrimental effects on her productivity and well-being.

The woman worker, thus, allocates her time between market-oriented self-employment (), unpaid care work (

), and own-care time (

). The allocation of a quantum of total labor,

, between these activities is an outcome of a complex process of decision making that reflects both intrahousehold bargaining and social norms in a patriarchal society that place a disproportionate burden of care responsibility on women. We abstract from the actual decision making process and focus on the stylized aggregate outcomes of particular configurations of time allocation. The fixed supply of total female-labor

, would be allocated to self-employment, unpaid care work, and time for own-care as

(8)

(8)

We further postulate that

(9)

(9)

(10)

(10)

The behavioral parameters , and

, are the aggregate share of total female labor allocated to unpaid care work and own-care respectively. The choice between spending time on earning through self-employment

, unpaid care work

, and own-care

can now be seen as

(11)

(11)

While the linear formulation above is a simplification, it suffices to capture the essence of the trade-off between unpaid care work, own-time, and self-employment. It is important to recognize that while both self-employment and unpaid care labor could increase at the expense of own-care labor time, there is a limit as to how much own-care can be squeezed without deep damage to the capacities and capabilities of the woman worker.

We assume that the labor productivity in the self-employed sector is lower than that of the wage-labor sector

in large part because the size of the microenterprises preempts the benefits of economies of scale. Letting

to denote the ratio of productivity in the self-employed sector to that in the wage-labor sector and the relative productivity between the sectors is expressed as,

(12)

(12)

The parameter

would be governed by the technological differences between the two sectors and by social norms that shape the gendered evolution of labor productivity. Of significance for our purpose is how the parameter

gets affected by the relative changes in the time allocation between self-employment, unpaid care, and own-care by women.

Consider a rise in self-employment at the expense of own-care, leaving time spent on unpaid care unchanged. The reduction in own-care – time for rest and leisure – would erode productivity of the woman worker in the self-employed sector. Since productivity in the wage-labor is unchanged, relative productivity of the self-employed woman worker falls.Footnote10 This means that the relative productivity parameter is an increasing function of own-care time. So, while the decrease in women workers’ own-care, at any given level of unpaid care, allows more time for self-employment, productivity in the self-employed sector

would fall.

Thus, time allocation between the competing needs of unpaid care, own-care, and self-employment impacts the relative labor productivity between the two sectors, and the dynamics of interaction between these sectors from the supply side. We can now rearticulate the interrelation between the two sectors developed in the previous section to study how changes in the women’s time allocation impact the dynamic interaction between them and thereby result in different macroeconomic outcomes. Using the time allocation decision (11) and the relative productivity relation (12), the self-employed sector output is given by

(13)

(13)

and substituting (13) in (6) and (7) we can analyze how the allocation of women’s time between self-employment and care labor impacts and is impacted by the demand linkages between the sectors.

INTERSECTORAL LINKAGES AND ADJUSTMENT

We assume, as noted above, that the wage-labor sector output adjusts to excess demand as in the standard Post-Keynesian model, such that in equilibrium the rate of change of output is given by:

This equilibrium relation is denoted by WL. Substituting

from (6) and simplifying yields

(14)

(14)

In the self-employed sector, in contrast, price adjusts to excess demand such that in equilibrium, the rate of change of price is given by:

We denote this equilibrium relation by SE. Substituting

from (7) and

from (13), and simplifying yields

(15)

(15)

Equations 14 and 15 constitute our dynamical system to study the interrelation between the two sectors. We use the WL and SE curves to study the adjustment dynamics of this system at and around the equilibrium in the space. Their intersection gives us the macroeconomic equilibrium

values.Footnote11

The slope of WL curve in the space is given by

(16)

(16)

The numerator is positive and the Keynesian stability condition (that requires savings to be more responsive than investment to a change in output) ensures the positivity of the denominator, so that the slope of WL curve in the

space is positive (see Appendix for formal derivation). This means that a rise in price of the self-employed sector output, and the consequent increase in earnings, raises equilibrium output in wage-labor sector as a result of an increase in demand for latter.

On the other hand, given the Keynesian stability condition, an increase in the self-employment sector’s output raises demand in the wage-labor sector (Equation 6) and its output expands, shifting the WL curve outwards as,

(17)

(17)

But the increase in the self-employment sector’s output is driven by women’s (lower) time allocation for unpaid care work

and their own-care time

, and through the relative labor productivity parameter

. Thus, women’s time allocation ultimately influences the shifts in the WL curve through its impact on output

of the self-employment sector as we will see in the next section.

Turning to the self-employed sector, the slope of the SE curve in the space is given by

(18)

(18)

Since both the numerator and the denominator of (18) are positive, the slope of the SE curve in the

space is positive, which means that an increase in the wage-employment sector’s output increases the equilibrium price of the self-employment sector, as demand rises. On the other hand, an increase in self-employment sector output shifts the SE curve downwards as given by

(19)

(19)

The intuition is that for a meaningful equilibrium to exist in the self-employed sector demand for its products from the wage-labor sector must be greater than the leakage of demand owing to interest payments (see footnote 10), which makes . Or in other words, for a given level of demand from the wage-labor sector, an increase in

will result in excess supply and consequently a fall in its price pse.

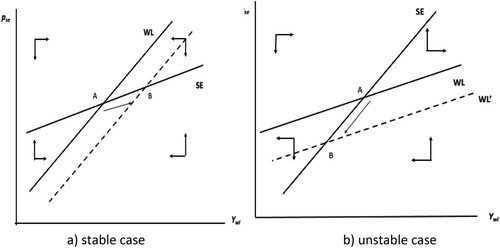

The stability of the equilibrium boils down to the condition that the responsiveness of demand for the wage-labor sector’s output in the self-employed sector must be greater than the responsiveness of the wage-labor sector demand to the self-employed sector output (see Appendix for details). In other words, the elasticity of the self-employed sector price to wage-labor sector output must be greater than that of the wage-labor sector output to self-employed sector price. This asymmetry reflects the structural primacy of the wage-labor sector, even though the two sectors are interdependent. It also suggests that policies that stimulate the wage-labor sector would have a positive impact on the earnings in the self-employed sector. Exogenous shocks that depress demand in the wage-labor sector would, conversely, also depress earnings in the self-employed sector. Figure presents these adjustment dynamics of our model for both cases. The arrows in the figure indicate the motion towards or away from the equilibrium point.

While the above analysis of the intersectoral demand dynamics might seem obvious for those who are familiar with the Post-Keynesian two-sector models, it serves to contextualize the macroeconomic demand constraint faced by the self-employment sector. The novel contribution of the model lies in the fact that it brings out how the equilibrium adjustment dynamics between the wage-labor (WL) and the self-employed (SE) sectors are mediated through women’s time allocation between unpaid care work and paid market work.

Using the model (Equations 14 and 15), we can also study the impact of exogeneous expansions of production in the self-employment sector as a result of cash transfers or financial inclusion-related schemes (including microfinance), that is, increase in in (14). This would shift the WL curve rightwards, due to the higher demand for wage-labor sector output as given by

The SE curve, however, would not shift. From Figure we can see that the new equilibrium, as a result of an increase in Bo would be at a higher

in the case when the positive feedback from the wage employment sector is strong enough to propel the self-employment sector and the equilibrium is stable (a movement from point A to point B in Figure a). In the case where the equilibrium is unstable, the injection would lead to a lower

. This underscores the importance of stable macroeconomic conditions for the effectiveness of strategies that promote self-employment through credit provisioning. An increase in

has a positive impact on both sectors only under the conditions of stable macroeconomic adjustment. This finding is significant as it clarifies the limitations of financial inclusion initiatives that are exclusively focused on the lack of access to credit as the most important constraint for self-employment. Intersectoral demand linkages determine the viability of the strategy of fostering self-employment through the provision of credit.

We now turn to a comparative static analysis of the impact of changes in the allocation to unpaid care and own-care time on account of an increase in women’s self-employment on the intersectoral demand dynamics, as a prelude to elucidating how responsibility for care work circumscribes the scope for self-employment on the supply side.

Impact of changes in time allocation to care

Consider the impact of an increase in time allocated to paid self-employment (lse), which can come about in three ways (see Equation 11):

a decrease in the allocation of time for unpaid care

a decrease available own-care time

a decrease in both unpaid care time

and own-care time

We will consider only the first two cases, which can be regarded as the limiting cases.

Decrease in unpaid care time

Consider a decrease in the allocation of unpaid care, as more time is spent on paid self-employment, on the impact on the wage-labor sector equilibrium:

(20)

(20)

Thus, an increase self-employment, at the expense of unpaid care-labor, generates a larger output in this sector. Since the increase in the self-employment sectors’ output expands demand for the wage-labor sector’s output, shifting the WL curve outwards (Equation 17), the rise in the equilibrium level output level in wage-labor sector is ultimately achieved by a decrease in unpaid care-labor by the women workers in the self-employed sector.

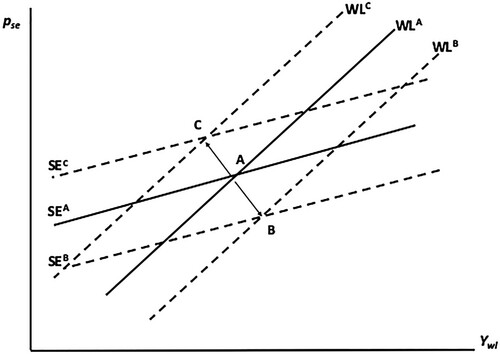

However, the impact on the equilibrium in the self-employed sector is not straight forward as

(21)

(21)

The denominator of (21) is negative. However, the necessary condition for the existence of equilibrium in the self-employed sector (Equation 19) implies that the numerator is also negative, which makes

. This means that a decrease in unpaid care-labor lowers the equilibrium price in the self-employed sector. The intuition is that an increase in self-employment through a reduction in unpaid care, increases output and leads (keeping other things constant) to an excess supply of the goods produced in the self-employed sector, and consequently depresses its equilibrium price. Thus, in terms of the overall impact, the decreased allocation to care work in the self-employment sector leads to an increase in wage-labor sector output and a fall in self-employed sector prices as shown in Figure .

Starting from the initial equilibrium (point A), the decrease in unpaid care labor leads to an increase of the wage-labor sector output resulting in the rightward shift of the WL curve. Equilibrium price in the self-employed sector falls for a given level of output, resulting in the downward shift of the SE curve. Thus, the system moves to the new equilibrium (point B), which is characterized by higher wage-labor sector equilibrium output and a lower self-employed sector equilibrium price.

Decrease in own-care time

If instead the allocation to self-employment is increased by squeezing the women workers’ own-care time , then there would be two opposing effects: on the one hand, the total employment in this sector would increase because of the reallocation from own-care to self-employment, but on the other hand the relative labor productivity

would fall because of the increase in self-employment time. The net impact on the output of the self-employment sector would depend on which of these two effects is greater. If the direct effect of increased self-employed labor time is greater than the diminished relative productivity effect, that is, the output-effect outweighs the price-effect, the squeeze on own-care time will lead to a net increase in output in the self-employed sector.Footnote12 This would raise the equilibrium output of the wage-labor sector resulting an outward shift of the WL curve. At the same time, the equilibrium price in the self-employed sector would fall, resulting in a downward shift of the SE curve, so that the new equilibrium would be at a point B. On the contrary, if the positive employment effect is outweighed by the negative productivity effect, output in the self-employed sector falls leading to an inward shift in the WL and upward shift of the SE curve, which is shown in the movement from the initial equilibrium A to the new equilibrium C in Figure . More generally, in addition to the immediate impact, the squeeze on own-care time would also have longer term effects on the efficacy of the unpaid care provided by the women workers and thus would also impact productivity of male wage-labor

.

Care work and labor productivity

One of the limitations with the preceding analysis is that it neglects the feedback, between unpaid care work and market labor productivity. For instance, our model does not take into account cases where an increased allocation of unpaid care labor can have a positive impact on labor productivity.Footnote13 In order to further explore this feedback, we now consider the inter-relation between care work and labor productivity in a general model, that focuses only on the supply-side interactions, abstracting from the demand-side interactions.

Labor productivity in both sectors is determined by a range of factors, though labor productivity in the self-employment sector is lower by the scale . Higher wages

in the wage-labor sector and higher earnings in the self-employed sector

can positively influence labor productivity of both men and women workers since they allow the substitution of unpaid care by market care and purchase of goods that can improve productivity of unpaid care labor.Footnote14 The allocation of incomes (whether from market employment or from self-employment) on the purchase of care goods and services would be subject to intrahousehold bargaining and the structures and norms of social provisioning of care. As noted above, the increased time-allocation to care labor would have a positive impact on labor productivity, but whether the increase allocation is due to a decrease in self-employment or own-labor time does matter.Footnote15 Furthermore, the social provision of care

, such as public hospitals and creches, and the level of public and private capital investment

, such as tools and equipment, tube-wells, canals, public transport, and electricity would also increase productivity. Taking all these factors into account,Footnote16 labor productivity can be specified in general as

(22)

(22)

where

.

The allocation of labor to unpaid care work, represented by the parameter in (22), is also determined by a range of factors. First, it depends inversely on both earnings in the self-employed sector, and wages in the wage-labor sector, since with higher earnings unpaid care could be substituted by market products. However, the relative weights of these impacts would depend on intrahousehold bargaining. Second, an increase in the interest-rate burden would lead to an increased allocation to care, as unpaid labor compensates for market care as spending is squeezed to meet the higher interest payments. Third, increase in labor productivity

would reduce unpaid care through its effect in raising men’s and women’s earnings. And an increase in the ratio of relative labor productivity

would also enable a reduction in allocation to unpaid care, by increasing women’s earnings. Finally, the social provision of care

would reduce the burden of unpaid care work and can be thought of as an exogenous shift parameter. Thus, the time allocation for unpaid care labor would then depend on

(23)

(23)

where

.

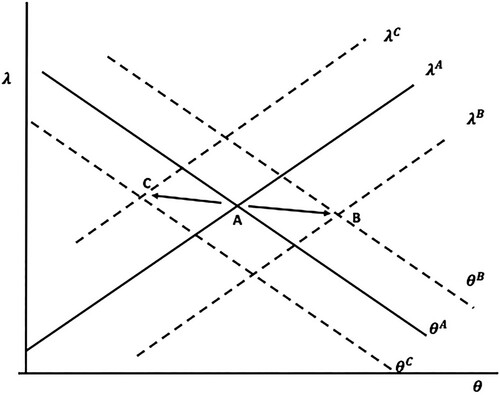

We present a graphical analysis of the interaction between labor productivity and the allocation of women’s labor to unpaid care work in Figure .Footnote17

In the general model described by (22) and (23), the intersection of the labor productivity and the care-allocation

schedules represents the equilibrium outcome

of their interaction.Footnote18 Now consider a fall in self-employed sector earnings on both these variables. Starting from point A, a fall in earnings would shift the labor-productivity schedule downwards and care-allocation schedule upwards resulting in the new equilibrium outcome at point B, where there is an unambiguous increase in the burden of unpaid care work that would squeeze the labor time of women workers. Note that in the new equilibrium at point B in Figure , labor productivity remains unchanged but this depends purely on the relative shifts in the two curves. In this case, in Figure , the relative shifts are such that labor productivity remains unchanged.

In contrast, an increase in earnings in the self-employed sector, due to policy interventions that boost demand or buttress the interlinkages between the two sectors, would shift the labor-productivity schedule upwards, and also shift care-allocation schedule downwards to point C, so that the burden of care work is reduced. This implies that the increase in earnings can lead to a reduced allocation to unpaid care. However, this would depend on relative magnitudes of shifts in these two curves. While the impact of the shift of the productivity schedule may be more direct, the impact of access to self-employment opportunities on the asymmetric, gendered division of care responsibilities is, however, less clear cut.

On the other hand, any reduction in the public provision of social care , owing to neoliberal policy imperatives, would shift the care-allocation schedule rightwards, such that a higher burden of unpaid care would be necessary to absorb adverse effects of the spending cuts. The overall impact would then depend on how the increased allocation for unpaid care comes about. If the increase in care labor is at the expense of paid self-employment then demand would be depressed, and lower earnings would further exacerbate the burden of unpaid care work. And if the increased allocation to care is achieved by squeezing on the own-care, this would lead to an increased productivity gap between the two sectors, as the capacities of the woman worker are adversely impacted. The cutback on the social provision of care also pushes the productivity schedule downwards, implying a reduction in labor productivity (unless the impact is compensated by an increase in unpaid care leaving it unchanged), so that the labor-productivity schedule shifts downwards and the equilibrium outcome shifts from A to B. The system would tend an equilibrium with higher burden of care work and at a lower level of productivity.

The admittedly schematic analysis of the interaction of care work and labor productivity suggests that the scope and effectiveness of developmental strategies that focuses on promoting self-employment need to be comprehended with more nuance. We show, analytically, that for this strategy to be viable it needs to go beyond focusing on financial inclusion initiatives based on the argument that availability of credit is the principal binding constraint, and instead encompass policies that strengthen linkages of this sector with the wider economy including policies for the social provision of care that would relieve the constraints that unpaid care responsibilities imposes on women’s self-employment.

CONCLUSION

In this article we present a simple model that integrates the non-market provision of care and the role of aggregate demand in a two-sector model. The contribution of the article lies in the use of the Post-Keynesian workhorse two-sector model to shed light on the constraints faced by policies to promote self-employment of women in developing countries. Self-employment as a developmental strategy faces dual constraints – from macroeconomic conditions represented by the wage-labor sector on the demand side and from the competing claims on women’s time between self-employment and unpaid care work (including own-care) on the supply side. The model demonstrates that a stable macroeconomy in terms of the interlinkages between the sectors is necessary for the self-employment strategies to be viable. But this is not sufficient. As the model highlights, unless the implications of the interrelation between unpaid care and labor productivity are considered together with the aggregate demand imperatives, the viability of the developmental strategy based on women’s self-employment may not be guaranteed. While higher women’s earnings can alleviate the burden of care by making care work more effective and by enabling the market to substitute for unpaid care, at low-income levels in a context of “a low road” regime of care (Braunstein, Bouhia, and Seguino Citation2020), the gendered responsibility for care remains a critical constraint for women’s self-employment. Further, the home-based nature of microenterprises would tend to perpetuate the gendered asymmetries of care responsibility within the household. There is thus a contradiction, arising from the dual constraints highlighted in analytical model presented in this article, inherent in a development strategy that overlooks the gendered division of care work responsibilities that are imposed on the self-employed woman entrepreneur-worker.

Paradoxically, the strategy of harnessing entrepreneurial possibilities of women’s self-employment by adopting financial inclusion as a development policy, has been espoused precisely in the period when the role of the developmental state has been eclipsed, and cutbacks in public spending have been prescribed. This article injects a note of caution and suggests that the success of such a developmental strategy depends crucially on wider policies that support both demand and the social provision of care. It is not surprising that neoliberal policy prescriptions that promote self-employment, with a narrow and misplaced emphasis on credit provisioning rather than care provisioning, have had a limited impact on improving women’s livelihood and as a sustainable development strategy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge feedback and comments from Elissa Braunstein, Diane Elson, Maria Floro, Stephanie Seguino, organizers and participants at the Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM) workshop, the Eastern Economists Association conference panel, and the anonymous referees of the journal.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ramaa Vasudevan

Ramaa Vasudevan is Professor at the Department of Economics, Colorado State University. Her main research interests are the political economy of money and finance, the workings and evolution of international financial systems, and open economy macroeconomics. Vasudevan is the author of Things Fall Apart: From the Crash of 2008 to the Great Slump. She is an Associate Editor of Review of Political Economy and a member of the Editorial Board of Catalyst.

Srinivas Raghavendra

Srinivas Raghavendra is Lecturer of Economics at the National University of Ireland, Galway. His current research is focused on a number of themes in the areas of Macroeconomics, Finance, and Political Economy. His work has been published in some of the leading peer-reviewed international journals including Review of Keynesian Economics, Metroeconomica, Journal of Economics, Feminist Economics, Panoeconomicus, Review of Development and Change, PLoS ONE, European Physics Journal B, and IEEE, among others.

Notes

1 We will use the term own-care in the rest of the text rather than self-care.

2 Rural economies characterized by limited and low-quality market care goods, and poor social infrastructure and provisioning of care make what Elissa Braunstein, Rachid Bouhia, and Stephanie Seguino (Citation2020) characterize as the low-road regime of social reproduction, that is, of the organization of resources and labor to produce, sustain, and develop human capacities.

3 These are the deflationary-bias, the breadwinner-bias, and the commodification-bias. The emphasis on austerity depresses wages and employment at the same time when the state is cutting back on social spending and privatizing health, education, and other social sectors. The women are forced to take on a relatively larger burden of unpaid care work in order to compensate for deteriorating livelihoods.

4 We ignore leakages of loans to smooth consumption. Evaluations of microfinance schemes have not provided much evidence to suggest an increase in consumption following access to microcredit (Banerjee Citation2013; Banerjee, Karlan, and Zinman Citation2015).

5 The restrictive assumption that the female worker does not enter the wage-labor market reflects the greater barriers to wage employment faced by women in those economies. The opportunity for self-employment assumes significance in this context.

6 Savings are of also undertaken to ensure future financial security for the household, especially children or to secure household assets. We are abstracting from these aspects in the model.

7 There is evidence in developing countries, that as women’s discretionary income and bargaining power increase, aggregate saving rates rise, implying a significant effect of gender on aggregate savings (Seguino and Floro Citation2013). There are however contradictory impacts of a rise in female earnings on savings. On the one hand, the greater responsibility for providing care might result in lower savings, for instance due to greater investment in education of children. On the other hand, women may be motivated to save in order to better provide for the security of the family. Relative bargaining power within the household and control over earnings would also affect women’s savings behavior (including the forms in which savings are undertaken). The present model does not address this issue.

8 The determinants of are not explored in this article, but this variable is crucial to the adjustments made by the female worker, in a context where the female worker is the principal provider of unpaid care labor.

9 The interest on accrues in the subsequent periods in this model. In general,

can represent any exogenous injections such as cash or income transfers.

10 Since when the own-care time

is squeezed as self-employment increases, the self-employed sector productivity

falls for a given level of output.

11 Note:

Since the denominator is negative, the positivity of

is guaranteed by

. that is, in equilibrium, the demand for the self-employed sector’s products by the wage-labor sector must be greater than the leakages in the self-employed sector arising due to interest payments.

12 This follows from the expressions:

and

where

If the productivity effect is greater, that is:

then

and

. Conversely if the employment effect is greater, that is:

the signs are reversed.

13 The approach here is to associate the impact of care labor on market labor productivity as a way of capturing the role of care work in the reproduction and development of human capacities. It is also possible to think of the impact of care labor in maintaining or expanding the amount of labor supplied to the market.

14 The quality and range of market care is an important consideration which would influence both participation in the paid employment and the impact of increased spending on such goods on labor productivity. We do not allocate market care to either sector, specifically.

15 Note that The first term is the impact of a reduction in earnings due to the reallocation of labor from self-employment to unpaid care. The second term is the direct impact of increased allocation to care on productivity. The increased allocation to care would reduce earnings, through lower paid employment, and therefore also reduce spending on market-substitutes for care. For

the positive impact of care labor on labor productivity must be greater than the negative impact of reduced earnings on labor productivity. This is the case considered here. Further, note that if the increased allocation to unpaid care work is the result of cutting back on own-care time

we could plausibly expect that the ratio of relative labor productivity

to fall. The squeeze of own-care time of the female worker would then reduce female-worker productivity (relative to male-worker productivity), even if

is unchanged.

16 Note that this is the general case where unpaid care work affects labor productivity in both sectors. It also determines the availability of labor for self-employment.

17 The functions (22) and (23) are likely to be non-linear. Increases in allocation of care labor would have a greater impact on productivity when the allocation is at a lower level compared to higher levels. Conversely the reduction time allocated to unpaid care with an increase in labor productivity would be smaller at higher levels of labor productivity compared to that at lower levels of labor productivity. However, the linear representation of the two functions does not diminish the analytical conclusions in any significant way.

18 A linear adjustment mechanism at and around the equilibrium can be represented as: and

where

represent the equilibrium values.

REFERENCES

- Akram-Lodi, A. Haroon and Lucia C. Hanmer. 2001. “Ghosts in the Machine: A Post-Keynesian Analysis of Gender Relations, Households and the Macroeconomy.” In Frontiers in the Economics of Gender, edited by Francesca Bettio, and Alina Verashchagina, 93–114. London: Routledge.

- Banerjee, Abhijit and Esther Duflo. 2011. Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty. New York: Public Affairs.

- Banerjee, Abhijit, Dean Karlan, and Jonathan Zinman. 2015. “Six Randomized Evaluations of Microcredit: Introduction and Further Steps.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7(1): 1–21.

- Banerjee, Abhijit. 2013. “Microcredit Under the Microscope: What Have We Learned in the Past Two Decades and What Do We Need to Know?” Annual Review of Economics 5: 487–519.

- Bateman, Milford. 2012. “The Role of Microfinance in Contemporary Rural Development Finance Policy and Practice: Imposing Neoliberalism as ‘Best Practice.’” Journal of Agrarian Change 12(4): 587–600.

- Bateman, Milford and Ha-Joon Chang. 2012. “Microfinance and the Illusion of Development: From Hubris to Nemesis in Thirty Years.” World Economic Review 1(1): 13–36.

- Braunstein, Elissa, Rachid Bouhia, and Stephanie Seguino. 2020. “Social Reproduction, Gender Equality and Economic Growth.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 44(1): 129–56.

- Braunstein, Elissa, Irene van Staveren, and Daniele Tavani. 2011. “Embedding Care and Unpaid Work in Macroeconomic Modelling: A Structuralist Approach.” Feminist Economics 17(4): 5–31.

- Çagatay, Nilüfer and Korkut Ertürk. 2004. “Gender and Globalization: A Macroeconomic Perspective.” Working Paper 19. ILO Policy Integration Department, World Commission on the Social Dimension of Globalization, Geneva.

- Chen, Martha, Joann Vanek, Francie Lund, James Heintz, Renana Jhabvala, and Christine Bonner. 2005. Progress of the World’s Women 2005: Women, Work, and Poverty. New York: UNIFEM.

- dos Santos, Paulo L. and Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven. 2017. “Better Than Cash, But Beware the Costs: Electronic Payments System and Financial Inclusion in Developing Economies.” Development and Change 48(2): 20–227.

- Ehlers, Tracy Bachrach and Karen Main. 1998. “Women and the False Promise of Microenterprise.” Gender and Society 12(4): 1–13.

- Elson, Diane and Nilüfer Çağatay. 2000. “The Social Content of Macroeconomic Policies.” World Development 28(7): 1347–64.

- Ertürk, Korkut and Nilüfer Çağatay. 1995. “Macroeconomic Consequences of Cyclical and Secular Changes in Feminization: An Experiment at Gendered Macromodeling.” World Development 23(11): 1969–77.

- Gindling, T. H. and David Newhouse. 2014. “Self-Employment in the Developing World.” World Development 56(C): 313–31.

- Goetz, Anne Marie and Rina Sen Gupta. 1996. “Who Takes Credit? Gender Power and Control Over Loan Use in Rural Credit Programs in Bangladesh.” World Development 24(1): 45–63.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2020. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2020. Geneva: ILO.

- Kabeer, Naila. 2002. “Conflicts Over Credit: Re-Evaluating the Empowerment Potential of Loans to Women in Bangladesh.” World Development 29(1): 63–84.

- Loayza, Norman V. and Jamele Rigolini. 2011. “Informal Employment: Safety Net or Economic Engine?” World Development 39(9): 1503–15.

- Margolis, David. 2014. “By Choice and by Necessity: Entrepreneurship and Self-Employment in the Developing World.” European Journal of Development Research 26(4): 419–36.

- Marr, Ana. 2012. “Effectiveness of Rural Microfinance: What We Know and What We Need to Know.” Journal of Agrarian Change 12(4): 555–63.

- Rada, Codrina. 2007. “Stagnation or Transformation of a Dual Economy Through Endogenous Productivity Growth.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 31(5): 711–40.

- Robinson, Marguerite S. 2001. The Microfinance Revolution: Sustainable Finance for the Poor. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Seguino, Stephanie. 2013. “From Micro-Level Gender Relations to the Macro Economy and Back Again.” In Handbook of Research on Gender and Economic Life, edited by Deborah M. Figart and Tonia L. Warnecke, 325–44. Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- Stephanie, Seguino and Maria Floro. 2003. “Does Gender Have any Effect on Aggregate Savings? An Empirical Analysis.” International Review of Applied Economics 17(2): 147–66.

- Taylor, Marcus. 2010. “The Antinomies of ‘Financial Inclusion’: Debt, Distress and the Workings of Indian Microfinance.” Journal of Agrarian Change 12(4): 601–10.

- Thakur, Gogol Mitra and Subrata Guha. 2017. “Petty Services, Profit-Led Growth and Rural–Urban Migration in a Developing Economy.” Metroeconomica 70(1): 144–71.

- van Staveren, Irene. 2002. “Global Finance and Gender.” In Civil Society and Global Finance, edited by J. A. Scholte, and A. Schnabel, 228–46. London: Routledge.

- van Staveren, Irene.. 2010. “Post-Keynesianism Meets Feminist Economics.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34(6): 1123–44.

- World Bank. 2008. “Finance for All? Policies and Pitfalls in Expanding Access.” World Bank Policy Research Report, August. World Bank, Washington, DC.

APPENDIX

Keynesian stability condition:

In the wage-labor sector, the Keynesian stability condition , which ensures deviations from the equilibrium are self-correcting, reduces to

This is the usual Keynesian stability condition that saving responds more than investment as the sectoral output expands, so that the demand is generated is less than the expansion of output.

Writing the demand for wage-labor sector as the sum of the demand in the two sectors, the equilibrium condition is

where Di is demand in i sector.

The demand gap is given by

represents the demand gap (reflecting an excess supply of the product with respect to own sector demand) for the wage-labor sector output.

This implies that

Thus, the condition for Keynesian stability corresponds to the condition that the demand gap for the wage-labor sector output increases with the level its output. In a one sector model, with the worker consuming spending the entire wage (b = 1), this condition reduces to

.

Analogously, the stability condition for the self-employed sector, , holds if

. This stability condition is always satisfied as

. This ensures that the demand generated is less than the expansion of output.

The dynamical system:

To investigate the stability of the dynamical system we evaluate the Jacobian, that is, matrix of partial derivatives of the system around the equilibrium steady-state , where

The Jacobian of the dynamical system evaluated at the steady state , is given by:

The stability condition requires that the trace of the Jacobian is negative and the determinant to be positive.

For the trace to be negative, since , the following condition should the satisfied,

, which is nothing but the Keynesian stability condition.

The sign of the determinant (D) depends on the following condition

The system is stable

if the response of savings in the wage-labor sector

is more than investment

for any increase in sectoral income. The stability condition

also implies that the wage-labor sector’s equilibrium curve,

should be steeper than that of the self-employed sector,

in the

space. From Equations 16 and 18, this condition can be expressed as