?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Population aging in developed and developing economies has led to increasing number of older persons in need of care, posing a challenge to the social arrangements of care and creating important aggregate economic implications. This article proposes a simple theoretical framework to evaluate the interplay of gender norms and the gender wage gap, as well as specific characteristics of the paid care market such as occupational segregation and market power rents. By incorporating a degree of substitutability between women’s and men’s care work, the model shows how declines in the gender wage gap have small effects on the division of long-term care work in the presence of persistent gender norms. The study also shows that market power dynamics, in conjunction with gender norms, perpetuate reliance on women’s provision of unpaid care. The model has important implications for policies promoting gender-egalitarian household division of labor and affordable access to quality long-term care.

HIGHLIGHTS

The market logic of the paid care service sector must be analyzed in conjunction with gender norms.

A declining gender wage gap does not translate to more equal sharing of long-term care work due to persistent traditional gender norms.

Social norms shape the response of the distribution of care work to changes in market prices and perpetuate reliance on women’s unpaid care.

Gender-aware policies should encourage egalitarian social norms to reduce women’s unpaid care burden.

INTRODUCTION

Populations around the world are aging, albeit at varied pace, and the increasing demand for long-term care (LTC) is an imminent issue to policymakers. In addition, COVID-19 has disproportionately affected the health of the older age cohort, increasing care needs of frail older persons and further revealing the lack of proper long-term care infrastructure. A large proportion of long-term care is provided by women household members due to the gender gap in wages and labor force participation and its interaction with persistent gender norms.

Evidence suggests that gender norms around household division of labor can persist, regardless of the trends in relative wages (Bittman et al. Citation2003; Gupta Citation2007; Burda, Hamermesh, and Weil Citation2013; Bertrand, Kamenica, and Pan Citation2015; Lyonette and Crompton Citation2015), and therefore they also play a crucial role in shaping the nature of LTC arrangements in society. In this article, we hypothesize that the general decline in the gender wage gap has had little effect on the division of unpaid LTC work due to the persistence of traditional gender norms. To capture the effect of gender norms in care provision, we develop a tractable model with intergenerational provision of care and unequal division of unpaid care work within the household. We assume that gender norms shape the substitutability between women and men’s care inputs.

Our model studies the dynamics of unpaid LTC provision, labor supply, and paid LTC services, under the assumption that gender norms constrain the distribution of unpaid care provision. Gender norms within the household interact with the gender wage gap in the market to determine how women and men family members contribute their time to unpaid LTC and paid labor work.Footnote1 Our model explains how declines in the gender wage gap may have small effects on the division of LTC work in the presence of persistent gender norms. We suggest that this is consistent with observed trends. Our model also includes market power rents and gender-based labor market segmentation to account for other features of the care services market in a tractable manner, namely the high cost of private long-term care and the lack of quality care due to weak industry regulation, which can reinforce the reliance on family to provide LTC.

Feminist economists have long studied the role of social norms on household division of work and labor supply (Hartmann Citation1976; Beneria Citation1979; Folbre Citation1994; Bergmann Citation2005; Floro and Meurs Citation2009; Floro and Komatsu Citation2011; Sevilla-Sanz, Gimenez-Nadal, and Fernández Citation2010; Doss Citation2013; Pearse and Connell Citation2016). There have been recent efforts to include care work in a macroeconomic framework, such as the work of Elissa Braunstein, Irene van Staveren, and Daniele Tavani (Citation2011). James Heintz and Nancy Folbre (Citation2019) present a growth model with endogenous growth and fertility to account for demographic changes. Ray Miller and Neha Bairoliya (Citation2021) explore how LTC provision influences intrahousehold time and resource allocation. Our article contributes to the gender-aware macroeconomic literature that study the dynamics of gender and growth by building a tractable overlapping generations (OLG) framework that explicitly models long-term care needs in the context of gendered distribution of unpaid care and gendered labor markets.

A growing number of mainstream studies have explored the attendant consequences of the rising demand for long-term care. One strand of the recent literature studies long-term care needs as a driver of older persons’ savings behavior over the life cycle (Ameriks et al. Citation2015; Mommaerts Citation2015; Ko Citation2016; Bueren Citation2017; Lockwood Citation2018). Another strand of the literature employs general equilibrium models to examine the role of unpaid care by family members in determining the demand for long-term care (Tabata Citation2005; Kydland and Pretnar Citation2019). These studies focus on the dynamics of demand for long-term care when both paid and unpaid care options are available, but do not include any gender dimension. We believe that the persistence of gender norms may also help answer questions addressed by this literature, such as the long-term care puzzle, that is, the paradoxical trend describing the low demand for private long-term care insurance despite increasing needs for long-term care.Footnote2

The gender dimensions of long-term care, both within the household and the care market, remain largely absent in neoclassical growth models. This is a serious gap in the literature for analyzing the impact of long-term care on economic outcomes, especially when analyzing policy options. A few studies such as Oded Galor and David N. Weil (Citation1996), Nils-Petter Lagerlöf (Citation2003), Pierre-Richard Agénor and Madina Agénor (Citation2014), and Pierre-Richard Agénor (Citation2018) are a few examples of studies that incorporate a specific gender dimension to the study of the long-run dynamics. To the best of our knowledge, Francesca Barigozzi, Helmuth Cremer, and Kerstin Roeder (Citation2017) is the only study of unpaid LTC that considers the role of gender norms in a theoretical model. Different from Barigozzi, Cremer, and Roeder (Citation2017), who study how gender norms affect the costs of different long-term care arrangements in a static model, this article uses a dynamic macroeconomic approach that explains the interrelation between the observed gender wage gaps, the role of gender and care penalties in the labor market, and the intrahousehold distribution of care work. Our article can be conceived as an attempt to provide a tractable benchmark to introduce gender-biased care work in macroeconomic models.

BACKGROUND

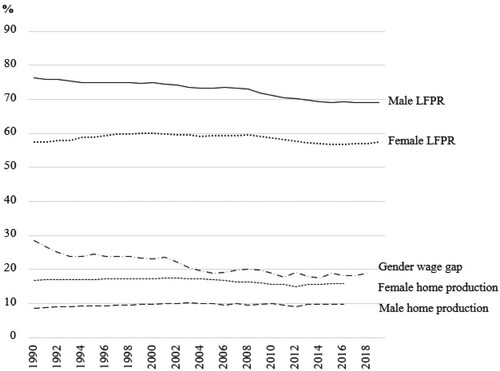

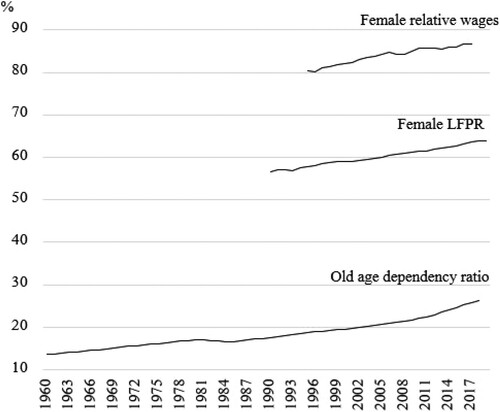

The gender wage gap has been decreasing on average since the 1960s and 1970s, but this trend has slowed or even stalled in recent decades. Globally, the gender wage gap is estimated to be around 23 percent, that is, women earn 77 percent of what men earn. Although some progress has been made in reducing the gender wage gap, the closure is far from complete. Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn (Citation2017) note that the US and other high-income countries have had a substantial reduction in the gender wage gap in the long run. depicts parallel increases in women’s relative wages and labor force participation rates on average in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.Footnote3 However, the linear aggregate trends mask the variation across countries and across economic sectors within countries as well as important trends of women’s labor force participation and home production time.

Figure 1 Long-run trends of women’s labor and aging in OECD countries (1960–2018)

Notes: Women’s relative wages are defined as the percentage of women’s median earnings relative to men’s median earnings (OECD Data). Women’s labor force participation rate is defined as the percentage of the population of women ages 15–64 that is economically active (ILOSTAT), and the old age dependency ratio is the proportion of people older than age 64 out of the working-age population (UN World Population Prospects: 2019 Revision).

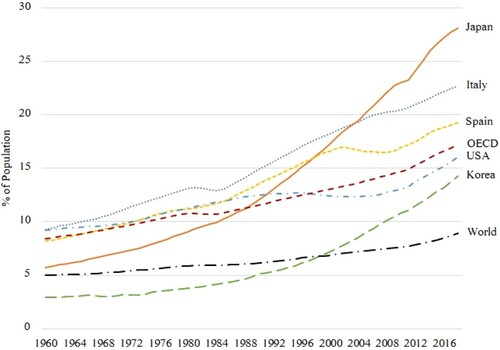

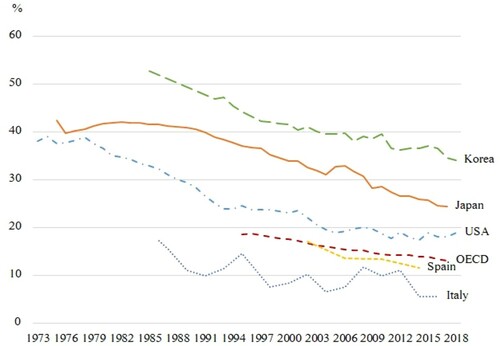

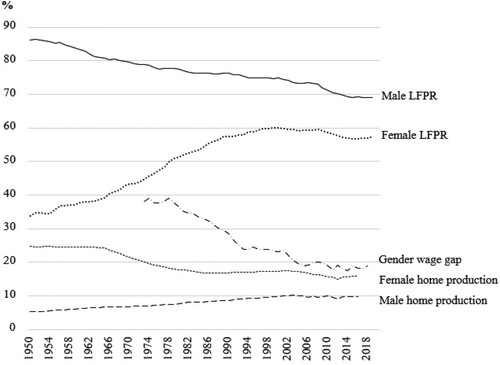

In the US, the strongest convergence of the gender wage gap occurred during the 1980s, and progress has been slower and more uneven since then. presents the long-run trends of women’s and men’s labor force participation rates and home production time in the US between 1950 and 2019. zooms in the periods from 1990 to 2019. The convergence of the gender wage gap has slowed down since 1990, and women’s labor force participation has been steady or falling since 1990. In Korea and Japan where populations are aging at fast rates (as shown in ), the gender wage gap has been declining at a slower rate compared to other OECD countries (as shown in ). Similarly, the International Labor Organization’s (ILO) Global Wage Report (Citation2018b) notes that progress in closing the gender wage gap worldwide has recently been slowing down, in spite of significant progress in women’s educational attainments and women’s higher labor market participation rates in many countries.

Figure 2 Trends in market and unpaid work and wages by gender in the US, 1950–2019

Notes: The gender wage gap is defined as the difference between the median earnings of men and of women as a proportion of the median earnings of men for full-time employees The labor force participation rates, defined as percentage of the population ages 15–64 that is economically active, were retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Home production times are in percentage of weekly hours devoted to home production.Source: OECD Data.

Analogous to the trends of the gender wage gap, household division of labor and time spent on care and housework have shown slower gender convergence in recent years.Footnote4 Among high-income countries, men’s and women’s time spent on paid and unpaid work showed some convergence between the 1960s and 1990s (World Bank Citation2011; Beneria, Berik, and Floro Citation2016; Sullivan Citation2019). However, these trends have slowed down in recent years in countries such as the US, or reversed as in the case of Australia. As shows, women continue to spend more time on unpaid domestic and care work in the US, and the trends for home production time for both genders have not changed.Footnote5

Using population weighted averages for twenty-three countries with longitudinal time-use data, the ILO (Citation2018b) finds that the gender difference in time spent on unpaid care work has only slightly narrowed. Between 1997 and 2012, population weighted averages show an almost unchanged pattern in the division of unpaid care work, with women’s unpaid care work time per day decreasing only from 4 hours and 23 min to 4 hours and 8 min. Over the same period, men’s unpaid care work on average did not increase, but instead diminished by 8 min. In fact, there has been a “levelling off” in men’s contribution to unpaid care work between the late 1990s to early 2000s and the 2009–15 period in countries such as Australia, Belgium, Canada, Japan, and the United States. An actual decline in the average contribution by men to unpaid care work has occurred in Thailand, France, Benin, South Korea, and Germany.

To understand the dynamics of long-term care and women’s labor supply, it is crucial to consider the role of gender norms. Feminist economists and gender scholars have long pointed out the influence of socially-ascribed gender roles on division of labor and the manner in which care and household responsibilities constrain women’s labor market choices (Hartmann Citation1982; Folbre Citation1986, Citation1994; Elson Citation1995). Across cultures, men are expected to be breadwinners; women are expected to be caregivers. Consequently, wives and daughters are three times more likely than sons to be primary caregivers to older parents (Bauer and Sousa-Poza Citation2015). Evidence from several studies in the US and China indicate that women devote more time to parental caregiving and are more likely to be aging parents (or parent-in-laws)’ primary caregivers compared with men (Liu, Dong, and Zheng Citation2010; Luo and Chui Citation2019; Henle et al. Citation2020).

The extent to which the gender division of care labor has changed as a result of the increase in women’s labor force participation, and more specifically, the downward trend in gender wage gap, is unclear. A few studies suggest that traditional gender roles continue to have a significant impact on household division of labor despite a half-century labor market gains by women such as the decline in the gender gap in labor force participation and the gender gap in earnings (Bittman et al. Citation2003; Gupta Citation2007). George A. Akerlof and Rachel E. Kranton (Citation2000) report that women in the US do not undertake less than half of the housework even if they work or earn more than the husband, indicating that, ceteris paribus, in couples where the wife spends more time in work outside the home, she also spends more time on chores and childcare. Marianne Bertrand, Emir Kamenica, and Jessica Pan (Citation2015) provide further evidence that the gender gap in non-market work is greater when the wife earns more than the husband, suggesting that a reduction in the gender wage gap does not necessarily change gender roles within the household. Their study contributes to the explanation of why men had not increased their housework commensurately as women moved into paid employment, and provides support for the idea that gender norms could have a more powerful influence on household division of labor than trends in relative income or earnings. While we have observed that the gender wage gap has changed relatively little in size in more recent years, the impact of the declining gender wage gap on the division of care work is even smaller.

Another type of gender inequality in the labor market is occupational segregation. Sorting and segregation across industries and occupations by gender have been documented as contributors to the gender wage gap in many parts of the world (Blau and Kahn Citation2017; Folbre and Smith Citation2017; Folbre Citation2018; Borrowman and Klasen Citation2020). Women disproportionately sort into lower-paid occupations, especially occupations in the care sector. In addition to the “gender penalty,” many care workers experience a “care pay penalty,” ranging from 4 to 40 percent of their hourly wages according to ILO (Citation2018a). Women’s LTC and childcare workers earn less on average than women workers in the non-care sectors of the economy. Care occupations are typically viewed as extensions of unpaid care work performed within households and carry low status and low pay.Footnote6 Care workers are underpaid, overworked, and endure poor working conditions. Moreover, jobs in the long-term care sector are mostly non-standard and precarious, with part-time employment being twice higher than the average rate in the economy (OECD Citation2020). The private long-term care sector has monopsony power over care workers who typically have low bargaining power (Folbre and Smith Citation2017).

Given these stylized facts, in the following section, we present a tractable model of long-term care with gender norms, occupational segregation, and care market rent. Specifically, our model recognizes the interplay of gender relations in households and labor market forces in determining the change in women’s labor force participation due to changes in women’s relative wages. The persistence of traditional gender norms in addition to prevailing gender relations in the labor market may explain the perpetuation of unequal distribution of care work. We show how gender norms can be situated in a model to study the unequal distribution of care work.

A MODEL WITH LONG-TERM CARE AND GENDER

We extend the canonical overlapping generations model with production to incorporate long-term care needs, the provision of gender-based unpaid care as well as gendered labor market and LTC service sector. We assume that there are two production sectors in the economy: a small long-term care service sector that only uses labor, and the rest of economy that uses capital and labor. For the sake of simplicity, we shall refer to the rest of the economy as the goods sector. We also assume that the labor market is characterized by occupational segregation. In particular, we assume that the external or paid care sector only employs women’s labor, while the goods sector employs women’s and men’s labor.

Households

We assume each household consists of a woman and a man. Households live for two periods: a working adult period, t, and a retired older persons period, t + 1. There are Nt working adult (or simply young) households in period t. Households receive utility from consumption and from the amount of care received by their older age relatives. Working adults can provide care to their older age relatives using their time or can purchase external paid care services.Footnote7 Women and men are economically identical and supply labor elastically in the labor market. However, there are gender norms that influence the distribution of women and men’s unpaid and paid labor time within the household.Footnote8

The lifetime utility function of a young household in period t is:

(1)

(1)

where

and

refer to household consumption in the first and second period respectively, and ht refers to the amount of effective LTC received by the generation that is old in period t. Parameter 0 < β < 1 is the time discount factor. The level of effective care ht is decided by the generation that is young in period t, but is received by the generation that is old in period t (that is, their older age parents). Hence, parameter γ represents the degree of altruism (or strength of moral obligations) of young households toward their older age relatives.Footnote9

The total level of effective LTC ht depends on unpaid family care, and external paid care services (

)

(2)

(2)

where the exponent µ ∈ [0,1] reflects that paid and unpaid care do not necessarily provide the same level of utility. If µ = 0.5, both types of care provide the same utility. If µ ∈ (0.5,1], care provided by family is preferred to care purchased in the market. If µ ∈ [0,0.5), care purchased in the market is preferred to care provided by the family.Footnote10

Thus, parameter µ can be interpreted as a social norm regarding people’s preferences for unpaid care and paid care. Functional form 2 also implies a decreasing marginal utility with respect to each type of care.

We introduce gender norms in the provision of family care using a tractable CES specification that shapes the substitutability of care work inputs by men and women. Letting stand for family care provided by the woman and

for family care provided by the man, the total production of family care

results from the following CES aggregator:

(3)

(3)

where s ∈ [0,1] and σ ∈ [0,1].Footnote11 Shares s and 1 − s are distributional reduced-form parameters and can be interpreted as the outcome of a bargaining within the young household, or can also be interpreted as the degree of filial piety or moral commitment of men and women respectively to their older age relatives. Parameter σ measures the degree of substitutability between

and

and shapes the response of the working adults to changes in their relative earnings. High substitutability (σ close to 1) indicates that the distribution of unpaid work responds strongly to changes in market incomes, whereas low substitutability (σ close to 0) indicates that the division of unpaid work is more rigid or less sensitive to such changes. This parameter is a pivotal aspect of our model. Unlike in previous growth literature, the relationship between the gender wage gap and unpaid care provided by the male and female children is not assumed to be proportional. We interpret s and σ as the level and elasticity of gender norms, respectively. Together with the gender wage gap, these parameters determine the distribution of time between men and women.Footnote12 Letting

and

denote the men’s wage rate in the goods sector, the women’s wage rate in the goods sector and the women’s wage rate in the care sector, respectively, the lifetime budget constraint of the household can be written as:

(4)

(4)

where qt refers to the relative price of market care and rt+1 stands for the return to savings in period t + 1. Parameters ϕ and 1 − ϕ are the fractions of women’s labor employed in the goods and paid care labor markets, respectively. Note that, for simplicity, Equation 4 abstracts from leisure time, by assuming that all the time that is not devoted to work is employed to carry out unpaid care tasks. The inclusion of leisure in the model would not change the main results for the purpose of our analysis.

External long-term care is purchased in the market at price qt by working adults. Hence,

is equivalent to an in-kind transfer from the working adults to their older age relatives.Footnote13 Since family care is unpaid, the cost associated to it is determined by the foregone wages during the time spent providing LTC.Footnote14 The cost of providing unpaid family care

is given by:

(5)

(5)

where

and the provision of

is determined by Equation 3.

The utility maximization problem of a young household is solved in two steps: a cost minimization problem that determines the distribution of unpaid LTC within the household, and a utility maximization problem that determines the total supply of unpaid family care and the demand for paid care. By minimizing the cost of providing family care in Equation 5 subject to Equation 3, we obtain the following cost function:

(6)

(6)

To understand Equation 6, one can assume the (not so unrealistic) case where s = 0, that is, when all the family care is provided by women. In that case, the economic cost of providing a certain amount of family care

is equal to the forgone wages of women during the time devoted to care:

In the second step, households choose the level of unpaid family care, the amount of external care services and consumption during the two periods,

and

, to maximize lifetime utility in Equation 1 subject to the following inter-temporal budget constraint:

(7)

(7)

The first-order conditions are

(8)

(8)

(9)

(9)

(10)

(10)

Equation 8 is the standard Euler equation that solves the intertemporal problem and determines households’ savings. Equation 9 reflects the intratemporal optimal decision between consumption and paid care. A household that gives up qt units of consumption and loses qtu′(), can purchase one more unit of external care services, which provides an effective increase in marginal utility of

. The optimal amounts of consumption and paid care equalize these two magnitudes, which is what Equation 9 states. Finally, Equation 10 represents the intratemporal optimal decision between the level of participation in the labor market and providing unpaid family care. A household that provides one more unit of unpaid care obtains an increase in effective utility of γµu′(ht)(

)µ−1(

)1−µ. However, this decision involves an opportunity cost, represented by the loss of income C′(

) times the increase in utility u′(

) that would have been obtained with the additional consumption allowed by that income. Again, the optimal amounts of labor and unpaid care equalize these two magnitudes.

Production

Goods sector

Since we assume that women and men are economically identical, the total amount of labor employed in the goods sector is equal to the sum of male and female labor:

where Ltm stands for aggregate male labor and

stands for the number of female labor employed in the goods sector. The production technology of the goods sector is represented by a standard constant returns to scale (CRS) production function. Since Nt is equal to the number of households in period t, the production in per-household basis in such period is:

(11)

(11)

Where kt denotes capital per household, represents male labor per household and

represents female labor in the goods sector per household.

We assume that there is a positive gender wage gap in the goods sector, consistent with the literature that shows persistent gender wage gaps within occupations even after controlling for education, years of experience, and hours worked (Berik Citation2000; Jefferson and Preston Citation2005; Karamessini and Ioakimoglou Citation2007; van Staveren et al. Citation2007; Goldin Citation2014; Blau and Kahn Citation2017; Cutillo and Centra Citation2017). We model the gender wage gap by assuming that men are paid the marginal productivity of labor, but women only receive a fraction 0 < ξ < 1 of it. We interpret 0 < ξ < 1 as the “gender penalty” or “motherhood penalty” received by women workers (Anderson, Binder and Krause Citation2002; England Citation2005; Folbre Citation2018).Footnote15 Consequently, the optimal hiring conditions in the goods sector are:

(12)

(12)

(13)

(13)

(14)

(14)

The gender wage gap in the goods sector, defined as , is equal to 1 − ξ, which equals zero if ξ is equal to one.Footnote16 Note that this simple way of modeling the gender wage gap, caused by a wedge or margin that reduces female wages, is based on the implicit assumption that the gap is institutionally driven and not related to technological or physical attributes, as assumed in the neoclassical growth literature that involves the gender wage gap (Galor and Weil Citation1996; Yakita Citation2020).

Long-term care sector

The long-term care service sector uses female labor and produces aggregate care services

according to a CRS production function G(·).Footnote17 In per-household basis, this is equal to:

(15)

(15)

where θ is a parameter that stands for the provision of effective care per unit of professional labor, and

is female labor in the paid care sector per household. We use θ as a reduced-form productivity parameter that captures the quality of paid care, which is related to training, resources, and working conditions that are not present in the provision of unpaid family care.Footnote18 Given that

and

are both measured in (labor) time, parameter θ also represents the effectiveness of care provision by paid care services relative to the effectiveness of care provision by family members. Although we do not model public care provision explicitly, parameter θ provides a rationale for government support in providing adequate training and care infrastructure.

We assume that there is a certain degree of labor market power that is specific to the care industry. The optimal profit condition equates marginal revenues and marginal costs adjusted by the presence of the market power rent:

(16)

(16)

where

is the marginal cost,

is the marginal revenue and friction 0 < κ < 1 reflects the presence of the labor market power rent captured by employers in the care industry. Wages in the care industry are also driven by the fact that its labor market is segregated, which is consistent with the empirical evidence of women sorting into lower paid occupations, particularly the care sector.Footnote19 To be consistent with the pay penalty observed in the care services industry, we assume that wages in the care industry are lower than female wages in the rest of the economy by a factor of ν:

(17)

(17)

where 0 < ν < 1. Parameters ν and κ reflect specific institutional features of the labor market in the care industry, namely that it is dominated by women and involves a service also provided in households by women; they reflect existing evidence on wages in care industries (Folbre and Smith Citation2017).Footnote20 In fact, κ and ν can be interpreted jointly: by sorting a portion of the women’s workforce into care sector jobs that are low paid, market segmentation prevents the equalization of wages across industries and contributes to the persistence of labor market power rents.Footnote21

Equilibrium

To characterize the equilibrium, we use particular functional forms for utility and production. For the utility function, we assume the log-specification

(18)

(18)

which is standard in the literature and allows us to obtain a simple expression for savings. Using the Euler equation and the second-period budget constraint of households, we obtain an expression for savings per household:

(19)

(19)

Both family care and paid care reduce savings because they are both provided by the young generation. While paid care reduces savings by the value of the services purchased in the market, unpaid care diminishes savings by the amount of foregone wages during the time devoted to family care provision, represented by

. We use the following Cobb–Douglas production functions:

(20)

(20)

and

(21)

(21)

in the care sector and the rest of the economy (goods sector), respectively. These functional forms imply the following demand conditions for labor and capital:

(22)

(22)

(23)

(23)

(24)

(24)

(25)

(25)

The capital market equilibrium is given by:

(26)

(26)

The equilibrium condition in the labor market of the goods sector equates the labor demand ltm +

with the labor supplied by households to this sector, which is equal to

. This equilibrium results in equilibrium wages

and

.

The equilibrium condition in the labor market of the care sector is characterized by the wage , which reflects that labor is not completely mobile between the two production sectors, so female wages across the two markets are not fully equated. Finally, equilibrium in the care services market results in the relative price q and paid care services

.Footnote22

Analysis

A key aspect of our model is the way in which we model the provision of unpaid care , which occurs according to Equation 3. Combining the first order conditions with respect to

and

, one observes that the distribution of unpaid care work and, hence, the relative labor supplies of women and men, respond to the following equation:

(27)

(27)

This implies that the division of unpaid care work by gender depends on the aggregate gender wage gap, but this relation is not linear as it is shaped by the gender norm elasticity σ. Parameters s and σ fully determine the relative share of time that are devoted to unpaid care by men and women when there is no aggregate gender wage gap. For example, suppose that s = 1 − s = 0.5. This would be equivalent to the outcome of a bargaining where the man and woman have equal bargaining power. In the absence of a gender wage gap, each gender would devote the same amount of time to providing family care, that is, the ratio

would be equal to one. For simplicity, we shall refer to ratios [(1−s)/s]σ and

as the non-price and price-related determinants of the division of care work, respectively.

Parameter σ measures the extent to which the relative amount of unpaid care work provided by women responds to changes in the aggregate gender wage gap. When the gender wage gap falls, women’s relative wages increase and the household will allocate a larger share of unpaid care work to the man, as shown in Equation 27. However, the reallocation of men’s time from market to home, and women’s time from home to market, depends crucially on the value of σ. Patriarchal gender norms correspond to low values of σ, as there is little response of to changes in the gender wage gap. In this case, the decline in the gender wage gap hardly translates into a more egalitarian distribution of care work time within the household. We claim that this is an appropriate approach to rationalize the trends described previously in a macroeconomic model. If σ = 1, as implicitly assumed in most of the literature, the response of

is proportional to the change in the gender wage gap. That would indicate a case of flexible gender roles and high substitutability between women’s and men’s household labor, which is at odds with the data.Footnote23

The key point that a declining gender wage gap does not translate directly into a more equal sharing or division of household work is supported by evidence in the literature (Bittman et al. Citation2003; Gupta Citation2007; Bertrand et al. Citation2015; Lyonette and Crompton Citation2015). Michael Bittman et al. (Citation2003) used Australian and US data to demonstrate the limited effect of spouses’ contribution to family income on the division of housework. They find that women decrease their housework as their earnings increase, up to the point where both spouses contribute equally. Similarly, Sanjiv Gupta (Citation2007) finds that US women’s housework is affected only by their own earnings, not by their husbands’ nor by their earnings compared to their husbands. Bertrand, Kamenica, and Pan (Citation2015) show that among US couples where the wife earns more than the husband, the wife spends on average more time on household chores. Clare Lyonette and Rosemary Crompton (Citation2015) find that men whose partners earn more do more housework than other men, but she also finds that their level of housework is still lower than their wives. Elizabeth Washbrook (Citation2007) shows that the way in which men and women respond to economic incentives is highly asymmetric, which indicates that gender-neutral model of family decision making cannot explain the distribution of time within the household. These studies suggest that more egalitarian gender norms are needed in order to obtain a more equal division of care work, and that economic incentives, though necessary, are not a sufficient condition.

To get a closed expression of 27 in general equilibrium, we use Equations 13, 14 and 17, and the definition .

We get:

(28)

(28)

Note that the aggregate gender wage gap depends on the gender wage gap in the goods sector, which is given by the value of ξ, the pay penalty in the care sector, which is given by ν, and the fraction of female labor employed in the care sector, 1−ϕ. In other words, the aggregate gender wage gap depends on sector-specific wage gaps and the distribution of women’s workforce across sectors. Note that if there is no pay penalty in the care sector (that is, ν = 1), the aggregate gender wage gap would be equal to the gender gap in the goods sector (i.e.,

).

We can combine the first order conditions from Equations 9 and 10 to obtain the relative demand for care services. Using the specification in Equation 2 for total care, we obtain the following optimal rule:

(29)

(29)

This optimal rule equalizes the effective costs of provision of the two different types of care. We can use this equation to characterize the relative demand for paid care. If, for example, the left side of the equation is greater than the right side of the equation, the opportunity cost of providing unpaid care is greater than the effective cost of purchasing market care. The demand for market care

would increase, pushing the right side of the equation upwards. At the same time, the decrease in family care provision would cause a decrease in the term on the left side of the equation. Both sides would adjust up to the point in which the opportunity cost of unpaid care is equal to the cost of paid care. The opposite would happen if the cost of purchasing care is greater than the cost of providing unpaid care. Also note that we refer to effective costs, not merely monetary costs. We observe this is the case because the direct monetary cost

is scaled by 1/(1 − µ), while the opportunity monetary cost

is scaled by 1/µ. If µ is high, unpaid care is relatively more valued than paid care (see Equation 2), which reduces the effective cost of unpaid care but increases the effective cost of paid care in Equation 29. We can use Equation 29 to obtain an explicit relative demand for market care services:

(30)

(30)

where we see that the demand for paid care depends positively on the female and male wage rates (as they raise the opportunity cost of unpaid care) and negatively on the price of market care services and the preference parameter µ. Note that an increase in the female relative wages not only affects the way unpaid care work is distributed within the household, but also the marginal cost of providing unpaid care. To see this, we can use the expression for the aggregate gender wage gap to simplify the marginal cost:

(31)

(31)

where ξ∗ ≡ φξ + (1 − φ)νξ is the aggregate gender wage gap. The bigger the share 1 − s, the bigger the positive effect of a decline in the aggregate gender wage gap on the marginal cost of unpaid care. The latter then causes, ceteris paribus, a stronger response for paid care demand, as reflected in Equation 30. The effect also depends on the extent to which male unpaid labor is substituted for female unpaid labor, which is driven by the gender norm σ. If patriarchal norms are strong and a decrease in the gender wage gap has little effect on the allocation of time within the household, the (opportunity) marginal cost of unpaid care will barely respond to changes in the gender wage gap and a low demand for paid care services will persist.

In a general equilibrium, higher female wages not only increase the opportunity cost of unpaid care, but also increase the price of purchasing market care via increasing costs in the care industry. This pushes the demand for paid care services in the opposite direction. By combining Equations 13–14 with 16 and 17, we obtain the relative price of market care services:

(32)

(32)

Given this relationship between price and wages, in general equilibrium Equation 30 becomes:

(33)

(33)

We now observe that the relative demand for market care services also depends negatively on the gender wage gap via increasing prices (see the effect of ν and ξ in the denominator of 33). This result does not imply that a decline in the sectoral gender wage gap (increase in ξ) or an increase in the relative wages of the care sector (increase in ν) will necessarily dampen the replacement of unpaid care by paid care. To see this, note that the demand for paid care services also depends on the quality of care provision (captured by the reduced-form productivity parameter θ) and the market power rent κ. An increase in quality can potentially raise the demand for external care services and help foster the replacement of unpaid care. Crucially, the decline in the market power rent κ also has a positive effect in the reduction of the cost of market care services and contribute to expand professional care and reduce the reliance on unpaid care provision.

This analysis suggests that policies aiming to reduce the burden of unpaid care should focus on developing more egalitarian gender norms, reducing the gender wage gap and labor market segmentation and wage penalty in the care sector. It also indicates the importance of understanding the market logic of the paid care service sector, like idiosyncratic market power dynamics that, in conjunction with gender norms, might perpetuate reliance on the female provision of unpaid care. Our model suggests that for external care services to help meet long-term care needs, it is crucial to regulate firms and reduce market power rents (that is, lower κ in the model) and to make external care services accessible and productive, possibly via public investment in care, leading to higher wages, more training, and better quality care (that is, higher θ in the model).

ROLE OF POLICIES

There is by now a growing recognition that the stalled progress toward increasing women’s labor force participation is related with the unequal division of labor in households including those with frail older members to care for. This form of gender inequality has significant consequences on the labor supply as shown in our model.Footnote24 Moreover, regardless of whether they provide care women often enter traditionally “female” occupations and sectors, which tend to be undervalued because they are associated with domestic chores and care work. These are also the sectors where market power rent exists and workers have little bargaining power. In the case of the care sector, this translates into poor working conditions characterized by “just-in-time scheduling,” job insecurity, and low wages (Hwang Citation2014; Dong, Feng, and Yu Citation2017; Duncan Citation2019; Eun Citation2019; Heger and Korfhage Citation2020).

Our model’s implications highlight the importance of a comprehensive policy approach aimed at reducing the women’s care workload by promoting a more equal division of labor – albeit a shift away from traditional gender norms – and by reducing the gender wage gap and labor market segmentation. However, as Nancy Folbre (Citation2021) points out, there are also supply-side factors that maintain occupational segregation. The threat of sexual harassment and occurring condescension by male employers or coworkers for example, can deter women from entering traditional “male” occupations. Filial piety or moral commitment to their aging parents also can influence labor market decisions.

This comprehensive policy approach involves three elements. First, there is a need for gender-aware public policies that systematically encourage gender-egalitarian social norms that lead to more equal sharing of family care work. We have shown in our model that gender division of unpaid care work depends not only on the gender wage gap, but also on social norms, which shapes the response of the distribution of care work to changes in market prices. Egalitarian norms can be encouraged through the provision of paid parental leave and workplace leave policies that enable women and men to balance their paid and care work responsibilities. It is also important to carry out gender aware assessments of labor and social policies, with attention given to those in the so-called female occupations and sectors including the care sector.Footnote25

Second, there is a need for a coherent yet strategic approach involving gender-aware labor and social policies that strengthen the rights of workers, especially care workers in policy engagements and collective bargaining. Our model indicates the power imbalance between employers and workers, depicted in our model by market power rents. This imbalance raises the price of care services without raising wages, which contributes to perpetuate the reliance on unpaid care. While policies that promote economic growth can expand employment opportunities, they may simultaneously maintain market power rents and the “care pay penalty,” reinforcing the gender wage gap, occupational segregation, and the unequal distribution of unpaid care, thus undermining any progress toward gender equality. This problem calls for governments to have a plan of action to create a market environment that uphold rights at work and decent employment, especially for women, and to develop and implement policies that address gender biases and discrimination in the labor market. Such plans include not only the adoption of pay equity law and effective enforcement of affirmative action, but also the implementation of gender-aware assessments of labor and social policies. Collective bargaining is also needed to ensure that workers receive adequate and equitable pay and have decent working conditions.

Third, governments should play an active role in regulating and supporting LTC services to make quality care more available and accessible (Dong et al. Citation2017). Our study shows that enhancing quality in professional care provision crucially matters for the demand of professional care. Care services are increasingly acknowledged as necessary social infrastructure (Meagher Citation2006; Himmelweit Citation2014). LTC is fundamental in human well-being and the sustenance of the retired labor force, and has many important positive externalities, including externalities on women’s labor supply, as our model illustrates. Hence, LTC is an unavoidable cost needed for the operation of the economy and society just as with health care and education. Aging societies now recognize the importance of public investment in LTC provisioning and the need for government support in providing adequate training and decent working conditions to LTC workers (OECD Citation2020). Giving family members greater flexibility in their choice of family-outside care combination will require gender-sensitive fiscal policies that help ensure adequate pay and benefits to LTC workers. Such policies also help promote quality of care by attracting and retaining workers to meet the growing care demand (OECD Citation2020).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

This article provides a tractable way of introducing gender norms in a macroeconomic model that incorporates LTC needs, gender-based family care, gendered labor market, and LTC service sector. We assume that gender norms shape the substitutability between women’s and men’s care work. The model demonstrates the interplay of gender relations in households in determining the extent to which gendered division of labor and women’s labor force participation are affected by changes in the gender wage gap. Consequently, our model articulates the fact that gender norms permeate the household sector and labor markets. Patriarchal norms prevent a more equal distribution of housework and care work, even if the gender wage gap falls. Our model also takes into account some pertinent characteristics of an unregulated LTC service sector, which results in the high cost of private long-term care and variability in its quality. This reinforces the reliance on the family to provide LTC. The use of paid versus unpaid care work to meet long-term care needs therefore depends not only on savings and gender norms, as argued in the existing literature, but also on the existence of market power rents and gender-based labor market segmentation that affects wages and productivity in the LTC service sector. We conclude with a discussion of policies that promote gender equality in households and labor markets and that enhance quality (productivity) in paid care services, which are conducive to gender-equitable outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the participants of the July 2020 Care Work and the Economy Research-in-Progress webinar series for their helpful comments and suggestions. The authors also would like to acknowledge the financial support of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation through the Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM) project.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ignacio González

Ignacio González is Assistant Professor at the Department of Economics of American University in Washington, DC. Before joining AU, he was a postdoctoral research scholar at Columbia University under the mentorship of Joseph Stiglitz. His research field is Macroeconomics and his current research focuses on the connections between financial markets and inequality. He is also interested in public finance, economic growth, and international finance. Dr. González holds a PhD in Economics from the European University Institute.

Bongsun Seo

Bongsun Seo is a PhD candidate in Economics at American University in Washington, DC. Her research fields are in labor, gender, and demographic economics. Her current research focuses on the impact of informal caregiving and related policies on caregivers’ labor outcomes. She is also interested in evaluating social policies that address gender equality in the household and in the labor market. She holds an MA in Economics from Georgetown University and a BA in Economics and Mathematics from Emory University.

Maria S. Floro

Maria S. Floro is Professor of Economics and co-director of the Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE) at American University in Washington, DC. Her publications include co-authored books on Informal Credit Markets and the New Institutional Economics, Women's Work in the World Economy, and Gender, Development, and Globalization: Economics as if All People Mattered and articles on time use, care work and unpaid work, gender and vulnerability, urban food security, poverty, ecological crises, household savings, credit and informal employment. Dr. Floro currently leads the Care Work and the Economy Project (www.careworkeconomy.org).

Notes

1 While we explicitly model LTC provision, our model can be modified to study other types of care such as childcare and care for the disabled.

2 This puzzle is particularly prevalent in countries with feeble or non-existent public investment in LTC services, such as the United States. Needless to say, there are also other factors at play. For example, one of the main reasons for a shallow private long-term care insurance market is that it is actuarially difficult to account for future costs.

3 We focus on OECD countries due to data limitations on the gender-disaggregated wage gap in developing countries. Also note we include the standard measure of old-age dependency ratio, defined as the ratio of people older than 64 to the working-age population (15–64). However, recent literature (see Muszyńska and Rau [Citation2012] and King et al. [Citation2021] for example) have shown that other measures of dependency ratios may be more relevant with decreased morbidity and increased life expectancy.

4 An important caveat to note is that to date, there is hardly any data or research on the trend in the division of LTC provided by family members over time. We therefore rely on evidence provided by longitudinal studies on time spent by women and men in unpaid care work, which includes domestic chores and all forms of care work (that is, childcare, sick care/disabled care, and LTC).

5 While it is true that the gap between men’s and women’s non-market work has changed little, it is also true that overall time devoted to housework has declined in many countries; in the US co-resident fathers have increased their time in childcare, as have mothers (Parker and Wang Citation2013).

6 According to OECD (Citation2020), personal care workers of older persons constitute the bulk of the long-term care workforce (70 percent) in OECD and have very low entry requirements into the job.

7 LTC can refer to both direct relational care and indirect care. See ILO (Citation2018a) for the definition and scope of care work.

8 Since the focus of the study is the study of long-term care provision, we do not model childrearing explicitly. However, the time allocation for childrearing could be modeled using the setup described in this section. In particular, Equation (3) provides a rationale to study unequal care workload within the household and the lack of response of such workload to changes in market prices. Although a model with childcare would imply a different dynamic setup, the distribution of unpaid care work would be along the same lines.

9 Note that we limit unpaid family care to care provided by working-age adults in the household in order to study the intergenerational dynamics. However, we acknowledge that unpaid care provided by female spouses are also a significant part of family care.

10 There are different types of paid care services, such as institutional care and in-home care. For simplicity, we do not differentiate between the types of paid care services to focus on the usage of unpaid care versus paid care.

11 Andrea Ichino et al. (Citation2019) use a similar specification to evaluate the empirical relevance of gender norms.

12 Christian Siegel (Citation2017) uses a similar specification to model the distribution of home production and the evolution of fertility rates, although his interpretation is not in terms of gender norms.

13 Alternatively, one can assume that older persons, not working-age individuals, are the ones who directly purchase care services in the market using the own savings. Such specification would have different implications for savings.

14 In our model, a decrease in the gender wage gap increases the opportunity cost of providing unpaid care for married women, relative to that of married men. While this is true for some women, the opportunity cost remains low for some women, especially those with lower education (Howes Citation2005). This heterogeneity is masked in our aggregate model.

15 Monopsony could also help explain how discriminatory gender wage differences arise and persist if employers yield greater monopsony power over women than men. Dan A. Black (Citation1995) develops a model in which search costs give employers a degree of monopsony power. If there is discrimination against women, women will face higher search costs than men, increasing employers’ monopsony power over them.

16 For simplicity, since the focus of the article is the gender wage gap, we abstract from labor market power dynamics that jointly affect women and men, which have been the subject of study by the recent literature on monoposony power.

17 The assumption that only women work in the paid care sector is consistent with and driven by gender norms.

18 There is an extensive literature that shows how wages and working conditions affect the commitment of the caregivers and, in general, the quality of the care service (see Whitebook, Philipps, and Howes Citation1989; Redfern et al. Citation2002; Burgio et al. Citation2004; Folbre Citation2006; Hanefeld, Powell-Jackson, and Balabanova Citation2017; Tawfik et al. Citation2019).

19 According to Nancy Folbre and Kristin Smith (Citation2017), lower earnings in care industries are explained by specific features of care work.

20 As shown by Equations 16 and 17, both parameters would be equivalent if female wages in the rest of the economy are equal to the marginal product in the care industry, which does not need to be necessarily true.

21 This interpretation would be consistent with a model that endogenizes κ in terms of ν. Here, for simplification purposes, we assume that both κ and ν are parameters.

22 The log-utility specification provides straightforward equilibrium expressions for savings, consumption in each period, unpaid care, paid care, wages, and the return to capital. For realistic parametrizations, the gender wage gap has negative effect on savings and capital stock. Since the focus of the article is on the interplay of gender norms and labor supply, the analysis below focuses on paid care and unpaid care.

23 Given an observed aggregate gender gap, parameters σ and s could be used to calibrate a steady state allocation of time in a dynamic general equilibrium model.

24 Kanika Arora and Douglas A. Wolf (Citation2014), Anna M. Hammersmith and I-Fen Lin (Citation2019), and Nicholas T. Bott, Clifford C. Sheckter and Arnold S. Milstein (Citation2017) demonstrate the difficulties that LTC providers face in balancing care responsibilities with their employment. Other studies show that an increase in unpaid LTC can lead to withdrawal from the labor force or a shift from fulltime to part-time employment (Butrica and Karamcheva Citation2014; Chari et al. Citation2015; Reinhard et al. Citation2019).

25 Policies providing pensions and long-term care insurance schemes for example, can carry implicit gender bias and care penalties (Ham and Kwon Citation2017; Folbre Citation2021).

REFERENCES

- Agénor, Pierre-Richard. 2018. “A Theory of Social Norms, Women’s Time Allocation, and Gender Inequality in the Process of Development.” Technical Report 237, Economics, University of Manchester.

- Agénor, Pierre-Richard and Madina Agénor. 2014. “Infrastructure, Women’s Time Allocation, and Economic Development.” Journal of Economics 113(1): 1–30.

- Akerlof, George A. and Rachel E. Kranton. 2000. “Economics and Identity.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(3): 715–53.

- Ameriks, John, Joseph S. Briggs, Andrew Caplin, Matthew D. Shapiro, and Christopher Tonetti. 2015. “Long-Term-Care Utility and Late-in-Life Saving.” Technical Report w20973, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

- Anderson, Deborah J., Melissa Binder, and Kate Krause. 2002. “The Motherhood Wage Penalty: Which Mothers Pay It and Why?” American Economic Review 92(2): 354–8.

- Arora, Kanika and Douglas A. Wolf. 2014. “Is There a Trade-off Between Parent Care and Self-care?” Demography 51(4): 1251–70.

- Barigozzi, Francesca, Helmuth Cremer, and Kerstin Roeder. 2017. “Caregivers in the Family: Daughters, Sons and Social Norms.” SSRN Electronic Journal.

- Bauer, Jan Michael and Alfonso Sousa-Poza. 2015. “Impacts of Informal Caregiving on Caregiver Employment, Health, and Family.” Journal of Population Ageing 8(3): 113–45.

- Beneria, Lourdes. 1979. “Reproduction, Production and the Sexual Division of Labour.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 3(3): 203–25.

- Beneria, Lourdes, Günseli Berik, and Maria S. Floro. 2016. Gender, Development and Globalization: Economics as if All People Mattered. New York: Routledge.

- Bergmann, Barbara R. 2005. The Economic Emergence of Women. 2nd ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Berik, Günseli. 2000. “Mature Export-Led Growth and Gender Wage Inequality in Taiwan.” Feminist Economics 6(3): 1–26.

- Bertrand, Marianne, Emir Kamenica, and Jessica Pan. 2015. “Gender Identity and Relative Income within Households.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 130(2): 571–614.

- Bittman, Michael, Paula England, Liana Sayer, Nancy Folbre, and George Matheson. 2003. “When Does Gender Trump Money? Bargaining and Time in Household Work.” American Journal of Sociology 109(1): 186–214.

- Black, Dan A. 1995. “Discrimination in an Equilibrium Search Model.” Journal of Labor Economics 13(2): 309–34.

- Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2017. “The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations.” Journal of Economic Literature 55(3): 789–865.

- Borrowman, Mary and Stephan Klasen. 2020. “Drivers of Gendered Sectoral and Occupational Segregation in Developing Countries.” Feminist Economics 26(2): 62–94.

- Bott, Nicholas T., Clifford C. Sheckter, and Arnold S. Milstein. 2017. “Dementia Care, Women’s Health, and Gender Equity: The Value of Well-Timed Caregiver Support.” JAMA Neurology 74(7): 757–8.

- Braunstein, Elissa, Irene van Staveren, and Daniele Tavani. 2011. “Embedding Care and Unpaid Work in Macroeconomic Modeling: A Structuralist Approach.” Feminist Economics 17(4): 5–31.

- Bueren, Jesus. 2017. “Long-Term Care Needs: Implications for Savings, Welfare, and Public Policy.” Job Market Paper.

- Burda, Michael, Daniel S. Hamermesh, and Philippe Weil. 2013. “Total Work and Gender: Facts and Possible Explanations.” Journal of Population Economics 26(1): 239–61.

- Burgio, Louis D., Susan E. Fisher, J. Kaci Fairchild, Kay Scilley, and J. Michael Hardin. 2004. “Quality of Care in the Nursing Home: Effects of Staff Assignment and Work Shift.” Gerontologist 44(3): 368–77.

- Butrica, Barbara and Nadia Karamcheva. 2014. “The Impact of Informal Caregiving on Older Adults’ Labor Supply and Economic Resources.” Technical Report, Urban Institute.

- Chari, Amalavoyal V., John Engberg, Kristin N. Ray, and Ateev Mehrotra. 2015. “The Opportunity Costs of Informal Elder-Care in the United States: New Estimates from the American Time Use Survey.” Health Services Research 50(3): 871–82.

- Cutillo, Andrea and Marco Centra. 2017. “Gender-Based Occupational Choices and Family Responsibilities: The Gender Wage Gap in Italy.” Feminist Economics 23(4): 1–31.

- Dong, Xiaoyuan, Jin Feng, and Yangyang Yu. 2017. “Relative Pay of Domestic Eldercare Workers in Shanghai, China.” Feminist Economics 23(1): 135–59.

- Doss, Cheryl. 2013. “Intrahousehold Bargaining and Resource Allocation in Developing Countries.” World Bank Research Observer 28(1): 52–78.

- Duncan, Cathy. 2019. “Struggles in (Elderly) Care: A Feminist View.” International Journal of Care and Caring 3(4): 607–9.

- Elson, Diane. 1995. Male Bias in the Development Process. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- England, Paula. 2005. “Emerging Theories of Care Work.” Annual Review of Sociology 31: 381–99.

- Eun, Heo. 2019. “Trilemma of Social Service Policy-making and the Low-wage Jobs of Longterm Care for Elderly.” Korean Journal of Labor Studies 25(3): 195–238.

- Floro, Maria S. and Hitomi Komatsu. 2011. “Gender and Work in South Africa: What Can Time-Use Data Reveal?” Feminist Economics 17(4): 33–66.

- Floro, Maria Sagrario and Mieke E. Meurs. 2009. “Global Trends in Women’s Access to ‘Decent Work’.” Dialogue on Globalization Occasional Papers No. 43. Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- Folbre, Nancy. 1986. “Cleaning House: New Perspectives on Households and Economic Development.” Journal of Development Economics 22(1): 5–40.

- Folbre, Nancy.. 1994. Who Pays for the Kids? Gender and the Structures of Constraint. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- Folbre, Nancy.. 2006. “Demanding Quality: Worker/Consumer Coalitions and ‘High Road’ Strategies in the Care Sector.” Politics & Society 34(1): 11–32.

- Folbre, Nancy.. 2018. “The Care Penalty and Gender Inequality.” In The Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy, edited by Susan L. Averett, Laura M. Argys, and Saul D. Hoffman, 748–66. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Folbre, Nancy.. 2021. The Rise and Decline of Patriarchal Systems: An Intersectional Political Economy. London: Verso.

- Folbre, Nancy and Kristin Smith. 2017. “The Wages of Care: Bargaining Power, Earnings and Inequality.” Washington, DC: Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts, Amherst and Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

- Galor, Oded and David N. Weil. 1996. “The Gender Gap, Fertility, and Growth.” American Economic Review 86(3): 374.

- Goldin, Claudia. 2014. “A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter.” American Economic Review 104(4): 1091–119.

- Gupta, Sanjiv. 2007. “Autonomy, Dependence, or Display? The Relationship Between Married Women’s Earnings and Housework.” Journal of Marriage and Family 69(2): 399–417.

- Ham, Sunyu and Hyunji Kwon. 2017. “Care Penalty: Devaluation and Marketization of Care.” Korean Journal of Labor Studies 23(3): 131–76.

- Hammersmith, Anna M. and I-Fen Lin. 2019. “Evaluative and Experienced Well-being of Caregivers of Parents and Caregivers of Children.” Journals of Gerontology: Series B 74(2): 339–52.

- Hanefeld, Johanna, Timothy Powell-Jackson, and Dina Balabanova. 2017.“Understanding and Measuring Quality of Care: Dealing With Complexity.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 95(5): 368–74.

- Hartmann, Heidi. 1976. “Capitalism, Patriarchy, and Job Segregation by Sex.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 1(3, Part 2): 137–69.

- Hartmann, Heidi. 1982. “Preface: Women and Work: An Introduction.” Feminist Studies 8(2): 231–34.

- Heger, Dörte and Thorben Korfhage. 2020. “Short- and Medium-Term Effects of Informal Eldercare on Labor Market Outcomes.” Feminist Economics 26(4): 205–27.

- Heintz, James and Nancy Folbre. 2019. “Endogenous Growth, Population Dynamics, and Returns to Scale: Long-Run Macroeconomics When Demography Matters.” CWE-GAM Working Paper Series: 19-01. Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University, Washington, DC.

- Henle, Christine A., Gwenith G. Fisher, Jean McCarthy, Mark A. Prince, Victoria P. Mattingly, and Rebecca L. Clancy. 2020. “Eldercare and Childcare: How Does Caregiving Responsibility Affect Job Discrimination?” Journal of Business and Psychology 35(1): 59–83.

- Himmelweit, Susan. 2014. “The Marketisation of Care Before and During Austerity.” Paper presented at IIPPE Annual Conference, Naples, September 16–18.

- Howes, Candace. 2005. “Living Wages and Retention of Homecare Workers in San Francisco.” Industrial Relations 44(1): 139–63.

- Hwang, Deok Soon. 2014. “Study on Working Conditions and Informal Employment in the Labor Market for Care Workers.” In Labor Issues in Korea 2012, edited by Hoon Kim, 35–78. Seoul: Korea Labor Institute.

- Ichino, Andrea, Martin Olsson, Barbara Petrongolo, and Peter Skogman Thoursie. 2019. “Economic Incentives, Home Production and Gender Identity Norms.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 12391, Institute of Labor Economics, Bonn.

- ILO. 2018a. Care Work and Care Jobs: For the Future of Decent Work. International Labour Organization Report. Geneva: ILO.

- ILO. 2018b. global Wage Report 2018/19 – What Lies Behind Gender Pay Gaps. Geneva: ILO.

- Jefferson, Therese and Alison Preston. 2005. “Australia’s ‘Other’ Gender Wage Gap: Baby Boomers and Compulsory Superannuation Accounts.” Feminist Economics 11(2): 79–101.

- Karamessini, Maria and Elias Ioakimoglou. 2007. “Wage Determination and the Gender Pay Gap: A Feminist Political Economy Analysis and Decomposition.” Feminist Economics 13(1): 31–66.

- King, Elizabeth M., Hannah L. Randolph, Maria S. Floro, and Jooyeoun Suh. 2021. “Demographic, Health, and Economic Transitions and the Future Care Burden.” World Development 140: 105371.

- Ko, Ami. 2016. “An Equilibrium Analysis of the Long-Term Care Insurance Market.” Department of Economics, Georgetown University.

- Kydland, Finn and Nick Pretnar. 2019. “The Costs and Benefits of Caring: Aggregate Burdens of an Aging Population.” NBER Working Paper 25498, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

- Lagerlöf, Nils-Petter. 2003. “Gender Equality and Long-Run Growth.” Journal of Economic Growth 8(4): 403–26.

- Liu, Lan, Xiao yuan Dong, and Xiaoying Zheng. 2010. “Parental Care and Married Women’s Labor Supply in Urban China.” Feminist Economics 16(3): 169–92.

- Lockwood, Lee M. 2018. “Incidental Bequests and the Choice to Self-Insure Late-Life Risks.” American Economic Review 108(9): 2513–50.

- Luo, Meng Sha and Ernest Wing Tak Chui. 2019. “Trends in Women’s Informal Eldercare in China, 1991–2011: An Age–Period–Cohort Analysis.” Ageing and Society 39(12): 2756–75.

- Lyonette, Clare and Rosemary Crompton. 2015. “Sharing the Load? Partners’ Relative Earnings and the Division of Domestic Labour.” Work, Employment and Society 29(1): 23–40.

- Meagher, Gabrielle. 2006. “What Can We Expect from Paid Carers?” Politics & Society 34(1): 33–54.

- Miller, Ray and Neha Bairoliya. 2021. “Parental Caregivers and Household Power Dynamics.” Feminist Economics. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2021.1975793.

- Mommaerts, Corina. 2015. “Long-Term Care Insurance and the Family.” Job Market Paper.

- Muszyńska, Magdalena M. and Roland Rau. 2012. “The Old-Age Healthy Dependency Ratio in Europe.” Journal of Population Ageing 5(3): 151–62.

- OECD. 2020. Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Care Workers for the Elderly. OECD Health Policy Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Parker, Kim and Wendy Wang. 2013. “Americans Time at Paid Work, Housework, Child Care, 1965–2011” Pew Research Center, 14.

- Pearse, Rebecca and Raewyn Connell. 2016. “Gender Norms and the Economy: Insights from Social Research.” Feminist Economics 22(1): 30–53.

- Redfern, Sally, Shirina Hannan, Ian Norman, and Finbarr Martin. 2002. “Work Satisfaction, Stress, Quality of Care and Morale of Older People in a Nursing Home.” Health & Social Care in the Community 10(6): 512–7.

- Reinhard, Susan C., Heather M. Young, Carol Levine, Kathleen Kelly, Rita Choula, and Jean Accius. 2019. “Home Alone Revisited: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Care.” Technical Report, AARP Public Policy Institute, Washington, DC.

- Sevilla-Sanz, Almudena, Jose Ignacio Gimenez-Nadal, and Cristina Fernández. 2010. “Gender Roles and the Division of Unpaid Work in Spanish Households.” Feminist Economics 16(4): 137–84.

- Siegel, Christian. 2017. “Female Relative Wages, Household Specialization and Fertility.” Review of Economic Dynamics 24: 152–74.

- Sullivan, Oriel. 2019. “Gender Inequality in Work-Family Balance.” Nature Human Behaviour 3(3): 201–3.

- Tabata, Ken. 2005. “Population Aging, the Costs of Health Care for the Elderly and Growth.” Journal of Macroeconomics 27(3): 472–93.

- Tawfik, Daniel S., Annette Scheid, Jochen Profit, Tait Shanafelt, Mickey Trockel, Kathryn C. Adair, J. Bryan Sexton, and John P. A. Ioannidis. 2019. “Evidence Relating Health Care Provider Burnout and Quality of Care: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis.” Annals of Internal Medicine 171(8): 555–67.

- van Staveren, Irene, Diane Elson, Caren Grown, and Nilufer Cagatay, eds. 2007. The Feminist Economics of Trade. London: Routledge.

- Washbrook, Elizabeth. 2007. “Explaining the Gender Division of Labour: The Role of the Gender Wage Gap.” Working Paper, University of Bristol.

- Whitebook, Marcy, Deborah Philipps, and Carollee Howes. 1989. “Who Cares? Child Care Teachers and the Quality of Care in America.” Young Children 45(1): 41–5.

- World Bank. 2011. World Development Report 12: Gender Equality and Development. Technical Report. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Yakita, Akira. 2020. “Economic Development and Long-Term Care Provision by Families, Markets and the State.” Journal of the Economics of Ageing 15: 100210.