?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Gender inequality affects agricultural production and rural households’ capacity to build climate resilience, especially in developing countries. However, empirical research on promoting women’s empowerment in the face of environmental threats is limited, particularly in areas vulnerable to the impact of climate change, such as semi-arid regions. This study identifies factors promoting women’s empowerment in semi-arid regions and the mechanisms behind them. This mixed-methods case study was conducted in a semi-arid area in Northeastern Brazil, utilizing household surveys, key informant interviews, and focus groups. Results show that accessing targeted credit lines and extension services was significantly associated with empowerment. The qualitative findings suggest that adopting participatory mechanisms in policymaking and utilizing feminist pedagogy and popular education in the intervention delivery process was crucial to achieving women’s empowerment in the study area.

HIGHLIGHTS

Climate change increases risks for rural livelihoods, highlighting the need for resilience.

Women’s empowerment is key to bolstering agriculture’s resilience in semi-arid regions, such as northeastern Brazil.

Participatory approaches in policy design are crucial for women's empowerment success.

Inclusion of feminist pedagogy in interventions enhances rural women’s empowerment.

INTRODUCTION

Reducing gender inequality in agriculture has been widely acknowledged as an important part of the solution to global hunger. Besides the issue of gender justice, addressing gender disparities in farm productivity and the wage gap in agrifood employment could reduce global food insecurity by approximately 2 percent (FAO Citation2023). An extensive body of literature has shown the positive impact of women’s empowerment on child nutrition (Malapit et al. Citation2013; Heckert, Olney, and Ruel Citation2019), child health (Essilfie, Sebu, and Annim Citation2020), and the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices (Bayeh Citation2016).

With the rising challenges of climate change, rural households become more susceptible to events such as droughts, floods, and the depletion of natural resources, contributing to the rapid deterioration of farmers’ source of livelihood (FAO Citation2015). In this context, rural women in developing countries are most adversely hit by climate-related events, as they usually face barriers in accessing and controlling resources central to building resilience to climate change and participation in the decision-making processes (Djoudi and Brockhaus Citation2011; Ravera et al. Citation2016; Abid et al. Citation2018; McOmber, Audia, and Crowley Citation2019). This problem is particularly relevant in areas more exposed to climate change, such as semi-arid environments. Consequently, strategies promoting women’s empowerment in such environments are essential for building resilience to environmental shocks (Feitosa and Yamaoka Citation2020; Diarra et al. Citation2021; Otieno et al. Citation2021; Datey et al. Citation2023).

Although several studies illustrate women’s importance in resilience-building and rural development in developing countries (Djoudi and Brockhaus Citation2011; Ravera et al. Citation2016; Abid et al. Citation2018; McOmber, Audia, and Crowley Citation2019), our research aspires to enhance this body of literature by contributing a mixed-methods perspective to understand women's empowerment in climate-vulnerable semi-arid regions. This study aims to expand the literature by examining the interventions that could contribute to women’s empowerment in semi-arid areas by conducting a case study in the Brazilian semi-arid area of Chapada do Apodi (state of Rio Grande do Norte). Using a mixed-methods approach, we collected data from policymakers, local leaders, and farmers, in two phases. First, we conducted key informant interviews in August 2015. Then, we conducted a household survey using the abbreviated version of the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) and focus groups from September to November 2015. The varying granularity and depth of the different methods provide valuable data, and the generated insights can aid the design of policies promoting women’s empowerment in areas vulnerable to the impact of climate change.

BACKGROUND

Rural women, the semi-arid, and climate change

Climate change greatly affects the lives and livelihoods of the world’s poorest, and these effects are anticipated to have a disproportionate impact on smallholder farmers in semi-arid regions of developing countries (FAO Citation2015). Key consequences of climate change in semi-arid regions include rising temperatures, longer dry spells, extended droughts, shifts in the timing of the beginning and end of the rainy season, and alterations in the duration of agricultural growth periods (Lawson et al. Citation2020).

People will experience the effects of climate change differently according to their vulnerability (Djoudi and Brockhaus Citation2011; Alston Citation2014). Rural women in developing countries, particularly in semi-arid regions, are most adversely hit by climate change events, mainly due to gender norms that lead to a lack of access to resources and decision-making spaces, placing them in a vulnerable position in times of crisis (Djoudi and Brockhaus Citation2011; Louis and Mathew Citation2020). Despite their essential role in agricultural production, women struggle to access resources such as land (Deere and León Citation2003; Doss, Meinzen-Dick, and Bomuhangi Citation2014) and agricultural inputs (Peterman, Behrman, and Quisumbing Citation2011, among others).

While women are disadvantaged when facing climate-change-related events, they should not be seen as passive agents. Recent studies have shown a boost in climate change resilience-building when women have access to interventions that facilitates access to resources and political decision making (Ncube, Mangwaya, and Ogundeji Citation2018; Feitosa and Yamaoka Citation2020; Mbaye Citation2020) For example, in a study conducted in the Brazilian semi-arid region, Cíntya Feitosa and Marina Yamaoka (Citation2020) show that rural women can have a leading role in climate-resilience building. The authors argue that fostering participatory forms of governance and agroecological practices with gender-sensitive education supporting women’s empowerment positively affects building resilience. Along the same line, Linguère Mously Mbaye (Citation2020) argues that promoting women’s empowerment is essential to building strength to deal with the adverse effects of climate shocks and stressors. When women are involved in decision making and have bargaining power, they can contribute to adaptation and mitigation while ensuring household food security (Ajani, Onwubuya, and Mgbenka Citation2013).

Recognizing women’s role and promoting empowerment in semi-arid regions is critical to building resilience in agriculture on different fronts. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the challenges faced in such conditions to design interventions promoting women’s empowerment.

What influences women’s empowerment in agriculture? A short review

It is important to understand what influences women's empowerment in agriculture to develop effective interventions. The literature has extensively explored women's empowerment and credit access, suggesting that financial independence is vital for strengthening the role of women as producers and increasing their economic opportunities. For instance, Syed M. Hashemi, Sidney Ruth Schuler, and Ann P. Riley (Citation1996) found that microfinance programs have a significant impact on women's empowerment. Diana Fletschner and Lisa Kenney (Citation2014) argued that this positive impact is not automatic, rather, it depends on how appropriate financial products for women are designed. Additionally, Marya Hillesland et al. (Citation2022) evaluated a United Nations program in Ethiopia that aimed to empower rural women through women-run savings and credit cooperatives, finding a positive impact on the intrinsic agency of beneficiaries who had continued access to credit programs.

In Brazil, qualitative studies have shown that rural women's access to rural development interventions can foster empowerment. Local studies commonly interpret empowerment in terms of economic and decision-making autonomy and improved livelihood (Feitosa and Yamaoka Citation2020; Brandão, Borges, and Bergamasco Citation2021; Spanevello et al. Citation2021). Rosani Marisa Spanevello et al. (Citation2021) indicated that rural women who are granted credit to invest in their agricultural farms in Brazil experienced a boost in their confidence, economic empowerment, and farm’s decision-making participation. This study utilized exploratory qualitative research methods to understand behavioral patterns and interpersonal dynamics. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to gain deeper insights into the research subject from individuals directly involved. In a related study, Cleonice Elias Santos (Citation2020) noted that access to the rural credit policy significantly boosted local market engagement of women farmers in semi-arid northern Minas Gerais. Santos’s (Citation2020) qualitative research used semi-structured interviews to collate insights from institutional representatives and women farmers, emphasizing the socioeconomic advances achieved and the challenges presented by financial institutional barriers. Tatiana Frey Biehl Brandão, Janice Rodrigues Placeres Borges, and Sonia Maria Pessoas Pereira Bergamasco (Citation2021) showed that access to interventions that promote women's farmer organizations is strategic in promoting social inclusion and empowering women in Northeast Brazil. Brandão, Borges, and Bergamasco’s (Citation2021) study adopted a qualitative case study approach, incorporating methods such as interviews, focus groups, and documentary research to understand the social realities of the participants. Similarly, Els Lecoutere's (Citation2017) study in Uganda found that women who participated in farmer's groups had increased access to information and markets, which led to overall improved agricultural productivity and income. This qualitative study also found that women's participation in farmer's groups increased their confidence and decision-making power within their households.

The interplay between women's empowerment and access to extension services has been a topic of extensive study. Jillian L. Waid et al. (Citation2022) found that a three-year homestead food production program in rural Habiganj, Sylhet, Bangladesh, improved women's agency, leading to greater ownership of assets, better control of income, expanded group membership, and increased self-efficacy. C. Ragasa (Citation2014) highlighted the importance of gender-responsive strategies in agricultural extension programs. The author suggested that the development and application of specific strategies were crucial for empowering women. These strategies include fostering self-help groups and women's associations, recruiting and training women extension agents, and allocating seats for women representatives on local councils. Consistent monitoring of these implementations was also deemed essential.

Studies conducted in Brazil have highlighted the influence of the use of gendered approaches in extension services in empowering rural women. Feitosa and Yamaoka (Citation2020) demonstrated that integrating a gender perspective into climate adaptation extension services enhances the position of women in their communities, fosters stronger social connections, improves participatory governance, and increases income levels. Additionally, Sônia Fátima Schwendler and Lucia Amaranta Thompson (Citation2017), utilizing qualitative methods including observations, and interviews, argued that critical extension education, focusing on agroecology and gender-oriented pedagogy, enables both women and men to challenge the traditional sexual division of labor in rural communities. In a similar vein, Mirian Fabiane Strate and Sonia Maria da Costa's (Citation2018) qualitative study revealed that in Brazil, access to extension services, credit, and institutional markets boosted women's empowerment by amplifying home garden production and women's participation in local markets.

In our review of the literature, we found that several have explored the topic of women's empowerment in Brazil, using qualitative methods. While these studies have made valuable contributions to understanding the dynamics of women's empowerment in the region, our study expands upon this existing knowledge base by introducing a distinct mixed-method approach. To our knowledge, our research is the first to apply the A-WEAI in Northeastern Brazil, offering a systematic and statistically sound measure of women's empowerment in the agricultural sector.Footnote1 The quantitative component allows for more objective, quantifiable insights into women's empowerment, providing robust data that complement the rich narratives and perspectives unearthed in previous qualitative studies. By integrating this tool into our methodology, we aim to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of women's empowerment in the region, bridging the gap between qualitative and quantitative inquiry.

Gender and rural development in Brazil (2003–16)

In Brazil, the recognition of women’s importance in rural development is a relatively recent phenomenon and was boosted because of the feminist movement’s pressure and political will during the administration of the Workers’ Party (2003–16). In this period, rural women gained political visibility and were systematically included across rural development programs.

The first change observed in this direction was the creation of the Special Advisory of Gender and Ethnic-Racial Matters (AEGRE) in the Ministry of Agrarian Development (MDA) in 2003. In 2010, this special advisory body became the Rural Women’s Policy Agency (DPMR), gaining department-level status (with a budget and dedicated staff). The DPMR oversaw the development of targeted policies and the promotion of gender equality outcomes across all departments in the MDA (Siliprandi Citation2009; Hora and Butto Citation2014). Particularly, the DPMR ensured that policies aimed at promoting women’s empowerment clearly stated this goal rather than assuming the empowerment of women would occur naturally. This principle is shown to be critical in a recent study that reviewed several programs across nine developing countries in South Asia and Africa (Quisumbing et al. Citation2022).

The DPMR designed its policy portfolio using participatory methods, with the close participation of the rural women’s movements and the operating principles of agroecology and feminist economics; this process started in 2003 (Siliprandi Citation2009; Butto et al. Citation2011). According to Alexandra Filipak (Citation2017), another significant achievement during the Workers’ party administration was the introduction of mandatory double titling of the Eligibility Declaration of Family Farming (DAP), which allowed women to access rural development interventions. The DAP is a document that qualifies smallholder farmers to access rural development policies (providing information on farm size, type of labor, annual income, and so on). Before 2004, only one member of a rural household could be the titular holder of this document, and men were usually the titular holders.

During the Worker’s Party administration, women’s autonomy and empowerment were central to the policy portfolio. According to Karla Hora and Andrea Butto (Citation2014), rural women’s policies were divided into three main portfolios. The first was focused on providing documents to rural women. The main program under this axis was the National Program of Documentation for Women Farmers (PNDTR), which provided documents (civil, legal, and work-related) free of charge to rural women. The second portfolio focused on providing rural women access to land, water, and other natural resources. The most emblematic policy under this axis was the II National Program of Agrarian Reform (PNRA), which, among other changes, instituted the mandatory joint adjudication of the title of the farms in land reform settlements. Lastly, the third portfolio focused on promoting rural women’s productive inclusion through food acquisition programs, access to credit, access to extension services, access to water, and promoting women farmers’ organizations, among other initiatives. This included rural women in rural development and policies that enacted their identity as farmers and their political recognition as an essential group for Brazilian food security and sustainable rural development (Siliprandi Citation2009; Filipak Citation2017). The interventions relevant to this study are within the third portfolio, more specifically, those in the programs described below:

The Extension and Advisory Service Program (PNATER) included women from family farming via quotas of 30–50 percent (according to the type of intervention) and provided targeted interventions (ATER Women). Specifically, the National Plan for Agroecology and Organic Production and the ATER Agroecology and Sustainability Act require that 30 and 50 percent of their contracts be for women, respectively. Different institutions delivered this category of intervention according to the region; it could be delivered by the state Extension and Advisory Service Department (EMATER), local extension and advisory service providers, or NGOs. To be eligible, rural women should be classified as family farmers.Footnote2

The Strengthening of Family Farming Program (PRONAF) aimed to provide credit to family farmers. This program included quotas of 30–50 percent for women (PRONAF Agroecology, PRONAF Semi-arid, PRONAF Microcredit) and targeted credit lines (PRONAF Women, Terra Sol Mulheres, and so on).

The Rural Women Producers Organization Program (POPMR) aimed to foster the creation of women farmers’ associations.

The Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index

The wide range of definitions and values associated with empowerment reflects multiple worldviews. This diversity invites much criticism from scholars, leading to disagreements about the transformative effect of initiatives claiming to promote empowerment and how they are exerted on people’s lives (Chopra and Müller Citation2016). Considering the context of our target region, we frame empowerment as a process that challenges power relations (Batliwala Citation1994), promoting the expansion of choices for people who have been denied this opportunity (Kabeer Citation1999). Similarly, we believe that empowerment is not a fixed state, but rather a dynamic process that can be attained either individually or collectively, and that it is shaped by the circumstances and resources that women have at their disposal (Cornwall and Edwards Citation2014), and multidimensional phenomenon (Hanmer and Klugman Citation2016). Furthermore, and in line with Sarah Dupuis et al. (Citation2022), we see empowerment as a continuous and iterative process, where each stage contributes to further empowerment – meaning if this process is disrupted, women can find it difficult to keep on the empowerment pathway (Dupuis et al. Citation2022).

To measure empowerment, we used the WEAI, which measures women’s empowerment in the agricultural sector through a household survey focusing on women’s agency.Footnote3 Since its launch in 2013, this methodology has been adapted and widely used to provide empirical and comparable quantitative measures of women’s empowerment within a specific agricultural sector, such as the Women's Empowerment in Livestock Index (WELI; Galiè et al. Citation2019) or to assess empowerment at project level (PRO-WEAI; Malapit et al. Citation2019). For example, to be more comprehensive, the PRO-WEAI has included indicators related to gender-based violence against women, mobility, and intrahousehold harmony that were not assessed in previous versions (Malapit et al. Citation2019).

The WEAI is an aggregate index based on individual-level data collected by interviews with men and women within the same households and comprising a weighted average of two sub-indexes. First, the five domains of the empowerment (5DE) sub-index are calculated based on ten indicators, which determine whether women are empowered (or not) based on information captured in the five domains: (1) decisions about agricultural production, (2) access to productive resources, (3) control over the use of income, (4) leadership, and (5) time allocation (reproductive and productive work; Alkire et al. Citation2013). As explained by Sabina Alkire et al. (Citation2013), an individual is identified as empowered if he or she has adequate achievements in four of the five domains and enjoys adequacy in some combination of the weighted indicators that sum to 80 percent or more. The second sub-index, the Gender Parity Index (GPI), provides information on the relative inequality between the primary women and men in each household.

This study used the Abbreviated Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (A-WEAI; Malapit and Quisumbing Citation2015). This shorter, simplified version maintains the five domains of empowerment but reduces the number of indicators from ten to six. This modification reduced the complexity and time involved in administering questionnaires (Malapit and Quisumbing Citation2015), particularly useful in challenging environments. See Hazel J. Malapit et al. (Citation2015) for more details about the calculation of the A-WEAI. It is worth noting that in this study, we used the WEAI methodology to capture a “snapshot” of the level of empowerment in agriculture during a specific period, under certain circumstances that may vary. As previously mentioned, empowerment is a dynamic and complex process, subject to both positive and negative influences from various factors.

Additionally, we adapted this tool to the context of this study (see Table ). First, we changed the inadequacy cutoffs of the “ownership of asset”Footnote4 indicator from one major asset to three major assets. The changes were made to capture some of the changes in Brazil during the workers’ party administration in terms of increased consumption by poor households and women’s access to land. For instance, according to Sandro Sacchet de Carvalho et al. (Citation2016), an analysis of consumption patterns in Brazil from 2003 to 2013 demonstrated that the improvement in households’ incomes during the period had driven the increased purchase of durable goods (such as means of transportation, and so on). Likewise, several legal instruments potentially affected this indicator; one example is establishing women’s land rights legislation (Butto et al. Citation2011; Deere Citation2017). For example, Administrative Resolution 981/2003 makes joint adjudication to couples mandatory (whether married or in a consensual union) in land reform (Deere Citation2017). The increased consumption of households and the guarantee of women’s legal access to land are examples that could directly affect the assets indicator since these categories (for example, land, fridges, mobile phones) are major assets. Second, we use a more conservative inadequacy cutoff for the “group membership” indicator, which captures the participants’ association with non-religious groups. These changes were based on this study’s exploratory phase, which suggested high participation in religious groups in the region. We decided to change the cutoff of this indicator to capture respondents’ participation in farming and community organizations and social movements.

Table 1 Five domains of empowerment in the A-WEAI adjusted

METHODS

This article uses a mixed-method approach to study women’s empowerment (O'Hara and Clement Citation2018; Bonis-Profumo et al. Citation2022). This methodology allows capturing factors associated with empowerment through quantitative analysis, using qualitative methods to help us understand the conditions underlying women’s empowerment in greater depth.

Study area: Chapada do Apodi, northeast of Brazil

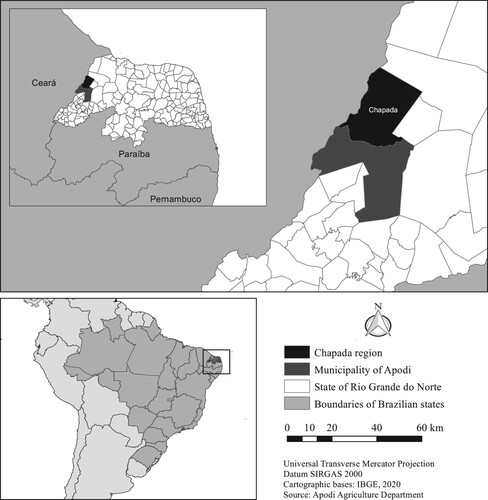

Chapada do Apodi is an area in the states of Ceará and Rio Grande do Norte in Brazil (Figure ). This study was conducted in the district of Apodi, which is part of the Chapada do Apodi, located in the state of Rio Grande do Norte. This region has a semi-arid climate, and caatingaFootnote5 is the primary biome. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE; Citation2020), the district of Apodi covers 1,602.477 square kilometers and has 35.904 inhabitants; 49.0 percent of the population live in rural areas, and 48.1 percent of the rural residents are women.

Most smallholder farmers practice rain-fed agriculture. In this region, about 89.1 percent of the farms are family farms, with an average area of twelve hectares – a figure lower than the national average for smallholder farms, which is eighteen hectares (IBGE Citation2006). Chapada has approximately 800 family farms divided into fifty-five communities,Footnote6 and their predominant farming activities are crops (such as maize, beans, rice, and cassava), beekeeping, and livestock (mainly goat and beef cattle). Chapada do Apodi is acknowledged as a thriving area of agroecology and a national model of agroecological production in a semi-arid climate (Moura and Moreno Citation2013).

The typical experience of rural men and women in Chapada do Apodi is similar to that in other rural areas in Northeast Brazil. The men’s role as the breadwinner is a central characteristic of gender norms in this region of Brazil (Mayblin Citation2010). Women usually marry young and are responsible for bearing and rearing children, growing food in their backyards, and making processed products for household consumption or to sell. They work with men on the family plot.

Qualitative data collection and analysis

The qualitative component of this study aimed at capturing nuances of the context and the impact pathways of the assessed interventions, as recommended by Corey O’Hara and Floriane Clement (Citation2018). The research was conducted over two stages. In the first stage, we conducted key informant interviews (KIIs) with seven policymakers at the central government level and ten local leaders in August 2015. The KIIs were conducted to inform the design and adaptation of the A-WEAI survey. The second stage was conducted in November 2015, after the quantitative survey was completed. In this stage, we conducted two focus group discussions (FGDs) with eight participants each to examine and expand the survey’s preliminary results. Participants of the FGD were women farmers from the communities in this study.Footnote7 We used semi-structured approaches for both methods. All KIIs and FGDs were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed in Portuguese using NVivo. Researchers used grounded theory methodology to analyze the transcripts (Charmaz Citation2014).

Quantitative data collection and analysis

Quantitative data were collected from six communities in the Chapada area in the district of Apodi (Figure ) from September-November 2015. The sampling process was divided into two stages. In the first stage, we mapped the communities (the number of family farms and their localizations) using the categories of land reform and non-land reform farmers. We contacted local institutionsFootnote8 to gather information on family farms (number, location, agrarian reform) in Chapada do Apodi. Information gathered from these institutions was compiled in a single database.

In the second stage, we identified the communities (clusters) based on the mapping process. We then sampled the target region. The sample was selected randomly, applying a cluster-sampling design, using the categories land reform and non-land reform farms in our database. Using this approach, six communities were randomly selected (three communities in each category). Once the communities were identified, we interviewed all households within them, resulting in a sample of 152 households. All households in the sample had a primary man and woman.

The questionnaire used in this study was based on the A-WEAI survey, with additional questions to collect individual data on demographic information, farming activities, and access to interventions. The surveys were administered separately to members of couples (primarily a man and woman) in rural households, and the data was used to calculate the overall WEAI score. To estimate the interventions associated with women’s empowerment in agriculture, we used only the data from women respondents.

Statistical framework

To determine the drivers of women’s empowerment, we used a recursive multivariate probit approach (Greene Citation1998). Imagine a woman i (i = 1, … , N) of characteristics di, working in agriculture. Empowerment, , is latent and measured by a binary (dummy) variable

, such that for an empowered woman

, and 0 otherwise. The vector

contains two subsets of variables: a first subset wi refers to factors that exogenously explain empowerment (for example, age and education); a second subset xi refers to variables that endogenously determine empowerment. Several studies investigating women’s empowerment indicate a potential endogeneity bias in their analysis, primarily driven by reverse causality (Allendorf Citation2007; Garikipati Citation2012; Sraboni et al. Citation2014; Johnston et al. Citation2015; Malapit and Quisumbing Citation2015). A set of unobservable confounders influence both the empowerment score and the endogenous variables. For instance, women in agriculture with a higher level of empowerment may be more confident, therefore more likely to also be direct beneficiaries of credit and access extension services – in this example, confidence rather than credit would be the cause of the empowerment.

To address this endogeneity problem, we used a recursive multivariate probit. In a context with two endogenous variables and

, the model is specified as:

(1)

(1)

where

,

, and

are equation-specific covariates. The error terms

are multivariate-normally distributed with variance-covariance matrix

, where ρ represents the correlations between the residuals (Cappellari and Jenkins Citation2003). Equation 1 is estimated by simulated maximum likelihood using the Geweke-Hajivassiliour-Keane (GHK) approach, which simulates the multivariate normal distribution using a smooth recursive simulator.Footnote9 In multivariate probit models, a test for endogeneity corresponds to testing whether the parameter ρ equals zero (Schneider and Schneider Citation2006): the null hypothesis of exogeneity,

, can be tested using the statistic

, where

is the asymptotic standard error of

, and z is

distributed, with the same critical values as the Hausman test (Knapp and Seaks Citation1998; Schneider and Schneider Citation2006).

Three factors drive the choice of a multivariate probit. First, both dependent and endogenous variables are binary, and a linear model will lead to inefficient estimates of the parameters of the equation (Greene Citation1998). Second, the simultaneous estimation of the three probit equations is more efficient than two-step approaches, which are based on a mis-specified likelihood function in the second step of the probit regression (Arendt and Larsen Citation2006; Bhattacharya, Goldman, and McCaffrey Citation2006; Monfardini and Radice Citation2008; Freedman and Sekhon Citation2010). Third, endogeneity correction in a multivariate probit does not require additional instruments to identify the parameters in the system (Maddala and Lee Citation1976; Wilde Citation2000; Roodman Citation2009; Velandia et al. Citation2009).

Model: Factors associated with women’s empowerment in agriculture

The previous section presented a generic model of empowerment. In this section, we specify the variables used in the model to characterize the context of the case study. Table presents the correspondence between the variables presented above. The precise definition of each of the variables is presented in the following subsections.

Table 2 Variables in the multivariate probit model

The main equation of this study can be specified as:

(2)

(2)

where

= 1 if the woman is empowered in agriculture (0 otherwise). In Equation 2, de identifies a vector of demographic characteristics (age and years of education), agr is a dummy variable that indicates whether the production system on the farm is agroecological (0 otherwise), and gr identifies whether the woman respondent participates in a women farmers’ association (0 otherwise). Equation Equation(2)

(2)

(2) also includes two endogenous variables: cr indicates whether the woman has access to credit as a beneficiary of rural development credit lines (1 = yes, 0 otherwise), and ex shows whether the woman farmer has access to extension services (1 = yes, 0 otherwise).

The system of the equation includes two additional instrumental equationsFootnote10 for the two endogenous variables, women’s access to credit and extension services, specified as follows.

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

In Equation 3, pc = 1 indicates if the male in the household had access to credit; and dap identifies whether the woman respondent had the eligibility declaration (known as DAP) required to access the rural development programs (1 = yes, 0 otherwise). In Equation 4, wr indicates whether there is a cistern on the farm (1 = yes, 0 otherwise); and wp is a binary variable identifying whether the primary woman describes herself as responsible for any agricultural activity on the farm.

Variable descriptions

(a) Empowerment in agriculture (emp)

This dummy variable is based on the individual empowerment scores computed using the WEAI methodology. The individual score is calculated according to the respondent’s achievements on the WEAI indicators and compared with the respective inadequacy cutoff (Table ). This variable allows the identification of empowered individuals in the sample; we assigned a value of 1 to the empowered and 0 otherwise.

(b) Access to targeted credit lines (cr)

This variable equals 1 if the woman has been a beneficiary of targeted credit lines provided by national rural development programs in the previous two years (0 otherwise). In contrast to the credit access indicator of the WEAI, which assigns a 1 if anyone in the household could access any credit, this variable identifies whether the women specifically accessed rural credit lines provided by rural development programs.Footnote11 Recent studies suggest that women’s access to rural development credit lines fostered the process of empowerment in Brazil (Santos Citation2020; Spanevello et al. Citation2021).

(c) Woman’s access to extension services (ex)

This variable equals 1 if the participant had access to extension services provided by the rural development programs in the past two years (0 otherwise). In the analyzed context, extension services provide information to women and guide them in applying agricultural techniques in groups and associations, providing support to access other rural development interventions. Studies suggest that access to extension services positively impacts economic autonomy (Cornwall, Guijt, and Welbourn Citation1994; Strate and da Costa Citation2018).

(d) Demographic variables (de)

Demographic variables are three dummy variables: a variable indicating whether the participant was in the 31–60 years age range; a second, identifying those ages 61 or older (baseline: person ages 15–30 years); and finally, education referred to a dummy variable equaling 1 if the woman had >4 years of formal education (0 otherwise).

(e) Agroecological production (agr)

This variable equals 1 if the household declared to adopt agroecological practicesFootnote12 on their farm (0 otherwise). Literature suggests a positive association between adopting agroecological practices and women’s empowerment in Brazil, because Brazilian agroecology programs promote the visibility of the role of women in the adoption of alternative agricultural production methods, environmental production, and food safety (Siliprandi Citation2011; Brito and do Nascimento Citation2020).

(f) Women’s farmer organizations (gr)

This variable equals 1 if the respondent participated in a women’s farmer organization (associations, producer groups, cooperatives) in the last five years (0 otherwise).Footnote13 Research shows that membership in a women’s group increases the likelihood of participating in decision-making processes (Mwambi, Bijman, and Galie Citation2021), and enhancing women’s self-confidence along with involvement in economic activities (Baden Citation2013; Evans and Nambiar Citation2013).

(g) Partner’s access to credit (pc)

This variable equals 1 if the man in the household accessed rural credit provided by rural development programs (0 otherwise), as access to credit from a partner could influence the likelihood of the woman’s access to credit (for example, through sharing information or contacts).

(h) Woman’s DAP (dap)

This variable equals 1 if the women had DAP, a document rural women need to access the government’s rural development programs (0 otherwise). Studies have suggested that DAP double titularity was a crucial milestone for women to access rural development credit in Brazil (Filipak Citation2017).

(i) Cisterns (wr)

This variable equals 1 if the woman farmer had access to a water reservoir (0 otherwise). Access to cisterns is important for producing vegetables in the home garden and hennery (typically a women’s activity), saving women’s time from collecting water daily, especially during water shortages (de Moraes and Rocha Citation2013).

(j) Woman’s agricultural production (wp)

This variable equaled 1 if the women reported being responsible for any agricultural activity (0 otherwise). This variable was included because if women reported overseeing an agricultural activity, this would increase the likelihood of accessing extension services.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Description of survey results

The survey collected data from 152 households. Table summarizes the statistics for the variables in our analysis. The A-WEAI score was 0.86,Footnote14 and 62.8 percent of the women in the sample qualified as empowered. In the sample, 19.6 percent had received extension services, 35.2 percent participated in women farmers’ associations, and 34.9 percent had obtained rural development-targeted credit in the preceding five years. Sixty-three percent of the women in the sample belonged to land reform settlements. In terms of age, 69.0 percent were between 31 and 60, and 21.6 percent had received more than four years of education; no respondents had completed secondary education. The farms in the sample widely adopted agroecological practices (88.8 percent). Sixty-four percent of the women stated that they had DAP, 68.7 percent of the women reported being responsible for any agricultural activity, and 86.8 percent had access to cisterns. Agricultural activities were the main source of income for 15.7 percent of households. The low importance of agriculture for the rural household’s income in the sample may be associated with the prolonged drought period that the region faced during the data collection, which impacted the local agricultural production. According to the respondents, 58.4 percent reported that conditional cash transfer program (Bolsa Familia), and 21.4 percent said that waged work was the main source of income (4.5 percent said they did not have any source of income).

Table 3 Distribution of sample characteristics for women (n = 152)

Factors associated with women’s empowerment in agriculture

Table presents the results of the recursive multivariate probit model. The last column of Table presents the results of the univariate probit estimation of the empowerment equation for comparison. Wald’s chi-square test indicates that the model has significant explanatory power (p < 0.001). Exogeneity was rejected using a likelihood ratio test, with (see Table ). The multivariate probit model indicates that age, education, adoption of agroecological practices, and participation in women farmer’s associations were not significantly associated with individual empowerment in agriculture.

Table 4 Summary of multivariate and univariante probit estimation: Factors associated with empowerment in agriculture in Chapada do Apodi

Our results showed that women’s access to rural development credit lines was significantly positively associated with empowerment in agriculture, providing clear, quantifiable evidence of the importance of targeted credit interventions. The marginal effect of the multivariate probit estimation indicates that women with access to the rural development credit lines were 31.6 percent more likely to be empowered in agriculture.Footnote15 While the relationship between women’s empowerment and credit access has been widely examined in the literature (Hashemi, Schuler, and Riley Citation1996; Mehra et al. Citation2012; Fletschner and Kenney Citation2014). The literature on credit and women’s empowerment has shown contradictory results, partially because of the wide variability in the treatments assessed, but also because of a lack of standardized empowerment metrics. However, a recent study conducted in Ethiopia using the pro-WEAI has demonstrated that long-term access to the studied credit program positively impacted women’s empowerment (Hillesland et al. Citation2022). Similarly, another recent study in rural India has suggested a positive relationship between credit access and women’s empowermentFootnote16 (Pal and Gupta Citation2023). Importantly, our results align with qualitative studies conducted in Brazil, which show an association between women’s empowerment and credit (Santos Citation2020; Spanevello et al. Citation2021).

Likewise, the extension services variable was significantly and positively associated with individual empowerment in agriculture, in line with the literature highlighting that access to extension services is essential for women’s empowerment (Cornwall, Guijt, and Welbourn Citation1994; Ragasa Citation2014). The marginal effect on the multivariate probit estimation indicates that a woman who accesses extension services in Chapada do Apodi is 38.5 percent more likely to be empowered in agriculture. This finding is in alignment with a recent study that found a strong positive association between women’s access to extension services (knowledge about animal health) and women’s empowerment using the WELI index in Ghana (Omondi et al. Citation2021). Similarly, in another study using the pro-WEAI, Waid et al. (Citation2022) showed that training to improve home gardening and poultry-rearing practices promoted empowerment and closed the gender gap among the beneficiary’s households. The estimated coefficients of equation Equation3(3)

(3) indicate that the access to extension services is positively and significantly associated with accessing a water reservoir and the woman farmer’s claim to be responsible for at least one agricultural activity on the farm.

The marginal effects of the univariate probit regression indicate that empowerment in agriculture increases with rural development credit lines (18.5 percent) and extension services (39.7 percent). Both multivariate and univariate probit regressions present positive statistically significant outcomes. However, when comparing the marginal effects of these two models, the results reveal that neglecting the endogeneity bias leads to an underestimation of the impact of rural development credit access on women’s empowerment in agriculture by 13.1 percent. Conversely, it leads to an overestimation of the relevance of access to extension services for women’s empowerment in agriculture by 1.2 percent. In other words, neglecting the endogeneity can potentially lead to inaccurate policy recommendations that will fail to address the actual needs of the targeted rural population.

We recognize that the survey sample size is relatively small (n = 152), which limits the generalizability of the analysis. Additionally, women that are not engaged in agriculture may be identified as “disempowered” because of their lack of participation in decision-making in activities related to the farm’s production, and this would impact the indicator “production” (Alkire et al. Citation2013).

Empowerment beyond the access to interventions in the Brazilian semi-arid

The women in Chapada do Apodi achieved high scores in the A-WEAI (0.86). The model results show that access to rural development-targeted credit lines and extension services was associated with women’s empowerment in agriculture. While previous studies have shown that access to credit and extension services could trigger and reinforce women’s empowerment, studies explicitly exploring these interventions’ association in semi-arid contexts are lacking. Our qualitative findings suggested that it was not merely access to credit or extension services affecting rural women’s empowerment in the region. How these interventions were designed (at the national level) and delivered (at the local level) was central to the association between these interventions and women’s empowerment.

Alliances to foster rural women empowerment

The participants of this study consistently mentioned that cooperation between the rural women policy agency (DPMR) and rural women’s movements was essential for designing interventions that attended to rural women’s needs in Brazil, as remarked by one of the study’s informants:

The situation of rural women in Brazil started to change when they [the state] started to listen to us. We told them what we needed and … the situation we were in, and little by little, we came up with a plan … I am not saying that it [the relationship with the DPMR] has been easy. In fact, it was an arduous process, but I believe [that for] our common goal [to improve rural women’s lives], we overcame the barriers and constructed a productive partnership. (Rural women’s movement informant, director)

This extract illustrates a women’s movement leader’s perception of their participation in the policy process and influences on policy goals. Interviewees also mentioned that this alliance was essential in adjusting and shaping mechanisms to improve women’s access to interventions across different contexts. Research suggests that two factors determine the effectiveness and success of policies developed and implemented by women's policy agencies. First, the extent of collaboration and partnership between these agencies and women's movements, and second, the degree to which women's movements are included in the policymaking process (Mazur and McBride Citation2007; McBride and Mazur Citation2010). During the Workers’ party administration, the DPMR strengthened participatory policymakingFootnote17 processes (locally and nationally) and used them as platforms to establish (and advance) the interaction between the state and civil society, as mentioned below:

We understood that the participation of civil society groups was essential to progress in rural women’s status. To do … so, in the last thirteen years [2002–2015], we created several channels to foster the dialogue at the local and national [levels], such as councils, committees, working groups, and conferences. But it is not sufficient to only create spaces for dialogue. We need to make sure that all relevant actors are participating. In the beginning, it was difficult. Of course, it was new, but little by little, we adjusted, and I am not saying that it is perfect and harmonious, but we understand that this relation [the state and women’s movements] is central to the advance in the rural women’s status in Brazil. (Policymaker informant, general director)

According to our interviewees, participation in civil society was not restricted to policy design; it also included monitoring and evaluation, which is essential for addressing issues impacting rural women’s lives. These findings align with the literature about rural women in Brazil (Heredia and Cintrão Citation2012; Bohn and Levy Citation2019). For example, Beatriz Maria Alásia Heredia and Rosângela Pezza Cintrão (Citation2012) argue that the women’s movement participated in both design and implementation, providing feedback and monitoring activities that permitted policymakers to detect barriers and change its mechanisms to attend to rural women better. Simone Bohn and Charmain Levy’s (Citation2019) findings corroborate our results by showing that the policymaking process in this period was developed through a feminist strategic partnership fostering the advancement of the rural women’s movement agenda. In conclusion, the collaboration between the government and the women's movement was imperative in delivering interventions that were specifically designed to advance the autonomy of rural women and enable their participation in national-level decision making, thereby enhancing their voices and legitimacy.

Feminism and extension services in the semi-arid

This study considers empowerment a process that challenges power relations (Batliwala Citation1994) and progress toward expanding choices for people previously denied this opportunity (Kabeer Citation1999). Our quantitative results suggested an association between access to extension services and empowerment. In this line, our qualitative results suggest that using feminist pedagogy and popular education to implement interventions was crucial for raising women’s consciousness in the region. The fact that a local NGO called Feminist Centre 8 of March (CF8)Footnote18 implemented women-targeted interventions, especially extension services, and women’s organizations, was central to rural women’s consciousness enhancement in the studied area. The CF8 organized regular meetings confronting issues such as violence against women, sexual and reproductive rights, land rights, and the gender division of labor as part of the extension services and training. Our focus groups nearly unanimously reported that the awareness-raising and training provided in the meetings promoted by the CF8 changed their lives, as remarked by one of the study’s participants:

I think that much of the positive change in our lives is thanks to the women from the CF8. They had been supporting us, opening our eyes to our rights. They help us in many things here [the community]. They provide extension advisory to our home garden production, hennery, and vegetable gardens. Another day, they arrived here to process fruits to make homemade jams. We did not know much about it before. After this, we sold jam in the village. (Woman farmer, 36)

The following quotes illustrate the NGO’s importance to participants in women’s rights:

Our situation [women in the community] has improved 100%. In the past, here, women had no freedom. It started to change through our participation in the meetings [women’s group meetings]. By then, we started to be aware that we also have rights. We had no idea. Today many women feel free around here. I feel free because I know my rights. I can go everywhere if I want, even if my husband does not agree. I stand for my right and do not let him prevent me anymore. My husband is very “machista,” but I always say: “your rights stop here because here is where mine begins.” (Woman farmer, 59)

Our results show that integrating a gender awareness education component in implementing interventions is a powerful tool to change women’s status. The impact of the methodology the CF8 used has been reported in previous studies exploring other interventions. For instance, Andrea Ferreira Jacques de Moraes and Cecilia Rocha (Citation2013) show that the CF8 was a key element in the transformational process of accessing interventions in the region. Dominique Masson and Elsa Beaulieu Bastien (Citation2021) argue that the CF8 anchoring the implementation activities in feminist consciousness-raising practices was crucial for rural women’s economic empowerment and recognition in the region. Moreover, our results suggest that rural women's participation in the political sphere through involvement with important national feminist movements in Brazil can serve as a crucial avenue for rural women’s empowerment as facilitates them to have a voice in policymaking and contribute to the development of policies that address their needs and challenges (such as World March of Women, Daisy’s March). According to Emma Siliprandi (Citation2009), rural women’s participation in feminist movements was essential to women’s empowerment in the region.

Our qualitative results align with those of a previous study in the region, arguing that extension services promoting gender-sensitive education can positively impact women’s empowerment (Schwendler and Thompson Citation2017; Feitosa and Yamaoka Citation2020).

Mechanisms of support in the semi-arid

Our qualitative results also show that credit availability was essential for rural women to build resilience and overcome periods of drought. The informants mentioned that they especially look for access to credit to mitigate the effects of the drought and avoid the depletion of their assets. Almost half of the participants of the focus groups reported having access to different lines of credit offered by the government, and credit enabled them to buy agricultural inputs to support their production and buy feed for livestock during the drought. Access to credit is important to prevent the depletion of resources, which is crucial for the aftershock period and a determinant in the recuperation of agricultural activities.

In the last few years, I have been accessing credit every six months to buy forage to feed my goats and cows. My husband always says to me to sell them. I need to get credit … because how can I buy other animals? Thank God I’m managing to pay the installments. I will finish paying the last one [installment], and I will make another one [loan]. I renew it [loan] every six months because my animals will not be punished for this drought. (Woman farmer, 37)

This quote illustrates the importance of credit access during periods of drought. Previous studies show that the depletion of assets during drought undermines smallholder farmers’ chances to recover. In extreme cases, it can result in permanent migration to urban areas (Agarwal Citation1990; Kabeer Citation2015). Its importance is even more significant in the case of women’s economic activities. Our study suggests that the fact that the women had access to targeted credit lines, and could access them independently of their husbands, helps them mitigate the negative effect of droughts on their productive assets. These findings align with previous studies showing that access to resources in climate-vulnerable areas can improve women’s bargaining power and contribute to adapting and mitigating negative effects on their households (Ajani, Onwubuya, and Mgbenka Citation2013). However, it is important to highlight that the buffer effect against shocks should be considered a mitigation strategy and that a set of policies/interventions should be implemented to build resilience between drought events (Quisumbing, Kumar, and Behrman Citation2018). Policies aimed at building resilience in rural areas can encompass a range of interventions such as investing in sustainable agriculture practices, improving access to water resources for local populations, providing education and training opportunities for farmers, and diversifying income-generating activities. Moreover, strengthening social networks and empowering local communities can foster resilience and enhance adaptive capacity to cope with future shocks in rural areas.

Our findings align with previous studies suggesting that access to credit in semi-arid areas has different functions: (1) before the strike, credit provides resources to invest in technologies and structures that can minimize adverse impacts when a crisis occurs; (2) during the crisis, it helps mitigate the effects of the drought and improve people’s ability to recover; and (3) after the strike, it aids in repairing damages and enhancing preparedness for the next crisis (Enarson Citation2012; Austin and McKinney Citation2016).

Our model estimation did not show any association between participation in women farmers’ associations and empowerment. However, the qualitative findings suggested that participation in mixed-group associations was important to overcome the drought period. All the participants in the focus groups mentioned that they participated in farmers’ associations (mixed or women-only). The participants mentioned that they purchased equipment through a mixed farmer association to cope during the drought and feed their livestock, for example, purchasing new equipment to cut forage cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica) to feed their animals. This may be because the mixed farmer associations had more resources than the women’s only group and were able to facilitate access innovations to overcome the drought period. The following quote illustrates the importance of the association to one participant:

Through the association, we can get things. It is easy together. It was a blessing. Last year, we managed to get the equipment to prepare the feed for the livestock. Through them, we managed to negotiate better prices to buy feed. At least the cattle are not dying. If we did not have this help, we would need to sell our goats and cows. Then after [the period of aftershock], how will we do? (Woman farmer, 43)

The effect between participation in associations and empowerment has been reported previously (Bratton Citation1987; Little et al. Citation2006; Enfors and Gordon Citation2008). According to Michael Bratton (Citation1987), participation in farmer’s groups during drought periods is a significant advantage, as these organizations can facilitate access to packages of services such as credit and innovation, making it easier for association members to access these services than if they were to solely work as farmers.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Women’s empowerment in rural areas has been an issue of increasing interest among academics, development agencies, and governments worldwide. Building up agriculture’s resilience to climate change in semi-arid areas depends on recognizing the role of women and encouraging their empowerment. Empowerment can make rural women and their households more resilient to the adverse effects of climate change. This study's contributions lie in using a robust methodology to identify factors affecting women's empowerment in a drought-prone area in Brazil, where previous studies have primarily utilized qualitative approaches. While our qualitative findings align with previous studies on women's empowerment in the region, our research stands out due to the novel integration of quantitative methods, specifically the WEAI. Our results provide a fresh perspective to our understanding of women's empowerment in agriculture in this region. Moreover, This study contributes to the literature on women's empowerment. It showcases how elements such as participatory policymaking, the use of feminist pedagogy, and the application of popular education can be used in interventions. These strategies are particularly critical in semi-arid regions prone to drought crises, suggesting that they can foster significant empowerment for women in these areas.

The quantitative results indicate that women in the region achieved high A-WEAI scores. Our model estimation suggests that empowerment in agriculture is driven by women’s access to targeted rural development credit and access to extension services. Our qualitative findings add a layer by shedding some light on the mechanisms contributing to these associations and beyond to understand the case study context. In line with previous literature, our qualitative results suggest that some conditions in the Brazilian semi-arid context were central to the abovementioned results. We identified that the participatory approach adopted by DPMR, fostering the participation of rural women’s movements and other actors in the design and monitoring of the rural-women policy portfolio, was crucial to achieving women’s empowerment. Alliances that allowed the rural women’s movement’s participation in the policy process were essential to achieve programs that translated the demands of rural women. Our study highlights that the adoption of participatory mechanisms in policymaking can not only address the barriers to rural women's inclusion in sustainable rural development but can also contribute to the promotion and protection of their rights.

CF8’s role in intervention delivery was essential to the performance found in the case study. Our case study shows that including feminist pedagogy and popular education in implementing interventions (for example, an extension service or women’s organization) was central to rural women’s consciousness enhancement. The intervention delivery process included practices crucial for consciousness-raising regarding gender relations and the rights of local women. In the execution of this study, it became clear that empowerment could not be achieved without including methodologies that develop critical thinking and enhance awareness about issues such as violence against women, sexual and reproductive rights, freedom of movement, land rights, and gender division of labor, considering the condition in the given context.

This study offers a glimpse into women's empowerment in agriculture in a drought-prone region during a particular period. However, as mentioned earlier, empowerment is an ongoing and dynamic process and cannot be bestowed, but only facilitated. Therefore, promoting rural women's empowerment requires a comprehensive approach that considers the multifaceted barriers women face and the use of methodologies that encourage critical thinking and enhance gender awareness.

It is worth noting that this study was conducted during a critical period in Brazilian history when significant efforts were made to combat poverty and promote social change. During this time, several marginalized groups, including rural women, gained visibility in the political landscape. However, political turmoil in Brazil from 2016 onward, culminating in the impeachment of President Dilma Roussef, and subsequent administrations with divergent views until 2022, had a detrimental effect on the empowerment of all marginalized groups in Brazil. The dismantling of the Ministry of Agrarian Development and other institutions resulted in a significant regression in political and human rights for marginalized groups. In light of the significant contextual changes that have taken place, future research must investigate how these changes have affected the empowerment process of women in the northeast region of Brazil.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the CAPES/CNPq under the Science without Borders Programme (BEX1190513). In addition, we thank the Newcastle University Researcher Centre for Latin American and Caribbean Studies (CLACS) for mobility support in the fieldwork. We would like to thank Dr. Conceição Dantas (The Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte) and Ms. Ivonilda de Souza (leader of the farmers’ association juntas venceremos) for their support during the conduction of this study. We also thank the Centro Feminista 8 de Março (CF8), Sindicato dos Trabalhadores e Trabalhadoras Rurais de Apodi (STRRA), and all smallholder farmers of Chapada do Apodi for their collaboration. We are also grateful to Dr. Chris Tapscott for his helpful comments and suggestions. We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable insights and comments, which greatly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Erika Valerio

Erika Valerio is Research Fellow at the School of Environmental and Rural Science at the University of New England. Erika is a rural development researcher whose expertise spans the diverse sectors of agriculture, gender, innovation, and value chain development on focused projects. She has substantial experience using mixed methods approaches for policy and program evaluation. She also has several years of experience conducting research in different countries across Southern Africa, Southeast Asia and Latin America working for different multilateral agencies. Erika holds a PhD in rural development from Newcastle University.

Luca Panzone

Luca Panzone is a food economist who holds a senior lectureship in consumer behavior at Newcastle University and is a fellow of the Alan Turing Institute, specializing in food economics and marketing. His research interests focus on the analysis of social problems related to agriculture, food, and the environment. Methodologically, he derives insights from quantitative methods, including the analysis of very large datasets, and from experiments in the lab and field.

Emma Siliprandi

Emma Siliprandi holds a PhD in sustainable development (Universidade de Brasilia, Brasil/Universidad de Valladolid, Spain) and a Master’s in sociology. She has been a FAO agricultural officer since 2013 and the lead focal point for the Scaling-Up Agroecology Initiative for the last four years. Emma is a researcher and visiting professor of PhD and master’s courses in agroecology in Spain and Brazil, among other countries.

Notes

1 Later, we elucidate our interpretation of empowerment within the context of this study.

2 According to the federal law n° 11.326, July 24, 2006, a family farmer is engaged in farming activities and meets the following criteria: (1) Hold an area of up to 4 (four) fiscal modules, (2) use only family labor, and (3) percentage of the income comes from agriculture activities.

3 This methodology was developed by researchers at USAID, IFPRI, and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) to monitor changes in women’s empowerment status in regions served by Feed the Future, the US government’s global hunger and food security initiative (Alkire et al. Citation2013).

4 Major assets are defined as agricultural land, large animals and livestock, mechanized farm and non-farm equipment, a house, large consumer durables, a cell phone, non-agricultural land, and means of transportation (Alkire et al. Citation2013). In the original version, the individual is considered inadequate if it the household does not own any major assets OR the household owns this type of asset, BUT the individual does not have sole or joint ownership of the asset.

5 Caatinga is a typical vegetation in northeast Brazil, characterized by steppical savanna.

6 These data were provided by the Rural Workers Union of Apodi (Sindicato dos Trabalhadores e Trabalhadoras Rurais de Apodi, or STTRA).

7 More detail on the selection of the communities selected is provided below.

8 To map the region, we gathered information from several institutions, such as the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA), the Secretary of Agriculture of Apodi, and the Rural Workers Union of Apodi (STTRA).

9 To estimate the multivariate probit, we used the statistical software Stata 13 – command mvprobit, which estimates M-equation probit models by simulated maximum likelihood (SML). The variance-covariance matrix of the cross-equation error terms presents correlations on the off diagonal and 1 on the main diagonal. To access the M-dimensional normal integrals in the likelihood function mvprobit, one can use the Geweke-Hajivassiliou-Keane (GHK) simulator

10 We also tried a four-equation system of equations, using the variable gr (whether the woman participates in a women farmers’ association) as an independent variable; we dropped this fourth equation because we could not find endogeneity using using an adapted Hausman test (Knapp and Seaks Citation1998).

11 There are differences between the WEAI indicator “access to credit” and the explanatory variable “access to the targeted credit line.” The former addresses the following points: (1) whether anyone in the household had restrictions to access to credit; (2) whether anyone in the household had accessed credit in the last year; (3) who decides to borrow; and (4) who decides what to do with the loan. In contrast, the study’s explanatory variable indicates whether women in the household were the direct beneficiary (which means that they were the ones who had received the credit) of rural development–targeted credit lines. The question to assess this information was, “Have you been a beneficiary of a credit line targeted to agricultural production/rural development in the last twelve months as part of rural development programs?”

12 In this study, we used a definition of agroecology and its practices provided by FAO. Agroecology is an integrated strategy that simultaneously applies ecological and social concepts and principles to the design and management of food and agricultural systems. It aims to optimize the interactions between plants, animals, humans, and the environment, considering the social factors that must be addressed for a sustainable and equitable food system.

13 As pointed out earlier, the group membership module of the WEAI methodology was adapted to collect information on participation in mixed farmers’ organizations for men and women.

14 Using the original inadequacy cutoffs, the overall A-WEAI score goes up to 0.89, with 70.2 percent of women considered empowered, and 71.1 percent with gender parity in their households. This study uses the WEAI classification provided by a baseline report that estimates scores from 13 countries, categorizing the scores as high (> 0.85), medium (0.85 to 0.75), or low (< 0.75; Malapit et al. Citation2014). As a reference, Malapit et al. (Citation2014) reports that Bangladesh and Cambodia were placed at the two extremes of the ranking, the former with a score of 0.66 and the latter with a score of 0.98.

15 The standard errors of the estimated marginal effects refer to bootstrapped standard errors.

16 Pal and Gupta's study aimed to determine how credit access affected social, psychological, and economic facets of women’s empowerment in rural India. According to this study, there is a statistically significant association between having access to credit and all dimensions of women's empowerment.

17 Some of the mechanisms for participatory policymaking were created before the Workers’ party administration (Rodríguez Gustá, Madera, and Caminotti Citation2017).

18 The CF8 was founded in 1993 in Mossoró, Rio Grande do Norte. The founders were women from local unions, activists, and students from the women’s health movement, and its initial focus was on preventing violence against women and women’s health (Masson and Beaulieu Bastien Citation2021).

References

- Abid, Zaineb, Muhammad Abid, Qudsia Zafar, and Shahbaz Mehmood. 2018. “Detrimental Effects of Climate Change on Women.” Earth Systems and Environment 2(3): 537–51.

- Agarwal, Bina. 1990. “Social Security and the Family: Coping with Seasonality and Calamity in Rural India.” Journal of Peasant Studies 17(3): 341–412.

- Ajani, E. N., E. A. Onwubuya, and R. N. Mgbenka. 2013. “Approaches to Economic Empowerment of Rural Women for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation: Implications for Policy.” Journal of Agricultural Extension 17(1): 23–34.

- Alkire, Sabina, Ruth Meinzen-Dick, Amber Peterman, Agnes Quisumbing, Greg Seymour, and Ana Vaz. 2013. “The Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index.” World Development 52: 71–91.

- Allendorf, Keera. 2007. “Do Women’s Land Rights Promote Empowerment and Child Health in Nepal?” World Development 35(11): 1975–88.

- Alston, Margaret. 2014. “Gender Mainstreaming and Climate Change.” Women’s Studies International Forum 47(B): 287–94.

- Arendt, Jacob Nielsen and Holm Anders Larsen. 2006. “Probit Models with Dummy Endogenous Regressors.” University of Southern Denmark Business and Economics Discussion Paper 4.

- Austin, Kelly F. and Laura A. McKinney. 2016. “Disaster Devastation in Poor Nations: The Direct and Indirect Effects of Gender Equality, Ecological Losses, and Development.” Social Forces 95(1): 355–80.

- Baden, Sally. 2013. “Women’s Collective Action: Unlocking the Potential of Agricultural Markets.” Oxfam International Research Report.

- Batliwala, Srilatha. 1994. “The Meaning of Women’s Empowerment: New Concepts from Action.” In Population Policies Reconsidered: Health, Empowerment and Rights, edited by Gita Sen, Adrienne Germain, and Lincoln C. Chen, 127–38. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Bayeh, Endalcachew. 2016. “The Role of Empowering Women and Achieving Gender Equality to the Sustainable Development of Ethiopia.” Pacific Science Review B: Humanities and Social Sciences 2(1): 37–42.

- Bhattacharya, Jay, Dana Goldman, and Daniel McCaffrey. 2006. “Estimating Probit Models with Self-Selected Treatments.” Statistics in Medicine 25(3): 389–413.

- Bohn, Simone and Charmain Levy. 2019. “The Brazilian Women’s Movement and the State Under the PT National Governments.” European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies/Revista Europea De Estudios Latinoamericanos y Del Caribe 108: 245–66.

- Bonis-Profumo, Gianna, Domingas do, Rosario Pereira, Julie Brimblecombe, and Natasha Stacey. 2022. “Gender Relations in Livestock Production and Animal-Source Food Acquisition and Consumption Among Smallholders in Rural Timor-Leste: A Mixed-Methods Exploration.” Journal of Rural Studies 89: 222–34.

- Brandão, Tatiana Frey Biehl, Janice Rodrigues Placeres Borges, and Sonia Maria Pessoas Pereira Bergamasco. 2021. ““Perspectivas sobre autonomia e empoderamento das mulheres rurais Sertanejas: Um estudo de caso” [Perspectives on the autonomy and empowerment of rural Sertaneja women: A case study].” Diversitas Journal 6(2): 2762–90.

- Bratton, Michael. 1987. “Drought, Food and the Social Organization of Small Farmers in Zimbabwe.” African Ephemera Collection. https://collections.libraries.indiana.edu/africancollections/items/show/3326.

- Brito, Carina de Moraes Pereira and Priscila Brasileiro Silva do Nascimento. 2020. “Agroecologia e empoderamento de mulheres de uma comunidade Sertaneja do Semiárido Baiano” [Agroecology and empowerment of women in a Sertaneja community of semi-arid Baiano]. Revista de Políticas Públicas e Gestão Educacional (POLIGES) 1(1): 140–66.

- Butto, Andrea, Isolda Dantas, Anita Brumer, Caroline Bordalo, Emma Siliprandi, Laeticia Jalil, Nalu Faria, et al. 2011. Autonomia e cidadania: políticas de organização produtiva para as mulheres no meio rural [Autonomy and citizenship: Productive organization policies for women in rural areas]. Brasília: Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário.

- Cappellari, Lorenzo and Stephen P. Jenkins. 2003. “Multivariate Probit Regression using Simulated Maximum Likelihood.” Stata Journal 3(3): 278–94.

- Carvalho, Sandro Sacchet de, Cláudio Hamilton dos Santos, Vinícius Augusto de Almeida, Yannick Kolai Zagbai Joel, Karine Cristina Paiva, and Luíza Freitas Caldas. 2016. “O consumo das famílias no Brasil entre 2000 e 2013: Uma análise estrutural a partir de dados do Sistema de Contas Nacionais e da Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares” [Family consumption in Brazil between 2000 and 2013: A structural analysis based on data from the national accounts system and the family budget survey]. IPEA, Texto para Discussão, n. 2209.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications.

- Chopra, Deepta and Catherine Müller. 2016. “Introduction: Connecting Perspectives on Women’s Empowerment.” IDS Bulletin 47(1A): 1–15.

- Cornwall, Andrea and Jenny Edwards. 2014. Feminisms, Empowerment and Development: Changing Women’s Lives. London: Zed Books Ltd.

- Cornwall, Andrea, Irene Guijt, and Alice Welbourn. 1994. “Extending the Horizons of Agricultural Research and Extension: Methodological Challenges.” Agriculture and Human Values 11: 38–57.

- Datey, Abhijit, Bhawna Bali, Neha Bhatia, Leishipem Khamrang, and Sohee Minsun Kim. 2023. “A Gendered Lens for Building Climate Resilience: Narratives from Women in Informal Work in Leh, Ladakh.” Gender, Work & Organization 30(1): 158–76.

- Deere, Carmen Diana. 2017. “Women’s Land Rights, Rural Social Movements, and the State in the 21st-Century Latin American Agrarian Reforms.” Journal of Agrarian Change 17(2): 258–78.

- Deere, Carmen Diana and Magdalena León. 2003. “The Gender Asset Gap: Land in Latin America.” World Development 31(6): 925–47.

- Diarra, Fatimata Bintou, Mathieu Ouédraogo, Robert B. Zougmoré, Samuel Tetteh Partey, Prosper Houessionon, and Amos Mensah. 2021. “Are Perception and Adaptation to Climate Variability and Change of Cowpea Growers in Mali Gender Differentiated?” Environment, Development and Sustainability 23(9): 13854–70.

- Djoudi, Houria and Maria Brockhaus. 2011. “Is Adaptation to Climate Change Gender Neutral? Lessons from Communities Dependent on Livestock and Forests in Northern Mali.” International Forestry Review 13(2): 123–35.

- Doss, Cheryl, Ruth Meinzen-Dick, and Allan Bomuhangi. 2014. “Who Owns the Land? Perspectives from Rural Ugandans and Implications for Large-Scale Land Acquisitions.” Feminist Economics 20(1): 76–100.

- Dupuis, Sarah, Monique Hennink, Amanda S. Wendt, Jillian L. Waid, Md Abul Kalam, Sabine Gabrysch, and Sheela S. Sinharoy. 2022. “Women’s Empowerment Through Homestead Food Production in Rural Bangladesh.” BMC Public Health 22(1): 1–11.

- Enarson, Elaine Pitt. 2012. Women Confronting Natural Disaster: From Vulnerability to Resilience. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Enfors, Elin I. and Line J. Gordon. 2008. “Dealing with Drought: The Challenge of Using Water System Technologies to Break Dryland Poverty Traps.” Global Environmental Change 18(4): 607–16.

- Essilfie, Gloria, Joshua Sebu, and Samuel Kobina Annim. 2020. “Women’s Empowerment and Child Health Outcomes in Ghana.” African Development Review 32(2): 200–15.