?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

People’s perception of their own efficacy is a critical precursor for adaptive behavioural responses to the threat posed by climate change. The present study investigated whether components of climate efficacy could be enhanced by short video messages. An online study (N = 161) compared groups of participants who received messages focusing on individual or collective behaviour. Relative to a control group, these groups showed increased levels of response efficacy but not self-efficacy. However, this did not translate to increased climate commitment; mediation analysis suggested that the video messages, while increasing efficacy, may also have had a counterproductive effect on behavioural intentions, possibly by reducing the perceived urgency of action. This finding reinforces the challenge faced by climate communicators seeking to craft a message that boosts efficacy and simultaneously motivates adaptive responses to the climate crisis.

Introduction

As the effects of climate change mount and future risks loom large, the question of how best to engage the public is vital. In the absence of clear ways to control the external threat of climate change, individuals may respond by attempting to control internal emotions, by avoiding the topic, denying the evidence or choosing apathy (e.g., Moser & Dilling, Citation2004). Concerns about the potential counterproductive effect of fear appeals have prompted researchers to argue that threatening climate information should be accompanied by information that seeks to boost climate efficacy, i.e., the sense that there is something that people can do to tackle the threat of climate change (e.g., Hart & Feldman, Citation2014). This emphasis on both “urgency and agency” (e.g., Mann, Citation2021) is consistent with a wealth of evidence from social, clinical and health psychology. Indeed, a sense of efficacy—the belief that a behavioural response to a given obstacle is feasible and will be effective in overcoming it—is a fundamental precursor to any adaptive behaviour (Bandura, Citation1982).

Climate efficacy

The dual importance of (perceived) threat and efficacy is a common aspect of many psychological theories (e.g., Protection Motivation Theory, Rogers, Citation1975; the Extended Parallel Process Model, Witte, Citation1992; the cognitive theory of stress, Folkman & Lazarus, Citation1988; the integrative model, Fishbein & Yzer, Citation2003). For example, according to Protection Motivation Theory, intentions to protect oneself against a threat depend on one’s appraisal of the threat and one’s coping capacity—the degree to which one feels able to reduce that threat. Threat appraisal is a function of both the perceived severity of the threat and its perceived probability (or one’s vulnerability to the threat). Many studies have reported an association between people’s perceptions of the threat associated with climate change and their intention to engage in pro-environmental behaviours (e.g., Bockarjova & Steg, Citation2014; Grothmann & Patt, Citation2005; Rainear & Christensen, Citation2017; Spence et al., Citation2011; Zhao et al., Citation2016).

Coping appraisal can be decomposed into self-efficacy (i.e., the perception of one’s ability to perform preventative behaviours) and response efficacy (i.e., the perceived efficacy of those behaviours to reduce the threat). Studies have reported positive associations between perceived efficacy and climate behaviour. For example, van Vugt and Samuelson (Citation1999) found that people’s efforts to conserve water during an extreme weather event depended on the extent to which they felt that their own contribution made a difference. Indeed, Heath and Gifford (Citation2006) found that efficacy was the best predictor of behavioural intentions to mitigate effects of climate change (r = 0.65). Such results support the idea that climate change messages should combine both threat information and efficacy-enhancing information. Questions remain, however, including: (a) Is it possible to enhance people’s climate efficacy? (and if so, how?), (b) How do different types of climate efficacy relate to different types of climate behaviour?, and hence, (c) What type of efficacy should communicators seek to enhance? We explore these questions in the present article.

Different types of climate efficacy

Studies examining the relationship between efficacy and climate behaviour have often relied on measures that conflate self-efficacy and response efficacy (Bostrom et al., Citation2019). For example, items such as “There are simple things that I can do that will have a meaningful effect to alleviate the negative effects of global warming” (Heath & Gifford, Citation2006) incorporate aspects of both self-efficacy (“simple things that I can do”) and response efficacy (“that will have a meaningful effect”). A further important distinction is between individual efficacy (i.e., the belief that I personally can take meaningful action) and collective efficacy (the belief that collective effort is possible and will be successful). Climate change is clearly a collective problem, and several studies have identified the importance of collective efficacy for predicting pro-environmental behaviour (e.g., Chen, Citation2015; Homburg & Stolberg, Citation2006; Pakmehr et al., Citation2020).

Can climate efficacy be boosted?

Given the association between efficacy and climate behaviour, it is natural to ask what climate communicators can do to enhance climate efficacy. Not many published studies have specifically addressed this question, and those that have offer relatively little encouragement. Indeed, Hornsey et al. (Citation2021a) speculated that the paucity of efficacy interventions reported in the literature may reflect a file-drawer problem.

A systematic investigation of the use of messaging to influence perceived climate efficacy was reported by Hart and Feldman (Citation2016a). They tested seven conditions: a no-message control and positive and negative messages focused on three different types of efficacy. Participants in the treatment conditions read a news article that described an individual’s ability to take political action (internal efficacy), the US government’s responsiveness to public calls for action on climate change (external efficacy), or the potential for government policies to reduce the threat of climate change (response efficacy). Exposure to the positive articles resulted in greater pro-environmental political intentions relative to the other articles. However, this influence was not mediated by changes in levels of efficacy. Of the 18 pairwise comparisons to the no-message control, only two were statistically significant. One of these two effects was a reduction in external efficacy, relative to the no-message control (this reduction was a response to a negative efficacy message, rather than a “backfire” effect). The other effect was a small positive impact of the positive internal efficacy message on the corresponding component of efficacy. Some caution is appropriate when interpreting this significant result, given the potential for Type-I errors.

Another relevant study was reported by Jugert et al. (Citation2016), who compared high and low collective efficacy conditions. In the high efficacy condition participants read a text describing how young people were working together to create initiatives to promote low-carbon transport, which was having a positive impact on the use of electric vehicles in Germany; the low efficacy condition was similar, but stated that these initiatives had not increased the use of electric vehicles. The results showed higher levels of collective and self efficacy in the high efficacy condition. In the absence of a control condition, though, it is not clear whether the difference between conditions reflects a positive impact of the high-efficacy message or a negative impact of the low-efficacy message (as in Hart & Feldman, Citation2016a), or both.

Hornsey et al. (Citation2021b) attempted to increase people’s climate efficacy using a video that described how individual actions can lead to larger changes in interconnected systems. An initial experiment found that participants who saw this video had higher levels of individual efficacy than participants who watched a control video. However, in a large-scale replication attempt Hornsey et al. found no effect of the efficacy video relative to the control video. They suggested that the difference between the experiments could reflect the presence of demand characteristics in the first experiment.

A study that succeeded in increasing individuals’ perceived efficacy was reported by Hart and Feldman (Citation2016b). Participants were shown a short article that included information about the impacts of climate change and/or actions that can be taken to reduce those impacts. The article was paired with one of four images (a solar panel, a flood, a protest march, or smoke from a power plant), or no image. Participants then rated how much they agreed with the statement: “The article I read made me feel that I can do something about climate change.” Participants who saw the image of a solar panel showed higher agreement with this statement than participants who saw other images, as well as showing greater intentions to engage in pro-environmental behaviour (there were no effects of the other images relative to the no image control group). This finding suggests that imagery that depicts solutions for reducing emissions could boost efficacy.

Another study that succeeded in increasing individuals’ perceived efficacy was reported by Bieniek-Tobasco et al. (Citation2020). They found that participants who watched an episode of a climate change documentary series (Years of Living Dangerously) had higher levels of efficacy than they did prior to watching the episode. The same increase in efficacy was not observed among participants who watched a control video. Although this within-subjects design has some advantages, the repeated measurement of efficacy on either side of the intervention raises the possibility of demand characteristics. Furthermore, the numerical post-treatment differences between groups were small (the authors did not report between-subjects tests).

In summary, though some studies suggest it may be possible to increase individuals’ climate efficacy, there are at least as many attempts to boost efficacy that have been unsuccessful. In addition, the available evidence does not allow us to determine which aspects of efficacy might be most amenable to intervention. The present study aimed to explore these questions further.

Is efficacy a response to threat?

Studies of attitudes toward climate change have repeatedly found that threat and efficacy are positively correlated (e.g., Brody et al., Citation2008; Heath & Gifford, Citation2006; Hornsey et al., Citation2015; Kellstedt et al., Citation2008; Milfont, Citation2012). Hornsey et al. (Citation2015) suggested that higher levels of efficacy are a direct response to climate concern: faced with a perceived threat that could engender feelings of helplessness, individuals are motivated to mitigate this threat by increasing their perception of the degree of control they exert over the situation. Hornsey et al. (Citation2015) tested this hypothesis in an experiment in which they gave participants either low- or high-threat climate messages and then measured perceived risk, individual efficacy and collective efficacy. Results showed that the high threat group had higher levels of collective efficacy than the low threat group (individual efficacy did not differ). Further analysis indicated that this effect was mediated via increased perceived risk in the high threat group, as would be predicted by the motivated control hypothesis. This successful manipulation of participants’ efficacy is all the more impressive given the mixed findings of those studies that have made more direct attempts to boost climate efficacy. It also raises the possibility that the increased efficacy that Bieniek-Tobasco et al. (Citation2020) found for participants who watched an episode of Years of Living Dangerously could reflect the influence of content that focused on the impacts of climate change rather than potential solutions.

The present study

The goal of the present study was to examine climate efficacy: its components, whether (and how) these components can be enhanced, and how they relate to different forms of climate commitment.Footnote1 To this end, we compared two different approaches to increasing climate efficacy, one targeting individual efficacy and the other focused on collective efficacy; both approaches were compared with a control condition with no efficacy information. We examined the effect of these interventions on different components of climate commitment, including both public sphere and private sphere actions. We also measured climate concern, to seek to replicate the previously established positive correlation between concern and efficacy. To briefly foreshadow our findings, the results suggest that some aspects of climate efficacy are malleable, but that this will not necessarily translate to an influence on behavioural intentions.

Materials and methods

Participants

The study received ethical approval from the University of Bristol School of Psychological Science Ethics Committee (Ethics Approval Code 109022). Participation was voluntary, we obtained consent and the confidentiality of answers was guaranteed. The sample size was constrained by available funds but was sufficient to give more than 80% power to detect a medium effect size (d = 0.5). A putative effect of this magnitude provided a reasonable threshold for detecting an effect that is present not only in idealised conditions but which may also have utility as a real-world intervention (we return to this issue in the General Discussion).

All participants were adults who were current residents of the UK and spoke English either as a first language or as fluent non-native speakers. Of these, 145 participants were recruited via Prolific and a further 22 were recruited via convenience sampling. One participant was removed due to inconsistent responses and an incorrect answer to an attention check that followed the threat video. A further five participants were excluded on the basis of a Mahalanobis Distance Test for multivariate outliers (Meade & Craig, Citation2012). The final sample included 90 female and 71 male participants. The age distribution was as follows: 18–29 (46% of participants); 30–39 (28.6%); 40–49 (11.2%); 50–59 (9.9%); 60–69 (3.7%); 70–79 (0.6%).

Stimuli and design

The independent variable was Message Type, with three levels: (a) individual efficacy (threat communication followed by information on individual solutions); (b) collective efficacy (threat communication followed by information on collective solutions) and (c) no-efficacy (threat communication only; this condition functioned as a control against which to evaluate the other conditions). Participants were randomly assigned to one of these conditions in a between-subjects design.

The messages were delivered via videos that were approximately 2.5 minutes in duration. The videos were created with Microsoft PowerPoint and consisted of still images and audio. Content was collated from online sources, news articles and opinion pieces. The threat video summarised the risks of climate change, its effects to date and predicted future impacts.

The efficacy videos described three types of climate-related behaviours: using sustainable transport, reducing meat consumption and political participation. The script for the individual efficacy video highlighted stories and outcome expectancy of individual action, while the collective efficacy video highlighted the effectiveness of collective action. The two efficacy presentations used the same core images and script. Where appropriate, the individual efficacy video incorporated stories and photographs of specific individuals, where the collective efficacy video used equivalent stories of collective action alongside images of groups. An effort was made to ensure that both feasibility (self-efficacy) and effectiveness (response efficacy) were emphasized, through stories of past or projected success (see supplementary material for further details and links to the videos).

Procedure

We used Gorilla Experiment Builder (www.gorilla.sc) to create and host the experiment (Anwyl-Irvine et al., Citation2020). Data were collected between 14th and 28th August 2020.

After giving their informed consent, age and gender, participants were asked the four questions that make up the Six Americas Super Short SurveY (SASSY; Chryst et al., Citation2018): (a) How important is the issue of climate change to you personally?; (b) How worried are you about climate change?; (c) How much do you think climate change will harm you personally?; (d) How much do you think climate change will harm future generations? Each item was rated on a 5-point scale, other than the Worry item, which was rated on a 4-point scale (from “Not all worried” to “Very Worried”). Responses were averaged to produce a total score for concern (Cronbach’s α = 0.85, M = 3.75, SD = 0.70).

All participants then watched a short video on the threats posed by climate change. Participants in the efficacy conditions then watched a short video designed to enhance climate efficacy (as described above). After each of the videos participants responded to a simple attention check question about the video content. After the threat video, participants were asked what element of the video, if any, they found most concerning. After the efficacy video, they were asked to share one or two ideas of actions that they could personally take (individual efficacy condition) or that governments, communities, and groups could take (collective efficacy condition). The objective was to encourage deeper engagement with the video content and to identify participants for exclusion.

After watching the videos, participants went on to the questionnaire, which included items measuring perceived efficacy and climate commitment. These scales are described below; the full set of items can be found in the supplementary material.

Post-manipulation measures

Perceived efficacy

The efficacy measures were derived from Bostrom et al. (Citation2019), with a few modifications. Most of these amendments were as per Bostrom et al.’s recommendations (e.g., geoengineering and population/family planning items were removed). In addition, we added some references to behaviours that were referred to in the videos (for example, choosing a climate-friendly diet) but not mentioned in the original scale. The analyses we present below collapse the individual and collective efficacy subscales; this increases the reliability of the resulting scales (largely because there were only three items in each of the individual efficacy subscales) and simplifies the presentation but does not qualitatively affect the results.

Self-efficacy

The self-efficacy items included items measuring both individual and collective self-efficacy. The former items asked participants how easy different actions would be for them to do, personally (e.g., “Significantly reduce your air travel”). The collective efficacy items asked how easy it would be for governments/communities/groups to perform different actions, e.g., (“How easy would it be for everyone in the UK to collectively change their behaviour (e.g., cut down flying; use public transport; reduce meat-consumption; cut household energy).”

Ratings were made on a scale from 1 = extremely difficult to 7 = extremely easy. Assessment of the reliability of the individual self-efficacy items showed a relatively low Cronbach’s α of 0.57. Combining all self-efficacy items together increased the reliability of the scale (Cronbach’s α = 068).

Response efficacy

The response efficacy items consisted of a set of statements describing the efficacy of three actions that the participant might personally take (e.g., “If I make climate-friendly changes to my lifestyle, it will reduce the threat of climate change”) and five actions that the government might take (e.g., “If the government and local councils enforce climate change policies and implement climate-friendly initiatives, it would reduce the threat of climate change”). For each statement, participants rated their agreement on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree); we subsequently rescaled scores to be on a scale of 1 to 7 so as to facilitate comparison and integration with the other scales. Combining all eight items resulted in a scale with good reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.87).

Climate commitment

This construct was measured as the average of four subscales: mitigation motivation, willingness to sacrifice, and two behavioural intention measures (one that focused on personal and household behaviours, and one that was about participatory and activist behaviours). Responses on these four subscales were highly correlated; the lowest correlation (between Mitigation Motivation and Personal pro-environmental behaviours) was 0.68, with other correlations between .69 and .76. Each of the subscales had high internal consistency, as detailed in the following.

Mitigation motivation

Mitigation motivation was measured as in Hornsey and Fielding (Citation2016) by asking participants, “How did the videos make you feel?,” followed by two statements (“I feel energised to do more to respond to climate change” and “I feel a sense of urgency to act in climate-friendly ways”) to which participants responded on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 6 (Extremely). The responses to these two items were averaged to produce a single score, which was then rescaled to be on a scale of 1 to 7 (Cronbach’s α = 0.92, M = 4.96, SD = 1.51).

Willingness to sacrifice

Willingness to sacrifice was measured using the scale developed by Davis et al. (Citation2011), with slight amendments such that the scale referred to climate change (rather than the environment) and reflected economic sacrifice as in Bilandzic et al. (Citation2017). Participants were asked to what extent they agreed with nine statements (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree), including: “Higher prices for climate-friendly energy are acceptable” and “Even when it is inconvenient to me, I am willing to do what I think is best for the climate and environment.” The responses were averaged to give a single score (Cronbach’s α = 0.93, M = 4.95, SD = 1.19).

Personal pro-environmental behaviours

Personal pro-environmental behaviours relate to household, lifestyle, and consumer behaviour. Participants were asked to rate how likely they were to engage in a list of behaviours (1 = Very unlikely, 7 = Definitely). The list consisted of thirteen behaviours drawn from the General Ecological Behaviour measure (Kaiser & Wilson, Citation2004). In the interests of brevity and relevance we selected the behaviours with the greatest objective impact on carbon emissions (Truelove & Parks, Citation2012; Wynes et al., Citation2018). Two items were reverse coded; responses were averaged to produce a single score (Cronbach’s α = 0.78, M = 4.70, SD = 0.96).

Collective pro-environmental behaviours

Collective pro-environmental behaviours relate to proactive engagement through participatory or activist behaviour. The Environmental Action scale of Alisat and Riemer (Citation2015) was amended to derive 18 items specific to climate change. Example behaviours include: teaching oneself and others about the issue, engaging in conservation projects or political campaigning. For each behaviour participants were asked “How likely are you to do (or continue doing) the following things in the future?” on a scale from 1 (Very unlikely) to 7 (Definitely). Responses to these items were averaged to produce a single score (Cronbach’s α = 0.95, M = 3.99, SD = 1.40).

Results

Associations between concern, efficacy and commitment

shows correlations between climate concern, efficacy and commitment. Scores on the two efficacy scales were moderately positively correlated (r = .51), suggesting that these scales were effective in tapping into different aspects of efficacy. In keeping with previous findings (and consistent with theoretical frameworks such as protection motivation theory), climate concern was positively correlated with both self-efficacy and response efficacy. All three variables were highly correlated with climate commitment.Footnote2

Table 1. Means, standard deviations and correlation matrix for climate concern, efficacy and commitment.

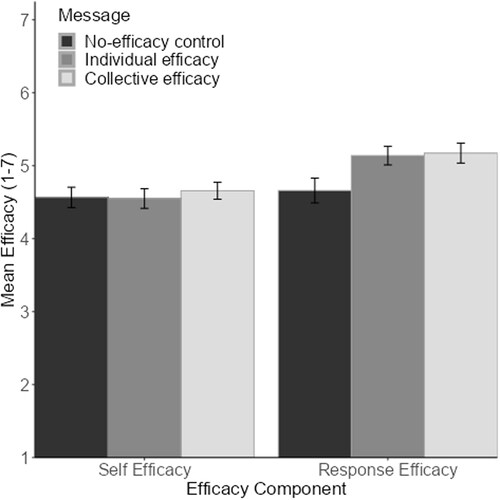

The effect of messaging on perceived efficacy

shows the effect of message condition on self-efficacy and response efficacy. As can be seen, the efficacy messages resulted in higher levels of response efficacy, relative to the control condition, but did not affect levels of self-efficacy. This was confirmed by ANCOVAs (controlling for prior levels of climate concern) which showed significant effects of message condition on response efficacy,

but not on self-efficacy,

Footnote3 One-tailed t-tests were conducted to test differences in response efficacy for both of the efficacy messages against the no-efficacy control (after Bonferroni-adjustment, the critical alpha level for these tests was .025). These tests showed that response efficacy was significantly higher for participants in the individual efficacy condition compared to those in the no-efficacy condition,

95% CI

and also significantly higher for participants in the collective efficacy condition compared to those in the no-efficacy condition,

95% CI

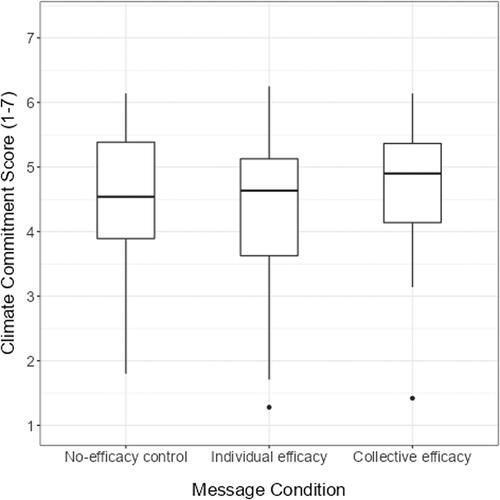

The effect of messaging on climate commitment

The regression analysis described in Sec. 3.1 shows that efficacy is a strong predictor of climate commitment and the ANCOVAs presented in Sec. 3.2 shows that our efficacy messages resulted in significantly higher scores on response efficacy, relative to the control group. Putting these two observations together might lead one to expect that the efficacy messages would significantly boost climate commitment. However, this expectation is not what we observed, as can be seen in , which shows the effect of message condition on climate commitment; in particular, the boxplot suggests that the collective efficacy message produced a slight negative shift in the distribution of climate commitment scores. An ANCOVA showed no effect of message condition on climate commitment after controlling for the effect of concern (F < 1).

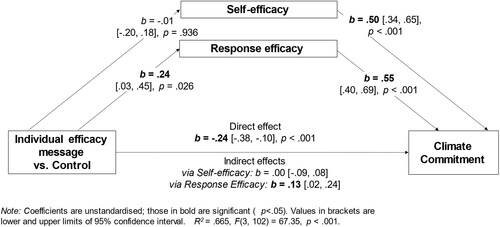

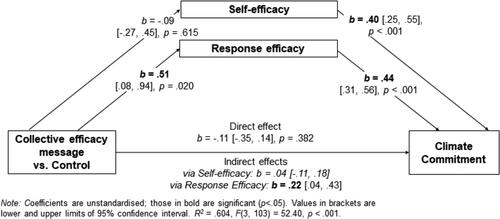

The significant effect of our messages on response efficacy and the effect of efficacy on climate commitment led us to speculate that there would be a positive indirect effect of efficacy messaging on climate commitment, and that this positive effect was masked by a negative direct effect of efficacy messaging (i.e., a suppressor effect, e.g., MacKinnon et al., Citation2000).Footnote4 To test this account we conducted mediation analyses, using Hayes’ (Citation2017) PROCESS package for R. We constructed the models shown in and , in which message condition transmits an effect on climate commitment both directly and indirectly through the mediators self-efficacy and response efficacy, and used bootstrapping with 5000 samples to construct 95% confidence intervals on the direct and indirect effects.

As can be seen in , the individual efficacy message resulted in significantly higher values of response efficacy (relative to the control condition) and higher levels of response efficacy were associated with significantly higher values of climate commitment; the resulting indirect effect of message on commitment was statistically significant in the bootstrapping analysis.Footnote5 There was no corresponding indirect effect via self-efficacy; although higher levels of self-efficacy were associated with significantly higher values of climate commitment, the individual efficacy message did not increase levels of self-efficacy (relative to the control group). Despite the positive indirect effect via response efficacy, the net effect of the individual efficacy message on climate commitment was (numerically) negative, due to a significant negative direct effect.

The pattern of results for the collective efficacy message was quite similar (see ). Here the indirect effect of the efficacy message on climate commitment was if anything slightly more pronounced. There was no indirect effect via self-efficacy, due to the very weak effect of the message on this form of efficacy. The direct effect of the collective efficacy message on climate commitment had a negative coefficient, but the test of this effect was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our study contributes to an ongoing debate about the relative importance of increasing risk perception and arousing fear versus promoting a sense of efficacy by sharing stories of solutions to effectively inspire action (Baden, Citation2019; Feinberg & Willer, Citation2011; Hornsey & Fielding, Citation2016; Kundzewicz et al., Citation2020; van Zomeren et al., Citation2019). We structure the discussion of our results to consider (a) implications for interventions to boost efficacy, (b) the direct and indirect effects of climate communication messages and (c) the association between efficacy and concern.

Implications for interventions to boost efficacy

Our efficacy interventions showed a mixture of significant and nonsignificant effects, and our findings may contribute to understanding the mixed results that have been observed in previous attempts to increase climate efficacy (e.g., Hart & Feldman, Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Hornsey et al., Citation2021a; Jugert et al., Citation2016). In particular, our results suggest some components of efficacy are more amenable to enhancement than others.

We observed no effect of our efficacy messages on participants’ self-efficacy. This may indicate that self-efficacy is resistant to one-off communications. Bandura (Citation1982) argues that the creation of self-efficacy is an inferential process, and that the most influential source of efficacy information is the feedback from “enactive mastery” experiences, which provide direct experience of one’s own capability to deal with a threat. Effective interventions to increase climate self-efficacy may require multiple sessions and an experiential component rather than simple one-shot messages. Indeed, this may go some way to explaining the paucity of published studies that have reported successful attempts to boost climate efficacy (particularly if studies have assessed efficacy using measures that involve an element of self-efficacy).

However, an alternative interpretation of the difficulty involved in boosting self-efficacy is that it reflects baseline aspects of people’s climate beliefs. Most people probably already know what sorts of climate mitigation behaviours they could undertake, and have a good sense of their own capacity to make the necessary behavioural changes, and there may have been little in our videos that was likely to affect people’s beliefs in this regard. Lower levels of response efficacy may reflect people’s perception that there is not much that they can do personally that will have an impact on climate change. One consequence, though, is that this may be the component that has the most scope to be enhanced.

Our results showed that both videos led to a robust increase in response efficacy relative to the control group. Bandura (Citation1982) suggests that response efficacy takes priority in appraisals, because an individual must first decide if an action will be effective in minimizing the threat. Thus, evidence that response efficacy is amenable to manipulation is a valuable finding which may be important for climate communication.

The question remains as to why our manipulation of response efficacy succeeded where other attempts did not. There may be several factors at work. Our video stimuli (including the personal stories and images of faces) may have provided a more persuasive message than previous studies that have relied on written texts. Hornsey et al. (Citation2021a) argue that climate change efficacy depends on non-analytic processes, which may be more responsive to imagery than words and numbers. Similarly, Bieniek-Tobasco et al. (Citation2020) found that watched a climate change documentary had a positive impact on efficacy beliefs, and that this was especially true for those who reported feeling “transported by” the narrative. External factors may also have contributed to our manipulation being more successful than that of older studies. In the period immediately preceding our experiment the youth-led climate campaign initiated by Greta Thunberg led to the largest climate change protest ever, and the activist group Extinction Rebellion attracted considerable public attention in the UK and elsewhere for its mass civil disobedience actions. Awareness of these actions and the responses of politicians (e.g., the UK parliament declared a climate emergency in May 2019) may have made our participants more responsive to efficacy messages. Finally, a third factor contributing to the success of our efficacy manipulation may have been the inclusion of a reflection task following the efficacy video. Self-reflection plays an important role in social cognitive theory. Bandura (Citation2001, p. 10) notes that, “people are not only agents of action but self-examiners of their own functioning. The metacognitive capability to reflect upon oneself, one’s sense of individual efficacy, and the adequacy of one’s thoughts and actions is [a core] feature of human agency.” Thinking about the impact of one’s own personal actions may be effective in heightening individual response efficacy.

Direct and indirect effects of climate communication messages

Given the significant associations between efficacy and climate commitment it might have been expected that increasing efficacy would have a positive impact on behavioural intentions. Indeed, such a prediction may seem virtually axiomatic from theoretical perspectives such as protection motivation theory. However, although we were able to boost a key aspect of climate efficacy, this did not translate to a significant influence on climate commitment.

At one level, it should not be surprising that our intervention did not influence participants’ behavioural intentions. Behaviour is hard to change, and climate behaviour is no exception. A recent meta-analysis of climate change attitude interventions has confirmed that these interventions are less effective at influencing policy attitudes than beliefs (Rode et al., Citation2021). However, it would be wrong to dismiss the results of our interventions as just another null effect. The mediation analyses suggest that the null effect of the individual efficacy message reflects the net impact of significant direct and indirect effects. On the one hand, participants who received a climate efficacy message did show increased response efficacy, relative to the control group, and this boost in efficacy resulted in indirect positive effects on climate commitment. On the other hand, the direct effect of the efficacy message was negative (although the direct effect was only statistically significant for the individual efficacy message).

The question raised by these findings is why a climate efficacy message should exert a negative direct effect on behavioural intentions. We speculate that this effect is consistent with the “complacency model” described by Hornsey and Fielding (Citation2016). According to this model, optimistic messages tend to reduce the perceived risk and distress produced by thinking about climate change, and this in turn reduces mitigation motivation and related aspects of climate commitment. The efficacy messages we presented to participants were essentially optimistic, suggesting that personal and/or collective action can succeed in addressing the threat of climate change. However, this optimism may be counterproductive—if the problem can be addressed it is not so threatening, and hence taking action is not so urgent. Our data offer only indirect evidence for this complacency model, as we did not measure perceived risk or distress subsequent to our efficacy message. In passing, we note that this account may also explain a striking finding from the meta-analysis by Rode et al. (Citation2021) cited above, which is that negative interventions—those that seek to reduce belief in climate change—are associated with much larger effect sizes than positive interventions. People may be attracted to information that makes climate change seem less of an urgent problem, whether that information entails reassurance that the problem can be tackled or a downplaying of the problem itself.

A related possibility is that hearing stories of others taking action may encourage a kind of freeloading response in some participants. Future research should seek to replicate the direct effect of the climate efficacy message we observed here and explore whether it is mediated by a reduction in perceived risk. Confirmation of the putative effect would pose a problem for climate communicators, who seek to communicate both the possibility of taking action to mitigate against climate change and the urgency of such action.

Exploring the association between concern and efficacy

Our data showed a strong positive association between climate concern and efficacy (see ); indeed, concern explained over a third of the variance in total efficacy. This positive correlation replicates previous research (e.g., Hornsey et al., Citation2015). However, our exploration of the different components of efficacy allows us to investigate the association between climate concern and efficacy in more detail. Climate concern was much more strongly associated with response efficacy than self-efficacy. This result seems consistent with Hornsey et al.’s motivated control hypothesis, given that the items measuring response efficacy explicitly referenced the outcome of reducing threat (e.g., “If the government did [X] it would reduce the threat of climate change”); items like these might be expected to tap into a desire for control driven by the motivation to reduce threat. Nevertheless, we acknowledge this account is speculative and relies on correlational evidence.

Probing the components of climate concern in our data also offers support for another mechanism that could contribute to the positive association of climate concern and efficacy. The strong association (r = .58) we observed between response efficacy and the personal importance component of the SASSY is consistent with an account that explains the concern-efficacy association with reference to a third variable—adherence to a normative script that is common to those with a pro-environmental orientation (what Hornsey et al., Citation2015 refers to as “green identity”). People who adhere to this identity will tend to share high levels of climate concern, as well as the belief that action can be taken to address the climate crisis. Once again, though, the associational nature of the evidence prevents us from drawing strong conclusions about this putative mechanism.

Limitations

There are some limitations of our study. Our sample size meant that we had good power to detect a medium-sized effect (d = 0.5), and indeed, we detected effects that were close to this magnitude. Nevertheless, the nonsignificant effect of the collective efficacy message on self-efficacy could potentially represent a Type-II error. At the same time, there are some aspects of the experimental manipulation that may exaggerate the size of the effect that would be observed in a real-world intervention. Thus, the pattern of significance obtained in our results should not be taken as evidence that climate self-efficacy cannot be boosted by messaging interventions, but rather as a further indicator of the practical difficulties faced by such interventions (cf. Rode et al., Citation2021).

A similar concern applies to the nonsignificant direct effect of the collective efficacy message on climate commitment, which may reflect a Type-II error, i.e., the pattern for the collective efficacy message may be identical to that for the individual efficacy message. Moreover, if the difference between the two messages is genuine, we are limited in our ability to isolate the exact component(s) responsible for the different effects. In developing the videos we felt it was important to vary the content to ensure the experimental manipulation clearly distinguished the two conditions. Although the two videos followed the same structure, there were a number of differences between the individual and collective efficacy messages with respect to the words and images used; for example, the individual efficacy video included more pictures of individual’s faces. Future research is necessary to determine whether the two messages do have clearly different effects on climate commitment, and if so, which are the critical component(s) underlying this difference.

Conclusions

In summary, our results suggest that belief in the possibility of limiting climate change is more easily changeable than beliefs in the feasibility of the actions themselves. Climate communications that focus on the threats of climate change and on individual action stories may have the potential to increase perceptions of individual and collective response efficacy. However, stories of individual efficacy may also decrease commitment to tackling climate change, thus cancelling out the positive influence of efficacy on intentions. Although our findings offer support to theoretical frameworks that highlight the dual role of concern and efficacy, it does not follow that interventions that boost efficacy will necessarily promote greater behavioural intentions. Future work is needed to explore how to boost individuals’ self-efficacy to engage in climate-related behaviour, and how to increase efficacy without undermining the urgency of taking action.

Supplementary_Materials_3_-_Factor_analysis.docx

Download MS Word (19.9 KB)Supplementary_Materials_2_-_Scales.docx

Download MS Word (20.6 KB)Supplementary_Materials_1_-_Video_details_and_links.docx

Download MS Word (18.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 We use the term climate commitment to refer to a broad range of behaviours in the public and private spheres that are motivated by a desire to reduce the impacts of climate change.

2 The independent contribution of concern and efficacy was established by a multiple regression in which climate commitment was regressed on concern and the two efficacy scales; R2 for the resulting model was 0.69, and tests on each of the predictors were significant [concern, t(157) = 7.03, p <. 001; self-efficacy: t(157) = 6.95, p <. 001], or marginally significant [response-efficacy: t(157) = 4.16, p =. 051]

3 In view of the relationship between climate concern and efficacy (see Section 3.1) we thought that it would be appropriate to control for the former variable when testing the impact of the efficacy messages. However, the pattern of results was identical in an ANOVA which did not control for Concern. We also obtained the same pattern of results when we did not collapse individual and collective self-efficacy, i.e., there were significant effects of message condition on both individual and collective response efficacy but on neither individual nor collective self-efficacy.

4 If the direct and indirect effects of X on Y differ in sign, the total effect may be close to zero. Thus, it is now generally accepted that tests of an indirect effect of X on Y should not be conditional on evidence of a total effect of X on Y (e.g., Hayes, Citation2017, chapter 4).

5 We obtained a similar pattern of results in models in which the combined response efficacy mediator was replaced by either individual or collective response efficacy.

References

- Alisat, S., & Riemer, M. (2015). The environmental action scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 43, 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.05.006

- Anwyl-Irvine, A. L., Massonnié, J., Flitton, A., Kirkham, N., & Evershed, J. K. (2020). Gorilla in our midst: An online behavioral experiment builder. Behavior Research Methods, 52(1), 388–407. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01237-x

- Baden, D. (2019). Solution-focused stories are more effective than catastrophic stories in motivating proenvironmental intentions. Ecopsychology, 11(4), 254–263. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2019.0023

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

- Bieniek-Tobasco, A., Rimal, R. N., McCormick, S., & Harrington, C. B. (2020). The power of being transported: Efficacy beliefs, risk perceptions, and political affiliation in the context of climate change. Science Communication, 42(6), 776–802. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547020951794

- Bilandzic, H., Kalch, A., & Soentgen, J. (2017). Effects of goal framing and emotions on perceived threat and willingness to sacrifice for climate change. Science Communication, 39(4), 466–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547017718553

- Bockarjova, M., & Steg, L. (2014). Can Protection Motivation Theory predict pro-environmental behavior? Explaining the adoption of electric vehicles in the Netherlands. Global Environmental Change, 28, 276–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.06.010

- Bostrom, A., Hayes, A. L., & Crosman, K. M. (2019). Efficacy, action, and support for reducing climate change risks. Risk Analysis, 39(4), 805–828. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13210

- Brody, S. D., Zahran, S., Grover, H., & Vedlitz, A. (2008). A spatial analysis of local climate change policy in the United States: Risk, stress, and opportunity. Landscape and Urban Planning, 87(1), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2008.04.003

- Chen, M.-F. (2015). Self-efficacy or collective efficacy within the cognitive theory of stress model: Which more effectively explains people’s self-reported proenvironmental behavior? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 42, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.02.002

- Chryst, B., Marlon, J., Linden, S., van der, Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., & Roser-Renouf, C. (2018). Global warming’s “Six Americas Short Survey”: Audience segmentation of climate change views using a four question instrument. Environmental Communication, 12(8), 1109–1122. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1508047

- Davis, J. L., Le, B., & Coy, A. E. (2011). Building a model of commitment to the natural environment to predict ecological behavior and willingness to sacrifice. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(3), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2011.01.004

- Feinberg, M., & Willer, R. (2011). Apocalypse soon? Dire messages reduce belief in global warming by contradicting just-world beliefs. Psychological Science, 22(1), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610391911

- Fishbein, M., & Yzer, M. C. (2003). Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Communication Theory, 13(2), 164–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00287.x

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). The relationship between coping and emotion: Implications for theory and research. Social Science & Medicine, 26(3), 309–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(88)90395-4

- Grothmann, T., & Patt, A. (2005). Adaptive capacity and human cognition: The process of individual adaptation to climate change. Global Environmental Change, 15(3), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.01.002

- Hart, P. S., & Feldman, L. (2014). Threat without efficacy? Climate change on U.S. network news. Science Communication, 36(3), 325–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547013520239

- Hart, P. S., & Feldman, L. (2016a). The influence of climate change efficacy messages and efficacy beliefs on intended political participation. PLOS One, 11(8), e0157658. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157658

- Hart, P. S., & Feldman, L. (2016b). The impact of climate change–related imagery and text on public opinion and behavior change. Science Communication, 38(4), 415–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547016655357

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Publications.

- Heath, Y., & Gifford, R. (2006). Free-market ideology and environmental degradation: The case of belief in global climate change. Environment and Behavior, 38(1), 48–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916505277998

- Homburg, A., & Stolberg, A. (2006). Explaining pro-environmental behavior with a cognitive theory of stress. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 26(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.03.003

- Hornsey, M. J., Chapman, C. M., & Oelrichs, D. M. (2021a). Why it is so hard to teach people they can make a difference: Climate change efficacy as a non-analytic form of reasoning. Thinking & Reasoning, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546783.2021.1893222

- Hornsey, M. J., Chapman, C. M., & Oelrichs, D. M. (2021b). Ripple effects: Can information about the collective impact of individual actions boost perceived efficacy about climate change? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 97, 104217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104217

- Hornsey, M. J., & Fielding, K. S. (2016). A cautionary note about messages of hope: Focusing on progress in reducing carbon emissions weakens mitigation motivation. Global Environmental Change, 39, 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.04.003

- Hornsey, M. J., Fielding, K. S., McStay, R., Reser, J. P., Bradley, G. L., & Greenaway, K. H. (2015). Evidence for motivated control: Understanding the paradoxical link between threat and efficacy beliefs about climate change. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 42, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.02.003

- Jugert, P., Greenaway, K. H., Barth, M., Büchner, R., Eisentraut, S., & Fritsche, I. (2016). Collective efficacy increases pro-environmental intentions through increasing self-efficacy. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 48, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.08.003

- Kaiser, F. G., & Wilson, M. (2004). Goal-directed conservation behavior: The specific composition of a general performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(7), 1531–1544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2003.06.003

- Kellstedt, P. M., Zahran, S., & Vedlitz, A. (2008). Personal efficacy, the information environment, and attitudes toward global warming and climate change in the United States. Risk Analysis, 28(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01010.x

- Kundzewicz, Z. W., Matczak, P., Otto, I. M., & Otto, P. E. (2020). From “atmosfear” to climate action. Environmental Science & Policy, 105, 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2019.12.012

- MacKinnon, D. P., Krull, J. L., & Lockwood, C. M. (2000). Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science, 1(4), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026595011371

- Mann, M. E. (2021). The New Climate War: the fight to take back our planet. Hachette UK.

- Meade, A. W., & Craig, S. B. (2012). Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 437–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028085

- Milfont, T. L. (2012). The interplay between knowledge, perceived efficacy, and concern about global warming and climate change: A one-year longitudinal study . Risk Analysis, 32(6), 1003–1020. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01800.x

- Moser, S. C., & Dilling, L. (2004). Making climate HOT. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 46(10), 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139150409605820

- Pakmehr, S., Yazdanpanah, M., & Baradaran, M. (2020). How collective efficacy makes a difference in responses to water shortage due to climate change in southwest Iran. Land Use Policy, 99, 104798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104798

- Rainear, A. M., & Christensen, J. L. (2017). Protection motivation theory as an explanatory framework for proenvironmental behavioral intentions. Communication Research Reports, 34(3), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2017.1286472

- Rode, J. B., Dent, A. L., Benedict, C. N., Brosnahan, D. B., Martinez, R. L., & Ditto, P. H. (2021). Influencing climate change attitudes in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 76, 101623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101623

- Rogers, R. W. (1975). A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. The Journal of Psychology, 91(1), 93–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803

- Spence, A., Poortinga, W., Butler, C., & Pidgeon, N. F. (2011). Perceptions of climate change and willingness to save energy related to flood experience. Nature Climate Change, 1(1), 46–49. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1059

- Truelove, H. B., & Parks, C. (2012). Perceptions of behaviors that cause and mitigate global warming and intentions to perform these behaviors. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32(3), 246–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.04.002

- van Vugt, M., & Samuelson, C. D. (1999). The impact of personal metering in the management of a natural resource crisis: A social dilemma analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(6), 735–750. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299025006008

- van Zomeren, M., Pauls, I. L., & Cohen-Chen, S. (2019). Is hope good for motivating collective action in the context of climate change? Differentiating hope’s emotion- and problem-focused coping functions. Global Environmental Change, 58, 101915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.04.003

- Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs, 59(4), 329–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759209376276

- Wynes, S., Nicholas, K. A., Zhao, J., & Donner, S. D. (2018). Measuring what works: Quantifying greenhouse gas emission reductions of behavioural interventions to reduce driving, meat consumption, and household energy use. Environmental Research Letters, 13(11), 113002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aae5d7

- Zhao, G., Cavusgil, E., & Zhao, Y. (2016). A protection motivation explanation of base-of-pyramid consumers’ environmental sustainability. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.12.003