ABSTRACT

Energy vulnerability is a multi-dimensional, dynamic and context-specific phenomenon that poses a challenge for equity in energy transition policies. The Capability Approach (CA) is a normative framework focused on people’s opportunities and freedoms, used to address dimensions of social justice. Whereas the CA has been used to assess and measure conditions of poverty, exclusion and inequality, its application to evaluate policies is rare. Building on work that establishes being able to heat the home adequately as a secondary capability towards being able to lead a healthy life, this narrative review maps the conditions and processes that shape this secondary capability in Victoria, Australia. It also evaluates local policies and initiatives aimed at addressing energy vulnerability. The map identifies structural, geographical and cultural phenomena and feed-back loops and exposes a hierarchy of capabilities for vulnerable households that need to be satisfied. The policy review finds that current efforts focus on mitigating inequalities in resources with little evidence for outcomes in security or transformative agency. Future initiatives may give more attention to the satisfaction of the tertiary capability of being able to live in an energy efficient dwelling, customise solutions to the multitude and range of conditions and acknowledge the need of warmth throughout the home.

© 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

Introduction

In the context of lower carbon energy transitions, there is a growing interest in addressing energy vulnerability and the broader legal, structural and socio-material conditions that shape energy poverty across the globe (Hall, Hards, and Bulkeley Citation2013; Recalde et al. Citation2019). Energy vulnerability provides an open definition of situations “in which a person or household is unable to achieve access to affordable and reliable energy services, and as a consequence is in danger of harm to health and/or well-being” (Day and Walker Citation2013, 16). It acknowledges local contingencies in these relationships which generate variations over space and time. In this paper we bring this understanding of energy vulnerability together with the Capabilities Approach (CA) (Sen Citation1979) to map conditions that produce energy vulnerability in Victoria, Australia. We focus on heating-related capabilities that matter for health and wellbeing to evaluate sets of policies and to make recommendations, but acknowledge that domestic energy services that are deemed essential extend beyond space heating (Simcock, Walker, and Day Citation2016).

The Capabilities Approach (CA) “is a broad normative framework for the evaluation and assessment of individual well-being and social arrangements, the design of policies, and proposals about social change in society” (Robeyns Citation2005, 93). Due to the flexibility of the concept (Robeyns Citation2017), the CA has already been used to develop theories of energy justice (Willand and Horne Citation2018; Bartiaux et al. Citation2018), to define energy poverty (Day, Walker, and Simcock Citation2016) and to measure energy poverty as an indicator of health inequality across nation states (Nussbaumer et al. Citation2011). However, its application to evaluate policies that aim to address energy vulnerability is limited. We suggest that analysing policies from the CA perspective deserves further investigation, as it allows for the consideration of structural and environmental conditions and systems of provision as mechanisms for reducing inequalities.

Focusing on the state of Victoria in Australia as our case study, we ask how policy tools influence the opportunities and contextual conditions of not being able to heat the home as an indicator of energy vulnerability. The term energy vulnerability acknowledges the multi-dimensionality of the causes and effects of energy deprivation (Day and Walker Citation2013; Bouzarovski, Petrova, and Tirado-Herrero Citation2014). The investigation is centred on warmth in the home as an outcome of adequate heating. This is because there is increasing evidence on the detrimental links between cold homes and poor health and wellbeing in Australia (Churchill, Smyth, and Farrell Citation2020; Daniel et al. Citation2019).

The state of Victoria is located in the south-east of the continent and is Australia’s second most populous state (ABS Citation2021b). About three out of four inhabitants live in Victoria’s capital Melbourne (ABS Citation2019). Two out three dwellings are owner occupied and seven out of ten households are families (ABS Citation2021a). Victoria has a heating dominated climate and a high prevalence of thermally inefficient housing stock (Sustainability Victoria Citation2015). With rapidly rising energy prices (Thwaites, Faulkner, and Mulder Citation2017), heating now accounts for a third of the energy costs in average Victorian households (Sustainability Victoria Citation2014). Consequently, community organisations have raised concerns about energy affordability and inequities in low carbon policies and programmes (ACOSS Citation2019).

The objective of this paper is to examine how analysing policies through the CA lens may provide new insights into tackling energy vulnerability. In the paper, we first provide a synthesis of the CA and its applications to energy vulnerability. Next, we use existing literature to map the varied components and tertiary capabilities that contribute to unequal heating opportunities in Victoria. We then examine, in which ways current Victorian policies and initiatives address these components and whether they meet CA related policy evaluation criteria. In the discussion section, we reflect further on the value of the CA for research in this area and propose alternative and complementary policy responses.

The Capability Approach (CA) and its key concepts

The CA was first developed by Amartya Sen as an alternative to the distributive principles and policy designs of welfarism and as a general tool to evaluate the quality of life across borders, cultures and time (Sen Citation1979; Robeyns Citation2006). The CA framework is anchored in five core elements: capabilities, functionings, resources, social conversion factors and choice (Robeyns Citation2017). While resources, capabilities and functionings are products or outcomes that may manifest levels of (dis)advantage, conversion factors and choice are mediating processes that influence these outcomes. They may also exhibit characteristics that lie at the root of inequalities.

A capability, at its most elementary and individual level, is “the freedom to achieve valuable human “functionings”” (Sen Citation1990, 460). Hence, capabilities are opportunities that allow people the autonomy to do or be things and to achieve quality of life (Robeyns Citation2005). A capability set is a bundle of functionings that a person can perform to achieve a good life. Functionings are valued “doings and beings”, i.e. the achievements or quality of life outcomes that are attained when the capabilities or capability sets are realised (Robeyns Citation2005). Core capabilities, such as being able to maintain good health, may require a variety of what have been termed secondary capabilities (Smith and Seward Citation2009), including, in some settings and times, being able to heat homes to adequate temperatures (Day, Walker, and Simcock Citation2016; Willand and Horne Citation2018).

Resources are material or measurable metrics such as income. Sen acknowledges that resources are one factor, but not the only one, that is needed for people to achieve valued functionings (Sen Citation1992). Conversion factors shape the processes of transforming resources into opportunities and capabilities into functionings (Robeyns Citation2017), and may be differentiated into personal, social and environmental conversion factors. Using the relevant example of disability, personal conversion factors refer to individual characteristics and personal competences, such as being limited in the ability to walk. Social conversion factors emerge from structural constraints, such as policies, social or cultural norms and legal rules, for example, when they focus on benefiting caregivers rather than providing more independence for people living with an impairment. Environmental conversion factors are physical features of the location or built environment, such as wheelchair friendly roads and public transport (Lewis Citation2012; Díaz Ruiz, Durán, and Palá Citation2015; Robeyns Citation2017; Burchardt Citation2004).

Freedom, a fundamental component of the CA, is defined as the absence of constraints in choice (Robeyns Citation2017) and is key for a robust translation of the theory of the CA into practice (Sen Citation1990; Robeyns Citation2017). For capabilities to be genuine opportunities, the following conditions for free choice have been proposed: the presence of desirable alternatives or options; agency as the power to choose freely; freedom to actualise preferences without constraints whether, how and to which extent to perform a functioning; unconditionality of one person’s freedom to choose on another person’s functionings; attribution of value to the possible functioning; robustness or the probability that the freedom may be actualised (Robeyns Citation2017); and security of the freedom or the guarantee that the functioning can be sustained over time (Wolff and de-Shalit Citation2013). The CA also acknowledges circular relationships or feed-back loops. Improvement chains of functionings or capabilities that reinforce overall benefits and accumulate positive outcomes are called fertile functionings; negative loop-backs are termed corrosive disadvantage (Wolff and de-Shalit Citation2013). For example, for children with disabilities, playing is regarded as a key fertile functioning as it promotes social inclusion. By contrast, encountering stigma is a negative loop-back as it may hinder parents taking children to play in public parks and accessing support services (Sterman Citation2018).

The capability approach has been used both as a way of designing new policy initiatives and for evaluating those that are already in place across diverse relevant policy domains including disability policy (Díaz Ruiz, Durán, and Palá Citation2015) and active living in built environments (Lewis Citation2012). In more evaluative modes, the capability approach has proven productive in focusing attention on the meaningful end outcomes of policy interventions (Richardson Citation2015), opening up overly simplistic understandings of the multidimensionality and intersectionality of social problems, and recognising the sets of conversion factors that serve to differentiate the capabilities of people in different circumstances and settings (Pham Citation2017). In relation to energy policy, a few examples of evaluations using the capability approach have been oriented towards specific technological developments such as micro-hydropower (Arnaiz et al. Citation2018), rural electrification (Fernández-Baldor et al. Citation2013) and the assessment of smart energy systems (Hillerbrand, Milchram, and Schippl Citation2019). The relationship between energy access and health has been part of such evaluations, but not their direct focus or main policy-related concern.

In this paper we focus on the conceptualisation of being able to heat the home as a crucial secondary capability that is needed for the achievement of the primary or basic capability of sustaining good health in cool climates (Willand and Horne Citation2018; Day, Walker, and Simcock Citation2016). Being able to heat the home is a function of material conditions, such as having a heating device, social conditions, such as knowing how to operate it, and economic conditions, such as being able to afford the costs(Willand and Horne Citation2018; Willand, Maller, and Ridley Citation2019). Studies that have sought to find links between (lack of) the ability “to heat the home”/ “keeping the home warm” and health outcomes highlight the importance of considering the following: a spectrum of capabilities (e.g. in the frequency of this (in)ability), the amplification of outcomes in functionings through bundles of (in)capabilities (e.g. the difficulty in making ends meet) and alternative secondary functionings (e.g. achieving bodily warmth by “staying in bed longer”) (Wilkinson et al. Citation2004, 3; Sartini et al. Citation2018). Although the CA’s freedom of choice tenet acknowledges that people may decline heating even though they may have the capability (Walker Citation2013), such denial of available warmth would need a careful investigation of the underlying causes and conditions that have contributed to this decision and its risk to health.

Methodology

This narrative review uses the growing body of existing research to first map the conditions that have been found to shape the capability and freedom of heating adequately in Victoria, Australia. Next, it evaluates current government policies and initiatives that address energy vulnerability. The search process was iterative starting with the personal document collections of the authors who have acknowledged research expertise and experience in the topic areas of cold homes, residential energy efficiency, energy justice and capabilities. This was complemented by a search for studies in the academic data bases Scopus, ProQuest, Science Direct, Google Scholar and the Internet using key word combinations including “able to heat”, “Victoria”, “Australia”, “indoor temperatures”, “energy” “hardship OR poverty OR vulnerability” without publication date restrictions. As new themes emerged and explanations were sought, new searches were conducted using relevant search terms. We have drawn on quantitative explorations of primary and secondary data sets and qualitative studies on householder lived experiences and included peer-reviewed and grey literature. The data collection included COVID-19 related Victorian Government initiatives to tackle energy deprivation due to the lockdown during the winter of 2020, when income losses and concern about bills forced many households to curtail their heating (Jemena Citation2020).

In our analysis, we developed matrices that corresponded to the categories of policy responses and used qualitative content analysis to map policy design features against key CA components. Finally, we evaluated whether the design or implementation of the policy tools promoted capabilities.

In this practical application, we focus on capabilities rather than functionings (Robeyns Citation2006) due to the conflicting epistemological assumptions that may be used to assess the valued functioning of achieving adequate warmth (Parson Citation2002), uncertainties around sufficiency levels of indoor temperatures for health (WHO Citation2018) and limited data on indoor temperatures in Victoria (Willand and Ridley Citation2015; Daniel, Soebarto, and Williamson Citation2015). Nonetheless, our definition of heating adequately is guided by the general WHO recommendations of a minimum of 18°C in all rooms of a home (WHO Citation2018). From a CA perspective, this reliance on one threshold may be interpreted as being problematic since it assumes that humans are a mostly thermally homogenous species, and since it ignores possibly interaction of physiological adaptation or alternative secondary functionings (Day, Walker, and Simcock Citation2016). However, whilst recognising these complexities, it is beyond the scope of this paper to explore in any detail how adequate warmth should be defined, measured and evaluated.

Mapping energy vulnerability and heating-related capabilities in Victoria, Australia

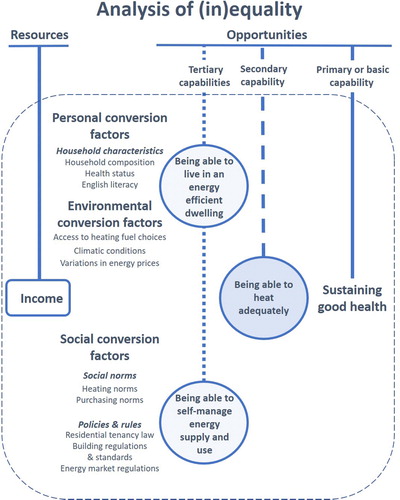

In this section, we synthesise the body of literature relevant to understanding energy vulnerability in Victoria to map the circumstances and mechanisms that shape the secondary capability and freedom to heat a home adequately. In mapping, we have identified two “tertiary capabilities” that feed into the ability to heat adequately, first, “being able to self-manage energy supply and use”, and second, “being able to live in an energy efficient dwelling” (). The discussion below moves through these three capabilities in turn.

Figure 1. A systemised map of conversion factors and capabilities relevant to heating the home and health.

Being able to heat adequately

Statistics on the (in)ability to heat in Australia frame the problem as an indicator of financial stress (ABS Citation2012b, 282) Recent estimates based on surveys with representative samplings have suggested that up to five per cent of Victorian households are not able to afford to heat their home (ABS Citation2017; VCOSS Citation2018)Footnote1 and that about two percent of households may experience persistent heating inability over consecutive years (VCOSS Citation2018). Income seems to be a key but not the only limiting determinant. About three out of four households with persistent inability to heat are in the lowest two income quintiles, and almost half of these are also persistently not able to pay bills (VCOSS Citation2018). However, one in ten households in the top income quintile have also reported persistent heating inability, and a quarter of households with persistent heating inability denied difficulties with bill payments (VCOSS Citation2018). These seemingly paradoxical findings suggest that the ability to heat may be influenced by conditions other than financial impediments.

Household characteristics appear to be important personal conversion factors at the household level of analysis. Single, couple and shared households, households with a disabled or chronically ill member, and those headed by someone without formal education beyond school are overrepresented in the cohort with persistent heating inability, whereas couples with children are underrepresented (VCOSS Citation2018). People’s susceptibility to cold may affect their demand for heating (Willand and Horne Citation2018; Willand, Maller, and Ridley Citation2017, Citation2019), although a simple presumption about the relation between poorer health status of household members and higher levels of indoor heating cannot be made. For example, pride in frugality, normalisation of cold homes, poor awareness of the links between cold homes and health has been associated with cooler homes among older Victorians. Advancing age, medication and a less active lifestyle have also been linked to warmer temperatures (Willand and Horne Citation2018; Moore, Strengers, and Maller Citation2016; Willand, Maller, and Ridley Citation2017, Citation2019). Nonetheless, among older people with chronic health issues, the criterion of unconditionality in the freedom to choose to heat may not be fulfilled when the realisation of warmth must compete with food and medical goods and services (Willand and Horne Citation2018). Corrosive disadvantages have been observed when people compromised on social activities or nutritious food in favour of heating bill payments or when householders accepted the exacerbation of respiratory diseases through heaters that caused air pollution (Willand, Maller, and Ridley Citation2017).

Three studies that have monitored indoor temperatures have shown that independent of income, few Victorian homes are adequately heated according to standard comfort or health criteria, even during evening hours when householders were likely to have been at home (Willand and Ridley Citation2015; Willand, Maller, and Ridley Citation2019; Daniel, Soebarto, and Williamson Citation2015). However, health care responsibilities may promote the value of heating in homes with older or chronically ill persons (Willand, Maller, and Ridley Citation2017; Moore, Strengers, and Maller Citation2016) and children (Willand, Maller, and Ridley Citation2019; Watson et al. Citation1998).

Social conversion factors may also inhibit empowerment and agency in heating decision making. As Victoria does not have smart metres for gas, even people with digital technology skills have feared unexpectedly high bills and refrained from heating because they were unable to monitor the running costs of heating (Willand, Maller, and Ridley Citation2017). Agency refers to the freedom to choose whether to heat and to what level of warmth. Research with older householders has shown how warmth in the home needed to be negotiated among household members. Moreover, imbalances in power were exacerbated by being able to heat only one room in the home (Willand and Horne Citation2018; Willand, Maller, and Ridley Citation2017), as more expensive electrical portable heaters were needed in bedrooms (Willand, Maller, and Ridley Citation2017; Watson et al. Citation1998; Moore, Strengers, and Maller Citation2016; Daniel, Soebarto, and Williamson Citation2015).

In addition, environmental conversion factors emerged from the geographical location, which has been found to affect the ability to heat adequately due to variations in climate, energy prices and fuel choice options. Persistent heating inability appears to be higher in regional than in metropolitan areas (VCOSS Citation2018). This may be linked to colder climatic conditions (ABCB Citation2012), lower average income levels in regional areas (Daley, Wood, and Chivers Citation2017) or limited fuel alternatives. Across Victoria, seven out of ten homes use reticulated mains gas, liquified petroleum gas (LPG) or bottled gas for heating (CUAC Citation2014b). As access to reticulated mains gas is more common in metropolitan Melbourne than in the rest of Victoria (CUAC Citation2014b), and heating with reticulated gas costs half as much as with liquified petroleum gas (Sustainability Victoria Citation2020a), households in regional areas without access to mains gas are likely to carry a higher financial burden (CUAC Citation2014a). However, homes in rural regions are more likely to have access to rooftop solar PV electricity generation and insulation than major urban centres (Chandrashekeran and Li Citation2019; ABS Citation2012a), which may help with affording heating.

Being able to live in an energy efficient dwelling

Differences in prevalence to such energy efficiency features highlight the importance of what we have positioned in as the dependent or tertiary capability of being able to live in an energy efficient dwelling. This captures housing materialities, the knowledge and skills related to residential energy efficiency as well as the opportunity to achieve such a quality. Being able to live in an energy efficient dwelling may be shaped by financial resources, access to retrofit products and services and structural conditions, such as building regulations and tenancy laws.

Evidence suggests that poor residential energy efficiency is a contributing factor to the high prevalence of lack of ability to heat among low-income households and renters in Victoria. Homes with insulation tend to be warmer in winter than those without (Harrington, Aye, and Fuller Citation2015). However, low-income households and renters in Victoria are less likely to have insulation than other households (ABS Citation2021c; VCOSS Citation2018). Private rental properties have also presented inferior efficiency of heating appliances (ABS 2010; VCOSS Citation2010), a lower incidence of central heating and a higher prevalence of expensive electric heating than in owner occupied homes (Energy Consult Citation2009; VCOSS Citation2010). Spatial analyses in urban centres also indicate that rented properties may have disproportionately fewer solar PV panels (Chandrashekeran and Li Citation2019).

Building regulations, a social conversion factor, mandate energy efficiency standards for new homes or major alterations irrespective of tenure (Willand and Horne Citation2013). However, there are no obligations to improve the thermal envelope or efficiency of appliances of existing homes, no standards around heating or energy efficiency in minimum private rental standards, and private renters are dependent on their landlord’s initiative or approval of such measures (CAV Citation2016). This lack in agency is exacerbated by limited financial resources and the prevalence of short-term leases, with average rental periods in Victoria being around two years (Tenants Union of Victoria Citation2015). In Victoria, more than half of all rental households have a relatively low income and almost half are struggling with paying rent (Tenants Union of Victoria Citation2015). The energy efficiency of much Victorian public housing stock may be considered poor, too, as six out of ten homes have been built before the introduction of the first residential insulation standards in 1991 (Greaves Citation2017; Sustainability Victoria Citation2014). However, public housing renters may be in a more privileged position as they may alter their homes, provided that they cover the costs themselves (DHHS Citation2020a). Nonetheless, recent research has found that renters displayed a low level of awareness of residential energy efficiency and expressed little interest in such features (Energy Consult Citation2009; Hoye et al. Citation2020). This limited understanding of energy efficiency may be shaped by social conversion factors, as energy efficiency of homes is seldom considered in the valuation or advertisements of rental properties (Warren-Myers, Kain, and Davidson Citation2020; VCOSS Citation2010).

The availability of heating technologies and options to make choices about these are also important to achieving an energy efficient home that can be warm in all its rooms. The extent of fixed heating in Victorian homes tends to be restricted to the living room (Willand, Maller, and Ridley Citation2017; Watson et al. Citation1998; Moore, Strengers, and Maller Citation2016; Daniel, Soebarto, and Williamson Citation2015). Victorian public housing standards mandate that dwellings must be furnished with one individual heating device (DHHS Citation2018, 26). Central heating, which is usually using fan-forced ducted heating, is discouraged due to the potential risk of “fire spread and cost of operation” (DHHS Citation2018, 26). Achieving a desired level of warmth throughout the dwelling also requires thermostats that can regulate rooms to a desired setpoint in all heated rooms.. However, older inefficient wall or portable heaters and central heating systems often only have manual dials without temperature displays, and newer central heating systems tend to have only one thermostat in the living/ living & kitchen areas (Willand, Maller, and Ridley Citation2017, Citation2019; Watson et al. Citation1998; Daniel, Soebarto, and Williamson Citation2015).

Being able to self-manage energy supply and use

Whilst being able to manage energy supply and use is closely related to the energy efficiency of the home, we identify this as part of a distinct tertiary capability as shown in . This tertiary capability centres on the expectations within the energy system in Victoria for consumers to self-manage and make decisions about their energy supplies and consumption patterns, including through active participation in the energy market. The neoliberal tenets of the commodification of essential services in Victoria, the expectations of economic participation as well as the reliance on individual rather than collective responsibility (Chandrashekeran Citation2016) may disadvantage vulnerable people. These may include those who lack the competencies to compare and select energy offers, and who become entrapped in detrimental agreements. The latter include so-called standing offers, which are basic agreements for unengaged householders that tend to be more expensive than average market offers (EWOV Citation2020), and pay-on-time discounts, which may be regressive as they penalise households with financial constraints (ACCC Citation2018). In addition, some retailer practices seem to be entrenching the burden of financially weak customers by presenting them with unfavourable contract options (Nelson et al. Citation2019), or designing unaffordable hardship plans (ESC Citation2016). Comparison of average electricity prices across population groups and related qualitative work suggest that social conversion factors also contribute to inequalities in opportunity. These include English literacy, self-advocacy skills, self-efficacy, social networks and trust, social norms of loyalty and bargaining, as well as digital and technological competencies (Acil Allen Consulting Citation2018; Willand and Horne Citation2018; Colmar Brunton Citation2018).

Summary

The map () is based on surveys using the subjective measure of being “unable to heat the home” and qualitative studies that focused on rental households and older people. However, the evidence makes clear the diversity, complexity and dynamism in the system of contributing capabilities, components and processes that shape being able to heat the home adequately. Hence, using aggregate community characteristics to identify policy target groups may overlook individual conditions and constraints that can modify capabilities and freedoms. Moreover, interventions may be ineffective if they are not sensitive to such considerations. In the next section we move onto policy measures in Victoria to evaluate how they are positioned in relation to the situated capability map we have outlined.

Use of CA map to evaluate policies in Victoria (Australia)

Victoria presents four policy responses to energy vulnerability: Energy concessions, promotion of housing energy efficiency, information provision and consumer protection measures. In this section we move through each of these using the normative reference that being able to heat the home is a valuable secondary capability that should be actualisable without constraints. Following suggested CA-informed criteria for the egalitarian outcomes of policies and their delivery (Abel and Frohlich Citation2012; Smith, Hodges, and Broman Citation2020), we explore whether the following conditions are met:

Initiatives give priority to the improvement of the capabilities of disadvantaged groups;

Initiatives promise to lead to more adequate or comfortable indoor temperatures;

Initiatives mitigate choice limiting conditions and tertiary (in)capabilities;

Initiatives acknowledge population diversity;

Initiatives are attempted in an integrative fashion.

The subsections below summarise the outcomes of this evaluation. More detailed breakdowns of how these policies and initiatives address the components of the CA map are available in the Appendix.

Energy concessions

Energy concessions focus on income as a resource (in ) and aim to improve energy affordability. Targeting welfare recipients, such as low-income households and pensioners, may be a cost-effective way of identifying disadvantaged households, but exclude struggling households with income above the welfare threshold (QCOSS Citation2014). Energy concessions are also not sufficient to guarantee the capability of heating among all beneficiaries (VCOSS Citation2018). Contributing explanations are that the percentage discount on energy bills does not take into consideration the variation in energy efficiency of dwellings, other essential household expenses, higher energy prices in regional areas of Victoria (Johnston Citation2013) and higher heating demands in colder climate zones (ABS Citation2012a). Energy concessions holders may also be less competent in negotiating a favourable energy contract than non-welfare recipients (Colmar Brunton Citation2018). Therefore, enhancing affordability through the blunt criterion of being a welfare recipient does not match well with the interplay of conversion factors across the population and is insufficient to ensure the capabilities at the core of addressing energy vulnerability.

Householders with particular health needs that act as significant conversion factors are also targeted and supported through the Life Support and Medical Cooling Concessions, to protect health in hot weather; however, there is no equivalent to support the costs of medically indicated heating needs associated with low temperature risks. Although households with very high energy costs (above a set threshold) may apply for an additional discount (DHHS Citation2020b), this may not adequately capture the dynamics of energy price increases, so that high-usage households below the defined threshold may be disproportionately burdened by high energy costs (Johnston Citation2013). Furthermore, the additional application processes for Excess Electricity and Gas Concessions and the requirement to reapply for concessions yearly among some welfare recipients call on the individual’s initiative and may disadvantage or exclude people with limited capacity to navigate the system (Johnston Citation2013; Willand and Horne Citation2018).

In addition, there is evidence that energy concessions are becoming less effective to secure essential energy services over time. Firstly, energy price increases outpace the adjustment of income support payments (ACCC Citation2018), and secondly, the energy bills of concession card holders have increased despite reductions in their gas and electricity consumption (Thwaites, Faulkner, and Mulder Citation2017). As householders on welfare payments are left with increasingly less money for non-energy purposes, the freedom to heat is likely to become more and more conditional on other functionings.

Promotion of housing energy efficiency

This policy response focuses on what we have positioned as an important tertiary capability and has been supported through regulations, retrofit support and access to renewable energy systems. Better energy efficiency may lead to cumulative advantages or fertile functionings by increasing disposable incomes, improving housing quality in general and reducing health disparities (Lewis, Hernández, and Geronimus Citation2019). Assessing various measures against the capability map finds that while minimum energy ratings for new homes promise more egalitarian outcomes, retrofit and solar PV subsidies to improve the existing housing stock appear regressive.

Housing energy efficiency is promoted by minimum ratings for new homes and retrofit subsidies for existing housing on the premise that “energy efficient homes will be more comfortable” and “cost less to heat” (DELWP Citation2020a). The heating assumptions in the new homes rating tool (NatHERS National Administrator Citation2012) reflect the WHO’s recommendations of adequate levels of heating throughout the dwelling. Minimum energy efficiency standards are progressive in their effects as they promise better comfort even without active heating and as they apply to all new homes and major alterations irrespective of tenure (DELWP Citation2020a). While homebuyers experience varied challenges in trying to build homes with more than minimum energy efficiency (Warren-Myers and McRae Citation2017), public housing authorities have been proactive in enhancing this tertiary capability for disadvantaged householders. Standards for new low-rise public housing units mandate higher than minimum home energy ratings, the provision of a highly efficient room heater and solar PV panels, as well as all-electric energy services to avoid the costs of an additional gas connection (DHHS Citation2018). These guidelines promise above average thermal comfort and low energy costs for the most disadvantaged people (Moore et al. Citation2015). However, the restriction of heating systems to the living room compromises the tertiary capability of being able to self-manage energy use, by potentially necessitating expensive portable systems in sleeping areas (Willand and Horne Citation2018).

Retrofit subsidies aim to reduce the barrier of capital costs of the construction works (Willand and Horne Citation2013) and promise security in the freedom to heat by addressing the tertiary capability to live in an energy efficient home. The Victorian Energy Upgrade programme offers discounts for domestic retrofits and appliance upgrades through energy efficiency obligations. The subsidies are available to all households without means testing or consideration of the overall energy efficiency of the home (ESC Citation2019). Although the programme may benefit non-participants indirectly, low-income households and renters still face barriers such as unaffordable capital costs and needing their landlords’ approval (DELWP Citation2019). As these householders are likely to be disproportionally affected by energy vulnerability, and as retailers recoup their costs through higher energy bills across all households, the programme may be regressive (Willand et al. Citation2020).

However, the COVID-19 crisis has triggered the announcement of minimum energy efficiency standards for private rental properties (D'Ambrosio Citation2020a). The Minister’s statement that having “to put up with old, dodgy heaters and cold, poorly insulated homes” (D'Ambrosio Citation2020a) is not acceptable, acknowledges the limited freedom of choice of renters. Although the details have not yet been released, it is expected that the new standards will include the provision of “a fixed heater in good working order […] in the main living area” with a minimum energy efficiency standard and insulation (“Residential Tenancies Regulations Citation2019. Draft for Consultation” Citation2019, 152; D'Ambrosio Citation2020a). Enforcement, however, may be problematic in a tight rental market, and widen the capabilities gap between renters and owners (Daniel et al. Citation2020).

The Victorian Government also promotes the uptake of residential electricity micro-generation through the Solar Homes Program. Free solar electricity can reduce heating costs and thus sustainably support the capability to heat homes. However, the Program does not give priority to helping low-income households or renters. The Program offers rebates and interest free loans for the installation of solar PV cells, hot water systems and batteries (Solar Victoria Citation2020c). The eligibility criteria for the owner occupiers’ scheme only excludes ten per cent of Victorian wealthiest households (.idCommunity Citation2020; Andrews Citation2018) and may not reach those who cannot afford the upfront costs. The Solar for Rentals programme aims to share its benefits with renters by offering landlords a discount and an interest-free loan (Solar Victoria Citation2020d). Although landlords may not increase rents because of the solar PV installation (Solar Victoria Citation2019b), they may negotiate tenant co-payments (Solar Victoria Citation2020a). This can cause equity challenges as it may favour wealthier tenants who can afford co-contributions, while low-income tenants with limited housing choices may feel coerced by the landlord-tenant power imbalance. While renters in private rental and community housing may access the grants (Solar Victoria Citation2020b), equally vulnerable public housing tenants are not eligible (Solar Victoria Citation2019a). Considering that the increased uptake of solar PV among householders is leading to higher fixed charges, households without solar PVs who are struggling to pay their bills are experiencing a double disadvantage (Thwaites, Faulkner, and Mulder Citation2017).

Information provision

Information tools aim to empower people on the premise that knowledge will lead to action and include energy saving behavioural advice, assistance with negotiating the energy market and audits of the energy efficiency of the home (Willand and Horne Citation2013). However, there is little evidence that these measures improve the relevant tertiary and secondary capabilities in our map due to limited customisation. Nevertheless, new integrated initiatives that target vulnerable householders through community organisations promise to improve equality.

Energy advice in Victoria focuses on reducing the costs of heating. It includes recommendations such as adding ceiling insulation, draught proofing, heating only occupied rooms, turning off heating overnight, closing window blinds and curtains, putting on more layers of clothes, and keeping the thermostat setting between 18 and 20°C (Sustainability Victoria Citation2020b). The messages assume that all households are similarly organised and constituted without consideration of differences in personal conversion factors, such as household characteristics, or tertiary capabilities of energy self-management and housing energy efficiency choices (Willand, Maller, and Ridley Citation2017). The Victorian Energy Compare online tool (DELWP Citation2020e) also allows customers to compare the complex and ever-changing market and proposes the cheapest energy offers tailored to the individual household’s location, eligibility for concessions and energy consumption. Use of the tool is incentivised with $50, and visitors are encouraged to engage with behavioural energy saving advice (DELWP Citation2020d). Behavioural energy advice and market-offer comparison tools suggest that householders are responsible and accountable for their own energy hardship (Scerri Citation2011). However, they ignore that customers who are already curtailing their energy consumption have limited opportunity to reduce their overall energy bills even further (Thwaites, Faulkner, and Mulder Citation2017). The narrative around affordability may, thus, entrench inequalities in capabilities by encouraging wealthier customers to keep using energy and inhibiting poorer ones from achieving adequate warmth (Strengers Citation2008).

While existing homes do not have mandatory energy efficiency rating assessments, the Victorian voluntary Scorecard assessment provides an indication of a dwelling’s energy efficiency and provides retrofitting recommendations tailored to its materialities (DELWP Citation2020c). Pilot studies have shown that Scorecard assessments have little effect in satisfying the tertiary capability to live in an energy efficient dwelling among low-income households. This was due to the cost of the assessment, low levels of awareness of the tool, the lack of financial support to undertake the recommended retrofits and the need for “more tailored information alongside the Scorecard certificate that better reflects the advice provided by the assessor” (COAG Energy Council Citation2019, 7).

In response to concerns about an energy affordability crisis due to the COVID-19 lock-down during the winter of 2020, the Victorian Government is trialling initiatives that take more integrated and customised approaches. These include the training of community workers to improve people’s energy self-management capabilities (D'Ambrosio Citation2020b) and asking charities to negotiate energy contracts, broker hardship plans and facilitate access to concessions and retrofit assistance (BSL Citation2020). The overview of initiatives is offered in ten languages (DELWP Citation2020b). Although Victoria strives to provide equitable access to services to people with low English proficiency (Victorian Department of Premier and Cabinet Citation2019), the provision of these guidelines may be the only initiative that acknowledges cultural and linguistical diversity and limited English literacy as conditions that constraint energy-related capabilities.

Protection of consumers in the energy market

Consumer protection initiatives also address the tertiary capability of being able to self-manage energy supply and use. They acknowledge that people may not equally be able to negotiate the retail energy market (ESC Citation2020a) and aim to improve the quality and fairness of energy service contracts and to enhance the financial capacities of householders. Recent Victorian reforms are shielding householders from the most exploitative practices. However, householders who are unable to actively engage in the negotiation of contracts are still disadvantaged.

In 2019, Victoria introduced energy market reforms to “deliver lower prices”, “empowering consumers” and “supporting vulnerable consumers” (DELWP Citation2019). The reforms introduced the Victorian Default Offer (VDO) with a regulated and better, though not the best, electricity price to replace the disadvantageous standing offers (Essential Services Commission Citation2020). However, standing offers for gas persist with significantly higher prices than the average market agreement (Essential Services Commission Citation2020). In addition, a new “best offer” statement on every electricity or gas bill discloses whether the current contract is the cheapest option for the individual household (EWOV Citation2020). The fact that some consumers are still on expensive gas standing offers shows that the mere display of the “best offer” may not be enough to protect customers whose limited self-initiative or competencies constrain telephone or digital communication (Willand and Horne Citation2018). Nonetheless, a decline in the number of pay-on-time discounts and lower discount rates suggest that the reform has improved fairness (Essential Services Commission Citation2019).

Since July 2020, retailers are required to credit the pay-on-time discounts of hardship customers, even if they miss a timely payment (Essential Services Commission Citation2020), and to offer help to hardship customers, which has reduced the number of disconnections (Essential Services Commission Citation2020). The Victorian government has also put temporary obligations on energy retailers to check householders’ eligibility for energy concessions and whether they are on the best offer when consumers call to report payment difficulties (ESC Citation2020b).

However, these measures may not offer security, or the ability to sustain the freedom to heat over time if the tertiary capability to live in an energy efficient home is not strengthened simultaneously. There is also concern that reticulated gas may not be the reliable and low-price choice of heating fuel for much longer, and that Victorian households who rely on gas for heating may be disproportionately affected (Thwaites, Faulkner, and Mulder Citation2017; CUAC Citation2014b). Consumer advocates encourage a switch to all-electric services (CUAC Citation2014b). However, this would need to be combined with access to solar PV panels, as currently, rising electricity prices and the cross-subsidisation of solar PV costs are already disadvantaging those who cannot afford or lack the agency to install solar panels on their homes (St Vincent de Paul Society Citation2019).

Discussion and policy implications

In this paper, we have mapped components and processes that contribute to the capability and intrinsic freedom to heat in Victoria and evaluated current policies and initiatives against CA related criteria. The map has shown that the unequal distribution in the opportunity to heat adequately are shaped by wider conditions than income. They are reliant on the two tertiary capabilities of being able to self-manage energy supply and use and being able to live in an energy efficient dwelling, and include structural, geographical and cultural phenomena and feed-back loops.

The evaluation of initiatives against CA criteria (summarised in ) has, firstly, shown that some initiatives focus on energy vulnerability as the inequality of income. This framing may well reflect the methods of identifying disadvantage generally used by energy regulatory organisations (ACCC Citation2018; ESC Citation2020a). However, the COVID-19 crisis has brought about efforts to enhance the tertiary capability of being able to live in an energy efficient dwelling through reform of structural conditions and transformative agency, particularly for renters.

Table 1. Overview of evaluation of policy responses to energy deprivations in Victoria.

Secondly, Victorian policies and initiatives show little effort in tailoring solutions to the multitude and range of less measurable and often hidden factors that serve to constrain heating choices in individual households. Focussing policies on explicit categorises of households acknowledges collective capabilities and the relational interdependencies between social structures, groups and individuals. However, practically, such policies may not capture people’s heterogeneity and the interactions between household resources, tertiary capabilities, personal competencies and other conversion factors.

Finally, the analysis revealed that initiatives are mostly designed as isolated measures rather than holistic interventions. The CA approach highlighted that many interventions fell short of providing transformative agency and may be too narrow to deal effectively with the complexity and interactions of achieving warmth. The new initiatives engage community service agencies and aim to combine contract and hardship plan brokerage, concession checking and retrofit assistance. They sound promising and may help equalise householders’ tertiary capability of being able to self-manage energy supply. Alternative and arguably more CA-conform integrated and personalised models for addressing energy vulnerability may be found in the UK, where warm homes and health have been the hegemonic intent of low carbon policies for decades (“Warm Homes and Energy Conservation Act" Citation2000; NICE Citation2015).

Other recommendations following the CA framework include the introduction of a “Medical Heating Concession”. This would mirror the current concession for cooling in summer and offer discounts on energy bills during winter. In addition, non-English speaking communities should be better included, and favourable contracts should be brokered when energy concessions are first granted. In the context of an ageing population, ensuring welfare recipients are on the best offer may reduce their overall financial concerns, relieve the burden on the public purse (Thwaites, Faulkner, and Mulder Citation2017) and perhaps allow the extension of eligibility criteria to more people. In addition, concessions should reflect energy price developments to ensure sufficiency when energy prices go up.

Conclusion

This paper has conceived energy vulnerability as a set of restrictions of people’s genuine opportunities and used a capabilities map as a guide to assess the outcomes of social policy. We located the investigation in Victoria, Australia. However, the map, which has highlighted how power, tenure and the value attributed to warmth may influence the conversion of financial resources into the capability of heating adequately may be representative of conditions nationwide and in other countries (Daniel et al. Citation2020; Bartiaux et al. Citation2019; Yip, Mah, and Barber Citation2020). In other settings internationally, care would need to be taken to contextualise energy vulnerability in situ, including in terms of what most matters for the relationship between energy use and restricted capability (which may not include heating the home) and the differentiations that are important in social, environmental and personal conversion factors.

Although, in general, using the CA as a policy evaluation tool is constrained by the dynamic and context specific nature of the conceptual model, we found that the utility of the CA in evaluating policies was in counterbalancing the discourse around financial resources and the neoliberal agenda of individual responsibility. The CA perspective calls for a multi-dimensional policy strategy that tackles key components simultaneously, addresses dependencies in a capability hierarchy and encourages the active engagement with conversion factors. It further promotes interventions that promise fertile functionings or structural transformations that are likely to lead to long-term and sustained benefits. This finding logically demands a paradigm shift in policy design as well as in research and policy evaluation. A shift from an economics-oriented perspective to a multi-pronged and multi-layered arena of situated investigation that includes building, social and medical sciences is required. A good start may be to rephrase survey questions in the language of capabilities (Burchardt Citation2004), e.g. “Are your opportunities to heat your home adequately limited in any way?” and “What are the constraints that limit you heating your home adequately?”.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (61.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 “Unable to heat home” is a multiple-choice option for the question: “Over the past year, have any of the following happened to [you/your household] because of a shortage of money?” (ABS Citation2012b, 282). The questionnaire design (ABS Citation2012b, 282) does not allow any inference on the duration or frequency of the event.

References

- ABCB. 2012. “Victoria Climate Zone Map.” In.: Australian Building Codes Board.

- Abel, T., and K. L. Frohlich. 2012. “Capitals and Capabilities: Linking Structure and Agency to Reduce Health Inequalities.” Social Science and Medicine 74 (2): 236–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.028.

- ABS. 2012a. 46022DO001_201208 Household Water and Energy Use Victoria, Oct 2011.” In edited by Australian Bureau of Statistics. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- ABS. 2012b. “Household Expenditure Survey and Survey of Income and Housing: User Guide, Australia, 2009-10 (cat.no. 653.0) Paper Questionnaire.” In. Canberra.

- ABS. 2017. “Household Expenditure Survey, Australia: Summary of Results, 2015–16. 11 Financial Stress Indicators.” In edited by Australian Bureau of Statistics. Canberra.

- ABS. 2019. “3218.0 - Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2017-18. Main Features.” Australian Bureau of Statistics, Accessed September 21. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/mf/3218.0.

- ABS. 2021a. “2016 Census QuickStats_ Victoria.” Australia Bureau of Statistics, Accessed April 25. https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/2?opendocument.

- ABS. 2021b. "National, state and territory population. December 2020." Australian Bureau of Statistics, Accessed July 31. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/national-state-and-territory-population/latest-release.

- ABS. 2021c. “4602.2 - Household Water, Energy Use and Conservation, Victoria, Oct 2009. Insulation.” Australian Bureau of Statistics. Accessed July 31. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Products/4602.2~Oct+2009~Chapter~Insulation.

- ACCC. 2018. “Restoring electricity affordability and Australia’s competitive advantage. Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry—Final Report.” In. Canberra: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.

- Acil Allen Consulting. 2018. “Supporting Households to Manage Their Energy Bills. A Strategic Framework.” In. Melbourne.

- ACOSS. 2019. “Health of the NEM - Current and emerging energy affordability issues for people on low incomes.” In. Strawberry Hills, NSW.

- Andrews, Daniel. 2018. “Cutting Power Bills With Solar Panels For 650,000 Homes.” In. Melbourne.

- Arnaiz, M., T. A. Cochrane, R. Hastie, and C. Bellen. 2018. “Micro-hydropower Impact on Communities’ Livelihood Analysed with the Capability Approach.” Energy for Sustainable Development 45: 206–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2018.07.003.

- Bartiaux, Françoise, AlfredoCartone Mara Maretti, Philipp Biermann, and Veneta Krasteva. 2019. “Sustainable Energy Transitions and Social Inequalities in Energy Access: A Relational Comparison of Capabilities in Three European Countries.” Global Transitions 1: 229–240.

- Bartiaux, Françoise, Christophe Vandeschrick, Mithra Moezzi, and Nathalie Frogneux. 2018. “Energy Justice, Unequal Access to Affordable Warmth, and Capability Deprivation: A Quantitative Analysis for Belgium.” Applied Energy 225: 1219–1233. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.04.113.

- Bouzarovski, Stefan, Saska Petrova, and Sergio Tirado-Herrero. 2014. “From Fuel Poverty to Energy Vulnerability: The Importance of Services, Needs and Practices.” In SPRU Working Paper Series. Brighton.

- BSL. 2020. “Energy assistance and brokerage.” Brotherhood of St. Laurence, Accessed October 17. https://www.bsl.org.au/services/energy-assistance/energy-assistance-and-brokerage/.

- Burchardt, Tania. 2004. “Capabilities and Disability: The Capabilities Framework and the Social Model of Disability.” Disability & Society 19 (7): 735–751. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759042000284213.

- CAV. 2016. “Regulation of Property Conditions in the Rental Market. Issues Paper. Residential Tenancies Act Review “ In.: Consumer Affairs Victoria.

- Chandrashekeran, Sangeetha. 2016. “Multidimensionality and the Multilevel Perspective: Territory, Scale, and Networks in a Failed Demand-Side Energy Transition in Australia.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48 (8): 1636–1656. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518 ( 16643728.

- Chandrashekeran, Sangeetha, and Fanqi Li. 2019. “Exploring the Social-Spatial Context of the Energy Transition.” In State of Energy Research conference Canberra: Australian National University.

- Churchill, Sefa Awaworyi, Russell Smyth, and Lisa Farrell. 2020. “Fuel Poverty and Subjective Wellbeing.” Energy Economics 86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2019.104650.

- COAG Energy Council. 2019. “Residential Efficiency Scorecard Research Pilot Evaluation Report.” In. Canberra.

- Colmar Brunton. 2018. “Consumer Outcomes in the National Retail Electricity Market." Final Report. Canberra: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.

- CUAC. 2014a. “Our Gas Challenge, The Role of Gas in Victorian Households.” In. Melbourne.

- CUAC. 2014b. “Our Gas Challenge: The role of gas in Victorian households.” In. Melbourne: Consumer Utilities Advocacy Centre Ltd.

- Daley, John, Danielle Wood, and Carmela Chivers. 2017. Regional Patterns of Australia’s Economy and Population. Melbourne: Grattan Institute.

- D'Ambrosio, Lily. 2020a. “"Helping Victorians Pay Their Power Bills." State Government of Victoria, Accessed November 17. https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/helping-victorians-pay-their-power-bills.

- D'Ambrosio, Lily. 2020b. “"Targeted Support For Victorians Struggling With Energy Bills." Lily D'Ambrosio. Accessed May 13. https://www.lilydambrosio.com.au/media-releases/targeted-support-for-victorians-struggling-with-energy-bills/.

- Daniel, Lyrian, Emma Baker, Andrew Beer, and Ngoc Thien Anh Pham. 2019. “Cold Housing: Evidence, Risk and Vulnerability.” Housing Studies, 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1686130.

- Daniel, Lyrian, Trivess Moore, Emma Baker, Andrew Beer, Nicola Willand, Ralph Horne, and Cathryn Hamilton. 2020. “Warm, cool and energy-affordable housing policy solutions for low-income renters.” AHURI Final Report (338). doi: 10.18408/ahuri-3122801.

- Daniel, Lyrian, Veronica Soebarto, and Terence Williamson. 2015. “House Energy Rating Schemes and Low Energy Dwellings: The Impact of Occupant Behaviours in Australia.” Energy and Buildings 88: 34–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2014.11.060.

- Day, Rosie, and Gordon P. Walker. 2013. “Household Energy Vulnerability as Assemblage.” In Energy Justice in a Changing Climate: Social Equity and Low-Carbon Energy, edited by Karen Bickerstaff, Gordon P. Walker, and Harriet Bulkeley, 14. London: Zed Books.

- Day, Rosie, Gordon Walker, and Neil Simcock. 2016. “Conceptualising Energy Use and Energy Poverty Using a Capabilities Framework.” Energy Policy 93: 255–264. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.03.019.

- DELWP. 2019. “Regulatory Impact Statement. Victorian Energy Efficiency Target Amendment (Prescribed Customers and Targets) Regulations 2020.” In. Melbourne.

- DELWP. 2020a. “Independent and Bipartisan Review of the Electricity and Gas Retail Markets in Victoria.” Department of Environment Land Water and Planning, Accessed July 20. https://www.energy.vic.gov.au/about-energy/policy-and-strategy.

- DELWP. 2020b. “Building Standards.” Accessed July 19. https://www.energy.vic.gov.au/energy-efficiency/building-standards.

- DELWP. 2020c. “Having trouble paying your energy bills?.” In. Melbourne.

- DELWP. 2020d. “Victorian Residential Efficiency Scorecard. Fact Sheet 11. Comparing Scorecard and NatHERS.” In.: Victorian Government Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning.

- DELWP. 2020e. “Welcome to Victorian Energy Compare.” Victorian Government Department of Environment Land Water and Planning. Accessed 4 October. https://compare.energy.vic.gov.au/.

- DHHS. 2018. “Housing Design Guidelines. Version 2.0 December 2018.” In. Melbourne.

- DHHS. 2020a. “Making alterations to your home.” Accessed July 5. https://www.housing.vic.gov.au/making-alterations-your-home.

- DHHS. 2020b. “Victorian concessions. A guide to discounts and services for eligible households in Victoria.” In. Melbourne: Department fo Health and Human Services.

- Díaz Ruiz, Alvaro, Natalia Sánchez Durán, and Alexis Palá. 2015. “An Analysis of the Intentions of a Chilean Disability Policy Through the Lens of the Capability Approach.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 16 (4): 483–500. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2015.1091807.

- Energy Consult. 2009. “Housing condition/energy performance of rental properties in Victoria..” In. Melbourne. Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment.

- ESC. 2016. “Supporting Customers, Avoiding Labels. Energy. Hardship Inquiry, Final Report, February 2016.” In. Melbourne.

- ESC. 2019. “Overview of VEU program activities.” Essential Services Commission, Accessed 30 August. https://www.esc.vic.gov.au/victorian-energy-upgrades-program/about-victorian-energy-upgrades-program/overview-veu-activities.

- ESC. 2020a. “Building a strategy to address consumer vulnerability.” In. Melbourne. Essential Services Commission.

- ESC. 2020b. “Supporting energy customers through the coronavirus pandemic. Final decision. 24 August 2020.” In. Melbourne: Essential Services Commission.

- Essential Services Commission. 2019. “Victorian Energy Market Report 2018–19.” In. Melbourne. Essential Services Commission.

- Essential Services Commission. 2020. “Victorian Energy Market Update: June 2020.” In. Melbourne. Essential Services Commission.

- EWOV. 2020. “1 July 2019 Victorian energy market reforms.” Energy and Water Ombudsman. Accessed July 20. https://www.ewov.com.au/customers/1-july-2019-victorian-energy-market-reforms#:~:text=The%20Victorian%20state%20government's%20energy,with%20the%20retail%20energy%20market.

- Fernández-Baldor, Álvaro, Alejandra Boni, Pau Lillo, and Andrés Hueso. 2013. “Are Technological Projects Reducing Social Inequalities and Improving People's Well-Being? A Capability Approach Analysis of Renewable Energy-Based Electrification Projects in Cajamarca, Peru.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 15 (1): 13–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2013.837035.

- Greaves, Andrew. 2017. “Managing Victoria’s Public Housing.” In. Melbourne. Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

- Hall, Sarah Marie, Sarah Hards, and Harriet Bulkeley. 2013. “New Approaches to Energy: Equity, Justice and Vulnerability. Introduction to the Special Issue.” Local Environment 18 (4): 413–421. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2012.759337.

- Harrington, L. W., L. Aye, and R. J. Fuller. 2015. “Characterising Indoor Air Temperature and Humidity in Australian Homes.” Air Quality and Climate Change 49 (4): 21–29.

- Hillerbrand, Rafaela, Christine Milchram, and Jens Schippl. 2019. “The Capability Approach as a Normative Framework for Technology Assessment.” TATuP - Zeitschrift für Technikfolgenabschätzung in Theorie und Praxis 28 (1): 52–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.14512/tatup.28.1.52.

- Hoye, Jasmine, Cat Banks, John Remington, and Erin Allingham. 2020. “Research Report on Energy Efficiency in Rental Properties.” In. Melbourne: Newgate Research.

- idCommunity. 2020. “Victoria. Household income.” Profile.id, Accessed July 11. https://profile.id.com.au/australia/household-income?WebID=110.

- Jemena. 2020. “COVID19 Customer Hardship. Customer Research Insights Report.” In. Sydney: Deloitte.

- Johnston, May Mauseth. 2013. “Winners and Losers: the impact of energy concession caps on low-income Victorians.” In. Melbourne: Consumer Action Law Centre.

- Lewis, Ferdinand. 2012. “Auditing Capability and Active Living in the Built Environment.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 13 (2): 295–315. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2011.645028.

- Lewis, Jamal, Diana Hernández, and Arline T. Geronimus. 2019. “Energy Efficiency as Energy Justice: Addressing Racial Inequities Through Investments in People and Places.” Energy Efficiency. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-019-09820-z.

- Moore, Trivess, Yolande Strenger, Cecily Maller, Ian Ridley, Larissa Nicholls, and Ralph Horne. 2015. “Horsham Catalyst Research and Evaluation. Final Report.” In. Melbourne. RMIT University.

- Moore, Trivess, Yolande Strengers, and Cecily Maller. 2016. “Utilising Mixed Methods Research to Inform Low-Carbon Social Housing Performance Policy.” Urban Policy and Research 34 (3): 240–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2015.1077805.

- NatHERS National Administrator. 2012. “Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS) - Software Accreditation Protocol.” In. Canberra: NatHERS National Administrator.

- Nelson, Tim, Eleanor McCracken-Hewson, Gabby Sundstrom, and Marianne Hawthorne. 2019. “The Drivers of Energy-Related Financial Hardship in Australia – Understanding the Role of Income, Consumption and Housing.” Energy Policy 124: 262–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.10.003.

- NICE. 2015. “Excess winter deaths and illness and the health risks associated with cold homes “ In.: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

- Nussbaumer, Patrick, Morgan Bazilian, Vijay Modi, and Kandeh K. Yumkella. 2011. Measuring Energy Poverty: Focusing on What Matters. OPHI Working paper No. 42. Oxford: University of Oxford.

- Parson, K. C. 2002. Human Thermal Environments. The Effects of Hot, Moderate, and Cold Environments on Human Health, Comfort and Performance. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Pham, Trang. 2017. “The Capability Approach and Evaluation of Community-Driven Development Programs.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 19 (2): 166–180. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2017.1412407.

- QCOSS. 2014. “Energising concessions policy in Australia. Best practice principles for energy concessions.” In. Brisbane: Queensland Council of Social Services.

- Recalde, Martina, Andrés Peralta, Laura Oliveras, Sergio Tirado-Herrero, Carme Borrell, Laia Palència, Mercè Gotsens, Lucia Artazcoz, and Marc Marí-Dell’Olmo. 2019. “Structural Energy Poverty Vulnerability and Excess Winter Mortality in the European Union: Exploring the Association Between Structural Determinants and Health.” Energy Policy 133. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.07.005.

- “Residential Tenancies Regulations 2019. Draft for Consultation.”. 2019.

- Richardson, Henry S. 2015. “Using Final Ends for the Sake of Better Policy-Making.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 16 (2): 161–172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2015.1036846.

- Robeyns, Ingrid. 2005. “The Capability Approach: A Theoretical Survey.” Journal of Human Development 6 (1): 93–117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/146498805200034266.

- Robeyns, Ingrid. 2006. “The Capability Approach in Practice.” Journal of Political Philosophy 14 (3): 351–376.

- Robeyns, Ingrid. 2017. Wellbeing, Freedom and Social Justice: The Capability Approach Re-Examined. Cambridge, UK: OpenBook Publishers.

- Sartini, C., P. Tammes, A. D. Hay, I. Preston, D. Lasserson, P. H. Whincup, S. G. Wannamethee, and R. W. Morris. 2018. “Can we Identify Older People Most Vulnerable to Living in Cold Homes During Winter?” Annals of Epidemiology 28 (1): 1–7 e3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.11.008.

- Scerri, Andy. 2011. “Rethinking Responsibility? Household Sustainability in the Stakeholder Society.” In Material Geographies of Household Sustainability, edited by Ruth Lane, and Andrew Gorman-Murray, 175–192. Surrey, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Sen, Amartya. 1979. “Equality of What?” In Tanner Lectures on Human Values, edited by S. McMurrin, 197–220. Cambridge: Stanford University.

- Sen, Amartya. 1990. “Welfare, Freedom and Social Choice: a Reply.” Recherches Économiques de Louvain / Louvain Economic Review 56 (3/4): 451–485.

- Sen, Amartya. 1992. Inequality Reexamined. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Simcock, Neil, Gordon Walker, and Rosie Day. 2016. “Fuel Poverty in the UK: Beyond Heating?” People Place and Policy Online 10 (1): 25–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.3351/ppp.0010.0001.0003.

- Smith, Karen, Nicky Hodges, and Daisy Broman. 2020. “Social dynamics and energy vulnerability: how can attention to social dynamics help address energy deprivation?” In. Bristol: Centre for Sustainable Energy.

- Smith, Matthew, Carolina Longshore. 2009. “The Relational Ontology of Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach: Incorporating Social and Individual Causes.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 10 (2): 213–235. doi:10.1080/19452820902940927.

- Solar Victoria. 2019a. “Solar for Community Housing.” Solar Victoria, Accessed June 28. https://www.solar.vic.gov.au/solar-community-housing.

- Solar Victoria. 2019b. “Solar for Rental Properties. Help.” Solar Victoria, Accessed June 28. https://www.solar.vic.gov.au/solar-rental-properties-0.

- Solar Victoria. 2020a. “Information for Landlords.” Solar Victoria. Accessed October 12. https://www.solar.vic.gov.au/information-landlords.

- Solar Victoria. 2020b. “Solar for Community Housing.” Solar Victoria. Accessed July 12. https://www.solar.vic.gov.au/solar-community-housing.

- Solar Victoria. 2020c. “Solar Rebates.” Solar Victoria. Accessed October 12. https://www.solar.vic.gov.au/solar-rebates.

- Solar Victoria. 2020d. “Solar Rebates for Rental Properties.” Solar Victoria, Accessed July 11. https://www.solar.vic.gov.au/solar-rental-properties.

- Sterman, Julia. 2018. “Outdoor Play Decision-Making b Families, Schools, and Local Government for Children With Disabilities.” Australian Catholic University.

- Strengers, Yolande. 2008. “Smart Metering Demand Management Programs: Challenging the Comfort and Cleanliness Habitus of Households.” In Proceedings of the 20th Australasian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction: Designing for Habitus and Habitat. Cairns, Queensland: OZCHI.

- St Vincent de Paul Society. 2019. “Options for an Equitable Distributed Energy Resource future.” In. Melbourne: St Vincent de Paul Society Victoria.

- Sustainability Victoria. 2014. “Victorian Households Energy Report.” In. Melbourne: Sustainability Victoria.

- Sustainability Victoria. 2015. “Existing Victorian Houses Energy Efficiency Upgrade Potential.” In. Melbourne: Sustainability Victoria.

- Sustainability Victoria. 2020a. “Calculate Heating Running Costs.” Sustainability Victoria. Accessed July 5. https://www.sustainability.vic.gov.au/You-and-your-home/Save-energy/Heating/Heating-running-costs.

- Sustainability Victoria. 2020b. “Heat Your Home Efficiently.” Sustainabilty Victoria. Accessed October 17. https://www.sustainability.vic.gov.au/You-and-your-home/Save-energy/Heating/Heat-your-home-efficiently.

- Tenants Union of Victoria. 2015. “Victorian Housing & Tenancy Key Statistics.” In. Melbourne.

- Thwaites, John, Patricia Faulkner, and Terry Mulder. 2017. “Independent Review into the Electricity & Gas Retail Markets in Victoria.” In.

- VCOSS. 2010. “Decent not dodgy. ‘Secret Shopper’ Survey.” In. Melbourne.

- VCOSS. 2018. “Battling On. Persistent Energy Hardship.” In. Melbourne.

- Victorian Department of Premier and Cabinet. 2019. “Effective Translations. Victorian Government Guidelines on Polciy and Procedures.” In. Melbourne.

- Walker, Gordon. 2013. “Inequality, Sustainability and Capability. Locating Justice in Social Pratices.” In Sustainable Practices: Social Theory and Climate Change, edited by Elizabeth Shove, and Nicola Spurling, 358–390. Florence: Routledge Advances in Sociology.

- “Warm Homes and Energy Conservation Act.”. 2000. Edited by Elizabeth II. Crown.

- Warren-Myers, Georgia, Catherine Kain, and Kathryn Davidson. 2020. “The Wandering Energy Stars: The Challenges of Valuing Energy Efficiency in Australian Housing.” Energy Research & Social Science 67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101505.

- Warren-Myers, Georgia, and Erryn McRae. 2017. “Volume Home Building: The Provision of Sustainability Information for New Homebuyers.” Construction Economics and Building 17 (2): 24–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v17i2.5245.

- Watson, Lyndsey, Anne Potter, Robyn Gallucci, and Judith Lumley. 1998. “Is Baby Too Warm? The use of Infant Clothing, Bedding and Home Heating in Victoria, Australia.” Early Human Development 51: 93–107.

- WHO. 2018. “WHO Housing and Health Guidelines.” In. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Wilkinson, Paul, S. Pattenden, B. Armstrong, A. Fletcher, R. S. Kovats, P. Mangtani, and A. J. McMichael. 2004. “Vulnerability to Winter Mortality in Elderly People in Britain: Population Based Study.” BMJ 329 (7467): 647. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38167.589907.55.

- Willand, Nicola, and Ralph Horne. 2013. “Low Carbon Residential Refurbishments in Australia: Progress and Prospects.” In State of Australian Cities SOAC 2013. Sydney.

- Willand, Nicola, and Ralph Horne. 2018. ““They are Grinding us Into the Ground” – The Lived Experience of Energy (in)Justice Amongst low-Income Older Households.” Applied Energy 226: 61–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.05.079.

- Willand, Nicola, Cecily Maller, and Ian Ridley. 2017. ““It’s not Too bad” - The Lived Experience of Energy Saving Practices of low-Income Older and Frail People.” Energy Procedia 121: 166–173.

- Willand, Nicola, Cecily Maller, and Ian Ridley. 2019. “Addressing Health and Equity in Residential low Carbon Transitions – Insights from a Pragmatic Retrofit Evaluation in Australia.” Energy Research & Social Science 53: 68–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.02.017.

- Willand, Nicola, Trivess Moore, Ralph Horne, and Sarah Robertson. 2020. “Retrofit Poverty: Socioeconomic Spatial Disparities in Retrofit Subsidies Uptake.” Buildings and Cities 1 (1): 14–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.13.

- Willand, Nicola, and Ian Ridley. 2015. “Quantitative Exploration of Winter Living Room Temperatures and Their Determinants in 108 Homes in Melbourne, Victoria.” In Living and Learning: Research for a Better Built Environment: 49th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association 2015, edited by R. H. Crawford, and A. Stephan, 557–566. Melbourne, Australia: The Architectural Science Association.

- Wolff, Jonathan, and Avner de-Shalit. 2013. “On Fertile Functionings: A Response to Martha Nussbaum.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 14 (1): 161–165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2013.762177.

- Yip, Annie Onni, Daphne Ngar-yin Mah, and Lachlan B. Barber. 2020. “Revealing Hidden Energy Poverty in Hong Kong: A Multi-Dimensional Framework for Examining and Understanding Energy Poverty.” Local Environment 25 (7): 473–491. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2020.1778661.