ABSTRACT

There are many forms of sharing occurring in local communities that can help reduce overconsumption and mitigate the continuous growth of climate emissions. Lately, traditional forms of local sharing have been supplemented with internet-based peer-to-peer sharing applications. This paper applies a social capital perspective to explore the relational basis for different forms of sharing in local communities, and to inform a discussion on how local sharing can be scaled up. Based on a survey of citizens in four municipalities in Norway, four key forms of sharing are explored including p2p-sharing, sharing schemes organised in the community, sharing of time through voluntary work, and informal sharing among friends, family and neighbours. Results indicate that bridging social capital is particularly important for all sharing activities, and that time-sharing is most strongly sustained by social capital. In addition to social capital dimensions, environmental motives also contribute to people’s engagement in face-to-face local sharing. p2p-sharing, however, is to a much lesser degree related to social capital and environmental motives.

1. Introduction

A recurring challenge of the current economic system of production is that it tends to encourage the over-consumption, and even hyper-consumption, of goods and services, resulting in household consumption with a substantial environmental and climatic footprint. There is little doubt that the escalated consumption of everything, from long-distance travel and food to consumer electronics and household energy, represents a threat to the physical environment as much as growing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions do (Ivanova, Stadler, and Steen-Olsen Citation2016). It is estimated that 73 per cent of GHG emissions globally come from household-related activities (Hertwich and Peters Citation2009; Dubois et al. Citation2019), and very steep reductions in emissions are needed if the global community is to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, which aims to reduce emissions from 40 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide in 2020–5 gigatonnes in 2050 and eventually reach a level of “net zero” by 2100.

Several authors have advocated for more local and democratic forms of production, distribution and consumption to speed up behavioural change (Arcidiacono and Gandini Citation2019; Hamari, Sjöklint, and Ukkonen Citation2016; Schor Citation2016; Mi and Coffman Citation2019). Forms of “local sharing” have been considered a promising alternative to market – and reciprocity-based sharing schemes, including the sharing of clothes, toys, tools and vehicles. Studies have documented that under the right conditions, local sharing can help to avoid, or at least delay, waste production via the bartering, swapping, gifting, renting, trading and borrowing of multiple underused or unwanted goods between individuals (Oliveira, Tomar, and Tam Citation2020; Sandin and Peters Citation2018; Jung and Koo Citation2018; Ala-Mantila et al. Citation2017). In the longer term, these systems may represent an important step to curbing overconsumption, reducing GHG emissions and spurring the development of more sustainable lifestyles.

Over the last two decades, there has been much experimentation centring on local sharing as “grassroots social innovations”, where civil society actors play an important role (Smith et al. Citation2016; Seyfang and Longhurst Citation2013; Seyfang and Smith Citation2007; Westskog et al. Citation2021; Whalen Citation2018; Albinsson et al. Citation2019). Such initiatives have proven to promote sustainability through a plethora of different activities, including less fossil fuel-intensive transportation, urban gardening, renewable energy implementation and waste regeneration, among others. As a particular type of social innovation, they are believed as crucial to fostering regional transitions towards a low-carbon economy (Seyfang and Smith Citation2007; Hargreaves et al. Citation2013). However, although promising, these actions and experiments have not been able to scale up in ways that have changed mainstream consumption behaviour (Martellozzo, Landholm, and Holsten Citation2019). There has also been a paucity of research that addresses community-based aspects that can give grassroot innovation initiatives a stronger momentum and enable it to become part of “mainstream” consumer practices (Bennett et al. Citation2016).

In addition, over the last decades, traditional sharing has been supplemented by an upsurge of numerous technology-mediated applications for sharing, including the sharing of cars, accommodation, items, food and more. Particularly influential is peer-to-peer (P2P) sharing, in which sharing, lending or renting between individuals is done through an internet-based application offered by a third party (Bardhi and Eckhardt Citation2012; Belk Citation2014; Botsman and Rogers Citation2011; Agarwal and Steinmetz Citation2019). Compared with traditional community-based sharing, P2P sharing extends the circle of possible lenders and sharers way beyond the local community. These digital technologies are changing the premises and practices for local sharing, and there is a growing interest in how they, combined with traditional forms, may contribute to a shift towards more sustainable consumer practices. This exploratory paper suggests that a closer focus on relational structures and their embedded qualities in a community can give new information on what drives different forms of sharing and the basis for their development. In general, there are good reasons to believe that communities with a well-developed network of social relations are in a better position to circulate information about sharing events and opportunities, facilitate network-based learning and build norms to promote sharing practices. However, little empirical work has been done to investigate this systematically and explore the variation across different forms of sharing and factors that can help to promote them further.

In the literature on sustainable development, social capital has proven essential for building resilience, managing scarce resources, fostering entrepreneurship and improving citizen health (Aldrich and Meyer Citation2015; Kusakabe Citation2012). Furthermore, collective social capital has proven helpful for pooling resources and mobilising in climate-related crises, particularly in the developing world (Kalkbrenner and Roseen Citation2016; Sonderskov Citation2008; Jovita et al. Citation2019; Wickes et al. Citation2015). On an individual level, aspects of social capital dimensions have also proven to be important in terms of concern for the environment (Macias and Nelson Citation2011; Macias and Williams Citation2016). Recent studies have found that social capital dimensions may work together with social needs and environmental motives to motivate the uptake of environmental measures in communities (Broska Citation2021; Macias and Nelson Citation2011). Hence, social capital may supplement and enrich the more established perspective in sustainability research, where the primary focus is on individual characteristics and demographic variation.

However, an important but so far unanswered question is whether social capital, along with demographic and motivational aspects, can also be a driver of citizens’ engagement in the form of sustainable sharing. This question is important to answer since it can help understand the variety of sharing that occurs in many local communities and guide the development of policy measures to strengthen sharing practices that are most likely to promote sustainability goals. In response to this, the central research question guiding this paper is as follows: How are social capital dimensions, in combination with motivational and demographic factors, influencing sharing activities in communities, and how can this be used to inform policies to promote a wider upscaling of sharing in communities?

This paper is structured as follows: In the next section (2) we explain the key concepts of social capital and sharing practices and provide an overview of the relevant literature and findings. Four central types of local sharing practices is here outlined. In section (3), we review the methodology and data, including an introduction to the four municipalitiesFootnote1 that are the basis for the quantitative analysis. In section 4, we present the results of the analysis and then return to the research question in the last part (5) to address the dynamics between forms of sharing and social capital and the connections between “old and new” forms of sharing.

2. Theory and literature review

2.1. Social capital

Over 100 years ago, George Simmel wrote about the value of social relations and networks for developing trust and as a socialising force generated via everyday social interactions (Wolff Citation1950). Since then, multiple disciplines have adopted the idea that social relations and networks are central elements in all social life and that involvement and participation in groups can have positive consequences for the individual and the community (Portes Citation1998; Field Citation2003; Lin Citation2001). Bourdieu (Citation1983) was among the first to coin the term “social capital”, which he described as one of four types of capital, along with economic, cultural and symbolic capital, that was important for social performance and social position. In his approach, social capital is the aggregate of the actual or potential resources linked to the possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalised relationships of mutual acquaintance or recognition. Like Bourdieu, Coleman (Citation1988) saw social capital and other types of capital as a resource for the individual. In his definition, he pointed out that social capital is defined by its function. It is not a single entity but a variety of different entities with two elements in common: they all consist of some aspect of social structures, and they facilitate certain actions of actors – whether persons or corporate actors – within the structure.

Coleman’s approach to social capital overlaps with that of Bourdieu, although Coleman elaborated further on the reciprocity embedded in the system consisting of obligations and expectations. He described situations in which doing favours for someone is a type of “credit slip”. When someone receives (unpaid) help from another, they are essentially giving them a credit slip, which signifies that they will be paid back for their goods and/or services. However, for an individual to believe that their favour will be reciprocated, there also needs to be a level of trustworthiness in a social environment such that people believe the obligation will be met. Putnam (Citation2000) built on these works when warning against – and to some extent also documenting – a trend towards the gradual fragmentation of social life in the United States. Although not repudiating former works, he laid out a view of social capital that maintained a stronger focus on the role of social capital in generating benefits beyond individuals at the neighbourhood and community levels. In his broad approach, social capital includes “features of social organizations, such as networks, norms and trust that facilitate action and cooperation for mutual benefit” (35). In the regional development literature, the definitions offered by Coleman and Putnam have been most influential, particularly the latter, as it emphasises the role and influence of social capital at the community level.

However, although influential, Putnam’s work has been critiqued for having a simplified view of social capital that shadows the multifaceted nature of the concept (Poder Citation2011). Arguably, a ranking of groups and nations based on social capital indicators misses the point that there is a complex interplay of different dimensions and processes that differ across places and over time (Serageldin and Grootaert Citation2017). Moreover, his emphasis on social capital as a product of face-to-face interactions in the community has been criticised for ignoring the opportunities that new media platforms can foster for communication and other forms of mediated social capital (Rainie and Wellman Citation2012; Wellman Citation2002). Most importantly, Putnam continued Coleman’s key argument that social relations are comparable to economic investments and that human actors are developing their social networks based on rational calculations (Ishihara and Pascual Citation2009), even though many studies have documented that the build-up of social relationships and trust is often motivated by other motives and practices (Arrow Citation2000; Decker and Uslaner Citation2001; Ala-Mantila et al. Citation2009).

Partly due to the diversified theoretical landscape, there is no unified understanding of how the concept of social capital should be broken down and measured. The strategy behind most efforts to analyse social capital has been to select indicators that can capture some of the main dimensions. We follow this approach in our operationalisation and address three key dimensions: trust, social norms and social relations.Footnote2 This is aligned with the conceptual framework suggested by Brunie (Citation2009), who distinguished between relational, collective and generalised social capital. The relational form of social capital refers to the structures of social relationships that connect people within a local community and beyond. Here, two types of relations are central: bonding and bridging.Footnote3 Bonding relationships denote ties between friends and family members. In bonding relationships, there is a high degree of mutual affinity, and one may find emotional support. In contrast, bridging ties encompass people with whom one is not particularly close, typically acquaintances or people that one occasionally meets or talks to. Bridging ties are usually more diverse and a source for different types of information compared to bonding ties. As such, they are considered particularly valuable in the network literature for sharing knowledge and information in social communities (Burt Citation2005).

The collective social capital dimension refers to the level of engagement in pro-social activities in the community. Social capital is understood as a collective resource that is essentially defined in relation to its function. Reciprocity norms are particularly important because they predispose individuals to cooperate with one another and refrain from engaging in opportunistic behaviour and free riding (Ostrom Citation1990). In the realm of sharing, in some cases, reciprocity is an underlying mechanism, although not in its most altruistic forms (Belk Citation2010). Finally, the generalised type of social capital relates to individuals’ attitudes and predispositions towards others. When people have a generally trustful attitude towards others, it makes them predisposed to cooperate, trust, understand and empathise with others. In the context of sustainable development, generalised trust makes it more likely that people will engage in altruistic and non-profit activities because it builds on the idea that others are likely to replicate this. Therefore, generalised trust is sometimes seen as a predictor of engagement in environmental activism and membership in environmental organisations.

2.2. Sharing – new and old forms

Sharing is a fundamental activity for many central social mechanisms that are implicitly or explicitly part of many social theories. According to Belk (Citation2010), sharing can be described as a practice that involves “the act and process of distributing what is ours to others for their use and/or the act and process of receiving or taking something from others for our use” (126). In many ways, the concept is closely related to social capital; both put relational interactions in focus, and the duality between bridging and bonding social capital is mirrored in the distinctions between weaker and stronger forms of sharing (Belk Citation2014, Citation2010). Similarly, Tim Ingold (Citation1986) coined the twin concepts of “sharing in” and “sharing out”, where the first is the typical consumption of resources within a denser circle of people regarding ownership as common, and the latter involves giving or receiving to or from those outside the social group boundaries. Sharing is often a product and an expression of social capital, and it can simultaneously help to build or sustain it. The close association between social capital and sharing entails an inevitable recursiveness; pre-existing social capital can initiate sharing, but simultaneously, involvement in sharing practices may produce social capital. However, like most pre-existing work on social capital in the context of sustainable development, we will consider sharing as primarily an outcome of social capital in communities (Macias and Williams Citation2016; Grootaert and van Bastelaer Citation2009; Serageldin and Grootaert Citation2017).

In the literature, four types of sharing have been addressed: sharing between local friends and family members, community based sharing, time sharing and the more recent p2p haring taking place through digital platforms. Traditional sharing between family members and close friends building up reciprocity and relational trust is fundamental for developing and sustaining most social groups and communities. However, there also exists a more organised form where sharing activities are coordinated and regulated within the community. Community-based sharing includes arrangements set up to share and/or re-use items, such as sharing events, flea markets, informal sharing of cars and food cooperatives. These sharing forms tend to operate in a middle position between market-based and informal sharing schemes (Hamari, Sjöklint, and Ukkonen Citation2016; Albinsson and Perera Citation2012), and they are typically coordinated and facilitated by activists, often in cooperation with NGOs and/or public enterprises. Westskog et al. (Citation2021) defined community sharing as “organized sharing activities that involve members of a well-defined societal group and where a centralized body provides an asset or a pool of assets and governs members’ use”. Hence, compared with sharing within the close circle of family and friends, community-based sharing is more institutionalised and can help to promote what Ingold described as “sharing out”.

Contributing to community-based work voluntarily and helping others in the community with various assignments can be considered a particular form of sharing. When this is in the form of institutionalised behaviour, it links up to organised sharing, although it points to the act of “distributing” time rather than tangible goods. In previous literature, the sharing of time through voluntary work has been related to social capital, either as an outcome or an indicator (McCulloch, Mohan, and Smith Citation2012; Hanifi Citation2013; Sørensen Citation2012). According to Putnam (Citation2000), engagement in voluntary associations represents one of the main arenas for face-to-face communication that may be generative of networks and trust over time. However, a distinction should be made between volunteering work as membership in formal organisations and informal commitment to a community (Neymotin Citation2016). We will address the latter in this paper, as it more closely captures the concept of sharing.

A key theme in the literature on sharing over the last two decades has been the extent to which communication technology has influenced and changed sharing practices. Along with the rapid growth of Internet 2.0 and smartphone applications over the last decades, a range of P2P sharing platforms has been introduced that offers consumer systems that help to coordinate sharing and lending, extending the circle of possible lenders and sharers way beyond the family and local community. This has brought new attention to the idea of sharing as an alternative and more sustainable system for the distribution of goods, and applications for sharing have emerged across different consumer areas, including accommodation (Airbnb), transportation (BlaBlaCar, Zipcar), items and tools (eBay), food (Too Good To Go) and clothing (Clothing Swap). In the literature, sharing activities on the internet have been described as collaborative consumption, representing a transformed type of sharing and often seen as a cornerstone in the advent of a sharing economy (Botsman and Rogers Citation2011; Whalen Citation2018; Agarwal and Steinmetz Citation2019; Arcidiacono and Gandini Citation2019). Currently, many different business models exist, and the delimitation of different types of sharing, borrowing, bartering and market transactions is not trivial. However, one characteristic of shared consumption online (i.e. collaborative consumption) is that it usually involves some kind of compensation or fee when individual goods or services shift hands. Therefore, Belk (Citation2014, 1597) defined collaborative consumption as “people coordinating the acquisition and distribution of a resource for a fee or other compensation”. By including other compensation, this definition encompasses bartering, trading and swapping, which all involve giving and receiving non-monetary compensation. Another central aspect of most P2P platforms is the use of systems for rating and reputation scores that have made sharing with strangers less risky and more appealing (Schor Citation2016; Huurne et al. Citation2018; Kim and Yoon Citation2016). This enables sharing among a much broader set of agents than is usually the case for people’s face-to-face-based bridging and bonding ties. However, at the same time, these rating systems seem to devalue the role of social trust as an important underpinning for the functioning of social capital (Botsman Citation2017).

The idea that internet-based sharing, borrowing and renting can promote more sustainable societies has been met with much scepticism. For example, Lawrence Lessig (Citation2008) argued that while sharing has always existed, P2P sharing formalises and monetises previously informal and voluntary elements. Following Lessig’s argument, there has been an increase in both the volume and variety of “thin sharing” that is more focused on individual gain and resembles the self-interested actor model within classical economics. Lessig explained that “a thin sharing economy is often easier to support than a think sharing economy … [because] … all things being equal, a me motivation [for us, now] comes more easily to most” (Ibid, p. 155).

More recently, studies have also provided evidence that P2P-based sharing seems to be grounded on other institutional logics than traditional face-to-face-based community sharing (Julsrud and Uteng Citation2021; Bardhi and Eckhardt Citation2012; Laurell and Sandström Citation2017). There is also an ongoing debate as to whether the sharing economy is a trend that may lead to exploitative business practices that exacerbate existing inequalities rather than strengthen sustainability measures (Martin Citation2016; Gruzka Citation2017).

2.3. Social capital and local sharing

Most of the literature on local and regional development focuses on relational aspects of social capital (Aldrich and Meyer Citation2015; Kirkby-Geddes, King, and Bravington Citation2013; Kusakabe Citation2012). Well-functioning networks of weaker and stronger relationships have been recognised as important for how well communities handle disaster situations through the distribution of information, financial aid support, child care and emotional and psychological support (Wickes et al. Citation2015; Elliott, Haney, and Sams-Abiodun Citation2010; Jovita et al. Citation2019). In addition to the bridging and bonding relationship forms, there has been a growing awareness of linking relationships that connect across vertical institutions and boundaries (Agger and Jensen Citation2015). In addition, a few studies have found that social capital may be important for sharing activities such as community gardens (Kingsley, Foenander, and Bailey Citation2020; Shimpo, Wesener, and McWilliam Citation2019), food sharing (Whalen Citation2018) and the use of local libraries (Johnson Citation2012). In summary, these studies suggest that social capital can be positive for sharing activities and that different social capital types – in particular, bridging and bonding ties – may have complementary functions. However, current work has rarely included multiple social capital dimensions, and in most cases, existing studies are based on case studies of particular types of sharing activities. Likewise, there are no works that attempt to relate the new types of P2P-based sharing with different forms of traditional local sharing, leaving a blind spot on how emerging technologically mediated sharing may interact with traditional sharing forms. In this paper, we intend to fill some of these gaps by exploring how multiple social capital dimensions impact P2P and traditional sharing forms.

3. Data and methodology

As previously indicated, much earlier works have found that social capital can differ across regions, municipalities and smaller communities (Putnam Citation2000; Guzhavina and Mekhova Citation2018; Hofferth and Iceland Citation1998; Jens Fyhn Lykke Sørensen Citation2016). To capture this dimension, our study targets sharing practices among citizens in four municipalities in Norway: Tromsø, Follo, Lillestrøm and Drammen. There are different reasons for selecting these areas as our cases. First, they have all been actively supporting local sharing programmes involving both public sector partners and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).Footnote4 Second, they exhibit diversity in terms of population, size and density, making it possible to compare geographical and contextual variation (). Whereas Drammen has over 100,000 inhabitants and is relatively densely populated, Tromsø lies in the northern part of Norway with more scattered settlements. However, as indicated in the centrality index, all municipalities are centred around one larger urban region. Including different municipalities in the study allows for an understanding of the impact of place as an explanatory factor. Nevertheless, following the logic of comparative case studies, the low level of variation between communities may suggest that the impact of the context is low (Ragin Citation1987).

Table 1. Municipality profiles.

The questionnaire was distributed to a pre-recruited panel of respondents in each municipality that was balanced for genders, age groups and income.Footnote5 The total net sample included 1,313 informants who were relatively equally distributed across the four locations (). There were variations across the municipalities, with a larger share of younger people in Tromsø and slightly more respondents in high-income groups in Follo and Lillestrøm. A link to a web-based questionnaire was distributed via e-mail to the pre-recruited panel of respondents. The survey was open from 16/9/2021 to 5/10/2021.

Table 2. Age, household income (NOK) and gender (sample) – percentages.

Social capital was registered using four sets of items. As an indicator of bonding social capital, we asked respondents to indicate the number of their close friends and/or relatives who lived in the local community on a seven-point scale. For bridging ties, we asked how many acquaintances they had in the local community on a four-point scale. For generalised trust, we use the standardised five-point scale based on the World Value Survey Index (Delhey and Weltzel Citation2012) “In general, would you say that most people can be trusted, or you cannot be too careful dealing with people?” Reciprocity norms were measured through the five-point scale suggested by Kobayashi et al. (Citation2015); “Would you say that most people in your community are willing to help each other or that they mostly just look out for themselves?” Motives for sharing (environmental, social and economic) were measured on a five-point Likert scale indicating agreement with the environmental, economic or social benefits of sharing items. Finally, community belonging was coded as dummy variables, with Tromsø as a reference group in the model.

To locate and categorise sharing and borrowing/lending, we asked about engagement in various activities over the last 12 months, indicated on a five-point scale from “never” to “very often”. This included regular face-to-face events, sharing time in the local community (voluntary work), re-use arrangements and sharing coordinated through P2P applications (). A compilation of 10 items was presented to the respondents, and the most common sharing activities were buying or giving away used clothes through re-use arrangements, while the use of P2P applications for sharing was less common. These items were then reorganised into four main categories: Sharing based on digital platforms (P2P sharing), local sharing arrangements (Organised sharing), sharing of time for voluntary work (Time sharing) and informal sharing with friends and family (Informal sharing). These items were used to create scales for each of the four forms of sharing, and Cronbach’s Alpha indicates an acceptable level of reliability for each of them (>0.6). To analyse the impact of social capital dimensions and motivations on sharing forms, a multiple regression analysis was conducted, including municipality belonging and demographic variables.

Table 3. Variables indicating sharing activities.

A significant contribution from this constellation of variables is that it provides an extensive understanding of social capital, cognitive aspects and locational dimensions and, as such, goes beyond most earlier studies in this field. However, it should be noted that the scope of the study limits the indicators used to map local sharing, and a more extensive set would most likely have improved the validity of the scales. Moreover, given the broadness of the concept of sharing, there are likely several other forms of sharing occurring locally than the ones addressed in the questionnaire. Hence, the scales included should be considered indicative of central sharing forms.

4. Results

The distribution of social capital across the municipalities shows significant variation in both social capital scores and motives for sharing, although none have an exceptionally high or low score (p < 0.01; ). Follo and Tromsø display higher scores on the social capital measures than the other two municipalities. Environmental concerns are the strongest motivation for sharing in all the regions, although these are also higher in Follo and Tromsø.

Table 4. Social capital indicators and motives for sharing – mean values.

A multiple regression analysis was employed to understand the impact of social capital dimensions on all the sharing types (). Models 1–4 included P2P sharing, organised sharing, time sharing and informal sharing, respectively. For the first model, P2P sharing is predicted by bridging social capital (β = 0.20, p < 0.05), age (β = −0.225, p < 0.001) and social motives (β = 0.074, p < 0.05). As evident from Model 2, organised sharing is impacted by the relational social capital dimension, in particular, the bridging form (β = 0.109, p < 0.001) and bonding (β = 0.063, p < 0.05). Furthermore, environmental (β = 0.086, p < 0.01) and economic (β = 0.074, p < 0.05) motives work together with the social capital variables in this model. Of the demographic variables, gender (β = 0.206, p < 0.001), age (β = 0.131, p < 0.001) and income (β = 0.065, p < 0.01) explain much of the organised sharing type. This model also involves locational differences, with a higher involvement of citizens in Follo and Lillestrøm (Both β = 0.071, p < 0.05).

Table 5. Linear regression with sharing forms as dependent variables.

Engagement in time sharing (Model 3) is predicted by all social capital dimensions, particularly bridging and bonding (β = 0.23, p < 0.001 and β = 0.087, p < 0.01) but also trust and reciprocity (β = 0.066, p < 0.05 and β = 0.068, p < 0.05). Furthermore, environmental motives are a strong predictor (β = 0.093, p < 0.01), and there is a positive effect of age (β = 0.074, p < 0.01) in this model. Finally, Model 4 shows that informal sharing is significantly predicted by bridging and bonding social capital dimensions (β = 0.155, p < 0.001 and β = 0.065, p < 0.05), as well as trust (β = 0.079, p < 0.05). In addition, environmental motives positively impact informal sharing (β = 0.087, p < 0.01), and there is a minor positive effect of income (β = 0.074, p < 0.01) on informal sharing.

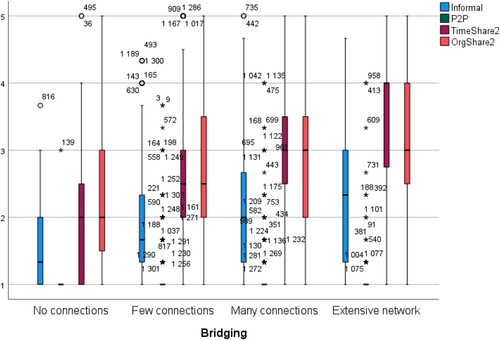

In summary, the analysis shows that even when controlling for demographic and motivational factors, all social capital dimensions are important drivers for local sharing, although they have a particularly strong effect on engagements in time sharing and informal sharing. Bridging social capital is the dimension that most strongly predicts variation in all forms of sharing, including P2P. illustrates how an increasing number of acquaintances in the local environment (bridging social capital) impact engagement in sharing activities. Overall, trust and reciprocity have a weaker impact on involvement in sharing activities, although they are active for informal and time sharing to some extent. As for the motives, environmental aspects are the most salient, influencing all forms of sharing except for P2P. Nevertheless, this sharing form is influenced by social and economic motives to some degree.

Locational factors are less important in explaining sharing, although Follo and Lillestrøm appear to have more organised sharing activities going on than the other two municipalities. The lower level of engagement in organised sharing in Tromsø may be due to the lower level of centrality and the population density in this municipality.

Regarding the demographic variables, age is a significant negative predictor for P2P engagement, while older groups are more active in organised sharing and time sharing. This provides clear evidence of a generational gap in local sharing practices. There are also important gender variations, with females significantly more active in organised sharing activities than males. Moreover, people in high-income groups tend to be involved in other sharing forms than those with lower income. The reasons for their higher involvement in organised and informal sharing may be differences in facilities in typical residential areas. Nevertheless, these findings generally refute the conception that people are engaged in sharing because they cannot afford to buy new items.

As displayed in , all forms of sharing are positively correlated, suggesting that those who are “sharers” often get involved in all sharing forms. In particular, informal and time sharing have a close relationship (r = 0.403, p < 0.01).

Table 6. Correlation between the forms of sharing.

5. Discussion and conclusions

Sharing, as a part of collaborative consumption, is believed to be beneficial for local communities (and society in general), and ICT-based applications have made this much more available and popular over the last few years. Hence, there has been a significant interest in the factors that support these activities. However, contributions have so far looked foremost at individual factors that promote particular types of sharing (Schanes and Stagl Citation2019; Echegaray and Hansstein Citation2020). In this paper, we have suggested examining local sharing as also influenced by communities’ networks of relations, trust and reciprocity norms (i.e. social capital). As shown in this paper, social capital in its different forms plays an important role in engagement in different forms of sharing locally. Thus, the findings reply to calls for more focus on contextual and cultural factors when explaining the interest and engagement in collaborative consumption (Retamal Citation2019; Mont and Plepys Citation2008; Whalen Citation2018). Moreover, while earlier works have mainly addressed singular forms of sharing, we have applied a more extensive approach here, defining four main forms of sharing. By including face-to-face and the more recent P2P form, we have elaborated on how older forms of sharing are enriched but also possibly replaced by newer P2P forms.

Regarding the research question raised, our data confirms that social capital dimensions are of high importance for all the sharing activities occurring in the municipalities. The indicators of social capital were, in different ways, predictive of engagements in informal, time-based and organised sharing forms. Nevertheless, the benefits of having a developed network of bridging relationships figure as the strongest driver for sharing, including the newer P2P form. Moreover, the analysis suggests that social capital dimensions work in concert with motivational structures, speaking to former works that have found that social capital can supplement individual norms and attitudes when explaining engagements in pro-environmental behaviour (Macias and Nelson Citation2011; Kusakabe Citation2012; Böcker and Meelen Citation2017). We found that environmental motives are most influential, even for the P2P-based form, supporting the argument that local sharing is founded on moral values and norms more than economic self-interest. In addition to social capital and individual motives, it is clear that there are important differences related to how men and women and people in different age groups get involved with local sharing. We found a generational gap related to the use of P2P sharing and organised sharing locally. Differences across the four municipalities suggest that population density and centrality may have a positive effect on certain forms of sharing.

5.1. Social capital as a driver for local sharing

What are the underlying mechanisms in play that make social capital influence sharing? Based on the results described, we suggest that there are at least three processes involved. First, social relational networks, trust and norms of reciprocity represent community-based resources that enable sharing. Social capital makes the sharing of items without safeguards possible since fraud will corrupt individuals’ trustworthiness and reputation, as elaborated by Coleman (Citation1988) and others. As for the sharing of items within closer circles and time sharing, there needs to be a certain level of general trust and reciprocity in place to enable this. These are resources that require time to develop. As we found in the analysis, bonding social capital and organised sharing were more prominent among the older groups, and this may indicate that living in the same area over time provides opportunities to forge denser relationships.

Second, social capital dimensions can help to mobilise sharing by making it more accessible and attractive. For the relational social capital dimensions, it is reasonable to assume that the existence of a wide network of acquaintances gives citizens better access to information about where (or with whom) one can share, lend and give away. The finding that bridging ties are significant for sharing aligns with the “strength of the weak tie argument”, holding that it is the weaker ties, not the stronger ones, that provide novel information in communities (Granovetter Citation1973). It is also in accordance with the concept of “structural holes”, where links between formerly weakly connected subgroups make up a core element in the development of social capital (Burt Citation2005, Citation1992). Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that the presence of pre-existing relationships will make face-to-face sharing easier than sharing between strangers. Hence, an upscaling of sharing activities in communities is more likely when there are existing networks of weaker ties. Our findings here echo adjacent studies that have found that bridging social capital can be utilised to enable community-based initiatives, that is, collective actions where citizens initiate and implement initiatives aimed at providing public goods or services for their community (Igalla, Edelenbos, and van Meerkerk Citation2020).

A third type of mechanism can be outlined in the cases of social capital-initiated synergies between different forms of sharing and social capital elements. There are good reasons to believe that there are multiple two-way interactions where social capital and sharing build up and support each other over time. For instance, engagement in time-sharing activities seems to be the type of sharing that draws on social capital the most, but this activity is also likely to build relational social capital and trust. The adjacency of the concepts suggests that they can collaborate and create positive spirals in the upscaling of local sharing. Such processes have been pointed out in previous qualitative studies of sharing events and activities (Albinsson and Perera Citation2012; Standal and Westskog Citation2022). Moreover, the strong and positive impact of environmental motives on all face-to-face forms of sharing suggests that there are common norms involved in local face-to-face sharing. One reason for this may be that involvement in sharing activities also cultivates norms and environmental practices, as well as generates social capital.

5.2. P2P – a threat to community-based sharing?

An important question that needs to be addressed is whether the fast-growing P2P sharing is destructive for social capital and sharing on a local level or whether it creates some new opportunities. On the one hand, findings indicate that P2P sharing operates in different ways than the other sharing types, being less related to the common social capital dimensions. There is a younger generation that is more actively involved in sharing on digital platforms, while older generations adhere to organised and time-sharing forms. This is consistent with previous research suggesting that collaborative consumption may vary across generations (Echegaray and Hansstein Citation2020; Mahadevan Citation2017). Even though empirical evidence has found that the level of social capital and trust remains high in Norwegian communities (Ivarsflaten and Strømsnes Citation2013), the findings here give some support to Putnam’s argument that community-based social networks are eroding (Putnam Citation2000). It may also, to some extent, indicate that “networked individualism”, which is the increasing use of web-based communication and social media, has come to dominate people’s social lives rather than local relationships (Castells et al. Citation2007; Wellman et al. Citation2003).

On the other hand, P2P sharing is still less common than the other forms of sharing addressed here. We also see that a higher level of acquaintances in the local environment bolstered engagement in P2P, suggesting that the P2P sharers do not solely relate to people outside their local community. The positive correlations that we found between P2P sharing and the other forms also indicate that this group is often involved in other forms of sharing as well. This resonates with some other studies that have shown that new forms of community-based social media platforms can provide the infrastructure that can facilitate more interaction and social capital in neighbourhoods (Kwon, Shao, and Nah Citation2021; Mossberger, Wu, and Crawford Citation2013). In the context of urban development, this also supports the growing interest in the creation of “sharing cities” where highly networked physical spaces are converging with new digital technologies to drive more sharing in cities (McLaren and Agyeman Citation2015; Finck and Ranchordas Citation2016).

5.3. Future work

This study aimed to illuminate the impact of relational, community-based qualities on multiple forms of sharing activities. In this area, we believe that the results have presented insights that pave the way for more research on the role of social capital and sharing in developing more sustainable consumer practices. In our view, the findings presented here cast new light on how sharing can contribute to environmental benefits and transformations in consumption patterns. As we have seen, sharing is a multi-dimensional concept involving both old and new forms, which may have different impacts. We also believe that this paper can add to a growing interest in the role of social network dynamics in “sharing niches” locally, putting local sharing activities in the larger framework of transition theory (deHaan and Rotmans Citation2018; Schäpke et al. Citation2017). A social capital approach offers the opportunity to further illuminate mechanisms crucial for understanding sharing practices and the premises for an upscaling of this beyond the local community level.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Monica Guillen-Royo, Nina Holmelin and members at the session “Exploring grassroots initiatives for transitions” at the Nordic Environmental Social Science Conference (NESS) in Gothenburg June 7-9, 2022, for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this paper, we use the term “community” interchangeably with “municipality”. Although these concepts are not identical, they both address an interacting group of people within a geographically bounded area. This approach finds support in a general conception within social sciences that this involves shared locality and neighbourhood, but also the idea of solidarity and connection between people who share similar characteristics or identities (Scott Citation2006, 35).

2 The Social Benchmark study includes four forms (social trust, membership in formal groups, altruism and informal interactions among individuals) as key dimensions (Rogers and Gardner Citation2012). In this paper, we exclude the element of altruism, as this dimension is rarely used in empirical works and can be difficult to separate from social norms.

3 These two types of relationships reflect the twin concepts of weak and strong ties that were initially developed by Mark Granovetter (Citation1973) in a study of jobseekers, where he found that most people obtained information about vacant positions through their weak ties (bridging) rather than their strong ones (bonding).

4 This study was conducted as part of a larger research project focusing on sharing in local communities.

5 The survey was distributed by a marketing company to its pre-existing panel of respondents. The population base is a pre-recruited sample of people over the age of 15 willing to participate in surveys (currently approx. 40,000 people). The participants were recruited randomly through other telephone (fixed and mobile) and postal surveys and constituted an active panel.

References

- Agarwal, Nivedita, and Robert Steinmetz. 2019. “Sharing Economy: A Systematic Literature Review.” International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management 16 (6): 1930002. doi:10.1142/S0219877019300027.

- Agger, Annika, and Jesper Ole Jensen. 2015. “Area-based Initiatives—and Their Work in Bonding, Bridging and Linking Social Capital.” European Planning Studies 23 (10): 2045–2061. doi:10.1080/09654313.2014.998172.

- Ala-Mantila, Sanna, Juudit Ottelin, Jukka Heinonen, and Seppo Junnila. 2017. “Reprint of: To Each Their Own? The Greenhouse Gas Impacts of Intra-Household Sharing in Different Urban Zones.” Journal of Cleaner Production 163: 579–590. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.05.156.

- Albinsson, Pia A., and B. Yasanthi Perera. 2012. “Alternative Marketplaces in the 21st Century: Building Community Through Sharing Events.” Journal of Consumer Behaviour 11: 303–315. doi:10.1002/cb.1389.

- Albinsson, Pia, B. Y. Perera, L. Nafees, and B. Burman. 2019. “Collaborative Consumption Usage in the US and India: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 27 (4): 390–412. doi:10.1080/10696679.2019.1644956.

- Aldrich, Daniel, and Michelle Meyer. 2015. “Social Capital and Community Resilience.” American Behavioral Scientist 59 (2): 254–269. doi:10.1177/0002764214550299.

- Arcidiacono, Davide, and Alessandro Gandini. 2019. “Sharing What? The ‘Sharing Economy’ in the Sociological Debate.” The Sociological Review 66: 2. doi:10.1177/0038026118758529.

- Arrow, Keneth. 2000. “Observations on Social Capital.” In Social Capital: A Multifaceted Perspective, edited by Partha Dasgupta, and Ismail Serageldin, 3–5. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Bardhi, Fleura, and Giana M. Eckhardt. 2012. “Access-Based Consumption: The Case of Car Sharing: Table 1.” Journal of Consumer Research 39: 881–898. doi:10.1086/666376.

- Belk, Russel. 2010. “Sharing: Table 1.” Journal of Consumer Research 36 (5): 715–734. doi:10.1086/612649.

- Belk, Russel. 2014. “You are What you Can Access: Sharing and Collaborative Consumption Online.” Journal of Business Research 67: 1595–1600. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.001.

- Bennett, N. J., J. Blythe, J. Tyler, and N. C. Ban. 2016. “Communities and Change in the Anthropocene: Understanding Social-Ecological Vulnerability and Planning Adaptations to Multiple Interacting Exposures.” Regional Environmental Change 16: 907–926. doi:10.1007/s10113-015-0839-5.

- Böcker, Lars, and Toon Meelen. 2017. “Sharing for People, Planet or Profit? Analysing Motivations for Intended Sharing Economy Participation.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 23: 28–39. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2016.09.004.

- Botsman, Rachel. 2017. Who Can You Trust? How Technology Brought Us Together – and Why It Could Drive Us Apart. London: Penguin Random House.

- Botsman, Rachel, and Roo Rogers. 2011. What´s Mine is Yours. How Collaborative Consumption is Changing the Way We Live. London: Collins.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1983. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J.G Richardson, 183–198. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Broska, Lisa Hanna. 2021. “It´s all About Community: On the Interplay of Social Capital, Social Needs, and Environmental Concern in Sustainable Community Actions.” Energy Research and Social Science 79: 22114–26296. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2021.102165.

- Brunie, Aurélie. 2009. “Meaningful Distinctions Within a Concept: Relational, Collective, and Generalized Social Capital.” Social Science Research 38: 251–265. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.01.005.

- Burt, Ronald. 1992. Structural Holes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Burt, Ronald. 2005. Brokerage and Closure. An Introduction to Social Capital. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Castells, Manuel, M. Fernandéz-Ardévol, J. L. Qiu, and A. Sey. 2007. Mobile Communication and Society. A Global Perspective. Cambridge, MA: The MIT press.

- Coleman, James. 1988. “Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital.” American Journal of Sociology 94: 95–120.

- Decker, Paul, and Eric M. Uslaner. 2001. Social Capital and Participation in Everyday Life. London: Routyledge.

- deHaan, Fjalar J., and Jan Rotmans. 2018. “A Proposed Theoretical Framework for Actors in Transformative Change.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 128: 275–286. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2017.12.017.

- Delhey, Jan, and Christian Weltzel. 2012. “Generalizing Trust. How Outgroup-Trust Grows Beyond Ingroup-Trust.” World Values Research 5 (3): 46–69. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2390636.

- Dubois, Ghislain, Benjamin Sovacool, Carlo Aall, Maria Nilsson, Carine Barbier, Alina Herrmann, Sébastien Bruyère, et al. 2019. “It Starts at Home? Climate Policies Targeting Household Consumption and Behavioral Decisions are Key to Low-Carbon Futures.” Energy Research & Social Science 52: 144–158. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.02.001.

- Echegaray, Fabian, and Francesca Hansstein. 2020. “Share a Ride, Rent a Tool, Swap Used Goods, Change the World? Motivations to Engage in Collaborative Consumption in Brazil.” Local Environment 25: 891–906. doi:10.1080/13549839.2020.1845132.

- Elliott, James R., Timothy J. Haney, and Petrice Sams-Abiodun. 2010. “Limits to Social Capital: Comparing Network Assistance in Two New Orleans Neighborhoods Devastated by Hurricane Katrina.” The Sociological Quarterly 51 (4): 624–648. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2010.01186.x.

- Field, John. 2003. Social Capital. Edited by Routledge, Key ideas. London.

- Finck, Michele, and Sofia Ranchordas. 2016. “Sharing and the City.” Vanderbilt Journal of Transnsnational Law 49 (5): 1299–1370.

- Granovetter, Mark S. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 81: 1287–1303.

- Grootaert, Christiaan, and Thierry van Bastelaer. 2009. The Role of Social Capital in Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gruzka, K. 2017. “Framing the Collaborative Economy —Voices of Contestation.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 23: 92–104. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2016.09.002.

- Guzhavina, Tatiana А., and Albina А. Mekhova. 2018. “Social Capital: A Factor in Region’s Sustainable Development.” European Journal of Sustainable Development 7 (3): 483–492. doi:10.14207/ejsd.2018.v7n3p483.

- Hamari, Juho, Mimmi Sjöklint, and A. Ukkonen. 2016. “The Sharing Economy: Why People Participate in Collaborative Consumption.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 67 (9): 2047–2059. doi:10.1002/asi.23552.

- Hanifi, Riitta. 2013. “Voluntary Work, Informal Help and Trust: Changes in Finland.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 72: 32–46. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.02.004.

- Hargreaves, Tom, Sabine Hielscher, Gill Seyfang, and Andrian Smith. 2013. “Grassroots Innovations in Community Energy: The Role of Intermediaries in Niche Development.” Global Environmental Change 23: 868–880. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.02.008.

- Hertwich, Edgar G., and Glen Peters. 2009. “Carbon Footprint of Nations: A Global, Trade-Linked Analysis.” Environmental Science & Technology 43 (16): 6414–6420. doi:10.1021/es803496a.

- Hofferth, Sandra L, and John Iceland. 1998. “Social Capital in Rural and Urban Communities.” Rural Sociology 63 (4): 574–598. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.1998.tb00693.x.

- Huurne, Maarten ter, Amber Ronteltap, Chenhui Guo, Rense Corten, and Vincents Buskens. 2018. “Reputation Effects in Socially Driven Sharing Economy Transactions.” Sustainability 10: 2674. doi:10.3390/su10082674.

- Igalla, Malika, Jurian Edelenbos, and Ingmar van Meerkerk. 2020. “What Explains the Performance of Community-Based Initiatives? Testing the Impact of Leadership, Social Capital, Organizational Capacity, and Government Support.” Public Management Review 22 (4): 602–632. doi:10.1080/14719037.2019.1604796.

- Ingold, Tim. 1986. The Appropriation of Nature. Essays on Human Ecology and Social Relations. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Ishihara, Hiroe, and Unai Pascual. 2009. “Social Capital in Community Level Environmental Governance: A Critique.” Ecological Economics 68 (5): 1549–1562. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.11.003.

- Ivanova, Diana, Konstantin Stadler, and Kjartan Steen-Olsen. 2016. “Environmental Impact Assessment of Household Consumption.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 20: 3. doi:10.1111/jiec.12371.

- Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth, and Kristin Strømsnes. 2013. “Inequality, Diversity and Social Trust in Norwegian Communities.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties 23 (3): 322–342. doi:10.1080/17457289.2013.808643.

- Johnson, Cataherine A. 2012. “How do Public Libraries Create Social Capital? An Analysis of Interactions Between Library Staff and Patrons.” Library & Information Science Research 34 (1): 52–62. doi:10.1016/j.lisr.2011.07.009.

- Jovita, Hazel D., Haedar Nashir, Dyah Mutiarin, Yasmira Moner, and Achmad Nurmandi. 2019. “Social Capital and Disasters: How Does Social Capital Shape Post-Disaster Conditions in the Philippines?” Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 29 (4): 519–534. doi:10.1080/10911359.2018.1556143.

- Julsrud, Tom E., and Tanu Priya Uteng. 2021. “Trust and Sharing in Online Environments: A Comparative Study of Different Groups of Norwegian Car Sharers.” Sustainability 13: 4170. doi:10.3390/su13084170.

- Jung, Jiyeon, and Yoonmo Koo. 2018. “Analyzing the Effects of Car Sharing Services on the Reduction of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions.” Sustainability 10: 539. doi:10.3390/su10020539.

- Kalkbrenner, B. J., and J. Roseen. 2016. “Citizens’ Willingness to Participate in Local Renewable Energy Projects: The Role of Community and Trust in Germany.” Energy Research & Social Science 13: 60–70. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2015.12.006.

- Kim, Svetlana, and YongIk Yoon. 2016. “Recommendation System for Sharing Economy Based on Multidimensional Trust Model.” Multimedia Tools and Applications 75: 15297–15310. doi:10.1007/s11042-014-2384-5.

- Kingsley, Jonathan, Emily Foenander, and Aisling Bailey. 2020. ““It’s About Community”: Exploring Social Capital in Community Gardens Across Melbourne, Australia.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 49: 126640. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126640.

- Kirkby-Geddes, Emma, Nigel King, and Alison Bravington. 2013. “Social Capital and Community Group Participation: Examining ‘Bridging’ and ‘Bonding’ in the Context of a Healthy Living Centre in the UK.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 23: 271–285. doi:10.1002/casp.2118.

- Kobayashi, Tomoko, Etsuji Suzuki, Masayuki Noguchi, Ichiro Kawachi, and Soshi Takao. 2015. “Correction: Community-Level Social Capital and Psychological Distress among the Elderly in Japan: A Population-Based Study.” PLOS ONE 10: e0144683. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144683.

- Kusakabe, Emiko. 2012. “Social Capital Networks for Achieving Sustainable Development.” Local Environment 17 (10): 1043–1062. doi:10.1080/13549839.2012.714756.

- Kwon, K. Hazel, Chun Shao, and Seungahn Nah. 2021. “A Tale of Two Cybers – How Threat Reporting by Cybersecurity Firms Systematically Underrepresents Threats to Civil Society.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 18: 1. doi:10.1080/19331681.2020.1776658.

- Laurell, Christofer, and Christian Sandström. 2017. “The Sharing Economy in Social Media: Analyzing Tensions Between Market and Non-Market Logics.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 125: 58–65. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2017.05.038.

- Lessig, Lawrence. 2008. Remix: Making art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. New York: Penguin Press.

- Lin, Nan. 2001. Social Capital. A Theory of Social Structure and Action, Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Macias, Thomas, and Elysia Nelson. 2011. “A Social Capital Basis for Environmental Concern: Evidence from Northern New England*.” Rural Sociology 76 (4): 562–581. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.2011.00063.x.

- Macias, Thomas, and Kristin Williams. 2016. “Know Your Neighbors, Save the Planet. Social Capital and the Wideing Wedge of Pro-Environmental Outcomes.” Environment and Behavior 48 (3): 391–420. doi:10.1177/0013916514540458.

- Mahadevan, R. 2017. “Strangers in Spare Beds: Case Study of the International and Domestic Demand in Australia’s Peerto-Peer Accommodation Sector.” Journal of Tourism and Hospitality 6 (100029): 2167–0269. doi:10.4172/2167-0269.1000297.

- Martellozzo, Federico, David M. Landholm, and Anne Holsten. 2019. “Upscaling from the Grassroots: Potential Aggregate Carbon Reduction from Community-Based Initiatives in Europe.” Regional Environmental Change 19: 953–966. doi:10.1007/s10113-019-01469-9.

- Martin, Chris J. 2016. “The Sharing Economy: A Pathway to Sustainability or a Nightmarish Form of Neoliberal Capitalism?” Ecological Economics 121: 149–159. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.11.027.

- McCulloch, Andrew, John Mohan, and Peter Smith. 2012. “Patterns of Social Capital, Voluntary Activity, and Area Deprivation in England.” Environment and Planning A 44: 1130–1147. doi:10.1068/a44274.

- McLaren, Duncan, and Julian Agyeman. 2015. Sharing Cities: A Case for Truly Smart and Sustainable Cities, Envonment Magazine. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Mi, Zhifu, and D’Maris Coffman. 2019. “The Sharing Economy Promotes Sustainable Societies.” Nature Communications 10 (1): 1214. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09260-4.

- Mont, Oksana, and Andrius Plepys. 2008. “Sustainable Consumption Progress: Should we be Proud or Alarmed?” Journal of Cleaner Production 16 (4): 531–537. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2007.01.009.

- Mossberger, K., Y. Wu, and J. Crawford. 2013. “Connecting Citizens and Local Governments? Social Media and Interactivity in Major U.S. Cities.” Government Information Quarterly 30 (4): 351–358. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2013.05.016.

- Neymotin, Florence. 2016. “Individuals and Communities: The Importance of Neighbors Volunteering.” Journal of Labor Research 37: 149–178. doi:10.1007/s12122-016-9225-4.

- Oliveira, Tiago, Shailendra Tomar, and Carlos Tam. 2020. “Evaluating Collaborative Consumption Platforms from a Consumer Perspective.” Journal of Cleaner Production 273: 123018. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123018.

- Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Poder, Thomas G. 2011. “What is Really Social Capital? A Critical Review.” The American Sociologist 42: 341–367. doi:10.1007/s12108-011-9136-z.

- Portes, Alejandro. 1998. “Social Capital. Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology.” Annual Reviews in Sociology 24: 1–24. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1.

- Putnam, Robert. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon Schuster.

- Ragin, Charles. 1987. The Comparative Method. Moving Beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies. CA: University of California Press.

- Rainie, L., and B. Wellman. 2012. Networked: The New Social Operating System. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Retamal, Monique. 2019. “Collaborative Consumption Practices in Southeast Asian Cities: Prospects for Growth and Sustainability.” Journal of Cleaner Production 222: 143–152. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.267.

- Rogers, S. H., and K. H. Gardner. 2012. “Measuring Social Capital at the Neighborhood Scale Through a Community Based Framework.” In Social Capital at the Community Level: An Applied Interdisciplinary Perspective, edited by J. M. Halstead, and S. C. Deller. New York: Routledge.

- Sandin, Gustav, and Greg M. Peters. 2018. “Environmental Impact of Textile Reuse and Recycling – A Review.” Journal of Cleaner Production 184: 353–365. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.266.

- Schanes, Karin, and Sigrid Stagl. 2019. “Food Waste Fighters: What Motivates People to Engage in Food Sharing?” Journal of Cleaner Production 211: 1491–1501. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.162.

- Schäpke, Niko, Ines Omann, Julia M. Wittmayer, Frank van Steenbergen, and Mirijam Mock. 2017. “Linking Transitions to Sustainability: A Study of the Societal Effects of Transition Management.” Sustainability 9 (5): 737. doi:10.3390/su9050737.

- Schor, Juliet. 2016. “Debating the Sharing Economy.” Journal of Self-Governance & Management Economics 4: 3.

- Scott, John. 2006. Sociology. The Key Concepts, Key Guides. London: Routledge.

- Serageldin, Ismail, and Christiaan Grootaert. 2017. “Defining Social Capital: An Integrating View.” In Evaluation and Development, edited by Partha Dasgupta, 201–217. London: Routledge.

- Seyfang, G., and N. Longhurst. 2013. “Desperately Seeking Niches: Grassroots Innovations and Niche Development in the Community Currency Field.” Global Environmental Change 23 (5): 881–891. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.02.007.

- Seyfang, G., and A. Smith. 2007. “Grassroots Innovations for Sustainable Development: Towards a new Research and Policy Agenda.” Environmental Politics 16: 584–603. doi:10.1080/09644010701419121.

- Shimpo, Naomi, Andreas Wesener, and Wendy McWilliam. 2019. “How Community Gardens may Contribute to Community Resilience Following an Earthquake.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 38: 124–132. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2018.12.002.

- Smith, Adrian, Tom Hargreaves, Sabine Hielscher, Mari Martiskainen, and Gil Seyfang. 2016. “Making the Most of Community Energies: Three Perspectives on Grassroots Innovation.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48 (2): 407–432. doi:10.1177/0308518X15597908.

- Sonderskov, K. M. 2008. “Environmental Group Membership, Collective Action and Generalised Trust.” Environmental Politics 17: 78–94. doi:10.1080/09644010701811673.

- Sørensen, Jens F. L. 2012. “Testing the Hypothesis of Higher Social Capital in Rural Areas: The Case of Denmark.” Regional Studies 46 (7): 873–891. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.669471.

- Sørensen, Jens Fyhn Lykke. 2016. “Rural–Urban Differences in Bonding and Bridging Social Capital.” Regional Studies 50 (3): 391–410. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.918945.

- Standal, Karina, and Hege Westskog. 2022. “Understanding low-Carbon Food Consumption Transformation Through Social Practice Theory: The Case of Community Supported Agriculture in Norway.” International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food 28 (1): 7–23. https://hdl.handle.net/11250/2997942.

- Wellman, Barry. 2002. “Little Boxes, Glocalization, and Networked Individualism?” In Digital Cities II: Computational and Sociological Approaches, edited by Makoto Tanabe, Peter van den Besselaar, and Toru Ishida, 10–25. Berlin: Springer.

- Wellman, Barry, Anabel Quan-Haase, Jeffrey Boase, Whenhong Chen, Keith Hampton, Isabel Isla de Diaz, and Kakuko Miyata. 2003. “The Social Affordances of the Internet for Networked Individualism.” Journal of Computer Mediated Communication 8 (3). doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2003.tb00216.x.

- Westskog, Hege, Tom Erik Julsrud, Steffen Kallbekken, and Karina Standal. 2021. “The Role of Community Sharing in Sustainability Transformation: Case Studies from Norway.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 334–348. doi:10.1080/15487733.2021.1969820.

- Whalen, Stefan. 2018. ““Foodsharing”: Reflecting on Individualized Collective Action in a Collaborative Consumption Community Organisation.” In Contemporary Collaborative Consumption, edited by Isabel Cruz, Rafaela Ganga, and Stefan Whalen, 57–76. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Wickes, Rebecca, Renee Zahnow, Jonatghan Corcoran, and Anthony Impton. 2015. “Neighborhood Structure, Social Capital, and Community Resilience: Longitudinal Evidence from the 2011 Brisbane Flood Disaster*.” Social Science Quarterly 96 (2): 330–353. doi:10.1111/ssqu.12144.

- Wolff, Kurt H. 1950. The Sociology of Georg Simmel. New York: The Free Press.