ABSTRACT

In Australia, community gardens (CGs) commonly take the form of communally-operated growing spaces situated on public land administered by local governments (LGs). LGs and their policies are gatekeepers for CGs, and their support can determine garden viability; however, evidence regarding the nature of “support” in this context is limited. This research identified CG policies through the websites of all LGs (n = 207) in New South Wales (NSW) and Victoria, Australia and analysed these policies to describe which LGs have a CG policy, the aims of LGs’ support, the departments responsible for CGs, and what practical supports LGs provide. Thirty-nine CG policies were analysed. Most commonly, policies existed to provide a standardised framework for how LG would facilitate community groups to establish and manage CGs, and to define the roles and responsibilities of LG and community groups. Departments responsible for CG policy implementation were categorised as Community, Environment and Infrastructure, Planning, and/or Strategic and Corporate. Overall, LGs took a “hands-off” facilitator role, rather than one of an implementation partner. Common supports during application and establishment included LG arranging a licence agreement for leasing the land, assisting with site identification, and helping groups with the application process. During the garden maintenance phase, the most common supports were providing platforms for networking between CGs, providing education and information, assisting groups to apply for grants, and providing in-kind support. Recommendations for LGs, community members, and other levels of government are provided.

Key Policy Highlights

Currently, the nature of support provided by Australian local governments to community gardens is variable and largely limited to a “facilitator” role.

Local government support could be strengthened by producing clear and comprehensive policies, reducing bureaucratic red tape, and institutionalising processes that preserve public land for food production.

All levels of government can allocate ongoing funding for edible gardens at community level.

Introduction

For much of Australia’s population, availability of and access to food is a taken-for-granted component of their lives – notwithstanding the estimated pre-COVID-19 4-13% of the total population and 22–32% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who experience food insecurityFootnote1 (Bowden Citation2020). However, the recent cascade of disasters – the Australian Black Summer bushfires of 2019–2020, COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine war, and extreme flooding on the Australian east coast in 2022–2023 – has thrown into stark relief many of the problems associated with the current globalised, industrial, and productivist food system (Mehrabi et al. Citation2022; Parker and Johnson Citation2019). This system – where local production by smaller-scale producers has been overshadowed by an increasing concentration of power among fewer transnational agribusiness corporations, an emphasis on efficiency and productivity through mechanisation, use of synthetic fertilisers and new technologies, long supply chains, and an oligopolistic food retail sector in countries such as Australia (Bakhtiari Citation2021; Hendrickson Citation2015; Lapping Citation2004) – contributes to various health, social, environmental and economic problems such as food insecurity and malnutrition (both over- and under-nutrition) (Kent et al. Citation2020; Swinburn et al. Citation2019), climate change and biodiversity loss (Lawrence, Richards, and Lyons Citation2013; Springmann et al. Citation2018), viability of small-scale farming (James Citation2016), corporate concentration and inequity, and labour exploitation (Clapp Citation2021).

Alternative models of food production and distribution – including characteristics such as a moral (rather than market) economic focus, greater diversity of both producers and crops, concern for human rights and community wellbeing over corporate profits, more proximal supply chains, and ecosystems-based forms of production (Hinrichs Citation2003) – have long existed, both preceding and continuing alongside the growth of the industrial system (Davila and Dyball Citation2015; Lyons et al. Citation2013; Pudup Citation2008). The abovementioned disasters have exemplified the risks of proceeding with “business as usual”, and highlighted the benefits of local forms of food production – including home and community gardens (CGs), small-scale agriculture, and urban agriculture – and non-market models, such as sharing/trading, community-supported agriculture, and cooperatives (Nemes et al. Citation2021).

CGs, characterised by the non-commercial production of food (and flowers) by a group of community members in public open spaces in a way that shares resources and responsibilities (Mintz and McManus Citation2014), are a subset of urban agriculture – an industry located within and on the periphery of urban areas that produces edible food and ecological services using resources largely found within that urban area, and predominantly supplying products and services back into that same area (Mougeot Citation2000). CGs are a source of fresh local food, and contribute to social connection and community cohesion, physical activity, mental wellbeing, environmental education and regeneration, information sharing, increased property value for nearby land and housing, and other benefits (Bailey and Kingsley Citation2020; Guitart, Pickering, and Byrne Citation2012; Mintz and McManus Citation2014; Music et al. Citation2021). However, evidence of their ability to meaningfully address food insecurity, and matters of the right to food, equity and justice are inconsistent or limited (Barron Citation2017; Butterfield and Ramírez Citation2021; Malberg Dyg, Christensen, and Peterson Citation2019; Raneng, Howes, and Pickering Citation2022; Shisanya and Hendriks Citation2011; Wang, Qiu, and Swallow Citation2014).

CGs exist in various forms and are located in different settings. Mintz and McManus (Citation2014) identified five common forms of CGs in Australia: gardens with shared areas and individual allotments; communally managed gardens occupying one space; verge (nature strip) gardens; school kitchen gardens open to members outside of the school community; and CGs located within public housing estates reserved for use by those residents. The focus of this paper is on the first two types: gardens operated by community groups on public land for which local governments (LGs) hold administrative responsibility. The research does not explore the latter three forms, nor commercial forms of urban/peri-urban agriculture (such as market gardens) or food growing initiatives led by LG taking place on public land (e.g. urban greening initiatives where edible plants are grown).

In Australia, state government planning schemes set out the frameworks for how LGs execute land allocation and use at the local level, including most public land (Abelson Citation2022; Spencer Citation2014). This places LGs in the position of being gatekeepers to the establishment and maintenance of CGs run by groups of residents on public land. Gatekeepers are those people, organisations or institutions that, through relational power dynamics, control access by others to a given resource, item, or opportunity (Carpenter Citation2010). In this context, gatekeeping is characterised by bureaucratic processes and systems (including delays in application and approval processes) (Mulholland Citation2022; Perera, Moglia, and Glackin Citation2023) that CG groups must negotiate and overcome in order to receive permission to establish a CG. LGs hold the power – in relation to local residents – to make service delivery decisions that are perceived as fair, consistent and predictable (Mattson Citation1989).

Gatekeeping of land for CGs occurs within the context of competing demands for land, including for residential or commercial development, and also for various community interests such as sport and recreation (Thornton Citation2017; Wesener et al. Citation2020). LGs may be resistant to CGs or other urban agriculture projects for reasons such as community pressure for the land to be reserved for other uses, or perceptions that growing of edible foods is hazardous or difficult for LG to manage or that CGs are untidy and unaesthetic (Harris Citation2009; Jermé and Wakefield Citation2013; Wesener et al. Citation2020). Other LGs, as this paper shows, do have policies that promote and facilitate the establishment of CGs.

Community members face numerous practical, financial, and regulatory challenges in establishing and maintaining CGs. Groups must find suitable land (including biophysical and technical aspects such as soil condition, drainage, visibility, and size), negotiate lengthy approvals processes, secure land tenure, moderate potential opposition from neighbouring landholders and residents, acquire start-up and ongoing funding, and obtain insurance and incorporation (Guitart, Pickering, and Byrne Citation2012; Kingsley, Foenander, and Bailey Citation2019; Mintz and McManus Citation2014; Pires Citation2011; Wesener et al. Citation2020). Group members may be passionate about and have the requisite skills to grow food, but may not have experience navigating the administrative requirements, completing grant applications, and other associated tasks. LGs play an important role in assisting community groups to overcome these challenges (Jermé and Wakefield Citation2013), as well as providing access to land (Kirby et al. Citation2020; Mintz and McManus Citation2014).

Australian CG policy analysis literature is now relatively dated, and is limited in geographic scope (i.e. metropolitan/urban LGs only) (Mintz and McManus Citation2014; Pires Citation2011). The present research provides a contemporary (2022) analysis of the CG policies available from the sample of all LGs in both metropolitan and non-metropolitan NSW and Victoria, Australia’s two most populous states. Pires’ (Citation2011, 6) work identified Australian LGs as an “‘enabler’, ‘facilitator’, or ‘supporter’” of CGs, whereby they provided advice, training and other support, but no or negligible financial assistance, thus placing the onus on community members to establish and maintain CGs.

Case studies of the initiation of CGs in New Zealand and Germany revealed some CGs are established from the bottom-up with political and/or administrative support (such as that given by LGs) alongside five other types of governance structures: (1) Top-down – managed by external professionals; (2) Top-down with community help – external professionals plan and manage the garden, while paid and volunteer workers have little influence in the overall project; (3) Bottom-up with professional help – community members establish and manage the garden with help from an external professional; (4) Bottom-up with informal help – community initiation with unpaid and unstructured help from a professional; and (5) Bottom-up – garden establishment and management conducted by community members (Fox-Kämper et al. Citation2018). In the bottom-up with political and/or administrative support cases, the types of support provided by LGs included land tenure, financial and material resources, in-kind support, and information and advice.

The purpose of this paper was to operationalise the term “support” in the context of Australian CGs and the involvement of LGs. Specifically, the aims were to determine: which LGs are “supportive” of CGs (i.e. which LGs have a CG policy); what LGs aim to achieve through their support; who, within LG, is accountable for providing support; and what practical supports are provided by LGs to CGs.

Methods

The present study explores a subset of 2,266 policies included in an earlier project exploring the role of Australian LGs and civil society organisations in food system governance (Carrad, Aguirre-Bielschowsky, Reeve, et al. Citation2022) by analysing CG policies from LGs in NSW and Victoria. The search for CG policies was refreshed in August-September 2022 to: (1) confirm whether policies collected in 2019–2020 were still current; (2) update policies from those previously collected, if they had been reviewed/renewed; and (3) capture any additional policies that had been developed or made available since the earlier search. Policies were sought by: (1) searching the policy directory on each LG’s website; (2) searching for “community garden” in the search function of the website, if available; and (3) searching for the LG name and “community garden policy” in Google (e.g. “Melbourne community garden policy”). Current policies were included in the analysis; draft CG policies, and other document types such as guidelines, user agreement templates, and verge gardening policies/guidelines were excluded.

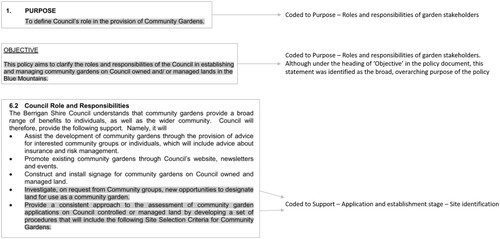

Basic descriptive statistics were conducted on the number of CG policies, and their state and region status. Purpose and objective statements were analysed thematically in NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd. Citation2018). Broad statements were coded as purpose statements, and sub-themes were inductively identified within these. Similarly, more specific statements were coded as objectives, and sub-themes inductively identified. LG departments or units responsible for CG policy implementation, as stated in the policy, were noted. These were checked against the organisational structure available on each LG’s website to identify the department/directorate level (i.e. lower divisions or units were traced back to their overarching department), then departments were grouped into broad categories. Types of support were analysed thematically: firstly, designated as either support during the application and establishment phase, the maintenance phase, or other; and then sub-themes were inductively identified within each of these three categories. See for examples of LG policy excerpts and coding.

Results

Number of CG policies

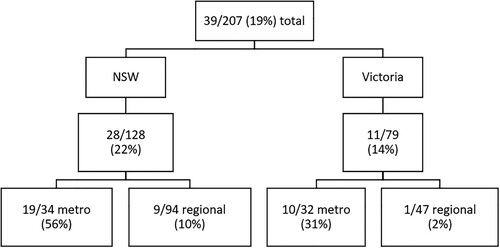

At the time of the initial study in 2019–2020, 34 CG policies were published and available on LGs’ websites across the two states (Carrad, Aguirre-Bielschowsky, Reeve, et al. Citation2022). Thirty-nine LGs (28 from NSW and 11 from Victoria) had a CG policy that was included in the final sample following the search in 2022 ().

Figure 2. Summary of the number of community garden policies from all New South Wales (NSW) and Victorian local governments (LGs), by state, and by geographical classification. Percentages are displayed as the proportion of the number of LGs with a policy from that division of the sample, i.e. n = 28 NSW LGs is equivalent to 22% of all (128) NSW LGs (not of the total sample); n = 19 metropolitan NSW LGs is equivalent to 56% of the 34 metropolitan LGs in NSW.

Purpose and objectives of the policies

There were two common primary purpose statements within CG policies:

Provide a standardised framework/processes/procedures for how LG will facilitate community groups to establish and manage CGs (n = 26 policies); and

Define roles and responsibilities of LG, community groups, and volunteers regarding the establishment, support, and ongoing management of CGs (n = 21 policies).

Other overarching purpose statements included: promoting/encouraging the development of CGs (n = 13 policies); describing the nature of support available from LG to CGs (n = 10 policies); and setting out the requirements for establishing a CG (n = 5 policies). Seven policies did not have a broad purpose statement.

Policies also included specific objectives that reflected what LGs aspired to achieve through CGs in their jurisdiction. Objectives included:

Having CG committees that are self-managed, either through the committee’s own inherent capacities, or through providing some assistance (e.g. a management framework) for committees to become so;

Promoting sustainable gardening practices. Some policies stated the LG’s preference for adoption of organic, chemical-free, and/or permaculture principles by CGs;

Enabling access to fresh and affordable local produce; contributing to food security;

Creating learning opportunities;

Encouraging gardens that are socially inclusive, open, and welcoming;

Managing complementary and competing uses for open space;

Increasing the number of CGs;

Building a strong network of CGs;

Building a connected community;

Providing recreation use of open space; and

Preventing damage to Council assets.

Policies from some LGs included content that was unique among the sample. The City of Sydney (metropolitan NSW) aimed to ensure there is potential for a CG within one kilometre (a 15-minute walk) of the dwellings of most city residents. Shoalhaven City Council (non-metropolitan NSW) was explicit that CGs should embrace the philosophy of permaculture in a community supported setting. Their policy stated, “Ideally, a garden should aim to imitate nature in its diversity and provide a wide range of non-commercial plant produce in a context that also assists with the rehabilitation of soils, habitat, and water quality”.

Greater Dandenong (metropolitan Victoria) demonstrated how their policy was consistent with various legislative structures, including: (1) the Charter of Human Rights Act 2006 (Vic) (rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association, and opportunity to take part in public life); (2) the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) (CG organisations required to pursue gender equality and ensure that their membership structures are accessible and inclusive for all); and (3) the LG’s Climate Change Emergency Strategy 2020–2030 and requirements of the Local Government Act 2020 (Vic) in relation to the overarching governance principle on climate change and sustainability (e.g. sustainable gardening, reducing waste and packaging, reducing food miles, resilience to climate change). Some, such as the City of Melbourne (metropolitan Victoria), were explicit about principles of inclusion and equitable access to both the garden itself, and also its committee of management.

The definitions of CGs in two policies (Mornington Peninsula, metropolitan Victoria; Northern Beaches, metropolitan NSW) specifically included “bush tucker” gardens. Bush tucker refers to native Australian plants that are used by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as food and medicinal sources. Nearly all policies described the benefits of CGs (e.g. growing food, social connection, environmental benefits); however, Whittlesea’s (metropolitan Victoria) policy was unique in that it also recognised CGs as spaces that allowed for “art, celebration and solitude”.

There was large variety in the departments responsible for overseeing the implementation of CG policies, as shown in , potentially stemming from the variable nature of LGs’ governance and organisational structures and differences in the names of departments conducting similar programmes of work. Departments were broadly grouped into “Community”, “Environment and Infrastructure”, “Planning”, and “Strategic and Corporate”. Nine policies did not specify a department responsible for policy implementation.

Table 1. Local government departments involved in/responsible for community garden policy implementation.

Types of support

The following section reports on the types of support given by LGs to CGs, as stated in their policies, structured into: (1) garden application and establishment phase; (2) garden maintenance phase; and (3) other supports. Overall, LG policies tended to describe a “hands-off” approach to CGs, with the role of LG being a facilitator rather than an implementation partner. For example, “Being community-led, community gardens involve minimal Council management, support or intervention” (Inner West, metropolitan NSW).

Supports during garden application and establishment phase

The most commonly stated forms of support to CG committees during the application and establishment phase were:

Providing a licence agreement (lease) for the use of public land (n = 30 policies, 77%). Many LGs provided a 12-month trial licence, which could be extended upon review at the end of the initial period;

Assisting with site identification (n = 29, 74%). The majority of policies described a reactive process whereby LG would assist a CG committee once the group had expressed interest to the LG; and

Providing an application form and assistance with the application process (n = 28, 72%).

Less common (between 30–40% of policies) supports in the establishment phase included:

Providing advice regarding development applications;

Facilitating community engagement processes to explore potential support for and opposition to a CG on a specific site;

Providing grant or budget funding from LG resources;

Assisting the garden committee to seek and apply for external funding; and

Providing in-kind support (e.g. materials, mulch, and signage).

Fewer LGs stated that they would assist the community group to establish their management committee (including providing advice regarding insurance, incorporation, risk management, committee policies, and plans of management); support composting system set-up; or provide advice on garden design.

Unique forms of support for CGs regarding designation of sites included: integration of CGs into new residential developments (Clarence Valley, non-metropolitan NSW); recommending establishment of new CGs as part of park upgrades and developments (Sydney, metropolitan NSW; North Sydney, metropolitan NSW; Port Phillip, metropolitan Victoria); and proactively identifying/endorsing sites for CGs prior to community request (e.g. Maitland, non-metropolitan NSW).

Supports during garden maintenance phase

Overall, the number of policies describing a particular form of support from LG to the garden group during the maintenance phase was much lower than the establishment phase. The most common form of support during maintenance was providing platforms for networking between gardeners and groups (n = 14, 36%). LGs also provided education and information (e.g. environmental sustainability information and workshops) (n = 13, 33%); assistance seeking and applying for external grants (n = 11, 28%); and in-kind support. Less common was support with conflict resolution (both between garden members, and between the garden and external community members); “building capacity”, broadly; and monitoring asset maintenance.

Other supports

Around half of the policies (n = 20, 51%) stated the LG would promote individual existing CGs through the LG’s website, networks, publications, events and other communication media. Some LGs would more broadly raise awareness among the general public of the concept and benefits of community gardening.

One LG provided the garden group with free/reduced cost access to community venues (Inner West, metropolitan NSW). Few policies stated the LG would link residents to existing gardens in preference to establishing new gardens (n = 3, 8%); conduct evaluation and reporting (n = 2, 5%) (measure benefits of community gardens to the community by tracking the satisfaction of community gardeners (Sydney, metropolitan NSW); measure success of the policy based on the number of new CGs in the LG area and results of a biennial survey of CG organisations (Dandenong, metropolitan Victoria)); inform “disadvantaged” and “vulnerable” groups of opportunities to be involved, including providing gardens that can accommodate the needs of people with disabilities (n = 1, 2%); or broker partnerships between garden groups and other community organisations (n = 3, 8%).

Discussion

Australian LGs, as the administrators of public land, are the gatekeepers to CGs. Their policy position can thus enable or constrain the establishment and maintenance of CGs by community members. This paper analysed available CG policies (n = 39, 19% of total 207 LGs) from all LGs in NSW and Victoria to operationalise the meaning of “support” in the context of CGs. A greater proportion of NSW LGs (22% of all NSW LGs) had a policy supporting CGs on their website than did Victorian LGs (14% of all Victorian LGs), and CG policies were more common among metropolitan than non-metropolitan LGs. The proportion of LGs from metropolitan NSW (56% of all NSW metropolitan LGs) and Victoria (31% of all Victorian metropolitan LGs) with a CG policy in 2022 was higher than in earlier studies conducted by Pires (Citation2011) (26% of metropolitan NSW LGs, and 6% of metropolitan Victoria) and Mintz and McManus (Citation2014) (35% of metropolitan NSW). The difference in the existence of CG policies between metropolitan and non-metropolitan LGs could relate to differences in the land space available in the different geographic regions. Land for growing food in urban settings is rarer due to higher density of housing, buildings and infrastructure, and lack of access to private yard space for growing food (particularly among apartment dwellers) (Evers and Hodgson Citation2011; Mintz and McManus Citation2014; Music et al. Citation2021; Thompson, Corkery, and Judd Citation2007). As part of LGs’ land-use planning responsibilities, those in metropolitan areas and regional cities thus play a significant role in protecting public land from development, preserving green space, and allocating it for community uses, such as CGs (Bailey and Kingsley Citation2020; Evers and Hodgson Citation2011; Harris Citation2009). Given the competing demands for green space in metropolitan areas (and to a lesser extent, regional cities), a CG policy can provide clarity on LGs’ expectations or objectives regarding use of public land. In contrast, people residing in lower density non-metropolitan areas are likely to have a larger amount of private land on which they could grow their own food, rendering CGs for food production purposes – although, acknowledging that the benefits of CGs extend beyond food production alone – less relevant for non-metropolitan areas.

In itself, having a CG policy signals that LG has a particular stance on the issue. All of the policies analysed in this study “supported” CGs in that none prohibited CGs on public land in the LG area. Most of the policies stated that the purpose of the document was to provide a framework for guiding decisions and processes related to how the LG would facilitate community groups to establish and maintain CGs, and to outline the roles and responsibilities of CG stakeholders. In this regard, little has changed in the purpose of CG policies and LGs’ stated role since Pires’ (Citation2011) analysis.

Alongside broader purpose statements, many policies also contained more specific objectives, such as increasing the number of CGs, increasing access to fresh food, and building a connected community; however, overall, the CG policies analysed in this study did not attend to issues of equity and justice, nor to food security in a meaningful way. Some policies included broad language such as that of “inclusion”, but did not specify who (which population sub-groups) were the targets of these inclusion efforts (with the exceptions of Dandenong – culturally and linguistically diverse communities, and Melbourne – refugee communities, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and people with disabilities), the nature of inclusion (e.g. for different cultural or socioeconomic groups and/or special physical accessibility), nor exactly how LG would either themselves directly pursue, or support CG groups to achieve, inclusion and equity outcomes. One policy stated the LG would “inform” disadvantaged and vulnerable groups of opportunities to be involved, but awareness alone is insufficient for action, with factors such as time and interest being important for decisions to participate in CGs (Kingsley, Foenander, and Bailey Citation2019).

Additionally, information on how the LG would measure the success of the policy and stated objectives were contained within only two of the policies. There are inherent complexities in assessing some types of outcomes such as equity, justice, and the inclusivity of CGs (compared with, for example, an objective to increase the number of CGs), and best-practice baseline data for variables such food security are lacking in Australia (Australian Household Food Security Data Coalition Citation2022), particularly at LG geographic level. Furthermore, LGs often lack the capacity and expertise for evaluation, generally (Carrad, Aguirre-Bielschowsky, et al. Citation2022; Carrad, Turner, et al. Citation2022). Forthcoming research may provide an avenue to begin remedying this issue (Kingsley, Bailey, et al. Citation2019).

Responsibility for CG policies was predominantly positioned within departments related to Community, Environment and Infrastructure, and/or Planning, which reflects the departments identified by Beilin and Hunter (Citation2011) in Melbourne, Australia, and Hess and Winner (Citation2007) in cities in the United States of America. The allocation of departmental responsibility could relate to how LGs frame CGs and the objectives they see CGs as achieving. For example, LGs that principally recognise the social benefits of CGs, or potential for CGs to contribute to equity and justice may be more likely to position responsibility within Community-related departments, whereas those who see CGs as a recreational pursuit may delegate responsibility to the Environment and Infrastructure-related departments, which do not traditionally prioritise issues of equity and justice (Jermé and Wakefield Citation2013). Nearly one-quarter of the policies in the present study did not specify a position or department that was responsible for implementation of the policy, and some policies also lacked detail regarding the steps involved in the application and approval process. Addition of departmental responsibility and an outline of the administrative processes in policies that are currently missing this information would be a simple way for LGs to provide greater clarity for CG stakeholders.

The role of Australian LGs in CGs is, at present, largely a facilitator rather than implementation partner, aligning with the sixth governance structure of CGs identified by Fox-Kämper et al. (Citation2018), whereby gardens are developed from a bottom-up approach with political and/or administrative support. LGs’ role as gatekeeper was reflected in the policies analysed here through the prevalence of stated supports that related to the application and establishment phase, rather than garden maintenance. Notably, the three most common forms of support related to licencing, site identification, and the application process; all very early administrative processes. Other supports included facilitating community engagement, providing limited funding, assistance sourcing external grants, and providing in-kind support such as mulch, similar to some previous studies (Fox-Kämper et al. Citation2018; Pires Citation2011).

Few LGs in this study provided assistance with governance matters such as establishing management committees and associated procedures, or becoming an incorporated organisation and securing insurance, which can be challenging for small community groups (Jermé and Wakefield Citation2013; Mintz and McManus Citation2014). This was despite it being a requirement of almost all policies that CGs are incorporated and have insurance. Only five of the policies analysed stated the CG could be covered by the LG’s insurance, and five stated the LG would provide advice to groups on how to obtain external insurance. Other studies have pointed to types of supports that LGs could provide that were less common in the current research. This includes factors such as support with bureaucratic issues (Wesener et al. Citation2020), including CGs in strategic and open space planning (Wesener et al. Citation2020), providing secure, long-term tenure (Hess and Winner Citation2007), allocating a dedicated staff member to act as a contact point for community members wishing to establish a garden and/or to provide ongoing advice and information (Burton et al. Citation2013; Jermé and Wakefield Citation2013), and providing funding opportunities such as place-making grants, and microgrants for CG groups to purchase gardening supplies (Lavallée-Picard Citation2018).

Beyond the supports stated within CG policy documents themselves, LGs can demonstrate their support for CGs by institutionally embedding them as a legitimate land use in broader planning policies and open space strategies (Corkery, Osmond, and Williams Citation2021; Delshad Citation2022; Wesener et al. Citation2020). Zoning regulations could be amended to allow CGs to be more easily established in various zones (Harris Citation2009), and targets for the number and/or location of CGs could be set to provide a measurable accountability mechanism. In this study, the City of Sydney’s (NSW) policy specified their intention to have a CG within one kilometre of the dwellings of most residents. Maitland and North Sydney (also NSW LGs) stated the objective of increasing the number of CGs in the region, but lacked a target number and timeframe. Past examples from the United States include Seattle’s target of adding four new CGs per year (a goal set in 2000) (Hess and Winner Citation2007), and Chicago’s 1998 target to have 1,000 CGs in their area by 2005 (Harris Citation2009).

Limitations

The search strategy used to collect CG policies may have resulted in some existing policies being excluded. Only CG policies that were published on the LG’s website were included, and LGs were not contacted to enquire whether they have a policy that was not available online. The analysis did not include accompanying documentation (e.g. guidelines), so may have overlooked some LGs that are active in the CG space but have not cemented their obligations through an adopted policy. These accompanying documents may provide detailed information regarding CGs, but lack the strength or accountability of policies that have been formally adopted by LGs. Establishment of CGs relies on various factors, such as demand and interest from community members, thus this analysis cannot, and does not attempt to, draw associations between the presence of a CG policy and its quality and the number of CGs that have been established in a given LG jurisdiction.

The scope of this study, which was confined to a document review of all available CG policies from each of the 207 LGs across NSW and Victoria, does not enable us to make conclusions about the implementation, impact or effectiveness of such policies or CGs themselves. Conducting on-the-ground research – including interviews with key stakeholders – to explore the perceived impact that community garden policies have on the establishment and maintenance of gardens, as well as other health, social, and environmental outcomes would be a beneficial piece of future research, but was beyond the scope of the current study.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study has provided evidence of the facilitator role Australian LGs play in CGs. The analysed policies predominantly served to describe a standardised framework for LGs’ (relatively “hands off”) facilitation of CGs, and to outline the roles of CG stakeholders. LGs see CGs as community, environment and infrastructure, or city planning initiatives, as reflected by the departments stated as responsible for CG policy implementation. Given that the inputs and outcomes of CGs span health, social, environmental, and economic domains, LGs could use cross-departmental communication to ensure involvement of and coordination among all relevant staff members (Jermé and Wakefield Citation2013). While their role continues to be one of facilitator, it is important that CG policies and other supporting documentation provide comprehensive information regarding the processes and expectations involved in the establishment and maintenance of CGs.

Based on the findings, we present the following additional recommendations for LGs, community members, and all levels of governments. LGs that have not yet developed and adopted a CG policy but wish to do so can actively encourage CGs in their jurisdiction, in a way that reduces bureaucratic “red tape” (Pires Citation2011; Thornton Citation2017). Policies can be modelled from existing ones (see supplemental material for a list of the LGs with CG policies included in this analysis), but are recommended to also include community engagement to ensure the policy is relevant to the unique context of the particular LG area. For LGs with an existing CG policy, when the policy is due for review, involve existing CGs in participatory methods and refer to policies from other LGs to consider whether the specificity of the information and nature of supports can be improved. Drawing on the common elements in the analysed policies, it is recommended that policies contain, at minimum: a broad purpose statement; detailed objectives and targets (and where possible, evaluation mechanisms); a description of the roles and responsibilities of garden stakeholders (including LG, CG committees, garden volunteers, and other potential partners); types of gardens covered by the policy (e.g. includes community-run gardens on public land but excludes gardens on school land); a detailed list of the supports provided (and not provided) by the LG to garden committees; the staff member(s) and/or department(s) responsible for policy implementation, and who residents can liaise with; site selection criteria; and a description of any specific requirements (e.g. obtaining insurance, paying a licencing fee).

Policies can be accompanied by “toolkits” (including guidelines, checklists, and templates) for community groups to use to understand the requirements of establishing and maintaining a CG. These toolkits should be developed in collaboration with existing community gardeners to ensure their completeness and comprehensibility. If the policy stipulates requirements such as the community group needing to obtain insurance and become formally incorporated, LGs should aim to provide adequate information and advice regarding these matters. This need not generate additional work for LG staff, as they could direct community groups to existing relevant authorities or advisory bodies, such as Justice ConnectFootnote2 or Our CommunityFootnote3, that provide free and/or low-cost governance information and training to not-for-profit organisations. LGs could consider having policies and toolkits translated into different languages to assist culturally and linguistically diverse groups to understand the requirements (Kirby et al. Citation2020).

LGs can institutionalise processes that protect arable land from being irreversibly developed for other uses, and preserve this land for food production (both community and commercial uses). They could proactively map public land to develop inventories of areas suitable for CGs (Eanes and Ventura Citation2015), and display this publicly, such as through an interactive online map (Lavallée-Picard Citation2018), a strategy that could reduce the elapsed time between a community group initiating the conversation with the LG, completion of the application process, and the commencement of gardening activities on the site (Harris Citation2009; Pires Citation2011). The creation of a CG zoning classification would mean suitable land is dedicated to this purpose only (Harris Citation2009). Requiring development applications for new land releases and infill development to include land reserved for community food production is another planning strategy that could preserve land for CGs (Spencer Citation2014). In relation to protecting private land for food growing, there may be opposition from developers whose interests are purely financial and want to maximise the number of dwellings they can build and sell. However, the various benefits CGs are known to provide (health, social, ecological services) must be prioritised over neoliberal economics and commodification of natural and public assets that benefit the few. Schoen, Caputo, and Blythe (Citation2020) demonstrated that for every dollar invested in a CG, the garden produced three times that in social value, and this would increase if environmental value were to be included in their calculations. Although, to present a traditional economic perspective, there is evidence that property values increase with proximity to CGs (Guitart, Pickering, and Byrne Citation2012; Voicu and Been Citation2008). Accordingly, LGs could work with developers in the design of new suburbs to include communal spaces for residents to grow food, which may become increasingly important in the face of urbanisation.

LGs could encourage increased knowledge-sharing, both between the LG and CG members, and peer-to-peer among gardeners. A staff member could be designated as a liaison for CG members (Jermé and Wakefield Citation2013), LGs could host their own and/or promote external events and resources that facilitate networking and learning between CG groups, and provide information on sustainable, local food production (e.g. Urban Agriculture Month, International Compost Awareness Week, Fair Food Week). LGs could also provide funding for CGs to organise and host events to share their knowledge with other community members.

Finally, LGs could strengthen their own relevant networks, and those between CGs, by engaging with aligned organisations such as Community Gardens Australia, the peak body for CGs. Community Gardens Australia are subject matter experts and are thus well-positioned to assist both LGs and CG groups. LGs could benefit from engagement with Community Gardens Australia through: receiving assistance in developing and revising CG policies without needing to “reinvent the wheel”; amplifying LG promotion of CG presence and events; having LGs’ CGs listed in an online directory; and being involved in learning opportunities to strengthen LGs’ capacity to provide effective support to CGs.

Community members residing in LG areas that do not currently have a CG policy can encourage the LG to create and adopt one (Jermé and Wakefield Citation2013). Residents of LG areas where a policy exists can explore ways to be involved in consultation and providing feedback on the policy, become involved in a CG themselves (existing or new), and engage with Community Gardens Australia.

All levels of government can allocate funding for edible gardens at the community level. Some LGs already make funding available to CG groups through community grants programmes, but such programmes could be expanded. The City of Boston in the United States is a leader in this space, with investment in staffing to facilitate urban agriculture, and an additional financial allocation (approximately US$1.6 million) in the annual budget (Shani Fletcher, Director GrowBoston: Office of Urban Agriculture, email to author, 6 December 2022). Sustain: The Australian Food Network’s Pandemic Gardening Survey and subsequent call for a $500 million (AUD) national Edible Gardening Fund (Donati and Rose Citation2020) is a government investment that would contribute to the known health, social, food security, environmental, and economic returns that CGs bring.

Author contributions

A.C. designed the study, conducted data collection and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. N.R., K.C. and B.R. provided input into the manuscript. All authors performed critical review of the manuscript’s intellectual content and approved the final version submitted.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Naomi Lacey (Community Gardens Australia) for providing comments on a draft of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 While most Australians are food secure, available data indicate there are a significant number who are not. Any amount of food insecurity is concerning, particularly given Australia’s status as a high-income country. Data on and monitoring of food (in)security in Australia is severely lacking, making it challenging to fully understand the scale of the problem. Existing data are outdated [e.g., 2011–2012 National Health Survey (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2015); 2012–2013 Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2014)], not representative [e.g., annual Foodbank Hunger Reports (Foodbank Australia Citationn.d.)], not standardised, and/or not based on best-practice tools for gathering food (in)security data. In December 2022, the Australian Household Food Security Data Coalition released a consensus statement calling for Australian governments to conduct regular monitoring and reporting of food insecurity using the USDA 18-item household food security survey module (Australian Household Food Security Data Coalition Citation2022). Despite current issues, available data identify selected population sub-groups that experience higher rates of food insecurity than others, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, culturally and linguistically diverse groups, university students, low socioeconomic households, households with children, people on disability support pensions, and people living in rural areas (Louie, Shi, and Allman-Farinelli Citation2022). Additionally, research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic documented increases in household food insecurity (Louie, Shi, and Allman-Farinelli Citation2022).

References

- Abelson, P. 2022. The Principles and Practice of Local Government in the Australian Three-tiered System of Government: With Special Reference to the Roles of State and Local Government in New South Wales. Canberra: Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, Crawford School of Public Policy, The Australian National University.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2014. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Updated Results, 2012–13. Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/4727.0.55.006.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2015. Australian Health Survey: Nutrition - State and Territory results. Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/australian-health-survey-nutrition-state-and-territory-results/2011-12.

- Australian Household Food Security Data Coalition. 2022. “Household Food Security Data Consensus Statement.” https://righttofood.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Household-Food-Security-Data-Consensus-Statement2022.pdf.

- Bailey, Aisling, and Jonathan Kingsley. 2020. “Connections in the Garden: Opportunities for Wellbeing.” Local Environment 25 (11-12): 907–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2020.1845637.

- Bakhtiari, Sasan. 2021. “Trends in Market Concentration of Australian Industries.” Australian Economic Review 54 (1): 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8462.12393.

- Barron, Jennifer. 2017. “Community Gardening: Cultivating Subjectivities, Space, and Justice.” Local Environment 22 (9): 1142–1158. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2016.1169518.

- Beilin, Ruth, and Ashlea Hunter. 2011. “Co-constructing the Sustainable City: How Indicators Help us ‘Grow’ More Than Just Food in Community Gardens.” Local Environment 16 (6): 523–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2011.555393.

- Bowden, Mitchell. 2020. Understanding Food Insecurity in Australia. CFCA paper no 55. Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Burton, Paul, Kristen Lyons, Carol Richards, Marco Amati, Nicholas Rose, Lotus Desfours, Victor Pires, and Rochelle Barclay. 2013. Urban Food Security, Urban Resilience and Climate Change. Gold Coast: National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility.

- Butterfield, Katie L, and A Susana Ramírez. 2021. “Framing Food Access: Do Community Gardens Inadvertently Reproduce Inequality?” Health Education & Behavior 48 (2): 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198120950617.

- Carpenter, R Charli. 2010. “Governing the Global Agenda: ‘Gatekeepers’ and ‘Issue Adoption’in Transnational Advocacy Networks.” In Who Governs the Globe?, edited by Deborah Avant, Martha Finnemore, and Susan Sell, 202–237. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carrad, Amy, Ikerne Aguirre-Bielschowsky, Nick Rose, Karen Charlton, and Belinda Reeve. 2022. “Food System Policy Making and Innovation at the Local Level: Exploring the Response of Australian Local Governments to Critical Food Systems Issues.” Health Promotion Journal of Australia 34 (2): 488–499. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpja.626.

- Carrad, Amy, Lizzy Turner, Nick Rose, Karen Charlton, and Belinda Reeve. 2022. “Local Innovation in Food System Policies: A Case Study of Six Australian Local Governments.” Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 12 (1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2022.121.007.

- Clapp, Jennifer. 2021. “The Problem with Growing Corporate Concentration and Power in the Global Food System.” Nature Food 2 (6): 404–408. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00297-7.

- Corkery, Linda, Paul Osmond, and Peter Williams. 2021. “Legal Frameworks for Urban Agriculture: Sydney Case Study.” Journal of Property, Planning and Environmental Law 13 (3): 218–235. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPPEL-06-2020-0030.

- Davila, Federico, and Robert Dyball. 2015. “Transforming Food Systems Through Food Sovereignty: An Australian Urban Context.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 31 (1): 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1017/aee.2015.14.

- Delshad, Ashlie B. 2022. “Community Gardens: An Investment in Social Cohesion, Public Health, Economic Sustainability, and the Urban Environment.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 70: 127549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127549.

- Donati, Kelly, and Nick Rose. 2020. “‘Every Seed I Plant is a Wish for Tomorrow’: Findings and Action Agenda from the 2020 National Pandemic Gardening Survey.” Sustain: The Australian Food Network. https://sustain.org.au/projects/pandemic-gardening-survey-report/.

- Eanes, Francis, and Stephen J. Ventura. 2015. “Inventorying Land Availability and Suitability for Community Gardens in Madison, Wisconsin.” Cities and the Environment (CATE) 8 (2): 2.

- Evers, Anna, and Nicole Louise Hodgson. 2011. “Food Choices and Local Food Access Among Perth's Community Gardeners.” Local Environment 16 (6): 585–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2011.575354.

- Foodbank Australia. (n.d.). “Hunger in Australia: The Facts.” Accessed February 2023. https://www.foodbank.org.au/hunger-in-australia/the-facts/?state=au.

- Fox-Kämper, Runrid, Andreas Wesener, Daniel Münderlein, Martin Sondermann, Wendy McWilliam, and Nick Kirk. 2018. “Urban Community Gardens: An Evaluation of Governance Approaches and Related Enablers and Barriers at Different Development Stages.” Landscape and Urban Planning 170: 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.06.023.

- Guitart, Daniela, Catherine Pickering, and Jason Byrne. 2012. “Past Results and Future Directions in Urban Community Gardens Research.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 11 (4): 364–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2012.06.007.

- Harris, Elise. 2009. “The Role of Community Gardens in Creating Healthy Communities.” Australian Planner 46 (2): 24–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2009.9995307.

- Hendrickson, Mary K. 2015. “Resilience in a Concentrated and Consolidated Food System.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 5 (3): 418–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-015-0292-2.

- Hess, David, and Langdon Winner. 2007. “Enhancing Justice and Sustainability at the Local Level: Affordable Policies for Urban Governments.” Local Environment 12 (4): 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830701412489.

- Hinrichs, C. Clare. 2003. “The Practice and Politics of Food System Localization.” Journal of Rural Studies 19 (1): 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(02)00040-2.

- James, Sarah W. 2016. “Beyond ‘Local’ Food: How Supermarkets and Consumer Choice Affect the Economic Viability of Small-scale Family Farms in S ydney, Australia.” Area 48 (1): 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12243.

- Jermé, Erika S, and Sarah Wakefield. 2013. “Growing a Just Garden: Environmental Justice and the Development of a Community Garden Policy for Hamilton, Ontario.” Planning Theory & Practice 14 (3): 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2013.812743.

- Kent, Katherine, Sandra Murray, Beth Penrose, Stuart Auckland, Denis Visentin, Stephanie Godrich, and Elizabeth Lester. 2020. “Prevalence and Socio-demographic Predictors of Food Insecurity in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Nutrients 12 (9): 2682. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092682.

- Kingsley, Jonathan, Aisling Bailey, Nooshin Torabi, Pauline Zardo, Suzanne Mavoa, Tonia Gray, Danielle Tracey, et al. 2019. “A Systematic Review Protocol Investigating Community Gardening Impact Measures.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (18): 3430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183430.

- Kingsley, Jonathan, Emily Foenander, and Aisling Bailey. 2019. “‘You Feel Like You’re Part of Something Bigger’: Exploring Motivations for Community Garden Participation in Melbourne, Australia.” BMC Public Health 19 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6343-3.

- Kirby, Caitlin K, Lissy Goralnik, Jennifer Hodbod, Zach Piso, and Julie C. Libarkin. 2020. “Resilience Characteristics of the Urban Agriculture System in Lansing, Michigan: Importance of Support Actors in Local Food Systems.” Urban Agriculture & Regional Food Systems 5 (1): e20003. https://doi.org/10.1002/uar2.20003.

- Lapping, Mark B. 2004. “Toward the Recovery of the Local in the Globalizing Food System: The Role of Alternative Agricultural and Food Models in the US.” Ethics, Place & Environment 7 (3): 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/1366879042000332943.

- Lavallée-Picard, Virginie. 2018. “Growing in the City: Expanding Opportunities for Urban Food Production in Victoria, Canada.” Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 8 (B): 157–173. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2018.08B.005.

- Lawrence, Geoffrey, Carol Richards, and Kristen Lyons. 2013. “Food Security in Australia in an Era of Neoliberalism, Productivism and Climate Change.” Journal of Rural Studies 29: 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2011.12.005.

- Louie, Serena, Yumeng Shi, and Margaret Allman-Farinelli. 2022. “The Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Security in Australia: A Scoping Review.” Nutrition & Dietetics 79 (1): 28–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/1747-0080.12720.

- Lyons, Kristen, Carol Richards, Lotus Desfours, and Marco Amati. 2013. “Food in the City: Urban Food Movements and the (Re)-imagining of Urban Spaces.” Australian Planner 50 (2): 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2013.776983.

- Malberg Dyg, Pernille, Søren Christensen, and Corissa Jade Peterson. 2019. “Community Gardens and Wellbeing amongst Vulnerable Populations: A Thematic Review.” Health Promotion International 35 (4):790-803. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daz067.

- Mattson, Gary A. 1989. “Decision Rules, Gatekeepers, and the Delivery of Municipal Services.” Public Productivity & Management Review 13 (2): 195–199. https://doi.org/10.2307/3380946.

- Mehrabi, Zia, Ruth Delzeit, Adriana Ignaciuk, Christian Levers, Ginni Braich, Kushank Bajaj, Araba Amo-Aidoo, et al. 2022. “Research Priorities for Global Food Security Under Extreme Events.” One Earth 5 (7): 756–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2022.06.008.

- Mintz, Gregory, and Phil McManus. 2014. “Seeds for Change? Attaining the Benefits of Community Gardens through Council Policies in Sydney, Australia.” Australian Geographer 45 (4): 541–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2014.953721.

- Mougeot, Luc JA. 2000. “Urban Agriculture: Definition, Presence, Potentials and Risks, and Policy Challenges.” In Cities Feeding People Series Report 31, 1–42. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre.

- Mulholland, Isabella. 2022. ‘Abused Twice’: The ‘Gatekeeping’ of Housing Support for Domestic Abuse Survivors in Every London Borough. London: Public Interest Law Centre.

- Music, Janet, Erica Finch, Pallavi Gone, Sandra Toze, Sylvain Charlebois, and Lisa Mullins. 2021. “Pandemic Victory Gardens: Potential for Local Land Use Policies.” Land Use Policy 109: 105600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105600.

- Nemes, Gusztáv, Yuna Chiffoleau, Simona Zollet, Martin Collison, Zsófia Benedek, Fedele Colantuono, Arne Dulsrud, et al. 2021. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Alternative and Local Food Systems and the Potential for the Sustainability Transition: Insights from 13 Countries.” Sustainable Production and Consumption 28: 591–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.06.022.

- Parker, Christine, and Hope Johnson. 2019. “From Food Chains to Food Webs: Regulating Capitalist Production and Consumption in the Food System.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 15 (1): 205–225. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-101518-042908.

- Perera, Ethmadalage Dineth, Magnus Moglia, and Stephen Glackin. 2023. “Beyond ‘Community-Washing’: Effective and Sustained Community Collaboration in Urban Waterways Management.” Sustainability 15 (5): 4619. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054619.

- Pires, Victor. 2011. “Planning for Urban Agriculture Planning in Australian Cities.” Paper presented at the 5th State of Australian Cities National Conference, Melbourne, Australia, November 29–December 2.

- Pudup, Mary Beth. 2008. “It Takes a Garden: Cultivating Citizen-subjects in Organized Garden Projects.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 39 (3): 1228–1240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.06.012.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. 2018. “NVivo.” V.12. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

- Raneng, Jesse, Michael Howes, and Catherine Marina Pickering. 2022. “Current and Future Directions in Research on Community Gardens.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 79: 127814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127814.

- Schoen, Victoria, Silvio Caputo, and Chris Blythe. 2020. “Valuing Physical and Social Output: A Rapid Assessment of a London Community Garden.” Sustainability 12 (13): 5452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135452

- Shisanya, Stephen O, and Sheryl L. Hendriks. 2011. “The Contribution of Community Gardens to Food Security in the Maphephetheni Uplands.” Development Southern Africa 28 (4): 509–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2011.605568.

- Spencer, Liesel. 2014. “Farming the City: Urban Agriculture, Planning Law and Food Consumption Choices.” Alternative Law Journal 39 (2): 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1037969X1403900211

- Springmann, Marco, Michael Clark, Daniel Mason-D’Croz, Keith Wiebe, Benjamin Leon Bodirsky, Luis Lassaletta, Wim De Vries, et al. 2018. “Options for Keeping the Food System within Environmental Limits.” Nature 562 (7728): 519–525. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0594-0.

- Swinburn, Boyd A., Vivica I. Kraak, Steven Allender, Vincent J. Atkins, Phillip I. Baker, Jessica R. Bogard, Hannah Brinsden, et al. 2019. “The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission report.” The Lancet 393 (10173): 791–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32822-8.

- Thompson, Susan, Linda Corkery, and Bruce Judd. 2007. “The Role of Community Gardens in Sustaining Healthy Communities.” Paper presented at the 3rd State of Australian Cities National Conference, Adelaide, Australia, November 28–30.

- Thornton, Alec. 2017. “‘The Lucky Country’? A Critical Exploration of Community Gardens and City–community Relations in Australian Cities.” Local Environment 22 (8): 969–985. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2017.1317726.

- Voicu, Ioan, and Vicki Been. 2008. “The Effect of Community Gardens on Neighboring Property Values.” Real Estate Economics 36 (2): 241–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6229.2008.00213.x.

- Wang, Haoluan, Feng Qiu, and Brent Swallow. 2014. “Can Community Gardens and Farmers’ Markets Relieve Food Desert Problems? A Study of Edmonton, Canada.” Applied Geography 55: 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.09.010.

- Wesener, Andreas, Runrid Fox-Kämper, Martin Sondermann, and Daniel Münderlein. 2020. “Placemaking in Action: Factors that Support or Obstruct the Development of Urban Community Gardens.” Sustainability 12 (2): 657. doi:10.3390/su12020657.