ABSTRACT

Decolonial and feminist scholars have long pointed out that theory and praxis in global health and gender and development employ models of gender and social change that are Euro-North-American-centric and fit poorly with cultural realities and community dynamics in the global South. Interventions informed by these biases are often minimally effective and can cause backlash or resistance. In this paper, we unpack how coloniality informs some of the dominant approaches used by major organisations to improve the health and well-being of adolescent girls, and why they can result in ineffective and sometimes harmful interventions. The limitations of these approaches include top-down imposed objectives and pathways to change; individualist, sexist, ageist, and modernist biases; and ignorance or denigration of local cultural values, resources, and family and community dynamics. Instead, we present the Girls’ Holistic Development (GHD) programme – implemented by NGO The Grandmother Project – Change Through Culture (GMP) in Senegal since 2009 – as a decolonial alternative. The GHD is informed by theories and methodologies from participatory and community development; anthropology; family and community systems theory; community, cultural, and Indigenous psychology; and transformative learning/adult education. Results show that GMP has contributed to shifting social norms underpinning child and forced marriage, female genital cutting, adolescent pregnancy, and premature school-leaving because its approach offers an alternative decolonial vision of, and method of achieving, adolescent girls’ development. The key facets of this approach are that it is culturally affirming, inter-generational, grandmother-inclusive, assets-based, and rooted in building community capacity and consensus for change towards locally defined objectives.

Les chercheurs décoloniaux et féministes font depuis longtemps remarquer que la théorie et la pratique en matière de santé, de genre et de développement à l'échelle mondiale utilisent des modèles de genre et de changement social qui sont axés sur l'Europe et l'Amérique du Nord, et sont en déphasage avec les réalités culturelles et la dynamique des communautés de l'hémisphère Sud. Les interventions éclairées par ces préjugés sont souvent peu efficaces et peuvent donner lieu à des réactions négatives ou à une résistance. Dans cet article, nous analysons en quoi la colonialité éclaire certaines des approches dominantes utilisées par les grandes organisations pour améliorer la santé et le bien-être des adolescentes, et les raisons pour lesquelles ces approches peuvent aboutir à des interventions inefficaces – et parfois nuisibles. Parmi les limites de ces approches figurent des objectifs et des voies de changement imposés du haut vers le bas ; des préjugés individualistes, sexistes, âgistes et modernistes ; et l'ignorance ou le dénigrement des valeurs culturelles, des ressources et des dynamiques familiales et communautaires locales. Nous présentons donc le programme Girls Holistic Development (GHD), mis en œuvre par l'ONG The Grandmother Project – Change Through Culture (GMP) au Sénégal depuis 2009, comme alternative décoloniale. Le programme GHD s'appuie sur des théories et des méthodologies issues du développement participatif et communautaire, de l'anthropologie, de la théorie des systèmes familiaux et communautaires, de la psychologie communautaire, culturelle et autochtone, et de l'apprentissage transformateur/l'éducation des adultes. D'après les résultats, le GMP a contribué à modifier les normes sociales qui sous-tendent le mariage d'enfants et les mariages forcés, les mutilations génitales féminines, les grossesses d'adolescentes et l'abandon prématuré de l'école, parce que son approche propose une vision décoloniale alternative du développement des adolescentes et une méthode pour y parvenir. Les aspects clés de cette approche sont qu'elle fait honneur à la culture, qu'elle est intergénérationnelle, qu'elle inclut les grands-mères, qu'elle est basée sur les actifs et qu'elle est ancrée dans le renforcement des capacités de la communauté et du consensus pour le changement en vue d'atteindre des objectifs définis au niveau local.

Hace mucho tiempo que los estudiosos de la descolonialidad y el feminismo señalan que la teoría y la práctica inherentes a la salud mundial, el género y el desarrollo emplean modelos de cambio social y de género centrados en Europa y Norteamérica, los cuales no encajan en las realidades culturales y las dinámicas comunitarias del Sur global. Las intervenciones basadas en estos prejuicios suelen ser mínimamente eficaces y pueden provocar reacciones negativas o resistencia. En este trabajo explicamos cómo la colonialidad se expresa en algunos de los enfoques dominantes utilizados por las principales organizaciones para mejorar la salud y el bienestar de adolescentes, y por qué puede dar lugar a intervenciones ineficaces y a veces perjudiciales. Las limitaciones de estos modelos incluyen objetivos y vías de cambio impuestos desde arriba; prejuicios individualistas, sexistas, edadistas y modernistas; e ignorancia o denigración de valores culturales, recursos y dinámicas familiares y comunitarias locales. En su lugar, presentamos el programa Desarrollo Holístico de las Niñas (GHD, por sus siglas en inglés), aplicado por la ONG The Grandmother Project-Change Through Culture (GMP) en Senegal desde 2009, como una alternativa descolonial. El GHD se fundamenta en teorías y metodologías del desarrollo participativo y comunitario, la antropología; la teoría de sistemas familiares y comunitarios; la psicología comunitaria, cultural e indígena; el aprendizaje transformador y la educación de adultos. Los resultados dan cuenta de que su aplicación contribuyó a modificar las normas sociales que subyacen al matrimonio infantil y forzado, la mutilación genital femenina, el embarazo adolescente y el abandono escolar prematuro, pues alimenta una visión descolonial alternativa del desarrollo de las adolescentes, así como un método para lograrlo. Las facetas clave de este enfoque son la promoción de la afirmación cultural, su carácter intergeneracional, la inclusión de las abuelas, el hecho de basarse en los activos y su arraigo en el fortalecimiento de la capacidad y el consenso comunitarios para impulsar el cambio hacia objetivos definidos localmente.

Introduction

In this paper, we unpack how coloniality informs the dominant approaches used by major organisations to support the rights and well-being of adolescent girls, and why they can result in ineffective and sometimes harmful interventions. In contrast, we describe the Girls’ Holistic Development (GHD) programme, implemented by the NGO The Grandmother Project – Change Through Culture (GMP), as a decolonial alternative.

The GHD programme was launched in Vélingara, southern Senegal, in 2009, after a year-long process of formative research and community consultations (Aubel and Lombardo Citation2006b). From 2009 to 2012, the GHD was funded by World Vision Senegal which tasked GMP with designing and implementing a programme to reduce female genital cutting (FGC), child, early, and forced marriage (CEFMU), adolescent pregnancy, and premature school-leaving – because rates of these phenomena in Vélingara were, and continue to be, among the highest in Senegal (Musoko et al. Citation2012, preface). Since 2013, GMP has received some funding from major donors like UNFPA and UNICEF, but mainly relies on private donations and one-year grants from private philanthropic foundations and organisations based in Europe and the US.

In what follows, we reflect on our positionalities and the process of producing knowledge about the GHD programme. We then present how coloniality manifests in interventions to improve adolescent girls’ health and well-being, and what approaches we consider to be decolonial alternatives and why. We then describe the activities of the GHD programme as well as its limitations, to generate insights and recommendations for researchers, practitioners, and donors working to decolonise development and global health.

Situating ourselves in relation to knowledge production

We acknowledge that power inequalities are always present in knowledge production. Even decolonial scholarship sometimes reproduces ‘colonial impulses and erasures’ despite the authors’ explicit attempts to advance epistemic decolonisation – which can result in ‘decolonial woes’ or ‘the silences enacted by the very decolonial practitioners who call out other silences’ (Ortega Citation2017, 504). In what follows, we therefore strive to reflect upon our own positionalities, the process of co-creating this text, and the limitations as well as strengths of GMP’s GHD programme.

Anneke Newman is a white cis-gender British woman living in Belgium. She is bilingual English–French and has basic proficiency in Pulaar, one of the main languages spoken in Senegal. She worked in the charity sector in the UK throughout her twenties, and was disappointed to discover that few development programmes reflected the principles of power-sharing with communities in their design and implementation. In 2011, while undertaking fieldwork in Senegal as part of her doctorate in anthropology, Anneke volunteered with GMP. She was impressed by the alignment between the programme’s strategy and local cultural dynamics, as well as the close, relaxed, and respectful relationships between GMP staff and local community members. Anneke worked for GMP on short assignments in 2015 and 2016, and participated in a realist evaluation of GMP’s approach in 2017.

Judi Aubel is a white cis-gender woman of North American nationality fluent in English, French, and Italian, who lives between Italy and Senegal. She lived for 15 years in Senegal as a consultant–researcher–evaluator of NGOs working on health in West Africa, and consistently observed the dominance of intervention models informed by Euro-North-American-centric values and concepts. She created the NGO GMP in 2005 to develop action research-based community-level maternal and child health programmes informed by, and tailored to, cultural values and community and family roles in ‘non-Western’ societies. Designing the GHD project was an opportunity for GMP to undertake a long-term programme on adolescent health which recognises and builds upon the important roles and values of communities in Senegal.

Mamadou Coulibaly is a Black cis-gender man from Vélingara, Senegal. He is fluent in French and three Senegalese languages, Pulaar, Mandinka, and Wolof. Trained as a teacher, he was involved for many years in community literacy and development projects, and civil society efforts to promote abandonment of FGC. He joined GMP in 2008 as the main facilitator of the GHD activities, and became project co-ordinator in 2012. He co-designs and co-ordinates implementation of the GHD activities with Judi’s conceptual guidance and feedback from community members. He was attracted to GMP because of its innovative approach grounded in local cultural values and relationships. He brings a valuable insider perspective on Senegalese cultural and institutional dynamics, as well as skills in facilitation, project management, and research.

In 2022, Anneke obtained a research grant from the Belgian government to investigate – with GMP as an official partner – the gap between Euro-North-American-centric policies and models, and community worldviews and priorities, in programmes aimed at reducing FGC and CEFMU. Project methodology is informed by principles of transnational feminist praxis (Nagar and Lock Swarr Citation2010) which argues that collaborations between academic and non-academic actors between the global North and South can reproduce power inequalities, and demands constant dialogue and reflexivity to balance divergent interests. So far, we have found this balancing possible because we share the objectives of promoting culturally grounded and participatory approaches, critiquing coloniality in global health and gender and development, and proposing possible decolonial alternatives dedicated to working with and for local communities.

Nonetheless, challenges have arisen in co-creating knowledge about the GHD programme. Anneke wrote the paper, while Judi explained the theoretical underpinnings of the GHD approach and reviewed each draft. Meanwhile, Mamadou explained the day-to-day implementation of the GHD activities, and limitations and challenges of the approach. The time constraints, and the highly complex conceptual underpinnings of GMP’s approach, mean that there continues to be a risk that Anneke might misrepresent aspects of the programme.

In terms of the data mobilised to support our description of the GHD programme, we cite the findings of an independent realist evaluation conducted by the Institute of Reproductive Health at the University of Georgetown from 2017 to 2021. Through quantitative surveys and in-depth qualitative interviews with members of programme and control villages, the evaluation found that the GHD had contributed to shifts in knowledge, attitudes, social norms, and reported practices surrounding FGC, CEFMU, adolescent pregnancy, and premature school-leaving, among key community authorities (mothers, fathers, and grandmothers). The programme also fostered a greater sense among adolescent girls that their views and preferences would be considered and supported by family and community members (Kohli et al. Citation2021; Shaw et al. Citation2020).

However, as is often the case in global health more widely (Janes and Corbett Citation2009; Pant et al. Citation2022; Whitehead Citation2007), independent evaluations of the GHD have focused narrowly on measuring outcomes of the GHD that align with the donors’ and public health scholars’ objectives of health-related behaviour change. Therefore, we also present studies commissioned by GMP that have used qualitative and participatory visual methods with a wide range of community actors, as well as ethnographic observation and informal conversations during and after programme activities, to better understand the processes that contribute to these outcomes, as well as community perceptions of the programme (Aubel Citation2020; Diallo Citation2019; GMP Citation2015; Lulli Citation2020; Musoko et al. Citation2012; Saavedra Citation2022; Soukouna and Newman Citation2015). In terms of the reliability of these data, Mamadou and other GMP field staff are in frequent contact with community members involved in the GHD, and their relationships of trust over many years have enabled more honest community feedback on the programme than is often the case. Nonetheless, we lack observation of community dynamics or community feedback generated independently of GMP and its partners, and there is therefore always a possibility of respondent bias. Finally, we include several photos and videos to accompany the text. All individuals featured therein have given verbal consent for their image to be shared.

Coloniality in global health and gender and development

In what follows, we unpack three major ways in which coloniality manifests in global health and gender and development broadly, and in projects to improve adolescent girls’ rights and well-being specifically. We juxtapose these with the alternative theoretical paradigms that underpin GMP’s GHD programme, which can be considered a decolonial alternative. We understand coloniality as referring to global inequalities which structure much of the contemporary world, and stem from Euro-North-American imperialisms and contemporary cultural hegemony. These inequalities include the imbalanced distribution of decision-making authority, material resources, knowledge production, and social inequalities based on gender, sexual orientation, and race (Grosfoguel Citation2007; Lugones Citation2007; Quijano Citation2007). Coloniality is grounded in the binary of modernity–tradition that emerged during the Enlightenment. Modernity is associated with the principles of progress and emancipation, but tends to be grounded in Euro-North-American cultural values, norms, and ideals. Tradition is associated with backwardness, inequality, and suffering, and tends to be attributed to the worldviews, institutions, and livelihoods of Black, Brown, and Indigenous peoples in the global South or settler colonial contexts in the North (Bialostocka Citation2020). Meanwhile, decoloniality is a political project which aims to identify, understand, and dismantle coloniality – as well as other inequalities – to create a more just world. There is no single model to follow, as decolonial theorists promote pluriversity – the idea is that there are no one-size-fits-all solutions, and that all peoples should be empowered to chart their own path (Walsh and Mignolo 2018).

Whose development? From top-down universal agendas to consensual community-driven problem-solving

International development grew out of the colonial project and, despite the good intentions of development actors, it often reproduces the modernity–tradition binary (Bialostocka Citation2020). ‘Experts’ are associated with ‘progress’, and markers of expert status often include White race, location in Europe or North America, and/or education in universities – and experience working in institutions – whose theoretical paradigms reflect Euro-North-American-centric perspectives (Kothari Citation2006). Local communities – framed as ‘targets’ or ‘beneficiaries’ of development – are generally assumed to be ‘conservative’ and/or lacking the awareness, capacity, or resources to change their situation. ‘Solutions’ come in top-down, universal forms derived from values and models based on Euro-North-American perspectives. They often aim to address single issues – like FGC or CEFMU – in isolation, and define success narrowly in terms of instrumental objectives to reduce such practices, not community priorities or perceptions of interventions (Janes and Corbett Citation2009; Pant et al. Citation2022; Whitehead Citation2007). Definitions of ‘rigorous evidence’ and ‘objectivity’ that inform policy are biased towards data that are often difficult or impossible for local communities to produce, whose own perspectives are dismissed as ‘anecdotal’ (Borda Citation1999; Pant et al. Citation2022). Such interventions fail to address local community priorities or worldviews, and reproduce hierarchies by neglecting the marginalised in their design and implementation. They are often perceived by community members as irrelevant or harmful, and frequently provoke resistance (Esho, Van Wolputte, and Enzlin Citation2011; Shell-Duncan Citation2008). They do not build capacity within communities to self-organise and, hence, encourage dependency by hindering collective empowerment to effect change (Foster-Fishman et al. Citation2007).

In contrast, in line with decolonial principles, proponents of participatory and community development advocate that community members must be involved throughout the development process from conception to design, implementation, and evaluation, to ensure that the change process results from consensus not coercion (Borda Citation1999). In addition to the ethical imperative of such an approach, change is more likely to be sustained if individuals and communities own and define the change process, and that its goals are adapted to local realities (Aubel and Sihalathavong Citation2001). Indeed, GMP conducted 18 months of community consultation to inform the design of the GHD in Senegal, which involved understanding community members’ perceptions of, and explanations for, factors that undermined girls’ health and well-being (Aubel and Lombardo Citation2006b). Results were that community members, young and old, perceived that cultural values, knowledges, and practices were being lost due to the breakdown in inter-generational trust and communication, as a result of the influence of Westernisation of school content, mass media, and international development programmes. Addressing these concerns became a principal programme objective.

Moreover, theorists of community development argue that behaviour change – whether catalysed from within or outside a community – requires building community capacity for collective action. Foundations of community capacity include: skills and knowledge relevant to targeted issues; formal and informal local leadership that builds social cohesion, trust, and a sense of shared community identity; relationships that promote dialogue and collective problem-solving; community efficacy and confidence; and a culture of learning (Gallagher et al. Citation2003). Furthermore, an assets-based approach to community development recognises that problems exist, but also identifies and strengthens positive community resources and capacity to resolve these problems. This approach is empirically proven to increase community engagement and positive intervention outcomes (Trickett et al. Citation2011).

GMP draws on these insights from community development and uses a participatory action research methodology (Borda Citation1999). In this approach, the NGO catalyses – rather than defines or imposes – the change process. GMP supports communities to identify formal and informal leaders and key actors from all groups who influence, or are affected by, adolescents’ rights, health, and well-being. It then facilitates dialogue and builds capacity to discuss shared problems and define a vision of the future. In Vélingara, community members identified key parameters of girls’ holistic development that the GHD programme addresses in a holistic way: physical, emotional/psychological, intellectual, cultural, moral, and spiritual (Musoko et al. Citation2012, 20). GMP supports community members to reach a consensus on objectives and an action plan; assign responsibilities and implement tasks; measure outcomes and changes; and engage in ongoing community consultation to feed back into the process (Aubel Citation2014, 80–5).

Finally, another manifestation of coloniality in global health and development strategies is that most entail the dissemination of messages to persuade people to ‘comply’ with expert-proposed changes in behaviour. This top-down, one-way mode of communication assumes that people will internalise the prescribed messages and change their behaviour accordingly. This linear, behaviourist thinking has been critiqued since the 1970s. Rather, individuals process new information based on prior experiences, prevailing social and cultural norms, and influence of peers – particularly authoritative members of their social network. Decolonial practitioners have also argued that the often-used linear communication model is unethical as it creates a dependency relationship between development programmes and communities (Aubel and Sihalathavong Citation2001). Instead, GMP’s approach uses transformative and empowering education/learning techniques informed by the insights of Paulo Freire and feminist pedagogy, which do not direct participants on how they ought to think or behave. Instead, their tools depict problems that communities are likely to encounter through role plays, theatre, or pictures designed to be accessible to individuals with and without literacy skills (Aubel Citation2017; Musoko et al. Citation2012, 35). Facilitators then open discussion of people’s experiences of these scenarios, and support the development of their capacity to analyse new information actively and critically, propose solutions, and design their own strategies to deal with these problems (Taylor and Cranton Citation2012).

How is culture relevant to development? From Euro-North-American-centric paradigms to cultural renewal

Another way that development organisations working to reduce gendered inequalities reproduce the colonialist modernity–tradition binary is by endorsing a deficit perspective of non-Western cultures, framing them as static, oppressive, and the main contributing factor to harmful practices. This eclipses how these same practices – like female genital surgeries or marriages involving minors – often exist in the global North too, yet are rarely subject to the same levels of moral outrage or legal condemnation (Bessa Citation2019). The deficit perspective also ignores how structural factors can underpin ‘cultural’ practices, and that family members act in what they perceive to be the best interests of girls and wider family or household given their social context. This framing also ignores the dynamic nature of culture, and the potential for local resources and actors to contribute to positive shifts in social norms (Newman 2023). Indeed, many organisations aim to indiscriminately criminalise culturally sanctioned practices which have wide support, like FGC. Strategies then force compliance to laws, or pit community members who oppose/support the practice against each another – particularly youth against elders (Newman Citation2021). These strategies contribute to anxiety, stigma, accusations of cultural imperialism, community resistance, and inter-generational conflict. They undermine social cohesion, and push these practices underground – making girls more vulnerable (Newman Citation2023a; Shell-Duncan Citation2008).

Alternatively, development organisations pronounce that it is important to take culture into account, but only do so in superficial ways – continuing to use theories and models rooted in Euro-North-American values, norms, and worldview (Hindmarch and Hillier Citation2022; Kagawa-Singer et al. Citation2016). For instance, dominant models of psychology used in global health – including psychology of adolescence – were born in the US and reflect individualist values which prioritise autonomy, self-interest, individual decision-making, and peer relationships (Hindmarch and Hillier Citation2022; Nsamenang Citation2008). Many decolonial scholars from the global South have therefore argued that global health programmes suffer from a lack of ‘cultural congruity’ (Airhihenbuwa Citation1995). They fail to appreciate or affirm Indigenous conceptualisations of adolescence which emphasise the supportive role of adults and elders in adolescents’ lives, inter-generational communication, adolescent moral or spiritual development, acquisition of cultural identity and values, and interconnectedness and interdependency with peers and family members (Kagitcibasi Citation2017).

In contrast to a deficit or culturally ignorant approach, GMP is inspired by a decolonial ‘assets-based approach’ to culture and community resources (Aubel and Sihalathavong Citation2001; Trickett et al. Citation2011). This involves recognising that communities and their cultures – which include norms, collectivist values, and the roles and influence of key individuals in family and community decision-making – contribute significant assets to the development process (Aubel Citation2014). However, GMP recognises that not all cultural values and norms have positive outcomes. Hence, GMP uses an approach based on ‘cultural renewal’, which frames culture as a dynamic set of values and norms which, through participatory involvement of local peoples in the process, can be reformulated and renewed (White and Nair Citation1994).

How to promote girls’ development? From individualistic girl-centric strategies to grandmother-inclusive collective social norms change

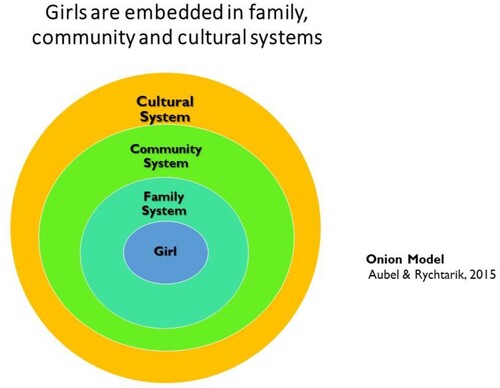

The final form of coloniality that we identify in the field of adolescent health in the global South is how most development interventions focus their resources and activities on girls. Girl-centric approches are influenced by epidemiology, behavioural sciences, and linear models of health communication that target ‘risk groups’, while ignoring how these groups are embedded in wider social systems, hence failing to address the structures or individuals who contribute to that risk (Aubel and Sihalathavong Citation2001; Trickett et al. Citation2011) (see ).

Figure 1. Onion model: girls are embedded in family, community, and cultural systems.

Source: Aubel and Rychtarik (Citation2015, 12).

This focus is also informed by ‘Girl Effect’ discourse, dominant in gender and development since the 1990s, which frames adolescent girls as the greatest potential change agents in their communities, and the solution to poverty and ‘harmful traditional practices’. Postcolonial feminists have argued that Girl Effect discourse is problematic because it overlooks the structural causes of practices like FGC and CEFMU in favour of simplistic explanations which support linear change strategies; it frames the family as the focal site of oppression; and promotes ‘girls’ empowerment’ according to Euro-North-American-centric and neoliberal values like ‘freedom, individual authenticity and self-realisation’ (Bessa Citation2019, 1944; Giaquinta Citation2016; Koffman and Gill Citation2013). The practical operationalisation of Girl Effect discourse is frequently ‘girls empowerment approaches’ (GEAs) which aim to provide adolescent girls with knowledge, skills, and networks to challenge their parents and elders on FGC or CEFMU (Bessa Citation2019). However, empirical evidence shows that GEAs often increase girls’ knowledge of oppressive structures, but does not shift the authority structures that would enable them to change the behaviour of those around them – a situation that Thais Bessa (Citation2019) terms ‘informed powerlessness’. GEAs also push girls into confrontational relationships with their families, often rendering them more vulnerable by triggering inter-generational conflict and adult resistance (Newman Citation2021).

In contrast to these linear and individualistic models of behaviour change, GMP’s approach reflects the work of systems theorists who assert that programmes are more effective when they focus on promoting changes in social norms – understood in collective terms – which can only come about if a community, especially its most authoritative members, comes to a consensus in favour of that change (Figueroa et al. Citation2002; Foster-Fishman and Behrens Citation2007). Central to a systemic approach is the necessity to understand the complexity of the system, particularly family and community decision-making processes and power dynamics (Aubel, Martin, and Cunningham Citation2021). Unfortunately, most community-level FGC and CEFMU interventions are based on Euro-North-American-centric assumptions about the relative authority of different actors, typically focusing on the nuclear family and male community or religious leaders. Such organisations display systemic ‘grandmother exclusionary-bias’ (Newman Citation2023a, Citation2023b), namely side-lining grandmothers as change agents in favour of adolescent girls, younger women, men and boys, and male religious leaders. Grandmother-exclusionary bias stems from sexist and ageist biases rooted in Euro-North-American-centric modernity that ignores the important social roles played by grandmothers in ‘non-Western’ societies, and frames them as passive, conservative, and unwilling or unable to change their views (Lipman Citation2013; Varley Citation2013).

In contrast, family systems theorists show that the nuclear family is a recent phenomenon associated with Western, industrialised, and urban contexts (Aubel, Martin, and Cunningham Citation2021). In the ‘non-Western’ world, family systems usually involve multi-generational families and collective child-rearing; collective decision-making on important family issues; a hierarchy of authority based on biological age, seniority in kinship structures, and experience; the role of respected elders in teaching younger generations; and social norms that are set by elders (Aubel and Chibanda Citation2022). Moreover, ‘non-Western’ societies are often characterised by gender-specific activities and roles. Women wield significant authority in ‘feminine’ spheres and, particularly as they age, can trump male authority in household decision-making (Amadiume Citation1987; Nnaemeka Citation2005; Oyěwùmí Citation2002). Extensive empirical evidence shows that, because of the intersection of age hierarchies and gender in ‘non-Western’ contexts, important roles are played by grandmothers in the spheres of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and children’s health in Latin America, Asia, Africa, and Indigenous communities in contexts of settler colonialism (Aubel Citation2014). Indeed, in most contexts where FGC is practised, grandmothers wield principal authority over key decisions and social norms (Newman Citation2023a, Citation2023b).

Reflecting systems thinking, to inform GHD programme development, GMP conducted formative research on adolescent development within family systems in southern Senegal which identified the influential roles that grandmothers played related to adolescent socialisation and health, including FGC, and the authority they wielded over social norms relating to those issues (Aubel and Lombardo Citation2006b). That research, and extensive input from community actors since, supports GMP’s recognition of grandmothers as a powerful social resource. This is the basis for GMP’s ‘grandmother-inclusive’ approach where grandmothers are involved as change agents alongside other influential authorities in families and communities (Aubel Citation2022). However, GMP recognises that relationships within communities are not equitable because of age and gender hierarchies, so GHD also uses techniques from community development and community psychology to reduce power inequalities as the foundation for collaborative and consensual processes of community-driven change (Aubel Citation2022).

From theory to praxis: key activities of the GHD programme

Building on the insights from these diverse paradigms, GMP designed a series of interactive community activities to strengthen community cohesion, and catalyse dialogue for consensus building for change to support adolescent girls’ health and well-being. Below we unpack how these activities central to the GHD programme have evolved over time based on input from community participants and other challenges identified by GMP.

Inter-generational forums with community leaders

When GHD began in Vélingara in 2009, GMP documented limited communication between elders, parents, and children, and between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law. Men had little regard for women’s opinions and discussion of sensitive topics – like FGC and adolescent pregnancy – was considered taboo. These power inequalities, and lack of communication, were a barrier to the dialogue, community cohesion, and consensus building needed for changes to support GHD objectives (Aubel and Lombardo Citation2006a).

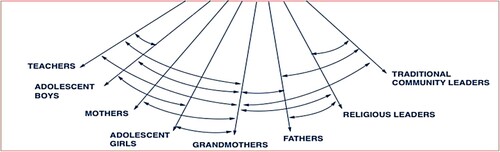

Therefore, GMP designed a series of inter-generational forums to strengthen communication between elders and parents. Participants in the forums were community leaders – namely men and women representing adults of reproductive age, and elders. In addition, others who could influence girls’ well-being were involved, e.g. health workers, teachers, imams, local musicians, and sages. After the forums, the community leaders were encouraged – with accompaniment by facilitators – to convene their peer groups, share the content of the discussions with them, and seek their feedback (see ).

Figure 2. Inter-generational forum: plenary session, Médina Diambére, Senegal. Photo credit: Judi Aubel.

After the first round of inter-generational forums, Mamadou identified two limitations. First, many leaders who participated were not committed leaders, nor were they trusted and respected by others. Hence, GMP organised discussions to support community members in identifying priority leadership characteristics – charisma, attentive listening, respect for contrasting views – and to support a more democratic process of leader selection. Second, Mamadou realised that it was important and possible to also involve adolescents in the forums so that their views could be better represented, and to model good practice in terms of respectful listening between people of different ages and genders (see ).

Figure 3. The girls’ holistic development community dialogue for building consensus, which illustrates the relationships and communication channels reinforced by GMP.

Source: Passages Project (Citation2021, 32).

In the current iteration of the inter-generational forums, the topics for discussion between three generations of leaders from a single village mainly relate to girls’ education, CEFMU, adolescent pregnancy, inter-generational communication, and community solidarity. Each topic is discussed within peer groups organised by age and gender, followed by a plenary session. Attention is paid to acknowledge grandmothers and encourage their participation as they are rarely involved in community meetings organised by other development programmes. These two-day forums allow for phased introduction of dialogue on GHD issues between categories of persons not accustomed to discussing complex and sensitive issues together. The forums constitute the foundation for strengthening community connectedness, and for initiating the process of community consensus building for defining actions to support girls (Musoko et al. Citation2012, 32–4). Indeed, GMP found that community members spontaneously started using the techniques of democratic communication and listening modelled in the forums within their own households (Lulli Citation2020).

Above all, it was the importance and value of intergenerational communication that motivated people to take part in GMP activities, because it’s something elders used to do, and it strengthened solidarity within the community. Since people stopped doing that, solidarity had disappeared. There was no longer any social cohesion within the family, within the community. And yet, communication between the generations, discussions between husbands and wives, between young girls and their grandmothers, between elders and young people, is really very important and only strengthens solidarity. Solidarity enables development. – Oustaz Oubukande. (Saavedra Citation2022, 26)

Before, men made decisions alone, they did whatever they wanted. Then they would come and tell you ‘I’ve done this, I’ve done that.’ But that’s no longer the case. We are involved in family consultations about everything that concerns keeping the family running smoothly; when it comes to food and other issues, our husbands involve and consult with us. Now a husband will ask you, ‘I want to do this and that, that’s my idea, what do you think?’ And you, you say what you think about it. Then you look for a good solution together. – Woman of reproductive age from Saré Yira. (Lulli Citation2020, 7)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aonJ0UunhMk (Link to Grandmother Project, ‘Girls’ Holisitic Development Program’, 14 December 2021, accessed 6 June 2023)

‘Days in Praise of Grandmothers’ and ‘Days of Dialogue and Solidarity’

In order to facilitate cultural renewal, all of GMP’s activities involve affirmation of cherished positive cultural values, knowledges, and practices. To do this, GMP consulted with local communities to develop two activities which build alliances between villages in the region, in which community members play a key role in defining the content and format (Aubel Citation2022). ‘Days in Praise of Grandmothers’ bring together grandmother leaders from several neighbouring villages, as well as adolescent girls and other key actors from the host village, to celebrate the role of grandmothers, their experience and knowledge of cultural values and practices, and commitment to promoting children’s health and well-being. Meanwhile, ‘Days of Dialogue and Solidarity’ work towards building a critical mass of elders and adults who can build a supportive environment around girls. It includes grandmother leaders, community elders, imams, and other male leaders from adjacent villages who meet to discuss their respective roles in promoting GHD, particularly ending FGC. Local imams also share Islamic teachings on girls’ health, as well as tolerance and solidarity. Adolescent girls were originally invited to ‘Days of Dialogue and Solidarity’, but are no longer as they were not as comfortable participating there as in the inter-generational forums and ‘Days in Praise of Grandmothers’.

GMP always affirms cultural knowledge and values, and follows cultural protocols during community activities – like singing culturally affirmative songs composed by local musicians, opening and closing with prayer, or distributing kola nuts to elders which is a customary sign of respect (Saavedra Citation2022). Cultural affirmation is both an ends in itself, based on feminist and decolonial principles, and the means to create a foundation for community-led abandonment of harmful cultural traditions (Musoko et al. Citation2012, 36–9). A recent qualitative study found that GMP’s culturally grounded activities, and their personnel’s sincere respect for cultural values and customs, are major reasons for high levels of community engagement with the GHD programme (Saavedra Citation2022). The following video ‘A Song in Praise of Grandmothers’, features a performance of such a song, ‘Maamaa Jaara’, composed by Samba Diao, a teacher and musician from Vélingara. It has been adapted and performed here by the choir of the Catholic Church in Vélingara. It is a community favourite, and translation of the Pulaar lyrics are as follows:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m_QGH_emnE8 (Link to Grandmother Project, ‘A Song in Praise of Grandmothers – Senegal’, 3 February 2022, accessed 6 June 2023)

Any action you want to take must be contextualized [grounded in local culture]. If you don’t contextualize it, you miss the point. When we realized that excision [FGC] was a problem, we had to tackle it. Today, who is the custodian of this cultural practice? It’s the grandmothers – who had been marginalized. Grandmothers shouldn’t be involved [in a programme on FGC] to be goaded into doing what other people want – they should be involved because it is their right. You can’t imagine the value of their experience in this area, because you can’t excise a child here, no matter how much power the head of the family has in the family, without involving the grandmother. It’s unthinkable. – Mamadou Ba, cultural expert/sage. (Saavedra Citation2022, 30)

Other participatory learning activities

Beyond the inter-generational forums, GMP organises more-frequent participatory learning activities in both rural and urban areas to strengthen community members’ relationships within and across genders and generations, primarily with women and girls of three generations. These sessions are not leader-specific and involve as many members of the relevant peer groups as possible. Women and girl forums bring together adolescent girls, mothers, grandmothers, and female teacher-facilitators to develop and reinforce cross-generational relationships and alliances of women to support girls during adolescence. They involve: increasing girls’ confidence to discuss their priorities and challenges, such as forced marriage, lack of parental support for their schooling, onerous domestic workloads, and corporal punishment; introducing participants to biomedical understandings of puberty and reproduction; and strengthening the inter-generational transmission of cherished cultural, spiritual, and moral values. GMP also organises participatory learning activities with adolescent boys, fathers, grandfathers, and male religious leaders to promote positive and equitable masculinities that support GHD objectives. Given resource limitations, there are more sessions with girls and women than men and boys.

In the following video, an adolescent girl explains what she has learned from the grandmothers, and the beneficial changes that inter-generational activities have had on adolescent girls’ well-being.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RyPsznpL5sA (Link to Grandmother Project, ‘A Girl Talks Grandmothers … ’, 26 July 2019, accessed 6 June 2023)

Before, there were more teenage pregnancies and grandmothers didn’t give us advice. When we were with boys, suddenly someone would get pregnant. But from the discussions that the grandmothers have had with us, we understand that we don’t have to agree to everything that boys suggest. – Adolescent girls focus group, Diamweli. (Lulli Citation2020, 8)

Now they hold each other in esteem. You can hear the boys talking together saying, ‘We need to let the girls continue their studies. They’re our sisters, we’re their family, we’re in the same village, we mustn’t get the girls pregnant. – Grandmother focus group, Saré Sankoulé. (Lulli Citation2020, 8)

Leadership training with grandmothers and adolescent girls

A few years ago, recognising the openness and potential of the grandmother leaders, Judi and Mamadou decided that they should receive more dedicated training to strengthen their knowledge and collective agency to support GHD objectives. GMP also observed a worrying trend whereby individualistic, girl-centric ‘girls empowerment’ activities undertaken by other NGOs in the region were leading to a breakdown in relationships between girls and their families, to the detriment of the former’s well-being. Therefore, as of 2018, GMP organises two series of leadership training sessions, one with grandmothers, and one with adolescent girls with the involvement of mothers and grandmothers. During four weekends of participatory workshops, they learn about SRH; positive cultural values, rituals, and practices; and the skills to respect and listen to each other’s perspectives. The leadership training works on strengthening relationships between three generations of women, and supporting them to exercise individual, collective, and proxy agency – with the latter entailing girls approaching more powerful allies (namely grandmothers) to advocate on their behalf within traditional authority structures (Bandura Citation2001). Evidence from interviews (Aubel Citation2020) and case studies (Newman Citation2021) shows that the training has had a considerable impact on girls’ and grandmothers’ abilities to promote the interests of adolescent girls, as well as other community-defined priorities, for instance by preventing cases of CEFMU (see ).

Before, we were very limited in all domains because we didn’t dare to give our opinion at home, we didn’t dare to talk with women of reproductive age, men, or to get close with our granddaughters, because people considered us to be witches. But now we’re determined; we’re not isolated; we can express ourselves in front of an audience; we give our opinions when it’s called for; we talk with people of all generations. – Grandmother focus group, Koumera (Lulli Citation2020, 4) ()

Grandmother–teacher workshops

From the beginning, a complementary component of the GHD programme has been to strengthen collaboration between school and community actors – especially grandmothers – to prevent CEFMU, adolescent pregnancy, and premature school-leaving. GMP facilitates grandmother–teacher workshops which have three objectives: strengthening relationships between schools and local communities which had broken down before the project began; involving teachers to meet programme objectives; and affirming cultural values, Indigenous knowledge and oral traditions, and the pedagogical role of grandmothers by involving grandmothers as teachers in classroom activities. Over the years, with teachers and key community actors, GMP has developed a number of resources to support teachers in this endeavour including designing bilingual booklets in French and local languages, and an interactive card game (see the video ‘The Transmission of Cultural Values in Schools’). GMP commissioned Anneke and Hamidou Soukouna, a Senegalese pedagogy expert, to research the programme’s school dimension, which found that the strategy had contributed to decreasing girls’ premature school-leaving, adolescent pregnancy, and CEFMU (Soukouna and Newman Citation2015). The study also found that some teachers struggled to use the tools, which prompted the design of a pedagogical guide to support them (Newman and Soukouna Citation2017).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SThg0pAIyxs (Link to Grandmother Project, ‘Les transmissions des valeurs culturelles à l’école’ [‘The Transmission of Cultural Values in Schools’], 11 March 2022, accessed 6 June 2023)

Limitations and challenges of GMP’s approach

Judi and Mamadou acknowledge that the GHD programme still has some limitations. First, in order to bring about shifts in behaviour at the collective level, GMP prioritises working with informal and formal leaders of different peer groups by age and gender. Although GMP works with community members to choose individuals who can convene their peer group and solicit their views, choice of leaders can reflect intersectional privileges, particularly socioeconomic status, caste, or lineage (e.g. over-representation of leaders hailing from the village chief’s family). Adolescent girl leaders tend to be in school, as those who have dropped out prematurely are much less confident. As a result, when community leaders convene their peer groups to discuss shared priorities, these priorities might reflect the leaders’ privileges. Second, participation of community members in programme activities is restricted by their schedules, which again reflects gender and socioeconomic status. Adolescent girls and mothers have more domestic responsibilities than grandmothers, although poorer grandmothers can also struggle to find free time. Similarly, men are much less present in the village than women, whether working in the fields, or in other towns or countries, on a short- or long-term basis. These challenges – of more privileged community members participating more frequently, and being over-represented in leadership roles – are widely recognised within the participatory development literature, and are difficult to overcome entirely (Kang Citation2011).

In addition, GMP experiences several challenges related to the structural dynamics and funding regimes of development and global health – which have been documented elsewhere (Kang Citation2011). First, the programme relies upon building and maintaining strong relationships of trust and dialogue between GMP staff and community members, beyond a narrow focus on behaviour change objectives. Second, GMP struggles to identify facilitators who can interact with communities in a respectful, humble, listening mode. They have found that most local community development workers have been trained in directive methods of social and behaviour change, and struggle to listen and facilitate in a non-directive way. To address this, GMP employs all potential new facilitators on a fixed-term basis, during which they observe their interactions with community members. Around 50–65 per cent are ultimately recruited long term, and receive further training in facilitation skills.

More broadly, the fact that GMP’s approach diverges so significantly from the girl-centric norm in the field of adolescent health means that it struggles to obtain funding for implementation and evaluation from larger donors, and often relies on smaller one-off grants of a year’s duration from philanthropic organisations. More specifically, when donors in this field fund programmes, they privilege those whose approaches are supported by meta-evaluations of previous programmes evaluated by ‘scientific’ methods – whose flaws we unpacked above. This creates a closed circle of evidence production, as only programmes adhering to dominant development paradigms get funded and evaluated in the first place. Furthermore, these evaluations and meta-evaluations only measure outcomes of interest to donors and organisations. They rarely measure unintended negative consequences, and disregard the longer-term impacts of their strategies on community dynamics.

Conclusion

We have argued that coloniality permeates global health and gender and development, including interventions to improve adolescent girls’ health and well-being. It is evident in universalist and instrumentalist approaches to the behaviour change of ‘target’ communities which reflect theories and models from academic disciplines grounded in Euro-North-American-centric values and perspectives. These approaches include top-down imposed objectives and pathways to change; individualist values and worldview; sexist, ageist, and modernist biases; and ignorance or denigration of local cultural values, resources, and family and community dynamics. In contrast, we describe GMP’s GHD programme in Senegal as a decolonial alternative which is informed by theories and methodologies from participatory and community development; anthropology; family and community systems approaches to health-related behaviour; community, cultural, and Indigenous psychology; and transformative learning and adult education.

Independent evaluations have measured the programme’s outcomes according to donor objectives, showing that it has contributed to collective shifts in social norms underpinning CEFMU, FGC, adolescent pregnancy, and premature school-leaving, and has stimulated high levels of community engagement in favour of creating a supportive environment around adolescent girls. However, GMP has conducted and commissioned research to measure outcomes of priority to community members themselves – namely improved inter-generational relationships, communication, social cohesion, and capacity to mobilise collectively independently of development actors – as well as the processes that have led to these outcomes. Their research suggests that their approach contributes to these changes because it presents an alternative decolonial vision of, and method of achieving, adolescent girls’ development. Key characteristics of the approach are that it is informed by systems thinking; reflects an intimate understanding of power dynamics in families and communities; is culturally affirmative; is based on an assets-based view of cultural and community resources, rather than a deficit perspective; and is rooted in reinforcing community capacity and consensus for change towards locally defined objectives and solutions.

However, GMP faces a number of constraints to implementation, which point to broader structural barriers to the implementation of decolonial programmes in the field of adolescent health. These include the lack of funding available for programme activities focused on cultural affirmation and relationship building with communities; the lack of local facilitators with the skills and attributes required for non-directive facilitation and respectful relationship building; and the lack of funding for activities which do not fit into dominant development paradigms focused on narrow outcomes and aggressive behaviour change approaches – despite extensive evidence that these paradigms fail to address community priorities and often cause harm and resistance.

To address these barriers, we therefore propose the following areas which could inform collective strategising among individuals working to decolonise gender and development and global health. First, organisations and donors ought to consider a broader range of evidence which would involve evaluating the ethics as well as efficacy of programme approaches. These should include anthropological ethnographies on cultural dynamics in local communities; postcolonial and decolonial critiques of the harms caused by Euro-North-American-centric models used in adolescent health; and alternative paradigms, like systems thinking, community development, and Indigenous approaches, that promote collective community empowerment instead of linear, directive, and individualistic approaches to social and behaviour change. Second, organisations and donors must recognise that cultural affirmation, and strong relationships within communities and between community and development actors, are central to decolonial community development processes. Project funding models need to evolve to support such activities. Finally, more resources must be invested in universities and institutes in the global South to train practitioners in the attitudes and skills necessary to design and implement programmes informed by decolonial principles. This investment must be separate from project-related funding focused on narrow, short-term objectives defined by actors outside local communities. The long-term end goal needs to be strengthening communities’ own capacity for collective mobilisation to realise independence from the constraints and power inequalities inherent in external development intervention.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the elders of Vélingara past, present, and future for their wisdom, and investment of energy, for preserving and promoting the culture of the Fouladou, and working tirelessly towards the well-being and collective empowerment of their communities. We are also grateful to Montserrat Algarabel and Shivani Satija for their feedback on previous drafts.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anneke Newman

Anneke Newman is a Senior Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Ghent, Belgium. She has a BA in Human Sciences (University of Oxford), MA in Gender and Development (Institute of Development Studies), and MSc in Cross-cultural Research Methods and PhD in Anthropology (University of Sussex). Postal address: Institut de Sociologie, Avenue Jeanne 44 - CP 124, B-1000 Bruxelles, Belgium. Email: [email protected]

Judi Aubel

Judi Aubel is the director and founder of The Grandmother Project – Change Through Culture. She has a BA in International Relations (UCLA), MA in Adult Education (Arizona State University), Masters in Public Health (University of North Carolina), and PhD in Anthropology and Education (University of Bristol).

Mamadou Coulibaly

Mamadou Coulibaly is the project co-ordinator of the GHD programme. He trained as a teacher and community development facilitator and has an MBA in Project Management (Institut Supérieur de Management – Thiès).

References

- Airhihenbuwa, Collins O. (1995) Health and Culture: Beyond the Western Paradigm, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Amadiume, Ifi (1987) Male Daughters, Female Husbands: Gender and Sex in an African Society, London: Zed Press.

- Aubel, Judi (2014) Involving Grandmothers to Promote Child Nutrition, Health and Development: A Guide for Programme Managers and Planners, Toronto: Grandmother Project - Change Through Culture and World Vision International.

- Aubel, Judi (2017) Stories-without-an-Ending: An Adult Education Tool for Dialogue and Social Change, Velingara: Grandmother Project - Change Through Culture.

- Aubel, Judi (2020) ‘Empowering grandmother leaders to support and protect girls: An experience from Senegal’, Practice Insights 15: 12–14.

- Aubel, Judi (2022) ‘Promoting community-driven change in family and community systems to support girls’ holistic development in Senegal’, in Geraldine Palmer, Todd Rogers, Judah Viola, and Maronica Engel (eds.) Case Studies in Community Psychology Practice: A Global Lens, 64–86. https://press.rebus.community/communitypsychologypractice/.

- Aubel, Judi and Dixon Chibanda (2022) ‘The neglect of culture in global health research and practice’, BMJ Global Health 7: e009914. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009914.

- Aubel, Judi and Bridget Lombardo (2006a) Dialogue Between Generations: A Participatory Approach to Promote Reflection and Action Against Female Genital Mutilation, Vélingara: Grandmother Project - Change Through Culture.

- Aubel, Judi and Bridget Lombardo (2006b) Les Valeurs Culturelles, l’éducation Des Jeunes Filles et l’excision: Une Étude Qualitative Communautaire, Vélingara, Sénégal, Vélingara: World Vision Senegal.

- Aubel, Judi and Alyssa Rychtarik (2015) Focus on Families and Culture: A Guide for Conducting a Participatory Assessment on Maternal and Child Nutrition, Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development.

- Aubel, Judi and Douangchan Sihalathavong (2001) ‘Participatory communication to strengthen the role of grandmothers in child health: An alternative paradigm for health education and health communication’, Journal of International Communication 7(2): 76–97. doi:10.1080/13216597.2001.9751911.

- Aubel, Judi, Stephanie L. Martin, and Kenda Cunningham (2021) ‘Introduction: A family systems approach to promote maternal, child and adolescent nutrition’, Maternal and Child Nutrition 17(S1): 1–9. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009914.

- Bandura, Albert (2001) ‘Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective’, Annual Review of Psychology 52: 1–26.

- Bessa, Thais (2019) ‘Informed powerlessness: child marriage interventions and third world girlhood discourses’, Third World Quarterly 40(11): 1941–1956. doi:10.1080/01436597.2019.1626229.

- Bialostocka, Olga (2020) ‘Choosing heaven: negotiating modernity in diverse social orders’, African Development XLV(3): 121–154.

- Borda, Orlando Fals (1999) ‘Kinsey dialogue series #1: The origins and challenges of participatory action research’, Participatory Research & Practice 10: 1–30.

- Diallo, Khadidiatou (2019) The Role of Grandmother Leaders in the Process of Female Genital Mutilation Abandonment in Kandia, Vélingara, Senegal, Vélingara: The Grandmother Project - Change Through Culture.

- Esho, Tammary, Steven Van Wolputte, and Paul Enzlin (2011) ‘The socio-cultural-symbolic nexus in the perpetuation of female genital cutting: A critical review of existing discourses’, Afrika Focus 24(2): 53–70. doi:10.21825/af.v24i2.4997.

- Figueroa, Maria Elena, D. Lawrence Kincaid, Manju Rani, and Gary Lewis (2002) Communication for Social Change: An Integrated Model for Measuring the Process and Its Outcomes, New York, NY: The Rockefeller Foundation and Johns Hopkins University Center for Communication Programs.

- Foster-Fishman, Pennie G., and Teresa R. Behrens (2007) ‘Systems change reborn: Rethinking our theories, methods, and efforts in human services reform and community-based change’, American Journal of Community Psychology 39: 191–196.

- Foster-Fishman, Pennie G., Branda Nowell, and Huilan Yang (2007) ‘Putting the system back into systems change: A framework for understanding and changing organizational and community systems’, American Journal of Community Psychology 39: 197–215. doi:10.1007/s10464-007-9109-0.

- Gallagher, Kaia M., Douglas V. Easterling, and Dora G. Lodwick (2003) Promoting Health at the Community Level, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Giaquinta, Belén (2016) ‘Silenced subjectivities and missed representations: Unpacking the gaps of the international child marriage discourse’, Master in Development Studies, Institute of Social Studies, The Hague, The Netherlands.

- GMP (2015) Embracing Indigenous Knowledge and Cultural Values to Meet Education For All: Lessons from Senegal, Velingara: Grandmother Project - Change Through Culture.

- Grosfoguel, Ramón (2007) ‘The epistemic decolonial turn’, Cultural Studies 21(2–3): 211–223.

- Hindmarch, Suzanne and Sean Hillier (2022) ‘Reimagining global health: from decolonisation to indigenization’, Global Public Health, 1–12. doi:10.1080/17441692.2022.2092183.

- Janes, Craig R and Kitty K. Corbett (2009) ‘Anthropology and global health’, Annual Review of Anthropology 38: 167–183. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-091908-164314.

- Kagawa-Singer, Marjorie, William D. Dressler, and Sheba M. George (2016) ‘Culture: The missing link in health research’, Social Science & Medicine 170: 237–246.

- Kagitcibasi, Cigdem (2017) Family, Self and Human Development Across Cultures: Theory and Applications. Second Edition, New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Kang, Jiyoung (2011) ‘Understanding non-governmental organizations in community development: strengths, limitations and suggestions’, International Social Work 54(2): 223–237.

- Koffman, Ofra and Rosalind Gill (2013) ‘“The revolution will be led by a 12-year-old girl”: Girl power and global biopolitics’, Feminist Review 105: 83–102. doi:10.1057/fr.2013.16.

- Kohli, Anjalee, Bryan Shaw, Mathilde Guntzberger, Judi Aubel, Mamadou Coulibaly, and Susan Igras (2021) ‘Transforming social norms to improve girl-child health and well-being: A realist evaluation of the girls’ holistic development program in rural Senegal’, Reproductive Health 18(248): 1–14. doi:10.1186/s12978-021-01295-5.

- Kothari, Uma (2006) ‘Critiquing ‘race’ and racism in development discourse and practice’, Progress in Development Studies 6(1): 1–7.

- Lipman, Valerie (2013) ‘The invisibility of older women in international development’ in Sally-Marie Bamford and Jessica Watson (eds.) A Compendium of Essays: Has the Sisterhood Forgotten Older Women? London: International Longevity Centre UK, 111–113.

- Lugones, María (2007) ‘Heterosexualism and the colonial/modern gender system’, Hypatia 22(1): 186–209.

- Lulli, Francesca (2020) Changes in Gender Relations and in the Status of Women, Vélingara: The Grandmother Project - Change Through Culture.

- Musoko, Assia, Cristiana Saou Scoppa, Erma Manoncourt, and Judi Aubel (2012) Girls and Grandmothers Hand-in-Hand: Dialogue Between Generations for Community Change, Rome: World Vision and Grandmother Project - Change Through Culture.

- Nagar, Richa, and Amanda Lock Swarr (2010) ‘Introduction: Theorizing transnational feminist praxis’ in Amanda Lock Swarr and Richa Nagar (eds.) Critical Transnational Feminist Praxis, New York, NY: State University of New York Press, 1-20.

- Newman, Anneke (2021) ‘“If your feminism isn’t intergenerational, it not feminism: From “girl-centred” to “grandmother-inclusive” approaches to ending child marriage, teen pregnancy and FGC in Senegal’, Conference paper presented at the Development Studies Association conference, University of East Anglia/online, 1st July 2021.

- Newman, Anneke (2023a) ‘Decolonising social norms change: From “grandmother-exclusive bias” to “grandmother-inclusive” approaches’, Third World Quarterly 44(6): 1230–1248. doi:10.1080/01436597.2023.2178408.

- Newman, Anneke (2023b) ‘Grandmother-inclusive intergenerational approaches: The missing piece of the puzzle for ending FGM/C by 2030?’, Frontiers in Sociology: Medical Sociology 8, doi:10.3389/fsoc.2023.1196068.

- Newman, Anneke and Hamidou Soukouna (2017) Guide Pédagogique: L’intégration Des Valeurs et Connaissances Culturelles à l’école, Vélingara: Grandmother Project - Change Through Culture.

- Nnaemeka, Obioma (2005) ‘“Mapping African feminisms”, adapted version of “introduction: Reading the rainbow”, from sisterhood, feminisms and power: From Africa to the diaspora’, in Andrea Cornwall (ed.) Readings in Gender in Africa, London: James Currey, 31–41.

- Nsamenang, A. Bame (2008) ‘Cultural and human development’, International Journal of Psychology 43(2): 73–77.

- Ortega, Mariana (2017) ‘Decolonial woes and practices of un-knowing’, The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 31(3): 504–516.

- Oyěwùmí, Oyèrónké (2002) ‘Conceptualising gender: The Eurocentric foundations of feminist concepts and the challenge of African epistemologies’, Jenda: A Journal of Culture and African Woman Studies 2(1): 1–5.

- Pant, Ichhya, Sonal Khosla, Jasmine T. Lama, Vidhya Shanker, Mohammed AlKhaldi, Aisha El-Basuoni, Beth Michel, Ifeanyi Khalil Bitar, and Nsofor McWilliams (2022) ‘Decolonising global health evaluation: synthesis from a scoping review’, PLOS Global Public Health 2(11): e0000306. doi:10.1371/journal.pgph.0000306.

- Passages Project (2021) ‘Toward shared meaning: A challenge paper on SBC and social norms’, Washington, DC: Institute for Reproductive Health, Georgetown University for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

- Quijano, Aníbal (2007) ‘Coloniality and modernity/rationality’, Cultural Studies 21(2–3): 168–178.

- Saavedra, Rodrigo Quiroz (2022) L’adaptation Culturelle Du Programme Développement Holistique Des Filles et Sa Contribution à l’engagement Communautaire: Une Recherche Participative, Vélingara: The Grandmother Project – Change Through Culture.

- Shaw, Bryan, Anjalee Kohli, and Susan Igras (2020) Grandmother Project – Change Through Culture: Girls’ Holistic Development Program Quantitative Research Report, Washington, DC: Institute for Reproductive Health, Georgetown University with the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

- Shell-Duncan, Bettina (2008) ‘From health to human rights: Female genital cutting and the politics of intervention’, American Anthropologist 110(2): 225–236.

- Soukouna, Hamidou and Anneke Newman (2015) La Rencontre Des Deux Savoirs: Revue de La Stratègie d’intégration Des Valeurs Culturelles à l’école, Vélingara: Grandmother Project – Change Through Culture.

- Taylor, Edward W. and Patricia Cranton (2012) The Handbook of Transformative Learning: Theory, Research and Practice, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Trickett, Edison, Sarah Beehler, Charles Deutsch, Lawrence W. Green, Penelope Hawe, Kenneth McLeroy, Robin Lin Miller et al. (2011) ‘Advancing the science of community-level interventions’, American Journal of Public Health 101(8): 1410–1419.

- Varley, Ann (2013) ‘Feminism’s pale shadows: Older women, gender and development’ in Sally-Marie Bamford and Jessica Watson (eds.) A Compendium of Essays: Has the Sisterhood Forgotten Older Women? London: International Longevity Centre UK, 114–116.

- Walsh, Catherine E. and Walter D. Mignolo (2018) ‘Introduction’ in Catherine E. Walsh and Walter D. Mignolo (eds.) On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis, Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, pp. 1–12.

- White, Shirley A., and Sadanandan K. Nair (1994) ‘Participatory development communication as cultural renewal’ in Shirley A. White, Sadanandan K. Nair, and Joseph Ascroft (eds.) Participatory Communication: Working for Change and Development. London: Sage Publications, 138–193.

- Whitehead, Margaret (2007) ‘A typology of actions to tackle social inequalities in health’, Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 61(6): 473–478.