1. Multilingual strategies in asylum and migration encounters: context and relevance

Owing to increasing societal heterogeneity, contemporary institutions and organisations routinely face clients whose hybrid linguistic repertoires pose a challenge to established communicative practices and resources. In response to the specific linguistic needs and resources of the participants in these contexts and to practical considerations such as time constraints or availability of language assistance, ‘standard’ multilingual practices (in which the use of professional interpreters or mediators is institutionally expected or required) are challenged by a range of alternative multilingual communication strategies. These multilingual strategies can be defined as communication support strategies that can be performed either by people (interpreters, language brokers, intercultural mediators), technologies (Google Translate, DeepL) or instruments (multilingual websites, brochures) (Rillof, Van Praet, and De Wilde Citation2014). While strategies, such as the use of a lingua franca, a non-professional interpreter (often a relative or acquaintance of the client) or translation technology are prevalent in many sites of cross-cultural multilingual contact, they remain largely under the radar and are given little if any consideration in language policy and practice (Antonini et al. Citation2017; Rudvin and Carfagnini Citation2020).

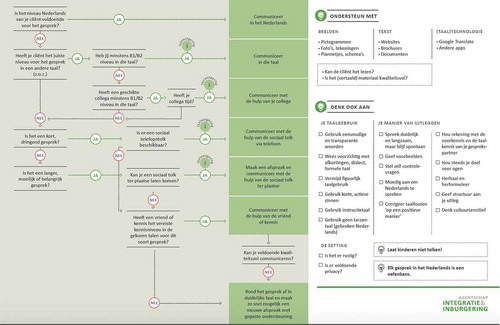

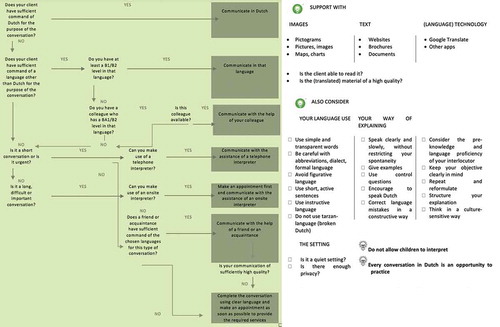

It is only recently that certain institutions and organisations have been calling for greater attention to be focused on more flexible multilingual practices, which, if applied under well-defined conditions, are being recognised as valuable alternatives for professional language support. In the Belgian context, for example, this trend is clearly reflected in the way in which multilingual service delivery is gradually being institutionalised by means of decision models that assist service providers in identifying the most appropriate language support strategy in the given service encounter. These decision models, which may vary from sector to sector, are developed in accordance with certain criteria, such as the language spoken and/or written (a more or lesser resourced language in the host community), specific vulnerabilities of the participants involved (unaccompanied minors, LGBT+ applicants, victims of sexual violence), the topic of the conversation (complex, sensitive content versus practical information) or financial constraints (Rillof, Van Praet, and De Wilde Citation2014). The basic principle is that not every type of encounter requires professional language services. In a first meeting with the service provider, for example, standard procedures can often easily be explained using visual material such as diagrams or flowcharts, and the use of a multilingual website will often be sufficient to get a straightforward practical message across. For long and difficult consultations, on the other hand, that may have serious implications for the people involved, it is advisable to use a professional interpreter (either remote or onsite). show an example of such a decision model as used by the Flemish Integration Agency (AgII). The introduction of this model goes hand in hand with training sessions for practitioners on how to communicate effectively using a decision model. Such training sessions are necessary because deciding which multilingual strategies and instruments work best in the given situation requires insight into the impact of communicative choices on the quality of service provision.

Figure 2. Communication matrix: how to communicate with my foreign language speaking clients? (Our translation of the diagram in English)

However, the use of carefully thought-out decision models for multilingual assistance is more the exception than the rule. In many public service settings, decisions about what multilingual strategy is most beneficial for service users in a given encounter continue to be taken on an ad hoc basis. While linguistic inclusiveness is considered an essential precondition for equal access, clear guidelines on how to implement an effective policy of multilingual inclusivity are not offered. The way in which complex issues of language and mediation are left to the individual – and usually linguistically untrained – service providers to be resolved raises a number of questions. The first of these is to what extent can service providers and users be expected to accurately assess each other’s levels of understanding? Note that the flowchart in leaves this assessment to the service provider, with specific criteria for their own proficiency (‘B1/B2 level’) but not for the client (‘sufficient command’). Other questions we might ask are: how do these levels of understanding fit the specific purposes of the interaction, what multilingual strategies and instruments do service providers and their clients prefer in the absence of professional language services, and what motivates their choice? Note that in , there is no flowchart for deciding on support tools. A further series of questions includes how effective and functional are the selected strategies? How can institutions and organisations handle multilingual service delivery in ways that benefit service providers and users alike? How are institutional practices shaped by language ideologies relating to migration and multilingualism? Note that the flowchart in advocates the use of Dutch when possible – ‘an opportunity to practice’ – in line with the agency’s goal of ‘integration’. This contrasts with other settings where professional interpreting is advocated, the possibility of second language learning is downplayed and alternation between languages discouraged (Angermeyer Citation2015). Such policies may be constrained further by ideologies of standardised languages that are viewed as discrete systems that proficient speakers need to master in full (note the rejection of ‘broken’ Dutch/”Tarzan language”Footnote1 in ).

From another point of view, critical voices are heard about how advisable it is to promote flexible multilingual practices as a supplement to professional language support, the main concerns including ethical issues (Monzó-Nebot and Wallace Citation2020), which may involve a potential decline in the quality of the language assistance provided as well as an unfair competition with professional services (for a more in-depth discussion we refer to Antonini, Cirillo, Rossato and Torresi’s introductory chapter on NPIT, 2017). This in turn raises the question of whether the current provision of professional interpreting services is able to meet the challenges of increasingly diverse and linguistically heterogeneous societies. Public institutions and local organisations across Europe are coping with an acute imbalance between supply and demand of certified interpreters, particularly in the lesser resourced languages (Bancroft Citation2015; Bergunde and Pöllabauer Citation2019). Since non-professional language assistance is cheap, and may be more easily accessible and instantly available, it is commonly used to meet part of this increasing demand, thereby compensating for the shortage in professional language services. According to Antonini et al., it is questionable ‘whether such demand would otherwise reorient towards remunerated professional services, putting up with the cost, time and effort necessary to contact them, or remain unfulfilled for lack of information or material resources’ (Citation2017, 9). In order to avoid an ‘all-or-nothing’ situation, where service users either receive professional language assistance or no language assistance at all (cf. Angermeyer Citation2015), these remaining gaps in the provision of language support must be addressed to prevent the most linguistically vulnerable clients, such as people with impairments or low literacy, or users of lesser resourced languages, from being entirely excluded from access to essential services. The ideal scenario for service users and providers alike would obviously be one in which professional interpreters are provided whenever needed. In a superdiverse and rapidly changing demographic environment, however, it becomes ever more challenging to provide interpreter training and certification for minority, signed and migrant languages. Bearing in mind the limitations this implies, and considering specific criteria, conditions and contexts of use, non-professional and ad hoc solutions can no longer be ignored if we want to prevent the most vulnerable people from falling out of the system.

2. Multilingual inclusivity in asylum and migration encounters

The main objective of this special issue is to consider professional interpreting practice in relation to other multilingual communication strategies in asylum and migration encounters and to examine the indexical and pragmatic effects of these strategies in the interactional process. Asylum and migration encounters comprise a whole array of contexts where migrants, asylum applicants and refugees meet with local authorities, service providers and citizens in the host community. These encounters range from asylum determination hearings to legal and medical counselling, or civic integration and community support initiatives.

While the multilingual challenges of asylum and migration encounters have been studied in various fields of language research, including interpreting studies, sociolinguistics, pragmatics, linguistic ethnography and intercultural communication, these different perspectives have barely been researched in connection to one another. The need for more cross-fertilisation of concepts, ideas and approaches is gradually being addressed by language scholars from related fields who transcend knowledge boundaries to learn from each other’s methods and paradigms in order to understand better the contemporary societal challenges they are facing. There is much to learn from translation and interpreting studies (TIS) when it comes to the dynamics of mediation and discourse representation in social interaction. Likewise, interpreting and translation scholars have learnt a lot from related disciplines, adopting conceptions of language that move beyond the totalising view of languages as separate and bounded entities. Globalisation yields hybrid linguistic practices that cannot be ignored. The integration of interactional sociolinguistic concepts such as linguistic mobility, repertoires and translanguaging has nourished increased awareness in TIS of the relevance of complementary forms of multilingual support, including but not limited to professional translation and interpreting practice.

Moving beyond traditional conceptions of professional language support involves mobilising the full repertoire of semiotic resources people can draw from, as ‘a collection of particular formats for using communicative means – “languages” in the traditional sense, language varieties (e.g. dialects or specific codes), modalities (visual, gestural, intonational, aesthetic), topically organised styles and genres’ (Blommaert Citation2006, 168). As recent studies on language mobility and migration have revealed, professional translation and interpreting can no longer be considered as the only legitimate forms of language support (Antonini et al. Citation2017). Instead, more flexible conceptions of linguistic support are called for, in which mediation is conceived as ‘a practice that facilitates inclusivity while recognizing difference’ (Tipton Citation2018, 168, citing also Cronin Citation2006; Polezzi Citation2012; Yildiz Citation2012). Adopting Tipton’s distinction between ‘supported’ and ‘autonomous’ forms of communication (Citation2018, 163), we argue that asylum and migration encounters require a more inclusive use of multilingual provision that takes into account supported (structural, regulated) as well as autonomous (creative, ad hoc) semiotic means (verbal and non-verbal), that are better adjusted to the local needs of service providers and users. Tipton (Citation2018) highlights how participation of foreign language speakers in multilingual encounters is not contingent on interpreting services but may also benefit from involvement by means of other semiotic forms that are creatively employed to realise multiple functions of language such as expressing empathy and building rapport. Embracing the flexible multilingual repertoires of contemporary institutional participants, this special issue incorporates contributions from the fields of applied linguistics, interpreting studies, pragmatics and linguistic ethnography, bringing together their insights towards a better understanding of the language ideological and multidiscursive complexities encountered in institutional and everyday interaction with migrants and refugees.

3. Overview of contributions

The main idea of this volume is to address the availability and versatility of multilingual resources of language support in relation to the specific contextual needs of situated interaction in asylum and migration encounters. Much of the research that has been conducted on language mediation in asylum and migration settings until now focuses on language brokering by immigrant children who learn the community language at school and interpret informally for their parents or other family members (Angelelli Citation2012; García Sánchez Citation2012; Guo Citation2014; Katz Citation2014; Antonini Citation2015; Bauer Citation2017). Research on volunteer and ad hoc language mediation performed by adults has developed only recently in a whole range of hitherto under-researched contexts, including prisons (Baixauli-Olmos Citation2013; Rossato Citation2017), military conflict (Baker Citation2010; Inghilleri Citation2010), disaster relief (Bulut and Kurultay Citation2001; Rogl Citation2017) and religious settings (Hild Citation2017; Hokkanen Citation2017). In their recently published special issue on translation and interpreting ethics in non-professional practice, Monzó-Nebot and Wallace argue that ‘systematic, empirical analyses of the practice of non-professional translators and interpreters continue to be under-represented’ and therefore call for ‘new insights into less examined practices’ (Citation2020, 3).

This collection of papers aims to contribute to this relatively unexplored field of language research focusing on the continuum of widespread, but largely invisible types of multilingual support that have previously fallen outside the active concern of interpreting and translation scholars. The contributions included in this special issue cover a variety of migrant and refugee encounters, with a focus on interaction between speakers of different languages in public service settings with differing contextual needs (healthcare, court, social welfare) and with the aim of identifying strategies that facilitate communication and reduce disadvantages for speakers of non-official languages. These encounters range from migration procedures (cf. Vandenbroucke and Defrancq) to legal and medical counselling (cf. Cox and Maryns; De Wilde and Maryns; Angermeyer and Meyer), and community support initiatives such as language cafés or counselling services (cf. Jansson; Lee).

The theme of flexible multilingual strategies in asylum and migration encounters was introduced at the ‘International Colloquium on Multilingualism and Interpreting in Settings of Globalisation: Asylum and Migration’, which was held in 2015 at Ghent University, Belgium. The colloquium aimed to focus attention on the generally under-investigated and underrated complexities of institutional multilingualism and interpreting in settings of asylum and migration. Papers delivered at the colloquium addressed a broad range of topics: language ideologies and policies of multilingual service provision for migrants and refugees, linguistic inequality and social injustice resulting from insufficient language support, employability of migrants with multilingual skills in the provision of language support for newly arrived immigrants, and the social and ethical positioning of the different actors involved in multilingual service provision. Building on these themes, the six articles in this special issue, each with their own theoretical and empirical focus, reveal the enabling possibilities of a more inclusive approach to multilingual service delivery to improve access to basic services and resources for migrants and refugees.

The collection opens with Vandenbroucke and Defrancq’s comparative empirical analysis of the performance of professional interpreters and informal ad hoc interpreters mediating in marriage fraud investigative interviews in Belgium. Belgian law does not provide guidelines for the type of interpreter required to mediate in these interviews and, as a consequence, a high degree of variation can be found in the type of interpreter selected and in the handling of ethical issues. Five interpreter-mediated interviews with a marriage applicant were selected for in-depth analyses. The findings show that the professional interpreters’ performance actually resembles the practices of ad hoc or informal interpreting as the authors found non-normative patterns of turn-taking and footing, as well as taking stances that were not impartial. Interpreters were also found to exert influence on the selection of information that was conveyed and entextualised in the report. The authors conclude that these practices do not ensure equal treatment and due process as should be expected in this type of high-stakes legal-administrative investigation.

Also drawing on authentic interactions, De Wilde and Maryns examine the impact of communicative choices on the quality of service provision in the context of HIV/STD counselling. Reporting on a case study involving a regional office of the NGO ‘Doctors of the World’, the contribution demonstrates that when multilingual resources and strategies are not sufficiently tailored to the specific needs of the interaction and the actors involved, this can impact on the effectiveness of the consultation. Applying the sociolinguistic concept of contextual commonality (Gumperz Citation1982; Goodwin Citation2007; Blommaert Citation2015) to considerations of how increased meta-communicative reflection could clear up potential misalignments, the findings suggest the need for a more rigorous consideration of the contextual complexities and challenges of providing adequate multilingual assistance in service encounters with specifically vulnerable migrants and refugees.

Like Vandenbroucke and Defrancq, Lee also investigates interpreting in the context of marriage migration, specifically interpreting for migrant women in South Korea who are married to Korean men. Drawing on interviews with interpreters at state-sponsored Multicultural Family Support Centres, as well as with Korean social workers who supervise them, she examines how they perceive the role of interpreters in counselling sessions. As the interpreters are themselves migrant women, they share a language and migration experience with users of the support services, making it harder for them to maintain role boundaries. This is particularly the case when they engage in one-on-one interactions that may involve cultural mediation or marriage counselling for women in difficult relationships. Their task as interpreters is also undermined by institutional goals concerning marital counselling, as both the interpreters and their monolingual Korean supervisors may prefer for confrontational or emotional speech to be downplayed rather than interpreted accurately and completely. Lee thus argues that the institutional failure to define clearly the role of marriage migrants acting as interpreters disempowers the migrant women who rely on them.

Cox and Maryns also take up the issue of how to identify the most appropriate language support strategies to ensure the best possible service provision for minority speakers. They report on the negotiation, use and functionality of readily available multilingual solutions – such as the use of a lingua franca, medical translation software and language mediation through companions – in consultations with immigrant patients in a Belgian Emergency Department. Adopting a case study approach, evidence is provided of how doctors, patients and their multilingual companions mobilise complementary repertoires of verbal and nonverbal resources and strategies to achieve challenging communicative tasks. The authors demonstrate that due to the lack of linguistic and interpreting subtleties, potential mismatches of meaning remain undetected and this generates an illusion of understanding or false fluency. Their findings lead them to argue for an improved management of the allocation of multilingual support, including integration of an assessment of the patient’s language needs into the triage process.

Jansson looks at multilingual practices and normativity in intercultural encounters in a language café set up as part of an integration project promoted by the Equmenia Church in Sweden. The author combines an ethnographic approach with conversation analysis and membership categorisation analysis, i.e. methods that are used in interaction studies. A rich micro-level analysis is carried out on two extracts of video-recordings of interactions between volunteers and migrants at the language café. In both interactions there is a multilingual non-professional facilitator, who is assigned the role of assisting as an interpreter in the integration project. Both extracts contain examples of normative work vis-à-vis sensitive, culture-related topics. The findings clearly show that the interpreting skills of the facilitator are not of central importance to the interaction and that she does much more: she addresses moral issues through (i) explaining and clarifying; (ii) adding information; (iii) expanding on the agenda of the primary party; and (iv) expressing stances and taking sides. These findings highlight the mediating role lay multilingual speakers play in intercultural communication and in migrants’ early processes of socialisation.

While the other papers in this special issue each focus on a particular setting of multilingual communication, Angermeyer and Meyer compare interpreting in different settings, using a quantitative approach. Drawing on the ComInDat corpus (Angermeyer, Meyer, and Schmidt Citation2012), which contains data from court interpreting, medical interpreting, and simulated medical interpreting for trainees, they examine the occurrence of non-renditions, that is utterances by interpreters that do not involve the translation of previous talk (Wadensjö Citation1998). The analysis finds systematic differences between professional court interpreters and non-professional and ad hoc medical interpreters, but also commonalities between settings, as all interpreters stick more closely to the task of interpreting when they translate the speech of institutional representatives into the language of lay participants than they do in the other direction. Examining differences between individual interpreters, Angermeyer and Meyer find that non-renditions often co-occur with codeswitching by lay participants, that is with their use of the institutional language to bypass the interpreter. This shows how flexible language use may result in a redefinition of the interpreter’s role (prompting them to produce non-renditions), while it may at the same time be a consequence of interpreters’ tendencies to prioritise the voices of institutional agents when they translate.

The papers in this issue show that practices of interpreting and multilingual communication are highly context dependent. At the same time, they reveal considerable parallels that affect both professional and non-professional interpreters. In all settings, flexible language strategies are found, and even professional interpreters may be prompted to participate in ways that their professional rules do not endorse (see especially papers by Angermeyer and Meyer, Vandenbroucke and Defrancq). At the same time, even non-professional interpreters are influenced by institutional communicative norms that may lead them to serve primarily the goals of the institution rather than the lay participant. Several papers also show how interpreting is intertwined with intercultural mediation (see e.g. papers by Jansson, Lee). The different contributions to this issue confirm that, when considering the whole array of multilingual strategies on a continuum, there is a large gap between a complete absence of linguistic support at one end of the spectrum and mediation by a certified interpreter at the opposite end. This transition zone has long remained unexplored in multilingualism and interpreting research, either because these practices tend to go unnoticed, for instance in the case of ad hoc or available solutions (see especially Cox and Maryns, De Wilde and Maryns) or because they are not considered forms of multilingual practice that deserve scientific analysis (Antonini et al. Citation2017). However, the rich diversity of these multilingual strategies needs to be further explored, especially in the context of migration and asylum where any type of communication breakdown may have serious consequences for the individuals involved. We therefore wholeheartedly endorse more in-depth research into multilingual service delivery, so that we can gain more thorough insights into these complex communication processes, the results of which can be used to design evidence-based institutionalised decision models that assist service providers in identifying the most appropriate language support strategies in the given service encounter.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The (rather derogatory) term ‘Tarzan language’ is used by different Flemish Integration Agencies (AgII, Atlas) to refer to a form of simplified, foreigner-talk register of Dutch (e.g. ‘Jij morgen afspraak’, which could be translated as ‘You tomorrow appointment’). The agencies strongly discourage this form of perceived linguistic accommodation in the communication with foreign language speaking clients.

References

- Angelelli, C. 2012. “Language Policy and Management in Service Domains: Brokering Communication for Linguistic Minorities in the Community.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Language Policy, edited by B. Spolsky, 243–261. Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress.

- Angermeyer, P. S. 2015. Speak English or What? Code-switching and Interpreter Use in New York City Courts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Angermeyer, P. S., B. Meyer, and T. Schmidt. 2012. “Sharing Community Interpreting Corpora – A Pilot Study.” In Multilingual Corpora and Multilingual Corpus Analysis (Hamburg Studies in Multilingualism), edited by T. Schmidt and K. Wörner, 275–294. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Antonini, R. 2015. “Child Language Brokering.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies, edited by F. Pöchhacker, 48–49. London: Routledge.

- Antonini, R., L. Cirillo, L. Rossato, and I. Torresi. 2017. Non-professional Interpreting and Translation: State of the Art and Future of an Emerging Field of Research. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Baixauli-Olmos, L. 2013. “A Description of Interpreting in Prisons: Mapping the Setting through an Ethical Lens.” In Interpreting in a Changing Landscape. Selected Papers from Critical Link 6, edited by C. Schäffner, K. Kredens, and Y. Fowler, 45–60. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.109.06bai.

- Baker, M. 2010. “Interpreters and Translators in the War Zone. Narrated and Narrators.” The Translator 16 (2): 197–222. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2010.10799469.

- Bancroft, M. A. 2015. “Community Interpreting.” In The Routledge Handbook of Interpreting, edited by H. M. Mikkelson and R. Jourdenais, 217–235. Oxford: Routledge.

- Bauer, E. 2017. “Language Brokering: Mediated Manipulations, and the Agency of the Interpreter/translator.” In Non-professional Interpreting and Translation: State of the Art and Future of an Emerging Field of Research, edited by R. Antonini, L. Cirillo, L. Rossato, and I. Torresi, 359–380. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Bergunde, A., and S. Pöllabauer. 2019. “Curricular Design and Implementation of a Training Course for Interpreters in an Asylum Context.” Translation & Interpreting 11 (1): 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.12807/ti.111201.2019.a01.

- Blommaert, J. 2006. “How Legitimate Is My Voice? A Rejoinder.” Target 18 (1): 163–176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/target.18.1.09blo.

- Blommaert, J. 2015. “Chronotopes, Scales, and Complexity in the Study of Language in Society.” Annual Review of Anthropology 44: 105–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102214-014035.

- Bulut, A., and T. Kurultay. 2001. “Interpreters-in-aid at Disasters: Community Interpreting in the Process of Disaster Management.” The Translator 7 (2): 249–263. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2001.10799104.

- Cronin, M. 2006. Translation and Identity. London: Routledge.

- García Sánchez, I. M. 2012. “Language Socialization and Exclusion.” In The Handbook of Language Socialization, edited by A. Duranti, E. Ochs, and B. Schieffelin, 391–420. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Goodwin, C. 2007. “Participation, Stance and Affect in the Organization of Activities.” Discourse & Society 18 (1): 53–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926507069457.

- Gumperz, J. 1982. Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Guo, Z. 2014. Young Children as Intercultural Mediators: Mandarin-speaking Families in Britain. London: Multilingual Matters.

- Hild, A. 2017. “The Role and Self-regulation of Non-professional Interpreters in Religious Settings: The VIRS Project.” In Non-professional Interpreting and Translation: State of the Art and Future of an Emerging Field of Research, edited by R. Antonini, L. Cirillo, L. Rossato, and I. Torresi, 177–194. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Hokkanen, S. 2017. “Simultaneous Interpreting and Religious Experience: Volunteer Interpreting in a Finnish Pentecostal Church.” In Non-professional Interpreting and Translation: State of the Art and Future of an Emerging Field of Research, edited by R. Antonini, L. Cirillo, L. Rossato, and I. Torresi, 195–212. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Inghilleri, M. 2010. “‘You Don’t Make War without Knowing Why’. The Decision to Interpret in Iraq.” The Translator 16 (2): 175–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2010.10799468.

- Katz, V. S. 2014. Kids in the Middle: How Children of Immigrants Negotiate Community Interactions for Their Families. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Monzó-Nebot, E., and M. Wallace. 2020. “New Societies, New Values, New Demands: Mapping Non-professional Interpreting and Translation, Remapping Translation and Interpreting Ethics.” In Ethics of Non-Professional Translation and Interpreting, edited by E. Monzó-Nebot and M. Wallace. Special Issue of Translation and Interpreting Studies 15 (1), 1–14. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Polezzi, L. 2012. “Translation and Migration.” Translation Studies 5 (3): 345–356. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2012.701943.

- Rillof, P., E. Van Praet, and J. De Wilde. 2014. “The Communication Matrix: Beating Babel: Coping with Multilingual Service Encounters.” In (Re)visiting Ethics and Ideology in Situations of Conflict, edited by C. Valero-Garcés, B. Vitalaru, and E. Mojica López, 263–269. Universidad de Alcala. http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-5718124

- Rogl, R. 2017. “Language-related Disaster Relief in Haiti: Volunteer Translator Networks and Language Technologies in Disaster Aid.” In Non-professional Interpreting and Translation: State of the Art and Future of an Emerging Field of Research, edited by R. Antonini, L. Cirillo, L. Rossato, and I. Torresi, 231–258. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Rossato, L. 2017. “From Confinement to Community Service: Migrant Inmates Mediating between Languages and Cultures.” In Non-professional Interpreting and Translation: State of the Art and Future of an Emerging Field of Research, edited by R. Antonini, L. Cirillo, L. Rossato, and I. Torresi, 157–176. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Rudvin, M., and A. Carfagnini. 2020. “Interpreting Distress Narratives in Italian Reception Centres: The Need for Caution When Negotiating Empathy.” Cultus 13: 123–144.

- Tipton, R. 2018. “Translating/ed Selves and Voices Language Support Provisions for Victims of Domestic Violence in a British Third Sector Organization.” Translation and Interpreting Studies 13 (2): 163–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.00010.tip.

- Wadensjö, C. 1998. Interpreting as Interaction. London: Longman.

- Yildiz, Y. 2012. “Response.” Translation Studies 6 (1): 103–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2012.721581.