ABSTRACT

In this paper, we as the teachers and researchers of a course titled Global education development informed by theories of decoloniality, report on our analysis of our self-critical and constructive dialogue on the course design, its underlying assumptions, expectations, implementation, success and needs for improvement. We centered decoloniality from the beginning of the course, problematised binary-thinking and encouraged our students to look at issues within the field of development and education in pluriversal ways. Our gestures toward decolonial pedagogy in the course were complicated by our own entanglements with coloniality as well as structural factors such as the context of Finland, where the colonial past is seldom addressed. Despite these contradictions and challenges, we aspire to continue thinking through decoloniality to decenter the dominant liberal frameworks within global education development.

Introduction

“Schooling for all has long been an international goal. The idea that all people, wherever they live and however poor they might be, should have the opportunity to develop their capacities to improve their own lives and create better societies has been a key notion articulated by social reformers in many different kinds of society for centuries. Yet history has proved that it is extraordinarily difficult to realize this widely shared aspiration.” (McCowan and Unterhalter Citation2015, 1–2)

Designing and implementing a university course on such a difficult aspiration as global education development seemed a challenging task. As course designers and teachers of a course on ‘Global education developmentFootnote1’, we had to decide on what to cover, how to arrange teaching and learning, what to select as core study material, and moreover, what conceptual and theoretical approaches to select. First, the book Education and International DevelopmentFootnote2 edited by Tristan McCowan and Elaine Unterhalter (Citation2015) guided the course planning. We shared an interest in understanding education development in line with Andreotti’s (Citation2011) decolonial notion of global mindedness that emphasises seeing ‘learning to read the world through other eyes’ which requires the acknowledgement of multiple perspectives on reality. In the course design, we planned to engage university students both from Finland and abroad in exploring global education development with a decolonial lens. During the course implementation we recognised the need for and importance of reflecting on our underlying assumptions (defining and discussing education development in whose eyes), teaching and learning processes (decoloniality in interaction and practices), the learning outcomes (students’ experiences and achievements).

The course titled ‘Global education development’ is one of the virtual study courses provided in English by the Finnish University Partnership in International Development (UniPID)Footnote3, a network of universities working with issues related to sustainability and global challenges. The network’s virtual courses focus on development studies and are available for degree and exchange students registered in universities in Finland, and from 2021 also to students from the network universities’ partner institutions (UniPID Citation2021). Students may take one course or even complete an amount equivalent to a minor (25 ECTSFootnote4) credits that can be integrated to their degree. The flexible online learning studies enable students from diverse disciplines, study programmes, universities, and contexts to join.

The course focused on education development across the world rather than in a specific country to study the global connectedness in education, the influence of global governance on educational development and the interaction between local actions and global policies, and to position ourselves, as students and teachers, in the field of educational development. The use of ‘global’ rather than ‘international’ was an informed choice, drawing on Unterhalter’s (Citation2015) review of perspectives to education development and emphasis on understanding of education ‘as a set of ethical ideas about rights, capabilities and obligations which enjoin particular ways of thinking about what we owe each other regardless of our nationality and our particular beliefs’ (Unterhalter Citation2015, 28).

The work of decolonial scholars (Andreotti Citation2011; de Sousa Santos Citation2018; Mignolo Citation2011a, Citation2011c) inspired the course planning. We wanted students to critically reflect on who sets agendas and defines priorities, what research informs ideas about development, whose voices and knowledges are included in development discourses, and the ways changes in global education development are assessed. Thus, the coursework aimed to critically reflect on educational power structures globally and locally, giving attention to how education is implicated in the colonial matrix of power (Mignolo Citation2011a; Mignolo and Walsh Citation2018; Quijano Citation2000).

In addition to the global context, the decolonial lens in education development seemed important in the context of this Finnish university course because decoloniality has been largely absent in educational research and education development cooperation discourses. In light of Sámi studies, Finland represents a context where the colonial past may be discussed but is seldom critically addressed (Lehtola Citation2015). In relation to Western colonisation, Finland has an ambivalent position, having been both occupied by foreign kingdoms and built on racialised conception of nationhood.Footnote5 Furthermore, a colonial worldview is maintained through narratives of Nordic benevolent exceptionalism and equality (Pashby and Sund Citation2020; Vuorela Citation2009) which is evident, for instance, in the recent education export initiatives that have benefited from the international positive image created around Finnish education following the consecutive successful outcomes in OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) from the early 2000s (Schatz Citation2016). Education export may represent a form of neocolonialism, legitimised by the neoliberal marketisation of excellence and following the complex drives of international development aid work (Juusola Citation2020; Schatz, Popovic, and Dervin Citation2017). Such observations alerted us as teachers responsible for the course Global education development to address education development with a decolonial lens.

Throughout the course, as course designers and teachers, we critically reflected on the theoretical approaches we took as well as the worldview our course represented and may have reinforced. Following McCowan (Citation2015), teachers need to be aware of the theories they use for understanding the underpinnings of policies and practices in education development to allow them to teach and encourage students to engage, critique and recast (dominant) theories. This task challenges us to review our own thinking and approaches. After the first round of the virtual course was completed in April 2020, we teachers and researchers reflected on the design and pedagogy in a series of reflective group discussions. In this paper, we analyse our gestures towards decolonial theory in the course on Global education development. The research questions guiding our paper are:

How has our understanding of decoloniality informed the planning and execution of the first offering of the virtual course on Global education development?

What have we learned as university teachers and researchers about the possibilities and challenges of introducing decoloniality in Global education development?

There are multiple views of the gesture of decoloniality, and we do not intend to make available a prescriptive model or an example of good practices. Instead, our goal is to offer situated insights about our experiences and learning using decoloniality in curricula and teaching of global education development.

Theoretical framings

Decoloniality is an endless process and practice of challenging and transforming the relations of colonial domination (Legg Citation2017). This means relentlessly aiming to delink from the cloak of coloniality disguised under the rhetoric of modernity (progress, growth) which has and continues to be seen as the natural order of things due to Europe claiming a dominant position geo-politically and epistemically in order to open up decolonial options (Mignolo Citation2011a, Citation2011b). The epistemic hegemony of Western knowledge disregards and invisibilises other ways of being, knowing, and living and encourages material domination of those who are outside the Eurocentric norm (Stein Citation2019). Decoloniality is not meant to supplant the dogma of the Western episteme within higher education with another, singular and totalising decolonial episteme. It rather de-centers the West and affirm the re-emergences, re-existences and liberation of people dominated by the global westernising project. In this way, it secures and re-links with memories, modes of existence and legacies that people have reason to value but have been destituted by modernity (Mignolo 2016).

Decolonising the ideologies of development also requires decolonising development education and its pedagogies (Rutazibwa Citation2018; Sultana Citation2019). Decolonial pedagogy approaches teaching by thinking from the outside. We approach our teaching sitting at the border, trying to learn from indigenous and non-western traditions and cosmologies. Decolonial pedagogy is also a commitment to working without fixed hierarchies and beyond the student/teacher binary. In this way, decolonial pedagogy is pragmatic, involving decentring dominant practices and voices (Atehortúa Citation2020; De Lissovoy Citation2010; Silva Citation2018). In addition, decolonial pedagogy is dialogic. It is a process of conscientisation (Freire Citation1970) as the students become able to recognise their own entanglements in the colonial matrix of power (Walsh Citation2015). Decolonial pedagogy is therefore also a reflexive learning process in which students reflect not only on colonial histories and geographies, but also their own personal biographies.

Dialogic inquiry framed both our pedagogical practice and our methods in writing this paper. We see dialogic inquiry and reflective practice as essential in decolonial gestures – it is a way of developing dialogical forms for the construction of knowledge (Cusicanqui Citation2012). Reflecting on our own teaching we also engage in dialogue which helps us to decolonise our own ways of thinking and open up possibilities for (re)learning through our practice in new ways.

Methods

The data for this paper was generated in a series of three recorded teacher-researcher dialogues between us, the teachers and researchers of the Global education development course. The core team of the course Global education development course consisted of Elina (Professor of Education), Boby (PhD researcher with years of teaching experience) and Sharanya (PhD researcher with some teaching experience). Additionally, the authors include Crystal (postdoctoral researcher with teaching experience) who was one of the visiting scholars of the course and Irène who worked with the team as an intern to collect and analyse data on the course implementation and examine how social presence was experienced, negotiated and perceived by students. The authors of the paper are all living and working between worlds. As scholars with the experience of working in diaspora, our sense of our own positionalities cannot be fixed nor unitary but become salient in relation to changing contexts and relationships. In our reflections and discussion, we open up the complexity of our positionalities. We followed a dialogic inquiry and collaborative reflective discussions in these dialogues to engage and learn from each other. All the three teacher-researcher dialogues were 60–90 min long. They were recorded on Zoom and were transcribed by the authors. Crystal, Sharanya and Irène analysed the contents of the transcripts individually and collaboratively and devised the themes. These themes were refined further in discussion with Elina. The themes that were identified in our analysis of the first two discussions were used to guide the third discussion.

The decolonial methodological orientation of this paper is based on a humanising aspiration; it is a collaborative sense-making experience that is creative and edifying (Boveda and Bhattacharya Citation2019). We attempt to use a transformative methodology which will have implications for our own transformation and for our decolonial praxis in the course. Since we are writing this paper as a collaborative reflection, we have opted to use ‘we’ in presenting the findings. We have also chosen to write parts of our dialogues directly, rather than using pull quotes from the transcripts to demonstrate the authenticity of our interpretation of the data. When relevant, the name of the author whose perspective is elaborated is indicated.

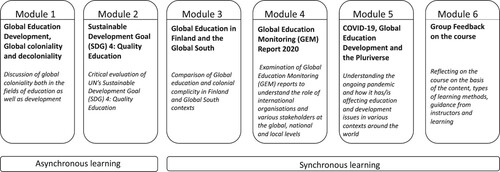

This paper focuses on our reflections on the course Global education development offered in the 2020 spring semester by the University of Oulu in collaboration with the UniPID Network. The 5 ECTS masters level course lasted 12 weeks and included 5 synchronous discussions as well as several asynchronous discussions in Moodle forums. The course was divided into six modules (see ). After each module, students were also asked to write in a learning diary. Sixty-seven students registered for the course and thirty-five completed. Out of the thirty-five students, sixteen were Finnish students and nineteen were international master’s students or exchange students in Finland. Out of the nineteen international students, eleven came from countries categorised under the Global North and nine were from countries placed under the Global South. In the course, students explored the themes of interconnectedness among humans and the environment within the fields of global education and international development, raising critical questions around belonging, access and quality living for all.

Our reflections

The primary goal of this reflective paper is to offer insights on how our understanding of decoloniality informed the planning and execution of the virtual course on Global education development. In addition, we also want to highlight some of the possibilities and challenges that we as teachers experienced while working with decolonial perspectives. In the reflections, we analyse the choices made in the course design, our perceptions of students’ engagement with the course and our learnings based on the teacher-researcher dialogues. The results of our dialogic inquiry are presented in three parts, following a chronological order, starting with the beginning of the course, moving to the process throughout the course, to finally focusing on the end of the course.

Beginning with decoloniality

We start by considering how we interpreted the ways in which the students initially engaged with decolonial theory and how this related to our own experiences of the course and decoloniality. In the course design, we foregrounded decoloniality to make our students think deeply about their socially situated realities in relation to the course content, destabilise the authority of the Eurocentric perspectives and begin thinking and engaging with pluriversality. For this reason, we begin a consideration of global education development by asking, where do we start the story? Beginning with Finland’s colonial entanglements in international development is an effort to remedy what Rutazibwa (Citation2018) calls ‘colonial amnesia’ and, in Finland’s case, what Vuorela (Citation2009) calls ‘colonial complicity’.

In the first module of the course, students read Zavala’s (Citation2016) article Decolonial methodologies in educationFootnote6, and watched a video featuring scholar Vanessa Andreotti titled Shouldering our colonial backpackFootnote7 (2016) along with Nygaard and Wegimont’s (Citation2018) paper on Global Education in Europe … Development.Footnote8 Highlighting decolonial and postcolonial scholarship from the start was inspired by the way Morreira (Citation2017) started her course on social sciences with Steven Biko’s work, a South African anti-apartheid activist, as opposed to the works of Euro-American scholars highly regarded in the field. By juxtaposing decolonial reading of education with the dominant perspectives on Global education development, we hoped students would begin questioning why certain models of education and development are privileged over the others. After engaging with the content individually, the students were asked to reflect on the question, ‘What are your thoughts on thinking about Global education development through the lens of decoloniality?’ in a Moodle forum and in their individual reflective learning diaries.

In students’ responses, we felt like students experienced both the possibilities and challenges of embracing decolonial theory. Firstly, we were surprised to read that very few of them had prior opportunities to engage with decolonial/anti-colonial literature, yet they thought it was relevant to global education development. They deliberated on the need for decolonial methods as they felt that some prevalent ideas and concepts within education development such as indicators under Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 4 (ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all) do not really take into consideration the local contexts. One student raised in the Latin American context reflected on how the contents of this module made them reflect on the lack of spirituality and connection to nature in their education. As a teacher, this reflection evoked an emotional response in Sharanya as the student described how our relationality with the environment profoundly impacts how we perceive and think about nature and creates possibilities for radical change (or not). We were quite happy to read students’ critical stance on some of the issues within Global education development and hoped they would go deeper than simply reject the SDGs by the end of the course.

Secondly, in their responses to the course content, students wondered if border thinking and decolonial methods could truly emerge from the margins within Global North and the West, querying whether that would be considered misappropriation. As course teachers, we responded to these questions by asking if the onus of expanding decolonial thought should be placed solely on margins of the Global South. We wanted them to consider the implications of working with theories coming from the margins and the responsibilities that come with adopting and adapting something which did not originate from a context or social reality that they are familiar with. In our teacher-researcher dialogue, Boby described this process as ‘productive tension’ i.e. ways of engaging with the course material which makes us uncomfortable yet inspires us to think, reflect further and make room for cognitive dissonance. We wanted the students in our course to develop a philosophical inquiry so that they are able to sit with their discomfort and express their learning and reflexive processes through the learning diaries.

Finally, there was also a general sentiment among the students about how challenging it is to actually de-link from one’s own Eurocentric ways of thinking about education and development. One student described how the relational nature of decolonial methodologies makes it difficult to form connections with global education development without falling into the ‘trap’ of epistemological and ontological colonialism. In our teacher-researcher dialogues, we discussed at length about this ‘trap’ as being the most challenging part of engaging with decoloniality in education. We wonder how to inhabit and work within colonial structures in education while desiring the decolonial? How do we collectively desire non-dominant approaches in global education development? How do we pull the rug of colonialism from under our feet, while standing on it knowing that part of us still desires the comfort it provides us? How do we authentically engage with decoloniality while not becoming desolately hopeless? This metaphor of the ‘trap’ is a reminder for us to be reflexive of our seemingly decolonial aspirations. Some students also described the struggles of working with decolonial methodologies, especially dealing with issues of race and ‘white guilt’. This is an important topic to consider in the Finnish context because there are silences around issues of race due to a lack of acknowledgement of Finland’s racist past (Rastas Citation2004).

We as teachers and researchers shared the same sentiment about the challenges of completely embracing decoloniality within the context of our institution. Indeed, we are all implicated in structures larger than us and resisting structural forces requires courage and patience. Engaging with decolonial pedagogy is an arduous task because if the institutional structures do not support you there are many tensions (some more palpable than others) that arise. In the course design, we aspired to move away from certain normative practices inspired by decolonial thought. For instance, we thought of reflective learning diaries as an opportunity for the students to engage reflexively with the course content and not write a term-end paper. However, these diaries were also graded per the university requirements and only those students who completed all the learning tasks were able to receive the five ECTS credits for the course. Elina had proposed that the students who completed a portion of the coursework could receive a portion of the ECTS credits, however we were not able to negotiate that with the stakeholders. This required assessment felt like a departure from the idea of engaging in epistemic disobedience in more meaningful and creative ways.

Another example of this tension is the way we had to set criteria for critical thinking to assess students’ assignments. We evaluated the extent to which students used multiple sources (usually peer-reviewed sources) to justify their claims or arguments in the paper. One of the students pointed out in the feedback that they found it ironic that they had to reflect personally in the diary entries but at the same time follow a rubric (e.g. connections to material assigned, critical argumentation, APA style citationFootnote9). As teachers and researchers, we later reflected on how this evaluation was based on the dominant way of conceptualising critical thinking in higher education, that is, defining critical thinking as a rhetorical strategy of citing from established literature often produced in and for the Global North. We realised that we could have looked at other non-dominant ways in which criticality and critical thinking are conceptualised as culturally situated and socially constructed practices (Vaidya Citation2016; Vandermensbrugghe Citation2004). Finally, our perceptions of students’ engagement with the course made us wonder – by asking them to question their positionality in relation to the course content, have we managed to create opportunities to engage with the concept of coloniality/decoloniality not only intellectually but also emotionally, ethically and spiritually?

Problematising the binaries within Global education development

After students initially engaged with decolonial theory, several activities were organised in Module 2 to help them problematise binary thinking in, for instance, defining quality education. Our course had a strong emphasis on SDG 4 and the global policy frameworks such as the Global Education Monitoring Reports.Footnote10 Yet, we wanted to emphasise the diverse ways in which we can interpret and understand, agree, and disagree on what constitutes ‘quality education’. While most of our students agreed that local narratives and initiatives should be privileged, some of them asked if the term ‘global’ in global education development itself is colonial as it implies some form of uniformity or consensus. We were pleased to read that students were beginning to question the content and not uncritically accept what we assign as part of their course material.

This was further examined in Module 3 on Global education development in Finland and other contexts, designed with the intention of giving the students an opportunity to start engaging with the politics of the local vs the global. Students read Vuorela’s (Citation2009)Footnote11 post-colonial reading of Finland’s colonial complicity. They were then asked to link it to another area in global education in Finland (e.g. developmental aid, education export, Finnish curriculum, academic research) to begin thinking about the ways in which coloniality could operate in these areas. Through these readings, we were hoping to make the abstract concepts of colonial/decolonial more apparent and visible in the Finnish context. The learning diary prompt for this Module was: ‘Did you find any connections between the article ‘Colonial Complicity: The ‘Post- colonial’ in a Nordic context and the second reading you chose?’. Elina considers this deliberation over these binaries to be important particularly in Finland as there is an uncritical acceptance of the Finnish education system. Finnish teachers are considered to be the ‘best’ in the world without taking into account the (political, security, cultural, social) variables that have been in influential in the ways Finnish education system is perceived as it is today. As course teachers, we were curious to know how students from Finland interpret colonial division of labour within global education development as compared to international students born and raised in non-western contexts in their learning diary reflections.

Our general perceptions of the students’ reflections were that many of the international students from non-western contexts were able to resonate with Vuorela’s (Citation2009) article at a personal level in comparison to the Finnish students whose reflective diary responses were quite neutral. After the course, when we discussed in the teacher-researcher dialogues, we talked about the ways in which we could have opened up about our own positionalities and ways in which we could make the students, especially Finnish students think about how their neutrality might be linked to colonial complicity. One student touched on this complicity by evoking the challenges of bringing about change without participating in the circles of power that they often critique and question. In similar vein, in our teacher-researcher dialogues, we discussed that engaging with decolonial theories at the university feels like a kind of cognitive dissonance; there is an instability in knowing the limitations of the university as a colonial space and still engaging in decolonial practice, building a career within academia on the premise of deconstructing the institution. This begs the question – can the university and courses offered through the university truly be a space for engaging in decolonial work?

For the students to investigate the issue of binaries within Global education development further during the course, we invited colleagues who had experiences working in the field of international education and development from Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Sweden and the United States for a panel discussion. The topic for the discussion centered on what global education development meant in their respective contexts and what could a decolonial global education development look like based on their experiences in the field. We hoped that listening to diverse perspectives from around the world would help students think outside of the contexts they are most familiar with, especially our Finnish students who had mentioned that this course was the first time they were encountering perspectives on anticolonial literature.

All of the speakers emphasised the importance of understanding the diversity within binaries such as the ‘Global North’ and ‘Global South’ so as to create a circulation of ideas and build solidarities between marginalised peoples. One of the speakers talked about Nai Talim (New education) – a Gandhian philosophy of education for the head, heart and hand that questions boundaries between education and work, knowledge and skills. They gave an example of how food and food systems are taught in schools in India by only focusing on the ‘facts’ about food (e.g. nutritional value, constituents) without taking into consideration other contributing issues such as availability, affordability, available technology, traditions of preservation, and the social realities of children. These examples highlight how education systems do not offer a platform to engage with different topics within education with nuance. The speakers concluded that to move beyond binaries we need to create small ruptures of change in the spaces we occupy and traverse. We speculated how we could have created more possibilities for the students to participate in creating ruptures or participating in what Mignolo (Citation2011b) calls ‘epistemic disobedience’.

Reflecting on the binaries was quite challenging even for us as teachers and researchers. If we came up with new terms to talk about the binaries such as the ‘Global North’ and ‘Global South’, we fear that it would lead to a sanitisation around conversations about inequalities within Global education development. While certain terms and concepts are certainly problematic, by completely doing away with them we may avoid the reconciliation process which is of paramount importance for groups that have been wronged because of coloniality.

Gesturing towards the pluriverse: challenges and possibilities

In the fifth Module of the course, we asked students to work together in groups and read essays from Pluriverse – a post-development dictionaryFootnote12 by Kothari et al. (Citation2019). We hoped that this book would give the students an opportunity to pause and think collectively about alternatives to mainstream models of global education development amidst the Covid-19 pandemic. The students had to select an approach outlined in Pluriverse and think about ways to address a current issue in education exacerbated by the pandemic and present it in any format they like to their course mates. Students chose to discuss two key issues in education during Covid-19 – school meals and inequitable access to technology. Food sovereignty, low-tech educational tools and civilisational transitions were the most common approaches from Pluriverse cited by the students to address these issues. All these alternative approaches call for a systemic change. While the students in our course were hopeful, they were not optimistic about the world system changing from ‘capitalistic-heteropatriarchal’ to a place where multiplicity is allowed and celebrated.

We wanted to encourage pluriversality in thought through this course but sometimes we as teachers felt like we were pushing for one way of looking at issues. For example, during one of the synchronous discussions, Boby recalled being surprised by his own reaction after one student, a priest of the African Orthodox church, raised the issue of religion in the context of global education. Boby’s initial reaction was to dismiss the topic of religion outright. He described his way of thinking that we should ‘do away with religion’ as ‘a standard kind of thinking.’ In our teacher-researcher dialogues, we recognised that our omission of the role of religious institutions in Global education development, despite its historical and contemporary importance, indicates our collective implicit affirmation of modern secularism. Yet a commitment to pluriversal options holds space for discussing religion and spirituality as viable onto-epistemic orientations to the world. On reflection, Boby challenged himself to think about religion in terms of pluriversality and to problematise decolonial translations within the context of religion.

This idea of pluriversality is further convoluted because of a lack of consensus among us as course organisers. For Boby, giving equal importance to various perspectives in global education and international development meant being open to a high level of uncertainty and unknown ways of engaging with these topics. Sharanya, on the other hand, wonders how we can talk about underrepresentation of people from the Global South in Finnish higher education when indigenous Sámi and Roma scholars’ voices are absent in the field. Finally, for Elina incorporating pluriversality meant highlighting scholarship from the Global South and placing it at the core of the course which is rarely seen in Finnish higher education courses. This conception of pluriversality was translated in the course by giving the stage to scholars from the Global South in order to increase representation and incorporate diverse perspectives. However, this bore the risk of scholars from the Global South, such as Sharanya and Boby, being pressured to perform for the Finnish students as token experts. We shared a concern that Sharanya’s and Boby’s experiences would be taken by Finnish students as authoritative examples of the experiences of all South Asian or African people.

We also reflected on the power dynamics between teachers and students, specifically in relation to the expectation of students’ vulnerability and openness to unknown ways of engaging in learning. We encouraged the students to share personal reflections on their own lives, exploring the raw and tender aspects of themselves. We evaluated students based on the extent to which they showed themselves as vulnerable or vulnerable enough to fulfill the criteria of our grading rubric. Vulnerability was therefore not reciprocal, but hierarchically observed. Yet, as course teachers we realised that, even though we stated our positionalities, we did not open up to the students about our lived experiences as individuals struggling with the issues, they raised in the learning diaries such as class, race and gender. The format of the virtual course made it difficult for us to share our vulnerabilities with the students. Elina shared that her openness with the students was hindered in part by the frequency of online synchronous meetings. Thus, we ask ourselves how as course teachers we can show up authentically with our entanglements with coloniality and engage in non-hierarchical dialogue with our students?

We also faced the complexity of addressing students’ multiple resistances towards decoloniality. We felt our students lacked an awareness of their own racialisation as being white in Finland, as part of race blindness in the Nordics (Rastas Citation2019), demonstrated by their neutral responses to Vuorela’s (Citation2009) article. In retrospect, we realised that we could have included more conversations about race and colonial complicity in Finland. Currently, Finland has higher rates of incidents and experiences of racial discrimination, harassment speech and gestures than 12 other European countries (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights Citation2019). We wonder, how do we have nuanced conversations about race in Finland with our students by not just looking at it as an abstract historical concept but engaging with it at a deeper level – as a tender, lived experience?

In one of the teacher-researcher dialogues we discussed our defensiveness when faced with our students’ resistances. We see the students’ resistance as a natural part of all learning processes. Fear, resistance and rejection are common responses to uncertainty and the unknown. This resistance also manifested in students’ desire for stability and consensus. They expressed their sense that we cannot move away from the universal and still have a peaceful world. Similarly, the students preferred to rely on their traditional academic habits, even when provided with spaces to explore non-standard options. In the group task based on the alternative approaches to education, students were encouraged to display their work in other formats (e.g. infographics, podcast, vlog). But most students chose common formats used in academia such as PowerPoint presentations and standard essays. While we acknowledge that some other formats might be becoming increasingly popular in higher education, they are not given the same status as traditional academic essays backed by peer-reviewed sources. To conclude, we want to encourage our students to challenge the status-quo and think about alternatives but at the same time be mindful of their actions and not just accept a new way of doing something without thinking through it thoroughly.

Our learnings

By approaching Global education development with a decolonial lens, we hoped to introduce various possibilities for disentangling from hegemonic Western ideologies and with methods and materials that decenter Eurocentric knowledges and ways of being (Sultana Citation2019). The ‘anchor of decolonial epistemologies’ is starting from ‘I am where I do and think’ (Mignolo Citation2011a), in our case, meant locating a course about Global education development in Finland. In our reflections, we deliberated on the ways in which our decolonial ambitions were not fully realised because of certain structural factors as well as coloniality within us. As we are beneficiaries of funding from UniPID and the university, we are therefore beholden to certain stipulations. We also recognise the paradox that the university, as an institution with colonial roots, is the institution which funds our decolonial initiative. Making structural changes to the assessment and organisation of the course would mean asking UniPID and the university to rethink how courses are envisioned and to invite dialogue with our colleagues, especially those in leadership positions, which would require much more time and collective effort.

By centering decoloniality in this course on Global education development we aspired to move away from the banking model of education to a problem-posing method where students had to engage with a major portion of the content independently without being coddled by the teachers (Freire Citation1970). We expected our pedagogy, which allowed the students a great deal of independence in determining the times and materials they used to engage with the course, to disrupt the teacher-student hierarchy that traditionally exists in higher education. However, our experience was that the students in fact felt like they were isolated because of the limited synchronous sessions and interactions with other participants (Charbonneau Citation2020). In contrast to the isolation the students felt, we as teachers and researchers experienced a growth in our coalitions, coalescing with each other and bringing together researchers and scholars from other contexts to participate in the course. On the basis of our reflections and Charbonneau’s (Citation2020) study, we wonder about the ways in which we can build trust, a sense of community and be vulnerable with students, particularly in virtual courses (Mangione and Norton Citation2020) and especially when for the students the course runs over a period of weeks, while our teacher-researcher collaborations have developed over years. Although we did not share our struggles and dilemmas with the students, in our discussions with one another, we shared them quite openly. Our ambivalence about the practice of vulnerability was connected to our roles in preserving the institutional power structures of the university.

In our dialogues, we noted that the lack of Sámi and Roma scholarship from this course continue decolonial patterns of omissions, silence and absence. We were not successful in incorporating the voices of the indigenous scholars based in Finland though we coalesced with individuals from different contexts in the course. We could have made more effort to include their epistemologies and ontologies as we imagine a decolonial development education to participate in acknowledging the harm done to indigenous people and ways in which development education can genuinely work towards restitution (Legg Citation2017; Mignolo and Walsh Citation2018). We see decolonial pedagogy as being about our role as teachers in the cultivation and construction of knowledge. This includes thinking about who gets to speak authoritatively about education development and whose accounts are presented in class as worthy of investigation, comparison and interrogation. As the decolonial school of thought presents critiques and proposals of liberation from the margins rather than privileged sites of knowledge production such as the university, we recognise that we could have done more to invite and collaborate with individuals working on decolonial options outside academic circles (Asher Citation2013).

As Tuck and Wayne Yang (Citation2012) remind us, decolonisation always involves affirmative practice; in the case of development education this includes engagement in a constant struggle to address ‘both the material and discursive aspects of representation and politics in curricula, among students and educators, and beyond the classroom’ (Sultana Citation2019, 38). Our work therefore is a practice of the possible, and we recognise that we have benefited from a supportive climate at the university: working within the Faculty of Education at the University of Oulu allowed us the possibility to include the non-dominant approach of decoloniality in our course because of the precedent set by critical and intercultural scholars in our faculty.

For us the question remains, can we de-link from coloniality in a course on global education development when the SDGs are the central reference point and pillar of the course? From the liberal perspective, racialisation and capitalism have become emancipatory perspectives from which to critique the normative universal framework. To embrace the decolonial option would be to begin otherwise, deconstructing the axes of race and capitalism which undergird the colonial matrix of power.

Epilogue

At the time of writing this dialogic inquiry it has been almost a year since we offered the first course on global development education through the UniPID network, which was the focus of this paper. There have been two more iterations of the course and we are currently working with our third cohort of students. These three offerings of the course have provided us teachers with so many opportunities to think with our students about what it means to think about education development with other eyes. We have made a conscious attempt to listen to the students’ feedback and have modified the course in various ways. In the second offering of the course, we invited guests to respond to some of the major themes arising from students’ learning diaries to maintain a continuity in the dialogue in terms of their reflections. To build a sense of community within the course, we have now organised biweekly reflective reading sessions. We have had opportunities to coalesce with colleagues including indigenous scholars from the Nordics and other parts of the world. We have also had poetry reading as part of these sessions which opened possibilities to talk about our positionalities and has in turn inspired some of the students to reflect more deeply on issues that they are passionate about in the field of education development. We continue to struggle, reflect and learn from our entanglements with coloniality and the intricate and contradictory nature of how we understand and interpret decoloniality as part of the university structure, and moreover of university teaching and learning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In this paper, we use ‘Global education development’ to refer to our course and ‘global education development’ to refer to the concept in a broader sense.

2 ‘Education and International Development: An Introduction’ edited by Tristan McCowan and Elaine Unterhalter was the course textbook which provides an overview, historical origins of education development and the major trends in the field.

3 For more information on the virtual courses offered by UniPID, check https://www.unipid.fi/students/virtual-studies/

4 ECTS is the European Credits Transfer and Accumulation System in which 1 ECTS credit correspond to 25–30 h of study. In Finland, 1 ECTS credit = 27 h of study; 25 ECTS is the equivalent of 675 h of study

5 Finland has an ambivalent relation to colonization, for being both occupied by foreign kingdoms and built on racialized conception of nationhood. Under the Swedish rule, Finns were subject to racialized stereotypes and a lower status in the hierarchy as being descendents of the Mongols. Later, the Fennoman movement, emerging as a movement for nationhood and autonomy, produced the imaginary of Finland as a unified nation of people, and also explicitly defines this as a nation of white europeans speaking the Finnish language. This meant the exclusion of the indigenous Sàmi people and Roma people. It has been later coupled with the marginalization of racialized immigrant communities since the 1990s.

6 In ‘Decolonial methodologies in education’, Zavala (Citation2016) elaborates on three decolonial strategies used in education – 1) Counter/Storytelling 2) Healing 3) Reclaiming. All these strategies emphasise community self-determination and includes generative praxis that brings ancestral knowledges together with local, endogenous knowledges to create decolonial educational spaces.

7 ‘Shouldering our colonial backpack’ (2016) is a video produced by Center for Global Learning in Schools where post/decolonial scholar Vanessa Andreotti is interviewed by Sonja Richter. The conversation focuses on the implications of using postcolonial theory in education and thereby understand the ways in which educators can engage with the discomfort of unlearning harmful patterns of colonialism within education.

8 ‘Global Education in Europe … Development’ by Nygaard and Wegimont (Citation2018) is a policy paper written for the Global Education Network Europe (GENE) which outlines how Global Education is defined and conceptualised by international organisations as well as the different EU member states.

9 This feedback by the student made us reflect on the citational politics. While we understand that the mechanical process of APA-style citation which is commonly used in our faculty is not colonial in itself, it makes us reflect on which types of work/knowledge that attains the status of legitimacy to be included in peer-reviewed journals and thereby be part of courses like Global education development.

10 The Global Education Monitoring Report (GEM Report) prepared by an independent team of scholars is published by UNESCO. It monitors progress towards SDG 4. The annual GEM Report provides an evidence-based overview of education development globally with the emphasis on quality. https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/about

11 The article ‘Colonial Complicity: The ‘Post-colonial’ in a Nordic context’ by Vuorela (Citation2009) discusses the ways which Finland participated and benefited from the colonial system even though there is a general perception of Finnish colonial innocence as Finland did not officially colonise countries and was colonised by Sweden and Russia. Vuorela (Citation2009) gives the examples of story books, anthropology research, development work and joining the European Union (EU) to highlight how dominant colonial worldview is perpetuated in Finland through these different sources.

12 ‘Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary’ by Kothari et al. (Citation2019) consists of over one hundred essays focusing on alternatives to current hegemonic models of development around the world with contributions from multiple contexts. The book argues that unless we staunchly challenge the liberal idea of the linear progression of development, we will not be able to think and open pathways for alternative ways of living and being in harmony with the environment.

References

- Andreotti, Vanessa de Oliveira. 2011. “(Towards) Decoloniality and Diversality in Global Citizenship Education.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 9 (3-4): 381–397.

- Asher, Kiran. 2013. “Latin American Decolonial Thought, or Making the Subaltern Speak.” Geography Compass 7 (12): 832–842.

- Atehortúa, Juan Velásquez. 2020. “A Decolonial Pedagogy for Teaching Intersectionality.” Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE) 4 (1): 156–171.

- Boveda, Mildred, and Kakali Bhattacharya. 2019. “Love as de/Colonial Onto-Epistemology: A Post-Oppositional Approach to Contextualized Research Ethics.” The Urban Review 51 (1): 5–25.

- Charbonneau, Irène. 2020. “Social Presence And Educational Technologies In An Online Distance Course In Finnish Higher Education - A Social-Constructivist Perspective.” (Masters thesis) Stockholm University, http://su.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1506466/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Cusicanqui, Silvia Rivera. 2012. “Ch'ixinakax Utxiwa: A Reflection on the Practices and Discourses of Decolonization.” South Atlantic Quarterly 111 (1): 95–109.

- De Lissovoy, Noah. 2010. “Decolonial Pedagogy and the Ethics of the Global.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 31 (3): 279–293.

- de Sousa Santos, Boaventura. 2018. The end of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of age of Epistemologies of the South. Durham: Duke University Press.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. 2019. “Being Black in the EU: Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey.” https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2018/being-black-eu.

- Freire, Paulo. 1970. “The Adult Literacy Process as Cultural Action for Freedom.” Harvard Educational Review 40 (2): 205–225.

- Juusola, Henna. 2020. “Perspectives on Quality of Higher Education in the Context of Finnish Education Export.” (PhD dissertation) Tampere University. https://trepo.tuni.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/123165/978-952-03-1679-2.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

- Kothari, Ashish, Ariel Salleh, Arturo Escobar, Federico Demaria, and Alberto Acosta. 2019. “Pluriverse.” A Post-Development Dictionary. New Dehli: Tulika Books.

- Legg, Stephen. 2017. “Decolonialism.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42 (3): 345–348.

- Lehtola, V. 2015. “Sámi Histories, Colonialism, and Finland.” Arctic Anthropology 52: 22–36.

- Mangione, Daniela, and Lin Norton. 2020. “Problematising the Notion of ‘the Excellent Teacher’: Daring to be Vulnerable in Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1812565.

- McCowan, Tristan. 2015. “Theories of Development.” In Education and International Development: An Introduction, edited by Tristan McCowan, and Elaine Unterhalter, 31–48. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- McCowan, Tristan, and Elaine Unterhalter, eds. 2015. Education and International Development: An Introduction. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Mignolo, Walter. 2011a. The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Mignolo, Walter D. 2011b. “Epistemic Disobedience and the Decolonial Option: A Manifesto.” Transmodernity 1 (2): 3–23.

- Mignolo, Walter D. 2011c. “Geopolitics of Sensing and Knowing: on (de) Coloniality, Border Thinking and Epistemic Disobedience.” Postcolonial Studies 14 (3): 273–283.

- Mignolo, Walter D., and Catherine E. Walsh. 2018. On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Morreira, Shannon. 2017. “Steps Towards Decolonial Higher Education in Southern Africa? Epistemic Disobedience in the Humanities.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 52 (3): 287–301.

- Nygaard, Arnfinn, and Liam Wegimont. 2018. “Global Education in Europe–Concepts, Definitions and Aims in the Context of the SDGs and the New European Consensus on Development.” Global Education Network Europe 1–54.

- Pashby, Karen, and Louise Sund. 2020. “Decolonial Options and Challenges for Ethical Global Issues Pedagogy in Northern Europe Secondary Classrooms.” Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education 4 (1): 66–83.

- Quijano, Anibal. 2000. “Coloniality of Power and Eurocentrism in Latin America.” International Sociology 15 (2): 215–232.

- Rastas, Anna. 2004. “Am I Still ‘White'? Dealing with the Colour Trouble.”.

- Rastas, Anna. 2019. “The Emergence of Race as a Social Category in Northern Europe.” In Relating Worlds of Racism, pp. 357-381. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rutazibwa, Olivia. 2018. “On Babies and Bathwater: Decolonizing International Development Studies.” In Decolonization and Feminisms in Global Teaching and Learning, edited by Sara de Jung, Rosalba Icaza, and Olivia Rutazibwa, 158–180. London: Routledge.

- Schatz, Monica. 2016. Education as Finland’s Hottest Export.” In A Multi-Faceted Case Study on Finnish National Education Export Policies Helsingin Yliopisto.

- Schatz, Monika, Ana Popovic, and Fred Dervin. 2017. “From PISA to National Branding: Exploring Finnish Education®.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 38 (2): 172–184.

- Silva, Janelle M. 2018. “and Students for Diversity Now. “#WEWANTSPACE: Developing Student Activism Through a Decolonial Pedagogy.”.” American Journal of Community Psychology 62 (3-4): 374–384.

- Stein, Sharon. 2019. “Beyond Higher Education as we Know it: Gesturing Towards Decolonial Horizons of Possibility.” Studies in Philosophy and Education 38 (2): 143–161.

- Sultana, Farhana. 2019. “Decolonizing Development Education and the Pursuit of Social Justice.” Human Geography 12 (3): 31–46.

- Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. 2012. “Decolonization is not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 (1): 1–40.

- “UniPID” Finnish University Partnership for International Development. 2021. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://www.unipid.fi/.

- Unterhalter, Elaine.. 2015. “Education and International Development: A History of the Field.” In Education and International Development: An Introduction, edited by Tristan McCowan and Elaine Unterhalter, 13–29. London: Boomsbury Publishing.

- Vaidya, A. 2016. “Does Critical Thinking Education Have a Western Bias? A Case Study Based on Contributions from the Nyāya Tradition of Classical Indian Philosophy.” Journal of Philosophy of Education 50 (2): 132–160.

- Vandermensbrugghe, Joelle. 2004. “The Unbearable Vagueness of Critical Thinking in the Context of the Anglo-Saxonisation of Education.” International Education Journal 5 (3): 417–422.

- Vuorela, Ulla. 2009. “Colonial Complicity: The ‘Postcolonial’ in a Nordic Context.” In Complying with Colonialism: Gender, Race, and Ethnicity in the Nordic Region, edited by Suvi Keskinen, Salla Tuori, Sari Irni, and Diana Mulinari, 19–33. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Walsh, Catherine E. 2015. “Decolonial Pedagogies Walking and Asking. Notes to Paulo Freire from AbyaYala.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 34 (1): 9–21.

- Zavala, Manuel. 2016. “Decolonial Methodologies in Education.” Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory 361–366.