ABSTRACT

This provocation shows how five emerging digital citizenship regimes are rescaling European nation-states through a taxonomy: (i) the globalised/generalisable regime called pandemic citizenship that clarifies how post-COVID-19 datafication processes have amplified the emergence of four digital citizenship regimes in six city-regions; (ii) algorithmic citizenship (Tallinn); (iii) liquid citizenship (Barcelona/Amsterdam); (iv) metropolitan citizenship (Cardiff); and (v) stateless citizenship (Barcelona/Glasgow/Bilbao). I argue that this phenomenon should matter to us insofar as these emerging digital citizenship regimes have resulted in nation-state space rescaling, challenging its heretofore privileged position as the only natural platform for the monopoly of technopolitical and sensory power.

Rescaling European nation-states in postpandemic technopolitical democracies

The flagship Big Tech firms of surveillance capitalism (Zuboff, Citation2019), such as Google and Facebook, have already assumed many functions previously associated with the nation-state, from cartography to citizen surveillance, which has deterritorialised, liquified, and datafied citizenship (Amoore, Citation2021, Citation2022; Aradau & Blanke, Citation2021; Calzada, Citation2020a, Citation2021a; Orgad & Baübock, Citation2018) and thus posed the question around the need to better articulate postpandemic technopolitical democracies in Europe (Calzada & Ahedo, Citation2021; Goodman, Citation2022). At the same time, this pervasive process has resulted in nation-state space rescaling, undermining its heretofore privileged position, so far, the only natural platform and geographical expression for the monopoly of sensory power (Isin & Ruppert, Citation2020; Moisio et al., Citation2020), and further creating technopolitical and city-regional dynamics inside states’ borders while paradoxically reinforcing the external borders (Allen, Citation2020; Chouliaraki & Georgiou, Citation2022). Hence, as Jessop anticipated (Citation1990) and as exacerbated in postpandemic times, the territorial coincidence of European nation-states, governing order, economy, (digital) citizenship, and identity can no longer be taken for granted.

Consequently, as I see it, European nation-states cannot fully interpret the changing regimes and patterns of digital citizenship since, within nation-states, city-regional governments often behave differently by claiming a say in digitally affected socio-economic and socio-political policy matters (Mitchell, Citation1991; Taylor, Citation1994). These technopolitical matters have given rise to an urge to systematically address the question of whether and to what extent ubiquitous dataveillance is compatible with citizens’ digital being in European nation-states (Isin & Ruppert, Citation2015). Such matters cover demands for not only data privacy, ownership, sovereignty, donation, co-operation, self-determination, trust, access, and ethics but also AI transparency, algorithmic automatization, and, ultimately, democratic accountability for digital citizenship, which may inevitably transform the current interpretation of the nation-state as ‘the clear and coherent mapping of a relatively culturally homogeneous group onto a territory with a singular and organized state apparatus of rule’ (Agnew, Citation2017, p. 347) and its relationship with digital citizenship (Mossberger et al., Citation2007).

Against this backdrop of the implementation of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe – unlike in the US and China – a debate emerged on the role of citizens and their relationship with data and algorithms, extending beyond nation-states and playing out primarily in European city-regions (Calzada, Citation2015). The emergence of algorithmic disruption has spurred a call to action for city-regions in Europe, establishing the need to map out the technopolitical debate on datafication processes or dataism, Big Data’s deterministic ideology (Harari, Citation2018; van Dijck, Citation2014). Moreover, this disruption has highlighted the potential requirements for establishing regulatory frameworks to protect citizens’ digital rights in city-regions (Calzada, Citation2021b; Calzada et al., Citation2021) and facilitate data sovereignty, altruism, and donations through data co-operatives (Calzada, Citation2020b, Citation2021c).

In these unprecedented postpandemic biopolitical times, these requirements may have pervasively fostered new modes of being a digital citizen (Isin & Ruppert, Citation2015) in certain urban areas while unwittingly or deliberately contributing to rescaling the nation-state in Europe (Keating, Citation2013). On the one hand, regarding the technopolitical awareness of data, these dynamics involve addressing concerns about biometric technologies (e.g. vaccine passports), rolling out algorithmic identity tools for citizenship (e.g. the ongoing e-Residency policy framework) and engaging in counter-reaction to extractivist data models (e.g. through digital rights claims). On the other hand, the dynamics relate to the increasing socio-economic re-foundational awareness and counterreaction (e.g. through internal post-Brexit response in Wales), city-regional self-confidence through community empowerment (e.g. through data co-operatives), and socio-political self-determination through devolution (and independence) and demands in favour of the right to decide (e.g. on indigenous data sovereignty; Hummel et al., Citation2021).

Hence, in this provocation piece, I argue that several emerging digital citizenship regimes in European city-regions may be pervasively rescaling European nation-states. As such, the current pandemic crisis is pervasively related to data and algorithmic governance issues that expose pandemic citizens to vulnerability from a potential surveillance nation-state. At this stage, the debate at least in Europe – acknowledging significant variations in digital/data regulatory and legal frameworks, as known as digital constitutionalism across world regions – regarding urban liberties, digital rights, and cybercontrol, has led some pandemic citizens to consider postpandemic society one of control, with abundant critique on this topic flourishing from the cybernetic and disease surveillance perspectives.

Emerging digital citizenship regimes

Hyperglobalist scholars forecast the imminent demise of national state power, and consequently borders, because of the purportedly borderless, politically uncontrollable forces of global economic integration (Ohmae, Citation1995). In contrast, a growing body of literature on state rescaling and associated state spaces and practices provides a strong counterargument: that national states are being qualitatively transformed – not eroded or dismantled – under contemporary capitalist conditions (Brenner, Citation2009). Rescaling is defined by Keating as ‘the migration of various systems of new levels, above, below, and across the bounded nation-state’ (Keating, Citation2013, p. 6). Moreover, the current postpandemic crisis (and even in the dramatic aftermath of Ukraine’s invasion) is increasingly showing that the more nation-states are reinforced, the more pandemic citizens’ lives seem to be datafied or liquified (Bauman, Citation2000). This technopolitical liquified dynamic means that citizens’ uncontrollable algorithmic exposure, which translates to massive digital (and even physical) vulnerability, is being combined with a lack of civil liberties and constant limitations on the freedom of movement (Dumbrava, Citation2017).

Moreover, recent postpandemic biopolitical dynamics demand further empirical, timely, and ambitious transdisciplinary research on the right to algorithmic transparency, borderless residency (i.e. Tallinn), digital rights and privacy (i.e. Barcelona and Amsterdam), data co-operatives (i.e. Cardiff), donation and altruism, data sovereignty (i.e. Glasgow, Bilbao, and Barcelona), and overall democratic city-regional accountability. Such approaches have advanced existing knowledge of the relationship between the rescaling of European nation-states and the emergence of new forms of emancipatory citizenship in Europe beyond the formal state citizenship (Arrighi & Stjepanović, Citation2019).

A taxonomy of emerging digital citizenship regimes

‘Digital citizenship is typically defined through people’s action, rather than by their formal status of belonging to a nation-state and the rights and responsibilities that come with it’ (Hintz et al., Citation2017, p. 731). Nonetheless, the notion of citizenship could be problematized further by including not only bottom-up and emancipatory approaches as this article adopt but also a formal, conventional, longstanding, passive, and top-down conceptualisations of the digital economy (Zuboff, Citation2019) that define citizenship as a set of rights and obligations accorded to individuals by a formal and established constitution of a specific nation-state. These top-down perspectives stem from the field known as digital constitutionalism (Celeste, Citation2019; De Gregorio, Citation2022; Suzor, Citation2018), which refer to the eminently European nation-states’ regulatory framework on digital and data policies, neither considering the emancipatory approach of individuals striving digital rights (Calzada, Citation2021b) nor the counter-reaction from city-regions. Among the many perspectives on digital citizenship (Couldry et al., Citation2014; McCosker et al., Citation2016; Moraes & Andrade, Citation2015; Mossberger et al., Citation2007), this article conceptually frames the taxonomy around the emancipatory push by individuals and city-regions in their proactive attempt to rescale nation-states towards self-expression and the articulation of the digital rights for which they have not been accorded.

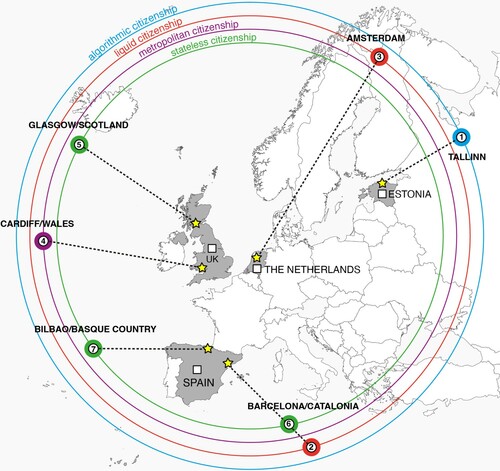

Consequently, this provocation aims to challenge the existing interpretation of how five emerging digital citizenship regimes are actively, collectively, and ubiquitously rescaling the current conceptualisation of European nation-states in relation to datafied and surveillance societies. To provide several pieces of evidence and thus to spark a debate, this provocation presents a highly generalisable, emerging, globalised digital citizenship regime called (i) pandemic citizenship (Calzada, Citation2020a, Citation2021a, Citation2022) as well as four unique, non-generalisable, and interrelated emerging citizenship regimes that are technopoliticised and city-regionalised, identifying and examining them in certain urban areas. Overall, pandemic citizenship is a necessary and novel term insofar as state-citizenship relations have been highly mediated through data and algorithms in the postpandemic era by demanding in-depth examination of the transformations in several digital citizenship regimes (Tammppu et al., Citation2022). The remaining regimes are (ii) algorithmic, (iii) liquid, (iv) metropolitan, and (v) stateless citizenship; these intertwined citizenship regimes are not necessarily mutually exclusive and overlap to greater or lesser degrees (Isin & Turner, Citation2007; Turner, Citation2017) ().

Pandemic citizenship represents digital citizens on permanent alert – with reduced mobility patterns, 24/7 hyper-connectedness, and conscious or unconscious effects of a globalised interdependence – sharing not only fears, uncertainties, and risks, but also postpandemic resilient life strategies (even beyond nation-states’ borders). A generalisable and globalised regime of digital citizenship is driven by COVID-19 and results in several rescaling outcomes, such as contact tracing apps, biometric technologies, vaccine passports, and vaccine nationalism. The rescaling of nation-states occurs by constraining borderless mobility and employing constant tracking and biometric surveillance of pandemic citizens while strengthening and permanently solidifying nation-state borders (Calzada, Citation2021a, Citation2022; Calzada & Bustard, Citation2022; Cheney-Lippold, Citation2017; Foucault, Citation2003).

Figure 1. Non-generalisable Emerging Digital Citizenship Regimes in Europe: Algorithmic (Tallinn), Liquid (Barcelona/Amsterdam), Metropolitan (Cardiff), and Stateless (Barcelona/Glasgow/Bilbao).

Algorithmic citizenship is instantiated in decentralised blockchain ledgers implemented by the small state of Estonia through its e-Residency programme, particularly in Tallinn as the leading avant-garde entrepreneurial urban hub impacting the networking structures of global urban spaces. This programme offers non-residents, independent of their citizenship and place of residence, remote access to Estonia’s well-advanced digital infrastructure and e-services via government-supported digital identity documents issued in the form of a smart identity card (e-Resident ID). This non-generalisable digital citizenship regime is driven by blockchain, resulting in the following rescaling outcomes: e-Residence and digital identity programmes (Atzori, Citation2017; Calzada, Citation2018a).

Liquid citizenship is represented, in the aftermath of the GDPR, by citizenship in city-regions such as Amsterdam and Barcelona in Europe – alongside New York in the US – that counter-reacted against dataism by launching the Cities’ Coalition for Digital Rights, a joint initiative to claim, promote, and track progress in protecting citizens’ digital rights to revert the extractivism of data-opolies. This non-generalisable digital citizenship regime is driven by dataism, resulting in digital rights and privacy rescaling outcomes. Rescaling occurs from 50 global ‘people-centered smart cities’ that actively advocate for digital rights (Calzada, Citation2018b, Citation2021b, Citation2021d; Calzada et al., Citation2021).

In the aftermath of Brexit, metropolitan citizenship is represented through the Foundational Economy paradigm in Cardiff (Wales), which provides a way to socio-economically re-empower city-regional communities. This non-generalisable digital citizenship regime is driven by Brexit, resulting in Radical Federalism from Cardiff in Wales. Rescaling thus occurs via socio-economically empowering city-regional communities through data co-operatives (Calzada, Citation2020b, Citation2021c) as the recent Senedd deal between Welsh Labour and Plaid Cymru attempts to foster.

Stateless citizenship is represented through socio-political claims for the devolution of powers to diverse and distinct degrees in Glasgow, Barcelona, and Bilbao. This non-generalisable digital citizenship regime is driven by devolution, resulting in the right to decide and data sovereignty rescaling outcomes (Calzada, Citation2018c, Citation2019). Despite different pathways in the three cases, data sovereignty is a joint demand by local authorities and regional governments as recently revealed through research findings collected about Barcelona/Catalonia and Glasgow/Scotland around the role of the public sector in regulating AI and promoting data and platform co-operatives (Calzada et al., Citation2021).

Final remark

The digital citizenship regimes pervasively emerging in several European city-regions should matter to us, for the nature of rescaling of nation-states, as briefly presented in this provocation piece, remains scarcely examined through the present bio-political, technopolitical, and city-regional transdisciplinary perspective. This piece aims to encourage more discussion on the methodological globalism and state-geographies to help further examine nation-state rescaling and digital citizenship relations. At the same time, this discussion poses methodological globalism-related challenges for contemporary political geography, critical data science, digital studies, social innovation, and regional studies. Methodological globalism is ‘a tendency for social scientists to prioritize the analysis of globalization processes over and above knowledge of the variety of socio-spatial structures, processes, and practices that shape state forms and functions at various territorial scales’ (Moisio et al., Citation2020, p. 14). Therefore, I suggest the following future research avenues around the digital citizenship and state-geographies nexus: (i) indigenous geographies and digital rights, (ii) datafication and digitalisation, (iii) state-citizens relationship, and (iv) thinking beyond the state, operationalising the cutting-edge term algorithmic nation (Calzada, Citation2018a; Calzada & Bustard, Citation2022).

In conclusion, I have argued that the five intertwined emerging digital citizenship regimes discussed here – pandemic, algorithmic, liquid, metropolitan, and stateless – are significant and should thus matter to us, in Europe and across other world regions, for two key reasons:

First, the regimes are novel, dynamic, and real-time representations of the permanent reconstitution processes of digital citizenship within nation-states in liberal democracies, attempting to overcome the conventional static analysis of the increasingly brittle relationship between citizenship and the state by suggesting nuanced explanations featuring a diverse set of drivers fuelling the rescaling (e.g. COVID-19, blockchain, dataism, Brexit, and devolution).

Second, and consequently, the regimes are constantly in flux and rescaling nation-states in an unexpected fashion by altering technopolitical and city-regional configurations that directly affect digital citizenship by either undermining or bolstering citizens’ rights to have digital rights. As a result of this rescaling of nation-states in Europe, since external borders are solidifying while citizens’ lives are liquifying and the influence of digital forms of being is increasing, the concept of citizenship is in flux (Bauman, Citation2000); in this context, the urban scale is a quintessential setting to investigate the global swing towards pandemic citizenship regimes and forms.

In sum, the overview of the conceptual taxonomy introduced here offers a window into navigating citizenship during the uncertain postpandemic times in Europe. The examination of these current regimes does not offer generalisable results but instead provides a potential path to follow in extending this taxonomy across Europe and other world regions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Igor Calzada

Dr Igor Calzada, MBA, FeRSA (www.igorcalzada.com/about) is a Senior Researcher working in smart city citizenship, benchmarking city-regions, digital rights, data co-operatives, and digital citizenship; since 2021 at WISERD (Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research and Data), Civil Society Research Centre ESRC, SPARK (Social Science Research Park), Cardiff University and since 2012 at the Future of Cities and Urban Transformations ESRC Programme, University of Oxford funded by EC-H2020-Smart Cities and Communities and EC-Marie Curie-CoFund-Regional Programmes. He has been awarded a Fulbright Scholar-in-Residence (SIR) by US-UK Commission at California State University, Bakersfield (https://wiserd.ac.uk/news/dr-igor-calzada-awarded-fulbright-scholar-in-residence/). He has been nominated among 100 Most Influential Academics in Government by Apolitical (https://apolitical.co/list/en/apoliticals-100-most-influential-academics-in-government/). Additionally, he served as Senior Advisor to UN-Habitat in Digital Transformations for Urban Areas, People-Centered Smart Cities. Previously, he worked at the DG Joint Research Centre, European Commission as Senior Scientist in Digital Transformations and AI. He has more than 20 years of research/policy experience as Senior Lecturer/Researcher in several universities worldwide and in public and private sector as director. Publications: 56 journal articles; 13 books; 22 book chapters; 27 policy reports; 150 international keynotes; and 33 media articles. His new book is entitled ‘Emerging Digital Citizenship Regimes: Postpandemic Technopolitical Democracies’ (Calzada, Citation2022).

References

- Agnew, J. (2017). The tragedy of the nation-state. Territory, Politics, Governance, 5(4), 347–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2017.1357257

- Allen, J. (2020). Power’s quiet reach and why it should exercise US. Space and Polity, 24(3), 408–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2020.1759412

- Amoore, L. (2021). The deep border. Political Geography, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102547

- Amoore, L. (2022). Machine learning political orders. Review of International Studies, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210522000031

- Aradau, C., & Blanke, T. (2021). Algorithmic reason: The new government of self and other. Oxford University Press.

- Arrighi, J.-T., & Stjepanović, D. (2019). Introduction: The rescaling of territory and citizenship in Europe. Ethnopolitics, 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2019.1585087

- Atzori, M. (2017). Blockchain technology and decentralized governance: Is the state still necessary? Journal of Governance and Regulation, 6(1), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.22495/jgr_v6_i1_p5

- Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid modernity. Polity.

- Brenner, N. (2009). Open questions on state rescaling. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 2(1), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp002

- Calzada, I. (2015). Benchmarking future city-regions beyond nation-states. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2(1), 351–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2015.1046908

- Calzada, I. (2018a). ‘Algorithmic nations’: Seeing like a city-regional and techno-political conceptual assemblage. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 5(1), 267–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2018.1507754

- Calzada, I. (2018b). (Smart) citizens from data providers to decision-makers? The case study of Barcelona. Sustainability, 10(9), 3252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093252

- Calzada, I. (2018c). Metropolitanising small European stateless city-regionalised nations. Space and Polity, 22(3), 342–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2018.1555958

- Calzada, I. (2019). Catalonia rescaling Spain: Is it feasible to accommodate its “stateless citizenship”? Regional Science Policy & Practice, 11(5), 805–820. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12240

- Calzada, I. (2020a). Emerging citizenship regimes and rescaling (European) nation-states: Algorithmic, liquid, metropolitan and stateless citizenship ideal types. In S. Moisio, N. Koch, A. E. G. Jonas, C. Lizotte, & J. Luukkonen (Eds.), Handbook on the changing geographies of the state: New spaces of geopolitics (pp. 368–384). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788978057.00048.

- Calzada, I. (2020b). Platform and data co-operatives amidst European pandemic citizenship. Sustainability, 12(20), 8309. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208309

- Calzada, I. (2021a). Emerging digital citizenship regimes: Pandemic, algorithmic, liquid, metropolitan, and stateless citizenships. Citizenship Studies, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2021.2012312

- Calzada, I. (2021b). The right to have digital rights in smart cities. Sustainability, 13(20), 11438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011438. Special issue ‘social innovation in sustainable urban development.’

- Calzada, I. (2021c). Data co-operatives through data sovereignty. Smart Cities, 4(3), 1158–1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities4030062 Special issue ‘feature papers for smart cities.’

- Calzada, I. (2021d). Smart city citizenship. Elsevier Science Publishing Co Inc.

- Calzada, I. (2022). Emerging digital citizenship regimes: Postpandemic technopolitical democracies. Bingley: Emerald Points.

- Calzada, I., & Ahedo, I. (2021). Postpandemic technopolitical democracies. Frontiers in Political Science – Politics of Technology. Online: https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/28882/postpandemic-technopolitical-democracies

- Calzada, I., & Bustard, J. (2022). The dilemmas around digital citizenship in a post-Brexit and post-pandemic Northern Ireland: Towards an Algorithmic Nation? 25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2022.2026565.

- Calzada, I., Pérez-Batlle, M., & Batlle-Montserrat, J. (2021). People-centered smart cities: An exploratory action research on the cities’ coalition for digital rights. Journal of Urban Affairs, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2021.1994861

- Celeste, E. (2019). Digital constitutionalism: A new systematic theorisation. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 33(1), 76–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600869.2019.1562604

- Cheney-Lippold, J. (2017). We are data: Algorithms and the making of our digital selves. New York University Press.

- Chouliaraki, L., & Georgiou, M. (2022). The digital border: Migration, technology, power. NYU Press.

- Couldry, N., Stephansen, H., Fotopoulou, A., MacDonald, R., Clark, W., & Dickens, L. (2014). Digital citizenship? Narrative exchange and the changing terms of civic culture. Citizenship Studies, 18(6-7), 615–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2013.865903

- De Gregorio, G. (2022). Digital constitutionalism in Europe: Reframing rights and powers in the algorithmic society. Cambridge University Press.

- Dumbrava, C. (2017). Citizenship and technology. In A. Shachar, R. Bauböck, I. Bloemraad, & M. Vink (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of citizenship (pp. 767–788). OUP.

- Foucault, M. (2003). Society must be defended: Lectures at the college de France, 1975-76. Picador.

- Goodman, S. W. (2022). Citizenship in hard times: How ordinary people respond to democratic threat. Cambridge University Press.

- Harari, Y. N. (2018). 21 lessons for the century. Vintage.

- Hintz, A., Dencik, L., & Wahl-Jorgensen, K. (2017). Digital citizenship and surveillance society. International Journal of Communications, 11, 731–739. http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5521

- Hummel, P., Braun, M., Tretter, M., & Dabrock, P. (2021). Data sovereignty: A review. Big Data & Society, 8(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720982012

- Isin, E., & Ruppert, E. (2015). Being digital citizens. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Isin, E., & Ruppert, E. (2020). The birth of sensory power: How a pandemic made it visible? Big Data & Society, 7(2), 205395172096920–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720969208

- Isin, E., & Turner, B. S. (2007). Investigating citizenship: An agenda for citizenship studies. Citizenship Studies, 11(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621020601099773

- Jessop, B. (1990). State theory: Putting the capitalist state in its place. Polity Press.

- Keating, M. (2013). Rescaling the European state: The making of territory and the rise of the meso Oxford. Oxford University Press.

- McCosker, A., Vivienne, S., & Johns, A. (2016). Negotiating digital citizenship: Control, contest and culture. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Mitchell, T. (1991). The limits of the state: Beyond statist approaches and their critics. American Political Science Review, 85(1), 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055400271451

- Moisio, S., Jonas, A. E. G., Koch, N., Lizotte, C., & Luukkonen, J. (2020). Handbook on the changing geographies of the state: New spaces of geopolitics. Edward Elgar.

- Moraes, J., & Andrade, E. (2015). Who are the citizens of the digital citizenship? The International Review of Information Ethics, 23(11), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.29173/irie227

- Mossberger, K., Tolbert, C. J., & McNeal, R. S. (2007). Digital citizenship: The internet, society, and participation. MIT Press.

- Ohmae, K. (1995). The end of the nation-state: The rise of regional economies. Simon and Schuster Inc.

- Orgad, L., & Baübock, R. (2018). Cloud communities: The drawn of global citizenship? EUI.

- Suzor, N. (2018). Digital constitutionalism: Using the rule of law to evaluate the legitimacy of governance by platforms. Social Media + Society, 4(3), 205630511878781–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118787812

- Tammppu, P., Masso, A., Ibrahimi, M., & Abaku, T. (2022). Estonian e-Residency and conceptions of platform-based state-individual relationship. Trames, 26(76/71), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.3176/tr.2022.1.01

- Taylor, P. J. (1994). The state as container: Territoriality in the modern world-system. Progress in Human Geography, 18(2), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/030913259401800202

- Turner, B. S. (2017). Contemporary citizenship: Four types. Journal of Citizenship and Globalisation Studies, 1(1), 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1515/jcgs-2017-0002

- van Dijck, J. (2014). Datafication, dataism and dataveillance: Big data between scientific paradigm and ideology. Surveillance & Society, 12(2), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v12i2.4776

- Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. Profile.