ABSTRACT

The existence of an uncovered liability has historically benefited foreign banks and lead currencies. Using the case of China’s efforts to fund its foreign exchange needs by exploiting loopholes in the international financial architecture, the paper examines whether using state-owned settlement banks as a means of intermediating a specialised ‘non-deliverable’ financial asset in offshore markets can substitute the institutional and technical prerequisites that developing economies typically lack. The findings show that while offshore money markets can reduce US dollar dependency in areas such as trade invoicing that do not depend on currency delivery, increasing the offshore holdings of RMB is more challenging. The reasons for this are to be found in the way the governance, geographic and credit generating limitations of state settlement banks reinforce the constraints imposed by the uncovered liability problem. The findings distinguish the historical evolution of the RMB’s offshore use from other offshore markets and reinforce the impossibility of separating issues related to trade infrastructures from those related to the structure of the international financial system.

Introduction

Economic historians have documented the rise and fall of currencies (Cohen Citation1971, Schenk Citation2010). While monetary history shows an association between strong nations and currencies (Goodhart Citation1998), the dominance of the US dollar creates an exorbitant privilege that subsidises US living standards (Eichengreen Citation2011). It also raises the question as to the mechanisms through which China’s emergence as a geopolitical force can lead to an increase in the international use of the renminbi (RMB) (e.g. McNally and Gruin Citation2017)? History indicates that this is a formidable task (Cohen Citation2012) while the literature on currency hierarchies indicates that currency use and geopolitical power might not be enough to circumvent the effects of subordinated integration (de Paula et al. Citation2017, Kaltenbrunner and Painceira Citation2018). Drawing on scholarship identifying global banks as central to intermediating the rise in offshore dollar denominated credit (Bruno and Shin (Citation2015), McCauley et al (Citation2015), Avdjiev et al. (Citation2017)) this paper asks whether developing economies can use state settlement banks to intermediate their currencies in offshore markets? It argues that at the root of this task is the uncovered liability problem. This refers to the challenge of covering local currency denominated financial liabilities. While there is an emerging literature on the geopolitics and use of the RMB (Knoerich et al. Citation2018), less attention has been given to the role of state settlement banks and offshore markets as a mechanism for mitigating the uncovered liability problem. These banks have sought to fund China’s hard currency needs since the 1950s but have received limited attention in the literature. In addressing this lacuna, this paper examines the institutional and technical features of China’s offshore settlement system, to understand whether it can substitute the intermediary functions of international banks.

The starting point for this paper is that settlement banks and foreign exchange are part of the fundamental but often overlooked components of a countries financial and trade infrastructures (de Goede Citation2020). This approach is consistent with Keynes’s recognition that it is impossible to separate trade issues from those related to the international financial system as evidenced by his support for a commercial union alongside the clearing union (Keynes Citation1941, Kregel Citation2008). Trade cannot exist without international exchange and exchange cannot occur without access to foreign currency (Clausson Citation1944). In the absence of a Keynesian type clearing union, the challenges of either sustaining a net inflow of foreign exchange or becoming an anchor currency are at best non-trivial (e.g. Angrick Citation2018a). At worst, their absence sustains monetary dependence (Koddenbrok and Sylla Citation2019). Critical political economy has debunked many of the monetary policy limitations long associated with being an anchor currency by focusing on how financial innovation and offshore markets served to solidify US structural power (Konings Citation2008, Strange Citation1988, Helleiner Citation1994). These developments can be traced to a failure in the run up to Bretton Woods to develop inclusive multinational institutions that would allay the concerns of non-Western countries including China regarding the exploitative role of foreign banks (Helleiner Citation2019).

Less clear is how, in the absence of these multinational institutions, should developing economies contest this environment and how should the effectiveness of this be assessed? Although political economy has highlighted the impacts of subordination and the currency hierarchy, more work is needed on how economies like China have exploited grey areas in the global financial architecture (McNally and Gruin Citation2017). Focusing on a specific aspect of this question, namely China’s use of Hong Kong’s offshore market, this paper examines the extent to which state settlement banks can increase the offshore intermediation of RMB and mitigate the uncovered liability in much the same way as large international banks historically helped intermediate the use of offshore dollars? China’s efforts to contest financial globalisation offers a fascinating study of this. The geographical distribution of the RMB’s offshore use and settlement has increasingly mirrored other major currencies (Cheung et al. Citation2019, Knoerich et al. Citation2018). The latter were all at various stages characterised by large offshore volumes (Albier Citation1980). Offshore deposits are distinguished by their yield premium, incentivising central banks to hold them offshore (Stigum and Crezcenzi Citation2007), and are specialised in terms of their use and the risk attached to the issuing bank (Aliber Citation1980).

Catalysing the development of an offshore market for an undeliverable currency using state-settlement banks faces several technical and institutional challenges. This paper makes several contributions to understanding these challenges. First, state settlement banks and offshore markets have enabled China exploit loopholes in the global financial architecture (e.g. McNally and Gruin Citation2017). Historically, this has given China an additional policy lever in responding to such geo-political challenges as the US dollar embargos and post-Bretton Woods volatility without compromising on currency delivery. Secondly, while this has allowed China to increase RMB-denominated trade invoicing, limitations on the asset side have seen settlement banks become part of the infrastructure that sustains dollar hegemony. This reinforces the importance of analysing the hardwired nature of financial infrastructures (de Goede Citation2020). Thirdly, in distinguishing between use and deliverability the paper separates offshore non-deliverable deposits from the market-based instruments responsible for creating the bulk of global liquidity (Aldasoro and Ehlers Citation2018). Non-deliverability has made China less vulnerable than other emerging economies to sudden capital flows (e.g. Kaltenbrunner and Painceira Citation2018), but limitations related to geographic reach, governance and offshore credit generation mean it is still subject to the constraints of the currency hierarchy.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section problematises the relationship between the uncovered liability, trade financing and foreign banks and considers how developing economies can substitute the role of large international banks. Section 3 charts the development of China’s use of the offshore market. The penultimate section evaluates the outcomes of state settlement banks in terms of the limitations market segmentation and governance places on offshore liquidity generation. Section 5 concludes.

Contesting financial globalization and the uncovered liability

A longstanding debate in monetary policy concerns the choice between market and state-led interventions as economies move away from balance of payment restrictions (Meade Citation1951, Mundell Citation1963). Monetary history provides little evidence that external imbalances are resolved through market-led adjustments (Thirlwall Citation2004) and critical political economy suggests that the trade-off confronting developing economies is more consistent with what Sun (Citation2015) describes as an impossible duality, where the dominance of the dollar implies limited agency in contesting financial globalisation. This section argues that the roots of limited agency are to be found in the historical relationship between the uncovered liability problem and control over key financial architectures. It is imperative therefore that solutions to the unfunded liability problem go beyond dichotomous conceptions of capital controls and the guiding principle of macroeconomic balance. Within this framework, this section examines the potential of state settlement banks to substitute the missing financial infrastructure prerequisites.

The uncovered liability, foreign banks and currency hierarchies

Underpinning the uncovered liability problem is the control of key financial infrastructures. These infrastructures typically have their roots in colonial histories, are profoundly political and have become hardwired into contemporary financial infrastructures (de Goede Citation2020). Under the colonial system, the subsidiaries of international banks created money by generating loans in local currency. These local currency assets needed to be covered by external assets. The currency of the colonial power represented the safest asset to do this, since in most colonies bank liabilities exceeded assets (Clausson Citation1944). Shortage and currency controls meant that large trading firms kept their books in the currency of the colonial power, increasing its usage. Because colonies ran balance of payments deficits, specie and other forms of money tended to be in short supply (Humpage Citation2015). This increased trade dependency since any disruption of trade flows impacted access to specie and bills of exchange. To circumvent the uncovered liability, transactions were denominated in foreign currency and underwritten by foreign banks (Cluasson Citation1944, Koddenbrock and Sylla (Citation2019)).

While the relationship between large banks, non-financial corporates and trade is now viewed as central to the transmission of US monetary shocks (BIS Citation2014, Passari and Rey Citation2015), the dominance of these banks in underwriting foreign currency denominated letters of credit can be traced to the nineteenth century when a decentralisation of trade finance placed the subsidiaries of large international commercial banks at the centre of trade financing (Accominotti Citation2019). Colonial networks gave these banks a readymade institutional platform to intermediate lead currencies. For example, in British colonies, currency issue was delegated to a currency board operated by expatriate banks (Schenk Citation1997). The West African Currency Union primarily benefited the underwriting activities of overseas French Banks (Koddenbrock and Sylla Citation2019).

This implies that the root cause of the problems facing developing economies was not capital outflow itself, but rather a lack of developed financial and monetary institutions (West Citation1978, Schenk Citation1997). Not only did developing economies lack the mix of public and private institutions that underpin money creation (e.g. Braun Citation2016), but lead currency status could be weaponised to constrain currency access. The UK’s post-war Defence (Finance) Regulations required colonies to implement controls on both the supply of sterling and non-sterling exports, a move that impacted on China’s ability to access hard currency through Hong Kong in the 1950s.Footnote1 These developments serve to illustrate a historical regularity in the money system where the imposition of state controls over money was part of a broader move to bring subsistence activities into a monetary relationship with the capitalist economy (Goodhart Citation1998).

The unequal nature of this relationship has been set out in the currency hierarchy literature by positioning currencies hierarchically according to their degree of liquidity (Prates Citation2017, Kaltenbrunner and Painceira Citation2018). This sets limits on the ability of currencies further down the hierarchy to become internationalised and exploits the well-known constraint faced by developing economies in borrowing in their own currencies (Eichengreen and Hausmann Citation1999). Instead, they denominate their liabilities in more liquid international currencies. To compensate for a lack of liquidity, currencies at the bottom of the hierarchy attempt to achieve a higher expected return and/or lower the obstacles to capital to increase their attractiveness (de Paula et al. Citation2017). Such solutions can become part of a self-reinforcing financialization process that begins with the liberalisation of domestic capital markets and is followed by capital account liberalisation. This encourages domestic and foreign investors to finance themselves in foreign currencies, resulting in an appreciation of the real exchange rate (via asset price inflation) and a deterioration in the current account followed by a domestic shock (such as a domestic banking failure) (Bonizzi Citation2013).

The solutions available to developing economies are further constrained by the way that the financial and corporate transmission mechanisms for US monetary policy shocks sustain the currency hierarchy (e.g. Rey Citation2013). Koddenbrock and Sylla (Citation2019) argue that the experiences of the global south radicalise this dilemma in the sense that they cannot influence the global financial cycle, capital flows or the prices of lead currencies. This has been amplified by the way structural adjustment programmes focus on industrialisation and domestic demand management, with limited attention to reforming the international financial architecture (Kregel Citation2008). This meant that while liberalisation liberated an in-built tendency in the socialist economy to debt accumulation, privatisation offered firms the autonomy to engage in international relations and accumulate foreign currency denominated debt, with which the ‘semi-bureaucratic semi-efficient’ reform economy struggles to deal with (Kornai Citation1992, p. 554).

Through what devices?

Can developing economies circumvent the hardwired nature of financial architectures? In exploring how late developing economies overcame the obstacles for mobilising finance Gerschenkron (Citation1962, p. 358) asked: ‘through what devices did backward countries substitute for the missing pre-requisites’. At the extreme, an absence of trust and commercial honesty made it impossible to create a system of long-term bank credit without government intervention (Gerschenkron Citation1962, p. 47). Trust is central to the legitimacy of the public and private institutions that underpin credit and often only becomes apparent when it evaporates (Braun Citation2016). Trust is also related to money’s credit generating ability (Borio Citation2018). Since credit is created through bank lending, the credit generating ability of a currency and the legitimacy of the issuing bank are crucial to the state’s ability to substitute the missing prerequisites.

China has responded to this challenge by emphasising control over key financial infrastructures such as exchanges as central to making finance serve the domestic economy (Petry Citation2020). China has also promoted bilateral currency swap agreements as an active form of statecraft, though as McDowell (Citation2019) argues the success of the RMBs future as a trade settlement currency ultimately requires an international expansion of clearing agreements and major banks. Consistent with Gershnekron’s (Citation1962) thesis, Töpfer and Hall (Citation2017) show that the role of the state is central to catalysing the development of offshore markets, even though it cannot necessarily control offshore markets that fall outside of its jurisdiction. This points to the historical advantage of Hong Kong since it offers both the ability to control and catalyse the development of offshore markets.

If offshore markets offer a mechanism for addressing the unfunded liability, then the challenge is one of identifying the political and economic variations in how the process of capital account opening can be managed (CitationMcNally and Gruin2017). The early Eurodollar market offers some lessons on how a segmented offshore market can operate under capital controls. Segmentation facilitates the separation of currency and country risks and was initially a feature of the offshore Eurodollar market under capital controls (McCauley Citation2005). This meant that funds flowing into and out of the Eurodollar market had no impact on the UK’s foreign reserves (Stigum and Crezcenzi Citation2007). Capital controls also imply a distinction between use and delivery. Along with trust and credit generation, use is intrinsic to an international currency. This implies use as a medium of account and a unit of exchange (Cohen Citation1971). Less clear is the degree to which an offshore currency must be deliverable. Non-deliverability means that offshore markets do not meet the condition of full arbitrage (Aliber Citation1980).

The concept of non-delivery and the extent to which state intervention is required to underwrite trust and credit generation offers a benchmark to differentiate between currencies that are fully deliverable and have no restrictions on their exchange (Noyer Citation2015), and those that have current account convertibility and can be used to denominate trade and debt but are not fully deliverable. In practice, this means that investors can easily switch between denomination in RMB and the US dollar offshore but cannot freely remit the proceeds of these transactions onshore. The ability to denominate trade in domestic currency therefore provides the state with a mechanism for substituting the missing prerequisites necessary for managing financial integration. This is particularly suited to standard trade finance instruments, which tend to be opaque and are characterised by large information asymmetries (BIS Citation2014).

Offshoring the uncovered liability and the parallel market

To assess the outcome of China’s efforts to catalyse the development of an offshore market and substitute the trade invoicing function of international banks, maps the balance sheet counterparts for the onshore and offshore markets. This accounts for the requirement of segmentation as apart of China’s capital control regime and allows for the identification of the potential coordination problems that Kornai (Citation1992) viewed as synonymous with the parallel existence of internal onshore semi-marketized prices with external offshore market prices.

Table 1. Simplified Onshore and Offshore Financial System Assets and Liabilities.

Ideally, to mitigate the unfunded liability problem, state-settlement banks need to achieve a diversified holding of offshore RMB assets and liabilities among non-Chinese investors. In the absence of an internationally used currency, to fund domestic financial liabilities in the onshore market not funded by domestic assets, the currency hierarchy indicates that countries further down the hierarchy need to maintain strong currencies to attract inward financial flows. An offshore market offers a way to circumvent this by maintaining a distinction between onshore and offshore money by issuing specialised financial assets (Aliber Citation1980). This is because the onshore balance sheet counterpart of an offshore RMB deposit is an increase in the net foreign currency assets of the domestic financial system (McCauley Citation2013; ). Ideally, as McCauley (Citation2013) points out, for China’s offshore market the optimal outcome would see offshore Chinese settlement banks generate RMB denominated credit for non-Chinese borrowers and non-Chinese investors holding the corresponding RMB liabilities.

If non-Chinese investors are unwilling to hold RMB assets offshore, this creates an uncovered liability. To mitigate the effects of this and maintain segmentation between the onshore and offshore market, China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) must approve the remittance of any proceeds from the sale of offshore assets since their repatriation would expand the domestic money base (). The repatriation of proceeds from the issue of offshore ‘Dim Sum’ RMB denominated bonds by domestic non-financials to investors in Hong Kong requires such scrutiny. Once a Dim Sum bond is issued to an investor in Hong Kong, the issuing offshore entity lends money via a loan to an onshore bank. This is repaid at the end of the bond tenor. This arrangement does not pose a challenge to the segmentation of the offshore and onshore markets since a unique feature of China’s offshore bond market is that most RMB-denominated bonds are held by domestic investors, issued by state-owned enterprises, and underwritten by state settlement banks (Upper and Valli Citation2016, p. 73). The latter play a crucial role in catalysing the offshore market’s development through the complementary use of price and non-price tools to resolve the coordination problems associated with parallel markets (Kornai Citation1992, p. 159).

The link between currency and trade settlement also implies that increased use of RMB in cross-border trade settlement can increase coordination problems for the non-deliverable currency since a strong currency creates an unbalanced demand where onshore importers have a greater incentive to settle their bills in RMB. Conversely, domestic exporters have an incentive to invoice in US dollars. This results in an inflow of corporate RMB deposits to the offshore market and swells the liabilities of the settlement bank (). Onshore firms also have an incentive to circumvent controls and borrow in US dollars. In the absence of the market-based hedging products, a feature of deliverable currencies, there is little incentive for foreign investors to hold RMB liabilities since an appreciating currency leaves foreign holders of RMB liabilities exposed, lessening the incentives for non-resident holdings on the offshore asset side ().

The potential funding imbalance in provides a useful metric to benchmark the outcome of the offshore market. It indicates that increasing the holding of offshore RMB denominated assets by non-residents is key to mitigating the unfunded liability. The remainder of this paper addresses this by examining the development and evolution of China’s offshore market from a means of circumventing US monetary controls to promoting greater international use of RMB in the post Bretton Woods environment.

Internationalising a non-deliverable currency using state settlement banks

As one of the few globally significant economies where a large part of the financial system remains subject to state control, the history of the PRC’s efforts to contest financial globalisation using a non-deliverable currency offers a unique insight into efforts to mitigate the unfunded liability problem. The origins of non-delivery and the preference for capital controls can be traced to Republican-era concerns over the profits made by foreign banks (Helleiner Citation2019). While these concerns remain, this section shows how volatilities in the international financial system, loopholes in its architecture and the decline of international currencies provided China with an opportunity to use state settlement banks as an interface for contesting financial integration. It also meant that China’s desire to use the RMB to counteract the volatility of the capitalist system and promote the RMB for trade settlement is intertwined with key events in the history of the international monetary system.Footnote2 This section documents how these events provide the basis for state control over the settlement infrastructure and allowed China to exploit grey areas in the global financial architecture.

Offshore currency markets under central planning

The hardwired and political nature of the link between colonial-era infrastructures and the challenge in increasing the RMB’s international use can be traced to the period 1949–78, where the RMB’s prospects alternated between the constraints imposed by the US dollar’s increasing power and the mismatch between China’s domestic and export economies. Export volumes were small, and China broadly followed an import substitution policy (Reardon Citation2002). China relied on an overvalued currency, but any advantage conferred by this was outweighed by an embargo on US dollar transactions following the PRCs intervention in the Korean War and the UK’s Defence (Finance) Regulations. This meant that transactions in the two major international currencies of the period were for the most part off-limits.

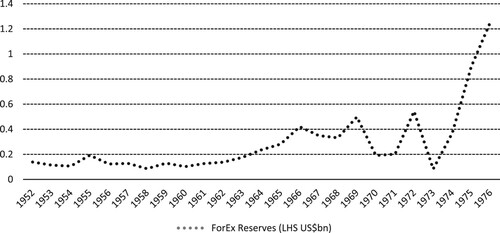

A geographically convenient loophole was offered by Hong Kong’s free currency market. This was for the most part beyond the reach of US legal institutions (Goodstadt Citation2007). Although part of the sterling area, Hong Kong depended on Mainland China for food imports. These hard currency earnings enabled the PRC to settle its growing trade with non-communist countries and accumulate foreign exchange reserves (). The settlement institution at the centre of this was the Bank of China in Hong Kong. Reflecting China’s increasing participation in Hong Kong’s currency market, its deposits increased from HK$124 million in 1964 to HK$290 million in 1966.Footnote3 As shows, this allowed the PRC to increase its financial integration and exploit loopholes in the international financial architecture without liberalising its capital account. The Bank of China maintained branches in other parts of the sterling area including Singapore, Calcutta and Karachi. Although the volume of sterling purchased in these markets was smaller than in Hong Kong, archived documents indicate that by the 1960s, the Bank’s foreign currency activities in these territories along with mutually beneficial cooperation with note-issuing international banks in the sterling area including HSBC and Standard Bank played an important role in China’s foreign exchange funding.Footnote4

Figure 1. China ForEx Reserves (US$ Billion, 1952–1976). Source: Data on Foreign Exchange (ForEx) Reserves are from Xin Zhongguo Wushi Nian Tongji Ziliao Huibian (Citation1999).

In this way, China’s financial system was both externally flexible and internally inflexible. External flexibility implied market agency in currency settlement. The November 1967 devaluation of Sterling illustrated this. Rather than absorb the foreign exchange losses from sterling’s devaluation, as would be expected under an inelastic export structure, the Bank of China re-valued the RMB against the Hong Kong dollar.Footnote5 This ensured continued growth in China’s trade and foreign exchange reserves (), providing a rare exception to the lack of offshore agency that characterised the monetary policies of developing economies. However, this agency was short lived and a run on China’s foreign exchange reserves during 1970–71 and again in 1973 illustrated the underlying vulnerability of the PRC’s position (). Moreover, sterling’s devaluation and subsequent decline as an international currency indicated the stark choice China would have to make.

Promoting a non-deliverable currency after sterling’s devaluation

The run on China’s Forex reserves and the subsequent collapse of the Bretton Woods Gold Standard reinforced the importance of access to foreign exchange and a strong independent currency. It also signalled the beginning of a more activist approach to monetary policy. In 1968 China began to promote the RMB as currency for price quotation, settlement and investment.Footnote6 This highlighted the non-deliverability constraint as settling on investments in RMB was hindered by a ban on currency export. The solution sought to exploit a loophole which meant that RMB deposits could be denominated in non-deliverable RMB. This created a book entry in RMB at the Bank of China, which entitled the depositor to receive a sum in Hong Kong dollars on maturity. This was calculated at the expiry of the deposit’s tenor at the prevailing rate of exchange between the RMB and the Hong Kong dollar. This model of settlement was later to form the template for the offshore market after 2003.

These efforts increased in response to the ending of the Breton Woods Gold Standard in 1971 and the running down of China’s foreign exchange reserves (). In 1972 a United Nations small group was formed within the Bank of China’s Institute of International Finance (Jacobson and Oskenberg Citation1990). The group’s meetings were attended by officials from the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Finance as well as the State Statistical Bureau. The group closely followed developments in the World Bank and IMF. They also faced political hostility. Although the intensity of the Cultural Revolution had waned by the early 1970s, the future direction of China’s economic relations was far from certain. Significantly this approach and the Bank of China’s operations in Hong Kong received political support from the then-ailing Premier Zhou Enlai (Mingpao Yuekan April 10, 1989).

Efforts to promote the international use of the RMB during the 1970s sought to exploit three features of the planned economy, namely price stability, an overvalued currency and a central unified system of currency issuance.Footnote7 Between 1971 and 1979 as part of this policy, the PRC re-valued the RMB steadily upwards from 2.46/US$ to 1.49/US$ (Lardy Citation1992, p. 66). In Hong Kong, the Bank of China reinforced the direction of this policy by going against the trend of local rate reductions and increasing its RMB deposit rates to encourage Hong Kong residents to open RMB denominated accounts.Footnote8

The direction of these currency activities reflected a broader consensus among development economists that late industrialising economies could not modernise and fund current account deficits without access to foreign exchange (Fischer Citation2018). Although the proceeds of these initiatives were small and allowed the PRC’s to accumulate foreign currency reserves (), they depended on a strong currency. They were also accompanied by greater use of dollar denominated foreign trade loans, trade credits and gold reserves (Reardon Citation2002, p. 174–75). For the PRC this reflected a pragmatic recognition that the currency of reference was to be the US dollar. By 1975 trade deals were mostly denominated in US dollars (Jao Citation1983). The mix of non-deliverability and dollar denomination allowed China to avoid the austerity/financial liberalisation dilemma faced by many developing economies (e.g. Fischer Citation2018; Kaltenbrunner and Painceira Citation2018) but also illustrated a more fundamental point that large international banks and the dollar were already central to financial intermediation.

Control, promotion and the postponement of currency deliverability

The post-1978 reduction in antagonism towards foreign investment provided a clearer direction over how China intended to address its shortage of foreign capital and had significant implications for the RMB’s prospects as an international currency. By 1979 it was clear that the scale of finance necessary for China’s industrialisation could not be funded by the small-scale international use of a non-deliverable currency. The direction of future policy was set out in 1980 under the Provisional Regulations for Exchange Control, which emphasised the spirit of control and promotion.Footnote9 Promotion allowed localities to earn foreign exchange by decentralising control over international trade from the centre (Solinger Citation1993). Control meant the retention of centralised rules over areas such as labour movement, wage levels, the interest rate and the amount of foreign exchange that localities would be allowed to retain. External flexibility towards FDI meant that unlike the 1970s foreign exchange was no longer scarce and China began to run a financial account surplus.

Control was also motivated by China’s wariness of the post-Bretton Woods monetary older. In the early 1980s, China criticised the unfavourable nature of the flexible exchange rate system for emerging economies alongside the dominant but volatile position of the US dollar as the main reserve currency.Footnote10 This remained a consistent theme of China’s critique of the US dollar’s role in the global financial hierarchy. Following the Global Financial Crisis, China’s President argued that the international monetary system was a product of the past, reminding the US that this meant that it had a duty to keep dollar liquidity at reasonable levels.Footnote11

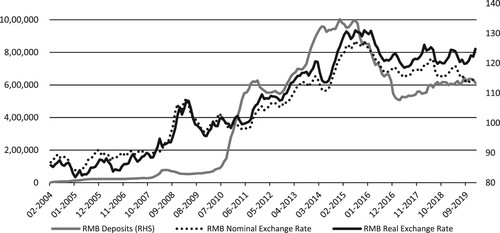

At the same time China intensified its efforts to promote offshore deposits and trade invoicing in non-deliverable RMB. A new policy of promotion in 2003 saw the Bank of China in Hong Kong named as the authorised offshore clearing bank for RMB. The pre-existing offshore infrastructure provided a ready-made institutional interface for a controlled promotion and unwinding of offshore liquidity, with Chinese officials arguing that it allowed an effective management of the risks associated with cross-border trade and currency internationalisation (PBoC Citation2011, p. 14). As a clearing bank, the Bank of China in Hong Kong was linked to the National Advanced Payments System (CNAPS) of the PBoC and had access to the Shanghai Exchange. This was supported via a backstop liquidity facility provided by a swap facility operated by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA). Initially, 37 approved financial institutions in Hong Kong were permitted to offer RMB savings products (). By 2014 the number of approved institutions peaked at 149. Transactions in the offshore market were settled on a real-time basis using the onshore rate. The Bank of China’s global network also meant that other zones, which initially did not have their own clearing bank, such as London, could use Hong Kong’s payments system. Later China Construction Bank was appointed the settlement bank for London, while ICBC was appointed as the settlement bank for Singapore.

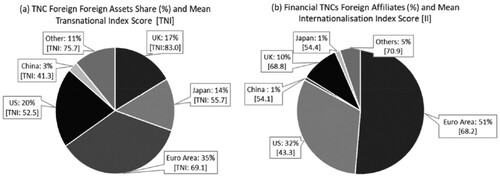

Table 2: Renminbi Deposits, Hong Kong, Selected Indicators (2004–2019).

These state settlement banks benefit from substantial global networks and are comparable in asset size to the world’s largest banks (). However, their initial success in growing offshore deposits in the early 2000s appears to have abruptly slowed after 2014 (). One explanation is that the size of China’s settlement banks mostly relates to their domestic operations and what they lack is global reach (). The numbers of their international affiliates and the geographical scope of their operations rank much lower than other transnational financial institutions (). The comparatively limited geographic reach provides a clear institutional level distinction between China’s settlement system and the global banks that facilitated the dollar’s rise.

Table 3. Financial TNCs by Assets and Geographical Spread.

To the market and back

A second explanation is that although the direction of monetary reforms was increasingly market-oriented, their technical operation fell under state-coordination. This meant that reforms such as the launch of a Cross-border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) in October 2015, designed to make it easier to by-pass offshore settlement, stopped short of currency deliverability. Similarly, a surprise devaluation of the RMB in 2015, saw China revert to the planned economy by constraining the ability of Chinese corporations to fund their foreign currency borrowings. This restricted the ability of offshore banks to generate RMB assets. Non-bank RMB bond issuance in Hong Kong fell from RMB 21.6 billion in the first quarter of 2015 to RMB4.3bn for the same period in 2016, while RMB denominated bank lending declined by 5.3 percent during the same period (Government of Hong Kong SAR Citation2016).

The move coincided with a decline in offshore deposits and a reduction in the stock of international claims on China’s banking system ( and 3). However, the ratio of offshore RMB denominated trade settlement to deposits continued to increase (), illustrating a key difference between trade settlement, which is not dependent on currency deliverability, and other financial assets. The devaluation showed that the growth in offshore deposits was not immune from the pressure to maintain a strong currency. shows that from late 2010 onwards, China’s real exchange rate exceeded its nominal rate, indicating a loss in China’s long-held price competitiveness. From the mid-2000s wage growth started to outpace productivity growth.Footnote12 From this perspective, devaluations in 2015 and 2016 reflected the extent to which market signals were affecting monetary policy and the necessary state interventions needed to compensate for the lack of non-Chinese participants in the offshore market once Chinese corporations were no longer funding their liabilities offshore ().

Figure 2. Exchange Rate Indices (RHS) and Offshore Deposits (LHS), 2004–2020. Source: BIS Exchange Rate Database; Hong Kong Monetary Authority.

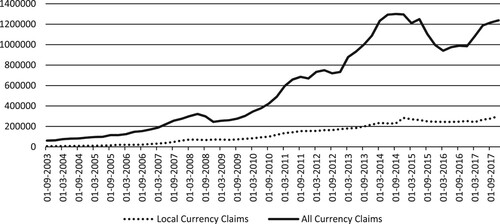

Figure 3. China All and Local Currency Claims of BIS Reporting Banks (US$bn). Notes: International bank claims are the sum of banks’ cross-border claims and their local claims denominated in foreign currencies. Local currency claims include the claims of branches or subsidiaries located in the reporting country whose activities are not consolidated by a controlling parent institution in another reporting country. This mainly comprises banking offices with a non-bank controlling parent institution. BIS, June 2016: 5–6.

Offshoring the liability problem: reviewing the technical and institutional limitations of the offshore market

The evolution of the offshore market from a mechanism to circumvent the US dollar embargo to one designed to increase the use of a non-deliverable currency shows that while state settlement banks can substitute some of the functions of large international banks, especially in more opaque areas such as trade settlement, they lack the supporting financial and non-financial institutions necessary for achieving a sufficient level of international currency use. This sets a clear distinction between China and the evolution of other offshore markets such as the Eurodollar market. For the latter, the development of institutional linkages and the willingness of overseas investors to hold dollars meant that such limitations were less of a concern (Eichengreen Citation2011, Konings Citation2008). To understand why China’s use of the offshore market has diverged from this outcome, this section discusses the technical and institutional limitations underpinning the way state settlement banks intermediate offshore RMB and why this has swelled the liability side with few opportunities for expanding the asset side.

State settlement banks and offshore liquidity limits

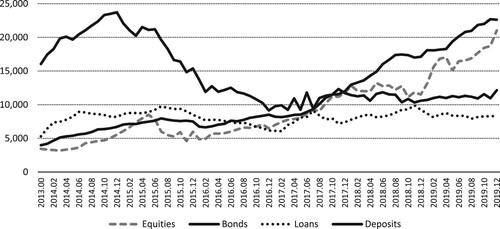

Different from the early growth of the offshore market for US dollars (e.g. McCauley Citation2005), segmentation has placed an inbuilt limit on the ability of China’s settlement banks to generate offshore liquidity. Consequently, the growth of the offshore market has had a limited effect on diversifying the composition of financial assets held by overseas residents. The analysis in this paper and more recent data () shows that non-deliverable deposits have long been the main RMB asset held overseas and that the quantity of other instruments such as equities and bonds tended to be small. The recent liberalisation of quotas for foreign participation in China’s onshore bond and equity markets and inclusion in the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index has increased foreign holdings of RMB bonds. This asset switch reflects both the desire of China’s foreign exchange regulator to optimise the structure of China’s debt profile and global trends (SAFE Citation2019, Aldasoro and Ehlers Citation2018). It is significant that this has come from liberalisation of onshore quotas rather than the offshore market. The former is more consistent with the liberalisation agenda of organisations such as the IMF (e.g. Schipke et al. Citation2019) and potentially opens China to the vulnerabilities of market finance, capital outflow and subordinated financialization (e.g. Gabor Citation2018, Kaltenbrunner and Painceira Citation2018).

Figure 4. Domestic RMB Financial Assets held by Overseas Entities (100 mill Yuan). Source: Peoples Bank of China, Money & Banking Statistics (货币统计概览) See: http://www.pbc.gov.cn/diaochatongjisi.

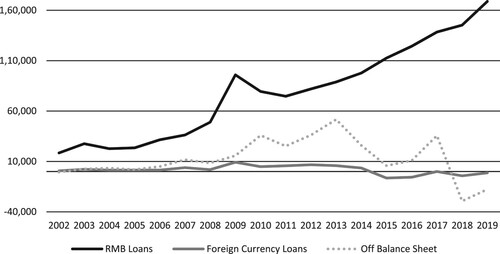

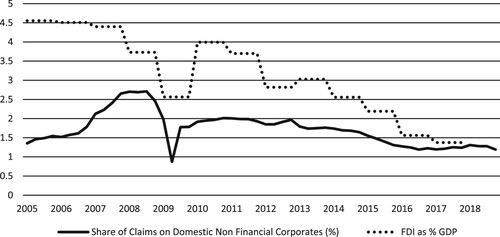

Does this mean that China’s efforts to achieve a controlled internationalisation via offshore markets has succumbed to the growing calls for capital account liberalisation? The answer to this is not clear cut. It is true that onshore bonds provide a vehicle for capital outflow and increased foreign holdings followed by currency and yield volatility are symptomatic of a trend towards financialization in developing economies (Bonizzi Citation2013). Yet, in contrast to other reform economies, the rapid growth in China’s debt after 2008 has been characterised by a paying down of foreign currency loans (). Since the early 2000s, China’s international debt as a percentage of GDP declined and about one-third of foreign debt is denominated in RMB (SAFE Citation2019). Addressing one of the major historical concerns of non-Western economies in the establishment of Bretton Woods (Helleiner Citation2019), China has also succeeded in limiting the share of claims of foreign-owned banks and it has reduced its dependence on FDI in capital formation ().

Figure 5. Flows RMB Loans, Foreign Currency Loans and Off-Balance Sheet (RMB, 100mill). Source: Peoples Bank of China, Aggregate Financing to the Real Economy (社会融资规模) http://www.pbc.gov.cn/diaochatongjisi.

Figure 6. Share of Foreign Banks Claims on NFCs (%) & FDI as a % GDP (2005–18). Source: The share of Foreign Claims on Non-Financial Corporate is calculated using quarterly data from Peoples Bank of China Annual Reports (2005–2017); FDI as a % of GDP calculated using quarterly data from the State Administration of Foreign Exchange http://www.safe.gov.cn/en/DataandStatistics/.

State-owned settlement banks have played a role in this by enabling China to keep these liabilities offshore and avoid a mass outflow of capital. The technical functioning of this role is illustrated in data from the Upper and Valli (Citation2016), which shows that the outstanding stock of international claims on banks in China decreased from US$648 billion at the end of September 2014 to $374 billion by the end of December 2015. McCauley and Shu (Citation2016) argue that while the decline in claims reflected Chinese firms paying off their dollar-denominated debt (as opposed to mass sell-off of mainland assets), concealed in the decline in claims is the shrinking of offshore liabilities. The shrinking is largely accounted for by the activities of China’s offshore settlement banks. This is because the stock of international claims () includes China’s state-owned settlement banks in Hong Kong. Chinese corporations had started to borrow internationally in US dollars on the back of an appreciating Yuan in 2012–13. This coincided with an increase in the international component of China’s debt. This fell in 2015 as domestic corporations rapidly reduced their foreign borrowing. The decline in claims shown in involved international banks in offshore settlement hubs such as Hong Kong, Taipei and Singapore drawing down their deposits with these settlement banks.

While the growth of international claims since the 2000s represented an increase in foreign claims on China (), the role of state settlement banks meant that its financial effects were contained offshore. A paradoxical effect of these activities is that China’s settlement banks have become big suppliers of dollar liquidity, effectively sustaining the dollar’s dominance since there are few reasons for foreign investors to hold RMB assets (). The decline in the quantity of RMB-denominated loans held by overseas entities after 2015 () highlighted how the growth of the offshore market was ultimately constrained by the unwillingness of foreigners to hold RMB assets. Given the declining role of FDI and the low presence of foreign banks (), this means that China continues to face the question of how to fund the portion of financial liabilities not funded by domestic assets.

Settlement banks, geographical reach and governance

The historical lessons from the role of US banks in disseminating the widespread use of the dollar (e.g. Bruno and Shin (Citation2015), Avdjiev et al. (Citation2017)) and the relative success of China in increasing offshore RMB trade invoicing offer tentative support for the view that developing economies should strengthen the global presence of their financial institutions as a means of addressing the uncovered liability problem. This would represent a departure from the internal focus of structural adjustment programmes (e.g. Kregel Citation2008), but is by no means a trivial task. The areas where state settlement banks have been successful do not require deliverability, reinforcing the point that for many cross-border payments, money deposits do not need to enter or leave a county, but simply involve a change in ownership (Borio et al. Citation2015). But the process does require a settlement bank and the historical evidence suggests that the geographic reach and governance of the settlement bank are crucial in this regard.

Why then were these banks unable to expand the offshore holdings of RMB deposits at a faster rate? One explanation highlighted in this analysis is geographic reach. RMB settlement is concentrated in such financial centres as Hong Kong, London and Singapore, cities where Chinese state banks have long a presence and benefit from highly liquid markets. This reinforces the view that geographical scope is a function of specific geo-political and financial centre locational factors (Töpfer and Hall Citation2017). While some progress has been made in establishing settlement centres beyond non-allied locations using a negotiated approach (Knoerich et al. Citation2018), geographical scope continues to distinguish China from other creditor nations such as Japan. Although the Yen is not an international currency in the same way as the US dollar, it has gained considerable regional use by non-residents (Angrick Citation2018b). illustrates how geographic scope extends beyond financial institutions. Japanese transnational corporations (TNCs) account for 14 percent of the overseas assets for the top 100 global TNCs (). Chinese non-financial TNCs account for just 3 percent and have a low internationalisation score ().

Figure 7. Non-Financial and Financial TNCs International Presence (2017). Notes: The TI Score for Non-Financial TNCs is calculated as the average of foreign assets to total assets, foreign sales to total sales and foreign employment to total employment and is averaged for each country/currency area. Financial TNC affiliates refer to the majority owned foreign affiliates of the top 50 Financial TNCs by foreign assets. The Internationalisation Index (II) score is calculated as the number of foreign affiliates divided by the number of all affiliates and is averaged for each country/currency area. Source: UNCTAD World Investment Report 2018.

This reinforces Keynes’s argument that it is not enough to reform the financial architecture of the international settlement system, but such reforms must also extend to trade. This lends coherence to some of China’s broader geo-political ambitions. Rising south-south trade along with the use of sanctions via the global payments system has increased interest among emerging economies for a stable alternative to the Dollar for invoicing trade (Nölke et al. Citation2015, de Goede Citation2020). Similarly, increasing the participation of Chinese corporations in projects related to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) offers a way of increasing currency use that does not require compromise on currency delivery. The BRI also creates the potential for a more internationalised Chinese monetary policy (McNally and Gruin Citation2017). While establishing bilateral swap lines with BRI countries has been critiqued as ineffective financial statecraft (McDowell Citation2019), using state settlement banks to coordinate offshore intermediation could offer a practical channel for diversifying the composition of RMB financial assets held by non-residents. However, the findings of this and other studies suggest caution on the role of state coordination. Ultimately state settlement banks can enable offshore expansion, but state control and segmentation act as a brake on private demand for RMB (Töpfer and Hall Citation2017).

One reason for this relates to governance. Money creation is not independent of governance (Goodhart Citation1998). Many newly independent ex-colonies struggled to replace currency boards with more flexible and independent monetary institutions, often ending up with currency boards all but in name (Schenk Citation1997). These failures were often attributed to domestic productivity differences in the advanced and subsistence sectors (Lewis Citation1954), but as this paper has shown, they are also rooted in the global financial architecture. China’s retreat from central planning has gradually eroded the unified system of currency issuance that existed prior to 1978 but has yet to replace this with a system that guarantees greater monetary independence and flexibility. Incomplete financial reforms mean that when liquidity shocks occur, China’s high and low growth regions are often adversely affected, while partially reformed labour markets imply that the labour supply cannot freely adjust.Footnote13

In this environment is also not clear that state-owned settlement banks can implement the policy adjustments required to achieve the type of monetary balance that would eliminate the uncovered liability problem. While Kornai (Citation1992, p. 344) argued that state-owned foreign exchange banks were ill-suited to any fine-tuning of the foreign exchange system, China’s use of state settlement banks indicates that it places a priority on owning the financial infrastructure as a means of contesting financial globalisation. This highlights crucial differences between the evolution of China’s offshore markets, and the speed at which new institutional linkages dramatically enhanced the capacity of the US to increase its power in international finance (Konings Citation2008).

Conclusion

Settlement banks play a crucial role in intermediating the international use of a currency. History highlights important parallels between the financial institutions used by China to create a pool of offshore liquidity and those used by other major currencies. China’s approach shares a historical regularity with the way in which dollar liquidity is extended by large global banks (e.g. Bruno and Shin Citation2015). Yet, one of the paradoxical features of the offshore market is that state-owned banks have become significant sources of dollar liquidity (). This indicates that although China has not yet reengineered the global financial system, its integration with this system is altering the institutional configuration of the international financial system (McNally and Gruin Citation2017). The paradox this presents is captured in Kornai’s (Citation1992) conception of the parallel market, in particular the challenge the state faces in coordinating the foreign currency activities of domestic firms, while at the same time promoting the holding of RMB denominated assets by non-residents. This has meant that the outcome of the offshore market is more consistent with a narrow institutional innovation designed to lower the costs of trade (e.g. Gerschenkron Citation1962) rather than a broader financial market where investors fund their international borrowing in RMB (Kaltenbrunner Citation2010).

The paper’s approach reinforces the importance of analysing the technical and institutional specificities underlying currency settlement (Konings Citation2008). Indeed, the centrality of the state in underwriting the settlement system reflects the broader point set out by Eichengreen and Kawai (Citation2014) that neither Britain in the nineteenth century, nor the United States in the twentieth century, nor even Japan in the 1980s, had the same level of state-driven currency intervention as the PRC. While China’s banks now rank among the largest suppliers of dollar liquidity, this paper reinforces the danger of drawing inferences regarding capital flows from the current account balance (e.g. Borio et al. Citation2015) without an analysis of financial institutions that facilitate the internationalisation of a currency. The involvement of state settlement banks does not mean that the internationalisation process is not subject to market forces. Instead, it cautions that the level of marketisation may seem greater than reality, a feature that has long been synonymous with the financial systems of reform economies (Kornai Citation1992, p. 544). Offshoring deliverability has in this sense allowed China to circumvent some, but not all, of the restrictions that post-Keynesian scholars have associated with the currency hierarchy (e.g. de Paula et al Citation2017).

The analysis presents some policy implications. Consistent with a growing literature on the international monetary architecture (e.g. Rey Citation2013, Sun Citation2015), there is no guarantee that monetary independence follows from greater international use. Large banks have a crucial role in promoting international currency use and are often the missing piece in the financial architecture of developing economies. Banking reform is therefore crucial, but so too is the creation of a wider pool of financial instruments and international corporates. Keynes point that reforming the financial architecture cannot only involve currencies but also trade is as relevant today for China as it was historically. That is not to say that the offshore market cannot operate with a high degree of efficiency and adaptability, in parallel with the less developed domestic market. This appears to be a unique institutional feature of using overseas state settlement banks in that it allows the banking system to be in parallel externally adaptable and internally inflexible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Damian Tobin

Dr. Damian Tobin is lecturer in International Business at Cork University Business School. His current research focuses on the political economy and history of currencies, state-owned banks and financial architectures. He has published on such topics as financial inclusion, the history of China's national oil companies and state-owned banks.

Notes

1 The operation of sterling area controls was set out by the Secretary of State for the Colonies during the early 1950s: CR19-2321-52 Import Licensing Policy for Dollar Imports (Hong Kong Records Service (HKRS hereafter) 163-9-98)

2 New China News Agency (NCNA hereafter) 21st September 1974

3 Data derived from HKRS163-1-3273 ‘Banking Statistics Various’

4 Record No. CO 1030/609: ‘Singapore. Relations with China.’ Public Records Office, Singapore

5 ‘As Peking Saw It’ Far Eastern Economic Review, 11th April 1968

6 ‘PRC remains free of inflation, currency stable’ NCNA, Peking 21st September 1974

7 ‘PRC remains free of inflation, currency stable’ NCNA 21st September 1974

8 In October 1974 the Bank of China raised its six month deposit rate to 7 percent compared to the previous rate of 4.5 percent. File: HKRS 70-6-91 Banks and Banking

9 ‘Strengthen Foreign Exchange Control to Promote the Four Modernisations’ Renmin Ribao [Peoples Daily], Editorial, 30th December 1980.

10 See China Advocates International Currency Reform, Wen Wei Po, Hong Kong 26th March 1981, Published in Daily Report. People's Republic of China, FBIS-CHI-81-058

11 ‘President Hu: U.S. monetary policy has a major impact on global liquidity, capital flows’ Peoples Daily, 17th January 2011

12 Between 2004 and 2008, average manufacturing wages grew 14.1% while labour productivity grew 10.7%. See China Monetary Policy Report (2010: 44).

13 See ‘Banks Halt Lending amid Tighter Liquidity’ Caixin June 26th, 2013

References

- Accominotti, O., 2019. International banking and transmission of the 1931 financial crisis. Economic history review, 72, 260–285.

- Aldasoro, I., and Ehlers, T. 2018. Global liquidity: changing instrument and currency patterns. BIS quarterly review, September 2018.

- Aliber, R., 1980. The integration of the offshore and domestic banking system. Journal of monetary economics, 6 (4), 509–526.

- Angrick, S., 2018a. Global liquidity and monetary policy autonomy: an examination of open-economy policy constraints. Cambridge journal of economics, 42 (1), 117–135.

- Angrick, S., 2018b. Structural conditions for currency internationalization: international finance and the survival constraint. Review of international political economy, 25 (5), 699–725.

- Avdjiev, S., et al. 2017. The shifting drivers of global liquidity. BIS Working Papers, no 644 (June).

- BIS. 2014. Trade finance: developments and issues. CGFS Papers No 50.

- Bonizzi, B., 2013. Financialization in developing and emerging countries. International journal of political economy, 42, 83–107.

- Borio, C. 2018. On money, debt, trust and central banking. Cato Institute, 36th Annual Monetary Conference, 15 November 2018, Washington DC.

- Borio, C., and Disyatat, P. 2015. Capital flows and the current account: Taking financing (more) seriously. BIS Working Papers No 525.

- Braun, B., 2016. Speaking to the people? money, trust, and central bank legitimacy in the age of quantitative easing. Review of international political economy, 23 (6), 1064–1092.

- Bruno, V., and Shin, H., 2015. Cross-border banking and global liquidity. Review of economic studies, 82 (2), 535-564.

- Cheung, Y.W., McCauley, R.N., and Shu, C. 2019. Geographic spread of currency trading: the renminbi and other EM currencies. BIS Working Papers No 806.

- Clauson, G., 1944. The British colonial currency system. The economic journal, 54 (213), 1–25.

- Cohen, B.J., 1971. The future of sterling as an international currency. London: Macmillan.

- Cohen, B.J., 2012. The Yuan tomorrow? Evaluating China’s currency internationalization strategy. New political economy, 17 (3), 361–371.

- de Goede, M., 2020. Finance/security infrastructures. Review of international political economy. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1830832.

- De Paula, L.F., Fritz, B., and Prates, D.M., 2017. Keynes at the periphery: currency hierarchy and challenges for economic policy in emerging economies. Journal of post keynesian economics, 40 (2), 183–202.

- Eichengreen, B., and Hausmann, R., 1999. Exchange rates and financial fragility. Proceedings - Economic Policy Symposium - Jackson Hole, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 329–368.

- Eichengreen, B., 2011. Exorbitant privilege: the rise and fall of the dollar. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Eichengreen, B., and Kawai, M. 2014. Issues for renminbi internationalization: an overview. ADBI Working Paper Number 454.

- Fischer, A.M., 2018. Debt and development in historical perspective. World economy, 41 (12), 1–20.

- Gabor, D., 2018. Goodbye (Chinese) shadow banking, hello market-based finance. Development and change, 49, 394–419. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12387.

- Gerschenkron, A., 1962. Economic backwardness in historical perspective: a book of essays. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Goodhart, C., 1998. The two concepts of money: implications for the analysis of optimal currency areas. European journal of political economy, 14 (3), 407–432.

- Goodstadt, L.F., 2007. Profits, politics and panics: Hong Kong’s banks and the making of an economic miracle, 1935–1985. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Government of Hong Kong SAR, 2016. Frist Quarter Economic Report, 2016. Financial Secretary's Office, Government of Hong Kong SAR.

- Helleiner, E., 1994. States and the re-emergence of global finance: from Bretton Woods to the 1990s. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Helleiner, E., 2019. Multilateral development finance in non-western thought: from before bretton woods to beyond. Development and Change, 50 (1), 144–163.

- Humpage, O.F. 2015. Paper money and inflation in Colonial America. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary Number 2015–06.

- Jacobson, H. K., and Oksenberg, M., 1990. China's participation in the IMF, the World Bank, and GATT: Towards a global economic order. Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan Press.

- Jao, Y.C., 1983. Hong Kong’s role in financing China’s modernisation. In: A.J Youngston, ed. China and Hong Kong: the economic nexus. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 14–67.

- Kaltenbrunner, A., 2010. International financialization and depreciation: the Brazilian real in the international financial crisis. Competition and change, 14 (3–4), 296–323.

- Kaltenbrunner, A., and Painceira, J.P., 2018. Subordinated financial integration and financialisation in emerging capitalist economies: the Brazilian experience. New political economy, 23 (3), 290–313.

- Keynes, J.M. 1941. Proposals for an International Currency Union. 2nd Draft, 18 November 1941.

- Knoerich, J.M., Pacheco Pardo, R., and Li, Y. 2018. The role of London and Frankfurt in supporting the internationalization of the Chinese Renminbi. New political economy. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1472561.

- Koddenbrock, K., and Sylla, N.S. 2019. Towards a political economy of monetary dependency: the case of the CFA Franc in West Africa. MaxPo Discussion Paper 19/2. Max Planck Sciences Po Center, Paris.

- Konings, M., 2008. The institutional foundations of U.S. structural power in international finance. Review of international political economy, 15 (1), 35–61.

- Kornai, J., 1992. The socialist system. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Kregel, J., 2008. The discrete charm of the Washington Consensus, Working Paper, No. 533. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY

- Lardy, N.R., 1992. Foreign trade and economic reform in China 1978–1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lewis, W.A., 1954. Economic development with unlimited supplies of labour. The manchester school, 22 (May), 139–192.

- McCauley, R. 2005. Distinguishing global dollar reserves from official holdings in the United States. The Bank for International Settlements, BIS Quarterly Review, September 2005.

- McCauley, R., McGuire, P., and Sushko, V. 2015. Global dollar credit: links to US monetary policy and leverage. BIS Working Paper No. 483 January 2015.

- McCauley, R., and Shu, C. 2016. Non-deliverable forwards: impact of currency internationalisation and derivatives reform. BIS Quarterly Review, December, 81–93.

- McCauley, R. N., 2013. Renminbi internationalisation and China’s financial development. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies, 11(2), 101–115.

- McDowell, D., 2019. The (ineffective) financial statecraft of China’s bilateral swap agreements. Development and change, 50 (1), 122–143.

- McNally, C.A., and Gruin, J., 2017. A novel pathway to power? contestation and adaptation in China's internationalization of the RMB. Review of international political economy, 24 (4), 599–628.

- Meade, J.E., 1951. The balance of payments. London: Oxford University Press.

- Mundell, R.A., 1963. Capital mobility and stabilization policy under fixed and flexible exchange rates. Canadian journal of economics and political science, 9 (4), 475–485.

- Noyer, C., 2015. Spheres of influence in the international monetary system. Speech by Mr Christian Noyer, Governor of the Bank of France and Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Bank for International Settlements, 21st Conference of Montreal, Montreal, 8 June 2015.

- Nölke, A., et al., 2015. Domestic structures, foreign economic policies and global economic order: implications from the rise of large emerging economies. European journal of international relations, 21 (3), 538–567.

- Passari, E., and Rey, H., 2015. Financial flows and the international monetary system. The economic journal, 125 (584), 675–698.

- Peoples Bank of China. 2011. Monetary Policy Report, Quarter 1, Beijing PRC.

- Petry, J., 2020. From national marketplaces to global providers of financial infrastructures: exchanges, infrastructures and structural power in global finance. New political economy. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2020.1782368.

- Prates, D.M. 2017. ‘Monetary sovereignty, currency hierarchy and policy space: a post-Keynesian approach’, Texto para Discussão. IE/UNICAMP, 315.

- Reardon, L.C., 2002. The reluctant dragon. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Rey, H. 2013. Dilemma not Trilemma: the global financial cycle and monetary policy independence. Proceedings - Economic Policy Symposium - Jackson Hole, Federal Reserve of Kansas City Economic Symposium, 285–333.

- SAFE. 2019. China's foreign debt structure continues to be optimized. China Finance [In Chinese], No.8, 2019.

- Schenk, C.R. 1997. Monetary institutions in newly independent countries: the experience of Malaya, Ghana and Nigeria in the 1950s. Financial History Review, 4, 181–198.

- Schenk, C., 2010. The decline of sterling: managing the retreat of an international currency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schipke, A., Rodlauer, M., and Zhang, L., 2019. The future of China’s bond market. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Solinger, D.J., 1993. China’s transition from socialism. Armonk, New York: M.E.Sharpe.

- Stigum, M., and Crescenzi, A., 2007. Stigum’s money market (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Strange, S., 1988. States and markets. London: Pinter.

- Sun, G., 2015. Financial reforms in modern China: a frontbencher's perspective. New York: Palgrave.

- Thirlwall, A.P., 2004. Essays on balance of payments constrained growth: theory and evidence, 37. London: Routledge.

- Töpfer, L., and Hall, S., 2017. London’s rise as an offshore RMB financial centre: state-finance relations and selective institutional adaptation. Regional Studies. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1275538.

- Upper, C. and Valli, M., 2016. BIS Quarterly Review, December 2016, 67–80.

- West, R.G., 1978. Money in the colonial American economy. Economic Inquiry, 16 (1), 1–15.

- Xin Zhongguo Wushi Nian Tongji Ziliao Huibian [XZWNTZH], 1999. (Comprehensive statistical data and materials on 50 years of New China). Beijing: Zhongguo Tongji Chubanshe.