ABSTRACT

The macroeconomic policies of advanced economies during the Great Recession were characterised by a curious mixture of unconventional market interventions executed through depoliticised governance structures. We explain this phenomenon by developing a theoretical framework that focuses on the ideational and institutional influence of government-related economic ideas by combining insights of constructivist institutionalism and historical institutionalism. Specifically, we argue that the dominant government-related idea of ‘policy credibility’ – the need to convince markets of government commitment to refrain from ‘politicised’ interventions – was crucial for the adoption of depoliticised macroeconomic interventionism. The ideational dominance of ‘policy credibility’ and its pre-crisis institutionalisation enabled significant policy interventions as long as depoliticised decision-making was maintained and consolidated. We demonstrate this argument through a comparative in-depth analysis of monetary and fiscal policy in two very different cases among advanced economies – the UK and Israel.

Introduction

Macroeconomic policy in advanced economies during the Great Recession was characterised by ‘depoliticised interventionism’ – a combination of unconventional interventions and depoliticised governance. In comparison to the pre-crisis period, this was a curious and novel combination: since the 1980s, the depoliticisation of macroeconomic decision-making had accompanied and supported restricted macroeconomic interventions (e.g. Burnham Citation2001, Flinders and Buller Citation2006). During the Great Recession, the link between depoliticisation and restrained interventions was mostly broken: advanced economies adopted unconventional interventions but further consolidated depoliticised governance institutions like independent central banks and fiscal rules.

What explains depoliticised interventionism during the Great Recession? Depoliticised interventionism reflects a macroeconomic approach that continued to serve the interests of financial institutions in the context of government dependence on financial markets (Braun Citation2016), and more generally to limiting democracy in favour of capitalism (Streeck Citation2014, Madariaga Citation2020, Stahl Citation2020). Nevertheless, the question that remains is: which considerations have guided macroeconomic policymaking given the destabilising economic circumstances, which from the policymakers’ perspective were unexpected and generated uncertainty?

We answer this question by developing a theoretical framework that combines the insights of constructivist institutionalism (CI) and historical institutionalism (HI) and focuses on the unique political influence of ‘government-related ideas’ on economic policymaking. We define government-related economic ideas as causal and normative beliefs about how decision-making procedures and institutions affect the economy and how governments should make economic policy decisions (Mandelkern Citation2015, Citation2019). A prominent example is Public Choice theory, which argues that democratic decision-making produces socioeconomic malaise (Hay Citation2007, Madariaga Citation2020). In contrast to ‘policy-related economic ideas’, which pertain to what actions governments should (or should not) pursue (e.g. Dellepiane-Avellaneda Citation2015, Moschella Citation2015, Farrell and Quiggin Citation2017, Clift Citation2018), government-related economic ideas focus on how decisions regarding these actions are made. We suggest that this distinction is crucial, since dominant government-related ideas enjoy a unique combination of ideational and institutional power: they affect both the dominant discourse and actors’ beliefs and decision-making rules and structures.

Our main argument is that, during the Great Recession, the dominant government-related idea that prompted depoliticised macroeconomic interventionism was ‘policy credibility’: the belief that successful economic policies depend on a government’s ability to convince markets in its long-term commitment to refrain from future ‘politicised’ interventions, mostly by adopting depoliticising institutions that ‘tie governments hands’ (Burnham Citation2001, Flinders and Buller Citation2006). In the context of the crisis, this meant that successful interventions depended on government commitment to refrain from any action not required for economic stabilisation.

Crucially, the pre-crisis dominance of ‘policy credibility’ also guided the institutionalisation of depoliticised decision-making arrangements, most prominently central bank independence, inflation targets, and fiscal rules. When the crisis erupted, this notion continued to affect macroeconomic policymaking, not only due to its ideational dominance but also thanks to its pre-crisis institutionalisation, which had empowered technocratic bodies like central banks and finance ministries (Blyth and Matthijs Citation2017, Miró Citation2021).

This combination of ideational and institutional dominance, affected both the further consolidation of depoliticised macroeconomic governance and the interventions selected. Specifically, macroeconomic interventions were possible, and even desirable, if they did not risk a government’s long-term commitment to avoiding politicised interventions. Therefore, monetary interventions undertaken by independent central banks were strongly preferred over politician-controlled fiscal interventions. Concurrently, depoliticised institutions were consolidated to reaffirm government credibility in the context of unconventional interventions, thereby signalling to markets that interventions would not be politically repurposed in the future.

This argument contributes to the literatures on the political influence of economic ideas and on depoliticisation, on which it relies. First, suggesting that ideational influence both shapes and depends on institutional context and historical legacy demonstrates the potential synergy between CI and HI. Second, regarding depoliticisation, our argument suggests that the historical consolidation of depoliticising discourses and decision-making institutions actually affects policymakers’ choices. Even if depoliticisation is initiated as a political tactic of blame avoidance and arena shifting (Burnham Citation2001, Flinders and Buller Citation2006, Wood and Flinders Citation2014, but see Hay Citation2007, Citation2014), its long-term institutionalisation and discursive dominance impact how decision-makers think about and justify their actions.

We demonstrate our argument by comparing macroeconomic policymaking in the UK and Israel at the height of the Great Recession (2008–2010). Our in-depth comparative analysis demonstrates how the notion of policy credibility contributed to a similar depoliticised interventionism in these otherwise very different cases among advanced economies. In our conclusion, we suggest that this notion continuously affects macroeconomic policymaking, most recently in countries’ economic response to Covid-19. Indeed, post-crisis backlashes like the Brexit vote and Israeli social protests suggest that designing macroeconomic policies according to their market credibility does not guarantee, and might even hinder, their popular credibility. Nevertheless, these backlashes have so far generated limited changes to the institutional and discursive dominance of ‘policy credibility’.

The puzzle of depoliticised interventionism

Between the 1980s and the Great Recession, the macroeconomic policies of advanced economies were characterised by depoliticised and restrained interventions. Short-term interest rates set by central banks were essentially the only policy instrument used for macroeconomic stabilisation, while counter-cyclical deficit spending was completely abandoned (Ban Citation2015, Moschella Citation2015, Clift Citation2018). Concurrently, and in support of restrained intervention, governments depoliticised macroeconomic decision-making institutions by delegating monetary policy discretion to independent central banks, adopting low inflation targets (Widmaier Citation2016, Best Citation2019, McPhilemy and Moschella Citation2019, Woodruff Citation2019), and legislating fiscal rules (McDaniel and Berry Citation2017).

The Great Recession shifted the macroeconomic policy of advanced economies toward what we term ‘depoliticised interventionism’. Interventionism profoundly characterised monetary policy: beyond slashing their interest rates, central banks used various ‘unconventional’ instruments like quantitative easing (QE) and negative interest rates to stimulate economic activity (Moschella Citation2015, Clift Citation2018, McPhilemy and Moschella Citation2019, Reisenbichler Citation2020). The deployment of counter-cyclical deficit spending, although limited in time and extent, also reflected a change (Ban Citation2015, Clift Citation2018). Concurrently, governments maintained and strengthened depoliticised macroeconomic governance: central bank independence was preserved (Johnson et al. Citation2019, McPhilemy and Moschella Citation2019, Woodruff Citation2019) and fiscal rules were merely adjusted to the post-crash context (McDaniel and Berry Citation2017, Matthijs and Blyth Citation2018, Miró Citation2021).

Importantly, depoliticised interventionism also characterised the policies implemented throughout the 2010s. QE programmes were implemented until late 2014 in the US, since 2014 in the Euro Area, and periodically throughout the whole decade in the UK and Japan (Dell’Ariccia et al. Citation2018, Reisenbichler Citation2020). The European Central Bank (in 2014) and the central banks of Japan, Sweden, Denmark, and Switzerland (in 2016) have all resorted at some point to negative interest rates . Crucially, these ‘monetary’ policies break the boundaries of the conventional definition of monetary policy: for example, QE programmes that buy government bonds directly support fiscal policy and public debt financing (Braun Citation2018, Clift Citation2018, p. 169). Thus, these policies reflect depoliticised macroeconomic interventionism and not merely depoliticised monetary interventionism.

Moreover, depoliticised interventionism challenges the pre-crisis association between depoliticisation and macroeconomic restraint. The assumption behind depoliticisation was that public debts and inflation result from democratic decision-making (Hay Citation2007, Stahl Citation2020). Restrained interventions and depoliticised governance were meant to serve the same macroeconomic goals of price stability and fiscal consolidation (Blyth and Matthijs Citation2017). Depoliticised interventionism does not undermine those goals but reflects a divorce between depoliticisation and macroeconomic restraint that has not been anticipated by the depoliticisation literature (Burnham Citation2001, Wood and Flinders Citation2014).

In short, even if the crisis did not generate a political–economic regime shift (Blyth and Matthijs Citation2017), the turn toward depoliticised interventionism means that some important policy changes have occurred (Clift Citation2018). What explains this turn from depoliticised restraint to depoliticised interventionism? One valid answer is that pre-crisis depoliticised restraint and post-crisis depoliticised interventionism both correspond to financialised capitalism and serve the interests of global finance, mainly by limiting democratic institutions whose logic contradicts that of capitalist institutions (e.g. Madariaga Citation2020, Streeck Citation2014, Stahl Citation2020). While agreeing with this view, we assume that policy choices do not directly derive from structural conditions and interests, especially when policymakers operate under new and unexpected circumstances. Which of the considerations held by decision-makers’ have linked the structural conditions of financialised capitalism with the policy choices of depoliticised interventionism?

Theory: ideational and institutional influence of government-related ideas

In line with CI, our underlying assumption is that ideas affect macroeconomic policy preferences and choices, especially during economic crises (Baker and Underhill Citation2015, Widmaier Citation2016). As macroeconomic policy is a highly complex field, actors require ideas to define their interests and goals and possible ways of achieving them (Clift Citation2018). Such ‘demand’ for ideas is accentuated during a deflationary crisis rooted in a financial meltdown, like the Great Recession, which is surrounded by deep uncertainties regarding its causes and possible solutions. Concurrently, there is an abundant ‘supply’ of macroeconomic theories and policy-relevant ideas (e.g. Ban Citation2015, Helgadóttir and Ban Citation2021) and of economists in academic, government, and international institutions who carry these ideas into the decision-making process (e.g. Christensen Citation2017, Farrell and Quiggin Citation2017).

Accordingly, numerous studies have analysed ideational influence on macroeconomic policy following the Great Recession, focusing among other things on how Keynesian ideas and economists – and their counterparts – have influence fiscal policies (e.g. Baker Citation2015, Ban Citation2015, Dellepiane-Avellaneda Citation2015, Farrell and Quiggin Citation2017) and on ideational change and continuity in monetary policy (e.g. Moschella Citation2015, Braun Citation2016, Johnson et al. Citation2019). However, the main focus in prevailing studies is on policy-related ideas – theorisations on the causal effects of government economic interventions (e.g. fiscal consolidation encourages/depresses growth) and on whether and how governments should intervene in the economy. This focus limits our ability to solve the puzzle of depoliticised interventionism, which pertains not only to post-2008 interventions but also to decision-making structures.

To overcome this limit, we develop a theoretical framework focusing on how government-related ideas shaped advanced economies’ macroeconomic policies during the crisis. We define government-related economic ideas as causal beliefs regarding how decision-making structures and processes affect the economy and how these structures and processes should be organised and institutionalised: through which routines and procedures, who should and should not take part in the policymaking process, etc. (Mandelkern Citation2015, Citation2019). This distinction between the influence of policy-related and the influence of government-related ideas crosses and adds to Hall’s (Citation1993) classic distinction between ‘orders’ of change. For example, interest cuts and QE are first-order and second-order policy-related changes, whereas adoption and/or adaptation of fiscal rules and central bank independence reflect first-order and second-order government-related changes.

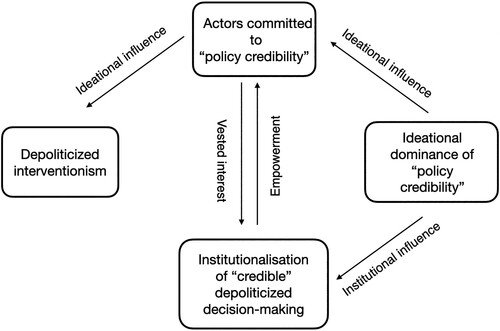

Our basic theoretical argument is that dominant government-related ideas have a twofold influence on the policymaking process since they affect not only what political actors believe, but also the institutional structure and norms of the policymaking process. Accordingly, our theoretical framework combines insights from both CI and HI. Following CI, we suggest that dominant government-related ideas inform and guide decision-making structures and thereby become integrated into it. Following HI, we suggest that this institutional change empowers certain actors who then have a ‘vested interest’ in protecting the ideas that have empowered them. This combination of ‘power through ideas’ (ideational persuasiveness) with ‘power in ideas’ (institutional hegemony which sets discursive limits) (Carstensen and Schmidt Citation2016) amplifies the resilience and impact of dominant government-related ideas. The institutional effect of government-related ideas has crucial consequences since ideational influence is conditioned by how political power and legitimate authority are distributed (Matthijs and Blyth Citation2018, Berry Citation2020, Madariaga Citation2020), as well as by the institutional context in which ideational exchange takes place (Baker Citation2015, Baker and Underhill Citation2015, Farrell and Quiggin Citation2017, Clift Citation2018). Accordingly, actors with greater institutional power and political legitimacy enjoy greater ideational influence.

We further suggest that, in the context of crisis and uncertainty, government-related economic ideas that were dominant before the crisis would be more resilient than parallel policy-related ideas. The reason for this is that their discursive and ideational dominance is reinforced by their institutionalisation in decision-making rules and processes and in the actors they have empowered. Accordingly, we expect dominant government-related economic ideas to shape the policymaking discourse during a crisis and to affect the legitimacy and plausibility of different policies. Specifically, we expect dominant government-related ideas to lend support to the maintenance of prevailing decision-making structures and to interventions conducted by the governmental institutions they empowered from the outset. We also expect that dominant government-related ideas will limit and restraint interventions that do not conform to them.

The ideational-institutional influence of ‘policy credibility’ in the Great Recession

Applying this theoretical framework to the context of the Great Recession, we suggest that depoliticised macroeconomic interventionism was guided by the dominant government-related economic idea of ‘policy credibility’. We define ‘policy credibility’ as the belief that successful economic policies depend on the ability of a government to convince markets in its long-term commitment to refrain from politicised – hence investment-depressing – interventions like taxation or nationalisation. In the context of macroeconomic policy, this belief is formulated in Rational Expectations theory (Hay Citation2007, Stahl Citation2020, Helgadóttir and Ban Citation2021) and emphasises the need to reassure market actors that governments will keep their public finances sound and refrain from inflationary measures. We regard ‘policy credibility’ as a government-related idea since it is assumed that governments have to ‘tie their hands’ by institutionalising depoliticised governing structures to enhance their credibility (Burnham Citation2001, Wood and Flinders Citation2014). In the context of macroeconomic policy, this means the adoption of fiscal rules, central bank independence, and inflation targets (Clift and Tomlinson Citation2006, Widmaier Citation2016, Best Citation2019). In line with Public Choice and accompanying theories that assume that democratic institutions like elections undermine government credibility, such instruments limit democratic influence on macroeconomic decision-making (Hay Citation2007, Best Citation2019, Stahl Citation2020).

Policy credibility is a central pillar in the neoliberal paradigm and was a dominant idea in macroeconomic policy discourse throughout the decades before the Great Recession (Burnham Citation2001, Clift and Tomlinson Citation2006, Hay Citation2007, Best Citation2019, Stahl Citation2020). The adoption of credibility-enhancing institutional reforms by the governments of virtually all advanced capitalist democracies demonstrates this well (McPhilemy and Moschella Citation2019). When the crisis erupted, this meant that ‘policy credibility’ was still a dominant economic idea, as exemplified by the policy discourse within central banks (Johnson et al. Citation2019) and the IMF (Ban Citation2015, Clift Citation2018). This idea was also well-embedded in the institutional structure of macroeconomic governance and was closely associated with the interests of powerful macroeconomic policymakers.

As summarises, we suggest that the pre-crisis dominance of ‘policy credibility’ had a combined ideational and institutional effect when the crisis erupted. The prevailing structure of macroeconomic governance substantially empowered non-elected bodies, most prominently central banks and finance ministries (Woodruff Citation2016, Citation2019, McPhilemy and Moschella Citation2019, Stahl Citation2020). Despite the well-known differences between these two types of body, we argue that they shared a commitment to ‘policy credibility’ that conformed with their vested interest in maintaining the prevailing depoliticised structure of macroeconomic governance. Concurrently, their empowered position allowed them to influence macroeconomic policymaking in line with the idea of ‘policy credibility’.

Indeed, in contrast to interpretations of depoliticisation as a political tactic politicians can use without significantly giving up their autonomy (Burnham Citation2001; Flinders and Buller Citation2006, but see Hay Citation2007), we suggest that depoliticisation may have long-term discursive and institutional effects that limit possible venues for action. Specifically, the implementation of such arrangements is expected to shape the mindset of policymakers and/or reduce their willingness to curtail central bank independence and/or relax fiscal rules, given the anticipated political and economic prices of such actions.

Operating according to ‘policy credibility’ guidelines in the Great Recession meant working to reassure market actors that ‘economically necessary’ interventions for reviving financial markets and the economy would not become persistent interventions serving ‘politicised’ purposes. Accordingly, interventions in support of financial markets were deemed credible by definition, whereas interventions in support of citizens’ needs, which might induce additional popular demands and expand politicised interventions, were deemed riskier to government credibility (see also Farrell and Quiggin Citation2017). Relatedly, temporary and easily reversible fiscal support was justified, but not longer-term fiscal expansion. In addition, interventions managed by depoliticised bodies like central banks were considered credible since they did not pose long-term risks of becoming politicised interventions, whereas the opposite was true for interventions depending on politicians’ discretion. Generally, the ‘policy credibility’ logic allowed for very significant macroeconomic interventions that aimed to save the financial system and/or were managed by central banks. That same logic limited interventions that were carried out by elected governments and/or which aimed to provide fiscal support for citizens.

Following this logic also meant that depoliticised macroeconomic governance had to be maintained and further consolidated. First, no change was required in the general structure of prevailing macroeconomic governance, which was originally set to enhance ‘policy credibility’. In addition, in the context of extensive and extraordinary interventions, ‘policy credibility’ encouraged additional depoliticisation of policymaking institutions which would reassure market actors that new forms of intervention would not be eventually politicised (Ban Citation2015, Johnson et al. Citation2019).

Crucially, we argue that the influence of ‘policy credibility’ in enabling and directing macroeconomic policies was continuous throughout the whole period of the Great Recession (2008–2010). While we do not challenge prevailing claims regarding the influence of other political–economic factors, not least other (policy-related) economic ideas, we do argue that the ideational and institutional dominance of ‘policy credibility’ made its political influence particularly persistent. In contrast to the debates and disagreement with regard to policy-related ideas, for example between Keynesian ideas and economists and their ‘austerity’ counterparts (Dellepiane-Avellaneda Citation2015, Farrell and Quiggin Citation2017), belief in ‘policy credibility’ was consensual among economic experts.

Research design

We substantiate these arguments by utilising an in-depth analysis of two very different advanced economies, the UK and Israel, during the height of the Great Recession (2008–2010). summarises key macroeconomic indicators that demonstrate the differences between the two countries in terms of international economic position and government finances before the crisis. As a centre for global financial markets, the UK was directly hit by the financial meltdown, which Israel avoided thanks to it peripheral location and conservative financial system. Therefore, in comparison to the UK, the global slowdown affected Israel relatively mildly.

Table 1. Main macroeconomic indicators (OECD stats).

In addition, while both are unitary and parliamentary democracies with a relatively autonomous public sector, the UK and Israel also differ in the structure of their political systems. Unlike the UK, Israel’s proportional elections fragment the party system and require the formation of relatively unstable coalition governments. The two countries also differed in terms of the political orientation of the governing parties during the research period, and in terms of the status of economic issues on the public agenda (which was comparatively low in Israel). The policymaking role of Israeli politicians was further limited between September 2008 and March 2009 when a transition government was in place.

We enhance our comparative approach by analysing monetary policy and fiscal policy within each country. While these two policy domains are interrelated, different institutional arrangements characterise each. Most prominently, monetary policy is much more insulated from the influence of elected politicians. Thus, we hypothesise that ‘policy credibility’ has affected policy decisions in both domains, but differentially. Our theoretical argument would be further supported if the empirical analysis reveals that in each of these policy domains ‘policy credibility’ has played a similar role in both countries.

In line with the congruence method (George and Bennett Citation2005), our main goal is to examine whether the empirical facts agree with our theoretical argument. Accordingly, the empirical analysis will support our theoretical argument if macroeconomic policies were repeatedly explained, justified, and/or directed by the need for governments to maintain their long-term commitment to refrain from politicised interventions. Our theoretical argument would be further supported if these references were made by technocratic bodies – central banks and treasuries.

The sources we use include all the policy documents that were published by the central banks and treasuries of the UK and Israel in 2008–2010 and which pertained to macroeconomic policies in both countries during the crisis. These include both regular periodical publications – like Yearly Reports and Price Stability Reports of the central banks and Budget Documents – and ad hoc reports, documents, and press announcements published in response to the crisis. In addition, we have relied on minutes of meetings of relevant parliamentary committees that discussed and investigated the macroeconomic policy response during the crisis.

Depoliticised macroeconomic interventionism in the UK and Israel

The macroeconomic policy responses to the Great Recession in the UK and Israel, and their parallel pattern of depoliticised interventionism, are summarised in . The fiscal interventions in both countries were substantial but short-term. In the UK, the government first launched a massive bail-out of banks and building societies in October 2008 (HM Treasury Citation2012, pp. 20–2). A second stimulus package was launched in November 2008 (HM Treasury Citation2008a) and included a temporary VAT reduction, income tax relief for lower-income families, and some relatively small-scale social protection programmes (HM Treasury Citation2008a, p. 1). Concurrently, the government allowed automatic stabilisers to work to ‘help smooth the path of the economy’ (HM Treasury Citation2010, p. 20). Automatic stabilisers were also allowed to operate in full in Israel, where a limited fiscal stimulus plan was executed. While the stimulus plan was relatively mild (1.3% of GDP in 2009 and 2010) and was joined by temporary parallel rises in VAT, it reflected a clear deviation from the past rejection of any fiscal counter-cyclical action.

Table 2. Macroeconomic policy responses to the Great Recession, 2008–2010.

Monetary policy was even bolder in both countries. The central banks of both countries slashed their interest rates and operated unconventional and unprecedented interventions. In the UK, these included the expansion of the bank Special Liquidity Scheme (which allowed distressed banks to swap illiquid assets for Treasury bills) and a £375 billion QE programme. Concurrently, the Bank of Israel (BoI) started operating a massive foreign currency purchasing programme (BoI Citation2010b) that aimed to devalue the shekel and support Israeli exports, as well as a limited QE-like programme of government bonds purchases (BoI Citation2010a).

In parallel to these macroeconomic interventionist measures, prevailing decision-making structures were maintained and further consolidated. In both countries, the institutional framework for monetary policy – which was based on central bank independence and monetary targets (Burnham Citation2001, Flinders and Buller Citation2006) – was maintained. In Israel, this framework was enhanced with the passing of a new BoI law in 2010, which inter alia prohibited the dismissal of a governor if the government disagreed with her policy (Maman and Rosenhek Citation2011). Likewise, the fiscal frameworks in both countries, which were based on a set of fiscal rules (Clift and Tomlinson Citation2006, Mandelkern Citation2019, Maron Citation2021), were amended, while their depoliticised structure was maintained. In the UK, the Labour government legislated the Fiscal Responsibility Act in 2010, which set a medium-term commitment for deficit reduction, and in May 2010 the incoming Conservative–led government established an independent fiscal watchdog agency, the Office for Budget Responsibility. In addition, United Kingdom Financial Investment (UKFI) was formed as a limited company owned by HM Treasury to manage (at arm’s length from political control) the government’s holdings in financial institutions that had been bailed out (HM Treasury Citation2010). In Israel, the fiscal framework, which was based on a deficit rule and on an expenditure rule, was amended in 2010, when the 1.7% year-on-year cap expenditure rule was replaced by a formula. The new formula allowed higher spending increases (conditioned by debt levels), but further consolidated the prevailing rules-based fiscal framework (Magal-Shamir Citation2021).

Effect of ‘policy credibility’ on macroeconomic policy interventions

‘Credible’ fiscal intervention

Generally, policymakers in both countries referred to fiscal expansion as legitimate if it did not risk the overall credibility of the fiscal framework, which anchored the government’s long-term commitment to fiscal prudence and price stability. In the UK, the prevailing Code of Fiscal Stability allowed the government to deviate temporarily from fiscal rules and to operate discretionary fiscal action ‘in response to clear and explicitly identifiable shocks’, as long as it maintained its ‘long-term commitment to reduce public debt’ (HM Treasury Citation1998, pp. 16, 20, Citation2008b, p. 2). The underlying assumption was that the government was operating under ‘exceptional uncertainty’, and therefore ‘fiscal policy has the flexibility to respond appropriately while remaining committed to clear […] long-term goals […] as provided in the Code for Fiscal Stability’ (HM Treasury Citation2008b, pp. 4–5). Similarly, in its 2010 Budget, the government detailed ‘the tough choices’ it was making to build ‘a credible fiscal consolidation plan to ensure sustainable public finances as a key part of [its] macroeconomic strategy’ of living ‘within its means in a responsible way’ (HM Treasury Citation2010, pp. 3, 6–7).

A very similar logic was applied in Israel, even though this kind of exceptional short-term flexibility was not formally defined. Accordingly, the recommendations for fiscal action issued by the BoI suggested that ‘the nature of the crisis requires action to enhance aggregate demand’ (BoI Citation2009b, p. 7), the effectiveness of which required that market actors should ‘know’ the government’s intentions and believed its long-term commitment to fiscal responsibility:

Expansionary fiscal policy […] may be effective, but for that purpose individuals must be persuaded that it does not pose a potential risk of continuous deviation from the route of decreasing the debt/GDP ratio. (BoI Citation2009a, p. 224)

Accordingly, the first guiding principle of the Ministry of Finance (MoF)’s crisis programme was ‘maintaining fiscal credibility by clearly committing to decrease the budgetary deficit in the coming years’ (MoF Citation2009a, Citation2009b). Likewise, there was an agreement that automatic stabilisers should operate freely and fully, while additional discretionary stimulus was more questionable. The reason for this was that automatic stabilisers had mainly generated a decline in revenues and therefore did not violate the expenditures cap (BoI Citation2009b, p. 16). A deficit induced by automatic stabilisers was considered more credible since it also resulted from pre-crisis institutionalised policies rather than from political short-termism.

The adherence to ‘policy credibility’ affected not only the possibility and extent of fiscal expansion, but also its composition. Specifically, spending in support of financial markets – the main target audience of credibility-enhancing efforts – was considered inherently legitimate, whereas increased government spending for social purposes had to be justified and compensated for by parallel tax increases.

In the UK, policymakers considered the rescue of financial institutions as the only way to prevent a total financial meltdown (HM Treasury Citation2008a, pp. 2, 4–5, TSC Citation2009a, pp. 4, 34–35) and therefore as enhancing the credibility of macroeconomic policy. As the 2009 Budget stated, ‘during a period when […] the operation of financial markets and monetary policy are impaired, it is appropriate for the government to allow borrowing to rise to support the economy’ as long as it sets ‘a credible plan to reduce borrowing’ in the mid-term (HM Treasury Citation2009, p. 30). In contrast, since the expansion of social spending in the second stimulus package was considered to threaten fiscal credibility, it was offset by temporary and permanent tax increases, ‘efficiency savings’ across government departments in the following year, and deep cuts to unemployment-related expenditures (HM Treasury Citation2009, pp. 3, 5, 128). In Israel, where the government did not have to bail out financial institutions, the government similarly increased VAT to compensate for spending increases that bypassed the expenditure rules ‘in order to keep the deficit framework’ (MoF Citation2009a).

The similarities between the Israeli and British fiscal responses are striking, as are their justifications, especially given the substantial differences between the economic conditions of both countries. In both countries, fiscal intervention was conditioned on the belief that it did not harm the government’s credible commitment to long-term fiscal prudence. This was especially true with regard to fiscal interventions in the form of social support: decision-makers in both countries saw a need to compensate for these fiscal expansions by parallel regressive VAT raises so that their fiscal credibility would not be risked.

‘Credible’ monetary intervention

Massive monetary interventions were considered as substantially less risky for ‘policy credibility’ than fiscal interventions, primarily since they were conducted by central banks that were independent of political interference. Accordingly, the UK Treasury defined QE as a credible monetary strategy because it was based on ‘the principles of full operational independence, openness, transparency and accountability’ of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) (HM Treasury Citation2009, p. 23). A few years later, in commemorating 20 years of central bank independence, Ian McCafferty (Citation2017, p. 3) of the MPC clarified the underlying logic of QE, arguing that:

operational independence does more than simply remove monetary policy from the political arena to build credibility. That credibility also allows the Bank to be nimble and innovative in adapting its tools to deal with […] serious shocks to the system. [T]his was demonstrated clearly in recent years as the MPC […] was required to [employ] unconventional policy tools […] most noticeable the purchase of gilts and other financial instruments.

the Bank’s scope to exercise [QE] […] is founded on the credibility built up through its success in achieving the inflation target in the past, and its clarity in communications when it uses it. (TSC Citation2013, p. 41)

[T]he establishment of monetary policy credibility and low inflationary environment […] have allowed [the Bank] to enact a very expansionary monetary policy without the risk of losing policy credibility. (BoI Citation2010a, p. 25)

Policy credibility concerns were not just obstacles to monetary interventions: they were also their justification. Before halting the first QE round, the MPC emphasised the important role of monetary intervention, in the form of QE, for maintaining the credibility of its monetary policy framework. Andrew Sentance, an external member of the MPC, explained that

one reason I supported this policy […] was that I felt it was very important for the credibility of the MPC and our monetary framework to show that we were prepared to use all levers to stabilise the real economy. (TSC Citation2009b)

The very message of the Bank, that in the face of crisis threats it intends to use as much as necessary the tools at its disposal to support economic activity and ensure the soundness of financial institutions and markets, has played an important role in restoring the confidence of the public in general and investors in particular, and thereby contributed to the recovery of the economy from the crisis.

The effect of ‘policy credibility’ on macroeconomic decision-making

The dominance of the ‘policy credibility’ idea has not only affected monetary and fiscal interventions, but also the maintenance and further consolidation of depoliticised macroeconomic decision-making. In the response to the Great Recession this was especially visible in the fiscal sphere, where policymakers saw interventions as generating clearer credibility risks that had to be compensated for by credibility-enhancing institutional changes.

In the UK, the government responded to the increase in its deficit and the suspension of its fiscal rules by announcing ‘a ‘temporary operating rule’ already by late 2008. This rule required the government to reduce the cyclically adjusted deficit year by year once the economy emerges from the downturn’ (Hodson and Mabbett Citation2009, p. 1053). This temporary institutional change was accompanied by the Fiscal Responsibility Act 2010, which aimed to offer a ‘credible path of fiscal consolidation’ (HM Treasury Citation2010, p. 1). Later on, in 2010, the Tories followed the same logic of credibility when setting up the independent Office for Budget Responsibility to ‘restore trust in the government’s ability to manage the public finances’ (The Conservative Party, cited in Carstensen and Matthijs Citation2017, p. 443).

In the context of a (relatively) substantial fiscal expansion, institutional changes were considered as crucial credibility-enhancing means also in Israel. At the height of the crisis, BoI and MoF officials, as well as economists from academia, stressed the importance of adopting credibility-enhancing instruments alongside the government’s concrete fiscal actions (KFC Citation2009). As in the UK, the instruments suggested mainly included additional and/or renewed rules, as well as enhanced transparency. The BoI also suggested considering the adoption of a new fiscal rule to demonstrate the government’s principled commitment to fiscal prudence (BoI Citation2009b, pp. 27–28). This line of thinking influenced the 2010 amendment of the fiscal expenditures rule developed by the MoF and the National Economic Council (NEC), based on a formula anchoring the government’s commitment to long-term reduction of the public debt. As the NEC explained, a central goal of the new rule was ‘to improve the ability to counter beforehand the growing pressures for uncontrollably breaking the previous rule, which could lead to the loss of hard-earned fiscal credibility’.Footnote2

A key difference between the UK and Israel was the effect of the crisis on financial markets, which led only the UK government to bail out financial institutions. In this context, the UK government also saw a need to institutionalise a limited company that would manage nationalised financial assets, emphasising that ‘[t]he governance of UKFI will be consistent with the Government’s intention to manage its investments on a commercial and arm's-length basis and not intervene in day-to-day management decisions’ (HM Treasury Citation2008a).

As mentioned above, monetary interventions were considered to be credible in the first place since they were conducted by an independent central bank and provided support for the financial market. Policymakers were thus not concerned with ‘institutional compensations’ for these interventions. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that in Israel the BoI law was amended in 2010 so that the BoI’s de facto independence would be anchored in de jure legislation (one of the reasons even opposition leaders supported the amendment was the active approach of the Bank during the crisis).

Discussion and conclusions

The comparison of monetary and fiscal policies in the UK and Israel demonstrates how the notion of ‘policy credibility’ affected the macroeconomic policy responses of advanced economies to the Great Recession. Given the essential differences between these two countries, the similarities between them in terms of the role of ‘policy credibility’ in guiding and justifying these policy responses are striking. The influence of ‘policy credibility’ derives from its qualities as a government-related economic idea, which primarily pertains to a government’s appropriate decision-making structures. Accordingly, macroeconomic policies were assessed and justified according to who manages them and by which rules. Monetary interventions, conducted by independent – hence depoliticised – central banks, were legitimate, whereas potentially politicised fiscal interventions were considered as risking credibility. They were therefore compensated for by fiscal consolidation measures and depoliticising – hence credibility-enhancing – institutional changes.

While policy credibility was not the only idea that affected the macroeconomic response to the Great Recession, its influence has been uniquely persistent and has interacted with that of different policy-related ideas. Most prominently, even as Keynesian ideas enjoyed influence when the crisis began, ‘policy credibility’ limited fiscal expansion and guided its execution. Furthermore, adherence to ‘policy credibility’ anticipated the budget cuts that followed fiscal expansion, meaning that austerity was part of the stimulus ‘package’ right from the beginning. Adherence to ‘policy credibility’ also explains the differential application of monetary policy and fiscal policy, suggesting that extensive monetary intervention was not a functional response to the insufficient fiscal action of incompetent governments. From a ‘policy credibility’ perspective, this was the appropriate policy mix in the first place.

‘Policy credibility’ seems to have affected depoliticised intervention in additional contexts. For example, in the unique institutional context of the EU, intervention was conditioned upon first implementing credibility-enhancing governing institutions (Woodruff Citation2016). More recently, central banks have led the economic response to Covid-19, especially during the early stages of the pandemic. The most conspicuous influence of ‘policy credibility’ during the pandemic pertains to the monetary financing of government deficits. In the context of unexpectedly high public spending, leading macroeconomists approvingly discussed this tabooed practice if (credibly) managed by independent central banks (e.g. Blanchard and Pisani-Ferry Citation2020). The temporary financing of government borrowing by the BoE reflects the first such experimentation, justified by market confidence in the BoE’s independence (The Economist Citation2020).

The policies guided by ‘policy credibility’ have also been challenged since the crisis. In the UK, ‘credible’ fiscal policies have contributed to anti-austerity protests and possibly to the Brexit vote. In Israel, extensive monetary expansion contributed to rising housing prices, which fuelled massive social protests. Thus, we might cautiously say that adherence to market credibility does not guarantee, and might even hinder, popular credibility. Nevertheless, we doubt that the backlashes generated by the lack of popular credibility have so far undermined the institutional and discursive dominance of ‘policy credibility’.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge our colleagues for their comments on earlier versions of this paper: Alexandre Afonso, Amit Avigur-Eshel, Cornel Ban, Mark Blyth, Bob Hancké, Alexander Kentikelenis, Matthias Matthijs, Manuela Moschella, Elizabeth Popp-Berman, Alexander Reisenbichler, Ze'ev Rosenhek and Vivien Schmidt, as well as the participants in the ‘Politics Without Choice’ ECPR Joint Sessions workshop (April 2018). The usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In 2011, however – when economic conditions remained sluggish – the MPC expanded its QE operation even when inflation stood at 4.5% (TSC Citation2013, pp. 97–98).

2 NEC website, https://economy.pmo.gov.il/CouncilActivity/Documents/fiscal180917.docx [accessed 12 September 2021].

References

- Baker, A., 2015. Varieties of economic crisis, varieties of ideational change: how and why financial regulation and macroeconomic policy differ. New political economy, 20 (3), 342–366. doi:10.1080/13563467.2014.951431.

- Baker, A. and Underhill, G.R.D., 2015. Economic ideas and the political construction of the financial crash of 2008. The British journal of politics and international relations, 17 (3), 381–390. doi:10.1111/1467-856X.12072.

- Ban, C., 2015. From designers to doctrinaires: staff Research and fiscal policy change at the IMF. In: Elites on trial Vol. 1–0. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 337–369. Available from: https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/10.1108/S0733-558X20150000043024.

- Berry, C., 2020. From receding to reseeding: industrial policy, governance strategies and neoliberal resilience in post-crisis Britain. New political economy, 25 (4), 607–625. doi:10.1080/13563467.2019.1625316.

- Best, J., 2019. The inflation game: targets, practices and the social production of monetary credibility. New political economy, 24 (5), 623–640. doi:10.1080/13563467.2018.1484714.

- Blanchard, O., and Pisani-Ferry, J. 2020. Monetisation: do not panic. VoxEU.Org, Apr 10. Available from: https://voxeu.org/article/monetisation-do-not-panic.

- Blyth, M. and Matthijs, M., 2017. Black swans, lame ducks, and the mystery of IPE’s missing macroeconomy. Review of international political economy, 24 (2), 203–231. doi:10.1080/09692290.2017.1308417.

- BoE, 2010. Inflation report.

- BoI, 2009a. Annual report 2008 [Hebrew].

- BoI, 2009b. Israel and the global crisis: policy recommendations for the government [Hebrew].

- BoI, 2010a. Annual report 2009 [Hebrew].

- BoI, 2010b. Barry Topf, director of the Bank of Israel market operations department, addressed today the Knesset finance committee, November 2. http://www.boi.org.il/en/NewsAndPublications/PressReleases/Pages/101103b.aspx.

- Braun, B., 2016. Speaking to the people? Money, trust, and central bank legitimacy in the age of quantitative easing. Review of international political economy, 23 (6), 1064–1092. doi:10.1080/09692290.2016.1252415.

- Braun, B., 2018. Central bank planning? Unconventional monetary policy and the price of bending the yield curve. In: J. Beckert, and R. Bronk, eds. Uncertain futures: imaginaries, narratives, and calculation in the economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Burnham, P., 2001. New labour and the politics of depoliticisation. British journal of politics & international relations, 3 (2), 127.

- Carstensen, M.B. and Matthijs, M., 2017. Of paradigms and power: British economic policy making since thatcher. Governance, 31 (3), doi:10.1111/gove.12301.

- Carstensen, M.B. and Schmidt, V.A., 2016. Power through, over and in ideas: conceptualizing ideational power in discursive institutionalism. Journal of European public policy, 23 (3), 318–337. doi:10.1080/13501763.2015.1115534.

- Christensen, J., 2017. The power of economists within the state. Stanford University Press. Available from: https://www.sup.org/books/extra/?id=25636&i=Chapter%201.html.

- Clift, B., 2018. The IMF and the politics of austerity in the wake of the global financial crisis. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Clift, B. and Tomlinson, J., 2006. Credible Keynesianism? New labour macroeconomic policy and the political economy of coarse tuning. British journal of political science, 37 (01), 47. doi:10.1017/S0007123407000038.

- Dell’Ariccia, G., Rabanal, P., and Sandri, D., 2018. Unconventional monetary policies in the Euro Area, Japan, and the United Kingdom. Journal of economic perspectives, 32 (4), 147–172. doi:10.1257/jep.32.4.147.

- Dellepiane-Avellaneda, S., 2015. The political power of economic ideas: the case of ‘expansionary fiscal contractions’. The British journal of politics & international relations, 17, 391–418. doi:10.1111/1467-856X.12038.

- The Economist, 2020. Why the Bank of England is directly financing the deficit. The Economist, April 18. https://www.economist.com/britain/2020/04/18/why-the-bank-of-england-is-directly-financing-the-deficit.

- Farrell, H. and Quiggin, J., 2017. Consensus, dissensus, and economic ideas: economic crisis and the rise and fall of Keynesianism. International studies quarterly, 61 (2), 269–283. doi:10.1093/isq/sqx010.

- Flinders, M. and Buller, J., 2006. Depoliticisation: principles, tactics and tools. British politics, 1 (3), 293–318.

- George, A.L. and Bennett, A., 2005. Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. Cambridge Mass.: MIT Press.

- Hall, P.A., 1993. Policy paradigms, social-learning, and the state – the case of economic policy-making in Britain. Comparative politics, 25 (3), 275–296.

- Hay, C., 2007. Why we hate politics. Cambridge UK: Polity.

- Hay, C., 2014. Depoliticisation as process, governance as practice: what did the “first wave” get wrong and do we need a “second wave” to put it right? Policy & politics, 42 (2), 293–311. doi:10.1332/030557314X13959960668217.

- Helgadóttir, O. and Ban, C., 2021. Managing macroeconomic neoliberalism: capital and the resilience of the rational expectations assumption since the Great Recession. New political economy, 0 (0), 1–16. doi:10.1080/13563467.2020.1863344.

- HM Treasury, 1998. “Stability and investment for the long term”: economic and fiscal strategy report 1998.

- HM Treasury, 2008a. Pre-budget report.

- HM Treasury, 2008b. The government’s fiscal framework.

- HM Treasury, 2009. Budget 2009.

- HM Treasury, 2010. Budget 2010.

- HM Treasury, 2012. A new approach to financial regulation: securing stability, protecting consumers, a consultation.

- Hodson, D. and Mabbett, D., 2009. Uk economic policy and the global financial crisis: paradigm lost? Jcms: journal of common market studies, 47 (5), 1041–1061.

- Johnson, J., Arel-Bundock, V., and Portniaguine, V., 2019. Adding rooms onto a house we love: central banking after the global financial crisis. Public administration, 97 (3), 546–560. doi:10.1111/padm.12567.

- KFC, 2008. Review by the Governor of the Bank of Israel [Hebrew].

- KFC, 2009. The state and the Parliament’s preparation in response to the economic crisis [Hebrew].

- Madariaga, A., 2020. Neoliberal resilience. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/ebook/9780691201603/neoliberal-resilience.

- Magal-Shamir, O., 2021. Instruments of economic policy and the ideational power of economists in the civil service: the case of the “expenditure rule”. MA Thesis. University of Haifa.

- Maman, D. and Rosenhek, Z., 2011. The Israeli Central Bank: political economy, global logics and local actors. Oxon: Routledge.

- Mandelkern, R., 2015. What made economists so politically influential? Governance-related ideas and institutional entrepreneurship in the economic liberalisation of Israel and beyond. New political economy, 20 (6), 924–941. doi:10.1080/13563467.2014.999762.

- Mandelkern, R., 2019. Neoliberal ideas of government and the political empowerment of economists in advanced nation-states: the case of Israel. Socio-Economic review, doi:10.1093/ser/mwz029.

- Maron, A., 2021. Austerity beyond crisis: economists and the institution of austere social spending for at-risk children in Israel. Journal of social policy, 50 (1), 168–187. doi:10.1017/S004727942000001X.

- Matthijs, M. and Blyth, M., 2018. When is it rational to learn the wrong lessons? Technocratic authority, social learning, and Euro fragility. Perspectives on politics, 16 (1), 110–126. doi:10.1017/S1537592717002171.

- McCafferty, I., 2017. Twenty years of Bank of England independence: the evolution of monetary policy (speech given at the worshipful company of founders, city of London).

- McDaniel, S. and Berry, C., 2017. Macroeconomic policy change since the financial crisis: literature review. SPERI. Available from: http://speri.dept.shef.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Macroeconomic-policy-change-since-the-financial-crisis-literature-review.pdf.

- McPhilemy, S. and Moschella, M., 2019. Central banks under stress: reputation, accountability and regulatory coherence. Public administration, 97 (3), 489–498. doi:10.1111/padm.12606.

- Miró, J., 2021. Abolishing politics in the shadow of austerity? assessing the (de)politicization of budgetary policy in crisis-ridden Spain (2008–2015). Policy studies, 42 (1), 6–23. doi:10.1080/01442872.2019.1581162.

- MoF, 2009a. “Beliman Ve-Tenufa” – 2009–2010 economic policy for coping with the global economic crisis.

- MoF, 2009b. Review of developments in the Israeli economy, macroeconomic projections, budget framework and the global crisis.

- Moschella, M., 2015. Currency wars in the advanced world: resisting appreciation at a time of change in central banking monetary consensus. Review of international political economy, 22 (1), 134–161. doi:10.1080/09692290.2013.869242.

- Reisenbichler, A., 2020. The politics of quantitative easing and housing stimulus by the Federal Reserve and European Central Bank, 2008‒2018. West European politics, 43 (2), 464–484. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1612160.

- Stahl, R.M., 2020. From depoliticisation to dedemocratisation: revisiting the neoliberal turn in macroeconomics. New political economy, 1–16. doi:10.1080/13563467.2020.1788525.

- Streeck, W., 2014. Buying time: The delayed crisis of democratic capitalism. London: Verso.

- TSC, 2009a. Banking crisis; dealing with the failure of UK banks.

- TSC, 2009b. Report to treasury select committee from Dr Andrew Sentance, external member, monetary policy committee, November 17. Available from: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200910/cmselect/cmtreasy/34/34we03.htm.

- TSC, 2013. Report: budget 2013.

- Widmaier, W., 2016. The power of economic ideas – through, over and in – political time: the construction, conversion and crisis of the neoliberal order in the US and UK. Journal of European public policy, 23 (3), 338–356. doi:10.1080/13501763.2015.1115890.

- Wood, M. and Flinders, M., 2014. Rethinking depoliticisation: beyond the governmental. Policy & politics, 42 (2), 151–170. doi:10.1332/030557312X655909.

- Woodruff, D.M., 2016. Governing by panic: the politics of the eurozone crisis. Politics & society, 44 (1), 81–116. doi:10.1177/0032329215617465.

- Woodruff, D.M., 2019. To democratize finance, democratize central banking. Politics & society, 47 (4), 593–610. doi:10.1177/0032329219879275.