ABSTRACT

The extensive research on financialisation of housing and lively public and political debate on its negative implications for housing affordability have translated into surprisingly modest and fragmented policy responses. This reflects the power imbalance between the winners and losers from financialisation, but also the challenges inherent in taming financialisation due to its variegated, complex, and evolving nature and shortage of research on de-financialisation tools. To address this critical evidence gap, this article draws on the concept of financial circuits and comparative research on policy responses in the 56 United Nations Economic Commission for Europe member states. Comparing these policy responses with a four-part typology of the features of financial circuits which impact most on housing affordability reveals a pattern of uneven and inadequate action. Most governments have focused on controlling the scale of housing finance circuits, whereas limited action to control the number and cost of these circuits and practically no action to influence their focus has been taken. Some policy measures have reduced credit flows and thereby diminished house price growth, but their effectiveness has been undermined by countervailing policies and poor policy design, leading to inadequate targeting and implementation weaknesses.

Introduction

Enormous volumes of academic research on financialisation have been produced over the last decade, particularly from scholars working the fields of urban political economy, critical geography and sociology (Froud et al. Citation2000, Martin Citation2002, Krippner Citation2005, Arrighi Citation2009). Although underpinned by a variety of conceptualisations, analytical foci and understandings of impact, this research is united by a broad focus on the increased social, economic and political influence of finance and the finance industry across the globe and the consequences for structural transformation of economies, societies and households (Christophers Citation2015, Aalbers Citation2017, Bryan and Rafferty Citation2018). It demonstrates that the finance industry has gained more opportunities to generate ‘profit without producing’ goods or services and that finance activities have come to make up a growing share of total economic activity (Lapavitsas Citation2013). Consequently, governments, firms and households are increasingly constrained by financial obligations, leading to the subordination of the needs of their own voters, workers, or family members (Froud et al. Citation2000, Martin Citation2002, Krippner Citation2005, Arrighi Citation2009).

The implications of financialisation for housing and households is a central theme in this literature. Housing is the main absorber of the so called ‘wall of money’ generated by deregulated mortgage markets, the shadow banking sector and global capital markets and recirculated by the finance industry. Furthermore, housing is often the main collateral used to raise debt and thereby a crucial facilitator of financialisation (Fernandez and Aalbers Citation2016). Research on numerous countries has identified social, economic, and fiscal problems and risks generated by financialisation of housing, particularly for the stability of housing markets and housing affordability and access (André Citation2010, Kohl Citation2021, OECD Citation2021). This is because supply of land for housing is largely fixed and the supply of housing is generally inelastic (Ryan-Collins et al. Citation2017). In this context, excessive and unstrategic availability of credit for housing investment often drives price inflation, which in turn necessitates further borrowing to pay rising prices and over time generates housing unaffordability, credit bubbles and housing busts (Bezemer et al. Citation2018). Thus, a harmful ‘feedback cycle’ operates between housing and finance which undermines housing affordability (Ryan-Collins Citation2019).

Since the global financial crisis (GFC) and the government guarantees and bank bail outs which followed, policy makers have begun to devote increased attention to the impact of financialisation on housing market stability and housing affordability and access. Concerns been raised by civil society groups, local and national governments, and central bankers across the globe as well as by international organisations. For instance, a recent statement by the Governor of New Zealand’s Reserve Bank Adrian Orr (Citation2021) stresses the integral relationship between monetary policy and financial market regulation in the achievement of the right to adequate housing. These views echo statements by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing (Citation2020) who published guidelines on controlling financialisation to realise the right to adequate housing in 2020. While municipal governments in Barcelona have incorporated ‘Right to the City’ principles into their strategic policies (Grigolo Citation2019 ).

It is striking, however, that the huge volume of research and spirited public and political debate on financialisation have so far translated into only modest and fragmented policy responses (Wijburg Citation2020). This, of course, reflects enormous imbalance of power between the winners and losers from financialisation (Rolnik Citation2019). However, the variegated nature of financialisation, and the complexity of the ways in which this global process is mediated through national financial systems and local housing markets to generate different impacts, also means that devising and implementing effective policy responses is inherently challenging (Fernandez and Aalbers Citation2016). Municipal governments in the cities most negatively affected by financialisation of housing such as London, Barcelona, Copenhagen and Vancouver have attempted respond by regulating the use, renting and sale of housing in their operational areas (Fields and Uffer Citation2014, Beswick Citation2016, Edwards Citation2016, Van Heerden et al. Citation2020). The enormous scale and cross-national nature of the primary divers of financialisation means that the most effective responses are outside the remit and capacity of this level government.

Shortcomings in the research literature and a disconnect between research and policy, also make it difficult for governments to confidently design and implement effective responses. Although there a body of relevant policy reform proposals has begun to emerge from policy makers, regulators and non-governmental, organisations, much of this focused on individual countries and cities and published in national languages and not widely read internationally (European Action Coalition for the Right to Housing and to the City (Citation2019) and Schwan and Perucca (Citation2022) are exceptions). In addition, until recently, this policy discussion has been largely disconnected from the academic research on financialisation which has focused mainly on analysing its operation and devoted limited attention to potential solutions (Wijburg Citation2020). Christophers Citation2015 insight that financialisation research has focused on the details of developments in financial products and markets and financialisaton’s influence on housing markets, societies and governments, but neglected to examine how this influence is operationalised (i.e. to identify the ‘transmission mechanisms’ which link financialisation to its supposed socio-economic impact) may also help to explain this omission. The assumption implicit in much of the critical political economy literature that financialisation is an inherent feature of late-stage capitalism which government has limited capacity to manage may have contributed to academic researchers’ neglect of policy responses (Christophers Citation2015).

However, as Karwowski (Citation2019) among many others, points out that financial markets are in large part creations of government. Financial innovations such as REITs often require enabling legislation, for instance, and banks, bond markets and mortgage securitisation are underpinned by implicit or explicit government guarantees and government bond and mortgage purchases (Gotham Citation2006, Citation2009). Van Heerden et al.’s (Citation2020, p. 12) review of financialisation in European cities concludes that ‘policy plays an important role in the degree to which housing is, or can be, financialised’. This conclusion is supported by extensive case study research on individual countries and cities (e.g. Byrne Citation2016; Wijburg and Waldron Citation2020, Gil García and Martínez López Citation2021). If governments create and underpin financial markets and enable financialisation, this suggests in turn that they also have the power to shape these markets and disable financialisation.

To address these shortcomings in the research on policy responses to financialisation of housing, Wijburg (Citation2020) calls for more research on the ‘de-financialisation of housing’ and particularly on three key elements of this task: (i) financial market reforms aimed at dismantling finance-led housing accumulation; (ii) policy focused on strengthening the public and affordable housing sector; and (iii) changing modes of urban governance and social movements which can contest housing financialisation in different localities. A valuable research literature has recently begun to emerge in response to this call (e.g. Ryan-Collins Citation2019, Nethercote Citation2020, Wijburg and Waldron Citation2020, Wetzstein Citation2021) and this article is a further contribution to these efforts, albeit a partial one because we focus on the first two of the elements identified by Wijburg and particularly on the potential for employing financial instruments, policies and regulations as tools to tame financialisaton. Our choice of focus reflects the centrality of finance and financial instruments to financialisation and therefore of controls on finance to the process of de-financialisation. We give less attention non finance related de-financialisation tools which have been commonly proposed such as asserting the legal right to housing (Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing Citation2020) and concentrate on the financial tools required to realise this right in practice.

Our analysis draws on research conducted by the authors for the Housing2030 project which was commissioned United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), UN Habitat and Housing Europe (which represents social landlords in European) (Lawson et al. Citation2021) (see: Housing2030.org). Housing2030 aims to show how policy makers can shape markets to improve affordable housing outcomes. This geographically expansive project examined relevant land, finance, governance and regulatory policies in the 56 UNECE member countries (this encompasses all of Europe and North America and four countries in Central and Western Asia). Policy tools were identified using ‘crowdsourcing’ techniques via a survey of UNECE country housing focal points, and invitations to social landlords which are Housing Europe members, the members of specialist UNECE and UN Habitat committees on housing and the over 1200 attendees at the eight Housing2030 project webinars. An extensive review of published evaluative research on these policies were examined, data on implementation and outcomes collated and gaps in information were filled in via interviews with policy makers and written requests for information. On this basis, policies for which there was no robust evidence of effectiveness were excluded and effective policy responses to housing unaffordability were identified.

In searching for a suitable frame to make sense of this complex and fragmented policy landscape we build on Halbert and Attuyer’s (Citation2016, p. 1374) concept of circuits of finance, which they define as ‘sociotechnical systems that channel investments in the forms of equity and debt into urban production’ (see also: Sokol Citation2017). This is a well-established concept, which echoes the older theory of monetary circuits which is widely used in post-Keynesian economics (Lavoie Citation2014) and analyses employed in the literature on housing policy and social housing (Lawson Citation2013, Norris and Byrne Citation2021) and in the emerging literature on de-financialisation (Ryan-Collins Citation2019). More importantly, this concept has several critical benefits from the perspective of the analysis presented here. By identifying the features of financial circuits which most strongly influence housing markets and housing affordability, this concept enables us to address one of the key shortcomings in the literature on financialisation – the failure to clarify the transmission mechanisms which link financialisation to its (assumed) housing market impacts (Christophers Citation2015). These features then provide a focus for policy responses to financialisation identified and thereby a guide for the design and implementation, Halbert and Attuyer (Citation2016, p. 1374) also suggest that the concept of financial circuits enables us to go beyond ‘simplistic analytical distinctions’ between ‘public subsidies’ versus ‘private investments’, which are increasingly irrelevant to the way in which financialisation operates in practice and to scrutinise how the spatially varied operation of financial circuits shapes contrasting urban dynamics in different cities.

Despite promoting more widespread and systematic use of the concept of financial circuits Halbert and Attuyer (Citation2016) don’t conceptualise how these circuits perform in practice. To make this concrete, the next section reviews the literature on the contribution of finance to housing unaffordability and how this relationship materialises. On this basis, we clarify the conceptualisation of financial circuits which underpins our analysis and propose a typology of the features of these circuits have the strongest impact on housing affordability and therefore would priority targets of de-financialisaton measures. By definition these categorisations are ‘ideal types’ and the boundaries between them are not always clear-cut, but nevertheless they provide a useful frame to link causal financial processes to the design of policy responses and potentially provide benchmarks against which policy effectiveness can be assessed. The main body of the article then examines the ‘tools to tame’ each of these features of financial circuits which have been employed or proposed by policy makers in UNECE members states and reflects on their effectiveness in disrupting the relationship between financialisation and declining housing affordability. The conclusions outline the lessons which can be drawn from these experiences for the design and implementation of housing de-financialisation policies (Wijburg Citation2020).

Financialisation, financial circuits and housing unaffordability

As mentioned above, the analysis presented here is grounded in Halbert and Attuyer (Citation2016, p. 1374) conceptualisation of circuits of finance as ‘sociotechnical systems that channel investments in the forms of equity and debt’. We view these circuits as a product of regulation, which generate tendencies or causal chains which influence the forms and costs of housing provision and consumption. These causal chains are not isolated from social structures, rather they are embedded in them, (for example in existing property relations) and also operate in open increasingly global systems. Building on Lawson (Citation2013) we argue that circuits of finance may be stable and coherent for periods of time, as well as crisis prone and disruptive, leading to uneven flows of investment and disinvestment over space, time and asset category, sporadic development and even destruction of investment.

This literature points to several ways in which financialisation is linked by the mechanisms of financial circuits to unaffordable and inaccessible forms and costs of housing provision and consumption. Among these, the factor which has received most attention from researchers is the scale of financial circuits. Financialisation is associated with expansion in the total volume of finance and in the proportion of this which flows to housing markets (Aalbers Citation2008). This was particularly evident in financialisaton’s opening phase which was triggered by the banking and financial sector deregulation seen in most high-income, free market economies in the late-1970s and 1980s following the collapse of Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rate controls (Brenner Citation2006). While ‘mortgage rationing’ was widespread in the mid-twentieth century because building societies and banks had to accumulate sufficient customer deposits to fund new lending, banking deregulation in broke the link between deposits and lending by enabling banks to borrow from other banks and on capital markets to fund mortgages. The removal of credit guidance which required banks to allocate a proportion of lending to different sectors of the economy (e.g. industry, agriculture), the more widespread use of mechanisms such as securitisation to generate additional funds for lending and the abolition of controls on the movement of money across borders all contributed to an enormous ‘debt shift’, whereby financial flows to housing increased, while lending to the productive sectors of the economy declined, resulting in a parallel economic shift (Brenner Citation2006; Bezemer Citation2021). The opening of new markets in former communist Central and Eastern European and Southern European countries amplified these trends (Lunde and Whitehead Citation2016). The loosening of lending standards which often accompanied banking deregulation enabled the transmission of the spatially unbounded wall of money generated by this opening phase of financialisation into the housing market via mortgage lending (Arundel and Ronald Citation2021). Consequently, as had been documented by numerous authors, a credit-driven house price boom spread across most of the developed world in the late 1990s and early 2000s, which precipitated rising unaffordability and household indebtedness (Lawson Citation2004, Forrest and Hirayama Citation2015, Arundel and Doling Citation2017).

A second important and related feature is the number of financial circuits. Lunde and Whitehead's (Citation2016) review of milestones in European housing finance documents how the expanding volume of finance was accompanied by an increase in the number of circuits used to distribute it. This change also involved the loss of some circuits which are support housing affordability and access for low and middle-income households. In some (but by no means all) countries non-market finance for homeowner housing largely disappeared as governments withdrew from mortgage lending, as did non-profit lenders such as building societies (in the UK, Ireland and Australia) and savings and loans banks (in the USA) which traditionally provided most mortgages for average earners (Thomson and Abbott Citation1998, Barth et al. Citation2004). In addition, in many of the Western European and Anglophone countries where social housing provision was traditionally high, the sector began to shrink from the 1980s due to privatisation and reductions in the government subsidies and loans which supported new social house building (Harloe Citation1995, Malpass Citation2005). In contrast, many of the new financial circuits which emerged have undermined housing affordability and access. During the opening phase of financialisation, the number of bank lenders of mortgages increased, which, and generated hyper competition which drove new ‘financial product innovations’ such as equity withdrawal and buy-to-let investment mortgages (Lawson Citation2004, Norris and Coates Citation2014). Together with the advent of online accommodation platforms such as Airbnb, these developments provided additional financial circuits for extracting revenue from dwellings (Hoffman and Schimitter Heisler Citation2021).

A third key feature of financialisation is that the focus of financial circuits has shifted repeatedly, with the result that finance is more easily (and cheaply) available to some housing market actors, while others are excluded While financialisaton’s opening phase from the late-1970s was associated with a growth in bank lending to households for homeowner and buy-to-let mortgages for landlords, since the credit crunch and Global Financial Crisis in 2007–2008 a second phase of financialisation has emerged, which is characterised by increased non-bank lending and equity investment by institutions such as Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), student housing providers and built-to-rent landlords (Wijburg et al. Citation2018). The latter has enabled new patterns of financialised consumption which have squeezed the former out of housing markets, amplified house price rises, thereby driving severe affordability problems for average earners. Although financialisation is an inherently spatially uneven process, the housing unaffordability impacts of its latest phase have been particularly acute in economically vibrant cities, such as Barcelona, Berlin, Dublin, London and New York (Fernandez et al. Citation2016, Hunter Citation2016).

Cutting across the aforementioned developments are complex, constantly shifting and socio-economically and spatially differentiated changes in the cost of financial circuits which have had uneven impacts on housing affordability and access for different income groups and generations. Financial circuits are not ‘tenure neutral’ and the uneven public subsidisation and taxation of housing often unfairly penalises tenants and favours property owners (Adkins et al. Citation2021). While financialisation has been accompanied by falling or stagnating interest rates on mortgages for existing homeowners, the house price boom this precipitated has impeded access for aspirant homeowners. Furthermore, the decline in borrowing costs has not been universal as ‘sub-prime’ borrowers (with poor credit ratings) are charged a premium by the specialist lenders which have emerged to cater for this market (Aalbers Citation2008). Finance costs for institutional investors are much lower than for households (equity investors have no costs) and the tax treatment of institutions is generally more preferential and their market power greater. These variations in the costs of financial circuits explain why the latest, post-GFC phase of financialisation has seen households squeezed out of the housing markets in the booming cities where institutional investors are most active (Fields and Uffer Citation2014, Beswick et al. Citation2016).

Tools to tame the financialisation of housing

Tools to manage the scale of financial circuits

The GFC and the widespread housing booms which preceded it prompted governments and central banks in many UNECE member countries to take more concerted action to regulate the scale of financial circuits than has been seen for a generation. Many of the tools to manage demand for credit which were abolished during the 1970s and 1980s have since been reintroduced (see ).

Table 1. Credit guidance policy tools.

Unsurprisingly, actions to strengthen macroprudential regulation of banks (i.e. which protects the stability of whole financial system) have been particularly widespread. These regulations have been widely revised to force banks to maintain higher levels of reserve capital and reduce their leverage ratios they turn reducing the credit flowing into economies (Bezemer et al. Citation2018). Across the UNECE world region this has been achieved as part of the latest ‘Basel III’ round of the internationally agreed rules of banking supervision managed by the Bank of International Settlements (an international financial institution which aims to promote financial stability), which will be implemented from 2022. In some EU member states, additional rules on banks’ reserve capital requirements have been introduced as part of the establishment of a single supervisory mechanism for banks in the Eurozone (Nocera and Roma Citation2017).

As part of these processes, in many countries (including Australia, Canada, Finland, Ireland, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and the UK) mortgage lending has been regulated to limit credit availability, generally by imposing and/or changing the mortgage loan-to-value ratio and debt service-to-income ratio rules to which mortgage applicants must adhere. Access to interest only mortgages has also been limited or banned in some cases and amortisation of debt required. Several Asian countries (e.g. Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore) took similar action in the 1990s and early 2000s (Grace et al. Citation2015).

There is significant research evidence that, if appropriately designed, tightening of mortgage lending rules are effective in addressing household over indebtedness and, to a lesser extent, in dampening house price inflation (Kuttner and Shim Citation2016). However, these measures can also exclude some households from home purchase by creating ‘down payment’ and a ‘credit access’ barriers which some aspirant home buyers will not be able to overcome (Andrews and Caldera Sánchez Citation2011). Thus, to promote equity in housing access, stricter regulation of mortgage lending needs to be accompanied by measures to enable excluded householders’ access to affordable housing such as targeted grants, savings schemes and targeted deposit ratio reductions (OECD Citation2021).

However, the impact of the changes to mortgage lending rules on house prices has been limited by design and implementation weaknesses in some countries and by the impact of countervailing policies almost everywhere. In relation to the former, these reforms have often been too modest or short-term to significantly affect financial circuits. For instance, Dutch mortgage loan-to-value ratios were capped at 100 per cent, so down payments are still not required (Grace et al. Citation2015). In 2020, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority reigned in mortgage lending but withdrew these measures when they proved effective in dampening houses prices and later reminded the government that financial stability and ‘not cooling house prices’ is its remit (Frost Citation2021, p. 1).

As discussed later in this article, mortgage interest tax relief (MITR) was traditionally the most widespread countervailing policy measure and, combined with the non-taxation of capital gains on homeowner housing, plays a significant role in maintaining the expanded scale of housing finance circuits and house price growth (Kuttner and Shim Citation2016). Furthermore, since the GFC macroeconomic policy has come to be a very important countervailing factor. IMF research demonstrates that macroeconomic policies have become ineffective in managing boom–bust cycles in European housing markets (Arena et al. Citation2020 ). Indeed, many economists argue that the ultra-low-interest rates which followed quantitative easing have magnified real estate booms (Ryan-Collins Citation2019). These concerns have inspired much debate among policy makers and increasingly central bankers. For instance, the United Nations Environment Programme (Citation2015) inquiry into how the financial system can contribute to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals recommends that housing market stability should be integrated into central banks’ financial stability reviews. However, to date, only New Zealand has taken policy action in response. In March 2021 its government directed central bank it to consider ‘the Government’s objective to support more sustainable house prices, including by dampening investor demand for existing housing stock to help improve affordability for first-home buyers’ in ‘carrying out its financial policy functions’ (Orr Citation2021, p. 13). This direction attracted some criticism (e.g. Wolf Citation2021) and at the time of writing no concrete examples of its impact on the New Zealand central bank’s functions have been published.

Even where they have been implemented, the impact of traditional central bank interventions to regulate banks and set interest rates is likely to be weaker now than it was the twentieth century, because banks (and other traditional mortgage lenders such as building societies) are no longer the primary providers of private finance for housing. In view of the increasing importance of non-bank finance (from private equity investors, pension funds, REITs and other private investment vehicles) in housing markets, there is a risk that this focus on regulating bank is a case of ‘fighting the last war’, while not preparing adequately for the next likely attack on housing market stability and addressing the most significant drivers of house price inflation.

The first step in addressing risks is, of course, recognising their existence and in the aftermath of the post-GFC bank bail outs, the growth in non-bank finance was not generally recognised as a risk by orthodox economists and central bankers. Rather in Ireland it was welcomed as a way of diversifying real estate finance away from domestic banks and thereby de-risking them (Daly et al. Citation2021). However, this has recently begun to change (Grace et al. Citation2015). A recent Central Bank of Ireland study on investment fund activities in the Irish office and retail property markets highlights the limited tools currently available to regulators to manage this activity and argues that ‘a comprehensive macroprudential framework’ should include such tools (Daly et al. Citation2021). In the UNECE member states, the authors identified no policies or regulations actually introduced in response to these concerns, but we did find one example of policy non implementation. When REITs were legalised in Germany in 2007, policy makers confined their activities to commercial property investment due to concerns that their residential property investment would drive rent increases (Fritsch et al. Citation2013).

Tools to manage the focus of financial circuits

As mentioned above, prior to banking deregulation in the 1970s and 1980s governments of high-income countries actively directed the focus of financial circuits using credit guidance tools (Brenner Citation2006, Fuller Citation2015). Furthermore, in many countries, banks were effectively excluded from mortgage lending, which was dominated by non-profit lenders such as building societies (Lunde and Whitehead Citation2016) (see ). The removal of credit guidance was formally justified by economists’ concerns about its role in undermining banking competition and the inability of government to direct the allocation of capital efficiently (Goodhart Citation1989, Alexander et al. Citation1995). Although the decline of opportunities for bank lending and profit making, as services replaced manufacturing industry in Western economies, was no doubt also influential (Brenner Citation2006).

In retrospect, of course, these concerns about capital misallocation appear specious. The removal of credit guidance played a key role in the aforementioned ‘debt shift’ evident from the early 1980s, which contributed to credit-fuelled housing market bubbles and ultimately to the GFC as well as to aforementioned economic imbalances and social problems associated with financialisation (Bezemer and Zhang Citation2019).

Crucially, Bezemer's (Citation2018) analysis of the banking regulations introduced in response to the GFC and earlier credit bubbles indicates that they had a minimal impact on the focus of bank lending which remained concentrated in real estate between 2000 and 2013. Since the latter date some additional regulations have been introduced to redirect credit away from real estate in UNECE members. These include higher risk weights for mortgages and lower risk weights for lending to SMEs and infrastructure projects under the Basel III rules and the European Central Bank’s longer-term refinancing operations programme which provides Eurozone banks with four years of subsidised refinancing for loans made to non-financial corporations and households for consumption (but notably not for house purchase). However, no robust evidence is yet available on their impact, not it is certain they will remain in place because in some cases these measures were introduced as emergency responses to the GFC or the Covid 19 pandemic (Bezemer et al. Citation2021).

Parallel to these efforts to rebalance the macro level focus of debt finance away from housing investment, policy makers have begun to acknowledge the need to refocus lending for housing to promote, rather than impede, affordability and access. The 2015 United Nations Environment Programme inquiry into the financial system includes recommendations intended to refocus some commercial finance towards affordable and sustainable housing and highlights the need to ensure that public spending on housing and procurement processes promote more sustainable housing outcomes (see ). The latter echoes the ideas on ‘purposeful public investment’ proposed in Mariana Mazzucato’s Citation2013 book The Entrepreneurial State. They also complement the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing’s (Citation2020) guidelines on realising the right to adequate housing. For instance, Guideline Number 12 recommends regulating commercial investment in housing to prevent any negative impacts on the right to housing and using taxes to discourage residential real estate and land speculation and vacancy.

Table 2. United Nations Environment Programme’s tools for a more sustainable and inclusive finance system.

Some of these proposals for refocusing circuits of housing finance have been implemented by UNECE member states, but too recently to inform robust analysis of their effectiveness. For instance, to discourage short term speculation in housing (popularly known as ‘flipping’), from 2021 the New Zealand government increased the period for which residential property investors must hold onto dwellings in order to secure exemption from capital gains tax (AHURI Citation2021). Denmark introduced legislation in 2020 to limit the opportunities for property investors to claim an exemption from rent controls by renovating older dwellings because policy makers were concerned that abuse of this provision was driving up rents (Bonde-Hansen Citation2021). Similarly, in 2021 the government of British Columbia (Citation2021) in Canada amended local legislation to discourage ‘renovictions’ (the eviction of private renting tenants on the grounds of the renovation of the dwelling).

Tools to manage the number of financial circuits

As mentioned above, the expansion in the number of financial circuits which enable value extraction from housing (and thereby often raise it price), coupled with the contraction of non-profit financial circuits such as building societies and public banks and of circuits which support social and affordable housing provision (which reduces is availability) are key transmission mechanisms which link financialisation to housing unaffordability. This suggests that policy action to support, revive or create of circuits of finance that serve the right to adequate to housing and to inhibit or prevent processes of value extraction from housing can promote de-financialisation (Lawson Citation2013, Matznetter Citation2020).

However, in the UNECE member states policy action to limit value extraction from housing has been strikingly limited to date. The action which has been initiated has focused on online platforms for short-term accommodation letting such as Airbnb. Crommelin’s (Citation2018) review of responses taken by eleven cities identified three approaches:

Permissive regimes which enable short-term letting (e.g. London, Phoenix, Melbourne and Sydney).

Notification systems (e.g. Amsterdam and Paris) which regulate and restrict the short-term letting.

Prohibitive regimes which prevent short-term letting (e.g. Barcelona, Berlin, New York and Hong Kong).

Policy action to provide circuits of finance that support the right to adequate to housing has been more extensive but also spatially uneven. This has focused largely (but not entirely) on the revival of the non-profit financial circuits which were used for this purpose for much of the twentieth century (and remained in use in several Western European countries despite the trend for their abolition in the Anglophone world) (Mundt and Springler Citation2016, Tutin and Vorms Citation2016).

For instance, although government capital spending on social housing provision remains well below the levels seen in the mid-twentieth century in most high-income countries this form of investment has seen a revival in some places (OECD Citation2021). The Irish government’s special purpose financial intermediary (SPFI – essentially a small, specific purpose public bank) the Housing Finance Agency has quadrupled its lending for social housing provision and mortgages for low-income homebuyers in recent years. A similar SPFI called the National Housing Finance Investment Corporation was established by the Australian government in 2018 to raise debt to fund social housing and mortgages for low-earners. Although public banks were commonly privatised in English-speaking countries during the 1980s, they have remained in operation and active in funding social and affordable housing in many European countries. The European Association of Public Banking currently has 30 members in 18 EEA countries and their assets account for 15 per cent of the total financial sector in this world region (see: https://eapb.eu/). Pan European public banks including the European Investment Bank and the Council of Europe Development Bank (respectively the banks of the Europe Union and the Council of Europe) have significantly increased their lending for social housing, mortgages for low earners and housing retrofit in recent years. Governments also lend directly for social housing provision in several European countries, including Austria, Denmark, Finland and Slovakia.

Although non-profit savings banks have largely disappeared in English-speaking countries and Spain (where most ‘cajas’ were absorbed into banks following the GFC), these instructions continue to provide a large proportion of mortgages in Germany and Austria (where they are called bausparkassen) (Lunde and Whitehead Citation2016). Furthermore, the bausparkassen model was introduced in Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Kazakhstan, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia during their transition from communism and has proved an effective means of increasing mortgage provision when the commercial banking sector remains underdeveloped (Hegedüs et al. Citation2017, UNECE Citation2018).

All non-profit financial circuits contribute to de-financialisation by funding affordable mortgages, home renovation loans and social housing provision outside the market. However, the research conducted by the authors on UNECE member states identified certain types of non-profit circuits which have particularly strong de-financialising impacts. These circuits have one or both of the following design features:

‘closed circuits of finance’ which are separate and protected from market imperatives and fluctuations in government funding, and/or

‘revolving fund’ design whereby loans are granted and when they are repaid this money is lent out again and thereby self-replenish (Gibb et al. Citation2013).

The Bausparkassen which emerged in Germany and Austria the in late nineteenth century provide a closed circuit of finance for mortgages for low earners and for social housing. They operate ‘contract savings schemes’ which provide fixed, below-market rates on savings and subsequently on the mortgage loans which are granted when savings have reached a certain level and duration and also finance social housing. These are particularly effective de-financialising measures because, in addition to financing housing for those excluded from the market, they insulate customers from financial market volatility. Norris and Byrne’s (Citation2018) research on Austria indicates they also supported counter cyclical investment in housing when bank and government finance was restricted after the GFC.

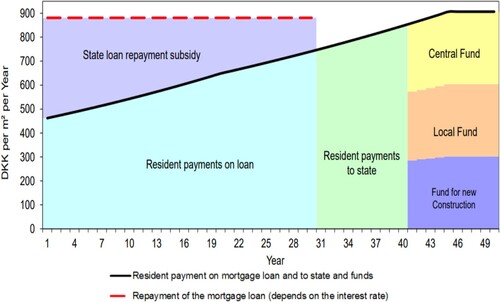

Particularly, when lending for social housing, many public and non-profit lending arrangements operate as revolving funds, although the format and scale of these arrangements varies significantly between countries. Slovakia established a national revolving fund called the State Housing Development Fund in 1996 to finance social housing and renovation of private housing. It was originally financed exclusively from the state budget, but it has become largely (but not entirely) self-sustaining over time (Hegedüs et al. Citation2017). Individual social housing providers commonly operate de facto internal revolving funds by reinvesting any surpluses into house building or renovation of course, but in Austria this arrangement is underpinned by legislation which requires this reinvestment and subsidises social landlords for doing so (Deutsch and Lawson Citation2012). Going one step further, in Denmark the surpluses of individual social housing providers are recycled for collective use. After social housing development loans have been repaid by tenants’ rents, ongoing rent revenue is pooled centrally to repay government subsidies for a 10-year period and after that paid into a central fund called the Landsbyggefonden (National Building Foundation) which funds new social house building and renovation (see ).

Despite their rather elementary design, there is significant evidence that revolving funds are particularly effective tools for funding social housing (Gibb et al. Citation2013). They provide a reliable, ring fenced, stream of capital for housing provision and renovation and, by retaining the value of historic public subsidies in the social housing sector and re-recycling this funding, reduce the need for governments to constantly provide new capital (although rarely eliminate this need entirely). The practical benefits of this model are evident in Slovakia which, uniquely among the former communist Central and Eastern European countries, has significantly expanded social housing output since the mid-1990s using revolving fund finance (Hegedüs et al. Citation2017). Revolving funds are also effective de-financialisation tools because they insulated from fluctuations in the availability of exchequer funding and commercial lending for housing provision. Norris and Byrne’s (Citation2021) research on the Danish social housing sector argues its revolving fund enabled counter cyclical investment after the GFC.

However, preserving the revolving fund model over the long-term has proved challenging in the face of ideologically inspired pressures to roll back social housing provision and baser temptations to ‘raid the chest’ of historic subsidies preserved in this system to fund other spending priorities. In Austria, increased social housing privatisations in recent years may undermine its social landlord level revolving fund arrangements (Norris and Byrne Citation2018). Gibb et al. (Citation2013) also suggest that the Danish government has drawn too heavily on its revolving fund in recent years to reduce exchequer subsidies for social housing, which may the fund’s adequacy.

Not all of the recent efforts to expand fund social and affordable housing in UNECE member states has focused on the revival of traditional non-profit financing circuits. Reduced public funding has promoted social landlords in some countries to make increased use of new financial circuits.

Some of these are financialised in nature and social landlords in England and the Netherlands have been particularly active users of new complex sources of market finance such as derivatives and index-linked lease arrangements (Wainwright and Manville Citation2016, Regulator of Social Housing Citation2018). However, there is strong evidence that the value extraction which these circuits enable undermines social landlords’ social mission, because they have to increase rents and engage in commercial housing development to service the higher financing costs (Morrison Citation2016). Reliance on financialised funding instruments also brings market risk, which came to pass in the Netherlands in 2011 when the Vestia social landlord required a €2bn ‘bail out’ a result of gambling with derivatives (Aalbers Citation2017).

However, not all of the new circuits of finance for social and affordable housing promote financialisation. There is enormous interest in the potential to reorientate capital flows towards a more sustainable economy via ESG investing (which incorporates environmental, social and governance criteria into investment decisions) and more specialist vehicles such as social impact investing (which aim to achieve a measurable positive impact) (see European Commission Citation2018). The research on the UNECE member countries identified numerous examples of the use of specialist bonds and investment funds to raise finance for social and affordable housing. For instance, in 2017 the Council of Europe Development Bank issued a Social Inclusion Bond which to date has funded the construction and renovation of 10,600 dwellings for low-income households. The global housing charity Habitat for Humanity (Citation2019) launched the Microbuild Fund in 2012 to enable social investors fund microfinance for housing renovations in 31 low-income countries. Examples of social impact investing in housing are far less common. The Dutch public investment bank Nederlandse Waterschapsbank N.V is one of few exceptions identified by the authors. In 2017 it created affordable housing bonds to fund loans for social housing provision and renovation and worked with the representative body for Dutch social housing landlords to devise meaningful social impact reporting mechanisms for these loans.

The paucity of examples of public impact investing in housing, points to a key problem with ESG financial instruments – the lack of measurable and verifiable environmental, social and governance outcomes for bond proceeds, leading to accusations that they don’t achieve their objectives or, even worse, convey a misleadingly positive impression of investor standards (also known as ‘greenwashing’ or ‘social washing’). Greenwashing is the subject of lively public debate and action to address it has been initiated. For instance, in 2018 the European Commission published an Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth and associated taxonomy of green investment activities and standards for regulating these. However, to date, little action has been taken to regulate ESG investing in social and affordable housing. An exception is the industry standards devised by the Housing Finance Corporation (the English statutory special purpose financial intermediary for social housing) which aligns investment criteria to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and international accounting standards.

Tools to manage the cost of financial circuits

Many of the aforementioned measures to establish new and expand existing circuits of finance for social and affordable housing also include features which reduce the cost of this finance. Governments commonly use grants, interest rate subsidies and regulation of social housing landlords (which reduce interest rates by assuring lenders of their solvency) to further reduce costs (Gibb et al. Citation2013). Less commonly, government guarantees (used in the USA, UK and Switzerland) and guarantee funds (e.g. the Dutch Waarborgfonds Sociale Woningbouw, which repay loans in the event of default) are employed for this purpose (Lawson Citation2018). Tax exemption of social housing landlords (which are almost always non-profit organisations) is also an important subsidy.

However, many other subsidies to reduce the cost of housing finance have accelerated financialisation and also housing inequality. The taxation of housing production, use, value and exchange merits particular attention because it strongly influences the origin, scale, and flow of investment into housing and the rates of return that can be generated. Taxes may favour different housing tenures and housing provision models (e.g. large-scale commercial landlords or small-scale ‘amateur’ landlords) and thereby privilege the generations or social classes who most often occupy or own these types of housing. Consequently, taxation can accelerate financialisation and or, if purposefully designed, can be a key de-financialisation tool (Wijburg Citation2020).

Revenue foregone from MITR costs the Dutch government €32 billion per year, and this expenditure quadrupled between 1990 and 2014 (Krapp Citation2020). This has attracted increasing criticism because it promotes household indebtedness and primarily benefits mortgage lenders, not home buyers, because its value is capitalised into house prices (Vangeel et al. Citation2021). In Ireland, the radical growth in purchases of residential property by international investment firms and REITs since the GFC has proved very politically contentious, due to concerns that it is inflating house prices and displacing aspirant home buyers and about the low taxation and excessive market power of these institutions (Waldron Citation2018).

Despite the prevalence of these concerns, the research on UNECE member states identified only patchy policy responses. Among these efforts, abolition, or reduction of MITR for homeowners has been employed most often. In the UK, Belgium, Ireland and Australia, MITR has been withdrawn or significantly reduced and it has been reduced more modestly in Estonia, the Netherlands, Finland and Slovakia (Krapp Citation2020). Several countries have also introduced tax measures to deter speculation in housing. An example is New Zealand’s Bright Line policy, which applies capital gains tax on properties sold within 10 years of purchase. Less commonly tax loopholes which favour corporate investors in housing over amateur landlords and homeowners have been closed. For instance, to stem real estate transfer tax avoidance, Germany has recently required that this tax is levied if at least 90 per cent of the shares in a real estate owning corporation change hands, directly or indirectly, within a rolling 10-year time frame. Irish tax reforms clamped down on aggressive tax avoidance by institutional property investors – and increased their effective tax rate from 2.7 per cent in 2019–17.9 per cent in 2020 (Reddan Citation2021).

Conclusions

The voluminous research on financialisation of housing and lively public and political debate on its negative implications for housing affordability has translated into relatively modest and fragmented policy responses. This reflects the power imbalance between the winners and losers from financialisation of housing, but also the challenges inherent in taming financialisation due to its variegated, complex and evolving nature and the shortage of research on the de-financialisation tools which have actually and could potentially be employed by governments (Wijburg Citation2020). This situation has recently begun to change. Concerned by the impact of the GFC and the fact that middle class home buyers are no longer among the winners from financialisation but are increasingly squeezed out of urban housing markets by large investors, policy makers have started debating how to tame financialisation and a research literature on de-financialisation is emerging. This article has endeavoured to contribute to this emergent literature and policy debate by finessing and extending the well-established concept of circuits of finance for housing and examining policy responses to financialisation in the 56 UNECE member states.

Comparing the four-part typology of the features of circuits of housing finance which are most significant from the perspective of housing affordability, with the policies initiated in response by UNECE governments, reveals a pattern of uneven policy action. Most action has focused on controlling (in practice reducing) the scale of housing finance circuits; policy makers have taken more limited action to control the number and cost of these circuits and practically no action to influence their focus.

Some of the measures taken have achieved their stated objectives – regulations to control unsustainable debt by imposing mortgage loan-to-value and loan-to-income ratios are examples. However, these regulations have been less effective in controlling rising house prices and may also impede low earners’ access to home ownership (Andrews and Caldera Sánchez Citation2011, Kuttner and Shim Citation2016). Furthermore, the effectiveness of these and many other de-financialisation measures introduced by UNECE members has been undermined by strategic design and targeting problems, implementation weaknesses and the impact of countervailing policies. For instance, efforts to control the scale of housing finance circuits have to date focused almost entirely on bank regulation and only modest action has been taken to address the growing role which shadow banks, REITs and investment funds play in driving financialisation. The mortgage regulations introduced in some countries have been too modest, or short-lived to have a significant impact. Furthermore, in many countries their impact has been reduced by countervailing policies most notably Mortgage Interest Tax Relief and quantitative easing.

Although the analysis presented in this article is exploratory, it does illuminate the key issues which should be included de-financialisation strategy and merit further research. It highlights the need for comprehensive policy action across all four of the circuits of finance identified here and also targeting all types of financial instruments including the novel, but increasingly significant secondary lenders as traditional sources such as banks and including all levels of government – local, national and international. It identifies the benefits of reviving or establishing circuits of finance that support social and affordable provision but demonstrates the need for accompanying action to inhibit or prevent processes of value extraction from housing using taxation and regulation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michelle Norris

Michelle Norris is a professor of social policy and director of the Geary Institute for Public Policy at University College Dublin. Her work focuses on financialisation of housing and the political economy of social housing in Western Europe.

Julie Lawson

Julie Lawson is an honorary associate professor based in Europe at the Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University Australia. Her work focuses on comparing housing systems and their constituent property, finance and welfare arrangements influencing housing outcomes

References

- Aalbers, M.B., 2008. The financialization of home and the mortgage market crisis. Competition and change, 12 (2), 148–166.

- Aalbers, M.B., 2017. The variegated financialization of housing. International journal of urban and regional research, 41 (4), 542–554.

- Adkins, L., Cooper, M., and Konings, M., 2021. Class in the 21st century: asset inflation and the new logic of inequality. Environment and planning a: economy and space, 53 (3), 548–572.

- AHURI, 2021. AHURI brief: New Zealand housing investment tax changes explained. Melbourne: AHURI.

- Alexander, W., Enoch, M., and Balino, T., 1995. The adoption of indirect instruments of monetary policy. Occasional Paper No. 126. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- André, C., 2010. A bird’s eye view of OECD housing markets. Paris: OECD.

- Andrews, D., and Caldera Sánchez, A., 2011. The evolution of homeownership rates in selected OECD countries: demographic and public policy influences. Paris: OECD.

- Arena, M, et al., 2020. Macroprudential Policies and House Prices in Europe. New York: IMF.

- Arrighi, G., 2009. The long twentieth century: money, power and the origins of our time. London: Verso.

- Arundel, R., and Doling, J., 2017. The end of mass homeownership? Changes in labour markets and housing tenure opportunities across Europe. Journal of housing and the built environment, 32 (4), 649–672.

- Arundel, R., and Ronald, R., 2021. The false promise of homeownership: homeowner societies in an era of declining access and rising inequality. Urban studies, 58 (6), 1120–1140.

- Barth J.R., Trimbath S., Yago G., eds., 2004. The savings and loan crisis: lessons from a regulatory failure. Boston MA: Springer.

- Beswick, J., et al., 2016. ‘Speculating on London’s housing future: the rise of global corporate landlords in “post-crisis” urban landscapes’. City, 20 (2), 321–341.

- Bezemer, D., et al., 2018. Credit where it’s due: a historical, theoretical, and empirical review of credit guidance policies in the 20th century. London: UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose.

- Bezemer, D., et al., 2021. ‘Credit policy and the ‘debt shift’ in advanced economies. Socio-economic review, 2021, doi:10.1093/ser/mwab041.

- Bezemer, D., and Zhang, L., 2019. Credit composition and the severity of post-crisis recessions. Journal of financial stability, 42 (1), 52–66.

- Bonde-Hansen, M., 2021. The dynamics of rent gap formation in Copenhagen: an empirical look into international investments in the rental market. Malmö: Malmö University.

- Brenner, R., 2006. The economics of global turbulence. London: Verso.

- British Columbia, 2021. Residential Tenancy Policy Guideline 2B: ending a tenancy to demolish, renovate, or convert a rental unit to a permitted Use. Victoria: Government of British Columbia.

- Bryan, D., and Rafferty, M., 2018. Risking together: how finance is dominating everyday life in Australia. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

- Byrne, M., 2016. ‘Entrepreneurial urbanism after the crisis: Ireland’s “Bad bank” and the redevelopment of Dublin’s Docklands’. Antipode, 48 (4), 899–918.

- Christophers, B., 2015. The limits to financialization. Dialogues in human geography, 5 (2), 183–200.

- Crommelin, L., et al., 2018. Technological disruption in private housing markets: the case of Airbnb. Melbourne: AHURI Final Report 305.

- Daly, P., Moloney, K., and Myers, S., 2021. Property funds and the Irish commercial real estate market, financial stability notes. Dublin: Central Bank of Ireland.

- Deutsch, E., and Lawson, J., 2012. International measures to channel investment towards affordable housing. Melbourne: AHURI, commissioned by Department of Housing, WA Government.

- Edwards, M., 2016. The housing crisis and London. City, 20 (2), 222–237.

- European Action Coalition for the Right to Housing and to the City, 2019. Housing financialization trends, actors and processes. Brussels: ESCRH.

- European Commission, 2018. Action plan: financing sustainable growth. Brussels: European Commission.

- Fernandez, R., and Aalbers, M., 2016. Financialization and housing: between globalization and varieties of capitalism. Competition and change, 20 (2), 71–88.

- Fernandez, R., Hofman, A., and Aalbers, M., 2016. London and New York as a safe deposit box for the transnational wealth elite. Environment and planning A, 48 (12), 2443–2461.

- Fields, D., and Uffer, S., 2014. The financialization of rental housing: a comparative analysis of New York City and Berlin. Urban studies, 53 (7), 1486–1502.

- Forrest, R., and Hirayama, Y., 2015. The financialization of the social project: embedded liberalism, neoliberalism and home ownership. Urban studies, 52 (2), 233–244.

- Fritsch, N., Prebble, J., and Prebble, R., 2013. A comparison of selected features of real estate investment trust regimes in the United States, the United Kingdom and Germany. Victoria: Victoria University of Wellington Legal Research Paper No. 14/2013.

- Frost, D., 2021. Managing hot house prices ‘not our job’: APRA. Australian financial review, 5–8. https://www.afr.com/companies/financial-services/hot-house-prices-not-our-job-apra-20210329-p57et9

- Froud, J., Haslam, C., and Johal, C., 2000. Shareholder value and financialization: consultancy promises, management moves. Economy and society, 29 (1), 80–110.

- Fuller, G.W., 2015. ‘Who’s borrowing? Credit encouragement vs. credit mitigation in national financial systems’. Politics & society, 43 (2), 241–268.

- Gibb, K., Maclennan, D., and Stephens, M., 2013. Innovative financing of affordable housing: international and UK perspectives. York: Joseph Rowntree Trust.

- Gil García, J., and Martínez López, M., 2021. State-led actions reigniting the financialization of housing in Spain. Housing, theory and society, doi:10.1080/14036096.2021.2013316.

- Goodhart, C., 1989. Money, information and uncertainty. London: Macmillan.

- Gotham, K., 2006. The secondary circuit of capital reconsidered: globalization and the U.S. real estate sector. American journal of sociology, 112 (1), 231–75.

- Gotham, K., 2009. Creating liquidity out of spatial fixity: the secondary circuit of capital and the subprime mortgage crisis. International journal of urban and regional research, 33 (2), 355–71.

- Grace, T., Hallissey, N., and Woods, M., 2015. The instruments of macro-prudential policy. Central bank of Ireland quarterly bulletin, 65 (1), 90–105.

- Grigolo, M, 2019. The Human Rights. New York: Routledge.

- Habitat for Humanity, 2019. Microbuild fund: annual report FY2019. Washington: Habitat for Humanity.

- Halbert, L., and Attuyer, K., 2016. Introduction: the financialization of urban production: conditions, mediations and transformations. Urban studies, 53 (7), 1347–1361.

- Harloe, M., 1995. The people’s home? Social rented housing in Europe and America. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Hegedüs, J., Horváth, V., and Somogyi, E., 2017. Affordable housing in central and Eastern Europe: identifying and overcoming constrains in new member states. Budapest: Metropolitan Research Institute.

- Hoffman, L., and Schimitter Heisler, B., 2021. Airbnb, short-term rentals, and the future of housing. New York: Routledge.

- Hunter, P., 2016. The englishman’s castle and the impact of foreign investment in residential property. In: M Raco, ed. Britain for sale? Perspectives on the cost and benefits of foreign ownership. London: The Smith Institute, 41–50.

- Karwowski, E., 2019. Towards (de)financialisation: the role of the state. Cambridge journal of economics, 43 (4), 1001–1027.

- Kohl, S., 2021. Too much mortgage debt? The effect of housing financialization on housing supply and residential capital formation. Socio-economic review, 19 (2), 413–440.

- Krapp, M.-C., et al., 2020. Housing policies in the European union. Darmstadt: Institute for Housing and Environment and Institute of Political Science, Technical University.

- Krippner, G., 2005. The financialization of the American economy. Socio-economic review, 3 (1), 173–208.

- Kuttner, K., and Shim, I., 2016. Can non-interest rate policies stabilize housing markets? Evidence from a panel of 57 economies. Journal of financial stability, 26 (1), 31–44.

- Lapavitsas, C., 2013. The financialization of capitalism: “profiting without producing”. City, 17 (6), 792–805.

- Lavoie, M., 2014. Post-Keynesian economics: new foundations. Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- Lawson, J., 2004. Home ownership and the risk society - marginality and home purchase in the Netherlands. Utrecht: Ministry of Housing of the Netherlands and NETHUR.

- Lawson, J., 2013. Critical realism and housing research. London: Routledge.

- Lawson, J., et al., 2018. Social housing as infrastructure – an investment pathway. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

- Lawson, J., Norris, M., and Wallberg, H., 2021. Housing2030: effective policies to deliver affordable housing. Geneva: United Nations.

- Lévy-Vroelant, C., Schaefer, J.P., and Tutin, C., 2014. Social housing in France. In: K. Scanlon, C. Whitehead, and M Arrigoitia Fernández, eds. Social housing in Europe. London: Wiley Blackwell, 124–142.

- Lunde, J. and Whitehead, C, eds., 2016. Milestones in European housing finance, Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

- Malpass, P., 2005. Housing and the welfare state: the development of housing policy in Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Martin, R., 2002. Financialization of daily life. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Matznetter, W., 2020. How and where non-profit rental markets survive – a reply to Stephens. Housing, theory and society, 37 (5), 562–566.

- Mazzucato, M., 2013. The entrepreneurial state: debunking public vs. private sector myths. London: Anthem Publishing.

- Morrison, N., 2016. Institutional logics and organisational hybridity: English housing associations’ diversification into the private rented sector. Housing studies, 31 (8), 1–19.

- Mundt, A., and Springler, E., 2016. Milestones in housing finance in Austria over the last 25 years. In: J. Lunde, and C Whitehead, eds. Milestones in European housing finance. London: Wiley, 55–71.

- Nethercote, M., 2020. Build-to-Rent and the financialization of rental housing: future research directions. Housing studies, 35 (5), 839–874.

- Nocera, A., and Roma, M., 2017. House prices and monetary policy in the euro area: evidence from structural VARs. Frankfurt: ECB.

- Norris, M., and Byrne, M., 2018. Housing market (in)stability and social rented housing: comparing Austria and Ireland during the global financial crisis. Journal of housing and the built environment, 33 (2), 227–245.

- Norris, M., and Byrne, M., 2021. Funding resilient and fragile social housing systems in Ireland and Denmark. Housing studies, 36 (9), 1469–1489.

- Norris, M., and Coates, D., 2014. How housing killed the Celtic tiger: anatomy and consequences of Ireland's housing boom and bust. Journal of housing and the built environment, 29 (2), 299–315.

- OECD, 2021. Brick by brick: building better housing policies. Paris: OECD.

- Orr, A., 2021. Some policy lessons from a year of COVID-19: a speech delivered by Adrian Orr Governor, New Zealand Federal Reserve. Aukland: New Zealand Economics Forum.

- Reddan, F., 2021. Tax take from institutional property investors rose by 171% in 2020 move by revenue saw effective tax rate levied increase from 2.7% in 2019 to 17.9% in 2020. Irish times, 17. 12 May.

- Regulator of Social Housing, 2018. Lease-based providers of specialised supported housing. In: Regulator of social housing's 2018 sector risk profile. London: HMSO. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/lease-based-providers-of-specialist-supported-housing.

- Rolnik, R., 2019. Urban warfare: housing under the empire of finance. London: Verso.

- Ryan-Collins, J., 2019. Breaking the housing–finance cycle: macroeconomic policy reforms for more affordable homes. Environment and planning A: economy and space, 53 (3), 480–502.

- Ryan-Collins, J., Loyd, T., and Macfarlane, L., 2017. Rethinking the economics of land and housing. London: Zed Books.

- Schwan, K., and Perucca, K., 2022. Realising the right to housing in Canadian municipalities. Vancover: the Shift.

- Sokol, M., 2017. Financialisation, financial chains and uneven geographical development: towards a research agenda. Research in international business and finance, 39 (1), 678–685.

- Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing, 2020. Guidelines for the implementation of the right to adequate housing. Geneva: United Nations.

- Thomson, J., and Abbott, M., 1998. The life and death of the Australian permanent building societies. Accounting, business & financial history, 8 (1), 73–103.

- Tutin, C., and Vorms, B., 2016. 10 milestones of housing finance in France between 1988 and 2014: is the French credit system a Gallic Oddity? In: J. Lunde, and C Whitehead, eds. Milestones in European housing finance. London: Wiley, 165–181.

- UNECE, 2018. Country profiles on the housing sector: republic of Kazakhstan. Geneva: UNECE.

- United Nations Environment Programme, 2015. The financial system we need: aligning the financial system with sustainable development. Nairobi: UNEP.

- Vangeel, W., Defau, L., and De Moor, L., 2021. The influence of a mortgage interest deduction on house prices: evidence across tax systems in Europe. The European journal of finance, 28 (3)), 245–260.

- Van Heerden, S., Ribeiro Barranco, R., and Lavalle, C., 2020. Who owns the city? Exploratory research activity on the financialization of housing in EU cities. Brussels: European Commission Joint Research Committee.

- Wainwright, T., and Manville, G., 2016. Financialization and the third sector: innovation in social housing bond markets. Environment and planning A, 49 (4), 819–838.

- Waldron, R., 2018. Capitalizing on the state: the political economy of real estate investment trusts and the “resolution” of the crisis. Geoforum; journal of physical, human, and regional geosciences, 90, 206–218.

- Wetzstein, S., 2021. Toward affordable cities? Critically exploring the market-based housing supply policy proposition. Housing policy debate, 32 (3), 506–532. doi:10.1080/10511482.2021.1871932.

- Wijburg, G., 2020. The de-financialization of housing: towards a research agenda. Housing studies, 36 (8), 1276–1293.

- Wijburg, G., Aalbers, M.B., and Heeg, S., 2018. The financialisation of rental housing 2.0: releasing housing into the privatised mainstream of capital accumulation. Antipode, 50 (4), 1098–1119.

- Wijburg, G., and Waldron, R., 2020. Financialised privatisation, affordable housing and institutional investment: the case of England. Critical housing analysis, 7 (1), 114–129.

- Wolf, M., 2021. What central banks ought to target. Financial times, 5. 3 March