ABSTRACT

Age-friendly cities and communities have emerged as a significant policy, participative and governance response to ageing and its spatial effects. This paper argues that it has important benefits in mobilizing older people, placing age on the urban agenda and building recognition across politicians, policy makers and programme managers. Based on the experience of Belfast (UK), the analysis suggests, however, that it needs to be understood within wider urban restructuring processes, the importance of the property economy and how planning practices favour particular groups and modes of development. Drawing on demographic data, policy documents and in-depth interviews, it evaluates the relationship between age and urban regeneration, research-based advocacy and central-local relations in health and place-based care. The paper concludes by highlighting the importance of knowledge in competitive policy arenas and the need to focus on the most excluded and isolated old and where and how they live.

Introduction

Demographic ageing and its impact on communities, transport and neighbourhoods are one of the defining features of the modern urban age (Buffel and Phillipson Citation2016). The prominence of the age-friendly city and its extension to more than 1000 places recognize its global significance and how policy makers respond to its long-term effects (WHO Citation2007; WHO Citation2018). The emphasis on coordination mechanisms, resource integration and bringing ageing into mainstream housing, planning and urban regeneration reveals the complexity of the governance challenge in creating age-inclusive cities. Here, the age-friendly concept reflects the broader shift within urban policy from a narrow concern with ‘land use’, to a more integrated commitment to ‘spatial’ planning (Healey Citation2010). In reality, space is produced and reproduced by complex and multilevel economic, social, demographic and environmental forces that need to be considered together in effective placemaking strategies. Modes of functional government are ill-equipped for the task and new forms of governance, that bring the relevant actors, institutions and policies together in a more collaborative arena are needed to direct change (Allmendinger and Haughton Citation2009). Just as planners stress the need to connect spatial processes, gerontologists emphasize temporal relations. Walker (Citation2018) argues that we should not focus on a static demographic category of the ‘old’ but embrace ageing processes across the life-course and emphasize the importance of lifetime neighbourhoods, adaptable communities and liveable places that connect ageing with a flexible version of space and the housing stock.

Bringing space, demography and planning into relation emphasizes the need to understand the construction of the age-friendly city, how it is enacted in competition with other narratives of urban ‘growth’ and how it impacts the material conditions of older people themselves. Here, the analysis highlights the value of the age-friendly discourse in cognitively shaping the city as a place in which to grow old, rather than a site of exchange, accumulation and value extraction, at least in the global North (Buffel and Phillipson Citation2019). Whilst ageing and its spatial effects are global, this paper, based in the United Kingdom, is primarily concerned with the contested legislative, policy and institutional context of advanced capitalist economies. In this respect, ageing and place is a battle for ideas in which evidence, different ‘ways of knowing’ and participatory research, not just participation in decision making, is critical (Rydin Citation2007, 54). The importance of knowledge and its role in forming, implementing and evaluating interventions is explored through the Age-friendly Belfast (AfB) programme that began in 2014 and is now in its second strategic plan between 2018 and 2021. Belfast is a metropolitan area of 690,000 people that has experienced de-industrialisation and the loss of jobs in heavy engineering and shipbuilding in particular as well as nearly three decades of violent conflict between Catholics who broadly want to reunify Ireland and Protestants who mainly want to retain the union with Britain (Herrault and Murtagh Citation2019). The need to regenerate the city, modernize infrastructure and present a normalized imagery to outside investors, tourists and skilled workers is an important backcloth for the pursuit of an age-friendly agenda.

The next section sets the context by reviewing the relationship between planning and the age-friendly concept and highlights the diversity of actors, arenas, policy scripts and decision-making levels involved in the process. The paper then draws on Healey’s (Citation1996, Citation2010) approach to institutional mapping and uses secondary data, policy documents and semi-structured interviews to understand the impact of AfB. Three issues are developed in detail and these include: the relationship between ageing and urban policy; the impact of civic society organizations on knowledge production and use; and strategic-local relations in ageing and health. The paper concludes by highlighting the institutional, political and economic constraints within which age-friendly strategies are evaluated and the potential for more tactical responses especially within the community sector.

Planning the age-friendly city

Scharlach and Lehning (Citation2016) trace the development of the age-friendly concept to a complex set of theoretical, empirical and behavioural explanations and related practices. Functional perspectives (being active), subjectivities (how older people feel) and adaptive processes (an ability to cope with life-course change) explain, in part, the broad scope of place-based policies and programmes. When international organizations, states and local authorities intervene to sustain a pro-age approach, the range of issues then extend to governance, participatory policymaking and service delivery. The substantive policy aim is to keep older people living in their home for as long as possible. In broad terms, most do want to remain in their own home and in familiar environments with established and functionally useful familial and community networks (O’Brien Citation2017). This connected set of conceptual and practical challenges, ideas about place and population change and how to make cities age inclusive is captured in the Age-friendly Cities and Communities (AFCC) framework developed by the World Health Organization (WHO Citation2007). The integrative approach aims to improve eight aspects of the city: outdoor spaces and public buildings; transportation; housing; social participation; respect and social inclusion: civic participation and employment; civic engagement including older adults’ information needs; community support and health services. In their review of the concept, Scharlach and Lehning (Citation2016) interpret these in three interlinked priorities, in an explicit ecological framework for the age-friendly city. First, is the environmental fit and in particular the availability of suitable housing, adaptable physical spaces and transport that meets the needs of people as they age. Second, social engagement, including participation in activities and creating positive attitudes to ageing and third, a multidimensional approach to health and wellbeing to enable older people to live more independent lives. Statistical indicators are critical to making progress to a more age-friendly state and to identify domains where progress is slow, where there are specific service gaps and the need for programme interventions.

Indeed, Scharlach and Lehning (Citation2016) argue that part of the challenge of the age-friendly concept is how data is used and prioritized, which, in turn relates to the competing policy, professional and institutional cultures involved in the process. For planners, normative, primarily statistical projections, provide a certain way of knowing while the community sector tends to emphasize the qualitative experiences of older people as consumers of the city (Rydin Citation2007; Buffel Citation2018). Evidence and argumentation is itself, an important discourse in competition and collaboration over the age-friendly city and who benefits (and loses) from policy processes. Here, the distinction between abstract and relational space and how we understand ageing-in-place is a well-established epistemological (and political) challenge. Madanipour (Citation2013) is especially critical of planning and its concern with abstraction and how space is reproduced via a narrow range of mainly normative methods and related practices. In reality, space is socially produced, constantly evolving and subject to competition between different interests with varying resources, political capital and methodological preferences:

Knowledge is inherently multiple, with multiple claims to represent reality and multiple ways of knowing. This is in contrast to the positivist claim of modernism that examination of the facts will reveal the truth. (Rydin Citation2007, 54, authors italics original)

However, the sheer presence of knowledge is insufficient to validate a particular position, gain recognition or ultimately affect decisions about how resources are allocated. For advocates of the age-friendly approach, governance structures and partnership working are critical, not just to share information, but to achieve effective policy integration and a more corporate approach to programme delivery (Torku, Chan, and Yung Citation2020). The capacity of such structures to bring together all the interests, with authority and in particular influence over resource decisions has, however, been questioned. Buffel and Phillipson (Citation2019) point to the absence of the private sector especially in property development, in creating a broad understanding of urban change and the role of older people within it. In her review of the age-friendly literature, Steels (Citation2015) also questioned the counterfactual case for partnerships, arguing that there is a dearth of evidence that they add value to existing governance arrangements in service delivery. For others, these are governing technologies, a managerial way to smooth conflict or a process of downloading to allow the state to withdraw from expensive welfare commitments, including ageing (Allmendinger and Haughton Citation2009).

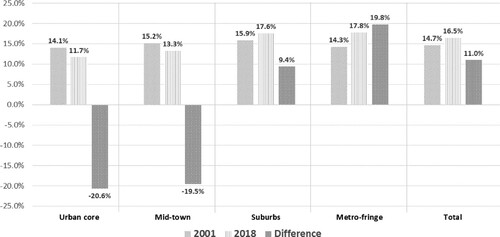

Kelley, Dannefer, and Masarweh (Citation2018) were also critical of the instrumental nature of the AFCC approach and the extent to which it ignored or devalued wider urban processes that influence how and crucially, where older people live. It is the property economy and how it is enabled by the planning system that creates demographic change, especially in the city centre, through explicit forms of gentrification. Young professionals and creatives are the most profitable market and small, high-density apartments are where investment returns can be maximized (Buffel and Phillipson Citation2019). Increasingly, the urban core, elite investment sites and waterfront developments are readied for the high growth economy (tech, finance and business services) and the specialized housing market that supports it. Older people are, via redevelopment, zoning ordinances and land assembly programmes gradually displaced from such sites to the periphery where services, assets and connectivity tend to be weaker.

The OECD (Citation2015, 35) evaluated 275 global cities and showed how they are characterized by increasing concentrations of young people in the core and older people at the periphery and these processes are both demand and supply driven. Certainly, inner-city housing markets have tightened for older people, especially in the reduction of social and affordable options, but preference and pre- and post-retirement migration cause others to downsize, seek out more scenic locations or move into residential care (Buffel and Phillipson Citation2019). O’Brien (Citation2017, 418) thus shows that social structures and the ‘spatial exclusion’ they create, leaves increasing numbers of older people in underserved and poorly connected neighbourhoods. Indeed, being old is now one of the most important risk factors in loneliness as older people, especially men, find themselves in more remote locations with diminishing friend and kinship groups and increasingly alienated from social networks (Tung et al. Citation2019). Community development approaches based on connecting the most lonely, emphasize the limits of planning policies, but also the necessary connection between the built and social environments. Physical activity and in particular walking, is at the heart of this relationship, in which infrastructure, safety, access to amenities and aesthetics are the priority (Cleland et al. Citation2019). In her analysis of stakeholder perspectives in Age-friendly Perth, Atkins (Citation2019) stressed the importance of interventions at a strategic level and early on in the planning process by creating a mix of land uses, a variety of age-specific housing options and better transport connections. These explicitly structural interventions are fundamental and set the context in which other community development, intergenerational or volunteering programmes can be delivered to full effect. Indeed, she goes on to criticize urban sprawl, specifically because it undermines the potential for such interventions, which can be best realized in compact, demographically mixed neighbourhoods, with a diverse service base.

Zhang, Warner, and Firestone (Citation2019) surveyed 559 planners on their efforts to deliver Liveable Communities for All Ages with a particular focus on the potential of the age-friendly approach. They show that while the physical design is clearly important, ‘facilitating practices and community engagement in the process are key to advancing planning for age-friendly communities’ (Zhang, Warner, and Firestone Citation2019, 31). They call for an emphasis on the social aspects of ageing that stress personalization, co-production and governance models that give older people a meaningful say in decisions that affect their lives. When older people are given a voice, they articulate immediate concerns about a living income, fuel poverty, crime and loneliness. Finlay, Gaugler, and Kane (Citation2020, 780) argue that it is poverty that shapes older people's life chances and when the right type of participatory design is used, ‘issues such as financial deprivation, transient housing, commercial disinvestment and social isolation’ come to the fore.

The way in which age-friendly strategies are pursued within overarching structures of urban change, the capacity of age organizations to influence or resist these processes through participatory design and how alternative evidence is used to challenge dominant formations are priorities running through the analysis. So too is the capacity of age-friendly governance structures to leverage resources or alter programme delivery in more inclusive ways. The value of the age-friendly city is that it creates an arena to bring these strands together in particular places and points in time. The multiple objectives, interests and discourses, competition for attention and tactical manoeuvres emphasize the real-politick of the age-friendly city and these are explored next in the context of Belfast.

Research design

In her review of the age-friendly literature, Steels (Citation2015) emphasized the number of studies that are concerned with stakeholder relationships, collaboration and the way in which interests, including older people, participate (or not) in programme delivery. Healey (Citation1996, Citation2010) advocates an institutional research design to unpack these processes and how decisions are arrived at, where and in whose interests. Here, she emphasized the need to evaluate: who is involved; the performance of governance and government structures; which stakeholders dominate; the tactics used by various groups to pursue their interests; the importance of discursive strategies and the use of multiple forms of knowledge; and how resources are allocated and ultimately, how decisions impact on the lives of the citizenry.

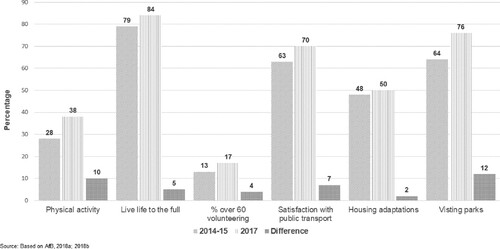

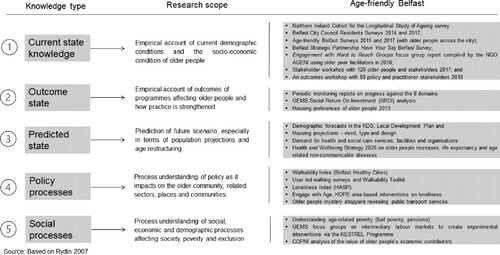

This provides a framework for the empirical design in Belfast and sets the policy and related stakeholder focus within the quantitative data used to both describe the spatial nature of ageing and the performance of AfB itself. The research was formally approved by the University’s Faculty Research Ethics Committee and although the respondents were not vulnerable, care was taken to ensure informed consent, anonymity and data privacy throughout the analysis. shows that nine indicators provided a baseline from which to track the performance of the strategy between 2014 and 2017 when seven comparative indicators were measured. The policy analysis first involved: an evaluation of 16 strategy and programme documents in planning; housing and regeneration; health care; older people; and community development initiatives. Following Healey, this then, informed a series of 22 semi-structured, in-depth interviews with representatives from the main organizations on AfB, although these developed over time to identify other interests with a stake in the policy arena. The starting point was a stakeholder map, which identified the key organizations, individual staff and a rationale for their status as ‘stakeholder’. The questionnaire examined inter alia: how respondents understood and prioritized problems; set and delivered policy objectives; interacted with other policy and political interests; and monitored and evaluated the impact of their programmes.

Table 1. Research design and data sources.

The 22 interviews were analyzed by one lead researcher to avoid problems of ‘inter-rater reliability’ and ‘coding agreement’ between multiple readers (Braun and Clarke Citation2020, 7). The approach used systematic coding to generate initial themes that were revealed and refined as patterns emerge, consistency was maintained, outliers evaluated and saturation was reached across the dataset. Initial codes are kept open, organic and interpretive as the basis of developing the final theme. This can be demonstrated in the second of the three themes discussed in the empirical section on civic society and alternative ways of knowing. Socio-spatial concepts tell us about the distinction between abstract and subjective space and how they are separately described in the formality of demographic and economic forecasts in the first case and from the lived experiences of older people as users of the built environment in the second. Here, distinct codes emerge around qualitative and quantitative research types, separately aligned (not always neatly) with particular clusters of stakeholders, policies and even individual organizations. These codes build, via the tactical use of different forms of data, research and programme evaluations to a theme, which is about knowledge production and use. In prioritizing a particular approach to space, within the context of an age-friendly city, it is therefore, important to emphasize that this process is not purely inductive or shaped in ‘a theoretical vacuum’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2020, 4). Thus, the need to understand urban restructuring and the economic as well as the demographic factors that reproduce space highlight the need to look at planning, the property economy and urban regeneration and in whose interest such regimes act.

Age-friendly Belfast

Belfast was formally designated an Age-friendly City in 2014, with an emphasis on empowering older people to be active and highlighting the implications of ageing among politicians, policymakers and businesses, especially in the retail sector (AfB Citation2014). The revised plan for 2018–2021 stressed: the need for stronger partnership working; more age-appropriate walking and transport infrastructure; a focus on social inclusion; improving access to health and social care; and protecting the financial security of the poorest old (AfB Citation2018a). The revised plan was informed by a detailed statistical assessment of the age-friendly domain indicators (AfB Citation2018b) but also had a formal link with the Greater Belfast Seniors Forum (GBSF), a network representing six local age networks across the city (G6 group).

The Plan for 2018–2021 was also based on a range of quantitative surveys and structured focus groups with older people and stakeholders across the statutory, community and private sectors. This enabled a comparative analysis on the eight age-friendly domains. The metrics draw on different surveys with a range of populations, participants and methods, but they are clearly cited by AfB to enable a transparent evaluation of the validity and reliability of each one (AfB Citation2018a; Citation2018b). shows significant improvement in the lives of older people over the period of the first strategy with more people: physically active over 30 min (+10%); visiting parks (+12%); feeling Belfast is a city where they can live life to the full (+5%); and volunteering (+4%). They are also more satisfied with public transport (+7%) and accessing support for housing adaptations (2%). The baseline report (AfB Citation2018b) also showed that older people feel safer in their neighbourhood after dark (+4%), 40 businesses had signed up to the Age-friendly Charter and in 2014–2015, a pilot programme to reduce isolation worked with 1300 older people and showed that 340 recorded a measurable reduction in their feelings of loneliness.

However, the analysis also showed that isolation, loneliness and mental health were compound problems faced by older people, especially in the most deprived communities. While people are living longer in Belfast, there is a difference between the most deprived and the least deprived areas in the city of 5.6 years for females and 9.2 years for men (AfB Citation2018b, 22). Similarly, the Have Your Say survey in 2017 found that 26% of those aged 50+ had been treated for anxiety or depression in the past 12 months and the NICOLA (longitudinal study for older people in Northern Ireland) data indicates that nearly one-in-five older people (18%) do not have any close friends. This is higher for men (22%) than women (16%) and for those in the oldest age cohorts (27%) (AfB Citation2018b, 25).

Age-friendly policies and the city

Kelley, Dannefer, and Masarweh (Citation2018) argued that this focus on indicators misses deeper complexities of the age-friendly arena as a site of placemaking in all its contradictions and possibilities. There are, of course, a number of dimensions to this complexity, but the literature emphasizes the need to understand the context of urban change, the capacity of older people and advocates to challenge dominant growth formations and the significance (or not) of evidence to shift resource decisions within collaborative governance arenas. Drawing on the document analysis and related stakeholder interviews, three themes reveal the performance and potential of the age-friendly concept:

Urban regeneration, growth and the property economy;

Civic society and alternative ways of knowing; and

Strategic-local relations in ageing and health.

Urban regeneration, growth and the property economy

The Regional Development Strategy (RDS) 2035 for Northern Ireland emphasizes the need to modernize infrastructure, support economic development and strengthen connectivity, nationally and globally. Objectives around social inclusion, shared space and a commitment to mixed housing, which were a feature of the previous Belfast Metropolitan Area Plan 2001–2015 (BMAP), have been diluted or dropped altogether in favour of a more explicit growth agenda. The RDS provides the framework for local plans and here the Belfast Local Development Plan (LDP) 2035 emphasizes the need to recover from decades of de-industrialisation, violent conflict and political instability to justify a particular form of neoliberal renewal (Herrault and Murtagh Citation2019). The former shipyard is being regenerated as a mixed-use development (apartments, offices, hotels and entertainment) through decontamination and reclamation, land assembly and infrastructure provision in a major public-private waterfront project. The LDP identifies a similar growth model in the Innovation District based on the new Ulster University (UU) campus in the Cathedral Quarter to the north of the city centre:

There are opportunities to build on the Ulster University city campus investment to promote the development of a lively mixed-use innovation district to secure employment and residential opportunities for graduates and entrepreneurs. (BCC Citation2019, 55)

There is a big push within the plan to get people living in the city centre but it’s about making sure that there is something for older people as well as young professionals or more transient younger populations. (Housing association provider)

In short, the effects of these processes is that ‘Belfast city centre shuts down at six o’clock, which might create a stigma attached to city centre living (and with) a shift in the demographics of Belfast as the student population is going to move into the centre’ (Housing association provider). The same official pointed out that two significant sites originally designated in BMAP for social housing in the Cathedral Quarter have now been developed for student accommodation and a university carpark. The problem for AfB is getting effective representation from planners at either a strategic or operational level, which is necessary to influence the content of the LDP and push back commercial interests on particular sites. Public health officials also recognize that caring for older people in their home requires a different type of community, transport system and infrastructure to encourage physical activity. These explicit placemaking objectives are difficult to achieve because of the absence of planners, their discursive policy culture and their preoccupation with economic growth:

I’ve never yet been at a meeting where planners are there. I would love it, we would love it. I think we speak different languages. I don’t know whether there is a feeling that planners are not really interested in health. Maybe I’m being disingenuous … (planning) is really more about the economic aspects, which is high on the priority list, but you do wonder “well, how is this going to affect planning and health?.” (Public health official)

Kohijoki and Koistinen (Citation2019, 5) made the point that city centres mean more to older people than ‘satisfying consumption needs’ because they are asset-rich, offer a range of essential services, social experiences and connectivity to transport and health facilities. Attitudinal research shows that older people do want to stay in the neighbourhood, where they live and only 20% of people over-65 in Northern Ireland want to move from their present home (NIHE Citation2013). The housing association sector has been critical of the lack of access they have to sites in the city centre, because of pressure from commercial developers and zoning regulations, but this has downstream consequences for older people, their sense of place and how they might be supported by their community:

It is about having somebody who will realise that Mrs. Jones has not been seen out of the door … A lot of what we do is not about building homes but building the community and older people within it. (Housing association provider)

Civic society and alternative ways of knowing

The problem for older people and NGOs is that this policy gap has deepened social and spatial disconnections such that ‘loneliness and isolation have jumped up the agenda and we are reactive to it’ (Older people NGO representative). A more sociological discourse on ageing, loneliness and place is evident among community groups, NGOs and network organizations. There is also recognition that the discourse needs to assert itself in competition with more dominant professional or official ideologies and methodologies. The value of evidence-based argument to challenge other forms of ‘knowing’ has been an important tactic among outsider groups and resource weak interests (Madanipour Citation2013). For some Council officials, too much of the research is focused on policy outcomes rather than being centred on, or informed by, older people themselves:

(Older people need) to influence the design of the research and the questions being answered or the questions that older people would like to be asked. It is that interchange between the research community on what is a priority for older people, that would be most useful. (Belfast City Council older people section)

The information came from older people and we had initially workshops and questionnaires with older people, then we had ones with stakeholders and then we had a joint one with all stakeholders and older people, so that everybody signed-off the Plan. (AfB programme official)

Here, AfB recognizes that the type of knowledge they produce also needs to relate to normative cultures within planning, transport and urban management. They worked with Belfast Healthy Cities (BHC Citation2014) to produce a Walkability Index for the city to identify problems sites, physical barriers and in particular, the need to improve footpath infrastructure. The Index applied a recognized methodology and used geographic information systems to present a comprehensive analysis that informed specific walking studies undertaken by older people themselves. Using photo-elicitation and structured interviews, older people: identified barriers to shops, services and health facilities; how to open access to urban parks; and the need for enforcement (cars parked on pavements, cyclists and incursion from cafes and bars). By 2016, 24 walks involving 250 older people had been conducted and these formed the basis of a Walkability Assessment Tool to provide guidance to urban managers and planners. The research had a limited short-term impact on the delivery of the official government urban realm strategy, Streets Ahead 2013, but it did initiate a critical debate in the city council about the need for an alternative approach. In particular, AfB pointed out that the council prepared its own strategy that stressed the importance of the commercial core as a ‘shared space for older people’ that included the potential of ‘super-crossings’ at main intersections, wider footpaths and improved seating and toilet provision (BCC Citation2015, 65).

A similar approach was applied to loneliness. An isolation index was prepared for the city that measured areas where the risk of loneliness reflected known characteristics such as being aged 75 or older, living in single person households, not having access to a car and living in areas of social deprivation (AfB Citation2016). The performative nature of the analysis was recognized by AfB members as ‘a way of speaking to’ policy makers, especially in housing and planning (NGO member of AfB). The NGO Engage With Age, one of the AfB partners, undertook a mixed methods evaluation of their experimental HOPE programme, which targeted hard-to-reach older people in eight neighbourhoods where the risk of loneliness was high. HOPE worked through community and statutory intermediaries to identify and engage particular individuals and delivered a programme of practical and therapeutic supports, personal activities and social networking events. The evaluation showed significant percentage improvements in entry and exit self-assessment against a range of indicators, including keeping in touch (+30%), feeling positive (+32%) and staying well (+12%) (EWA Citation2015, 8).

The potential of older people as active producers of the age agenda also relates to the strength of the governance regime and how this has evolved over time. The main older people’s NGO (AGENI) trained members of the G6 and GBSF groups in policy consultation, the use of data and lobbying techniques. In particular, they focused on Rydin’s process role by providing a critical user voice on the way in which the AfB strategy is implemented:

You have to put what the older people say against the statistics as well. Its not perception as its important because older people perceive it not to be right and yet the statistics are different. (AfB programme official)

However, other sectors have been critical of such participatory methods and the narrow range of older people they attract, because they tend to prioritize immediate concerns rather than the deeper structural problems faced by the poorest old. An emerging social enterprise sector has provided services, access to work and managing older people’s centres. This direct confrontation with poverty they argue, reflects a more politicized approach to defining research priorities:

We’ve developed our own focus groups of older people to take their views about what it was like to be unemployed, what it was like to be feeling the way they were on the shelf and had no more usefulness in terms of the workplace. This was people, 50-plus, who weren’t necessarily in the economic safety net of being able to retire and just live off a personal pension pot. (Social enterprise manager)

The added benefit of the KESTRAL programme was that people were reporting improvements in their resilience, a reduction in their trips to the GP, better management of their existing health conditions and much less social isolation. This was a big issue and one on which we know that older people who are socially isolated are more likely to experience health, social emotional and wellbeing problems. (Social enterprise manager)

Strategic-local relations in ageing and health

The health and social care arena adds to the complexity of the age-friendly discourse by emphasizing the importance of policy scale. The Northern Ireland Health and Wellbeing Strategy 2026 frames ageing as a resource problem in which the projected growth in the number of older people creates enormous financial, logistic and institutional challenges. The answer, again, is to enable people to live in their own homes for as long as possible via dwelling adaptations, peripatetic care and community development support. Whilst this clearly fits with the age-friendly concept, AfB has little leverage over regional health policy and the resources it commands, especially when it comes to contradictions in programme objectives. For example, the strategic housing authority points out that there have been real cuts in the Supporting People budget ‘of more than 20% in the last 10 years’ (Housing management official). Supporting People provides grants primarily to community and voluntary sector organizations for housing adaptations and community programmes to tackle loneliness and deliver services to the most isolated old. It would be wrong to criticize AfB for not protecting the social housing budget, but it shows that such governance arenas have comparatively little capacity to resolve policy contradictions, especially in the high-cost social care sector.

Indeed, these concerns are echoed in the government’s Active Ageing Strategy 2016–2021, which repeated the now-familiar tropes on effective policy coordination, enabling older people to live independently and helping them to achieve their full potential. As O’Brien (Citation2017) noted, the emphasis on being active, engaged and motivated is a deliberate discursive framing centred on individual responsibilities and potentials, rather than on the economic, spatial and cognitive capabilities that shape older people’s lives. For example, it often fails to acknowledge the precarious and transient experiences of older people in private renting, who are homeless or who are affected by complex mental health and addiction problems. In Northern Ireland, Active Ageing stresses the importance of interagency coordination but does not address the relationship with local authorities or how built environment programmes would help older people live in their community for longer. Departmental officials are unclear about how the strategy is delivered locally but ‘are likely to go down the age-friendly route’ even though they acknowledge that structures outside Belfast are not well developed (Central government Active Ageing official). They also concede that there are no new resources attached to the policy and that most of the recommendations are drawn from existing strategies and programmes:

There is also an element that, as quite often happens with strategies, they can be quite forward looking but they also contain a lot of business-as-usual and things which have already started and tweaking of things which are already in place. (Central government Active Ageing official)

We have had reports to say yes, this programme, it works, it is massively value-for-money. What should happen after is more money going into it to make it happen – make it be able to do more. A lot of time what happens is you’ve got a brilliant evaluation that leads nowhere. (Central government housing official)

Conclusions

The relationship between research and advocacy in the context of AFCC is an important one, especially for weak, outsider and community interests. Diverse, innovative and user-centred knowledge has been applied by AfB and in particular, older people’s groups to shift the discourse away from growth-based models of urban development. The age-friendly city offers, at least a framework, around which the place of older people can be raised, but if it fails to alter their material economic conditions or leverage these resources then its value is open to criticism. Worse, it could represent a diversionary tactic, incorporating potentially disruptive groups in performative governance regimes that implicitly flank overriding planning, housing and infrastructure programmes.

But that misses the point about the potential of the age-friendly concept to mobilize older people, employ evidence-based advocacy and push back on particular programmes and decisions. AfB, statutory providers and advocacy groups used research, created coalitions and focused on particular issues, such as transport, to effect change. AFCC indicators that are reported under the eight domains, to some extent vest responsibility for progress with statutory partners in transport, housing, health care and so on. Quantitative data also mapped the scale of loneliness and problems with walking, while participative methods evaluated transport services, barriers in the built environment and the importance of economic inclusion. The KESTREL programme also emphasized the centrality of work to some older peoples identities, demonstrated the social impact of age-specific labour markets and is now an important aspect of the current age-friendly strategy for Belfast. Challenging dominant interests, ideologies and professionals with embedded epistemic cultures is, of course, a difficult challenge. As Leino, Santaoja, and Laine (Citation2018) show, the skills to broker knowledge between actors in meaningful ways is an area for development in AfB and in age-friendly governance structures more broadly.

This is only one case study and as such, speaks to particular conditions in a city with unique patterns of segregation and urban development. It did not capture the complexity of decision-making systems, especially the role of the private sector and their impact on key sites and regulatory processes including land assembly, zoning and preferred developer status. The corporatist nature of decision making around major urban development projects is not only relatively closed to researchers but also to semi-state bodies in the age-friendly network. In this respect, the analysis is broadly based in the global North, which is not easily transferred to Southern conditions and emergent economies operating in very different cultural contexts. This raises the potential for stronger comparative research between cities in the North and South and how shared processes, such as ageing, travel across different institutional, political and policy boundaries and with what effect. Certainly, there is evidence to show that some strong municipal structures in Latin America have resisted neoliberal urbanism and retained a redistributive ethic across spatial policies and how they impact on the most vulnerable old (Geddes Citation2014).

Similarly, the social economy and community-owned enterprise models of care, tackling loneliness and delivering services appear useful, if isolated responses to ageing. However, their limitations and/or how they might be scaled or replicated is less well understood. Their ethics, potential for incorporation or simply downloading responsibility to older people also need to be evaluated in the context of the age-friendly concept and its potential for genuinely inclusive practice. Knowledge brokerage as a distinct governance function is a related area for further study. The extent to which older people’s experiences can be objectively captured and used to challenge, change or facilitate pro-age policies calls for a distinct set of functions, skills and tactics, especially by NGOs, community groups and older people themselves. How these skills can be defined and supported and to what effect, might be an important integrative function of the wider AFCC movement and its impact on urban development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Age Friendly Belfast (AfB). 2014. Age-Friendly Belfast Plan 2014-2017. Belfast: AfB.

- Age Friendly Belfast (AfB). 2016. Mapping Isolation and Loneliness Amongst Older People in Belfast. Belfast: AfB.

- Age Friendly Belfast (AfB). 2018a. Age-friendly Belfast Plan 2018-2021. Belfast: AfB.

- Age-friendly Belfast (AfB). 2018b. Age-friendly Belfast Progress Report April 2018. Belfast: AFB.

- Allmendinger, P., and G. Haughton. 2009. “Soft Spaces, Fuzzy Boundaries, and Metagovernance: The New Spatial Planning in the Thames Gateway.” Environment and Planning A 41 (3): 617–633. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/a40208.

- Atkins, M. 2019. “Creating Age-Friendly Cities: Prioritizing Interventions With Q-Methodology.” International Planning Studies, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2019.1608164.

- Belfast City Council (BCC). 2015. Belfast City Centre Regeneration and Investment Strategy. Belfast: BCC.

- Belfast City Council (BCC). 2019. Belfast Local Development Plan. Belfast: BCC.

- Belfast Healthy Cities (BHC). 2014. Walkability Assessment for Healthy Ageing. Belfast: BHC.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2020. ““One Size Fits All? What Counts as Quality Practice an (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis?” Qualitative Research in Psychology, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238.

- Buffel, T. 2018. “Social Research and Co-Production with Older People: Developing Age-Friendly Communities.” Journal of Aging Studies 44: 52–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2018.01.012.

- Buffel, T., and C. Phillipson. 2016. “Can Global Cities Be ‘Age-Friendly Cities’? Urban Development and Ageing Populations.” Cities 55: 94–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.03.016.

- Buffel, T., and C. Phillipson. 2019. “Ageing in a Gentrifying Neighbourhood: Experiences of Community Change in Later Life.” Sociology 53 (6): 987–1004. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038519836848.

- Cleland, C., R. S. Reis, A. A. Ferreira Hino, R. Hunter, R. C. Fermino, H. Koller de Paiva, B. Czestschuk, and G. Ellis. 2019. “Built Environment Correlates of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour in Older Adults: A Comparative Review Between High and Low-Middle Income Countries.” Health and Place 57: 277–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.05.007.

- Commissioner for Older People NI (COPNI). 2014. Appreciating Valuing: The Positive Contributions Made by Older People in Northern Ireland. Belfast: COPNI.

- Engage With Age (EWA). 2015. Just Ask the Lonely: Lessons Learned from the HOPE Programme. Belfast: Engage With Age.

- Finlay, J. M., J. E. Gaugler, and R. L. Kane. 2020. “Ageing in the Margins: Expectations of and Struggles for ‘A Good Place to Grow Old’ Among Low-Income Older Minnesotans.” Ageing and Society 40 (4): 759–783. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X1800123X.

- Geddes, M. 2014. “Neoliberalism and Local Governance: Radical Developments in Latin America.” Urban Studies 51 (15): 3147–3163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013516811.

- Healey, P. 1996. “Consensus-Building Across Difficult Divisions: New Approaches to Collaborative Strategy Making.” Planning Practice and Research 11 (2): 207–216. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459650036350.

- Healey, P. 2010. Making Better Places: The Planning Project in the Twenty-First Century. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Herrault, H., and B. Murtagh. 2019. “Shared Space in Post-Conflict Belfast.” Space and Polity 23 (3): 251–264. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2019.1667763.

- Kelley, J., D. Dannefer, and L. I. Masarweh. 2018. “Addressing Erasure, Microfication and Social Change: Age-Friendly Initiatives and Environmental Gerontology in the 21st Century.” In Age-friendly Cities and Communities – A Global Perspective, edited by T. Buffel, S. Handler, and C. Philipson, 51–71. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Kohijoki, A. M., and K. Koistinen. 2019. “The Attractiveness of a City-Centre Shopping Environment: Older Consumers’ Perspective.” Urban Planning 4 (2): 5–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v4i2.1831.

- Leino, H., M. Santaoja, and M. Laine. 2018. “Researchers as Knowledge Brokers: Translating Knowledge or Co-Producing Legitimacy? An Urban Infill Case from Finland.” International Planning Studies 23 (2): 119–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2017.1345301.

- Madanipour, A. 2013. “Researching Space, Transgressing Epistemic Boundaries.” International Planning Studies 18 (3–4): 372–388. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2013.833730.

- Moos, M., N. Revington, T. Wilkin, and J. Andrey. 2019. “The Knowledge Economy City: Gentrification, Studentification and Youthification, and Their Connections to Universities.” Urban Studies 56 (6): 1075–1092. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017745235.

- Murtagh, B. 2017. “Ageing and the Social Economy.” Social Enterprise Journal 13 (3): 216–233. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-02-2017-0009.

- Northern Ireland Housing Executive (NIHE). 2013. Research on the Future Housing Aspirations of Older People. Belfast: NIHE.

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). 2020. 2019 Mid-Year Population Estimates for Northern Ireland. Belfast: NISRA.

- O’Brien, E. 2017. “Planning for Population Ageing: The Rhetoric of ‘Active Ageing’ - Theoretical Shortfalls, Policy Limits, Practical Constraints and the Crucial Requirement for Societal Interventions.” International Planning Studies 22 (4): 415–428. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2017.1318702.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2015. Ageing in Cities. Paris: OECD.

- Rydin, Y. 2007. “Re-Examining the Role of Knowledge Within Planning Theory.” Planning Theory 6 (1): 52–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095207075161.

- Scharlach, A., and A. Lehning. 2016. Creating Aging-Friendly Communities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Steels, S. 2015. “Key Characteristics of Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: A Review.” Cities 47: 45–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.02.004.

- Torku, A., A. P. C. Chan, and E. H. K. Yung. 2020. “Age-friendly Cities and Communities: A Review and Future Directions.” Ageing and Society, 1–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20000239.

- Tung, E. L., L. C. Hawkley, K. A. Cagney, and M. E. Peek. 2019. “Social Isolation, Loneliness, and Violence Exposure in Urban Adults.” Health Affairs 38 (10): 1670–1678. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.0056.

- Walker, A. 2018. “Why the UK Needs a Social Policy on Ageing.” Journal of Social Policy 47 (2): 253–273. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279417000320.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2007. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide. Geneva: WHO.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2018. The Global Network for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: Looking Back Over the Last Decade, Looking Forward to the Next. Geneva: WHO.

- Zhang, X., M. E. Warner, and S. Firestone. 2019. “Overcoming Barriers to Livability for All Ages: Inclusivity is the Key.” Urban Planning 4 (2): 31–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v4i2.1892.