ABSTRACT

Drawing from my first-hand observations and embodied experiences of having collaborated with HORA over the course of several years, this paper discusses an under-investigated area within the field of disability and performance: pioneering work by directors and with learning or cognitive disabilities, an area which has not yet been addressed in the expanding field of disability and performance studies.

‘ … so where are the learning disabled writers, directors, designers and choreographers?’, Calvert asked years ago (Citation2009). Nowadays they could respond: ‘We are here!’ – Really?

Recently many theatre and dance companies of disabled performers in Europe have developed new working models enabling a large amount of co-authorship between disabled and non-disabled performers, challenging dominant models of theatre-making or choreography. Some theatre or dance companies working with performers with cognitive disabilities have begun – independently of each other – to question the division of work within their companies, and to foster the disabled ensemble members’ authorship, not only as performers but as directors, stage or costume designers, authors, and choreographers. In November 2015, together with dramaturge Marcel Bugiel, I curated a showroom within the international theatre festival ‘No Limits in Berlin’ that contained a number of works in this category. The three-day platform focused on the question Wen kümmert’s, wer spricht? [Who cares who is speaking?] presented pioneering work by directors, authors, and choreographers with cognitive disabilities. These works represented different approaches by companies such as ‘Meine Damen und Herren’ (Hamburg, Germany), ‘Per.Art’ (Novi Sad, Serbia), Theater HORA (Zurich, Switzerland) and ‘Mind the Gap’ (Bradford, United Kingdom) and raised aesthetic and ethical questions, which were discussed during the showcase. Question such as: ‘How does one properly critique a disabled director’s work?’; ‘If even theatre that refers to the traditional separation of roles, able-bodied director and disabled actor, is a niche theatre, how can these new forms find their place in the theatrical landscape?’; ‘How can one convince the cultural authorities of the quality of these works?’; and ‘Do we [the disabled actors] have to play the role of the director now?’ (These are taken from statements made by participants in the showroom/symposium at No Limits Festival Berlin 2015.)

In this paper I explore the emergence of directors with cognitive disabilities as a theatrical practice, focusing on the relationship between the artist with disabilities and the non-disabled collaborators who facilitate this work. I propose a working model to enable better understanding of the position of disabled directors as they negotiate between autonomy and supporting structures. Then I apply this model in the context of a case study of Theater HORA’s current long-term project Freie Republik HORA, which I have been investigating as an embedded researcher since 2013. In the third phase of this project, six selected ensemble members are on track to realise their own directing concepts. These are connected to the research project ‘DisAbility on Stage’, a collaborative project funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation at the Zurich University of the Arts. I explore the conditions and influencing factors that constitute the process of directing, such as ‘conception’, ‘organisation of working space’, ‘reflection and observation’, and ‘correction’ (Matzke Citation2015) and how these need to be adapted when applied in the work of directors with cognitive disabilities: Based on Matzke’s observations I develop a working tool in order to better understand the necessity of co-creation in the theatre. I conclude with a discussion of how this development provokes a critical rethinking of the director’s or choreographer’s role within the theatre.

The politics of (in)visible support

As artists with cognitive disabilities negotiate autonomy and assistance, their creative work is always caught in a paradox. Carlson and Kittay (Citation2009, 316) argue that the more people with significant cognitive disabilities obtain a greater degree of agency, the more assistance is required. In the context of theatre with and by people with cognitive disabilities, Hargrave (Citation2015) points out that the ‘support structures’ that an artwork by artists with cognitive disabilities need in order to be realised are often invisible, in contrast to the works of artists with other types of disabilities: ‘A physically disabled performer may reveal the supportive infrastructure of prostheses, chairs or crutches; a learning disabled actor, however, may depend on invisible support structures such as the extended time required to memorise the text’ (2015, 100). In an artistic context, normative perceptions of a genius artist are challenged, as ‘[t]he offer of unconditional support is perhaps the highest human offer, but aesthetically represents a low order of merit’ (2015, 100).

I argue that the support structures – or the position of the assistant – in theatre by artists with cognitive disabilities are not necessarily hidden per se. Sometimes such structures are even made invisible, as there exists a politics of (in-)visible assistance, particularly in theatre by artists with cognitive disabilities. A performer with a learning disability may use a script on stage because she is unable to memorise the text. From an artistic perspective, such visible assistance might be regarded as an ‘accident’ or a failure. This reveals what Tobin Siebers called the ‘ideology of ability’ (Citation2012, 29), as well as the connection between performance and discipline highlighted by McKenzie (Citation2001). Kittay (Citation2011) proposes an alternate perspective. She elaborates that, ‘[t]he need for care, or as many would rather say “assistance,” is viewed not as a sign of dependence but as a sort of prosthesis that permits one to be independent’ (Citation2011, 50). Instead of regarding assistance and autonomy as a binary choice, she advocates ‘ … an ethics that puts the autonomous individual at the forefront, that eclipses the importance of our dependence on one another, and that makes reciprocal exchanges between equals, rather than the attention to other’s needs … ’ (Citation2011, 51).

Moreover, any feelings of unease while watching performers with cognitive disabilities who need assistance are based on the assumption that artists without disabilities are not in need of support. This perspective neglects the discourse on relationality and active interdependencies in the making of contemporary performance art (Jackson Citation2011). Some performances by disabled artists commit to an ethics of ‘interdependent embodiment and en-mind-ment’ (Kuppers Citation2011, 9), such as the Helping Dances project by the Olimpias (Kuppers Citation2014).

In contemporary performance/theatre the rehearsal processes are staged and the division between creation process and artwork is constantly challenged. The staging of the rehearsal process in the theatre with artists with cognitive disabilities, however, always raises questions of autonomy and assistance by putting the working relationships in the spotlight. Recent performances have dealt with this issue ironically, like Ganesh of the Third Reich by the Australian Back to Back Theater, when a non-disabled director in a trainer dress gives instructions as a second layer of meaning in the performance. Or in the show Regie (2014) by Berlin-based Theater Thikwa’s, which is about three performers with Down’s Syndrome who play the role of the directors (as performers). It was staged by the German performance collective Monster Truck as a response to their first collaboration Dschingis Khan (2012). In the first performance, non-disabled performers boss around and bully the disabled Thikwa performers. In the second part of the show, the non-disabled performers leave the stage and the Thikwa performers apparently do what they want. In fact, the Monster Truck performers still give orders, as the performers wear earplugs. Both works by Theater Thikwa and Monster Truck have instigated controversial discussions as they raise issues of artistic control and personal agency. As a consequence of this ethical dimension to performance by performers with cognitive disabilities, the relationship between the disabled artist and co-worker has not yet been addressed. Indeed, there is something of a ‘blind spot’ as to how to describe cognitively disabled directors’ authorship within this complex framework.

Different theatre companies in Europe are currently developing new working models in order to increase the disabled ensemble members’ autonomy. In the theatre company Meine Damen und Herren in Hamburg, for example, the ensemble members with cognitive disabilities began their own directing projects in 2014, as two disabled performers had indicated their interest in creating their own solo pieces. Since 2015, every Thursday has been dedicated to the ensemble members’ own projects. The company directors work as managers, providing advice if requested. Sometimes external artists visit rehearsals and give feedback.Footnote1 This shows that the position of the coach is not necessarily dedicated to a particular staff member or to the company director. The views of external artists prove a fruitful model for the directors enabling them to find their own way and artistic language.

Already some years ago, former protagonist Wolfgang Fliege from Theater Thikwa in Berlin, now retired, created many theatre projects in collaboration with the non-disabled actor Dominik Bender. In Kafka am Sprachrand (‘Kafka on the edge of language’), Fliege improvises within a given (textual) structure, and enters into a poetic dialogue with the famous writer Franz Kafka. ‘Wolfgang doesn’t learn his text – he has text’, his colleague Dominik Bender explains (Schmidt Citation2017). Fliege produces most of his text live on stage, practicing a sort of ‘stream of consciousness’. In another work, Die Flieger (‘Airmen’, 2007), Dominik Bender conducted interviews with Wolfgang Fliege, which he then compiled to the play. On stage, Bender speaks Fliege’s texts and Fliege comments on his own text. The question ‘Who is speaking?’ cannot be answered. What can be seen is that Fliege and his collaborator Bender enable each other to perform.

From the creative enabler to the creative collaborator

Comparisons and contrasts can be drawn between the performing arts – a highly hierarchical art form – and fine art. German Arts Scholar Poppe (Citation2012) conducted an empirical study on ‘artists who need assistants’. According to his study, the assistant’s role goes beyond that of a mentor or supporter. The assistant’s responsibilities might include curating, arts administration and management, and fundraising. A role called ‘creative enabler’ has been established by disabled artists in a variety of artistic disciplines in the United Kingdom. According to Michael Achtman, the famous British company Graeae invented the position. Having worked with Graeae and other artists as a creative enabler, Achtman characterises his concept follows:

A creative enabler is a support worker with skills and experience in the area practised by the disabled artist; this allows the artist to call on the creative enabler to assist in ways they could not ask of a general access support worker or personal assistant. (Citation2014, 36)

One of the most challenging aspects of the creative enabler role is maintaining the boundary between access support and artistic input. As an artist yourself working closely on a project, it is easy to become invested in the outcome and sometimes difficult to suppress your own creative ideas. But the access support aspect of the role asks that you hold back – as an interpreter you would not add your own thoughts when repeating someone’s speech; as a playwright’s scribe you would not suggest ideas for scenes or characters. (Citation2014, 36)

The collaboration between the disabled artist and the co-operator can be best described using a spectrum, from the creative enabler as simply an organiser to creative enabler as an artistic co-creator. In keeping with the idea of a theatre of interdependency, in the theatre directing and/or choreographing is not linked to a subject, but the division of responsibilities might vary within the ensemble. According to the German Theater Studies Scholar Annemarie Matzke, the director’s duties from the production to the performance may include ‘conception’, ‘organisation of working space’, ‘reflection and observation’, and ‘correction’ (Citation2015, 16). In theatre projects with cognitively disabled directors, the ‘core business’ of directing is intertwined with support or assistance, which is needed for those with cognitive disabilities to be able to obtain artistic leadership.

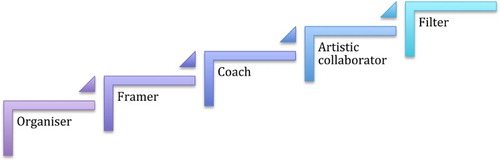

Combining these different tasks of directing and support, different modes of co-creation become possible from the creation to the show, which are connected by flowing transitions. I propose the scheme in .

‘Organiser’: This person organises the working space, the rehearsal schedule and other duties without any artistic involvement. This is coincident with the actual concept of the ‘creative enabler’, although the organiser does not necessarily have an artistic background, in contrast to the creative enabler.

‘Framer’: The person provides a certain framework. The disabled artists are free to create their artistic work within a given (artistic) structure.

‘Coach’: The person serves as an artistic adviser. In the theatre, this position is often coincident with the dramaturge’s role, but it might be an artist’s production in any artistic discipline. This is coincident with Meine Damen und Herren in Hamburg, when external artists act as coaches.

‘Artistic collaborator’: In this case, artistic collaboration between different artists on the same level. A best-practice example is the Berlin-based theatre company Theater Thikwa.

‘Filter’: Last but not least, the concept of the ‘filter’ is very common in theatre with and by persons with cognitive disabilities. It is similar to the usual processes of devising theatre; a director lets the disabled artists improvise and shapes and filters their creative work. According to Prendergast and Saxton ‘key to applied theatre facilitation is the recognition that the community participants – both actors and spectators – hold the knowledge of the subject under investigation, whereas the facilitator holds the knowledge of the theatre form’ (Citation2016, 18). The disabled artists obtain a large share of authorship, since the work is often based on her or his biography or the physical particularity of the performer, but the decision about what is presented on stage is still taken by the non-disabled artist.

Using this model of task division as a working model to analyse different theatre or even dance works, enables the description of all creative processes within this spectrum of roles. There is no ‘either or’, good or bad, and there are many variations. Sometimes two positions are combined. In the famous production Disabled Theater by Theater HORA and Jerôme Bel, for example, the choreographer Bel simultaneously worked as a framer and filter. The disabled performers obtained authorship within a very clear artistic setting; the artistic framework was set by the choreographer, who also finally shaped and filtered the performance.

‘Freie Republik HORA’ – an experiment

In what follows, I will use Theater HORA’s long-term performance project Freie Republik HORA (Free Republic HORA) as a case study to investigate the tensions within this complex field. The project Freie Republik HORA is perhaps the most radical example for these new developments.

Theater HORA is the first, and still the only, professional theatre company with and by persons with cognitive disabilities in Switzerland. It was founded in Zurich in 1993 by the theatre pedagogue Michael Elber. Since then, they have realised more than 50 performances, performed in different countries, and since 1998 have collaborated with external directors and artists. The ensemble members of the company – currently 13 performers – are salaried and work as actors full time. Since 2009, Theater HORA also runs an actor training programme for people with cognitive disabilities.

Ever since the early days of the company, its artistic practice has been closely aligned with developments in theatre in neighbouring countries. A performance by Theater Thikwa in Berlin (Im Stehen sitzt es sich besser, 1990) inspired the beginning of Theater HORA’s artistic approach; the performance inspired Elber to devise his first theatre production with performers with cognitive disabilities with the aim of reaching a broader audience. This was the start of Theater HORA. The internationalisation of Theater HORA increased in 2007, when they created a biannual disability arts festival Okkupation in Zurich, which is connected with the partner festivals in different Swiss language regions.Footnote2 Theater HORA’s festival was directed and curated by the German festival director Andreas Meder and the dramaturge Marcel Bugiel, who facilitate international disability arts festivals in different German cities with a special focus on artists with learning disabilities. Since key figures like Marcel Bugiel work for different companies with learning disabled artists in Germany, Switzerland, and Belgium, it is no coincidence that the same issues – such as the ‘directional turn’ – arise in different places at the same time (Schmidt Citation2012).

The project Freie Republik HORA begun in 2013 and is, as I have argued in previous work, a continuation of a critical rethinking both of the disabled performer’s agency and audience responses in theatre with and by artists with cognitive disabilities. It started with the famous work Disabled Theater by Jerôme Bel and Theater HORA in 2012 (Schmidt Citation2015). In the course of this multi-step experiment, the ensemble members get the opportunity to realise their own artistic projects within a given structure. According to Michael Elber, the non-disabled artistic leader of the company, the aim is not only the self-reliance and maturity of the disabled ensemble members, but also the maturity of the audience, for whom experience and discussion of disabled performers work from an aesthetical perspective is enabled. After a period of collective creation (phase 1) and first self-directing experiments (phase 2), in the third phase of Freie Republik HORA six selected ensemble members are on track to realise their own directing projects. In 2015, all of the ensemble members created short artistic concepts based on interviews with the dramaturge Marcel Bugiel. An external jury of theatre experts, among them well-known artists, selected six of the concepts to be realised between January and July 2016. Sara Hess stages a musical Über Leben auf der Strasse (On survival/living on the streets). Tiziana Pagliaro creates an atmospheric happening with three male performers/dancers called Randen Saft Horror (Beetroot Juice Horror). Gianni Blumer shows his own version of the famous movie Hunger Games by inviting the audience to participate in his performance (Das Festessen der neuen Präsidentin von Hunger Games, The Diner of the new president of Hunger Games). In Nora Tosconi’s performance Zyklus (Cyclus), a series of images deals with her own biography. Frankie Thomas interprets the classical Räuber (Robbers) piece by Friedrich Schiller as a mixture of trash comedy and techno parade. Matthias Brücker’s performance Ich sage kein Wort (I say no word) is a theatrical game about love, sex, and violence.

In all three phases of Freie Republik HORA, Elber and his artistic collaborator Nele Jahnke give no feedback or instructions. They call themselves ‘assistants’ who facilitate the disabled director’s work. Each director has his or her own budget and can hire up to three external actors, costume or stage designers, or technicians. The time allowed for each work is one week, plus an additional preparation day. At the end of the rehearsal week, there is a public try-out. In all stages of the project, the audience responses are an important part of the experiment. Finally, all six performance projects were presented as a series in the experimental theatre venue Fabriktheater in Zurich in front of a broader audience.

Despite the great freedom, there are some basic rules, which are fixed in the guidelines of Freie Republik HORA though constantly modified in the course of the experiment. One constant rule is that violence and sexual assault on stage are prohibited, as well as the damage of another person’s property. The reinstallation of a director’s position in the third phase has been the result of the previous phases, as one of the ensemble members had taken over the director’s position during the collective creation process, and another performer articulated the desire to stage his own solo performance (Schmidt Citation2015). Freie Republik HORA is therefore a learning process for the Theater Company, which itself reconsiders its conditions of work within the experiment.

Using the spectrum of co-creation that I introduced earlier, in the first two phases of the project Elber and Jahnke are the ‘organizers’ who organised the working space. In regular ‘consultation-hours’ they were available to facilitate the ensemble members’ demands. In phase 3, Gianni Blumer asked Elber and Jahnke to invite the famous Hollywood actress Jennifer Lawrence to join his project on Hunger Games, Nora Tosconi wants a water basin on stage, and Matthias Brücker needs two wooden houses. But, in contrast to the two previous phases, in phase three Elber and Jahnke’s roles go beyond creative enabler; they intervene artistically as ‘framers’. The significant difference is that, based on the previous two phases, they now have designed one individual rule, or condition, for each director. Sarah Hess has to deal with around 20 strollers on stage. Tiziana Pagliaro is invited to use 100 white shirts and 100 bottles of beetroot juice. Frankie Thomas’ condition was to use Schiller’s Räuber (Robbers) piece, and Gianni Blumer has to include 50 persons in his performance. According to Jahnke and Elber, the intention of this individual obstruction is to broaden the director’s artistic spectrum by challenging their binaries. Sarah Hess is supposed to ‘take the room’ by having to deal with the strollers. Some obstructions are based on intuitive ideas, such as the beetroot juice. Each director finds his or her own way to deal with this obstruction. Matthias Brücker is not allowed to work with his girlfriend, the company member Tiziana Pagliaro, who has been the focus of his previous artistic works. As a result, he creates a piece called Ich sage kein Wort (I say no word), dealing with Tiziana’s life story, but without naming her in the piece. Sarah Hess said that the strollers helped her as a starting point, as it had been difficult to start without neither a text nor a given subject.

As in the previous phases, Jahnke and Elber do not give any feedback as coaches. The radical approach of the experiment is that, in contrast to many other projects by directors with cognitive disabilities, they do not filter or shape the work. This makes the final decision about what happens on stage, unless she or he delegates the decisions to someone else.

Directing as a collective process

Nevertheless, the tasks of the director are shared among the different participants. With regard to the different functions of directing, the responsibilities are shared among the people involved in the theatrical process.

Conception

The experimental concept Freie Republik HORA was designed by Michael Elber, Nele Jahnke, and Marcel Bugiel. It was they who set the rules, including the fifth obstruction, and the working conditions such as the budget and rehearsal time. Within this framework, the HORA ensemble members create their own performances according to their own ideas. Elber and Jahnke are also responsible for supervision of the guidelines. They make sure that the rules are respected, including the ‘self-monitoring’ of their own roles as ‘assistants’ who have to minimise their influence. In the first phases of Theater HORA, they transcribed the documented rehearsals and audience discussions and highlighted the moments when they broke their own rules, such as their interventions during an audience discussion. The self-audition which is part of the experiment is coincident with what Sheila Preston calls ‘critical facilitation’ in Applied Theatre practices: ‘A critical facilitation practice will inevitably engage with this challenge by problem-posing its own practice, uncovering the complexity of the dynamics of facilitation and seeking to understand the power relations that exist within and beyond a workshop’ (Citation2016, 4). In the course of Freie Republik HORA Nele Jahnke’s and Michael Elber’s behaviour changes because of the greater awareness about the impossibility to be ‘neutral’. The guidelines as the core concept of Freie Republik HORA raise a central issue within the project; the negotiation between social/structural and artistic obstructions or, in a broader framework, the necessity of obstructions in the art-making process. In the rehearsal space as both an aesthetic and social space, different logics and rules intertwine, as both influence the resulting art work. In the same way, directing is both a social and artistic process.

Matthias Brücker, an ensemble member with Down’s Syndrome is regarded as the ‘rebel’ of the HORA ensemble. During the rehearsal week of his project Ich sag kein Wort, he provokes his performers by creating a permanent casting situation. Over the first few days he lets the performers improvise on the subjects’ sexuality, violence, and love. After a few seconds, he stops the scene and commands the next performers to enter the stage. By phase 2, his direction had provoked the performers who got more and more annoyed by rehearsal methods! In phase 2, Elber intervened because he wanted to protect the actors – a decision he later regretted. Elber explained:

Matthias wanted to create a chaos. And because of my intervention […] it was no chaos from the very beginning. I made an order by asking him if he cannot tell his actors what they are supposed to do. If he had continued it the way he wanted to do it, he had reached what he wanted: insecure actors, who are having issues.

In the course of the third phase of the project, the question of which rules are given in a theatrical process arises. Is the prohibition of violence on stage an intervention, or is it a normative projection on the disabled director? Freie Republik HORA pulls into question, which kinds of work are directors with cognitive disabilities supposed to create? And which kind of work is not wanted or desired. The guidelines of Freie Republik HORA – such as ‘no violence’ or ‘no destruction of other’s property’ – are a kind of protective structure. Similar to Applied Theatre practices, the facilitators create a ‘safe container’ (Prendergast and Saxton Citation2016, 17). Artistic creation, however, is characterised by the necessity of a risk. On the one hand, orders can serve as a vehicle to break the rules, on the other, orders can be disabling in themselves, as they regulate the creative process. Herein lies one of the principal paradoxes of the experiment. In line with the order of Freie Republik HORA, the breaking of rules and the discovering of new thinking are welcomed by the inventors of the concept. At the same time, the order – the ‘Regelwerk’ (guidelines) – permanently performs itself during the process.

Organisation of working context

The organisation of the working context is significant as it is constituted by the factor of time. Assistants often tell directors, ‘It’s your time’ in the course of the rehearsal week. Similar to the ‘concept’, the overall time slot of a week, which is quite unusual for theatrical productions, is given by Elber and Jahnke. Time management is a fundamental element within each directing project. Whereas some directors delegate the responsibility to one of the assistants, others start and make breaks exactly at the same time every day.

According to Anne McDonald’s concept of ‘crip time’, the temporality of disabled people can vary, like their individual sense of timing (Kuppers Citation2014). For some directors one week might be too short, others would have had finished sooner. The director Nora Tosconi prepared an exact schedule of the week, which she presented to the ensemble members on the first day of her project. Tiziano Pagliaro, a director with Down’s Syndrome, structured her rehearsals exactly. Each morning the performers watched Horror movies until noon, afterwards there was a lunch break until 2 p.m. and then she rehearsed her performance from 2 to 4 p.m. Whereas some directors get more nervous as the premiere approaches, Pagliaro did not feel any (time) pressure. Different economies of rehearsing can be observed. According to Matzke (Citation2010), each rehearsal process can be divided into two phases: the ‘open investigation’ and the ‘target-oriented work, which is focused on the premiere’ (Citation2010, 165). Both phases are characterised by two different approaches in terms of the economy of time. The first one is ‘research driven’ and characterised by breaks, cracks, and interruptions. The second is linear and aimed at the premiere. Using this perspective, one can see that the HORA directors follow different approaches: Nora Tosconi and Tiziana Pagliari represent the two opposites.

The given time slot makes a great impact on the artistic results. During Gianni Blumer’s rehearsals for his Hunger Games re-enactment, some of the disabled performers struggled with the text. Most of the six performances of Freie Republik HORA (phase 3) do not use much text. This might be typical for theatre with and by artists with cognitive disabilities, as they do not place text as primarily important, instead using other means. Nevertheless, it would be interesting to see if a longer rehearsal time led to a different aesthetics in some projects. Further, one of the research team observed the adoption of former characters, music, or other materials and ideas from previous works by the theatre company. I argue that the HORA ensemble references a shared memory, as they are used to working together as an ensemble. According to Matzke (Citation2010), the rehearsal room is always a space of collective memory. The German Theater Studies Scholar Weiler (Citation2006) states that each actor or actress develops in the course of her/his career a so-called third body (Citation2006, 67). Apart from the body of the actor as person and the body of the role or character, all the roles that they have taken during their artistic biography are present and constitute a third body. The HORA directors tend to address this third body as well as the shared Theater HORA memory when they cast their ensemble colleagues. Freie Republik HORA is therefore nothing less than a critical reflection of the HORA ensemble which performs itself – the hierarchies, love stories, and conflicts among the ensemble members and the HORA institution, as well as the artistic history and aesthetics over the period of 25 years. In this context, the issue of time might also play a role. According to the performer Remo Beuggert, he ‘recycles’ his figure from another HORA performance in Gianni Blumer’s show, because he would have needed more time to create and embody a completely new character.

Reflection and observation

The reflection and observation – that is, the position of an external eye in Freie Republik HORA – is delegated to the audience. The public Try Outs, followed by audience discussion moderated by the performers, are a significant part of the project. The audience is supposed to express their opinion without any ‘disability bonus’, because this is the only feedback that the directors get. As a consequence the audience is in a double role, serving as both ‘coaches’, from a process-oriented approach, and judges of the performance as an artwork from a product-oriented approach. This division between internal and external feedback, process-oriented and product-oriented approaches, and artistic feedback and coaching during the rehearsal process and audience development is another contradiction within Freie Republik HORA. Workshops with students from the Zurich University of the Arts aim to foster a feedback culture within the company as well as in the audience discussions by creating playful, non-verbal models of communication.

Apart from this outsider perspective, the directors take on the tasks of observing and giving feedback during their rehearsal weeks. In Frankie Thomas’ project Räuber (Robbers), the lack of reflection and observation from the director provoked discussion among the team. Thomas, a very experienced performer with Down’s Syndrome, rarely gives his performers any feedback or direct instructions. Sometimes he seems not to observe the actions on stage, but to be completely occupied with the music, which is the dominant element on stage. The actors and actresses play against the sound and fight for the director’s attention. On the second day, the performers ask the director to rehearse without the music and want him to discuss the piece and their roles. As the researcher, and so unable to articulate my opinion, I am asked several times, particularly by the external performers: ‘What do you think about it?’ The missing instructions and observation create the impression of an absence; the absence of the director. Yet simultaneously the director is hyper-visible as he sits on a ‘DJ console’ at the edge of the stage dancing to the techno music. From time to time he even enters the stage and dances – as the focus of the show.

Among the research team we discuss at what point do we start to construct a director’s position? Where does directing begin when fundamental tasks such as observation and reflection appear to be missing? After all, this is a question of communication between the director and the performers. New ways to communicate have to be developed, especially if the disabled director has no prior knowledge of the performers. This leads back to the question of the time necessary to create a working relationship and to find ways to interact constructively, particularly in inclusive theatre settings.

Correction

The correction is the most radical aspect of Freie Republik HORA, as this is so often the responsibility of the not disabled director. In Freie Republik HORA, the disabled director – and the team if she or he has chosen to share this responsibility with them – has the final say without any restrictions. This is all the more significant because all other functions are at least partly not the director’s duty. Also from a ‘disability aesthetics’ perspective (Siebers Citation2010), this is central, as the disabled directors perspective creates new theatrical forms and aesthetics instead of orienting towards normative conventions of theatre or dance.

Conclusion

As a theatrical experiment, Freie Republik HORA raises many questions that are essential for the work by directors/choreographers with cognitive disabilities. How much ‘framing’, or conception, is necessary? The fact that the facilitators Michael Elber and Nele Jahnke do not ‘filter’ the work forms a significant contrast to other works with and by theatre-makers with cognitive disabilities. It also contrasts strongly with many other applied theatre practices. The knowledge of the theatre form is not given or guaranteed by the facilitator’s role. The HORA ensemble members, however, are the experts – as artists. The assistants create a safe space by setting some basic rules; but the responsibility for the creation is attributed to the disabled artists.

Nevertheless, the elimination of the framing does not necessarily mean that the facilitator does not influence the artistic outcome. On the contrary – the spectrum from the organiser to the filter, which I elaborate in this article, is a useful tool in order to better understand the different key points of intervention. By setting a rather strong framework in phase 3 – such as the limited rehearsal time and the individual obstruction for each director, – the assistants still obtain a huge amount of authorship.

Freie Republik HORA also explores the directing process as a matter of communication. If communication is the key, how can we develop new tools to facilitate interaction between disabled directors with differently abled performers? During the third phase of Freie Republik HORA, the external performers (without disabilities) often said they would have needed more time for conversations with the director in order to better understand their ideas.

Finally it must be asked: Which new working models have to be invented for each individual director? Interestingly, new divisions of work are developed during the rehearsal weeks among the ensemble. Noha Badir, an ensemble member with Down’s Syndrome, serves as a light technician in one of the projects. Remo Beuggert, another performer with a learning disability, takes over responsibility for the music in several projects, and assists Sara Hess as a dramaturge. The ensemble members not involved as performers in a project work as assistants or are responsible for parts of the research project, such as the video cabin. Still it must be asked: Where are the dramaturges, light and stage designers, costume makers, theatre music composers, etc. with cognitive disabilities?

The evaluation of the interviews and visual material is supposed to open up new perspectives on how the directors experienced their first theatre projects, and which conditions they request.

Freie Republik HORA is about the order of theatre and theatrical creation. Is it OK when the director performs in his own piece? Does theatre need to have a story? What is a story? These are just a few of the questions that have been raised by HORA ensemble members at the interim evaluations after each piece. These issues are not only central to theatre by artists with cognitive disabilities, but to every theatre project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Yvonne Schmidt, PhD, is a Senior Researcher and Lecturer at the Zurich University of the Arts and head of the SNSF-research project ‘DisAbility on Stage’. She is the co-convener of the IFTR Working Group ‘Performance and Disability’.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Denis Seidel’s performance Ordinary Girl was performed at the No Limits platform in Berlin in November 2015 and afterwards because of the positive audience responses in the regular festival programme.

2. The other festivals are ‘wildwuchs’ in Basel, ‘Out of the Box’ hosted by the company Danse Habile in Geneva, ‘Community Arts Festival’ hosted by the company BewegGrund in Bern, and since 2012 ‘Orme’ in Lugano, hosted by the company DanzAbile in the Ticino. Each festival has its own profile and history. The festivals are connected through MiGROS culture percentage's project IntegrART, the most important private arts foundation in Switzerland.

References

- Achtman, Michael. 2014. How Creative Is the Creative Enabler? Alt.theater 11/3.

- Calvert, Dave. 2009. “Re-claiming Authority: The Past and Future of Theatre and Learning Disability.” Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theater and Performance 14 (1): 75–78. doi: 10.1080/13569780802655798

- Carlson, Licia, and Eva Feder Kittay. 2009. “Introduction: Rethinking Philosophical Presumptions in Light of Cognitive Disability.” Metaphilosophy 40: 307–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9973.2009.01609.x

- Hargrave, Matt. 2015. Theatres of Learning Disability: Good, Bad, or Plain Ugly? New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jackson, Shannon. 2011. Social Works: Performing Art, Supporting Publics. New York: Routledge.

- Kittay, Eva Feder. 2011. “The Ethics of Care, Dependence, and Disability.” Ratio Juris 24 (1): 49–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9337.2010.00473.x

- Kuppers, Petra. 2011. Disability Culture and Community Performance. Find a Strange and Twisted Shape. London: Palgrave.

- Kuppers, Petra. 2014. “Crip Time.” TIKKUN Magazine 29 (4): 29–31.

- Matzke, Annemarie. 2010. “Die Kunst nicht zu arbeiten. Die Inszenierung künstlerischer Praxis als Nicht-Arbeit bei Bertolt Brecht und Heiner Müller.” In Nicht-Arbeit. Politiken, Konzepte, Ästhetiken, edited by Jörn Etzold and Martin Schäfer, 156–171. Weimar.

- Matzke, Annemarie. 2015. “Das Theater auf die Probe stellen. Kollektivität und Selbstreflexivität in den Arbeitsweisen des Gegenwartstheaters.” [ Collectivity and Self-reflexivity in Contemporary Theatre]. In Arbeitsweisen im Gegenwartstheater [ Working Models in Contemporary Theatre], edited by Géraldine Boesch, Mathias Bremgartner, Beate Hochholdinger-Reiterer, and Christina Kleiser, 15–33. Berlin: Alexander Verlag.

- McKenzie, Jon. 2001. Perform or Else. From Discipline to Performance. London: Routledge.

- Poppe, Frederik. 2012. Künstler mit Assistenzbedarf. Eine Interaktionsstudie [ Artists Who Need Assistance]. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- Prendergast, Monika, and Juliana Saxton, eds. 2016. Applied Theatre. International Case Studies and Challenges for Practice. Bristol: Intellect.

- Preston, Sheila. 2016. Facilitation. Pedagogies, Practices, Resilience. London: Bloomsbury.

- Schmidt, Yvonne. 2012. “Theater und Behinderung.” [ Theatre and Disability]. In Bühne und Büro. Gegenwartstheater in der Schweiz. Theatrum Helveticum 13 [ Stage and Office. Contemporary Theatre in Switzerland], edited by Andreas Kotte et al., 357–376. Zürich: Chronos.

- Schmidt, Yvonne. 2015. “After Disabled Theater. Authorship and Agency in Freie Republik HORA.” In Disabled Theater, edited by Frank Gerber, Andreas Kotte, and Beate Schappach, 227–241. Zürich: Diaphanes/Chicago University Press.

- Schmidt, Yvonne. 2017. Ausweitung der Spielzone. Experten – Amateure – Darsteller mit Behinderung. Zürich: Chronos.

- Siebers, Tobin. 2010. Disability Aesthetics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Siebers, Tobin. 2012. “Un/Sichtbar. Observationen über Behinderung auf der Bühne.” In Ästhetik versus Authentizität? Reflexionen über die Darstellung von und mit Behinderung, edited by Imanuel Schipper, 16–32. Berlin: Theater der Zeit.

- Weiler, Christel. 2006. “Nichts zu inszenieren.” In Wege der Wahrnehmung. Authentizität, Reflexivität und Aufmerksamkeit im zeitgenössischen Theater, edited by Erika Fischer-Lichte, Barbara Gronau, Sabine Schouten, and Christel Weiler, 58–71. Berlin: Theater der Zeit.

Resources

- Swiss research project “DisAbility on Stage”. https://blog.zhdk.ch/disabilityonstage/.

- Theater HORA, Zurich. http://www.hora.ch.

- Companie BewegGrund, Bern. www.beweggrund.org.

- Wildwuchs Festival, Basel. www.wildwuchs.ch.

- Danse Habile, Geneva. www.danse-habile.ch.

- Teatro DanzAbile and ORME Festival, Lugano. www.teatrodanzabile.ch.

- IntegrART. www.integrart.ch.

- No Limits Festival, Berlin. www.no-limits-festival.de.

- Festivals in Germany. http://lebenshilfe-kunst-und-kultur.de/aktuelles.php.

- Theater Thikwa, Berlin. www.thikwa.de.

- Meine Damen und Herren, Hamburg. http://www.meinedamenundherren.net.

- Biennale Out of the Box, Geneva. biennaleoutofthebox.ch/