ABSTRACT

Menstruation is a ‘taboo’ subject in many cultures and its effect on women’s participation in sport and physical culture in western societies is under-researched. This study examines the effect of menstruation and premenstrual syndrome (PMS) on habitual participants in adventurous activities through the voices of women. It transcends the social/biological divide using a theoretical framework to ascertain the personal, socio-cultural and practical constraints and enablers to participation. In a survey to explore women’s lived experiences (n = 100), 89% of respondents noted that their participation is affected by menstruation/PMS. The dominant constraints to participation in adventurous activities were related to practical challenges of hygiene and waste disposal for managing menstruation. Rich qualitative data provide evidence for the negative and emotional responses of women to ‘missing out’ on adventurous activities with the majority of concerns about their performance in socio-cultural contexts related to personal anxieties. Some women commented on their belief in being a role model in professional work encouraging open discussion around menstruation and enabling more women and girls to take part in adventurous activities. Key practical recommendations for practice are suggested in respect of provision of toilet facilities where possible and biodegradable sanitary products. Raised awareness amongst leaders and educators, particularly men is important so that they might identify strategies to manage the constraints facing women and girls and enable more inclusivity and greater participation in adventurous activities.

Purpose and rationale

Previous research on menstruation and premenstrual syndrome (PMS) in western cultures has largely focused on the effects of menstrual function on performance, or vice versa. Even in studies purporting to explore the factors affecting women and girls’ participation in adventurous activities, the impact that menstruation has and the challenges of menstrual management in outdoor environments are often not researched, disclosed or reported. However, there have been calls for new ways of thinking and theorising the complex relationship between the biological and social in sport and physical culture (Thorpe, Citation2012). A more transdisciplinary approach may help us to move forward towards more understandings of the body in adventurous activities. A greater understanding of the issues that women face when participating or considering participation in adventurous activities is also needed to inform outdoor leaders and educators so that they might identify strategies to manage the constraints facing women and girls (Botta & Fitzgerald, Citation2020). In a time of much focus on the key agendas of inclusivity and accessibility, understanding and mediating where possible, the impact of menstruation on participation is crucial.

This research examines the impact of menstruation on participation in adventurous activities through the voices of women participants who experience menstruation and/or PMS, who are not elite performers. It explores the emotional and physiological feelings of women and the extent to which these affect their experience when participating in adventurous activities.

Key terminology

The menstrual cycle has long been a taboo topic in many communities (Buckley & Gottlieb, Citation1988; Gottlieb, Citation2020). The term refers to the physical, psychological and hormonal changes fertile individuals experience for the purpose of sexual reproduction, involving menstruation (also known as periods or menses), and sometimes premenstrual syndrome (PMS) (Gosselin, Citation2013). Menstruation is the shedding of the uterus lining and can last between two and seven days, whilst PMS refers to symptoms experienced leading up to menstruation, for example, cramps and mood swings (Gosselin, Citation2013).

The length of the menstrual cycle varies between 20 and 45 days in adolescents, decreasing to between 24 and 38 days with increasing maturity (Madhusmita, Citation2015). Menstrual flow results in an average blood loss of 30 mL in an adult. However, many women and girls experience abnormal ovulatory cycles or luteal phase defects such as menorrhagia (excessive blood flow and/or lasting longer than seven days), oligomenorrhea (infrequent periods) complete amenorrhea (absence of menstruation), or anovulatory cycles (where ovulation does not occur). Normal and abnormal cycles and flow can cause pain, discomfort, fatigue, bowel issues and mood swings although some women may have few if any of these symptoms. Managing menstruation necessitates hygiene, time, privacy and usually expenditure to purchase sanitary products.

Relevant past research

The majority of studies on menstruation from a western perspective in sporting contexts focus on biological changes affecting exercise performance. Disruptions in the hormonal balance may result in altered muscular strength, endurance capacity, body temperature and blood flow. Exercise load may lead to irregular or a complete absence of menses, which has implications for reproductive health (Dawson & Reilly, Citation2009). Exercise-associated amenorrhea may increase the risk of mineral loss and bone health, and disordered eating (Thorpe, Citation2012). Kinesiologists have shown that half of exercising women (those who perform regular purposeful exercise at greater than 55% of maximal heart rate for more than two or three hours a week) experience subtle reproductive disturbances and a further third present with severe menstrual disturbance or amenorrhea (De Sousa et al., Citation2010). Mood states of anxiety, anger and confusion may be higher in the menstrual phase compared to other phases of the cycle (Ghazel et al., Citation2020) and affect motivation and performance.

From a socio-cultural perspective, it would seem that there has been a limited increase in menstrual consciousness of the wider public particularly those who do not identify as female or who are not physically active. Menstruation has been referred to as ‘the last taboo in sport’ (Dykzeul, Citation2016) and although an ‘embodied’ experience (Moreno-Black & Vallianatos, Citation2005) public awareness might not have moved beyond the ‘peculiarly mapped landscape of menstrual etiquette where beliefs are based on superstition, shame and sexual self-consciousness’ (Houppert, Citation1999, p. 8). Limited research on boys’ and mens’ views of menstruation illustrates mainly negative, stereotypical and uninformed views. Peranovic and Bentley (Citation2017) reveal the relational, educational and socio-political contexts in which male attitudes are created and suggested that there could be more effective reproductive health education programmes and better communication between parents and children to provide a more balanced view of menstruation amongst boys and men.

In male-dominated sporting disciplines such as adventure racing, ideas of unbalanced power relations and female body deficiency have pushed individuals to hide their menstruation to emulate the ‘masculine sporting body’ and to subjugate the negative effects that women feel that their periods have on performance (Dykzeul, Citation2016). Moreno-Black and Vallianatos (Citation2005) researched young women athletes’ perceptions of, and attitudes to menstruating when participating in sport, and their experiences and coping strategies. They called for more practical provision such as access to toilets and modifications to sportswear to alleviate worry and stress that can affect performance. In the context of sport, these studies imply that administrators, coaches and athletes themselves need to examine their own attitudes about menstruation and how they impact programmes, policies, coaching and performance (Moreno-Black & Vallianatos, Citation2005).

Previous studies of (non-elite) women’s participation in adventurous activities have focused on social-cultural influences such as education, time, finance and family commitments (Doran, Citation2016; Little, Citation2002; Wharton, Citation2020). Most of this research focuses on participation on a daily basis without overnight stays but there is more literature specifically addressing challenges with managing menstruation in extended ‘backcountry’ experiences from New Zealand (Lynch, Citation1996) and the U.S. (Botta & Fitzgerald, Citation2020; Burni, Citation1995; Byrd, Citation1988). Earlier papers seek to dispel the myth that women with periods may be attacked by bears due to ‘folk wisdom’ that pheromones (hormonal scents), not blood, attract bears.

Similarly, the management of menstruation in respect of health and hygiene issues and the presumption of male dominance are the two main themes reported by women (n = 565) completing the 220-mile John Muir Trail in the U.S. (Botta & Fitzgerald, Citation2020). They call for more research that looks at the ways that menstruation may constrain participation and/or women’s enjoyment and comfort in outdoor recreation.

Menstruation as a factor influencing participation in adventurous activities is rarely mentioned in the literature. This could be because it is not in the consciousness of authors who may be male or feminists who see it as an irrelevance, even though more recently there has been more overt acknowledgement of the issues surrounding it such as ‘period poverty’ (ActionAid, Citation2021), ‘menstrual equity’ in the U.S. (Periodequity, Citation2021) and stigma (Girlguiding UK, Citation2021).

Theoretical framework

Most feminist theorising downplays the biological process, focussing on the socio-cultural aspects of lived experiences. ‘When menstruation is stripped of its social, cultural and political meanings, the diversity of women’s experiences with, and perspectives on menstruation, are neglected’ (Johnston-Robledo & Stubbs, Citation2013, p. 1). A theoretical framework that transcends the social/biological divide would support new ways of thinking to conceptualise the complex relationships between the biological and social in sport and physical culture (Thorpe, Citation2012). A dialogue across the social and biological sciences with reflexive participants conscious of their own ontological, axiological and epistemological assumptions (Thorpe, Citation2012) would enable the voices of female participants about the biological dimensions of their experiences to become less marginalised in socio-cultural scholarship (Birke, Citation2003). Academics and practitioners must acknowledge the socio-cultural, biological and contextual importance of menstruation (Thorpe et al., Citation2020).

This research employs the theoretical framework (Wilson & Little, Citation2005) used by Doran (Citation2016) on the constraints affecting women’s participation in adventure tourism: personal, socio-cultural and practical. Constraints are defined as factors that inhibit people’s ability to participate, to spend more time doing so, to take advantage of available opportunities or to achieve their desired levels of satisfaction (Jackson, Citation1988). The fundamental concept as applied to this research is that people have the freedom and desire to participate in adventurous activities but that certain factors may hinder that freedom, desire and participation (Raymore, Citation2002). Crawford and Godbey (Citation1987) proposed ‘intrapersonal, interpersonal and structural’ factors as constraints although this framework focuses on participation and has limited application in respect of benefits (Kono & Ito, Citation2021). Furthermore, Wilson and Little’s (Citation2005) framework has been applied to understanding the behaviour of certain social subgroups and demographics such as women and its categorisation better addresses the complexities of the identified biological and social constraints experienced during menstruation.

In respect of menstruation, as in adventure tourism, some of these constraints may be experienced simultaneously and may be interconnected as they can inform and influence each other. Women may also experience different constraints at different stages in their participation and constraints linked to menstruation may be compounded by a multitude of other factors.

Personal constraints refer to self-perceptions, beliefs and attitudes (Wilson & Little, Citation2005) and are the least reported in terms of those affecting participation. With respect to menstruation, these may be indistinguishable from socio-cultural and practical constraints in so far as they can include self-doubt, fear and the perception of being unadventurous (Doran, Citation2016) and may be connected with biological manifestations connected to physical activity both physiological and emotional. However, women’s feelings about adventurous activities and spaces being ‘masculine’ (Little & Wilson, Citation2005) may derive from challenges such as menstruation experienced only by women.

Socio-cultural constraints may include a ‘subtle kind of harassment’ related to the perception by women feeling inferior if participating with males who are physically more competent (Bialeschki & Henderson, Citation1993, p. 39) reinforced by often intentional male stereotyping (for example in the media). Women may feel constrained by menstruation in terms of the activities they feel comfortable to pursue and the facilities provided or not provided for them, and exhibit these feelings by choosing not to participate, participating reluctantly or in a limited way.

Practical constraints are perhaps the most dominant in respect of menstruation. ‘Menstruation is not a state in which the body’s function becomes visible to the public, and thus open to public scrutiny and comment’ (Moreno-Black & Vallianatos, Citation2005, p. 51). Managing menstruation outdoors and in remote settings is influential to participation as well as the impact of associated symptoms physical and emotional.

Menstruation shapes women’s lives and brings into focus particular questions for them and for other genders and sexualities. This plurality of interest aligns most closely to a post-positivist stance where multiple perspectives are felt by menstruating participants in adventurous activities and where cause and effect is difficult to ascertain and subject to probability (Creswell, Citation2017). Determining the essence of women’s experience of menstruation by a group of individuals who experience it through both subjective experiences (feelings) and objective experiences (biological) aligns this research most closely with phenomenology (p. 76). It brackets experiences from women who participate in adventurous activities and who menstruate and derives themes to inform significant statements about their lived experiences (Moustakas, Citation1994) that are interpreted with reference to the theoretical framework. However, the methodology deviates from true phenomenology in that women’s experiences are derived from quantitative as well as qualitative data, with the latter being espoused from free text statements rather than interviews (but see Braun et al., Citation2021 below). Additionally, they are not expected to culminate in a composite description of menstruation and its effect on participation in adventurous activities for all individuals.

This research addresses the gap in research on the impact of menstruation on the participation of women in adventurous activities. It listens to the voices of women themselves on an emotional and practical level about the extent to which their experiences influence their participation. The research responds to the call for a more transdisciplinary approach across social and biological theorisations and makes recommendations for increasing participation sensitively that should have ramifications beyond habitual adventure participants.

Method

The approach used to explore women’s lived experiences of menstruation employed an online survey method, deployed on SmartSurvey platform via multiple Facebook groups linked to adventurous activities. The research was approved via the internal ethical processes of the University of Cumbria.

The questionnaire allowed respondents to remain anonymous, which was deemed appropriate to this sensitive area of research and comprised 13 questions in three sections: age (classes), current or past frequency of menstruation and types of adventurous activities participated in; experience and symptoms of menstruation/PMS; and effects of menstruation/PMS on participation in adventurous activities. Nine out of twelve questions were closed questions including multiple choice answers with three more open questions allowing respondents to state the reasons for, and feelings and experiences about participation or non-participation.

Online surveys facilitate relatively easy access to geographically dispersed populations and are affordable to deploy. Braun et al. (Citation2021) argue that qualitative online survey questions can provide data for, ‘ … nuanced, in-depth and sometimes new understandings of social issues’ (p. 641) and do not need to be followed up with interviews. They have the potential to capture a range of voices and sense making and this wide scope mitigates the risk of a spokesperson or limited ‘within group’ voices for the demographic. Its use in this research would seem the appropriate tool to gather data from a range of women concerning their views, experiences and material practices on the impact of menstruation on participation in adventurous activities in both personal and professional contexts.

Deployment of the questionnaire resulted in responses from over 200 individuals of varying ages and interests. Due to the licence requirements of the survey platform, only the first 100 responses were visible for analysis by the researcher. The interest in responding, however, did indicate that many women wanted their voices to be heard on this subject.

The analysis of qualitative and quantitative data followed the ‘convergent’ design for mixed methods (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). A basic descriptive analysis of the quantitative data was undertaken from the data collated on Microsoft Excel to report measures of proportion and variation and is presented in percentages, and as absolute numbers on bar graphs for sections one and two. The qualitative data were coded whereby the open responses were categorised manually with an ‘in vivo’ (language of participants) term and collapsed into broad themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). To optimise the intellectual and conceptualisation processes required to transform the data and enhance credibility, two researchers analysed the data (Nowell et al., Citation2017). Themes can reflect similarities in meanings, frequency of appearance within the data, correspondence and causation (Saldaňa, Citation2009). Open qualitative comments were recorded through this thematic analysis around the reasons for participation or non-participation in adventurous activities.

Results

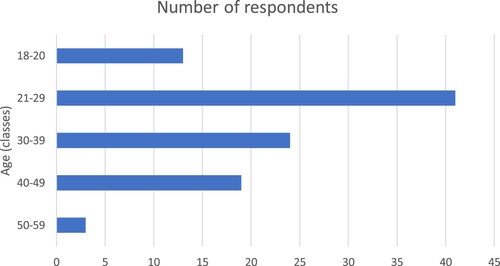

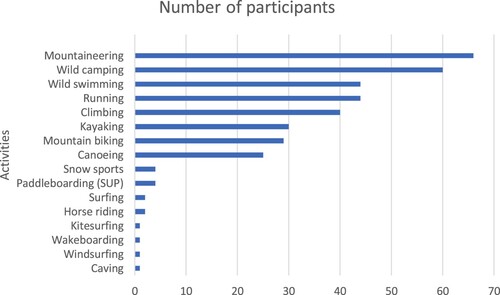

The distribution of respondents’ ages is shown in . The majority of respondents were women aged 21–29 (41%). Respondents participated in a range of adventurous activities with mountaineering and wild camping being the most popular (n = 66 and n = 60 responses respectively – multiple answers permitted). Running and wild swimming were the next most popular activities (n = 44 each) (see ). Sixty nine per cent of women menstruated monthly, with a further 28% menstruating either bimonthly (14%) or every few months (14%). One respondent menstruated several times in a month and the others only a few times in a year.

Figure 1. Age distribution of respondents (impact of menstruation on participation in adventurous activities).

Figure 2. Participation in adventurous activities of respondents (impact of menstruation on participation in adventurous activities).

Practical constraints

The questionnaire asked about the degree of flow during menstruation as judged by the respondents. Fifty per cent stated that they had at some time heavy or very heavy flows, with a further 34% reporting a medium flow. Those reporting a light flow or spotting were in the minority (14%). Twenty six per cent of respondents indicated that the amount of flow varied from period to period.

I can have quite a heavy flow so having fear that I might bleed through my sanitary products and clothes is a big one! (Female participant N)

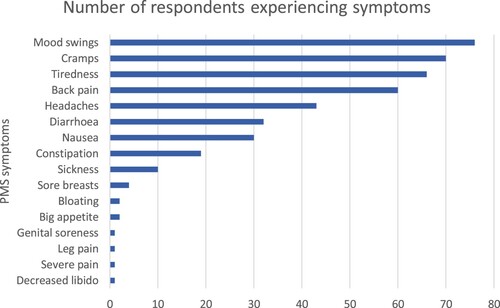

indicates the symptoms that women experience during PMS (multiple answers permitted) with mood swings, cramps and tiredness being the most predominant. Forty two per cent said that they take medication to relieve their symptoms with 30% stating that they did not. The remainder of respondents took medication sometimes.

I miss out on regular exercise during my period as my cramps are too painful. (Female participant Z)

When you’re trying to keep to a fitness schedule/routine or trying to improve in a certain sport, consistency is key. … I feel it would be much better if I didn’t have to battle with a monthly cycle of sleepless nights (due to overheating and cramps), pain, sensitivity, nausea, low energy etc. etc. But that’s just life as a woman, I guess:). (Female participant C)

Figure 3. Premenstrual symptoms (PMS) of respondents (impact of menstruation on participation in adventurous activities).

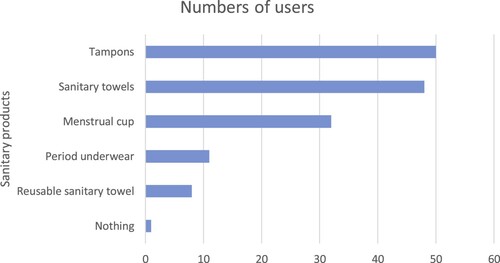

(multiple responses permitted) shows the range of sanitary products that participants in adventurous activities use. The most commonly used products almost in equal measure were tampons and sanitary towels. The responses indicated that participants may use more than one product at the same or different times.

Figure 4. Sanitary products used by participants of adventurous activities (impact of menstruation on participation in adventurous activities).

In respect of participation, 53% of women stated that menstruation/PMS had affected their participation in adventurous activities. A further 36% stated that their participation was sometimes affected. Only 11% of respondents noted that this did not affect their participation. Respondents were asked how often they had missed out on an adventurous experience due to menstruation or PMS, 16% stated ‘often’, 39% stated ‘sometimes’, 32% stated ‘rarely’ and for 13% it was never.

I have declined going wild camping many times due to feeling unable to be secure to wash, dispose of, stay private etc. I feared for overflowing and felt mood swings would impact my enjoyment and other people’s experiences with me. It made me feel that I lost out on something because I’m a woman. (Female participant T)

Last time I was on my period my friends went wild swimming a lot and I missed out on most sessions, which made me feel left out and as if my period was hindering my outdoor experiences but that I wasn’t able to control it. (Female participant BB)

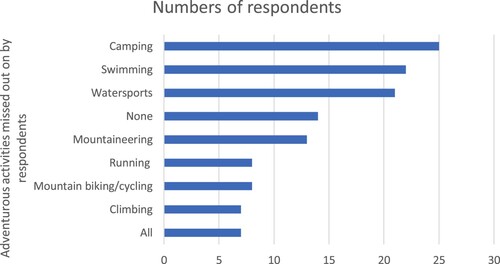

shows the activities that they missed due to menstruation/PMS with camping, swimming and watersports ranked first, second and third respectively of multiple responses. Fourteen per cent of women stated that they would not miss any activities because of menstruation. Eighty five per cent of those who responded to the question indicated that they would prefer to have toilet facilities available when undertaking adventurous activities although 15% stated that they would not and a further 29% did not make a response to this question perhaps indicating that they did not mind whether or not such facilities were provided.

Regular access to a bathroom with a sanitary bin would make a huge difference to participation. I would be far more likely to take part if I knew this was accessible. (Female participant K)

I’ve done so much on periods that I’m kinda just used to handling it outdoors now. (Female participant JJ)

Figure 5. Activities missed out on by respondents (impact of menstruation on participation in adventurous activities).

The reasons that women stated about feeling more comfortable if they had regular access to a toilet or sanitary bin whilst menstruating on a whole day or overnight adventurous activity such as canoeing, wild camping or hiking were dominated by the two themes of hygiene and disposal of waste products. Over 20 participants had concerns over personal hygiene due to the lack of clean water, worrying about not being able to wash their hands or in some cases menstrual cups, with a further seven commenting about needing privacy and feeling comfortable. A number of women referred to the issues of carrying out waste products, particularly during extended expeditions and environmental concerns if people did not do this.

To not have somewhere to dispose of or clean an item is distressing. You feel dirty and ashamed. You cannot keep dirty sanitaries on/in because of health risks and you certainly don’t want to keep them in your pocket. Even the idea of having a waterproof bag to store dirty items feels wrong and if you are with people, it’s an added stress for privacy issues. Staying clean and washed is essential to feel comfortable. (Female participant V)

The main hindrance is knowing that you can’t dispose of your waste products (what do you do with them if you can’t?). (Female participant DD)

It’s an environmental issue. Littering. (Female participant Y)

Some women commented about managing side effects/symptoms such as needing to defecate more regularly, leaking concerns and cramps.

Personal constraints

Another theme emerged about women coping with being outdoors ‘I can manage. It just needs planning really’ although there were other comments about other peoples’ awareness of the challenges women might face in this respect, ‘it would be nice for men to consider girls on periods though – I don’t think I’ve ever met a man who considered what it might be like for girls to pee outside’. Many of the respondents cited multiple reasons for why they would feel more comfortable with toilet access or why they just cope, ‘being near facilities doesn’t make it very wild’. Two respondents also pointed out that often facilities were unsanitary and that they would not use them anyway.

I find camping on a heavy period really unpleasant even if there are toilets because usually those toilets are not very private or clean. (Female participant H)

Often available facilities are really unsanitary and so I wouldn’t use [them]. (Female participant G)

The final question asked respondents to provide an example from memory of an experience or activity that they had to miss out on due to menstruating/PMS and how it made them feel. Seven respondents focused on memories of missing out on water activities, although another 15 cited a range of adventurous activities. Many women reported strong negative feelings and emotions around the notion of missing out on an activity: ‘upsetting’, ‘annoyed’, ‘deflated’ ‘singled out’, ‘sad’ ‘embarrassed’, ‘angry’, ‘disappointed’, ‘infuriating’ and ‘irritating’ were some of the terms used. Most feelings were focused on themselves although some wrote of their anger towards menstruation, being a woman, and the taboo nature of the topic, especially around men.

It made me feel almost irritated to be a person who menstruates and jealous of people who didn’t. It feels like something that could be fixed, not necessarily easily but it could be with some work. It needs to be less taboo and more talked about – it will encourage identifying females to take part more. (Female participant FF)

Out hiking in the mountains and with a group of men who mostly have no idea what women have to put up with sometimes. (Female participant T)

Some were concerned about having to change menstrual products outdoors and being seen by someone. Several women commented that the sanitary products could not cope with their flow either because there were no opportunities to change them frequently on activities, or that they resulted in leakage, meaning that they chose not to participate for fear and anxiety in this respect.

Socio-cultural constraints

The majority of comments about the reasons for non-participation or limited participation were about women’s concerns of the symptoms of menstruation/PMS and their effect on performance. ‘I’ve not been able to perform to my usual standards when climbing and hillwalking’. Women also compared themselves to others around them, ‘I regularly miss out on doing things with a group (mainly guys) as I know it will affect my performance, confidence and often my mood/enthusiasm’. However, there were also comments about the importance of female role models working in the outdoor sector to support women and girls who have less confidence in taking part in an activity at the time of their period.

I noticed that a lot of the young girls avoided coasteering. When asked, a lot of them said it was because they were menstruating. When I explained a little about how I cope with my periods, and how I recommend a way for them to discretely deal with the sanitary products after being on the water, a lot of them were happy to take part in the activity. They would have missed out otherwise! (Female instructor)

A summary of themes impacting participation or non-participation in adventurous activities is shown in . It is based on the constraint theoretical framework (Wilson & Little, Citation2005) but has been adapted to include enablers (in italics)

Table 1. Constraints and enablers for women’s participation in adventurous activities due to menstruation/PMS.

Discussion

The dominant constraints to participation in adventurous activities were related to practical challenges in relation to managing menstruation. Lynch’s (Citation1996) study found that the lack of opportunities to wash and be hygienic on multi-day activities had an impact on some participants’ enjoyment of outdoor activities and although enjoyment was not researched specifically in this project, our research did provide evidence of the negative feelings and emotions that women feel when they are unable to participate. The issue of odour causing embarrassment to some of Lynch’s participants was not mentioned in any of the responses in this research, suggesting that higher quality sanitary products are now available. The concerns expressed by these respondents about disposal of waste products in the outdoors mirrored Lynch’s study, with some women claiming in that research that they buried their menstrual products in the hope that they would decompose over time. Concerns about environmental degradation and littering were raised in this research and the women who mentioned waste disposal all talked about carrying out their used menstrual products with concomitant feelings connected with stigma and hygiene. Meyer’s (Citation2020) guide suggests carrying out used menstrual products or burning them in ‘ … an inferno of a fire to be immediately and completely consumed’ (p. 89) although if they contain any plastics, this could result in release of toxins.

The practical aspects of managing the biological effects of menstruation through the voices of many women were accompanied by feelings and expression of emotions about the personal and socio-cultural aspects of participation. In many cases, the differentiation between these themes were hard to discern with women commenting about how they felt that other people and society viewed their degree of participation and reasons for it with their own personal feelings and emotions around menstruation. This gives weight to disentangle any dichotomy existing between social and biological influences on participation (Thorpe, Citation2012). Indeed, one of the two dominant constraints for women in the backcountry of the U.S. in Botta and Fitzgerald’s (Citation2020) study was the gendered physical challenges, both practical and personal. Concerns about the effect of menstruation on performance and what other people will think about them, have synergy with the voices of women in sports contexts (Dykzeul, Citation2016).

In this research, there was not such a strong voicing of male dominance as from women who were undertaking a through hiking trail over several days (Botta & Fitzgerald, Citation2020). However, there were many comments about a feeling of the lack of awareness or understanding from others about menstruation/PMS and its symptoms, particularly by men and the embarrassment they felt in coping with their frustrations or hiding them. This supports research reported by Winkler (Citation2020) in wider contexts in respect of the tensions between ‘public’ and ‘private’ and ‘ … the feelings of embarrassment when publicly disclosing their menstrual status or shame when having to request menstrual products’ (p. 12). Some women working as outdoor professionals did comment on the support that they had given to enable young women and girls to participate more fully rather than avoid taking part in an activity during menstruation. They believed that they needed to act as role models to facilitate the participation of others and to guide them with advice. These leaders were working to dismantle the barrier of menstruation for women in outdoor leadership identified in a recent report on inclusivity in the outdoors (Duffy, Citation2021). Some women felt that the nature of the outdoors and that environment was so integral to the experience, that it should not be disrupted by provision of extra facilities. The sample of women in this research is likely to be from those who have a strong interest in adventurous activities and/or a high level of participation so perhaps it is not surprising that several of the women stated that they had a mindset to cope and participate regardless of menses.

This research empowered women to voice their thoughts, feelings and opinions on the impact of menstruation/PMS on their participation in adventurous activities. It resulted in rich data and provides direction towards key recommendations for practice. A larger dataset, more consideration of a wider demographic or a comparison to those who have less experience of adventurous activities would be areas for future research. More depth would have been achieved through interviews and the limitation of not seeking the level of awareness of men around menstruation and its effect on participation is acknowledged.

Conclusion and recommendations

The findings from this research suggest that further action is needed in respect of raising awareness of the challenges that women face in participating in adventurous activities because of menstruation/PMS. If the sample of regular participants or those with a strong interest in adventurous activities is suggesting that for many, it is still a challenge to manage menstruation and participate to the level they would wish to, there needs to be a strategy if we are to encourage more young women and girls to participate. There has been some movement in deconstructing the stigma and taboo of menstruation through period poverty campaigns and the abolition of tax on sanitary products in the U.K. and other countries, although there is still a long way to go in this western society to achieve widespread and open discussion about it.

In respect of recommendations to support women and girls’ participation in adventurous activities, firstly there needs to be clean, accessible toilet facilities (with sanitary bins) near to the locations of activities where possible with time and encouragement within the duration of the activity to use them. Secondly, any research into the development of sanitary products that will degrade in the environment needs to be shared and promoted. Thirdly, there needs to be an awareness raising exercise amongst outdoor leaders, educators and instructors, particularly men in order that women feel comfortable in their presence and can develop strategies that will support women and girls as participants. Lastly, there needs to be a greater focus on training and employing people who identify as female in the outdoor profession and encouragement to them to act as role models and feel empowered to give advice as appropriate to their participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data not available due to ethical restrictions.

References

- ActionAid. (2021). Period poverty. https://www.actionaid.org.uk/our-work/womens-rights/period-poverty

- Bialeschki, D., & Henderson, K. (1993). Expanding outdoor opportunities for women. Parks & Recreation, 28(8), 36–40.

- Birke, L. (2003). Shaping biology: Feminism and the idea of ‘the biological’. In S. J. Williams, L. I. A. Birke, & G. Bendelow (Eds.), Debating biology: Sociological reflections on health, medicine and society (pp. 39–52). Taylor and Francis.

- Botta, R. A., & Fitzgerald, L. (2020). Gendered experiences in the backcountry. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education and Leadership, 12(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.18666/JOREL-2020-V12-I1-9924

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neurophysical and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association.

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Boulton, E., Davey, L., & McEvoy, C. (2021). The online survey as a qualitative research tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(6), 641–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1805550

- Buckley, T., & Gottlieb, A. (1988). Blood magic: The anthropology of menstruation. University of California Press.

- Burni, C. (1995). Do women attract bears? Backcountry, 23(5), 18.

- Byrd, C. P. (1988). Of bears and women: Investigating the hypothesis that menstruation attracts bears. [Unpublished dissertation]. University of Montana.

- Crawford, D. W., & Godbey, G. (1987). Reconceptualizing barriers to family leisure. Leisure Sciences, 9(2), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490408709512151

- Creswell, J. W. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design. SAGE.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods approaches. SAGE.

- Dawson, E., & Reilly, T. (2009). Menstrual cycle, exercise and health. Biological Rhythm Research, 40(1), 99–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/09291010802067213

- De Sousa, M. J., Toombs, R. J., Scheid, J. L., O’Donnell, E., West, S. L., & Williams, N. I. (2010). High prevalence of subtle and severe menstrual disturbances in exercising women: Confirmation using daily hormone measures. Reproductive Endocrinology, 25(2), 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dep411

- Doran, A. (2016). Empowerment and women in Adventure Tourism: A negotiated journey. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 20(1), 57–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2016.1176594

- Duffy, A. (2021). INclusivity in the OUTdoors: Phase 1. Raising our game report. https://www.outdoor-learning.org/Portals/0/IOL20Documents/Equality20Diversity20Inclusion/Inclusivity20in20the20Outdoors/EDI20-20Webinar20Series20Report.pdf?ver=2021-11-22-155512-293

- Dykzeul, A. J. (2016). The last taboo in sport: Menstruation in female adventure racers. [Unpublished dissertation]. Massey University.

- Ghazel, N., Souissi, A., Chtourou, H., Aloui, G., & Souissi, N. (2020). The effect of music on short-term exercise performance during the different menstrual cycle phases in female handball players. Research in Sports Medicine, 30(1), 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438627.2020.1860045

- Girlguiding UK. (2021). End period poverty and stigma. https://www.girlguiding.org.uk/girls-making-change/ways-to-take-action/period-poverty/

- Gosselin, M. (2013). Menstrual signs and symptoms, psychological/behavioural changes and abnormalities. Nova Science Publishers.

- Gottlieb, A. (2020). Menstrual taboos: Moving beyond the curse. In C. Bobel, I. T. Winkler, B. Fahs, K. A. Hasson, E. A. Kissling, & T.-A. Roberts (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies (pp. 143–161). Palgrave MacMillan.

- Houppert, K. (1999). ‘The curse’: Confronting the last unmentionable taboo: Menstruation. Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

- Jackson, E. L. (1988). Leisure constraints: A survey of past research. Leisure Sciences, 10(2), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490408809512190

- Johnston-Robledo, J., & Stubbs, M. L. (2013). Positioning periods: Menstruation in social context. Sex Roles, 68(1–2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0206-7

- Kono, S., & Ito, E. (2021). Effects of leisure constraints and negotiation on activity enjoyment: A forgotten part of the leisure constraints theory. Annals of Leisure Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/117453982021.1949737

- Little, D., & Wilson, E. (2005). Adventure and the gender gap: Acknowledging diversity of experience. Society and Leisure, 28(1), 185–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/07053436.2005.10707676

- Little, D. E. (2002). Women and adventure recreation: Reconstructing leisure constraints and adventure experiences to negotiate continued participation. Journal of Leisure Research, 34(2), 157–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2002.11949967

- Lynch, P. (1996). Menstrual waste in the backcountry. Science for conservation, 35. Department of Conservation.

- Madhusmita, M. (2015). Menstrual health in the female athlete. In M. L. Mountjoy (Ed.), Handbook of sports medicine and science: The female athlete (pp. 67–75). John Wiley & Sons.

- Meyer, K. (2020). How to shit in the woods. An environmentally sound approach to a lost art. Ten Speed Press.

- Moreno-Black, G., & Vallianatos, H. (2005). Young women’s experiences of menstruation and athletics. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 33(1/2), 50–67.

- Moustakas, C. E. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. SAGE.

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Peranovic, T., & Bentley, B. (2017). Men and menstruation: A qualitative exploration of beliefs, attitudes and experiences. Sex Roles, 77(1-2), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0701-3

- Periodequity. (2021). It’s time for menstrual equity for all. https://www.periodequity.org/

- Raymore, L. A. (2002). Facilitators to leisure. Journal of Leisure Research, 34(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2002.11949959

- Saldaňa, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE.

- Thorpe, H. (2012). Moving bodies beyond the social/biological divide: Toward theoretical and transdisciplinary adventures. Sport, Education and Society, 19(5), 666–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.691092

- Thorpe, H., Brice, J., & Rollaston, A. (2020). Decolonising sport science: High performance sport, indigenous cultures, and women’s rugby. Sociology of Sport, 37(2), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2019-0098

- Wharton, C. Y. (2020). Middle-aged women negotiating the ageing process through participating in outdoor adventurous activities. Ageing and Society, 40(4), 805–822. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18001356

- Wilson, E., & Little, D. (2005). A ‘relative escape’? The impact of constraints on women who travel solo. Tourism Review International, 9(2), 155–175. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427205774791672

- Winkler, I. T. (2020). Introduction: Menstruation as fundamental. In C. Bobel, I. T. Winkler, B. Fahs, K. A. Hasson, E. A. Kissling, & T.-A. Roberts (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies (pp. 9–12). Palgrave MacMillan.