ABSTRACT

Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals are based on a vision of how we can manage sustainable development issues in our society and environment. The purpose of this paper is to shed light on what it might mean to adopt educative aspects of sustainable development in the field of physical education and thus by that calling into question existing cultures and practices. Here we give an overview of organizational expectations on education for sustainable development. We use this approach to critically reflect on how this focus can both challenge and enable a rethinking and reorientation of physical education and physical education teacher education practices. Three steps are suggested for opening a process that can deepen our conversations and strengthen our actions in relation to education for sustainable development: curricula revisions, a reorientation of learning perspectives, and a rethinking of perspectives on health and well-being.

Introduction

In recent decades, the issue of education in relation to sustainable development has received considerable interest at a global organizational level. Education has the potential to contribute to the sustainability challenges that humanity faces (UNESCO, Citation2014). This paper will focus on what sustainable development might mean educatively in the field of physical education. Not surprisingly, sustainability and education trigger debates within the education community, some of whose members are comfortable and eager to infuse the term with meaning and address underrepresented issues; others are uncomfortable with the ‘globalizing’ nature of education for sustainable development (ESD). Yet, others recognize limitations to the terminology as it can mask, at the level of common understanding, epistemological layers (Wals & Jickling, Citation2002). As sustainability and environmental issues are about cultural identities, social and environmental equity, respect, social–nature relationships, and tensions around intrinsic and instrumental values, these issues are variable, unstable, and can easily be questioned (Wals & Jickling, Citation2002, p. 223). Nevertheless, there are reasons to highlight sustainability in order to find a common language to discuss and act in relation to different aspects of sustainability (Wals & Jickling, Citation2002, pp. 222–223).

Already in the late 1980s, the UN World Commission on Environment and Development (Citation1987), often called the Brundtland Commission, defined sustainable development as ‘to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (p. 47). This leaves it open to several interpretations because sustainability as a metaphor does not prescribe the handling of each individual case. It therefore involves several ontological and epistemological layers: what is to be sustained, how, for whom, and by whom (Barker et al., Citation2014; Lugg, Citation2007; Sund & Greve Lysgaard, Citation2013). However, exploring educative aspects in relation to education and sustainable development needs to be well anchored in educational philosophy and linked to educational theories to avoid policies appearing disconnected and miseducative and merely as normative statements (Sund & Greve Lysgaard, Citation2013). Hence, the more specific purpose of this paper is not to debate different definitions but to explore what it might mean to adopt educative aspects of sustainable development, as defined by Agenda 2030 and the SDGs, in the field of PE, thus calling into question existing cultures, content, and practices. This is made from an interpretivist and social constructionist paradigm.

Education for sustainable development

UNESCO (Citation2014) defines the concept of ESD as ‘integrating the principles and practices of sustainable development into all aspects of education and learning, to encourage changes in knowledge, values and attitudes with the vision of enabling a more sustainable and just society for all’ (p. 4). Four thrusts are advocated: ESD should be based on quality education, reorient existing education to address sustainable issues, increase public awareness of sustainability, and provide training in this in all sectors. In Agenda 2030, the UN’s (Citation2015) universal call to action, recognized by its Members states all sectors of society are encouraged to mobilize to create an inclusive and equal society and improve the lives of people worldwide and the health of our planet. Thus, the UN recognizes explicitly education as a main driver to realize Agenda 2030 and the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (see ).

This call for ESD is taken up by several other organizations. In the Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030, the World Health Organization (WHO) explicitly links physical activity (PA) to Agenda 2030 and thirteen of the SDGs. It is specified that, in addition to the health benefits of regular PA, ‘societies that are more active can generate additional returns on investment including a reduced use of fossil fuels, cleaner air and less congested, safer roads’ (WHO, Citation2018, p. 6). Through direct and indirect pathways, ‘investing in policies to promote walking, cycling, sport, active recreation and play can contribute directly to achieving many of the 2030 [SDGs]’ (WHO, Citation2018, p. 7).

Based on the goals set out in Agenda 2030, the project The Future of Education and Skills 2030 was launched in 2019 by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, Citation2019a) to help countries find answers to the question of what knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values students need to thrive and shape their world. Furthermore, the project looks at how instructional systems can effectively support/develop these skills, attitudes, values, and knowledge. The OECD has for the first time also highlighted the PE curriculum as part of its policy analysis, which resulted in the report Making Physical Education Curricula Dynamic and Inclusive for 2030 (OECD, Citation2019b) Here a team of researchers explore the state of PE policies and practices in a variety of countries. One conclusion is that to establish a qualitative-driven, dynamic, and inclusive PE curriculum, students’ well-being should be the focal point, with a broader and long-term perspective, emphasizing students’ social and emotional skills and experiences, alongside cognitive development, agency, and academic outcomes. The report highlights the fact that the implementation of the PE curriculum should ensure inclusiveness. This can be achieved by choosing an appropriate content and focus, as well as suitable forms of deliveries, opportunities, and access for the diverse range of students, irrespective of gender, disability, social class, ethnicity, and sexuality. PE might thus offer further means to shift practices that can engage students that are not engaged in PE and become a more attractive learning environment.

The report aligns closely with Agenda 2030 and the SDGs and has clear links to several of them, not least to quality education (#4). Furthermore, it is specified that ‘the effective development of competencies requires nurturing knowledge (i.e. content, concepts), skills, attitudes and values’ (OECD, Citation2019b, p. 15), thus stressing the need to switch to knowledge-rich and competency-based curricula. As the report suggests, this can be achieved by incorporating cross-curricular themes and competencies into key PE concepts.

Nikel and Lowe (Citation2010) define quality education as seven dimensions of quality held in a dynamic tension. Quality education is about effectiveness, efficiency, and equity but also about responsiveness, relevance, reflexivity, and sustainability, where the last-mentioned focuses on goal-setting, decision making, and evaluation, as well as on the ability to put longer-term goals ahead of present goals and the global alongside the local. Another dimension of quality education is the learner’s cognitive development, the promotion of values and attitudes of responsible citizenship, and supporting creative and emotional development, of relevance to the OECD report (OECD, Citation2019b). We live in a world where the accessibility of rapidly changing information and how to deal with facts and information also need to be part of quality education (Laurie et al., Citation2016).

The above-mentioned documents recognize education, sport, and PA as critical to achieving several of the SDGs. It therefore makes sense that school PE and physical education teacher education (PETE) have the potential to contribute to the visions set out, but there is little research on with what and how. A recent literature review focusing on the distinct role of PE in Agenda 2030 and the SDGs resulted in about 4400 papers published between 2015 and March 2021, only three of which met the following inclusion criteria: physical education, SDG, and Agenda 2030 (Fröberg & Lundvall, Citation2021). Hence, educative aspects of sustainable development seem to be a largely unexplored research area in the field of PE. As policy, discourses and evidence chains vary and differ at times and in the contexts of organized sport and PE, our focus in this paper will be on the latter (Green, Citation2014; Lindsey & Darby, Citation2019; Lynch & Boylan, Citation2016; Lynch & Soukup, Citation2016).

Next, our paper points to current issues and challenges facing quality education in PE and in relation to the agreed road map for sustainable development, Agenda 2030. In the final section, we suggest a strategy to open up a process of reorientation and rethinking that can deepen our conversation and strengthen actions vis-à-vis educative aspects of sustainable development in the field of PE.

Background

Current issues surrounding quality PE and PETE

PE takes various forms in countries throughout the world. In many of them, the core content of PE includes sport and movement education, health and lifestyle topics, such as associations between PA, diet, and health, as well as outdoor life and activities (Green, Citation2014; Hardman, Citation2008). In PE, students can experience positive social interactions, learn to cooperate, and demonstrate empathy and respect (Bailey et al., Citation2009; Beni et al., Citation2017; Opstoel et al., Citation2020). In addition, PE might have unique opportunities to improve children’s movement capability and physical ability during lessons (Hollis et al., Citation2016, Citation2017) as well as facilitate lifelong PA and healthy lifestyle choices (McKenzie & Lounsbery, Citation2014; Sallis et al., Citation2012).

The educational benefits that PE is claimed to have, for instance, in cognitive, social, affective, and physical domains, are contested (Bailey et al., Citation2009; Beni et al., Citation2017; Green, Citation2014). In contemporary PE, there are several issues around quality education in PE. Researchers have criticized the current multi-activity-based PE curriculum (Tinning, Citation2012), where competition is common (Aggerholm et al., Citation2018), and a narrow set of sport-related activities seem legitimated (Nabaskues-Lasheras et al., Citation2020). In this sense, PE follows conventional sport logic and is more similar to recreation than a learning environment (Larsson & Karlefors, Citation2015; Quennerstedt, Citation2019; Redelius et al., Citation2015). Researchers have also questioned the multi-activity-based curriculum due to its presumed limited relevance to students beyond PE lessons (Ennis, Citation2015; Penney & Jess, Citation2004). They have urged PE teachers to use more-knowledge-rich and competency-based innovations by designing open tasks that can produce a wider range of educational outcomes (Ennis, Citation2015). Furthermore, studies indicate that PE teachers consider the promotion PA and/or PE as sport-techniques as their primary objective and emphasize the correct technical execution of movements instead of focusing on movement education (e.g. Barker et al., Citation2017; Kirk, Citation2010; Lagestad, Citation2017; Quennerstedt, Citation2019). Other critical issues in relation to quality education are inclusiveness due to different forms of disabilities and other questions of marginalization linked to race, ethnicity, sexuality etc. Contemporary PE seems to be an exclusionary and marginalizing environment for some students. Idealized physicality and attitudinal dispositions informed by sports and performance are recognized (Barber, Citation2018; Nabaskues-Lasheras et al., Citation2020). Notwithstanding, being recognized and included in PE is not only dependent on previous experience from sports and performance but also on social justice factors, such as gender, sexuality, disability, social class, and ethnicity (Azzarito et al., Citation2017). It is argued that if inclusive PE is to become a reality and an attractive learning environment, PE teachers need to rethink their views on the curriculum, teaching, and learning in order to respond to inclusiveness and the heterogeneity of students (Azzarito et al., Citation2017; Lundvall & Gerdin, Citation2021; Penney et al., Citation2018; Walseth, Citation2016).

Green (Citation2014) also states that the desired engagement in youth sport through PE is hard to identify as there is no relationship between PE, youth sport, and lifelong participation. Instead, new and other lifestyle physical activities, unorganized or self-organized sports, are developing globally, leading to young people swapping traditional game activities for recreational lifestyle activities (Wiium & Säfvenbom, Citation2019).

Although health and lifestyle topics are usually part of PE’s core content, it seems unclear how quality education issues around health and well-being should be understood and framed within PE (Pühse et al., Citation2011; Taylor et al., Citation2019, Citation2016). This includes how to talk about health and the human connections between health and the environment. PE teachers should provide students with knowledge and skills so they can be critical of and reflective about health-related information, and arrange for them to discuss different theoretical perspectives on health rather than merely provide health-related information (McCuaig & Quennerstedt, Citation2018). A recent literature review found that health is generally didactically framed from a biomedical or an alternative (salutogenic) perspective (Mong & Standal, Citation2019). The biomedical perspective mainly concerns PA for health, and this might mean that increased PA equals improved health, which suggests that PE should provide opportunities for pupils to engage in PA. The alternative perspective, however, presents a different conception of health and well-being, one significantly broader than the biomedical perspective (Mong & Standal, Citation2019). Furthermore, the PE-field lacks in-depth knowledge of how nature and green environment exposures have positive effects on human health (Taylor et al., Citation2019; WHO, Citation2016).

The above issues around quality education are all central to educative aspects of ESD. Several of the above-mentioned issues related to quality education have also been debated for several decades, yet PE seems to have remained highly resistant to change over time (Kirk, Citation2010; Tinning, Citation2012). The challenges present in contemporary PE represent shortcomings in PETE. It is likely that several factors contribute to such resistance to change, including the fact that preservice PE teachers tend to have vast experience of sport and a taste for sport and PA (Larsson et al., Citation2018). To some extent, PE and PETE cultures, norms, and values might be taken for granted and seldom challenged by surrounding discourses (Dowling, Citation2011; McEvoy et al., Citation2017; Richards et al., Citation2014). Today it is unclear how aspects of sustainable development are dealt with both within PETE and the broader field of PE (Fröberg & Lundvall, Citation2021). Because teachers are at the heart of the micro-level of education, and if any changes are to take place we need to understand more about what teachers are doing and what is possible within the curriculum and school systems (Boeren, Citation2019). Secondly, as part of this, teaching futures PETE is an important component to take under consideration.

Contextualizing Agenda 2030 in the field of PE

Taking into consideration the desired rethinking and reorientation of PE, as expressed by UNESCO (Citation2014) and the Agenda 2030, we will now suggest three steps for opening a process that can deepen the conversation and strengthen action in relation to Agenda 2030, the SDGs, and ESD in the field of PE. Of interest is how this universal call and the desired rethinking and/or reorientation can come about and how changes in perspectives can bring in educative aspects of sustainability to be incorporated in the field of PE. The suggested steps are a response to the criticism of (the lack of) quality education in PE and the earlier mentioned absence of research and practice highlighting sustainability and ESD. These steps all encompass the means to consider exploring and concretizing what sustainability as a process and direction can mean. The first step is to critically analyze and revise curricula and steering documents for PETE programs and school PE in each country where the Agenda 2030 perspective and the SDGs are considered. The second step proposes a rethinking of the learning perspectives in the field of PE to ensure quality PE in terms of building a capacity for change and reflection, practicing values of citizenship, and the ability to put oneself as an individual in relation to, and as part of, the whole. Finally, the third step entails a reorientation of perspectives on health and well-being from a holistic perspective in order to expand teachers’ and students’ skills and knowledge of the interplay and relationship between health, well-being and the environment. Below we describe in short the proposed steps and our thoughts on how to develop each of them. We are fully aware that there is no simple solution to these issues and that each country and region must find their way forward as the global and the local must go side by side.

Revision of curricula

To start with, we need to consider that quality education should be seen in the light of how societies define the purpose of education, a disputable and, to some extent, currently neglected question (Biesta, Citation2014, Citation2015). This involves being aware of knowledge regimes and an educationalized culture, where social and environmental problems often become assigned to be solved by education (see for example Eriksen, Citation2017; Tröhler, Citation2015). Education is a space for explorative actions and a moral practice together with others (Biesta, Citation2014, Citation2015): what interests are at play, for whom, why, and what does this ask of education, of me and in connection to our environment? Furthermore, we ought to remember that all education is normative in the sense that it has a purpose (Sund & Greve Lysgaard, Citation2013) and that all practical pedagogy is a normative endeavor (Tinning, Citation2008). The question of what knowledge has been silenced or subjugated needs to be asked in order to open up new conditions of possibilities, a rethinking to look past the usual criticism of the discourses on PE (Taylor et al., Citation2019).

We therefore suggest a critical analysis and revision of curricula and steering documents to review what parts of Agenda 2030 and which SDGs are applicable to/appropriate for ESD in PETE and PE. This is to meet the desire for knowledge-rich and competency-based curricula. The reason being that sustainability issues often have a whole-of-school, and less of a subject-specific, approach. Not all SDGs will be relevant to PE teaching and learning. Taylor et al. (Citation2016) encourages each country to analyze their curriculum and talk about health and localized caring and actions. Here we suggest processes where collaborative learning projects with teachers can start in local schools or regions as part of a bottom-up process: which SDGs will be relevant to our schools, to PE, to whom, and why, where, and when? There are theoretical frameworks to support such analysis and revision, but critical practice-based analysis is required to make teaching, learning, and assessment relevant (see, for example, Osman et al., Citation2017). Interactive tools can be used to get aquatinted with how to further explore Agenda 2030 and the SDGs (see, for example, Eriksson, Ahlbäck, Silow, & Svane, Citation2019). Curricula and dimensions of quality education are linked to a learner’s cognitive, affective, emotional and social development and the promotion of values and attitudes of responsible citizenship. Such citizenship can question and explore daily movement activities and PA and how these activities are affected by power and politics at local, regional, and national levels. To support sustainable choices, movement, sport and PA require physical and green spaces that is accessible, safe, and enjoyable (Kelso et al., Citation2021).

Reorientation of a learning perspective

Even if a revision of curricula and dimensions of quality education is easy to put forward as an overarching way of incorporating educative aspects of sustainable development in the field of PE, several researchers state that, besides the call for a multidisciplinary and holistic approach, an elaborated understanding of learning needs to be introduced (Boström et al., Citation2018; Wals & Jickling, Citation2002). An often-recommended onto-epistemological perspective is a transformative learning perspective (Boström et al., Citation2018; Laurie et al., Citation2016). Mezirow (Citation2018) defined this perspective as ‘a process by which we transform problematic frames of reference (e.g. mind-sets, habits of mind, meaning perspectives) – sets of assumptions and expectations – to make them more inclusive, discriminating, open, reflective and emotionally able to change’ (p. 116). This critical learning perspective enables actors to recognize and reassess structures of assumptions and experiences that frame their thinking, feeling, and acting. It involves cognitive, social, moral, and affective components as well as values of structural and cultural conflicts because structures of meaning construct references.

A transformative learning process and pedagogy seek to establish or enable embodied authentic learning situations where the teacher is more of a driver of change, a facilitator, and focus on habits of mind and points of view on what prevents change or conflict, involving macro-, meso-, and microspheres (Boström et al., Citation2018; Hulteen et al., Citation2014; Mezirow, Citation2018). For PE, this means disrupting a historical dualism of binary human nature as well as a critique of existing norms and values. It aims to advocate deliberative learning processes and highlight institutions, social and political contexts, and power relations, not separate knowledge worlds. Few PE scholars, outside of outdoor education and experiential learning, have adopted a transformative perspective (Hill & Brown, Citation2014; Meerts-Brandsma et al., Citation2020; Ross et al., Citation2014). Adopting transformative processes is to open up for sociocultural, poststructural and posthumanism theories, and can be contrasted against informative learning. The very form of learning is changed by our form of understanding meaning making. Informative learning is about changes in what and how we know and the communicative about the why. As a transformative perspective involves social, moral, and affective components, this perspective touches upon ontology and aspects of being. Discursive resources and personal experiences are seen as valuable, not the least when placing the global besides the local.

Accordingly, this learning perspective provides possibilities that ontological and epistemological issues will encounter. The learning approach may involve a change in behavior but is more of a shift in focus from the self to others, thus stimulating an understanding of ourselves, a turn to new epistemic issues, and how we as humans are situated in society and the environment (Meerts-Brandsma et al., Citation2020). Critical posthumanist researchers such as Olive and Enright (Citation2021) suggest an oceanic approach in terms of fluidity and interconnection of layers so as to give space to environmental and social justice issues. Taylor et al. (Citation2019) point to the need to adopt a whole-of-curriculum approach so educative aspects of sustainability can be positioned centrally and explicitly in teaching and learning. An educative approach to sustainability suggests not only a change of perspective but also seeing curricula, learning outcomes, and content through transformative and educative eyes. However, a holistic approach linked to a whole-of-curriculum approach helps to create an educative environment where relationships between bodies, movement, nature, and the social-cultural environment are central to pedagogical strategies that support an environmentally engaged PE (Olive & Enright, Citation2021; Truong, Citation2017). Nevertheless, we have to know who and what are to be transformed, and the purpose and meaning of that to call into question the existing. The different stages of transformative learning includes the selection of a topic or a theme to engage in, a self- examination of one’s experience, a critical assessment of epistemic and/or sociocultural, psychic assumptions, a process of transformation with shared discussions, and the exploring of other potential meanings/roles, building competence to take on new or other actions or needs (Mezirow, Citation2018). This indicates that just adding new key competencies and/or content is not the way forward for a quality education in PE. We advocate to dispense with a message system of performative schooling cultures privileging reductive practices (see Evans & Davies, Citation2014; Kirk, Citation2010; Quennerstedt, Citation2019). Adopting a transformative perspective on learning addresses a deeper engagement with structural and cultural barriers preventing change, where the environment stops being just a backdrop (Olive & Enright, Citation2021; Schantz & Lundvall, Citation2014). Sustainable development in a transformative learning process is an ongoing critical, processual dialogue. It is not education about sustainability but for sustainability as a process and direction (Boström et al., Citation2018).

Adopting a transformative learning perspective followed by a transformative pedagogy can help illuminate ontological limitations to various subjugated knowledge in students’ own lives and their ways of creating change (see, for example, Olive & Enright, Citation2021; Taylor et al., Citation2019). Teacher-centered teaching can become more student-centered with authentic assignments in the form of lab work (Kioupi & Voulvoulis, Citation2019). This way of working lets students problematize their ‘own’ current and future situations, whereby their interest can increase. With such an approach, students can be better equipped to address and deal with the challenges and aspects of sustainability they face now and in the future (Laurie et al., Citation2016). It is not about maneuvering certain views or standpoints but empowering consciousness and critical reflections as part of quality education (see SDG #4). It is also about engaging and reflecting and being aware of indoctrinating or eco-authoritarian value systems and/or teaching styles (Sund & Greve Lysgaard, Citation2013; Öhman & Sund, Citation2021).

Rethinking perspectives on health and well-being

As described in the overview of research on PE, the lack of teaching strategies on how to adopt a holistic approach to health pose a challenge. Broader dimensions of what public health is and can be in relation to PE and PA need incorporating in order to align with the SDGs quality education (#4), good health and well-being (#3) and equality (#5). This is crucial to rethinking the field of PE (see also Webster et al., Citation2015). Factors external to the individual, different approaches to PA recommendations, conceptually narrow views on health and well-being, and how to negotiate these spaces become relevant to highlight and important for educative aspects to discuss (Taylor et al., Citation2016). Including a holistic perspective on health and well-being also prompts analyses of the consequences of PA behaviors, leaving a static view on movement training and PA as, first and foremost, energy expenditure. Health and well-being are much more complex than just counting the number of steps or the bouts of acceleration of movement. Moreover, PETE and PE lack a knowledge tradition that links the environment and health (Schantz & Lundvall, Citation2014).

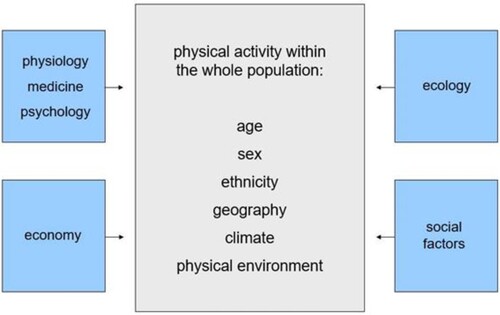

There are already numerous good examples of how to work with health and well-being. However, we have still maintained an individualistic view of health – and some would say – a neoliberal relationship to health, leading to a stressed and pressured relationship to the body and health and the responsibility of the self (the individual) (McCuaig & Quennerstedt, Citation2018). By rethinking our course of action for health education as part of sustainability and lifelong learning, other issues can come to the fore. Accordingly, it might be critical to bridge the gap between the biomedical and alternative perspectives to come closer to the educative aspects of sustainable development. In this regard, pedagogical strategies and health practices in and about health could develop when framed as a holistic, multidimensional concept (McCuaig & Quennerstedt, Citation2018; Quennerstedt, Citation2019; Schantz & Lundvall, Citation2014). A framing of a broader perspective on how to understand public-health dimensions from a more holistic standpoint is illustrated in (see also Silva et al., Citation2017).

Figure 2. The modified Schantz model (2006) with central stand points of departure for public-health dimensions for the promoting of PA (as cited in Schantz & Lundvall, Citation2014).

We suggest a rethinking where societal health (public and environmental health), individual health, and well-being are incorporated and given equal importance. We have had a decades-long public-health debate on the risks of physical inactivity and obesity. However, less attention has been paid to what creates health and how the relationship between health and the environment interplays and can interplay. Since the beginning of the millennium, several studies use socioecological models to understand influences on PA levels (Sallis, Owen, & Fischer, Citation2008). This can be related to participation in physical activities during PE, in schoolyards, parks, and active commuting (biking or walking). Research has also started to draw attention to the influence of aesthetical aspects when trying to understand what drives people’s movement and PA choices. Active commuting is one such phenomenon studied. The findings show that green environments and aesthetic experiences influence people’s commuting decisions and choices (Wahlgren & Schantz, Citation2012, Citation2014). Furthermore, a study exploring students’ relationship to a favorite place when being outdoors indicates that dimensions of environing and well-being and the coordinating of aesthetical experiences help to understand how students create meaning and sense making of being outdoors in nearby areas (Lundvall & Maivorsdotter, Citation2021). Being in a favorite place created feelings of well-being, such as calm, joy, and safety, which points to the importance of paying attention to bodily experiences, and the interplay to place when learning about being outdoors. To be sustainable in relation to health and well-being means critically embracing a holistic and heuristic approach to the experiencing body, movement education and PA that is relevant to PE- and PETE-students, goes beyond the PE-classroom, and adopts a lifelong perspective. This includes values, meanings, and symbols that can become part of everyday life experiences since health and well-being are created in an interaction and transaction within and between individuals and the local and global environment (Lake, Citation2001; Sawyer et al., Citation2012; Viner et al., Citation2012). This also relates to social justice issues, emphasizing the illumination of ontological limitations to various forms of subjugated knowledge in students’ lives and their ways of creating change (see, for example, Olive & Enright, Citation2021; Taylor et al., Citation2018; Walton-Fisette & Sutherland, Citation2018; Wrench & Garrett, Citation2015). If we highlight health and the environment, educative aspects in relation to norms and values can come to the fore vis-à-vis not only the SDGs health and well-being (#3) and quality education (#4) but also gender equality (#5), reduced inequality (#10), sustainable cities (#11), as well as responsible consumption and production (#12).

Conclusion

Our position is that adopting educative aspects of sustainable development in the field of PE both challenges and acknowledges a critical learning perspective where illuminating transformative processes can lead to a rethinking and reorientation in the field. What ESD can offer is encouraging changes in knowledge, values, and attitudes in order to explore what sustainability can mean in a certain situation and environment where movement and health education are produced, embodied, and performed (Larsson & Quennerstedt, Citation2012). The suggested steps are a response to the widespread criticism of the multi-activity-based curriculum, with less focus on learning, and the non-inclusive classroom environment as well as to the universal call to action issued by Agenda 2030. Taken together, this can both challenge and enable a rethinking and reorientation in PE and offer a new point of departure with fresh possibilities for innovative teaching and learning processes where sustainability, as a process and direction, is incorporated. In addition, the field of PE can start to address issues of ESD as part of our everyday life experiences and choices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aggerholm, K., Standal, Ø. F., & Hordvik, M. M. (2018). Competition in physical education: Avoid, ask, adapt or accept? Quest, 70(3), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2017.1415151

- Azzarito, L., Simon, M., & Marttinen, R. (2017). ‘Up against whiteness’: Rethinking race and the body in a global era. Sport, Education and Society, 22(5), 635–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2015.1136612

- Bailey, R., Armour, K., Kirk, D., Jess, M., Pickup, I., Sandford, R., & BERA Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy Special Interest Group. (2009). The educational benefits claimed for physical education and school sport: An academic review, Research Papers in Education, 24(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520701809817

- Barber, W. (2018). Inclusive and accessible physical education: Rethinking ability and disability in pre-service teacher education. Sport, Education and Society, 23(6), 520–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1269004

- Barker, D., Barker-Ruchti, N., Wals, A., & Tinning, R. (2014). High performance sport and sustainability: A contradiction of terms? Reflective Practice, 15(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2013.868799

- Barker, D., Bergentoft, H., & Nyberg, G. (2017). What would physical educators know about movement education? A review of literature, 2006–2016. Quest, 69(4), 419–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1268180

- Beni, S., Fletcher, T., & Ní Chróinín, D. (2017). Meaningful experiences in physical education and youth sport: A review of the literature. Quest, 69(3), 291–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1224192

- Biesta, G. (2015). What is education for? On good education, teacher, judgement, and educational professionalism. European Journal of Education, 50(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12109

- Biesta, G. J. (2014). The beautiful risk of education. Paradigm Publishers.

- Boeren, E. (2019). Understanding Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 on “quality education” from micro, meso and macro perspectives. International Review of Education, 65(2), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-019-09772-7

- Boström, M., Andersson, E., Berg, M., Gustafsson, K., Gustavsson, E., Hysing, E., Lidskog, R., Löfmarck, E., Ojala, M., Olsson, J., Singleton, B., Svenberg, S., Uggla, Y., & Öhman, J. (2018). Conditions for transformative learning for sustainable development: A theoretical review and approach. Sustainability, 10(12), 4479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124479

- Dowling, F. (2011). ‘Are PE teacher identities fit for postmodern schools or are they clinging to modernist notions of professionalism?’ A case study of Norwegian PE teacher students’ emerging professional identities. Sport, Education and Society, 16(2), 201–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2011.540425

- Ennis, C. D. (2015). Knowledge, transfer, and innovation in physical literacy curricula. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 4(2), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2015.03.001

- Eriksen, T. H. (2017). Introduction: Knowledge regimes in an overheated world. In B. Campbell, E. Schober, T. Hylland Eriksen, C. Garsten, & D. McNeill (Eds.), Knowledge and power in an overheated world (pp. 7–19). Department of Social Anthropology.

- Eriksson, M., Ahlbäck, A., Silow, N., & Svane, M. (2019). SDG Impact Assessment Tool (SDG-IAT). Guide 1.0. https://www.unsdsn-ne.org/our-actions/initiatives/sdg-impact-tool/

- Evans, J., & Davies, B. (2014). Physical education PLC: Neoliberalism, curriculum and governance. New directions for PESP research. Sport, Education and Society, 19(7), 869–884. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2013.850072

- Fröberg, A., & Lundvall, S. (2021). The distinct role of physical education in the context of Agenda 2030 and Sustainable Development Goals: An explorative review and suggestions for future work. Sustainability, 13(21), 11900. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111900

- Green, K. (2014). Mission impossible? Reflecting upon the relationship between physical education, youth sport and lifelong participation. Sport, Education and Society, 19(4), 357–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.683781

- Hardman, K. (2008). Physical education in schools: A global perspective. Kinesiology, 40(1), 5–28.

- Hill, A., & Brown, M. (2014). Intersections between place, sustainability and transformative outdoor experiences. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 14(3), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2014.918843

- Hollis, J. L., Sutherland, R., Williams, A. J., Campbell, E., Nathan, N., Wolfenden, L., Morgan, P. J., Lubans, D. R., Gillham, K., Wiggers, J., & Wiggers, J. (2017). A systematic review and meta-analysis of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity levels in secondary school physical education lessons. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0504-0

- Hollis, J. L., Williams, A. J., Sutherland, R., Campbell, E., Nathan, N., Wolfenden, L., Morgan, P. J., Lubans, D. R., & Wiggers, J. (2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity levels in elementary school physical education lessons. Preventive Medicine, 86, 34–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.11.018

- Hulteen, R. M., Smith, J. J., Morgan, P. J., Barnett, L. M., Hallal, P. C., Colyvas, K., & Illeris, K. (2014). Transformative learning and identity. Journal of Transformative Education, 12(2), 148–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344614548423

- Kelso, A., Reimers, A. K., Abu-Omar, K., Wunsch, K., Niessner, C., Wäsche, H., & Demetriou, Y. (2021). Locations of physical activity: Where are children, adolescents, and adults physically active? A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031240

- Kioupi, V., & Voulvoulis, N. (2019). Education for sustainable development: A systemic framework for connecting the SDGs to educational outcomes. Sustainability, 11(21), 6104. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216104

- Kirk, D. (2010). Physical education futures. Routledge.

- Lagestad, P. (2017). Longitudinal changes and predictors of adolescents’ enjoyment in physical education. International Journal of Educational Administration and Policy Studies, 9(9), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJEAPS2017.0523

- Lake, J. (2001). Young peopleís conceptions of sport, physical education and exercise: Implicationsfor physical education and the promotion of health-related exercise. European Physical Education Review, 7(1), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X010071003

- Larsson, H., & Karlefors, I. (2015). Physical education cultures in Sweden: Fitness, sports, dancing … learning? Sport, Education and Society, 20(5), 573–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.979143

- Larsson, H., & Quennerstedt, M. (2012). Understanding movement: A sociocultural approach to exploring moving humans. Quest, 64(4), 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2012.706884

- Larsson, L., Linnér, S., & Schenker, K. (2018). The doxa of physical education teacher education – Set in stone? European Physical Education Review, 24(1), 114–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X16668545

- Laurie, R., Nonoyama-Tarumi, Y., McKeown, R., & Hopkins, C. (2016). Contributions of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) to quality education: A synthesis of research. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 10(2), 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408216661442

- Lindsey, I., & Darby, P. (2019). Sport and the Sustainable Development Goals: Where is the policy coherence? International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(7), 793–812. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690217752651

- Lugg, A. (2007). Developing sustainability-literate citizens through outdoor learning: Possibilities for outdoor education in higher education. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 7(2), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729670701609456

- Lundvall, S., & Gerdin, G. (2021). Physical literacy in Swedish physical education and health (PEH): What is (im)possible in becoming and being physically literate (educated)? Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 12(2), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/25742981.2020.1869570

- Lundvall, S. & Maivorsdotter, N. (2021). Environing as embodied experience. A study of outdoor learning as part of physical education. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living. Published 12 Nov 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2021.768295

- Lynch, T., & Boylan, M. (2016). United Nations sustainable development goals: Promoting health and well-being through physical education partnerships. Cogent Education, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1188469

- Lynch, T., & Soukup, G. J. (2016). “Physical education”, “health and physical education”, “physical literacy” and “health literacy”: Global nomenclature confusion. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1217820. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1217820

- McCuaig, L., & Quennerstedt, M. (2018). Health by stealth – Exploring the sociocultural dimensions of salutogenesis for sport, health and physical education research. Sport, Education and Society, 23(2), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1151779

- McEvoy, E., Heikinaro-Johansson, P., & MacPhail, A. (2017). Physical education teacher educators’ views regarding the purpose(s) of school physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 22(7), 812–824. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2015.1075971

- McKenzie, T. L., & Lounsbery, M. A. F. (2014). The pill not taken: Revisiting physical education teacher effectiveness in a public health context. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 85(3), 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2014.931203

- Meerts-Brandsma, L., Sibthorp, J., & Rochelle, S. (2020). Using transformative learning theory to understand outdoor adventure education. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 20(4), 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2019.1686040

- Mezirow, J. (2018). An overview of transformative learning. In K. Illeris (Ed.), Contemporary theories of learning: Learning theorists in their own words (pp. 90–105). Routledge.

- Mong, H. H., & Standal, Ø. F. (2019). Didactics of health in physical education – A review of literature. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(5), 506–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2019.1631270

- Nabaskues-Lasheras, I., Usabiaga, O., Lozano-Sufrategui, L., Drew, K. J., & Standal, Ø. F. (2020). Sociocultural processes of ability in physical education and physical education teacher education: A systematic review. European Physical Education Review, 26(4), 865–884. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X19891752

- Nikel, J., & Lowe, J. (2010). Talking of fabric: A multi-dimensional model of quality in education. Compare, 40(5), 589–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920902909477

- OECD. (2019a). Future of Education and Skills 2030: OECD Learning Compass 2030. A series of concepts and notes. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/contact/OECD_Learning_Compass_2030_Concept_Note_Series.pdf

- OECD. (2019b). OECD future of education 2030: Making physical education dynamic and inclusive for 2030 international curriculum analysis. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/contact/oecd_future_of_education_2030_making_physical_dynamic_and_inclusive_for_2030.pdf

- Öhman, J., & Sund, L. A. (2021). A didactic model of sustainability commitment. Sustainability, 13(6), 3083. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063083

- Olive, R., & Enright, E. (2021). Sustainability in the Australian health and physical education curriculum: An ecofeminist analysis. Sport, Education and Society, 26(4), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1888709

- Opstoel, K., Chapelle, L., Prins, F. J., De Meester, A., Haerens, L., van Tartwijk, J., & De Martelaer, K. (2020). Personal and social development in physical education and sports: A review study. European Physical Education Review, 26(4), 797–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336x19882054

- Osman, A., Ladhani, S., Findlater, E., & McKay, V. (2017). UK. Curriculum framework for the sustainable development goals. The Commonwealth Secretariat.

- Penney, D., Jeanes, R., O'Connor, J., & Alfrey, L. (2018). Re-theorising inclusion and reframing inclusive practice in physical education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(10), 1062–1077. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1414888

- Penney, D., & Jess, M. (2004). Physical education and physically active lives: A lifelong approach to curriculum development. Sport, Education and Society, 9(2), 269–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357332042000233985

- Pühse, U., Barker, D., Brettschneider, W. D., Feldmeth, A. K., Gerlach, E., McCuaig, L., McKenzie, T. L., & Gerber, M. (2011). International approaches to health-oriented physical education - Local health debates and differing conceptions of health. International Journal of Physical Education, 48(3), 2–15.

- Quennerstedt, M. (2019). Physical education and the art of teaching: Transformative learning and teaching in physical education and sports pedagogy. Sport, Education and Society, 24(6), 611–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1574731

- Redelius, K., Quennerstedt, M., & Öhman, M. (2015). Communicating aims and learning goals in physical education: Part of a subject for learning? Sport, Education and Society, 20(5), 641–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.987745

- Richards, K. A. R., Templin, T. J., & Graber, K. (2014). The socialization of teachers in physical education: Review and recommendations for future works. Kinesiology Review, 3(2), 113–134. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2013-0006

- Ross, H., Christie, B., Nicol, R., & Higgins, P. (2014). Space, place and sustainability and the role of outdoor education. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 14(3), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2014.960684

- Sallis, J. F., McKenzie, T. L., Beets, M. W., Beighle, A., Erwin, H., & Lee, S. (2012). Physical education's role in public health: Steps forward and backward over 20 years and HOPE for the future. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport, 83(2), 125–135.

- Sallis, J., Owen, N. & Fischer, E. (2008). Ecological models of health behaviors. In K. Glanz, B., Reimer & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health Behavior and Health Education. Theory, research and practice (pp. 465–487). Wiley.

- Sawyer, S. M., Afifi, R. A., Bearinger, L. H., Blakemore, S. J., Dick, B., Ezeh, A. C., & Patton, G. C. (2012). Adolescence: A foundation for future health. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1630–1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5

- Schantz, P., & Lundvall, S. (2014). Changing perspectives on physical education in Sweden – Implementing dimensions of public health and sustainable development. In M. Chin & C. Edginton (Eds.), Physical education and health: Perspectives and best practice (pp. 463–476). Sagamore Publishing.

- Silva, K. S., Garcia, L. M., Rabacow, F. M., de Rezende, L. F., & de Sa, T. H. (2017). Physical activity as part of daily living: Moving beyond quantitative recommendations. Preventive Medicine, 96, 160–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.11.004

- Sund, P., & Greve Lysgaard, J. (2013). Reclaim “education” in environmental and sustainability education research. Sustainability, 5(4), 1598–1616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5041598

- Taylor, N., Wright, J., & O’Flynn, G. (2016). HPE teachers’ negotiation of environmental health spaces: Discursive positions, embodiment and materialism. The Australian Educational Researcher, 43(3), 361–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-016-0205-8

- Taylor, N., Wright, J., & O’Flynn, G. (2019). Embodied encounters with more-than-human nature in health and physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 24(9), 914–924. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2018.1519785

- Tinning, R. (2008). Pedagogy, sport pedagogy, and the field of kinesiology. Quest, 60(3), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2008.10483589

- Tinning, R. (2012). The idea of physical education: A memetic perspective. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 17(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2011.582488

- Tröhler, D. (2015). The medicalization of current educational research and its effects on education policy and school reforms. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 36(5), 749–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2014.942957

- Truong, S. (2017). Expanding curriculum pathways between education for sustainability (efs) and health and physical education (HPE). In K. Malone, S. Truong, & T. Gray (Eds.), Reimagining sustainability in precarious times (pp. 239–251). Springer Singapore.

- United Nations (UN). (2015, October 21). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/ RES/70/1. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2014). Shaping the future we want: UN decade of education for sustainable development 2005-2014 (Final Report).

- UN World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our common future. Oxford University press.

- Viner, R. M., Ozer, E. M., Denny, S., Marmot, M., Resnick, M., Fatusi, A., & Currie, C. (2012). Adolescence and the social determinants of health. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1641–1652. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4

- Wahlgren, L., & Schantz, P. (2012). Exploring bikeability in a metropolitan setting: Stimulating and hindering factors in commuting route environments. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 168. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-168

- Wahlgren, L., & Schantz, P. (2014). Exploring bikeability in a suburban metropolitan area using the Active Commuting Route Environment Scale (ACRES). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(8), 8276–8300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110808276

- Wals, A. E. J., & Jickling, B. (2002). Sustainability in higher education: From doublethink and newspeak to critical thinking and meaningful learning. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 3(3), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676370210434688

- Walseth, K. (2016). Sport within Muslim organizations in Norway: Ethnic segregated activities as arena for integration. Leisure Studies, 35(1), 78–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2015.1055293

- Walton-Fisette, J. L., & Sutherland, S. (2018). Moving forward with social justice education in physical education teacher education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(5), 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2018.1476476

- Webster, C. A., Webster, L., Russ, L., Molina, S., Lee, H., & Cribbs, J. (2015). A systematic review of public health-aligned recommendations for preparing physical education teacher candidates. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 86(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2014.980939

- Wiium, W., & Säfvenbom, R. (2019). Participation in organized sports and self-organized physical activity: Associations with developmental factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(4), 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040585

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2016). Urban green spaces and health. WHO Regional Office Europe.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2018). Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: More active people for a healthier world. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.M.

- Wrench, A., & Garrett, R. (2015). Emotional connections and caring: Ethical teachers of physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 20(2), 212–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.747434