ABSTRACT

Background

Childhood obesity affects around 7–8% of children in Ireland and is associated with increased risks of health complications. Data on healthcare resource use and the related costs for children with obesity are important for research, future service-planning, efforts to reduce the burden on families, and care pathways. However, there is little or no data available to describe these in Ireland.

Methods

We undertook a retrospective chart review for 322 children attending a national paediatric weight management service to assess their hospital service utilisation, and the associated costs, over a four-year period. We used a micro-costing approach and estimated unit costs for different types of hospital services. Multivariable negative binomial regression analyses and Cragg hurdle models were used to assess characteristics associated with type, frequency and costs of hospital care.

Results

Eighty-two percent of children had severe obesity, and thirty-eight percent had a co-morbid condition. Over the four-year period, children had a mean of 27 (median 24, IQR 16–33) episodes of care at a mean cost of €2590 per child (median €1659, IQR 1026–3103). The presence of a co-morbid condition was associated with more frequent visits. Neither severity of obesity nor socioeconomic status were associated with overall service utilisation. The Cragg hurdle model did not identify statistically significant differences in hospital costs according to participant characteristics.

Conclusion

Children with obesity frequently visit a variety of paediatric services and children with co-morbid conditions have greater levels of hospital utilisation. Further research is needed with larger sample sizes to explore variation in healthcare utilisation in this population, and the relationship between common co-morbidities and weight status. This would facilitate assessment of the implications for care pathways and examination of associations between patient outcomes and related healthcare costs and cost-effectiveness.

Introduction

The estimated prevalence of childhood obesity is between 7–8% in the Republic of Ireland (ROI) (Economic and Social Research Institute, Citation2019; Mitchell et al., Citation2020). The increasing prevalence over the past four decades (Abarca-Gómez et al., Citation2017) has resulted in a concurrent increase in associated health complications (Reilly & Kelly, Citation2011), thus affecting health service utilisation. There is consistent evidence from high-income countries demonstrating higher healthcare utilisation among children with obesity compared with those considered to have a “normal” or “healthy” weight (Hasan et al., Citation2020).

Obesity is defined in simple terms as “abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health” (World Health Organization, Citation2021). Scientific consensus allows for recognition of obesity as a chronic, relapsing and progressive disease, influenced by complex genetic, biological, environmental and socioeconomic factors (Farpour-Lambert et al., Citation2015). Excess adiposity in childhood is associated with conditions affecting almost every system in the body, including physical function, pain, and musculoskeletal issues (de Lima et al., Citation2020), liver disease (Weiss & Kaufman, Citation2008) and associated complications (Zhao et al., Citation2019), anxiety/depression (Quek et al., Citation2017) and respiratory conditions (Dooley & Pillai, Citation2020), in addition to well-documented endocrine and cardiovascular diseases such as dyslipidaemia, reduced insulin sensitivity and early type II diabetes mellitus. Despite the recent emergence of nuanced staging systems which go beyond size and capture metabolic, mechanical, mental health and social milieu (Hadjiyannakis et al., Citation2016), obesity is defined in this study using age- and sex-adjusted body mass index (BMI) centiles (Cole, Citation1997). A child/adolescent whose growth lies ≥98th centile is considered to have clinical obesity, while ≥99.6th centile is considered severe obesity.

Previous studies in the ROI have sought to estimate health service use among children with overweight and obesity, but limitations included a lack of detailed, patient-level clinical data. One study using nationally representative longitudinal data (Doherty et al., Citation2017) demonstrated that BMI in adolescents was positively associated with general practice (GP) visits and hospital stays. However, this was assessed using parent-reported recall of engagement with a GP service over the previous year or any hospital stay within the child’s lifetime, and did not report frequency of visits. Another study using international data (Perry et al., Citation2017) sought to estimate the lifetime cost of childhood obesity with a model-based approach, and the authors recommended more detailed studies to provide greater accuracy of local data. A recent systematic review highlighted that, despite the consistent evidence for increased healthcare utilisation among children with obesity, there is an evidence gap for the impact of obesity-related complications on healthcare use (Hasan et al., Citation2020).

There are currently no available cost data for specialist paediatric healthcare resources in the ROI to facilitate estimation of expenditure associated with secondary or tertiary paediatric care. There is no universally available unit cost schedule for health and social care activities in the ROI (Jabakhanji et al., Citation2021) equivalent to those available from the Personal Social Services Research Unit in the UK, for example. As a result, costs are often estimated using crude, high-level data from hospital sites, or estimated based on adult care, which does not account for the complex considerations associated with paediatrics. Estimating such costs in the absence of any national reference data is challenging (Asaria et al., Citation2016), and without detailed clinical information from which to assess unit costs (Frick, Citation2009), researchers are unable to undertake accurate economic analyses of paediatric conditions or interventions.

Within the public healthcare system in the ROI, specialist paediatric hospitals are all located in the greater Dublin area. These receive tertiary referrals from regional and general hospitals across the country, while also functioning as secondary care facilities for the local population of Dublin (Staines et al., Citation2016). They, therefore, account for a high percentage of service provision in this population.

There is one specialist clinical multidisciplinary obesity service available to children and adolescents in the ROI public healthcare system, located within one of the specialist paediatric hospitals (Children's Health Ireland at Temple Street, Citation2020). This service is available to children and young people who are referred for assessment or treatment of clinical obesity. Children are eligible for the service if they are aged under 16 years, have a BMI ≥98th centile (Cole, Citation1997) at the time of referral and have been referred by a medical or surgical consultant based in a specialist paediatric hospital (Children’s Health Ireland).

This study aimed to: (i) describe the frequency and types of hospital service utilisation among a consecutive sample of children referred to the obesity service; (ii) identify whether participant characteristics (severity of obesity on referral, socioeconomic status (SES), age, or known co-morbidities) were associated with differences in hospital service utilisation, and (iii) estimate unit costs of hospital visits and thus estimate the total cost of hospital service utilisation in this population over a four-year period.

Materials and methods

Design

We undertook a retrospective chart review of children and adolescents referred for clinical obesity management, to assess their hospital service utilisation over four years. This included inpatient stays, emergency department (ED) visits, and also outpatient visits to specialty consultants or health and social care professionals (HSCPs). We used a micro-costing approach (Frick, Citation2009) from a healthcare system perspective to assess the costs. This study was approved by the department of research at Children’s Health Ireland at Temple Street (19.011).

Data collection

Inclusion criteria

We included hospital utilisation data for children referred to the obesity service, from a consecutive sample recorded in the digital hospital record management system between 2008 and 2016. We excluded children who had been injured in road traffic accidents, as they accounted for a small number of children (n = 6) with high resource use and costs, unrelated to their obesity, which may represent cost outliers and potentially bias the cost assessment.

Patient data

We used electronic hospital records to assess the total number of inpatient admissions and bed days, ED and outpatient visits to hospital services for each child within the two years prior to commencing obesity management and the two years immediately following that. This time period was chosen in order to capture the type of care received by children prior to their referral for obesity management or prior to developing obesity, whilst also capturing their care throughout their obesity management and beyond. We also recorded patient demographics and characteristics including their BMI centile on referral to the service. We assessed deprivation using a national deprivation index (Pobal, Citation2019) based on geographical and socioeconomic data.

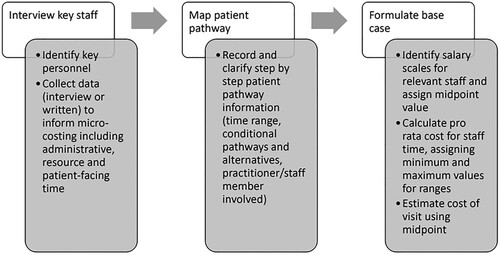

Cost assessments

In order to assess the cost of medical, surgical and HSCP outpatient visits in addition to ED visits, we used a micro-costing approach (Kaplan & Anderson, Citation2003; Keel et al., Citation2017; Yangyang et al., Citation2016) to specify a base case (). This involved staff interviews and observations to assess the staff-related workflow costs associated with each instance of clinical care. This is a detailed, bottom-up approach that assesses resource use, in this case primarily staff time, by mapping the process of clinical care to get a realistic picture of the costs involved. We interviewed various administrative staff, medical consultants, nurses, and HSCPs (dietitians, physiotherapists and psychologists) to assess the workflow for outpatient appointment time within their departments. We interviewed an emergency medicine consultant to map the typical workflow processes for three common emergency presentations and those most common among children with obesity in our cohort; a suspected fracture, abdominal pain, and respiratory distress. The researcher (LT) took field notes and used these to compile a systematic base case for time associated with activities. Costs for inpatient stays were obtained from publicly available information on payment levies for private patients (Citizen's Information, Citation2020). We did not assess investigations such as laboratory tests or complex diagnostic procedures.

The unit costs according to staff time were calculated using a formula from local guidance (Health Information Quality Authority, Citation2019) that incorporates gross salaries including pay-related social insurance (PRSI) and pension contributions, overheads and nominal working time with patient-related activities. We calculated hourly rates according to these, using midpoints from the Health Service Executive (HSE, the public health system in the ROI) salary scales published in September 2019 (Health Service Executive, Citation2019b). Government documents were used to calculate PRSI (Department of Employment Affairs and Social Protection, Citation2020). The most recently available HSE circular relating to staff holidays was used to adjust for annual leave (Health Service Executive, Citation2019a). We carried out a sensitivity analysis to assess the effect of extended time parameters and additional examinations for appointments and ED visits on overall costs and factors associated with increased costs.

Data analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe the sample and their patterns of hospital service use. We used multivariable negative binomial regression models (expressed using incidence rate ratio, IRR) to assess the effect of age, severity of obesity, SES, presence of a co-morbid condition, or intellectual disability/learning disorder on total or specific types of hospital utilisation and costs over the four years by adjusting for these variables. We also specified a seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) model to assess variations when accounting for inter-dependence of variables. A Cragg hurdle model was specified to assess whether the presence of excess zeros affected the total costs or costs per type of visit. Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used to assess differences between costs by year or in the periods pre- and post-obesity referral by children with and without known co-morbid conditions. We undertook sensitivity analyses to assess how variations in cost assumptions affected the estimated mean costs. All data analyses were carried out using Stata 15 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Missing data

Due to a changeover in the digital hospital record management system, some outpatient data were missing from 2006–2008, resulting in a slightly shorter observation time (mean 2.1 months omitted) for children whose referral was before 2010 (n = 93, 29%). Where ≥ six months of outpatient visit data were unavailable for a given year, the number of outpatient visits for that year was considered missing. For frequently used outpatient services including dietetics and physiotherapy, missing data were replaced with predictions from negative binomial regression models with personal characteristics as independent variables (Hernández-Herrera et al., Citation2020).

Results

Patient characteristics

Resource use data were compiled for a consecutive sample of children (n = 322) who had been referred to the obesity service. Demographic information and characteristics collected on referral are shown in . The mean age was 11.6 years (SD 3.3, range 1.3–17.5). The mean child body mass index (BMI) centile was 99.7 (SD 0.6, range 92.6–100), and mean BMI standardised deviation score was 3.2 (SD 0.6, range 1.5–6.3). Medical histories showed respiratory conditions to be the most common type of co-morbid condition (), most commonly asthma.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the sample (n = 322) at initiation of weight management.

Frequency and type of hospital utilisation

The annual mean and median episodes of care by type of visit for the whole sample is shown in . 117 (36%) children had an inpatient stay at some point during the four-year period, and 213 children (66%) had visited the ED. Physiotherapy, general paediatrics, obesity service, dietetics and psychology were the outpatient services utilised by the highest number of children and with the highest numbers of total visits.

Table 2. Average annual hospital utilisation by type among all children in the sample (n = 322).

Relationship between hospital utilisation patterns and participant characteristics

The negative binomial regression analyses () demonstrated that having one or more comorbid condition was associated with greater numbers of total episodes of care (IRR 1.24; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.11, 1.39; p < 0.001) while being of average SES was associated with fewer total episodes (IRR 0.88; 95% CI 0.79, 0.99; p = 0.029).

Table 3. Results of negative binomial regression for types of hospital utilisation by patient characteristics.

Presence of comorbidity was positively associated with visits for the years before commencing obesity treatment (year one: IRR 1.99; 95% CI 1.43, 2.79; p < 0.001; year two: IRR 1.28; 95% CI 1.07, 1.52; p = 0.006). This was also associated with slightly more visits in the year commencing 12 months after obesity treatment (year four) (IRR 1.20; 95% CI 1.02, 1.41; p = 0.029) but not the year immediately after commencing treatment (year three: IRR 1.14; 95% CI 1.0, 1.31; p = 0.058). Older age (12–18 years) was positively associated with visits in year three (IRR 1.40; 95% CI 1.08, 1.82; p = 0.011), while in year four, average SES was negatively associated with episodes of care (IRR 0.83; 95% CI 0.71, 0.98; p = 0.024). A SUR analysis confirmed the associations between participant characteristics and hospital utilisation.

Cost implications

High and low unit costs for each type of visit were estimated based on assumptions around time, salary and activities included in each model. Variation between types of visits was predominantly due to possible length of appointments (quick review versus full assessment), differences in salary scales and additional time for clinical diagnostic tests. The cost of a missed appointment was estimated and these were included in total costs per patient.

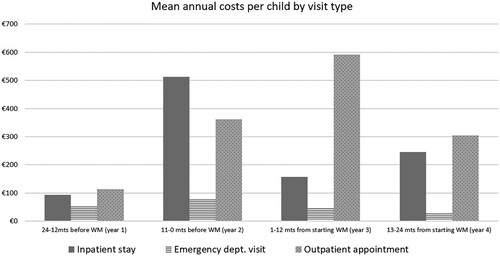

outlines the cost of hospital utilisation for each child by year and type of visit. There was a mean cost per child of €2590 for all four years (€1373 of which came from outpatient service utilisation). The year immediately prior to commencing weight management was the most costly year in terms of care.

Table 4. Annual costs associated with hospital visits per child, by type of visit according to various cost parameters.

Despite significantly higher numbers of total visits in the two years before commencing obesity treatment, there was no significant difference in episodes or costs among children with severe obesity compared to those with overweight or obesity. Children with a co-morbid condition had a significantly higher number of total hospital visits (mean 11.5, 95% CI 9.9, 13.1; p < 0.001) and higher costs (mean €1591, 95% CI 1115, 2067; p = 0.009) pre- obesity treatment compared to those without a diagnosed condition (mean episodes 8.3; mean costs €981).

In the two years after commencing obesity treatment, having a co-morbid condition was positively associated with visits (IRR 1.16; 95% CI 1.02, 1.32; p = 0.020). Being of average SES was negatively associated with visits (IRR 0.87; 95% CI 0.77, 0.98; p = 0.021). Multivariable regression analysis showed these associations to be consistent for costs in the same time period. shows the average annual costs per child by type of visit. The cost of ED visits can be seen to remain broadly similar over the four years (). also conveys high inpatient cost in the year before admission to the obesity service and higher outpatient cost in the year just after admission, which suggests that suitability for the obesity service may have been identified for some patients during their hospital stay.

For total costs over four years, multivariable regression analyses showed presence of a co-morbid condition was a statistically significant characteristic, positively associated with costs (coefficient 964; 95% CI 322, 1606; p = 0.003), and this was also significant for outpatient costs (coefficient 332; 95% CI 118, 547; p = 0.003). In a sensitivity analysis to assess costs using both the minimum and maximum cost estimates for total costs and outpatient costs over four years, this finding remained consistent.

A Cragg hurdle model did not however reveal any variation in total visits or costs according to patient characteristics for inpatient stays, outpatient visits, or total episodes of care. Presence of a comorbid condition was associated with ED related visits (p = 0.04 95% CI 0.02, 0.61), but there was no statistically significant variation among those who used the ED based on characteristics.

Discussion

We analysed patient-level hospital service utilisation at an urban paediatric hospital among a consecutive cohort of children with clinical obesity, who are by nature a vulnerable population, with the aim of describing their patterns of care, differences by characteristics, and assessing the associated costs.

A greater number of children within the sample were from areas considered to be disadvantaged (32%) than were from affluent areas (13%), which is consistent with data from studies of obesity prevalence by deprivation level (Bel-Serrat et al., Citation2017). However, we did not find evidence that the hospital costs were related to SES, though children from “average” SES neighbourhoods had fewer total visits compared to the entire sample when divided into affluent, average and deprived categories.

Within the sample, 38% of children had a co-morbid condition which could be underlying, or a complication of their obesity, or unrelated. Co-morbid conditions were the only characteristic consistently associated with higher utilisation (inpatient, outpatient and total episodes). This has not been previously shown in the ROI due to a lack of longitudinal studies (Perry et al., Citation2017). It highlights the need to ensure that care for children with multi-morbidities is delivered in a way that is integrated between paediatric specialties (Schalkwijk et al., Citation2016). Clinical paediatric services are often fragmented and exist within separate departments, and a lack of electronic health records further exacerbates the challenge of coordinating care between healthcare practitioners and across paediatric sites (Staines et al., Citation2016); issues that have been highlighted as a barrier to caring for children with obesity in various other regions also (Bel-Serrat et al., Citation2018; Dickey et al., Citation2017; Houses of the Oireachtas Committee on the Future of Healthcare, Citation2017; Johnson et al., Citation2018; Phelan et al., Citation2015).

Our study examined the costs associated with caring for children with obesity in a tertiary hospital outpatient service using an exploratory, bottom-up method. Over the four-year observation period, the mean number of care episodes was 27 per child, with an estimated cost of €2590 in total. This is broadly in line with findings from the Netherlands (Wijga et al., Citation2018) showing an annual cost of hospital care to be €498 (SD 654) for children who are overweight, although not directly comparable. These figures are difficult to compare with existing local data, as it is the first in the ROI to assess direct costs and patterns using patient-level data for tertiary paediatric care. The parameters for our cost estimates have been validated by local clinicians as acceptable estimations for direct care. The lack of information system in the ROI for surveillance of paediatric healthcare utilisation nationally means that we cannot compare service use for this population to that of the general paediatric population (Staines et al., Citation2016). While many international studies have examined hospital utilisation among similar populations, they did so in different healthcare systems and often using self- or parent-reported utilisation data (Wenig, Citation2012) and differing methods of assessing cost such as use of insurance (Trasande & Chatterjee, Citation2012). While co-morbid conditions were consistently associated with higher hospital utilisation in our findings, this association was less clear for costs once adjustments were made for those with very low costs using the hurdle model. Larger, prospectively-designed studies assessing healthcare costs in this population are warranted. While previous studies have compared healthcare utilisation between children of “healthy” weight and children with overweight/obesity (Hampl et al., Citation2007; Hering et al., Citation2009; Turer et al., Citation2013), there is a dearth of literature examining whether severity of obesity affects this. We did not identify any variation in hospital utilisation and severity of obesity, defined using age- and sex-adjusted BMI cut-offs. This is contrary to what might be expected, given that overweight and obesity are each associated with increased levels of healthcare utilisation. However, few studies have explored differences among children with obesity based on severity of obesity, and this may be an area that warrants further research. The impact of stigma in healthcare (Phelan et al., Citation2015), the association with SES (Bel-Serrat et al., Citation2018) and related complexity, increased numbers of transient families (O’Brien et al., Citation2021), or an array of other factors may lead to a delayed or lowered engagement with healthcare services among children with more severe obesity.

Further, although classifying obesity severity based on measures of body size alone (BMI centiles) is useful in epidemiological studies, this is likely not the case at the level of the individual child. Recent findings suggest that children present with impaired metabolic and mental health even at less severe levels of obesity (when obesity is classified based on body size alone) (Hadjiyannakis et al., Citation2019). Further research that uses more nuanced obesity staging classifications (Hadjiyannakis et al., Citation2016) for obesity, rather than focusing on shape and size are needed to explore whether a relationship exists between healthcare costs and obesity severity.

Implications of findings

Our findings demonstrate that this population attend a variety of paediatric specialties, many of which are clinical services addressing the common comorbidities of childhood obesity. An integrated and joined-up care approach is recommended for efficiency, economic benefits, and improving child health outcomes but barriers to such models of care include lack of information sharing between professionals and a myriad of specialties working in professional silos (Montgomery-Taylor et al., Citation2015; Rocks et al., Citation2020). We provide formative retrospective data which, despite its limitations, is the first to demonstrate tertiary hospital care for this population in the ROI. Further prospectively collected, large datasets are needed to explore the relationship between obesity in paediatric populations and common co-morbidities, to facilitate recommendations for practice.

Research is also needed to explore the long-term effect of paediatric obesity management on healthcare utilisation, while a national integrated system for collecting paediatric healthcare utilisation data is essential. An examination of 12 years of the obesity management service within CHI Temple Street has demonstrated the positive impact of a multi-disciplinary, family-orientated lifestyle intervention in reducing BMI standardised deviation score (O'Malley et al., Citation2012; Wyse et al., Citation2021), which is associated with reduced risk of complications. Investigation of whether this translates to reduced healthcare utilisation and costs is warranted. Obesity remains a highly stigmatised condition which in many countries, is not recognised as a chronic disease despite widely held expert consensus and advocacy (Farpour-Lambert et al., Citation2015; Phelan et al., Citation2015), and there is a need for continued provision of up-to-date evidence highlighting the case for supportive healthcare systems for this vulnerable population with complex needs. Our data supports the need for integrated pathways of care for childhood obesity. By the time children in our study were referred for obesity treatment, significant healthcare resources were already being used in the preceding 24 months, possibly for investigation of obesity-related complications or treatment of co-morbid conditions. As such, children are likely already engaging with health services for management of obesity-related complications and co-morbidities prior to a decision to address management of obesity itself. This suggestion is supported by data from the UK (Jones Nielsen et al., Citation2013) where a four-fold increase in rates of admission associated with obesity to paediatric hospitals was reported between 2000 and 2009. The most common reasons for admission where obesity was a co-morbidity were related to respiratory complications including sleep apnoea and asthma.

As childhood obesity registries continue to emerge internationally (Kirk et al., Citation2017), there may be an opportunity to take advantage of the implementation of a new local model of care for obesity management (Health Service Executive, Citation2021) to embed accessible data collection within services or consider development of a local registry, to overcome data needs and reduce research waste and burden. Finally, alternative means of healthcare delivery, such as through digital health, and its ability to reduce the burden of hospital attendance on families with high attendances, and/or prevent missed appointments, should be considered for future research (Tully et al., Citation2021).

Strengths and limitations

Due to its retrospective nature, we could only include services recorded in the hospital records. Our analyses were limited by the availability of only one growth measure per participant (BMI centile on referral), and we were, therefore, unable to examine the effects of changes in weight status on hospital utilisation throughout the time period assessed. Further, severity of obesity was established using cut-offs that are based on BMI centiles for age and gender, which were used in the obesity management service at the time, but diagnosing obesity on body size alone has well-documented limitations (Blundell et al., Citation2014). Our results found there to be little variation in hospital use according to patient characteristics, but further analyses on larger and more heterogeneous samples are warranted. Our data are observational and we cannot base any causality or direction of associations on the costs of resource-use based on what is presented and can only place the findings in the context of previous evidence of significantly greater hospital utilisation among children with obesity compared to those without. In addition, we assessed hospital service utilisation among a clinical population with obesity that had been referred to a Tier 3 hospital-based obesity service and cannot apply the findings to the wider population of children with obesity who are not being seen for obesity management. This study did, however, benefit from a longitudinal design with objective and detailed patient-level data from a representative cohort of children attending obesity services in Ireland. Our micro-costing approach allowed for detailed and accurate costs that would have been otherwise unavailable.

Conclusion

In summary, children attending a hospital-based obesity service had a high-level of hospital specialist service use, in addition to emergency visits and inpatient stays. Almost 40% of children referred for obesity treatment were living with at least one other comorbid condition, which significantly increased their hospital utilisation. It is vital that health professionals and health managers consider the broad impact of obesity on child health and development and recognise that though children with obesity may not be accessing specific obesity treatment services, there is a strong likelihood that they are already accessing multiple healthcare teams for investigation of obesity-related comorbidities. Furthermore, an integrated approach to ensuring holistic care for this vulnerable population is required so that both paediatric care and healthcare policy ensure adequate provision of obesity treatment, in line with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child’s with regards access to healthcare (UN General Assembly, Citation1989). This study provides formative data which may be hypothesis-generating and may inform future research questions to help describe the healthcare needs of children with obesity. There is a need for consistent and standardised national data collection on healthcare utilisation for children with obesity, to inform robust cost-of-illness studies and economic evaluations of treatment from a societal perspective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Louise Tully

Louise Tully is a Postdoctoral Researcher in childhood obesity management and health services research with the Obesity Research and Care Group at RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences.

Jan Sorensen

Jan Sorensen is a Professor of Health Economics and the Director of the Healthcare Outcome Research Centre at RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences.

Grace O'Malley

Grace O'Malley is a Clinician-Scientist in childhood obesity management, and Lecturer in physiotherapy. She leads the Obesity Research and Care group at RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences.

References

- Abarca-Gómez, L., Abdeen, Z. A., Hamid, Z. A., Abu-Rmeileh, N. M., Acosta-Cazares, B., Acuin, C., Adams, R. J., Aekplakorn, W., Afsana, K., & Aguilar-Salinas, C. A. (2017). Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet, 390(10113), 2627–2642. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3

- Asaria, M., Grasic, K., & Walker, S. (2016). Using linked electronic health records to estimate healthcare costs: Key challenges and opportunities. Pharmacoeconomics, 34(2), 155–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0358-8

- Bel-Serrat, S., Heinen, M. M., Mehegan, J., O’Brien, S., Eldin, N., Murrin, C. M., & Kelleher, C. C. (2018). School sociodemographic characteristics and obesity in schoolchildren: Does the obesity definition matter? BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5246-7

- Bel-Serrat, S., Heinen, M., Murrin, C., Daly, L., Mehegan, J., Concannon, M., Flood, C., Farrell, D., O’Brien, S., Eldin, N., & Kelleher, C. (2017). The childhood obesity surveillance initiative (COSI) in the Republic of Ireland: Findings from 2008, 2010, 2012 and 2015.

- Blundell, J. E., Dulloo, A. G., Salvador, J., & Frühbeck, G. (2014). Beyond BMI - phenotyping the obesities. Obesity Facts, 7(5), 322–328. https://doi.org/10.1159/000368783

- Children's Health Ireland at Temple Street. (2020). W82GO Child and Adolescent Weight Management Service. Retrieved 14 December, from http://w82go.ie/

- Citizen's Information. (2020). Charges for hospital services. The Citizens Information Board. Retrieved 14 January, from https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/health/health_services/gp_and_hospital_services/hospital_charges.html#

- Cole, T. (1997). Growth monitoring with the British 1990 growth reference. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 76(1), 47–49. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.76.1.47

- de Lima, T. R., Martins, P. C., Guerra, P. H., & Silva, D. A. S. (2020). Muscular fitness and cardiovascular risk factors in children and adolescents: A systematic review. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 34(8), 2394–2406. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002840

- Department of Employment Affairs and Social Protection. (2020). PRSI Class A Rates. Government of Ireland. Retrieved 13 May, from https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/ffa563-prsi-class-a-rates/

- Dickey, W., Arday, D. R., Kelly, J., & Carnahan, C. D. (2017). Outpatient evaluation, recognition, and initial management of pediatric overweight and obesity in US military medical treatment facilities. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 29(2), 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12398

- Doherty, E., Queally, M., Cullinan, J., & Gillespie, P. (2017). The impact of childhood overweight and obesity on healthcare utilisation. Economics and Human Biology, 27(Pt A), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2017.05.002

- Dooley, A. A., & Pillai, D. K. (2020). Paedatric obesity-related asthma: Disease burden and effects on pulmonary physiology. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 37, 15–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prrv.2020.04.002

- Economic and Social Research Institute. (2019). Growing up in Ireland: Physical and Health Development. Cohort ‘98 at 20 years old in 2018/19 — Key Findings No. 2. Retrieved 28April, from https://www.esri.ie/system/files/publications/SUSTAT79.pdf

- Farpour-Lambert, N. J., Baker, J. L., Hassapidou, M., Holm, J. C., Nowicka, P., & Weiss, R. (2015). Childhood obesity is a chronic disease demanding specific health care-a position statement from the childhood obesity task force (COTF) of the European Association for the study of obesity (EASO). Obesity Facts, 8(5), 342–349. https://doi.org/10.1159/000441483

- Frick, K. D. (2009). Micro-costing quantity data collection methods. Medical Care, 47(7 Suppl 1), S76. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819bc064

- Hadjiyannakis, S., Buchholz, A., Chanoine, J. P., Jetha, M. M., Gaboury, L., Hamilton, J., Birken, C., Morrison, K. M., Legault, L., Bridger, T., Cook, S. R., Lyons, J., Sharma, A. M., & Ball, G. D. (2016). The Edmonton obesity staging system for pediatrics: A proposed clinical staging system for paediatric obesity. Paediatrics & Child Health, 21(1), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/21.1.21

- Hadjiyannakis, S., Ibrahim, Q., Li, J., Ball, G. D., Buchholz, A., Hamilton, J. K., Zenlea, I., Ho, J., Legault, L., & Laberge, A.-M. (2019). Obesity class versus the Edmonton obesity staging system for pediatrics to define health risk in childhood obesity: Results from the CANPWR cross-sectional study. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health, 3(6), 398–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30056-2

- Hampl, S. E., Carroll, C. A., Simon, S. D., & Sharma, V. (2007). Resource utilization and expenditures for overweight and obese children. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 161(1), 11–14. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.1.11

- Hasan, T., Ainscough, T. S., West, J., & Fraser, L. K. (2020). Healthcare utilisation in overweight and obese children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 10(10), e035676. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035676

- Health Information Quality Authority. (2019). Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies in Ireland. https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/2019-07/HTA-Economic-Guidelines-2019.pdf

- Health Service Executive. (2019a). HR Circular 034/2019: Standardisation of Annual Leave Health and Social Care Professionals. Office of the National Director of Human Resources. Retrieved 13 May, from https://www.hse.ie/eng/staff/resources/hr-circulars/hr-circular-034-2019-re-annual-leave-for-health-social-care-professionals.pdf

- Health Service Executive. (2019b). Payscales for HSE Staff. Retrieved 5 August 2020, from https://www.hse.ie/eng/staff/benefitsservices/pay/

- Health Service Executive. (2021). Model of Care for Management of Overweight and Obesity. https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/cspd/ncps/obesity/model-of-care/obesity-model-of-care.pdf

- Hering, E., Pritsker, I., Gonchar, L., & Pillar, G. (2009). Obesity in children is associated with increased health care use. Clinical Pediatrics, 48(8), 812–818. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922809336072

- Hernández-Herrera, G., Navarro, A., & Moriña, D. (2020). Regression-based imputation of explanatory discrete missing data. arXiv preprint, http://arxiv.org/abs/2007.15031v1

- Houses of the Oireachtas Committee on the Future of Healthcare. (2017). Slaintecare report.

- Jabakhanji, S. B., Sorensen, J., Valentelyte, G., Burke, L. A., McElroy, B., & Murphy, A. (2021). Assessing direct healthcare costs when restricted to self-reported data: A scoping review. Health Economics Review, 11(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-021-00330-2

- Johnson, R. E., Oyebode, O., Walker, S., Knowles, E., & Robertson, W. (2018). The difficult conversation: A qualitative evaluation of the ‘Eat well move more’ family weight management service. BMC Research Notes, 11(1), 325. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3428-0

- Jones Nielsen, J. D., Laverty, A. A., Millett, C., Mainous Iii, A. G., Majeed, A., & & Saxena, S. (2013). Rising obesity-related hospital admissions among children and young people in England: National time trends study. PLoS One, 8(6), e65764. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065764

- Kaplan, R. S., & Anderson, S. R. (2003). Time-driven activity-based costing. Available at SSRN 485443.

- Keel, G., Savage, C., Rafiq, M., & Mazzocato, P. (2017). Time-driven activity-based costing in health care: A systematic review of the literature. Health Policy, 121(7), 755–763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.04.013

- Kirk, S., Armstrong, S., King, E., Trapp, C., Grow, M., Tucker, J., Joseph, M., Liu, L., Weedn, A., & Sweeney, B. (2017). Establishment of the pediatric obesity weight evaluation registry: A national research collaborative for identifying the optimal assessment and treatment of pediatric obesity. Childhood Obesity, 13(1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2016.0060

- Mitchell, L., Bel-Serrat, S., Stanley, I., Hegarty, T., McCann, L., Mehegan, J., Murrin, C., Heinen, M., & K, C. (2020). The Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI) in the Republic of Ireland - Findings from 2018 and 2019. https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/healthwellbeing/our-priority-programmes/heal/childhood-obesity-surveillance-initiativecosi/childhood-obesity-surveillance-initiative-report-2020.pdf

- Montgomery-Taylor, S., Watson, M., & Klaber, B. (2015). Child health - leading the way in integrated care. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 108(9), 346–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076815588315

- O'Malley, G., Brinkley, A., Moroney, K., McInerney, M., Butler, J., & Murphy, N. (2012). Is the Temple Street W82GO healthy lifestyles programme effective in reducing BMI SDS? 833 accepted poster. Obesity Facts, 5.

- O’Brien, N., Joyce, B., Bedford, H., & Quinn, N. (2021). 1146 Emergency department utilisation by homeless children in Dublin, Ireland. (Ed.), (Eds.). British Association of Child and Adolescent Public Health.

- Perry, I. J., Millar, S. R., Balanda, K. P., Dee, A., Bergin, D., Carter, L., Doherty, E., Fahy, L., Hamilton, D., Jaccard, A., Knuchel-Takano, A., McCarthy, L., McCune, A., O’Malley, G., Pimpin, L., Queally, M., & Webber, L. (2017). What are the estimated costs of childhood overweight and obesity on the island of Ireland?

- Phelan, S. M., Burgess, D. J., Yeazel, M. W., Hellerstedt, W. L., Griffin, J. M., & van Ryn, M. (2015). Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obesity Reviews, 16(4), 319–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12266

- Pobal. (2019). Pobal maps: information supporting communities. Retrieved 31 October, from https://maps.pobal.ie/

- Quek, Y. H., Tam, W. W., Zhang, M. W., & Ho, R. C. (2017). Exploring the association between childhood and adolescent obesity and depression: A meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews, 18(7), 742–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12535

- Reilly, J. J., & Kelly, J. (2011). Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: Systematic review. International Journal of Obesity (London), 35(7), 891–898. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.222

- Rocks, S., Berntson, D., Gil-Salmerón, A., Kadu, M., Ehrenberg, N., Stein, V., & Tsiachristas, A. (2020). Cost and effects of integrated care: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. The European Journal of Health Economics, 21(8), 1211–1221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-020-01217-5

- Schalkwijk, A. A. H., Nijpels, G., Bot, S. D. M., & Elders, P. J. M. (2016). Health care providers’ perceived barriers to and need for the implementation of a national integrated health care standard on childhood obesity in the Netherlands - a mixed methods approach. BMC Health Services Research, 16), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1324-7

- Staines, A., Balanda, K. P., Barron, S., Corcoran, Y., Fahy, L., Gallagher, L., Greally, T., Kilroe, J., Mohan, C. M., Matthews, A., McGovern, E., Nicholson, A., O'Farrell, A., Philip, R. K., & Whelton, H. (2016). Child health care in Ireland. The Journal of Pediatrics, 177, S87–S106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.046

- Trasande, L., & Chatterjee, S. (2012). The impact of obesity on health service utilization and costs in childhood. Obesity, 17(9), 1749–1754. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2009.67

- Tully, L., Case, L., Arthurs, N., Sorensen, J., Marcin, J. P., & O'Malley, G. (2021). Barriers and facilitators for implementing paediatric telemedicine: Rapid review of user perspectives [systematic review]. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 9, 180. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.630365

- Turer, C. B., Lin, H., & Flores, G. (2013). Health status, emotional/behavioral problems, health care use, and expenditures in overweight/obese US children/adolescents. Academic Pediatrics, 13(3), 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2013.02.005

- UN General Assembly. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. United Nations, Treaty Series, 1577(3).

- Weiss, R., & Kaufman, F. R. (2008). Metabolic complications of childhood obesity: Identifying and mitigating the risk. Diabetes Care, 31(Supplement 2), S310–S316. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-s273

- Wenig, C. M. (2012). The impact of BMI on direct costs in children and adolescents: Empirical findings for the German healthcare system based on the KiGGS-study. The European Journal of Health Economics, 13(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-010-0278-7

- Wijga, A. H., Mohnen, S. M., Vonk, J. M., & Uiters, E. (2018). Healthcare utilisation and expenditure of overweight and non-overweight children. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 72(10), 940–943. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2017-210222

- World Health Organization. (2021). Obesity and overweight: key facts. WHO. Retrieved 5 September, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- Wyse, C., Case, L., Barrett, G., Muldoon, M., Jordan, N., Mccrea, L., Flanagan, R., Delaney, S., Tully, L., Arthurs, N., Dow, M., & O’Malley, G. (2021). Evaluating 12 years of Implementing a Multidisciplinary Specialist Child and Adolescent Obesity Treatment Service: Patient-Level Outcomes. (Ed.), (Eds.). European Congress on Obesity Late Breaking Abstracts, Online.

- Yangyang, R. Y., Abbas, P. I., Smith, C. M., Carberry, K. E., Ren, H., Patel, B., Nuchtern, J. G., & Lopez, M. E. (2016). Time-driven activity-based costing to identify opportunities for cost reduction in pediatric appendectomy. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 51(12), 1962–1966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.09.019

- Zhao, K., Ju, H., & Wang, H. (2019). Metabolic characteristics of obese children with fatty liver: A STROBE-compliant article. Medicine, 98, 16.