ABSTRACT

Human bodies are typically buried underground, horizontally ‘in repose’. To the extent that this orientation has become the standard; it is a non-choice that is under-interrogated by scholars. In this paper, we discuss innovations which allow for the vertical orientation of the body within the earth and for the vertical stacking of remains above the earth in high-rise structures. Both of these boundary-pushing forms of disposition address imminent shortages in the land allocated for cemeteries in the context of intense urbanisation and a peaking death rate. They also promise to transform the necrogeography of contemporary cities and intimate relations between the living and the dead. This paper is a collaboration between the DeathTech Research Team and the Managing Director of Upright Burials, where the dead are ‘stood to rest’ in shaft graves. The pragmatic advantages of vertical burial are easily explicated, but in this paper, we focus on the cultural and symbolic dimensions of this largely unfamiliar spatial relation and the challenges of ‘reorienting’ the public towards this new form of disposition.

The intriguing diagram pictured in comes from a patent for a self-contained, screw-in, vertical coffin, called the ‘easy inter burial container’, which was first lodged with the United States Patent Office in 2006 (#US20070050958A1). In this system, a human body is loaded into the top of the capsule, feet first, the lid is secured, and then the unit is slowly screwed into the ground via a mechanism of pinwheel batons. Mourners may be invited to participate in the burial not just by attending but also by doing the work. The casket is completely sealed and can also be used underwater. For those suffering taphophobia, there is even an option to instal a two-way hatch. By burying bodies upright, this design promises to significantly increase a cemetery’s ‘yield’, that is, the number of interments per allotment. Maximising yield is a central concern of contemporary cemetery planning, particularly in societies that are moving towards a precipitous increase in the numbers of the dead, as the populous baby boomer generation ages (Basmajian & Coutts, Citation2010), and where the population is concentrated in cities and mega-cities. There are many reasons why one might view this design as outlandish, including the tension it generates between whimsy and death, the idea of working up a sweat during a formal funeral ceremony, or scepticism at the apparent inefficiency or impracticality of the design, particularly in hard or rocky soils. However, we believe there is another more fundamental aspect to the discomfort: the vertical orientation of the dead. It is this alternative orientation for the dead that we wish to explore in this paper, initially through an overview of how the orientation of the body in the ground has been managed and understood over time, and then with particular reference to a case study of vertical burial practice in Victoria, Australia.

The material treatment of the corpse and its position in the landscape has evolved in concert with the infrastructure and landscape of settlements, religious sites, and cemeteries. Despite the numerous potential methods for treating human remains, burial and cremation have dominated funeral cultures throughout time and around the globe. Further, with notable exceptions, burial overwhelmingly occurs ‘in repose’: the body is laid out in a supine position with legs extended and arms folded with hands placed on the stomach. This supine disposition shapes everything from the technologies of disposal, including the size and materials of the coffin and the labour required to dig graves, to the landscape of the cemetery park itself. Within contemporary lawn cemeteries, burial occurs in a single layer; not only is the body horizontal, but the vertical space above and below it is free. The widespread exception to this practice in Victoria are co-burials of up to three bodies (usually kin) in a single plot with a 40 cm separation of earth. Vertically stacked supine interment also occurs at mausoleums, which remain popular, for example, amongst Southern European communities in Australia. Archaeologist Sian Mui (Citation2019) argues that the supine body position is so common within modern burial culture and its representation in popular media that it is frequently assumed to be natural or universal, and as a result, the semiotic or symbolic potentials of body orientation – supine or otherwise – are under-explored.

Although dominant, supine burial is by no means universal. Outside of the context of contemporary Judaeo-Christian burial culture, there exist diverse traditions for the positioning human remains, from the foetal position of Beaker burials,Footnote1 to Jain ascetics who have been mummified in a seated position (see Mui, Citation2019; Sprague, Citation2005). Sian Mui (Citation2018) identifies seven main types of deposition operating within early Anglo-Saxon England burial culture alone. For most extant archaeological examples of what might be called ‘vertical burial’, the dead are situated in a crouched position within a shallow shaft. Other examples of non-supine burial represent individual interments that appear unconventional or deviant within a given burial culture, for example, mass graves, burials of enemies, and burials of those accused of supernatural activities (for example, see Gregoricka et al., Citation2014). There are also those burials that are highly idiosyncratic; for example, in 1800, the eccentric Major Peter Labelliere was interred vertically, head-first, in Box Hill, England (Timbs, Citation1877). In some exceptional contexts, supine burial may even connote a bad death. For example, Cheryl Claasen argues that in southern Ohio Valley in the Archaic period (ca. 5000–2000 BC), supine burials were associated with violent death, punishment, or human sacrifice (Citation2010: 114–120). Clearly, the position of the corpse in the burial deposition is a potentially meaning-laden cultural practice, one that archaeologists have become adept at interpreting. With the emergence of new technologies for treating and storing human remains, many of which diverge from supine burial, corpse orientation becomes an increasingly pertinent consideration for death studies scholars more generally.

As we will show, corpse orientation anchors the spatial relationship between the living and the dead, and significantly affects the design of cemeteries and their location in the landscape. The study of ‘necro-geography’, or spaces ‘associated with burial and other forms of body disposition and associated remembrance practices’ (Maddrell, Citation2020, p. 167) is a growing field at the intersection of death studies and cultural geography. Initially focused on official sites of disposition like cemeteries, it has expanded to encompass a wider range of online and offline, informal and formal locations associated with dying, death, and mourning, including the body itself as ‘a geographical space of experience and expression’ (Maddrell, Citation2020, p. 167). Crucially, the study of necro-geographies recognises the significance of space as an actor in events and meanings, not just a neutral backdrop or container to activity (Maddrell & Sidaway, Citation2010, p. 2). Just as geographers have recently been called to question the ‘dominant horizontalism’ that ‘privilege[s] the horizontal extension of cities to the neglect of their vertical or volumetric extension’ (Hewitt & Graham, Citation2015, p. 924), in this paper we argue that so too must death scholars reorientate their thinking on cemeteries to consider the vertical dimension.

Over the last three years, the DeathTech Research Team, based at the University of Melbourne, has been examining the potential of alternatives to and variations of conventional disposition methods for human remains. Among our interests are how these new forms of disposal are represented to the public via metaphor, analogy, and political rhetoric. Alternatives to and elaborations of conventional burial and cremation currently exist in various states of development, from the speculative imaginary, to scientific testing of proof-of-concept, to capital raising and then early commercial deployment. Examples are Recompose, a company providing a method of composting human remains that is set to open its first facility in Seattle in 2021 (https://www.recompose.life); Constellation Park, an architectural imaginary for a structure of bio-luminescent pods suspended beneath Brooklyn Bridge (http://deathlab.org/constellation-park/); and Promessa, a process for freeze-drying and then pulverising human remains via vibrations (http://www.promessa.se), which, at the time of writing, remains in the proof-of-concept stage. Many new disposition methods sit at the outer limits of imagined techno-futures, existing only in patents, prototypes, and architectural designs. Many never progress past this stage, which appears to be the case with the aforementioned screw-in coffin; the patent was registered by serial inventor Donald Scruggs over a decade ago, but does not appear to have passed the prototype phase (PBS, Citation2012).

Vertical burial, however, is more than an imaginary. It is a commercially viable operation at Kurweeton Road Cemetery in Victoria, Australia, and although interment numbers to date are small , it provides an increasingly popular alternative to these conventional methods. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first and only facility in the world to offer a vertical burial service, in which bodies are placed feet-first into deep graves, excavated with the assistance of a rotary auger usually used to dig post-holes. In this paper, we introduce this emerging form of disposition and contrast it with other forms of necro-architecture that utilise the vertical dimension in above-ground urban space. By presenting these examples in concert, we seek to identify and name a growing trend in contemporary disposition practice, and so provoke future study of the pragmatic and symbolic value of both verticality and hortizontalism in the deathcare sphere. Given the hegemonic dominance of horizontal disposition, verticality has been under-utilised by cemeteries and under-examined by scholars hitherto, but may become an important future resource for the disposition of the dead, particularly in densely-populated areas, with the potential to transform urban necro-geographies.

This paper is co-authored by members of the DeathTech Research Team and Tony Dupleix, the owner and operator of Upright Burials at the Kurweeton Road Cemetery. Throughout the team’s near-decade of research into questions at the intersection of death, society, and technology, collaborations with industry – particularly in behind-the-scenes spaces of funerary practice – have proved essential. The collaborative writing of this article draws on and acknowledges the expertise and time commitment that deathcare professionals have contributed to this project.

Standing to rest in Kurweeton

Located approximately two hundred kilometres west of Melbourne, in the plains below Mount Elephant, an inactive volcano, and surrounded by fertile farmland, is Kurweeton Road Cemetery (). Driving up the dirt road to the cemetery, very little is visible to distinguish it from its rural surrounds, with the exception of some volcanic rocks and a small memorial wall which marks this as the site where bodies have been interred since 2010. From its conception in 1984 by a group of local farmers and friends imagining possibilities over several glasses of wine, it took twenty-six years for the cemetery to evolve into the working reality that exists now. George Lines, a local agricultural consultant, first initiated the concept of a vertical burial business, created the burial service trust, and secured the first round of investment.Footnote2 The unique legislative context for cemeteries in the state of Victoria, governed by The Cemeteries and Crematoria Act 2003, stipulates that all cemeteries must be located on Crown (public) land and managed by not-for-profit trusts. The process of establishing Kurweeton thus began with convincing a local farmer to donate the land and negotiating with the Darlington Cemetery Trust to oversee the management of the site. The Upright Burials company has exclusive rights to inter bodies at Kurweeton, and this is run by Tony Dupleix, who lives on a property near the site, where they produce prime lamb. Landholders adjoining the cemetery grow wheat, canola, and fava beans. Several founding unitholders of the Upright Burial Trust have been buried at Kurweeton Cemetery, including the wife of George Lines. The first burial was a Vietnam War Veteran, Allan Heywood from Skipton South West Victoria, on the 4th of October 2010. At the time of writing, sixty-five burials have taken place, there have been over 150 pre-paid reservations, and over 1000 registrations of interest or intent.

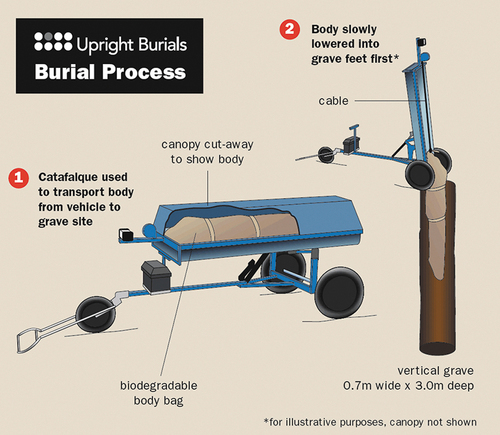

The Upright Burial service is promoted under the slogan: ‘simple, natural, economical’ and this phrase very much captures the ethos running through the entire operation. The cemetery is only four hectares (40,000 m2) but has the capacity for approximately 30,000 graves. Each grave is 70 centimetres in diameter and three metres deep. It occupies a 1.2 by 1.2 metre square on a grid that runs across the entire cemetery-cum-paddock, and this surface space constitutes approximately one-third the land footprint of a conventional burial. The location of each burial is recorded via a series of letters running along one axis and numbers along the another, that are fixed to the wire farm-fence that is also the cemetery fence, demarcating a grid (). A plaque erected on a wall near the entrance to the cemetery/paddock lists the deceased’s name, date of birth and death, and their location on the grid. The graves are excavated shortly before interment with a mechanical auger or drilling device, which is also used by the community to dig holes for electricity poles and building foundations. The dead arrive at a cold storage facility on Tony’s property already wrapped in a leakproof and odour proof shroud, made from a biodegradable material of cornstarch and hessian. Freezing assists in the process of lowering the body into the vertical shaft. Bodies are then committed to the earth via a specially designed, battery-operated, vertical catafalque (see ). Each burial at Kurweeton, at the time of writing, costs a one-time, all-inclusive fee of 3,250 Australian dollars. This is highly competitive in comparison to the average current cost of burial in Victoria, which is 5,600, AUD, exclusive of a headstone and funeral (Gathered Here, Citation2019) and at some locations exceeds 30,000 AUD (for example, Melbourne General Cemetery). At Kurweeton, bodies are lowered into the ground feet-first and facing East. In discussions with press and interested customers, this orientation has invoked romantic associations with ‘facing the rising sun’, and it also carries cultural and religious significance (see Lacquer, Citation2015, p. 123-126). However, Tony notes that feet first, facing East just happened to be the easiest direction as a result of manoeuvering the catafalque into the paddock. A few people have subsequently asked to be buried headfirst. Indeed one potential customer indicated this preference as an intentional insult to ‘the whole system’. However, Tony refuses to do so, not because he has any particular objection, but because, in his own words, he wants to run a 'regular, widely accessible and acceptable service', rather than one that might be seen to 'appeal only to cranks and misanthropes', and be likely to stir up negative sentiments. As we shall describe, vertical burial has been challenging enough for people to accept, without accusations of it being disrespectful, disgusting, or ungodly.

Conservation of resources and conservation of space are the two primary narratives drawn upon by the Australian media and advocates of the practice to explain and promote the upright burial service. Embalming, which has been and remains generally unpopular across Australia (Van der Laan & Moerman, Citation2017, p. 7), is not permitted at the cemetery, nor is the use of cement or plastic grave-liners, or other materials that resist the decomposition process. For every burial, a tree is planted on nearby Mount Elephant to offset the minimal energy consumption and carbon emissions from transport and storage, and the catafalque and freezer are re-charged using the farm’s solar panels. The cemetery also tries to minimise the transportation miles used to travel to and from the site, both of people and resources. In Australia, monumental headstones for graves are often shipped from China, but at Kurweeton Cemetery, no stone markers are used. Tony has recently received permission to place volcanic rocks from the area on cemetery ground, although they are to be used as habitats for native fauna, and not as individuated grave markers. Potential inter-state clients are gently discouraged and asked to source a natural burial solution closer to home, although two such burials have taken place at the clients’ insistence. Approximately half of the interments come from metropolitan Melbourne (2.5 hours drive away), and Tony encourages the bereaved to keep numbers at the committal to a minimum in order to limit the environmental impact of travel.

Another ecological consideration involves the preservation of flora and fauna at the site. Tony asks that mourners do not bring flower bouquets to the site, as the seeds from imported flowers might spread over the landscape via the wind. Indeed, this was an initial concern raised by local farmers when the cemetery was first proposed at this site. The cemetery is not irrigated and is covered in phalaris tuberosa, a remnant pasture species of grass from previous farming, which is slowly dying off and being replaced by Wallaby Grass (Austrodanthonia spp., formerly Danthonia), an indigenous species. The irrigation of lawn graves to maintain a lush appearance is a significant environmental cost incurred at conventional cemeteries. Instead, at Kurweeton, the farmer who originally owned the land continues to run sheep over it about twice a year, which helps to control the grass, reduce the fuel load, aid fire control, and export nutrients from the site. If people do bring flowers to the site, Tony routinely buries them in the grave with the deceased, with the consent of the mourners present. However, because under Victorian law this is a public cemetery, there is very little that he can do to enforce these protocols, and in addition to flowers, some people have begun to attach plastic signs or metal trinkets to the fence as vernacular grave markers or mementos. Similar restrictions on grave markers and other memorials at natural burial sites throughout Europe have raised controversy around this form of disposition, with some arguing that it contributes to a culture of death denial, whilst others argue that it simply reformulates the place of the dead within the society of the living (see Davies & Rumble, Citation2012, p. 47).

Whether or not this form of disposition falls under the banner of ‘natural’ or ‘green’ burial is open to significant debate. The terms ‘natural’ and ‘green’ have a contested designation in this arena (Davies & Rumble, Citation2012: 1–3; Clayden et al., Citation2015: 1). Advocates for alternative methods of disposition often align themselves with these labels. Their claims to environmentalism range from a scientific fine-tuning of the decomposition process to produce fertile soils, to more romantic naturalism, in which the body is laid down in a shallow grave. In an age of the Anthropocene, human interventions have radically transformed the ecosystem such that ‘nature’ becomes a myth; indeed, the Kurweeton Cemetery is located on colonised land never ceded by its original owners, that has been radically transformed by generations of settler agriculture. This colonial landscape transformation follows the interventions of Indigenous Australians, who over 60,000 years and more, also altered the landscape. The primary grounds upon which the ecological credentials of Upright Burial is contested is the rate of decomposition that this deep deposition of the body allows. Burial depth is one the most significant factors influencing the rate of gross post-mortem decomposition (Mann et al., Citation1990; Schultz, Citation2007), however, calculating the exact interval of decomposition is a complex process, dependent on the interaction of site-specific factors (Forbes et al., Citation2017, pp. 221–222). Some natural burial advocates suggest that shallow burialFootnote3 is necessary to enable rapid, aerobic decomposition to take place and thus for the body to ‘contribute nutrients back to the local ecosystem’ (Interlandi, in High, Citation2016, p. 509). Charles Cowling of The Good Funeral Guide states that (Cowling, Citation2010, p. 25):

A dead body will nourish the environment best if it can decompose aerobically. This means burying it in the layer of the soil where bugs and microbes abound, normally the top two feet.

In vertical burial, only the topmost part of the body is available for immediate decomposition in this manner. However, Tony states that in his experience, digging a grave shaft creates a ‘chimney’ of organic matter across which microbial life slowly travels from the topsoil as decomposition occurs. Even at lower levels at the bottom of the shaft, ‘you can see roots, insects, mycelium and other forms of life. I believe if there’s life, there’s death and therefore decay’. Moreover, for Tony, decomposition of the body at a slower rate is not necessarily a negative outcome, as the depth prevents the immediate release of some more environmentally harmful bi-products of decomposition, including methane, ammonia-based compounds, and phosphoric or potassium gasses. And further, he notes that the vast majority of the human decomposition process, especially where it is not interrupted by interventions like embalming, occurs anaerobically, beginning from the internal organs shortly after death. Still, burial depth has become a contested measuring stick of green burial, one that is particularly important in discourses that emphasise a ‘return to nature’. More so than any other green credential, however, Tony operates on the principle of energy economy. Kurweeton Cemetery is thus best understood as an attempt to re-think the resources that are devoted to burying the dead.

Cemeteries as spaces of sleep

Maximising yield for burials, while meeting community expectations and aesthetics, is a central concern of contemporary cemetery planning in Australia. In many locations worldwide, space for cemeteries in urban areas is increasingly sparse.Footnote4 An increase in cremation rates in Australia, now close to 70% (Van der Laan & Moerman, Citation2017, p. 6), has not entirely eased the increased demand for burial plots, as the death rate approaches a peak, when Baby Boomers, Australia’s most populous generation, age and die. Cemeteries in Victoria more specifically face government restrictions on two fronts. On the one hand, Victorian graves are sold in perpetuity rather than through time-limited leases, which prohibits re-use of the land (Jalland, Citation2006, p. 304). On the other hand, the practice of ‘land banking’, or the pre-emptive purchase of sites for predicted future growth, is also prohibited, which can limit a cemetery’s future-proofing activities. Cemeteries must also compete with other desires for use of urban green space, such as parkland, nature reserves or sports facilities, and contend with social taboos around living adjacent to cemeteries, all of which mean that cemetery planning is an increasingly challenging task.

These are not, however, new challenges. In many ways, the history that has been written of the modern cemetery thus far is one of horizontal spatial expansion and resistance to that expansion. In churchyard burial grounds of the 18th and 19th century, which were located in the heart of cities and villages across Europe, corpses were usually stacked many-high and coterminous space was at a premium. In response to concerns for sanitation and public health, influenced by the lingering influence of the miasma theory of disease, burial reform emerged throughout England and France in the 19th century. As Pat Jalland so evocatively summarises ‘overcrowded city burial grounds choked with corpses’ were replaced with large cemeteries outside towns ‘which distanced the noxious dead from the living’ (Jalland, Citation2006, p. 304). This burial revolution was delayed in Australia, however, perhaps because early settlers did not imagine the huge population growth that would one day transform Sydney and Melbourne into megacities. Years of public debate eventually resulted in cemeteries being pushed to the suburban fringes.

The modern lawn cemetery of the twentieth cemetery took inspiration from early Memorial Parks in the United States (such as Forest Lawn in California and Mount Auburn in Massachusetts) and cemeteries of England (such as Kensal Green in London) (Jalland, Citation2006, p. 316). These cemeteries became destination locations for escaping the crowded heart of the city, as well as a means for state and local governance over any potential pollutants spread by the dead. As part of a broader sanitising and civilising mission, the aesthetic value of these landscapes was a strong part of their appeal for town planners (Jalland, Citation2006, p. 316):

the aesthetic value of the beauty of nature in a lovely park was expected to evoke appropriate emotional responses to death: it should act as a civilising influence and source of moral instruction

In this manner, urban cemeteries have progressively encroached into peri-urban and rural spaces as they have expanded to meet the practical, public health, and aesthetic demands of the city. This trend continues today in urban Victoria.

What is under-appreciated within this history is the extent to which contemporary necro-geography is determined by the overwhelming preference for the supine orientation of the dead. Modern cemetery design is dominated by vast vistas of parallel graves aligned in neat rows with winding paths in between. This design owes much to the deep metaphorical entanglement between death and sleep within the Judaeo-Christian tradition (Hallam & Hockey, Citation2001). Indeed, the etymology of the English word ‘cemetery’ derives from a Greek work koimhthrion and its Latin cognate coemeterium meaning ‘sleeping place’ or ‘dormitory’ (Lacquer, Citation2015, p. 120). Many cemeteries feature memorials in the form of beds, where the dead are laid out peacefully, in white nightdresses and veils. Cathedrals in Britain contain raised tombs topped with intricately carved figures of renowned kings, saints, or religious leaders lying horizontally in full regalia. Their eyes are closed in sleep, with hands pressed together in prayer – an everlasting image of sleep that hovers above the remains of the body interred within the tomb. Sleep implies the arrestment of decay and a suspension of time: in contemporary mortuary practice, the displayed dead are made up to appear ‘at peace’, their eyes closed as if in a dream. In Christian theology, this slumber might be quite short, before the Second Coming and the (corporal) resurrection of the dead. Philippe Ariès relates the recumbent burial in Western Europe to practices in ‘primitive Christianity’, including 13th-century liturgy which stipulated that dying people lie on their back with their face turned towards heaven (Ariès, Citation1974, p. 9). Arms were often ‘outstretched, in the manner of a worshipper’ (1974: 8). This position was an integral part of a broader death bed practice, during an era that Ariès labels ‘tamed death’, in which people were aware of, and prepared for, their end.

Although medieval liturgy appears far removed from today’s practices, these culturally inflected ideas retain currency in contemporary burial culture. The idea of rising to heaven or falling to hell after death has emerged as a theme in some popular responses to the Kurweeton cemetery. Tony once received a complaint from a local resident which suggested that being buried upright would lead to people’s feet burning on the fires of hell. At around the same time, Elizabeth Fournier in The Green Burial Guidebook wrote the following about upright burial: ‘I … like to think being interred in an upright orientation would make one much more aerodynamic, making it easier to float to Heaven more quickly’ (Fournier, Citation2018, p. 38). Meanwhile, an objection to the launch of the upright burial service at Kurweeton involved rumours that this is how inmates were buried at Pentridge Prison, a now-closed, high-security facility located in Melbourne, as well as the idea that prisoners were made to dig their own (vertical) graves before being interred therein. Interestingly, recent archaeological investigations at the site did not uncover any evidence of this practice in the prison (Smith, Citation2011).

Imaginaries around verticality are not only revealing of beliefs about heaven and hell and taboo hidden places (like prisons), but challenge ideas about the stillness of decomposition. When buried upright as at Kurweeton, the body rapidly collapses onto itself as it decomposes, displacing the soil above by approximately 90% of the body’s total volume, requiring significant mounds of topsoil to be used as backfill – although this is generally less displacement than might occur with the decomposition of the coffin and empty airspace in conventional burial. This mobility of remains is, perhaps, a more active after-life than some might imagine for themselves and loved ones. Taken to its extremes, the animated or lively corpse evokes cultural imaginaries of the undead or zombies, who reach up out of their resting place below ground to threaten the living via plague or violence (Luckhurst, Citation2015). Zombies, as Roger Luckhurst and others have argued, are boundary-enforcing figures that can ‘act as a warning to observe the proper social protocols of mourning’ (Luckhurst, Citation2015, p. 3). Rich cultural associations cement supine burial as a normative, good death, and going against these norms can give rise to powerful fears.

Contemporary cemeteries, including memorial parks and lawn graves, are not purely horizontal landscapes and their vertical dimensions deserve greater scholarly attention. Hewitt and Graham suggest that social science has ‘long prioritised a flat, planar or horizontal imaginary of urban space over a volumetric or vertical one’, and as such, cities have overwhelmingly been explored in terms of ‘distributions, concentrations, stretched-out topologies, corridors, networks, sprawl and extending urban regions’ (Graham & Hewitt, Citation2013, p. 925). They trace this bias to the dominance of the top-down topographical gaze. It is a gaze reflected in maps of cemeteries, and the visual orientation of the living as they gaze down on the supine dead. But there are other dimensions to explore. Vertical design elements characterise cemeteries of different time periods, often forming striking monumental landscapes. Cypress trees, for example, are a common feature of cemeteries throughout the West. According to The Greater Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust, they are used to mark the boundaries of consecrated ground and as a hedge to visually separate the cemetery from adjacent residential areas, but they also are considered to carry a more symbolic meaning of hope, ‘as the tree points to the heavens’ (Penney, Citation2016, p. 4).Footnote5 Grand stone epitaphs, angelic sculptures that usher the deceased to heaven, and monumental obelisks are also prominent markers in the visual landscape of the cemetery. Cemeteries such as Père Lachaise in Paris feature artistic monuments as elements of inspiration and instruction to visitors and become an alternative model to the lawn grave memorial park . As well as marking the place of the dead in the world of the living, these monuments also speak to the relative social status of the deceased and their community’s ability to gather financial resources. Ray Browne, in his study of ‘graveyards as fetishes’ (Browne, Citation1982), further suggests a link between ‘phallic verticality in the rural cemetery’ and the ‘sentimentally fierce denial of death’ during the late 19th century in North American culture. Drawing on the connection between mortuary and fertility symbolism first suggested by Bloch and Parry (Citation1982), Browne argues (Browne, Citation1982, pp. 138–139):

When the culture needed strongly to deny death, it projected its fertility symbols higher, making them unconsciously symbolic of the body part whose loss signifies death in the male psyche, and whose presence denies that death.

In this manner, both the vertical and horizontal planes have been used in different ways by cemetery architects of different generations not only to deal with the problem of human remains but to symbolically and practically position the dead within the world of the living. As horizontal space is increasingly limited, cemeteries around the world have begun to utilise the vertical dimension in new forms of necro-architecture, and these structures have the potential to radically re-orientate people’s social and spatial relationship to the dead.

High-rises for the dead

In the twenty-first century, verticalism has become a means to organise life. High-density living is now a vanguard for sustainable land management and its ‘stacking morphology’ has been applied to almost every building type, from offices, university campuses, and apartments, to sports facilities and even green spaces (Hariyono, Citation2015). The 2000s were history’s single greatest decade of skyscraper construction (Lamster, Citation2011). Vertical structures not only maximise horizontal urban space, they also present visual features that shape the identity of a skyline, often becoming an icon for a city and its community. Like monumental gravestones and cemetery structures, they thus offer opportunities for place-making. As Hariyono suggests (Hariyono, Citation2015), cemeteries, alongside zoological gardens, appear uniquely resistant to redesign along the vertical plane, given their inhabitants. However, in several urban centres that are quickly running out of space for the dead, vertical necro-architecture is emerging as a practical and aesthetic solution, which also creates unique experiences of necro-sociality. The following three examples of these new and challenging forms reveal the possibilities that verticality affords.

The Memorial Necrópole Ecumênica, located in Santos, Brazil, holds the title for the tallest cemetery building in the world. Opened in 1983, it currently stands at fourteen stories high with places for over 14,000 interments, and there are plans for rapid expansion up to forty stories and 25,000 plots in coming years (https://memorialsantos.com.br/historia). Reflecting Brazil’s multi-ethnic and religious community, the facility contains spaces for a range of different disposition styles, including mausolea vaults, columbaria (facilitated by an on-site crematorium) and below-ground burial plots and grottos. Mausolea tombs are equipped with a sophisticated ventilation system, can accommodate multiple bodies, and after the dead body has approximately three years of decomposition time, the family of the deceased can have the body exhumed or transferred to the building’s ossuary. This system greatly increases the overall yield capacity of the cemetery, which is located in a region of dense urbanisation and limited space for the dead. The building also contains several funeral halls, a crematorium, a café, and a garden, where visitors can enjoy green-space and where a population of toucans are bred. Indeed, the natural setting on the foot of a mountain is a strong drawcard for the facility, which features open rows of mausolea that look out across luscious tropical gardens, koi ponds and private family gravesites. The facility has inspired other projects for vertical high-rises around the world, including in Mumbai and Mexico City (see Elliot, Citation2018), although their progress past the architectural imaginary stage is uncertain.

A continued preference for whole-body burial amongst those of Catholic, Muslim, and Jewish faiths can exacerbate pressures on cemetery space within urban centres. Such is the case in many cities in Israel, with Jerusalem alone requiring space for 4,400 new graves annually (Beaumont, Citation2017). In response, verticality has been employed both above and below ground. In Petah Tikva, on the outskirts of Tel Aviv, a high-rise structure was erected in Yarkon Cemetery. At twenty-two stories high, it has space for 250,000 tombs, expanding the capacity of the cemetery by twenty-five years (Associated Press, Citation2014). In order to meet certain requirements to be buried in the earth, held by the local orthodox Jewish community, the building’s architecture contains a rather unique feature: pipes filled with dirt that run between each floor, so that each tomb is still connected to the ground. Rabbis in authority have determined that this arrangement does not compromise Jewish law. At the Givat Shaul cemetery in Jerusalem, a maze of deep catacombs is, at the time of writing, being constructed to house the rising population of the dead (Holmes & Kierszenbaum, Citation2019). The concrete-lined walls of the catacombs contain a grid of round niches, bored into the walls at two-metres deep, in total, creating about 22,000 new crypts at the site. This reportedly USD 50 million dollar projects is being undertaken by the Chevra Kadisha (or burial society) (Holmes & Kierszenbaum, Citation2019), and will eventually comprise a vast subterranean city for the dead.

The final, and perhaps most pervasive, example of the rise of verticality within global necro-architecture comes from East Asia, where high-rise columbaria have been erected in large numbers over the past decade, becoming rapidly accepted as a new norm of cemeteries. The lead author has conducted ethnographic fieldwork within these facilities in Tokyo and found that they demonstrate how vertical necro-architecture not only maximises cemetery yield, but also gives rise to new patterns of visitation and memorialisation (Uriu et al., Citation2018). In Japan, over 99% of the population is cremated and cremains are conventionally interred in a multi-generational stone tomb, usually located at a Buddhist temple or municipal cemetery. However, intense urbanisation post-WWII and diminished urban living space has created an extreme shortage of new gravesites and hiked up prices. Aoyama Cemetery, run by Tokyo Metropolitan Government, operates on a lottery system to cope with demand, and plots (ranging from 1.6 to 3.98 square metres) cost between ¥4.37 million and ¥10.8 million yen, in addition to the average retail cost of a tombstone, between ¥700,000 and ¥2 million yen (Brasor & Tsubuku Citation2018). As this system has reached breaking-point, new forms of necro-architecture have emerged across Japan, including so-called ‘locker-style columbaria’ composed of walls of metal lockers. To further increase capacity, these lockers are sometimes positioned on a sliding system, similar to library stacks, that can be opened or closed off to allow visitation. These facilities can store many tens of thousands of the dead and are often constructed next to train stations so that bereaved families can visit regularly as part of their commute.

As with mausoleums, the vertical stacking of remains gives rise to new forms of symbolic-spatial hierarchy, consumer desires, and memorialisation practices. In locker-style facilities, spaces at eye-height are the most sought after, because they facilitate a direct, tactile relationship between the living and the dead, including acts such as placing one’s hands on the outside of the tomb and offering flowers. Spaces above eye-height are the next most popular, but have the disadvantage of being relatively physically inaccessible, particularly for elderly visitors or those in wheelchairs. Finally, lockers close to the ground and to visitors’ feet are the least popular, as this position is deemed disrespectful to the dead. During peak seasons of grave-visitation, such as the festival of the dead (Obon), this vertical stacking also creates a serious congestion problem, with visitors trying to access different graves above and below one another. As such, salespeople at columbaria facilities in Tokyo report that they find these type of facilities difficult to market to customers. In order to counter these disadvantages and maximise the attractive space available for urban interments, a new form of mechanised necro-architecture, known as Automatic Conveyance Columbaria (‘ACC’) (自動搬送納骨堂 jidōhansōkotsudō) has recently been developed. There are now over one hundred facilities of this type across Japan (Uriu et al., Citation2018). ACC are built to address the social condition of living (horizontally) distant from the family grave, but their vertical reorganisation of spatial relations between the living and the dead is equally fascinating. ACC facilities house boxes of cremains in large warehouse-style storage walls that run the length and height of the facility. Each box is linked to a certain patron’s account and smart card, and when this card is tapped on to an electronic reader in the lobby, the box is automatically retrieved by a robotic arm and conveyed to one of several visitation booths within the facility.

At these booths, visitors can make prayers to the dead, light incense on the communal pyre, and often view images of the deceased on a digital screen set-up nearby. However, because this is essentially a ‘time-share grave’, and only temporarily the site of any particular set of remains, other ritual activities such as washing the gravestone or offering flowers are restricted. By mobilising the location of cremains within facilities, ACC technology solves the problems of disadvantageous vertical positioning of graves, but still, spatial hierarchies emerge within these sites. One ACC located in Ikebukuro, Tokyo, consists of several floors of viewing booths (each accessing one thousand sets of remains) located above a monumental statue of the Buddha. An interview with a priest working there revealed that his younger clientele generally prefer a position in the higher floors of the building, which they consider ‘closer to heaven’, whereas his more elderly clientele wish for their family’s remains to be interred as close as possible to the Buddha statue . In this manner, attention to the vertical axis reveals not only new power hierarchies but also symbolic relations that emerge within space . Future studies of verticality could perform a more intimate examination of interactions between the living and dead in relation to the configurations of interment.

Discussion: standing to rest

High-tech automation systems and densifying architecture are powerful solutions to the problems of caring for and storing the dead in the 21st century, but Kurweeton is not central Tokyo; it is a sheep farm. Residents in metropolitan Australian cities may face challenges in finding a proximate burial site, but land around Kurweeton cemetery is in abundance. What, then, drives a burial practice that ‘takes up less space’ in a location where space appears in abundance? What the examples above from Tokyo to Tel Aviv help us to understand in this case study is that the orientation of the body in space is not only a practical solution, but also reveals people’s aesthetic, financial, social, and spiritual concerns. Further, they show that verticality conveys a range of different meanings and power relations, and studies of interment must be understood across these diverse axes.

The vast majority (over 80%) of burials at Kurweeton are pre-purchased interments, that is, they are purchased by the person who intends to use it for their own burial, and these customers have a variety of motivations behind their choice, from environmental and financial concerns, to counter-cultural desires exemplified by the phrase ‘I did it my way’. Just as much as economic or environmental concerns, the upright burial system at Kurweeton appears driven by a desire for ‘simplicity’ or ‘minimalism’ in one’s death and disposition. At its core, the burial service consists of a man with a post-hole digger in a field with some sheep, and there is a certain appeal – at least for some – in this system. Leaning up against the paddock fence, Tony reflects on his original motivations for starting up the service, namely, personal experience of a funeral that was over-sold to a friend. A group of friends ‘examined each aspect of burial and queried its purpose and requirement’ and they found that ‘as we dismissed each feature as unnecessary, not only did the service become cheaper – it also became less demanding on resources’. Environmentalism, then, is only a byproduct of an innovation, one that has become a popular selling point of the service today. Ultimately, environmentalism is the direct result of a desire for simplicity. Tony describes how people can get ‘a bit bogged down’ in all of the ceremony and disposition options available, in the coffins and caskets and flowers and memorial videos; what he calls the ‘ephemeral bullshit’.Footnote6 These seem to get in the way of grief. As Tony says, ‘in some cases, you feel as though the more you pay the funeral director, the less you have to grieve yourself because you’re paying him to do the grieving for you, and it looks that way.’ This arrangement, he maintains, also generates guilt, because when people don’t buy into the traditions, they are told they are not grieving well. Certainly, in Australia and around the world, the funeral industry has been subject to intense critique for taking advantage of consumers at a vulnerable time in their lives, through a lack of cost transparency, and upselling or bundling services to increase profit margins (e.g., Gentry et al., Citation1994; Sanders, Citation2012). In contrast to this, what Upright Burial promises to offer is a kind of ego-denying but life-affirming burial. Tony relates that one of his (pre-paid) clients – whose speech is rich with Australian idiom – told him:

“I just want to fall off the earth. I just want to disappear.” And he said, “It looks as though your system, your services are as close as I can get and keep it legal. And I thought, “Well, you’re probably bloody right there, matey”

As much as scholars might wish to propose an essential human drive of necro-nominalism; to ‘be remembered’ and to commemorate the dead (see Lacquer, Citation2015, pp. 1–3), the monumentalism and place-making practices offered by the conventional cemetery are not universally desired. The longing for simplicity described by Tony and his clients is notable, and the word ‘simplicity’ is much sought after throughout the west to brand a funeral company. However, a desire for simplicity is also implicated in concerns that via secularisation and other social upheavals, we are stripping contemporary Western funerals of the ritual richness that facilitates a cathartic or ‘healthy’ experience of grief (e.g., Bailey & Walter, Citation2016). Concerns about the dis-placement of the dead from the city centre and from their role in people’s everyday lives as perpetuating a ‘death-denying culture’ do not necessarily resonate with those who wish to ‘fall off the earth’. This is one prominent narrative that arises from vertical burial at Kurweenton, but in future research, we aim to further explore customer motivations and potential conflicts that may arise between those who pre-purchase graves, the bereaved, and the wider community.

We live in a vertical age, and this dimension is increasingly becoming a valuable resource for the orientation of bodies, the storage of the dead, and the facilitation of memorialisation practices. As new forms of vertical necro-architecture emerging around the world teach us, the orientation of the dead within space is not neutral or universal. The conventions around supine burial in horizontally oriented facilities are indeed cultural creations that are too often imagined as ‘natural’ and thus necessary ways of death. However, cultural conventions are able to be challenged, particularly in a time when we are facing seriously troubling consequences for how we use space. We have seen how vertical burial has the potential to transform our relationship to the dead. Above-ground, monumental verticality can shape the skyline of a city and bring the dead back from the outskirts of town into the heart of an urban landscape. At the same time, the in-ground, individual verticality of the interred body at Kurweeton Cemetery in Victoria also transforms our relations with the dead – it offers innovation around disposition and orientation driven by environmentalism, minimalism, and simplicity. Verticality, in all the forms and cases discussed above, challenges us to be open to new ways of thinking about disposition practices and their value(s).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hannah Gould

Hannah Gould is a cultural anthropologist working on death and discarding, material culture, and religion. She is currently an ARC Research Fellow at The University of Melbourne, where she works with the DeathTech Research Team. Hannah’s work has been published in FOCAAL and Anthropological Quarterly and she is the recipient of the Japan Foundation Research Fellowship and the Dyason Fellowship. She is currently President of the Australian Death Studies Society.

Michael Arnold

Michael Arnold is Professor and Head of Discipline in the History and Philosophy of Science Programme at the University of Melbourne. His on-going research activities lie at the intersection of contemporary technologies and daily life, including studies of online memorials, body disposal and other technologies associated with death. Michael is a member of the DeathTech Research Team, has been Chief Investigator on many research projects, and has co-authored 4 research books and ~150 other research publications.

Tony Dupleix

Tony Dupleix is Managing Director of Upright Burials. He has been one of the drivers in establishing the business and oversees the daily operations at the site. Tony has been involved in agricultural interests his entire career, lives on and operates a farm at Camperdown. He has held numerous leadership roles in the community including local Branch President of the Victorian Farmers Federation and Captain of the Leslie Manor Rural Fire Brigade.

Tamara Kohn

Tamara Kohn is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Melbourne. She has conducted fieldwork in Scotland, Nepal, US, and Japan. Her research interests include humanistic anthropology, communities of practice, the body and senses, prison lives, death studies, and research methods and ethics. She is part of the DeathTech Research Team, studing death, commemoration, and new technologies of disposal and interment. Recent co-authored books from the team include Kohn et al (eds) 2019 Residues of Death (Routledge), and Arnold et al 2018 Death and Digital Media (Routledge).

Notes

1. A European Bronze Age archaeological culture.

2. George Lines purportedly became interested in burial practice during consulting trips to the Middle East, where he witnessed the lowering of deceased by rope into fissures in rock in order to protect the body from scavenger animals and to conserve scarce arable land for food production.

3. In Victoria, the minimum clearance between the top of the coffin and the ground is 750 mm. If the grave is sealed with stone, concrete or a similar material, this distance can decrease to up to 300 mm (see Regulation 24 of the Cemeteries and Crematoria Regulations 2015).

4. See literature on Australia (Perkins, Citation2003), Latin America (Klaufus, Citation2014), and East-Asia (Aveline-Dubach, Citation2012).

5. Conifers are also evergreen, and thus appear ‘undying’, and have a fresh scent that masks associations of decay in the cemetery.

6. The authors have made the decision to include expletives in this text as we believe they are necessary to communicate the fieldwork context of (rural) Australia, where such language is common and relatively inoffensive.

References

- Ariès, P. (1974). Western attitudes toward death from the middle ages to the present (P. M. Ranum, Trans.). The John Hopkins University Press.

- Associated Press. (2014, October 17). Pressed for space, israel building cemetery towers. Haaretz. https://www.haaretz.com/jewish/israel-building-cemetery-towers-1.5316506

- Aveline-Dubach, N. (Ed.). (2012). Invisible population: The place of the dead in East-Asian megacities. Lexington Books.

- Bailey, T., & Walter, T. (2016). Funerals against death. Mortality, 21(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2015.1071344

- Basmajian, C., & Coutts, C. (2010). Planning of the disposal of the dead. Journal of the American Planning Association, 76(3), 305–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944361003791913

- Beaumont, P. (2017, December 2). ‘We revived an ancient tradition’: Israel’s new subterranean city of the dead. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/dec/01/revived-ancient-tradition-catacombs-israel-subterranean-city-of-dead

- Bloch, M., & Parry, J. (Eds.). (1982). Death & the regeneration of life. Cambridge University Press.

- Brasor, P. & Tsubuku, M. (2018, August 10). Pricey family graves a fading tradition in aging Japan. The Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2018/08/10/national/family-graves-fading-tradition-japan-bereaved-opt-cheaper-convenient-alternatives

- Browne, R. (1982). Objects of special devotion: Fetishism in popular culture. Popular Press.

- Claasen, C. (2010). Feasting with Shellfish in the Southern Ohio Valley: Archaic Sacred Sites and Rituals. The University of Tennessee.

- Claasen, C. (2010). Feasting with shellfish in the Southern Ohio valley: Archaic sacred sites and rituals. The University of Tennessee.

- Clayden, A., Green, T., Hockey, J., & Powell, M. (2015). Natural Burial: Landscape, Practice and Experience. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315771694

- Cowling, C. (2010). The good funeral guide: Everything you need to know, everything you need to do. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Davies, D., & Rumble, H. (2012). Natural burial: Traditional - secular spiritualities and funeral innovation. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Elliot, R. (2018, July 13). Densifying death and high rise cemeteries. The Urban Developer. https://theurbandeveloper.com/articles/vertical-high-rise-cemeteries

- Forbes, S. L., Márquez-Grant, N., & Schotsmans, E. M. J. (Eds.). (2017). Taphonomy of human remains: Forensic analysis of the dead and the depositional environment. John Wiley & Sons.

- Fournier, E. (2018). The green burial guidebook: Everything you need to plan an affordable, environmentally friendly burial. New World Library.

- Gathered Here. (2019). Funeral prices in Australia report, 2019. www.gatheredhere.com.au

- Gentry, J., Kennedy, P., Paul, K., & Hill, R. (1994). The vulnerability of those grieving the death of a loved one: Implications for public policy. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 13(2), 128–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/074391569501400112

- Graham, S., & Hewitt, L. (2013). Getting off the ground: On the politics of urban verticality. Progress in Human Geography, 37(1), 72–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512443147

- Gregoricka, L. A., Betsinger, T. K., Scott, A. B., & Policy, M. (2014). Apotropaic practices and the undead: A biogeochemical assessment of deviant burials in post-medieval Poland. PLoS, 9(11), e113564. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113564

- Hallam, E., & Hockey, J. (2001). Death, memory, and material culture. Bloomsbury.

- Hariyono, W. P. (2015). Vertical Cemetery. Procedia Engineering, 118, 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2015.08.419

- Hewitt, L., & Graham, S. (2015). Vertical cities: Representations of urban verticality in 20th-century science fiction literature. Urban Studies, 52(5), 923–937. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014529345

- High, K. (2016). Piper in the woods: Men becoming trees. In C. N. Terranova & M. Tromble (Eds.), The Routledge companion to biology in art and architecture (pp. 504–514). Taylor & Francis.

- Holmes, O., & Kierszenbaum, Q. (2019, October 18). The future of burial: Inside Jerusalem’s hi-tech underground necropolis. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/oct/18/the-future-of-burial-inside-jerusalems-hi-tech-underground-necropolis

- Jalland, P. (2006). Changing ways of death in Twentieth-century Australia: War, medicine, and the funeral business. UNSW Press.

- Klaufus, C. (2014). Deathscapes in Latin America’s metropolises: Urban land use, funerary transformations, and daily inconveniences. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 96(96), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.18352/erlacs.9469

- Lacquer, T. W. (2015). The work of the dead: A cultural history of mortal remains. Princeton University Press.

- Lamster, M. (2011). Castles in the air. Scientific American, 305(3), 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0911-76

- Luckhurst, R. (2015). Zombies: A cultural history. Reaktion Books.

- Maddrell, A., & Sidaway, J. Eds. (2010). Bringing a Spatial lens to death, dying, mourning and remembrance. In A. Maddrell & J. Sidaway Eds., Deathscapes. New spaces for death, dying and bereavement (pp. 1–18). Ashgate.

- Maddrell, A. (2020). Deathscapes. In R. Kitchin & N. Thrift (Eds.), International encyclopedia of human geography (pp. 167–172). Elsevier.

- Mann, R., Bass, W., & Meadows, L. (1990). Time since death and decomposition of the human body: Variables and observations in case and experimental field studies. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 35(1), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1520/JFS12806J

- Mui, S. (2018). Dead body language: Deciphering corpse position in early Anglo-Saxon England [Unpublished PhD dissertation]. Durham University.

- Mui, S. (2019). Grave expectations: Burial posture in popular and museum representations. In H. Williams, B. Wills-Eve, & J. Osborne (Eds.), The public archaeology of death (pp. 73–84). Equinox Publishing.

- PBS. (2012). The Screw-In Coffin | INVENTORS | PBS digital studios. InventorSeries. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CBtRSOm7gpY

- Penney, J. (2016). Cemetery plantings and their symbolism (report). The Greater Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust. http://www.gmct.com.au/media/720754/gmct-information-sheet_plants_lr.pdf

- Perkins, J. (2003). A solution to the looming crisis of oversupply of dead bodies: The shortage and therefore high cost of burial space in the developed world. Australian Quarterly, 75(6), 34–37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20638221

- Sanders, G. (2012). Branding in the American funeral industry. Journal of Consumer Culture, 12(3), 263–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540512456924

- Schultz, J. J. (2007). Variables affecting the gross decomposition of buried bodies in Florida: Controlled graves using pig (Sus Scrofa) cadavers as a proxy for human bodies. Florida Scientist, 70(2), 157–165. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24321736

- Smith, J. (2011). Losing the plot: Archaeological investigations of prisoner burials at the old melbourne gaol and pentridge prison. Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, 10, 62-72. https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2011/losing-plot

- Sprague, R. (2005). Burial terminology: A guide for researchers. AltaMira Press.

- Timbs, J. (1877). English Eccentrics and Eccentricities. Chatto & Windus.

- Uriu, D., Odom, W., & Gould, H. (2018). Understanding automatic conveyor-belt Columbaria: Emerging sites of interactive memorialization in Japan. Proceedings of the 2018 Designing Interactive Systems Conference (747–752). Hong Kong, ACM.

- Van der Laan, S., & Moerman, L. (2017). It’s your funeral: An investigation of death care and the funeral industry in Australia. The University of Sydney Business School.