ABSTRACT

Covid-19 is the first pandemic to be broadcast and photographed as it happens worldwide. However, despite the plethora of images on countless aspects of the pandemic, few media images have covered its more sensitive issues, such as the collapse of the healthcare system, the process of dying alone, or the disruption to funeral rites and mourning. Consequently, the visual narratives of the pandemic are biased. They lack images that show its more dramatic aspects. This affects not only how the public perceives and reacts to Covid-19, but also the visual evidence that will remain for historical memory in the future. With one of the world’s highest case rates and most stringent states of emergency, Spain offers an interesting case study to analyse the pandemic’s photographic narratives and its missing images during lockdown. This paper focuses on the presence or absence of images dealing with illness, death, dying and grief, as well as their ways of representation. It delves into the framing of particular visual narratives through an analysis of the images that appeared in Spain’s leading newspapers, together with semi-structured interviews conducted with renowned photojournalists who worked on the front line to document Covid-19 during lockdown.

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has become the most significant historical event of recent decades because of its enormous social and economic impact, and the chaos it has presented to health care systems worldwide. Despite the shock triggered by the arrival of Covid-19, pandemics are neither a new nor an extraordinary human phenomenon, especially in countries that do not have the resources or support needed to combat disease. Epidemics and pandemics are a silent, latent reality that periodically appear, challenging the limits of the human capacity to face death when they do so. In the grip of a pandemic, humans create new narratives, new metaphors and even new language to understand and control it, not only from a purely technical or healthcare perspective, but in the social arena too. In this respect, the arrival of Covid-19 coincides with an extraordinary moment of globalisation in communications and the circulation of images. With the internet, social media, smartphone photography and connectivity, a significant portion of the population now live through the lens, constantly taking and sharing images (Lister, Citation2013). The images that have reached our screens from the outside world, particularly during lockdown, form the basis of our collective story and our future collective memory. With Covid-19, this has all occurred in a communication context that critics have described as an ‘infodemic’. Pardo proposes the new term ‘photodemic’ (Citation2020a) to capture the flood of images that mix together depictions of life during lockdown, concerts on balconies and instances of autofiction with other images of healthcare professionals, politicians, the media. The term also takes in memes and images manipulated from other pandemics or crises. The phenomenon of the photodemic marks a major difference with preceding pandemics, and is arguably distinct from what Lynteris (Citation2020) has identified as ‘epidemic photography’.

While the Covid-19 pandemic is one of the most photographed and documented events in history, there has been a marked absence or limited presence of images showing its starker aspects. From early on in the pandemic, questions have been asked about the absence of such images (Lewis, Citation2020; Pardo, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). In answer to such questions, this article seeks to focus on an analysis of the typology and presence of images depicting illness, dying, death and grief that have been produced and published in the Spanish media by professional photographers during lockdown. Our aim is to contribute to an analysis of the visualisation of death and dying during Covid-19, firstly, by looking at the role played by photojournalists in making the toll of the pandemic visible, and, secondly, through an examination of the narratives subsequently constructed about the pandemic. While there is still a debate about the appearance of images of death in the media owing to important differences between the degree and kind of representation of natural death as opposed to violent death, scholars tend to agree that images of death seldom appear in the media, particularly explicit images (Aaron, Citation2014; Hanusch, Citation2008, Citation2010, Citation2013; Walter et al., Citation1995).

Accordingly, our initial hypothesis was that there would be a low visual representation of the most serious aspects of the pandemic as a result of a certain degree of censorship over the images by editors of newspapers and/or by the photographers themselves. To this end, we have identified all images published in the three Spanish newspapers analysed during the strictest phase of lockdown and examined their potential influence on the visual narratives being generated about Covid-19. Notably, the paper focuses on the Spanish print media. Spain was one of the countries hardest hit by the first wave of the pandemic and underwent one of the most stringent lockdowns. The analysed period is of particular interest because of the major role played by images as a tool of communication and contact while the public remained isolated at home. The period under scrutiny, which begins with the declaration of a state of emergency (March 14th, 2020) and ends with the start of de-escalation (29th April 2020), spans the most significant period of the pandemic at an informational and societal level. It is also a period marked by the creation of the first visual narratives of the pandemic, in which the presence (or absence) and typology of images that revealed the severity of illness and dying contributed not only to showing (or not showing) what was actually happening, but also to creating public opinion and responses to the pandemic. For the object of analysis, we have selected the three most prominent general-interest newspapers in Spain: El País, El Mundo and La Vanguardia. In addition, the paper draws on the accounts of photojournalists of major renown and standing in Spain in order to include front-line testimony that can help to identify the agents and circumstances behind the visual narratives in question.

While other scholars have analysed the Spanish press during the pandemic, they have focused on front-page headlines (Monjas et al., Citation2020; Núñez-Gómez et al., Citation2020) or on a case study based on a limited number of specific images published by diverse media outlets (Freixa and Redondo-Arolas, Citation2021). By contrast, the present study delves into graphic representation more broadly by individually and jointly analysing the quantity, typology and focus of images published about the pandemic, and by comparing and contrasting the collected data with the comments of photojournalists who produced the images. This article, and the study it is based on, seeks to contribute to a better understanding of the presence and/or absence of images of death and dying as a result of illness – as distinct from the representation of violent death resulting from non-medical causes.

Theoretical framework

Presences and absences in the photographic representation of death, dying and grief

The photographic representation of death and dying has been present since the emergence of the medium. Changing attitudes to death and grief have been reflected in the changing nature and use of images of death and dying (Walter, Citation2015). So too have the uses and values given to the photographic image changed – for instance the particular intensity of the post-mortem image in the domestic sphere during the medium’s early decades (Morcate & Pardo, Citation2019; Morcate, Citation2012; Ruby, Citation1995).

While images of a loved one’s body in death and of the funerals of ordinary people have become increasingly rare in family archives, the visibility of images of state funerals and funerals of major public figures has become normalised in the media (Morcate & Pardo, Citation2019; Sumiala, Citation2013). Death and grief have become particularly visible on the internet (Pardo & Morcate, Citation2016), with particular emphasis on memorialisation and grief. This new prevalence and intensity has contributed to the re-normalisation of images death, grief and mourning. According to Lynteris (Citation2020), the use of photography has also been central to the way in which the public has experienced the most recent pandemics/epidemics of the twenty-first century. For Lynteris, the new genre of epidemic photography began to take root with the publication of the first photos of an epidemic at the end of the nineteenth century (the third global wave of bubonic plague). In light of medical photography that depicted symptoms, patients and methods of treatment, Lynteris (Citation2020) notes that photographers began to document and visualise not only the disease-afflicted but the wider social, cultural and material contexts of epidemic. Lynteris identifies various categories of images in the press that also depicted the measures being adopted for the control and containment of disease: fumigation, disinfection and vaccination. Lynteris additionally highlights the documentation of burial rites as purported sources of infection. For Lynteris, press images have played a key role in the very transformation of the idea of ‘pandemic’ from an ancient term found only in medical dictionaries to a word on everyone’s lips.

Moeller has also identified the use of certain visual metaphors, namely ‘science-fiction metaphors, animal metaphors, crime, detective or mystery metaphors, apocalyptic metaphors and military metaphors’ (Moeller, Citation1999, p. 64), which largely reappear in the visual narrative of Covid-19. To understand the variety of coverage and the visual ‘tones’ at play in the representation of illness and pandemics, Moeller stresses a number of variables like the novelty of the disease or virus, the violence of the epidemic in terms of its symptoms, and the scope of its geographical and social impact. She proposes six categories of images: hard-science images; images of animals to illustrate the origin of the illness; images of people in PPE (to convey the idea of contagion); images of victims or their medical conditions; images of death, of burials and of funerals that establish the deadly consequences of illness; and images of the disinfection of spaces to communicate strategies of epidemic control (Moeller, Citation1999, p. 66).

To gain a better understanding of images of illness, it is useful to note the humanist turn that took place at the end of the twentieth century in storytelling and in what have come to be known as illness narratives (Frank, Citation1995; Kleinman, Citation1988) written by authors who have put value on patients and their stories. This has had a clear impact on the agency of patients, a growing realisation of their rights and the need for greater awareness. The changing shape of literary narratives of illness (for an overview, see Hydén, Citation1997) has coincided with a transformation in the visual narratives of illness (Morcate & Pardo, Citation2019).

To contextualise press images, Chouliaraki (Citation2006) establishes three discourses of news (related to the regimes of pity that she identifies): adventure news, emergency news and ecstatic news. Each discourse involves differing degrees of emotional and moral involvement from the spectator. In his study on the representation of the SARS pandemic, Stijn Joye adds a fourth category; one that is particularly useful for the present study: the category of neglected news (Citation2010, p. 589). With this term, Joye points to the ideological and political implications of the absence of particular news items (and, by extension, the absence of particular images). Disasters exist for most people only if they are present in the media (Joye, Citation2010, p. 593). As Richardson points out (Richardson, Citation2007, p. 93), it is necessary to recognise that events are communicated as much by absence as by presence, so that what is lost or excluded also carries meaning and shapes narrative.

Chouliaraki (Citation2010) and Campbell (Citation2004) argue that it is necessary to understand the cultural context in which images of death are taken, distributed and published if the full connotation of such images, and their meanings, is to be grasped. Sontag (Citation2003/2007) and Moeller (Citation1999) have both observed that there is a predisposition to show culturally distanced death and suffering, whereas special care is given to victims who feel closer to home. Sontag (Citation2003/2007) has raised the question of whether images affect us more if they show ‘our people’, emphasising that images of our own dead are not like images of the dead of others, because they are even harder to bear and accept. Hanusch (Citation2008) puts greater stress on the predisposition of daily newspapers to offer information that is relevant to the public, and ‘relatable’.

The globalised scope and impact of the pandemic has made starkly visible countless, varied processes of loss, both primary and secondary, in every realm of human life, emotions and the economy (Zhai & Du, Citation2020), turning grief into the most everyday element of life amid the pandemic. It has given rise to ‘new geographies of death’ (Maddrell, Citation2020) in which many individuals have been abandoned to their fate in elder care facilities, hospitals or the streets; and in which many have died totally alone and/or have been buried with nobody in attendance save for funeral staff, often in mass graves, without respecting either the last wishes of the deceased or the grief of survivors. Healthcare personnel have experienced ‘exhaustion due to heavy workloads and protective gear, fear of becoming infected and infecting others, feeling powerless to handle patients’ conditions, accompanied by a sense of being fully responsible for patients’ well-being’ (Chochinov et al., Citation2020). As a result, millions of people have simultaneously undergone processes of loss, suffering and death, including processes of anticipatory or disenfranchised grief, which can be particularly intense (Wallace et al., Citation2020, p. 75) but have been represented little or not at all in the media. The Covid-19 pandemic has sprung up precisely within the overexposure of the social ground in the media and on the internet at the same time that loss is still being experienced largely in private.

Ethical debates on photojournalism in a time of pandemic

In the field of photojournalism, the coverage of war, famine, illness and death has been a constant, contributing to the creation and circulation of images that, on one hand, provide a critical approach to reality and, on the other hand, afford a graphic document and historical memory as legacies for the future. The stark nature of some images may make us question the ethical limits of photojournalism and photographic representation (Tagg, Citation1988) as well as the need to show certain images in order to, for example, raise awareness of issues related to human rights (Linfield, Citation2010). The explicit photographic representation of violence, suffering and death has raised a host of ethical and strategic debates among media professionals and theorists alike (Butler, Citation2007; Grønstad & Gustafsson, Citation2012; Morse, Citation2014; Sontag, Citation2003/2007; Zelizer, Citation2010). Such debates revolve around fundamental issues: the limits of representation; the effects of overexposure to violence and suffering and the effect of repeated exposure or overexposure to certain stories in the media; and the political implications that are especially important in a period as visual as the present day.

As a consequence, the professional seeks to strike a complex balance, using the camera to show what is fundamental in order to bear witness, generate critical opinion, and in some cases spur a change or reaction in the spectator, while trying not to contribute to compassion fatigue (Moeller, Citation1999). Accordingly, compassion fatigue controls and activates a mechanism by which media professionals very often choose subjects that not only are potentially more attractive for the reader, but also affect the type of visual narrative, which becomes increasingly more sensationalistic or extreme and thereby jeopardises the integrity of the profession – a danger raised by Pepe Baeza (Citation2001) twenty years ago.

According to Joan Fontcuberta, there are images that can transform life, change narratives and even create new currents of opinion (Fontcuberta, Citation2011, p. 4). Giving particular attention to images that have a dead body in the frame, Fontcuberta suggests that the image conveys an excess of truth and this excess sometimes becomes unbearable’ (Fontcuberta, Citation2011, p. 3). The ethical debate over which images are pertinent to publish is more complex, however, because it is necessary to take into account factors relating to the vulnerability of the individuals affected, the respect due to all people, the authorisations that are required to photograph and circulate images, the right to information versus the right to privacy, and so forth: in other words, the debate is about what constitutes the higher good.

The present pandemic sheds light on a paradigm shift that was already present, a shift now gaining intensity, producing a watershed in the way that events of global reach like the pandemic are documented and perceived.

Methodology

The research methodologies used for visual analysis (Van Leeuwen & Jewitt, Citation2008), visual data (Banks, Citation2010) and content analysis (Neuendorf, Citation2002) in relation to visual discourse are not as well-implemented or systematised as they are in other areas. As a result, the present article makes use of mixed methods (Campos Arenas, Citation2009). A review of the literature and documentary sources that point to the importance of the media as an essential source during the first lockdown in Spain enabled us to limit the research design to 14 March (the day on which the prime minister declared a state of emergency) to 28 April (when the government approved the de-escalation plan). Three daily newspapers were selected for analysis. All three are ranked as among the most highly read newspapers, both online and offline, in Spain (Newman et al., Citation2019; Redacción Barcelona, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). In addition, this selection provides not only geographic diversity — El País and El Mundo are based in Madrid, and La Vanguardia in Barcelona – but also ideological diversity. According to one study El Mundo is ‘more to the right than average’,Footnote1 while La Vanguardia is very close to the centre/average, and El País ‘tilting away from middle towards the centre left’ (SM Reputation Metrics, Citation2015).

For each newspaper, we selected the PDF version of the national edition that coincides with the print version sold at newsstands and is accessible through online subscription platforms and dedicated mobile device applications. Over the 46 days in question, a total of 137 issues were published. All photos accompanying news items in those 137 issues were reviewed. With the study’s key words (illness, death and grief, abbreviated hereafter as IDG) as our key analytic reference points, we reached agreement on the adequate research categories to obtain an appropriate classification of the data and prepare the tables and graphs.

The collected data show the representation of death, grief and illness in pandemic-related images in relation to the total number of images published in the newspapers over the period. Images were then sorted by those which related to news about Covid-19. Not included in the totals are any images from the weekly supplements, motoring pages or entertainment listings, as well as any pictures of columnists that accompany opinion articles. These images are excluded to avoid bias. The analysis in this article focuses on images representing Covid-19 illness, death and grief (IDG), where the term grief is extended to embrace images of mourning and the complementary category of other IDG images that include burials, cemeteries and morgues.

Lastly, a key element of the study has been to compare and contrast the collected data with the statements and experiences of photojournalists in order to gain a greater understanding of the findings and ascertain why there has been a lack of published images that represent dying, death and grief, among other issues. To achieve this, we conducted semi-structured interviews with six top-tier photojournalists who have had long international careers and worked on the pandemic in Spain during the period under analysis. The interviews were conducted until data saturation was reached. The six interviewed photojournalists are: Ana Jiménez (La Vanguardia); Alberto Di Lolli (El Mundo); Pedro Armestre (freelance photographer who collaborates with El País); Gervasio Sánchez (Spanish National Prize in Photography 2009); Ricardo García Vilanova (World Press Photo 2020); and Susan Vera (Pulitzer Prize 2020). They were chosen because they have taken some of the most iconic images of the pandemic or because they are among the photojournalists who have been most active in reporting critically on working conditions in the period. Precisely because of their public visibility and their own comments on the images, their names have not been anonymised.

Results

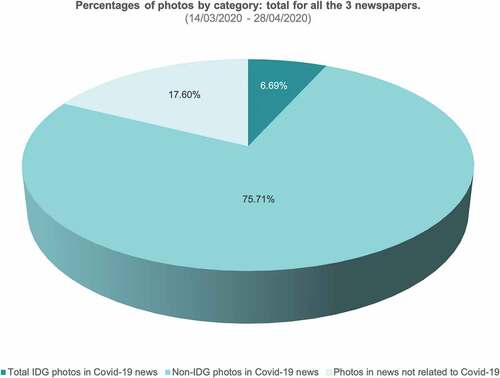

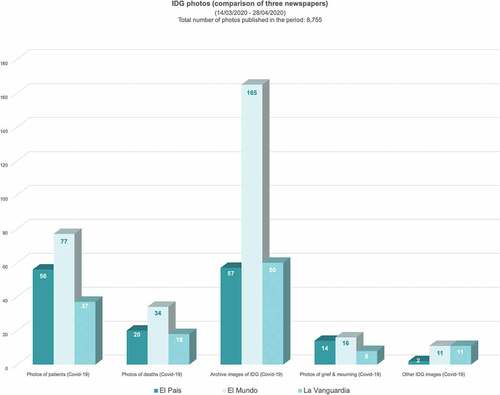

The total number of images is 8,755 (see ), which breaks down as follows: El País (2,371), El Mundo (2,476) and La Vanguardia (3,908). Of these, 1,541 did not accompany news that bears any relation to Covid-19. The remaining images (7,214) were published with pandemic-related news, but only 586 belong to the IDG category.

Table 1. Photos by Subject: Comparison of the three newspapers (14/03/2020 - 28/04/2020).

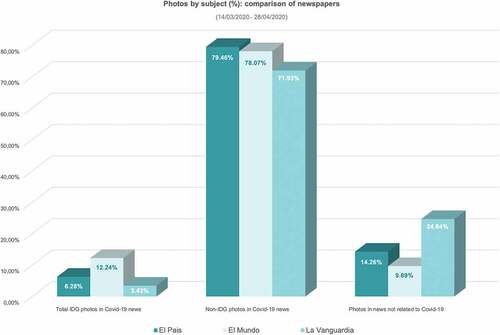

As shows, only 6.69% of the photos published by the three newspapers were IDG photos related to Covid-19, whereas more than three quarters of the photos illustrated news linked to Covid-19 but did not show ill people, death or grief (and 17.60% were images of subjects other than the pandemic).

The total number of images that specifically represent the pandemic is even more limited. Of the images related to ill people, death and grief (see and ), only 170 show patients. Of these, most are asymptomatic or recently discharged, while the majority of patients shown in the ICU are partially hidden and no image of the face of a dying person has been identified. Seventy-two images were designated as related to death and 38 to grief. In addition, 282 IDG images illustrate news related to human interest stories showing portraits or family images.

Table 2. IDG photos: Comparison of the three newspapers (14/03/2020 - 28/04/2020).

As shows, El Mundo has a major spike in archive images of IDG: 100 appeared on the front page on 24 April 2020 in commemoration of people who had died of Covid-19. If the 100 images are counted as a single front-page image, the figure for El Mundo is 65 images in the IDG category, which is much closer to the figure for the other two newspapers.

Most of the images of death are represented in a veiled or indirect manner. The majority show caskets (47), while a few show covered corpses (15) and only one (twice published) contains an entire corpse visible. Of the images showing covered dead bodies – that includes body bags, sheets, and other coverings − 12 contain only one body, whereas the three that contain more than one body come from other countries (two from New York and one from Bergamo). Also included are six images of vehicles, because the photo captions indicate that they are transporting dead bodies. In addition, most of the images of caskets show only one (32) and typically only a portion of a casket. A large number of caskets is visible in only 15 images, of which only eight were photographs taken in Spain: three at the Palacio de Hielo ice rink in Madrid (one of these images republished) and five at a funeral home in Collserola (Barcelona).

With respect to the presence of IDG images or the importance that the selected newspapers attached to them during the period under analysis, provides a detailed look at the percentage of photographs that each paper published on IDG related to Covid-19. Notably, El Mundo has the most published images in the category. In relation to the percentage of non-IDG photographs related to news on the pandemic, all three newspapers have more than 70% of their images in this category.

Discussion

These findings suggest a marked absence of photographs in the press that show the most severe impacts of Covid-19. What is more typically represented is tabular or graphical information that represent the cold, hard figures of positive test numbers, ICU occupancy and the death toll, often accompanied by remote, metaphorical or indirect images that bear little or no connection with the data presented or the gravity of the situation. Bearing in mind that 82.4% of the images published by the three newspapers during the period were related in some way to the pandemic, the presence of explicit IDG images is low.

These findings confirm the rarity of explicit images of death and the end of life in pandemic or illness-related news, which is also in line with the findings of other studies on violent death in the news media (Hanusch, Citation2008, Citation2013; Zelizer, Citation2010). In respect to the scarcity of such images in print news coverage of Covid-19 in Spain, however, the difficulties of access that photojournalists encountered was key, an issue we discuss in more detail below.

Among the 71 identified images that represent death, only a single deceased person is entirely visible. That image, which appeared on the front page of El Mundo on 15 April 2020, was taken by Alberto Di Lolli. In it, a male victim of Covid-19 lies lifeless in his home, while a doctor and a nurse certify his death. The face of the dead man was pixelated to preserve anonymity, but even so the photo sparked controversy. According to Di Lolli (interview) the week the photograph appeared, Spain had the world’s highest death rate per capita. El Mundo’s editors were clear that the image should be published – the only question was whether to put it on the front page or not. The image accompanied the report on a 24-hour ride-along with an emergency medical services team (SAMU, in Spanish), and the photographer had followed protocol by requesting permission to enter the victim’s home and take photographs. Di Lolli showed the resulting image to the doctor of the medical emergency team and asked whether she felt that it was right to publish it, and her reaction surprised him: ‘What’s wrong with the photo? This is every day in my job’. Her reaction challenges us to question whether the issue is the photograph of the body, or the reality that lies behind it.Footnote2 Unlike this explicit image of the specific human toll of the pandemic, only a few images (15) show anonymous, covered, corpses (mostly in body bags). In the vast majority of these, the body of the deceased is hidden within a casket, a cremation urn or inside a hearse. As for images of grief, there are even fewer. Only 38 images clearly fall into the grief and mourning category and 24 into other IDG images (). Among these ‘other’ images, one shows a granddaughter with a photograph of her grandparents, dead of Covid-19, two show people at impromptu shrines in the street, while a fourth image is a photo collage in honour of a dead loved one.

Spain recorded its highest number of deaths from Covid-19 on 2 April 2020, when 950 people died.Footnote3 On the same day, the newspapers published three photographs that explicitly represented death (El Mundo published an image of a partially shown victim in Guayaquil, Ecuador, while La Vanguardia featured a front-page image, republished inside, of overflow caskets in the parking garage under a funeral home in Collserola, in Barcelona) and only ten photographs showed patients (El País: 3; El Mundo: 6; La Vanguardia: 1). On the following day, the newspapers published seven images of patients (El País: 2; El Mundo: 4; La Vanguardia: 1) and five of death (El País: 2; El Mundo: 2; La Vanguardia: 1). Over the two days in question, therefore, a total of two out of eight photographs of death depicted other countries (Ecuador and Brazil), five out of eight featured a funeral home in Collserola and only one out of 17 patient photographs was taken in ICUs. Similarly, photographs showing caskets and mass graves were taken in other countries (the US and Brazil). It is clear then that the few IDG images that did get published do not show the scale of the disaster, at least not in Spain. These findings coincide with the low visual representation of ‘natural’ (as opposed to violent) death and also support the contention that it is the representation of death far from home, more specifically the ‘death of others’, that, while still a delicate subject, is nonetheless more easily tolerated than death at home (Moeller, Citation1999; Sontag, Citation2003/2007; Walter et al., Citation1995).

With respect to the debate over the need to publish stark images of the pandemic, Ana Jiménez’s opinion is that ‘I think you have to see everything, otherwise what sense does our work have, everything must be seen, and it should be possible to handle it’. In the view of Di Lolli, there has been a lack of images of illness, death and grief that would enable the public to gain awareness and understand the situation: ‘When we’re not seeing people die in their homes, how they die, the grief that it causes […] when we’re not seeing any of this, we’re not made aware nor can we take joint responsibility’. Pedro Armestre agrees with this concern, adding that there is a need ‘to be made aware and, above all, to grasp the scale of the problem’. Gervasio Sánchez was similarly blunt in his critique:

Not showing the severity of Covid-19 has meant that many people […] do not believe that it really was an epidemic, a deadly pandemic, or they have become denialists. […] I’d never show the face of an old man or woman, or of a person dying or dead of Covid, especially knowing that their family hadn’t seen them. But there are many ways to show […] the real impact of the pandemic and the real impact in places where they are working to save lives.

Susana Vera notes that it took her five weeks to secure permission to begin working in crematories, ICUs and so forth and it was anger that drove her. ‘How can it be’, she asked, ‘that we’re not telling the public what’s really happening?’ Having observed first-hand the collapse of healthcare services, she concluded:

It was dreadful that people weren’t seeing what was happening […] you can have a raft of figures, you can have heaps of data, but your brain doesn’t react unless you give it a wallop. […] You have to get hit in the stomach, in the heart and in the head. It doesn’t work if it’s only in the head.

Whereas Moeller (Citation1999) noted that the visual characteristics of the Ebola outbreak featured images of scientists in specialised protective clothing, of corpses in body bags, and of citizens wearing face masks, we have found in the present analysis of Covid-19 that, while that visual repertoire is present, the overwhelming majority of images accompanying newspaper stories on Covid-19 in Spain (75.71% of the total) focuses on the depiction of everyday life amid the pandemic: empty streets, people shopping, pictures of politicians and healthcare professionals, images of people clapping or paying tribute to victims, the efforts of the security forces, and even depictions of everyday heroism that show the public trying to get on with their lives, jobs and studies. Some of these images are related to what Chouliaraki (Citation2010) identifies as a national mythology that supports a specific grand narrative of collective identity, one that is particularly striking at a time when Spain is going through a complex process of political change around soveriegnty.

Based on the preceding analysis, the major gap in the visual narratives of the illness is that of the viewpoint of – and on – covid sufferers, especially those patients who were the main characters in much of the news (the dead and patients in the ICU). As a result, the usual categories of narratives of this sort do not apply and there is a closer connection to the category of ‘neglected news’ (Joye, Citation2010) of the Covid-19 pandemic in Spain. Death and dying, which were ubiquitous at the time, constitute the foremost absence in the visual accounts we identified. We are therefore left with a visual narrative of the pandemic in which, paradoxically, the main characters in the news are those most absent from it. When delving into the causes of the lack of some important images, the interviews with photojournalists indicate that the low representation of death and dying was not caused by direct censorship. Consequently, our initial hypothesis has only partially been validated, since none of them reported censorship issues with the daily newspapers themselves or agencies for which they work or with which they collaborate to publish images. In addition, all of them mentioned the collaboration of physicians, nurses or Spain’s Military Emergencies Unit (UME, in its Spanish initials) to facilitate the photographers’ work but they decided not to take or publish images without official permission in order to protect their sources.

The photojournalists we interviewed all expressed concern over current working conditions and raised the issue of the right to information. They reported difficulties in gaining access to places like hospitals, funeral homes and elder care facilities, especially in the early weeks of the pandemic.Footnote4 All six photojournalists we interviewed highlighted their concerns about restricted access, especially to places important for documenting the pandemic, such as hospitals, morgues and elder care facilities during the confinement in Spain. Those limitations on access made the documentation of certain situations extremely complicated, restricting or conditioning their narrative potential. Di Lolli suggests that among some of the missing images were the patients dying alone in hospital; the emotional toll on the healthcare professionals who stayed by the beds of the dying to comfort them; and the experience of soldiers who stood vigil over the dead in the Palacio de Hielo ice rink (which had been hastily converted into a morgue). The storytelling of the pandemic’s toll would have changed significantly if there had been a photographic record of such moments, rather than the caskets stacked up as in a warehouse, for instance. An image stolen at an ‘exceptional’ moment may become the only published image and, given the absence of other images to set beside it, the story that it tells cannot be representative of the complexity of experience or event. It nonetheless becomes the only visual narrative of the moment – the foundation on which to build, for instance, the story of the disposal of the pandemic dead, as opposed to the story of their departure under a watchful and caring human eye. As Vilanova puts it, ‘there is a part that will, let’s say, be passed onto the next generations and offer as a point of reference, imagine it, only people applauding, out of something that has been the world’s most serious crisis since the Second World War … ’.

The photojournalists we interviewed nevertheless did admit that it was complicated to obtain permits to enter such places and take photographs, and that the people in charge of facilities justified their exclusion on the grounds of security, infection control and/or the protection of the dignity of the victims (although some officials gave no adequate justification whatsoever). In any case, they made it impossible for photojournalists to carry out their usual work. Ana Jiménez first obtained permission to enter a hospital weeks after the outbreak of the pandemic, when the collapse had already abated: ‘We missed that entire crisis, we’re talking about a whole month, the chaos, chaos until they began to get organised’. This could explain the appearance, instead, of some IDG images taken abroad, since they could not be taken in Spain these stand in as representatives of an otherwise unrepresentable realm. The photojournalists we interviewed were also critical of the control of information by institutions, the censorship imposed or the self-censorship enacted; the way the right to information was questioned. While Pedro Armestre believed that ‘it was not so much a question of censorship as that they were overwhelmed’, Ana Jiménez decried how ‘the power over what is seen, the public’s right to information, is filtered now through communications departments, and it’s extremely serious’. Ricardo Vilanova agreed, arguing that the effect of such control over information has produced a rupture with respect to ‘all the freedoms that existed or that we had as a society, because in the first wave we were kept from reporting’. Gervasio Sánchez also determinedly described what happened as censorship.

All but one of the photojournalists we interviewed identified the press offices of institutions and companies as one of the greatest obstacles to obtaining permits to enter spaces and do their work. All of them also noted the consequent absence of images of some of the pandemic’s most significant aspects. That absence traces a direct line between the limitations on access by photojournalists and the visual narrative that has been created, especially in the early weeks of lockdown when neither the chaos in the healthcare system nor its victims appeared. The result, therefore, is a visual narrative of the pandemic that is partial and incomplete. Indeed, as the data and interviews point out, some realms of experience have been specifically eliminated, including the moments of human and institutional chaos – arguably the very IDG images necessary for grasping the pandemic’s impact on the country.

Conclusion

The most serious aspects of illness, dying, death and grief have been poorly represented during the pandemic in Spain as a whole, but especially during the lockdown that accompanied the first wave. That lack of representation has had a major impact on the visual narrative of the period. Beyond the ethical debate over the limits of representation and the type of images of suffering that should be shown, it is clear that the representation of dying, death and grief has not been even remotely proportional to the pandemic toll that characterised those weeks. As a result, the breadth and complexity of suffering has not been communicated visually in relation to its actual weight in society at the time. This lack stems from a combination of factors, but particularly the difficulties encountered by professionals seeking to gain access to hospitals, morgues and the like during the most chaotic, dramatic moments of the pandemic, as well as the control exerted by institutional authorities over the representation of the ill, dying and dead in their care. The safety and dignity of people affected by Covid-19 was used as an argument to exclude journalists’ access to both sites and information. The photojournalists we interviewed decry a growing infantilisation of society by institutions that censor and/or constrain their work when they seek to report critically on the system’s shortcomings and to show the pandemic to its fullest extent, including its most brutal aspects.

It proves highly complicated to pay the utmost respect to the sensitivities and dignity of people affected by Covid-19, while at the same time respecting the right to information and the freedom of expression. Indeed, the challenge this presents raises questions about where the freedom of expression ends and the violation of people’s rights begins. The visual narrative of a pandemic like the current one will certainly not be complete if it shies away from the more serious aspects of life and death under Covid-19 in favour of images that only gesture towards those impacts: hopeful portraits of recovered patients, city vistas showing empty streets, or the thankful on their balconies, clapping for healthcare personnel. The invisibility of the seriously ill patients who were intubated at the ICU, of the collapsing of the healthcare system, of morgues overwhelmed, and the deaths at home of the thousands who could not even be admitted to hospital, of the dead who were buried without witnesses, and of grieving survivors isolated at home – these absences count, and should have a visual accounting. Returning to the words of Alberto Di Lolli: the pandemic is a page of history ‘that we are going to turn without having read it’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Montse Morcate

Montse Morcate’s research focuses on the visual representation of death, illness and grief. She is co-editor of the book La imagen desvelada: representaciones fotográficas de la enfermedad, la muerte y el duelo [The image unveiled: Photographic representations of illness, death and grief] (2019). Morcate is a member of three research projects: ‘Making pain visible: Visual edia storytelling’ funded by FEDER/Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation; ‘Connected bodies: Art and cartographies of identity in a transmedia society’ funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness; and ‘Ethics of images of illness, death and grief in the time of Covid-19’ funded by Fundació Grífols. Morcate has completed post-doctoral research stays at Columbia University and the Morbid Anatomy Museum (New York), CSIC (Madrid) and MACBA (Barcelona). She has also been developing and exhibiting her own art works, pursuing projects in line with her field of research.

Rebeca Pardo

Rebeca Pardo’s research focuses on visual narratives of illness, death and grief. She has led several research projects and is currently the principal investigator for ‘Making pain visible’ (RTI2018-098181-A-I00) funded by FEDER/Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. Together with Morcate, Pardo obtained a 2020 grant in bioethics from the Fundació Grífols for the project ‘Ethics of images of illness, death and grief in the time of Covid-19’. Pardo has completed research stays at the University of Brighton, Harvard University, Spanish National Research Council and CED-MACBA. Her art works have been exhibited in Spain, UK and Italy. In 2012, she received the Ariel Prize for best young essay bloggers. Pardo has published various papers and book chapters and taken part in numerous conferences and lectures. She is co-editor of the book La imagen desvelada: representaciones fotográficas de la enfermedad, la muerte y el duelo (2019).

Notes

1. Due to space limitations, any Spanish quotations or interviews appear only in English translation.

2. Despite the sparse representation of death on the front or inside pages of the newspapers, an article appeared on 22 April in the critical media observatory Media.cat in which contributors debated over the controversy to show or not show the dead on front pages, in relation to the image of the parking garage filled with caskets under the Collserola funeral home. The article by Estefanía Bedmar is available at https://www.media.cat/2020/04/22/els-altres-i-els-nostres-en-el-fotoperiodisme-la-polemica-densenyar-o-no-morts-a-les-portades/consulted on 26 June 2021).

3. The figure does not convey the actual death toll, because it tallies only cases with a confirmed diagnosis. Given the scarcity of tests at the time, it was not possible to confirm diagnoses in many cases, especially in elder care facilities. Data available at https://www.elmundo.es/ciencia-y-salud/salud/2020/04/08/5e8d9ce1fc6c8309438b45b9.html (consulted on 26 June 2021).

4. Stijn Joye (2015, pp. 690–691) indicates that journalists have faced difficulties of access to the scene of events of this sort when reporting on disasters, while this issue has not been found to be addressed in scholarship on the visibility of death in photojournalism.

References

- Aaron, M. (Ed.). (2014). Envisaging death: Visual culture and dying. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Baeza, P. (2001). Por una función crítica de la fotografía de prensa. Gustavo Gili.

- Banks, M. (2010). Los datos visuales en Investigación Cualitativa. Ediciones Morata.

- Butler, J. (2007). Torture and the ethics of photography. Environment and Planning D: Society & Space, 25(6), 951–966. https://doi.org/10.1068/d2506jb

- Campbell, D. (2004). Horrific blindness: Images of death in contemporary media. Journal for Cultural Research, 8(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/1479758042000196971

- Campos Arenas, A. (2009). Métodos mixtos de investigación: integración de la investigación cuantitativa y la investigación cualitativa. Cooperativa Editorial Magisterio.

- Chochinov, H. M., Bolton, J., & Sareen, J. (2020). Death, dying, and dignity in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 23(10), 1294–1295. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0406

- Chouliaraki, L. (2006). The spectatorship of suffering. Sage.

- Chouliaraki, L. (2010). The mediation of death and the imagination of national community. In A. Roosvall & I. Salovaara-Moring (Eds.), Communicating the nation: National topographies of global media landscapes (pp. 59–78). Nordicom.

- Fontcuberta, J. (2011). Indiferencias fotográficas y ética de la imagen periodística. Editorial GG.

- Frank, A. W. (1995). The wounded storyteller: Body, illness, and ethics. University of Chicago Press.

- Freixa, P., & Redondo-Arolas, M. (2021, November 9-10). COVID-19, medios de comunicación y fotografía. ¿una crisis sin víctimas? [Paper presentation]. XII International Conference on Online Journalism, Bilbao, Spain.

- Grønstad, A., & Gustafsson, H. (2012). Ethics and images of pain. Routledge.

- Hanusch, F. (2008). Graphic death in the news media: Present or absent? Mortality, 13(4), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576270802383840

- Hanusch, F. (2010). Representing death in the news: Journalism, media and mortality. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hanusch, F. (2013). Sensationalizing death? Graphic disaster images in the tabloid and broadsheet press. European Journal of Communication, 28(5), 497–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323113491349

- Hydén, L.-C. (1997). Illness and narrative. Sociology of Health & Illness, 19(1), 48–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.1997.tb00015.x

- Joye, S. (2010). News discourses on distant suffering: A critical discourse analysis of the 2003 SARS outbreak. Discourse & Society, 21(5), 586–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926510373988

- Kleinman, A. (1988). The illness narratives: Suffering, healing, and the human condition. Basic Books.

- Lewis, S. (2020, May 1). Where are the photos of people dying of COVID? The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/01/opinion/coronavirus-photography.html

- Linfield, S. (2010). The cruel radiance: Photography and political violence. University of Chicago Press.

- Lister, M. (2013). The photographic image in digital culture (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Lynteris, C. (2020, April 16). How photography has shaped our experience of pandemics. APOLLO.The International Art Magazine.

- Maddrell, A. (2020). Bereavement, grief, and consolation: Emotional-affective geographies of loss during COVID-19. Dialogues in Human Geography, 10(2), 107–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620934947

- Moeller, S. (1999). Compassion fatigue: How the media sell disease, famine, war and death. Routledge.

- Monjas, M., Rodríguez, A., & Gil-Torres, A. (2020). La covid-19 en las portadas de diarios de difusión nacional en España. Revista de Comunicación Y Salud, 10(2), 265–286. https://doi.org/10.35669/rcys.2020.10(2).265-286

- Morcate, M. (2012). Duelo y fotografía post-mortem: Contradicciones de una práctica vigente en el siglo XXI. Revista Sans Soleil: Estudios de la Imagen, (4), 168–181.

- Morcate, M., & Pardo, R. (2019). La Imagen desvelada: Prácticas fotográficas en la enfermedad, la muerte y el duelo. Sans Soleil Ediciones.

- Morse, T. (2014). Covering the dead. Journalism Studies, 15(1), 98–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2013.783295

- Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook. Sage Publications.

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., & Nielsen, R. K. (2019). Reuters institute digital news report 2019. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2019. 156. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/digital-news-report-2019#:~:text=Download%20Digital%20News%20Report%202019.

- Núñez-Gómez, P., Abuín-Vences, N., Sierra-Sánchez, J., & Mañas-Viniegra, L. (2020). El Enfoque de la prensa española durante la crisis del Covid-19. Un análisis del framing a través de las portadas de los principales diarios de tirada nacional. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 78(78), 41–63. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2020-1468

- Pardo, R. (2020a, June 30). Fotodemia: pandemia de imágenes que provoca una ceguera selectiva. En la Retaguardia: Imagen, Identidad y Memoria. https://rebecapardo.wordpress.com/2020/06/20/fotodemia-pandemia-de-imagenes-que-provoca-una-ceguera-selectiva/

- Pardo, R. (2020b, April 27). Las imágenes de la cuarentena: ¿es correcto invisibilizar el drama? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/las-imagenes-de-la-cuarentena-es-correcto-invisibilizar-el-drama-137210

- Pardo, R., & Morcate, M. (2016). Illness, death and grief: The daily experience of viewing and sharing digital Images. In E. Gómez-Cruz & A. Lehmuskallio (Eds.), Digital photography and everyday life (pp. 70–85). Routledge.

- Redacción Barcelona. (2019a, November 11). ‘La Vanguardia’ es el diario digital más leído de España en el móvil. La Vanguardia. https://www.lavanguardia.com/vida/20191121/471771257336/la-vanguardia-comscore-audiencia-web-movil-elpaiscom-elmundoes-abces.html

- Redacción Barcelona. (2019b, December 19). Comscore: ‘La Vanguardia’ cierra 2019 como líder de la prensa digital en España. La Vanguardia. https://www.lavanguardia.com/vida/20191219/472343899595/comscore-la-vanguardia-lider-noviembre-diarios.html

- Richardson, J. E. (2007). Analysing newspapers: An approach from critical discourse analysis. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ruby, J. (1995). Secure the shadow: Death and photography in America. MIT Press.

- SM Reputation Metrics. (2015). El perfil ideológico de los lectores de prensa. Análisis encuestas #7deldebatedecisivo. https://smreputationmetrics.wordpress.com/2015/12/09/el-perfil-ideologico-de-los-lectores-de-prensa-analisis-encuestas-7deldebatedecisivo/

- Sontag, S. (2007). Ante el dolor de los demás. A. Major Ed. 4th Alfaguara. (Original work published 2003).

- Sumiala, J. (2013). Media and the ritual: Death, community and everyday life. Routledge.

- Tagg, J. (1988). The burden of representation: Essays on photographies and histories. MacMillan Education LTD.

- Van Leeuwen, T., & Jewitt, C. (2008). Handbook of visual analysis. Sage Publications.

- Wallace, C., Wladkowski, S., Gibson, A., & White, P. (2020). Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: Considerations for palliative care providers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(1), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012

- Walter, T. (2015). Online memorial culture as a chapter in the history of mourning. Review of Hypermedia & New Media, 21(1–2). https://doi.org/10.1080/13614568.2014.983555

- Walter, T., Littlewood, J., & Pickering, M. Death in the news: The public invigilation of private emotion. (1995). Sociology, 29(4), 579–596. . https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038595029004002

- Zelizer, B. (2010). About to die: How news images move the public. Oxford University Press.

- Zhai, Y., & Du, X. (2020). Loss and grief amidst COVID-19: A path to adaptation and resilience. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 80–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.053