ABSTRACT

In light of the increasing scholarly attention to the concept of decentralized personalization, this paper argues that the territoriality (the level of government to which an MP belongs) of an MP would also lead to variations in that MP’s incentive to personalize their campaigns. Using data from the PARTIREP Comparative MP survey, this paper tests the role of the territoriality of an MP in their incentive to personalize their campaigns across nine multi-level countries in Western Europe. Although the level of personalization of campaigns does differ according to territoriality, the underlying explanatory variables do not behave uniformly across territoriality. This paper thus draws attention to the rarely explored role of territory, and the complications it may bring to the explanation of the personalization of politics.

Introduction: the personalization of politics in multi-level systems

The personalization of politics has drawn substantial scholarly attention. While there are many competing faces of this larger personalization process, the personalization of politics (referred to simply as ‘personalization’ below) remains highly disputed at best in the literature.

There is a concern in the conceptualization of personalization. The most commonly used definition is phrased as a dichotomous relation between the importance of a candidate vis-à-vis that of the party (Carey and Shugart, Citation1995: 418; Poguntke and Webb, Citation2005: 5; Holmberg and Oscarsson, Citation2011: 47; Ohr, Citation2011: 22), but many scholars have failed to identify significant growth of personalized campaigns in European democracies (Carey and Shugart, Citation1995: 420–424; Karvonen, Citation2010: 39). In this way, scholars usually ended up finding mixed results in cross-country studies (Karvonen, Citation2010; Vliegenthart et al., Citation2011: 103). The problem emerges from the conceptualization of the ‘party’ as a single analytical construct. What exactly is being compared to the relative importance of the candidate? Will they mean the same thing across regions and across constituencies?

The conceptualization of the party side of personalization becomes even more problematic as we approach Western European countries, of which many are multi-level democracies. In these systems, parties were also found to decentralize alongside the political system, where regional branches adopt different party programmes than that of the national headquarters (Carty, Citation2004: 13). The party system may also vary across regions too. When national parties and independent regional parties become ideologically similar, there is also a chance that candidates would embark on a personal campaign to distinguish themselves from fellow ideologues in an election (Roller and Van Houten, Citation2003: 18; Lynch, Citation2009: 632). Given the drastic differences in the contexts between the national and the regional levels of elections, one should not expect the personalization of politics to play out identically in national and regional politics.

This paper aims to bring attention to these rather unexplored variations of personalization dynamics in multi-level democracies. This paper aims to build on the conceptual framework of ‘decentralized personalization’ (Van Aelst et al., Citation2012; Balmas et al., Citation2014) and dive deeper into unravelling the territoriality of personalization of politics. By comparing the degree of personalization and relevant independent variables, this paper hopes to demonstrate how personalization varies according to territoriality.

Territoriality and campaign personalization

So far the research hinges on the assumption that there is indeed a difference in the dynamics of campaign personalization in terms of territoriality. Territoriality refers to the ‘organization of political space and the spatial extent of political authority’ (Henders, Citation2010: 6). Thus, this paper assumes that the way personalization plays out would vary according to the spatial organization of politics. In other words, both the results and the relevant causes of the personalization of politics should be quite different according to what level of politics we are discussing. Is there such a difference?

Scholars have found evidence pertaining to the differences of national campaigns at the national and constituency level (Whiteley and Seyd, Citation2003; Fisher and Denver, Citation2008; Cross and Young, Citation2015). Although these possibilities for personalization still pertain to the national-level elections, given such major differences within just the national level of politics in multi-level systems, there is a possibility that regional campaigning may see constituency-level campaigns becoming more or less important, resulting in differences in the likelihood for personalized campaigning due to territoriality (Swenden and Maddens, Citation2009: 3).

However, there are two issues with the evidence. First, the majority of the evidence comes from single-member plurality (SMP) countries, thus their experience might be less relevant to the multi-level Western European countries, which almost entirely use proportional representation (PR) systems instead. Second, this kind of campaign differences does not necessarily imply personalization (Zittel and Gschwend, Citation2008; Karlsen and Skogerbø, Citation2015). In fact, these ‘localized’ campaigns might be merely national campaigns adapting to constituency-specific concerns that have nothing to do with personalization (Roller and Van Houten, Citation2003: 19; Massetti, Citation2009: 514). After all, if a candidate personalized her campaign so much that it contradicted the national strategy, the national party leadership would have replaced the ‘disloyal’ candidate (Cross and Young, Citation2015: 308). In personalized campaigns, we should be able to find greater importance of the individual candidate over the party organizations (Balmas et al., Citation2014: 47). In this sense, ‘localized’ campaigns are different from ‘individualized’ campaigns, which are highly personal campaigns that emphasize the candidate more than the party.

All the evidence points to the issue laid out in the beginning of this paper: that the ‘party’ in the definition of personalization is never a single analytical object. It refers to the relative importance of quite different party organizations at different territorial levels of analysis. These observations relate back to Carty (Citation2004)’s discussion of the franchise party ideal-type: party policy may be determined at different levels, leading to the possibility of convergence as well as contradictions across different levels of party organizations (13). Further complicating to this development is the fact that different regions enjoy varying degree of authority (Hooghe et al., Citation2016), resulting also in very strong and very weak regional party organizations.

Nonetheless, this possibility of personalization diffusing to the periphery of the central party leadership has definitely caught increasing scholarly attention. For instance, scholars recommend paying more attention to the phenomenon of ‘decentralized personalization’, which refers to the power dispersion among the members of an elite group (Van Aelst et al., Citation2012; Balmas et al., Citation2014: 37). However, the current definition has unfortunately denied any role of rank-and-file members of the party at all (André, Gallagher and Sandri, Citation2014: 183). After all, subnational-level politicians are usually not the elites at the national centre of politics who are more likely subject to decentralized personalization.Footnote1 At times, these two levels of politicians clash with each other due to a conflict of interest across territoriality (Hopkin, Citation2009: 187; Van Houten, Citation2009: 143–144). Therefore, much remains to be seen concerning how territoriality variations would lead to the variations in the incentives to cultivate a personal vote in campaigns. Thus, this paper aims to expand upon this theory of decentralized personalization by adding a new possible avenue of personalization of politics: the role of territoriality. The research goal of this paper can be summarized by the following research questions:

RQ1. To what extent could varying territoriality explain the varying degree of personalization of campaigns?

RQ2. Why would the varying degree of territoriality lead to varying degrees of personalization of campaigns?

Sources of variations of personalization in varying territoriality

There are generally two groups of factors that would lead to variations in personalization under varying territoriality (Rahat and Sheafer, Citation2007). This paper hypothesizes that two factors are related to the role of territoriality.

Institutional factors

From the growing literature on decentralized personalization, we could deduce that regional or local campaigns have quite different degrees of personalization (Klingemann and Wessels, Citation2001; Zittel and Gschwend, Citation2008; Cross and Young, Citation2015). However, regions are never homogeneous. Some federal or confederal regions, for instance, Germany’s Länder or Swiss Cantons would be intuitively more powerful than others, such as Portugal’s Azores and Madeira Islands. In relatively more powerful regions, they enjoy as much authority as an independent country, so there is a chance that regional party organizations operate as if they are a national party organization themselves in their procedure for selecting candidate and applying party discipline (Carty, Citation2004: 18–19; Deschouwer, Citation2006: 293–294). Therefore, while we may not find any difference between national MPs and MPs from strong regions in their degree of personalization, we might be able to find differences when we compare with MPs from weaker regions instead. After all, if a region is weaker in authority, one would intuitively expect that the national party organization retains strict party discipline that prevents a candidate distancing themselves from the national party or the regional branch of that party (Van Houten, Citation2009: 146), thus the above discussion over central and constituency-level campaign would not apply. Thus:

H1. MPs at the national level and from stronger regions are more likely to personalize their campaign.

Besides, the size of the constituency may also matter. Campus (Citation2002), in her discussion of personal campaigns in Italy, found that many personal campaigns involve leadership tours and canvassing (178–179). A similar pattern has also been found in the UK since 1974 (Fisher and Denver, Citation2008: 815). In this way, the size of the constituency matters because it would intuitively take more time and resources for a candidate to campaign personally in a distinct, larger constituency (Campus, Citation2002: 178–179):

H2. Candidates are more likely to embark on a personal campaign when the size of their constituency is smaller.

Media factors

The media system is closely associated with personalization. By media factor we refer to how the media enables the MP to personalize. One such possibility is that the degree of media access MPs has determines the incentives to personalize (Ohr, Citation2011: 22; Holtz-Bacha et al., Citation2014: 163).

In varying territoriality, the access to local media might have led to varying levels of personalization of politics. When the local media system is focused on regional issues, regional candidates have greater access to these channels, so it would be easier for them to personalize there (Driessens et al., Citation2010: 318–319; Cross and Young, Citation2015: 313). On the other hand, when the local media gravitate towards national issues, one should expect that regional MPs get very little to no attention at all, thus it could be harder for them to run a personalized campaign. For instance, regional MPs are believed to have less authority than their national counterparts on nationally salient issues, such as Crime and Foreign Affairs, so the nationally oriented local media would not give them a chance to personalize if they campaign on these issues (Midtbø et al., Citation2014: 193).

Since regional MPs only need to appeal to a region, they do not necessarily benefit from national media access. As the exposure to national media may not mean much for regional candidates, it is possible that the impact of media exposure for regional candidates are all clustered in subnational-level media when that level of media is oriented towards reporting subnational issues (Driessens et al., Citation2010; Cross and Young, Citation2015). Therefore, it is expected that:

H3. Regional Candidates are more likely to embark on a personal campaign when they have better access to the local media.

Methods

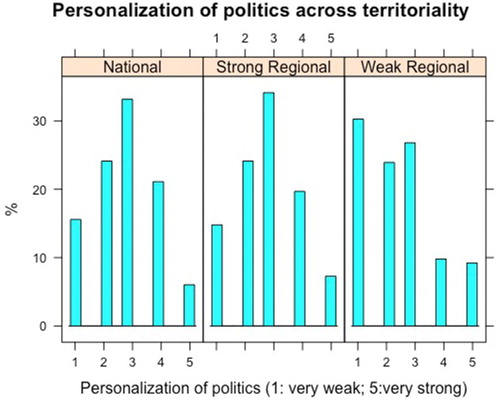

The study is separated into two parts. First, in order to answer RQ1 and test H1, MPs are organized into three groups: National, Strong Regional and Weak Regional. Then their group means of personalization of campaigns are compared by conducting an analysis of variance (ANOVA). Regional government strength is determined by the mean value of the score each region has under the Regional Authority Index (RAI) (Hooghe et al., Citation2016). Regional MPs from regions that score above the mean are grouped into the ‘Strong Regional’ group, while those that share a score equal to or below the mean are classified as the ‘Weak Regional’ group.

Next, in order to explain the results found in the ANOVA, a hierarchical regression for the three groups of MPs will be conducted. Given that more regions are represented in this study despite their rather small population (e.g. the case of Switzerland here), the linear regression models are weighted by the population size of the regions. Since there is no population data available for the year 2012, the closest available data from 2014 is used to produce the weights (Eurostat, Citation2017b). The coefficient and significant levels from the three groups will be used to figure out and compare the causal story (stories) for these groups of MPs, thus answering RQ2.

The data come from the PARTIREP Comparative MP Survey data set (Deschouwer et al., Citation2014). Data are collected by various means such as online surveys, hardcopy surveys, telephone surveys, and interviews between Spring 2009 and Winter 2012 (9–10). MPs from 15 countries are represented in the original data set, but as this paper aims to study personalization only in multi-level systems, this limits our observations to 9 countries represented in the data set. In Austria, Belgium, and Switzerland, all regional parliaments are represented (except the canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden in Switzerland). In other cases, geographical balance is taken into account when it comes to case selection for regional parliaments, such as from east to west in Germany (i.e. Brandenburg, Lower Saxony, Rhineland-Palatinate, Thuringia) and from north to south in Italy (i.e. Calabria, Campania, Lazio, Lombardy, Tuscany, and Aosta Valley). In Spain, case selection is based on the strength of the various autonomous communities and regionalist traditions (i.e. Andalusia, Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Valencia). However, there are slight asymmetries in the selection of French, Portuguese, and UK regional parliaments. In the French case, only assemblies of Poitou-Charentes and Aquitaine are represented. In Portugal and the UK, some regions do not have a regional assembly, such as inland Portugal and England, thus regional assemblies could be over-represented (6–7). In any case, the case selection of regional parliaments reflects a high variety of regional parliament strength according to Hooghe et al. (Citation2016)’s RAI.

The dependent variable is the degree of personalization of campaigns. This is well captured by the PARTIREP data set’s question 21(1), where MPs are asked:

To retain their seat in Parliament, Members of Parliament often face hard choices. How would you choose to allocate your limited resources? Would you choose to spend more effort and money on achieving the goal on the left-hand side (on a personal campaign), would you choose to spend more effort and money on the goal on the right-hand side (on a party campaign), or would the allocation of resources to both goals be about equal?

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for personalization of campaigns.

Specific independent variables are devised to respond to each of the hypotheses laid out above. A variable on the constituency area is required to answer H2. Land area data are taken from Eurostat under the NUTS 3 region classification (Eurostat, Citation2017a). Unfortunately, the data set does not provide information regarding the constituency in which each MP was running. Therefore, we can merely take a proxy of the area of the region the regional MPs are representing. For national MPs running in PR systems, the size of the entire country is coded for the area they represent. Given the limitation of data, the area for national MPs running in SMP systems is coded to the minimum regional area of their country in the NUTS3 data set to simulate the smaller size of SMP constituencies. A logarithm of the area size is taken to centre the data. Land area data from 2012 are used to align with the data in the PARTIREP data set, which are collected from 2009 to 2012.

To answer H3, a variable for local media access is taken from the results of question 15(9) in the PARTIREP survey. The question asks the MP how often they would feature in the local media. A higher value of this variable indicates more presence in the local media.

Control variables are divided into several groups. Demographic variables include the seniority of MP and the gender of MP. The ‘Rookie MP’ dummy is coded ‘1’ when the MP was serving her first term in office when she took the survey. After all, these rookie MPs may be too timid to distant themselves from the party as they must ‘go through a period of apprenticeship’ under the wings of their party (André, Gallagher and Sandri, Citation2014: 183). The ‘female’ dummy is coded ‘1’ when the MP is reported a female. A ‘leadership’ variable is coded ‘1’ when the MP took up any kind of leadership roles, be it in the party or in the parliament she serves. This control variable ensures that an MP’s incentive for personalization has nothing to do with their increased responsibility within and outside the party.

The next group concerns the parties. The ‘MP Party in Government’ dummy measures whether the MP’s party is governing in any level of government. An MP’s incentive structure to personalization should not be affected by whether the MP’s party is ruling, and/or the relative strength of the party reflected by this measure. A self-reported measure of party discipline is included as a control in order to exemplify that the results are not generated by extreme degrees of party (in)discipline. A higher value of this variable denotes the perceived party discipline as too strict.

Results

The ANOVA on the personalization of campaign yielded a significant variation among the groups specified by our strategy, F(2,1820) = 13.424, ***p < .001. A post hoc Tukey’s test revealed that only the differences which involve MPs from weaker regions are significant (***p < .001 for both group differences). shows how exactly these groups differ. The levels of personalization for MPs from weaker regions concentrate on the lower-half of the spectrum, while the results for other groups of MP rest in the centre instead. While there could be differences between national and regional MPs in the degree of personalization, more importantly, one must take into account the strength of the regional parliaments the regional MPs belong to. Those who come from a strong region have more or less the same degree of personalization as their national-level counterparts, while the same cannot be said for those who come from weaker regions. Thus, H1 is confirmed.

presents the results of the regression analysis. Second, the constituency area is inconsistent in predicting the personalization of campaigns. Only in stronger regions does it demonstrate an effect in the expected direction, b = –.21, **p < .01. For national-level MPs and MPs from weaker regions, personalization increases quite dramatically as area increases, b = .69, **p < .01. As this speaks against H2, H2 is thus rejected.

Table 2. Explaining personalization of campaigns by territoriality of MPs.

Third, the local media access variable works only in the predicted direction significantly in weaker regions, B = .13, *p = .04. However, it does not manifest in stronger regions. Thus, it is only safe to say that H3 cannot be accepted.

Last but not least, some control variables turned significant in the analysis. The most prevalent is the dummy for MP’s party in government. However, they are highly inconsistent in their effect size and significance level across territoriality.

Discussion

There are three points that can be made from this short piece of research. First, territoriality matters when we explain personalization. While the framers of the notion ‘decentralized personalization’ made it clear that the power would not flow to the hands of ‘rank-and-file politicians’ (Balmas et al., Citation2014: 37), the initial ANOVA has proven that, depending on which territoriality is being discussed, regional rank-and-file politicians can personalize as much as national-level politicians do. The difference rests upon the strength of the regional government. If the regional government is strong enough, it is quite likely that it behave as if they are an independent state, and MPs there are equally likely to personalize as much as their national counterparts would do. This also responds to some of the previous literature that found little effect as they include a dummy indicating the MP is from a regional parliament (André, Freire and Papp, Citation2014). As long as the heterogeneity among regional governments has been taken into account, results on personalization vary quite drastically. Therefore, to answer RQ1, yes, territoriality matters in the task of explaining personalization.

What is even more interesting is the fact that more variances can be explained by the independent variables for MPs from weaker regions than the other two groups, as the regression model for that group has a higher adjusted R2 figure of .10 which is close to a double of that of national-level MPs and MPs from stronger regions, respectively. This could imply that the existing theorization of causes of personalization could only effectively explain personalization when it is weakly manifested among politicians, while we are still lacking stronger explanations for personalization when it is relatively stronger, in our case, at the national level, and in stronger regions.

These observations suggest that even when one could not find any differences in terms of personalization at all between different countries, if one look deeply into how these variables function across territoriality, new explanations on the personalization of campaigns could be drawn. Insignificant results found in the larger, cross-country literature on personalization (Karvonen, Citation2010; Vliegenthart et al., Citation2011: 103) does not imply that personalization did not occur in these countries, nor the variables they theorized had no impact. It could be simply due to the fact that personalization is so sensitive to cross-level or cross-regional differences that the effect the theorized explanatory variables have are cancelled out in the eventual cross-country analysis.

Second, the territorial variables failed to predict differences of personalization consistently within the subnational level and across levels of government. For instance, we failed to produce empirical results to support H2 on the land area of the constituency. This is likely due to two reasons: on the side of the candidate, it is likely that the varying levels of regional authority affect the visibility of a candidate, leading to different incentive structures for running a personalized campaign. After all, in stronger regions, the regional parliament has greater authority to legislate, thus making the legislative activity of a candidate (or manifesto for newcomers) more salient or visible to the electorate. In this light, the marginal effect for every extra mile of canvassing may not mean much for these candidates. Therefore, as discussed in the literature, personalizing in a larger territory in these regions would mean an increased cost of campaigning and canvassing with little marginal benefit to the candidate, thus resulting in a negative effect for personalization (Campus, Citation2002; Fisher and Denver, Citation2008).

However, the same cannot be said for weaker regions. A different mechanism might be at work in these regions: Here, the relative salience or visible of candidates will be lower to the electorate, thus turning area into a new resource for running personalized campaigns. After all, these regional parliaments have little authority to legislate on so people may simply turn a blind eye on that level of election. In such a context, candidates need to embark on a campaign that could motivate an electorate that may care less about the election. Here, the land area might become a new resource for campaigning: as area increases, the candidate could amass more votes by focusing on regional or local issues. The larger the constituency area, the more regional issues they could focus on. At times this would result in a personalized campaign that emphasizes on local advocacy performance or local issues that are not covered in the party programme (Klingemann and Wessels, Citation2001). Because of the low-salience environment, every extra mile canvassed in such a personalized campaign could have a significant marginal impact on the candidate’s electoral prospect, thus the previous calculus of campaign costs may not apply to this level of elections. There has been some discussion on the effect salience of local issues have in personalized campaigns, but they have been mostly focused on national-level campaigns (Cross and Young, Citation2015; Zittel, Citation2015). Therefore, future research should also look into the salience of these issues in regional campaigns.

On the party side, the contradictory effect direction can perhaps be explained by the level of party financial support for candidates. For stronger regions, given the authority that level of parliament possesses, it is likely that parties are more generous with the level of manpower and financial support to the candidates running there. This again neutralizes the incentive of going for an extra mile of personalized campaigns. However, this is unlikely in the case for those running in weaker regions. There are all the fewer reasons for parties to supply candidates running in weaker regions with the same level of financial resources for those running in stronger regions, if that level of election is less salient and the parliament there could not do much. In this context, candidates may have to fund their campaigns themselves. Again, area becomes a resource in these contexts. The larger the area, the more sources of personal funding a candidate may secure. Thus in this way, the candidate may find more incentives to run on a personalized campaign for financial reasons in larger territories. So far there has been some work on the relationship between campaign fundraising and the intention to cultivate a personal vote (Samuels, Citation2002; Zittel, Citation2015), but again, most of these literature focus on national legislative elections. Therefore, future research should test this relationship if it would manifest at various strengths as a function of regional authority.

Also rejected is the hypothesis of access to local media. This finding contrasts with the literature on local media effects (Driessens et al., Citation2010; Cross and Young, Citation2015).

Initially, it is suspected that local media access is to be mediated by area. However, results of an interaction effect between the two yielded insignificant coefficients in the negative direction for all kinds of MPs (results not reported here). From the significant effect found for MPs from weaker regions, it is possible that the media effect is indeed clustered at the local level for these MPs, but not for those from stronger regions. In stronger regions, this effect is at best unstable (note the standard error implies the coefficient would cross 0 as we move up one standard deviation in the sample). What precisely contributes to this instability is unclear, but it could be related to the question of media orientation. In weaker regions, the local media might be geared towards also reporting regional issues, thus providing the candidates access (Driessens et al., Citation2010; Cross and Young, Citation2015). In stronger regions, the local media might be geared towards reporting strictly national and local issues so regional issues or elections might be left out (Zittel, Citation2015). That level of coverage might be found in a higher-level regional media. The precise reasons leading to varying media orientations might be more related to media system variations and thus is out of the scope of the paper. Anyhow, it is crystal clear that as territoriality varies, candidates also experience varying levels of access to media for them to personalize there.

Again, these issues arise from our current conceptualization of ‘the personalization of politics’. The current working definition compares the relative importance of a candidate to their party, but there is little reflection on what that ‘party’ actually constitutes. In ‘personalization’, the party is sometimes treated as a ‘fall guy’ to be compared to the candidate without elaboration. In this study of multi-level systems, as per Carty (Citation2004), it is very clear that the ‘party’ that personalization compares with varies from territoriality to territoriality. The party could be franchised, could be factionalized, or even fractured. This results in also the varying importance of the party from one level of politics to another, leading to a confusing explanation to the personalization of politics in multi-level systems. Thus, in order to understand the puzzling inconsistent coefficients presented above, perhaps the study of personalization of politics has to respond to the variations brought forward by the reality of multi-level politics in Western Europe.

This leads to the third point: there is no unified causal path leading to personalization as we look into varying territoriality. The independent variables behave in a drastically different way as we move from one level of government to another. While we have discussed much of the factors leading to varying results among stronger and weaker regional governments, it is crucial that we also consider the same results for national and regional governments. Consider the case of local media access, national-level MPs, and MPs from weaker regions both see their incentive of personalization increase as access to the local media increase. While the coefficient of national-level MPs is insignificant, the same effect direction raises the potential problem of equifinality (Tarrow, Citation2010: 252–253; Rohlfing, Citation2012: 43). The second part of the analysis shows clearly that there is a possibility for similar causal directions occurring for an unexpected pair of groups, thus complicating our efforts to respond to RQ2.

Nevertheless, this paper has drawn attention to various new avenues for decentralized personalization by looking into territoriality. Still, many questions remain unanswered in the second part of the analysis. Therefore, some next steps are in order to improve our understanding of the personalization of politics in multi-level systems.

First, we need more disaggregated data to come at a more precise picture of the causal story. In this case, the area variable has to be measured via a proxy since existing data does not allow for precise measurement of constituency size. In future studies, area should be disaggregated so that we could arrive at a better measurement for constituency land area for national-level MPs.

In addition, some of the conjectures discussed above regarding the area and local media access variables must be evaluated by new data. The salience question can be addressed by including an extra question asking MPs how much they feel their electorate care about the election in upcoming surveys. For evaluating the campaign funding conjecture, campaign funding data of course is preferred. However, if that is not possible for privacy concerns, researchers could approach by asking how much the candidate values the work done by the national party organization (Karlsen and Skogerbø, Citation2015: 432) and the regional party organization to fully capture the franchise party dynamics suggested by Carty (Citation2004). But most importantly, there should be a clear definition of what ‘party’ organization that is being studied, and how important are these different organizations to candidates running at different levels of government.

Drawing from the third point made above, further studies should try out two strategies in order to tackle the issue of equifinality. First, more qualitative-oriented approaches can be used to seek out the missing ‘Z’, that is, the causal mechanism that links the dependent variable and the independent variable (Levy, Citation2008: 5; Rohlfing, Citation2012: 34). But more simply, since equifinality is caused by variations in the background variables such as the timing of occurrence of the dependent variable, the behaviour of actors (in our case, MPs), the time lag between actions by various actors and so on (Rohlfing, Citation2012: 43), one can reduce equifinality by looking into more homogeneous cases. For instance, subnational studies in multi-level systems, at the expense of lower generalizability, could effectively reduce equifinaity without having to switch to a smaller-N research design. This has been done in explaining the variation in the degree of decentralization in Switzerland (Mueller, Citation2015), and perhaps the same can be done for personalization of politics in multi-level systems.

As the literature on the personalization of politics moves away from the study of top elites in the party, it is crucial that we also move away from conceptualizing the ‘party’ side of the personalization of politics as a singular analytical construct. In a multi-level context, we must acknowledge the fact that territory matters. This results in variations of the ‘party’ differs across levels of government, and thus the incentive structure for a MP to personalize also changes accordingly. This puts territory onto the upcoming research agenda on the personalization of politics.

Acknowledgements

The data used in this publication were collected by the PARTIREP MP Survey research team. Neither the contributors to the data collection nor the sponsors of the project bear any responsibility for the analyses conducted or the interpretation of the results published here. The author thanks Rudy Andeweg for his helpful comments and feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This is not the case in a few countries where MPs are allowed to take parliamentary positions across territoriality, for example, in France. French MPs tend to occupy as much positions as possible across territoriality, a phenomenon known as the cumul des mandats (accumulation of mandates, Brouard et al., Citation2013). Whereas the country in question does not allow the occupation of seats across territoriality, the argument above still holds.

References

- André, A., Freire, A. and Papp, Z. (2014), Electoral rules and legislators’ personal vote-seeking, in K. Deschouwer and S. Depauw (eds), Representing the People: A Survey Among Members of Statewide and Sub-State Parliaments, pp.87–109. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- André, A., Gallagher, M. and Sandri, G. (2014), Legislators’ constituency orientation, in K. Deschouwer and S. Depauw (eds), Representing the People: A Survey Among Members of Statewide and Sub-State Parliaments, pp.166–188. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Balmas, M., et al. (2014), Two routes to personalized politics: centralized and decentralized personalization, Party Politics, Vol.20, No.1, pp.37–51. doi:10.1177/1354068811436037.

- Brouard, S., et al. (2013), Why do French MPs focus more on constituency work than on parliamentary work?, The Journal of Legislative Studies, Vol.19, No.2, pp.141–159. doi:10.1080/13572334.2013.787194.

- Campus, D. (2002), Leaders, dreams and journeys: Italy’s new political communication, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, Vol.7, No.2, pp.171–191. doi:10.1080/13545710210137938.

- Carey, J. M. and Shugart, M. S. (1995), Incentives to cultivate a personal vote: a rank ordering of electoral formulas, Electoral Studies, Vol.14, No.4, pp.417–439. doi: 10.1016/0261-3794(94)00035-2

- Carty, R. K. (2004), Parties as Franchise systems: the stratarchical organizational imperative, Party Politics, Vol.10, No.1, pp.5–24. doi:10.1177/1354068804039118.

- Cross, W. and Young, L. (2015), Personalization of campaigns in an SMP system: the Canadian case, Electoral Studies, Vol.39, pp.306–315. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2014.04.007.

- Deschouwer, K. (2006), Political parties as multi-level organizations, in R. S. Katz and W. J. Crotty (eds), Handbook of Party Politics, pp.291–300. London: Sage Publications.

- Deschouwer, K., Depauw, S. and André, A. (2014), Representing the people in parliaments, in K. Deschouwer and S. Depauw (eds), Representing the People: A Survey among Members of Statewide and Sub-State Parliaments, pp.1–18. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Driessens, O., et al. (2010), Personalization according to politicians: a practice theoretical analysis of mediatization, Communications, Vol.35, No.3, pp.309–326. doi:10.1515/COMM.2010.017.

- Eurostat (2017a). Area by NUTS 3 region[demo_r_d3area] [Datafile].Available at http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset = demo_r_d3area&lang = en (accessed 2 June 2017).

- Eurostat (2017b). Population on 1 January by age group, sex and NUTS 3 region[demo_r_pjangrp3] [Datafile]. Available at http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset = demo_r_pjangrp3&lang = en (accessed 15 June 2017).

- Fisher, J. and Denver, D. (2008), From foot-slogging to call centres and direct mail: a framework for analysing the development of district-level campaigning, European Journal of Political Research, Vol.47, No.6, pp.794–826. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00785.x.

- Henders, S. J. (2010), Territoriality, Asymmetry, and Autonomy : Catalonia, Corsica, Hong Kong, and Tibet. New York, NY and Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillian.

- Holmberg, S. and Oscarsson, H. (2011), Party leader effects on the vote, in K. Aarts, A. Blais and H. Schmitt (eds), Political Leaders and Democratic Elections, pp.35–51. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Holtz-Bacha, C., Langer, A. I. and Merkle, S. (2014), The personalization of politics in comparative perspective: campaign coverage in Germany and the United Kingdom, European Journal of Communication, Vol.29, No.2, pp.153–170. doi:10.1177/0267323113516727.

- Hooghe, L., et al. (2016), Measuring Regional Authority. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hopkin, J. (2009), Party matters: devolution and party politics in Britain and Spain, Party Politics, Vol.15, No.2, pp.179–198. doi:10.1177/1354068808099980.

- Karlsen, R. and Skogerbø, E. (2015), Candidate campaigning in parliamentary systems: individualized vs. localized campaigning, Party Politics, Vol.21, No.3, 1354068813487103. doi:10.1177/1354068813487103.

- Karvonen, L. (2010), The Personalization of Politics: A Study of Parliamentary Democracies. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Klingemann, H.-D. and Wessels, B. (2001). The political consequences of Germany’s mixed-member system: personalization at the grass roots?, in M. S. Shugart and M. P. Wattenberg (eds), Mixed-Member Electoral Systems: The Best of Both Worlds?, pp.279–296. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Levy, J. S. (2008), Case studies: types, designs, and logics of inference, Conflict Management and Peace Science, Vol.25, No.1994, pp.1–18. doi:10.1080/07388940701860318.

- Lynch, P. (2009), From social democracy back to no ideology?—The Scottish National Party and ideological change in a multi-level electoral setting, Regional & Federal Studies, Vol.19, No.4–5, pp.619–637. doi:10.1080/13597560903310402.

- Massetti, E. (2009), Explaining regionalist party positioning in a multi-dimensional ideological space: a framework for analysis, Regional & Federal Studies, Vol.19, No.4–5, pp.501–531. doi:10.1080/13597560903310246.

- Midtbø, T., et al. (2014). Do the media set the agenda of parliament or is it the other way around? Agenda interactions between MPs and mass Media, in K. Deschouwer and S. Depauw (eds), Representing the People: A Survey among Members of Statewide and Sub-State Parliaments, pp.188–209. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mueller, S. (2015), Theorizing Decentralization: Comparative Evidence from Sub-National Switzerland. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Ohr, D. (2011), Changing patterns in political communication, in K. Aarts, A. Blais and H. Schmitt (eds), Political Leaders and Democratic Elections, pp.11–34. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Poguntke, T. and Webb, P. (2005), The Presidentialization of Politics: A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rahat, G. and Sheafer, T. (2007), The personalization(s) of politics: Israel, 1949–2003, Political Communication, Vol.24, No.1, pp.65–80. doi:10.1080/10584600601128739.

- Rohlfing, I. (2012), Case, case study, and causation: core concepts and fundamentals, in I. Rohlfing (ed), Case Studies and Causal Inference, pp.23–60. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Roller, E. and Van Houten, P. (2003), A national party in a regional party system: the PSC-PSOE in Catalonia, Regional and Federal Studies, Vol.13, No.3, pp.1–22. doi:10.1080/13597560308559432.

- Samuels, D. J. (2002), Pork barreling is not credit claiming or advertising: campaign finance and the sources of the personal vote in Brazil, The Journal of Politics, Vol.64, No.3, pp.845–863. doi:10.1111/0022-3816.00149.

- Swenden, W. and Maddens, B. (2009), Territorial party politics in Western Europe: a framework for analysis, in W. Swenden and B. Maddens (eds), Territorial Party Politics in Western Europe, pp.1–30. Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tarrow, S. (2010), The strategy of paired comparison: toward a theory of practice, Comparative Political Studies, Vol.43, No.2, pp.230–259. doi:10.1177/0010414009350044.

- Van Aelst, P., Sheafer, T. and Stanyer, J. (2012). The personalization of mediated political communication: a review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings, Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism, Vol.13, No.2, pp.203–220. doi:10.1177/1464884911427802.

- Van Houten, P. (2009), Multi-level relations in political parties: a delegation approach, Party Politics, Vol.15, No.2, pp.137–156. doi:10.1177/1354068808099978.

- Vliegenthart, R., Boomgaarden, H. G. and Boumans, J. W. (2011), Changes in political news coverage: personalization, conflict and negativity in British and Dutch newspapers, in K. Brants and K. Voltmer (eds), Political Communication in Postmodern Democracy: Challenging the Primacy of Politics, pp.92–110. Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillian.

- Whiteley, P. and Seyd, P. (2003), How to win a landslide by really trying: the effects of local campaigning on voting in the 1997 British general election, Electoral Studies, Vol.22, No.2, pp.301–324. doi:10.1016/S0261-3794(02)00017-3.

- Zittel, T. (2015), Constituency candidates in comparative perspective – how personalized are constituency campaigns, why, and does it matter?, Electoral Studies, Vol.39, pp.286–294. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2014.04.005.

- Zittel, T. and Gschwend, T. (2008), Individualised constituency campaigns in mixed-member electoral systems: candidates in the 2005 German elections, West European Politics, Vol.31, No.5, pp.978–1003. doi:10.1080/01402380802234656.