ABSTRACT

Our study investigates political candidates’ networks in the multilevel political setting of Belgium. Using Twitter data collected during the four months preceding the May 2019 regional, federal and European elections, we examine the extent to which network homophily – defined as the tendency to interact with similar others – occurs among political candidates along parliament, language and party lines. Relying on a unique dataset of 20 061 retweets between 935 candidates, we find that network interactions are most likely to occur among co-partisans and candidates speaking the same language. Candidates campaigning for the same parliament also tend to retweet among each other, although this tendency is not strong. Overall, the findings confirm the strong divide of Belgian politics along language lines and Belgium’s ‘partitocracy’ in which parties are the main actors in the representation and policy-making process.

Introduction

Peer networks represent core components of politicians’ lives, allowing them to build relationships, create a reputation, and gain power. With the increase of social media use among political elites, analyzing politicians’ social network interactions has gained a prominent place in political science (e.g. Boireau et al. Citation2015; Guerrero-Solé and Lopez-Gonzalez Citation2019; Jungherr Citation2016). A large part of this research has focused on social network homophily, defined as the tendency of networks being formed among individuals sharing the same characteristics (McPherson et al. Citation2001; Shorish and Ackland, Citation2014). Previous studies have particularly emphasized the role of partisanship. This research has identified a strong tendency among politicians to interact with co-partisans and thus a tendency of homophily along party lines (e.g. Aragón et al. Citation2013; Cherepnalkoski et al. Citation2016; Hsu and Park Citation2012; Plotkowiak and Stanoevska-Slabeva Citation2013; see however Esteve Del Valle et al. Citation2021). Less attention has been paid to other characteristics than partisanship which may also drive the tendency of network homophily among political elites. Given the growing importance of multilevel governance in contemporary societies (Bache et al. Citation2016; Enderlein et al. Citation2010; Schakel et al. Citation2015), in which political activity takes place within and across multiple policy levels, understanding network homophily along the policy levels or parliament lines is particularly relevant. On the one hand, multilevel governance relies on interaction and cooperation (Happaerts Citation2015; Swenden Citation2006; Watts Citation2008) suggesting little tendency for homophily along parliament lines but rather significant interaction between candidates campaigning for different parliaments. On the other hand, however, each level of policy making tends to have its own competencies and responsibilities (Hooghe et al. Citation2016), and candidates campaigning for different parliaments may thus have an interest in and focus on different policy issues in their campaigns. Hence, there may be a tendency among candidates campaigning for the same parliament to retweet each other.

Characteristic of many multilevel systems is also their cultural diversity, often taking the form of language diversity (e.g. Belgium, Switzerland, Canada; Gagnon and Tully, Citation2001; Seymour and Gagnon, Citation2012). Therefore, to fully disentangle the puzzle of homophily in multilevel settings, we compare the degree of network homophily along parliament lines with the degree of homophily along language lines. In addition, we compare the extent of network homophily along parliament and language lines with homophily along party lines, as previous research has highlighted politicians’ tendency to (mostly) interact with co-partisans and thus a tendency of homophily along party lines. In summary, the question motivating our research note is: To what extent does network homophily occur along parliamentary, language and partisan lines among political candidates in multilevel settings? Answering this question will help us better understand information flows between candidates of different parliaments, language groups and parties. In particular, in times of increasing polarization and so-called ‘echo chambers’ (e.g. Conover et al. Citation2012) preventing effective debate and consensus across parliaments, languages and parties (e.g. Sunstein Citation2007). In addition, peer influence in social networks may impact opinions and attitudes (Sunstein, Citation2007). Hence, the pattern of who interacts with whom may help explain politicians’ behaviour (e.g. voting patterns), and thus improve our understanding of their actions.

Our study focuses on Belgium. Belgium is a federal political system with local, regional, federal and European levels of policymaking, with a linguistically divided polity in which political parties play a crucial role in policy-making (Deschouwer Citation2012). Hence, Belgium is a particularly relevant case for our analysis of network homophily along parliament, language and party lines in multilevel settings. To answer our research question, we examine Twitter interactions of political candidates who campaigned during the May 2019 regional, federal or European election campaign. As such, our study also shows the use of candidates’ activity on social media as an innovative way to analyse dynamics in multilevel political systems.

Following previous research which showed that retweets can be successfully used to recover party membership and to study party cohesion (Weaver et al., Citation2018; Vliet et al., Citation2021; Wüest et al., Citation2021), we use retweets to measure candidate networks. Retweeting refers to the practice of forwarding other users’ tweets and is a key mechanism for the diffusion of information on Twitter. We rely on a unique dataset of 20 061 retweets between 935 candidates active on Twitter who retweeted another candidate or who were retweeted themselves by another candidate.

Given the specific characteristics of the Belgian federal system, we begin our research note with a presentation of the Belgian case. We then present a brief theoretical section before moving to the main part of this research note, which is the empirical section.

The Belgian Case

The contemporary Belgian federal system has two types of federated entities: three regions (the Flemish, Walloon and Brussels-Capital Region) and three communities (the Flemish, French and German-speaking Community). The Flemish Community and the Flemish Region are merged (there is only one Flemish government and parliament), whereas the Walloon Region and the French Community are not.Footnote1 In the bilingual capital Brussels, arguably the most complex piece of the Belgian federal puzzle, the Brussels-Capital Region deals with regional competences, while the Flemish and French Communities deal with community issues. Note that the Belgian federal system is the result of a steady evolution of consecutive state reforms. For instance, while the first state reform goes back to 1970, the first direct elections for the Flemish and Walloon parliaments were only issued in 1995, and it evidently took time for parties and politicians to adapt to the changing institutional context (see e.g. the discussion of regional-federal coalition congruence by Deschouwer, Citation2009, and the analysis of legislative career orientations by Dodeigne, Citation2018).

By nature, multilevel politics often comes with cultural, language, ethnic or other forms of diversity, and Belgium is a textbook example of a ‘divided society’ characterized by segmental cleavages along language lines (Lijphart Citation1977). This language division also marks the Belgian party system. Parties in Belgium compete in separate party systems divided along language lines and they only aim to attract voters of their own language group (Deschouwer Citation2002). Voters in Flanders can only vote for Dutch-speaking parties, while voters in Francophone Belgium can only vote for Francophone parties. All parties in contemporary Belgium are thus ‘regional’ parties (Brancati Citation2008). However, there are several notable exceptions: (1) the situation in the Brussels-Capital Region (and six surrounding municipalities with so-called ‘language facilities’), where Dutch-and French-speaking parties compete for the votes of both Dutch-and French-speaking voters, (2) the radical leftist PVDA/PTB, which is the only existing statewide party, and (3) some parties that sometimes present lists in other language communities (e.g. the lists of the Flemish populist radical right party Vlaams Belang in electoral districts in Wallonia).

Belgium is also often described as a ‘partitocracy’; a system in which political parties are crucial actors and in which they have an important impact on policy-making (e.g. De Winter et al. Citation1996; De Winter Citation1998; De Winter and Dumont Citation2006). This position of parties is reflected in Belgium’s electoral system. The flexible list Proportional Representation (PR) electoral system combines preference votes (votes for individual candidates) with list votes (votes for party lists), but in reality, a candidate’s chances of being elected largely depend on their list position (Put et al. Citation2014).

Social Media Network Homophily During Election Campaigns in Multilevel Settings

A common feature of social networks of all types is the clustering of individuals that have similar attributes, known as homophily (McPherson et al. Citation2001). For example, social media users tend to follow and retweet others who share their political views (Mosleh et al. Citation2021; Conover et al. Citation2012). Homophilic interactions along party lines have also been consistently found among politicians (e.g. Aragón et al. Citation2013; Cherepnalkoski et al. Citation2016; Hsu and Park Citation2012; Plotkowiak and Stanoevska-Slabeva Citation2013; see however Esteve Del Valle et al. Citation2021). But to what extent does this tendency of politicians to create groups with colleagues with similar characteristics also hold for other attributes than party affiliaton? With the importance of multilevel governance growing across the globe (Bache et al. Citation2016; Enderlein et al. Citation2010; Schakel et al. Citation2015), we are particularly interested in the extent to which politicians tend to interact with politicians campaigning for the same parliament and talking the same language.

Typical of multilevel governance is its reliance on cooperation between different levels of policy making or parliaments (Happaerts Citation2015), suggesting little tendency of network homophily along parliament lines. The extent to which cooperation and interaction between parliaments is needed and encouraged, however, differs between different types of federal systems. Federal systems can be placed on a continuum ranging from ‘dual’ to ‘cooperative’ federalism (e.g. Swenden Citation2006; Watts Citation2008). The dual federal system is characterized by exclusive competences and by the fact that each government is responsible for both its own legislation and the implementation of policies. In such dual federalism, the need and tendency to cooperate between different levels of policy making is much smaller than in cooperative federal states. Cooperative federal states are characterized by overlapping competences and by legislative and executive aspects of policy-making pertaining to different levels of government (at least when it comes to certain policy domains). In such states, the federal parliament can thus adopt laws that need to be implemented by the regions (or vice versa).

As Belgium is a federation that leans towards the ‘dual’ end of the continuum (e.g. Swenden Citation2006), we may thus expect relatively little interactions between the different levels of policy making. Several nuances may, however, reframe this expectation. While exclusive competences are the standard in Belgium, different aspects of a certain policy domain are often attributed to different levels of government. Regarding transport policy, for example, road transport, seaports, regional airports and public transport are subnational competences, but the federal government controls rail transport and the national airport (Happaerts Citation2015). For coherent policies to be adopted, intergovernmental cooperation is thus an imperative (Swenden and Jans Citation2006; Poirier Citation2002). In addition, Europeanisation forces the regional and the federal levels of government to cooperate (Beyers and Bursens Citation2006). Furthermore, policy levels tend to be mixed up when elections coincide as parties try to develop programmes ‘fitting all levels’ (De Winter and Dumont Citation2006, 945; Bouteca et al. Citation2017).

Characteristic of many multilevel systems is also their cultural diversity, often taking the form of language diversity (e.g. Belgium, Switzerland, Canada; Gagnon and Tully Citation2001; Seymour and Gagnon Citation2012). To truly understand the dynamics of political interaction in multilevel contexts, the role of this division can thus not be ignored. In Belgium, language diversity takes the shape of virtually separate sub-societies, as parties, news media, etc. tend to be organized along language lines (e.g. Deschouwer Citation2002; Lijphart Citation1977, Citation2008). One political-institutional expression of this division is the above-mentioned split of the Belgian party system, which implies that parties compete in separate party systems split along language lines (Deschouwer Citation2002). This is thought to give elites little incentive to cooperate and interact across language lines (Horowitz Citation1985; Caluwaerts and Reuchamps Citation2015). Hence, we expect to see a ‘language border’ throughout the clusters of candidates’ networks. We do, however, expect this language border to be stronger among some candidates compared with others. In particular, we anticipate candidates for the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region to be the most likely to also form networks with candidates who speak a different language. While the election of the Brussels regional Parliament is organized separately in the two language groups (only unilingual lists can be presented), all Dutch-speaking and French-speaking candidates for the Brussels regional Parliament do compete in the exact same arena and can gain support from both French – and Dutch-speaking voters (Coffé Citation2006). Hence, they have an incentive to interact with candidates of the other language group throughout the campaign. This is a major difference compared with candidates campaigning for the European or federal parliament, in which different language groups are represented but whose candidates can (some marginal exceptional situations aside) only gain support from voters of their own language group, and who are thus only accountable to their own language community (Caluwaerts and Reuchamps Citation2015).

Data

To examine network homophily among candidates in Belgium’s multilevel political system, we rely on Twitter data collected during the four months preceding the 26 May 2019 regional, federal and European elections among candidates who were active on Twitter campaigning in these elections. We collected data for all candidates from parties represented in at least one Parliament before the 2019 elections (see in the appendix).Footnote2 The candidates’ language is defined by the party they campaigned for, thus candidates campaigning for a seat in the Belgian House of Representatives for a Dutch-speaking party were considered as Dutch speaking.Footnote3 The candidates’ parliament is measured by the parliament that the candidate was campaigning for. A candidate could only campaign for one parliament.

We evaluate the networks formed by candidates based on their retweeting behaviour, which is the practice of forwarding other users’ tweets. Despite the commonly encountered assertion that ‘retweets are not endorsements’ (Freelon Citation2014, 67), existing research shows that retweeting behaviour is overwhelmingly a form of endorsement, in particular when it comes to political discussions (Cherepnalkoski et al. Citation2016; Guerrero-Solé and Lopez-Gonzalez Citation2019). Retweet networks are very homogeneous, and at the same time, there is high polarization between networks, suggesting that retweets show support for politically like-minded messages (Himelboim Citation2014; Guerrero-Solé Citation2018). The meta-study by Metaxas et al. (Citation2021, 658) confirmed that retweeting not only indicates ‘interest in a message, but also trust in the message and the originator, and agreement with the message contents.’ In addition, a focus on retweets allows the study of dynamic interactions (as opposed to more static interactions based on followers) (Boireau et al. Citation2015), and retweets also tend to show more stable patterns than activities such as tagging (Lietz et al. Citation2014) and may as such offer more temporarily generalizable results.

In this study, we rely on direct retweets, in which a candidate retweets another candidate’s tweet. The social media networks of retweets that we analyze are mathematical constructs in which candidates are nodes (or vertices), and edges are links that form between the nodes if candidates retweet each other (Tsvetovat and Kouznetsov Citation2011). The edges are weighted by the number of retweets between the candidates. Since we focus on patterns of interaction in general, we treat edges as undirected, allowing retweets from either direction to contribute to the weight of the edge.

Data were collected for a total of 3624 candidates of which 1157 were active Twitter users during the four months preceding the 26 May 2019 elections, corresponding to the period during which legal restrictions for campaign expenditure applied. The timelines of these 1157 candidates were collected through the Twitter REST API, which resulted in more than 171 000 tweets, 69 000 of which were retweets. Almost a third of the retweets (20 065) were between pairs of candidates, and 80% of the candidates who tweeted during the campaign (935) retweeted at least one other fellow candidate or were retweeted by at least one other candidate.Footnote4 More than 95% of these candidates (890) directly retweeted another candidate, while fewer than 5% (45) were retweeted by another candidate but did not retweet others.Footnote5 in the appendix provides an overview of the number of candidates and their retweets of other candidates by party, language, parliament and parliament/language (excluding candidates who did not retweet others, and for which the number of retweets is therefore 0).

Visualizing Retweet Networks

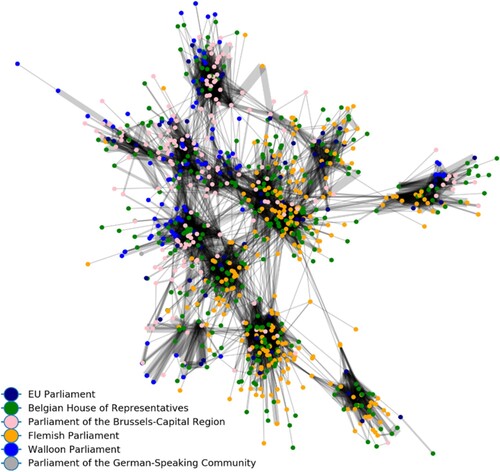

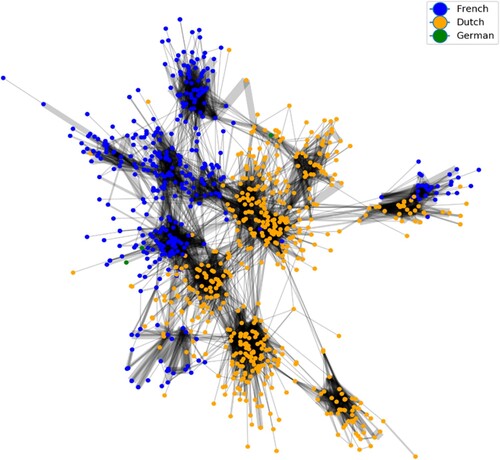

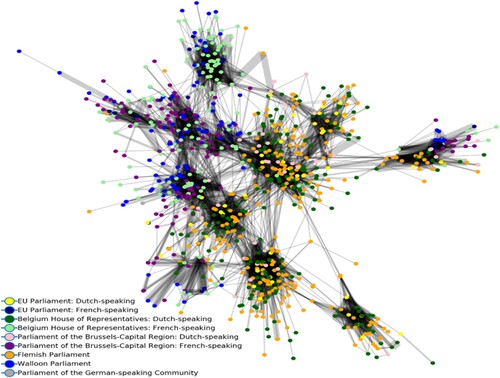

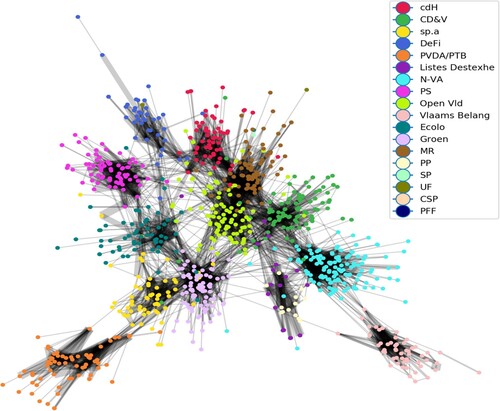

To visualize the networks of candidate retweets in a two-dimensional space we use the force-directed Fruchterman and Reingold (Citation1991) algorithm implemented within the Python package NetworkX (Hagberg, Swart and Schult Citation2008). The nodes represent parliamentary candidates, while the edges (connecting lines) between them correspond to links formed between nodes when they retweet each other. The algorithm positions the nodes in a two-dimensional space such that highly connected nodes are placed closer to one another while attempting to keep edge lengths as similar as possible, and minimizing edge crossings. This allows us to visualize the extent to which candidates are connected to each other through their retweeting behaviour, as well as the patterns of connectedness that appear at the network level. As a standard step that allows us to visualize the networks and compute our measures of homophily, nodes that are isolated (retweeting only themselves or one other disconnected node) and nodes that are not part of the main connected network component are removed from the analysis. However, none of the candidates in our analysis retweeted only themselves, and only three candidates were linked to only one other candidate, being therefore removed from the network analysis.Footnote6 To visualize the extent to which attributes are relevant for the observed network patterns, nodes are coloured according to different candidate attributes: parliament (), language (), parliament/language () and party ().

As can be seen from , there is some tendency of candidates for each parliament to form distinct groups. Yet, many interactions also occur across parliaments. shows that language is an important homophily driver in Belgium’s multilevel setting, with clear clusters developing among French-speaking and Dutch-speaking candidates respectively and with relatively few interactions between French – and Dutch-speaking candidates.

presents the same network of candidates as but in this case, candidate nodes are coloured by parliament and language. It provides further support for the importance of language as it shows a tendency of candidates campaigning for the same parliament and speaking the same language to form distinct clusters, explaining some of the observed inter-parliamentary links that we observed in . Finally, shows that nodes from the same party clearly cluster together, confirming previous research suggesting strong network homophily along party lines.

Measures of Homophily

While the above figures are illustrative and indicate for each attribute the tendency towards network homophily, it is important to assess the extent to which different candidate attributes contribute to the observed network structure through directly comparable statistical measures. To that end, we evaluate homophily along parliament, language, parliament/language, and party lines by reporting (1) a network-level measure of attribute assortativity, and (2) subnetwork average weighted degree measures. The first measure allows us to evaluate the intensity of homophily on each attribute of interest. It can, for example, show if homophily within the entire network of candidates is stronger for party affiliation than for language or parliament. The second measure allows us to compare the strength of interactions between candidates sharing the same characteristics on each attribute of interest, and identify the sub-groups (thus which specific political party, parliament and language) that show the greatest tendency of homophily.

Assortativity

Assortativity, or the assortativity coefficient, is a widely-used network-level statistical measure that captures the tendency of nodes to be connected with others who are similar on a certain characteristic (Newman, Citation2003). The measure lies between −1 and 1, with 1 indicating that the network has perfect assortative mixing patterns, 0 indicating that the network is non-assortative, and −1 indicating the network is completely disassortative. A perfectly disassortative network is one in which every edge connects nodes of different types on the attribute of interests. Conversely, a perfectly assortative network is one in which edges exist only between nodes that share the attribute of interest. The higher the measure of assortativity, the stronger the tendency towards homophily on the attribute of interest.

presents the assortativity coefficient for each dimension and reveals that language has the highest assortativity coefficient (0.883), very closely followed by party membership (0.882). The coefficients thus confirm the strong language and party homophily patterns observed in and above. The assortativity coefficient for parliament is 0.205, suggesting modest assortative mixing patterns along parliament lines. The assortativity coefficient for the combined parliament/language attribute is (slightly) higher compared with the coefficient for parliament only, further confirming the relevance of language within parliament networks.Footnote7

Table 1. Attribute assortativity measures.

Average weighted degree

Our second measure of homophily, the average weighted degree, investigates possible differences in the strength of homophily between different groups with shared identities. For example, it allows us to investigate whether network homophily along parliament lines is stronger in some parliaments compared with other parliaments, or which specific party shows the greatest tendency of a strong intraparty network. While the assortativity coefficient considers the entire network, the average weighted degree measure focuses on each sub-network based on a candidate characteristic (parliament, language, parliament/language and party) separately. The measure reports the average of the weighted degree measure of the nodes within a sub-network (e.g. the federal or Flemish parliament). In general, within a network, the degree of a node is calculated as the number of connections the node has with other nodes. If these connections are weighted (in our case by the number of retweets between each pair of nodes in a subnetwork), the degree of a node is the sum of the weights of its links. The average weighted degree measure that we report is simply the sum of these weighted node degree measures for each sub-network (in our case based on parliament, language, parliament/language or party), divided by the total number of nodes within that sub-network. Given that all nodes in our network are connected by design, the minimum average weighted degree is 0. The higher the average weighted degree within a sub-network, the more intense the interactions between candidates campaigning within a particular language group, party, parliament or parliament/group.

reports the average weighted degree measure for different sub-groups. Starting with the average weighted degree measure by language groups – the main driver of homophily as seen in above-, the high and comparable scores for the group of Dutch – and French-speaking candidates suggest that candidates of both groups have intense and similar levels of interaction with candidates of their own language group.

Table 2. Average weighted degree measures for party, language, parliament and parliament/language groups.

Moving on to the measures for parliament and parliament/language, shows quite a lot of diversity in the average weighted degree measures between the different parliaments and parliament/language groups. The Belgian House of Representatives is the parliament within which homophily is highest. In particular, French-speaking candidates campaigning for the Federal House display strong homophilic tendencies. The lowest score can be observed for the Walloon parliament. Of the regional parliaments, the candidates of the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital region are the most intensely connected. The overall average weighted degree measure for the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital region is also higher than the separate scores for the network of the Dutch-speaking and the network of the French-speaking candidates within that same parliament. This suggests that links between the two language groups in the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region are more intense than among candidates of the same language group campaigning for the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region. By contrast, in the Belgian House of Representatives where the two languages are also represented, the tendency towards homophily is stronger for each language group separately than it is for the parliament overall. These differences may be explained by the fact that the Brussels-Capital parliament is also the only parliament in which all candidates (whether Dutch – or French-speaking) compete for the vote of both Dutch – and French-speaking voters, which might encourage interactions across language lines.

Finally, the results for parties also show some notable differences between parties, with the average weighted score measure ranging between 2.00 for the Union Francophone (a small French-speaking party that participates at the regional Flemish, provincial and local elections in Flemish Brabant) and 50.64 for the left-wing and bilingual PVDA/PTB party. The latter has the strongest within-party connections of all parties – and thus the strongest level of homophily – followed by the candidates of the French-speaking mainstream right-party MR. There does not seem to be a pattern of a particular party family showing more or less tendency of homophily. For example, while the French-speaking Green party Ecolo only has a score of 16.39 on the average weighted score measure, its Dutch-speaking counterpart has a score of 37.90 (the highest score of all Dutch-speaking parties).

Conclusion

The main goal of our research note was to better understand network homophily among political candidates in multilevel political settings by investigating the extent to which candidates campaigning for the same parliament and candidates speaking the same language tend to mainly interact among themselves. This tendency of homophily along parliament and language lines was compared with network homophily along party lines, as previous research consistently showed that communication flows among politicians tend to be polarized along party lines.

Relying on Twitter (retweet) networks among candidates participating in the May 2019 regional, federal and European elections in Belgium, we provided an innovative way to assess political interactions in multilevel systems. Our results revealed a strong tendency of homophily along language lines; a tendency which is similarly strong among Dutch – and French-speaking candidates. Our analyses also showed some tendency among candidates to retweet messages from candidates campaigning for the same parliament, but this tendency was notably less strong than the network homophily along language lines. In the Belgian multilevel context, the different parliaments are not in isolation from each other. There is significant interaction between the different parliaments and levels of policy making. Studies on the careers of MPs in multilevel contexts, and the Belgian context in particular, have also shown that MPs do move from one level to another (Borchert & Stolz, Citation2011; Pilet, Tronconi, Onate & Verzichelli, Citation2014; Vanlangenakker, Maddens & Put, Citation2013), confirming the idea that parliaments are not isolated from one another own.

Confirming previous research (e.g. Boireau et al. Citation2015) and in line with the paritocratic nature of Belgian politics (De Winter et al. Citation1996; De Winter Citation1998; De Winter and Dumont Citation2006), party affiliation also turned out to be a highly important indicator for network formation, though differences in the tendency to form strong intraparty networks clearly differed between parties.

In sum then, in the multilevel and multilanguage Belgian political context which is also characterized by a strong ‘partitocracy’, we see some pattern of intra-parliamentary networks, but the connections within language groups and within parties are much stronger. For a multilevel setting, which relies on the interaction between different levels of policy making and parliaments for effective policy making, it can be seen as a positive aspect that the tendency for homophily along parliament lines is relatively limited as it suggests (online) social connections between peers campaigning for different parliaments. By contrast, the strong tendency of homophily along party lines suggests that candidates interact online mostly with like-minded colleagues. Similarly, the strong network homophily along language lines implies little interaction between both language groups, inhibiting information flow between language groups and as such corroborating the move of Belgium’s political system towards two separate systems.

Since our study focuses only on one country, Belgium, the question remains to what extent the findings are generalizable to other contexts. In particular, given the specific features of Belgium’s federal system, including its complex structure, its dual nature of federalism, its separate party systems divided along language lines, and its language diversity, further research could usefully investigate to what extent our results also hold in other multilevel systems (e.g. cooperative federal systems with state-wide parties and without language divisions, like Germany). When doing so, researchers can rely on the two measures of network homophily presented in the current study, as these can be easily applied to other multilevel settings. Although differences in networks may be expected between e.g. cooperative and dual federal states, these differences are not expected to be large. Belgian parties often mix up policy levels in the run-up towards elections (De Winter and Dumont Citation2006; Bouteca et al. Citation2017), and several features, e.g. the role of Europeanisation and the fact that different aspects of a policy domain are often attributed to different governments, already push Belgian politicians towards interaction and cooperation (Beyers and Bursens Citation2006; Swenden and Jans Citation2006; Poirier Citation2002).

Future research could also usefully use the same type of data and methodological approach as did in our study, and – ideally with a more extensive dataset – further explore interactions between candidates’ characteristics. While we did include the interaction between language and parliament, other interactions, such as those between parliament and party would be interesting. It is indeed possible that candidates from the same party have different networks depending on the parliament for which they are campaigning, depending for example of whether their party is an opposition or governmental party in a particular parliament.

A final interesting avenue for future research would be a study among elected MPs investigating to what extent the patterns among political candidates revealed in the current study also hold among elected parliamentarians and outside of election campaigns. It seems particularly interesting to explore to what extent the pattern of inter-parliamentary connections found among candidates also occurs among MPs or whether – once elected – MPs tend to form strong intra-parliamentary networks.

Acknowledgement

The first author would like to thank the Politics, Languages and International Studies Department of the University of Bath for the financial support to conduct the project. Previous versions of the paper have been presented at the CLP-GASPAR (Ghent University) research seminar, the 2019 ECPR General Conference and the 2019 ECPR Standing Group on Parliaments Conference. The authors would like to thank all participants for their useful feedback and suggestions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The 94 MPs of the Parliament of the French Community are not elected directly. This parliament consists of all 75 members of the Walloon Parliament (except the German-speaking members, who are replaced by French-speaking members from the same party) and 19 members elected by and from the French language group of the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region.

2 The PVDA/PTB is the only ‘national’ party, and while its Dutch-speaking part (PVDA) was not represented in the Flemish Parliament or the Belgian House of Representatives before the 2019 elections, we did include the PVDA candidates in our study as polls organized before the elections indicated that some of the party’s candidates would enter the Flemish Parliament and Belgian House of Representatives, which they did.

3 The most challenging cases were the candidates campaigning for the bilingual list PVDA/PTB list for the federal parliament in the Brussels-Capital constituency. In those cases, we checked the candidates’ websites, Twitter accounts, campaigning material, etc. to define whether they are Dutch- or French-speaking.

4 The proportion of candidates from each party included in our analysis reflects the size of the political parties as measures by the proportion of votes and seats received in the 2019 and 2014 federal elections.

5 We observed no unusual pattern in the distribution of characteristics in terms of parliament, party affiliation and language within the subset of candidates who were retweeted by other candidates but did themselves not retweet others.

6 Their background characteristics are as follows: 2 French-speaking and 1 Dutch-speaking; 2 from PS and 1 from SP.A; 2 competing for the parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region and 1 for the Walloon Parliament.

7 There is little homophily along the lines of level of governance (regional, federal or European). The assortativity score is 0.075.

References

- Aragón, P., K. E. Kappler, A. Kaltenbrunner, D. Laniado, and Y. Volkovich. 2013. “Communication Dynamics in Twitter During Political Campaigns: The Case of the 2011 Spanish National Election.” Policy & Internet 5 (2): 183–206.

- Bache, I., I. Bartle, and M. Flinders. 2016. “Multi-level Governance.” In Handbook on Theories of Governance, edited by Christopher Ansell, and Jacob Torfing, 486–498. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Beyers, J., and P. Bursens. 2006. “The European Rescue of the Federal State: How Europeanisation Shapes the Belgian State.” West European Politics 29 (5): 1057–1078.

- Boireau, M., M. Gagliolo, E. van Haute, and L. Sudulich. 2015. “The Determinants and Dynamics of Twitter-Based Interactions Among Candidates.” Paper Presented at the Workshop ‘Digital Media, Power, and Democracy in Election Campaigns’, Washington, DC.

- Borchert, J., and K. Stolz. 2011. “Introduction: Political Careers in Multi-Level Systems.” Regional & Federal Studies 21 (2): 107–115.

- Bouteca, N., E. D’heer, and S. Lannoo. 2017. “How Second-Order is the Regional Level? An Analysis of Tweets in Simultaneous Campaigns.” Political Studies 65 (4): 1021–1039.

- Brancati, D. 2008. “The Origins and Strengths of Regional Parties.” British Journal of Political Science 38: 135–159.

- Caluwaerts, D., and M. Reuchamps. 2015. “Combining Federalism with Consociationalism: Is Belgian Consociational Federalism Digging Its Own Grave?” Ethnopolitics 14 (3): 277–295.

- Cherepnalkoski, D., A. Karpf, I. Mozetič, and M. Grčar. 2016. “Cohesion and Coalition Formation in the European Parliament: Roll-Call Votes and Twitter Activities.” PloS ONE 11 (11): e0166586.

- Coffé, H. 2006. “‘The Vulnerable Institutional Complexity.’ The 2004 Regional Elections in Brussels.” Regional and Federal Studies 16 (1): 99–107.

- Conover, M. D., B. Gonçalves, A. Flammini, and F. Menczer. 2012. “Partisan Asymmetries in Online Political Activity.” EPJ Data Science 1: 6.

- De Winter, L. 1998. “Parliament and Government in Belgium: Prisoners of Partitocracy.” In Parliaments and Executives in Western Europe, edited by Philip Norton, 97–122. London: Frank Cass.

- De Winter, L., D. della Porta, and K. Deschouwer. 1996. “Comparing Similar Countries: Italy and Belgium.” Res Publica (liverpool, England) 38: 215–236.

- De Winter, L., and P. Dumont. 2006. “Do Belgian Parties Undermine the Democratic Chain of Delegation?” West European Politics 29 (5): 957–976.

- Deschouwer, K. 2002. “Falling Apart Together. The Changing Nature of Belgian Consociationalism.” Acta Politica 37: 68–85.

- Deschouwer, K. 2009. “Coalition Formation and Congruence in a Multi-Layered Setting: Belgium 1995–2008.” Regional & Federal Studies 19 (1): 13–35.

- Deschouwer, K. 2012. The Politics of Belgium: Governing a Divided Society. 2nd ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dodeigne, J. 2018. “Who Governs? The Disputed Effects of Regionalism on Legislative Career Orientation in Multilevel Systems.” West European Politics 41 (3): 728–753.

- Enderlein, H., S. Walti, and M. Zurn. 2010. Handbook on Multi-Level Governance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Esteve Del Valle, M., M. Broersma, and A. Ponsioen. 2021. “Political Interaction Beyond Party Lines: Communication Ties and Party Polarization in Parliamentary Twitter Networks.” Social Science Computer Review, Advance Online Publication. Doi: 10.1177/0894439320987569.

- Freelon, D. 2014. “On the Interpretation of Digital Trace Data in Communication and Social Computing Research.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 58: 59–75.

- Fruchterman, T. M. J., and E. M. Reingold. 1991. “Graph Drawing by Force-Directed Placement.” Software: Practice and Experience 21 (11): 1129–1164.

- Gagnon, A.-G., and J. Tully. 2001. Multinational Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Guerrero-Solé, F. 2018. “Interactive Behavior in Political Discussions on Twitter: Politicians, Media, and Citizens’ Patterns of Interaction in the 2015 and 2016 Electoral Campaigns in Spain.” Social Media + Society October-November: 1–16.

- Guerrero-Solé, F., and H. Lopez-Gonzalez. 2019. “Government Formation and Political Discussions in Twitter: An Extended Model of Quantifying Political Distances in Multiparty Democracies.” Social Science Computer Review 37 (1): 3–21.

- Hagberg, A., P. Swart, and D. Schult. 2008. “Exploring Network Structure, Dynamics, and Function Using Networkx (LA-UR-08-05495; LA-UR-08-5495).” Los Alamos National Lab. (LANL), Los Alamos, NM (United States). https://www.osti.gov/biblio/960616-exploring-network-structure-dynamics-function-using-networkx.

- Happaerts, S. 2015. “Multi-Level Climate Governance and the Role of the Subnational Level.” Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences 12 (4): 285–301.

- Himelboim, I. 2014. “Political Television Hosts on Twitter: Examining Patterns of Interconnectivity and Selfexposure in Twitter Political Talk Networks.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 58: 76–96.

- Hooghe, L., G. Marks, A. H. Schakel, S. C. Osterkatz, S. Niedzwiecki, and S. Shair-Rosenfield. 2016. Measuring Regional Authority: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Volume I. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Horowitz, D. L. 1985. Ethnic Groups in Conflict. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hsu, C-l., and H. W. Park. 2012. “Mapping Online Social Networks of Korean Politicians.” Government International Quarterly 29: 169–181.

- Jungherr, A. 2016. “Twitter use in Election Campaigns: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 13 (1): 72–91.

- Lietz, H., C. Wagner, A. Bleier, and M. Strohmaier. 2014. “When Politicians Talk: Assessing Online Conversational Practices of Political Parties on Twitter.” Proceedings of the Eighth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media: 285-294.

- Lijphart, A. 1977. Democracy in Plural Societies. A Comparative Exploration. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Lijphart, A. 2008. Thinking About Democracy: Power Sharing and Majority Rule in Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge.

- McPherson, M., L. Smith-Lovin, and J. M. Cook. 2001. “Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks.” Annual Review of Sociology 27: 415–444.

- Metaxas, P. T., E. Mustafaraj, K. Wong, L. Zeng, M. O. Keefe, and S. Finn. 2021. “What Do Retweets Indicate? Results from User Survey and Meta-Review of Research.” Proceedings of the Ninth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 9 (1): 658–661.

- Mosleh, M., C. Martel, D. Eckles, and D. G. Rand. 2021. “Shared Partisanship Dramatically Increases Social tie Formation in a Twitter Field Experiment.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (7), Doi: 10.1073/pnas.2022761118.

- Newman, M. E. J. 2003. “The Structure and Function of Complex Networks.” SIAM Review 45 (2): 167–256.

- Pilet, J.-B., F. Tronconi, P. Onate, and L. Verzichelli. 2014. “Career Patterns in Multilevel Systems.” In Representing the People: A Survey among Members of Statewide and sub-State Parliaments, edited by Kris Deschouwer, and Sam Depauw, 209–226. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Plotkowiak, T., and K. Stanoevska-Slabeva. 2013. “German Politicians and Their Twitter Networks in the Bundestag Election 2009.” First Monday 18 (5-6).

- Poirier, J. 2002. “Formal Mechanisms of Intergovernmental Relations in Belgium.” Regional and Federal Studies 12 (3): 32–50.

- Put, G.-H., J. Smulders, and B. Maddens. 2014. Een Analyse van het Profiel van de Vlaamse Verkozenen bij de Kamerverkiezingen van 1987 Tot en Met 2014. Leuven: KU Leuven.

- Schakel, A. H., L. Hooghe, and G. Marks. 2015. “Multilevel Governance and the State.” In The Oxford Handbook of Transformations of The State, edited by Stephan Leibfried, Evelyne Huber, Matthew Lange, Jonah D. Levy, and John D. Stephens, 269–285. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Seymour, M., and A.-G. Gagnon. 2012. Multinational Federalism: Problems and Prospects. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shorish, J., and R. Ackland. 2014. “Political Homophily on the Web.” In Analyzing Social Media Data and Web Networks, edited by Marta Cantijoch, Rachel Gibson, and Stephen Ward, 25–46. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sunstein, C. R. 2007. Republic.com 2.0. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Swenden, W. 2006. Federalism and Regionalism in Western Europe. A Comparative and Thematic Analysis. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Swenden, W., and M. T. Jans. 2006. “Will It Stay or Will It Go?’ Federalism and the Sustainability of Belgium.” West European Politics 29 (5): 877–894.

- Tsvetovat, M., and A. Kouznetsov. 2011. Social Network Analysis for Startups: Finding Connections on the Social Web. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media.

- Vanlangenakker, I., B. Maddens, and G. J. Put. 2013. “Career Patterns in Multilevel States: An Analysis of the Belgian Regions.” Regional Studies 47 (3): 356–367.

- Vliet, L., P. van Törnberg, and J. Uitermark. 2021. “Political Systems and Political Networks: The Structure of Parliamentarians’ Retweet Networks in 19 Countries.” International Journal of Communication 15 (0): 21.

- Watts, R. L. 2008. Comparing Federal Systems. 3rd ed. Kingston: Queens University.

- Weaver, I. S., H. Williams, I. Cioroianu, M. Williams, T. Coan, and S. Banducci. 2018. “Dynamic Social Media Affiliations among UK Politicians.” Social Networks 54: 132–144.

- Wüest, B., C. Mueller, and T. Willi. 2021. “Controlled Networking: Organizational Cohesion and Programmatic Coherence of Swiss Parties on Twitter.” Party Politics 27 (3): 581–596.

Appendix

Table A1. List of parties.

Table A2. Total number of candidates and retweets within each party, language group, parliament, and parliament/language.