ABSTRACT

There is a small window of opportunity at the beginning of semester for a university to provide commencing students with timely and targeted support. However, there is limited information available on interventions that identify and support disengaged students from equity groups without using equity group status as the basis for the contact. The aim of this study was to use learning analytics that were explainable to the end users to identify and support commencing undergraduate students at an Australian regional university. Non-submission of an early assessment item accurately identified disengaged students and those students with successful dialogue with the Outreach Team were less likely to receive a failing grade. Analysis of intersectionality revealed that student progress rate decreased with additional equity factors. A holistic conversation with the Outreach Team increased retention for equity students the following semester, indicating that explainable learning analytics can be used to support equity students.

Introduction

The first few weeks of university for a commencing student are of vital importance for both the institution and the student. There is a short opportunity from the time a student enrols for universities to support students in their transition to higher education. Established first year design principles highlight the need to provide early response systems for all students who appear to be disengaging through targeted communication regarding available support services (Kift, Citation2015; Meer et al., Citation2018). A recent systematic review on student retention found that targeted approaches can be effective, particularly when aimed at a specific student population, such as first year at-risk students (Eather et al., Citation2022). In the Australian context, both the Australian Higher Education Standards Panel (DESE, Citation2017) and the Grattan Institute (Norton et al., Citation2018) reports have included specific recommendations for universities to reduce student dropout and the associated costs which are borne by students and the Australian Government. These recommendations include monitoring student engagement early in semester to provide early academic support and enrolment advice to students prior to the date when they become financially liable for their units, referred to as the census date. This has been on the radar of many institutions however can be difficult to implement accurately at scale.

Widening participation has led to an increase in the number of students from non-traditional backgrounds accessing higher education. However, the higher education outcomes of students from disadvantaged backgrounds are consistently lower than more advantaged peers, despite significant investment (Tomaszewski et al., Citation2020). Student engagement and student success has been closely linked to support and well-designed transition pedagogy for commencing students (Kahu & Nelson, Citation2018). It is also clear that teaching practices and teaching spaces must adapt to adequately support students for future success (Tomaszewski et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, a strong policy commitment to access and retention is required (Yorke & Thomas, Citation2003). Student equity in higher education has been a focus of the Australian Government, establishing research and policy centres such the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education (NCSEHE). Research by NCSEHE and others in Australia often look at educational outcomes of student groups who have been marginalised and disadvantaged, often referred to as ‘equity group’ students. In Australia, there has been an increase in the number of students that not only belong to one equity group but to multiple equity groups. The effects on student outcomes as the number of equity factors increases are lower completion rates of courses as well as generally poorer outcomes throughout the course (Edwards & McMillan, Citation2015; Li & Carroll, Citation2020).

In Australia, if a student enrols and does not engage, neither the student nor the institution benefits; the student is generally still responsible for paying tuition fees, and the university’s progress rates are negatively impacted. Most domestic Australian students are studying with what are called commonwealth supported places. While there is some variation in the nature of the support that the commonwealth government provides, most students are receiving discounted tuition fees and defer the remaining costs through the Higher Education Loan Program. The Australian system has been described as a high cost, high support financial model for domestic students which is similar to the model used in the United Kingdom (OECD, Citation2021). In Australia, from the beginning of 2022, the onus shifted from the student towards the institution when the Job-ready Graduates package came into effect. The legislation includes increases to existing student protections which will aim to ‘ensure that only genuine students have access to commonwealth assistance’ (DESE, Citation2021). An institution will now be liable to refund the fees for students described in the legislation as non-genuine students. While the term ‘genuine student’ is loosely defined, it almost certainly would be intended to include students who do not submit any assessment items and receive zero-fail grades. This form of ‘ghosting’ behaviour is seldom reported and infrequently noticed by institutions, obscured by metrics such as progress rates (Stephenson, Citation2019). Ideally, students on track to receive a zero-fail could be identified early in the semester and provided with timely targeted support to remain enrolled and succeed or leave without financial penalty.

The changes to the student protections also include a requirement that students maintain a ‘reasonable completion rate’ in order to continue access to commonwealth support, which is defined by passing more than 50% of units after having completed eight or more units in a bachelor-level course (DESE, Citation2021). In practical terms, this means that for most students, especially those from low socioeconomic backgrounds, they will not be able to continue in their course if they fail to maintain the ‘reasonable completion rate’. Increasing students’ progress rates will therefore not only reduce students’ financial debt but may allow many students to continue studying in their course, perhaps to completion. As mentioned above, equity group students, especially those from multiple equity groups, are more likely to be affected by this new requirement for better or for worse.

In the Australian context, this paper is timely given the government is currently reviewing the entire higher education system through the Australian Universities Accord (DESE, Citation2023). Two of the seven areas for review in the terms of reference are relevant to this paper; access and opportunity and investment and affordability, with the latter area specifically reference a review of the Job-ready Graduates package mentioned above. Furthermore, the accord will address ‘what principles should underpin the setting of student contributions and Higher Education Loan Program arrangements?’ (DESE, Citation2023).

As early as 1999, universities have been using learning analytics to design predictive models that aim to identify students who are at risk of failing early in the teaching period so that support can be targeted to those in need (Campbell et al., Citation2007). Since then, there have been a wide variety of approaches to designing predictive at-risk models. Broadly speaking, models usually attempt to balance the equity group status, prior academic success and activity data of students to make predictions on student success with various levels of accuracy (Ifenthaler & Yau, Citation2020; Jayaprakash et al., Citation2014; Lacave et al., Citation2018; Tempelaar et al., Citation2018). Typically, these models have focused on providing accurate predictions and, however, have almost completely lacked any degree of explainability for the end users (Namoun & Alshanqiti, Citation2021). Moving forward, there have been calls to ensure that at-risk models include explainability. Foster and Siddle (Citation2020) adopted a simple and explainable approach, using a combination of ‘non-engagement’ alerts; 14 days of inactivity from the learning management system (LMS), building access, assessment submissions and library book loans (Foster & Siddle, Citation2020). Personal tutors then helped contextualise these alerts for the students. The authors note that these alerts focused on the student’s behaviour in the course, and did not rely on their equity group status, and in fact performed better than comparable models using such demographic features alone (Foster & Siddle, Citation2020).

Caution is advised when building equity group status into at risk models however, this can make it difficult to identify students in need of support early in the commencing semester, when little learning data are available (van der Ploeg et al., Citation2020). Another simple learning analytics model that may be more accurate is the non-submission of an early assessment item (Cox & Naylor, Citation2018; Linden, Citation2022; Nelson et al., Citation2009). Assessments are often used by students to define what is important in the curriculum (Kift, Citation2009). A low-stakes, early assessment valued from 5% to 20% can engage students with the unit of study in the early weeks of the semester. It can also provide an opportunity to help commencing students transition into university (Kift, Citation2009; Nelson et al., Citation2009). Non-submission of early assessments can be used to identify students who are not engaged and are thus at risk of failure or withdrawal (Cox & Naylor, Citation2018; Linden, Citation2022; Nelson et al., Citation2009).

In Australia, the census date at a university is when domestic students must decide if they wish to commit to studies for the given semester. The census date must be no earlier than 20% of the way through the semester and once past this date, students are liable to pay course fees (usually through the Australian Higher Education Loan Program) and will have unit grades added to their permanent academic record. There is a very short window to identify disengaged students and offer targeted support to ensure they can make an informed decision prior to census. In this study, student engagement was monitored in key first-year units across the institution in the first 4 weeks of semester 1, 2022. The aim of this study was to use learning analytics, specifically low LMS activity and non-submission of early assessment items to accurately identify disengaged students and provide timely and targeted support.

Methods

Charles Sturt is an Australian regional university that has six main teaching campuses across New South Wales and is one of the largest providers of online and blended learning in Australia. At Charles Sturt, the census date is on the Friday of the fourth week of a 14-week semester. All data presented in this study has been analysed from enrolments of domestic undergraduate students enrolled at Charles Sturt University in semester 1, 2022. Ethics approval was received from the Charles Sturt University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC Protocol No H21170).

No access to LMS up until week 2

A personalised email was sent to all students who had not accessed the LMS for any enrolled units in week 2 of semester, for all units with a median day of last access that was <3 days. This excluded units with very low LMS activity where students are not required to access the LMS such as work-integrated learning or large practical requirements. The email had a friendly tone advising students that the semester had commenced and provided instructions on how to access the LMS, unit coordinators or university support services. Student engagement was tracked daily for 2 weeks after the email was sent and recorded if a student became active and accessed the LMS; took no action; or withdrew from the unit.

Early identification and support of disengaged students

To identify disengaged students in weeks 3 and 4 of semester, 191 key units with a high proportion of commencing students were selected. These units had a combined enrolment of 15,034 students which included 80% of all commencing undergraduate students. A team focused on student retention worked directly with unit coordinators to incorporate best practice transition pedagogy as described previously (Linden, Citation2022). Academics were given one-on-one support and were provided with training and resources developed in accordance with first-year transition literature including the need to reduce cognitive load (Kift, Citation2009; Nelson et al., Citation2009). Clear and simplified LMS sites were created that were engaged and linked with vital support services available for commencing students. Unit coordinators could request prioritised access to educational designers to develop high quality, engaging low stakes early assessment, due at least 3 days before census.

In collaboration with the unit coordinator, the project team identified disengaged students in weeks 3 and 4 of semester 1, 2022. The timing was critical as it provided enough time to identify disengaged students and offer targeted support prior to the census date. Disengaged students were identified in one of two ways: non-submission of a low-stakes early assessment item, or by low LMS activity.

In 41 units that did not have an early assessment item, a ‘low LMS activity’ alert was used to identify students, based primarily on no LMS access for 10 days. Students were removed from the list if they had an academic history of 4 completed units, with no history of failure or with a high-grade point average (GPA); all remaining students on the list were identified as disengaged from the ‘low LMS activity’ alert and were contacted by the Student Outreach Team.

Non-submission of an early assessment item was used to identify disengaged students in the remaining 150 units. A modular data pipeline was created, including a bespoke web-based online form to facilitate efficient communication with unit coordinators at large scale. Unit coordinators were sent a pre-filled online form with the class list in alphabetical order and were asked to confirm the students with a tick who had not submitted the assessment. Students who had received an extension were unticked. The custom form also provided an opportunity for unit coordinators to include important contextual information at the student or unit level that was passed on to the Outreach Team. The process accounted for the fluidity of the data environment in the first few weeks of a semester with live enrolment and submission data.

A total of 1386 students were identified as disengaged due to either non-submission of assessment or low LMS activity. These students were proactively contacted by the Outreach Team via phone, two-way SMS, and a follow-up email and offered on-the-spot advice and referral to a variety of support services. The Outreach Team was also provided with specific context for the call, including details of the missed assessment item, last date of LMS access, and contextual information from the unit coordinator and previous outcomes of past students who had missed that same early assessment item. The first contact was usually made within 2 days of the assessment due date, and the conversation was supportive yet realistic.

Unit grades

Grade analysis was conducted on all official, substantive grades (n = 15,034) of students enrolled in the 191 monitored units. Grade data, student enrolments and demographics were downloaded from the Charles Sturt University data warehouse. Passing grades indicate that a student scored 50% or higher and failing grades have been divided into a non-zero fail (fail; 1–49%) or a zero-fail (0%), where no assessment items were submitted for that unit. Students could withdraw prior to census with no academic or financial penalty.

Intersectionality

Charles Sturt University is a proud regional university and enrols a high proportion of students from non-traditional backgrounds with 62% of students from a rural, regional or remote (RRR) region and 27% from a low socioeconomic status (Low SES) postcode. Additionally, 57% of students are first in family to study at university, 4.4% Australian First Nations, 7.3% living with a disability and 1.3% from a non-English speaking background (NESB). An unweighted additive approach to the analysis of intersectionality was used to investigate if the intervention could support students from multiple equity groups. Student progress rate was calculated based on the percentage of units passed and indicative retention was calculated as the student being enrolled in the following semester (semester 2, 2022).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was completed in GraphPad Prism (version 9.4.1). A Pearson’s Chi-squared test was used to determine statistical significance between grades of students with an extension vs identified as disengaged, and non-submission of assessment vs low LMS activity. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Limitations

It is important to note that this study is investigating whether students who responded to the intervention (successful dialogue with the Outreach Team) were more likely to pass and less likely to receive a zero-fail. Some of the students who responded positively to the interventions would have passed irrespective of the outreach contact. Future work should consider evaluating the efficacy of the interventions against a no-intervention control group, such as a randomised control trial.

Results

No access to LMS up until week 2

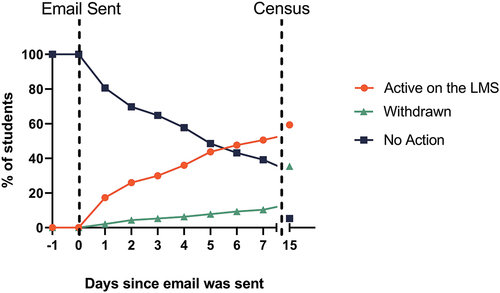

In week 2 of semester, 1913 students across the institution were enrolled, yet had not accessed the LMS. The day the email was sent, 17% of students accessed the LMS () and this number gradually increased over the following 2 weeks to 59% of the students emailed. After census, two weeks after the email was sent, 35% of students had withdrawn and 5% of students remained enrolled and had taken no action.

Early identification and support of disengaged students enrolled

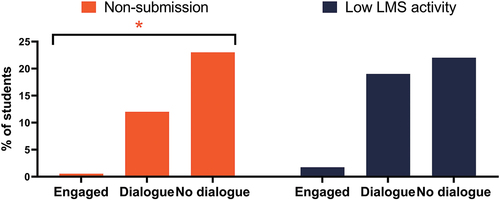

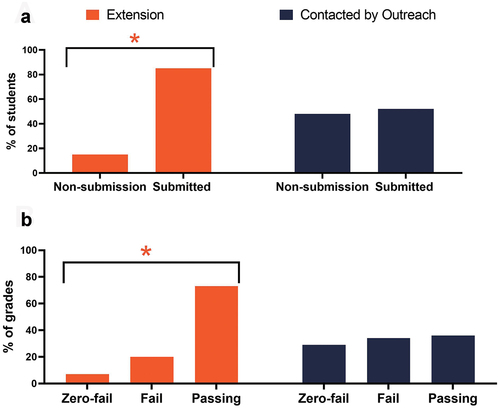

In weeks 3 and 4 of semester 1746 students were preliminarily identified as disengaged through both identification methods. A total of 21% of these students (360) were identified by unit coordinators as being engaged and receiving extensions. Of the students who received an extension, 85% who remained enrolled submitted the early assessment item () and 73% received a passing grade for the unit ().

Figure 2. (A) Submit ratio and (B) grades of students who received an extension and those who did not and were contacted by the Outreach Team. *Different to contacted by outreach, p < 0.001.

The remaining 1386 disengaged students without extensions were contacted by the Outreach Team and 519 subsequently withdrew from the unit prior to census. Of the students who remained enrolled, 165 students were identified in units with low LMS activity and 702 students were identified in units by non-submission of an early assessment item. Following outreach contact, 52% of students submitted the early assessment item () and 36% of these students received a passing grade. A following 29% of students remained enrolled and did not submit any assessment items (zero-fail) and 34% submitted at least one assessment and failed the unit (). Of these 1386 students, a high proportion (28%) were from a low socioeconomic background. This is many percentage points higher than both the university average (22%) and the Australian university sector average (approximately 17%).

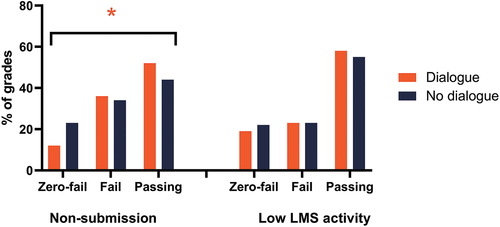

Irrespective of whether a unit used low LMS activity or non-submission of an assessment, 85% of students who were not identified as disengaged received a passing grade compared to 50% of students who were identified as disengaged (data not shown). The Outreach Team had successful dialogue via phone or 2-way SMS with 54% of students who remained enrolled post census. Students who were identified as disengaged were significantly more likely to receive a passing grade if they had successful dialogue with the Outreach Team (52% vs 44% p < 0.05; ). Students identified through low LMS activity were more likely to receive a passing grade (with or without dialogue) than those who were identified through non-submission of an early assessment item.

Figure 3. Zero-fail, fail and passing grades in units using non-submission of assessment (left) and low LMS activity (right). *Different to low LMS activity, p < 0.001.

The rate of zero-fail grades for students who were engaged was more than 3 times higher in units using low LMS activity than those using non-submission (1.73% vs 0.55%; ). Of the students identified as disengaged, the lowest incidence of zero-fail grades were from students who were identified through non-submission and who had successful dialogue with the Outreach Team.

Intersectionality

A total of 85% of students belonged to at least one equity group and 50% of students belonged to 2 or more equity groups (). As the number of equity factors increases from one to four or more, student progress rates decreased from 85% to 71%, respectively. There was an increase in the proportion of students with successful dialogue with the Outreach Team from students with one equity factor (34%) to four equity factors (69%). Following successful dialogue, the likelihood of a student being retained increased from 64% (0 equity factors) to 75% (4+ equity factors).

Table 1. Impact of targeted support by aggregated equity factors.

Discussion

Student engagement was monitored in the commencing semester, as most attrition occurs in the first year of university (Norton et al., Citation2018). The literature is clear that it is important to identify and support disengaged students early in their commencing semester (Foster & Siddle, Citation2020; Kift et al., Citation2010; Meer et al., Citation2018; Nelson et al., Citation2009). Early support for commencing students can help in a number of ways. Firstly, it can link students with academic assistance early in the semester, allowing students more time to improve their academic skills. These benefits are likely to be broadly relevant to most tertiary education contexts internationally. Additionally, in the context of the study, supportive contact was able to be made prior to census date when students become financially and academically liable for their units of study. This means that in addition to academic support, students could also receive support and advice regarding their enrolment decisions including explanation of the relevance of census date which has been explicitly identified as an area needing improvement in the sector (Norton et al., Citation2018). We show here that it is possible to accurately identify disengaged students through non-submission of an early assessment item, and to a lesser extent, low LMS activity. Both methods are explainable. Students who were identified as disengaged due to non-submission of assessment had poor academic outcomes and were the group least likely to receive a passing grade, and most likely to receive a zero-fail. Others have shown previously that monitoring non-submission of early assessment is an accurate method to identify disengaged commencing students (Cox & Naylor, Citation2018; Nelson et al., Citation2009) at a unit or Faculty level. Here we provide a scalable method that can be used across an institution.

An important aspect of the study was to develop the custom form and collaborate with the unit coordinators. The custom form enabled accurate and timely identification of students across the entire University who need support prior to census whilst simultaneously gathering important contextual information. The process accounted for the fluidity of the data environment in the first few weeks of a semester. Students are moving in and out of units, assessment due dates vary, whole class or individual extensions are being given, and communication between everyone involved happens across a multitude of channels. There were no processes that capture and store this data in a central location. These factors place a key restriction on using pure automation to scale such a program: the academics teaching the units are needed to provide critical information.

If a student has concerns or issues with an assessment item, lecturers in a unit are the logical people to contact. It has previously been reported that it is important that someone with course knowledge is involved in identifying students at risk (Foster & Siddle, Citation2020). Here we report that approximately 20% of students who were identified as disengaged were removed from the call list as they had already been in contact with their unit coordinator regarding extensions. Students who received an extension for the early assessment item were very likely to continue in the unit and submit the assessment and were almost as likely to receive a passing grade as students who were not identified as disengaged. By removing these students from the call list, the accuracy of the model was substantially increased.

The Outreach Team engaged in a holistic conversation regarding the student’s course enrolment. Successful dialogue with the Outreach Team resulted in significantly better outcomes for students enrolled in units that used non-submission of an assessment as a trigger for support, with just over half submitting the missed assessment item. This effect may be partially confounded due to unobserved factors influencing both student success and whether or not a student answers the call; however the positive result aligns with transition pedagogy literature where ‘just-in-time’ and ‘just-for-me’ support is key to a successful transition and to ensure that students are supported to learn and are then successfully retained (Kift, Citation2015). Students who were identified as disengaged in weeks 3 and 4 due to low LMS activity were less likely to be disengaged than students identified for non-submission of assessment, however, were still at greater risk of receiving a zero-fail or fail grade. These students saw no significant difference in grades with dialogue, as has been shown previously when outreach contact is not targeted to assessment (Schwebel et al., Citation2012). LMS activity is a much simpler process that can be automated at scale and is explainable to members of the Outreach Team, however, appears less effective in practically helping students. Feedback from the Outreach Team consistently states that their conversations with students are much richer when called about missed assessment compared to LMS access.

Another important finding from this study was the role of LMS activity data in identifying disengaged students. The email sent to students who had not logged onto the LMS for any units 2 weeks into the semester had an immediate impact with 20% of students taking action the day the email was sent. Only 5% of students remained enrolled and took no action by census. This is an incredibly low-cost way to nudge students into action and can easily be implemented across the institution (Bañeres et al., Citation2020).

Students from equity groups have been shown to have lower progress rates (Li & Carroll, Citation2020) and lower completion rates (Tomaszewski et al., Citation2020). Intersectionality was associated with a progressive decrease in student progress rates with more equity factors, consistent with previous studies showing poorer outcomes across the student life cycle (Tomaszewski et al., Citation2020). It has been shown that students that belong to equity groups feel a greater sense of belonging and support when they have clear direction. They benefit from interventions that are inclusive, providing timely and direct support (Kahu & Nelson, Citation2018). We show that following dialogue with the Outreach Team, as the number of equity factors increased, there was a progressive increase in the proportion of students who were retained and enrolled the following semester. Future work should investigate effective support to further increase progress and retention of equity students.

Of the students identified as disengaged in weeks 3 and 4, many remained enrolled and received a fail grade. These students should be offered follow-up academic support throughout the semester based on their level of engagement. A targeted approach to academic support may assist students who are showing some engagement yet are not on track to pass to avoid a fail grade. There are a number of studies that have shown evidence that tutors play a key role in the retention and success of students (Burgos et al., Citation2018; Linden et al., Citation2022). Further studies are needed to explore what other support, and how much support is needed to assist these students to academic success.

A simple at-risk model that includes non-submission of assessment or low LMS activity can identify students at risk of unit failure. Importantly, these systems for identifying students are transparent and are easily communicated with the outreach staff. While this can be the catalyst for timely outreach that benefits many students, there is still a group who choose to continue in their studies but never submit an assessment and eventually receive a zero-fail grade. The Job-ready Graduates package of legislation states that only ‘genuine’ students should have access to commonwealth supported places, as a student protection (DESE, Citation2021). It could be argued that some of these students are not sufficiently engaged for universities to justify charging tuition fees; however, practically managing this in real time would require careful thought. A Grattan Institute report suggested that universities could confirm with all students immediately prior to census that they wanted to continue in their subjects, asking all commencing students at census to ‘opt in’ or be removed (Norton et al., Citation2018). Rather than asking all students to do this, another option could be to use an ‘opt-in’ requirement, but only for the most disengaged students identified in weeks 3 and 4, who are at the highest risk of receiving a zero-fail. This could include a requirement for these students to complete a useful task, such as a study plan. This would simultaneously help the student realise how they can remain enrolled and succeed while also showing the university which students are genuine and sufficiently motivated to engage in their studies. The students who do not complete the study plan adequately would be removed from the unit or course. Another alternative for universities is to continue the status quo, allow all students to continue unless they actively remove themselves from units and focus on pouring more support in the hope that some might engage and succeed. In this approach, universities would have to reckon with the fact that they are sanctioning students to continue past census, knowing that at least some of them have little to no chance of success and will nevertheless still have to pay for it. All options have their advantages and disadvantages. Future research should explore this area.

Conclusion

Non-submission of an early assessment item, or low LMS activity early in semester provides an accurate early response to identifying disengaged students. In the Australian context, this can be achieved prior to the census date. Phone or 2-way SMS support can increase students’ chances of avoiding a failing grade, by either engaging in their studies or withdrawing prior to census, therefore avoiding academic and financial penalty. Despite targeted phone support many students remain enrolled and receive failing grades. In countries such as Australia and the United Kingdom, the tertiary education financial system involves governments paying the initial educational costs and providing deferred student loans to partially recover the expense. In these systems, to reduce the debt to the student, university and public, future studies should investigate if an ‘opt-in’ system might be more effective, where completely disengaged students must actively communicate their intent to study to remain enrolled. This study is particularly timely and relevant in the Australian context because the Australian University Accord is currently reviewing the Australian education system.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially funded by the Higher Education Participation and Partnerships Program (HEPPP). The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of former and current members of the Retention Team as well as academics and divisional staff who have supported the project. In particular, thank you to Ben Hicks, Wendy Rose Davison, Sarah Teakel and Alen Basic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, KL, upon reasonable request.

References

- Bañeres, D., Rodríguez, M. E., Guerrero-Roldán, A. E., & Karadeniz, A. (2020). An early warning system to detect at-risk students in online higher education. Applied Sciences, 10(13), 4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10134427

- Burgos, C., Campanario, M. L., Peña, D. D. L., Lara, J. A., Lizcano, D., & Martínez, M. A. (2018). Data mining for modeling students’ performance: A tutoring action plan to prevent academic dropout. Computers & Electrical Engineering, 66, 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2017.03.005

- Campbell, J.P., DeBlois, P. B., & Oblinger, D. G. (2007). Academic analytics: A new tool for a new era. Educause Review, 42(4), 40. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2007/7/academic-analytics-a-new-tool-for-a-new-era

- Cox, S., & Naylor, R. (2018). Intra-university partnerships improve student success in a first-year success and retention outreach initiative. Student Success, 9(3), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v9i3.467

- DESE. (2017). Improving retention, completion and success in higher education. Australian Government. https://www.dese.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/resources/higher-education-standards-panel-final-report-improving-retention-completion-and-success-higher

- DESE. (2021). Job-ready Graduates Package. Australian Government. https://www.dese.gov.au/job-ready

- DESE. (2023). Australian universities accord: Discussion paper. Australian Government. https://www.education.gov.au/australian-universities-accord/resources/australian-universities-accord-panel-discussion-paper

- Eather, N., Mavilidi, M. F., Sharp, H., & Parkes, R. (2022). Programmes targeting student retention/success and satisfaction/experience in higher education: A systematic review. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management, 44(3), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2021.2021600

- Edwards, D., & McMillan, J. (2015). Completing university in a growing sector: Is equity an issue? https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1045&context=higher_education

- Foster, E., & Siddle, R. (2020). The effectiveness of learning analytics for identifying at-risk students in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(6), 842–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1682118

- Ifenthaler, D., & Yau, J.Y. -K. (2020). Utilising learning analytics to support study success in higher education: A systematic review. Educational Technology Research & Development, 68(4), 1961–1990. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09788-z

- Jayaprakash, S.M., Moody, E. W., Lauría, E. J., Regan, J. R., & Baron, J. D. (2014). Early alert of academically at-risk students: An open source analytics initiative. Journal of Learning Analytics, 1(1), 6–47. https://doi.org/10.18608/jla.2014.11.3

- Kahu, E.R., & Nelson, K. (2018). Student engagement in the educational interface: Understanding the mechanisms of student success. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1344197

- Kift, S. (2009). First year curriculum principles: First year teacher http://transitionpedagogy.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/4FYCPrinciplesFirstYearTeacher_2Nov09.pdf

- Kift, S. (2015). A decade of transition pedagogy: A quantum leap in conceptualising the first year experience. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 2(1), 51–86. https://altf.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/HERDSARHE2015v02p51-1-1.pdf

- Kift, S., Nelson, K., & Clarke, J. (2010). Transition pedagogy: A third generation approach to FYE - A case study of policy and practice for the higher education sector. The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 1(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.5204/intjfyhe.v1i1.13

- Lacave, C., Molina, A. I., & Cruz Lemus, J. A. (2018). Learning analytics to identify dropout factors of computer science studies through bayesian networks. Behaviour & Information Technology, 37(10–11), 993–1007. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1485053

- Li, I.W., & Carroll, D. R. (2020). Factors influencing dropout and academic performance: An Australian higher education equity perspective. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management, 42(1), 14–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2019.1649993

- Linden, K. (2022). Improving student retention by providing targeted support to university students who do not submit an early assessment item. Student Success, 12(3). https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.2152

- Linden, K., Teakel, S., & Van der Ploeg, N. (2022). Improving student success with online embedded tutor support in first-year subjects: A practice report.

- Meer, J., Scott, S., & Pratt, K. (2018). First semester academic performance: The importance of early indicators of non-engagement. Student Success, 9(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v9i4.652

- Namoun, A., & Alshanqiti, A. (2021). Predicting student performance using data mining and learning analytics techniques: A systematic literature review. Applied Sciences, 11(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11010237

- Nelson, K., Duncan, M., & Clarke, J. (2009). Student success: The identification and support of first year university students at risk of attrition. Studies in Learning Evaluation Innovation and Development, 6(1), 1–15. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/28064/1/c28064.pdf

- Norton, A., Cherastidtham, I., & Mackey, W. (2018). Dropping out: The benefits and costs of trying university (0648230775). Grattan Institute. http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/454571

- OECD. (2021). Education at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/b35a14e5-en

- Schwebel, D.C., Walburn, N. C., Klyce, K., & Jerrolds, K. L. (2012). Efficacy of advising outreach on student retention, academic progress and achievement, and frequency of advising contacts: A longitudinal randomized trial. NACADA Journal, 32(2), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.12930/0271-9517-32.2.36

- Stephenson, B. (2019). Universities must exorcise their ghost students. Times Higher Education, July 30. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/opinion/universities-must-exorcise-their-ghost-students

- Tempelaar, D., Rienties, B., Mittelmeier, J., & Nguyen, Q. (2018). Student profiling in a dispositional learning analytics application using formative assessment. Computers in Human Behavior, 78, 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.08.010

- Tomaszewski, W., Kubler, M., Perales, F., Clague, D., Xiang, N., & Johnstone, M. (2020). Investigating the effects of cumulative factors of disadvantage. University of Queensland. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:2a76ba9

- van der Ploeg, N., Linden, K., Hicks, B., & Gonzalez, P. (2020). Widening the net to reduce the debt: Reducing student debt by increasing identification of completely disengaged students. In S. Gregory, S. Warburton, & M. Parkes (Eds.), ASCILTE’s First Virtual Conference: Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education, Armidale University of New England Virtual Conference 30 November – 1 December 2020, Armidale, (pp. 54–59). https://doi.org/10.14742/ascilite2020.0125

- Yorke, M., & Thomas, L. (2003). Improving the retention of students from lower socio-economic groups. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management, 25(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800305737