ABSTRACT

This article is based on studies carried out within the Young children’s learning research education programme. This undertaking involved five graduate students, all recruited from the Swedish preschool system. The licentiate thesis makes up the final product of their education programme, and the focus of each candidate’s licentiate thesis was preschool-level documentation. Using the results of all five theses, a re-analysis was conducted with the concept of normality as the common starting point. The purpose was to investigate whether documentation and assessment can change the view of normality in preschools, and furthermore, what consequences there may be for preschool activity. ‘The narrow preschool and the wide preschool’ is the model used to support the analysis, which is a model used in previous studies to review and discuss educational choices and conditions in the school system. Results of the present investigation show that the documents and assessments performed in preschool have a strong focus on the individual child and a traditional, school-oriented learning is highly valued. The documentation and assessment practices that take place now in our preschools, therefore, most likely influence the preschool view of normality and restrict the acceptance of differences.

Introduction

The Swedish preschool’s mission has changed over time towards an individualised orientation in terms of goals for both knowledge and democracy (Einarsdottir et al. Citation2015). This trend is evident in the curriculum design, goal formulation and educational activity. The preschool is now a more obvious first step in the educational system covering the ages of one to five years (Vallberg Roth Citation2014). While the demands on the preschool as a learning environment have grown stronger (Palla Citation2011), collective goals have been placed in the background for more individual-nuanced arguments and objectives, which seem to have accentuated the vulnerability of children with poor resources.

The categorisation and selection for special education groups and school forms have increased dramatically in the past decade (Giota and Emanuelsson Citation2011; Karlsudd Citation2012; Nilholm et al. Citation2007). Within school and the after-school leisure programme, the segregated development for children in need of special support is very clear (Karlsudd Citation2012). In the preschool, differentiating into special education groups has been rare; however, given that the three systems have come closer together and are united under the same School Law (Skollagen SFS Citation2010, there is every reason to pay attention that the same development does not gain ground in an educational programme that according to the preschool curriculum (Läroplan för förskolan Lpfö 98 Citation2016, p. 5; Läroplan för förskolan SKOLFS Citation2018, p. 3) is ‘to be adapted to all children in the preschool’.

At the same time as the preschool has been channelled towards a clearer instructional mission, the techniques for documentation and assessment have developed and become more comprehensive in order to make a better visual representation of children’s development. Increased documentation can lead to children being judged in relation to constructed norms and expected knowledge and behaviour. These assessments may limit the scope for children’s differences and reduce opportunities for developing in different ways (Palla Citation2011). Despite the aim for education to be only about development and learning, there will also be a normalising effect (Dolk Citation2013). Thus, it may be interesting and important to reflect on the consequences that an accentuated documentation and assessment practice can have for children’s possibilities to be different in preschool. The children who are often covered by the concept of differences in preschool activities are the children who are described as ‘children in need of special support’. Many times, it is children with intellectual or physical disabilities. The present study centres on normalisation, where the preschool documentation and assessment practices are analysed through the results of five licentiate theses. A licentiate is a degree below that of a PhD given by universities in some countries. It is a 120-point education at the advanced level equivalent to half a doctoral degree. All authors of the licentiate dissertations analysed in this study were experienced preschool teachers. Here answers are sought to questions about how documentation and assessment can affect the view of normality in the preschool practice and what consequences might arise for the future preschool.

Previous research

Documentation is one of the main assignments related to preschool education in Sweden. This is partly because it is introduced in the national curriculum and because of strong influences from Reggio Emilia pedagogy with its focus on pedagogical documentation. The traditional preschool documentation has always been a well-established aspect of preschool and differs in some ways from Reggio Emilia documentation (Emilson and Pramling Samuelsson Citation2014). The main features of traditional preschool documentation are observation, written documentation, evaluation and planning. Pedagogical documentation differs from traditional documentation because it is used as a catalyst for reflection, which makes it possible for teachers, children and parents to discuss, interpret and reflect on the impact of learning and thinking from different perspectives (Dahlberg, Moss, and Pence Citation1999; Lenz Taguchi Citation2013; Rinaldi Citation2006). Documentation and assessment reported in previous research deal mostly with individual development plans and pedagogic documentation. The emphasis is on the perspective of educational science and pedagogy, with learning, development and support for preschool quality control being dominant. There are fewer studies dealing with documentation and assessment from a norm-critical perspective (Vallberg Roth Citation2015).

Today preschool teachers have great confidence that documentation helps them in their pedagogical work and that it can be a way to recognise early and aid resource-weak children (Vallberg Roth Citation2010). Research also shows that preschool teachers see documentation as a tool for professionalisation and as a support for carrying out their tasks based on given directives (Vallberg Roth Citation2015). That pedagogical documentation can support teachers in their professional development and make them aware of their own competence has been confirmed in surveys outside Sweden (de Sousa Citation2019; Löfgren Citation2017; Sheridan, Williams, and Sandberg Citation2013). The majority of documentation and assessment tools are commonly seen as resources for supporting and developing children’s skills. Internationally, preschool curricula are more measurement – and performance-oriented than in Sweden. An example of this is Australia, which, like many other Anglo-Saxon countries, has a clear school-oriented focus when it comes to preschool documentation and assessment practice (Davies Citation2018; Lee Hammond and Bjervås Citation2020).

Research on pedagogic documentation is mainly from the teacher’s perspective. Teachers see advantages for both the children and themselves, but also acknowledge difficulties in managing the process and results (Emilson and Pramling Samuelsson Citation2014). An example of an advantage that has been expressed is that children’s learning processes become more concrete for both teachers and children (Bjervås Citation2011; Buldu Citation2010; Guidici, Rinaldi, and Barchi Citation2001).

One of the disadvantages is that teachers find it inconvenient to document and teach at the same time. Teachers may have difficulty in interacting with the children while simultaneously documenting. Thus, there is a risk that the tool creates distance between the teacher and the child (a.a.). The children are being observed, while the adults are the observers (Sparrman and Lindgren Citation2010). Children are documented and judged by adults, or with exception, by other children, but are not given an opportunity to decline being documented or to reflect on their being documented (Lindgren Citation2016).

Policy documents point out that it is not the children, but rather the preschool activity that is to be assessed. This is an ambition or goal that does not gain much impact. Documentation carried out in the preschool is more directed toward showing what the children learn, unlike previous documentation which showed the activity itself. Several studies involve attention to and visibility of children and their competencies (Lindgren Citation2012; Palla Citation2011; Sparrman and Lindgren Citation2010; Vallberg Roth Citation2009). Assessments are often done based on developmental psychology, and development and learning are expected to follow the same steps for all children. Several of the documentation tools used contain achievement goals and focus on deficiencies.

Consequently, assessment and control features make up part of the preschool documentation practice and are seen as a means of supporting and developing children’s competencies. Studies of the individual child in preschool show that the judgements are expressed in performance-oriented, person-centered and integrity-violating terms (Vallberg Roth Citation2009). Assessments of children can have an impact on identity-creating processes, and this, in turn, can affect how children deal with handling spoken and unspoken expectations of their knowledge and behaviour (Palla Citation2011). In terms of the function of developmental assessments, there are arguments for taking distance from categorising and diagnosing children, as doing so can contribute to establishing boundaries between normality and deviance (Lutz Citation2006). The risk with developmental assessments and diagnoses at an age when children’s perceptions of themselves are being founded, may be that a child is socialised into a deviant role (a.a.).

As previously mentioned, pedagogic documentation has been found to be associated with some reservations (Alnervik Citation2013; Bjervås Citation2011; Buldu Citation2010; Elfström Citation2013; Emilson and Pramling Samuelsson Citation2014). Documentation tasks are time-consuming, and it is important to consider what might be overlooked while the educators are occupied with it. Documentation activity can also be considered a risky occasion as it can disturb children in what they are currently doing (Bjervås Citation2011).

Despite the advantages of early awareness and support for resource-weak children, there seems to be some ambivalence toward documentation. Viewpoints regarding the ways in which documentation and assessment affect children and their behaviour are not entirely consistent, neither is there consensus about the extent to which this practice influences and controls what, and which learning is prioritized and how communication between teacher and child is affected. Another reason for problematising the preschool documentation and assessment practice is the fact that the educators’ statements about the children’s behaviour make up the basis for children being classified as children in need of special support (Lutz Citation2009), despite the fact that individual children should not be assessed in preschool, according to instructions from the National Agency for Education (Skolverket Citation2010; Citation2012). With this background, it is important to study and discuss the influence and complexity of documentation (Kalliala and Pramling Samuelsson Citation2014; Vallberg Roth Citation2015).

One way of approaching these issues is to study the results of the five licentiate theses presented in this investigation which all focus on preschool assessment and documentation practices.

Normality and normalisation

Normality can be linked to clear norm-setting which indicates what is desirable. Normalisation becomes an endeavour to achieve what is considered to be appropriate by the individual being changed in some way (James and Prout Citation2015; Markström Citation2005). Norms have a clear link to power, but they do not happen through coercion, but through people consciously or unconsciously adapting and correcting themselves accordingly (Alasuutari, Markström, and Vallberg-Roth Citation2014). Disciplinary power normalises by forming individuals according to a certain standard. There must be norms for it to be possible to identify deviations from them. When these norms are established, people are generally encouraged to adapt through observation and documentation (Briscoe Citation2008). If individuals are not judged to be normal, then they can be shaped by engineered activities so that they will become like the established norm (Dahlberg, Moss, and Pence Citation2014; Schulz Citation2015).

Tideman (Citation2004) describes normality from three standpoints; statistical normality is when normality is assessed based on the mean and standard deviation in terms of a normal distribution curve. Normative normality is based on prevailing values that exist in a system or a society at a certain point in time. Individual or medical normality means that an individual is normal if he or she is healthy and not sick or abnormal in some other way. The view that is grounded in statistical thinking clarifies what the average is, and then normalisation can involve people, who are considered to be lacking in something, having that added in order to be like the average as much as possible (Markström Citation2005). This view, of course, limits children’s possibilities to be different.

Through developmental psychology and evaluations of development, a child-centred pedagogy has emerged in the preschool, where the child becomes the object of normalisation (Dahlberg, Moss, and Pence Citation2014). Since the 1900s, several theories about children’s learning, development and socialisation have emphasised the interplay or interaction between children and their surroundings. This view of interaction is also one of the dominant discourses in the Swedish policy documents. Despite this, children’s psychological world and social background as well as what is considered typical for a child and what a child is incapable of, are to a large extent the focus. These are the basic ideas that seem to be natural and dominant among educators. Children become the object of observations, and the created development plans and remedial programmes are directed towards children with the goal of children changing and adapting (Löfgren Citation2017; Nordin-Hultman Citation2004; Sparrman and Lindgren Citation2010). Thus, in order to get knowledge about the child, it has been common to observe and rate the child based on different categories grounded in developmental psychology (Esser Citation2015; Palla Citation2011). Stage-based and age-specific explanatory models of children’s development appear to have gained a strong foothold in the preschool. Behaviour is observed on the basis of norms grounded in theoretical constructions of children’s development linked to age and stages. In this way, normality and deviance are created. There are expectations linked to children’s ages regarding how far in development they should have come. The idea of development creates a truth that excludes other ways of looking at a child (Lutz Citation2009).

Normality and deviance are created in the interaction in a given context, and thus normality becomes a relative concept (Markström Citation2005). This means that what is perceived as deviant or normal is seen as constructed in a context with its traditions, customs and norms. Normal or deviant is connected to what is expected, desirable or sought after in each context, which means that these are not given states. The boundaries for what a normal preschool child should look like are different depending on the child’s age, gender or situation. This means that there is a notion of an average child which is dependent on the context.

A relevant question is, what happens to the children who do not meet the normative expectations? Palla (Citation2011) writes that the behaviour that differs from children’s ‘ordinary’ way of being creates confusion, worry and speculation among staff, children or parents. The author explains that such actions are special, because they break with the normative expectations of how children should behave. What is considered special and thereby norm-breaking, stands in relation to the demands, expectations, hopes and ideas that exist in preschool. Thus, the preschool becomes a social institution with the power to decide who should be considered special. In recent times, the assessment of children’s individual development has grown significantly in the preschool practice. An obvious risk with this is the encouragement of normalising practices (Lutz Citation2009).

When preschool staff define a child as a child in need of special support, they identify children with whom they themselves have difficulty interacting (Sandberg et al. Citation2010). Children who do not meet the preschool teachers’ expectations most likely require more from them, and the consequence is that these children are identified by the staff as children in need of special support. When a child shows deviant behaviour, the diagnosis can serve as a relief for both children and educators as well as offer the child an identity where he or she can be understood through his or her diagnosis. Diagnoses can also function as a reassurance for the setting that the problem is with the child, and also as a way to open doors for obtaining resources. Children diagnosed by a doctor are children who receive the most support measures. Children assessed by educators only, and who are not under review, receive support to a much lesser extent (Lutz Citation2009). It is also common that educators speculate in terms of diagnoses, which Karlsudd (Citation2014) calls the ‘undiagnosed diagnosis’.

Preschool staff are expected to operate the preschool so that it includes all children. They should direct and guide toward common values, while at the same time strive for the children to develop specific competencies. The staff’s mission thereby becomes to homogenise at the same time as they should open up for heterogeneity. If the techniques for controlling, categorising and regulating are the most prominent in the preschool operation, then it is likely that homogenisation is going to dominate.

Analysis model

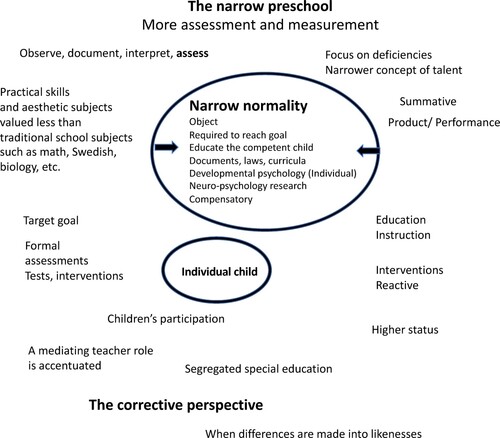

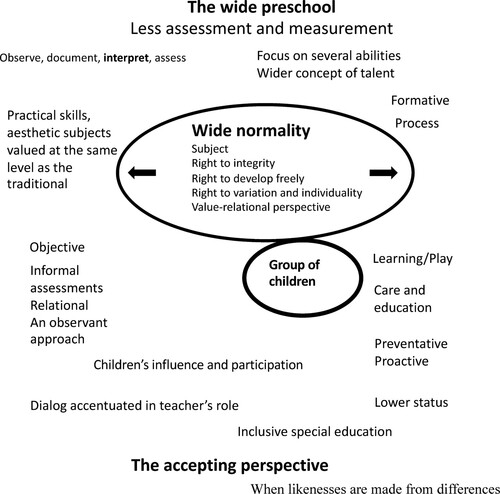

In previous investigations where the prerequisites for being included in the school system were studied, a conceptual analysis model based on results and conclusions was constructed and developed (Karlsudd Citation2002, Citation2007). The model can be seen dichotomous in its construction, and presents two orientations for pedagogical efforts; these two directions in turn have consequences for the view of normality and thus affect the conditions for inclusion.

The first orientation, denoted as ‘narrow’, has as its primary goal to work toward the child/pupil fitting into the activity through corrective and compensatory measures. The second orientation, which is ‘wide’, works foremost to adapt the environment to the child/pupil. The preschools have previously been able to interpret and design their activities relatively independently and freely. Later directives from the responsible authorities have accentuated an approach to the narrow orientation (Emilson and Pramling Samuelsson Citation2014; Palla Citation2011). The analysis model has been tried and developed since its inception and is now being tested to analyse the pedagogical bases that may be valid for the preschool system. Since over the recent decade the preschool has neared the school system, the central concepts contained in the model should be interesting to study and discuss also for this form of education.

The narrow preschool

In the narrow preschool (), the individual child’s performance is central. In order to make this visible and to develop it, there are the key terms: documentation, measurement and assessment. It is the individual child’s performance that is most important, and the knowledge and skills most highly valued are related to those that can be defined as traditional school subjects, such as, Swedish, mathematics, science and technology. In the narrow perspective, the concept of teaching dominates where the teacher has a clear role as an intermediary. In the narrow preschool, the focus is on the deficiencies in relation to the target achievement goals that have been formulated. Compensation and correction are directed more to the child than to the environment and the teacher’s approach. Working with values such as democracy, empathy, and solidarity are more in the background than in the foreground. Children’s influence and involvement are less than in the wide preschool and can be defined as participation. The narrow preschool often holds high status in the education system.

The narrow preschool can contribute to children/pupils, who do not meet the requirements for the desired norm, being regarded as deviant. In a system where normality is narrow, there are greater risks of discrimination and stigmatisation. A narrow interpretation of normality, among other things, can mean that individuals with disabilities fall outside what is considered normal. Many times, the narrow pedagogical orientation is concentrated on difficulties and deviations, with focus on compensation, methods and skills (Karlsudd Citation2011, Citation2015, Citation2017). The compensatory measures aim to adapt the child to the preschool environment. An education that has a strong foundation in the narrow pedagogy reduces children’s opportunities to be different.

The wide preschool

In the wide preschool (), the children’s group and the process are at the centre. Here, assessment is toned down, and it is described often as an interpretation where formative activities are directed toward the environment and pedagogical approaches. The overall abilities of the children’s group are what is most important, and there is a greater breadth of knowledge and skills that are valued. Here, aesthetic subjects and practical skills have more space than in the narrow preschool. In the wide preschool, the concept of learning dominates, and dialogue is at the centre for the teacher. Learning through play is encouraged, and care and education are prioritised. In the wide preschool, a greater acceptance of difference is found, and compensation and correction are directed more towards the environment and to the teacher’s approach than to the child. Working with values such as democracy, empathy and solidarity are at the forefront. A value-relational approach (Willén, Lundgren & Karlsudd, Citation2013) is accentuated in the wide perspective. Children’s influence and participation are genuine, in activities where the objectives act as guidelines. The wide preschool often has a lower status than the narrow preschool status.

In the wide preschool, children are seen as subjects with greater possibilities to develop freely. The pedagogical efforts have more of a proactive character. An education that has a strong foothold in the wide preschool reduces segregating measures and increases children’s opportunities to be different. Here, the principal, as pedagogical leader and head of staff, has the overall responsibility to plan, follow up, evaluate and develop the activities systematically, continuously and thereby work for increased goal fulfillment. In the above models, the school activities have been the basis for concepts and differentiations. In the following report of results and analysis, the models will be tested against the preschool context.

The design and implementation of the study

Aim

This study focuses on normalisation, where documentation and assessment practices are analysed through the results of five licentiate theses. The models of the narrow preschool and the wide preschool are used to support the analysis.

The precise research questions are formulated as follows:

How can documentation and assessment, as active documents, affect the view of normality in the preschool operation?

What consequences does the documentation have for the preschool practice?

Empirical basis of the study

The research programme Young children’s learning, carried out during the years 2015–2018, was initiated and financed by 12 municipalities located in south and central Sweden.

The five licentiate theses that constituted the final documentation had a qualitative approach where all the projects underwent a local ethical vetting (Swedish Research Council Vetenskapsrådet Citation2017). The projects which included direct contact with children and where the researcher was present in the activity were particularly reviewed by a national ethics committee.

Below follows a summary of the investigations that were carried out in the project and that are now re-analysed with a focus on normality. One investigation had the goal of making visible the values that appear in the systematic quality control of the preschool (Davidsson Citation2018). The investigation is based on the annual evaluations of 17 preschools. In total, the empirical material consists of 192 pages of documentation, encompassing 72,427 words. In the thesis, discourse theories and critical discourse analysis are used (Fairclough Citation1992). In the evaluations, competence is strongly emphasised, especially abilities, development and learning. To a large extent, knowledge capabilities, such as language, mathematics and science appear to be sought after. Also, democracy and ethics are given as valuable elements of the preschool programme. The emphasis on ethical values is placed on care and security. The thesis author says that the preschool programme has gone from the rationale of developmental psychology to being more goal-oriented. For preschool children, this change can mean that the concepts of competence and cognition are accentuated, and thereby other values become less visible in the programme (Davidsson Citation2018).

Lindberg (Citation2018) studied documentation produced and made public in the preschool. By studying the documentation that was set up on the walls and/or in the children’s folders, the preschool’s performative documentation practice became visible. The data collection was carried out at three preschools in three different municipalities. There were altogether 9 preschool units, and the data material consisted of 441 documents of varying scope, ranging from a half page to 47 full pages. The more comprehensive documentation was project documentation accompanying a longer project.

The theories used in the theses are Lyotard’s (Citation1984) and Ball’s (Citation2003) theories on performativity. In the presentation of results, the author has divided the documentation into process and product documentation. In the first category of process documentation, the educators place emphasis on following the learning process. In the product documentation, the focus is on the end results. The findings reveal an even distribution between process (46%) and product documentation (54%). There exists a greater proportion of documentation that focuses on the individual (86%) compared with the group (14%). Of the 441 documents studied, 317 (72%) focus mainly on learning and knowledge, either as something shown by the children or as something the educators teach. This indicates that documentation displaying learning and knowledge is valued most and that the educators work toward goals that are easy to measure, for example, children’s ability to sort. The majority of the documentation shows an individual child’s learning, knowledge and abilities. What appears as important in the documentation is to show that the children have knowledge and skills related to the curriculum goals or knowledge about what the educators have taught. The documentation becomes a way for the educators to assess a child’s, or more seldom the group of children’s, knowledge and skills. In some cases, comparisons are also made between children’s abilities.

The documentation is linked to subject learning, such as mathematics, science and language. Educators’ assessment documents focus almost exclusively on a child’s performance and not on their own or other educators’ performance. There are few examples of the stepwise development of a group of children. In a broader perspective, it can be said that the overall documentation to a large extent aims to give a positive picture of the preschool (Lindberg Citation2018).

The overall purpose of Lindroths study (Citation2018) was to study pedagogic documentation in relation to children’s participation. Focus is directed partly toward the teacher’s actions in connection with producing documentation during a project and partly toward the teachers’ descriptions of their intentions with the documentation situation. The teachers’ actions were studied, and for this purpose, video observation and stimulated recall were chosen methods. The study focuses on adult-initiated projects at two preschools that work with pedagogic documentation. The projects were filmed on three occasions at each preschool. The sessions ranged from 28 min to just over 40 min. The theory reflecting the results is Habermas’s communicative action theory (Habermas Citation1990). The documentation was produced for the purpose of making visible a certain activity content. The teachers’ expressed intention was that children’s interests should have importance for the design of the activity. A conclusion in the investigation is that working with pedagogic documentation in projects contains two parallel tracks of participation. Through the documentation, a fabricated participation comes to light, at the same time as real participation occurs in situations that are not the target of documentation.

Teachers’ actions in connection with producing documentation stand out as more strategic than their other actions, which means that the work with pedagogic documentation can be understood as a pseudo-activity that limits participation rather than contributing to increasing it. Therefore, a conclusion is that children’s participation in projects can be made visible though it does not exist, while at the same time, participation can also be found to exist though it is not made visible. The strategic actions that happen before, during and after the production of documentation help make the participation visible regardless whether the children have participated or not. At the outset, pedagogic documentation seems to have the main task of showing a prepared, pre-written story about the activity taking place in preschool (Lindroth Citation2018).

Nilfyr (Citation2018) studied the everyday documentation and assessment practices in preschool using video-observations. The data collection process consisted of video-observations conducted at two preschools. During a total of five weeks of fieldwork, situations containing some form of documentation, in which there also occurred interaction between the educators and children, were filmed. In total, 7 educators and 35 children, between three and six years old, took part in the study. The focus is on the situations in which educators and/or children carry out some form of documentation and at the same time interaction occurs between the children and educator. The thesis uses Goffman’s sociological interaction theory (Goffman, [Citation1974] Citation1986). Study findings show that the educator has a clear goal with the activities, and it seems overall that the goal of the activity becomes the actual result. In three of the four situations described, the educator steers the situation through a series of questions in the direction desired by the teacher.

The preschool teachers are task-driven and goal-oriented, and by speaking in questions, they try to get the children to share the definition of the situation they have set. What characterises all situations is also that educators consistently happen to have a predetermined and expected result of the activity. The adaptation of the educators and children can be seen as an attempt to keep the institutional design of the preschool intact, which is a preschool characterised by a strong orientation toward learning within specific areas and a documentation that applies to both activities and individual children, which, in turn, should guarantee the quality in the preschool (Nilfyr Citation2018).

The preschool teachers’ joint conversations about documentation and assessment in preschool were studied by Virtanen (Citation2018). By using focus groups, the preschool teachers’ discussions about the current documentation and assessment practices were transcribed. In the thesis, Fairclough’s (Citation1992) discourse theories were used as the basis for analysis and discussion. The preschool teachers in the study made use of different ways of legitimising documentation in the preschool. The preschool teachers particularly use objective arguments with high modality (strong emphasis) when referring to the curriculum for the preschool (National Agency for Education Skolverket Citation2010) and support material from the National Agency for Education (2012). Preschool teachers also speak in a strong, objective manner when they talk about how documentation is the way to raise the reputation of the preschool and the profession. This argument also appears when the preschool teachers talk about how documentation benefits children’s development. The preschool teachers in the study show how the use of the term assessment in the preschool is both necessary and desirable. Use of correct concepts is considered to raise the profession’s status. A positive interpretation of the meaning of the term assessment makes it possible to speak about it in preschool. The positive interpretation means that assessment leads to children being challenged in their learning. The preschool teachers say assessment of the individual child is something undesirable at the same time as they think it is something they must do. They condemn the assessment of individual children using support from different researchers in the scientific field that state children’s self-esteem is hurt by assessment. That preschool teachers must assess the children is legitimised by the preschool teachers saying that assessment helps children. The child should not be aware of the deficiencies or weaknesses that preschool teachers have seen, and the interventions should occur collectively (Virtanen Citation2018).

Re-analysis and discussion

The results of the five studies strengthen many parts of the picture of results from previous research. It becomes very clear that documentation has a strong focus on the individual child where a traditional, school-oriented learning is highly valued (Davidsson Citation2018; Lindberg Citation2018; Lindroth, Citation2018; Nilfyr Citation2018; Virtanen Citation2018). The results are in good agreement with the narrow preschool perspective. The documentation emphasises education and instruction mostly in subjects such as mathematics, science and language. Assessments and comparisons are common, which disqualifies this part of the results from being placed in the wide preschool. Many times what are referred to as soft skills, for example, social and ethical actions, which are particularly emphasised in the wide preschool, are clearly under-represented.

In the narrow perspective, laws and curricula are central and are strictly interpreted, and this is something that agrees with the preschool teachers’ talk about documentation and assessment practices. Many preschool teachers highly value the curriculum, particularly the parts that deal with the teaching task, which is expected to raise the status of the preschool and the profession (Virtanen Citation2018).

Many preschool teachers have a divided attitude toward assessment. On the one hand, it is argued that assessment can lead to the child being challenged in his or her learning, but on the other, one is also aware that it can hurt a child’s self-esteem. This contradictory argument is strongly represented when the preschool teachers speak about documentation and assessment in Virtanen’s (Citation2018) thesis. Returning to the previous discussion on normativity, documentation as a concept and activity is accepted by the preschool teachers. That all observation and documentation are judgmental to different degrees is known, but the clearer and the more formalised, and in certain cases the more categorising, then the greater the ambivalence is towards the concept. Assessment is a troublesome element, which in its formalised and clear form disturbs many preschool teachers’ basic pedagogical view.

In the investigation that examined evaluations (Davidsson Citation2018) of systematic quality control, cognitive skills, competence and performance were highlighted, which are findings that agree well with the four other investigations. One difference is that the concepts of democracy, ethics and care were included, though to a lesser extent (a.a.). One reason why these values become clearer, in comparison with other investigations, may be that Davidsson’s empirical data reflect the preschool programme over a year and probably the evaluation was conducted more systematically based on all parts of the curriculum. In the same evaluations, the preschool staff’s actions are more clearly visible, which is not the case in the documentation studied by Lindberg (Citation2018).

That a goal-oriented discourse (Davidsson Citation2018) dominates becomes evident in the preschool teachers’ steering and control during documentation situations (Nilfyr Citation2018). Here the children’s spontaneous discoveries and initiatives are diminished, which also becomes apparent in the observations reported by Lindroth (2017). This is behaviour that can be put in the narrow preschool.

A mutual acceptance of the documentation and assessment culture is noticeable from both children and preschool teachers (Lindroth, 2017; Nilfyr Citation2018). This is despite the fact that preschool teachers, as reported in Lindroth’s study, realise that documenting is not necessarily most central to the activity. Learning within a narrow framework is in focus. Lindroth’s (2017) study also highlights children’s limited influence and participation. Here the narrow preschool’s concept of participation is a more adequate description. The exception is the case when children themselves take the initiative for documentation, which does not happen to the same extent, but is a good example of what the wide preschool advocates.

It becomes clear that the preschool teachers take a shortcut in the prescribed documentation. It is the group of children who should be at the centre, but despite this, the object for documentation for the most part is the individual child (Lindberg Citation2018). The consequence of this is that the narrow preschool approach is further strengthened.

The results in the five studies show clearly that the elements of narrow pedagogy are over-represented in activities that are characterised by documentation and assessment. All the authors discuss whether this approach is more a concession given the demands set with an instructional orientation. Care and socialisation with concepts such as, solidarity, friendship and collaboration, do not have the same place in the picture shown in the documentation and assessment practice that was investigated. Much that is documented, evaluated, assessed and discussed is linked to the narrow and corrective preschool. That naturally has effects for what is considered normal and deviant. The desired/desirable and the not desired/undesirable become clear. The framework that encompasses the normality concept becomes smaller, and expectations and demands become clear for both children and parents. The threshold for when a child is considered a child in need of special support is shifted toward new, narrower conditions, and it becomes easier to motivate special education interventions with the risk of making distinctions.

The desire to make visible a positive image of the preschool, which supports the curriculum’s education-oriented profile, is evident in the five investigations. The performative orientation dominates. A decade ago, care values were explicit in the preschool documentation efforts (Einarsdottir et al. Citation2015) and what concerned learning was more implicit and for some preschool teachers unclear. Before the development of the curriculum toward more instruction and knowledge, that which distinguished wide pedagogy was more distinct in documentation and policy documents. Now it is less visible, but its importance makes up probably a significant part of the preschool teachers’ approach and actions. It is possible that what was previously implicit (learning) has changed places with what was previously explicit (care).

The lack of a child’s perspective in research on documentation and assessment is highlighted by many researchers. The children’s own voices are not heard, not either in the five investigations that have now been analysed. One reason for this may be that it is considered too complicated and ethically sensitive to carry out such research studies. To implement documentation routines that make children objects, without properly finding out clearly how this affects children, is likely to be more unethical. Perhaps the preschool activity, with the same documentation methods, could focus to a greater extent on the staff and allow the children to conduct the analysis.

Many times it is emphasised that assessment is part of all communication, and, therefore, it is a natural feature of preschool. That is a simple argument to legitimize a documentation and assessment culture where developmental assessments take up considerable space. There is a difference in how and with what intent assessment is done. The documentation and assessment that is taking place now influences our view of normality and limits the possibility to meet with differences.

The preschool has a many-sided mission, in which the activity should be adapted to all children while at the same time striving to impart common values. This is naturally a pedagogical challenge, but if the common values, the sought-after, are dominated by cognitive skills, this task becomes impossible. If we are to include all members in an equal community, we must see skills and abilities in another way than what is most prominent today. An important question is how a strong sense of belonging can be secured among children in the preschool. Most likely this type of assessment is significantly more important than measuring knowledge-oriented performance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Peter Karlsudd

Peter Karlsudd My research interests are centred on the fields of special needs education, flexible learning and teaching and learning in higher education. Regarding special needs education I have always been particularly interested in inclusive teaching methods, especially with children and young people with intellectual disabilities. I took my doctorate in education at Lund University in 1999 with the thesis entitled ‘Children with intellectual disability in the integrated school-age care system’. I finished my doctoral thesis in informatics, ‘Support for learning? Possibilities and obstacles in learning applications’.

References

- Alasuutari, M., A. M. Markström, and A. C. Vallberg-Roth. 2014. Assessment and Documentation in Early Childhood Education. London: Routledge.

- Alnervik, K. 2013. “Men så kan man ju också tänka”: Pedagogisk dokumentation som förändringsverktyg i förskolan [“But so One Can Also Think”: Pedagogic Documentation as a Tool for Change in Preschool] Doktorsavhandling. Jönköping: Högskolan i Jönköping.

- Ball, S. J. 2003. “The Teacher’s Soul and the Terrors of Performativity.” Journal of Education Policy 18 (2): 215–228.

- Bjervås, L. 2011. Samtal om barn och pedagogisk dokumentation som bedömningspraktik i förskolan: en diskursanalys [Conversations About Children and Pedagogic Documentation as Assessment Practice in Preschool: A Discourse Analysis]. Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis.

- Briscoe, P. 2008. From the Work of Foucault: A Discussion of Power and Normalization in Schooling: Candidacy Exam, Graduate Division of Educational Research Educational Leadership Program. Calgary: University of Calgary.

- Buldu, M. 2010. “Making Learning Visible in Kindergarten Classrooms: Pedagogical Documentation as a Formative Assessment Technique.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (7): 1439–1449.

- Dahlberg, G., P. Moss, and A. R. Pence. 1999. Beyond Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care: Postmodern Perspectives. Hove: Psychology Press.

- Dahlberg, G., P. Moss, and A. Pence. 2014. Från kvalitet till meningsskapande: postmoderna perspektiv - exemplet förskolan [From Quality to Meaning Creation: Post-Modern Perspectives – the Preschool Example]. 3. Uppl. Stockholm: Liber.

- Davidsson, M. 2018. Värdeladdade utvärderingar: En diskursanalys av förskolors systematiska kvalitetsarbete [Value-Laden Evaluations: A Discourse Analysis of Preschool Systematic Quality Control] (Lnu Licentiate; 14). Kalmar: Linnaeus University Press.

- Davies, J. 2018. “Pedagogies of educational transition: Educator networks enhancing children’s transition to school in rural areas.” PhD Thesis, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, NSW, Australia.

- de Sousa, J. 2019. “Pedagogical Documentation: The Search for Children’s Voice and Agency.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 27 (3): 371–384.

- Dolk, K. 2013. “Bångstyriga barn: makt, normer och delaktighet i förskolan [Angry Children: Power, Norms and Participation in Preschool].” Diss., Stockholm: Stockholms universitet, 2013.

- Einarsdottir, J., A.-M. Purola, E. Johansson, S. Broström, and A. Emilson. 2015. “Democracy, Caring and Competence: Values Perspectives in ECEC Curricula in the Nordic Countries.” International Journal of Early Years Education 23 (1): 97–114.

- Elfström, I. 2013. Uppföljning och utvärdering för förändring – pedagogisk dokumentation som grund för kontinuerlig verksamhetsutveckling och systematisk kvalitetsarbete i förskolan [Follow-up and Evaluation for Change – Pedagogic Documentation as the Basis for Continuous Program Development and Systematic Quality Control in Preschool]. Doktorsavhandling. Stockholm: Stockholms universitet.

- Emilson, A., and I. Pramling Samuelsson. 2014. “Documentation and Communication in Swedish Preschools.” Early Years: An International Research Journal 34 (2): 175–187.

- Esser, F. 2015. “Fabricating the Developing Child in Institutions of Education: A Historical Approach to Documentation.” Children & Society 29: 174–183.

- Fairclough, N. 1992. Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity press.

- Giota, J., and I. Emanuelsson. 2011. Specialpedagogiskt stöd, till vem och hur? Rektorers hantering av policyfrågor kring stödet i kommunala och fristående skolor [Special Education Support, to Whom and How? Principals’ Management of Policy Issues Regarding Support to Municipal and Independent Schools]. RIPS nr 2011:1. Göteborg: Göteborgs universitet, Institutionen för pedagogik och specialpedagogik.

- Goffman, E. (1974) 1986. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press.

- Guidici, C., C. Rinaldi, and P. Barchi. 2001. Making Learning Visible: Children as Individual and Group Learners. Cambridge, MA: Project Zero, Harvard Graduate School of Education.

- Habermas, J. 1990. Kommunikativt handlande. Texter om språk, rationalitet och samhälle [Communicative Behavior. Texts About Language, Rationality and Society]. Göteborg: Daidalos.

- James, A., and A. Prout. 2015. Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood. Contemporary Issues in the Sociological Study of Childhood. New York: Routledge.

- Kalliala, M., and I. Pramling Samuelsson. 2014. “Pedagogical Documentation.” Early Years: An International Research Journal 34 (2): 116–118.

- Karlsudd, P. 2002. Tillsammans. Integreringens möjligheter och villkor [Together: Integration Possibilities and Conditions]. Kalmar: Högskolan i Kalmar.

- Karlsudd, P. 2007. “The ‘Narrow’ and the ‘Wide’ Activity: The Circumstances of Integration.” The International Journal of Disability, Community & Rehabilitation 6: 1.

- Karlsudd, P. 2011. Sortering och diskriminering eller inkludering [Sorting and discrimination or inclusion]. Specialpedagogiska rapporter och notiser från Högskolan Kristianstad, Nr 6. Kristianstad.

- Karlsudd, P. 2012. “School-age Care, an Ideological Contradiction.” Problems of Education in the 21st Century 48: 45–51.

- Karlsudd, P. 2014. “Diagnostisering och kompensatoriska hjälpmedel, inkluderande eller exkluderande [Diagnostics and Compensatory Learning Aids, Inclusive or Exclusive] Debatt.” . Pedagogisk Forskning i Sverige 19: 223–228.

- Karlsudd, P. 2015. “Inkluderande individualisering [Inclusive Individualization].” Specialpædagogik 35: 24–36.

- Karlsudd, P. I. 2017. “The Search for Successful Inclusion.” Disability, CBR & Inclusive Development 28: 142–160.

- Lee Hammond, L., and L. Bjervås. 2020. “Pedagogical Documentation and Systematic Quality Work in Early Childhood: Comparing Practices in Western Australia and Sweden.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 1–15.

- Lenz Taguchi, H. 2013. Varför pedagogisk dokumentation? Verktyg för lärande och förändring i förskolan och skolan [Why Educational Documentation? Tools for Learning and Change in Preschool and School]. 2nd ed. Malmö: Gleerups.

- Lindberg, R. 2018. Att synliggöra det förväntade: förskolans dokumentation i en performativ kultur [Making Visible the Expected: Preschool Documentation in a Performative Culture] (Lnu Licentiate; 22). Linnaeus University Press.

- Lindgren, A.-L. 2012. “Ethical Issues in Pedagogical Documentation: Representations of Children Through Digital Technology.” International Journal of Early Childhood 44 (3): 327–340.

- Lindgren, A.-L. 2016. Etik, integritet och dokumentation i förskolan [Ethics, Integrity and Documentation in Preschool]. Malmö: Gleerups.

- Lindroth, F. 2018. Pedagogisk dokumentation – en pseudoverksamhet? Lärares arbete med dokumentation i relation till barns delaktighet [Pedagogic Documentation – A Pseudo-Activity? Teachers’ Use of Documentation in Relation to Children’s Participation]. (Lnu Licentiate; 8). Linnaeus University Press.

- Löfgren, H. 2017. “Learning in Preschool: Teachers’ Talk About Their Work with Documentation in Swedish Preschools.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 15 (2): 130–143.

- Läroplan för förskolan [Preschool curriculum] Lpfö 98. 2016. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Läroplan för förskolan [Preschool curriculum]. SKOLFS. 2018. 50 Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Lutz, K. 2006. Konstruktionen av det avvikande förskolebarnet – En kritisk fallstudie angående utvecklingsbedömningar av yngre barn [Construction of the Deviant Preschool Child – A Critical Case Study of Developmental Assessments of Younger Children]. Licentiatuppsats. Malmö: Malmö högskola.

- Lutz, K. 2009. “Kategoriseringar av barn i förskoleåldern: styrning & administrativa processer [Categorization of Children in Preschool Age: Control & Administrative Processes].” Diss., Lund: Lunds universitet, 2009.

- Lyotard, F. 1984. The Postmodern Condition – A Report on Knowledge. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Markström, A.-M. 2005. “Förskolan som normaliseringspraktik: en etnografisk studie [Preschool as a Normalization Practice: An Ethnographic Study].” Diss., Linköping: Linköpings universitet.

- Nilfyr, K. 2018. Dokumentationssyndromet: En interaktionistisk och socialkritisk studie av förskolans dokumentations-och bedömningspraktik [Documentation syndrome: An interactionist and social critical study of preschool documentation and assessment practice]. (Lnu Licentiate; 11). Linnaeus University Press.

- Nilholm, C., B. Persson, M. Hjerm, and S. Runesson. 2007. Kommuners arbete med elever i behov av särskilt stöd – En enkätundersökning [Municipalities work with children in need of special support – A survey study]. INSIKT 2007:2. Vetenskapliga rapporter från Högskolan för lärande och kommunikation. Högskolan i Jönköping.

- Nordin-Hultman, E. 2004. Pedagogiska miljöer och barns subjektskapande [Educational environments and children’s subject-creation]. Diss. Stockholm: Univ.

- Palla, L. 2011. Med blicken på barnet: om olikheter inom förskolan som diskursiv praktik [With eyes on the child: Differences in preschool as discursive practice]. Diss. Malmö: Lunds universitet.

- Rinaldi, C. 2006. In Dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, Researching and Learning. New York: Routledge.

- Sandberg, A., A. Lillvist, L. Eriksson, E. Björck-Åkesson, and M. Granlund. 2010. ““Special Support” in Preschools in Sweden: Preschool Staff’s Definition of the Construct.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 57 (1): 43–57.

- Schulz, M. 2015. “The Documentation of Children's Learning in Early Childhood Education.” Children & Society 29: 209–218.

- Sheridan, S., P. Williams, and A. Sandberg. 2013. “Systematic Quality Work in Preschool.” International Journal of Early Childhood 45 (1): 123–150.

- Skollagen SFS. 2010. 800. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Skolverket. 2010. Läroplan för förskolan [Preschool Curriculum] Lpfö98 (Rev. Uppl.). Stockholm: Fritzes.

- Skolverket. 2012. Uppföljning, utvärdering och utveckling i förskolan – pedagogisk dokumentation [Follow-up, Evaluation and Development in Preschool – Pedagogic Documentation]. Stockholm: Fritzes.

- Sparrman, A., and A.-L. Lindgren. 2010. “Visual Documentation as a Normalizing Practice: A New Discourse of Visibility in Preschool.” Surveillance & Society 7 (3/4): 248–261.

- Tideman, M. 2004. Lika som andra – om delaktighet som likvärdiga levnadsvillkor [Like Others – Participation as Equal Living Conditions]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Vallberg Roth, A.-C. 2009. Styrning genom bedömning av barn [Control through assessment of children]. EDUCARE 2–3, 195-218. Malmö: Malmö högskola.

- Vallberg Roth, A.-C. 2010. Att stödja och styra barns lärande – tidig bedömning och dokumentation. I: Perspektiv på barndom och barns lärande: en kunskapsöversikt om lärande i förskolan och grundskolans tidigare år [Supporting and Guiding Children’s Learning – Early Assessment and Documentation. In: Perspectives on Childhood and Children’s Learning: a Knowledge Overview of Learning in Preschool and the Compulsory School Earlier Years]. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Vallberg Roth, A.-C. 2014. “Bedömning i förskolors dokumentation – fenomen, begrepp och reglering [Assessment in Preschool Documentation – Phenomena, Concepts and Regulation].” Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige 19 (4–5): 403–434.

- Vallberg Roth, A.-C. 2015. Bedömning och dokumentation i förskolan. Tidig intervention förskola. I Vetenskapsrådets rapporter 2015, Forskning och skola i samverkan – Kartläggning av forskningsresultat med relevans för praktiskt arbete i skolväsendet [Assessment and documentation in preschool. Early intervention preschool. In: Swedish Research Council reports 2015, Research and school in collaboration – Survey of research results with relevance for practice in the school system]. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet och Skolforskningsinstitutet.

- Vetenskapsrådet. 2017. God sed i forskningen [Good Practice in Research]. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet.

- Virtanen, M. 2018. Förskolans dokumentations- och bedömningspraktik: En diskursanalys av förskollärares gemensamma tal om dokumentation och bedömning [Preschool Documentation and Assessment Practice: A Discourse Analysis on Preschool Teachers’ Shared Discussions about Documentation and Assessment]. (Lnu Licentiate; 15). Linnaeus University Press.

- Willén-Lundgren, B., and P. Karlsudd. 2013. “Relationella avtryck och specialpedagogiska perspektiv i fritidshemmets praktik [Relational Impressions and Special Education Perspectives in the After-School Leisure Program].” In Relationell specialpedagogik - i praktik och teori, edited by J. Aspelin, 63–78. Kristianstad: Kristianstad University Press.