Abstract

In East Jerusalem two seemingly antithetical temporal regimes are at work. On the one hand, access to the city is disrupted by time that expands and contracts arbitrarily. This impedes movement, makes even the immediate future difficult to predict, and disconnects many Palestinian residents, particularly those on the outskirts of the city beyond the Separation Wall, from Jerusalem in both the short and the long term. Read as a deliberate ‘deregulation’, temporality thus feeds into Israel’s demographic aims of excluding Palestinians from the city. On the other hand, increased speed, timeliness and synchronisation are used to formalise and normalise Palestinian mobilities, as I show using the case of the Ramallah-Jerusalem Bus Company. This furthers the fifty-year project of Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem by linking and incorporating Palestinian movements into the circulations of the Israeli city. The de/regulation of urban rhythms enabled by this infrastructure of control serves to advance Israeli policy aims in the city by modulating degrees of connection to the city. The article reads this dual regime as reflecting the ambivalent status of Jerusalem’s Palestinian residents, who nonetheless seek to resist and mitigate the effects of both exclusionary and incorporative temporality.

Introduction

East Jerusalem has been under Israeli rule for over fifty years, yet its annexation—enshrined in Israeli law, but not accepted by the international community (Lustick Citation1997)—has never been completed. While the territory of East Jerusalem is considered an integral part of Israel by the government, its Palestinian residents are not citizens of Israel; most are stateless and hold a precarious legal status (Ir Amim Citation2012). A solution to the ‘conflict’ is continuously deferred, and with it, so too are both the prospect of a Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem, and a final determination of which of the numerous borders cutting across the city will become permanent. In this seemingly perpetual state of suspension, quotidian acts of the city’s residents often reverberate into the realm of geopolitics (cf. Yacobi Citation2015). Based on eight months of on-site research between 2013 and 2015, this article examines both how the Israeli occupation regulates Palestinian temporalities, and how Palestinians seek to mitigate and resist the effects of these temporal regimes. It shows how, in lieu of a political solution or agreed-upon borders, the timescapes of mobility serve to control this ambiguous terrain and those inhabiting it through regulating degrees of Palestinian inclusion by way of their everyday urban experience.

The article is concerned with time in (and across) space, and in particular the speed and predictability of movements, as I view mobility as the main arena in which Palestinians experience and shape Jerusalem’s intra-urban boundaries (cf. Baumann Citation2016). Infrastructures, especially those for communication and mobility, have the capacity to shape temporalities by connecting across space (Anand, Gupta, and Appel Citation2018), as well as by instilling a sense of progress (Larkin Citation2013). With the introduction of the railroad and the much-increased speed of movement it enabled globally, the obstacle of distance diminished in importance (Schivelbusch Citation1977). Harvey (Citation1989) describes this process as ‘time–space compression’, a phenomenon he sees as continuously shaping the era of economic globalisation. The acceleration of life has also been understood as a key marker of the urban (Rosa and Scheuermann Citation2009). Clock (or durational) time, is thus deeply entangled with mobility and the infrastructures facilitating it. Physical infrastructure is based on the adoption and operationalisation of shared standards which facilitate interaction (Bowker and Star Citation1999; see also Easterling Citation2014)—a definition which also applies to the immaterial infrastructure of time. The synchronisation of timetables, especially through the railroad, has not only played an essential part in unifying nation-states, but was also a key aspect of colonial projects (i.e. Barak Citation2013; Prasad Citation2013; Ogle Citation2015). Our very notion of standardised time, then, is based on and shaped by infrastructural progress and enhanced mobility—but also on the appropriation and control of land and resources.

Recognising the politics embedded in these processes, Massey argues that we must not only acknowledge the manner in which space and time co-constitute one another (Citation1992) but also attend to the ‘power geometries of space–time compression’ (Citation1994). To her, this question is reflected not merely in who moves, but who is in charge of mobility—while some initiate mobility, others are on its receiving end, and ‘some are effectively imprisoned by it’ (Citation1994, 149). Mobility and transport infrastructure thus appear well-positioned as sites of enquiry for understanding how the power dynamics of time play out in urban space. Affirming Massey’s point, in Israel/Palestine, the smooth movement of Israelis has been interpreted as contingent upon the disruption of Palestinian travel (Handel Citation2014). Studies of the restrictions imposed on Palestinian movement have noted their effects on Palestinian temporality (i.e. Allen Citation2008; Backmann Citation2010; Fieni Citation2014). Several scholars see the Israeli mobility regime as creating two distinct temporalities, one for Palestinians and another for Jewish Israelis, often noting that the two are relational (Weizman Citation2007; Handel Citation2009; Parizot Citation2009; Pullan Citation2013a; Tawil-Souri Citation2017; Peteet Citation2018).

I examine this process in Jerusalem and its immediate hinterlands—focusing in particular on residents whose long-established connection to the city is being undermined. I argue that two distinct temporal regimes are at work in the city, furthering Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem by reinforcing the exclusion of Palestinians from the city—and at the same time forcefully incorporating them. In one regime, outlined in the first section, Palestinian time is deliberately de-regulated, impacting quotidian journeys and commutes, especially those that must pass through checkpoints. The resulting unpredictability and disjunction serve not only to disrupt Palestinian lives and spatio-temporal trajectories, but also to construct Palestinians as irrational subjects. In the second section, I turn to the less-examined and more recent efforts to align Palestinian movements with Israeli mobilities in Jerusalem. By examining the formalisation of the East Jerusalem-Ramallah Bus Company, I show that in Jerusalem, there is also a synchronisation of Palestinian and Israeli rhythms and timetables. In this ‘normalised’ temporal regime in which movement is regulated, sped up, and aligned, time–space compression is associated with progress and modernity but has the effect of increased Israeli control and decreased Palestinian autonomy in the city.

Despite the markedly contrasting everyday experiences of mobility they facilitate, then, the two temporal regimes both serve to undermine a Palestinian future in the city, as the conclusion argues. Time is used to exclude residents from the city through deregulation and simultaneously to incorporate them through temporal regulation of movements. This suggests that it operates like an immaterial infrastructure in that it regulates degrees of connection, access and circulation. The two temporalities therefore form part of one infrastructure of control. The argument put forth contributes to the study of Palestinian mobilities and temporalities under Israeli occupation, which has so far overlooked the incorporative aspects of synchronisation. At the same time, it adds a new dimension to the literature examining the role of infrastructure in urban marginalisation, which has rarely focused on the control exerted through infrastructural exclusion and the violence that can be exerted through infrastructural connection.

Temporal deregulation as control

As early as the closure imposed on the Palestinian territories in the 1990s, and increasingly since the Israeli military checkpoint regime was put in place during the second Intifada (2000–2005), and the Separation Wall built around Jerusalem from 2002 onwards, Palestinian time–space has appeared to follow new rules. A ‘slowing down’ of Palestinian movement (Parizot Citation2009) with longer journeys and waits has increased the sense of distance, causing time–space divergence. In addition, the unpredictability of this time–space makes planning ahead difficult and creates fatigue among those who must counterbalance it. This temporal deregulation creates difficulty in maintaining daily routines and upends life trajectories. It creates social distance, alienating especially those on the outskirts of Jerusalem from the city’s urban life. While many Palestinians seek to mitigate, and even resist, time–space divergence and unpredictability, some reorient their lives away from the city entirely. As this temporal regime of instability feeds into Israeli strategic aims in Jerusalem, it can be understood, following Roy, as a temporal form of ‘deregulation.’ By unravelling the temporal norms governing the lives of Palestinians on the outskirts of the city, the occupation constructs residents as external to the urban order and thus legitimises their gradual exclusion and potential future dispossession.

Time–space divergence and unpredictability

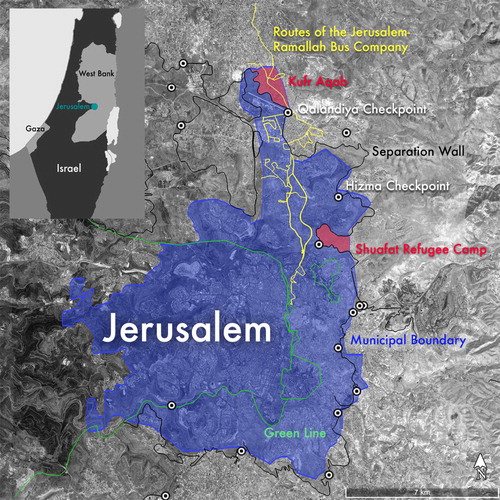

Not only has the Wall severed the city from its hinterlands, but as it cuts through the (Israeli-determined) municipality, it severs parts of East Jerusalem itself from the core of the city, leaving a third of Palestinian Jerusalemites on the ‘wrong’ side (see ).Footnote1 As such, those commuting into central Jerusalem from the exclaves of Kufr Aqab and Shuafat refugee camp like SameerFootnote2 complained of the heavy traffic caused by the bottleneck of the checkpoint, as well as the bad road conditions, which caused waiting times of up to two hours. Distances appeared to increase as journeys became both longer because of detours, and simply more onerous due to the many obstacles imposed by the Israeli restrictions on movement. The sense of Jerusalem being far away, or even unreachable, despite the short topographic distance, was reiterated by numerous interlocutors living on the outskirts of Jerusalem.

Figure 1 Overview of East Jerusalem, the exclaves between Wall and Municipal Boundary and the routes of the Jerusalem-Ramallah Bus Company. Map produced by the author on the basis of Google Earth.

Indeed, for some, as topological distances expanded, so did temporal ones. Abdel Halim, a man in his fifties who had lived in the Jerusalem area for fifteen years, but only recently received an ID enabling him to travel across the West Bank, felt alienated by what he encountered: ‘There are many things that are changed, the streets, the buildings, the people, the habits of the people.’ This lack of familiarity made him feel like ‘a complete stranger.’ Having been stuck in place, he had also been stuck in time. Others entering Jerusalem after long periods of being unable to do so described the experience as similarly disorienting, noting how the city had changed—they could not navigate it by the landmarks they remembered; it no longer seemed to be their city, as the urban reality did not correspond to their mental image.

The temporal regime is, however, not only marked by slowed-down movement that leads to a sense of greater distance. Palestinian time–space is also made unpredictable through spatial and administrative obstacles. The time commuters spent crossing from Jerusalem to its margins behind the Wall, or vice versa, varied greatly because conditions at the checkpoint—including the thoroughness of checks, the closure of roads or lanes, and the resulting traffic—were ever-changing. Nidal, who lived in Kufr Aqab and commuted to work in the East Jerusalem neighbourhood of Beit Hanina on the ‘Israeli’ side of the Wall, noted that although he left the house at the same time every day, 6:15, he never knew whether he would get to the clinic where he worked ‘too early or too late.’ Forced to pass through Qalandiya checkpoint, sometimes he arrived by 7:15 and sometimes a full hour later, leading to problems with his employer and a sense he was failing his patients. Data collected by international monitors confirm what Palestinians know from years of experience: the time required to pass through can fluctuate enormously. During the hours of the morning commute, for instance, average processing speeds at Qalandiya ranged from two to sixteen individuals per minute passing through the checkpoint (EAPPI Citation2014). While commuters acknowledged that various factors such as the Jewish religious calendar, wider political developments, or local clashes could influence the time needed to move into and through Jerusalem, a common impression was that the difficulty of passing through a checkpoint depended on the ‘mood of the soldiers’ (cf. Doumani Citation2004, 40; Kershner Citation2005, 16; Hammami Citation2015, 4).

Not only the duration of the wait but the location of disruption is often unpredictable for Palestinians. Age restrictions have occasionally been applied to residents of Shuafat Refugee Camp, for instance, preventing even Jerusalem ID holders from accessing the city centre via the local checkpoint. And delays are not limited to permanent checkpoints; they can also affect areas far inside East Jerusalem: Following a spike in violence in early October 2015, the city’s police department decided to regulate the entry and exit of a large number of neighbourhoods located on the western side of the Wall. Some thirty-eight roadblocks and checkpoints were installed, encircling neighbourhoods and restricting movement across East Jerusalem. The majority of these obstructions blocked vehicle access completely, and those which permitted the passage of cars produced long delays, with one observer recalling a three-hour wait at the exit of the Jabal Mukaber neighbourhood (Machsom Watch, personal communication, 10 January 2016). Like the Separation Wall, which is crossed daily by an estimated 14,000 Palestinian labourers without a permit to enter Israel (OCHA Citation2013), this closure was not impermeable. According to the mayor’s Deputy Advisor on Eastern Jerusalem Affairs, ‘the blocks were supposed to convey a message to the parents: “Take responsibility for your children!”’ (personal communication, 6 January 2016). Such reasoning appears to confirm residents’ sense that the disruption of Palestinian mobility is not an unintended side-effect of securitisation, but in itself the aim of mobility restrictions.

Due to the profound manner in which this unpredictable exertion of power affects Palestinians’ sense of temporality, some therefore referred to the ever-present possibility of delays, risks and detours as creating ‘occupation time’ (for a different use of the term, see Meneley Citation2008). Not only could soldiers stationed at checkpoints make time stretch out or contract, they also disrupted the continuity of time between different Palestinian areas. ‘Occupation time’, then, is out of synch with Israeli time on the one hand, and also creates a lack of ‘coevality’ among Palestinians on the other (Tawil-Souri Citation2017). Sovereignty and a sense of nationhood are grounded not only in shared historical reference points and myths of origin (Bowman Citation1999; Jamal Citation2016), but also in common timekeeping systems (Anderson Citation2006; Cohen Citation2018). Because Palestinians cannot refer to a shared set of predictable temporal standards, their ability to connect and carry out common projects is disrupted.

Resisting and mitigating ‘occupation time’

Palestinian commuters recounted a variety of tactics they used to make journeys more predictable and to mitigate the negative effects of erratic time–space under occupation, thereby reclaiming a sense of control over their daily schedules. Several respondents made use of alternative routes to minimise disruption. Mariam, for instance, who lived in Kufr Aqab and commuted to work in Jerusalem on a daily basis, did so using informal Ford Transit vans departing near Qalandiya checkpoint and taking a longer route into the city via the Hizma checkpoint. While this often did not save time, the detour allowed her to avoid passing through Qalandiya (see ), perceived as one of the most exhausting and humiliating checkpoints, on foot. Ibrahim even preferred taking a significantly longer route: he regularly commuted 90 min to his company’s offices in the Israeli city of Herzliya rather than crossing the checkpoint to his regular workplace in nearby Ramallah because he preferred a predictable journey to the uncertainty of the Qalandiya route, which could take anywhere between 20 and 90 min. Other Jerusalemites even sought to ‘win back’ lost time on a broader scale: Ahmad started an initiative encouraging commuters to read during long periods in traffic at the checkpoint. He saw his book lending scheme as a way to actively resist what he viewed as the occupation’s intentional wasting of Palestinians’ life time.

Yet it takes additional efforts on the part of those moving to maintain their own routines when time–space cannot be taken as a constant because its parameters are always shifting. They must continually try to foresee changes and adapt to new circumstances in an effort to minimise exhaustion, risk and uncertainty. Most commuters had contingency plans for getting to work in case the checkpoint was closed or if other unforeseen circumstances interrupted their routine. For example, Mahmoud and his family occasionally stayed overnight at relatives’ homes beyond the Wall when they could not pass through the checkpoint to return to Jerusalem. Having to consider all eventualities that might affect the daily routine and make backup arrangements was an additional drain on residents’ energy. Mariam stated: ‘I am so tired from the commute every day, I don’t visit friends much at all. It’s even affecting the relationship with my parents. These days, I visit them twice per month at the most.’ The unpredictability of ‘occupation time’ thus not only increases the sense of distance in the spatio-temporal sense but in the social as well.

The exhaustion caused by ‘occupation time’, combined with the fundamental insecurity of residency in Jerusalem, undermines Palestinians’ connection to the city. The legal status held by most Palestinian Jerusalemites is officially termed ‘permanent residency.’ Yet this status it is in no way permanent: Since 1967, over 14,500 East Jerusalemites have seen their residency permits revoked (Human Rights Watch Citation2017). To maintain their right to live in their hometown, they must uphold their presence and ties to the city. Legal procedures to safeguard the precarious residency status are costly, both financially and in terms of time. One woman in her thirties noted: ‘I’ll be eighty by the time I regularise my permanent residency in the city.’ The seemingly endless struggles to maintain both the flow of the everyday and longer-term life trajectories led to some feeling as though they could neither enjoy the little access to Jerusalem they maintained, nor plan for a future in the city. Several women living both on the eastern and on the western side of the Wall were so ground-down by ‘occupation time’ that they frequently spoke of leaving Israel/Palestine entirely, and even made concrete arrangements to do so. Thus, while the threat of expulsion from their hometown looms over residents, many consider emigration, and thereby forfeiting their right to the city voluntarily, in order to exert agency over their futures. The desire to leave the situation behind altogether, expressed by many, has wider political repercussions, as it also reflects giving up a collective Palestinian claim to the city. Temporal deregulation forces residents to focus their efforts on managing everyday challenges and thereby contributes to what has frequently been described as a state of ‘permanent temporariness’ (Yiftachel Citation2009; see also Weizman Citation2007; Hanafi Citation2008; Abourahme Citation2011; Tawil-Souri Citation2017; Peteet Citation2018), with a Palestinian future deferred as the ostensibly temporary occupation becomes ever more permanent in a ‘creeping’ manner (Yiftachel Citation2005).

Unpredictability as deregulation

The ‘occupation time’ described serves several strategic purposes for Israel. On the one hand, it legitimises the occupation by constructing Palestinians as erratic subjects, lacking modernity and the ability to self-regulate. On the other, it feeds into the Israeli goal of maintaining a ‘demographic balance’—that is, reducing the proportion of Palestinians living in the city (Jerusalem Municipality Citation2005; see also Chiodelli Citation2012). It does so by severing the ties between Jerusalemites and their city in a slowly-encroaching manner that operates through the experience of the urban everyday. As we have seen, commuters saw the constant redefinition of the rules of Palestinian movement as a fundamental aspect of moving into and around Jerusalem, and felt at the mercy of a system that was not accountable to them. Indeed, numerous authors have noted that arbitrariness is a tool with which the Israeli occupation controls Palestinian lives, both in the legal-administrative and in the spatial realms (Handel Citation2009, 214; Azoulay and Ophir Citation2013, 90; Kotef Citation2015; Berda Citation2017; Rijke and Minca Citation2018). The uncertainty governing Palestinian time might thus also be viewed as part of what has been referred to as ‘strategic confusion’ (Pullan Citation2013b).

We can better understand the strategic nature of an ‘occupation time’ that can expand and contract unexpectedly by reading it as ‘deregulated.’ Roy argues that urban informality in India is the result of ‘calculated deregulation’ (Citation2009) and intentional ‘unmapping’, that is, maintaining informal circumstances that enable the expropriation and displacement of residents deemed transgressors (Roy Citation2004, 156ff). While Roy’s argument relates to the precarious status of housing, in Jerusalem it is the allocation of time that is unpredictable.Footnote3 Roy shows that deregulation allows the state to declare illegality when it suits its interests to exclude, displace, or dispossess those found to be living in informal circumstances. Thus, informality resulting from deregulation is ‘an instrument of both accumulation and authority’ (Roy Citation2009, 81) rather than a gap in state control.

In the case discussed by Roy, the label of ‘illegality’ is applied to squatter settlements and used to dispossess them, while the informality of the rich is easily formalised. In Jerusalem, the irrationality of the deregulated temporal system of occupation is attributed to the individuals living under it. By embedding itself in their lives and shaping their relations in the city, deregulated time marks them with attributes which are then used to implicitly justify revoking their access to the city. Kotef (Citation2015) has shown how the mobility regime that deems Palestinians constant transgressors of invisible boundaries constructs them as unruly and uncivilised subjects, unable to self-govern. As Palestinians must operate within ‘arrhythmic’ temporalities (Peteet Citation2018, 60), they are also constructed as untimely subjects, and thus designated as in need of Israeli constraint and control. This exertion over others’ use of time, manifested for instance in a colonial ‘hierarchy of waiting’ (Barak Citation2013, 54), further reinforces the sovereign’s position of power (Fieni Citation2014) by assigning a different temporality to the colonised (Fabian Citation2014).

Perhaps more significantly, insofar as it weakens the links of Palestinians to the city, deregulation also serves strategic purposes in that it allows the state to pursue its demographic aims informally, alongside a seeming policy of no policy vis-à-vis the municipal exclaves beyond the Wall.Footnote4 Instead of a formal, de jure redrawing of boundaries to exclude a large proportion of the city’s Arab population, or a mass revocation of their residency, their ties are severed through the experience of the urban everyday. Deregulated time disrupts communication and exchange and reduces participation in the city. In even pushing Palestinian Jerusalemites to contemplate emigration, it feeds into the ‘quiet deportation’ (B’Tselem and HaMoked Citation1997) required to minimise the city’s Arab population. Thus, the temporal regime generated by the occupation creates the conditions that both legitimise it and reinforce its perpetuation. In this way, it fuses the ‘past, ongoing present and immediate future’ of dispossession (Hammami Citation2015, 7; see also Jabary Salamanca et al. Citation2012).

Normalisation through synchronisation

While Palestinians, particularly those navigating the edge of Jerusalem, experience time as deregulated, in another—seemingly opposing—temporal development, Palestinian movements are increasing synchronised with Israeli schedules. This has become especially apparent in recent years as Palestinian public transport in the city, long informal and separate from the Israeli transportation system, has been gradually formalised and subsumed into Israeli structures. I argue that Palestinian quotidian schedules and routines are thereby ‘normalised’ in the sense of Foucault (Citation2007): they are aligned with Israeli systems of time-keeping, minimising their deviation through incorporation into the dominant system. Because speedy, efficient, and predictable movement has an undeniable appeal of modernity, it is also embraced by East Jerusalemites. The dynamics described are part of wider developments that have taken place in East Jerusalem over the past decade under the administration of Israeli mayor Nir Barkat (2008–18). As I have described elsewhere, processes of regulation, acceleration, and normalisation are also at work on new infrastructures such as the Jerusalem Light Rail, the construction of new highways, and upgrades to the streetscape in East Jerusalem (Baumann Citation2018). Building upon this, the following section examines the case of the Jerusalem-Ramallah Bus Company.

The formalisation of unruly movements

Many Palestinian bus companies have operated in Jerusalem as family businesses since the British Mandate period. With the establishment of the Palestinian Authority during the Oslo Accords and the ensuing closure of Jerusalem in 1994, the operation of Palestinian bus lines connecting East Jerusalem to its West Bank hinterlands decreased significantly (Beit Sahour Bus Company, personal communication, 31 August 2014). By 1998, over 1200 informal collective taxis were transporting an estimated eighty percent of all passengers—80,000 per day—thereby further eroding the business of established transport companies, who were left with only 72 vehicles (JTMT Citation2006). Unlike the old, unwieldy buses, these vans—referred to as ‘Transits’—could pick up passengers at high rates even in small side streets, and were able to circumvent Israeli military checkpoints by altering their routes.

Yet residents were not fond of the informal system. Transit drivers often did not have a license, registration or insurance, and drove accordingly. East Jerusalem residents like Hamdi were resentful that they were forced to rely on unaccountable ‘teenagers’ and ‘school drop-outs’, who were widely believed to be collaborators with Israeli security services, as well as involved in drugs and crime. Indeed, several interviewees claimed that the Israeli security establishment supported the quasi-criminal Transit operators, who made East Jerusalem more dangerous. Supporting this notion, one Israeli official stated that the approach of the Israeli authorities was ‘the more chaos, the better’ (Amir Cheshin quoted in Zalen Citation2010), suggesting that in the Palestinian public transport sector too, deregulation functioned as a form of control. Ultimately, several instances of harassment by Transit drivers, as well as the rape of a female passenger, outraged residents to the degree that they approached the Israeli authorities to ask them to stop turning a blind eye (Mohammed Nakhal Citation2008 and personal communication, 20 August 2014).

Based on this, the Jerusalem Transportation Masterplan Team (JTMT) initiated a plan for the reform of East Jerusalem’s public transport sector in 2002. Next to funding a special police unit to combat the informal transport providers, the Ministry of Transport (MoT) provided the existing companies with subsidies, at first in the form of used Israeli buses. Routes were coordinated and companies were encouraged to merge, initially forming a consortium. The buses were given unified branding and bus drivers matching uniforms, ticket pricing and design were coordinated, and subsidies were provided for discounted fares. The physical infrastructure of the central bus stations was upgraded and shelters were installed at newly-designated bus stops along the route. By 2014, the number of Transits had shrunk to a few dozen and the official companies transported over 90,000 passengers per day (JTMT Citation2014; see also Jerusalem Institute for Policy Studies Citation2017). An agreement between the consortium of bus companies and the ministry, signed in July 2014, increased the level of subsidies. However, this also made the bus companies’ activities more ‘legible’ to Israeli authorities in the sense of Scott (Citation1998), who has shown how state power seeks to simplify local knowledges, practices and spaces in order to make these more compressible and controllable through standardisation and facilitate their assimilation into its own administrative apparatus.

Infrastructures, especially those enabling fast and smooth movement, are always imbued with an aura of progress (Larkin Citation2013). Indeed, the reform of the bus companies was conceptualised by the Israeli authorities as part of a modernisation project. According to the lawyer who negotiated the 2014 agreement, the Ministry of Transport believed the level of service provision in East Jerusalem needed to be ‘raised’ to the standard of Israeli companies and that East Jerusalem was not yet ‘mature’ enough for the full enforcement of all Israeli regulations. Because of these special local circumstances, the usual requirement of issuing a tender for public transportation permits was suspended due to the government’s awareness that ‘the local population would not accept outside operators’ (personal communication, 17 August 2014). Yet, despite these interim concessions to local circumstances, which Shlomo (Citation2017) refers to as creating ‘sub-formality’, the ultimate aim was to overcome ‘archaic’ local structures, rooted in the local hamula (extended family) system, and issue public tenders by 2020. According to the lawyer, the understanding was that the support provided by the MoT and JTMT was also a way of contributing to the development of East Jerusalem. Regulated and efficient movement here is constructed as part of wider socio-economic progress, with effects that go beyond public transport.

Scheduling, surveillance, and self-regulation

The effects of JTMT’s efforts to formalise the local bus companies has been particularly apparent in the case of the Jerusalem-Ramallah Bus Company (JRBC). A merger of five smaller companies, the JRBC forms the backbone of the connection between East Jerusalem and its northern suburbs (see ; see also Shibli Citation2011). With its 120 vehicles transporting some 25,000 passengers per day, it is the largest company under the umbrella of the consortium. The JRBC has been at the forefront of implementing a set of new technologies, regulations, and enforcement mechanisms stipulated by the MoT, which the company’s management routinely referred to as ‘the Programme.’ A complex new scheduling system, which took the Head Engineer weeks to set up, and his computer 24 h to tabulate, ensured that routes and timings of movements took place in accordance with the MoT’s stipulations. It also involved the possibility of real-time surveillance by the ministry: ‘When I open the programme, they know exactly everything I do’, he noted, ‘When I type, they know.’

GPS devices were installed in the vehicles, allowing the monitoring of each bus’s whereabouts. While in the past, drivers frequently made detours—to avoid traffic or a temporary military checkpoint, or merely to drop off some groceries at home—this was now no longer possible. The Operations Manager explained: ‘We can see where he is, and we get an alarm if he goes off his route or is behind schedule.’ Due to their newly predetermined routes and time slots, bus drivers were unable to evade checkpoints like the more flexible informal transport providers. They now had to contact JTMT—who maintained direct lines of contact with checkpoint commanders—if they encountered any issues with Israeli security services. This legibility was enforced by fines up to 10,000 Israeli Shekels (approximately £2000) for deviations from the schedule and route. Some two thousand inspectors across all bus lines, many working undercover, reported any irregular behaviour. As the bus company management struggled to enforce the new regulations, it devised an internal system of reorganised hierarchies, reporting, inspection, and customer feedback on infractions to pre-empt more fines. It thus encouraged its staff and passengers not only to change their own behaviour but also to police the behaviour of others.

The reforms were also cast in moral terms, with the guiding principles of the consortium summarised on one of the first official maps comprising all of East Jerusalem’s bus lines (see ). Having been encouraged by the MoT to hire Transit drivers, previously viewed as dangerous elements who made the city centre unsafe, the company appeared to even see itself as able to reform lapsed characters. Drivers often had a reputation for illicit activity and lack of reliability, one manager related, pointing out a particular driver, who had been a ‘drinker and a gambler’ before. With the support of the head of the company, however, I was told, he had changed his ways and even become quite pious. Self-care (albeit always with an eye to outside perceptions) was also encouraged: drivers were admonished to ensure a tidy self-presentation by wearing the standardised shirt with the consortium logo, ironed and tucked into the trousers, not to smoke, and to keep their buses clean. Corporate formalisation and the regulation of schedules were thus also linked to discourses of self-improvement—suggesting again that the normalisation of untimely mobile subjects is equated with progress.

The normalising force of ‘annexation time’

Foucault argues that the ‘matter of organizing circulation’ is a key element of governing cities: to him, this involves ‘eliminating its dangerous elements, making a division between good and bad circulation, and maximizing the good circulation by diminishing the bad’ (Foucault Citation2007, 18). We have seen here how the temporal normalisation in the bus sector seeks to ‘reduce the most unfavorable, deviant’ elements through inclusion by ‘bring[ing] them in line with the normal’ (Foucault Citation2007, 62) and encouraging state-sanctioned movements. The synchronisation of Palestinians’ rhythms and movements minimises their deviation to align them with the interest of state power. In this sense, ‘the Programme’ not only ‘normalised’ the unruly movements of the informal Transits, as well as the activities of companies previously operating in a semi-formal manner, but also the individual drivers who were absorbed and reformed. Rather than exclude dangerous elements, as disciplinary power does, we see how normalisation integrates them in order to minimise risk. In coordinating with Israeli security at checkpoints, the JRBC became linked to the governing system that Palestinian public transport had previously sought to constantly avoid. Customers benefited from more reliable and speedy transport, but the state was able to better control their schedules and movements. In the process, Palestinian customers were constituted as new types of mobile subjects—not only compelled to follow new regulations but effectively becoming part of the surveillance apparatus.

As it furthered Israeli control over the rhythms of the Palestinian city, the synchronised and normalised time gradually imposed on the company can be conceived of as ‘annexation time.’ Because there is no framework for autonomous Palestinian institutions in East Jerusalem under occupation, any formalisation entails the involvement of the Israeli authorities. Thus, the self-regulation embraced by the management strengthens Israel’s hold on East Jerusalem. Speedy, timely and reliable transport services improve ease of movement and make everyday urban life more predictable for residents. But they come at the expense of autonomy, as Palestinians’ increasingly regulated and synchronised movements are more legible to, and thus controllable by, the Israeli state. This is part of a wider process of political normalisation of the occupation wherein Palestinian Jerusalemites’ participation in Israeli structures has increased in arenas beyond mobility. For instance, more Palestinians are entering the Israeli education system, and an increasing number is applying for Israeli citizenship (cf. Hasson Citation2012; International Crisis Group Citation2012). While this kind of normalisation enhances East Jerusalemites’ ability to go about everyday activities and forge life plans, it undermines the collective Palestinian claim to the city by acknowledging, and engaging with, Israeli authority. Time here functions as an immaterial infrastructure which tethers East Jerusalem to the West of the city and thereby perpetuates its annexation. Rather than through physical urban space or legal decrees, this link operates through residents’ everyday lives and routines.

As the JRBC management embraced the Israeli ministry’s programme and customers welcomed the more reliable service, there was also resistance to the changes—indeed, even the company leadership had to find ways around the strict regulations. Bus drivers and internal inspectors positioned along the route to verify that buses were on schedule initially did not support the implementation of ‘the Programme.’ They purposefully left the bus station too early or too late or noted false arrival times of buses on checklists. This was because they worried it would make their jobs obsolete, according to the management. Over time, employees were coaxed into cooperation, through incentives, as well as by the threat of being fired. Yet even the managers who promoted the process of synchronisation were forced to deviate from the Israeli-imposed schedule at times. The rationalised time of ‘the Programme’ was at odds with the reality of ‘occupation time’: The rigid schedule, backed up by 123 regulations and enforced through countless fines, did not account for the unpredictable elements of traffic in East Jerusalem, especially delays caused by checkpoints and random border police controls. Thus, the bus company’s Operations Manager saw himself forced to trick the system, so as not to be penalised for delays beyond his control. In order to avoid fines under the pressure of constant monitoring, he entered fewer than half of the actual trips made into the ministry’s scheduling system. While this omission meant lower subsidies from the MoT, it allowed him to ‘buy time’ and have flexibility in case buses were delayed at Qalandiya checkpoint. The imposed rationalised time may have been synchronised with Israeli schedules, but as this new temporality frequently clashed with ‘occupation time’, it left Palestinians struggling to overcome the disjunction. This brings us to the question of how these two simultaneously operating but oppositional temporalities are entangled.

Conclusion: time as an infrastructure of control

Two temporal regimes are at work in Palestinian Jerusalem simultaneously. One deregulates time, making it unpredictable while causing time–space divergence. This serves to disconnect Palestinians from Jerusalem by increasing the effort they must exert to access and participate in the city, and by limiting the futures that they can imagine as possible in it. In thus weakening the links of Palestinians to the city, both in the everyday and the long term, deregulated ‘occupation time’ can be considered a strategic ‘mode of regulation’ (Roy Citation2009), as it serves Israel’s explicitly stated policy aim of minimising the city’s Palestinian population. The other temporal regime, which I have called ‘annexation time’, normalises Palestinian schedules by synchronising the rhythms of urban mobility between East and West Jerusalem. Although speedy movement has long been equated with ‘autonomy and freedom’ (Moran, Piacentini, and Pallot Citation2012; cf. Kotef Citation2015), in the advancing incorporation of East Jerusalem, as well as its increasing disconnect from the West Bank, we see that the normalised temporality of formal public transport in fact fosters dependency and control. Because Palestinians must straddle these two temporal systems, they are forced to navigate the discrepancies between ‘occupation time’ and ‘annexation time’, whether they queue at the checkpoint before sunrise to avoid being late for work, or expend their own company’s resources to make up for delays they can no longer circumnavigate.

These two temporalities appear at odds with one another, yet they form one infrastructure serving the same purpose through different articulations of time. Unpredictably stretched out and contracted ‘occupation time’ becomes the means of undermining interactions and disrupting social lives. In tabulated, predictable, and enforced ‘annexation time’, on the other hand, the time of the schedule becomes an ‘architecture for circulation’ (Larkin Citation2013, 228) as well as for surveillance and control. As we have seen, time thus does not fulfil its liberatory promise where it is employed as a rationalised system, and does not cease to operate as a governing device even where the regular units of clock time are purposefully unravelled. In that it enables both expulsion and annexation on a longer time-scale, time operates as a means of control in both temporalities: when facilitating exclusion through temporal deregulation, and when enabling securitised circulation through normalisation, it is used by the occupation to perpetuate its aims. Like a physical infrastructure, time determines possibilities and structures relationships, thereby serving as a powerful means of determining degrees of exclusion and incorporation.

Most studies of ‘infrastructural violence’ have focused on the exclusion from, or disruption of, access to infrastructures and the resources they distribute (Graham and Marvin Citation2001; Graham Citation2010; Rodgers and O'Neill Citation2012; Graham and McFarlane Citation2015). This examination of time as infrastructure in East Jerusalem has added to this understanding in two ways. Firstly, employing Roy’s notion of deregulation has allowed us to see how infrastructural disconnect, or the absence of shared standards, can itself be an expression of state control, as deregulated temporality demonstrates the ability of the occupation to dictate Palestinian lives. Secondly, as incorporation into Israeli systems of timekeeping, too, is tied up with an enduring process of dispossession, it has become apparent that violence is also involved in infrastructural inclusion (cf. Baumann Citationforthcoming). Similarly ignoring the violent potential of incorporation, literature on Palestinian mobility and temporality has mainly focused on the disruption of movement and the slowing down of time as expressions of the occupation’s violence. The notion that the occupation is ‘stealing’ Palestinian time (Peteet Citation2008, Citation2018), for instance, suggests that time is a limited resource. This is complicated by the effects of ‘annexation time’ I have described. Viewing it as an infrastructure that distributes resources and enables activities perhaps better accounts for the various guises time can take for Palestinians living under Israeli rule.

The seemingly contradictory nature of the two temporalities at work in Jerusalem is also indicative of East Jerusalemites’ paradoxical relationship to the Israeli state. Living on annexed territory, they are stateless; deemed ‘permanent’ residents, their links to their hometown are nonetheless increasingly frail. Within its current self-definition as both a Jewish and a democratic state, Israel’s ambivalent stance vis-à-vis its Palestinian non-citizen subjects in Jerusalem cannot be resolved (cf. Azoulay and Ophir Citation2013; Robinson Citation2013). Within this field of tension, degrees of exclusion and incorporation are therefore constantly re-negotiated through the practices of urban everyday life. The de/regulation of time, especially by way of urban mobility, makes it an ideal infrastructure of control because it can be adapted to changing circumstances. Because of its flexibility to engender a range of temporalities, time is a potent vehicle for modulating degrees of exclusion and incorporation. It becomes a means of stabilising the seemingly untenable situation by excluding some and incorporating others.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my interlocutors, especially at the Jerusalem-Ramallah Bus Company, for giving their time so generously. Many thanks also to the editors of this Special Feature and the reviewers. This research formed part of my doctoral work, which was funded by the Gates Cambridge Trust. Fieldwork was further supported by the Kettle’s Yard Travel Fund, the Cambridge Faculty of Architecture and History of Art, and the Council for British Research in the Levant.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

ORCID

Hanna Baumann http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3583-3833

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hanna Baumann

Hanna Baumann is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at The Bartlett’s Institute for Global Prosperity, University College London. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 No official figures on the population of these areas, and the percentage of Jerusalem ID holders, are available, as Ir Amim (Citation2015) notes. The estimate of 100,000 Palestinian Jerusalemites was however confirmed by several sources.

2 Pseudonyms are used throughout for residents.

3 To be sure, the unmapping of Jerusalem’s exclaves also extends to the construction sector. While building regulations are stringently enforced in Palestinian areas of central Jerusalem (Braverman Citation2007), unplanned construction without building permits is rife in the exclaves of Kufr Aqab and Shuafat Refugee Camp (Rosen and Charney Citation2016). In addition, municipal services are severely neglected in these areas, leading to increasing informalisation. Some observers argue that the municipality is turning a blind eye in order to shift a larger portion of Palestinians beyond the Wall (Alkhalili, Dajani, and De Leo Citation2014).

4 There have been occasional calls to formally cede Israeli responsibility for the exclaves beyond the Wall, including from the mayor of Jerusalem and the Israeli Prime Minister (ACRI Citation2011; Ravid Citation2015). Yet such an act would require a two thirds majority in parliament and municipal officials in charge of these areas argued the city was unlikely to ever give up its sovereignty (David Koren and Nadera Jabr, personal communications on 25 and 26 August 2015, respectively).

References

- Abourahme, Nasser. 2011. “Spatial Collisions and Discordant Temporalities: Everyday Life between Camp and Checkpoint.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35 (2): 453–461. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.01034.x.

- ACRI. 2011. “Jerusalem Municipality is Responsible for Its Residents Beyond the Barrier.” Association for Civil Rights in Israel, December 15. www.acri.org.il/en/2011/12/15/acri-letter-to-mayor-barkat.

- Alkhalili, Noura, Muna Dajani, and Daniela De Leo. 2014. “Shifting Realities: Dislocating Palestinian Jerusalemites from the Capital to the Edge.” International Journal of Housing Policy 14 (3): 257–267. doi: 10.1080/14616718.2014.933651

- Allen, Lori. 2008. “Getting by the Occupation: How Violence Became Normal During the Second Palestinian Intifada.” Cultural Anthropology 23 (3): 453–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1360.2008.00015.x

- Anand, Nikhil, Akhil Gupta, and Hannah Appel, eds. 2018. The Promise of Infrastructure. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Anderson, Benedict. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Revised edition. London: Verso.

- Azoulay, Ariella, and Adi Ophir. 2013. The One-State Condition: Occupation and Democracy in Israel/Palestine. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Backmann, Rene. 2010. A Wall in Palestine. New York: Picador.

- Barak, On. 2013. On Time: Technology and Temporality in Modern Egypt. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Baumann, Hanna. 2016. “Enclaves, Borders, and Everyday Movements: Palestinian Marginal Mobility in East Jerusalem.” Cities (London, England) 59: 173–182. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2015.10.012.

- Baumann, Hanna. 2018. “The Violence of Infrastructural Connectivity: Jerusalem’s Light Rail as a Means of Normalisation.” Middle East - Topics & Arguments 10 (June): 30–38. doi:10.17192/meta.2018.10.7593.

- Baumann, Hanna. forthcoming. “Infrastructural Violence in Jerusalem: Exclusion, Incorporation and Resistance in a Contested ‘Cyborg City’.” In Reverberations: Violence Across Time and Space, edited by Yael Navaro, Zerrin Özlem Biner, Alice von Bieberstein, and Seda Altug. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Berda, Yael. 2017. Living Emergency: Israel's Permit Regime in the Occupied West Bank. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Bowker, Geoffrey C., and Susan Leigh Star. 1999. Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Bowman, Glenn. 1999. “The Exilic Imagination: The Construction of the Landscape of Palestine from its Outside.” In The Landscape of Palestine: Equivocal Poetry, edited by Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, Roger Heacock and Khaled Nashef, 53–78. Birzeit: Birzeit University Publications.

- Braverman, Irus. 2007. “Powers of Illegality: House Demolitions and Resistance in East Jerusalem.” Law & Social Inquiry 32: 333–372. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4469.2007.00062.x.

- B’Tselem and HaMoked. 1997. “The Quiet Deportation: Revocation of Residency of East Jerusalem Palestinians.” www.btselem.org/publications/summaries/199704_quiet_deportation.

- Chiodelli, Francesco. 2012. “The Jerusalem Master Plan: Planning into the Conflict.” Jerusalem Quarterly 51: 5–20.

- Cohen, Elizabeth F. 2018. The Political Value of Time: Citizenship, Duration, and Democratic Justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Doumani, Beshara. 2004. “Scenes from Daily Life: The View from Nablus.” Journal of Palestine Studies 34 (1): 37–50. doi:10.1525/jps.2004.34.1.37.

- EAPPI. 2014. “Checkpoint Monitoring Statistics for Qalandiya Crossing, between 5:00 and 8:00am (2010–2014).” Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel, Unpublished.

- Easterling, Keller. 2014. Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space. London: Verso.

- Fabian, Johannes. 2014. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Fieni, David. 2014. “Cinematic Checkpoints and Sovereign Time.” Journal of Postcolonial Writing 50 (1): 6–18. doi:10.1080/17449855.2013.850212.

- Foucault, Michel. 2007. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the College De France, 1977–78. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Graham, Stephen, ed. 2010. Disrupted Cities: When Infrastructure Fails. New York and London: Routledge.

- Graham, Stephen, and Simon Marvin. 2001. Splintering Urbanism: Networked Infrastructures, Technological Mobilities and the Urban Condition. London: Routledge.

- Graham, Stephen, and Colin McFarlane, eds. 2015. Infrastructural Lives: Urban Infrastructure in Context. London: Routledge.

- Hammami, Rema. 2015. “On (not) Suffering at the Checkpoint; Palestinian Narrative Strategies of Surviving Israel’s Carceral Geography.” Borderlands 14 (1). www.borderlands.net.au/vol14no1_2015/hammami_checkpoint.pdf.

- Hanafi, Sari. 2008. “Palestinian Refugee Camps in Lebanon: Laboratories of State-in-the-Making, Discipline and Islamist Radicalism.” In Thinking Palestine, edited by Ronit Lentin, 82–100. New York: Zed Books.

- Handel, Ariel. 2009. “Where, Where to, and When in the Occupied Territories: An Introduction to the Geography of Disaster.” In The Power of Inclusive Exclusion. Anatomy of Israeli Rule in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, edited by Adi Ophir, Michal Givoni and Sari Hanafi, 179–222. New York: Zone Books.

- Handel, Ariel. 2014. “Gated/Gating Community: The Settlement Complex in the West Bank.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 39 (4): 504–517. doi:10.1111/tran.12045.

- Harvey, David. 1989. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. London: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hasson, Nir. 2012. “Education a Waypoint for Palestinians on the Route to Work in Israel (in Hebrew).” Ha'aretz, August 28.

- Human Rights Watch. 2017. “Israel: Jerusalem Palestinians Stripped of Status: Discriminatory Residency Revocations.” www.hrw.org/news/2017/08/08/israel-jerusalem-palestinians-stripped-status.

- International Crisis Group. 2012. “Extreme Makeover? (II): The Withering of Arab Jerusalem.” www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/eastern-mediterranean/israelpalestine/extreme-makeover-ii-withering-arab-jerusalem.

- Ir Amim. 2012. Permanent Residency: A Temporary Status Set in Stone. Jerusalem: Ir Amim.

- Ir Amim. 2015. Displaced in Their Own City: The Impact of the Israeli Policy in East Jerusalem on the Palestinian Neighbourhoods of the City Beyond the Separation Barrier. Jerusalem: Ir Amim.

- Jabary Salamanca, Omar, Mezna Qato, Kareem Rabie, and Sobhi Samour. 2012. “Past is Present: Settler Colonialism in Palestine.” Settler Colonial Studies 2 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1080/2201473X.2012.10648823.

- Jamal, Amal. 2016. “Conflict Theory, Temporality, and Transformative Temporariness: Lessons from Israel and Palestine.” Constellations (Oxford, England) 23 (3): 365–377. doi:10.1111/1467-8675.12210.

- Jerusalem Institute for Policy Studies. 2017. “Table X/13 - The Public Transportation System in East Jerusalem, 1998–2016.” Statistical Yearbook of Jerusalem. www.jerusaleminstitute.org.il/.upload/yearbook/2017/shnaton_J1317.pdf.

- Jerusalem Municipality. 2005. “Report No. 4: The Proposed Plan and the Main Planning Policies [unofficial translation].” Local Outline Plan Jerusalem 2000. City Engineer Planning Administration, City Planning Department.

- JTMT. 2006. “Reorganization of the Public Transportation in East Jerusalem 2004.” Jerusalem Transportation Masterplan Team, Unpublished PowerPoint presentation.

- JTMT. 2014. “Reorganisation of the Public Transportation in East Jerusalem – 2014 Update [in Hebrew].” Jerusalem Transportation Masterplan Team, Unpublished PowerPoint presentation.

- Kershner, Isabel. 2005. Barrier: The Seam of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kotef, Hagar. 2015. Movement and the Ordering of Freedom: On Liberal Governances of Mobility. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Larkin, Brian. 2013. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (1): 327–343. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522.

- Lustick, Ian S. 1997. “Has Israel Annexed East Jerusalem?” Middle East Policy 5: 34–45. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4967.1997.tb00247.x.

- Massey, Doreen. 1992. “Politics and Space/Time.” New Left Review 196: 65–84.

- Massey, Doreen. 1994. “A Global Sense of Place.” In Space, Place and Gender, edited by Doreen Massey, 146–156. Cambridge: Polity.

- Meneley, Anne. 2008. “Time in a Bottle: The Uneasy Circulation of Palestinian Olive Oil.” Middle East Report 248: 18–23. doi:10.2307/ 25164860.

- Moran, Dominique, Laura Piacentini, and Judith Pallot. 2012. “Disciplined Mobility and Carceral Geography: Prisoner Transport in Russia.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 37 (3): 446–460. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00483.x.

- Nakhal, Mohammed. 2008. “The Public Transport System in East Jerusalem [in Hebrew].” Unpublished.

- OCHA. 2013. The Humanitarian Impact of the West Bank Barrier on Palestinian Communities: East Jerusalem. Jerusalem: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Occupied Palestinian Territory.

- Ogle, Vanessa. 2015. The Global Transformation of Time, 1870–1950. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Parizot, Cédric. 2009. “Temporalities and perceptions of the separation between Israelis and Palestinians.” Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem 20. http://bcrfj.revues.org/6319.

- Peteet, Julie. 2008. “Stealing Time.” Middle East Report 248: 14–15.

- Peteet, Julie. 2018. “Closure’s Temporality: The Cultural Politics of Time and Waiting.” South Atlantic Quarterly 117 (1): 43–64. doi:10.1215/00382876-4282037.

- Pullan, Wendy. 2013a. “Conflict’s Tools. Borders, Boundaries and Mobility in Jerusalem’s Spatial Structures.” Mobilities 8: 125–147. doi:10.1080/17450101.2012.750040.

- Pullan, Wendy. 2013b. “Strategic Confusion: Icons and Infrastructures of Conflict in Israel-Palestine (Interventions in the Political Geographies of Walls).” Political Geography 33 (c): 52–62. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.11.005.

- Prasad, Ritika. 2013. “‘Time-Sense’: Railways and Temporality in Colonial India.” Modern Asian Studies 47 (4): 1252–1282. doi:10.1017/S0026749X11000527.

- Ravid, Barak. 2015. “Netanyahu Mulls Revoking Residency of Palestinians Beyond E. Jerusalem Separation Barrier.” Ha'aretz, October 25.

- Rijke, Alexandra, and Claudio Minca. 2018. “Checkpoint 300: Precarious Checkpoint Geographies and Rights/Rites of Passage in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.” Political Geography 65: 35–45. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.04.008.

- Robinson, Shira. 2013. Citizen Strangers: Palestinians and the Birth of Israel’s Liberal Settler State. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Rosa, Hartmut, and William E. Scheuermann. 2009. “Introduction.” In High-speed Society: Social Acceleration, Power, and Modernity, edited by Hartmut Rosa and William E. Scheuermann, 1–32. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Rodgers, Dennis, and Bruce O'Neill. 2012. “Infrastructural Violence: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Ethnography 13 (4): 401–412. doi:10.1177/1466138111435738.

- Rosen, Gillad, and Igal Charney. 2016. “Divided We Rise: Politics, Architecture and Vertical Cityscapes at Opposite Ends of Jerusalem.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 41 (2): 163–174. doi:10.1111/tran.12112.

- Roy, Ananya. 2004. “The Gentleman's City: Urban Informality in the Calcutta of New Communism.” In Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America and South Asia, edited by Ananya Roy and Nezar Alsayyad, 147–170. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Roy, Ananya. 2009. “Why India Cannot Plan its Cities: Informality.” Insurgence and the Idiom of Urbanization. “ Planning Theory 8: 76–87. doi:10.1177/1473095208099299.

- Schivelbusch, Wolfgang. 1977. The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the 19th Century. Leamington Spa: Berg.

- Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Shibli, Adania. 2011. “The United Transport Company – Jerusalem.” Jadaliyya. www.jadaliyya.com/Details/24085.

- Shlomo, Oren. 2017. “Sub-formality in the Formalization of Public Transport in East Jerusalem.” Current Sociology 65 (2): 260–275. doi:10.1177/0011392116657297.

- Tawil-Souri, Helga. 2017. “Checkpoint Time.” Qui Parle 26 (2): 383–422. doi:10.1215/10418385-4208442.

- Weizman, Eyal. 2007. Hollow Land: Israel's Architecture of Occupation. London: Verso.

- Yacobi, Haim. 2015. “Jerusalem: From a ‘Divided’ to a ‘Contested’ City—and Next to a Neo-apartheid City?” City 19 (4): 579–584. doi:10.1080/13604813.2015.1051748.

- Yiftachel, Oren. 2005. “Neither Two States Nor One: The Disengagement and ‘Creeping Apartheid’ in Israel/Palestine.” The Arab World Geographer 8 (3): 125–129.

- Yiftachel, Oren. 2009. “Critical Theory and ‘Gray Space’: Mobilization of the Colonized.” City 13 (2–3): 246–263. doi:10.1080/13604810902982227.

- Zalen, Matt. 2010. “Transported Back in Time.” Jerusalem Post, September 4.