Abstract

This visual essay introduces the concept of ‘thrownapartness’ as an embedded logic of contemporary urbanization, existing in dialectical tension with ‘throwntogetherness’. Tracing the working of urban walls, displacement and abandonment on the fringes of Al-Quds/Jerusalem provides a stark contrast to the perceived image of cities as hubs of mixing, toleration and liberalism. In Al-Quds, as in a growing number of cities, minorities and marginalized groups are commonly racialized, displaced and segregated, creating a colonial regime of de-facto urban apartheid. In such settings, Doreen Massey's concept of ‘throwntogetherness’ appears like a distant mirage, with its portrayal of flexibility, indifference and coexistence (albeit within an exploitive political economy and oppressive ‘power geometries’). In times of rapid change and multiple crises, the putative ‘threat’ from ‘unwanted’ or ‘deeply different’ groups harbored in urban space drives authorities to use colonial separation strategies, such as ghettoization or ‘gray spacing’ which minimize or prevent encounters. Such settings, we argue, require critical attention to ‘urban thrownapartness’ – a concept that extends Massey's formulations of ‘throwntogetherness’, in order to better fathom the workings of contemporary cities.

This visual essay takes the readers through the harsh edges of a pervasive urban phenomenon we term ‘thrownapartness’. We define and illustrate the concept in dialogue with the concept of ‘throwntogetherness’, through the case of Al-Quds/East Jerusalem.

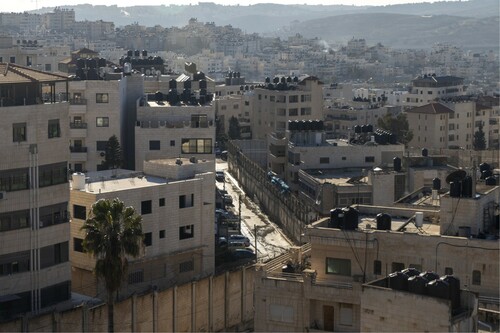

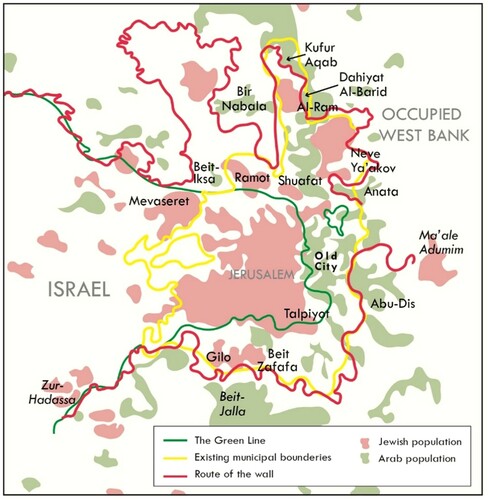

Zoom in – Let us begin our walk through the neighborhoods of Bir Nabala and Kufur Aqab with scenes of dozens of abandoned homes and closed businesses, surrounded by blight and decline (see and ). This slice of the city lies at the north-eastern fringe of the Jerusalem/Al-Quds municipal area, conquered by Israel from Jordan, occupied and colonized since 1967. This has included the settlement of some 230,000 Jews in Palestinian Al-Quds/Jerusalem beyond the Green Line (the recognized international border). These Israeli moves are in direct breach of international law, which prohibits the transfer of population into occupied territory. No state has recognized Israel's right to rule Palestinian al-Quds.

Yet, Israel imposed Israeli law on the conquered area and since 1967 claimed the holy city has been ‘reunited’ as ‘the eternal Jewish capital’. At the same time, for the nearly 400,000 Palestinians now living in the city, the reality has been very different: a unilateral annexation, in defiance of their right for Palestinian self-determination, followed by massive Jewish colonial settlement. It should be noted that in this area, as opposed to the rest of the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip, Palestinians were awarded a second class ‘resident’ status, which allows them certain rights denied to their Palestinian brethren in the rest of the occupied territories. Yet, the vast majority of Palestinians in the city are not Israeli citizens, and are hence excluded from most spheres of representation, influence and resources allocation.

Our walk takes place in the proximity of the ‘separation wall’ built by Israel as a response to Palestinian terror attacks in the early 2000s. The violent imposition of the wall, with the associated roadblocks, travel restrictions and urban destruction, has severed a previously connected urban fabric (see ), and prevented accessibility to education, employment and essential services for the majority of the residents in the area. This has spawned unbearable difficulties and economic ruin on large populations in the area who were forced to abandon their residences and seek alternative locations (B'tselem Citation2020).

The wall has become a symbol of violent occupation and a living reality in the colonized city of Al-Quds, also known as East Jerusalem (Leunberger Citation2019). Under these circumstances, climbing the wall has become an act of practical and symbolic resistance, and a daring act practiced by Palestinian youth (see ).

Forced displacement from unlivable areas has not meant, however, the removal of Palestinians from the city. Quite the contrary, the Arab ‘Maqdasi’ (Jerusalemite) population has nearly doubled since the erection of the wall. This is because Al-Quds/Jerusalem is not only the symbolic heart of the Palestinian nation and the homeland of long-standing communities, but also a source of everyday livelihood, resources, and familial connection. The main impact of the wall, which mainly separates Palestinian neighborhoods, has thus been to ‘throw-apart’ the Palestinians in their own city.

Zoom out – ‘Thrownapartness’, we observe, is of course not limited to Jerusalem, but increasingly typifies a growing number of cities, many of which are being re-colonized (Abourahme Citation2018). While the older ‘classical’ type colonial rule involved the seizure of territories and subjection of their population as inferior, the new type is often spatially inverted, whereby marginalized groups flock into rapidly expanding metropolitan regions, dreaming of jobs, opportunities and mobility. Al-Quds/Jerusalem harbors both ‘old’ and ‘new’ types of coloniality.

Despite the urban dreams, in vast parts of the urban world the urban new-comers and local marginalized groups are often ‘thrown-apart’, becoming forcibly separated – spatially and politically – as second and third class urban citizens, and hence impoverished, displaceable, disposable, racialized and segregated. They are the subject of the new type of urban coloniality – a condition where long-term relations of ‘separate and unequal’ are created by a combination of harsh top-down identity regimes with ‘softer’ market-oriented mechanisms. The result of these ‘softer’ mechanisms are still highly stratifying, racializing and framed by nearly impregnable commodification and legal frameworks. This is coupled with the on-going discourse of ‘security’ aiming to justify an oppressive, segregated urban order.

In such settings Doreen Massey's (Citation2005, Citation2008) concept of ‘throwntogetherness’, with its dynamic openness, mobility, tolerance, indifference and coexistence (albeit within an exploitive neoliberal political economy and uneven ‘power geometries’), appears like a distant mirage (see also Massey and Hall Citation2015). In times of rapid change, as experienced at present, the intrinsic openness of urban space drives authorities and elites to adopt policies that actively distance groups that may threaten their power, culture and privilege. To complete the conceptual vocabulary initiated by Massey's ‘throwntogetherness’, we offer here to term the reappearance of spatial coloniality as ‘Urban Thrownapartness’.

Clearly, Doreen Massey's concept of ‘throwntogetherness’ did not attempt to construct an ideal picture of urban harmony. Far from it! Massey presented a critical account by employing the term ‘thrown’ alongside ‘together’, as well explained by Ruth Fincher (this Special Feature). In her writings, Massey alluded to the possibility of ‘exclusion through spatial inclusion’; that is, the very nature of urban encounter is shaped not only by the dynamism and fluidity of place, but through ever-present ‘power geometries’ shaped by involved actors. ‘Thrown’ is indeed a powerful reference to the structural forces that shape the imposing circumstances of people's lives, fraught with conflict and oppression, alongside possibilities and hope. Massey highlighted the processes where the very urban proximity often sharpens the hierarchy of urban citizenship, rights and capabilities.

In developing ‘thrownapartness’, we aspire to take Massey's concept a step further, to describe those common urban settings in which the very mixing and spatial dynamics of ‘together’ are limited or even prohibited. Consequently, interactions and encounters are largely prevented by physical, legal and security apparatuses in societies that are often ethnocratic, racist or neo-colonial. Here we note that Massey and Fincher in their conceptualization both relate mainly to immigrant groups, while our angle also incorporates cities populated by large indigenous peoples and national minorities, as common in the global South-East.

Hence, we define ‘thrownapartness’ as a systemic force operating in urban regions to separate spatially, legally and politically the ‘unwanted’ or putatively ‘threatening’ populations, from the dominant elites and allied groups. Such a system is ‘necessary’ in the eyes of urban elites precisely due to the imminent possibility of ‘throwntogetherness’ embedded in the spatial logic of most cities. To combat the urban tendency to ‘throw-together’ populations who share urban space, economy and environment, powerful groups have institutionalized a range of mechanisms to ‘throw-apart’ such groups.

This short essay is not the place to elaborate on these mechanisms beyond pointing to earlier articulations of the concept (Yiftachel Citation2020) as well as to relevant sources within a rich literature. These include a range of urban bordering practices (Yuval-David, Weymyss, and Cassidy Citation2019), ‘gray spacing’ (Yiftachel Citation2009); discriminatory housing policies (Rolnik Citation2020); gated communities, slum clearance the concentration of public, cheap and informal housing in defined and stigmatized ghettos and slums (Davis Citation2005); or the resurfacing of urban coloniality, mainly in the global southeast (Yiftachel Citation2020).

‘Thrownapartness’ is also practiced through legal and cultural control of bodies, dress codes, and housing (Bhan Citation2016), and through the selective denial of services, security and urban rights, highlighted by the ‘biogeopolitical’ logic apparent in the management of Covid19 (Talucci, Brown, and Yacobi Citation2022). We hence suggest that ‘thrownapartness’ and ‘throwntogetherness’ should not be understood as standing in binary opposition, but rather as forces in constant negotiation, creating countless urban assemblages of ‘togetherness’ and ‘apartness’. Both forces exist in most cities, shaped through the circumstances of each urban region. As we show here, and other scholars elsewhere, while some degree of economic and even residential integration does exist in Jerusalem, it is clearly outweighed by the forces of ‘apartness’ and coloniality (Samman Citation2021; Yacobi Citation2015).

Zoom in: The Israeli wall which bisects Al-Quds serves two controlling purposes – to divide Al-Quds from the Palestinian occupied West Bank, and separate ‘Maqdasi’ (Jerusalemite) Palestinians from each other (Leunberger Citation2019). At the heart of this colonial imposition stands the neighborhood of Kufur Aqab, in which certain areas became ‘dismembered’ from the city (see and ).

Figure 5: The Separation Wall (in red) and Jerusalem/Al-Quds municipal boundaries (yellow) at the northern fringe (Source: Btselem Citation2020).

Contemporary Jerusalem/Al-Quds has modernized through periods of ‘classical’ imperial rule by the Ottoman and the British empires. This was followed by Jordanian and Israel conquest and domination. At the same time, since 1967, Israeli rule has attempted to create a façade of a ‘normalized Jerusalem’, in which it hopes non-citizen Palestinians would integrate economically, and accept the urban apartheid created within the city's municipal boundaries (Shtern Citation2016).

In practice, however, the rapid Israeli-Jewish settlement in Al-Quds, and the confinement of Palestinians to limited enclaves, maintains a visible ‘layer’ of classical colonial rule within the ‘united’ city, producing a profoundly hostile urban environment, and as already mentioned, a phenomenon of urban abandonment. Such practices have been documented, inter-alia, by scholars such as El-Atrash (Citation2016), Jabareen (Citation2010), Shlomo (Citation2017), Samman (Citation2021), Tawil-Souri (Citation2018), Yacobi (Citation2016) and Yiftachel (Citation2016). Notably, the recent colonization thrust is not carried out through war and concerted violence, but via the controlling effect of planning regulations, economic development and security regulations, which also offers Palestinians greater (if yet inferior) access to urban resources (Shlomo Citation2017).

Zoom out: This is far from the imagery developed by Doreen Massey and most ‘northwestern’ scholars. Massey draws on the liberal context of Kilburn, London, and contends that ‘throwntogetherness’ is the continuous moment of fluid trajectories of groups and individuals, beliefs and economies, which intertwine in specific time/places (see Massey Citation2005; Citation2008; Massey and Hall Citation2015). These quotidian interactions of diverse populations create what she famously coined ‘a global sense of place’ which is also reflected by the insights offered by, for instance, Gawlewicz, Carta and Fincher in this Special Feature, dealing with cities such as Glasgow, Bologna and Rome, and Melbourne).

Yet, at the northern fringes of Al-Quds, and in hundreds of cities where colonial relations exist, no such moment has come to pass. Quite the opposite – people are routinely ghettoized, excluded and segregated by the Separation Wall and administrative, identity and economic barriers. Kufur Aqab also reveals how ‘throwntogetherness’ may at times of ‘hostile environment’ turn quickly into ‘thrownapartness’ (see Introduction to this Special Feature for a discussion of how these are closely connected).

While the abandoned homes and separation walls in Kufur Aqab are rather extreme manifestations of oppressive urbanism, we contend that in hundreds of cities forces of ‘thrownapartness’ of various degrees of severity are imposed on marginalized groups. These may include evictions, demolitions, confinement to ‘gray spaces’ such as favelas; restriction of movements and accessibility to services, as well as growing practices of digital surveillance and ethno-racial bordering (Abourahme Citation2018; Avni et al. Citation2021). Less extreme versions of these possibilities appear in the insights offered by Bodden and Woods and Kong, as well as Sowgat and Roy in this Special Feature, dealing with cities of Budapest, Singapore and Dhaka, respectively.

Therefore, we contend that in order to more fully fathom contemporary urbanism, scholars have to conceptualize a whole range of possibilities, encompassing thrownapartness and throwntogetherness. As Massey (Citation2005) pointed out, the ‘trajectories’ of migration, development, place and urban dynamics are constantly re-organized in place. We suggest that, conceptually, cities deal simultaneously with conflicting trajectories of throwntogetherness and thrownapartness.

Zoom in: Following the construction of the wall in 2004-2005, Kufur Aqab experienced rapid change. Urban planning and associated regulation, as practiced the previous four decades by the (Jewish) municipality, stopped functioning. This has opened the way for rapid unauthorized construction of high-rise residential buildings, now accommodating around 40,000 people.

Local groups and developers have seized land in the area, at times against the wishes of land owners, and constructed several massive projects. They offer relatively cheap (and often shoddily built) apartments, providing an alternative for residents displaced from the nearby wall areas, mainly Bir Nabala, Dahyat and Kufur Aqab (marked on ), and for immigrants from the West Bank lured by the proximity of Jerusalem. This massive construction (see ) saw the area's population rise within a decade from 70,000 to over 110,000 in 2020, in what is rapidly turning into a vertical slum.

Figure 7: Massive unauthorized, unplanned, high-rise development in northern Kufur Aqab (Photo: Huda Abuzaid).

As noted, a central, yet largely under-documented consequence of colonial rule has been the abandonment of hundreds of homes. Long term homeowners in the area, caged in by walls, checkpoints and deteriorating living standards, find no option but to flee unlivable areas and leave behind their most cherished and valuable possession – their homes.

Abandonment is always declared by Palestinians as temporary. Nearly all plan to return, and often maintain their property while living elsewhere – most commonly in the new high-rise buildings or in nearby areas. Palestinian existence thus resembles the ‘permanent temporariness’ which is a hallmark of the ‘gray spacing’ process (Yiftachel Citation2016), through which urban domination is maintained over marginalized groups.

The challenges of ‘thrownapartness’ are amplified by the Palestinian ethics of resistance, endurance and survival which help sustain the state of flux. Resilience works to routinize the suffering inflicted on them by this hostile environment. It enables Palestinians to endure lawlessness, lack of services, de-development, dirt, lack of public spaces, neglect and blight.

Finally, starkly illustrates collective and individual ‘thrownapartness’. Palestinians as a group are separated from Jews in the western city, and from Palestinians in the West Bank, by a range of planning, legal and economic practices. Individually, they are separated from one another, due to the system of walls, gates, roadblocks and tight surveillance. We suggest that while capitalist-liberal urbanization is indeed based on ‘throwntogetherness’, in most urban regions the oppressive forces of ‘thrownapartness’ are active at the very same place and time.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the insightful comments received by co-editor Anna Gawlewicz and City's editorial team. Above all, we acknowledge the ‘sumood’ (steadfastness) of the Palestinians in Al-Quds who are still struggling to attain their basic rights in al-Quds/Jerusalem and elsewhere in their homeland.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Huda Abuzaid

Huda Abuzaid is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Geography and Environmental Development at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. Email: [email protected]

Oren Yiftachel

Oren Yiftachel is Professor in political geography, urban planning and public policy at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. Email: [email protected]

References

- Abourahme, N. 2018. “Of Monsters and Boomerangs: Colonial Returns in the Late Liberal City.” City 22 (1): 106–115. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2018.1434296.

- Avni, N., N. Brenner, D. Miodownik, and G. Rosen. 2021. “Limited Urban Citizenship: The Case of Community Councils in East Jerusalem.” Urban Geography, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1878430.

- Bhan, G. 2016. In the Public's Interest: Evictions, Citizenship, and Inequality in Contemporary Delhi. Atlanta: University of Georgia Press.

- Btselem. 2020. “The Separation Barrier.” https://www.btselem.org/separation_barrier.

- Davis, M. 2005. Planet of Slums. Los Angeles: Verso.

- El-Atrash, Ahmad. 2016. “Implications of the Segregation Wall on the Two-state Solution.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 31 (3): 365–380. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2016.1174594.

- Jabareen, Yosef. 2010. “The Politics of State Planning in Achieving Geopolitical Ends: The Case of the Recent Master Plan for Jerusalem.” International Development Planning, Review 32 (1): 27–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2009.11

- Leunberger, C. 2019. “The Politics of Mapping the West Bank Barrier.” Brown Journal of Foreign Affairs 25 (2): 7–24. https://bjwa.brown.edu/25-2/the-politics-of-maps-mapping-the-west-bank-barrier/.

- Massey, Doreen. 2005. For Space. London: Sage.

- Massey, D. 2008. “A Global Sense of Place.” In The Cultural Geography Reader, edited by T. Oakes, and P. Price, 70–77. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Massey, D., and S. Hall. 2015. After Neoliberalism? the Kilburn Manifesto. London: Stewart Wishart.

- Rolnik, R. 2020. Urban Warfare: Housing Under the Empire of Finance. London: Verso.

- Samman, M. 2021. “From Moments to Durations: The Impact of Israeli Checkpoints on Palestinian Everyday Life in Jerusalem.” International Journal of Urban Sciences 25 (1): 124–148. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2020.1777892

- Shlomo, Oren. 2017. “The Governmentalities of Infrastructure and Services Amid Urban Conflict: East Jerusalem in the Post Oslo Era.” Political Geography 61: 224–236. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.09.011

- Shtern, M. 2016. “Urban Neoliberalism vs. Ethno-National Division: The Case of West Jerusalem's Shopping Malls.” Cities 52 (5): 132–139. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.11.019

- Talucci, G., G. Brown, and H. Yacobi. 2022. “The Biogeopolitics of Cities: A Critical Enquiry Across Jerusalem, Phnom Penh, Toronto.” Planning Perspectives 37 (1): 169–189. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2021.2019608.

- Tawil-Souri, H. 2018. “‘Exopolis’ - Between Ramallah and Jerusalem.” In Beyond the Square, edited by D. Sharp, and C. Panetta, 44–63. New York: Urbanism and the Arab Uprising. https://www.academia.edu/28993973/.

- Yacobi, H. 2015. ““Jerusalem: From a “Divided” to a “Contested” City – and Next to a Neo-Apartheid City?” City 19 (4): 579–584. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1051748

- Yacobi, H. 2016. “From Ethnocracy to Urban Apartheid.” Cosmopolitan Civil Societies An Interdisciplinary Journal 8 (3): 100–114. doi: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v8i3.5107

- Yiftachel, O. 2009. “Theoretical Notes on ‘Gray Cities’: the Coming of Urban Apartheid?.” Planning Theory 8 (1): 88–100. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095208099300

- Yiftachel, O. 2016. “Aleph—Learning from Jerusalem.” City 20 (3): 483–494. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2016.1166702

- Yiftachel, O. 2020. “From Displacement to Displaceability.” City (Special Relaunch Issue) 24 (1–2): 152–165. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2020.1739933.

- Yuval-David, N., G. Weymyss, and K. Cassidy. 2019. Bordering. London: Wiley.