I don’t predict the future. All I do is look around at the problems we are neglecting now and give them about 30 years to grow into full-fledged disasters. (Octavia Butler, Citation2000)

We have officially entered our third year of the global pandemic with no indication that transmission of the deadly virus will wane anytime soon. As of January 2022, the global death toll surpassed 5.5 million, however as some data scientists have argued, this figure is grossly underestimated without accounting for excess mortality—‘a metric that involves comparing all deaths recorded with those expected to occur’ (Adam Citation2022, 312). Prevailing data that show that COVID continues to disproportionately kill poor, racialized minorities worldwide—highlighting stark inequities of health along class, racial and ethnic lines. The impact of the pandemic has extended beyond concerns about health since we have seen a spate of developments occur that disproportionately affect marginalized populations all over the globe. We are witnessing an expansion of segregation, poverty, unemployment, and homelessness via evictions, while racial and class-based disparities in education access continue to plague the world’s most vulnerable people. The impact of this global crisis has shifted our sense of the world, and our relationship to public and private spaces. We are seeing the effects of the privatization of social reproduction, and uneven patterns of (im)mobility, especially as the exploitation and devaluation of racialized and feminized care labor has been intensified. In other words, the global pandemic has exposed what gets invisiblized via processes and practices associated with racial capitalism, gentrification and neoliberal urbanism. Now in 2022, we are still in the throes of what David Madden (Citation2020) described in a previous City editorial as ‘Covid capitalism’—one that is exhibited through crisis, austerity, risk and authoritarianism. In so many ways, the pandemic is shining a light on social fabrics and urban processes that were being eroded by gentrification, making room for platform mediated exchanges. The ‘smart’ and ‘resilient’ cities are not necessarily ‘just.’ In other words, the pandemic has effectively accelerated disruptive processes already in progress.

I live in the United States, and when the city of Berkeley (California) enforced the first lockdown of the pandemic in March 2020, I decided to revisit some of my most favorite and captivating science fiction novels. I poured over fantastic(al) stories by Octavia Butler, China Mièville, N. K. Jemison, and Nnedi Okorafor. I decided to read Max Brooks’ World War Z because I wanted to better understand what was happening, but most importantly, what future we were poised to enter. Like in World War Z, it became clear that the pandemic had exposed faulty infrastructure and bad policy. Most notably, the pandemic exacerbated miscommunication between nations, xenophobia, greed, poverty, destitution, and the survival of capitalism through it all. Naturally, this deep dive into the dystopian worlds delicately constructed by some of our most creative literary thinkers got me thinking about how to digest the spectral images I saw on social media—empty amusement parks (in Los Angeles), desolate central business districts (in London), bountiful waterways reclaimed by wildlife (in Venice), residential apartment buildings engulfed by flames (in New York) (see ).

To my mind, our haunted reality has become completely aligned with, and perhaps more jarring than fiction. Stories about ‘ghost kitchens’ and ‘dark stores’ solidify city life as part of ‘urban capitalist simulacra’ (Summers Citation2019, 3), a Baudrillardian simulated ‘reality,’ conscripted by technological hegemony. Dark stores are fulfillment centers used by delivery apps as storage facilities that are not open to the public, but most often take up commercial space. Ghost kitchens are virtual restaurants, or meal-preparation facilities that are untethered from physical restaurants. These spaces, often located in commercial districts, require significantly less labor and curb overhead costs associated with running a brick-and-mortar establishment. Dark stores and ghost kitchens existed before the pandemic, but are taking on new forms given the accelerated demand for deliveries (thus expanding the market for third-party online delivery providers like DoorDash, UberEats, and GrubHub). Both also contribute to a city that has been overrun by laborers in motion, navigating the city as they deliver goods to people who can afford to order from the technology companies that barely pay the laborers’ minimum wage. At the same time, these shadowy spaces presume human, or consumer absence.

Our entrance into the post-industrial economic landscape has been punctuated by a political economy of ghoulish geographic absence and liminality. Urbanists have previously characterized neoliberalism, and by extension, neoliberal urbanism, as undead (Peck Citation2010; Peck, Theodore, and Brenner Citation2013; Aalbers Citation2013). In fact, Manuel Aalbers (Citation2013) identifies neoliberalism as a ‘zombie’ (Citation2013, 1089), making room for us to consider a kind of ‘zombie capitalism’ that is not alive, ‘but somehow fantastically continues and threatens to destroy the existing economic order’ (Tabb Citation2014, 97). It is in cities that both growth and decay exist in the same spaces at the same time. The proliferation and exacerbation of platform urbanism makes sense in the COVID era, with the pandemic mapping easily onto the social order of financial capitalism. This is inherently tied to uses of space. As Matthew Soules (Citation2021) writes, one of the byproducts of financial capitalism’s focus on asset value over use value is the underuse of architectural space (zombie urbanism) and unoccupied real estate (ghost urbanism). Phantasmal forms of contemporary urbanism have flipped the organizing terms and images of blight, decay, and ruin to signal vitality and economic growth. Historically, urban spaces designated as blighted and uninhabitable have been some of the prime areas where poor, immigrant, and racially marginalized people have and continue to live. Zombie urbanism is trenchant under-occupancy in areas that ‘mix present populations with [presumably] absent populations, exhibiting eerily low levels of vitality in relation to their scale’ (Soules Citation2021, 51). Ghost urbanism, on the other hand, is exhibited by the dramatic proportion of vacant, or unfinished units ‘in the context of a perceived crisis’ (Soules Citation2021, 51). Both modes of ethereal urbanism haunt cityscapes across the world; littering urban landscapes with architectural carcasses that concretize the material excesses of greed and plunder.

Intrepid urbanism

The world doesn’t first need to burn itself to the ground; rather a mash-up culture can emerge as a natural progression of our inter-connectedness as the more affluent further distance and isolate themselves from the rest of us. This emergent, mash-up culture is often set, in my work, against a backdrop of intensifying extremes, where the lines between public and private become blurred, a societal obsession with quantification and measurement is magnified, and an abiding faith in technology arcs us toward a world of total surveillance; spatial and linguistic segregation; and a rabid and insidious, all-consuming capitalism, in which even basic human interactions are commodified. (Jeyifous Citation2017)

I’ve been thinking quite a bit about urban futures lately, and the space that the current crises (economic, social, political, environmental, supernatural) have opened. Crisis, according to Ruth Wilson Gilmore, is ‘instability that can be fixed only through radical measures, which include developing new relationships and new or renovated institutions out of what already exists’ (Citation2007, 26). The pandemic has made visible failures across supply chains, health care systems, and labor conditions. Yet, it is oftentimes through failure that we can imagine distinct possibilities.

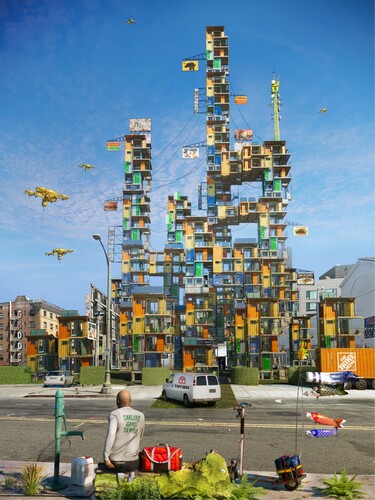

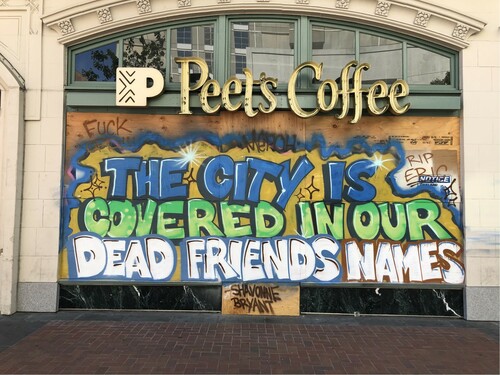

Nigerian-born artist and architect Olalekan Jeyifous creates worlds that arise from ‘the failure of urban development to adequately consider the needs or even the existence of marginalized communities’ (Jeyifous Citation2017, 140). Jeyifous contends that economically deprived and politically marginalized groups effectively build community that materializes ‘in the voids and negative spaces, in the interstices between, or at the periphery of, affluent commercial and private development’. This in spite of the fact that they often lack adequate access to everyday amenities (Citation2017, 140). It is in response to crisis and failure that these communities enact innovative and sustainable practices, or what I’d call intrepid urbanism (see ). Through crisis and failure, people engage in various forms of adaptation, a resourcefulness that is ‘achieved not by design but out of necessity’ (Jeyifous Citation2017, 141). We have witnessed individuals take up acts of repurposing, in response to crisis and failure, re-engineering urban materials for alternative use. One of my favorite examples is the innovative design of ‘frankenbikes’—vestiges of an over-supplied, over-wrought bike-share system—utilized by under-resourced, unsheltered populations in cities like Los Angeles and Seattle (Leszczynski and Elwood Citation2022). Finally, through crisis and failure, people have forged alternative terms of belonging through reclamation. While many cities have adopted presumably sustainable planning and design features (e.g. open streets, slow streets, parklet restaurants), since the onset of the pandemic, to make streetscapes more accessible, it has been through widespread social unrest and public demonstrations that insurgent expressions of place have become visible through public art and performance (Carastathis and Tsilimpounidi Citation2021; Summers Citation forthcoming) (see ).

It is from this perspective that I think we need to retool the urban imagination of the post-COVID era, and draw on adaptation, repurposing, and reclamation as a layered, global practices—ones that compel us to think about the past, present and possibilities for the future simultaneously. This double issue of City does exactly that.

Past: Crises (as well as hopes) of the present have historical roots. In his consideration of the materiality of history, memory and mythic violence through the casting of symbols, Vincenzo Ruggiero contests the intransigence of historical linearity by discussing struggles over urban symbolic forms and the organization of time in urban space. Each of the articles in the Special Feature on ‘Gentrification Through the Ages’ intricately point to the importance of unfixing our perspectives of gentrification as a contemporary phenomenon, to embrace its longer and more variegated history. As Tim Verlaan and Cody Hochstenbach point out in the introduction of the Special Feature, such insights enliven debates long believed to be settled about primary actors, institutions, scales, and locations that have shaped gentrification processes.

Present: In their accounting of the urban present, Ross Beveridge, Markus Kip, and Heike Oevermann consider how Berlin’s urban wastelands help us better understand the development of cities. Urban voids, for them, are presumably empty spaces within which lie interminable possibilities for the future. Their exploration of urban voids as ‘waiting lands’ reminds me of what Dan Hill (Citation2020) describes as ‘slowdown landscapes.’ For Hill, urban wastelands ‘provide useful prompts, through their indeterminacy, openness, blankness, scrappy at-hand adaptability, fallow condition, and not least the resilience and diversity of their intransigent flora’ (Hill Citation2020). Similarly, the articles that comprise the Special Feature on ‘Throwntogetherness’ highlight present-day intrepid practices of ‘resilience and triumph’ that, as Jeyifous suggests, ‘emerge from fundamentally antagonistic environments’ (Citation2017, 141). In contrast to the enduring legacies of ‘thrownapartness’—institutionalized through forced segregation, displacement, and urban apartheid, it is through contemporary manifestations of disparate groups, environments, materialities and imaginations being thrown together, that true agentic possibilities emerge.

Future(s): Questions of sustainability are always organized around a commitment to the speculative future. To that end, Karl Krähmer tackles questions about urban transformation and ecologies of sustainability through the implementation of degrowth strategies. In their article, Austin Zeiderman and Katherine Dawson chart how urban ‘future-thinking’ and ‘future-making’ have been conceived both in the past and the present-day in order to better make sense of our future trajectories.

Both Special Features and the individual submissions to this double issue recast the past in a new light. They invite us to ask important questions about how we can truly build auspicious, inclusive futures. At the same time, as the intellectual provocations about the past, present, and possible futures that are published in this issue center analyses from white, Western, and mostly male scholars, we, as an editorial collective, acknowledge what Samantha Thompson highlights in her review of Akira Drake Rodriguez’s brilliant new book, Diverging Spaces for Deviants: that racial capitalism is rooted in histories of uneven urban development, most often enacted by displacing and dispossessing poor, immigrant, and racialized minorities.

While we don’t know if or when the global pandemic will dissipate, or even disappear, it is the haunted afterlife of our COVID conjuncture that elicits the most fear, but more importantly, emerging promise.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aalbers, M. B. 2013. “Neoliberalism is Dead … Long Live Neoliberalism!.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37 (3): 1083–1090. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12065

- Adam, D. 2022. “The Pandemic’s True Death Toll: Millions More Than Officials Count.” Nature 6011: 312–315. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-00104-8 doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-00104-8

- Butler, O. 2000. “Brave New Worlds: A Few Rules for Predicting the Future.” Essence 31 (1): 164–166, 264.

- Carastathis, A., and M. Tsilimpounidi. 2021. “Against the Wall: Introduction to the Special Feature: Inscriptions of ‘Crisis’: Street Art, Graffiti, and Urban Interventions.” City 25 (3–4): 419–435. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2021.1941659

- Gilmore, R. W. 2007. Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hill, D. 2020. Mood-worlds of the Slowdown. Slowdown Papers. https://medium.com/slowdown-papers/33-slowdown-landscapes-the-mood-worlds-of-the-slowdown-3985f7f6f081.

- Jeyifous, O. 2017. “The Abiku Phenomenon.” Agni 85 (1): 129–141. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44984101.

- Leszczynski, A., and S. Elwood. 2022. “Glitch Epistemologies for Computational Cities.” Dialogues in Human Geography. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206221075714.

- Madden, D. 2020. “The Urban Process Under Covid Capitalism.” City 24 (5–6): 677–680. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2020.1846346

- Peck, J. 2010. “Zombie Neoliberalism and the Ambidextrous State.” Theoretical Criminology 14 (1): 104–110. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480609352784

- Peck, J., N. Theodore, and N. Brenner. 2013. “Neoliberal Urbanism Redux?” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37 (3): 1091–1099. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12066

- Soules, M. 2021. Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra-Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Summers, B. T. 2019. Black in Place: The Spatial Aesthetics of Race in a Post-Chocolate City. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Summers, B. T. forthcoming. “Black Insurgent Aesthetics and the Public Imagination.” Urban Geography.

- Tabb, W. K. 2014. “The Wider Context of Austerity Urbanism.” City 18 (2): 87–100. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2014.896645