Abstract

This paper adopts an empirical focus on the everyday practices of Take Back the City, a housing activist campaign in Summer 2018 in Dublin, as an illustration of occupations as digital/material contention. It outlines how the temporary political occupations of vacant buildings were organised and unfolded across a digital/material nexus. I argue that reading occupations as digital/material (a) extends understandings of how urban struggles actually take place in contemporary cities, and (b) highlights the central role of the digital in contentious space-times before, during, and in the wake of temporary political occupations. I use the Take Back the City campaign to explore the relationship between urban spaces, digital technologies, and contemporary housing movements. Echoing recent work on radical urban space-times, I emphasise the digital/material practices and temporalities of the Take Back the City campaign as a useful example for research on the makeshift, improvised, and often uncertain ways in which digital technologies and urban space are now enrolled in struggles over housing futures.

Introduction: temporary political occupation and the space-times of digital/material contention

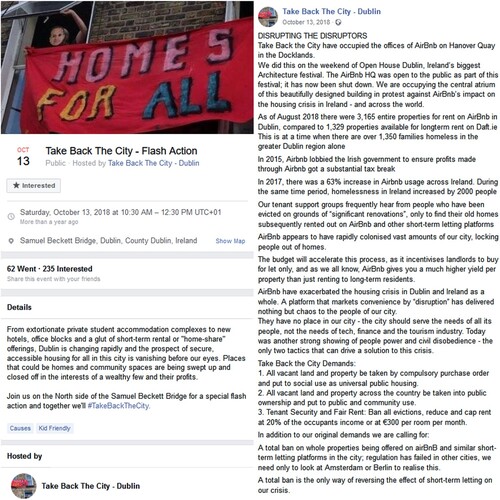

In October 2020, a group of activists ‘occupied’ the lobby of Airbnb's European headquarters in Dublin's docklands (see ). Airbnb's presence in Dublin is controversial. The company's choice of headquarter location symbolises the city's position within globalised and financialised networks of tax avoidance. Its presence also highlights the profound contradictions of on-going housing and homelessness crises in a city branded as a tourist destination of international significance.

Figure 1: Take Back the City occupy Airbnb headquarters—image collected through digital ethnography of Take Back the City Facebook page, posted publicly on 13th October 2018. Note faces are blurred here by the author.

The occupation lasted less than two hours but briefly trended on Irish Twitter and was covered by national media. I wasn't there, although I’d been conducting participant observation and digital ethnography researching Take Back the City—Dublin (hereafter TBTC), the housing activist coalition involved. Mostly my absence was because I’d spent the preceding weeks at what had felt like an endless succession of housing activist meetings, demonstrations, and protests. I was invited via Facebook to a ‘flash action’ assembling at a specific bridge on Saturday morning the week before but I was tired, I was in the final weeks of writing a particularly long and onerous funding application, and I succumbed to what had become a sort of fascinated but slightly guilty habit during my research—I watched some of the event through a Facebook livestream while working on my funding application. I left a Firefox tab open on the livestream for maybe 10 minutes, and occasionally switched from Microsoft Word to view the slightly choppy unfoldings of the action, which mainly consisted of about a dozen housing activists standing in the lobby of the Airbnb building with a banner decrying the company's involvement in ongoing housing/homelessness crises, some chanting, short speeches, and the bemusement of onlookers, who had presumably been in to view the building as part of a wider ‘open doors’ architecture event taking place in the city that weekend. I watched others ‘comment’ on the livestream, praising the organisers and often noting how the commenter wished that they could be ‘there’. Eventually, I closed the tab because it felt disappointing and a bit surreal to be watching the short-lived occupation via livestream.

I begin with this short account of a TBTC action which I livestreamed because it captures a sense of how the campaign, like many others, plays with the time-spaces of occupation and digital/material dynamics of presence and experience during and after occupations. Contemporary urban activism often unfolds as digital/material in real time (i.e. as it is happening), but this digital/material character diffuses the spatio-temporal reach of struggle to those who are not ‘there’ in space and/or time. I argue that a digital/material reading extends understandings of how urban struggles actually take place in contemporary cities, which is of practical and academic interest. A digital/material reading also highlights the central role of the digital in contentious space-times before, during, and in the wake of temporary political occupations, which scholar-activism can benefit from highlighting as a question that impacts the emotional and practical labour of collective struggles. Work on power, space, and temporality captures the nomadic or ‘pop up’ nature of resistance within the more rigid fixity of the status quo (de Certeau Citation1984; Watt Citation2016). Critical urban geographers have called for more nuanced understandings of the temporalities of urban interventions, building from work on temporary urbanism (e.g. Ferreri Citation2015, Citation2021) to attune to ‘interim’ or ‘makeshift’ (Tonkiss Citation2013) urban activisms ‘beyond the chimera of permanence’ (Till and McArdle Citation2015). The paper seeks to add to this emergent literature, inspired by Rachel McArdle's work on ‘liquid urbanisms’ (Citation2019), which use post-crash Dublin as a case study to highlight how 'short-term, provisional, radical uses of urban space challenge the idea of permanency in the city that we associate with urban planning periods or the movement of capitalist investment’ (Citation2022, 633). Here, my focus on temporary political occupations furthers this sense of the impermanent space-times of urban resistance. I use the TBTC case study to draw work on the spatio-temporalities of urban activisms into dialogue with work on the intertwining of the digital/material in contemporary resistance, and the paper extends existing work by attending to the often unexamined function of digital technologies in struggles for an alternative city. In doing so, I connect work on the temporality of ‘pop-up’ and temporary urban activism (Watt Citation2016; McArdle Citation2022) to a reading of temporary political occupations as code/spaces (Kitchin and Dodge Citation2011). In this reading, contentious spatialities and uses of software are mutually constituted, and digital technologies (and particularly social media) are seen to play a key role in how occupations are publicised, co-ordinated, and mediated.

Methodologically, the paper draws from digital ethnographic data collection focused on the social media accounts of housing activist community groups in post-crash Dublin, one of which was TBTC. This was part of a wider project which ran from 2018 to 2022 and collected social media and interview data about three temporary political occupation campaigns in post-crash Dublin—these were the Bolt Hostel in 2015, Apollo House/Home Sweet Home in 2016, and TBTC in 2018. The project combined digital ethnography, participant observation/observant participation, and interviews to understand how activists have used digital technologies to contest housing. The paper draws from the first and second of these data collection methods, through which I experienced my research, echoing methodological literature, as both ‘a messy fieldwork environment that crosses online and offline worlds’ (Mare Citation2017, 647) and a ‘blended cohabitation’ in housing activists’ digital/material urban landscapes (Bluteau Citation2021). My most active period of participant observation coincided with TBTC, over the course of which I attended 11 events (mostly rallies, workshops, and marches) organised around the occupations as an observant participant/participating observer, and closely monitored how the campaign unfolded over social media and in news coverage (drawing from digital ethnography). In doing so, I ‘lived’ TBTC as an intense and inspiring period, but began to see how the temporalities and geographies of the campaign's occupations were undergirded by digital/material practices and labour. To explain this dynamic, the paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, I situate the TBTC case study within literature on post-crash urban activism and digital geographies. In the following section, I outline the digital/material practices and temporalities of TBTC's temporary political occupation campaign, and highlight the central role that digital technologies in general and social media in particular played in publicising, organising, and mediating the campaign. I conclude by reflecting on temporary political occupations and the digital/material possible in post-crash cities.

Post-crisis contestation: digitally/materially asserting a right to the city

In the wake of the 2007/2008 financial crisis, interpretations of contention and resistance have grappled with their urban dimensions (Mayer, Thörn, and Thörn Citation2016) and the role of so-called rebel cities (Harvey Citation2012). Struggling to keep pace with developments ‘on the ground’, an outpouring of scholarship in the decade since the 2007/2008 crisis has sought to make sense of the distinctly and simultaneously urban and digital dimensions of struggles in which temporary political occupation placed a central role (e.g. Harvey Citation2012; Halvorsen Citation2015), and how these have evolved following the end of occupation, for example, in #Occupy and the European 'squares' movements (e.g. Martínez-Lopez and Bernardos Citation2015). For critical urban geographers and activists (see, e.g. Merrifield Citation2011; Marcuse Citation2009), Lefebvre's work on ‘the right to the city’ has been a useful way of understanding urban struggles as ‘a cry and a demand … [through which the right to the city] can only be formulated as a transformed and renewed right to urban life’ (Lefebvre Citation1996, 158). Influentially, Margit Mayer (Citation2009, 367) frames the right to the city as ‘less a juridical right’ than ‘an oppositional demand, which challenges the claims of the rich and powerful … It is a right that exists only as people appropriate it (and the city)’. This highlights the emergent, collective, and practical character of struggles asserting a/the right to the city. With this practical character in mind, this paper echoes calls to extend, or go ‘beyond’ (e.g. Merrifield Citation2011), a right to the city framing. To this end, I use TBTC to highlight the digital/material character of how oppositional demands are enacted through collective and contentious practices in contemporary urban struggles.

Here, I draw from digital geographies research and particularly Leszczynski’s (Citation2015) argument that urban space, and spatiality more generally, is ‘always-already mediated’. In this reading, spatiality is a nexus of socio-spatio-technical relations. These continuously unfold and evolve through the ‘contingent, necessarily incomplete comings-together of technical presences, persons, and space/place’ (Leszczynski Citation2015). Writing from a legal perspective, Julie Cohen (Citation2007, 252) notes that this ‘emergence of technical sites for the spatial production of power also constitutes new regulatory and political processes’. Geography as a subject is said to be undergoing a number of digital turns (Ash, Kitchin, and Leszczynski Citation2018). Digital geographies approaches to activism have used spatial media and geo-locatable data to ‘map’ contentious movements (e.g. Shelton Citation2017), and highlighted an upsurge in activism on/through digital issues, platforms for participative democracy, and technological sovereignty (e.g. Shaw and Graham Citation2017). An emergent literature on feminist digital geographies has brought a useful recognition of embodiment, affect, and labour (e.g. McLean, Maalsen, and Prebble Citation2019). This can be usefully put in dialogue with social movement and critical communication studies research, which has more directly engaged with the broader adoption of digital technologies by activists ‘as a quotidian and ubiquitous aspect of social movement communication processes across a wide range of issues not directly related to digital media’ (Flesher Fominaya and Gillan Citation2017, 393–394). This ubiquitous and often mundane or unremarkable character of the digital has been recognised in digital ethnographic research, which Hine (Citation2015) describes as a movement from ‘virtual ethnography’ towards an understanding of the digital as embedded, embodied, and everyday. Within existing work on post-crisis temporary urban political occupations, this relationship between the digital/material becomes difficult to avoid discussing. Critical urban geographers discuss occupation-based movements with terms like ‘the spatialization of democratic politics’ (Kaika and Karaliotas Citation2016), ‘urban solidarity spaces’ (Arampatzi Citation2017), or ‘material and virtual public spaces’ (Leontidou Citation2012). However, this literature tends to reinforce a sense of the digital and the material in dichotomy—either space, place, and ‘the streets’ are where the online ‘moves to’ and then either ‘represents’ or occurs as ‘non-mediated’ (Harvey Citation2012; Tufekci Citation2017), or ‘the material and virtual’ (Leontidou Citation2012) occur as a hybrid ‘cyberspace-space’. As noted by Leszczynski (Citation2015), this is ‘incommensurate with the established intellectual lineage that has conceptualised spaces as either relational, or, as has been more recently suggested, ontogenetic’ (745), and an emphasis on the spatial as an always incomplete becoming rather than a completed or fully-formed ‘being’ hybrid.

Consequently, in this paper, I highlight the broader point, applicable across many contexts and cases, that contemporary housing activists are influenced by and influence a more sweeping enrolment of digital technologies in everyday life (Kichin and Fraser Citation2020). This can occur as an inadvertent or unremarked upon feature of how contemporary activism is done, rather than because organisers necessarily set out to be technologically adept or conceive of their usage of digital technologies as inherently or exclusively ‘activist’. This extends understandings of contemporary housing activism beyond a brief note that ‘activists use social media’, and adds a detailed account of the mundanity of activists’ digital/material tactics. The mundane character of digital/material tactics should be understood as intertwined with what an emerging literature has discussed as the sophisticated enrolment of digital tools and technologies by housing activists, with a particular focus on anti-gentrification and displacement struggles (e.g. Akers et al. Citation2019; McElroy and Vergerio Citation2022). Accordingly, the paper's core argument is that contemporary housing activism often involves both spectacular and mundane enrolments of digital/material tactics, but this tends to be unremarked-upon or taken-for-granted when technology is not the specific focus of scholarly investigation. More specifically, the paper demonstrates how temporary political occupations unfold through simultaneously digital/material tactics. I suggest that this digital/material character can spatially and temporally extend occupations’ impacts to those who are not ‘there’, either at the time or in-person, and attuning to the digital/material extends scholarship on temporary political occupations, urban struggles, and their temporality.

The digital/material practices and temporalities of taking back the city

Understanding and thinking with temporality requires both a context and a set of tools to make sense of it. The case I use here is TBTC, a housing activist campaign unfolding in the context of post-crash Dublin. I use detailed digital ethnographic study and field work to describe how TBTC functioned as a code/space. Code/space is Kitchin and Dodge’s (Citation2011) term for when software and space are essential to the functioning of a space (and its social relations). I use the term post-crash to situate TBTC within the wider reading of how Ireland, and particularly its capital city Dublin, has been shaped by the global financial crisis of 2007/2008 and its aftermath. Ireland was profoundly impacted by the global financial crisis—in its wake, Irish austerity policies have amplified existing inequalities and been justified through what O’Callaghan et al. (Citation2015) describe as a ‘twin pillar’ narrative of property and debt. This narrative, constructed through collective blame and shame, has been used to legitimise austerity, and the reignition of property markets has symbolised economic recovery while deepening urban and housing financialisation (O’Callaghan and McGuirk Citation2020). The Irish experience of the financial crash was shaped by a pre-2007 property price bubble, and post-crash property market recovery has been nationally uneven. In Dublin in particular a combination of state policies towards tax, investment, and the disposal of ‘distressed asset’ property ‘portfolios’ have facilitated the influx of speculative international financial capital seeking favourable returns on post-crash investments (Byrne Citation2015). In turn, this has contributed to new and on-going housing and homelessness crises in the city, stemming from unchallenged structural and systemic problems within Ireland's neoliberal housing system (Hearne Citation2020).

Here, the Dublin case study can be usefully put in dialogue with work on post-crash housing activism in other indebted western European countries, often referred to as the so-called PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain). In particular, similarities and differences between Ireland and Spain highlight three of the key dynamics of post-crash urban struggles and how they have unfolded in specific contexts. Firstly, while Martínez-Lopez and Bernardos (Citation2015) describe a ‘convergence’ of two social movements (the occupation of squares and squatting of buildings), Dublin's post-crash urban activism ‘scene’ has been more divided. Occupation tactics have mainly been used in three strands of struggle in the city. An initial ‘Occupy’-inspired movement to ‘Occupy Dame Street’ was followed by a flourishing of ‘independent spaces’/social centres, some of which were squatted (see Bresnihan and Byrne Citation2015; McArdle Citation2022), and by housing activist occupations offering temporary emergency accommodation for the homeless (O’Callaghan, Di Feliciantonio, and Byrne Citation2018; Di Feliciantonio and O’Callaghan Citation2020). Although there were some overlaps of people and significant places between these two later strands, ‘independent spaces’ tended to be less overly political than housing activist occupation, and generally focused on cultural uses rather than political confrontation (though see McArdle Citation2019 on the politics of cultural uses).

Secondly and relatedly, this ‘convergence’ of movements in Spain was closely connected to the evolution of the PAH (Platform of People Affected by Foreclosures, Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca) and its ‘recuperation’ of foreclosed properties for social centres but also dwellings against the backdrop of Spain's ‘housing dispossession crisis’ (Yrigoy Citation2020). In Ireland, by contrast, while mortgage arrears and default rates increased with the onset of the crash, repossession rates on mortgages in arrears have been low, particularly for owner-occupiers. Hearne et al. (Citation2018, 158) contrast the limited extent of repossessions in Ireland with the extent and volume of foreclosures in Spain between 2008 and 2014. This was a key organising issue for the PAH but less common in Ireland. Finally, the PAH in particular played a central role in inspiring what Hearne et al. (Citation2018, 160) describe as ‘a range of new tactics and strategies’, with a 2014 workshop where Dublin housing activist groups hosted guest speakers from the PAH being an important overlap between the two. Significantly, Dublin housing activist groups attempted to adapt the PAH's affected-led organisational practices with the aim of enacting new collective political subjectivities in Dublin (see e.g. Di Feliciantonio and O’Callaghan Citation2020). However, rather than mobilising around indebtedness and foreclosure (García-Lamarca Citation2017), post-crash housing activism in Dublin has evolved from an initial focus on the city's growing homeless population towards a more expansive critique of housing financialisation, and particularly inequalities in the private rental sector (Byrne Citation2019). Throughout, temporary political occupations of vacant urban spaces have been a recurring tactic, with high-profile occupations of vacant buildings being used to stage political confrontation (O’Callaghan, Di Feliciantonio, and Byrne Citation2018; Di Feliciantonio and O’Callaghan Citation2020). Typically this is done with the understanding that occupation will be short-lived and subject to legal challenge (which I discuss below), rather than a lower-profile practice of dwelling. It is within this context that TBTC should be understood, unfolding a decade after the 2007/2008 financial crisis and what Hearne et al. (Citation2018) describe as two earlier phases of post-crash housing activism in Ireland.

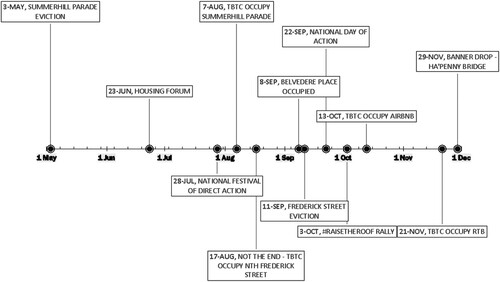

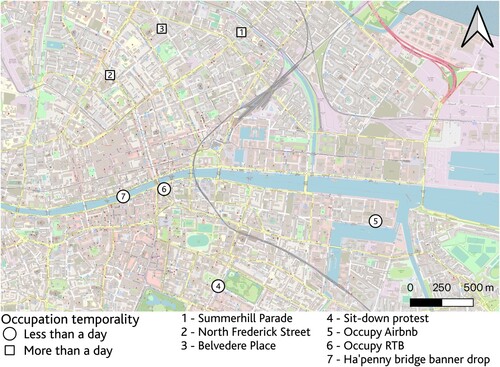

The TBTC campaign organised a series of rolling temporary occupations of vacant properties in Dublin's inner city throughout August and September 2018 (see and ). Three subsequent ‘pop-up’ actions and events followed the campaign's eviction from the second of the three buildings that they occupied (on North Frederick Street).

Figure 2: Timeline of TBTC, from May to December 2018—author's own, created to reflect digital ethnography and participant observation.

Figure 3: TBTC occupations—author's own, created to reflect digital ethnography and participant observation. Base map from Open Street Map, © Open Street Map Contributors. Note that square symbols are longer temporary occupations (lasting more than a day), while circles are shorter ‘pop up’ actions (lasting less than a day), and symbols are numbered in the order that the occupation occurred.

TBTC centred on occupations of three properties over a one-month period, with a host of accompanying rallies, actions, marches, talks, and events organised around the occupied buildings (see ). The first occupation, at Summerhill Parade, targeted a row of vacant buildings from which a number of primarily Brazilian migrants in overcrowded conditions had been evicted in May 2018. This eviction, which came in the wake of a Fire Brigade inspection of the privately rented buildings, was a point of overlapping interest for migrants’ rights and housing activist groups (see Sassi Citation2021). In what has become a common strategy for owners of occupied properties in Dublin, an interim injunction order was sought and granted, ordering the occupiers to vacate the premises. The Irish legal system treats squatters’ rights solely in terms of ‘adverse possession’, which places a heavy legal burden on taking possession. Would-be squatters must prove exclusive and public use for 12 years or more before ‘adverse possession’, or squatters’ rights, would be applicable. Much of the case law on adverse possession relates to the long-term use of vacant sites or fields for agricultural or storage purposes (see Woods Citation2020) and has been shaped by strong constitutional emphasis on private property ownership. Where a property owner can prove that they own a property, a prohibitory interim injunction can be sought and quickly granted against either named or unknown trespassers based on the loss of or damage to the property that trespassers represent. Once a property owner is granted an injunction order, occupiers are required to vacate a property within a specified time period, and face both criminal charges for trespass and financial ramifications for the condition in which the building is left (Kirwan Citation2020). Established practice in post-crash Dublin housing activism has been to negotiate withdrawal from occupied properties based on policy demands aimed at alleviating the impacts of homelessness. However, TBTC left the Summerhill Parade occupation prior to enforcement of the injunction order with an internal commitment that doing so was contingent on being ready to occupy another property.

This second occupation was organised as a ‘Housing Direct Action (not the end)’ event, with attendees marching from Summerhill Parade to an initially undisclosed location. This location was the newly-occupied 34 North Frederick Street. The Summerhill Parade occupation lasted for 10 days, but the North Frederick Street occupation lasted for 25 days and was a site of significance for a number of anti-eviction rallies, co-ordinated door-knocking, and demonstrations. While maintaining the North Frederick Street occupation, and following granting of a legal injunction order to vacate the premises, an expansion was held (‘Where to next? We aren't moving but expanding’) to occupy a nearby vacant building at Belvedere Place. This event was used to relaunch the Irish Housing Network, an influential network of housing activist groups that had been involved in earlier occupation campaigns. The Belvedere Place occupation is also significant in recent Dublin housing activism as the first simultaneous political occupation of two buildings by one campaign (albeit unevenly, as the North Frederick Street occupation was more impactful in terms of numbers and activity levels). In early September, the violent eviction of occupiers from Frederick Street by a private security firm being overseen by An Garda Síochána (the Irish police) attracted national attention. The loss of an established base brought a change in TBTC tactics, with a redirection towards more ‘pop up’ occupations (notably of Airbnb's Headquarters, discussed above, and of the Residential Tenancies Board, who adjudicate between landlords and tenants). There was also a subsequent dispersal from TBTC back towards specific housing activist groups.

The TBTC campaign represented the highest profile, longest sustained, and most intense period of housing activism in Dublin since earlier occupations focused on homelessness in 2016 (Hearne et al. Citation2018). In earlier occupations, housing activist coalitions contested wider processes of financialisation and inequality by accommodating the homeless in occupied buildings (see O’Callaghan, Di Feliciantonio, and Byrne Citation2018; Lima Citation2019 for further detail). As an entity, TBTC consisted of a more intersectional coalition of housing, migrant rights, student, LGBT + and anti-racist activist groups operating as a collective, in contrast with earlier post-crash housing activist coalitions in the city (Sassi Citation2021). This collective emerged, in the words of Di Feliciantonio and O’Callaghan (Citation2020, 14), ‘following a fallow period’ for housing activism in the city, and sought to position ‘the housing crisis as the central political issue of the city … using the occupied properties as nodes, the activists extended the tactics of occupation to “pop-up” and disrupt the wider city through actions involving performative and subversive spectacle’. Below, I use TBTC to show how digital/material tactics are used to publicise, co-ordinate, and mediate temporary political occupations as 'performative spectacle'.

Publicising

Digital technologies in general, and social media in particular, were central to publicising TBTC's campaign and contention as it occurred (see timeline above in , each point of which was publicised and organised using TBTC's social media accounts). This point is attested to in media/communication studies and sociological discussions (e.g. Tufekci Citation2017) and often noted by geographers discussing contemporary contention, who distinguish between or connect the digital and the material. However, the socio-spatialities of this as an enduring contemporary digital/material phenomenon are underexplored. Social media are used to communicate with a wider public audience, publicising struggle in ways which interweave material space, its digital representation, and broader contentious meaning and performances. Here, social media are used to gather an audience and disseminate information, often in the form of one-to-many public representations of the cause. TBTC used specific campaign social media pages on Facebook and Twitter to connect to existing housing activist groups and the wider public. Campaign social media pages were used to share demands and messages. These were distributed in material paper leaflets at events as well, but the campaign relied on social media to publicise, document, and share these events in real-time. This use of social media to publicise the campaign extended the real-time ‘footprint’ of occupations, with many more people hearing about or interacting with the campaign online than in-person.

The temporary occupation of Airbnb's headquarters with which I began the paper is an interesting example of this publicising role, because it demonstrates the balance involved in publicising a covert ‘pop up’. TBTC created a public Facebook ‘event’ which was used to invite the public to a ‘flash action’, with attendees to meet a short distance from their undisclosed intended target. During the occupation, TBTC's Facebook page was used to ‘livestream’ the (extremely) temporary political occupation, which ‘popped up’ and held ground in the Airbnb lobby for roughly two hours. Afterward, campaign social media shared a public/press statement on the occupation as ‘disrupting the disruptors’, narrating the event as part of a wider critique of the role of Airbnb, and tech and finance industries, in exacerbating Dublin's housing crisis (see ).

This example shows how housing activists use digital technologies (e.g. livestreams, campaign social media) to connect their digital/material doings or tactics to a broader critical narrative, in which specific actions are connected together as a more expansive and strategic challenge to the status quo. The temporality of the ‘flash action’, which Watt (Citation2016) captures in his description of Focus E15 (a London-based anti-gentrification campaign) and their ability to ‘pop up’, occurs and unfolds in immediate real time. The action simultaneously draws on and contributes to the longer-term underlying digital/material activist infrastructure publicising it. The flexible, interstitial, and ultimately precarious logic that Harris (Citation2020) identifies within ‘pop-up’ geographies and urbanism is accordingly weaponised. In this way, TBTC's ‘flash actions’ resonate with work on ‘improvisational urbanism … beyond the chimera of permanence’ (Till and McArdle Citation2015) and the temporality of radical politics (McArdle Citation2022).

Social media were also used to connect the TBTC campaign to alternative sources of information and narratives around housing, with the Slumleaks blog being a particularly important collaboration. The Slumleaks blog published a series of posts profiling the owners of the buildings that the TBTC campaign occupied (e.g. Slumleaks Citation2018), and campaign social media were used to share these blog posts with a wider public audience. This collaboration, in publicising information about the buildings being occupied, highlighted the less visible social relations and profit-oriented speculation underlying their vacancy. The blog's focus on identifying landlords (or ‘slumlords’) operated as a form of digital publicity that bolstered and shaped a different and contentious narrative around the material conditions found in the private rental sector and those responsible for their perpetuation (see also Nic Lochlainn Citation2021, 13–15). This is particularly pertinent in an Irish context because of the prevalence of small-scale landlords (who make up the majority of those registered to rent property), informational/power asymmetries, and the emotionally-laden nature of the residential rent relation (Byrne Citation2019). Publicising is a digital/material means of identifying and sharing awareness of the individuals involved in perpetuating overcrowding and speculation, serving to make visible and politicise the profit-oriented motives contributing to on-going housing and homelessness crises. Here, activists’ struggles involve a politics of knowledge, which both repurposes existing public information (e.g. company records) and makes public the often opaque or anonymous dealings of property owners and landlords.

Co-ordinating

Digital technologies also play an important organisational role in contemporary housing activism. Social media are used to organise the logistics and bureaucracy that are a key part of co-ordinating contention. This organisational role uses digital technologies in ways which are often explicitly socio-spatial, including the organisational bureaucracy of who should be where, when, what they should bring, and what they should be expecting to do. The use of Facebook ‘event’ pages and hashtags to co-ordinate contention has been well-recognised, and in many respects echoes functions which are often replicated offline and not novel (i.e. these are and always have been necessary concerns when seeking to co-ordinate the movement or presence of multiple people). But the existence and acceptance of the existence of digital/material co-ordination in contemporary contention fits with wider discussion of the creeping insertion of digital technologies in the banal organisation of everyday life (Kichin and Fraser Citation2020). In doing so, digital contention co-opts platforms provided by social media and digital tools, conforming to but also subverting or ‘overspilling’ their intended uses (Duguay Citation2017).

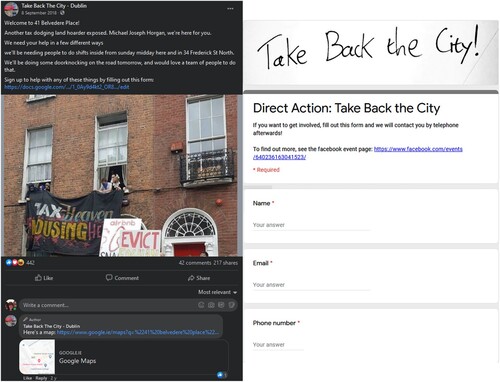

illustrates an example of how TBTC used digital technologies to co-ordinate and manage the bureaucracy of occupation. The pinned top comment in response to their own post provides a Google Map location for the occupied building. The post links viewers through to a Google form for rostering people to be inside the occupied building and/or to carry-out door knocking in support of the occupation in that area.

Here, the ubiquity with which Google tools have come to mediate contemporary life bears out for contention, with these types of technologies now commonly used to co-ordinate and carry out the ‘admin’ of dissent. This is partly for practical reasons—maintaining the occupation depends on having a certain number of people who are willing/able to be physically present in one or other of the occupied buildings for knowable and scheduled periods of time. Co-ordinating on-going presence with an equitable rotation of personnel and distribution of resources is simplified by real-time, shareable, and remotely-accessible digital tools. Here, activists take tools or platforms and use them in ways which apply the intended digital productivity functions to contention. In this functional regard, the occupation's digital/material existence as labour co-ordinated via digital tools operates as a code/space (Kitchin and Dodge Citation2011) which ceases to function without the use of software to co-ordinate the transition from would-be volunteer to occupier in a high-profile and intense action. However, the digital/material mingling of organisational bureaucracy in the form of rostering and ‘optimisation’ begets further administrative work for activists.

Mediating

Thirdly and relatedly, digital technologies impact how occupations are mediated, both in real time and in what remains or endures after the occupation itself ends. In contrast to the DIY archives that Burgum (Citation2020) traces in a number of urban movements, these digital remains are shaped by the platform that hosts them, but they offer another possible means for researchers seeking to piece together the radical counter-narratives of the city. TBTC's campaign demonstrates how the socio-spatial and digital practices involved in contemporary contention transcend hybridity tropes of offline or online, material or digital. Mediation influences the ways in which these types of temporary political occupations play with time and space. In ‘real time’, they are interstitial incursions contesting housing and urban inequalities, popping up and holding ground for a time (Watt Citation2016), confronting structures and beneficiaries of power. Here, taking seriously Leszczynski’s (Citation2015) point that space is always-already mediated, the occupation as material event and holding of ground is publicised, co-ordinated, and mediated using digital technologies. Software is central to the function of occupation as code/space here because it is a crucial way in which the occupation exists or is experienced, and seeks to produce an alternative city to come.

In real time, the use of mobile phones to share images, videos, and ‘livestream’ protest events and activism has been a recurrent theme in contemporary housing activism in Dublin. This construction of occupation as a mediated event has become a common part of the labour of contention. Activists and participants directly engage in producing the mediated occupation and the digital social media ‘buzz’ about occupation as material practice, which is how most people experience the event. More enduringly, the materially occupied building as site of contention is digitally produced and reproduced as a digital/material reference point in myriad ways e.g. as Google Maps pin in . These contentious mediations endure beyond the end-point of the temporary political occupation. In doing so, the digital mediation of occupation through digital technologies augments the material in ways that also signify the importance of the material and urban sites of contestation, with the building itself, for better or worse, now connected to this point of temporary rupture and contestation attempting to ‘take back’ the city. 34 Frederick Street in particular has become a site of digital/material mediation and signification, targeted for housing activist graffiti in the wake of TBTC's eviction, such that the building's future is now indelibly marked as part of a longer and wider story about property as an exclusionary social relation in post-crash Dublin. In this regard, the digital enables traces of occupation to abide and persist in the production of urban space after the event of the occupation itself, preserving its legacy and digitally producing and reproducing the material site of protest. In turn, digital mediation or augmentation cements the importance of the material to urban imaginaries of protest. Here, we can interpret the enduring legacies of occupation in the production of space as a contentious counter-imaginary and the technologically mediated social relationships that occupations produce, with occupied buildings serving as ‘a place for activists to connect and possibly create new actions and form solidarities’ (McArdle Citation2022, 642). While the physical appropriation of space and emphasis on its use is temporary, the digital/material are used to signify and preserve the material site and moment of rupture, with recurrent and inspirational resonance for future contestation.

Conclusions: on occupations, limitations, and the digital/material possible

The TBTC campaign is an example of how temporary political occupations use digital/material tactics to unfold in urban space in ‘real time’, seeking to make both immediate/temporary and enduring impacts. Digital technologies offer tactics and tools for both activists, and researchers doing work with them, to have and assess impacts within what Till and McArdle (Citation2015) refer to as movement ‘beyond the chimera of permanence’. The digital/material is particularly important to attune to in the before, after, and during ‘fallow periods’ (Di Feliciantonio and O’Callaghan Citation2020) and surges of activism, because it helps us to make sense of the on-going labour and social relations which materialise in occupations as, borrowing Vasudevan's phrasing, ‘a place of collective world-making’ (Citation2015, 318), but persist and change over time and space.

This raises the question of change over time, impact, and the utility of digital/material tactics in occupations in particular but also activism more generally. Echoing Leszczynski's (Citation2015) work on spatial media/tion and space as always-already mediated, I argue that researchers working with or on activism are, in most contexts, always-already grappling with digital/material activism in one form or another. This is unsurprising, given the permeation of digital technologies in the publicising, co-ordinating, and mediating of everyday contemporary life. Attuning to and taking seriously the digital/material in occupations and activism allows for a less pessimistic, hybrid, or binary assessment of the digital or material. Instead, the digital/material represents a key if ambivalent site for possibility and lever for change in contemporary activism. This lever, of course, has not evolved as a neutral or unambiguously positive development, and three key questions implicitly arise in this case which future research can speak to. These are firstly, the efficacy of contention that draws on and is at least partly structured by digital technologies designed to commodify attention and extract data; secondly, the extent to which temporary or ‘pop-up’ political occupations feed into a broader precarisation of resistance (Harris Citation2020); and finally, the superficiality of real-time digital mediation, such as I expressed in the introduction with my own ambivalent observation, rather than participation, in the Airbnb protest. Sketching the dimensions and efficacy of digital/material contention requires further and deeper scholarly engagement with how activists use digital technologies, and particularly how these uses cover a spectrum that ranges from the spectacular to the mundane. However, this contribution uses TBTC to demonstrate how temporary political occupations operate as a code/space (Kitchin and Dodge Citation2011), in which software and space are essential to the functioning of a space and its social relations. In doing so, temporary political occupations like TBTC's can be seen as sites of possibility, puncturing the status quo in ways that can have immediate effects and enduring resonances, particularly in asserting the right to the city and making claims to the production of urban spaces. These contentious urban spaces, or ‘counterspaces’ (Lefebvre and Nicholson-Smith Citation1991, 349), are often temporary and usually precariously positioned in a legal system that leans towards the interests of property owners, but their temporariness does not negate their longer-term impacts on housing activists’ tactics and social networks. Here, temporary political occupations fit with McArdle’s (Citation2022, 642–643) discussion of squatted social centres in post-crash Dublin, which have ‘played an important role in the landscape of autonomous politics in Dublin at the time and afterwards’. Understanding temporary political occupations as digital/material accordingly highlights how the digital, the urban, and their intertwining offer potentialities for resistance to ‘take place’ within a wider urban context of housing inequality and foreclosure.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to Sam Burgum and Alex Vasudevan for accepting my first RGS-IBG presentation in their session, and also for managing to balance Special Feature organising during a global pandemic with professional and personal commitments. I’m also very grateful for the three anonymous reviewers, whose insights and observations substantively improved the paper, and to all of the City editorial team for the work they do. The paper and my research more broadly owes a profound debt to housing group participants, and I hope to do you all justice and provide assistance in the struggle. Finally, special thanks to my thesis supervisor, Cian O’Callaghan, both for the specific support in attending the 2019 RGS-IBG during a difficult time and for the more general and steadfast support throughout the PhD—there aren't enough words for all that it's meant, so I’ll say no more.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maedhbh Nic Lochlainn

Maedhbh Nic Lochlainn is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Geography and Spatial Planning at the University of Luxembourg, where she works on the FNR-funded FINCITY project (European Financial Centres in Transition). Maedhbh completed her PhD, supervised by Cian O’Callaghan, in the Department of Geography at Trinity College Dublin in 2022. Email: [email protected]

References

- Akers, Joshua, Eric Seymour, Diné Butler, and Wade Rathke. 2019. “Liquid Tenancy: ‘Post-crisis’ Economies of Displacement, Community Organising, and New Forms of Resistance .” Radical Housing Journal 1 (1): 9–28. doi:10.54825/JGJT2051

- Arampatzi, Athina. 2017. “The Spatiality of Counter-Austerity Politics in Athens, Greece: Emergent ‘Urban Solidarity Spaces .” Urban Studies 54 (9): 2155–2171. doi:10.1177/0042098016629311.

- Ash, James, Rob Kitchin, and Agnieszka Leszczynski. 2018. “Digital Turn, Digital Geographies? ” Progress in Human Geography 42 (1): 25–43. doi:10.1177/0309132516664800.

- Bluteau, Joshua. 2021. “Legitimising Digital Anthropology Through Immersive Cohabitation: Becoming an Observing Participant in a Blended Digital Landscape .” Ethnography 22 (2): 267–285. doi:10.1177/1466138119881165

- Bresnihan, Patrick, and Michael Byrne. 2015. “Escape Into the City: Everyday Practices of Commoning and the Production of Urban Space in Dublin .” Antipode 47 (1): 36–54. doi:10.1111/anti.12105

- Burgum, Samuel. 2020. “This City Is An Archive: Squatting History and Urban Authority .” Journal of Urban History 48 (3): 504–522. doi:10.1177/0096144220955165.

- Byrne, Michael. 2015. “Bouncing Back: The Political Economy of Crisis and Recovery at the Intersection of Commercial Real Estate and Global Finance .” Irish Geography 48 (2): 78–98. doi:10.2014/igj.v48i2.626.

- Byrne, Michael. 2019. “The Political Economy of the ‘Residential Rent Relation’: Antagonism and Tenant Organising in the Irish Rental Sector .” Radical Housing Journal 1 (2): 9–26. doi:10.54825/CDXC2880

- Cohen, Julie E. 2007. “Cyberspace As/And Space .” Columbia Law Review 107 (1): 210–256.

- de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Rendell. Berkeley, Calif, London: University of California Press .

- Di Feliciantonio, Cesare, and Cian O’Callaghan. 2020. “Struggles Over Property in the ‘Post-Political’ Era: Notes on the Political from Rome and Dublin .” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 38 (2): 195–213. doi:10.1177/2399654419870812.

- Duguay, Stefanie. 2017. “Dressing up Tinderella: Interrogating Authenticity Claims on the Mobile Dating App Tinder .” Information, Communication & Society 20 (3): 351–367. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1168471.

- Erie, McElroy, and Manon Vergerio. 2022. “Automating Gentrification: Landlord Technologies and Housing Justice Organizing in New York City Homes .” Environment and Planning D 40 (4): 607–626. doi:10.1177/02637758221088868

- Ferreri, Mara. 2015. “The Seductions of Temporary Urbanism .” Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization 15 (1): 181–191.

- Ferreri, Mara. 2021. The Permanence of Temporary Urbanism: Normalising Precarity in Austerity London. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press .

- Flesher Fominaya, Cristina, and Kevin Gillan. 2017. “Navigating the Technology-Media-Movements Complex .” Social Movement Studies 16 (4): 383–402. doi:10.1080/14742837.2017.1338943.

- García-Lamarca, Melissa. 2017. “From Occupying Plazas to Recuperating Housing: Insurgent Practices in Spain: From Occupying Plazas To Recuperating Housing .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41 (1): 37–53. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12386.

- Halvorsen, Sam. 2015. “Taking Space: Moments of Rupture and Everyday Life in Occupy London: Taking Space: Occupy London .” Antipode 47 (2): 401–417. doi:10.1111/anti.12116.

- Harris, Ella. 2020. Rebranding Precarity: Pop-up Culture as the Seductive New Normal. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct = true&scope = site&db = nlebk&db = nlabk&AN = 2628044.

- Harvey, David. 2012. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. New York: Verso .

- Hearne, Rory. 2020. Housing Shock: The Irish Housing Crisis and How to Solve It. Bristol: Policy Press .

- Hearne, Rory, Cian O’Callaghan, Cesare Di Feliciantonio, and Rob Kitchin. 2018. “The Relational Articulation of Housing Crisis and Activism.” In Rent and Its Discontents: A Century of Housing Struggle, edited by Neil Gray, 153–167. Transforming Capitalism. London: Rowman & Littlefield International .

- Hine, Christine. 2015. Ethnography for the Internet: Embedded, Embodied and Everyday. London: Bloomsbury .

- Kaika, Maria, and Lazaros Karaliotas. 2016. “The Spatialization of Democratic Politics: Insights from Indignant Squares .” European Urban and Regional Studies 23 (4): 556–570. doi:10.1177/0969776414528928.

- Kichin, Rob, and Alistair Fraser. 2020. Slow Computing: Why we Need Balanced Digital Lives. Bristol: University Press .

- Kirwan, Brendan. 2020. Injunctions: Law and Practice. Third Edition. Dublin: Round Hall .

- Kitchin, Rob, and Martin Dodge. 2011. Code/Space: Software and Everyday Life. Software Studies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press .

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1996. Writings on Cities. Edited by Eleonore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas. Malden, Oxford, Carlton-Melbourne: Blackwell Publishing .

- Lefebvre, Henri, and Donald Nicholson-Smith. 1991. The Production of Space. Nachdr. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell .

- Leontidou, Lila. 2012. “Athens in the Mediterranean ‘Movement of the Piazzas’ Spontaneity in Material and Virtual Public Spaces .” City 16 (3): 299–312. doi:10.1080/13604813.2012.687870.

- Leszczynski, Agnieszka. 2015. “Spatial Media/Tion .” Progress in Human Geography 39 (6): 729–751. doi:10.1177/0309132514558443.

- Lima, Valesca. 2019. “Urban Austerity and Activism: Direct Action Against Neoliberal Housing Policies .” Housing Studies 36 (2): 258–277. doi:10.1080/02673037.2019.1697800.

- Marcuse, Peter. 2009. “From Critical Urban Theory to the Right to the City .” City 13 (2–3): 185–197. doi:10.1080/13604810902982177.

- Mare, Admire. 2017. “Tracing and Archiving ‘Constructed’ Data on Facebook Pages and Groups: Reflections on Fieldwork among Young Activists in Zimbabwe and South Africa .” Qualitative Research 17 (6): 645–663. doi:10.1177/1468794117720973.

- Martínez-Lopez, Miguel, and Ágela García Bernardos. 2015. “The Occupation of Squares and the Squatting of Buildings: Lessons from the Convergence of Two Social Movements .” ACME -An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 14 (1): 157–184.

- Mayer, Margit. 2009. “The ‘Right to the City’ in the Context of Shifting Mottos of Urban Social Movements .” City 13 (2–3): 362–374. doi:10.1080/13604810902982755.

- Mayer, Margit, Catharina Thörn, and Håkan Thörn. 2016. Urban Uprisings: Challenging Neoliberal Urbanism in Europe. Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology. London: Palgrave Macmillan .

- McArdle, Rachel. 2019. “Liquid Urbanisms: Dublin’s Loose Networks and Provisional Places.” PhD thesis, National University of Ireland, Maynooth.

- McArdle, Rachel. 2022. “‘Squat City’: Dublin’s Temporary Autonomous Zone. Considering the Temporality of Autonomous Geographies .” City 26 (4): 630–645. doi:10.1080/13604813.2022.2082149.

- McLean, Jessica, Sophia Maalsen, and Sarah Prebble. 2019. “A Feminist Perspective on Digital Geographies: Activism, Affect and Emotion, and Gendered Human-Technology Relations in Australia .” Gender Place and Culture 26 (5): 740–761. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2018.1555146.

- Merrifield, Andy. 2011. “The Right to the City and Beyond: Notes on a Lefebvrian Re-Conceptualization .” City 15 (3–4): 473–481. doi:10.1080/13604813.2011.595116.

- Nic Lochlainn, Maedhbh. 2021. “Digital/material housing financialisation and activism in post-crash Dublin .” Housing Studies: 1–18. doi:10.1080/02673037.2021.2004092.

- O’Callaghan, Cian, Cesare Di Feliciantonio, and Michael Byrne. 2018. “Governing Urban Vacancy in Post-Crash Dublin: Contested Property and Alternative Social Projects .” Urban Geography 39 (6): 868–891. doi:10.1080/02723638.2017.1405688.

- O’Callaghan, Cian, Sinéad Kelly, Mark Boyle, and Rob Kitchin. 2015. “Topologies and Topographies of Ireland’s Neoliberal Crisis .” Space and Polity 19 (1): 31–46. doi:10.1080/13562576.2014.991120.

- O’Callaghan, Cian, and Pauline McGuirk. 2020. “Situating Financialisation in the Geographies of Neoliberal Housing Restructuring: Reflections from Ireland and Australia .” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 53 (4): 809–827. doi:10.1177/0308518X20961791.

- Sassi, Juliana. 2021. “Take Back the City: Building an Interracial Class Coalition to Fight for ‘Homes for All’ .” Irish Journal of Sociology 29 (1): 54–76. doi:10.1177/0791603520958627

- Shaw, Joe, and Mark Graham, eds. 2017. Our Digital Rights to the City. Meatspace Press . https://ia601900.us.archive.org/25/items/OurDigitalRightsToTheCity/OurDigitalRightstotheCity.pdf.

- Shelton, Taylor. 2017. “Spatialities of Data: Mapping Social Media ‘Beyond the Geotag .” GeoJournal 82 (4): 721–734. doi:10.1007/s10708-016-9713-3.

- Slumleaks. 2018. “Summerhill Parade - Who is the Mystery Landlord?” Slumleaks. Accessed 11 September 20. https://web.archive.org/web/20201109032049/https://slumleaks.wordpress.com/2018/05/07/summerhill-parade-who-is-the-mystery-landlord/.

- Till, Karen, and Rachel McArdle. 2015. “The Improvisational City: Valuing Urbanity Beyond the Chimera of Permanence .” Irish Geography 48 (1): 37–68. doi:10.2014/igj.v48i1.525.

- Tonkiss, Fran. 2013. “Austerity Urbanism and the Makeshift City .” City 17 (3): 312–324. doi:10.1080/13604813.2013.795332.

- Tufekci, Zeynep. 2017. Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. New Haven; London: Yale University Press .

- Vasudevan, Alexander. 2015. “The Autonomous City: Towards a Critical Geography of Occupation .” Progress in Human Geography 39 (3): 316–337. doi:10.1177/0309132514531470.

- Watt, Paul. 2016. “A Nomadic War Machine in the Metropolis: En/Countering London’s 21st-Century Housing Crisis with Focus E15 .” City 20 (2): 297–320. doi:10.1080/13604813.2016.1153919.

- Woods, Una. 2020. “Protection for Owners Under the Law on Adverse Possession: An Inconsistent Use Test or a Qualified Veto System? ” Osgood Hall Law Journal 57 (2): 342–380.

- Yrigoy, Ismael. 2020. “The Role of Regulations in the Spanish Housing Dispossession Crisis: Towards Dispossession by Regulations? .” Antipode 52 (1): 316–336. doi:10.1111/anti.12577.