Abstract

This article explores the ‘quiet encroachment' movement that has been taking place in Iran for decades. Led by low-income people, this movement aims to reclaim the right to housing as a basic requirement for living. With a lack of social housing services and other relevant facilities, the urban poor in Iran have taken it upon themselves to informally occupy or purchase public lands, in order to improve their socio-economic situation by avoiding the cost of renting or buying housing in the formal market. One of the neighbourhoods that has undergone this transformation is ZoorAbad, situated on a hill near Tehran. The hill was designated as national public land in 1969, but due to industrial growth, poor people who migrated from villages to Tehran and its proximities were unable to afford formal housing prices so moved to ZoorAbad to build their own homes. In the 1990s, in line with the government’s speculative approach towards land, the Iranian government developed an ‘Improving Plan of ZoorAbad’, aimed at demolishing this informal settlement. It led to the demolition of more than 4000 housing units and the forced displacement of settlers. The two main groups of residents in ZoorAbad—landowners and tenants—have had different capacities to reject the municipality’s offer of purchase or to negotiate with the government. This piece illustrates how the government’s market-oriented approach to address the housing issue in informal neighbourhoods such as ZoorAbad can lead to financial loss and reduced opportunities for local residents. It sheds light on the contemporary grassroot strategies used by the urban poor to address their housing needs in ZoorAbad and the dynamics, strategies and shifting dynamics among various groups.

A definition of courage has arisen from the women and girls in Iran who initiated an inclusive feminist uprising. They aim to reclaim basic civil rights for all citizens, so whilst the pivotal focus is on women’s rights, they could be considered as representatives of wider discriminated groups and marginalised communities that, during the last four decades, have been subject to the surveillance of the Islamic government in Iran. In other words, the protesters reclaim the right of ‘living’ which has been banned from diverse citizens, including low-income households. While the current uprising has the characteristics of a revolution, during previous decades marginalised groups in Iran have reclaimed civil rights in different ways. ‘Quiet encroachment’ is a political action and movement by low-income people to reclaim the right to housing as a basic requirement for living. Made necessary by the absence of social housing services and other relevant facilities, the urban poor in Iran have taken it upon themselves to reclaim their rights as citizens by taking over public lands informally, through occupation or purchase, and also by making their lifestyles and economic situations visible, in plain view of governors and policy makers in the Tehran-Karaj metropolitan area. Following the 1979 revolution, the Iranian government promoted pro-poor policies, but in reality the lives of millions of poor people throughout the country remain difficult. Similar to Iranian women who demonstrate their dissatisfaction through removing the hijab in public spaces, the urban poor in areas such as the ZoorAbad neighbourhood also demonstrate their dissatisfaction by disobeying rules through visible informal construction.

The term ‘quiet encroachment’ was coined by Asef Bayat (Citation2013, 51) a prominent Iranian-American sociologist, referring to the efforts of the urban poor who discovered and produced new spaces for improving their living conditions, especially in terms of affordable housing. ZoorAbad is a neighbourhood near Tehran whose history has been tied to the quiet encroachment movement since the 1960s when rural migrants moved to the capital to pursue a decent life. I have a personal connection to the neighbourhood, as I completed my elementary education at a school located there. This has given me a unique perspective and deep understanding of the community and its inhabitants. My familiarity with the area has also allowed me to witness the changes and challenges faced by the residents over time. This piece sheds light on the contemporary grassroot strategies used by the urban poor to address their housing needs in ZoorAbad and the dynamics among various groups, including Afghan refugees, Iranian tenants, second or third generation of squatters and newcomers.

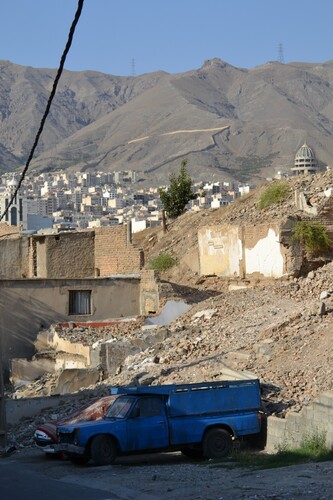

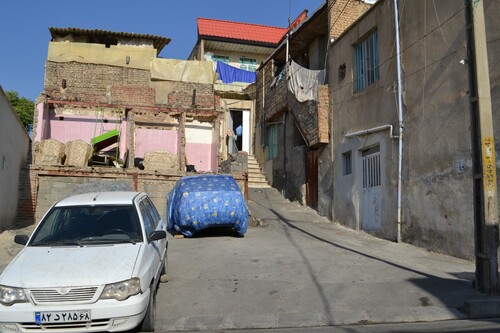

Proximate to Tehran, and adjacent to the affluent neighbourhood of Azimiyeh, on a hill with steep alleyways, are many tiny houses with unique organic architecture (see and ). This colony of hilltop houses occupies a 165 hectares area, making up the informal neighbourhood of ZoorAbad, which has become an icon in the Tehran-Karaj region.

In 1969, the hill was designated as national public land. However, during the 1970s, the growth of agriculture, food, and steel industries, as well as the formation of veterinary serum and vaccine laboratory firms in the proximity of Karaj city, led to an industrialisation boom. As a result, poor people migrated from small towns and villages to Tehran and its proximities. Unable to afford housing prices, they went to ZoorAbad and built their own homes on this public land (Qasemi, Citation2011).

There are now two main groups of residents in ZoorAbad: landowners and tenants. Landowners can be further divided into two groups: first, squatters who illegally took possession of public land during the 1960s and later on, especially during the first decade of the Iran revolution in 1979, without paying for it; and those who paid the first squatters and constructed their own housing on the land. Both these groups of landowners were able to save money by avoiding the cost of renting or buying housing in the formal market. The second major group of residents in ZoorAbad consists of tenants who pay their landlords monthly rent for their housing.

The grassroots informal architecture of the buildings in ZoorAbad has provided a unique human-scaled space that is simultaneously semi-urban and semi-rural (see ). These self-built informal housing units are much more human-scaled compared to the typical formal buildings constructed according to the municipality codes and standards. The contrast can be clearly observed by comparison with the neighbouring wealthy town of Azimiyeh, where formal building complexes dominate the landscape (see and ).

Figure 3: Organic, grassroots, human-scale architecture of ZoorAbad. July 5, 2022. Photo by the author.

Figure 4: ZoorAbad is in the foreground with Azimiyeh in the background. There is evidence of slum clearance in ZoorAbad through the national ‘improving plan’. July 5, 2022. Photo by the author.

Figure 5: Close up of Azimiyeh with tall formal apartment buildings and residential complexes, contrasting ZoorAbad through their lack of human scale. [Photo retrieved from mrestate.ir on April 19, 2022].

![Figure 5: Close up of Azimiyeh with tall formal apartment buildings and residential complexes, contrasting ZoorAbad through their lack of human scale. [Photo retrieved from mrestate.ir on April 19, 2022].](/cms/asset/8e1403b1-c634-427f-a71b-09231127c5a1/ccit_a_2230020_f0005_oc.jpg)

During the 1970s and 1980s the population of ZoorAbad reached 120,000. Since then, according to various socio-economic shifts, the social configuration of the settlers in ZoorAbad has also changed. One of the main forces driving this has been the ‘Improving Plan of ZoorAbad’, developed by the Iranian government. This plan has resulted in the demolition of more than 4000 housing units and consequently a forced displacement of the local settlers. Alongside this, an economic crisis and a staggering upward trend of land and housing prices in Iran have led to population movement in ZoorAbad. Political crisis in the neighbouring country of Afghanistan has also resulted in a significant Afghan population movement into ZoorAbad, also in search of affordable places to live.

At the end of an alleyway, in the middle of a sunny summer afternoon, Mint, a 33-year-old woman, sits on the ground, under the shade of a willow tree, cleaning vegetables and herbs. She wears fashionable clothing, with tattooed eyebrows. Mint was born in ZoorAbad and got married aged 17. She, her husband and four children are tenants who live in a 40 square metre unit. Their monthly income is around $140 and they pay half of this, $70 per month, in rent. They also had to pay a one-off deposit of $280 when they moved in.

Mint says:

Although the reason for living in ZoorAbad is the lack of choice for us, air quality in this neighbourhood is remarkable! Also, I love how secure the neighbourhood is. It’s like living in a village. All neighbours know each other and that secure atmosphere came from this.

Figure 6: Grassroots architecture and steep alleyways of ZoorAbad. July 5, 2022. Photo by the author.

Mint also talks about the negative effect of the ‘improving plan’ in ZoorAbad during the 1990s. The Karaj municipality was in charge of the implementation of the plan and its main intention was slum clearance: to eradicate the neighbourhood and demolish the housing in order to provide a more ‘beautiful’, ‘safe’ and ‘formal’ area within Karaj city and in proximity to the capital. The municipality did not plan to provide an improved area for the settlers of ZoorAbad and its priority was to pursue a speculative approach towards the land and urban housing within the neighbourhood (see ).

Figure 7: Demolition of housing via implementation of the ‘improving plan’. July 5, 2022. Photo by the author.

The ZoorAbad settlers were affected differently by the ‘Improving Plan’ as the different groups of landlords and tenants do not have the same bargaining power and financial resources. Also, desires among residents differed based on factors such as age and life stage. Landowners of more than one housing unit had more capacity to reject the municipality’s offer of purchase or to negotiate with the government. For instance, Vatan, a 70-year old woman, who owns her own shopping store and a four-storey building in ZoorAbad, says she refused the municipality’s offer to purchase her properties. Instead, she opted to stay in the neighbourhood because of her desire to maintain social connections. Meanwhile, other landowners in ZoorAbad, through selling some properties, bought housing in a formal neighbourhood, considered as a social mobility for their families. For example, Maryam, a 36-year-old woman, says that during the time of the ‘Improving Plan’, her family sold three of the five housing units that they owned in ZoorAbad in order to buy one property in Azimiyeh, the nearby affluent neighbourhood. Her father still works in ZoorAbad, but her parents bought the Azimiyeh unit so that their children could escape the stigmatisation that attaches to ZoorAbad.

To move into a less stigmatised, formal area remains the goal of many, with second and third generations of ZoorAbad settlers tending to leave the neighbourhood. Maryam, and also Basir, a 30-year-old man, both explained how they lost social and job opportunities due to their stigmatised ZoorAbad addresses and that they therefore plan to leave the neighbourhood. Mint also wishes to move to another neighbourhood to provide her children with better opportunities. In many cases, residents’ were able to realise their wishes as they benefited from the financial capital accumulated by the first generation of squatter families who saved money by eliminating the cost of renting or buying housing. So, the moving on of the second and third generation of squatter and landlord households in ZoorAbad toward the ‘formal’ neighbourhood constitutes an outflow of young people in recent years, as they benefit from the inherited capital of previous generations, achieving social upward mobility.

These original families are then being replaced by very different households. Due to inflation, devaluation of the currency and sharp land price increases in Iran, first-time home-buyers from ‘formal’ neighbourhoods have had no other choice but to buy a home in an ‘informal’ neighbourhood such as ZoorAbad. For example, in 2020, Zar, a 37-year-old woman with a university degree, bought a 40-square metre basement studio for the price of $5000 in ZoorAbad. Rents and deposits have also increased, more than double in some cases. However, Iranian native settlers of ZoorAbad have often cast the blame for price increases on Afghan refugees and other migrants who are also moving into the neighbourhood. Unwelcome in many formal neighbourhoods, refugees have little choice of where to live and this is further taken advantage of by landlords who charge them higher rents. These tensions are made worse by competition within the labour market.

In the absence of affordable housing plans and policies, market-oriented and speculative activities such as the ‘improving plan’ in ZoorAbad represent the dominant approach of the government to address the housing issue within informal neighbourhoods. These sorts of plans can eradicate the financial capital of the dwellers through forcing the local dwellers to sell their homes to the municipality at prices lower than the market value; they can also diminish the opportunities of the displaced settlers whose access to educational, economic and medical facilities is reduced in the more remote neighbourhoods to which they are forced to move. The social bonds built in ZoorAbad over four decades are also annihilated as households are displaced (see ).

The ZoorAbad neighbourhood nevertheless keeps its attractiveness for the urban poor, drawn there from all over the Tehran-Karaj metropolitan region. But the settlers’ experiences clearly indicate the need for a better understanding of the socio-spatial inequalities across the urban field as informal settlements change their character and are impacted by government policies. In the absence of social policies that can provide adequate housing for low-income families, it’s important to recognise self-built housing as a grassroots strategy that addresses their housing needs. Instead of resorting to demolitions and displacing these communities, urban policies and plans need to uncover the motivations behind them, and to determine whose interests will be served through these plans. By doing so, the implications of such policies can be better understood and alternative ones developed to ensure that the rights and needs of these vulnerable communities are protected.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Kaveh Ehsani and Dr. Azam Khatam for generously contributing their time and expertise to this research project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pegah Behroozi Nobar

Pegah Behrouzi Nobar is a PhD candidate in Urban Studies at the University of British Columbia in Canada. She completed her elementary education at a school in ZoorAbad, Karaj, and therefore has good knowledge of the neighbourhood. Due to her religious beliefs in the Baha’i faith, she was prevented from pursuing her higher education at public formal universities in Iran. As a result, she obtained her bachelor’s degree in architecture from an informal underground institution called the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education (BIHE) in Iran. Email: [email protected]

References

- Bayat, A. 2013. Life as Politics; How Ordinary People Change the Middle East (Second). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press .

- Qasemi, M. (Director). 2011. اینجا زورآباد است [Here is ZoorAbad] Karaj, Iran [Film].