Abstract

This article examines the work of ‘image construction’ and ‘memory reconstruction’ by focusing on World Expos held in Sydney and Brisbane, Australia. We argue the construction of urban imaginaries through triumphal narratives induces a form of mega-event amnesia: the erasure from collective memory of communities and cultural artefacts, and the suppression of protest and resistance against these events. We then show how art can be used as a form of ‘memory reconstruction’. Two case studies offer alternative narratives in the form of public art and archival media. The first case forges new storylines that remember Aboriginal culture and language through a major public art project in the heart of Sydney. The second discusses how a digitised archival film made by feminist filmmakers spotlights decades of disregard for the destruction of Brisbane’s working-class inner-city fabric when made accessible to new audiences. These alternative narratives reconstruct the memory of the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition and Brisbane’s World Expo 88 to show how art may be used to awaken urban memories and collective remembrance. Alternative narratives also breathe new life into the complex and contested histories of mega-events. While protest and ‘the art of dissent’ have been widely discussed regarding the Olympics, few scholars have considered their relationship to World Expos. Fewer still have considered how art reconstructs and reinterprets mega-events decades after they were held.

Introduction: how images construct the storied past and present of world expos

Mega-events such as World Expos leave lasting spatial imprints on host cities that evolve over time (Chan and Li Citation2017; Roche Citation2017). However, they do more than just rearrange urban spaces. In transforming the built environment to accommodate mega-event sites, usually across many years, their critics contend that governments, organising committees, and businesses, among other civic elites, use these events as vehicles to reimagine their cities (Baade and Matheson Citation2017; Broudehoux Citation2004). In doing so, these urban actors recast physical landscapes and social relations while aspiring to forge new global reputations for the host city and nation. This exercise in nation branding and social engineering is common to both 19th-century international exhibitions, as a vehicle of European colonisation, and more recent World Expos, a product of contemporary globalisation (Roche Citation2017).

To achieve such artifice, governments and civic elites enact new imagery of the host city and nation that travels far and wide. These triumphal urban images tout the advantages of welcoming a spectacular mega-event to the host city and nation. They market the hosts as ‘open for business’ and are mobilised to justify the enormous public expense of organising mega-events (Baade and Matheson Citation2017). Triumphal imagery proselytises, ex-ante and ex-post, the virtues of the host city and nation on a global stage. This is what Broudehoux (Citation2004, 25) conceptualises as ‘urban image construction’, which offers governments and civic elites ‘a means of manipulating public opinion and controlling social behaviour’. The myriad ways of knowing urban communities are renounced in favour of simplified imagery that promotes the city within global arenas predominated by financial markets, trade, and tourism. This sanitised image of the host city is integral to preparations for the spectacular event. In this way, urban images can be used to first colonise, then homogenise, and eventually displace the diverse social and cultural lives of urban communities.

Triumphal images are enacted amidst the physical displacement of whole communities and eventual erasure of their memory. Consequently, the government and civic elites seek control of collective experiences and memories of a place. This is achieved through the removal of residents from the place of the event, who do not fit in easily with the aspirations of the host city, for example, through eviction and/or concealment behind temporary and permanent structures (Azuela, Duhau, and Ortiz Citation1998; Bryson Citation2013; Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions Citation2007; Dutta Citation2007). The outcome is a community comprised of wealthy inhabitants and visitors who view the city as a place of leisure and consumption. Over time, these actions can suspend the previous inhabitants’ claims and attachments to place, which permanently changes a community (Alawadi Citation2016). With the urban imagination trained on constructing the future city, little room is spared to dig into the alternative narratives upon which the host city stands.

The construction of triumphal urban imaginaries induces a form of mega-event amnesia: the selective erasure from collective memory of communities and cultural artefacts, and the suppression of protest and resistance against these events. If mega-events mirror a society’s dominant ideologies and discourses, then expanding the temporal analysis beyond their short life span and ‘the urge to simplify’ them is crucial to redressing commentaries that ‘risk underselling the complexity and rich materiality of mega-events’ (Gardner Citation2022, 4). International Exhibitions or International Expositions, later known as World’s Fairs, and more recently as World Expos have long been used to construct idealised and essentialising images of cities, nations, societies, and cultures. Rebranding not only takes place physically at the expo or in the host city, but also through the transmission of media and images before and after the event. Mega-event amnesia, therefore, occurs when these urban images market the host city and nation, over time, by wilfully disregarding the memory of places and communities, and by rendering the actions of those communities and their attachment to place invisible while elevating others. Although the theory of image construction we outline heretofore establishes the framework for the article, our interest is in how art might resist the long afterlife of mega-event amnesia.

To bridge social, temporal, and spatial gaps in mega-event literature, the article considers the long afterlives of two Australian World Expos. Mega-event scholarship has focused largely on the social legacies and impacts of the Olympics in relation to host cities and nations. This includes substantial scholarship on urban image construction (Adese Citation2016; Broudehoux Citation2004; Citation2007; Citation2017; Broudehoux and Monteiro Citation2017; Koch Citation2018), the sportification of place (Parmett Citation2022), and the art of dissent (Powell and Marrero-Guillamón Citation2012). Like much mega-event scholarship, this work is focused on a narrow temporal window bound to the event, including preparations and immediate after-effects, which leaves mega-event legacies unaddressed (Gardner Citation2022). Additionally, the social legacies of World Expos are understudied compared to other mega-events (Davis Citation2011; Minner, Zhou, and Toy Citation2022; Minner and Abbott Citation2019). How images of the city or nation are reinforced and/or challenged through visual media, especially public art and film, is not well-represented within this literature. Less studied is the cultural imprint and contemporary relevance of expos to Australian cities.Footnote1 Addressing these gaps, we consider how communities can remember differently, and how film and public art can be used as a form of memory care, that could challenge the urban imaginaries and erasures of 19th- and 20th-century mega-events.

To do this, the place of urban memories associated with the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition and Brisbane’s 1988 World Expo are examined through the lens of two case studies. While these expos are not well-known internationally, they inspired important examples of Aboriginal artwork and feminist filmmaking. Alone, the two cases merit scholarly attention based on the resonance and quality of their artistic interventions. They also merit attention for reviving memories of past mega-events as a means of challenging past erasures, which reconstructs displaced urban memories. The first case, Jonathan Jones’ barrangal dyara (skin and bones) (Citation2016), forges new storylines that remember Aboriginal culture and language through a major public art project in the heart of Sydney. The second, Wendy Rogers and Sue Ward’s City for Sale, shows how a digitised archival film made by feminist filmmakers, spotlights decades of disregard for the destruction of Brisbane’s working-class inner-city fabric when made accessible to new audiences. Their alternative narratives show how art may be used to awaken urban memories and collective remembrance, and complexify the history of mega-events. Although the impact of these art projects is limited, they show how art can revive public debate about rights to the present and future city. The case studies address two primary research questions: How can art and filmic media help to recover narratives about places and communities that were displaced and forgotten in the wake of a mega-event? What can these media tell us about the significance of dissent and remembering trauma, even decades after a mega-event is staged?

To answer these questions, the article examines the place of urban memories associated with mega-events that occurred on unceded Indigenous lands. In urban Australia, settler colonialism is an ongoing project of indigenous erasure (Blatman and Porter Citation2019). A project that denies Aboriginal sovereignty to land (Langton Citation2020). Although lesser in scale, the displacement highlighted by the narrative of image construction raises the legacy of over 230 years of dispossession waged against Aboriginal people in Australia, including their exclusion from city centres (Greenop and Memmott Citation2007). Aboriginal rights to the city remain vulnerable to indirect and direct displacement through mechanisms of the real estate market.

This article continues as follows. First, we address theories of image construction. Then, two case studies illustrate how different media can resist mega-event amnesia and be used to revive memories that challenge the erasures associated with mega-events. Our first case study resurrects a historical event of (mis)representation of Aboriginal culture at the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition through public art. Our second case illustrates how digitised archival film, brought to the light of day by the internet, can aid in remembrance of Brisbane’s working-class neighbourhoods and Indigenous histories suppressed by imagery used to promote and celebrate Expo 88. We then discuss how alternative narratives expressed in public art and archival film can awaken urban memories and recover collective memory. We conclude with reflections on a historically conscious process of image construction enriched by stories of place and community that complexify the history of mega-events and their host cities.

Image construction and memory reconstruction

The ebb and flow of image construction is authored collectively by waves of dominant, but also competing, complementary, and evolving narratives. Narratives and stories are ‘feasts for mind, heart and body’ and connect us deeply to the places in which we live (Haraway Citation2016, 83). Dobraszczyk (Citation2017, 885) writes the city is ‘a meld of matter and mind’ and emphasises how storytelling devices, such as science fiction novels, architectural renderings, and art, construct imaginaries that give shape to urbanites experience of the city as much as its physical materiality does. For the marginalised and dispossessed, stories may equally be insurgent and empowering (Sandercock Citation1998). Instigated and strengthened by situated voices across a multitude of places, stories provide the intangible raw materials for the construction of urban landscapes (Sandercock Citation2003; Zitcer and Almanzar Citation2020). Above all, narratives matter because their storylines capture imaginations, incite reactions, and organise the past, present, and future of urban landscapes (Simone and Pieterse Citation2017). Ultimately, narratives are used to project values and achieve political aims.

If narratives shape minds and memories, how they are utilised in the transformation of physical and cultural landscapes is of much intrigue. Broudehoux’s focus on the practice of urban image construction provides a framework for analysing the imprint mega-events leave on host cities. To develop the mega-event space, the narrative is manipulated, ‘thereby affecting representation and the social construction of meaning’ (Broudehoux Citation2004, 27). Embellished for global audiences, these narratives impose rigid views of diverse racial and class compositions, which can lead to discrimination against, and erasure of, the poor in favour of dominant groups. Despite claims to the contrary, no individual, entity or their narrative is ever in complete control because human artifice is always partial and incomplete.

Koch’s (Citation2018) notion of ‘spectacular urbanism’ shows how spectacle is used as a political technology to broadcast preferred images of the city and forms of urban development. With a particular focus on Astana, Kazakhstan, Koch shows how undemocratic states submerge undesirable populations and geographies beneath dominant spatial imaginaries. She further discusses how festivals and monuments perform and add tangibility to abstract political ideologies. Literature on mega-events is replete with critiques of the spectacular urbanism produced in the staging of an event meant to upstage and modernise the host city (Broudehoux Citation2004; Citation2007; Citation2017; Gotham Citation2011; Roche Citation2017; Shin Citation2012). If the event is considered a success, Roche (Citation2017) suggests that the imagery of this urban spectacle will be added to the city’s urban memory and feature prominently in storytelling about that city.

Given the substantial attention and literature on narrative, legacy, and spectacle, there remains limited discussion about how contestation and territories of ex-host cities are tamed, erased, and forgotten, and the role of image construction in that process. More could be known about how alternative narratives are recorded, amplified, and transmitted through counter-protest and alternative media. To reconstruct urban memories of place, this article examines how art and filmic media can address ‘collective amnesia’ (Pike Citation2016; Saab Citation2007) by asking a city to remember that which previous generations and inhabitants overlooked or sought to erase. Bowring (Citation2017) writes of sites of trauma and the prospects of care and healing through remembrance of past traumas, involving a process of ‘re-wounding’ that acknowledges places of loss.

This article employs urban images and their narratives not only as an object of study but also as a methodological device. The dialectical approach challenges dominant urban images by ‘replying to one story with another’ (Hinterberger Citation2018, 454), a method shaped by the idea of ‘cultural kontakion’ (Warner Citation1994, 4). Thus, we explore art as a means of ‘memory care’ that holds the potential to foreground forgotten urban processes of erasure and loosen the grip of triumphant images over the erased cultural landscapes of host cities and nations.

Methodology: researching mega-event media and mediation

The authors analysed media associated with two former international expo sites in Australia; the Royal Botanical Gardens, site of the Sydney International Exhibition of 1879 and South Bank Parklands, site of Brisbane’s 1988 World Expo. These expo sites were selected for this article during a larger comparative study of sites in North America, Australia, and Japan (Minner, Zhou, and Toy Citation2022). Both the expo sites and case studies were selected with two key considerations in mind. First, they lend themselves to expanding the usually narrow temporal window of mega-event scholarship. Second, they reveal how the making of triumphal narratives might be challenged by revisiting the past in future public art and media initiatives.

The selection of Jonathan Jones’ barrangal dyara (skin and bones) was based on how a 19th-century expo site was used to challenge the primacy of past and prior imaginaries about Australia and Sydney through the placement of Aboriginal language and culture in the heart of a settler city. As well, barrangal dyara (skin and bones) was selected because it was high profile, well-received, and formed part of an international series of commissioned works that date to 1967 (O’Callaghan and Gowing Citation2020).

The second case in Brisbane was selected to illustrate how unearthing archival film associated with a largely underground, women-led feminist project has the power to offer a more nuanced understanding of suppressed protests against Expo 88. While Rogers and Ward’s City for Sale did not achieve high profile acclaim like the Sydney case, it illustrates the potential use of essay films to revive memories of demolition, erasure, and protest. In analysing other protest and documentary films from Sydney and Brisbane, the authors decided to focus on one key film for this article.

Research involved field visits in Sydney and Brisbane two times between 2016 and 2018 to observe and photo-document the sites and the publicly extant remnants of the expos and interpretive media. In addition, the authors collected documents from the Brisbane City Archives and the State Library of Queensland archives; analysed contemporary news, planning documents, and online media from the 1980s to 2020s; and performed interviews pertaining to both sites and cases. Jonathan Jones was interviewed in 2018. Later, the authors organised an artist-in-residence visit in upstate New York for Jones in 2019. The residence enabled further exchange about his public art projects related to Indigenous cultures and histories. A Skype interview was conducted with Wendy Rogers. Interviews were also conducted with Stephen Stockwell, Debra Beattie, and Pat Fiske, who directed independent essay films about Brisbane, either in resistance to or remembrance of Expo 88. Although no specific reference is made to the latter three interviews, they provide important background and directly inform other research projects (Abbott and Minner Citation2019). To understand the overall history of Expo 88 and public history at South Bank, additional interviews were conducted in Brisbane with: the Mayor of Brisbane from the time of Expo 88; a South Bank Authority official; representatives from two development companies; an experienced urban planner in private practice; and a long-time resident associated with Expo 88, who is a prominent advocate for public art and history associated with it. A focus group interview was also conducted with seven people knowledgeable about the South Bank precinct and who were associated with Queensland Shelter, an affordable housing advocacy organisation.

Conjuring the outline of a mega-event memory from the erasures of colonial Australia

In 2016, fifteen thousand Aboriginal broad shields were laid out on the grounds of Sydney’s Royal Botanic Garden by Aboriginal artist Jonathan Jones. Aerial photographs of barrangal dyara (skin and bones) show sweeping views of the public art installation’s ambitious scope. Through Jones’ careful placement of the shields, these images also show the outline of a long absent structure, the Garden Palace that housed the Sydney International Exhibition of 1879 (see ).

Figure 1: Kaldor Public Art Project 32: Jonathan Jones’ barrangal dyara (skin and bones), gypsum, kangaroo grass, 8-channel soundscape, dimensions variable. Installation view showing architectural footprint of the 1879 Garden Palace, Royal Botanic Garden, Sydney, 17 September–3 October 2016. Photo: Pedro Greig.

This art project created a public spectacle to revisit the boundaries of Australia’s urban history. The Sydney Morning Herald announced: ‘Sydneysiders awoke this morning to find the heart of their city had been taken over by one of the biggest art installations the city has ever seen’ (Galvin Citation2016). The Guardian described Jones’ project as a massive installation uniting Indigenous and settler histories (Sebag-Montefiore Citation2016). barrangal dyara (skin and bones) was the 32nd project in the Kaldor Public Art Projects (KPAP). The KPAP series was initiated in 1967 to bring international artists to Sydney to transform public spaces and change ‘the landscape of contemporary art in Australia with projects that resonate around the world’. In 1969, Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Wrapped Coast was not only the first in the series but also the ‘first large-scale public art project presented anywhere in the world’ (KPAP, Citationn.d.). Jones was the first Australian artist in KPAP’s history.

The installation’s related programming and educational events invited participation in public dialog through a story arc. This arc begins at the site’s Aboriginal origins, pauses in Victorian era empire building, oppression, and loss, and starts afresh through the persistence and regeneration of Aboriginal cultures and languages in contemporary times.

The Sydney International Exhibition asserted the British empire’s goal was to ‘civilise’ an uninhabited, distant land—under the justification of terra nullius—in its cultural image. As the first, albeit unofficial, international exhibition held in the southern hemisphere, the exhibition was crafted to: ‘elevate and ennoble’ Sydney’s urban landscape to the world; and suppress the natural environment and Aboriginal cultures and their ties to country, which inhibited urban elites’ idealised visions for the harbour city (Orr Citation2007, 1). The more-than-one-million visitors estimated to have attended the event was significant for a city then home to 200,000 people. The Commissioners of the Sydney Exhibition noted the event ‘undoubtedly emphasised a new era in the history of the Colony, and projected the value of Australia on the minds of the inhabitants of those older countries’ (Noyce Citation2015, 295). However, the colonisation of the vast island continent and Sydney’s coming-of-age exhibition, misrepresented 65,000 years of Aboriginal inhabitation.

Counteracting this omission, the shields of Jones’ art installation laid bare for all to reconsider the memory of the Garden Palace. Inside the Garden Palace were all manner of pavilions and courts meant to impress, entertain, and educate the masses. The Ethnological Court, for example, was described as ‘the first of its kind’ (Accarigi Citation2016, 133). It contained a panoply of Aboriginal artefacts, consisting mostly of meticulously displayed weaponry. This curated collection portrayed Australia’s Aboriginal people as warring, savage, and on their way to extinction. Among the knives, axes, spears, and skins were human remains, including skulls and other bones (McKay Citation2004). Accarigi (Citation2016, 133) describes the Ethnological Court as:

a transcultural zone where Indigenous material culture and white Australian imagination met, and in reference to the work of cultural historian Silvia Spitta, the objects exhibited at the Garden Palace over 1879–80 can be understood to have entered the order of things of Australian imagination and epistemologies and to have created a rift, destabilising known categories.

The so-called palace of culture was a racialised stab at superiority and control, and not only against Aboriginal Australians. Women, too, were present in Sydney ‘as exhibitors at a significantly higher rate’ than in similar European and American events of the time (Orr Citation2011). Yet their craftwork was viewed as ‘inferior’ compared to the industrial objects on display in other courts. Just a few years after the exhibition the Garden Palace burnt to the ground in a fire; destroying precious human remains and Aboriginal cultural objects.

The Garden Palace and the transcultural history it represents had been largely left out of mainstream white-Australian public imagination. This memory was revived by Jones, a member of the Kamilaroi and Wiradjuri nations of south-eastern Australia. Jones is by no means the only Indigenous artist to challenge settler-colonial accounts of urban history. Indigenous people around the world have struggled against a history of genocide and settler colonialism that has wilfully attempted to render their rights within cities invisible. Blatman and Porter (Citation2019, 31) write:

urban centres large and small are the focus of generations of Indigenous struggles for land justice, recognition, and cultural survival. Evidently, erasure is a logic abridged by continued Indigenous presence and resurgence. Such dimensions reveal that the process of ‘settling’ Indigenous lands is contemporary, persistent and present. Settler colonialism is still creating its spaces.

This case study is an example of a much larger body of presence and resurgence that seeks to challenge erasures characteristic of settler colonial urbanism. Jones’ public artwork aimed to foreground Aboriginal languages and cultures’ deep sense of belonging within the contemporary city.

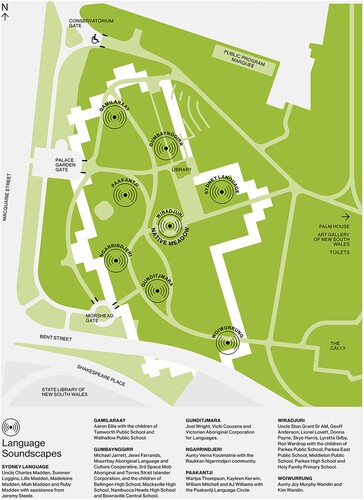

While barrangal dyara (skin and bones) is striking in aerial views, Jones meant it to be a participatory experience on the ground among multiple and overlapping communities.Footnote2 Soundscapes (see ) within the installation broadcast repeating words in Aboriginal languages. ‘Invigilators’, an important role performed primarily by Aboriginal university students, were situated around the installation to interact with members of the public (Interview with Jonathan Jones, January 8, 2018). They were not given scripts with which to docent the artwork. Instead, they were asked to share their thoughts on the installation with passers-by according to their own inspiration on the day.

Figure 2: Kaldor Public Art Project 32: Jonathan Jones’ barrangal dyara (skin and bones), from project guide.

Additional performances and lectures by Aboriginal elders and many other speakers, sought to expand engagement with the public on a variety of intersecting topics, including Indigenous knowledges and environmental and social histories. The effect was to reclaim the Royal Botanic Garden and inform new narratives about Aboriginal culture and history on the traditional lands of the Gadigal people.

In the exhibition catalogue documenting the project, Emma Pike (Citation2016, 32) writes:

The question of ‘erasure’ has remained omnipresent throughout the project’s development. How can a nation collectively forget such a significant story, a building so crucial to understanding our past and present cultural concerns? And if we have forgotten such a monument, what other vital episodes of our history have we happily ignored?

the idea of skin and bones was really kind of thinking about the landscape … as a corporeal identity. This idea that there is sort of a physical presence within the landscape; that the landscape has this skin and bones embedded in it. But it could also be something as simple as this idea that history has been malnourished to the point where it is literally just skin and bones.

The landscape installation’s 15,000-shield spectacle was a means of ‘re-wounding’ past traumas (Bowring Citation2017). Reinscribing the Garden Palace’s built footprint onto the landscape had the effect of ‘presencing’ the Other loss of Aboriginal artefacts, human remains, and culture that were destroyed when the building burned. The installation also draws attention to contemporary issues of Aboriginal dispossession in the time since white settlement. Writing about the design of sites of remembrance, Bowring (Citation2017, 116) notes the importance of care and empathy at sites of trauma, which are necessary for healing. In this case, public art becomes a healing treatment through the act of tending to past traumas. An aspect of this healing can be seen in the care Jones took to bring together Aboriginal communities to participate in the making of the public art project, including the making of shields, recordings for soundscapes, and programming.

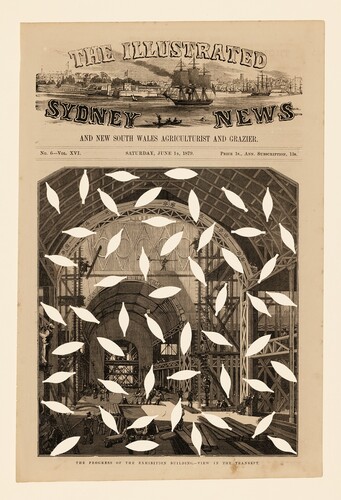

Figure 3: Jonathan Jones, Garden Palace suite 2016. Hand-cut 19th-century newspaper etching. Dimensions variable. The progress of the exhibition building—view in the transept, published in The Illustrated Sydney News and New South Wales Agriculturalist and Grazier, 14 June 1879, p. 1; dimensions variable approx. 40 × 26.8 cm sheet. Created to accompany Jonathan Jones: barrangal dyara (skin and bones), Kaldor Public Art Project 32, Royal Botanic Garden Sydney, 17 September–3 October 2016. Photograph Mark Pokorny. Collection of the artist.

As part of barrangal dyara (skin and bones), a native grassland was planted, roughly where the monumental Garden Palace dome is thought to have been located. At the conclusion of the exhibition, the grassland was retained, becoming a permanent marker to the cultural significance of the site to Aboriginal Australians, and speaks to healing and remembrance after the fire.

An intriguing interaction occurs where the boundary of the shields approached the statue of the first governor of New South Wales (see ). The monument to Governor Phillip is itself a small spectacle with a prominent storyline. The statue was intended to shape meaning and national pride and thus represents a dominant narrative of control. Like the exhibition of 1879, the monument constructs a narrative through site and seeing. Jones’ installation, which encircles this stratified space, is an alternative narrative to the modern imagery of Sydney that is heavily dominated by stories of white settlement.

Figure 4: Kaldor Public Art Project 32: Jonathan Jones’ barrangal dyara (skin and bones), gypsum, kangaroo grass, 8-channel soundscape, dimensions variable. Installation view showing architectural footprint of the 1879 Garden Palace, Royal Botanic Garden, Sydney, 17 September–3 October, 2016. Photo: Pedro Greig.

Barrangal dyara (skin and bones) offers a means of considering how lost memories might be more than simply remembered; public art can become a forum for processing memory. Notably, this instance of ephemeral but well-documented historical interpretation leaves not only a restored native grassland in its wake but also lingers in the urban memory of Sydney. This living form of heritage interpretation contrasts with a static plaque or monument.

South Bank: a forgotten riverbank re-emerges in world-class Brisbane

Archival film, another form of public art, can also conjure memories that complexify the history of mega-events and host city amnesia. In October 2015, the State Library of Queensland (SLQ) presented the newly digitised 16 mm film City for Sale on its blog to mark UNESCO’s (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) World Day for Audiovisual Heritage. The SLQ translated UNESCO’s theme, ‘Archives at Risk: Protecting the World’s Identities', into action by digitising archival materials ‘that reflect the culture and history of Queensland’ to preserve the identity of Brisbane’s collective memories (Wong Citation2015). The SLQ’s audio-visual conservator Swee Cheng Wong (Citation2015) noted: ‘City for Sale is a short film about the demolition of buildings in the Brisbane CBD in the lead up to EXPO 1988, and includes short anecdotes about buildings and areas by several people affected by the demolition.’ Although no specific rationale was given for why this film was selected, the images of destruction from the 16 mm film revive memories of the rampant destruction and social upheaval that took place in Brisbane’s downtown and southern inner-city neighbourhoods in preparation for the late 20th-century expo held to celebrate the bicentennial of white settlement. The SLQ also features City for Sale in its ‘political persuasions’ collection. This collection houses digital stories that provide ‘insight into decisions that impacted on Queenslanders and the decisions to recognise the rights of people in society’ (SLQ, Citationn.d.).

In contrast to this archival film, Brisbane’s locally well-known triumphal narrative tells of how World Expo 88 reinvented the city. Expo 88 is described as ‘a social and cultural epiphany’ (Ganis, Minnery, and Mateo-Babiano Citation2014, 503). The mega-event transformed Brisbane into a ‘new world city’ that is ‘positioned on the world stage as vibrant, dynamic and innovative’ (Beanland Citation2016, 1). Compared to other Australian cities like Sydney, Brisbane was an unlikely host of Expo 88, especially one that commemorated Australia’s bicentenary. Yet through sheer will and political manoeuvring the ‘expo defied problems, precedents, and pundits to become the largest, longest, and loudest of Australia’s bicentennial events' (Ryan Citation2018, e-book location 5239).Footnote3 As oft-repeated images now proselytise, Brisbane is a world-class city.

More than thirty years after Expo 88, triumphal narratives and imagery still pervade media representations and remembrances of this mega-event (see Pappalardo Citation2018). Confronting this legacy are Expo histories exposing the raw underbelly of corruption in Brisbane during the 1980s (Ryan Citation2018) and several other essay films that resisted top-down urban development practices (see Beattie Citation1984; Moffatt and McGrady Citation1982; Stockwell Citation1985). Building on this resistance, we draw attention to practices of care for expo memories that, in the process, re-expose filmic landscapes of social upheaval and loss that counteract mega-event amnesia. The ‘painstaking task’ of digitising archival film reels by the SLQ (Citation2019) is an exemplar of how to care for community memories. The SLQ’s initiative, which expanded access to and awareness of an archival film that protests the loss of community in preparation for Expo 88, contests Brisbane’s urban image by making this alternative narrative widely accessible to new audiences.

The digitised film City for Sale: Images in the Modern City became an urban memory recalled from the archive; a story that could be re-presented in an accessible format to the public. Originally launched at Jagera Community Hall in Musgrave Park, an important site of protest for the Aboriginal community that is two blocks from South Bank, the site of Expo 88, the film has never been broadcast (Interview with Wendy Rogers, December 11, 2018). After Expo 88, it was screened on several occasions at the SLQ, and the Story Bridge Hotel, among other independent film nights in Brisbane. City for Sale has also been screened for contemporary audiences, but it has neither received high profile attention nor critical recognition like barrangal dyara (skin and bones). While the film did not receive critical acclaim, it contributed to a community that pushed back against an oppressive state government that was intent on censoring local culture and dissenting voices (Interview with Wendy Rogers, December 11, 2018). The film’s digitisation attests to its local significance, the potential for wider impact, and potential to revive community memory through film.

Co-directed and co-edited by Wendy Rogers and Sue Ward, City for Sale visually eulogises a period of rapid change in Brisbane at a time before the wrecking balls tore apart the Expo 88 site. Twelve minutes in length, the film offers visceral scenes of demolition and development in downtown Brisbane and the inner-city neighbourhoods of South Bank and West End in the lead up to Expo 88 (see ). There are also shots of newly constructed skyscrapers from the 1980s and their sterile plazas. Little disguises the sale of a city to corporate investors spurred on by government hype surrounding Expo 88.

The film emerged from a women’s film workshop known as Film Facts. Rogers and Ward organised a programme of workshops in response to the ‘glaring lack’ of women in a male-dominated film and television industry (Interview with Wendy Rogers, December 11, 2018). The goal of these feminist filmmakers was to get more women into the industry by training women in the practice of film-making. According to Ward, the workshops were productive endeavours because women supporting women ‘built confidence’ amongst participants (stARTters mag Citation1989). The output from the Film Facts workshop produced three films: (1) Going About Your Business, which was later developed into City for Sale with more funding from the Australian Film Corporation; (2) Chooks; and (3) On Edge. Recognition of the workshop’s output by industry press highlights the wider appeal and desire to visually capture and contest this period of rapid physical development and social change in Brisbane.

City for Sale is interspersed with narrated glimpses of a Brisbane recently past. In the opening shots, a long-time resident narrates: ‘Money doesn't mean anything to me … I'm too old for money. It doesn't mean a thing to me, money now’ (Ward and Rogers Citation1988). Continuing, the narrator indicates her reluctance to relocate elsewhere, let alone move into this new urban world. Later, another woman’s voice asks: ‘what happens to the people when they demolish these buildings to make way for expo?’ The film then cuts to scenes of bulldozers and construction workers tearing down old buildings, which were to be replaced with skyscrapers. The film mourns the loss of a past urban fabric and raises the question of who has the right to live in downtown Brisbane (see ). Reciting the words to a poem she wrote about Brisbane in the 1980s, Megan Redfern intones: ‘This is not a city, merely a collection of random spaces. The remnants of an empty shell’ (Ward and Rogers Citation1988).Footnote4 Images of the triumphant city and derelict neighbourhoods barren of worth are challenged by narratives and collective memories now found in the archive.

The clearance of Brisbane’s 19th- and early 20th-century physical fabrics and the displacement of people to make way for Expo 88, and their resistance to this, have been largely erased. City for Sale, among several other essay films focused on 1980s Brisbane, demonstrates the resistance that stood against this destruction (Abbott and Minner Citation2019). The film challenged the rhetoric of politicians and boosters of Expo 88 who said repeatedly that South Bank was not valuable. The film’s ‘powerful’ contribution, according to a Brisbane newspaper, was to highlight the lack of opportunity for the people of Brisbane to have a say in what was happening to their city (Hooper Citation1987). This contribution stands out because the government and civic elites ignored the reality that South Brisbane was not empty. South Bank and West End were inhabited by, and important to, the everyday lives of residents, workers, and others who frequented these neighbourhoods. The film brings into focus people and their memories of a changing post-industrial landscape, which was home to diverse working-class neighbourhoods with strong Indigenous and immigrant communities. For example, Greenop and Memmott (Citation2007) describe networks of ‘beats’ important to Aboriginal people. These hotels, pubs, and other meeting places, particularly Musgrave Park were important sites for community gathering and protest over Indigenous land rights prior to and during Expo 88.

The contemporary landscape of South Bank since Expo 88 has been thoroughly transformed with public and private investment. The ‘derelict riverbank’ is now a wealthy and leafy riverfront neighbourhood (Smith and Mair Citation2018). Today this landscape favours construction cranes, luxury, mixed-use towers, and prominent cultural institutions. South Bank borrows from countless other examples of world-class urban development; it even boasts a big-town Ferris wheel. This landscape draws hordes of tourists and locals alike. For those who can afford it, Brisbane’s whole-hearted embrace and legalisation of outdoor dining since Expo 88 is a memorable feature (Interview with Sallyanne Atkinson, December 12, 2017). These spaces of leisure and consumption make the destruction of the South Bank and West End communities and a portion of the central business district, literally, more palatable. It is thus not only destruction, but also opportunities for consumption that erase the more troubling history of land resumptions and demolitions. City for Sale problematises Brisbane’s triumphal image of progress and prosperity. Moreover, the film’s digitisation renews and reinforces contemporary concerns about how inner-city neighbourhoods can be sold for profit and how historical communities are forgotten.

Remembering mega-event erasures as a form of memory care

The Sydney and Brisbane case studies presented in the previous two sections show how public art and archival film can resist the long afterlife of mega-event amnesia. In contesting the memory of mega-events, they hold the capacity to reveal past processes of erasure. The act of remembering a mega-event differently becomes a process of memory care. Both cases demonstrate how art can counteract the selective erasure of communities and cultural artefacts caused by triumphal image-making, and the subsequent suppression of protest movements and acts of resistance from collective memory. While the art of resistance can combat triumphal image-making, it is important to acknowledge that how they agitate for change is also tied to their uptake in society. Together, the cases complexify how we engage with the linear history of mega-events by making the memory of places and communities available to new audiences. In this way, they demonstrate more than just ‘symbolic’ resistance.

Mega-event celebrations are designed to focus the public’s attention and imagination in targeted ways. In Sydney and Brisbane, expos functioned as markers of time and were staged to remember significant milestones of white settlement. As idealised versions of the past and future, they functioned as vehicles to reimagine host cities, recast social landscapes, and construct new reputations globally. However, the deleterious impact of top-down change renders certain communities powerless. Inhabitants, Wendy Rogers (2018) reflected, ‘go back to the[ir] place [in the city] and think: “I don’t have any connection here anyway. Why should I care?” It's like a domino effect, [first] dissociation from your environment and [then] actually who you are’ (Interview with Wendy Rogers, December 11, 2018). The agency derived from belonging to a community from a particular place catalyses care for how their place in the city is remembered. Recognising this magnifies the resonance of Jones’ installation, which attends to racial injustices from over 130 years ago.

The contours of a mega-event bring multiple contradictions to the fore. For example, the inherent tension between forces that promote cultural diversity and exchange and top-down urban development practices that make planning for these events possible, simultaneously results in the homogenisation of host cities outside the event. This leads to the displacement of peoples and cultures from collective memory. Speaking to the erasure of cultural landscapes at South Bank (site of the 1951 Festival of Britain), Australian artist Fiona Foley foregrounds these tensions at South Bank in Brisbane, the site of Expo 88. Foley (Citation2012, 57) writes:

When the landscape at South Bank could easily be substituted for South Bank, London, then something is amiss. What makes it different from any other place in the world? The answer is obvious … it’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Culture. [But] when Brisbane’s South Bank is visually barren of Indigenous art it says to me and any other visitor that you do not value, respect or take pride in the original nations you replaced.

International exhibitions are thus complex vehicles for storytelling, especially in the contradictory ways that they promote and mediate cultural encounters. Both the 19th- and 20th-century Australian exhibitions represented Aboriginal people and culture. At the 1879 exhibition, white Australians retained control over the presentation of Aboriginal culture, selecting and ordering Aboriginal weapons in the Ethnological Court. In the 20th century, participation in the expo was debated among Aboriginal people. Some Indigenous artists and performers went to great lengths to represent Aboriginal cultures, while others protested the expo and discouraged any involvement (Morrissey Citation1988; Ryan Citation2018). In contrast to the 19th century, Expo 88 did allow some Aboriginal control over the narratives about Indigeneity presented, and protests and organising provided a means to further Aboriginal rights. While Aboriginal culture was included for its entertainment value, Aboriginal peoples’ right to the city was disregarded. At both expos, Aboriginal people were removed from their lands to make way for urban development.

The two cases also demonstrate how communities can remember differently. While some literature on mega-events considers memory (Davis Citation2011) and other sources speak to erasure and displacement (Broudehoux Citation2017; Broudehoux and Monteiro Citation2017), a paucity of scholarship substantiates growing critiques over community displacement and dispossession with a view to suggesting why and how we should remember, and how to make-sense of those communities that have been erased. In the Sydney and Brisbane cases, the violence is mirrored during the construction of urban spaces that are designed with the intention to exclude and forget certain peoples. In Sydney, Victorian period displays erased the storied histories of Aboriginal peoples wholesale. Whereas Brisbane underscores the cultural violence that often accompanies the wrecking ball’s destructive impact on built environmental heritage.

Both cases highlight how art can expose the violent practices that shape mega-event amnesia. They demonstrate this by reviving memories of tangible destruction of communities and attempts at their cultural erasure. In the case of barrangal dyara (skin and bones), Jones constructs new public landscapes as a form of memory care. City for Sale offers a subtle example of memory care. As one of several 1980s Brisbane essay films, it challenged the triumphal narrative of Brisbane’s Expo 88. The care of memory remains evident in the making of the film, by capturing and challenging erasures of working-class communities through demolition and commercialisation of the city core. Digitising this film offers the potential to revive past traumas that remember the staging of Expo 88 differently. City for Sale also asserts rights to the city, and is itself an artefact of an assertion of women’s rights to participate in film and media. While its potential is more latent, the film highlights a past and continuing model of unsustainable development. This could yet be challenged by remembering the communities who once had stronger claims to the now wealthy tourist enclave built on the South Bank shore.

The archive is central to both the Sydney and Brisbane cases and integral to our study of them. Jones’ barrangal dyara (skin and bones) was derived partially from the void in the historical record that he noted while researching his family history. This void led the artist to deeply reconsider the historical materials that did exist in the archive and to generate new public meaning from this research. The outline of the Garden Palace invokes this void and conjures the settler-colonial practices that erased his family history. The archive fuelled his artistic revival of Aboriginal languages and cultures in Sydney’s urban core. In contrast, the Brisbane case was born of finding a recently digitised and newly accessible 16 mm film. Care, consideration and even the maintenance and repair foisted on the archive has power to reshape culture and history in the present through access and reinterpretation. However, there are limits. While guidelines and best practices manage archives and the preservation of historical objects, stories of resumption and protest can remain submerged beneath dominant images that shape what is deemed worthy of preservation in the first place. A future line of inquiry could take such guidelines and best practices as a starting point to consider whose memories are preserved to counteract the erasure from urban memory of communities and cultural artefacts by narratives of unequivocal success.

In reflecting on the positionality of the archive, the central role of cultural institutions in caring for community memories is foregrounded. Cultural institutions have been essential to reconstructing urban memories because what they choose to fund, and don’t, matters to the social life of memory in the city. These institutions include the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and Kaldor Public Art Projects, the Australian Film Commission, and the State Library of Queensland, among other organisations and programmes funded through both public funds and private philanthropy. There is significance to the fact that a state library would tend to the history of protest. In this small way, the SLQ’s initiative to digitise archival film shows how public agencies can nurture cities by caring for the memory of marginalised citizens. Additionally, the ways in which media participates in representing urban spectacles aimed at reflecting alternative and counter-narratives matters to the past and future of the city, especially in view of the long social legacies of these mega-events.

Finally, in considering both Brisbane and Sydney, it remains an open question as to how populations evicted from affordable housing and dispossessed of their homelands can be invited to re-inhabit the high-priced real estate of Australia’s global cities in the 21st century. To actualise and learn from the deconstruction of images, the processing of memory care must be translated into social and political action to redress past harms. To be more than simply a performative gesture, public memory must feed social movements and urban policy reforms that claim rights to the city for those who have been expelled through processes of urban erasure.

Conclusion: recovering from collective amnesia

This article has illustrated how images, stories, and mega-event spectacles that help to produce and elevate them, are used to construct a collective identity for a host city. Triumphal images subjugate the grammar of difference and diversity that make cities desirable places for many people to live together. Urban images that are promoted in the interest of constructing an idealised future, in fact, displace whole communities, people, language, and culture behind the illusion of mega-event success. These images not only shape the physical spaces of cities but the minds and memories of their inhabitants.

Through two case studies of expos in Australian cities, the article showed how public art and archival film can be used to challenge triumphal images and recover the memory of places and communities in a way that makes the actions of previous inhabitants and their attachments to place visible to new audiences. These alternative narratives become a form of memory care in which resurfacing the painful process of erasure challenges Imperial era city-making in 19th-century Sydney and more recent top-down planning associated with staging Expo 88 in Brisbane. The recognition of expos, (bi)centennials, and other milestones by a large proportion of the population is worth reflecting on further; they represent the ‘skin and bones’ upon which richer interpretations of urban history and historical consciousness might be regained. Historical markers, therefore, might be the first place to target for ‘memory care’ or a form of reprocessing of past erasures and traumas.

In both cases, art is instructive to how the past can be narrated differently to raise awareness of prior loss, injustice, and instil a deeper sense of time and place. While specific to Australia, they are relevant to other host cities. Imagine if every former host city activated public memory at their mega-event site together. The effect could reclaim suppressed histories globally and revitalise urban memory locally by reconnecting residents to their city’s storied past and present.

Cities can be repopulated with richer histories of place through art and archival film. We note that these alternative narratives must be performed and reperformed; resituated for living communities. Storytelling requires human-to-human communication because conservation of the built environment in no way ensures the memory of communities will be preserved in situ over time. The urban images constructed through the temporal arc of storytelling hold the power to not only erase memories of places and communities; they equally narrativise a grammar of possible paths that envision collective remembrance and a plurality of memories as the foundation for urban futures. The alternative narratives of a mega-event enriched through a historical consciousness of place and community illustrates how the art of resisting mega-event amnesia can guide efforts to reconstruct urban memories.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers as well as friends and colleagues who provided thoughtful and sharp feedback that improved this paper no end. An early version of this paper was presented at the 2018 Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning annual conference. Many thanks to Jonathan Jones and Wendy Rogers for their participation in this research project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Martin Abbott

Martin Abbott is a PhD candidate in the Department of Science and Technology Studies at Cornell University. Email: [email protected]

Jennifer Minner

Jennifer Minner is the Director of Graduate Studies and an Associate Professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning at Cornell University. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 While the Sydney Olympics spring to mind as the preeminent mega-event in a contemporary Australian context, this may reflect a preference for global sport rather than expos (Viehoff and Poynter Citation2015). This preference also reveals the exemplary work of the Olympics’ triumphal imagery in overshadowing the import of other mega-events to city making and nation building.

2 See Minner (Citation2019) for further discussion of this public art installation.

3 Brisbane’s World Expo 88 is preceded by the Melbourne Centennial Exhibition of 1888, which marked 100 years of white settlement in Australia.

4 Redfern’s (Citation1995) poem was later published as ‘Brisbane Elegy.’

References

- Abbott, Martin, and Jennifer Minner. 2019. “How Urban Spaces Remember: The Essay Film as Archive for Protest and Resistance.” Paper presented at the City, Essay, Film Symposium, University College London, London, UK, June 2019.

- Accarigi, Ilaria Vanni. 2016. “The Ethnological Count at the Garden Palace.” In Barrangal Dyara (Skin and Bones), edited by Jonathan Jones, 136–141. Lilyfield: Kaldor Public Art Projects .

- Adese, Jennifer. 2016. “‘You Just Censored Two Native Artists’: Art as Antidote, Resisting the Vancouver Olympics .” Public 27 (53): 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1386/public.27.53.35_1.

- Alawadi, K. 2016. “The Evolving Landscape of Dubai’s National Housing Neighborhoods.” In Transformation: The Emirati National Housing, edited by Yasser Elsheshtawy, Tracy Grey, and Inas Souleiman, 116–141. Abu Dhabi: Salama Bint Hamdan Al Nahyan Foundation .

- Azuela, Antonio, Emilio Duhau, and Enrique Ortiz, eds. 1998. Evictions and the Right to Housing: Experience from Canada, Chile, the Dominican Republic, South Africa, and South Korea. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre .

- Baade, Robert, and Victor Matheson. 2017. “Understanding Drivers of Mega-Events in Emerging Economies.” In The Oxford Handbook of Mega Project Management, edited by Bent Flyvbjerg, 287–309. Oxford: Oxford University Press .

- Beanland, Denver. 2016. Brisbane: Australia’s New World City: A History of the Old Town Hall, City Hall and Brisbane City Council 1985–2013. Moorooka: Boolarong Press .

- Beattie, Debra. 1984. Expo Schmexpo [Film]. https://vimeo.com/362213144.

- Blatman, Thomas-Naama, and Libby Porter. 2019. “Placing Property: Theorizing the Urban from Settler Colonial Cities .” International Journal of Urban & Regional Research 43 (1): 30–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12666.

- Bowring, Jacky. 2017. “Looking After Things: Caring for Sites of Trauma.” In Care and Design: Bodies, Building, and Cities, edited by Rob Bates, Charlotte Imrie, and Kim Kullman, 116–137. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell .

- Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. 2004. The Making and Selling of Post-Mao Beijing. Planning, History, and the Environment Series. London: Routledge .

- Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. 2007. “Spectacular Beijing: The Conspicuous Construction of an Olympic Metropolis .” Journal of Urban Affairs 29 (4): 383–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2007.00352.x.

- Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. 2017. Mega-Events and Urban Image Construction: Beijing and Rio de Janeiro. London: Routledge .

- Broudehoux, Anne-Marie, and Joao Carlos Monteiro. 2017. “Reinventing Rio de Janeiro’s Old Port: Territorial Stigmatization, Symbolic Re-Signification, and Planned Repopulation in Porto Maravilha .” Revista Brasileira de Estudos Urbanos e Regionais 19 (3): 493–512. https://doi.org/10.22296/2317-1529.2017v19n3p493.

- Bryson, Jeremy. 2013. “Greening Urban Renewal: Expo ’74, Urban Environmentalism and Green Space on the Spokane Riverfront, 1965-1974 .” Journal of Urban History 39 (3): 495–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144212450736.

- Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions. 2007. Fair Play for Housing Rights: Mega-events, Olympic Games and Housing Rights: Opportunities for the Olympic Movement and Others. Geneva: Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions .

- Chan, Roger, and Lingyue Li. 2017. “Entrepreneurial City and the Restructuring of Urban Space in Shanghai Expo .” Urban Geography 38 (5): 666–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1139909.

- Davis, Lisa Kim. 2011. “International Events and Mass Evictions: A Longer View .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35 (3): 582–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00970.x.

- Dobraszczyk, Paul. 2017. “Sunken Cities: Climate Change, Urban Futures and the Imagination of Submergence .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41 (6): 868–887. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12510.

- Dutta, Ashirbani. 2007. Development-induced Displacement and Human Rights. New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications .

- Foley, Fiona. 2012. “I Speak to Cover the Mouth of Silence .” Art Monthly Australasia 250: 55–57. https://doi.org/10.3316/ielapa.201206603.

- Galvin, Nick. 2016. “Kaldor Public Art Projects Raises Garden Palace from the Ashes.” Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/kaldor-public-art-projects-raises-garden-palace-from-the-ashes-20160909-grcigj.html.

- Ganis, Mary, John Minnery, and Iderlina Mateo-Babiano. 2014. “The Evolution of a Masterplan: Brisbane’s South Bank, 1991–2012 .” Urban Policy and Research 32 (4): 499–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2013.877390.

- Gardner, Jonathan. 2022. A Contemporary Archaeology of London’s Mega Events from the Great Exhibition to London 2012. London: UCL Press .

- Gotham, Kevin. 2011. “Resisting Urban Spectacle: The 1984 Louisiana World Exposition and the Contradictions of Mega Events .” Urban Studies 48 (1): 197–214.

- Greenop, Kelly, and Paul Memmott. 2007. “Urban Aboriginal Place Values in Australian Metropolitan Cities: The Case Study of Brisbane.” In Past Matters: Heritage and Planning History: Case Studies from the Pacific Rim, edited by Caroline Miller and Michael Roche, 213–245. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing .

- Haraway, Donna. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press .

- Hinterberger, Amy. 2018. “Marked ‘h’ for Human: Chimeric Life and the Politics of the Human .” BioSocieties 13 (2): 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-017-0079-7.

- Hooper, Karen. 1987. “Film Team Out to Retain Part of City History .” Sunday Sun, August 23.

- Jones, Jonathan. 2016. Barrangal Dyara (Skin and Bones). Kaldor Public Art Projects. Sydney: Thames & Hudson .

- Jones, Jonathan. 2017. “Episode 5: Languages.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = ay8CbdDQVcA.

- Kaldor Public Art Projects. n.d. “About.” Kaldor Public Art Projects. Accessed December 23, 2023. https://kaldorartprojects.org.au/our-story/.

- Koch, Natalie. 2018. The Geopolitics of Spectacle: Space, Synecdoche, and the New Capitals of Asia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press .

- Langton, Marcia. 2020. “Ancient Sovereignty: Representing 65,000 Years of Ancestral Links to Land.” In NIRIN: 22nd Biennale of Sydney, edited by Brook Andrew, 64–65. Sydney: Biennale of Sydney .

- McKay, Judith. 2004. Showing off: Queensland at World Expositions 1862 to 1988. Rockhampton: Central Queensland University Press and Queensland Museum .

- Minner, Jennifer. 2019. “Assembly and Care of Memory: Placing Objects and Hybrid Media to Revisit International Expositions .” Curator: The Museum Journal 62 (2): 151–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12291.

- Minner, Jennifer, and Martin Abbott. 2019. “Conservation Logics That Reshape Mega-Event Spaces: San Antonio and Brisbane Post Expo .” Planning Perspectives 35 (5): 753–777. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2019.1585281.

- Minner, Jennifer, Grace Yixian Zhou, and Brian Toy. 2022. “Global City Patterns in the Wake of World Expos: A Typology and Framework for Equitable Urban Development Post Mega-Event .” Land Use Policy 119: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106163.

- Moffatt, Tracey, and Madeline McGrady. 1982. “We Fight (Guniwaya Ngigu)” [Film]. http://radicaltimes.info/HTML/popup503c2.html.

- Morrissey, Philip. 1988. “Restoring a Future to a Past .” Kunapipi 10 (1): 10–16.

- Noyce, Diana. 2015. “How Like England We Can Be: Feeding and Accommodating Visitors to the International Exhibitions in the British Colonies of Australia in the Nineteenth Century.” In A Taste of Progress: Food at International and World Exhibitions in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, edited by Nelleke Teughels and Peter Scholliers, 291–310. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing .

- O’Callaghan, Genevieve, and Mark Gowing, eds. 2020. Making Art Public: Kaldor Public Art Projects, 1969–2019. Lilyfield: Kaldor Public Art Projects .

- Orr, Kirsten. 2007. “An Exhibit Calculated to Elevate and Ennoble: Celebration and Suppression of Natural Landscape in Nineteenth-Century Urban Visions of Sydney.” Paper presented at the ‘XXIVth Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand,’ Adelaide, Australia, September 21–24.

- Orr, Kirsten. 2011. “Women Exhibitors at the First Australian International Exhibitions .” Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 12 (3). https://muse.jhu.edu/article/463347.

- Pappalardo, Annie. 2018. “Expo 88: Revisiting Memories of Brisbane's Defining Moment 30 Years On.” ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-04-30/expo-88-30-year-anniversary-revisiting-memories/9702588.

- Parmett, Helen Morgan. 2022. “The Sportification of Place: Governance, Mediatization, and Place-branding through the Stadium.” In The Routledge Companion to Media and the City, edited by Erica Stein, Germaine R. Halegoua, and Brendan Kredell, 134–144. London: Routledge .

- Pike, Emma. 2016. “Introduction: Barrangal Dyara (Skin and Bones).” In Barrangal Dyara (Skin and Bones), edited by Jonathan Jones, 31–41. Lilyfield: Kaldor Public Art Projects .

- Powell, Hillary, and Isaac Marrero-Guillamón, eds. 2012. The Art of Dissent: Adventures in London’s Olympic State. London: Marshgate Press .

- Redfern, Megan. 1995. “Brisbane Elegy.” In Tales My Mother Never Told Me, 42. Brisbane: Metro Press .

- Roche, Maurice. 2017. Mega-Events and Social Change: Spectacle, Legacy and Public Culture. Globalizing Sport Studies. Manchester: Manchester University Press .

- Ryan, Jackie. 2018. We’ll Show the World: Brisbane’s Almighty Struggle for a Little Bit of Cred. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press .

- Saab, A. Joan. 2007. “Historical Amnesia: New Urbanism and the City of Tomorrow .” Journal of Planning History 6 (3): 191–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513206296409.

- Sandercock, Leonie. 1998. Towards Cosmopolis: Planning for Multicultural Cities. Chichester: J. Wiley .

- Sandercock, Leonie. 2003. “Out of the Closet: The Importance of Stories and Storytelling in Planning Practice .” Planning Theory & Practice 4 (1): 11–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464935032000057209.

- Sebag-Montefiore, Clarissa. 2016. “Jonathan Jones Unites Indigenous and Settler History in Massive Public Artwork in Sydney.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/sep/30/lost-in-the-flames-sydneys-garden-palace-resurrected-through-indigenous-eyes.

- Shin, Hyun Bang. 2012. “Unequal Cities of Spectacle and Mega-Events in China .” City 16 (6): 728–744. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2012.734076.

- Simone, AbdouMaliq, and Edgar Pieterse. 2017. New Urban Worlds: Inhabiting Dissonant Times. Cambridge: Polity Press .

- Smith, Andrew, and Judith Mair. 2018. “Celebrate ‘88: The World Expo Reshaped Brisbane Because No One Wanted the Party to End.” The Conversation, August 29. https://theconversation.com/celebrate-88-the-world-expo-reshaped-brisbane-because-no-one-wanted-the-party-to-end-95430.

- stARTers Magazine. 1989. “Film Facts: Women and Film.”

- State Library of Queensland. 2019. “Preserving Queensland's Cinematic Heritage: Reel Rescue.” State Library of Queensland, May 31. https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/blog/reel-rescue.

- State Library of Queensland. n.d. “Political Persuasions.” State Library of Queensland. Accessed May 30, 2024. https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/collections/queensland/political-persuasions.

- Stockwell, Stephen. 1985. This City is Dead [Film]. https://remix.org.au/portfolio_page/video-the-city-is-dead-part-one-stephen-stockwell/.

- Viehoff, Valerie, and Gavin Poynter. 2015. Mega-Event Cities: Urban Legacies of Global Sports Events. New York: Routledge .

- Ward, Sue, and Wendy Rogers. 1988. City for Sale [Film]. https://vimeo.com/143218600.

- Warner, Marina. 1994. Managing Monsters: Six Myths of our Time: The 1994 Reith Lectures. London: Vintage .

- Wong, Swee Cheng. 2015. “UNESCO World Day for Audiovisual Heritage—Archives at Risk: Protecting the World Identities.” October 27. http://blogs.slq.qld.gov.au/jol/2015/10/27/unesco-world-day-for-audiovisual-heritage-archives-at-risk-protecting-the-world-identities/.

- Zitcer, Andrew, and Salina Almanzar. 2020. “Public Art, Cultural Representation, and the Just City .” Journal of Urban Affairs 42 (7): 998–1013. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2019.1601019.