Abstract

Business parks are a ubiquitous feature of city-edge development. They have attracted attention for their lack of sustainability, spurring interest in how they can be reconfigured or reimagined in the face of ecological collapse and social fragmentation. Inspired by calls to notice everyday practices at the city edge (Tzaninis et al. 2021. “Moving Urban Political Ecology Beyond the ‘Urbanization of Nature’.” Progress in Human Geography 45 (2): 229–252; Tsing 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press; Gandy 2022a. “Ghosts and Monsters: Reconstructing Nature on the Site of the Berlin Wall.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 47: 1120–1136.) and drawing on data from a participant-led photography exercise at a suburban business park in the north-east of England, this article explores how workers employed at businesses on the park engage with and value its natural assets. We set out from Tzaninis et al.’s (2021) contention that the dominant framing of suburbia as ‘non-place’ or ‘no man’s land’ has the effect of denying the many intriguing practices unfolding at the city’s edge. Resonating with Tsing (2015), we highlight the significance of everyday interaction with nature in an ecologically vulnerable landscape as a creative, open-ended and, potentially, hopeful process. Focused on denizens of the business park, our data draws attention to the possibilities and potentialities of more-than-human encounters, the feeling of tranquillity generated by green spaces, and the sense of freedom that derives from bodily movement in a natural setting. These open-ended practices are distinct from, and ‘other than’, the dominant way of doing business in the park. Such encounters, drawn out by auto-photography, foment a radical connectedness with nature through which a powerful sense of custodianship and responsibility can find expression.

Introduction

Business parksFootnote1 are a ubiquitous feature of UK and global city-edge development, supporting a range of light manufacturing, retail, and office functions.Footnote2 Car-centric and alienating, these spatial formations have been criticised for their ‘placelessness’ and lack of sustainability (Relph Citation1976; Augé Citation2008; Dunham-Jones and Williamson Citation2009). Yet, as Tzaninis et al. (Citation2021, 240) argue, relegating the city edge and its processes to the realm of ‘non-place’ has led to a certain ‘blindness’ in the urban studies literature towards suburban solutions to ecological problems.Footnote3 As Martin (Citation2008, 379) asserts in this journal, the city edge elicits ‘fresh narratives’ (Sinclair Citation2003, 16) that challenge and go beyond those evoked by urban centres.

Focused on the everyday interactions with nature of those who work at Team Valley Trading Estate (TVTE), a large and historically significant business park in the north-east of England, we explore how nature-based auto-photography uncovers and gives voice to radical narratives that counter dominant urban development agendas and policies. Resonating with recent scholarship on auto-photography in City (Jiang and Kobylinska Citation2020; Rozena Citation2023) and wider literature on sensory methods (Pink Citation2015), we argue that auto-photography can help workers who spend a considerable part of their lives in the business park to explore and make sense of their relationship to its outdoor spaces (and the world beyond).

Recognising the view that urban political ecology has been ‘curiously quiet on the very feature of the contemporary urban world that should make it so relevant: the dimensions of urbanization processes that exceed the confines of the traditional city’ (Angelo and Wachsmuth Citation2015, 16), we observe that business parks—amongst other city-edge spaces—have been overlooked by scholars and that the role of nature in city-edge business parks is under-researched. Furthermore, existing empirical studies of business parks rely heavily on survey-based and experimental methodologies, lacking inquiry into how employees interpret their contact with nature and failing to examine the wider ecological and social implications of this relationship. Qualitative enquiry is thus needed to explore the interrelationships between people and nature in these places which, outwardly characterised by intensive management, formal landscaping and high automobile use, often epitomise the ills of unsustainable development. Drawing on Tsing and others, we posit that the rich biodiversity in the cracks and interstices of the park enables rich, playful encounters that—resisting the order and temporality of business—are intriguingly subversive and can find voice through auto-photography. In doing so, we also recognise that in these powerful, yet often fleeting, encounters, (potential) fissures and ruptures are revealed in the capitalist ‘structure of domination’ (Holloway Citation2010, 35).

The following section reviews recent literature that draws our attention to the unruly edges of the city and shows the need for qualitative empirical work on everyday encounters with nature in business parks. This is followed by our visual ethnographic methodology and a thematic analysis of the data that was gathered by participants as part of everyday immersion at TVTE. In conclusion, we argue that employees’ entanglement with nature—and its expression through auto-photography—has radical potential to undo ‘business-as-usual’ in the park.

Noticing nature in the business park

Business parks have been theorised as non-places yet such a characterisation pays insufficient attention to their open-ended and unruly qualities. Existing literature on nature in business parks is overwhelmingly quantitative. It is focused on aspects such as stress-reduction rather than unpacking the value attached to human-non-human encounters. While nature is acknowledged as a key means of reinvigorating community and tackling climate crisis in edge city developments, there is a dearth of critical empirical work in this area. Given the lack of appetite among dominant actors for sustainable business park design, paying attention to narratives that resist or trouble the status quo is imperative. Our study thus trains attention on the meaning that users attach to their everyday entanglement with nature in this setting.

The unruly edges of ‘non-places’

City-edge business parks are commonly found in contemporary European cities, in the US and on the wider global stage (Phelps and Wood Citation2011; Mozingo Citation2011). In these formations, driven by low development costs and automobile-centric design, conservatism over marketability discourages developers from adopting sustainable designs (Bontje Citation2004). Distinguished by a large commuter surplus, low integration of functions, and dominance of private over public space (Hayden and Wark Citation2006), such places have been critically characterised as ‘abstract’ (Lefebvre Citation1991), ‘ageographical’ (Sorkin Citation1992), and ‘non-places’ (Augé Citation2008). In the literature on ‘non-place’, the relationship of the individual to place is contractual and objectified, threatening not just wellbeing but also social cohesion and ecological integrity (Dale and Burrell Citation2003; Farrar Citation2011).

However, the academic tendency to relegate the city edge to a ‘non-place’ has been critiqued for overlooking key practices and narratives that can help us grapple with ecological crisis. Drawing on wider scholarship from urban political ecology (e.g. Keil Citation2018; Ekers, Pierre, and Roger Citation2012), Tzaninis et al. (Citation2021, 242) argue that ‘seeing like a suburb’ is a neglected yet vital task: ‘considering how suburbanization has been targeted as an environmental catastrophe, it is not only poetic but imperative to become part of the solution and not the problem.’ For these authors, characterising the edge city as a ‘no-man’s land’ risks ‘steamrolling over generations of human-non-human societal relationships with nature’ (Tzaninis et al., Citation2021, 241). Rather, we are urged to study the city edge as a rich, more-than-human entanglement.

In such an entanglement, cautious framings of counter-hegemonic possibility find expression. For Tsing (Citation2015), ‘landscapes are radical tools for decentring human hubris’ (152) and we should take care to observe their ‘unruly edges’ (20). Here, nature is treated as a lively subject with an indeterminate capacity for resurgence that demands our attention. Thus, even ‘blasted’ landscapes where nature appears conquered or subdued are, simultaneously, ‘the edges of capitalist discipline’ (282). Tsing emphasises that interstitial ‘world-building’ processes provide ‘fugitive moments of entanglement’ (255), even in the midst of alienation. The latent, indeterminate quality of these ‘overlapping lifeways’ (258) cannot be controlled and tied neatly to a utopian vision of overcoming; indeed, Tsing argues against Hardt and Negri’s (Citation2000) idea that capitalism will be overcome by a singular solidarity, rejecting the notion of a unified force that emerges dialectically from capital’s ruins. However, unlike the flattening logic of ‘non-place’, Tsing’s work suggests that this entanglement may lead us back to ourselves.

This sensibility is echoed by Schmidt (Citation2017), who insists that wilderness is an immanent, uncontrollable element within suburbanization and industrialization that ‘holds the potential for (re)producing wilderness/social interrelationships’ (173) within the prevailing order. This immanent unruliness is evident in Valdivia’s (Citation2021) study of those who make a living in the toxic landscape of an Ecuadorian oil refinery, which foregrounds playful, everyday tactics of survival infused with ‘dignity, vitality, creativity, and ability’ (Valdivia Citation2021, 1831). Such scholarship does not deny the harm inflicted by capital’s toxic and alienating landscapes; rather, it highlights the ‘multiple lines of flight’ that are open to us, where possibilities antithetical to the dictates and logics of capital unfold.

Understanding the value of nature in business parks

Given the preceding discussion on the need to train our attention on the unruly suburban edge, there is a surprising lack of critical phenomenological research about nature in business parks. Research on nature and wellbeing has been heavily influenced by a quantitative tradition (e.g. Kaplan and Kaplan Citation1989) and studies of nature in the workplace or in business parks tend to reflect this. Following Kaplan’s (Citation1993) call for research on the role of nature in the workplace a number of studies have looked specifically at office life in relation to stress reduction and attention restoration. These studies (e.g. Lottrup et al. Citation2015; Largo-Wight et al. Citation2017) are almost overwhelmingly quantitative, relying on quasi-experimental or survey methodologies. A rare exception is Loder’s (Citation2014) qualitative study of office workers’ perceptions of green roofs in Chicago’s central business district. Given that the employment sites we inhabit are lived spaces, the dearth of qualitative work is surprising and interpretive understanding of the complex social reality of these places is urgently needed (Dale and Burrell Citation2003).

Within the literature on nature at employment sites, the distinct formation of the city-edge business park is notably under-researched. Kaplan’s (Citation2007) study of a peri-urban business corridor suggests that ugly parking areas and poor walkability negatively impact users’ wellbeing. Similarly, Gilchrist et al’s (Citation2015) study of science parks shows a positive correspondence between employee wellbeing and greenspace. However, the meanings that business park denizens attach to encounters with nature have received insufficient attention. In particular, ‘slow’ ethnographic enquiry is required to notice everyday experience in urban landscapes. Here, a ‘less androcentric materialism’ (Gandy Citation2022b, 35) focused on interstitial practices allows appreciation of the latent potential (Tsing Citation2015) of such encounters.

The biodiversity in business parks (Snep, Van Ierland, and Opdam Citation2009; Hogg and Nilon Citation2015) has been recognised as a rich resource that must be protected and leveraged for the common good. However, the social, economic, and ecological rewards this promises remain abstractly theorised or focus on the remit of urban designers. Connecting people with nature in the edge city has been posited as a key means for countering unmemorable spaces and regenerating civic life. As Paterson & Paterson and Connery (Citation1997, 345) observe, ‘a return to ‘designing with nature’ will in turn lead us back to community and place’. The human relationship with nature undergirds what Dunham-Jones & Dunham-Jones and Williamson (Citation2009, v) call ‘the big project for this century’—sustainably retrofitting the ills of sprawl and infusing ‘non-places’ with individual, social and ecological vitality. The importance of retrofitting measures was illuminated during the COVID-19 pandemic, when both the availability and the quality of green space came under sustained scrutiny (Ahmadpoor and Shahab Citation2021). This literature focuses on place attachment and legibility, seeing everyday connections with nature in the edge city as a means through which social isolation and political anaesthesia of non-place might be remedied, activating processes that are ‘unruly, uncertain, unfinished, collaborative, alive’ (Farrar Citation2011, 732).

Among dominant actors such as business park developers, however, there is often little appetite for sustainable design and existing policy in European countries does little to incentivise this. While measures that enhance greenspace are increasingly viewed as compatible with economic success and marketability in business parks, such measures are often stalled, lacking stakeholder ‘courage’ to opt for sustainable design (Bontje Citation2004, 44). We therefore focus attention on ‘bottom-up’ entanglements and their latent capacity to disrupt the status quo. Encounters with nature in the business park’s interstices unearth desires and possibilities that unsettle the seeming permanence of our current ways of doing business. Auto-photography can foreground nuanced perspectives that counter nature’s marginalisation, as we argue below.

Methodology

Recent qualitative work in the social sciences encourages dialogical modes of knowledge production. Encompassing such diverse approaches as PhotoVoice (Castleden, Garvin, and Nation Citation2008), participatory mapping (Pánek, Glass, and Marek Citation2020) and bricolage (Zebracki Citation2017), this work addresses the inequalities and power imbalances in researcher-researched relationships, empowering individuals and communities to design and carry out their own representational work. In another development, knowledge production has also become increasingly self-dialogical, with Paiva (Citation2020) identifying in creative activities such as poetry writing, opportunities to explore the ways in which ‘other beings perceive, experience, understand, appropriate, and alter spaces’ (6). Similarly, auto-photography—sometimes also referred to as self-directed photography and/or photovoice—offers penetrating examination of the activities through which ‘place meaning’ is constituted, revealing minor or hidden aspects of everyday existence and providing nuanced understandings of the meanings associated with apparently already ‘known’ or mundane spaces (Klingorová and Gökarıksel Citation2019). In an effort to challenge dominant visual framings of the edge city as a site of sublime desolation and industrial stagnation, auto-photography has been used to elicit richer, heterogeneous accounts of life at the city’s margins (Zebracki, Doucet, and De Brant Citation2019).

Our study resonates with recent scholarship which illuminates the political significance of using auto-photography to disrupt ‘accepted’ images of a site’s form and function, using visual methods to explore the multi-sensory and embodied knowledges by which life inside it is apprehended and understood (Whatmore and Hinchliffe Citation2003; Jiang and Kobylinska Citation2020; Rozena Citation2023). In this vein, Kelly’s work (Citation2001, 9) shows how auto-photography can rupture ‘accepted’ images of place, articulating ‘possibilities that extend beyond the immediate context’. We argue that photographs taken by everyday users who work in the business park, yet are not accustomed to having a say in its functioning, provide refreshing insight into the value attached to the park’s natural assets. In a city-edge formation where manicured landscaping and car parks dominate normative expectations of place, we show that such insight has the potential to render nature a more visible and active ‘participant’ in the site’s daily operations. Our work resonates with Rozena’s (Citation2023) claim that creative activity can create a rupture where this seems foreclosed. While not explicitly antagonistic, the photographs taken in the business park highlighted to powerful actors the need for sustainable design while unearthing desires and feelings that resist the norms of doing business.

The participant-led photography exercise

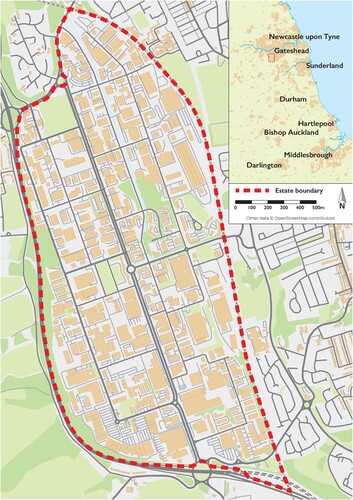

The project took place at Team Valley Trading Estate (TVTE), a 700-acre business parkFootnote4 on the outskirts of Gateshead, in north-east England. Its 700 firms employ around 20,000 people in a variety of occupations, from light manufacturing to retail. Created in the 1930s to counter regional unemployment, TVTE is historically significant. Its original design by the architect and planner William (later Baron) Holford—which was said to be inspired by Welwyn Garden City—was undergirded by a strong association between nature, beauty and employee wellbeing (O’Donnell and Petts Citation2019). While TVTE never fully lived up to its billing as ‘part Garden City and New Town minus the housing’ (Hetherington Citation2011, 530), the site still boasts walkable woodland at its marginsFootnote5, mature trees, unusually wide grass verges and intermittent green spaces that are used by dog-walkers and joggers as well as employees and shoppers. Indeed, TVTE’s natural and man-made assets display many of the disorderly yet highly textured attributes identified by Sennett (Citation1970) as antithetical to the ordering impulses of contemporary planners. This mix of ‘wild’ and man-made was baked into the park’s original design in the 1930s. While the integrity of Holford’s vision has been fragmented and somewhat buried over time, the business park’s natural assets are today sufficiently intact to permit intriguing encounters to those who work there (see ).

With the endorsement and support of a gatekeeper at UK Land Estates, the company that owns and operates TVTE, we recruited 18 participants who were employed across a range of businesses at TVTE via hand-delivered flyer distribution and visits to on-site employers, including kitchen showrooms, law offices and mobile food trucks.Footnote6 In this way, we sought to expand our sample beyond so-called ‘nature enthusiasts’ (Birch, Rishbeth, and Payne Citation2020). Due to funder requirements, participants were recruited in a consecutive manner over a six-month period (June-November). This timeframe encompassed instances of both extreme heat and high precipitation, which contributed to a background variability (material and affective/atmospheric) that was evident in the images received. It was also book-ended by ongoing ethnographic research comprising (participant) observation, interviews and ‘small talk’ (Harvey, Hawkins, and Thomas Citation2012). In the three years our overall project unfolded across, our approach took on many of the characteristics of ‘ecological ethnography’ (Gandy Citation2022a), including a heightened alertness to our own embodied experiences in, and memories of, the sites under investigation. This, in turn, prompted recognition of our own status as vicarious ‘indwellers’ (Zebracki, Doucet, and De Brant Citation2019, 494).

Each participant in the photography exercise was given a 40-exposure disposable camera and invited to provide photographic responses to the deliberately open-ended question, ‘What does nature mean to you at Team Valley?’; a question reflecting our conviction, following Susan Sontag, that ‘[t]o take a picture is to have an interest in things as they are … to be in complicity with whatever makes a subject interesting, worth photographing’ (Citation1977, 12). As part of their everyday routine at TVTE, respondents took photographs which expressed their understanding of nature and its processes.

The processed film was returned to respondents, who selected a small number of their own photos and commented on these; this selection was checked by the TVTE gatekeeper and uploaded to the project website. Participants generated a total of 322 photographs, from which they personally chose 70 images for additional discussion and inclusion in the exhibition that concluded the project in July 2019. All ten images that are featured in this article were also included in the exhibition. Participants were assured of anonymity from the outset and real names were not attached to the images.

Disposable cameras were intentionally used to encourage participants to stay in the present (rather than editing and curating) during their everyday engagement with the site. The low-tech medium of disposable cameras, ironically, provided an opportunity to showcase the provocative dynamism of encounters with nature. As Hunt (Citation2014, 158) argues, ‘[w]orking with low-tech devices grants photography a new materiality; greater agency is afforded to light, chemicals and chance’. The value of using these tools is also supported by Meenar and Mandarano’s (Citation2021, 2) contention that ‘high-touch engagement tools’, defined as ‘low-tech but highly interactive tools and methods’, can be useful in engaging disinvested actors.

The resulting photographs and comments were coded in an open-ended fashion, using techniques drawn from grounded theory to arrive at emergent themes. Our approach was inspired by Shortt and Warren's (Citation2019) Grounded Visual Pattern Analysis (GVPA), involving ‘dialogic’ and ‘archaeological’ elements. We therefore aimed to capture the conscious knowledges communicable via testimony and the unconscious knowledges manifesting in the photographed scene. Here, we were interested in what participants themselves referred to as ‘nature’Footnote7 at TVTE and how use of this term allowed them to frame and express particular narratives about lived experience in the business park.

We acknowledge that the photographs from the study represent mere moments in the unfolding life of the park, and that during other moments, such as nighttime, a time less accessible to auto-photography (and other social scientific methods), the park’s wooded areas and footpaths could precipitate feelings of fear and anxiety, profoundly altering the experiences such places elicit (Bondi and Rose Citation2003). However, our explicit focus is on the hours when participants found themselves at TVTE, which tended to be during daytime hours.

The themes that emerged from the photographic engagement, which we reflected upon in relation to our own long histories of visiting and using TVTE, reveal much about participants’ relationships with the park’s green spaces, as presented in the findings below.

Encounters with nature at TVTE: flow, co-existence, rebellion and possibility

Showing the interplay of movement, light and depth of field, photographs that participants selected illustrated the overflowing sensory stimulation that they derived from their encounters with nature. Narrating their images, the photographers commented on the surprisingly rich biodiversity at TVTE, noting the harmonious co-existence of industrial and natural elements. However, participants were also intrigued by nature’s rebellious and anarchic tendencies, especially its alternate rhythms, its capacity to resist the human impulse to manage and control, and its commentary on human striving, longing and impermanence. While wanting to make colleagues aware of the park’s biodiversity, participants simultaneously enjoyed the otherness of being in TVTE’s ‘undiscovered’ interstices.

Our findings are organised into three themes, each one a distillation of comments elicited through the autophotography exercise, participant-led selection of images (and accompanying quotes), the exhibition of photographs to which it gave rise, and the larger ethnographic programme of which these elements formed part. These themes are: Moving and overflowing, which captures the unboundedness and dynamism of participants’ experiences of nature in the park. Co-existing harmoniously, which summarises experiences of natural and industrial elements flourishing alongside each other. Rebelling and reclaiming, by contrast, highlights participants’ fascination with the undoing of man-made structures and landscapes as explored below.

Moving and overflowing

When reviewing and narrating the images they had captured, participants often selected photographs that were relatively unfocused and under-or over-exposed. This tells us much about the sensory experience of movement through the park’s green spaces. Captured by Jean, a catering manager whose premises abut a large parcel of grassland at the TVTE’s heart, , with its diffuse sunlight, throng of seagulls and low-rise industrial buildings (with thumb), provided a compelling insight into the flux and dynamism of the park’s verges during a morning commute. Such ‘little epiphanies’, as Tonkiss (Citation2000, 278) argues, foster an awareness of the extraordinary lurking among the mundane. The photograph thus brings to mind Latham and McCormack’s (Citation2009) observation that images are always more than ‘just a representational snapshot’; they are ‘resonant blocks of space–time: they have duration, even if they appear still’ (253). Indeed, such everyday photographs are ‘better understood as [conveying] a sense of involvement in the processuality of the urban’ (Latham and McCormack Citation2009, 254).

Figure 2: Diffuse sunlight, throng of seagulls and low-rise industrial buildings during a morning commute. Photographer: Jean, catering manager.

Participants emphasised that, even when inside offices or buildings, the park’s natural assets offered an inexhaustible repertoire of light, shapes, and colours that—reaching from the workspace into a relatively unbounded realm—called powerfully to them. Company director Ben (see ) offered the view from his desk as his ‘most regular view of the Valley,’ explaining how this view, which reaches through a foreground of formal park vegetation to the wooded valley beyond, sustains him during long stints of work, while also beckoning to him and drawing him outdoors.

Figure 3: Office window view through the formal park vegetation in the foreground to the wooded valley beyond. Photographer: Ben, company director.

While participants represented themselves at different degrees of separation from or intertwinement with what they described as ‘nature’, those who walked their dogs at TVTE had particularly intimate, playful encounters, affording novel and overflowing ideas about the business park. Alan, a participant who works at TVTE and walks his dog on its grounds, illustrated the experience of exploring the park's nooks and crannies with—and through the experiences of—his dog, Patch, who made him pause to enjoy the sensory feast of piled-up leaves. Office worker Lisa, who also walks her dog at TVTE, described how her dog regularly leads her to a grand weeping willow, which becomes a full-bodied experience enacted through crouching and crawling under the enveloping canopy (see ). ‘Our dog always deposits her ball at the base of the trunk’, she explained, ‘and we have to go in and retrieve it’. ‘It’s lovely’, she continued, ‘to feel shielded by the branches and leaves’. Lisa speaks to what anthropologists (for example, Oliver Citation1978) identify as a deep human need for shelter: from the elements, from people, and even from our own thoughts. Hers is also a much more favourable rendition of solitariness and introspection than has been found in recent scholarly depictions of non-place, in which concerns for social atomisation are particularly prominent (for example, Rosler Citation1998).

Figure 4: Led by the dog under the canopy of a grand weeping willow tree. Photographer: Lisa, office worker.

Exposing the limited engagement of urban political ecologists with non-human denizens of urban space (Gandy Citation2022b), relationships with wild animals also featured prominently in the study, illustrating the lively more-than-human ways in which TVTE was experienced. For example, Emma, who works in a salesroom described how she, and several colleagues, had found delight in the movements of a stoat outside the showroom window: ‘When we first saw our little creature it was a very quiet day, we all watched as she went back and forth with fieldmice which must have been caught to feed babies.’ She described (in knowingly anthropomorphising termsFootnote8) how her co-workers were transported into the unfolding drama of the stoat family’s daily life, which provided welcome distraction from their work routine: ‘As we work on the Team Valley, we don’t expect to be so close to nature but when we see this little creature … .it brightens our day and we all look for [her] coming and going’.

In keeping with our interest in the subversive quality of encounters with nature in the business park, the photos and accompanying narratives had a dynamic, overflowing quality that resisted reified ideas of what kinds of activity, and what temporalities prevail in this ‘business-like’ zone of the city. While some photographs celebrated the status quo of business development in the park, this unbounded sensibility permitted narratives of tension and resistance to find expression as detailed below.

Co-existing harmoniously

While curating their photographs, respondents were keen to emphasise the surprising diversity and richness of nature present in a man-made environment. For some, this was an unproblematic alignment yet, as we explore later, many photos revealed a less comfortable sensibility. During our discussions with participants about their curated photos, comments such as ‘[y]ou wouldn't believe this is a business park’ were typical, celebrating TVTE’s alignment of nature and commerce. Such responses, and the photos that they accompanied, reflected a feeling that TVTE showcases fine natural assets while meeting business and wellbeing needs. Several of our respondents indicated that their appreciation of nature at TVTE was heightened by the presence of man-made elements. The attractiveness of plants, for example, was felt to be amplified by their proximity to, and visual relationship with formal elements, such as the metal railings captured by office worker Amanda (see ). Alongside the berries pushing through them, she explains, these railings epitomize ‘what working in the valley is all about: industrial with natural beauty’.

Appreciating the juxtaposition of flora and fauna in the park, some participants expressed feelings that were in keeping with the park’s original 1930s design, where Holford sought to retain beauty and nurture employee wellbeing by intertwining industry and nature. However, as explored in the following section, this sensibility contrasted sharply with the more unsettled narratives emerging from other participants’ photos.

Rebelling and reclaiming

Beyond harmonious co-existence, some participants pointed to a more complicated (and sometimes troubled) relationship between nature and industry in the park, savouring moments where the power of nature appeared to stymie or frustrate man’s instrumental goals. Images of weeds, for example—in the cracks between paving stones, at the edges of pavements, and resting atop patches of asphalt—elicited comments about nature finding a way to survive or break through man-made barriers. Collectively, these images visualise an environment fighting against the ‘excessive rationalisation of nature under modernity’ (Gandy Citation2022a, 1124).

Indeed, with remarkable clarity, they depict a nature that ‘injects its own materiality and dynamism into … . ‘socio-ecological processes’’ (Cloke and Jones Citation2002, 30). Capturing scrub that was growing in a temporarily vacant lot (see ), office worker Allie observed that although, in the logic of the business park, such land use was deemed as ‘waste’, it was in fact ‘a good habitat for wildlife, bees and butterflies.’ In Allie’s photo the office and warehouse buildings in the rear are obscured by rising strands of weldFootnote9 that stand out triumphantly against the blue sky.

A similar theme of resisting human efforts to impose order on the space was reflected in our respondents’ penchant for photographing elements of ‘unintentional’ flora and fauna that ruptured the park’s manicured, man-made aesthetic. Office worker Allie’s attention was arrested by a group of ‘[common ink cap] mushrooms pushing through, surviving the mulch, living on’ (see ). Another respondent photographed a lone common cat’s ear amid a manicured, uniform lawn. With its leaves formed in a low-growing, basal rosette, the common cat’s ear operates ‘under the radar’ of the estate’s mowers; a striking illustration of nature’s continued (if diminishing) ability to withstand the sharp edges of 'business-as-usual’. Indeed, these respondents were intrigued by the ways that such ungovernable elements resisted the ordering impulses of the park’s landscape gardeners, imposing their own structures and rules.

These images capture nature’s tendency toward indiscipline, and its capacity to supersede the efforts of those seeking to harness it towards human productivity (and profit). Our respondents’ photographs draw attention to the disorderly and sometimes tense convergence of public and private assets, and the in-between spaces opening up between them. With traces of human presence all about, many such spaces showed signs of long-term appropriation by unknown human elements, further complicating their ownership status and contributing to a teasing undercurrent of subversion. Land use was questioned, pointing to the value of this resource when not built on. The mushrooms and weeds were framed by participants as humble opportunists, clinging onto a fragile existence that might be curtailed by the business park’s primary mandate. Yet, these forces that signified something other than business-as-usual were also conceived as powerful in their ability to pop up or reappear in spite of the huge human effort expended on controlling and suppressing them.

Participants were also intrigued by human efforts to steward the park’s natural assets on the site, capturing ways in which humans were assisting plants, birds and animals in their efforts to thrive in the space. Libby, an office administrator, captured some of the many bird feeders that are found within the park (see ), enjoying the ambiguity around which park users might have placed them there. Libby’s photo shows the hardy, berry-laden hawthorn providing a ready food source for local birds yet supplemented by the efforts of humans seeking (albeit superfluously at this time of year) to protect or increase bird life on the site.

Figure 8: Bird feeders that are found within the business park. Photographer: Libby, office administrator.

Suppression or concealment of nature also emerged as a critical vein in the photographs. Some respondents commented that the park’s natural features were relatively under-appreciated and expressed frustration at the lack of awareness of this rich resource. For example, Helen, a company director who photographed TVTE’s culverted waterway: ‘took this picture (see ) to remind everyone who works here that we even have a river’. Her photo represents an appeal to recognise that which has been buried or goes unnoticed, whether by the shoppers who pass through (typically by car) or by those who work at TVTE, for whom the park’s natural environment is an unscrutinised backdrop to more pressing human matters. That the picture reveals only a semblance of ‘unmanaged’ natural vegetation—in the form of a dense stand of greater willow-herb and a line of semi-mature willow trees—does not detract from the photographer’s clear insinuation of ‘authentic’ naturalness.

Furthermore, while respondents expressed a desire to promote the park’s natural assets, this was sometimes in conflict with a desire to retain it for themselves. Several of our respondents, for example, characterised TVTE’s spaces and places as ‘hidden gems’ or oases whose value was heightened because they were relatively undiscovered and made possible a performance of what the park might be if not harnessed to the demands of doing business. While company director Helen wanted to remind her colleagues of nature’s presence at TVTE, she also noted how the seclusion of the clearing featured in —with its regenerating crack willow tree—made it ‘a beautiful spot’ for reverie and intentional apartness from the park’s car-dominated rhythms.

Finally, TVTE’s mature trees provided participants with a pointed contrast to the daily commercial activity of the park and countered the aesthetics of ‘non-place’ suggested by its utilitarian newer buildings and highways. Judging by the frequency with which they appeared in our respondents’ images, mature trees—often associated with a pristine nature of the ‘first kind’ (Kowarik Citation2023)—are a central and enduring feature of respondents’ experiences of nature at TVTE. For respondents like Lisa, veteran trees act as landmarks around which a sense of place and belonging may develop, while her strong feelings of attachment to her ‘favourite tree’ at TVTE contrasted with her relative lack of feeling for the estate’s buildings, many of which are set within a functional nature of the ‘third kind’ (Kowarik Citation2023).

Mature trees were also beheld as a canvas reflecting the changing seasons and as a mirror to human striving, in which seemingly solid achievements can be swept away by wider processes of decomposition. This was expressed profoundly by Jin, a catering manager whose premises stand parallel to a dense stand of birch trees. Jin narrated his photo, which shows fallen trees amidst those that remain standing, as an amusing, humbling commentary on his own efforts to gain a foothold as a business in the park. For Jin, the fate of the trees also promoted meditation on how nature’s cycle eventually absorbs even that which seems permanent, providing opportunity for regrowth and renewal (see ).

In keeping with Farrar’s (Citation2011) notion of place attachment and politics, these encounters with the park’s fungi and trees helped lively and unruly feelings find expression. Photographing ‘oases’ of nature that they had located within TVTE, denizens were able to inhabit feelings and desires that were the antithesis of the park’s primary raison d’être. Through participatory photography of natural assets, the order and temporality of the business park were opened to contestation, giving agency to marginalised voices, even while the agency of such actors remained tightly circumscribed by the site’s ownership and governance structure. As we explore in the following section, the insubordinate spirit of nature that has been the focus of this study gives reason for hope.

Fresh narratives from the city edge

Everyday life in suburbia is under-researched and, in order to find ways out of urban crisis, we need to capture the lived reality of those who inhabit the city’s unruly edges. Considering the business park as a prevalent but neglected spatial formation, we have explored employees’ lively, open-ended encounters with nature, upholding that such entanglements are capable of troubling capital’s hubris (Tsing Citation2015). Using auto-photography to help these narratives find expression and open up discussion with dominant actors, the study resonates with scholarship that celebrates the subversive potential of arts-based social science research (Rozena Citation2023).

The participants’ photos highlight the significance of everyday interaction with nature, including the expanded agency offered by human-animal encounters, the feeling of tranquillity generated by green spaces, and the grounding sense of freedom that derives from bodily movement in a natural setting, providing needed reminders that ‘life is not that tidy’ (Mabey Citation2012, 291). Here, green encounters in close proximity to commercial hustle and bustle suggested the value attached to ‘edge conditions’ as a source of fresh insight.

In the business park, nature-based auto-photography is an effective way to harness and nurture sentiments that run counter to the dominant aesthetic of these extractive, car-dominated spaces. Employees of the multifarious retail units, offices and food trucks that are located in the business park have little to no say in its governance and development; therefore rebellious sentiments are of course constrained by prevailing power structures. Yet, in keeping with Farrar’s (Citation2011) contention that place attachment is a precursor of critical civic action, employee encounters with the business park’s fungi and opportunistic weeds make this place legible in ways that encourage unruly denizens. These ‘overlapping lifeways’ (Tsing Citation2015, 258) are intractable and do not map neatly onto counter-hegemonic struggle but they create lively, dignified subjects (Valdivia Citation2021) whose capacity for undoing business-as-usual is not foreclosed.

Based on qualitative enquiry, our findings show that, while the park’s biodiversity is interstitial and easily overlooked, TVTE is a heterogeneous lived space in which connection to nature is deeply valued. The photographs taken as part of this study show, on the one hand, the business park’s ‘man-made’ and ‘wild’ elements in harmonious juxtaposition, capturing a cohesive alignment of natural and industrial aims. Yet the images and their surrounding narratives also indicate a fascination with nature’s ability to resist the park’s dominant value system, questioning land use, fostering broader stewardship and celebrating the potential unravelling of the existing order.

Here, rupture, decay and takeover were enthusiastically noticed and appreciated. For some, these moments of ‘botanic anarchy’ (Helphand Citation2006, 11), pointed to an indeterminacy that ‘makes life possible’ (Tsing Citation2015, 20) and gave rise to a questioning of the established order that the business of the park rests on. In this flux, mature trees offered opportunities for attachment and philosophical reflection that put in perspective the daily human strivings in the business park, promoting reflection on the need for stability and continuity amidst neoliberal precarity (Macnaghten Citation2004).

We do not suggest that an organised political movement arose from everyday encounters with the business park’s fungi and small mammals. Whereas some studies (e.g. Schmidt Citation2017) capture activism emerging immanently when an ecological asset is compromised, no such momentum was observed at TVTE. Rather, we observed participants aligning themselves, through their everyday natural encounters, to other ‘world-making projects’ (Tsing Citation2015, 21–22) that offer indeterminate endings. In keeping with Valdivia’s (Citation2021, 1847) framing of environmental justice we find, in the interstices of the park, lively subjects who are operating from a ‘place of vitality’ and possibility.

Resonating with Rozena’s (Citation2023) work, auto-photography allowed these intractable subjects a means of self-expression that nurtured self-understanding and made their ideas visible to powerful actors. In keeping with Kelly’s (Citation2021) study of the use of participant-generated photographs to disrupt ‘accepted’ images, this method played a political role in our study of business park, raising the profile of TVTE’s natural features. The process of negotiating access and recruiting participants as well as exhibiting these unusual photographs at one of TVTE’s busy hubs, created an opportunity for conversation with the park’s developers about the importance that employees attach to the park’s plants and animals. In a context of ecological crisis where solutions must be found in the ruins themselves (Tsing Citation2015; Tzaninis et al. Citation2021), we situate biodiversity in the business park as the very stuff through which critical consciousness is forged and show the value of creative processes that give voice to those who treasure the park’s weeds, trees and improbable mushrooms.

Acknowledgements

The activities forming part of this project were underpinned by funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and Global Urban Research Unit (GURU), Newcastle University. We extend a heartfelt thanks to Rob Ayre of UK Land Estates, the participants from TVTE, and the reviewers and editorial team for their particularly helpful and supportive comments. We are grateful to Geoff Vigar, Daniel Mallo and Armelle Tardiveau who helped develop our understanding of scholarship surrounding business parks.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data Availability Statement

A limited data set comprising the curated photos and selected comments is available at https://research.northumbria.ac.uk/tvtenature/. Due to ethical considerations, further supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Abigail Schoneboom

Dr Abigail Schoneboom, Lecturer in Urban Planning at Newcastle University, is an award-winning ethnographer whose research focuses on the future of work in cities. Email: [email protected]

Oliver Moss

Dr Oliver Moss is a Research Fellow and Head of Research and Impact at Teesside University whose research explores the embodied, emotional, and affective nature of everyday life. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 ‘Business park’ denotes a complex with some combination of office, light industrial, warehouse, and retail facilities, where the land and buildings are often managed by a single entity. Land that is not built-up is often landscaped but original vegetation may also be left intact (Hogg and Nilon Citation2015).

2 In the UK, from where we write, suburban business parks – of the kind we deal with in this paper – account for 0.5% of all land and 4.4% of total businesses (Rodrigues, Vera, and Swinney Citation2022).

3 Despite ongoing debate regarding the relative merits of “edge” and “suburb” as analytical concepts (e.g. Phelps & Phelps and Wood Citation2011), we have chosen to use both terms here in order to comprehensively address different aspects of this large and heterogeneous site.

4 UK trading estates such as TVTE have a distinctive history associated with light manufacturing. However, TVTE’s multifarious uses today span retail, office, manufacturing and service functions, making the term ‘business park’ (used rather than ‘trading estate’ throughout this article) an apt descriptor.

5 There is a small pocket of ancient woodland located at the western edge of TVTE. Here, redwing blackbirds and mistle thrush find habitat among its dense canopy of ash, birch, sycamore and willow, all within close proximity of nearby industrial and commercial operations (Allen Citation2024).

6 Informed consent was received from participants via hand-delivered form/information sheet. The project was approved by the Teesside University Arts, Design & Social Sciences ethics committee, reference 10822.

7 Our intention with this article is not to overlook recent academic debate regarding our entanglement with more-than-human others (e.g. Puig de la Bellacasa Citation2019); we aim simply to understand the sense-making processes of TVTE’s human actors.

8 We recognise that, at times, the commentary of our respondents strays into the vague and sentimental, and that the whimsical characterisation of certain scenes and events hints at an othering of flora and fauna that may be problematic. At the same time, and in an era when hope is essential to envisioning a more elevated and virtuous relationship with nature, we take encouragement from the suggestion that a certain anthropomorphic romanticism can also enhance human connectedness to nature (Tam, Lee, and Chao Citation2013).

9 Mindful of concerns regarding the Linnaean taxonomic system (see, for example, Ereshefsky Citation2000), especially its ability to adequately classify life (and particularly more-than-animal life), we use everyday vernacular names throughout. While doing so, we acknowledge that any attempt to ‘name’ something involves distinguishing it from the other things with which it is contingently produced.

References

- Ahmadpoor, N., and S. Shahab. 2021. “Urban Form: Realising the Value of Green Space: A Planners’ Perspective on the COVID-19 Pandemic. ” Town Planning Review 92 (1): 49–55. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2020.37.

- Allen, M. 2024. “The Weight of Ants in the World .” holt Journal for Artistic Research 2: 124–139.

- Angelo, H., and D. Wachsmuth. 2015. “Urbanizing Urban Political Ecology: A Critique of Methodological Cityism .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39: 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12105

- Augé, M. 2008. Non-places. London: Verso .

- Birch, J., Rishbeth, C., and Payne, S. R. 2020. “Nature Doesn’t Judge you – how Urban Nature Supports Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing in a Diverse UK City .” Health & Place, 62, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102296

- Bondi, L., and D. Rose. 2003. “Constructing Gender, Constructing the Urban: A Review of Anglo-American Feminist Urban Geography .” Gender, Place & Culture 10: 229–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369032000114000.

- Bontje, M. 2004. “From Suburbia to Post-Suburbia in the Netherlands: Potentials and Threats for Sustainable Regional Development .” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 19: 25–47. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOHO.0000017705.30156.32.

- Castleden, H., Garvin, T., and Nation, H.-A.-A. F. 2008. “Modifying Photovoice for Community-Based Participatory Indigenous Research .” Social Science & Medicine, 66, 1393-1405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.030.

- Cloke, P., and Jones, O. 2002. Trees Cultures: The Place of Trees and Trees in Their Place. London: Routledge .

- Dale, K., and G. Burrell. 2003. An-aesthetics and Architecture. Basingstoke: Palgrave .

- Dunham-Jones, E., and Williamson, J. 2009. Retrofitting Suburbia: Urban Design Solutions for Redesigning Suburbs. New York, NY: Wiley .

- Ekers, M., H. Pierre, and K. Roger. 2012. “Governing Suburbia: Modalities and Mechanisms of Suburban Governance .” Regional Studies 46 (3): 405–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.658036

- Ereshefsky, M. 2000. The Poverty of the Linnaean Hierarchy: A Philosophical Study of Biological Taxonomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

- Farrar, M. E. 2011. “Amnesia, Nostalgia, and the Politics of Place Memory .” Political Research Quarterly 64: 723–735. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912910373553.

- Gandy, M. 2022a. “Ghosts and Monsters: Reconstructing Nature on the Site of the Berlin Wall .” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 47: 1120–1136. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12562

- Gandy, M. 2022b. “Urban Political Ecology: A Critical Reconfiguration .” Progress in Human Geography 46 (1): 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325211040553

- Gilchrist, K., C. Brown, and A. Montarzino. 2015. “Workplace Settings and Wellbeing: Greenspace use and Views Contribute to Employee Wellbeing at Peri-Urban Business Sites .” Landscape and Urban Planning 138: 32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.02.004.

- Hardt, M. and Negri, A. 2000 Empire. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press .

- Harvey, D. C., H. Hawkins, and N. J. Thomas. 2012. “Thinking Creative Clusters Beyond the City: People, Places and Networks .” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 43: 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.11.010

- Hayden, D., and Wark, J. 2006. A Field Guide to Sprawl. London: W. W. Norton .

- Helphand, K. 2006. Defiant Gardens: Making Gardens in Wartime. San Antonio: Trinity University Press .

- Hetherington, P. 2011. “Team Valley and the Benefits of Pump-Priming .” Town and Country Planning 80 (12): 530–533.

- Hogg, J. R., and C. H. Nilon. 2015. “Habitat Associations of Birds of Prey in Urban Business Parks .” Urban Ecosystems 18: 267–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-014-0394-8.

- Holloway, J. 2010. Crack Capitalism. London: Pluto Press .

- Hunt, M. A. 2014. “Urban Photography/Cultural Geography: Spaces, Objects, Events .” Geography Compass 8: 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12120.

- Jiang, Z., and Kobylinska, T. 2020. “Art with Marginalised Communities ” City 24 (1-2): 348–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2020.1739460

- Kaplan, R. 1993. “The Role of Nature in the Context of the Workplace .” Landscape and Urban Planning 26 (1-4): 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-2046(93)90016-7

- Kaplan, R. 2007. “Employees’ Reactions to Nearby Nature at Their Workplace: The Wild and the Tame .” Landscape and Urban Planning 82: 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.01.012.

- Kaplan, R., and S. Kaplan. 1989. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

- Keil, R. 2018. “After Suburbia: Lineaments of a Strategy for Research and Action in the Suburban Century .” In AAG 2018, Urban Geography Plenary, New Orleans, USA, 10–14 April 2018.

- Kelly, D. 2021. “Beyond the Frame, Beyond Critique: Reframing Place Through More-Than Visual Participant-Photography. ” Area 53: 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12611.

- Klingorová, K., and B. Gökarıksel. 2019. “Auto-Photographic Study of Everyday Emotional Geographies .” Area 51: 752–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12537.

- Kowarik, I. 2023. “Urban Biodiversity, Ecosystems and the City. Insights from 50 Years of the Berlin School of Urban Ecology .” Landscape and Urban Planning 240: 104877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104877

- Largo-Wight, E., P. S. Wlyudka, J. W. Merten, and E. A. Cuvelier. 2017. “Effectiveness and Feasibility of a 10-Minute Employee Stress Intervention: Outdoor Booster Break .” Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health 32: 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240.2017.1335211.

- Latham, A. and McCormack, D. 2009. “Thinking with Images in non-Representational Cities: Vignettes from Berlin .” Area 41 (3): 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2008.00868.x

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell .

- Loder, A. 2014. “‘There's a Meadow Outside my Workplace’: A Phenomenological Exploration of Aesthetics and Green Roofs in Chicago and Toronto. ” Landscape and Urban Planning 126: 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.01.008.

- Lottrup, L., U. K. Stigsdotter, H. Meilby, and A. G. Claudi. 2015. “The Workplace Window View: A Determinant of Office Workers’ Work Ability and Job Satisfaction .” Landscape Research 40: 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2013.829806.

- Mabey, R. 2012. Weeds: The Story of Outlaw Plants. London: Profile Books .

- Macnaghten, P. 2004. “Trees.” In Patterned Ground: Entanglements of Nature and Culture, edited by S. Harrison, S. Pile, and N. Thrift, 232–234. Reaktion Books .

- Martin, D. 2008. “The Post-City Being Prepared on the Site of the ex-City. ” City 12 (3): 372–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810802479001

- Meenar, M. R., and L. A. Mandarano. 2021. “Using Photovoice and Emotional Maps to Understand Transitional Urban Neighborhoods .” Cities 118: 103353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103353.

- Mozingo, L. A. 2011. Pastoral Capitalism: A History of Suburban Corporate Landscapes. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press .

- O’Donnell, R., and D. Petts. 2019. “‘Rural’ Rhetoric in 1930s Unemployment Relief Schemes .” Rural History 30: 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956793319000049.

- Oliver, P. 1978. Shelter and Society: New Studies in Vernacular Architecture. London: Barrie & Jenkins .

- Paiva, D. 2020. “Poetry as a Resonant Method for Multi-Sensory Research .” Emotion, Space and Society 34: 100655–100657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2020.100655

- Pánek, J., M. R. Glass, and L. Marek. 2020. “Evaluating a Gentrifying Neighborhood’s Changing Sense of Place Using Participatory Mapping .” Cities 102, Article 102723.

- Paterson, D. D., and K. Connery. 1997. “Reconfiguring the Edge City: The Use of Ecological Design Parameters in Defining the Form of Community .” Landscape and Urban Planning 36: 327–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(96)00363-5.

- Phelps, N. A., and A. M. Wood. 2011. “The New Post-Suburban Politics? ” Urban Studies 48: 2591–2610. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098011411944.

- Pink, S. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. Los Angeles: Sage .

- Puig de la Bellacasa, M. 2019. “Re-animating Soils: Transforming Human–Soil Affections Through Science, Culture and Community .” The Sociological Review 67 (2): 391–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026119830601

- Relph, E. 1976. Placelessness. London: Pion .

- Rodrigues, G., O. Vera, and P. Swinney. 2022. At the Frontier: The Geography of the UK’s New Economy. London: Centre for Cities .

- Rosler, M. 1998. In the Place of the Public: Observations of a Frequent Flyer. Cantz: Verlag .

- Rozena, S. 2023. “Communal Interaction and Creativity as Revolution: Resistance to Corporate Landlords by Regulated Tenants .” City 27 (1-2): 76–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2023.2180826.

- Schmidt, D. H. 2017. “Suburban Wilderness in the Houston Metropolitan Landscape .” Journal of Political Ecology 24 (1): 167–185. https://doi.org/10.2458/v24i1.20793

- Sennett, R. 1970. The Uses of Disorder: Personal Identity and City Life. New York: Knopf .

- Shortt, H. L., and S. K. Warren. 2019. “Grounded Visual Pattern Analysis: Photographs in Organizational Field Studies .” Organizational Research Methods 22: 539–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428117742495.

- Sinclair, I. 2003. London Orbital: A Walk Around the M25. London: Penguin .

- Snep, R., E. Van Ierland, and P. Opdam. 2009. “Enhancing Biodiversity at Business Sites: What are the Options, and Which of These do Stakeholders Prefer? ” Landscape and Urban Planning 91: 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2008.11.007.

- Sontag, S. 1977. On Photography. London: Penguin .

- Sorkin, M. 1992. “Introduction: Variations on a Theme Park.” In Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space, edited by M. Sorkin, xi–xv. New York: The Noonday Press .

- Tam, K.-P., S.-L. Lee, and M. M. Chao. 2013. “Saving Mr. Nature: Anthropomorphism Enhances Connectedness to and Protectiveness Toward Nature .” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 49 (3): 514–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2013.02.001

- Tonkiss, F. 2000. “'A-Z.” In City A-Z, edited by S. Pile, and N. Thrift, 1–3. London: Routledge .

- Tsing, A. L. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World : On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press .

- Tzaninis, Y., T. Mandler, M. Kaika, and R. Keil. 2021. “Moving Urban Political Ecology Beyond the ‘Urbanization of Nature’.” Progress in Human Geography 45 (2): 229–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520903350

- Valdivia, G. 2021. “Jugarse La Vida: Urban Political Ecologies of Oil and Marronage .” Antipode 53 (6): 1829–1852. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12743

- Whatmore, S., and S. Hinchliffe. 2003. “Living Cities: Making Space for Urban Nature .” Soundings: A Journal of Politics and Culture 22: 137–150.

- Zebracki, M. 2017. “Queer Bricolage .” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 16: 605–606.

- Zebracki, M., B. Doucet, and T. De Brant. 2019. “Beyond Picturesque Decay: Detroit and the Photographic Sites of Confrontation Between Media and Residents .” Space and Culture 22 (4): 489–508. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331217753344.