ABSTRACT

Objective: To avoid restraints and involuntary care caregivers should be aware if and how a patient resists care. This article focuses on behavioural expressions of people with severe dementia in nursing homes that are interpreted by their formal and informal caregivers as possible expressions of their experience of involuntary care.

Method: Concept mapping was used, following five steps: (1) brainstorming, (2) rating, (3) sorting, (4) statistical analysis & visual representation and (5) interpretation. Specialists (n = 12), nurses (n = 23) and relatives (n = 13) participated in separate groups .

Results: The views generated are grouped into clusters of behaviour, presented in graphic charts for each of the respondent groups. The large variety of behavioural symptoms includes, in all groups, not only the more obvious and direct behavioural expressions like aggression, resistance and agitation, but also more subtle behaviour such as sorrow, general discomfort or discontent.

Conclusion(s): In the interpretation of behavioural symptoms of people with severe dementia it is important to take into account the possibility of that person experiencing involuntary care. Increased awareness and understanding of the meaning and consequences of the behavioural expressions is an important step in improving dementia care by avoiding restraints and involuntary care to its maximum.

Introduction

In caring for people with severe dementia in nursing homes it was until recently not uncommon to use restraints (Hamers & Huizing, Citation2005), such as physical restraints (vests, belts, wheelchair bars and brakes, chairs that tip backwards, bedside rails), chemical restraints (i.e. sedatives, antipsychotics) or other restraining methods (force or pressure in medical examination, treatment or activities of daily living). However, such approaches are increasingly being challenged both from their scientific evidence and from an ethical and juridical point of view (Andrews, Citation2006). Restraints, especially physical ones, are thought to cause more harm than benefit (Engberg, Castle, & McCaffrey, Citation2008; Tolson & Morley, Citation2012).

In addition, choosing restraints often revokes ethical issues with regard to human rights, dignity and well-being (Gallagher, Citation2011). The UN convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (Citation2007) states in this respect that the existence of a disability, including dementia, does not justify the use of restraints. In recent years many attempts have been made to decrease the use of restraints and to search for alternatives (Zwijsen et al., Citation2014), such as surveillance technology (Niemeijer et al., Citation2010) and environmental or activity-based alternatives (Burns, Jayasinha, Tsang, & Brodaty, Citation2012).

The use of restraints, and efforts to reduce their use, is also an issue becoming part of the international political agenda. Research in Australia, the UK, the United States and the Netherlands shows that the use of restraints in these countries is currently regulated by the criterion of ultimum remedium, meaning that ‘restraints should only be used as a last resort after other, less restrictive interventions have been considered (and rejected)’ (Romijn & Frederiks, Citation2012). The New Dutch Care and Coercion Act introduced the term ‘involuntary care’ which refers to all care resisted by the patient or the legal representative. More specifically, the Act entails five categories of involuntary care: (1) the administration of nutrition, moisture, or medication for somatic disorder; (2) the administration of medication that affects the behaviour or the freedom of movement of the client due to a psychogeriatric or a psychiatric disorder or intellectual disability; (3) restraints of freedom such as isolation and physical restraint; (4) restraints to supervise the client at a distance, such as a video camera in the bedroom; and (5) restraints that prevent individuals with dementia from managing their own life, so that the client has to do or to stop doing something against his/her will (Frederiks, Schippers, Huijs, & Steen, Citation2017).

The term ‘involuntary care’ clearly incorporates a much broader definition than just the term restraints. The essence of the Act entails that involuntary care should be avoided, and if at all applied it should be the least invasive form.

The increased focus on the prevention of the use of coercive measures and involuntary care, and the search for (less restrictive/invasive) alternatives asks for an exploration of the perspective of the patient and an analysis of the meaning of their behaviour (Zwijsen et al., Citation2014). Caregivers should be aware if and how a patient resists the care provided. However, gaining insight into the experiences of patients is not an easy task. In people with dementia this is even more difficult as the progressive nature of the disease leads to a decrease in the persons’ abilities to communicate (Alzheimer's Society, Citation2016). Consequently, in order to ‘capture’ the experiences of people with dementia, caregivers become more and more dependent upon the interpretation of the person's behavioural expressions which may reflect unmet needs and result in resistance to care received (Ayalon, Gum, Feliciano, & Arean, Citation2006; Cohen-Mansfield, Dakheel-Ali, & Marx, Citation2009).

Behaviour, including challenging behaviour, of people with dementia is increasingly seen as an important means of communication and less as a manifestation of the disease (Dupuis, Wiersma, & Loiselle, Citation2012; Kitwood, Citation1997; Smith & Buckwalter, Citation2005). Although behaviour is often seen as one of the few ways to get insight into the experience of dementia, it's interpretation is complex because of the influence of not only psychosocial factors but also the neurological deficits (Zwijsen, van der Ploeg, & Hertogh, Citation2016). At the same time, tools are being developed to gain greater understanding of the behaviour of people with severe dementia aimed at improvement of their quality of life (Clare et al., Citation2013).

This article focuses on the behavioural expressions of people with severe dementia in nursing homes that are interpreted by their formal and informal caregivers as a possible expressions of their experience of involuntary care.

Methods

Concept mapping

In this study Concept Mapping (CM) was conducted, developed by Trochim (Citation1989). CM is a computer-assisted integrated mixed method approach, designed to elucidate a complex subject in a short amount of time. CM is participatory in nature and consists of five phases: (1) brainstorming, (2) rating, (3) sorting, (4) statistical analysis & visual representation and (5) interpretation. The use of CM is well established and has been applied to many topics in (mental) health care (Brown, Citation2004; De Ridder, Depla, Severens, & Malsch, Citation1997; Johnsen, Biegel, & Shafran, Citation2000; Nabitz, van Randeraad-van der Zee, Kok, van Bon-Martens, & Serverens, Citation2017; Shern, Trochim, & LaComb, Citation1995). The systematic techniques used in the rating and sorting phase are broadly used in research and add rigor to the data collection (Rosas & Kane, Citation2012). The analysis process consists of quantitative techniques of multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis, and helps interpreting the data by producing visual maps (Kane & Trochim, Citation2007).

In this research, the concept mapping sessions took place in presence of one of the researchers and under the supervision of an independent chair who is specialised in working with the CM method. The sessions lasted approximately two hours.

All statements and cluster names were translated into English for the purpose of this article by a professional translator. To enhance validity of the translation discussions took place between the translator and one of the researchers in order to prevent interpretation differences.

The Medical Ethics Review Committee of VU University Medical Center committee confirmed that the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) does not apply to this study and that an official approval of this study is not required.

Participants

We chose to include participants closely involved with people with dementia living in nursing homes. Specialists (elderly care physicians & psychologists) and nurses, working in different homes with varying years of working experience, and relatives of people with dementia took part in three separate conceptmapping meetings. Their close relation to (a) person(s) with enables them to describe the behavioural expressions of people with dementia they interpret as a reaction to involuntary care. Each group had varying numbers of participants (see ).

Table 1. Participants concept mapping meetings.

Procedure

Step 1 – The aim of the brainstorming phase was to collect a wide range of participant-generated statements regarding the subject, in this case the behaviour of people with severe dementia in relation to ‘involuntary care’. The session started with an explanation of the concept of involuntary care, by providing the definition and introducing all five categories of involuntary care as specified in the Dutch Care and Coercion Act. Thereafter, statements were collected in response to the focus sentence ‘When a person with dementia experiences involuntary care I can tell by / because he or she…’, which intended to capture behavioural expressions of people with severe dementia in response to ‘involuntary care’. All statements were instantly entered into the computer. Engagement in discussions was avoided unless clarification of statements was needed. Duplicate statements were not considered and consensus was reached about very similar statements. The brainstorming phase was considered complete when saturation of participant statements was reached, that is, when no new statements were being generated.

Steps 2 and 3 – Prioritising and Clustering. For the prioritising activity, participants were asked to individually rate the brainstormed statements on a Likert-type scale for importance (1 = least important; 5 = most important). For the clustering activity, participants were, also individually, asked to sort the brainstormed statements into groups that were compatible with regard to content, and to provide a name for each group.

Step 4 – In this phase the individual rated and sorted data of steps 2 and 3 were statistically analyzed with the use of the statistical package Ariadne. The analysis process generates a ‘group product’ consisting of visual maps which are easy to understand and to evaluate during the interpretation phase.

Step 5 – In the interpretation phase the maps were interpreted in multiple face-to-face meetings within the research group. It involved a group discussion in order to stimulate response and reach consensus about the number of clusters, their names and the signification of the axes in the visual map. This phase also included the comparison of the results of the three respondent groups in this study.

Results

To enhance the understanding of the abundancy of the results in this study, this section includes three parts: (1) top 10 of statements; (2) overview of the clusters and (3) interpretation of the axes in the concept maps. Reference is made to Appendix A1 for all statements per group and per cluster.

Top 10 of statements

The focus sentence ‘When a person with dementia experiences involuntary care I can tell by / because he or she…’, was completed 66 times in the group of elderly care physicians and psychologists (specialists), 73 times in the group of nurses and 48 times in the group of relatives. The 10 statements that were given the highest priority are, per group, listed in (see Appendix A1 for all statements per group and per cluster).

Table 2. The 10 most important statements per group (mean priority; standard deviation).Table Footnotea

Many of the statements are related to forms of (physical) aggression. Some behavioural expressions are directly related to the care provided, like refusal of medication, someone keeping his mouth shut or a person pulling out an IV. Other behaviour occurs in relation to others, such as aggression aimed at the caregiver, the person trying to ‘hijack’ caregivers, hitting, or severe wrestling. Showing fear (specialists and nurses) or sorrow (nurses and relatives) as a reaction to involuntary care are exceptions in the top-10s, and in contrast with the other direct and/or aggressive reactions.

Overview of clusters

provides an overview of the generated clusters of each of the respondent groups. These clusters are based on their individual rated and sorted data (steps 2 and 3). The content of each cluster consists of compatible statements summarized by the name of the cluster (see Appendix A1 for statements per cluster). Their number and names were determined in consultation with our research group (steps 4 and 5). All clusters can also be found on the presented concept maps in the next paragraph.

Table 3. Overview of behavioural clusters and their average ratings per respondent group.Table Footnotea

shows consensus between all three respondent groups on aggressive behaviour or concrete expressions of resistance being among the most relevant expressions shown by people with dementia in relation to involuntary care. Only for nurses behaviour related to resistance to eating & drinking is found to be an even more relevant reaction. Like resisting medication this reflects behaviour nurses may encounter in their daily work with people with dementia. For relatives behaviour expressing sadness is important, which is comparable to not feeling good in the nurses’ group and passive behaviour uncharacteristic of the person and non-specific behaviour indicating discomfort in the specialists group.

Signification of axes in the concept maps

In multiple research group discussions (steps 4 and 5) the axes of the concept maps were named which provide insight into the dimensions the participants used to sort the statements.

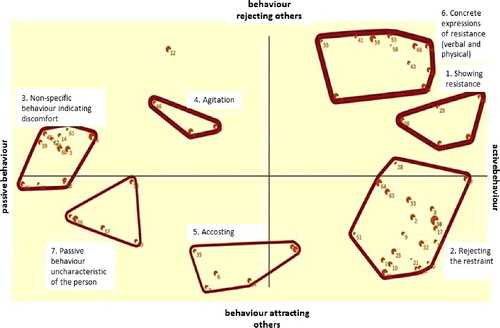

Concept map specialists

The x-axis in this map () represents a continuum between passive- and active behaviour. The latter pole reflects behaviour (clusters 1, 2, and 6) that can be interpreted in direct relation to the care provided. Passive behaviour on the other end of the continuum is formed by behaviour reflecting more general discomfort (cluster 3) which is also picked up in case this behaviour is uncharactristic for that person (cluster 7). Specialists also sort behaviour in reaction to involuntary care along the dimension of behaviour rejecting others (aggressive component, clusters 1, 4, and 6) to behaviour aimed at attracting people's attention (component of helplessness, cluster 5); this is shown on the y-axis.

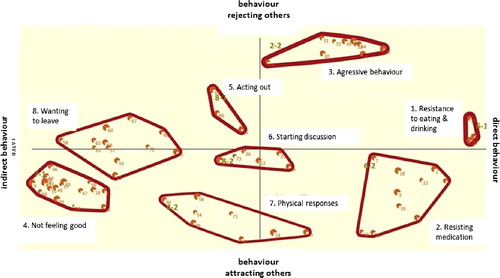

Concept map nurses

Nurses differentiate on the x-axis (see ) behaviour that is a direct reaction to the care provided (resistance to eating & drinking (1) or resisting medication (2)) or indirect behaviour reflecting more general signs of disagreement with their situation or the care they receive, such as wanting to leave (8) and not feeling good (4). The y-axis is formed by a continuum between externalized behaviour, best reflected by the cluster aggressive behaviour (3) at the top part of the map, and internalized behaviour, which is situated at the bottom part of the map and best reflected in the cluster physical responses (7) which is shown by people with dementia who have no other option to express their discontent with care.

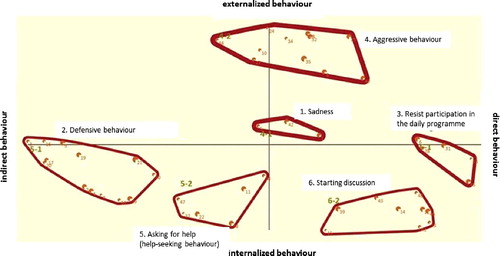

Concept map relatives

Relatives (see ) seem to distinguish on the right side of the map, more or less intentional and thought-through behaviour by which people with dementia express their discomfort with the care provided. This behaviour is mainly reflected in the cluster not willing to take part in daily activities (3) and to a lesser extent in the cluster going into discussion (6). The left side of the map shows behaviour that can be interpreted as a more primitive reaction to involuntary care. This behaviour is dominated by the cluster repelling behaviour (2) which includes for example shying away from any contact by caregivers or closing ones mouth when offered food or medication.

Figure 3. Concept map of relatives (N = 9). This concept map includes six clusters representing related behavioural expressions, and two axes representing behavioural dimensions.

Similar to the specialists on the y-axis a continuum from behaviour attracting others (bottom) to behaviour rejecting others (top) is shown. Relatives also placed multiple aggressive behavioural expressions (cluster agression (4)) opposite behaviour attracting others, which includes behaviour by which the person with dementia tries to, in contact with others, solve their discomfort with the care provided.

Discussion

This article aimed at providing insight into the behavioural expressions of people with dementia in nursing homes in reaction to involuntary care. The results of this study show that specialists, nurses and relatives interpret a large variety of behavioural expressions of people with dementia as possible reactions to the experience of involuntary care. Expressing discomfort or dissatisfaction with care clearly comes in many forms. This ability of formal and informal caregivers to detect and interpret this behaviour supports findings of other studies in which behaviour of people with dementia is increasingly interpreted as meaningful behaviour and an attempt to communicate unmet needs rather than symptoms of a dysfunctional cognitive status (Ayalon et al., Citation2006; Ishii, Streim, & Saliba, Citation2012; Konno, Kang, & Makimoto, Citation2014).

A closer look at the large variety of possible behavioural expressions in reaction to involuntary care, reveals some interesting observations. First of all, we see that behaviours clustered as aggressive behaviour or concrete actions of resistance are present in all respondent groups and stand out the most in terms of importance. Together with agitation these behavioural expressions are seen as highly relevant reactions to involuntary care. This finding is in line with literature where rejection-of or resistance-to care is often the main focus of research (Ishii et al., Citation2012; Konno et al., Citation2014), and may seem logical as these manifestations of discontent are often hard to ignore. However, despite literature suggesting that depressive symptoms are often under-recognized (Macfarlane & O'Connor Citation2016), our study shows that also more subtle behaviours are on the minds of (formal) caregivers of people with dementia. Clear examples are formed by the clusters sadness, not feeling good, and passive behaviour, which are highly scored on the rating list of most important behaviours in reaction to the experience of involuntary care. Therefore, the whole range of behavioural expressions revealed in this study should alert caregivers to also search for a possible relation to involuntary care.

Our study shows how physicians, relatives and nurses, all from their own perspective, can play a relevant role in observing and recognizing behaviour of people with dementia in reaction to involuntary care. However, relating such behaviour of people with dementia to involuntary care is not always straightforward. In our study a distinction became apparent between behavioural expressions that are relatively easy to relate to involuntary care and behaviour in which case this relation is much more ambiguous. This is reflected in the dimension direct versus indirect behaviour which was used by both specialists and nurses in sorting the behavioural expressions related to involuntary care. For example, a person closing his mouth or turning his head when being fed is easily interpreted as a reaction to that care being experienced as involuntary, while more general forms of discomfort like sadness or apathy are much more difficult to relate to the care provided. Similarly, specialists and relatives differentiated between behaviour rejecting others and behaviour attracting others. For example, aggressive behaviour will reject others, and often occurs in direct reaction to the care provided. In contrast, the relation to involuntary care is much more difficult to detect when you, for example, encounter a person who is trying to attract someone's attention by constantly calling out. The difficulty of interpreting help-seeking behaviour as a reaction to involuntary care might also explain why this dimension was not used by nurses to sort the behavioural expressions of people with dementia.

It is important to realize observing behaviour is a starting point of reducing involuntary care. The large variety of possible behavioural expressions points out the importance to not just ‘hear’ or ‘observe’ the behaviour of people with dementia but to also try and ‘understand the meaning’ of the behaviour. Multiple models have attempted to unravel the complexity of what is often referred to as problematic or challenging behaviour (Algase, Beck, & Kolanowsk, Citation1996; Smith, Gerdner, Hall, & Buckwalter, Citation2004; Teri, Citation1997). These models stress the importance of detecting factors that cause or contribute to the behavioural symptoms as well as understanding the meaning and consequences of the problematic or challenging behaviour, in order to develop strategies to improve care. Contributory factors in the development and course of behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia include not only pain (Gerlach & Kales, Citation2016), but also interpersonal, family and social contexts (Feast et al., Citation2016; Moniz-Cook et al., Citation2012), and the familiarity of caregivers with the traits and habits of a person with dementia (Smith & Buckwalter, Citation2005). Our research stresses the importance of including the experience of involuntary care as a possible explanation for the behavioural symptoms expressed.

Strengths and limitations

The fact that the insight our study provides in the behavioural expressions of people with dementia in nursing homes in reaction to involuntary care, is not directly drawn from the actual experience of people with dementia themselves may be seen as a limitation of our study. However, our study is the first, as far as we know, to explore the interpretation of specialists, nurses and relatives of behavioural expressions of people with dementia as possible reactions to the experience of involuntary care. Our study is also special because we focus on a very broad concept of involuntary care. Recognizing behavioural reactions to involuntary care in this way is a good starting point in raising awareness and detecting involuntary care. Caregivers may benefit from training to gain a greater understanding of the behavioural responses of people with dementia (Clare et al., Citation2013). We used multiple respondent groups in order to capture the whole spectrum of possible behaviour expressed, hereby strengthening the validity of our findings. A challenge in analyzing our data was formed by the necessary integration of the three separate concept maps that were generated. This difficulty could have been avoided in case we had merged statements from all three groups generated in the brainstorm phase before moving on to the sorting and prioritizing tasks. However, this may have led to an increased work load for all respondent due to the extra meeting this would have implied. More importantly, putting all respondents in one group was prevented because of the limitations this might have imposed on respondent groups to experience maximum freedom in reasoning from their own perspective. Another possible limitation of our study is formed by the difficulty to prioritize the generated statements. The background of this difficulty lies in the fact that respondents were of the opinion that all behaviours pointed out to in the brainstorm phase were relevant in relation to involuntary care. To ease the task on two occasions respondents prioritized statements together and four people refrained from the prioritizing task altogether. Despite the input of respondents lost here, we feel enough data was left to continue the concept mapping process. Although alternative methods, like in-depth interviews might have been used in this study, we feel the combination of both qualitative and quantitative analyses of concept mapping makes this method more data-driven. Through the usage of group processes, joint discussion and exploration, this method allows the encouragement of participants to bring up more ideas than would appear in individual approaches like interviews. Moreover, concept mapping generates the conceptual framework by a statistical algorithm, which can be replicated by others (Kane & Trochim, Citation2007; Rosas & Kane, Citation2012).

Conclusion

According to formal and informal caregivers, people with severe dementia may express a large variety of behavioural symptoms in reaction to the experience of involuntary care. This includes not only the more obvious and direct behavioural expressions like aggression, resistance and agitation, but also more subtle behaviour such as sorrow, general discomfort or discontent. This asks for constant alertness of health care personnel in order to detect all of these behavioural expressions; a process in which also the signals of relatives of people with dementia should be taken into account. Improved awareness of all behaviour as a possible reaction to the experience of involuntary care is an important step in detecting involuntary care. Understanding the meaning and consequences of the behavioural expressions should then follow in order to develop strategies to improve dementia care by avoiding involuntary care to its maximum.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Algase, D. L., Beck, C., Kolanowski, A., Whall, A., Berent, S., Richards, K., & Beattie, E. (1996). Need-driven dementia-compromised behavior: An alternative view of disruptive behavior. American Journal of Alzheimers Disease and Other Dementias, 11, 10–19.

- Alzheimer's Society (2016). Communicating. London: Author.

- Andrews, G. J. (2006). Managing challenging behaviour in dementia: A person centred approach may reduce the use of physical and chemical restraints. British Medical Journal, 332, 741.

- Ayalon, L., Gum, A. M., Feliciano, L., & Arean, P. A. (2006). Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions for the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia: A systematic review. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 2182–2188.

- Burns, K., Jayasinha, R., Tsang, R., & Brodaty, H. (2012). Behaviour management a guide to good practice: Managing behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Canberra: DCRC and DBMAS Commonwealth. Retrieved from http://dementiaresearch.com.au/images/dcrc/output-files/328-2012_dbmas_bpsd_guidelines_guide.pdf

- Brown, J. (2004). Fostering children with disabilities: A concept map of parent needs. Children and Youth Services Review, 29, 1235–1248.

- Clare, L., Whitaker, R., Woods, R. T., Quin, C., Jelley, H., Hoare, Z., … Wilson, B. A. (2013). AwareCare: A pilot randomized controlled trial of an awareness-based staff training intervention to improve quality of life for residents with severe dementia in long-term care settings. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(1), 128–139.

- Cohen-Mansfield, J., Dakheel-Ali, M., & Marx, M. S. (2009). Engagement in persons with dementia: The concept and its measurement. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17, 299–307.

- De Ridder, D., Depla, M., Severens, P., & Malsch, M. (1997). Beliefs on coping with illness: A consumer's perspective. Social Science and Medicine, 44, 553–559.

- Dupuis, S. L., Wiersma, E., & Loiselle, L. (2012). Pathologizing behavior: Meanings of behaviors in dementia care. Journal of Aging Studies, 26, 162–173.

- Engberg, J., Castle, N. G., & McCaffrey, D. (2008). Physical restraint initiation in nursing homes and subsequent resident health. The Gerontologist, 48, 442–452.

- Feast, A., Orrell, M., Charlesworth, G., Melunsky, N., Poland, F., & Moniz-Cook, E. (2016). Behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia and the challenges for family carers: Systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(5), 429–434.

- Frederiks, B., Schippers, B., Huijs, M., & Steen, S. (2017). Reporting of use of coercive measures from a Dutch perspective. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities, 11(2), 65–73. doi:10.1108/AMHID-11-2016-0039

- Gallagher, A. (2011). Ethical issues in patient restraint. Nursing Times, 107(9), 18–20.

- Gerlach, L. B., & Kales, H. C. (2016). Learning their language: The importance of detecting and managing pain in dementia. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(2),155–157. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2016.11.012

- Hamers, J. P., & Huizing, A. R. (2005). Why do we use physical restraints in the elderly ? Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie, 38, 19–25.

- Ishii, S., Streim, J. E., & Saliba, D. (2012). A conceptual framework for rejection of care behaviors: Review of literature and analysis of role of dementia severity. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 13, 11–23.

- Johnsen, J. A., Biegel, D. E., & Shafran, R. (2000). Concept mapping in mental health: Uses and adaptations. Evaluation and Program Planning, 23, 67–75.

- Kane, M., & Trochim, W. M. K. (2007). Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Konno, R., Kang, H. S., & Makimoto, K. (2014). A best-evidence review of intervention studies for minimizing resistance-to-care behaviours for older adults with dementia in nursing homes. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(10), 2167–2180. doi:10.1111/jan.12432

- Macfarlane, S., & O'Connor, D. (2016). Managing behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia. Australian Prescriber, 39, 123–125.

- Moniz-Cook, E., Swift, K., James, I., Malouf, R., de Vugt, M., & Verhey, F. (2012). Functional analysis-based interventions for challenging behaviour in dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online), 2, CD006929.

- Nabitz, U., van Randeraad-van der Zee, C., Kok, I., van Bon-Martens, M., & Serverens, P. (2017). An overview of concept mapping in Dutch mental health care. Evaluation and Program Planning, 60, 202–212.

- Niemeijer, A. R., Frederiks, B. J. M., Ingrid, I., Riphagen, I. I., Legemaate, J., Eefsting, J. A., & Hertogh, C. M. P.M. (2010). Ethical and practical concerns of surveillance technologies in residential care for people with dementia or intellectual disabilities: An overview of the literature. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(7), 1129–1142.

- Romijn, A., & Frederiks, B. J. M. (2012). Restriction on restraints in the care for people with intellectual disabilities in the Netherlands: Lessons learned from Australia, UK, and United States. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 9(2), 127–133.

- Rosas, S. C., & Kane, M. (2012). Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: A pooled study analysis. Evaluation and Program Planning, 35, 236–245.

- Shern, D. L., Trochim, W. M. K., & LaComb, C. A. (1995). The use of concept mapping for assessing fidelity of model transfer: An example from psychiatric rehabilitation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 18, 143–153.

- Smith, M., & Buckwalter, K. (2005). Behaviors associated with dementia. American Journal of Nursing, 105(7), 40–52.

- Smith, M., Gerdner, L. A., Hall, G. R., & Buckwalter, K. C. (2004). History, development, and future of the progressively lowered stress threshold: A conceptual model for dementia care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52, 1755–1760.

- Teri, L. (1997). Assessment and treatment of neuropsychiatric signs and symptoms in cognitively impaired older adults: Guidelines for practitioners. Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 2, 152–158.

- Tolson, D., & Morley, J. E. (2012). Physical restraints: Abusive and harmful. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 13(4), 311–313.

- Trochim, W. K. M. (1989). An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 12, 1–16.

- UN General Assembly: Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities A/RES/61/106: Resolution. 24 January 2007. Available from URL: http://www.refworld.org/docid/45f973632.html (accessed January 18th 2018).

- Zwijsen, S.A., Smalbrugge, M., Eefsting, J. A., Twisk, J. W.R., Gerritsen, D. L., Pot, A. M., & Hertogh, C. M. P.M. (2014). Coming to grips with challenging behavior: A cluster randomized controlled trial on the effects of a multidisciplinary care program for challenging behavior in dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 15(7), 531.e1–531.e10.

- Zwijsen, S. A., van der Ploeg, E., & Hertogh, C. M. (2016). Understanding the world of dementia. How do people with dementia experience the world ? International Psychogeriatrics, 28(7), 1067–1077. doi:10.1017/S1041610216000351

Appendix A1 Statements per Cluster for each of the Three Respondent Groups

When a person with dementia experiences involuntary care I can tell by / because he or she …

Specialists (elderly care physicians & elderly care psychologists)

n = 12

66 statements

8 clusters, no rotation

Statements per cluster:

1. Showing resistance

1 throws away pills

11 spits out /does not swallow/ hides food in mouth

29 destroys/ puts aside equipment

38 is defiant

45 resists / puts up a fight

2. Rejecting the restraint

2 rattles the door

8 makes up excuses

9 takes very small sips /delays eating

10 says no / shakes head

16 walks away

17 tries to break free

19 complains to others about medication

20 indicates that the restraint is in the way

21 indicates desire to be free

22 asks where the exit is

25 begs, begs specifically to be released

28 refuses food

30 barricades room

31 sends caregiver away

32 closes/draws the curtains

33 hides things

34 locks the door

47 protests verbally

51 withdraws from care physically/literally

63 crawls under the blanket

64 turns his/her back; turns head away

65 starts discussion

3. Non-specific behaviour indicating discomfort

3 urinary incontinence

13 regression

14 rhythmic movement

15 apathy

18 disassociation, paranoia, going into psychosis

39 increased vigilance

48 individual shows increased signs of arousal

49 resignation

52 heightened muscle-tension

56 anxiety

60 eyes wide-open

61 motor unrest

62 rapid, shallow breathing

4. Agitation

4 walks about agitated

27 self-harming behaviour

46 verbal agitation

5. Accosting

5 accosts everybody

6 responds negatively to known/familiar person

7 rejects known acquaintances

24 question of fault, what have I done wrong

35 splitting

40 clinging behaviour

6. Concrete expressions of resistance (verbal and physical)

23 retaliation, postponed aggressive behaviour

26 smashes windows

41 yelling

42 verbal aggression

43 cursing/ swearing

44 aggression directed at the person providing care

53 becomes physically aggressive

55 anger

58 spitting

59 pinching

66 throws food/cutlery

7. Passive behaviour uncharacteristic of the person

36 institutionalization

37 loss of sense of social norms

50 closed attitude

54 displaying sadness

57 loss of individuality

[..]. …(no name; only 1 statement)

12 breaking through medications

Nurses

n = 23

73 statements

clusters rotated to ensure ‘aggression’ (cluster 4) is in ‘the same’ position as the cluster aggression in the group of relatives [to increases comparability of the clusters]

Statements per cluster:

1. Resistance to eating & drinking

1 protests against eating/drinking

26 pushes food and drinks away

27 strikes food/drink away

2. Resisting medication

2 refuses medication

3 hides medication

5 spits out medication/ vomits

6 constipation

7 keeps mouth closed tightly

22 holds medication in hand

28 squirrels away medication

32 develops nausea/ abdominal pain

35 deliberately chews slowly

38 incontinence

3. Aggressive behaviour

4 fends nurses off

10 strikes things from nurses’ hands

19 anger

20 verbal aggression

31 physical aggression

33 throws crockery

40/43 hits

44 scratches

45 bites

70 breaks things

4. Not feeling good

8 withdraws

9 closes down/does not respond

15 tense posture

18 becomes restless

21 sadness

24 suspicion

29 cannot be distracted

37 passive attitude

46 clinging behaviour

47 sexual disinhibition

49 anxiety

50 insecurity

52 euforia

53 dependence

55 disconnects from environment

59 picking behaviour

64 internal unrest

65 indifference

69 apathy

5. Acting out

11 ‘says no’ verbally

63 holds nurses hostage

66 anger towards family

6. Starting discussion

12 asks why

17 turns face away

23 denial/ 'don't need that’

34 indicates ‘ I am not sick’

36 verbally indicates ‘being done’

73 refuses to sign consent to camera surveillance

7. Physical responses

13 perspires

14 red face

30 angry facial expression

39 drowsiness

41 goes rigid

54 physical unrest

56 unable to sleep

71 day-night reversal

8. Wanting to leave

16 stands up and walks away

25 places past experiences in the present resulting in delusions

48 intensification of existing behaviour

51 cries

57 shouting behaviour

58 compulsions

60 increased repetitive movements aimed at leaving

61 climbs out of the bed

62 atempts to escape

67 wanders

68 crawls

72 involves other residents in the escape plan

Relatives

n = 13, but 2 excluded because of ‘illogical’ clustering

48 statements

clustering reduced to 6 clusters + rotated slightly in order to place ‘aggression’ (cluster 4) in ‘the same’ position as the cluster aggression in the group of nurses [to increase comparability of the clusters]

Statements per clusters:

1. Sadness

1 gets restless

5 gets angry

42 sadness

2. Defensive behaviour

2 turns face away

3 clenches jaw tightly

4 grimaces

7 rejection

9 perspires

16 spits things out

17 does not swallow

19 shrinks back

20 forgets to swallow

21 does not want to be touched

29 rejection of unfamiliar things

30 tries to get out of wheelchair

36 taps to draw attention

3. Resist participation in the daily programme

6 indignation

28 stays in bed

31 barricades room door

33 kidnaps carers

45 arguments about daily schedule (wandering)

4. Aggressive behaviour

8 lapses into resignation/apathy

10 resistance

23 vehement struggle

24 foams at the mouth

25 furious

26 very strong resistance / not eating

27 pulls out drip

32 physically aggressive behaviour

34 strikes

35 verbal aggression

40 demolishes door access code box

44 severe hallucinations

5. Asking for help (help-seeking behaviour)

11 says 'I don't want that’ / verbally

18 keeps muscles stiff

22 asks for the manager

37 calls out to draw attention

38 shouts 'I want to go home’ repetitively

47 refuses to wear particular articles of clothing

6. Starting discussion

12 promises to do it later, procrastinates

13 tells the other person to do it him/herself

14 utters 'I am not crazy’

15 indicates already having had something (f.e. fluids)

39 ask where the exit is

41 interferes with the daily routine at the nursing home, wants to influence

43 says unkind things about other people in the group

46 wants to remain in control at all costs

48 indignation