ABSTRACT

Objectives: Dementia causes dramatic changes in everyday-living for spouses. Occured changes in marital relationship, force spouses to perform more both mentally and physically. Leading to a spousal perceived burden. To improve understanding of spouses’ needs, spouses lived experiences is needed. The aim was to identify and synthesise qualitative studies on spouses’ lived experiences of living with a partner with dementia.

Methods: A systematic search was undertaken in January 2017. Six databases (CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, PubMed, PsycINFO and Sociological Abstracts) were searched, using search terms in accordance with PICo. A descriptive synthesis and a thematic synthesis were undertaken.

Findings: Fifteen studies met the inclusion criteria. Three themes derived from the analysis 1) Noticing changes in everyday life 2) Transformation to a new marital relation in everyday life, with corresponding sub-themes; changes in marital relationship, management of the transitioned marital relation in everyday life 3) Planning the future.

Conclusion: Findings provide an overview of how spouses notice changes and transform their marital relationships in everyday-life. Findings offer a deeper understanding of changes that occurs over time while the partner is living at home. Findings contribute with knowledge on spouses’ experiences of changes in early-stages of dementia. Interventions supporting spouses are needed.

Introduction

Dementia is a common reason for needing time-intensive care, and spouses are among caregivers very likely to support their partners in activities of daily living (ADL) (National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) AARP Public Policy Institute, Citation2015). Previous reviews have found an association between perceived caregiver burden and informal care due to the hours involved in care, stress, depression, anxiety, social isolation and lack of social resources (Allen et al., Citation2017; Chiao, Wu, & Hsiao, Citation2015; Ornstein & Gaugler, Citation2012; Sansoni, Anderson, Varona, & Varela, Citation2013). Assuming a role as caregivers, spouses often experience grief and multiple losses, including loss of partner and personal freedom (Chan, Livingston, Jones, & Sampson, Citation2013).

Western Europe has the highest prevalence of persons living with dementia, estimated at 7.0 million, and this number is expected to increase by 40% over the next 20 years (World health Organization, Citation2012). Due to challenges in managing the changes brought about by dementia, multiple strategies have been launched. Worldwide, a multisector approach that targets the needs and perspectives of persons with dementia and their relatives has been prioritised (Sundheds- og Ældreministeriet [The Ministry of Health], Citation2016; World health Organization, Citation2012). Interventions that are aimed at caregivers predominantly focus on education programmes, including the provision of coping and support strategies and self-management support (Dam, De Vugt, Klinkenberg, Verhey, & Van Boxtel, Citation2016; Gilhooly et al., Citation2016; Huis in het Veld, Verkaik, Mistiaen, van Meijel, & Francke, Citation2015; Jensen, Agbata, Canavan, & McCarthy, Citation2015; Letts et al., Citation2011; Li, Cooper, Austin, & Livingston, Citation2013; Vandepitte et al., Citation2016).

Education programmes have shown a moderate reduction in caregiver burden and depression (Jensen, Agbata, Canavan, & McCarthy, Citation2015; Parker, Mills, & Abbey, Citation2008). Coping strategy interventions are efficacious in decreasing depression, but are followed by an increase in dysfunctional coping immediately after the interventions have ended (Li et al., Citation2013). A review of social support interventions showed no positive effects in quantitative studies; however, qualitative studies showed that spouses felt more emotionally supported and less socially isolated (Dam et al., Citation2016).

Most former reviews of qualitative studies focus on the lived experience from the perspective of various caregivers or from a couple's mutual perspective (Evans & Lee, Citation2014; Quinn, Clare, & Woods, Citation2009; Wadham, Simpson, Rust, & Murray, Citation2016). Changes in marital relationship are often followed by spouses’ experience of loss, grief and a feeling of uncertainty in relation to the new living situation (Evans & Lee, Citation2014). Hence, some studies report positive outcomes of spouse caregiving (Pretorius, Walker, & Heyns, Citation2009; Shim, Barroso, Gilliss, & Davis, Citation2013) Studies of the lived experience from the perspective of spouses of people with dementia are sparse. Spouses seem to manage these changes by accepting and adapting to their new circumstances (Evans & Lee, Citation2014; Pozzebon, Douglas, & Ames, Citation2016). Studies on how mariatal life is managed in everyday life in the early stages of dementia could yield insight into the above-mentioned challenges. However, to improve our understanding of the needs of spouses living with a person with dementia, a systematic review of previous studies is needed. Such a review could support the development of interventions targeting the early stages of dementia while living at home. The aim of this study is thus to identify and synthesise previous qualitative studies on what characterises spouses’ lived experiences of living with a partner diagnosed with dementia, and how changes in their everyday lives are managed.

Methods

This systematic review and thematic analysis of qualitative studies of spouses’ lived experiences follows Joanna Briggs’ Institute (JBI) review guidelines (Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2014). Lay representatives with experiences of being spouses to a partner with dementia participated in The Review Panel (panel). The panel consisted of a voluntarily established spousal caregiver support group including five indviduals with a partner with dementia or a parter who had lost a husband or wife due to dementia. The first author and the panel met twice on a joint meeting and discussed the aim of the study and the results in order to reflect on the lay perspective during the review process.

Search strategy and criteria

A systematic search was conducted in six databases: CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, PubMed, PsycINFO and Sociological Abstracts, from 24 January to 10 February 2017.

The PICo process as recommended by Joanna Briggs was used to formulate a focussed research question that contained research terms that related to P (population), I (phenomena of interests) and Co (context) (Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2014), and the systematic search in all six databases was structured around PICo, illustrated in . The systematic search was first conducted in PsycINFO and then adapted to the other databases. Thhe phenomenon of interest was defined according to Birte Bech-Jørgensen's concepts of everyday life and used to formulate research questions and to choose relevant search terms (Bech-Jørgensen, Citation1994). According to Bech-Jørgensen, Citation1994, ‘everyday life’ can be defined as the circumstances under which a person is living, and the term ‘management’ used in the research question refers to how individuals are able to manage these circumstances (Bech-Jørgensen, Citation1994). Spouses living with a partner with dementia at home were chosen in order to capture the challenges experienced in the early stages of dementia.

Table 1. Example of the systematic search, built in PsycINFO, illustrating a facet search, including facets 1, 2 and 3.

Subject headings were adjusted in each database due to variations in the predefined subject heading in the thesaurus in the different databases. Truncation of search terms was used to capture word inflection, except in PubMed because of an automatic deactivation of underlying functions. A methodological filter was used in PsycINFO. In the remaining databases, manual methodological filters (Glanville et al., Citation2008; Saini & Shlonsky, Citation2012) were developed due to the unavailability of methodological limits in the databases (). Inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in .

Table 2. Methodological limits used in CINAHL, Cochrane, Embase, PubMed and Sociological Abstracts. Filters varied between the databases, illustrated in facet search as the fourth facet.

Table 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion procedure

The inclusion process consisted of two screening steps. Firstly, all identified articles from the systematic search were screened by title and abstracts according to pre-defined criteria. Secondly, the identified studies were divided between authors (two thirds each), so that full-text articles where screened by at least two authors according to the criteria and quality assessed by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (Critical Appraisal Skills Program, Citation2017). Criteria and quality assessment were discussed at a joint meeting, and any discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached.

Analysis

The analysis consisted of two steps. Firstly, a descriptive analysis was performed by the first author, aiming to index and summarise the included studies. Indexed studies are presented in a review matrix () including author, year, country and journal, purpose, methods, analytical strategy and results, as headings (Garrard, Citation2007). Secondly, a thematic analysis, inspired by Thomas, Harden, Thomas, and Harden (Citation2008), was conducted involving all authors in the discussion of the themes. Study results with particular focus on spouses’ experiences of stages, changes and management with respect to the duration and the development of dementia formed the basis of the descriptive themes. Responses received from the panel confirmed the importance of looking deeper into how everyday life is experienced as dementia progresses, and this helped qualify the aim of the review and the following analysis.

Table 4. A reviw matrix of included studies.

Data were obtained by following the steps in the inductive thematic analysis (Thomas et al., Citation2008). The analysis had particular focus on coding what characterised the spouses’ lived experience, and how the challenges experienced in everyday life were managed. The analysis was constructed as follows:

| (1) | Line-by-line codes and related themes were extracted on the basis of the studies’ findings with the research question in mind. | ||||

| (2) | Freely lined codes and related themes were organised and then reorganised into broader descriptive themes, within and across the studies’ findings. Firstly, articles focusing solely on changes and management were coded into two broader themes. Secondly, articles with both themes incorporated were coded and added to the two broader themes. | ||||

| (3) | The descriptive themes formed the basis for the next level of the analysis where a synthesis was made across the studies’ findings, leading to the final interpretation. | ||||

After several revisions and discussion of the analysis, a timeline was drawn up based on the thematic analysis, showing how everyday life was experienced and managed from the time of pre-diagnosis of dementia to the time where the marital relationship started to transform and to the time of consideration about the future.

Quality assessment

As the literature search produced only a limited number of studies, it was decided to reject no studies due to low quality. The quality assessment of the individual studies is inspired by Joanna Briggs and presented as a narrative summary of the overall methodological quality of all the studies (). Q1 till Q10 represent the ten questions from the CASP checklist which we used to assess the quality of each study. Yes (Y) and No (N) address if and if not each of the studies lived up to the quality question.

Table 5. Quality assessment of included studies, Q1 – Q10 illustrates the ten questions included in CASP, Y (Yes) N (No).

Findings

Identification and classification of studies

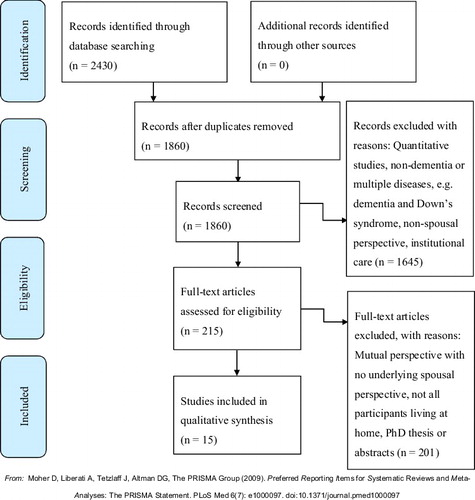

The systematic search produced 2,430 hits, of which 570 were duplicates (). 1,860 studies were screened first by title and abstract, resulting in exclusion of 1,645 studies which did not live up to the inclusion criteria. Full-text reading of 215 articles was carried out; 200 of those articles were excluded. Fifteen studies lived up to the inclusion criteria.

Characteristics of included studies

Country of included studies

Five of the studies were conducted in Sweden, four in the UK, three in the USA, one in Canada, one in Denmark and one in South Africa ().

Aim of included studies

The included studies aimed at examining experiences and management in relation to family and spouses together (n = 3), aspects of everyday life (n = 4), experiences in relation to trajectory (n = 3), experice of early stages of dementia (n = 1), non-specific types of dementia (n = 2) and specific types of dementia, including frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and Alzheimer's Disease (AD) (n = 2) ().

Methods of included studies

The qualitative approaches used were: individual interviews (n = 13), exploratory focus group interviews (n = 1) and participant observation (n = 1). Four explicitly stated that they used a qualitative design, and one used phenomenological principles. Four used a phenomenological approach, three studies used grounded theory and one used a narrative approach. The sample sizes ranged from two to 34 participants, giving a total of 221 spousal participants. One of the 15 studies did not specify gender (Bergman, Graff, Eriksdotter, Fugl-Meyer, & Schuster, Citation2016), but of those who did, 118 subjects were females and 93 were males. Six studies reported the duration of the disease, varying from one month to 10 years; two studies reported on dementia in its early stages; one study reported on mild-to-moderate dementia; one reported on mid-stage dementia and five studies did not report the stage of dementia ().

Data analysis of included studies

Nine of the 15 studies specified the analytical strategy; three studies used interpretative phenomenological analysis, one study used phenomenological-hermeneutic analysis, two studies used thematic analysis, two studies used constant comparative analysis, one study used theoretical deductive analysis and six studies did not report the analytical strategy used ().

Results from the thematic analysis

Three themes derived from the analysis: 1) Noticing changes in everyday life 2) Transformation to a new marital relation in everyday life 3) Planning the future ().

Table 6. Thematic analysis.

Theme 1. Noticing changes and management of noticed changes in everyday life

Two of the included studies examined aspects related to time between pre-diagnosis and actual diagnoses, including noticed changes and management of noticed changes in everyday life ().

Spouses noticed various changes in their partners’ everyday lives in relation to pre-diagnosis and diagnosis. Spouses experienced that they had to adjust to their new life situation by trying different strategies to manage their new everyday life, dependent on the extent to which dementia had progressed.

Spouses experienced some changes in their partners’ behaviour and personality (Ducharme, Kergoat, Antoine, Pasquier, & Coulombe, Citation2013; Quinn, Clare, Pearce, & van Dijkhuizen, Citation2008). Nevertheless, spouses sought alternative explanations for their partners’ unusual behaviour, such as stress, depression or workload (Ducharme et al., Citation2013); but when the diagnosis was disclosed, it was experienced as a relief and as an explanation of the irregular behaviour; but it was otherwise linked to uncertainties about future life changes (Ducharme et al., Citation2013; Quinn et al., Citation2008). Disclosure of the diagnosis gave rise to a difficult situation, often accompanied by a transitional period of shock. Spouses tended to downplay their partners’ problems in the beginning, and denied the fact that their partners had dementia and were unwilling to accept the diagnosis (Quinn et al., Citation2008).

Spouses tried to manage the disclosure by apprehending their circumstances and trying to understand aspects of the disease (Ducharme et al., Citation2013). Spouses tried to normalise their circumstances while at the same time acknolweding the need to accept the diagnosis and manage the situation; and they tried to stay independent but realised a needed to stay more at home; they gave up activities and interests and felt isolated from friends and family (Quinn et al., Citation2008).

Different strategies were used in spouses’ ways of communicating, and in their ways of seeking support from their partner in order to cope the condition. Some found it important to communicate about the condition, others found it pointless as their partners kept forgetting what they had just talked about (Quinn et al., Citation2008). Some spouses were in doubt of their partner's understating of his or her condition, while others spouses felt that their partners were unwilling to talk about the condition (Quinn et al., Citation2008).

Support from close relations was sought in different ways. Some spouses found it difficult to share the diagnosis with others because of taboo and stigma associated with the disease, leading to the perception that it was a marital concern only (Ducharme et al., Citation2013). Some spouses sought isolation as they feared not being understood by their closest relations (Ducharme et al., Citation2013). Other spouses found it beneficial to talk to friends and joining the Alzheimer's Society, as it helped them understand dementia and proved supportive as mutual experiences were shared (Quinn et al., Citation2008).

Theme 2. Transformation of marital relation in everyday life

Two subthemes were related to transformation of marital relation in everyday life; (1) changes in marital relationship, (2) management of the transitioned marital relation in everyday life.

Subtheme 1: changes in marital relationship

Spouses experienced dramatic changes in their marital relation due to the many changes that appeared. The main issues were changes in marital roles, changes in everyday activities and emotional reactions. These issues appear to be inter-related.

Spouses experienced changes in their marital relationships due to changed roles, and as a consequence of their partners being unable to perform tasks as before (Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012; Ducharme et al., Citation2013; Fjellström et al., Citation2010; Massimo, Evans, & Benner, Citation2013; O'Shaughnessy, Lee, & Lintern, Citation2010; Quinn et al., Citation2008; Vikström, Josephsson, Stigsdotter-Neely, & Nygard, Citation2008). Overall, spouses experienced both mental and practical effects as a result of increased responsibility and more duties and worries (Bergman et al., Citation2016). In addition, male spouses experienced a shift in roles from sharing a mutual relationship to a changed relationship where practicalities were in focus as dementia progressed (Hellström, Håkanson, Eriksson, & Sandberg, Citation2017).

In everyday activities, spouses took greater responsibility and assumed a greater number of household chores, leading to changed roles (Boyle, Citation2013; Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012; Lin, Macmillan, & Brown, Citation2012; Quinn et al., Citation2008; Vikström et al., Citation2008). Some felt empowered and more dominant due to increased responsibility and decision-making (Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012; Quinn et al., Citation2008). Others found it difficult to assume responsibility and adjust to the new role (Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012; Quinn et al., Citation2008). Some spouses were able to maintain some degree of collaboration and assistance (Vikström et al., Citation2008). Spouses who previously had worked together on household chores felt lonely, especially when it was difficult to include their partner (Fjellström et al., Citation2010). The changed role from spouse to caregiver was frustrating for some (Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012), especially as the caregiver role became increasingly dominant (Ducharme et al., Citation2013). Even though spouses spent more time together in their day-to-day lives, the condition negatively affected their mutual engagement in everyday activities (Vikström et al., Citation2008). Spouses longed to spend time on their own (Bergman et al., Citation2016; Vikström et al., Citation2008), and frustrations influenced their mood which, in turn, affected their partners (Vikström et al., Citation2008).

Emotional reactions occurred due to changes and loss in marital identity, loss in intimacy and the changes within the relationship (Bergman et al., Citation2016; Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012; Madsen & Birkelund, Citation2013; Massimo et al., Citation2013). Spouses experienced loss of shared meanings, roles and connection to their spouses (Massimo et al., Citation2013). This resulted in a progressive diminution of adult interaction where meaningful communication became impossible (Hellström et al., Citation2017), and lack of meaningful communication led to a loss of intimacy (Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012; Massimo et al., Citation2013; Quinn et al., Citation2008). This was a major stressor as spouses longed to have meaningful communication (Pretorius et al., Citation2009). The loss of meaningful communicating was difficult for spouses who needed intimacy (Bergman et al., Citation2016). Losing meaningful aspects in everyday life led to isolation and separation (Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012; Pretorius et al., Citation2009; Quinn et al., Citation2008). Despite having a wordless relationship, some, however, found a kind of intimacy (Bergman et al., Citation2016).

In addition to losing marital relationships, spouses experienced a dichotomy when trying to meet their own needs and those of their partners, experiencing self-criticism and guilt, at the same time as feeling deep empathy for their partners (O'Shaughnessy et al., Citation2010). Spouses felt a sense of powerlessness and lack of control over the course of the illness and its consequences for their relationship (O'Shaughnessy et al., Citation2010). Especially male spouses were affected negatively due to a feeling of detachment from their social network which generally did not understand the illness (Madsen & Birkelund, Citation2013). Female spouses considered themselves evil when their living circumstances became so challenging that they wished that their partners had died (Madsen & Birkelund, Citation2013).

Subtheme 2: management of the transformed marital relation in everyday life

In the face of the dramatic changes in their marital relationship, spouses actively sought alternatives strategies. The strategies used were: attempts to sustain couplehood, reconstructing marital closeness, developing practical and emotional management strategies and seeking support.

Spouses worked to sustain couplehood and reconstruct marital closeness (Bergman et al., Citation2016; Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012; Hellström, Nolan, & Lundh, Citation2007; Lin et al., Citation2012). They tried to sustain their marital relationship by letting their partner continue with social and household chores (Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012), thereby distancing their marriage from the illness as a way of reconstructing their marriage (Hellström et al., Citation2007). Spouses attempted to sustain their marital relationship by adding value and joy to elements of their everyday lives, focusing on former rituals or routines (Hellström et al., Citation2007). Spouses also tried to prevent and manage potential conflict situations and helped their partner look on the bright side (Hellström et al., Citation2007). Marital relationships were sustained using humour and by avoiding tense or serious situations, which, in turn, required a tremendous amount of patience (Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012). Spouses tried to maintain an open, two-way communication in order to maintain couplehood (Hellström et al., Citation2007).

Sustaining and reconstructing their marital relationship had an impact on how spouses looked at themselves in their role as spouse or caregiver. Maintaining marital closeness helped them frame their role as a helper where caregiving became part of their marital relationship (Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012). If spouses did not successfully reconstruct marital closeness, providing care for their partner became unwanted and was a devastating experience (Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012).

Practical and emotional strategies helped spouses create a sense of control over their circumstances, their emotional responses to the changes in their marital relationship and their own sense of self (O'Shaughnessy et al., Citation2010).

On a practical level, spouses adjusted to their new circumstances by lowering their demands on their partner, themselves and their mutual engagement, and things were kept uncomplicated (Bergman et al., Citation2016; Quinn et al., Citation2008; Vikström et al., Citation2008).

Some balanced between encouraging initiatives from their partner and taking over chores (Quinn et al., Citation2008; Vikström et al., Citation2008), while others developed collaborative management, working together or side-by-side on different chores (Vikström et al., Citation2008). Some partners who previously had habituated chores were still able to manage their situation (Boyle, Citation2013). Others experienced that it became necessary to take over all of their partners’ previous responsibilities and chores (Boyle, Citation2013; Quinn et al., Citation2008) and experienced it as challenging (Quinn et al., Citation2008); some spouses learned new chores by taking housechores classes (Fjellström et al., Citation2010).

Spouses actively sought support by participating in support groups or research studies (Shim et al., Citation2013). Male spouses in South Africa could see their potential value, but opted not to join support groups due to a presumption about their predominantly female composition and emotionally expressive climate (Pretorius et al., Citation2009). On the other hand, male spouses in South Africa viewed their daughters and/or housekeeper as more accessible and dependable sources (Pretorius et al., Citation2009).

Emotionally, spouses approached their new living circumstances by changing their attitudes (Bergman et al., Citation2016), choosing a positive attitude and accepting their situation (Shim et al., Citation2013). Frustrations were managed by trying to understand their partner's behaviour (Massimo et al., Citation2013). Male spouses approached caregiving in a problem-focused, cognitive way (Pretorius et al., Citation2009). Spouses tried to provide care to keep their partner as healthy as possible (Fjellström et al., Citation2010), and some experienced personal growth in putting another human being's needs before their own (Shim et al., Citation2013). Especially male spouses experienced taking over chores as positive, as it released a feeling of control over the situation (Pretorius et al., Citation2009), as well as pride as new household chores were learned (Hellström et al., Citation2017). On the other hand, female spouses felt they were evil when forced to initiate changes such as institutionalising their partner (Madsen & Birkelund, Citation2013).

Theme 3: Re-planning and planning the future

Spouses’ emotional management strategis included not thinking about the future, re-planning and planning the future.

Spouses created new meanings and self-understandings, and changed their expectations about the future (Massimo et al., Citation2013). Even so, they experienced s dichotomy between acceptance and realism about what the future would hold, e.g. uncertainty related to the duration and progression of the disease and how to manage to live with it (Hellström et al., Citation2017; O'Shaughnessy et al., Citation2010).

Spouses experienced that to cope emotionally they needed to have a shorter time horizon and to live in the present moment (Hellström et al., Citation2007, Citation2017; O'Shaughnessy et al., Citation2010). These strategies as well as simple denial helped them cope with their overwhelming fear of the future (O'Shaughnessy et al., Citation2010). Denial consisted in the couples distancing themselves from the disease and trying to live from day to day to reduce anxiety (Hellström et al., Citation2017). Focusing on the present moment, doing the best they could and staying positive (Hellström et al., Citation2007; Pretorius et al., Citation2009; Quinn et al., Citation2008) helped when the future was experienced as depressing (Hellström et al., Citation2017). Male spouses focused on immediate changes rather than potential changes (Pretorius et al., Citation2009), and manged by distancing the illness from their partner (Hellström et al., Citation2007). However, spouses acknowledged that it was difficult to make longer-term plans, and described how the future seemed uncertain and unpredictable (Ducharme et al., Citation2013; Hellström et al., Citation2017). Being faced with not having a future together as a couple was experienced as a heavy burden (Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify and synthesise previous qualitative studies on what characterises spouses’ experiences of living with a partner diagnosed with dementia, and how changes in everyday life are managed.

The findings provide an overview of previous qualitative studies on spouses’ lived experiences, of the changes and management of these changes in everyday life when living with a person with dementia. The findings show how spouses struggle with practical and emotional challenges in their everyday lives due to their partner's progressive dementia. The findings highlight how changes and new management startegies are used across the entire time span from pre-diagnosis through the mid-stages of progressing dementia to the time of thoughts about the couple's future. The findings further show how in various ways spouses have to adjust to changes in everyday life at various phases in the progression of dementia.

Findings to our those presented in study have been found in previous reviews of spouses’ lived experiences, particularly relating to changes in marital relationships and loss (Evans & Lee, Citation2014; Pozzebon et al., Citation2016). Evans and Lee's (Citation2014) found that changes are related to loss of companionship and reciprocity. Over time, the husband-and-wife relationship changes to a caregiver-recipient relationship (Evans & Lee, Citation2014). Similar to our findings, findings from the study by Evans & Lee, Citation2014 show how changes in the marital relationship are dependent on the partners’ roles prior to the onset of dementia. Previous findings show that loss was experienced as a result of changes due to the partner's personality and the lack of communication skills (Evans & Lee, Citation2014; Pozzebon et al., Citation2016). In our study, loss in meaningful communication, marital identity and intimacy led to isolation of the spouses.

The identified themes related to spouses’ management of changes show how they struggle to manage both practical and emotional changes as they seek to sustain or reconstruct their marital relationships. Wadham et al. (Citation2016) found that a strong connection between couples seemed to have an impact on how they managed the changes related to identity issues, power struggles, fear and distress (Wadham et al., Citation2016). Our study shows that spouses try to sustain or reconstruct couplehood by preventing potential conflicts and allowing their partner to maintain household chores and by adding joy and value to their everyday life and trying to maintain former rituals and routines. However, due to prevention of loneliness, some turned to friends for support and became involved in the Alzheimer's Society.

The present study contributes to existing literature by showing how spouses experience changes and mange these changes across the entire dementia disease trajectory. The identified changes can be understood in the light of Birte Bech-Jørgensen's concept of unnoticed changes in everyday life. Before receiving the diagnosis of dementia, changes in everyday life seem to be managed by unnoticed adjustments. However, over time, changes are noticed (Bech-Jørgensen, Citation1994). In the beginning, habits and routines are sustained as far as possible, but when changes in everyday life are unavoidable, people try to create new meaning in their lives and reconstruct everyday life (Bech-Jørgensen, Citation1994). In our to findings, changes in everyday circumstances were related to former roles, routines and habits were influenced by the progression of dementia and the spouses’ ability to reconstruct their marital relationship. Reluctantly, spouses had to let go of trying to sustain their former marital relationship and had to seek support elsewhere, creating a new identity and independence. Lay representatives in the panel that we consulted during our study supported the idea of intervention in the early stages, as participants often were not aware of the changes until it was too late. As supported by the panel, interventions in the early stages could have helped them discern unnoticed changes and support them in sustaining and reconstructing the relationship, if needed.

Our review is in line with previous review on spouses’ experiences of having to change their marital roles. The findings of the present review highlight the need to keep exploring spouses’ and couples’ experiences of everyday challenges when living with a person with dementia, particularly in relation to its progression. Future studies need to focus more on developing early interventions that help couples manage and address the sometimes overwhelming changes in their everyday lives and hopefully prevent major crises in marital relationship.

Strengths and limitations

Our study followed JBI review guidelines, which helped support the identification of relevant literature (Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2014). The first author has been in dialogue with a librarian with expertise in search strategies in order to qualify the search. The first author has also been in dialogue with lay representatives discussing findings which, according to JBI, strengthens and helps to qualify the review (Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2014), and helped us be reflective about our preunderstanding of what is important to investigate. The use of PICo helped structure the search and helped in identifying relevant qualitative studies by structuring the search in relation to the three key aspects Population (P), Phenomena of Interest (I) and Context (Co).

According to JBI, the timeframe for a literature search can be limited, but may exclude relevant literature (Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2014). Studies before 2007 were not included. Using a methodological filter can be a limit as well as strength. Results from quantitative studies could have complemented the qualitative studies. According to Joanna Briggs, including a range of different methodological studies in order to capture the phenomenon of interest is advantageous. Our aim was to identify spouses’ lived experiences, which calls for the inclusion of qualitative studies only. When it comes to capturing the different stages in the disease trajectory, not all of the included studies reported the stages of the partner's dementia. This means that the identified themes might not only cover mild-to-moderate dementia, which could affect the conclusion and transferability of the findings. Furthermore, couples of same sex are excluded, and the conclusions presented in this systematic review therefore pertain only to different-gender couples. Articles with low quality were not excluded, which is a limitation. Variation in the various contexts, cultures and countries and spouses’ characteristics can inspire healthcare services to develop spouse and dyad interventions whose aim is to support people in managing everyday life with dementia.

Conclusion

This review identifies previous studies on spouses’ lived experiences of living with a person with dementia. The findings offer a deeper understanding of spouses’ experiences of marital changes and management of these changes as they occurs over time, and it contribute with knowledge on spouses’ experiences of changes in the early stages of dementia. Furthermore, the present study identifies themes of importance that not only relate to spouses’ experiences of changes in marital relationship but also to how these changes are managed in everyday life over time and while the partner is still living at home. The identified themes can help healthcare service providers achieve a better understanding of spouses’ lived experiences, and they provide directions for future supportive interventions targeting not only the person with dementia but also the spouse. These interventions could help support spouses manage everyday challenges and if possible ease the burden involved.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mette Buje Grundsøe, MLISc, Aalborg University Library, for specialised knowledge and support regarding the systematic search for this review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, A. P., Curran, E. A., Duggan, Á., Cryan, J. F., Chorcoráin, A. N., Dinan, T. G., … Clarke, G. (2017). A systematic review of the psychobiological burden of informal caregiving for patients with dementia: Focus on cognitive and biological markers of chronic stress. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 73, 123–164. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.006

- Bech-Jørgensen, B. (1994). Når hver dag bliver hverdag [When every day becomes everyday]. København [Copenhagen]: Akademisk forlag [Academic Publisher].

- Bergman, M., Graff, C., Eriksdotter, M., Fugl-Meyer, K. S., & Schuster, M. (2016). The Meaning of Living Close to a Person with Alzheimer Disease. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy: A European Journal, 19(3), 341–349. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-016-9696-3

- Boyle, G. (2013). “She's usually quicker than the calculator’: Financial management and decision-making in couples living with dementia. Health & Social Care in the Community. Boyle, Geraldine: Centre for Applied Social Research, University of Bradford, Ashfield Building, Bradford, United Kingdom, BD7 1DP, [email protected]: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12044

- Boylstein, C., & Hayes, J. (2012). Reconstructing Marital Closeness While Caring for a Spouse With Alzheimer's. Journal of Family Issues, 33(5), 584–612. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11416449

- Chan, D., Livingston, G., Jones, L., & Sampson, E. L. (2013). Grief reactions in dementia carers: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(1), 1–17. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1002/gps.3795

- Chiao, C.-Y., Wu, H.-S., & Hsiao, C.-Y. (2015). Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: A systematic review. International Nursing Review, 62(3), 340–350. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12194

- Critical Appraisal Skills Program. (2017). CASP qualitative research checklist. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1980.tb10232.x

- Dam, A. E. H., De Vugt, M. E., Klinkenberg, I. P. M., Verhey, F. R. J., & Van Boxtel, M. P. J. (2016). A systematic review of social support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia: Are they doing what they promise ? Maturitas, 85, 117–130. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.12.008

- Ducharme, F., Kergoat, M.-J., Antoine, P., Pasquier, F., & Coulombe, R. (2013). The unique experience of spouses in early-onset dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias, 28(6), 634–641. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1177/1533317513494443

- Evans, D., & Lee, E. (2014). Impact of dementia on marriage: A qualitative systematic review. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice. Evans, David: School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of South Australia, GPO Box 2471, Adelaide, SA, Australia, 5001, [email protected]: Sage Publications. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1177/1471301212473882

- Fjellström, C., Starkenberg, Å., Wesslén, A., Licentiate, M. S., Tysén Bäckström, A.-C., & Faxén-Irving, G. (2010). To be a good food provider: An exploratory study among spouses of persons with Alzheimer's disease. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias, 25(6), 521–526. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1177/1533317510377171

- Garrard, J. (2007). Health sciences literature review made easy: The matrix method (Second). Sudburry, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

- Gilhooly, K. J., Gilhooly, M. L. M., Sullivan, M. P., McIntyre, A., Wilson, L., Harding, E., … Crutch, S. (2016). A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatrics, 16(1), 1–8. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0280-8

- Glanville, J., Bayliss, S., Booth, A., Dundar, Y., Fernandes, H., Fleeman, N. D., … Welch, K. (2008). So many filters, so little time: The development of a search filter appraisal checklist. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA, 96(4), 356–361. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.96.4.011

- Hellström, I., Håkanson, C., Eriksson, H., & Sandberg, J. (2017). Development of older men's caregiving roles for wives with dementia. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12419

- Hellström, I., Nolan, M., & Lundh, U. (2007). Sustaining ‘couplehood’: Spouses’ strategies for living positively with dementia. Dementia, 6(3), 383–409. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1177/1471301207081571

- Huis in het Veld, J. G., Verkaik, R., Mistiaen, P., van Meijel, B., & Francke, A. L. (2015). The effectiveness of interventions in supporting self-management of informal caregivers of people with dementia; a systematic meta review. BMC Geriatrics, 15(1), 147. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0145-6

- Jensen, M., Agbata, I. N., Canavan, M., & McCarthy, G. (2015). Effectiveness of educational interventions for informal caregivers of individuals with dementia residing in the community: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(2), 130–143. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4208

- Joanna Briggs Institute. (2014). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2014 edition. South Australia: Joanna Briggs Institute. Retrieved fromwww.joannabriggs.org

- Letts, L., Edwards, M., Berenyi, J., Moros, K., O'Neill, C., O'Toole, C., & McGrath, C. (2011). Using occupations to improve quality of life, Health and wellness, and client and caregiver satisfaction for people with alzheimer's disease and related dementias. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(5), 497–504. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2011.002584

- Li, R., Cooper, C., Austin, A., & Livingston, G. (2013). Do changes in coping style explain the effectiveness of interventions for psychological morbidity in family carers of people with dementia? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Psychogeriatr, 25(2), 204–214. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610212001755

- Lin, M.-C. M.-C., Macmillan, M., & Brown, N. (2012). A grounded theory longitudinal study of carers’ experiences of caring for people with dementia. Dementia (14713012), 11(2), 181–197. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1177/1471301211421362

- Madsen, R., & Birkelund, R. (2013). “The path through the unknown”: The experience of being a relative of a dementia-suffering spouse or parent. Journal of Clinical Nursing. Madsen, Rikke: Institute of Public Health, Aarhus University, Sundvej 30, Horsens, Denmark, 8700, [email protected]: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12131

- Massimo, L., Evans, L. K., & Benner, P. (2013). Caring for loved ones with frontotemporal degeneration: The lived experiences of spouses. Geriatric Nursing, 34(4), 302–306. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2013.05.001

- National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) AARP Public Policy Institute. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. 2015, Montgomery Lane: National Alliance for caregiving (NAC).

- O'Shaughnessy, M., Lee, K., & Lintern, T. (2010). Changes in the couple relationship in dementia care: Spouse carers’ experiences. Dementia, 9(2), 237–258. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1177/1471301209354021

- Ornstein, K., & Gaugler, J. E. (2012). The problem with “problem behaviors”: A systematic review of the association between individual patient behavioral and psychological symptoms and caregiver depression and burden within the dementia patient–caregiver dyad. International Psychogeriatrics, 24(10), 1536–1552. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610212000737

- Parker, D., Mills, S., & Abbey, J. (2008). Effectiveness of interventions that assist caregivers to support people with dementia living in the community: A systematic review. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 6(2), 137–172. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-6988.2008.00090.x

- Pozzebon, M., Douglas, J., & Ames, D. (2016). Spouses’ experience of living with a partner diagnosed with a dementia: A synthesis of the qualitative research. International Psychogeriatrics / IPA, 28(4), 537–556. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610215002239

- Pretorius, C., Walker, S., & Heyns, P. M. (2009). Sense of coherence amongst male caregivers in dementia. Dementia, 8(1), 79–94. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1177/1471301208099046

- Quinn, C., Clare, L., Pearce, A., & van Dijkhuizen, M. (2008). The experience of providing care in the early stages of dementia: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Aging & Mental Health, 12(6), 769–778. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1080/13607860802380623

- Quinn, C., Clare, L., & Woods, B. (2009). The impact of the quality of relationship on the experiences and wellbeing of caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Aging & Mental Health, 13(2), 143–154. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1080/13607860802459799

- Saini, M., & Shlonsky, A. (2012). Systematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sansoni, J., Anderson, K. H., Varona, L. M., & Varela, G. (2013). Caregivers of Alzheimer's patients and factors influencing institutionalization of loved ones: Some considerations on existing literature. Annali Di Igiene : Medicina Preventiva E Di Comunità, 25(3), 235–246. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.7416/ai.2013.1926

- Shim, B., Barroso, J., Gilliss, C. L., & Davis, L. L. (2013). Finding meaning in caring for a spouse with dementia. Applied Nursing Research, 26(3), 121–126. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/1016/j.apnr.2013.05.001

- Sundheds- og Ældreministeriet [The Ministry of Health]. (2016). Et trygt og værdigt liv med demens [A happy and dignified life with dementia]. København [Copenhagen]: Sundheds- og Ældreministeriet [The Ministry of Health]. Retrieved fromhttp://www.sum.dk/Aktuelt/Publikationer/∼/media/Filer-Publikationer_i_pdf/2016/Demenshandlingsplan-2025-PUB-sept-2016/Handlingsplan-V2.ashx

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Vandepitte, S., Van Den Noortgate, N., Putman, K., Verhaeghe, S., Faes, K., & Annemans, L. (2016). Effectiveness of Supporting Informal Caregivers of People with Dementia: A Systematic Review of Randomized and Non-Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 52(3), 929–965. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-151011

- Vikström, S., Josephsson, S., Stigsdotter-Neely, A., & Nygard, L. (2008). Engagement in activities: Experiences of persons with dementia and their caregiving spouses. Dementia, 7(2), 251–270. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1177/1471301208091164

- Wadham, O., Simpson, J., Rust, J., & Murray, C. (2016). Couples’ shared experiences of dementia: A meta-synthesis of the impact upon relationships and couplehood. Aging & Mental Health, 20(5), 463–473. Retrieved fromhttp://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1023769

- World health Organization. (2012). Dementia: A public health priority. World Health Organisation. Geneva 27: World Health Organization. Retrieved fromhttp://site.ebrary.com/lib/librarytitles/docDetail.action?docID=10718026