Abstract

Objectives: The retirement transition is a multidimensional and dynamic process of adjustment to new life circumstances. Research has shown that individual differences in resource capability accounts for a substantial amount of the previously observed heterogeneity in retirement adjustment. The aim of the present study was to investigate interaction effects of self-esteem, autonomy, social support, self-rated physical health, self-rated cognitive ability, and basic financial resources on levels and changes in life satisfaction in the retirement transition.

Method: Our sample included 1924 older adults from the longitudinal population-based HEalth, Ageing, and Retirement Transitions in Sweden (HEARTS) study. The participants were assessed annually over a three-year period, covering the transition from work to retirement (n = 614). Participants continuously working (n = 1310) were included as a reference group.

Results: Results from latent growth curve models showed that the relationship between a particular resource and levels and changes in life satisfaction varied depending on other available resources, but also that these effects varied between retirees and workers. Autonomy moderated the effect of physical resources, and social support and perceived cognitive ability moderated the effect of financial resources.

Discussion: Our findings add to the current knowledge on retirement adjustment and suggest that negative effects of poor health and lack of basic financial resources on retirees life satisfaction may be compensated for by higher levels of autonomy, social support, and perceived cognitive ability.

Retirement from work is a major life transition in older adulthood and involves a behavioral as well as a psychological workforce withdrawal (Wang & Shi, Citation2014). Retirement adjustment refers to the process of adaptation to changes associated with the transition (van Solinge & Henkens, Citation2008) and can be defined as the individual’s psychological comfort with life in retirement (Wang, Henkens, & van Solinge, Citation2011). Recent reviews of the impact of retirement (e.g. Henning, Lindwall, & Johansson, Citation2016) suggest that, for the majority, retirement has a limited influence on well-being. Nevertheless, a considerable body of research indicates that the impact may differ both between and within individuals over time (Schaap, de Wind, Coenen, Proper, & Boot, Citation2017; van Solinge, Citation2013). Several longitudinal studies (Heybroek, Haynes, & Baxter, Citation2015; Muratore, Earl, & Collins, Citation2014; Pinquart & Schindler, Citation2007; Wang, Citation2007) report heterogeneous effects of retirement and that a significant proportion of older workers have problems adjusting to becoming a retiree. In this study, we contribute to the current knowledge on retirement adjustment by investigating factors related to individual differences in subjective well-being in the retirement transition. More specifically, we study levels and changes in life satisfaction, defined as a person’s global cognitive evaluation of satisfaction with life as a whole (Diener, Citation1984), and how individual differences in resource capability can contribute to explain the previously observed heterogeneity in retirement adjustment.

The resource-based dynamic model (Wang et al., Citation2011) is an integrative theoretical framework designed to address both the impact of retirement and the underlying mechanisms of that impact. In contrast to other theories (e.g. role theory, continuity theory, and stage theory), it has the potential to account for both within- and between-person differences in retirement adjustment. The model is based on the idea that resources, i.e. emotional, motivational, social, physical, cognitive, and financial aspects of an individual’s total resource capability, are valuable assets in the adjustment process because they define the conditions of retirement and influence not only what people can do physically and mentally, but also what they can afford financially, in retirement. Individuals with limited resources are assumed to have more difficulties maintaining their pre-retirement lifestyle and taking up new activities in retirement. More resources are thus expected to lead to fewer adjustment problems and greater well-being.

The applicability of a resource perspective to the study of retirement adjustment has received considerable support (see Barbosa, Monteiro, & Murta, Citation2016, in a recent review). However, most previous research have focused on only a select and limited set of resources, and mainly on the impacts of health and wealth. Measures of physical health and financial assets were found to correlate with direct (e.g. retirement satisfaction) or indirect (e.g. life satisfaction) indicators of retirement adjustment in about 80% of the 115 studies reviewed by Barbosa et al. (Citation2016), and people with poor health and financial problems were more likely to experience problems in adjustment to retirement (e.g. Earl, Gerrans, & Halim, Citation2015; Kim & Moen, Citation2002; Muratore & Earl, Citation2015). Psychological and social resources have been studied less frequently and relatively few studies have investigated how emotional, motivational, social, and cognitive resources may contribute to explain heterogeneity in retirement adjustment. Although factors such as autonomy, self-esteem, social support, and self-rated cognitive ability have previously been linked to well-being in retirement (e.g. Hansson, Buratti, Thorvaldsson, Johansson, & Berg, Citation2017), there is still a lack of research on psychological resources relative to those focusing on more material resources.

More in-depth studies on the role of psychological resources can contribute with important insights into the adjustment process because they are likely to influence how a person reacts to and copes with changes associated with the transition. For instance, research has shown that, when constructs like autonomy (Hansson et al., Citation2017) and personal control or mastery (Donaldson, Earl, & Muratore, Citation2010; Price & Balaswamy, Citation2009) are included, they tend to exceed the effects of health and economy. In order to evaluate the role of a particular resource relative to others, it is necessary to include them all in the same model. However, remarkably few previous studies have included all six resource domains (i.e. emotional, motivational, social, physical, cognitive, and financial) suggested in the resource-based dynamic model. To our knowledge, only four studies (i.e. Hansson et al., Citation2017; Leung & Earl, Citation2012; Yeung, Citation2017; Yeung & Zhou, Citation2017) have investigated the role of all six resource domains in retirement adjustment, but the findings in these studies are inconsistent. One potential explanation for this inconsistency is the mismatch in the specific constructs that are studied as well as the methods used for data collection and analysis. In addition to this, there may also be important cultural differences between the samples. More research on the relative importance of different types of resources in the retirement adjustment process is therefore needed.

One approach in studying the role of different resources is to investigate resource interdependency, i.e. the extent to which the importance of a particular resource may vary depending on other available resources. A limitation of the resource-based dynamic model is that it assumes that all resources are equally valued for all individuals and that changes in these resources have the same impact on all retirees. Although Wang et al. (Citation2011) acknowledge that resource loss can be compensated by gains in other resource domains, the model does not account for heterogeneity in the effects of different types of resources relative to each other. For instance, negative effects of poor health and economy may be less detrimental for those who experience a sense of control over their lives and/or have supportive social relations. In other words, an improved understanding of the dynamics of retirement adjustment requires an investigation of how various resources are related to each other.

We know of only one study that investigated the interdependency of resources in retirement adjustment. In this study, Zaniboni (Citation2015) examined the interaction between personal resources and age discrimination in the workplace (as an indicator of social resources) and their influence on desired retirement age and expected future retirement adjustment among older workers. The results showed that personal resources were associated with the selected outcomes only among individuals with low perceived age discrimination. However, Zaniboni made no distinction between different types of psychological resources as suggested in the model by Wang et al. (Citation2011), and the study was conducted using only a limited subset of the resource domains specified in the model. An additional limitation was that the outcome measure was related to an expected future adjustment rather than to a person’s current comfort in retirement. A more systematic approach in evaluating sources of resource interdependency in the retirement transition could contribute to a better understanding of the previously observed heterogeneity in retirement adjustment.

The aim of the present study was to investigate aspects of resource interdependency in retirement adjustment. In particular, we analyzed the relative importance of self-esteem, autonomy, social support, self-rated physical health, self-rated cognitive ability, and basic financial resources for levels and changes in life satisfaction in the retirement transition. The respective resource indicators were selected based on previous research on the determinants of retirement adjustment (see Barbosa et al., Citation2016 for a review) as well as more general resource theories (see e.g. Hobfoll, Citation2002). Based on the idea that resource loss can be compensated for by gains in other resources (Hobfoll, Citation2002; Wang et al., Citation2011), we hypothesized that the importance of a particular resource varies depending on other available resources and more specifically that the association with life satisfaction would be stronger in absence of other resources (i.e. negative interaction effect). Based on previous research on the determinants of retirement adjustment (e.g. Donaldson et al., Citation2010; Hansson et al., Citation2017; Price & Balaswamy, Citation2009), we anticipated that psychological resources are of particular importance in the adjustment process and that they can contribute to compensate for negative effects of poor health and limited financial resources (i.e. moderating effect of psychological resources). Building on the findings by Zaniboni (Citation2015), we additionally anticipated that psychological resources are more important in the presence of adequate social resources (i.e. moderating effect of social resources). Due to the lack of previous research within the area, we made no specific assumptions about other potential interaction patterns.

Method

Sample and procedure

We used data from the first three waves of the HEalth, Ageing and Retirement Transitions in Sweden (HEARTS) study, a longitudinal population-based study aimed to capture developmental psychological processes in the years before and after the retirement transition (Lindwall et al., Citation2017). A nationally representative sample of 14,990 individuals aged 60–66 were invited to participate in the study and asked to complete a survey including questions about their socio-demographic background, work life and retirement, health, lifestyle, well-being, social relations, and personality. In total, 5913 individuals (39.4%) participated in the first measurement wave (T1) in spring 2015. The second measurement wave (T2) was collected in the spring 2016, resulting in a retention rate of 78.7% (N = 4651), and the third measurement (T3) was assessed in spring 2017, this time 73.1% (N = 4320) of the baseline sample completed the questionnaire.

We included participants who retired between the first and third measurement occasion as well as those continuously working across the three waves. Retirement status was assessed at each measurement occasion through the question ‘Are you retired (receive old-age pension)?’ with the following response alternatives: (1) no, (2) yes, but still working and consider myself a worker, (3) yes, still working but consider myself a retiree, and (4) yes, full-time retiree. Participants were included if they reported being not yet retired at baseline (T1; n = 3792), and still not retired (n = 1468) or fully retired (n = 767) at the third measurement occasion 2 years later (T3). Participants who were retired but still working in the third wave (n = 522) were excluded from the analyses, i.e. retirement was defined as full-time retirement. Participants continuously not retired were included to facilitate differentiation between age- and retirement-related mechanisms. To avoid potential confounding effects of indirect retirement (i.e. retirement from unemployment; Wetzel, Huxhold, & Tesch-Römer, Citation2015), we excluded participants who were not engaged in the labor-forced market at T1 (n = 311). The final sample consisted of 1924 individuals with a mean age of 62.02 years (SD = 1.65), 55% of these were women, and 47% had tertiary/higher education. Little less than one third of the sample (32%; n = 614) retired during the study period, and 68% (n = 1310) were continuously working in all three waves. The majority (91%) of the participants completed the questionnaire in all three measurement occasions, 44% (n = 251) of the retirees retired between T1 and T2, and additionally 12% (n = 67) reported that they were partially retired (i.e. working in retirement) in wave two.

Measures

Life satisfaction

Life satisfaction was measured at all three measurement occasions using the Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen & Griffin, Citation1985). The scale consists of five items (e.g. ‘I am satisfied with my life’) measured on a 7-point scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). Cronbach’s alpha was estimated to .92 at T1 and T2, and to .93 at T3.

Self-esteem

Self-esteem (as an indicator of emotional resources) was measured at T1 on the five positively phrased items (e.g. “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”) from the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (Rosenberg, Citation1965). The items were measured on a 4-point scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4), and a mean score was calculated for each participant. Cronbach’s alpha was estimated to .91.

Autonomy

Autonomy (as an indicator of motivational resources) was measured at T1 on the Autonomy subscale of the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Scale (Chen et al., Citation2015). The subscale consists of three items (e.g. ‘I feel a sense of choice and freedom in the things I undertake’) measured on a 5-point scale, ranging from completely false (1) to completely true (5). A mean score (range 1–5) was calculated for each participant. Cronbach’s alpha was estimated to .66.

Social support

Social support (as an indicator of social resources) was measured at T1 on the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, Citation1988). The scale consists of 12 items divided into three subdomains: Family (e.g. ‘I get the emotional help and support I need from my family’), Friends (e.g. ‘I can talk about my problems with my friends’), and Significant Other (e.g. ‘There is a special person who is around when I am in need’). Participants rated the items on a 7-point scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7), and a mean score (range 1–7) was calculated for each participant. Cronbach’s alpha was estimated to .95.

Self-rated physical health

Self-rated physical health (as an indicator of physical resources) was measured at T1 on one item (‘How do you currently evaluate your overall health condition?’) and estimated on a 6-point scale ranging from very bad (1) to very good (6).

Self-rated cognitive ability

Self-rated cognitive ability (as an indicator of cognitive resources) was measured at T1 on one item (‘How do you currently perceive your thinking ability?’) and estimated on a 6-point scale ranging from very bad (1) to very good (6).

Basic financial resources

Basic financial resources was measured at T1 through the participants’ estimation of their ability to cover unpredicted costs of 15,000 SEK (approx. €1500) within one week (as an indicator of financial resources). A positive response (yes, using own or household’s money) was coded as one (1) and a negative response (yes, but only with help from family or friends or no) was coded as zero (0).

Demographics

Demographic information, including age (in years), gender (0 = male, 1 = female), and education (0 = primary/secondary, 1 = tertiary/higher) was collected to control for potential confounding effects.

Statistical analysis

Levels and changes in life satisfaction across the three measurement points were estimated through latent growth curve models (see McArdle, Citation2009) using the lavaan package (Rosseel, Citation2012) in R version 3.4.4 (R Core Team, Citation2016). As a first step to establish an adequate measurement model, we generated a three-latent-factors confirmatory model of life satisfaction based on the item scores at each measurement occasion and evaluated measurement invariance over time and across the two retirement groups. We then generated two growth factors (regressed on the three latent factors of life satisfaction) in order to estimate the average levels (i.e. intercept) and changes (i.e. slope) in life satisfaction across the three measurement points. The factor loadings of the intercept were constrained to 1, and the loadings for the slope factor were fixed to 0 (for T1), 1 (for T2), and 2 (for T3).

Effects of self-esteem, autonomy, social support, self-rated physical health, self-rated cognitive ability, and basic financial resources on levels and changes in life satisfaction were analyzed separately for workers and retirees using a multi-group model. In order to provide adequate and comparable estimates of the effects, we first standardized the scores of the continuous variables (i.e. self-esteem, autonomy, social support, self-rated physical health, and self-rated cognitive ability), and then generated 15 interaction terms based on the six resources. In the first model (Model 1) we included the six resource variables as predictors of both levels and changes in life satisfaction, and in the second model (Model 2) we also included the 15 interaction variables. Age (mean centered), gender, and education were included as covariates of both levels and changes in life satisfaction, and the models were evaluated using full information maximum likelihood estimation.

Results

Descriptive statistics of the study variables are presented separately for workers and retirees in . The retirees reported higher levels of life satisfaction than the workers at all three measurement occasions. A larger proportion of the retirees had basic financial resources but no group differences were identified in self-esteem, autonomy, social support, self-rated physical health, and self-rated cognitive ability. The workers were relatively younger than the retirees, and a larger proportion of the workers also had higher education. The distribution of males and females were similar in the two groups. Bivariate correlations among the variables are shown in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for workers and retirees.

Table 2. Bivariate correlations among study variables.

The estimated measurement model of life satisfaction showed acceptable fit indices, χ2(60) = 458.06, p < .001, CFI = .985, RMSEA = .059, 90% CI [.054, .064], SRMR = .028, and the factor loadings (Δχ2(8) = 10.56, p = .23, ΔCFI < .001), the intercepts (Δχ2(8) = 14.56, p = .07, ΔCFI = .001), and the residual variances (Δχ2(10) = 18.00, p = .05, ΔCFI < .001) were found to be relatively stable across the three measurement points. The factor loadings (Δχ2(12) = 6.16, p = .91, ΔCFI < .001) and the intercepts (Δχ2(12) = 19.90, p = .07, ΔCFI < .001) were also found to be stable across the two retirement groups but the residual variances (Δχ2(15) = 39.91, p = .001, ΔCFI = .001) varied slightly. Based on these findings, we imposed strict time invariance and strong group invariance (see e.g. Meredith, 1993) in further analyzes.

The results of Model 1 are presented in , and the results of Model 2, where the interaction effects were included, are shown in . The first model showed similar results for the two retirement groups. Five of the six resources predicted levels of life satisfaction, but only one of them was associated with changes in life satisfaction across the three measurement waves. Self-esteem, autonomy, social support, self-rated physical health, and basic financial resources were associated with higher levels of life satisfaction among both workers and retirees, but no effect was observed for self-rated cognitive ability in any of the two groups. Higher autonomy was associated with a decrease in life satisfaction after two years for both workers and retirees. No effects were found for self-esteem, social support, self-rated physical health, self-rated cognitive ability, or basic financial resources on overall changes in life satisfaction in any of the groups.

Table 3. Model 1: Main effects of individual resources on levels and changes in life satisfaction.

Table 4. Model 2: Interaction effects of individual resources on levels and changes in life satisfaction.

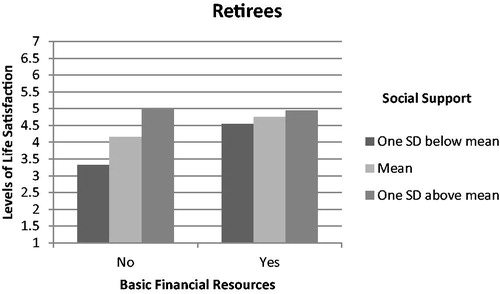

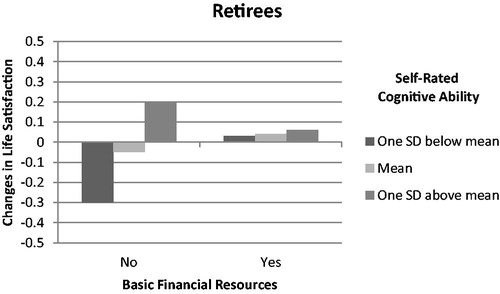

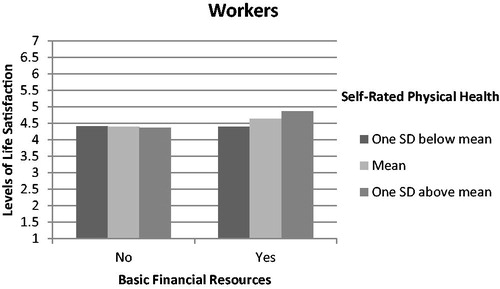

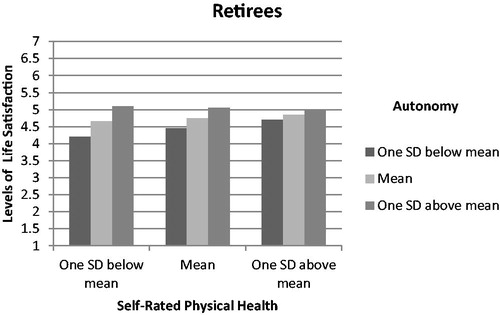

The results of the second model revealed group differences in the interactions between the six resource variables. For the workers, we found a moderating effect of perceived physical health in the relationship between basic financial resources and levels of life satisfaction, which indicates that the association was stronger among individuals with good health (see ). Three interaction effects were found for the retirees. Autonomy moderated the relationship between perceived physical health and levels of life satisfaction, suggesting that the association was stronger among retirees with low autonomy (see ). Social support moderated the relationship between financial resources and levels of life satisfaction; the association was stronger among individuals with low social support (see ). The association between financial resources and life satisfaction was additionally moderated by self-rated cognitive ability; individuals who perceived their cognitive abilities as low experienced decreases in life satisfaction in the retirement transition while those with higher cognitive ability in fact experienced increases in life satisfaction (see ). These findings suggest that negative effects of poor health and inadequate financial resources in the retirement transition can be compensated for by higher levels of autonomy, social support, and perceived cognitive ability. These effects were found to differ significantly in comparison to the effects for the workers (A × H, Δχ2(1) = 5.43, p = .02; SS × F, Δχ2(1) = 11.10, p < .001; C × F, Δχ2(1) = 5.86, p = .02).

Figure 1. Interaction effect of basic financial resources and self-rated physical health on levels of life satisfaction among workers.

Figure 2. Interaction effect of self-rated physical health and autonomy resources on levels of life satisfaction among retirees.

Discussion

In the present study we investigated interaction effects of self-esteem, autonomy, social support, self-rated physical health, self-rated cognitive ability, and basic financial resources on levels and changes in life satisfaction in the retirement transition. We hypothesized that the importance of a particular resource would vary depending on other available resources and more specifically that the association with life satisfaction would be stronger in the absence of other resources. We anticipated that psychological resources (i.e. self-esteem, autonomy, and perceived cognitive ability) would moderate the effects of physical and financial resources, but also that psychological resources would be more important when an individual has access to adequate social resources. Our findings show partial support for the anticipated interactions and suggest that negative effects of poor health and lack of financial security among retirees can be compensated for by higher levels of autonomy, social support, and perceived cognitive ability.

The observed compensatory effects of autonomy, social support, and self-rated cognitive ability for individuals with poor self-perceived health and lack of basic financial resources suggest that psychological mechanisms can contribute to explain heterogeneity in retirement adjustment. Our findings are in line with studies (Donaldson et al., Citation2010; Hansson et al., Citation2017; Price & Balaswamy, Citation2009) showing that perceptions of personal control are more important than material resources like health and economy for levels and changes in well-being in the retirement transition. This result also corresponds with research showing that locus of control is of particular importance for well-being among older adults with high disease load (Berg, Hassing, Thorvaldsson, & Johansson, Citation2011). The observed compensatory effect of social support among those without basic financial security accords with research showing that supportive social relations are of fundamental importance for our ability to cope with stressful life events (Hobfoll, Citation2002), although its influence relative to financial resources is previously uncovered. A potential explanation to these findings could be that people with higher autonomy and more social support are more likely to be actively engaged in the transition process, despite the fact that they do not have sufficient physical and financial resources. People who perceive their personal control as high and their social relations as supportive may for instance to a larger extent engage in various social and/or leisure activities that in turn would have beneficial effects on their level of adjustment.

The role of self-rated cognitive ability in lack of financial resources have, to our knowledge not been identified in previous research. We believe that this effect to some extent reflects the individuals’ anticipations towards retirement and the perceived ability to pursue desired activities, given that this construct was highly correlated with self-esteem. Individuals who perceive their cognitive ability as high may be more likely to view retirement in optimistic terms, and less likely to see retirement as the end of life, regardless if they have adequate financial resources or not. People who feel that they have their cognitive abilities intact are perhaps less concerned about aging related changes and more focused on potential opportunities associated with the transition.

The fact that we identified group differences between retirees and workers suggest that the compensatory effects of autonomy, social support, and self-rated cognitive ability are specific for the retirement transition and not general age-related mechanisms. While no compensatory effects were obtained for those continuously working, we found cumulative effects of self-rated physical health and basic financial resources, suggesting that workers are more likely to benefit from good health if they also have access to basic financial assets. It remains unclear, however, if the observed group differences can be explained by the retirement event in itself, or if these differences depend on other factors. For instance, retirement decisions are known to be influenced by multiple factors, including individual level variables (e.g. health and/or financial incentives) as well as organizational (e.g. opportunity to work part time), and societal (e.g. regulations in the pension system) factors (Beehr & Bennett, Citation2007, Citation2015). In this study, we found that a larger proportion of the retirees had access to basic financial resources and that a larger proportion of the workers had higher education. The fact that people are more likely to retire if they have adequate financial resources and more likely to stay at work if they are highly educated (and presumably have more advanced positions at work) may therefore have contributed to generate selection effects, i.e. the observed group differences could be related to differences in retirement intentions. The fact that we did not directly assess the participants’ retirement intentions and decisions however limits our ability to draw conclusions with respect to the role of financial resources for the decision to retire, and how this in turn might have influenced the results. Future research should therefore further investigate sources of resource interdependency in various stages of the retirement transition.

Noteworthy, our selected variables are limited in that they measure specific constructs within each domain. Retirement adjustment is preferably studied through context-sensitive measures (van Solinge & Henkens, Citation2008) and a more global measure such as life satisfaction should, therefore, be considered as an indirect indicator. However, studies of the transition require measures that are not limited to estimate only one side of the event. We therefore claim that the use of a standardized measure of life satisfaction is suitable for the aim of this study, especially given that it has previously been shown to be a reliable indicator of adaption to life events (Lucas, Citation2007). The selected resource measures are also limited to measure specific aspects of each resource domain, and subjective variables are likely to differ from more objective indicators. It should be noted, however, that the specific resource indicators were selected because they have previously been shown to predict subjective well-being, in general (Myers & Diener, Citation1995) as well as in relation to the retirement (Barbosa et al., Citation2016; Hansson et al., Citation2017). We further argue that subjective measures are of particular relevance in studying subjective well-being because they capture discrepancies between perceived and anticipated capacity (Diener, Sapyta, & Suh, Citation1998). The measure of financial resources is also somewhat insufficient as it is designed to capture people without adequate financial resources rather than the actual assets people possess. It is, however, generally argued that fundamental financial security is more important for individual well-being than excessive wealth (Diener & Biswas-Diener, Citation2002; Diener, Oishi, & Lucas, Citation2003; Diener & Seligman, Citation2004; Veenhoven, Citation1991), and we therefore claim that this measure is valid and suitable. We further caution that the reliability coefficient for the autonomy scale was relatively low and that the many significance tests performed increases the probability to incorrectly reject the null hypothesis (i.e. type I error).

Despite these limitations, we believe that the present study contributes to the current knowledge on retirement adjustment in several important ways. First of all, this study is one of the first to systematically investigate interaction effects of individual resources on levels and changes in life satisfaction across the retirement transition. The findings contribute with new insights into the adjustment process by showing that the effect of a particular resource can vary in relation to the presence of other resources, but also that these effects seems to be unique for the retirement transition. Second, in this study we acknowledged the need for more in-depth research on the role of psychological resources when studying retirement adjustment. By examining all six resources suggested in the resource-based dynamic model (Wang et al., Citation2011), we offer a more comprehensive picture of factors associated with individual differences in levels and changes in life satisfaction in the years before and after retirement. Third, our findings will hopefully stimulate theoretical developments within the field. We propose that the identified interaction effects can be integrated as an extension in the resource-based dynamic model. By showing that the effects of health and economy vary systematically in relation to levels of autonomy, social support, and perceived cognitive ability, we add an additional component of the dynamics that could contribute to a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms of retirement adjustment. Future research should focus on developing the findings in this study and investigate if these interactions also can be observed longitudinally, i.e. if resource loss can be compensated for by gains in other resource domains.

Furthermore, in order to disentangle the mechanisms of retirement adjustment, it is necessary to also consider the risk for reversed causality in the association between resources and well-being. Although the resource-based dynamic model (Wang et al., Citation2011) assumes that resource change is the driving mechanism behind changes in well-being, there is still limited empirical support for the direction of this association. For instance, resources may be essential for our ability to enjoy life in retirement, but well-being could also influence our ability to build and maintain resources in retirement. In this study, we investigated if individual resources can be linked to changes in life satisfaction, but we were not able to determine if life satisfaction also influence changes in individual resources. Future research should therefore take into account that there may be a bidirectional relationship between resources and well-being in the retirement transition.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate resource interdependency in the retirement transition and that psychosocial resources moderate the association between material resources and life satisfaction. In particular, we found that the association between physical health and life satisfaction was stronger among individuals with low autonomy, but also that the relationship between basic financial resources and life satisfaction was stronger for individuals with low social support and poor perceived cognitive ability. These results indicate that psychosocial resources may compensate for negative effects of poor health and lack of financial security in the retirement adjustment process.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barbosa, L. M., Monteiro, B., & Murta, S. G. (2016). Retirement adjustment predictors: A systematic review. Work, Aging and Retirement, 2(2), 262–219. doi:10.1093/workar/waw008

- Beehr, T. A., & Bennett, M. M. (2007). Examining retirement from a multilevel perspective. In K. S. Shultz & G. A. Adams (Eds.), Retirement: Reasons, processes, and results (pp. 277–302). New York: Springer.

- Beehr, T. A., & Bennett, M. M. (2015). Working after retirement: Features of bridge employment and research directions. Work, Aging and Retirement, 1(1), 112–128. doi:10.1093/workar/wau007

- Berg, A. I., Hassing, L. B., Thorvaldsson, V., & Johansson, B. (2011). Personality and personal control make a difference for life satisfaction in the oldest-old: Findings in a longitudinal population-based study of individuals 80 and older. European Journal of Ageing, 8(1), 13–20. doi:10.1007/s10433-011-0181-9

- Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., … Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236. doi:10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575.

- Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2002). Will money increase subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research, 57(2), 119–169. doi:10.1023/A:1014411319119

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 403–425. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056

- Diener, E., Sapyta, J., & Suh, E. (1998). Subjective well-being is essential to well-being. Psychological Inquiry, 9(1), 33–37. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0901_3

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(1), 1–31. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2350-6_9

- Donaldson, T., Earl, J. K., & Muratore, A. M. (2010). Extending the integrated model of retirement adjustment: Incorporating mastery and retirement planning. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(2), 279–289. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2010.03.003

- Earl, J. K., Gerrans, P., & Halim, V. A. (2015). Active and adjusted: Investigating the contribution of leisure, health and psychosocial factors to retirement adjustment. Leisure Sciences, 37(4), 354–372. doi:10.1080/01490400.2015.1021881

- Hansson, I., Buratti, S., Thorvaldsson, V., Johansson, B., & Berg, A. I. (2017). Changes in life satisfaction in the retirement transition: Interaction effects of transition type and individual resources. Work, Aging and Retirement. doi:10.1093/workar/wax025

- Henning, G., Lindwall, M., & Johansson, B. (2016). Continuity in well-being in the transition to retirement. GeroPsych: The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(4), 225–237. doi:10.1024/1662-9647/a000155

- Heybroek, L., Haynes, M., & Baxter, J. (2015). Life satisfaction and retirement in Australia: A longitudinal approach. Work, Aging and Retirement, 1(2), 166–180. doi:10.1093/workar/wav006

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. doi:10.1037//1089-2680.6.4.307

- Kim, J. E., & Moen, P. (2002). Retirement transitions, gender, and psychological well-being: A life-course, ecological model. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57(3), P212–P222. doi:10.1093/geronb/57.3.P212

- Leung, C. S. Y., & Earl, J. K. (2012). Retirement resources inventory: Construction, factor structure and psychometric properties. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(2), 171–182. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2012.06.005

- Lindwall, M., Berg, A. I., Bjälkebring, P., Buratti, S., Hansson, I., Hassing, L., … Johansson, B. (2017). Psychological health in the retirement transition: Rationale and first findings in the Health, Ageing and Retirement Transitions in Sweden (HEARTS) study. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–15. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01634

- Lucas, R. E. (2007). Adaptation and the set-point model of subjective well-being. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(2), 75–79. doi:10.1111/j.1467–8721.2007.00479.x

- McArdle, J. J. (2009). Latent variable modeling of differences and changes with longitudinal data. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 577–605. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163612

- Myers, D. G., & Diener, E. (1995). Who is happy?. Psychological Science, 6, 10–19. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00298.x

- Muratore, A. M., & Earl, J. K. (2015). Improving retirement outcomes: The role of resources, pre-retirement planning and transition characteristics. Ageing & Society, 35(10), 2100–2140. doi:10.1017/S0144686X14000841

- Muratore, A. M., Earl, J. K., & Collins, C. G. (2014). Understanding heterogeneity in adaptation to retirement: A growth mixture modeling approach. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 79(2), 131–156. doi:10.2190/AG.79.2.c

- Pinquart, M., & Schindler, I. (2007). Changes of life satisfaction in the transition to retirement: A latent-class approach. Psychology and Aging, 22(3), 442–455. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.442

- Price, C. A., & Balaswamy, S. (2009). Beyond health and wealth: Predictors of women’s retirement satisfaction. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 68(3), 195–214. doi:10.2190/AG.68.3.b

- R Core Team (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved on February 12, 2017, from https://www.R-project.org/.

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36.

- Schaap, R., de Wind, A., Coenen, P., Proper, K., & Boot, C. (2017). The effects of exit from work on health across different socioeconomic groups: A systematic literature review. Social Science & Medicine, 198, 36–45. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.015

- van Solinge, H. (2013). Adjustment to retirement. In M. Wang (Ed), The Oxford handbook of retirement (pp. 311–324). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- van Solinge, H., & Henkens, K. (2008). Adjustment to and satisfaction with retirement: Two of a kind? Psychology and Aging, 23(2), 422–434. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.23.2.422

- Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research, 24(1), 1–34. doi:10.1007/BF00292648

- Wang, M. (2007). Profiling retirees in the retirement transition and adjustment process: Examining the longitudinal change patterns of retirees' psychological well-being. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 455–474. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.455

- Wang, M., Henkens, K., & van Solinge, H. (2011). Retirement adjustment: A review of theoretical and empirical advancements. American Psychologist, 66(3), 204–213. doi:10.1037/a0022414

- Wang, M., & Shi, J. (2014). Psychological research on retirement. Annual Review of Psychology, 65(1), 209–233. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115131

- Wetzel, M., Huxhold, O., & Tesch-Römer, C. (2015). Transition into retirement affects life satisfaction: Short- and long-term development depends on last labor market status and education. Social Indicators Research, 125(3), 991–1009. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-0862-4.

- Yeung, D. Y. (2017). Adjustment to retirement: Effects of resource change on physical and psychological well-being. European Journal of Ageing, 1–9. doi:10.1007/s10433-017-0440-5

- Yeung, D. Y., & Zhou, X. (2017). Planning for retirement: Longitudinal effect on retirement resources and post-retirement well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–14. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01300

- Zaniboni, S. (2015). The interaction between older workers’ personal resources and perceived age discrimination affects the desired retirement age and the expected adjustment. Work, Aging and Retirement, 1(3), 266–273. doi:10.1093/workar/wav010

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30–41.