Abstract

Objectives

The current study examined how a technology system, “It’s Never 2 Late” (iN2L), may help augment traditional rehabilitation strategies for older adults with dementia by improving engagement in therapy sessions and achieving better functional outcomes.

Method

The study used a two group quasi-experimental design. Older adults with dementia (N = 96) were recruited from two rehabilitation departments housed within residential care communities. Participants received daily occupational and physical therapy sessions using treatment as usual (TAU) at one site (n = 49) or treatment with iN2L (n = 47) at the other site. A goal attainment approach was used to assess functional outcomes. It was hypothesized that patients whose therapists used iN2L in treatment will show greater attainment of therapy goals and greater engagement during OT and PT sessions than patients receiving TAU. It was also hypothesized that levels and improvement in engagement will mediate the association of treatment type (iN2L or TAU) with greater goal attainment.

Results

Participants in the iN2L treatment had significantly higher goal attainment than TAU, significantly higher levels of engagement at baseline, and significantly steeper increases in engagement over the course of therapy. The effects of treatment on goal attainment was significantly mediated by increases in engagement.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that iN2L technology has the potential to increase treatment engagement and enhance rehabilitation outcomes among older adults with dementia.

In a recent monograph, Cahill (Citation2019) proposed a model for optimal care of persons with dementia (PwD) that had two main components: a person-centered approach that identifies preferences and needs of PwDs and use of rehabilitation to identify and treat potentially remediable abilities, including cognitive functioning, mobility, and self-care. Functional abilities may decline as a result of an illness or injury or due to inactivity, such as when a PwD is restricted to bed during a hospitalization. Despite their cognitive problems, PwDs may benefit from a rehabilitation program that builds strength, mobility, balance, and other functional abilities (Muir & Yohannes, Citation2009; Vassallo, Poynter, Kwan, Sharma, & Allen, Citation2016). These functional gains make it more likely for PwDs to be able to engage in preferred and enjoyable activities. Better functioning may also lead to lower costs of care by helping PwDs stay at home longer, or require less assistance in residential care communities.

Rehabilitation with PwDs, however, can be challenging. Research on rehabilitation has found that PwDs can improve in functional abilities (Muir & Yohannes, Citation2009; Resnick et al., Citation2016), but they generally have poorer outcomes than persons without dementia (Poynter, Kwan, Sayer, & Vassallo, Citation2011; Söderqvist, Miedel, Pozner, & Tidermark, Citation2006). Inability of PwDs to engage fully in treatment has been identified as a possible reason for poorer responses (Paolucci et al. Citation2012). Lack of engagement can be an issue for any patient, but it appears more common among PwDs. Memory impairment, lack of insight, problems with other executive abilities, inability to carry out purposeful movement, and behavioral and emotional problems have been identified as interfering with participation by PwDs in therapy (e.g. McGilton, Wells, Davis, et al., Citation2007; McGilton, Wells, Teare, et al., Citation2007; Skidmore et al., Citation2010). PwDs may not understand the therapist’s instructions and may be fearful of what the therapist is trying to do (Wong & Leland, Citation2018). Lower participation, in turn, has been found to lead to poorer functional outcomes (Lenze, Munin, Dew, et al., Citation2004; Morghen et al., Citation2017). Identifying optimal strategies for engaging PwDs in rehabilitation could contribute to better treatment responses and help them resume every day and preferred activities (Lenze, Munin, Dew, et al., Citation2004; Resnick et al., Citation2016).

New technology may be useful in augmenting typical rehabilitation strategies, which can lead to improved engagement. One such approach is the “It’s Never 2 Late” (iN2L) system (Lazar, Demiris, & Thompson, Citation2016). The iN2L is a multi-functional, interactive technology platform designed primarily for older adults, with specialized rehabilitation programming developed for people who are living with various forms of dementia, cognitive decline or functional limitations. What distinguishes the iN2L from standard rehabilitation approaches is the emphasis on using customized stimuli for engaging patients in therapy. Therapists start by identifying person-centered interests and content that they can display on the iN2L system. This individualized content is used to captivate patients’ attention and motivate them to move or interact with the system or the therapist in a manner that facilitates attainment of specific functional rehabilitation goals. The mode and content of stimuli can be varied in order to address the heterogeneity in levels of function and personal background among PwDs. Therapists can draw from an extensive library of games, puzzles, visual imagery, videos, activities, and music that incorporate meaningful, person-centered stimuli into therapeutic interventions. If the initial effort does not work, therapists can easily try something else by selecting different content or adapting the level of the content to match the abilities of the person. Use of familiar stimuli might also draw upon abilities that have remained intact despite the effects of dementia. The iN2L system has been widely adopted at rehabilitation facilities in the USA and has been reported to be feasible and acceptable to patients and therapists. It has not, however, been evaluated for whether it increases engagement in treatment or has an impact on rehabilitation outcomes.

Studies of outcomes of rehabilitation must take into account the heterogeneity among patients in type of deficits and goals for treatment. A goal attainment approach has been widely used in rehabilitation and other types of treatment when there is heterogeneity in desired outcomes (Lyons et al., Citation2018; Turner-Stokes, Citation2009). Specifically, goals for various aspects of function are selected at the outset of rehabilitation, including the level of performance expected at the completion of treatment. Improvement in goals can then be compared across people with different types of disabilities and goals. A goal attainment approach is also person-centered, because the goals selected are specific to the presentation of the individual receiving treatment.

The current study examines the effects of the iN2L on participation of PwDs in rehabilitation interventions provided by Occupational and Physical Therapists (OT; PT) and on goal attainment. The following hypotheses were tested:

Patients whose therapists used iN2L in treatment will show greater attainment of therapy goals than patients receiving treatment as usual (TAU).

Patients whose therapists use iN2L will show greater increases in engagement during OT and PT sessions than patients receiving TAU.

Patients’ increases in engagement during rehabilitation will mediate the association of treatment type (iN2L or TAU) and goal attainment.

Methods

Design

This study used a quasi-experimental two group treatment-control design to compare PwDs who received rehabilitation services in a program that used the iN2L in OT and PT (iN2L site) and PwDs at a comparable rehabilitation program at a different site that did not use the iN2L (Treatment As Usual-TAU site). Both rehabilitation departments are located on the campuses of multi-level senior care communities operated by the same organization, Presbyterian SeniorCare Network. The rehabilitation departments have similar levels of staffing and use similar treatment procedures, but serve different communities that are 45 miles apart. The iN2L site had been selected to conduct a feasibility test of the system prior to a decision to adopt it at other rehabilitation sites operated by Presbyterian SeniorCare Network. The current trial was conducted during this initial test period for the iN2L.

A quasi-experimental design is appropriate for this type of study. Randomization of treatment of patients within the same rehabilitation department would likely have spillover effects because the units are open and patients not using the iN2L might request it or perceive they are receiving a lesser form of treatment. Likewise, therapists could have difficulty switching between experimental and control conditions and might develop expectations that one form of treatment is superior. These types of spillover reduce integrity of implementation of treatment and compromise internal validity of a study (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, Citation2001). A quasi-experimental design prevents this type of spillover and maintains validity of the intervention. Quasi-experimental designs are an appropriate alternative where randomized control trials (RCTs) cannot be conducted without compromising validity (Grimshaw, Campbell, Eccles, & Steen, Citation2000). Furthermore, quasi-experimental designs with control groups have been shown to be as effective as randomized trials in controlling threats to internal validity and to yield comparable findings to RCTs of the same topic (Benson & Hartz, Citation2000; Raaijmakers et al., Citation2008; Shadish, Clark, & Steiner, Citation2008; Shadish & Heinsman, Citation1997). Prior trials in rehabilitation that have introduced interventions on the unit level have sometimes used this approach (e.g. McGilton, et al., Citation2013).

One potential threat to internal validity in quasi-experimental studies is selection bias, where participants seek out the experimental treatment. In the current study, the distance between facilities (45 miles) likely eliminated selection bias. There was also no publicity around adoption of the iN2L either targeted to referral sources or the general public, that could have drawn patients differentially to the experimental site. Another threat to validity is that sites might recruit populations that differ in characteristics that affect findings. Covariates can be used, however, to adjust for differences in samples between sites that influence outcomes (Steiner, Cook, Shadish, & Clark, Citation2010). In the current study, we considered age, gender, education, housing, marital status, having living children, and cognitive functioning as possible covariates. Additionally, supervisors at the two sites independently reported personnel were comparable in skills and experience.

Intervention

The iN2L technology utilizes a client-centered design to facilitate interaction between patient and therapist. The patient’s personal interest areas are identified by therapists to assist in designing interventions that will contribute to achievement of OT and PT goals. The iN2L system has multiple options for the therapist to encourage engagement during therapy sessions. It can provide visual and auditory stimuli such as videos, music, games and exercises specific to individual rehabilitation needs and personal preferences that promote movements and activities that are part of the therapy plan. Visual, motor, and auditory tasks can be manipulated, allowing the therapist to customize the objective of the interaction with the system around the specific needs of the patient based on the plan of care.

The technology is made accessible to patients via a picture-based touch screen interface and height adjustable mounting options like a mobile cart or adjustable wall mount. The enlarged touch screen buttons can be customized with images, text and other person-centered content items that are relevant and specific to each individual. The system is customizable to meet the abilities and interests of each user and offers a wide array of program capabilities and peripheral attachments such as a hand-held telephone, music maker, joy stick, adaptive pointer and an ergometer.

OT and PT therapists at the iN2L site were trained in its use by one of the authors (CK) prior to the start of the study. Therapists were encouraged to try the iN2L, but how they used it and the amount of use was at their discretion. Therapists at the TAU site were informed about the purpose of the research. They were told that use of the iN2L was an experiment and that it might not add any benefit beyond gains associated with good clinical practice. There was no indication from comments made during an orientation session for the study or in debriefing interviews at the study's completion that therapists at the Tau site believed that the iN2L was a better approach than the usual treatment they offered.

Duration of treatment was determined largely by medical insurance, though some participants withdrew from rehabilitation prior to completion of the planned course of treatment. Mean duration of treatment was similar at the two sites: iN2L = 23.72 days, SD = 14.82; TAU site = 20.56 days, SD = 10.31, (t(93) = 1.21, p= .23). Therapy sessions were provided according to the established treatment plans for each subject, including weekends when necessary. The study was registered with Clinical.Trials.gov (Protocol ID 0007754).

Sample

Participants were recruited from consecutive new admissions to the two rehabilitation departments. The most common reasons for referral were a recent cerebrovascular accident or a fracture. Although the rehabilitation departments were located on campuses of multilevel senior residence communities, most rehabilitation patients came from outside these programs. Eligibility criteria were a pre-existing dementia diagnosis and/or a score of 23 or less on the Brief Alzheimer Screen (BAS; Mendiondo, Ashford, Kryscio, & Schmitt, Citation2003). The BAS was administered by Speech Language Pathologists as part of the therapy admission screening process. The research assistant (RA) at each site approached individuals who met these criteria about participating in the study. For persons indicating a willingness to participate, the RAs used a checklist that reflects current standards for screening ability to give consent (Howe, Citation2012). Participants who demonstrated understanding of the research and the consent decision and who indicated an unambiguous willingness to take part were asked to sign a consent form for the study. When a potential participant indicated willingness to participate but did not demonstrate ability to give consent, the RA contacted the individual who held power of attorney (PoA) for consent. In those cases, both the PwD and the individual with PoA had to give consent. Continuing consent was obtained at each rehabilitation session that was observed (Howe, Citation2012). Part of the study included observation of therapy sessions at both sites, and so therapists were asked to sign a consent document that provided confidentiality of their ratings. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Pennsylvania State University.

Forty-eight people were recruited for the experimental site. One person subsequently left the rehabilitation program before treatment began, and was dropped from the study. Fifty people were recruited for the TAU site. One person died after one week in rehabilitation, and was removed from the sample. The final samples were 47 for the iN2L site and 49 for the TAU site.

Measures

Pittsburgh rehabilitation participation scale (PRPS)

The PRPS is a widely used rating scale with established reliability and validity for assessing engagement in rehabilitation (Lenze, Munin, Quear et al., Citation2004). Ratings of participation were made on a 6-point scale ranging from no participation (= 0) to excellent (= 5). Higher scores indicate better participation in therapy activities and exercises. RAs were trained in scoring the PRPS by one of the authors (SZ). To determine reliability of ratings, we asked therapists to make ratings of participation in sessions that had been observed by the RAs. Inter-rater reliability between RA and therapist scores was computed using intra-class correlations (ICC) with a consistency definition (Hallgren, Citation2012). The ICC was 0.87, df = 1742, p < .000.

In order to assess whether participation at the iN2L and TAU sites changed with treatment, observations of sessions were made during the course of therapy. The goal was to make observations of most PT and OT sessions. The initial observed session took place after consent was obtained and the final observed session usually occurred on the day prior to or on the day of discharge. Observations were not made in instances when two or more subjects were receiving treatment at the same time. When an observation was skipped for that reason, the RA would make sure to observe that subject at the next therapy session. Treatment provided on weekends was also not observed.

Goal attainment

As part of standard procedures in both rehabilitation departments, OT and PT conducted initial and final assessments (at discharge) of functioning, mobility, and activities of daily living (ADL). OT rated 23 items and PT rated 13 items. Items were drawn from the Functional Independence Measure (FIM; Keith, Granger, Hamilton, & Sherwin, Citation1987) and the Barthel Index (Collin, Wade, Davies, & Horne, Citation1988). Ratings were made on a 10-point scale that ranged from Unable to do any of the activity (= 1) to Performing 100% of a task (= 10). Using the baseline assessments and discussion with patients, therapists identified specific functions as the goals of therapy. For each goal, therapists set an expected level of functioning to be obtained by the end of treatment. At the completion of treatment, therapists conducted another assessment of each patient and entered final functioning scores in medical records. Goal attainment was scored by RAs by comparing initial and final functioning on each item that had been identified as a goal. A dichotomous rating was used (0 = Not attained and 1 = Attained or exceeded).

Brief Alzheimer screen (BAS)

The BAS (Mendiondo et al., Citation2003) was used for determination of eligibility, to evaluate equivalence of cognitive functioning of the experimental and TAU groups, and as a possible covariate. The BAS is a brief screening measure consisting of four items that were found to best discriminate persons with mild symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease from persons without dementia. The items are: recall of three items, today’s date, spelling “world” backwards and a fluency task (naming animals). Using data sets with well-established diagnosis, Mendiondo and colleagues reported that the BAS had high specificity (Area Under the Curve-AUC = .994) and sensitivity (AUC = .861), which are comparable to the Mini-Mental State Exam.

Demographics

Demographic information was obtained during an initial interview with patients conducted by the RAs. Information was obtained for gender, marital status, age, having living children (1 = Yes and 0 = No), type of permanent residence (1 = Own home and 0 = Other setting) and education (1 = Less than 12 years, 2 = Some high school, 3 = High school graduate, 4 = Some college, 5 = College graduate, and 6 = Post college education).

Analytical strategy

As an initial step, participants in the iN2L and TAU group were compared on demographic variables, BAS scores and amount of treatment to evaluate equivalence of the groups. Next, we examined the first hypothesis that percent goal attainment would differ between the two groups using a multiple regression with demographics and BAS as predictors, using SPSS25.

For the second hypothesis that engagement would increase more over time in the iN2L group compared to TAU, a growth curve analysis was run using a multilevel model (PROC MIXED) in SAS. with engagement levels from daily therapy sessions as outcomes. The model used restricted maximum (REML) likelihood estimation, which is preferred for smaller sample size. Time was indexed in these models by consecutively numbering the therapy sessions observed by RAs. We did not differentiate between PT and OT sessions in numbering the sessions. Treatment type (iN2L or TAU) was modeled as both a main effect and a moderator of the linear slope of (i.e. changes in) engagement over time. The model controlled for demographics and other characteristics that might be associated with the treatment and engagement, including participants’ age, gender, currently married, having children, education levels, lived in own home, and cognitive functioning. Non-significant covariates were trimmed from the models for parsimony (Vandekerckhove, Matzke, & Wagenmakers, Citation2015).

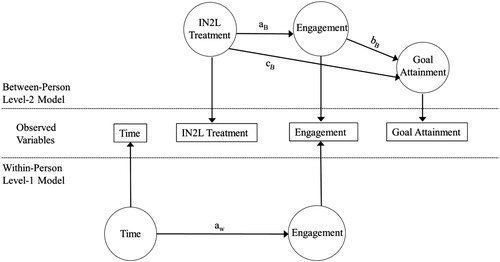

For the third hypothesis that engagement would mediate the association of treatment and goal attainment,a multilevel regression model was run using MPlus. Specifically, the TWOLEVEL modeling procedure was used, along with the MODEL INDIRECT command to estimate the total and indirect (i.e. mediation) effects. The hypothesized model is graphed in . The iN2L treatment [between-person (BP), level 2] and time as measured by therapy sessions [within-person (WP), level 1] are the predictors, and percentage goal attainment is the between-person (BP, level 2) outcome. The variance in engagement scores was latently partitioned into both WP (level 1) and BP (level 2) components, and we used them as both the WP outcome and the BP mediator for the direct association between iN2L treatment and percentage goal attainment. The mediation analysis tested specifically whether the latent path of the indirect association between iN2L treatment and goal attainment through engagement (iN2L treatment→Engagement→Goal attainment) was significant. The default estimator was used in the analysis, which was maximum likelihood with robust standard errors using a numerical integration algorithm. No adjustments were made to the data in these analyses.

Results

Comparisons of participants in the iN2L and TAU groups on demographic variables and BAS scores are shown in . There were no significant differences between the two sites on any variables.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and cognitive functioning.

To test Hypothesis 1, we fit multiple regression models to examine percentage goal attainment differences between the iN2L and TAU groups. We first fit a full model, where we used treatment type as the predictor, and controlled for the following covariates: age, gender, level of education, currently married, lived in own homes, and cognitive functioning. Because none of the covariates were significant, we trimmed them from the final model for parsimony. Confirming the hypothesis, the iN2L group had a significantly higher percentage goal attainment than TAU (54% compared to 41%; β = 0.151, se = 0.070, p = .033).

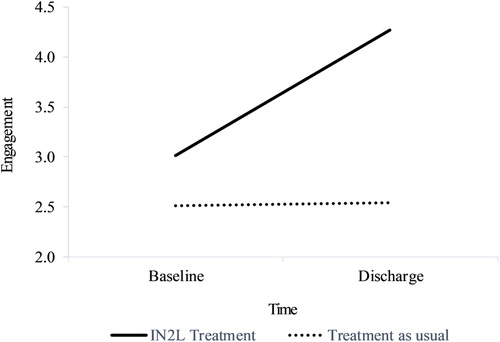

Results for Hypothesis 2 concerning engagement over the course of treatment are shown in and . Growth curve models indicated that participants in the iN2L group had a higher level of engagement at baseline (β = 0.459, se = 0.134, p = .001), and a steeper increase in engagement over the course of therapy (Time × iN2L Treatment interaction; β = 0.023, se = 0.009, p = .015) compared to the TAU group, thus confirming the hypothesis. Parameter estimates from the final growth curve model are presented in .

Figure 2. Slopes for level of engagement in therapy sessions over the course of treatment for iN2L and TAU groups.

Table 2. Growth curve model of engagement over time.

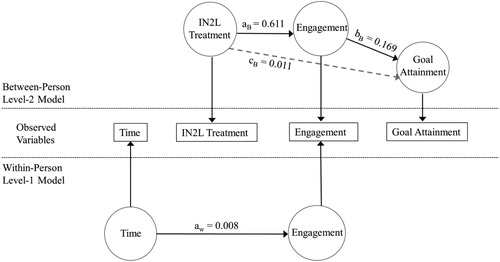

Turning to Hypothesis 3, the parameter estimates based on the multilevel mediation are presented in and . Consistent with the growth curve model, the within-person level effect showed that engagement increased over time (i.e. the aw path, β = 0.008, se = 0.004, p = .032). At the between-person level, iN2L treatment was associated with increases (i.e. greater slope) in engagement (i.e. the aB path, β = 0.611, se = 0.139, p = .000). Increases in engagement, in turn, were associated with higher percentage of goal attainment (i.e. the bB path, β = 0.169, se = 0.056, p = .003). The specific test of mediation was based on the latent paths of the indirect associations between iN2L treatment and goal attainment through engagement slope (i.e. the IN2L treatment→Engagement→Goal attainment paths). The paths were significant (β = 0.103, se = 0.041, p = .012), indicating confirmation of Hypothesis 3 that the effects of treatment on goal attainment was mediated by increases in engagement.

Figure 3. Results of the mediation model where engagement mediated the direct association between IN2L treatment and goal attainment.

Note: Standard parameter estimates for the within-person (bottom) and between-person (top) models. Latent variables are represented by circles, and measured variables are represented by rectangles. Significant estimates (p < .05) are shown in solid black and non-significant estimates (p > .05) are in dashed gray.

Table 3. Multilevel mediation model on the indirect effect of engagement on direct association between IN2L treatment and goal attainment.

Discussion

The use of the iN2L in rehabilitation with PwD was related to increased participation in treatment and improved functional outcomes compared to TAU. The mediation analysis supported the hypothesized mechanism, specifically, that use of the iN2L in rehabilitation is associated with improved participation, which in turn relates to better goal attainment.

These findings are consistent with prior studies on the pivotal role of engagement in rehabilitation with PwD (McGilton, Wells, Davis, et al., Citation2007; McGilton, Wells, Teare, et al., Citation2007; Morghen et al., Citation2017; Paolucci et al., Citation2012; Skidmore et al., Citation2010). As in many prior studies, the current research used the PRPS to assess engagement. Previous studies, however, were primarily correlational and did not examine if interventions increased participation or led to improved rehabilitation outcomes. The findings from the current study are also noteworthy, given the advanced age of the sample (mean = 86 years) and the severity of cognitive impairment. Other technologies as well as interpersonal strategies could have similar beneficial effects that improve participation and therapy outcomes (Lazar, Demiris, & Thompson, Citation2016). An enhanced focus on engagement may be a fundamental step for improving rehabilitation outcomes for PwDs.

An advantage of the iN2L is that has the potential to be a scalable tool that could be adopted widely. It has been deployed in over 3000 locations, including rehabilitation units and long-term care residential and community program. In 25 percent of facilities, it is used solely as a rehabilitation tool. In the other locations, it is often shared for use between rehabilitation and other programs. Cost of iN2L units such as those employed in the test site range from $5000 to $15000, depending on size and features. That compares favorably to other rehabilitation equipment.

Though the findings are encouraging, the study should be viewed as a preliminary test that warrants more research to confirm these results. The study was initiated immediately after therapists at the experimental site completed training on the iN2L and so they were relatively inexperienced with the system. The experimental protocol consisted of making the iN2L available, and therapists were provided with suggestions about how therapy could be augmented by the iN2L in several functional impairment pathways. In the end, however, it was up to therapists to determine how and how much to use the iN2L. We know from RA reports that OT and PT made regular use of the iN2L, particularly for stimulation, to enhance specific movement, and to build endurance. But unlike a more developed intervention, we did not institute a protocol for what types of treatment should be implemented with the iN2L or for the amount of its use. The most typical interactions using iN2L were brief, about 5 min, and therapists did not employ the iN2L in every session. Even though the study has now ended, therapists have continued to work to identify and catalog ways of applying the iN2L to assist in therapy. A study conducted with therapists who were more experienced in using the iN2L might show stronger outcomes for participation and functioning. Future studies could also document what specific applications and how much time on the iN2L might be optimal. A larger sample size would also make it possible to identify which patients might have a better response with the iN2L.

The use of a quasi-experimental design reduced the risk of spillover between the experimental and control groups that would have been likely had an RCT been conducted with assignment within rehabilitation units. Characteristics of patients at the two programs were similar. Initial cognitive functioning was also similar between groups. The initial participation scores on the PRPS were lower at the TAU site, but that was taken into account in the growth curve analysis to compare changes in participation at the two sites. That analysis showed a clear upswing in participation engagement at the iN2L site compared to the TAU group. To address the issue of equivalence further, we conducted post-hoc analyses to assess if initial ADL performance differed between the two groups. Using ratings of ADL made by OTs as part of their initial assessment, we found that the iN2L group had slightly higher functioning but the difference between groups was not significant [t (83) = 1.72, p=.09].

Another potential limitation is that the study was not blinded, but we saw no indication in our discussion with therapists at the TAU site that they thought they were disadvantaged in any way compared to the iN2L site. Likewise, the therapists using iN2L began the study with a healthy skepticism about whether the system would be useful. We cannot, however, rule out if unmeasured differences between the two sites influenced the findings.

One factor we did not consider is if engagement would be used in similar ways by the two different disciplines involved in the study, OT and PT. The PRPS measure was designed for and has been used widely by both OT and PT (e.g. Lenze, Munin, Quear et al., Citation2004; Skidmore et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, in discussions with senior staff and with OT and PT at both sites, no one raised the issue that OT and PT approach engagement differently. We did, however, conduct a post-hoc analysis to determine if PT and OT rated engagement differently. Using the ratings made by the RAs, we found no significant difference in engagement ratings between OT and PT [t (1802) = .071, p = .95].

A fundamental question not addressed in the available data is the extent to which improvements in functioning carried over into everyday life after discharge from rehabilitation. We had hoped to obtain information about ongoing functioning with telephone follow-ups, but getting detailed and reliable information from participants over the phone proved difficult. In future studies, in-person interviews and assessment as well as informant reports could be used to ascertain maintenance of gains in function.

In conclusion, the iN2L system adds to therapists’ clinical toolbox, helping them gain the attention of PwDs and engage them in activities more effectively. Developing new approaches for increasing participation in rehabilitation as well as enhancing current strategies have the potential to help PwDs more fully benefit from rehabilitation. Helping PwDs remain active in their daily lives is perhaps the most effective way available to sustain good quality of life.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the research assistants on the study, Erika Aughton and Adedoyin Adeyeye for their excellent work on this project, the supervisors of the rehabilitation departments, Joni Krajcovic, and Dan Sekora, who facilitated the implementation of the research at every step, and the rehabilitation team at both departments for their cooperation.

Disclosure statement

Chris Krause is an employee of It’s Never 2 Late. His role on the study involved training therapists in use of the iN2L and providing text on the operation of the iN2L. He was not involved in data collection, analysis, or interpreting the findings. No other authors report a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Benson, K., & Hartz, K. (2000). A comparison of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. New England Journal of Medicine, 342(25), 1878–1886.

- Cahill, S. (2019). Dementia and human rights. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

- Collin, C., Wade, D. T., Davies, S., & Horne, V. (1988). The Barthel ADL Index: A reliability study. International Disability Studies, 10(2), 61–63. doi:10.3109/09638288809164103

- Grimshaw, J., Campbell, M., Eccles, M., & Steen, N. (2000). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for evaluating guideline implementation strategies. Family Practice, 17 (90001), 11S–S16. doi:10.1093/fampra/17.suppl_1.S11

- Hallgren, K. A. (2012). Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: An overview and tutorial. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 8(1), 23–34.

- Howe, E. (2012). Informed consent, participation in research, and the Alzheimer’s patient. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 9, 47–51.

- Keith, R. A., Granger, C. V., Hamilton, B. B., & Sherwin, F. S. (1987). The functional independence measure: A new tool for rehabilitation. Advances in Clinical Rehabilitation, 1, 6–18.

- Lazar, A., Demiris, G., & Thompson, H. J. (2016). Evaluation of a multifunctional technology system in a memory care unit: Opportunities for innovation in dementia care. Informatics for Health and Social Care, 41(4), 373–386. doi:10.3109/17538157.2015.1064428

- Lenze, E. J., Munin, M., Dew, M. A., Rogers, J. C., Seligman, K., Mulsant, B. H., & Reynolds, C. F. I. I. (2004). Adverse effects of depression and cognitive impairment on rehabilitation participation and recovery from hip fracture. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(5), 472–478. doi:10.1002/gps.1116

- Lenze, E. J., Munin, M., Quear, T., Dew, M. A., Rogers, J. C., Begley, A. E., & Reynolds, C. F. III (2004). The Pittsburgh Rehabilitation Participation Scale: Reliability and validity of a clinician-rated measure of participation in acute rehabilitation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 85(3), 380–384. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.001

- Lyons, K. D., Newman, R. M., Kaufman, P. A., Bruce, M. L., Stearns, D. M., Lansigan, F., … Hegel, M. T. (2018). Goal attainment and goal adjustment of older adults during person-directed cancer rehabilitation. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(2), 7202205110p1–7202205110p8. doi:10.5014/ajot.2018.023648

- McGilton, K. S., Davis, A. M., Naglie, G., Mahomed, N., Flannery, J., Jaglal, S., … Stewart, S. (2013). Evaluation of patient-centered rehabilitation model targeting older persons with a hip fracture, including those with cognitive impairment. BMC Geriatrics, 13(1), 136–144. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-13-136

- McGilton, K., Wells, J., Davis, A., Rochon, E., Calabrese, S., Teare, G., … Biscardi, M. (2007). Rehabilitating patients with dementia who have had a hip fracture. Part II: Cognitive symptoms that influence care. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, 23(2), 174–182. doi:10.1097/01.TGR.0000270186.36521.85

- McGilton, K., Wells, J., Teare, G., Davis, A., Rochon, E., Calabrese, S., … Boscart, V. (2007). Rehabilitating patients with dementia who have had a hip fracture. Part I: Behavioral symptoms that influence care. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, 23(2), 161–173. doi:10.1097/01.TGR.0000270185.98402.a6

- Mendiondo, M. S., Ashford, J. W., Kryscio, R. J., & Schmitt, F. A. (2003). Designing a brief Alzheimer Screen (BAS)). Journal of Alzheimer's Disease: JAD, 5(5), 391–398. doi:10.3233/jad-2003-5506

- Morghen, S., Morandi, A., Guccione, A. A., Bozzini, M., Guerini, F., Gatti, R., … Bellelli, G. (2017). The association between patient participation and functional gain following inpatient rehabilitation. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 29(4), 729–736. doi:10.1007/s40520-016-0625-3

- Muir, S. W., & Yohannes, A. M. (2009). The impact of cognitive impairment on rehabilitation outcomes in elderly patients admitted with a femoral neck fracture: A systematic review. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy, 32(1), 24–32. doi:10.1519/00139143-200932010-00006

- Paolucci, S., Di Vita, A., Massicci, R., Traballesi, M., Bureca, I., Matano, A., … Guariglia, C. (2012). Impact of participation on rehabilitation results: A multivariate study. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 48(3), 455–466.

- Poynter, L., Kwan, J., Sayer, A. A., & Vassallo, M. (2011). Does cognitive impairment affect rehabilitation outcome? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(11), 2108–2111. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03658.x

- Raaijmakers, M., Koffijberg, H., Posthumus, J., van Hout, B., van Engeland, H., & Matthys, W. (2008). Assessing performance of a randomized versus non-randomized study design. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 29(2), 293–303. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2007.07.006

- Resnick, B., Beaupre, L., McGilton, K. S., Galik, E., Liu, W., Neuman, M. D., … Magaziner, J. (2016). Rehabilitation interventions for older individuals with cognitive impairment post hip fracture: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17(3), 200–205. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2015.10.004

- Shadish, W. R., Clark, M. H., & Steiner, P. M. (2008). Can nonrandomized experiments yield accurate answers? A randomized experiment com- paring random to nonrandom assignment. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 103(484), 1334–1343. doi:10.1198/016214508000000733

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2001). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

- Shadish, W. R., & Heinsman, D. T. (1997). Experiments versus quasi-experiments: Do they yield the same answer? NIDA Research Monograph, 170, 147–164.

- Skidmore, E. R., Whyte, E. M., Holm, M. B., Becker, J. T., Butters, M. A., Dew, M. A., … Lenze, E. J. (2010). Cognitive and affective predictors of rehabilitation participation after stroke. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 91(2), 203–207. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2009.10.026

- Söderqvist, A., Miedel, R., Pozner, S., & Tidermark, J. (2006). The influence of cognitive function on outcome after a hip fracture. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American), 88, 2115–2122. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.01409

- Steiner, P. M., Cook, T. D., Shadish, W. R., & Clark, M. H. (2010). The importance of covariate selection in controlling for selection bias in observational studies. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 250–267. doi:10.1037/a0018719

- Turner-Stokes, L. (2009). Goal attainment scaling (GAS) in rehabilitation: A practical guide. Clinical Rehabilitation, 23(4), 362–370. doi:10.1177/0269215508101742

- Vandekerckhove, J., Matzke, D., & Wagenmakers, E. J. (2015). Model comparison and the principle of parsimony. In J. R. Busemeyer, Z. Wang, J. T. Townsend, & A. Eidels (Eds.), Oxford handbook of computational and mathematical psychology (pp. 300–319). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Vassallo, M., Poynter, L., Kwan, J., Sharma, J. C., & Allen, S. C. (2016). A prospective observational study of outcomes from rehabilitation of elderly patients with moderate to severe cognitive impairment. Clinical Rehabilitation, 30(9), 901–908. doi:10.1177/0269215515611466

- Wong, C., & Leland, N. E. (2018). Clinicians’ perspectives of patient engagement in post-acute care: A social ecological approach. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 36(1), 29–42. doi:10.1080/02703181.2017.1407859