Abstract

Objectives

Loneliness and social isolation are described similarly yet are distinct constructs. Numerous studies have examined each construct separately; however, less effort has been dedicated to exploring the impacts in combination. This study sought to describe the cumulative effects on late-life health outcomes.

Method

Survey data collected in 2018–2019 of a randomly sampled population of US older adults, age 65+, were utilized (N = 6,994). Survey measures included loneliness and social isolation using the UCLA-3 Loneliness Scale and Social Network Index. Participants were grouped into four categories based on overlap. Groups were lonely only, socially isolated only, both lonely and socially isolated, or neither. Bivariate and adjusted associations were examined.

Results

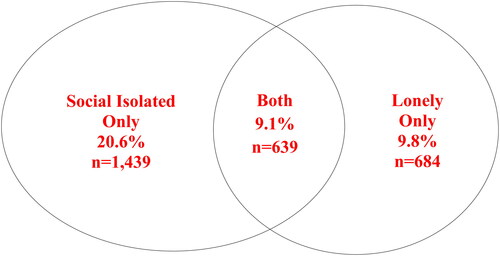

Among participants (mean age = 76.5 years), 9.8% (n = 684) were considered lonely only, 20.6% (n = 1,439) socially isolated only, 9.1% (n = 639) both lonely and socially isolated, and 60.5% (n = 4,232) neither. Those considered both lonely and socially isolated were more likely to be older, female, less healthy, depressed, with lower quality of life and greater medical costs in bivariate analyses. In adjusted results, participants who were both lonely and socially isolated had significantly higher rates of ER visits and marginally higher medical costs.

Conclusion

Results demonstrate cumulative effects of these constructs among older adults. Findings not only fill a gap in research exploring the impacts of loneliness and social isolation later in life, but also confirm the need for approaches targeting older adults who are both lonely and socially isolated. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, this priority will continue to be urgent for older adults.

Introduction

Loneliness and social isolation have separate and distinct definitions; however, in some instances, the terms can be found used interchangeably and as a proxy for one another in published commentaries and research studies. Loneliness is typically defined as the subjective state of a person’s desired and actual relationships and a measure of relationship quality (Cacioppo et al., Citation2002; Cornwell & Waite, Citation2009; Musich et al., Citation2015; Ong et al., Citation2016). In contrast, social isolation is an objective count of relationships, social interactions, and social contacts, determined by their quantity and sometimes quality (Cudjoe et al., Citation2020; MacLeod et al., Citation2018). While these constructs can overlap, not all assessment, evaluation, and intervention approaches work universally for these constructs; thus, they should be considered differently yet relative to one another (NASEM Citation2020).

Previous studies indicate up to 55% of US older adults age 65 years or older report some level of loneliness (Musich et al., Citation2015; Perissinotto et al., Citation2012). Meanwhile, social isolation is estimated to impact up to 40% of older adults age 60 and older (Cudjoe et al., Citation2020; MacLeod et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, current evidence suggests that many older adults are either socially isolated, lonely, or both, which can put their health at risk in many ways (Courtin & Knapp, Citation2017). Recently, the AARP Foundation commissioned a committee through the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) to examine the current science and future directions of loneliness and social isolation in older adults. Their consensus 2020 report highlights many risk factors that are associated with loneliness and social isolation including social, cultural, and environmental factors (e.g. age, gender, housing, location, living alone), psychological and cognitive factors (e.g. depression, anxiety, impairment), and physical health factors (e.g. health status, presence of chronic diseases, and limited function). In addition, many associated health outcomes have been associated with the two constructs including cardiovascular disease, stroke, dementia, and mortality (NASEM Citation2020).

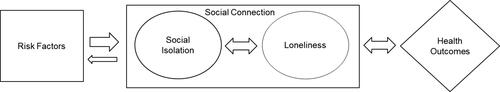

An adaptation of the NASEM guiding framework of loneliness and social isolation is shown in . Overall, the theoretical framework demonstrates that there is a bidirectional relationship between loneliness and social isolation under the umbrella term social connection (Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2017) as well as a relationship with pre-existing risk factors, and specific health outcomes (Donovan & Blazer, Citation2020; NASEM Citation2020). As mentioned, previous studies have demonstrated that loneliness and social isolation are both independently associated with similar negative physical and mental health outcomes later in life including higher rates of mortality, depression, and cognitive decline (Beutel et al., Citation2017; Drageset et al., Citation2013; Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2010; Citation2015; Citation2017; Kelly et al., Citation2017; Kuiper et al., Citation2015; Luo & Waite, Citation2014; Musich et al., Citation2015; Ong et al., Citation2016; Perissinotto et al., Citation2012). However, most of these studies examined the two constructs independently of each other.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework of loneliness, social isolation, and associated health outcomes.

Note. Adaptation of guiding framework developed by the Committee on the Health and Medical Dimensions of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults 2020 (NASEM Citation2020).

Figure 2. Distribution of loneliness and social isolation in our sample of older adults (N = 6,994). Note: 60.5% were Neither (n = 4,232)

.

For instance, loneliness has shown independent associations with depression, poor sleep, hypertension, cognitive decline, and other poor health outcomes (Hackett et al., 2012; Hawkley et al., Citation2010; MacLeod et al., Citation2018; Musich et al., Citation2015; Perissinotto et al., Citation2012; Steptoe et al., Citation2004). Meanwhile, social isolation has been associated with increased cardiovascular disease, inflammatory processes, increased dementia risk, disability, cognitive decline, mortality, and reduced quality of life (QOL) in independent analyses (Barth et al., Citation2010; Bassuk et al., Citation1999; Grant et al., Citation2009; Heffner et al., Citation2011; Shankar et al., Citation2011; Steptoe et al., Citation2013). In addition, social isolation puts older adults at an increased risk for loneliness (Dickens et al., Citation2011; MacLeod et al., Citation2018; Masi et al., Citation2011).

Despite the awareness of loneliness and social isolation as serious independent health risks, the combined and cumulative impact of these constructs has not been studied extensively. A handful of studies have attempted to examine both loneliness and social isolation in the same analyses (Beller & Wagner, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Donovan et al., Citation2017; Hakulinen et al., Citation2018; Holwerda et al., Citation2014; Ong et al., Citation2016; Shankar et al., Citation2013; Steptoe et al., Citation2013; Wilson et al., Citation2007). Specifically, these studies have primarily modeled both loneliness and social isolation as separate predictors of various health outcomes but have not examined their cumulative effect. For instance, Steptoe et. al found that social isolation remained the strongest predictor of mortality as compared to loneliness when modeled together (Steptoe et al., Citation2013). To our knowledge, no study has examined the impact of having both loneliness and social isolation as a predictor variable.

Elsewhere, researchers have found that reduced QOL, increased healthcare utilization, and overall higher medical costs can be attributed to loneliness and social isolation in joint analyses (Gerst-Emerson & Jayawardhana, Citation2015; Greysen et al., Citation2013; Hawker & Romero-Ortuno, Citation2016; Jakobsson et al., Citation2011; Shaw et al., Citation2017; Valtorta et al., Citation2018). Nevertheless, research exploring the outcomes of older individuals experiencing concurrent loneliness and social isolation remains limited. It’s been suggested that the health risks associated with loneliness and isolation are equivalent to the well-established detrimental effects of smoking and obesity (Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, loneliness and social isolation are particularly problematic in old age due to decreasing economic and social resources, functional limitations, the death of relatives and spouses, and changes in family structures and mobility (Courtin & Knapp, Citation2017). Thus, interventions that promote improving social connectedness and eliminating social barriers could be extremely important in improving outcomes in older adults including promoting active aging (Stathi et al., Citation2020).

With this in mind, the purpose of this study was to examine loneliness and social isolation in a large older adult population, and to serve as one of the first studies to examine both constructs in a cumulative manner. Specifically, this study aimed to 1) describe the overlap between loneliness and social isolation by identifying those who are both lonely and socially isolated, lonely only, socially isolated only, or neither; and 2) examine the cumulative effect of loneliness and social isolation on various health outcomes. Outcomes of interest included QOL, healthcare utilization and medical costs. Based on the research literature, we hypothesized that study participants who were both lonely and socially isolated would be more likely to be older, female, with poorer health and greater risk factors compared to adults who were only lonely, socially isolated, or neither. In addition, study participants who were both lonely and socially isolated would be more likely to have lower QOL, higher healthcare utilization, and higher medical costs.

Methods

Study participants

Approximately 5 million individuals are covered by an AARP® Medicare Supplement Insurance Plan from UnitedHealthcare (UHC), herein referred to as AARP Medicare Supplement insureds. These plans are offered in all 50 states, Washington DC, and various US territories.

In 2018 and 2019, random samples of AARP Medicare Supplement insureds, 65 years or older, with 12 months of continuous coverage, were surveyed as a larger research effort to improve customer experience. Surveys were administered from June through August of each year in which 16,000 AARP Medicare Supplement insureds (per year) were mailed surveys using a nationally randomized methodology. In total, 8,672 participants completed surveys (4,696 respondents in 2018 and 3,976 respondents in 2019), an overall 27% response rate. After accounting for duplicates (n = 4); eligibility and potential cost outliers (n = 53); and missing/incomplete survey responses (n = 1,621), 6,994 survey participants were included in this study analysis. This study was approved by the New England Institutional Review Board.

Survey and data collection

Surveys were developed by UnitedHealthcare to assess customer experience and aspects of health including psychosocial and wellness constructs on a yearly basis. For this study, measures of loneliness and social networks (an indicator of social isolation) were examined in relation to several other survey components (e.g. quality of life), and administrative and medical claims data.

Loneliness

Loneliness was captured using the 3-item Revised University of California, Los Angeles

(UCLA-3) Loneliness Scale (Hughes et al., Citation2004). The UCLA-3 asks how often respondents 1) feel left out, 2) feel lack of companionship, and 3) feel isolated from others. For each item, possible responses were: ‘never or hardly ever’ (3 points), ‘some of the time’ (2 points), and ‘often’ (1 point). Responses were then reverse-coded and summed to a score ranging from 3 to 9, with higher scores indicating greater loneliness. Cronbach’s α for this measure was 0.73. For the purpose of this study, we classified participants as ‘lonely’ with a score of 6 or higher, which is consistent with participants who responded ‘some of the time’ or ‘often’ to at least two of the three components.

Social isolation

Social isolation was based on questions from an adapted Social Network Index (SNI) (Musich et al., Citation2019), which counts the number of social connections. Specifically, five questions were used to assess SNI: 1) In a typical week, how many times do you talk on the telephone with family, friends, or neighbors?, 2) In a typical week, how often do you get together with friends or relatives, such as going out together or visiting in each other’s homes?, 3) How often do you attend church or religious services or activities of your religious organization (per month)?, 4) How often do you attend meetings of the club or organizations you belong to (per month)?, and 5) Are you married or living together with someone in a partnership? Responses to questions 1–4 were scored 0 times = 0, 1–2 times = 1, 3–4 times = 2, and 5 or more times = 3. Responses to married or living together were scored yes = 1 and no = 0. All responses were summed for a score ranging from 0 to 13, with a high score indicating greater social diversity, and a lower score indicating greater social isolation. Categories of social networks were formed based on the SNI score: 0–4 represented a ‘limited’ social network, 5–7 a ‘medium’ social network, and ≥ 8 a ‘diverse’ social network (Aung et al., Citation2016; Musich et al., Citation2019). For this study, ‘socially isolated’ participants were defined by SNI scores of 0–4, distinguishing those participants with limited social networks.

Depression

Depression was measured using the self-reported Patient Health Quesionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) (Kroenke et al., Citation2003), a 2-item depression screening tool that is well validated and used frequently in clinical settings. The 4-level responses were scored 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) for a total score range of 0 to 6. The score was then dichotomized as not depressed (PHQ-2 score < 3) and depressed (PHQ-2 score ≥ 3). Cronbach’s α = 0.75.

Quality of life

Quality of life (QOL) was assessed using the 12-item Veteran’s RAND (VR-12) (Selim et al., Citation2009). The VR-12 is a validated general health questionnaire resulting in a measure asking participants about their health-related QOL in the previous four weeks. Two subscales scales were derived from this measure: physical component (PCS) and mental component (MCS) scores. These measures are scored on a scale of 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better physical and mental QOL. Cronbach’s α = 0.99.

Demographics and socioeconomic factors

Demographic factors included age and gender; socioeconomic indicators were based on zip codes. Age groups were defined as 64–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, and ≥85 years. Geographic regions (Northeast, South, Midwest, and West), Rural Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) (e.g. urban, suburban, rural), and low, medium, and high minority areas and medium household income were geocoded from respondents’ zip codes.

Health status

Medical claims data were used to describe health status using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (Charlson et al., Citation1987; Sundararajan et al., Citation2004). The CCI focuses on the presence and quantity of specific comorbid conditions. Higher CCI scores indicate a greater number of comorbidities and poorer overall health status. Finally, the number of emergency room (ER) visits and inpatient (IP) admissions within the past 12 months were collected as well as total medical cost from participants’ medical claims.

Statistical analyses

Prior to initiating primary analyses, survey respondents and non-respondents were assessed to account for any potential selection bias; however, no significant differences in characteristics emerged. Participants were then grouped into four categories based on their loneliness and social isolation classifications using the UCLA-3 Loneliness Scale and SNI. Thus, participants were categorized into groups aligned with their overlap of loneliness and social isolation: lonely only, socially isolated only, both lonely and socially isolated, and neither (). Bivariate and adjusted associations between groups, sociodemographic status, and healthcare characteristics were then examined. Descriptive analyses for respondents’ loneliness and social isolation included basic summary statistics and bivariate comparisons across all respondent demographics and survey responses. For QOL and total medical costs, multivariate regression models were assessed and adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. age, gender) and health status (CCI). Multivariate logistic models were performed for ER visits and IP admissions. For all models, neither was designated as the reference group. All analyses were completed using SAS Enterprise Guide Version 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographics and health status

Among survey participants, 9.8% (n = 684 of 6,994) were classified as lonely only, 20.6% (n = 1,439 of 6,994) as social isolated only, 9.1% (n = 639 of 6,994) as both lonely and socially isolated, and 60.5% (n = 4,232 of 6,994) as neither ( and ). Respondents were primarily female (55.0%, n = 3,843 of 6,994), 70–74 years of age (27.1%, n = 1,899 of 6,994), and residing in an urban area (70.5%, n = 4,931 of 6,994). Approximately 54% (n = 3,772 of 6,994) of participants lived in communities designated as low minority (e.g. White) and 37.2% (n = 2,601 of 6,994) and 48.3% (n = 3,380 of 6,994) lived in medium- and high-income zip codes, respectively. Thirty-seven percent of participants had no co-morbidities based on CCI. The average CCI score was 1.93 (SD = 2.27) ().

Table 1. Bivariate, unadjusted relationship between socio-demographic and health characteristics and loneliness and social isolation (N = 6,994).

Table 2. Bivariate, unadjusted associations between healthcare outcomes and loneliness and social isolation (N = 6,994).

Significant differences by age, gender, region, and health status were present in bivariate analyses across groups (). Overall, participants who were both lonely and socially isolated were older and less healthy as compared to other groups. Furthermore, a higher proportion of participants (22.4%, 143/639) were both lonely and socially isolated in the oldest age category (≥ 85 years). Additionally, there was a higher percentage of female participants compared to males in the lonely only, both lonely and socially isolated, or neither groups. Only the socially isolated only group had a higher percentage of males (55.0%, 792/1,439 vs. 45.0%, 647/1,439). Finally, there were no significant differences by other factors including minority designation, median household income, or RUCA.

Loneliness and SNI scores

Unadjusted, bivariate results for quantitative characteristics are displayed in . Of survey participants who were both lonely and socially isolated, a higher mean UCLA-3 Loneliness score (mean = 6.96, SD = 1.11) was observed along with a lower SNI (mean = 2.83, SD = 1.1) on average compared to the other three groups. In contrast, participants with neither loneliness nor social isolation had a lower UCLA-3 Loneliness score (mean = 3.78, SD = 0.67) and higher SNI (mean = 7.26, SD = 1.87).

Healthcare utilization and costs

Approximately 30% of respondents on average had an ER visit within the past year, while only 12% had an IP hospitalization (). Unadjusted analyses revealed a higher percentage of ER visits on average among participants who were either lonely only (34%) or both lonely and socially isolated (34%) compared to neither (29%), while those who were socially isolated had a much lower percentage of ER visits on average (26%). Participants who were both lonely and socially isolated had the highest percentage of IP admissions (18%), as well as the highest total medical cost (mean=$13,008, SD=$17,137).

When controlling for multiple sociodemographic characteristics and health status, participants who were socially isolated were significantly less likely to have an ER visit (OR = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.72, 0.95) compared to participants who were neither (). Participants who were both lonely and socially isolated were also more likely to have an IP admission (OR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.72) compared those who were neither. Finally, participants who were both lonely and socially isolated had greater medical costs in adjusted models; however, the difference was only marginal with a p-value of 0.060.

Table 3. Adjusted association between healthcare utilization and social isolation and loneliness (N = 6,994).

Quality of life

Mental well-being as indicated by the VR-12 measures showed that participants who were both lonely and socially isolated had lower scores on average (mean = 43.2, SD = 11.1) compared to participants in the socially isolated group (mean = 54.7, SD = 8.7) or neither group (mean = 56.8, SD = 6.4) in bivariate analyses (). Interestingly, socially isolated only participants had the lowest average physical well-being score (mean = 38.5, SD = 12.5) as compared to the other three groups. When adjusting for demographic characteristics and health status, this relationship remained consistent (). Finally, for both mental and physical well-being, participants who were both lonely and socially isolated had significantly lower scores, followed by those who were lonely only, and then those who were socially isolated only.

Table 4. Adjusted association between healthcare cost, quality of life, and social isolation and loneliness (N = 6,994).

Discussion

In recent months, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the critical need for interventions to address loneliness and social isolation among vulnerable older adults (Health Affairs 2020). Guidelines during the pandemic have recommended that older adults stay home as much as possible to avoid the risk of serious illness. While these recommendations are warranted, the lasting impacts of physical and social distancing on older adults’ mental health could be significant, including increased loneliness and social isolation (Wu, Citation2020).

In this study conducted in 2018–2019 prior to the pandemic, we observed greater risks among participants experiencing both constructs compared to those with either loneliness, social isolation, or neither. Specifically, we determined that nearly 40% of participants were either lonely, socially isolated, or both, similar to prevalence rates published elsewhere (Cudjoe et al., Citation2020; NASEM Citation2020; Perissinotto et al., Citation2012). Notably, 9.1% of all participants in the current study were classified as both lonely and socially isolated, which is important considering that most previous studies have focused on the distribution of those who are either versus both (NASEM Citation2020).

Our key findings align with previous studies assessing the impacts of loneliness or social isolation separately (Dickens et al., Citation2011; Musich et al., Citation2015; Ong et al., Citation2016; Steptoe et al., Citation2013); for instance, emerging evidence has suggested that social isolation and loneliness can have a negative effect on QOL (Musich et al., Citation2015; NASEM Citation2020). However, our results demonstrate that the cumulative effect may be greater than just one factor alone. In fact, the negative impact on selected health outcomes including QOL was more pronounced in participants who were both lonely and socially isolated compared to those who were only lonely, only socially isolated, or neither.

Aside from the health indicators of loneliness and social isolation, both conditions may also significantly impact healthcare utilization and medical costs; however, research on these outcomes has been limited, with mixed results. We observed that participants who were both lonely and socially isolated had the highest rate of ER visits compared to participants who were socially isolated only, or neither. However, those who were only socially isolated versus both had significantly fewer ER visits, perhaps suggesting a consequence of decreased outings from home among socially isolated older adults. Finally, we observed that participants who were both lonely and socially isolated had a higher rate of IP admissions, supporting previous studies demonstrating that both loneliness and social isolation are associated with increased hospitalizations among older adults (Gerst-Emerson & Jayawardhana, Citation2015; Greysen et al., Citation2013; Jakobsson et al., Citation2011).

One noteworthy study examined the medical costs associated with experiencing loneliness or social isolation as compared to having neither. Researchers found that socially isolated people incurred higher annual healthcare expenses compared to those with greater social networks (Shaw et al., Citation2017). Further, researchers concluded that social isolation, and not loneliness, was significantly associated with higher costs in adjusted analyses including both as predictors. In our study, we found that participants who were both lonely and social isolated had higher medical costs; however, the finding was only marginally significant after controlling for demographic characteristics and health status.

Various intervention strategies to address loneliness and social isolation have been attempted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Cacioppo et al., Citation2015; Masi et al., Citation2011). Common interventions have included efforts to improve social skills, social support, and provide opportunities for social interaction (MacLeod et al., Citation2018). In addition, interventions focused on volunteering, physical activity, community engagement, and others integrating multi-dimensional components have shown potential effectiveness and feasibility among older adults (MacLeod et al., Citation2018; Musich et al., Citation2015).

The most successful interventions have included several key factors in combination, including active participation of participants, integration of education and/or skills training, and group interaction (NASEM Citation2020).

Despite these strategic efforts, the subjective nature of loneliness may require a more cognitive-based approach of intervention as compared to social prescribing or skill-building that may be more beneficial for social isolation. However, few studies have demonstrated strong evidence of a significant and lasting effect on loneliness (NASEM Citation2020). Elsewhere, efforts to address loneliness and social isolation through mindfulness strategies have been attempted, showing in certain cases that individuals who receive mindfulness training subsequently report reduced loneliness (Gilmartin et al., Citation2017; Lindsay et al., Citation2019; Tkatch et al. Citation2020). However, the potential of mindfulness intervention strategies to improve both loneliness and social isolation remains unproven; thus, further research is warranted to examine the impact on each construct.

The key strengths of this study include results from a large random sample of older adults in the US, as compared to similar studies performed in other countries (NASEM Citation2020). In addition, this research provides assessment of both loneliness and social isolation in one analysis, utilizing robust data encompassing both psychosocial and claims-based measures. As such, this study adds to growing evidence on the importance of maintaining strong social connections to support optimal health outcomes within older age groups.

This study has some limitations, including a low response rate, and potential vulnerability to unaccounted selection bias. Further, this study was conducted in a population of AARP Medicare Supplement insureds which may not generalize to all older adults or other Medicare Supplement beneficiaries in the US Although this study utilized a randomized sampling methodology including assessment of respondents and non-respondents, there still could be some unaccounted bias. That said, our response rate of 27% is comparable and not uncommon in mailed surveys conducted among older adults (Edelman et al., Citation2013). Other limitations include the metrics capturing loneliness and social isolation. Although, the ULCA-3 Loneliness Scale and the SNI have been validated and successfully used in many studies, there is potential for misclassification bias due to the nature of the survey questions and recall bias by study participants. In addition, older age can affect self-report responses due to changes in cognitive and communicative functioning (Knäuper et al., Citation2016). Meanwhile, we did not have a full assessment of depression, which has been found to be highly associated with both constructs. For this reason, analyses were limited when using the PHQ-2. Finally, classification of participants into ‘lonely’ and ‘socially isolated’ groups is just one of several potential options of assessment. Altering the classification of loneliness or social isolation could impact the magnitude of associations. Future analyses could explore different cut points and continuous metrics.

In this study, we sought to explore the cumulative effect of both loneliness and social isolation among older adults. Previous studies have addressed these constructs separately or interchangeably, despite the different definitions and approaches needed. In this study, we observed greater risks among participants who were both lonely and socially isolated, demonstrating the potential combined negative outcomes of these two constructs later in life. Ultimately, interventions addressing both loneliness and social isolation in combination could have a substantial impact within this population.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aung, M. N., Moolphate, S., Aung, T. N. N., Kantonyoo, C., Khamchai, S., & Wannakrairot, P. (2016). The social network index and its relation to later-life depression among the elderly aged 80 years in Northern Thailand. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 11, 1067–1074. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S108974

- Barth, J., Schneider, S., & von Kanel, R. (2010). Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72(3), 229–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d01611

- Bassuk, S. S., Glass, T. A., & Berkman, L. F. (1999). Social disengagement and incident cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly persons. Annals of Internal Medicine, 131(3), 165–173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-131-3-199908030-00002

- Beller, J., & Wagner, A. (2018a). Loneliness, social isolation, their synergistic interaction, and mortality. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 37(9), 808–813. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000605

- Beller, J., & Wagner, A. (2018b). Disentangling loneliness: Differential effects of subjective loneliness, network quality, network size, and living alone on physical, mental, and cognitive health. Journal of Aging and Health, 30(4), 521–539. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264316685843

- Beutel, M. E., Klein, E. M., Brähler, E., Reiner, I., Jünger, C., Matthias, M., Wiltink, J., Wild, P. S., Münzel, T., Lackner, K. J., & Tibubos, A. N. (2017). Loneliness in the general population: Prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1262-x

- Cacioppo, S., Grippo, A. J., London, S., Goossens, L., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Loneliness: Clinical import and interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10(2), 238–249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615570616

- Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Crawford, L. E., Ernst, J. M., Burleson, M. H., Kowalewski, R. B., Malarkey, W. B., Van Cauter, E., & Berntson, G. G. (2002). Loneliness and health: Potential mechanisms. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(3), 407–417. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200205000-00005

- Charlson, M. E., Pompei, P., Ales, K. L., & MacKenzie, C. R. (1987). A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 40(5), 373–383. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- Cornwell, E. Y., & Waite, L. J. (2009). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650905000103

- Courtin, E., & Knapp, M. (2017). Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: a scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 799–812. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12311

- Cudjoe, T. K. M., Roth, D. L., Szanton, S. L., Wolff, J. L., Boyd, C. M., & Thorpe, R. J.Jr., (2020). The epidemiology of social isolation: National Health and Aging Trends Study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(1), 107–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby037

- Dickens, A. P., Richards, S. H., Greaves, C. J., & Campbell, J. L. (2011). Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 11, 647. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-647

- Donovan, N. J., & Blazer, D. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Review and commentary of National Academies Report. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(12), 1233–1244. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.005

- Donovan, N. J., Wu, Q., Rentz, D. M., Sperling, R. A., Marshall, G. A., & Glymour, M. M. (2017). Loneliness, depression and cognitive function in older U.S. adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(5), 564–573. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4495

- Drageset, J., Eide, G. E., Kirkevold, M., & Ranhoff, A. H. (2013). Emotional loneliness is associated with mortality among mentally intact nursing home residents with and without cancer: A five-year follow-up study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(1-2), 106–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04209.x

- Edelman, L. S., Yang, R., Guymon, M., & Olson, L. M. (2013). Survey methods and response rates among rural community dwelling older adults. Nursing Research, 62(4), 286–291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182987b32

- Gerst-Emerson, K., & Jayawardhana, J. (2015). Loneliness as a public health issue: The impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. American Journal of Public Health, 105(5), 1013–1019. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302427

- Gilmartin, H., Goyal, A., Hamati, M. C., Mann, J., Saint, S., & Chopra, V. (2017). Brief mindfulness practices for healthcare providers—A systematic literature review. The American Journal of Medicine, 130(10), 1219.e1–1219.e17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.05.041

- Grant, N., Hamer, M., & Steptoe, A. (2009). Social isolation and stress-related cardiovascular, lipid, and cortisol responses. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 37(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9081-z

- Greysen, S. R., Horwitz, L. I., Covinsky, K. E., Gordon, K., Ohl, M. E., & Justice, A. C. (2013). Does social isolation predict hospitalization and mortality among HIV + and uninfected older veterans?Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(9), 1456–1463. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12410

- Hackett, R. A., Hamer, M., Endrighi, R., Brydon, L., & Steptoe, A. (2012). Loneliness and stress-related inflammatory and neuroendocrine responses in older men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(11), 1801–1809. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.03.016

- Hakulinen, C., Pulkki-Råback, L., Virtanen, M., Jokela, M., Kivimäki, M., & Elovainio, M. (2018). Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for myocardial infarction, stroke and mortality: UK Biobank cohort study of 479,054 men and women. Heart, 104(18), 1536–1542. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312663

- Hawker, M., & Romero-Ortuno, R. (2016). Social determinants of discharge outcomes in older people admitted to a geriatric medicine ward. The Journal of Frailty & Aging, 5(2), 118–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2016.89

- Hawkley, L. C., Thisted, R. A., Masi, C. M., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness predicts increased blood pressure: 5-year cross-lagged analyses in middle-aged and older adults. Psychology and Aging, 25(1), 132–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017805

- Health Affairs. (2020, June 22). The double pandemic of social isolation and COVID-19: Cross-sector policy must address both. Health Affairs Blog.

- Heffner, K. L., Waring, M. E., Roberts, M. B., Eaton, C. B., & Gramling, R. (2011). Social isolation, C-reactive protein, and coronary heart disease mortality among community-dwelling adults. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 72(9), 1482–1488. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.016

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Robles, T. F., & Sbarra, D. A. (2017). Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. American Psychologist, 72(6), 517–530. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000103

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & D. Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A metanalytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

- Holwerda, T. J., Deeg, D. J., Beekman, A. T., van Tilburg, T. G., Stek, M. L., Jonker, C., & Schoevers, R. A. (2014). Feelings of loneliness, but not social isolation, predict dementia onset: Results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL). Journal of Neurology. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 85(2), 135–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2012-302755

- Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results form two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504268574

- Jakobsson, U., Kristensson, J., Hallberg, I. R., & Midlöv, P. (2011). Psychosocial perspectives on health care utilization among frail elderly people: An explorative study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 52(3), 290–294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2010.04.016

- Kelly, M. E., Duff, H., Kelly, S., McHugh Power, J. E., Brennan, S., Lawlor, B. A., & Loughrey, D. G. (2017). The impact of social activities, social networks, social support and social relationships on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: A systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0632-2

- Knäuper, B., Carrière, K., Chamandy, M., Xu, Z., Schwarz, N., & Rosen, N. O. (2016). How aging affects self-reports. European Journal of Ageing, 13(2), 185–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-016-0369-0

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41(11), 1284–1292. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

- Kuiper, J. S., Zuidersma, M., Oude Voshaar, R. C., Zuidema, S. U., van den Heuvel, E. R., Stolk, R. P., & Smidt, N. (2015). Social relationships and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Research Reviews, 22, 39–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2015.04.006

- Lindsay, E. K., Young, S., Brown, K. W., Smyth, J. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2019). Mindfulness training reduces loneliness and increases social contact in a randomized controlled trial. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(9), 3488–3493. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1813588116

- Luo, Y., & Waite, L. J. (2014). Loneliness and mortality among older adults in China. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(4), 633–645. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbu007

- MacLeod, S., Musich, S., Parikh, R. B., Hawkins, K., Keown, K., & Yeh, C. S. (2018). Examining approaches to address loneliness and social isolation among older adults. Journal of Aging and Geriatric Medicine, 2(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4172/2576-3946.1000115

- Masi, C. M., Chen, H. Y., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2011). A metaanalysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(3), 219–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310377394

- Musich, S., Wang, S. S., Hawkins, K., & Yeh, C. S. (2015). The impact of loneliness on quality of life and patient satisfaction among older, sicker adults. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 1, 233372141558211.

- Musich, S., Wang, S. S., Slindee, L., Kraemer, S., & Yeh, C. S. (2019). Association of resilience and social networks with pain outcomes among older adults. Population Health Management, 22(6), 511–521.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) (2020). Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17226/25663

- Ong, A. D., Uchino, B. N., & Wethington, E. (2016). Loneliness and health in older adults: A Mini-review and synthesis. Gerontology, 62(4), 443–449. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1159/000441651

- Perissinotto, C. M., Stojacic Cenzer, I., & Covinsky, K. E. (2012). Loneliness in older persons: A predictor of functional decline and death. Arch Intern Med, 72, 1078–1084.

- Selim, A. J., Rogers, W., Fleishman, J. A., Qian, S. X., Fincke, B. G., Rothendler, J. A., & Kazis, L. E. (2009). Updated US population standard for the Veterans RAND 12-item Health Survey (VR-12). Quality of Life Research, 18(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-008-9418-2

- Shankar, A., Hamer, M., McMunn, A., & Steptoe, A. (2013). Social isolation and loneliness: Relationships with cognitive function during 4 years of follow-up in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychosomatic Medicine, 75(2), 161–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31827f09cd

- Shankar, A., McMunn, A., Banks, J., & Steptoe, A. (2011). Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 30(4), 377–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022826

- Shaw, J. G., Farid, M., Noel-Miller, C., Joseph, N., Houser, A., Asch, S. M., Bhattacharya, J., & Flowers, L. (2017). Social isolation and Medicare spending: Among older adults, objective isolation increases expenditures while loneliness does not. Journal of Aging and Health, 29(7), 1119–1143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264317703559

- Stathi, A., Withall, J., Thompson, J. L., Davis, M. G., Gray, S., De Koning, J., Parkhurst, G., Lloyd, L., Greaves, C., Laventure, R., & Fox, K. R. (2020). Feasibility trial evaluation of a peer volunteering active aging intervention: ACE (Active, Connected, Engaged). The Gerontologist, 60(3), 571–582. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz003

- Steptoe, A., Owen, N., Kunz-Ebrecht, S. R., & Brydon, L. (2004). Loneliness and neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory stress responses in middle-aged men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(5), 593–611. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00086-6

- Steptoe, A., Shankar, A., Demakakos, P., & Wardle, J. (2013). Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(15), 5797–5801.

- Sundararajan, V., Henderson, T., Perry, C., Muggivan, A., Quan, H., & Ghali, W. A. (2004). New ICD-10 version of the Charlson comorbidity index predicted in-hospital mortality. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 57(12), 1288–1294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.03.012

- Tkatch, R., Wu, L., Mac Leod, S., Ungar, R., Albright, L., Russell, D., Murphy, J., schaeffer, J., & Yeh, C. S. (2020). Reducing loneliness and improving well-being among older adults with animatronic pets. Aging & Mental Health. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1758906

- Valtorta, N. K., Moore, D. C., Barron, L., Stow, D., & B. Hanratty, B. (2018). Older adults’ social relationships and health care utilization: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 108(4), e1–e10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304256

- Wilson, R. S., Krueger, K. R., Arnold, S. E., Schneider, J. A., Kelly, J. F., Barnes, L. L., Tang, Y., & D. A. Bennett, D. A. (2007). Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(2), 234–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.234

- Wu, B. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness among older adults in the context of COVID-19: A global challenge. Global Health Research and Policy, 5, 27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-020-00154-3