Abstract

Objectives

To investigate whether latent subgroups with distinct patterns of factors associated with self-rated successful aging can be identified in community-dwelling adults, and how such patterns obtained from analysis of quantitative data are associated with lay perspectives on successful aging obtained from qualitative responses.

Methods

Cross-sectional data were collected from 1,510 community-dwelling Americans aged 21–99 years. Latent class regression was used to identify subgroups that explained the associations of self-rated successful aging with measures of physical, cognitive, and mental health as well as psychological measures related to resilience and wisdom. Natural language processing was used to extract important themes from qualitative responses to open-ended questions, including the participants’ definitions of successful aging.

Results

Two latent subgroups were identified, and their main difference was that the wisdom scale was positively associated with self-rated successful aging in only one subgroup. This subgroup had significantly lower self-rated successful aging and worse scores for all health and psychological measures. In the subgroup’s qualitative responses, the theme of wisdom was only mentioned by 10.6%; this proportion was not statistically different from the other subgroup, for which the wisdom scale was not statistically associated with the self-rated successful aging.

Conclusion

Our results showed heterogeneous patterns in the factors underpinning successful aging even in community-dwelling adults. We found the existence of a latent subgroup with lower self-rated successful aging as well as worse health and psychological scores, and we suggest a potential role of wisdom in promoting successful aging for this subgroup, even though individuals may not explicitly recognize wisdom as important for successful aging.

Introduction

As the world’s population of older adults increases, there is growing interest in understanding how to achieve successful aging. Understanding of the factors that underpin successful aging has been expected to provide variable information on modifiable factors to promote successful aging and improve related public policy (Eaton et al., Citation2012; Jeste et al., Citation2013; Pruchno et al., Citation2010). successful aging has traditionally been characterized by using an operationalized biomedical definition based on objective measures of having less disease and disability, a high level of cognitive and physical function, and active social engagement (Depp & Jeste, Citation2006; Rowe & Kahn, Citation1987, Citation1997). As a complementary line of research on these objective and biomedical definitions, subjectively determined successful aging has also been investigated (Cosco et al., Citation2013; Feng & Straughan, Citation2017; Jeste et al., Citation2013; Jopp et al., Citation2015; Montross et al., Citation2006; Pruchno et al., Citation2010). Subjective successful aging has often been reported to differ from the successful aging of a biomedical model (Cernin et al., Citation2011; Cosco et al., Citation2013; Feng & Straughan, Citation2017; Pruchno et al., Citation2010): in particular, even individuals with disability and disease, who are categorized as unsuccessful by the biomedical definition, have reported aging well (Marengoni et al., Citation2011; Montross et al., Citation2006; Romo et al., Citation2013). Thus, understanding the factors underpinning subjective successful aging may help facilitate person-centered interventions and policy reforms that are congruent with lay perceptions of successful aging (Bowling, Citation2006; Jeste et al., Citation2013; Jopp et al., Citation2015; Reichstadt et al., Citation2010). Such understanding has also been expected to help individuals to assign appropriate weights to the factors important for successful aging in view of their personal goals and preferences and to contextualize those factors within the overall trajectory of their past and anticipated future life (Jeste et al., Citation2013). From this perspective, some studies have extended the usual focus on older adults by including middle-aged or young individuals and investigating important factors for their subjective successful aging, as well (Bowling, Citation2006; Jopp et al., Citation2015).

Studies on factors associated with subjective successful aging have shown divergence from traditional biomedical conceptualizations, highlighting the multidimensionality and importance of psychological factors in addition to health factors such as physical and mental health and cognitive function (Cosco et al., Citation2013; Jeste et al., Citation2013; Jopp et al., Citation2015). In particular, resilience and wisdom are posited to be important psychological factors for successful aging, because they are associated with positive psychological traits and inner strengths that have important roles in how individuals adapt to adversity and disability (Ardelt, Citation2003; Jeste et al., Citation2013; Lamond et al., Citation2008; Lee, Citation2019). A number of studies have also explored how these successful aging perceptions are influenced by other factors such as different countries, cultures, and socioeconomic conditions (Bowling, Citation2006; Feng et al., Citation2015; Feng & Straughan, Citation2017; Golja et al., Citation2020; Jopp et al., Citation2015). For example, cultural variation in views on successful aging has been actively investigated, and studies have reported some cultural differences, especially when comparing Eastern or Asian and Western cultures (Feng & Straughan, Citation2017; Iwamasa & Iwasaki, Citation2011; Jopp et al., Citation2015; Laditka et al., Citation2009). Moreover, the cultural specificity of successful aging has been reported even within the same country: a study on the culturally specific meaning of successful aging in Singapore, an ethnically diverse city-state in Asia, found four subgroups with different patterns of successful aging perceptions (Feng & Straughan, Citation2017). Health status has also been suggested to influence perceptions of successful aging (Escota et al., Citation2018; Molton & Yorkston, Citation2017; Rasmussen et al., Citation2020). For example, a study on individuals with physical disabilities emphasized factors related to psychological resilience and adaptation as important differences from individuals without such disabilities among successful aging perceptions (Molton & Yorkston, Citation2017). Health-related changes including functional decline, disability, and chronic disease are common in older adults: for instance, 45% of individuals tend to have two or more chronic health conditions by their late 60 s (Freid et al., Citation2012), and only 15% reported an absence of physical illness and disability in a survey questionnaire study on a community sample of older adults (Montross et al., Citation2006). Given the heterogeneity in health status, even populations with similar cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds (e.g. community-dwelling adults) may have subgroups that demonstrate different patterns of successful aging perceptions, particularly in terms of psychological factors such as resilience and wisdom that are related to the ability to adapt positively to adversity. Such explorations are still limited but may help identify more precise, modifiable factors to promote successful aging for personalized interventions.

Qualitative studies have expanded and complemented the conceptualizations of subjective successful aging by incorporating layperson perspectives through interviews. These studies emphasize the importance of psychological factors in successful aging models in addition to health factors (Cosco et al., Citation2013; Jopp et al., Citation2015). In fact, according to a review article, psychosocial factors were the most frequently mentioned components of successful aging (Cosco et al., Citation2013). Quantitative studies have investigated factors associated with subjective successful aging and suggested specific psychological components such as resilience as potential modifiable factors for promoting successful aging (Bowling & Iliffe, Citation2011; Jeste et al., Citation2013; Lamond et al., Citation2008). On the other hand, in qualitative studies, such specific psychological components (e.g. a positive attitude) tend not to be mentioned often by laypeople: for example, they were mentioned by at most one fifth of the laypeople in previous studies (Jopp et al., Citation2015; Tate et al., Citation2003). There is currently no study on direct comparison of the important factors for subjective successful aging obtained from both qualitative and quantitative data collected from the same large sample of participants; however, such comparison would provide insight into specific psychological components that individuals do not explicitly recognize as important for their own successful aging. Because qualitative studies have typically investigated individuals’ interview responses about successful aging via manual coding (Cosco et al., Citation2013; Jopp et al., Citation2015; Reichstadt et al., Citation2010), large-scale investigations have been difficult to perform. Accordingly, the use of natural language processing (NLP) to extract underlying factors of successful aging from qualitative responses may help researchers investigate larger samples. Such NLP analysis on qualitative data may also be useful for detecting subgroups with different perceptions of subjective successful aging as obtained from analysis of quantitative data, if these subgroups have different profiles of health status related to cognitive function and mental health, for example. Specifically, linguistic characteristics such as reduced vocabulary richness and fewer positive emotion words have been reported as significant indicators of lower cognitive function and higher levels of depression, respectively (Fraser et al., Citation2016; Ramirez-Esparza et al., Citation2008; Rude et al., Citation2004; Scibelli, Citation2019). Enabling to identify subgroups with different perceptions of subjective successful aging from both quantitative and qualitative data would broaden the scope of application for personalized intervention.

Here, we aimed to investigate whether latent subgroups with distinct patterns of factors associated with self-rated successful aging can be identified in community-dwelling adults. We also sought to examine how these patterns obtained from quantitative data analysis are associated with lay perspectives on successful aging obtained from qualitative responses. To these ends, for a community-based sample of young, middle-aged, and older adults, we investigated both quantitative data on self-rated successful aging and health and psychological measures and qualitative data from responses to open-ended questions about successful aging. Given the heterogeneity of individuals’ health status as well as its impact on their perceptions of successful aging, we hypothesized that subgroups with different patterns of factors underpinning subjective successful aging, especially in terms of psychological factors such as resilience and wisdom, would exist even within community-dwelling adults. On the basis of previous qualitative studies, we also hypothesized the existence of psychological factors that individuals do not explicitly recognize as important for their subjective successful aging. Finally, we hypothesized that these subgroups would have different linguistic characteristics in their responses to open-ended questions if they had different profiles in terms of cognitive function and mental health.

Methods

Participants

The participants were 1,549 community-dwelling adults, aged 21–99 years, from the University of California (UC) San Diego Successful Aging Evaluation (SAGE) study (Jeste et al., Citation2013; Martin et al., Citation2015; Thomas et al., Citation2016). A structured multi-cohort design was used to recruit residents of San Diego County through random digit dialing, with nearly equal numbers of men and women, stratification by age decade, and an oversampling of adults over age 75 (because of the increased risk of drop-outs) (Jeste et al., Citation2013; Martin et al., Citation2015; Thomas et al., Citation2016). All participants were capable of providing informed consent and physically and mentally able to participate in survey measurements. See the Supplementary Methods for more details about data collection including exclusion criteria. The study was approved by UC San Diego’s Institutional Review Board, protocol number 171635.

Self-rated successful aging and qualitative responses

On the basis of the previously established method (Montross et al., Citation2006), the participants were asked to rate the degree to which they thought they had aged successfully, on a 10-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (least successful) to 10 (most successful). The participants were instructed to use their own conceptualization of successful aging rather than any investigator-defined construct.

To assess themes related to successful aging, we also collected unstructured written responses to the following three open-ended questions: (1) ‘How would you define successful aging?’ (2) ‘Think of someone whom you consider to be ‘aging successfully’. To what do you attribute their success?’ (3) ‘What do you like about yourself?’

Health and psychological measures

Measures of the participants’ physical health, cognitive function, and mental health as well as psychological measures of their resilience and wisdom were collected as part of the mail-in survey, except where otherwise indicated. The only exception (Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-M) (de Jager et al., Citation2003)) was collected as part of the initial telephone screening. A detailed description of the full SAGE survey is available in our previous study (Jeste et al., Citation2013).

The present study used seven key measures, as follows. The participants’ current physical and mental health functioning were assessed with the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36-PC and SF-36-MC) (Ware & Sherbourne, Citation1992). In addition to the objective cognitive function assessed by TICS-M, the subjective cognitive function was examined with the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) (Broadbent et al., Citation1982). The severity of depressive symptoms was evaluated with the nine-item version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., Citation2001). For the psychological measures, resilience referred to ready recovery from or positive adaptation in the face of adversity, and it was assessed with the 10-item version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) (Campbell-Sills & Stein, Citation2007). Wisdom was assessed by using the three-dimensional wisdom scale (3 D wisdom) conceptualized by Ardelt as consisting of three distinct, interrelated dimensions: cognitive (ability to understand a situation thoroughly, knowledge of the positive and negative aspects of human nature, and awareness of life’s inherent uncertainty while retaining the ability to make decisions in spite of this), reflective (ability and willingness to examine phenomena from multiple perspectives, and absence of projection or blaming of others for one’s own situation or feelings), and affective (positive emotions and behaviors with an absence of indifferent or negative emotions toward others, while remaining positive in the face of adversity) (Ardelt, Citation2003).

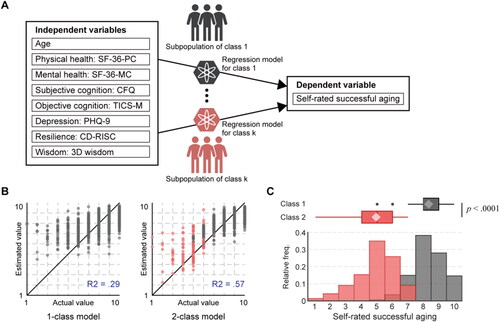

Data analysis

Latent class regression (LCR) (Bandeen-Roche et al., Citation1997) was performed using FlexMix (version 2.3.17) (Leisch, Citation2004) to investigate whether the factors associated with successful aging were homogenous across all participants, or whether the pattern of these factors differed across participants to the extent that latent classes (i.e. subgroups) of participants better represented the data. Traditional regression analysis assumes that a similar regression coefficient holds true for all participants, but LCR enables identification of distinct latent classes of participants who share similar regression coefficients. The dependent variable was the self-rated successful aging, and the independent variables were age and the aforementioned seven measures of health and psychological factors, as illustrated in . People aged 90 years and older are considered more easily identifiable; therefore, to protect the confidentiality of this population, the LCR analysis was performed with a maximum default age of 89. In all other analyses including statistical analysis, the actual ages were used. To select the optimal number of latent classes, we used the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (see the Supplementary Methods for more details).

Figure 1. Overview of the LCR analysis. A. Independent and dependent variables for the LCR analysis. B. Regression results of the one- and two-class models to estimate the self-rated successful aging score. The colors for the two-class model represent the participant’s class: grey for class 1, red for class 2. C. Histogram of the self-rated successful aging scores for each class, using the same colors as in B.

We automatically extracted themes mentioned by the participants from the text data of the responses to the three open-ended questions about successful aging; then, we investigated the proportion of the total sample that reported each theme. Specifically, we used Empath (version 0.89) (Fast et al., Citation2016) on Python (version 3.8) to generate sets of words and phrases related to specific themes, and we determined whether participants mentioned each theme (see the Supplementary Methods for more details). In addition to themes related to the assessment measures, we investigated five themes that were reported as the most frequently mentioned across countries, including the US, in a previous study using manual coding (Jopp et al., Citation2015): health, social resource, activity/interest, well-being, and virtue/attitude/belief. The participants’ responses were anonymized by removing identifiable information such as proper names, and all the responses were combined for the analysis from the NLP perspective. The text data were also characterized by linguistic features related to cognitive impairments (Fraser et al., Citation2016; Kavé & Goral, Citation2016): specifically, Honoré’s statistic to measure vocabulary richness (Honoré, Citation1979), the number of long words to measure syntactic complexity (Kavé & Goral, Citation2016), and the number of nouns. These features are fully described in the Supplementary Methods.

For missing values, multivariate imputation by chained equations (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, Citation2011) was performed using all non-missing data. To assess the differences in each variable between classes, we used two-sided Student’s t-tests for continuous data and chi-squared tests for categorical data. A conservative threshold of p < .01 was applied to account for multiple comparisons.

Results

Among the 1,549 participants, 39 were excluded from this analysis because of missing self-rated successful aging data. summarizes the sociodemographic and other characteristics related to successful aging The overall sample had a mean age of 65.8 years (SD: 21.0; range: 21–99), and the mean score for the self-rated successful aging was 8.0 (SD: 1.5). For information on the missing data, see the Supplementary Results and .

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics and aspects of successful aging.

The model fitting results of the LCR analyses for the one- to five-class models are presented in . Bootstrapping analysis showed that the two-class model was a statistically better fit to the data than the one-class model, and the three-class model was a statistically better fit than the two-class model (p < .001). Both the four- and five-class models did not show any improvement than the models with one less class, respectively (p = .262 and p = .056, respectively). In addition, the two-class model had the lowest BIC value among the five models. From the both perspectives of the bootstrap likelihood ratio test and BIC, we concluded that the two-class model was the most optimal representation of the data. Classes 1 and 2 consisted of 90.5% (N = 1,367) and 9.5% (N = 143) of the participants, respectively. This model accounted for 57% of the variance of the self-rated successful aging, as seen in .

Table 2. Model fit statistics of the latent class regression analyses for the one- to five-class models.

The estimated regression coefficients for the two-class LCR are listed in . In both classes, older age, higher self-rated physical health, and higher resilience were statistically associated with a higher self-rated successful aging, while both subjective and objective cognitive function were not statistically associated. Regarding the difference between the two classes, the level of depression was statistically associated with the self-rated successful aging in class 1, while the self-rated mental health and wisdom scales were statistically associated in class 2. Because the measures for depression and mental health were different but closely correlated with each other (r = −0.63, N = 1,401, p < .001 in this study), the main difference between the two subgroups was the presence or absence of the wisdom scale’s association with the self-rated successful aging ().

Table 3. Estimated regression coefficients for the two-class latent class regression model to predict self-rated successful aging.

We also examined differences between the two classes in terms of the sociodemographic characteristics and aspects of successful aging (). There was no statistical difference between the two classes in the sociodemographic measures of gender, age, race, marital status, living status, and education (p ≥ .01). In contrast, we found statistical differences in the self-rated successful aging as well as all health and psychological measures (p < .01). Class 2 showed statistically lower self-rated successful aging values (p < .001), as shown in , and worse scores for all other measures: self-rated physical and mental health, subjective and objective cognitive function, resilience, and levels of depression and wisdom (p < .01). Hereinafter, we refer to class 2 as the lower-successful-aging subgroup.

We next investigated how these patterns obtained from quantitative data were associated with the lay perspectives on successful aging obtained from the qualitative responses. Specifically, we investigated the proportions of individuals reporting specific themes and compared them between the two latent subgroups, as summarized in . For the top five themes reported in a previous study using manual coding (Jopp et al., Citation2015), we found similar trends in the proportions of our samples obtained by NLP analysis: more than one third of the participants mentioned each of these themes, namely, health (62.4%), social resource (48.2%), activity/interest (34.6%), well-being (34.2%) and virtue/attitude/belief (33.6%), As for the themes investigated in the LCR analysis of the quantitative data, the theme of physical occurred most often (36.3%), followed by the themes of mental (26.7%) and aging (16.6%). Other themes were mentioned by less than 15% of the participants: wisdom (13.9%), resilience (10.0%), depression (6.7%), and cognitive (2.0%). We did not find any statistical differences between the two subgroups in the proportions mentioning any of the themes investigated in this study (p > .01). Although the wisdom scale was statistically associated with the self-rated successful aging in the lower-successful-aging subgroup, the theme of wisdom was mentioned by only 10.6% of the participants in that subgroup; this proportion did not differ from that in the other subgroup, for which wisdom was not statistically associated with the self-rated successful aging.

Table 4. Proportions of individuals reporting specific themes in response to open-ended questions about successful aging.

Next, we investigated whether there were discernible differences between the two subgroups in their responses to the open-ended questions about successful aging. To do so, we compared the subgroups in terms of linguistic features shown by previous studies to be significant indicators of cognitive impairments and depressive symptoms, because the lower-successful-aging subgroup had worse scores for subjective and objective cognitive function and higher severity of depression. As seen in , individuals in the lower-successful-aging subgroup statistically had lower vocabulary richness as measured by Honoré’s statistic, lower syntactic complexity as measured by the number of long words, and less use of nouns (p < .01). Furthermore, the trends for these individuals were consistent with those observed in individuals with cognitive impairments (Fraser et al., Citation2016; Kavé & Goral, Citation2016). The lower-successful-aging subgroup also had statistically lower proportions of individuals mentioning positive emotion words and affection words (p < .005), which was also consistent with the trends observed in individuals with depressive symptoms (Ramirez-Esparza et al., Citation2008; Rude et al., Citation2004; Scibelli, Citation2019).

Table 5. Linguistic characteristics in the responses to the open-ended questions about successful aging.

Discussion

Our first main finding, from LCR analysis of the quantitative data, was that two subgroups with distinct patterns of factors associated with their self-rated successful aging could be identified even within a sample of community-dwelling Americans. The main difference between the two subgroups was that the wisdom scale was positively associated with the self-rated successful aging in only one of them. This subgroup, labeled as the lower-successful-aging subgroup, had statistically lower self-rated successful aging as well as worse health and psychological scores as compared with the other subgroup.

Our second main finding, from NLP analysis of the qualitative data, was that the theme of wisdom was mentioned by only 10.6% of the individuals in the lower-successful-aging subgroup, even though it was statistically associated with their self-rated successful aging. In addition, this proportion did not differ from that in the other subgroup, for which wisdom was not statistically associated with successful aging. These results suggest that individuals in the lower-successful-aging subgroup may not have explicitly recognized wisdom as an important factor for their successful aging, even though our analysis of the quantitative data showed that wisdom was statistically associated with their self-rated successful aging.

The third main finding was that the qualitative responses to the open-ended questions about successful aging had statistically discernible differences between the two subgroups in terms of linguistic features such as vocabulary richness and the frequency of positive emotion words, which indicated lower cognitive function and higher levels of depression in the lower-successful-aging subgroup. This result was consistent with our results on the quantitative assessment data, and it supports our hypothesis that a lower-successful-aging subgroup can be detected from its worse health profile in relation to cognitive function and mental health, from both quantitative and qualitative data. We believe that this approach may help identify individuals who can benefit from targeted interventions to promote successful aging.

Through data-driven identification of the two subgroups, we showed heterogeneous patterns in the factors underpinning successful aging in community-dwelling adults. In both subgroups, older age, higher self-rated physical health, and higher resilience were statistically associated with higher self-rated successful aging, which is consistent with results found in prior research (Cosco et al., Citation2013; Jeste et al., Citation2013). The main difference between the subgroups was that the wisdom scale was statistically positively associated with self-rated successful aging only in the lower-successful-aging subgroup, which was characterized by worse health and psychological scores. Previous studies on individuals with worse health profiles emphasized psychological factors related to how individuals adapt to adversity and disability as important differences from healthy individuals among successful aging perceptions (Molton & Yorkston, Citation2017; Pruchno & Carr, Citation2017). Because wisdom is related to the capability and equanimity to cope with adversity without affecting an individual’s sense of well-being (Ardelt, Citation2003; Ardelt & Jeste, Citation2018; Jeste et al., Citation2010), our results align with those of previous studies and suggest that worse health profiles may affect successful aging perceptions and require higher wisdom levels to achieve successful aging. Because we excluded people in nursing homes or other institutions in this study, our results may also suggest that even subtle changes in health status might affect subjective successful aging perceptions.

Our NLP analysis of the qualitative responses showed similar trends in the mentioned themes to those reported in a previous study using manual coding (Jopp et al., Citation2015). This indicates that NLP can facilitate analysis of large amounts of qualitative data and extraction of important themes related to successful aging. To our knowledge, this is the first study on direct comparison of factors constituting successful aging between quantitative and qualitative data collected from the same large participant sample. As expected according to previous literature (Jopp et al., Citation2015; Tate et al., Citation2003), themes about specific psychological components such as resilience and wisdom were mentioned by less than 15% of participants, even though the scales for measuring those components were statistically associated with self-rated successful aging. Such direct comparison of the factors underpinning subjective successful aging obtained from qualitative and quantitative data may provide unique insights into psychological factors that individuals might not recognize as being important for promoting their successful aging.

An important implication of the present study is that our findings might facilitate the tailoring of interventions for specific subpopulations and the development of personalized interventions to promote successful aging, although no causality could be inferred from our results with cross-sectional data. The results indicate that subgroups with different patterns of successful aging perceptions within community-dwelling Americans may have substantial differences in their health and psychological scores as well as their self-rated successful aging; interestingly, the subgroups did not statistically differ in their sociodemographic characteristics. In particular, differences in health status could be detectable from both quantitative and qualitative data, which would be useful for identifying target subpopulations for personalized interventions in multiple ways. Because the two subgroups in this study showed significantly different scores for the 10-point self-rated successful aging (i.e. 8.3 ± 1.0 vs 4.9 ± 1.3), interventions for the lower-successful-aging subgroup with worse health and psychological scores would be especially important. For this subgroup, our results showed that resilience and wisdom were significantly associated with self-rated successful aging, such that the effect for the combination of resilience and wisdom was comparable to the effect for physical health. Although a longitudinal follow-up study will be needed to determine causal inferences, our results align with those of previous studies pointing to the importance of psychological factors to promote successful aging (Cosco et al., Citation2013; Jeste et al., Citation2013; Molton & Yorkston, Citation2017), and they suggest that increasing resilience and wisdom might have a combined effect on successful aging as strong as the effect of mitigating physical disability. Furthermore, wisdom has been reported to be associated with greater well-being, satisfaction with life, and overall better health (Ardelt, Citation1997; Ardelt & Jeste, Citation2018; Jeste & Lee, Citation2019), and randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis studies showed that wisdom components can be enhanced through psychosocial interventions (Lee et al., Citation2020, Citation2019). Our results suggest that such wisdom-enhancing interventions may be effective in promoting successful aging particularly for the latent subgroup characterized by lower successful aging and worse health scores.

The strengths of this study include its structured multi-cohort design, subject selection using random digit dialing, and use of both qualitative and quantitative data consisting of published, validated measures of various constructs simultaneously. However, the study also has several limitations. First, our analyses were conducted on cross-sectional data; thus, potential causal inferences based on the observed associations are still unknown, e.g. whether increased wisdom would increase self-rated successful aging. Longitudinal follow-up studies will be needed to examine such causal relationships. Second, the most quantitative measures in this study were collected through self-reporting. Although such self-reported measures have been suggested to be correlated with objective values (Dawes et al., Citation2011; Oswald & Wu, Citation2010), a further study with objective measures will be required to confirm our findings. Third, our findings were limited by the data changes to protect anonymity: the alteration of ages 90 years and older for LCR, and the removal of words with identifiable information from the qualitative responses. Results that may have been affected by these changes include positive associations between age and self-rated successful aging as well as trends in the themes mentioned in the qualitative responses, but these results were consistent with the results of previous studies. We thus believe that the changes for anonymity did not alter our main findings. Finally, our sample was from a specific place (San Diego County, California, US), and further studies of this type will be needed in other regions to generalize our findings to communities with different population characteristics.

In conclusion, we have provided the first empirical evidence that even in community-dwelling adults there may be latent subgroups with distinct patterns of factors underpinning their subjective successful aging. Furthermore, one subgroup with worse health and psychological scores showed unique associations of their self-rated successful aging with wisdom, suggesting that worse health profiles may affect successful aging perceptions and require higher wisdom levels to achieve successful aging. Through comparison of the factors underpinning the subjective successful aging obtained from quantitative and qualitative data, we also suggest that wisdom may be an implicit promoter for this subgroup, such that individuals may not explicitly recognize wisdom as important for their successful aging. Future research will be needed to investigate the causal relationship with successful aging through longitudinal follow-up studies or intervention studies.

Disclosure statement

Yasunori Yamada, Kaoru Shinkawa, and Ho-Cheol Kim are employees of IBM Corporation. Keita Shimmei was employed by IBM when this study was conducted. The other authors report no conflict of interest regarding this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ardelt, M. (1997). Wisdom and life satisfaction in old age. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 52B(1), P15–P27. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/52B.1.P15

- Ardelt, M. (2003). Empirical assessment of a three-dimensional wisdom scale. Research on Aging, 25(3), 275–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027503025003004

- Ardelt, M., & Jeste, D. V. (2018). Wisdom and hard times: The ameliorating effect of wisdom on the negative association between adverse life events and well-being. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73(8), 1374–1383. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbw137

- Bandeen-Roche, K., Miglioretti, D. L., Zeger, S. L., & Rathouz, P. J. (1997). Latent variable regression for multiple discrete outcomes. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 92(440), 1375–1386. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1997.10473658

- Bowling, A. (2006). Lay perceptions of successful ageing: Findings from a national survey of middle aged and older adults in Britain. European Journal of Ageing, 3(3), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-006-0032-2

- Bowling, A., & Iliffe, S. (2011). Psychological approach to successful ageing predicts future quality of life in older adults. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9(1), 13–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-9-13

- Broadbent, D. E., Cooper, P. F., FitzGerald, P., & Parkes, K. R. (1982). The cognitive failures questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1982.tb01421.x

- Campbell-Sills, L., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Psychometric analysis and refinement of the connor–davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 1019–1028. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20271

- Cernin, P. A., Lysack, C., & Lichtenberg, P. A. (2011). A comparison of self-rated and objectively measured successful aging constructs in an urban sample of African American older adults. Clinical Gerontologist, 34(2), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2011.539525

- Cosco, T. D., Prina, A. M., Perales, J., Stephan, B. C., & Brayne, C. (2013). Lay perspectives of successful ageing: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMJ Open, 3(6), e002710. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002710

- Dawes, S. E., Palmer, B. W., Allison, M. A., Ganiats, T. G., & Jeste, D. V. (2011). Social desirability does not confound reports of wellbeing or of socio-demographic attributes by older women. Ageing and Society, 31(3), 438–454. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X10001029

- de Jager, C. A., Budge, M. M., & Clarke, R. (2003). Utility of TICS-M for the assessment of cognitive function in older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(4), 318–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.830

- Depp, C. A., & Jeste, D. V. (2006). Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(1), 6–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JGP.0000192501.03069.bc

- Eaton, N. R., Krueger, R. F., South, S. C., Gruenewald, T. L., Seeman, T. E., & Roberts, B. W. (2012). Genes, environments, personality, and successful aging: Toward a comprehensive developmental model in later life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 67(5), 480–488. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gls090

- Escota, G. V., O’Halloran, J. A., Powderly, W. G., & Presti, R. M. (2018). Understanding mechanisms to promote successful aging in persons living with HIV. International Journal of Infectious Diseases: IJID, 66, 56–64.

- Fast, E., Chen, B., & Bernstein, M. S. (2016). Empath: Understanding topic signals in large-scale text [Paper presentation]. In Proceedings of the 2016 Chi Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 4647–4657).

- Feng, Q., & Straughan, P. T. (2017). What does successful aging mean? Lay perception of successful aging among elderly Singaporeans. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(2), 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbw151

- Feng, Q., Son, J., & Zeng, Y. (2015). Prevalence and correlates of successful ageing: A comparative study between China and South Korea. European Journal of Ageing, 12(2), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-014-0329-5

- Fraser, K. C., Meltzer, J. A., & Rudzicz, F. (2016). Linguistic features identify Alzheimer’s disease in narrative speech. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD, 49(2), 407–422. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150520

- Freid, V. M., Bernstein, A. B., & Bush, M. A. (2012). Multiple chronic conditions among adults aged 45 and over; trends over the past 10 years. NCHS Data Brief, 100, 1–8.

- Golja, K., Daugherty, A. M., & Kavcic, V. (2020). Cognitive reserve and depression predict subjective reports of successful aging. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 90, 104137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2020.104137

- Honoré, A. (1979). Some simple measures of richness of vocabulary. Association for Literary and Linguistic Computing Bulletin, 7(2), 172–177.

- Iwamasa, G. Y., & Iwasaki, M. (2011). A new multidimensional model of successful aging: Perceptions of Japanese American older adults. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 26(3), 261–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-011-9147-9

- Jeste, D. V., & Lee, E. E. (2019). The Emerging empirical science of wisdom: Definition, measurement, neurobiology, longevity, and interventions. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 27(3), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000205

- Jeste, D. V., Ardelt, M., Blazer, D., Kraemer, H. C., Vaillant, G., & Meeks, T. W. (2010). Expert consensus on characteristics of wisdom: A Delphi method study. The Gerontologist, 50(5), 668–680. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnq022

- Jeste, D. V., Savla, G. N., Thompson, W. K., Vahia, I. V., Glorioso, D. K., Martin, A. S., Palmer, B. W., Rock, D., Golshan, S., Kraemer, H. C., & Depp, C. A. (2013). Association between older age and more successful aging: Critical role of resilience and depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(2), 188–196. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030386

- Jopp, D. S., Wozniak, D., Damarin, A. K., De Feo, M., Jung, S., & Jeswani, S. (2015). How could lay perspectives on successful aging complement scientific theory? findings from a US and a German life-span sample. The Gerontologist, 55(1), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu059

- Kavé, G., & Goral, M. (2016). Word retrieval in picture descriptions produced by individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 38(9), 958–966. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2016.1179266

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Laditka, S. B., Corwin, S. J., Laditka, J. N., Liu, R., Tseng, W., Wu, B., Beard, R. L., Sharkey, J. R., & Ivey, S. L. (2009). Attitudes about aging well among a diverse group of older Americans: Implications for promoting cognitive health. The Gerontologist, 49(S1), S30–S39. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnp084

- Lamond, A. J., Depp, C. A., Allison, M., Langer, R., Reichstadt, J., Moore, D. J., Golshan, S., Ganiats, T. G., & Jeste, D. V. (2008). Measurement and predictors of resilience among community-dwelling older women. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(2), 148–154.

- Lee, E. E. (2019). Aging successfully and healthfully. International Psychogeriatrics, 31(4), 439–441. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610219000012

- Lee, E. E., Bangen, K. J., Avanzino, J. A., Hou, B., Ramsey, M., Eglit, G., Liu, J., Tu, X. M., Paulus, M., & Jeste, D. V. (2020). Outcomes of randomized clinical trials of interventions to enhance social, emotional, and spiritual components of wisdom: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(9), 925–935. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0821

- Lee, E. E., Depp, C., Palmer, B. W., Glorioso, D., Daly, R., Liu, J., Tu, X. M., Kim, H., Tarr, P., Yamada, Y., & Jeste, D. V. (2019). High prevalence and adverse health effects of loneliness in community-dwelling adults across the lifespan: Role of wisdom as a protective factor. International Psychogeriatrics, 31(10), 1447–1462. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610218002120

- Leisch, F. (2004). FlexMix: A general framework for finite mixture models and latent glass regression in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 11(8), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v011.i08

- Marengoni, A., Angleman, S., Melis, R., Mangialasche, F., Karp, A., Garmen, A., Meinow, B., & Fratiglioni, L. (2011). Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Research Reviews, 10(4), 430–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003

- Martin, A. S., Palmer, B. W., Rock, D., Gelston, C. V., & Jeste, D. V. (2015). Associations of self-perceived successful aging in young-old versus old-old adults. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(4), 601–609. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104161021400221X

- Molton, I. R., & Yorkston, K. M. (2017). Growing older with a physical disability: A special application of the successful aging paradigm. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 72(2), 290–299.

- Montross, L. P., Depp, C., Daly, J., Reichstadt, J., Golshan, S., Moore, D., Sitzer, D., & Jeste, D. V. (2006). Correlates of self-rated successful aging among community-dwelling older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JGP.0000192489.43179.31

- Oswald, A. J., & Wu, S. (2010). Objective confirmation of subjective measures of human well-being: Evidence from the USA. Science, 327(5965), 576–579. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1180606

- Pruchno, R. A., Wilson-Genderson, M., & Cartwright, F. (2010). A two-factor model of successful aging. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65B(6), 671–679. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbq051

- Pruchno, R. A., Wilson-Genderson, M., Rose, M., & Cartwright, F. (2010). Successful aging: Early influences and contemporary characteristics. The Gerontologist, 50(6), 821–833. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnq041

- Pruchno, R., & Carr, D. (2017). Successful aging 2.0: Resilience and beyond. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 72(2), 201–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbw214

- Ramirez-Esparza, N., Chung, C. K., Kacewicz, E., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2008 The psychology of word use in depression forums in English and in Spanish: Texting two text analytic approaches [Paper presentation]. ICWSM.

- Rasmussen, S. E. V. P., Warsame, F., Eno, A. K., Ying, H., Covarrubias, K., Haugen, C. E., Chu, N. M., Crews, D. C., Harhay, M. N., Schoenborn, N. L., Segev, D. L., & McAdams-DeMarco, M. A. (2020). Perceptions, barriers, and experiences with successful aging before and after kidney transplantation: A focus group study. Transplantation, 104(3), 603–612.

- Reichstadt, J., Sengupta, G., Depp, C. A., Palinkas, L. A., & Jeste, D. V. (2010). Older adults’ perspectives on successful aging: Qualitative interviews. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(7), 567–575. https://doi.org/10.1097/jgp.0b013e3181e040bb

- Romo, R. D., Wallhagen, M. I., Yourman, L., Yeung, C. C., Eng, C., Micco, G., Pérez-Stable, E. J., & Smith, A. K. (2013). Perceptions of successful aging among diverse elders with late-life disability. The Gerontologist, 53(6), 939–949. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns160

- Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1987). Human aging: Usual and successful. Science (New York, N.Y.), 237(4811), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3299702

- Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 37(4), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.4.433

- Rude, S., Gortner, E. M., & Pennebaker, J. (2004). Language use of depressed and depression-vulnerable college students. Cognition & Emotion, 18(8), 1121–1133. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930441000030

- Scibelli, F. (2019). Detection of verbal and nonverbal speech features as markers of depression: Results of manual analysis and automatic classification. Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II.

- Tate, R. B., Lah, L., & Cuddy, T. E. (2003). Definition of successful aging by elderly Canadian males: The Manitoba follow-up study. The Gerontologist, 43(5), 735–744. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/43.5.735

- Thomas, M. L., Kaufmann, C. N., Palmer, B. W., Depp, C. A., Martin, A. S., Glorioso, D. K., Thompson, W. K., & Jeste, D. V. (2016). Paradoxical trend for improvement in mental health with aging: A community-based study of 1,546 adults aged 21–100 years. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(8), e1019–1025. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.16m10671

- van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). MICE: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(3), 1–68. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v045.i03

- Ware, J. E., Jr, & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002