Abstract

Objectives

Mental health problems are a major concern in the older population in Sweden, as is the growing number of older adults aging alone in their homes and in need of informal care. Using a linked lives perspective, this study explored if older parents’ mental health is related to their children’s dual burden of informal caregiving and job strain.

Methods

Data from a nationally representative Swedish survey, SWEOLD, were used. Mental health problems in older age (mean age 88) were measured with self-reported ‘mild’ or ‘severe’ anxiety and depressive symptoms. A primary caregiving adult child was linked to each older parent, and this child’s occupation was matched with a job exposure matrix to assess job strain. Logistic regression analyses were conducted with an analytic sample of 334.

Results

After adjusting for covariates, caregiving children’s lower job control and greater job strain were each associated with mental health problems in their older parents (OR 2.52, p = 0.008 and OR 2.56, p = 0.044, respectively). No association was found between caregiving children’s job demands and their older parents’ mental health (OR 1.08, p = 0.799).

Conclusion

In line with the linked lives perspective, results highlight that the work–life balance of informal caregiving adult children may play a role in their older parent’s mental health.

Introduction

The World Health Organization has stated mental health in older age to be one of the greatest public health challenges of our generation. Prior research in this area has found that older people’s well-being was negatively affected by negative life events that happened to their adult children, ages between 25 and 74 (Greenfield & Marks, Citation2006). Another study by Milkie et al. (Citation2008) found that older parents’ mental health (65+) was negatively impacted by their adult children’s experiences, such as unemployment and mental illness. Connections between older adults’ wellbeing and adult children’s life circumstances can be understood through life-course theory, particularly the concept of ‘linked lives’ which acknowledges that humans are connected throughout life (George, Citation2013). More specifically, the linked lives perspective suggests that the lives of individuals affect and are affected by others’ lives across the life course, with the family as a primary arena (Hutchison, Citation2010). As such, a stressor that befalls an adult child may have an impact on their older parent’s health (Greenfield & Marks, Citation2006; Kalmijn & De Graaf, Citation2012; Milkie et al., Citation2008). Although previous studies have found a link between older parent’s mental well-being in relation to their adult children’s life circumstances (Buber & Engelhardt, Citation2008; Mosca & Barrett, Citation2016), no previous study, to the best of our knowledge, has investigated the potential dual burden of job strain and providing informal care in relation to their older parent’s mental health, who is also the receiver of the informal care.

Recently in Sweden it has become increasingly common for adult children to provide a substantial amount of informal care to their parents, mostly as an unintended consequence of reductions in the formal care system in Sweden (Dahlberg et al., Citation2018; Ulmanen, Citation2017; Ulmanen & Szebehely, Citation2015). More specifically, with population aging there has been a steep increase in the number of older adults who require medical and social care in Sweden, and this unprecedented demand has pushed the Swedish system of formal care for the oldest old to its limits. In response, eligibility criteria for receiving such formal services have tightened, and increasing numbers of older adults are becoming dependent on informal help in their homes, often provided by family members (Khan, Citation2014; Ulmanen & Szebehely, Citation2015). These family caregivers are usually a partner or spouse of the older person. However, adult children also play an essential role in providing help and care to their older parents. Many adults provide informal care to their older parents in combination with paid work.

A major stressor in adult life is stress derived from the work environment (Nieuwenhuijsen et al., Citation2010). When a job requirement exceeds the worker’s capability and resources, job strain occurs and can lead to reduced job satisfaction and harmful physical and emotional responses in the individual (Kivimäki et al., Citation2006; Stansfeld & Candy, Citation2006). However, many caregivers report positive caregiving experiences, such as emotional satisfaction in caring for their older family members due to different factors like the caregiver’s cultural values (Boerner et al., Citation2004; Tang, Citation2011; Wong et al., Citation2019; Yamamoto-Mitani et al., Citation2003). Still, several researchers have identified that informal caregivers of older adults face a high level of burden, such as financial difficulties, work-related strain, and lower quality of life (Sacco et al., Citation2022; Thai et al., Citation2016Citation; Trukeschitz et al., Citation2013Citation;). This burden has been associated with a high risk of cognitive mental health problems among informal caregivers (Hiel et al., Citation2015; Lindt et al., Citation2020; Pendergrass et al., Citation2019; Romero-Martinez et al., Citation2020).

Together, these multiple responsibilities can result in a dual burden from informal care demands and the caregiver’s job strain from their paid job (Wang et al. Citation2018). The focus of earlier research investigating the negative impact of being an informal caregiver in combination with a paid job has been from the worker’s perspective (see e.g. Mortensen et al., Citation2017; Wang et al., Citation2018), not the aging parent. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore if such a dual burden is associated with the older parent’s mental health.

We hypothesize that the life circumstances of older adults (76 years and older) and their adult caregiving children are linked, and that older adults who mainly receive informal care from an adult child with a stressful job, are more likely to have mental health problems.

Materials and methods

Data collection and analytic sample

Data were collected from the Swedish Panel Study of Living Conditions of the oldest old (SWEOLD) database (Lennartsson et al., Citation2014). SWEOLD is an ongoing, nationally representative survey that studies the health and living conditions of the oldest old, age 76 and above. SWEOLD is primarily based on face-to-face interviews with a structured questionnaire at the participant’s home or in care institutions. This study uses data from SWEOLD 2011. The project and data collection were ethically reviewed and approved by The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (DNR 2010/403-31/4).

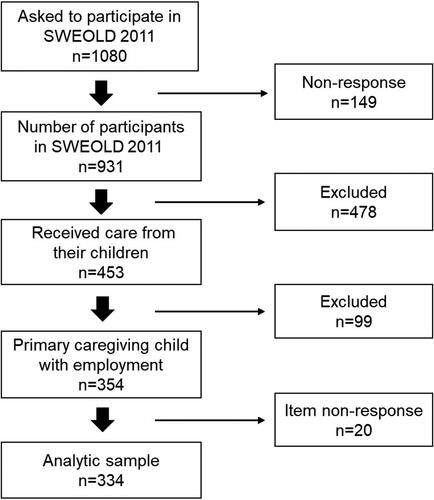

A total of 1080 older persons were invited to SWEOLD 2011. A total of 931 people participated resulting in a response rate of 86.2 percent. A total of 802 (83.6%) received or needed any help with practical or personal care. Among those, 453 (56.5%) received help from their children, among which 354 participants had a caregiving child that also had employment. Item nonresponse reduced the analytical sample further to 334 participants (see ), among which 217 were women, and 117 were men, with ages ranging between 77 and 101 years (mean = 88, SD = 6.66). In the analytic sample, 214 participants (64.1%) participated through direct interviews, 88 (26.4%) via indirect interviews, and 32 (9.6%) via mixed interviews. In this survey the proxy was a spouse, close relative, friend, or health care professional (home care, institution). Participants who could not participate in a face-to-face interview were offered a telephone interview or as a last resort, a postal questionnaire. None of the participants in our analytic sample participated via questionnaire.

Primary caregiving child

The primary informal caregiving children were identified via four steps. First, to identify the child providing the highest level of help to their parent, the amount of help received from each adult child was calculated as a percentage of the cumulative number of activities for which a respondent reported receiving help. The self-reported questions on the type of help received included six items/areas: 1) buying food, 2) preparing food, 3) housecleaning, 4) bathing or showering, 5) household or personal care tasks, and 6) miscellaneous (i.e. repairs or maintenance, gardening, clearing away snow or the like, private economy – paying the bills, taking care of insurances etc., buying clothes or other personal things, getting rides – e.g. to the doctor/pharmacy/hairdresser/post office or bank). Second, if two or more of the siblings were tied as highest percentage helpers, the sibling with the highest frequency of time spent with the parent was chosen, based on the answers to the question: ‘How often do you meet and spend time with any of your children?’ Answers were 1 = daily, 2 = several times a week, 3 = a few times a week, 4 = a few times a month, 5 = a few times a quarter, 6 = seldom or never. This was the case for 48 participants. Third, if two or more siblings were tied as the highest percentage helper and the highest frequency of time spent with their parent, the first-mentioned adult child was chosen. This was the case for 51 participants. Fourth, among the 453 participants with a primary child chosen, a total of 110 of them had a chosen primary child with missing data on employment. To maximise statistical power, we decided to choose the adult child with the second most time spent with their parent or the second mentioned child if the child had valid employment. This was true for 11 cases. This selection procedure of primary caregiving adult children with employment reduced the study sample to 354 (see ). The majority of primary caregiving children were daughters (56.7%) and the average age was 59 years old (range: 28–78).

Variables

Mental health indicators in older age

Mental health was assessed with two indicators: ‘Have you in the last 12 months suffered from depression or deep sadness?’ (No; Yes, mild; Yes, severe) and ‘Have you in the last 12 months experienced nervousness or anxiety?’ (No; Yes, mild; Yes, severe). Answers were then dichotomised into having any mental health problem (moderate or severe) or having none.

Job strain among primary caregiving children

Job strain was assessed by matching the adult children’s occupation with a job–exposure matrix (JEM). The JEM consists of tables showing the average working conditions for different occupations, following the job demand–control model by Karasek (Citation1979). The JEM scores were based on job strain for 262 occupations from the 1977 and 1979 Swedish Survey of Living Conditions (ULF) with a random sample of 12,084 Swedish workers between the ages of 16 and 74 (Johnson & Stewart, Citation1993). In the ULF, separate scores for work control (twelve questions) and job demand (two questions) were generated for women and men. In practice, this means that a woman and a man holding the same occupation were assigned different JEM scores. The ULF score for work control utilised the response alternatives never, sometimes or often to assess the following twelve items: 1) planning of work, 2) planning of vacations, 3) planning of work breaks, 4) the selection of supervisors, 5) the selection of co-workers, 6) the setting of the work pace, 7) how time is used in work, 8) if there are varied work procedures, 9) if there are varied task content, 10) flexible working hours, 11) the possibility to learn new things, and 12) the experience of personal fulfilment on the job. The psychological job demand dimension was assessed with two questions: ‘Is your job hectic?’ and ‘Is your job psychologically demanding?’ All variables in the matrix consisted of a linear composite that ranged between 0 and 10 (Johnson et al., Citation1990). In our analytic sample, job control scores ranged from approximately 1.3 to 7.4 with an average of 4.7 (median = 4.8) and job demands ranged from 1.3 to 9.3 with an average of 5.1 (median 5.0). Job control and demand were dichotomised using a median split based on the median in the ULF sample. High job strain was assessed by combining high demands with low control (Pan et al. Citation2019).

Covariates

The covariates were the older parent’s sex, age, marital/partnership status, level of education, social support, self-rated health (SRH), Activity of Daily Living (ADL), and Instrumental Activity of Daily Living (IADL). Marital/partnership status was assessed by asking ‘What is your present marital status?’ with options not married, married/cohabiting, divorced/separated, and widow/widower. Level of education was measured through Swedish national registries for the 1968 Level of Living Survey (LNU) that is linked with the SWEOLD survey, and data from their first interview in a SWEOLD study, and categorized as compulsory level of education and above compulsory education. Social support was assessed through the question ‘Do you have a relative or close friend who can help you if you need someone to talk to about your personal problems?’ with options no and yes (sometimes or often). Self-reported health (SRH) was measured with responses to the question ‘How would you assess your own general state of health?’ and presented as good, poor, or neither good or poor. Furthermore, ADL and IADL were measured through the everyday tasks the participants managed. ADL tasks included eating, toilet visit, dressing and undressing, getting into and out of bed and hair washing. The answers were combined and the variable dichotomized as ‘Not able to perform one or more of the tasks’ and ‘Able to perform all tasks’. IADL tasks included buying food, preparing food/cooking and cleaning the house. The answers were combined and the variable dichotomized as ‘Not able to perform one or more of the tasks’ or living in an institution, and ‘Able to perform all tasks’. Details about the older parent’s relationship to their primary caregiving child were adjusted for in order to isolate the independent associations between the primary caregiver’s working conditions and their older parent’s mental health. These parent–child relationship factors were assessed through the geographical distance to the primary caregiving child (response options: living in the same household, less than 2 km, between 3 and 20 km, between 30 and 100 km, between 110 and 300km, further away than 300 km), perceived conflict with the primary caregiving child (response options: fairly much or much, some, not at all) and amount of help from the primary caregiving child (help with one, two three, four or five tasks). Adjustments were also made in the statistical analyses regarding the primary caregiving child’s age, sex, and occupational social class. The primary caregiving child’s occupational social class was categorised according to the Social Economic Index [SEI]. The categories were unskilled worker, skilled worker and lower white-collar, middle white-collar, upper white-collar (and professionals), self-employed, and farmer.

Statistical approach

All statistical analyses were conducted in STATA 15. Because men aged 85-99 and women aged 90–99 were oversampled in the SWEOLD 2011 study, sampling weights were used for all analyses, including frequencies in the analytic sample. Logistic regression was used to analyse the association between the primary caregiving child’s job strain and their older parent’s mental health, while adjusting for covariates.

Results

Participant characteristics

shows that a greater proportion of older adults who reported mental health problems were women (76.6%). The results in also indicate an association between marital/partnership status groups (p = 0.017) and mental health in older age, with a greater proportion of older adults who reported mental health problems among widows/widowers (63.8%). A greater proportion of older adults who reported mental health problems also reported poor self-rated health (18.5%) compared to those that did not report mental health problems (9.1%). However, there are no statistically significant associations between mental health problems in older age and the ability to perform activities of daily living (p = 0.055), instrumental activities of daily living (p = 0.409), age (p = 0.709), levels of education (p = 0.132), or social support (p = 0.242).

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of older parents, by occurrence of mental health problems.

Job strain in primary caregivers and their older parent’s mental health

indicates that older parents who have a primary caregiving child with low job control have about 2.5 higher odds (OR 2.52, p = 0.008) of experiencing mental health problems when compared with those whose primary caregiving child has high job control, adjusting for covariates. Older parents with a primary caregiving child with high job strain (low control combined with high demand) have about 2.6 greater odds (OR 2.56, p = 0.044) of reporting mental health problems, compared to those with low strain (i.e. low demand and high control), passive jobs (i.e. low demand and low control) or active jobs (high demand and high control). Mental health problems did not differ between older parents who have a primary caregiving child with high job demand compared with those whose primary caregiving child has low job demand (OR 1.08, p = 0.799).

Table 2. Associations between older parent’s mental health and the primary caregiving child’s job strain.

Discussion

This study contributes to the understanding of how older adults’ mental health may be related to their primary caregiving children’s life circumstances, in this case, job strain. Guided by the linked lives perspective (Hutchinson, 2010), the association between older parents’ mental health and adult children’s dual burden of informal caregiving and having a stressful job, was explored. In sum, greater work stress of the primary caregiving adult child, in particular having low job control, was related to mental health problems in the older parent.

As suggested by the results in this study, adult children’s inability to influence what happens in their work environment (low job control) and high levels of job strain not only influence the adult child’s own mental health as has been previously found (Almroth et al., Citation2021; Theorell et al., Citation2015), but are also linked with their older parent’s mental health. In a similar vein, social–psychological stressors among adult children, such as negative life events (e.g. serious accident or injury, a physical or mental illness, serious money problems, divorce or separation, or unemployment), have been found to be associated with parents’ mental health problems (Greenfield & Marks, Citation2006; Milkie et al., Citation2008). Older parents tend to provide both emotional and practical support to adult children with problems but also receive support from their troubled children at the same time (Huo et al., Citation2019). Understanding the perceived burdens experienced by family members could reveal important dynamics of intergenerational relationships leading to possible vulnerabilities in individual mental health (Ennis & Bunting, Citation2013). Adult children often experience competing pressures of employment, taking care of their own children, and providing care for older parents (Evans et al., Citation2016). If the primary caregiving adult child is stressed due to work, while also facing substantial demands with regard to informal caregiving, an older parent’s mental health may be compromised. However, due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, directionality cannot be teased out – an alternative interpretation is that (long term) mental health problems in the older parent may entail an increased risk of (long term) mental health problems in the adult child, which in turn may be related to the type of occupations (e.g. low control jobs) she/he holds.

Nevertheless, a possible interpretation of the results is that the mental health of the primary caregiving adult child is a mediator between their situation at work and their older parent’s mental health. The relationship between adult children’s informal caregiving burden and their own mental health problems has been previously reported (Brandao et al., Citation2017; Hiel et al., Citation2015; Lin et al., Citation2013; Marquez et al., Citation2012). It is also likely that the quality of care provided by an adult child with a stressful job may be negatively affected due to less time to provide good care as a consequence of having a demanding job. Also, having a job with high control means that one can probably dictate when and where to work, allowing for more flexibility in caring for a parent. Those with low job control have little flexibility and may therefore be less able to meet the parent’s immediate needs on a regular basis. For example, with low job control, one may not even be able to take a phone call from a parent during work hours.

Although high job demands are considered stressful (Karasek, Citation1979), no statistically significant association was found with the older parents’ mental health. Previous studies have found inconclusive results from high job demands as a stressor (Nexø et al., Citation2016; Then et al. Citation2014). Perhaps the double-nature of psychological demands (i.e. demands not only representing stress but also bringing intellectual stimulation) could explain the null results in this study. It has also been shown that a job–exposure matrix does not identify occupations with high demands as accurately as it does with low control or job strain (Solovieva et al., Citation2014).

Limitations and strengths

A strength of the study is that SWEOLD is based on a representative sample of the older population in Sweden with high response rates (Lennartsson et al., Citation2014). Another strength is the inclusion of an extra sample of men aged 85–99 and women aged 90–99 to ensure the representativity of the sample. That said, the study population is only representative based on age and gender, hence it is not large enough to analyze different population subgroups, such as immigrant groups, to investigate possible cultural differences in regard of informal caregiving. Proxy interviews were conducted in order to include the frail and cognitively impaired respondents, also increasing the generalisability of the study results to the general older population (Kelfve et al., Citation2013). At the same time, one may argue that the proxy interviews should not be included, as proxies – who may include the primary caregiving child – may not accurately represent the perspectives of the study participant (McPhail, Citation2008). To minimize such information bias, a sensitivity analysis was conducted where the proxy interviews (n = 88) were excluded from the analytic sample. The results showed a slight difference in the significance level; however, the point estimates were still similar and in the same direction.

Another limitation of this study was the use of cross-sectional data, which limits the possibility to disentangle cause and effect. Using occupational data linked with a job exposure matrix should limit the risk for reverse causation as job demands and control are ‘objectively’ assessed. On the other hand, reverse causation could be present if the older parent’s mental health influences the older worker to change workplace or start working part time – but stay in the same occupation. Similarly, although adjusting the analyses for a variety of covariates, it is still possible that some residual confounding remains that may influence the associations.

Furthermore, the job demand–control model is not designed to account for all the variation in stressors related to work (Solovieva et al., Citation2014) and may not be accurate in identifying psychological work stress due to the possible changes that might have occurred over time, such as changes in work environment and tasks involved in different occupations (Mark & Smith, Citation2008). As our measure is crude, there is most likely individual variation in perceived stress that is unaccounted for. If these unaccounted differences in stress are also associated with the older parent’s mental health, our models are likely to underestimate the associations. However, the JEM captures the average level of stressors from multiple work organizations based on self-reports from over 12,000 participants (Johnson & Stewart, Citation1993), which reduces the risk for misclassification bias.

An additional limitation of this study is that the SWEOLD survey was not designed to examine mental health, which limits the range of indicators and the level of detail that could be included in the analyses. Also, the time frame for capturing mental health problems (during the last 12 months) is long. This, together with the low cutoff for mental health problems (‘moderate or severe’) may explain the relatively high proportion of mental health problems observed in this study.

Also, while the SWEOLD study provides the unique possibility to investigate the older parent – adult child link, the focus of the survey is on the older parent thus providing no measure on the primary caregiving child’s health. There is a need for future research using longitudinal data and more detailed information about the primary caregiver’s mental health to further elaborate this association.

Conclusion

To conclude, we found an association between older parents’ mental health problems and the dual burden of caregiving and job strain in their primary caregiving adult child, in line with the linked lives perspective. The results highlight the potential importance of the informal caregiving children’s work–life balance in relation to their older parent’s mental health.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants in the SWEOLD study for their time and contributions to the study. The authors would like to thank the researchers who were involved in data acquisition for the SWEOLD study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

Public access to the database may be given if applicants have a scientific affiliation, sign a statement that the data will only be used for scientific purposes, and that the scientific project has ethical approval. Applicable sections of The Swedish Research Council (VR) principles for conducting research in humanities and the social sciences must be adhered to (http://www.codex.vr.se/en/forskninghumsam.shtml). Data will be available after the above-mentioned documents have been received, by email at the SWEOLD Research Data Center [email protected] More information can be found at www.sweold.se.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Almroth, M., Hemmingsson, T., Sörberg Wallin, A., Kjellberg, K., Burström, B., & Falkstedt, D. (2021). Psychosocial working conditions and the risk of diagnosed depression: A Swedish register-based study. Psychological Medicine, 19, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172100060X

- Boerner, K., Schulz, R., & Horowitz, A. (2004). Positive aspects of caregiving and adaptation to bereavement. Psychology & Aging, 19(4), 668–675. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.19.4.668

- Brandao, D., Ribeiro, O., Oliveira, M., & Paul, C. (2017). Caring for a centenarian parent: An exploratory study on role strains and psychological distress. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 31(4), 984–994. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12423

- Buber, I., & Engelhardt, H. (2008). Children’s impact on the mental health of their older mothers and fathers: Findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. European Journal of Ageing, 5(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-008-0074-8

- Dahlberg, L., Berndt, H., Lennartsson, C., & Schön, P. (2018). Receipt of formal and informal help with specific care tasks among older people living in their own home. National trends over two decades. Social Policy & Administration, 52(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12295

- Ennis, E., & Bunting, B. P. (2013). Family burden, family health and personal mental health. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 255–259. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-255

- Evans, K. L., Millsteed, J., Richmond, J. E., Falkmer, M., Falkmer, T., & Girdler, S. J. (2016). Working sandwich generation women utilize strategies within and between roles to achieve role balance. PloS One, 11(6), e0157469. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157469

- George, L. K. (2013). Age structures, aging and the life course. In J. M. Wilmoth & K.F. Ferraro (Eds.), Gerontology: Perspectives and issues (4th ed.) (pp. 149–172). Springer.

- Greenfield, E. A., & Marks, N. F. (2006). Linked lives: Adult children’s problems and their parents’ psychological and relational well‐being. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 68(2), 442–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00263.x

- Hiel, L., Beenackers, M. A., Renders, C. M., Robroek, S. J., Burdorf, A., & Croezen, S. (2015). Providing personal informal care to older European adults: Should we care about the caregivers’ health? Preventive Medicine, 70, 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.10.028

- Huo, M., Graham, J. L., Kim, K., Birditt, K. S., & Fingerman, K. L. (2019). Aging parents’ daily support exchanges with adult children suffering problems. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 74(3), 449–459. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx079

- Hutchison, E. D. (2010). A life course perspective. Dimensions of Human Behavior: The Changing Life Course, 4, 1–38.

- Johnson, J. V., & Stewart, W. F. (1993). Measuring work organization exposure over the life course with a job-exposure matrix. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 19(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.1508

- Johnson, J. V., Stewart, W., Fredlund, P., Hall, E. M., & Theorell, T. (1990). Psychosocial job exposure matrix: An occupationally aggregated attribution system for work environment exposure characteristics. Stress Research Reports No. 221. Karolinska Institutet.

- Kalmijn, M., & De Graaf, P. M. (2012). Life course changes of children and well‐being of parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(2), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00961.x

- Karasek, R. A.Jr, (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(2), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392498

- Kelfve, S., Thorslund, M., & Lennartsson, C. (2013). Sampling and non-response bias on health-outcomes in surveys of the oldest old. European Journal of Ageing, 10(3), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-013-0275-7

- Khan, H. T. (2014). Factors associated with intergenerational social support among older adults across the world. Ageing International, 39(4), 289–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-013-9191-6

- Kivimäki, M., Virtanen, M., Elovainio, M., Kouvonen, A., Väänänen, A., & Vahtera, J. (2006). Work stress in the etiology of coronary heart disease—A meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 32(6), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.1049

- Lennartsson, C., Agahi, N., Hols-Salén, L., Kelfve, S., Kåreholt, I., Lundberg, O., Parker, M. G., & Thorslund, M. (2014). Data resource profile: The Swedish panel study of living conditions of the oldest old (SWEOLD). International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(3), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu057

- Lin, W. F., Chen, L. H., & Li, T. S. (2013). Adult children’s caregiver burden and depression: The moderating roles of parent–child relationship satisfaction and feedback from others. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(2), 673–687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9348-0

- Lindt, N., van Berkel, J., & Mulder, B. C. (2020). Determinants of overburdening among informal carers: A systematic review. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01708-3

- Mark, G. M., & Smith, A. P. (2008). Stress models: A review and suggested new direction. Occupational Health Psychology, 3, 111–144.

- Marquez, D. X., Bustamante, E. E., Kozey-Keadle, S., Kraemer, J., & Carrion, I. (2012). Physical activity and psychosocial and mental health of older caregivers and non-caregivers. Geriatric Nursing (New York, NY), 33(5), 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2012.03.003

- McPhail, S., Beller, E., & Haines, T. (2008). Two perspectives of proxy reporting of health-related quality of life using the Euroqol-5D, an investigation of agreement. Medical Care, 46(11), 1140–1148. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817d69a6

- Milkie, M. A., Bierman, A., & Schieman, S. (2008). How adult children influence older parents’ mental health: Integrating stress-process and life-course perspectives. Social Psychology Quarterly, 71(1), 86–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250807100109

- Mortensen, J., Dich, N., Lange, T., Alexanderson, K., Goldberg, M., Head, J., Kivimäki, M., Madsen, I. E., Rugulies, R., Vahtera, J., Zins, M., & Rod, N. H. (2017). Job strain and informal caregiving as predictors of long-term sickness absence: A longitudinal multi-cohort study. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 43(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3587InsertedFromOnline]

- Mosca, I., & Barrett, A. (2016). The impact of adult child emigration on the mental health of older parents. Journal of Population Economics, 29(3), 687–719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-015-0582-8

- Nexø, M. A., Meng, A., & Borg, V. (2016). Can psychosocial work conditions protect against age-related cognitive decline? Results from a systematic review. Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 73(7), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2016-103550

- Nieuwenhuijsen, K., Bruinvels, D., & Frings-Dresen, M. (2010). Psychosocial work environment and stress-related disorders: A systematic review. Occupational Medicine (Oxford, England), 60(4), 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqq081

- Pan, K. Y., Xu, W., Mangialasche, F., Dekhtyar, S., Fratiglioni, L., & Wang, H. X. (2019). Working life psychosocial conditions in relation to late-life cognitive decline: A population-based cohort study. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD, 67(1), 315–325. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-180870

- Pendergrass, A., Mittelman, M., Graessel, E., Özbe, D., & Karg, N. (2019). Predictors of the personal benefits and positive aspects of informal caregiving. Aging & Mental Health, 23(11), 1533–1538. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1501662

- Romero-Martínez, Á., Hidalgo-Moreno, G., & Moya-Albiol, L. (2020). Neuropsychological consequences of chronic stress: The case of informal caregivers. Aging & Mental Health, 24(2), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1537360

- Sacco, L. B., König, S., Westerlund, H., & Platts, L. G. (2022). Informal caregiving and quality of life among older adults: Prospective analyses from the Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health (SLOSH). Social Indicators Research, 160(2–3), 845–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02473-x

- Solovieva, S., Pensola, T., Kausto, J., Shiri, R., Heliövaara, M., Burdorf, A., Husgafvel-Pursiainen, K., & Viikari-Juntura, E. (2014). Evaluation of the validity of job exposure matrix for psychosocial factors at work. PloS One, 9(9), e108987. 10.1371/journal.pone.0108987

- Stansfeld, S., & Candy, B. (2006). Psychosocial work environment and mental health: A meta-analytic review. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 32(6), 443–462. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.1050

- Tang, M. (2011). Can cultural values help explain the positive aspects of caregiving among Chinese American caregivers? Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 54(6), 551–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2011.567323

- Thai, J. N., Barnhart, C. E., Cagle, J., & Smith, A. K. (2016). “It just consumes your life” Quality of life for informal caregivers of diverse older adults with late-life disability. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 33(7), 644–650. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909115583044

- Then, F. S., Luck, T., Luppa, M., Thinschmidt, M., Deckert, S., Nieuwenhuijsen, K., Seidler, A., & Riedel-Heller, S. G. (2014). Systematic review of the effect of the psychosocial working environment on cognition and dementia. Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 71(5), 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2013-101760

- Theorell, T., Hammarström, A., Aronsson, G., Träskman Bendz, L., Grape, T., Hogstedt, C., Marteinsdottir, I., Skoog, I., & Hall, C. (2015). A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1954-4

- Trukeschitz, B., Schneider, U., Mühlmann, R., & Ponocny, I. (2013). Informal eldercare and work-related strain. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 68(2), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbs101

- Ulmanen, P. (2017). Childcare and eldercare policies in Sweden. In R. J. Burke & L. M. Calvano (Eds.), The Sandwich generation: Caring for oneself and others at home and at work (pp. 242–261). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781785364969.00020

- Ulmanen, P., & Szebehely, M. (2015). From the state to the family or to the market? Consequences of reduced residential eldercare in Sweden. International Journal of Social Welfare, 24(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12108

- Wang, Y.-N., Hsu, W.-C., Yang, P.-S., Yao, G., Chiu, Y.-C., Chen, S.-T., Huang, T.-H., & Shyu, Y.-I L. (2018). Caregiving demands, job demands, and health outcomes for employed family caregivers of older adults with dementia: Structural equation modeling. Geriatric Nursing (New York, NY), 39(6), 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2018.05.003

- Wong, D. F. K., Ng, T. K., & Zhuang, X. Y. (2019). Caregiving burden and psychological distress in Chinese spousal caregivers: Gender difference in the moderating role of positive aspects of caregiving. Aging & Mental Health, 23(8), 976–983.

- Yamamoto-Mitani, N., Ishigaki, K., Kawahara, Maekawa, N., Kuniyoshi, M., Hayashi, K., Hasegawa, K., & Sugishita, C. (2003). Factors of positive appraisal of care among Japanese family caregivers of older adults. Research in Nursing & Health, 26(5), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.10098