Abstract

Objective

Western countries face ageing populations and increasing numbers of older adults receiving long-term care at home (home care). Approximately 50% of households in Western countries own pets, and while pets impact the health and wellbeing of their owners, most healthcare organisations do not account for the role of pets in the lives of their clients. Due to the lack of research in older adults receiving home care that own pets, this study aimed to review previous qualitative research about the role and significance of pets for older adults in general.

Method

PubMed and PsycINFO were systematically searched with variations on (MeSH) terms for older adults (mean age 65 years and older), pets, and qualitative study designs. Iterative-inductive thematic analyses were performed in ATLAS.ti.

Results

We included fifteen studies and extracted twenty-eight themes within seven categories: Relational Aspects, Reflection and Meaning, Emotional Aspects, Aspects of Caregiving, Physical Health, Social Aspects, and Bidirectional Behaviour. Older adults reported not only on positive aspects of pet ownership such as the emotional support their pets provided but also on negative aspects such as postponing personal medical treatment.

Conclusion

Older adults perceived pets as important for their health and wellbeing. This implies that care workers may be able to improve home care by accounting for the role of pets of older adults receiving home care. Based on our findings, we suggest that community healthcare organisations develop guidelines and tools for care workers to improve care at home for clients with pets.

Introduction

Western countries face ageing populations and concomitant increases in the number of older adults with chronic illness (Abbing, Citation2016; Lipszyc et al., Citation2012). Currently, many older adults receiving long-term care (LTC) reside in their own homes (further addressed as older adults receiving home care) (Abbing, Citation2016; Lipszyc et al., Citation2012; Spasova et al., Citation2018). Over 50% of Western households own at least one pet (Bedford, Citation2021; FEDIAF, Citation2019). However, estimates of the prevalence of pet ownership in older age vary (Applebaum et al., Citation2020; Friedmann et al., Citation2020; Himsworth & Rock, Citation2013). Himsworth and Rock (Citation2013) found that 27% of Canadians aged 65 years and older owned a pet, while Applebaum et al. (Citation2020) found that in the United States, 50% of adults over the age of 70 owned a pet. There is some evidence that after the age of 70, the prevalence of pet ownership may decrease by up to 50% with each additional decade of life (Friedmann et al., Citation2020; Himsworth & Rock, Citation2013). Still, this suggests that many older adults receiving home care own pets. The term pet ownership, however, may be misleading since many pet owners consider their pets as friends or family members (Amiot et al., Citation2016).

The scientific literature indicates that pets provide physical, emotional, and social benefits for older adults. For instance, pets are associated with reduced depression, loneliness, and anxiety, and with improved quality of life, physical activity, and social connections (Gee et al., Citation2017; HAS, Citation2015; Hughes et al., Citation2020). However, the results of studies on the effects of pet ownership do not provide consistent outcomes (e.g. Mueller et al., Citation2018; Rodriguez et al., Citation2020; Winefield et al., Citation2008), and pet ownership can also have negative effects, such as increased risk of falls, allergies, transmission of diseases, psychological dependency, and excessive grief responses after pet bereavement (Beck & Katcher, Citation2003; Dowsett et al., Citation2020; Toray, Citation2004). Some qualitative studies overlooked the importance of pets in the lives of people receiving home care (Ryan & Ziebland, Citation2015). Taken together, research shows that pets are an important factor that needs to be considered in home care.

By accounting for the role of pets in their clients’ lives, care workers may be able to improve the care process and care outcomes (Rauktis & Hoy-Gerlach, Citation2020; Risley-Curtiss, Citation2010; Toohey et al., Citation2017). However, community healthcare organisations rarely have guidelines that account for their clients’ pets. To account for clients’ pets, care workers and healthcare organisations require comprehensive information on the effects and the role of pets in clients’ lives (Rauktis & Hoy-Gerlach, Citation2020; Risley-Curtiss, Citation2010; Toohey et al., Citation2017).

To date, several qualitative studies have been conducted on the role of pets in the lives of older adults (e.g. Cole, Citation2019; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000). These studies provide rich data and help researchers better understand the significance of pets for older adults. The outcomes of these studies, however, have not been reviewed so far. The aim of this qualitative systematic review was to identify important themes that reflect the significance and role of pets, from the perspective of both older adults who receive home care and those who do not. By doing so, we hope to contribute to the improvement of home care and provide a basis for the future development of guidelines and tools for community healthcare organisations.

Methods

Design and search strategy

To establish common themes on experiences of older adults living at home with their pets, we conducted a qualitative systematic review (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). The research group consisted of a PhD student (PR), a research assistant (ID), and experts in human-animal studies (KH and ME) and geriatric care research (DG and RL). Qualified supervisors guided the research process and reflexivity during workgroup discussions.

To develop our systematic search strategy we used the PICOS-model (EUnetHTA, Citation2019; Frandsen et al., Citation2020) with the elements Population (older adults, mean age 65 years and older), Intervention (pets), and Study Design (qualitative design) to systematically search for relevant studies (EUnetHTA, Citation2019; Frandsen et al., Citation2020). See the Appendix, for the applied search strategies. On 19 February 2021, we searched PubMed and PsycINFO, using MeSH term variations. Finally, to find additional eligible literature, we screened reference lists of systematic reviews and searched HABRI central, an index specialised in human-animal interaction literature.

Inclusion criteria and selection

Due to the language proficiency of the researchers, we limited the review to studies published in English and Dutch. There was no limitation on date of publication. Because an initial search showed a lack of qualitative studies on older adults receiving home care, we extended our focus and included studies with older adults from the general population. Since 85% of older adults (65 years and older) have at least one chronic illness (RIVM, Citation2021), there are many shared experiences between older adults who receive home care and those who do not. We excluded studies with a focus on animal-assisted interventions and studies with institutionalised older adults.

To identify eligible articles, the records obtained by the database searches were transferred to the Web app Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016). In Rayyan, two researchers (PR and ID) independently screened titles and abstracts. Subsequently, the two researchers independently screened full-text articles. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

The Mixed-Methods Assessment Tool (MMAT) was used to assess the quality of the included studies (Hong et al., Citation2019). Two researchers discussed independently conducted evaluations to reach consensus on the quality of the included studies, see the Appendix, .

Analyses

We performed a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Nowell et al., Citation2017) in ATLAS.ti version 8 for Windows (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH) using an iterative-inductive approach. During the course of the analysis several work group discussions were arranged. A researcher (PR) inductively constructed an initial set of codes based on the first three studies from the list in ATLAS.ti to guide the process and approach of analysis. Subsequently, two researchers (PR and ID) independently coded all included studies using the predefined codes and by adding new codes. A set of themes was created based on the codes, inductive reasoning, and a workgroup discussion (PR, ID, RL, KH, and ME). To confirm the themes deductively the two researchers (PR and ID) independently analysed the studies once more in ATLAS.ti. Similarities and differences in interpretation were assessed using the ATLAS.ti intercoder agreement function, followed by a discussion between PR and ID. After reaching consensus, the expert members of the workgroup KH, ME, DG, and RL independently categorised the themes using an inductive approach. All authors discussed the categories and themes until consensus was reached. In addition to the thematic analysis, PR and ID extracted study characteristics such as study design, type of pet, and gender and age of participants.

Results

Search results

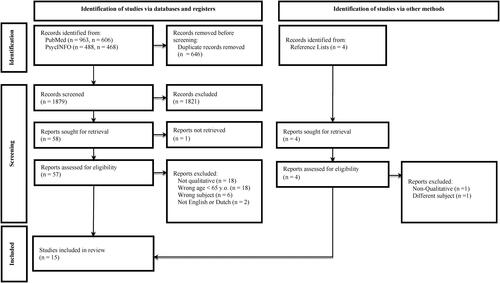

Initially, we identified 2525 studies. After removing 646 duplicates in Rayyan, two researchers (PR and ID) screened 1879 studies by reading titles and abstracts. Reasons to omit studies were, for instance, a different population or method (e.g. quantitative), or the use of laboratory animals. This resulted in 62 potentially eligible studies, which were assessed on their full-text content (see flowchart, ). In one case, a full-text could not be obtained through the Open University’ library, and the study was therefore omitted. A final sample of fifteen studies was included in this review ().

Table 1. Included studies.

Study characteristics

presents an overview of the 15 included studies including a total of 340 participants (N = 115 male, N = 225 female). Three studies involved older adults who were explicitly in need of care: people with chronic pain (Janevic et al., Citation2020), stroke survivors (Johansson et al., Citation2014), and older adults with physical impairments (Williams, Citation2018).

Most participants were dog owners, followed by cat owners, and then birds owners (). Three studies did not describe the type of pet owned (Bunkers, Citation2010; Muraco et al., Citation2018; Putney, Citation2014). The studies took place between 2000 and 2021 in the United States (n = 6), Australia (n = 3), China (n = 1), the United Kingdom (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), the Netherlands (n = 1), Austria (n = 1), and Canada (n = 1). Our searches also yielded grey literature, which we included: a dissertation (Williams, Citation2018), a book chapter (Enders-Slegers, Citation2000), and an interview published in a scientific journal (Parks et al., Citation2011).

Categories and themes

The analysis resulted in 28 themes, which we grouped into seven categories () that describe various aspects of older adults’ experiences with their pets. Overall, the older adults in the included studies indicated that they had a strong bond with their pets, and that they believed their pets had a positive influence on their social, mental, and physical wellbeing. However, some participants also discussed negative aspects of pet ownership.

Table 2. Categories and themes.

Relational aspects

Three themes describing the relationship between older adults and their pets—attachment, unconditional love, and interdependence—were grouped in the category relational aspects. Attachment describes the feeling expressed by many participants that they were bonded to their pets and that they perceived their pets to be attached to them. Pets were often referred to as friends, family members, or children (Bunkers, Citation2010; Chen et al., Citation2020; Chur-Hansen et al., Citation2009; Cole, Citation2019; Cryer et al., Citation2021; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; McColgan & Schofield, Citation2007; Muraco et al., Citation2018; Parks et al., Citation2011; Putney, Citation2014; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011; Williams, Citation2018).

Participants in some studies described the bond they felt with their pet as one of unconditional love. Pets were perceived to be non-judgmental and always available (Chur-Hansen et al., Citation2009; Cole, Citation2019; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Muraco et al., Citation2018; Parks et al., Citation2011; Putney, Citation2014).

Older adults in the reviewed studies indicated that their pets relied on them for care and, in return, they relied on the support and affection of their pets. Therefore, the bond with the pet can be characterised as one of interdependence (Chur-Hansen et al., Citation2009; Cole, Citation2019; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; McColgan & Schofield, Citation2007; Muraco et al., Citation2018; Parks et al., Citation2011; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011).

Reflection and meaning

Four themes associated with beliefs and thoughts about pets—attribution of feelings, memories, sense of achievement, and meaning of life—were placed under the category reflection and meaning. Some older adults attributed (human-like) feelings to their pets, saying, for instance, that their pets understood them when they spoke to them (Chen et al., Citation2020; Cole, Citation2019; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Parks et al., Citation2011; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011; Williams, Citation2018).

Some people saved mementos of their pets, such as photographs, which they considered especially valuable after the pet had died. The included publications described several examples of memories of pets, including descriptions of pets being associated in memory with deceased family members or children who had moved away (Bunkers, Citation2010; Parks et al., Citation2011; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011).

Caring for pets was perceived as meaningful and rewarding, and participants reported feeling a sense of achievement from taking care of their pet. They also described qualities required to be a good caregiver, like being responsible (Chen et al., Citation2020; Cole, Citation2019; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Parks et al., Citation2011; Putney, Citation2014; Williams, Citation2018).

Some older adults perceived their pets as giving life a sense of meaning (meaning of life). In the studies, this was related to the responsibility of taking care of another living being and the belief that it is impossible to live without a pet’s support (Chen et al., Citation2020; Chur-Hansen et al., Citation2009; Cole, Citation2019; Cryer et al., Citation2021; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Putney, Citation2014; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011).

Emotional aspects

The category emotional aspects contains four themes related to the feelings and emotions of pet owners: responsiveness to feelings, emotional support, pleasure, and grief. The studies described older adults who experienced pets as responsive to their feelings when they were in a bad mood, ill, or in pain (Chen et al., Citation2020; Cole, Citation2019; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Muraco et al., Citation2018; Parks et al., Citation2011; Putney, Citation2014; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011; Williams, Citation2018). Some participants reported that pets provided emotional support and comfort during times of emotional distress, such as during depression (Chen et al., Citation2020; Cole, Citation2019; Cryer et al., Citation2021; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; McColgan & Schofield, Citation2007; Muraco et al., Citation2018; Parks et al., Citation2011; Williams, Citation2018).

Pet ownership seemed to be experienced as pleasurable, with several participants reporting that they undertook fun activities with their pets, and that their pets made them laugh (Chen et al., Citation2020; Cole, Citation2019; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Williams, Citation2018).

Some participants described periods of grief related to owning a pet—for instance, when they had to have a pet euthanised. Descriptions underscored the challenging nature of these moments, the difficulty of making such a decision, and the lack of understanding one sometimes faced when other people did not understand the grief that resulted from a pet’s death (Chur-Hansen et al., Citation2009; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Parks et al., Citation2011; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011).

Aspects of caregiving

The category aspects of caregiving comprises five themes related to the positive and negative aspects of caring for a pet: need of caregiving, responsibility, sense of safety, expenses, and worries. In the articles, older adults often displayed a need of caregiving and indicated that caregiving provided them with an opportunity to focus on something other than themselves (Chur-Hansen et al., Citation2009; Cole, Citation2019; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Parks et al., Citation2011; Putney, Citation2014; Williams, Citation2018). However, some older adults needed help from others to care for their pets (Cryer et al., Citation2021; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Putney, Citation2014).

Pets sometimes provide a sense of safety. For instance, a barking dog may warn its owner of potential break-ins (Cryer et al., Citation2021; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Parks et al., Citation2011).

Responsibility is an aspect of caregiving. Some participants made plans for their pets in case of their own death or a possible move to a nursing home. Responsibility involved sacrifices, such as not being away from home for too long (Chen et al., Citation2020; Chur-Hansen et al., Citation2009; Cole, Citation2019; Cryer et al., Citation2021; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Muraco et al., Citation2018; Parks et al., Citation2011; Putney, Citation2014; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011; Williams, Citation2018).

Participants also expressed worries related to caregiving. For instance, some older adults considered postponing hospitalisation if they had no trustworthy person to take care of their pet (Chur-Hansen et al., Citation2009; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Putney, Citation2014; Williams, Citation2018). Other worries included pet health, anticipation of a pet’s death, pet-related complaints (e.g. noise complaints), and an increased risk of falls due to the pet (Chen et al., Citation2020; Cole, Citation2019; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Muraco et al., Citation2018; Putney, Citation2014).

Caring for a pet can be expensive. The studies provided examples of pet-related expenses such as veterinary care, food, and dog walking services. For those on a limited budget, such expenses could prove quite challenging (Chur-Hansen et al., Citation2009; Cole, Citation2019; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Putney, Citation2014; Williams, Citation2018).

Physical health

The category physical health consists of five themes that reflect the pets’ influence on the health of the owner: exercise, daily routine, distraction from physical pain, relaxation and medical detection. Overall, participants believed that their pets were beneficial for their physical health, mainly through additional exercise. Examples of exercise included walking the dog and cleaning the cat’s litter box. The pet was viewed as motivator to exercise because pet-related ‘chores’ had to be performed (Chen et al., Citation2020; Chur-Hansen et al., Citation2009; Cole, Citation2019; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Muraco et al., Citation2018; Parks et al., Citation2011; Putney, Citation2014; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011; Williams, Citation2018).

Older adults said that pets imposed a daily routine, such as getting up early in the morning to walk the dog (Chen et al., Citation2020; Cole, Citation2019; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; McColgan & Schofield, Citation2007; Muraco et al., Citation2018; Putney, Citation2014; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011; Williams, Citation2018).

Older adults reported that focusing attention on their pets distracted attention from their own physical pain (Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014), and this this helped them to relax (Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Williams, Citation2018).

Some participants reported that their pets noticed when they were not feeling well or were in pain, and some perceived their pets warning them of upcoming medical events. This is known as medical detection (Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011). In one report, a participant perceived her dog to bark before she had an epileptic seizure.

Social aspects

The category social aspects refers to the pets’ influence on the social environments of older adults and contains three themes: feelings of loneliness, and active or passive social facilitation. Older adults mentioned that pets reduced feelings of loneliness. A few older adults indicated that their pet was the only company they had for several consecutive days (Bunkers, Citation2010; Chen et al., Citation2020; Cole, Citation2019; Cryer et al., Citation2021; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Parks et al., Citation2011; Putney, Citation2014; Williams, Citation2018).

Additionally, the studies contained reports of active or passive social facilitation, where pets connected their owner to other people. Examples of active social facilitation included meeting people while walking the dog, and joining a virtual (e.g. Facebook) or physical (e.g. dog walking) community (Chen et al., Citation2020; Cole, Citation2019; Cryer et al., Citation2021; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Muraco et al., Citation2018; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011; Williams, Citation2018). Passive social facilitation included receiving invitations to events from people met during activities with a pet, and visitors who stopped by to interact with the pet (Chen et al., Citation2020; Cole, Citation2019; Cryer et al., Citation2021; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Putney, Citation2014; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011; Williams, Citation2018).

Bidirectional behaviour

The category bidirectional behaviour describes how owners and pets behave towards one another. The four themes grouped under this category include responsiveness to behaviour, mirroring, physical contact, and proximity. Descriptions of interactions and routines showed that older adults and their pets were responsive towards each other’s behaviour. Some participants said they became more aware of their surroundings because pets also responded to their environment (Chen et al., Citation2020; Cole, Citation2019; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Parks et al., Citation2011; Putney, Citation2014; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011; Williams, Citation2018).

A theme related to responsiveness is mirroring. Some participants described seeing their own personality traits reflected in their pets (Cole, Citation2019; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Hui Gan et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Parks et al., Citation2011; Putney, Citation2014; Scheibeck et al., Citation2011).

Participants also mentioned physical contact with their pets. Older adults hugged and petted their animals, and pets actively sought to be touched by their owner (Chen et al., Citation2020; Chur-Hansen et al., Citation2009; Cole, Citation2019; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Williams, Citation2018).

Proximity is related to physical contact. Most older adults indicated that they liked to be close to their pets and sometimes slept in the same bed (Chen et al., Citation2020; Chur-Hansen et al., Citation2009; Enders-Slegers, Citation2000; Janevic et al., Citation2020; Johansson et al., Citation2014; Williams, Citation2018).

Discussion

This review provided themes to better understand the significance and roles of pets from the perspective of their older adult owners. We identified the following categories: relational aspects, reflection and meaning, emotional aspects, aspects of caregiving, physical health, social aspects, and bidirectional behaviour, that together comprised twenty-eight themes.

Overall, older adults reported that their pets reduced feelings of loneliness and helped them meet other people (social aspects). Several studies support the idea that animals, mainly dogs, reduce feelings of loneliness and facilitate conversations and connections to others (e.g. Hajek & Konig, Citation2020; Stanley et al., Citation2014; Wood et al., Citation2015). However, there is also evidence that it may mainly be women who acquire a pet as a response to feelings of loneliness (Pikhartova et al., Citation2014). These studies imply that pets can reduce subjective feelings of loneliness and can help against social isolation by facilitating social contacts. Feelings of loneliness and social isolation are risk factors for experiencing psychological distress and insufficient social support (Menec et al., Citation2020). However, quantitative studies investigating the effects of pets on loneliness do not provide consistent evidence (Gilbey & Tani, Citation2015).

Regarding mental health, Stammbach and Turner (Citation1999) found in their quantitative study that pets are a source of emotional support (emotional aspects), which is linked to the strength of attachment (relational aspects). There is increasing evidence suggesting that the positive effects of pet ownership are mainly the result of the strength of attachment to a pet (Enders-Slegers & Hediger, Citation2019).

Older adults perceived their pets to be beneficial to their physical health. However, quantitative studies on this subject have contradictory outcomes. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses that investigated the effects of pet ownership on cardiovascular risks and all-cause mortality show mixed results (e.g. Bauman et al., Citation2020; Mubanga et al., Citation2017; Yeh et al., Citation2019). A large longitudinal study found that dogs are associated with reduced cardiovascular risk and all-cause mortality, but that the type of dog and type of household (single-household) also play a role (Mubanga et al., Citation2017). Studies that used an accelerometer to investigate the effects of pets on physical activity found that dog owners were more likely to meet physical activity recommendations (Coleman et al., Citation2008; Feng et al., Citation2014). However, a meta-analysis that investigated the relationship between pet ownership and obesity found no significant relationship. Nevertheless, the negative relationship between walking and obesity suggests a positive effect of walking with a pet (Miyake et al., Citation2020).

Our review suggests that, next to the positive effects of pets, the negative aspects of pet ownership by older adults need to be accounted for. For example, negative emotional aspects such as grief and certain aspects of caregiving such as worries and expenses are issues that cannot be neglected. Another potentially negative aspect of caregiving is that older adults receiving home care may rely on others to care for their pets. Bibbo and Proulx (Citation2018) found in a quantitative study that informal caregivers spent an average of 11.2 h per week on pet-related chores. This may lead to additional caregiver burden. However, a follow-up study found that additional burden in caregivers was mitigated when the care recipient and caregiver had a good relationship (Bibbo & Proulx, Citation2019). Nevertheless, because additional pet care may exacerbate caregiver burden this topic needs attention from healthcare organisations.

While qualitative studies report positive evaluations of pet ownership, outcomes from quantitative studies seem inconclusive and contradictory (Friedmann & Gee, Citation2019; Gilbey & Tani, Citation2015). This could be due to methodological limitations of quantitative research such as using a cross-sectional design, not matching groups of participants, and difficulty conceptualising outcome measures (e.g. pet attachment) (Friedmann & Gee, Citation2019; Gilbey & Tani, Citation2015). Also, some effects may be more profound in specific groups (Gilbey & Tani, Citation2015). For instance, homebound older adults receiving home care may benefit more from pet companionship than someone with an active lifestyle. This suggests that research related to the effects of pets may benefit from using mixed-methods designs, which collect both quantitative and qualitative data, adding in-depth understanding of the investigated phenomena.

Implications for practice

Our results lead to several important considerations for healthcare organisations. First of all, some older adults reported not being able to live without their pet (reflection and meaning). Second, some older adults had no network they could rely on to take care of their pet if they themselves were unable to do so (e.g. due to hospitalisation). This could lead to older adults delaying medical treatment (e.g. Canady & Sansone, Citation2019). Currently, care workers may be hindered in helping their clients in these situations due to a lack of existing guidelines and prescribed procedures (Toohey et al., Citation2017).

Guidelines and instruments like posters, brochures, and checklists can improve care workers’ awareness of the role of pets in clients’ lives. Some specific pet-related topics can be discussed with clients to explore (potential) challenges they face such as pet expenses (e.g. veterinary care), informal caregiver burden, and future health deterioration. Care workers’ support in identifying and anticipating challenges could improve wellbeing for both clients and their pets.

Strengths, limitations, and future research

A first strength of this qualitative systematic review was that by focussing on qualitative studies regarding pet ownership of older adults, the study contributed to better understanding of older adults’ everyday subjective experiences (Cypress, Citation2015). A second strength is that we integrated the outcomes of fifteen studies with a large total number of participants. A third strength was that the data was analysed and discussed within a team, which helped us reach consensus while allowing for reflexivity.

A limitation is that we were not able to specifically focus on studies investigating older adults receiving home care. Thus, it is uncertain if all of the findings in this review apply to older adults receiving home care. Nonetheless, we believe that broadening the scope of our study was justified. Although the results need to be confirmed in those receiving home care, the study results can be informative for the development of guidelines and instruments related to pets in the home care context. A second limitation is that most of the study participants owned dogs. Therefore, it is unclear if the experiences of the older adults are similar to owners of other types of pets.

Future research should verify our findings in older adults receiving home care specifically. However, our results are supported by a recently published case study about an older adult who owned a dog and received home care (Obradović et al., Citation2021). Still, more research, including longitudinal studies, are needed to explore whether the identified aspects of pet ownership indeed have causal effects—for instance, on the quality of life or functional independence of older adults receiving home care.

Conclusion

According to older adults’ own experiences, pets play an important and positive role in their lives. Older adults reported additional social connections, emotional support, and physical activities resulting from pet ownership. However, the older adults in the reviewed studies also reported some negative aspects of pet ownership. Both the positive and negative experiences highlight the importance of considering pets in the care system of older adults receiving home care. More research can verify the categories and themes proposed in this review in the home care context. The outcomes can serve as a conceptual framework to develop guidelines and tools, preferably in collaboration with stakeholders such as recipients of home care that own pets, family caregivers, and representatives of home care organisations.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbing, H. R. (2016). Health, healthcare and ageing populations in Europe, a human rights challenge for European health systems. European Journal of Health Law, 23(5), 435–452. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718093-12341427

- Amiot, C., Bastian, B., & Martens, P. (2016). People and companion animals: It takes two to tango. BioScience, 66(7), 552–560. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biw051

- Applebaum, J. W., Peek, C. W., & Zsembik, B. A. (2020). Examining U.S. pet ownership using the General Social Survey. The Social Science Journal, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/03623319.2020.1728507

- Bauman, A., Owen, K. B., Torske, M. O., Ding, D., Krokstad, S., & Stamatakis, E. (2020). Does dog ownership really prolong survival?: A revised meta-analysis and reappraisal of the evidence. Circulation. Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 13(10), e006907. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006907

- Beck, A. M., & Katcher, A. H. (2003). Future directions in human-animal bond research. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764203255214

- Bedford, E. (2021). Pet ownership in the U.S. – Statistics & facts. Statista. Retrieved 6 October from https://www.statista.com/topics/1258/pets/

- Bibbo, J., & Proulx, C. M. (2018). The impact of a care recipient’s pet on the instrumental caregiving experience. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 61(6), 675–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2018.1494659

- Bibbo, J., & Proulx, C. M. (2019). The impact of a care recipient’s pet on caregiving burden, satisfaction, and mastery: A pilot investigation. Human-Animal Interaction Bulletin, 7(2), 81–102.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bunkers, S. S. (2010). The lived experience of feeling sad. Nursing Science Quarterly, 23(3), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894318410371831

- Canady, B., & Sansone, A. (2019). Health care decisions and delay of treatment in companion animal owners. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 26(3), 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-018-9593-4

- Chen, X., Zhu, H., & Yin, D. (2020). Everyday life construction, outdoor activity and health practice among urban empty nesters and their companion dogs in Guangzhou, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114091

- Chur-Hansen, A., Winefield, H. R., & Beckwith, M. (2009). Companion animals for elderly women: The importance of attachment. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 6(4), 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780880802314288

- Cole, A. (2019). Grow old along with me: The meaning of dogs in seniors’ lives. International Journal of Community Well-Being, 2(3–4), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42413-019-00034-w

- Coleman, K. J., Rosenberg, D. E., Conway, T. L., Sallis, J. F., Saelens, B. E., Frank, L. D., & Cain, K. (2008). Physical activity, weight status, and neighborhood characteristics of dog walkers. Preventive Medicine, 47(3), 309–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.05.007

- Cryer, S., Henderson-Wilson, C., & Lawson, J. (2021). Pawsitive Connections: The role of Pet Support Programs and pets on the elderly. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 42, 101298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101298

- Cypress, B. S. (2015). Qualitative research: The "what," "why," "who," and "how"!. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing: DCCN, 34(6), 356–361. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000150

- Dowsett, E., Delfabbro, P., & Chur-Hansen, A. (2020). Adult separation anxiety disorder: The human-animal bond. Journal of Affective Disorders, 270, 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.147

- Enders-Slegers, M.-J. (2000). The meaning of companion animals: Qualitative analysis of the life histories of elderly cat and dog owners. In A. L. Podberscek, E. S. Paul, & J. A. Serpell (Eds.), Companion animals and us: Exploring the relationships between people and pets (pp. 237–256). Cambridge University Press.

- Enders-Slegers, M.-J., & Hediger, K. (2019). Pet ownership and human–animal interaction in an aging population: Rewards and challenges. Anthrozoös, 32(2), 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2019.1569907

- EUnetHTA. (2019). Process of information retrieval for systematic reviews and health technology assessments on clinical effectiveness. EUnetHTA.

- FEDIAF. (2019). Facts & figures 2019 European overview. https://fediaf.org/images/FEDIAF_facts_and_figs_2019_cor-35-48.pdf

- Feng, Z., Dibben, C., Witham, M. D., Donnan, P. T., Vadiveloo, T., Sniehotta, F., Crombie, I. K., & McMurdo, M. E. (2014). Dog ownership and physical activity in later life: A cross-sectional observational study. Preventive Medicine, 66, 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.06.004

- Frandsen, T. F., Bruun Nielsen, M. F., Lindhardt, C. L., & Eriksen, M. B. (2020). Using the full PICO model as a search tool for systematic reviews resulted in lower recall for some PICO elements. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 127, 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.07.005

- Friedmann, E., & Gee, N. R. (2019). Critical review of research methods used to consider the impact of human–animal interaction on older adults’ health. The Gerontologist, 59(5), 964–972. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx150

- Friedmann, E., Gee, N. R., Simonsick, E. M., Studenski, S., Resnick, B., Barr, E., Kitner-Triolo, M., & Hackney, A. (2020). Pet ownership patterns and successful aging outcomes in community dwelling older adults [original research]. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 293. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00293

- Gee, N. R., Mueller, M. K., & Curl, A. L. (2017). Human-animal interaction and older adults: An overview. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1416. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01416

- Gilbey, A., & Tani, K. (2015). Companion animals and loneliness: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Anthrozoös, 28(2), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2015.11435396

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Hajek, A., & Konig, H. H. (2020). How do cat owners, dog owners and individuals without pets differ in terms of psychosocial outcomes among individuals in old age without a partner? Aging & Mental Health, 24(10), 1613–1619. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1647137

- HAS. (2015). Feiten & Cijfers: Gezelschapsdierensector 2015. (https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2015/11/03/feiten-cijfers-gezelschapsdierensector-2015

- Himsworth, C. G., & Rock, M. (2013). Pet ownership, other domestic relationships, and satisfaction with life among seniors: Results from a Canadian National Survey. Anthrozoös, 26(2), 295–305. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303713X13636846944448

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fabregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M. P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M. C., & Vedel, I. (2019). Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: A modified e-Delphi study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 111, 49–59 e41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.008

- Hughes, M. J., Verreynne, M. L., Harpur, P., & Pachana, N. A. (2020). Companion animals and health in older populations: A systematic review. Clinical Gerontologist, 43(4), 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2019.1650863

- Hui Gan, G. Z., Hill, A. M., Yeung, P., Keesing, S., & Netto, J. A. (2020). Pet ownership and its influence on mental health in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 24(10), 1605–1612. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1633620

- Janevic, M. R., Shute, V., Connell, C. M., Piette, J. D., Goesling, J., & Fynke, J. (2020). The role of pets in supporting cognitive-behavioral chronic pain self-management: Perspectives of older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 39(10), 1088–1096. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464819856270

- Johansson, M., Ahlstrom, G., & Jonsson, A. C. (2014). Living with companion animals after stroke: Experiences of older people in community and primary care nursing. British Journal of Community Nursing, 19(12), 578–584. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2014.19.12.578

- Lipszyc, B., Sail, E., & Xavier, A. (2012). Long-term care: Need, use and expenditure in the EU-27. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications.

- McColgan, G., & Schofield, I. (2007). The importance of companion animal relationships in the lives of older people. Nursing Older People, 19(1), 21–23. https://doi.org/10.7748/nop2007.02.19.1.21.c4361

- Menec, V. H., Newall, N. E., Mackenzie, C. S., Shooshtari, S., & Nowicki, S. (2020). Examining social isolation and loneliness in combination in relation to social support and psychological distress using Canadian Longitudinal Study of Aging (CLSA) data. PLoS One, 15(3), e0230673. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230673

- Miyake, K., Kito, K., Kotemori, A., Sasaki, K., Yamamoto, J., Otagiri, Y., Nagasawa, M., Kuze-Arata, S., Mogi, K., Kikusui, T., & Ishihara, J. (2020). Association between pet ownership and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3498. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103498

- Mubanga, M., Byberg, L., Nowak, C., Egenvall, A., Magnusson, P. K., Ingelsson, E., & Fall, T. (2017). Dog ownership and the risk of cardiovascular disease and death - A nationwide cohort study. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 15821. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16118-6

- Mueller, M. K., Gee, N. R., & Bures, R. M. (2018). Human-animal interaction as a social determinant of health: Descriptive findings from the health and retirement study. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 305. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5188-0

- Muraco, A., Putney, J., Shiu, C., & Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I. (2018). Lifesaving in every way: The role of companion animals in the lives of older lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults age 50 and over. Research on Aging, 40(9), 859–882. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027517752149

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 160940691773384. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Obradović, N., Lagueux, É., Latulippe, K., & Provencher, V. (2021). Understanding the benefits, challenges, and the role of pet ownership in the daily lives of community-dwelling older adults: A case study. Animals, 11(9), 2628. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/11/9/2628 https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11092628

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan - A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Parks, B., Thies, G., Harris, D., Stockton, P., & Thomason, N. L. (2011). Pets for older people: A matter of value. Interview by Marian Brickner. Care Management Journals, 12(3), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1891/1521-0987.12.3.115

- Pikhartova, J., Bowling, A., & Victor, C. (2014). Does owning a pet protect older people against loneliness? BMC Geriatrics, 14, 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-14-106

- Putney, J. M. (2014). Older lesbian adults’ psychological well-being: The significance of pets. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 26(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2013.866064

- Rauktis, M. E., & Hoy-Gerlach, J. (2020). Animal (non-human) companionship for adults aging in place during COVID-19: A critical support, a source of concern and potential for social work responses. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(6–7), 702–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2020.1766631

- Risley-Curtiss, C. (2010). Social work practitioners and the human-companion animal bond: A national study. Social Work, 55(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/55.1.38

- RIVM. (2021). Aantal Mensen met Chronische Aandoening Bekend bij de Huisarts. https://www.volksgezondheidenzorg.info

- Rodriguez, K. E., Herzog, H., & Gee, N. R. (2020). Variability in human-animal interaction research. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 619600. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.619600

- Ryan, S., & Ziebland, S. (2015). On interviewing people with pets: Reflections from qualitative research on people with long-term conditions. Sociology of Health & Illness, 37(1), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12176

- Scheibeck, R., Pallauf, M., Stellwag, C., & Seeberger, S. (2011). Elderly people in many respects benefit from interaction with dogs. European Journal of Medical Research, 16(12), 557–563. https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-783x-16-12-557

- Spasova, S., Baeten, R., Coster, S., Ghailani, D., Peña-Casas, R., & Vanhercke, B. (2018). Challenges in long-term care in Europe: A study of national policies 2018. European Commission.

- Stammbach, K. B., & Turner, D. C. (1999). Understanding the human-cat relationship: Human social support or attachment. Anthrozoös, 12(3), 162–168. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279399787000237

- Stanley, I. H., Conwell, Y., Bowen, C., & Van Orden, K. A. (2014). Pet ownership may attenuate loneliness among older adult primary care patients who live alone. Aging & Mental Health, 18(3), 394–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.837147

- Toohey, A. M., Hewson, J. A., Adams, C. L., & Rock, M. J. (2017). When places include pets: Broadening the scope of relational approaches to promoting aging-in-place. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 44(3), 119–146. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/jrlsasw44&i=493

- Toray, T. (2004). The human-animal bond and loss: Providing support for grieving clients. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 26(3), 244–259. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.26.3.udj040fw2gj75lqp

- Williams, J. H. (2018). The relationships between older physically impaired males and their pets. ProQuest Information & Learning. APA PsycInfo. https://login.ezproxy.elib11.ub.unimaas.nl/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2018-26098-192&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Winefield, H. R., Black, A., & Chur-Hansen, A. (2008). Health effects of ownership of and attachment to companion animals in an older population. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(4), 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802365532

- Wood, L., Martin, K., Christian, H., Nathan, A., Lauritsen, C., Houghton, S., Kawachi, I., & McCune, S. (2015). The pet factor–companion animals as a conduit for getting to know people, friendship formation and social support. PLoS One, 10(4), e0122085. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122085

- Yeh, T. L., Lei, W. T., Liu, S. J., & Chien, K. L. (2019). A modest protective association between pet ownership and cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 14(5), e0216231. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216231

Appendix

Table A1. Summary of the applied search strategies.

Table A2. Quality assessment (mixed-methods appraisal tool).