Abstract

Objective

A tablet app, based on the Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate-II (PACSLAC-II), has been shown to have clinical utility and unique advantages. We aimed to replicate and extend the previous validation of the app through the implementation and evaluation of a new community platform involving a quality indicator (QI) monitoring feature and a resource community portal (CP) that work in conjunction with an updated version of the app.

Methods

We employed a mixed-methods multiple-baseline design across 11 long-term care (LTC) units. Units were randomly assigned to conditions which varied in number of app features available. Data included unit-level QIs as well as questionnaires and semi-structured interviews with health professionals.

Results

Following use of the app, we found improvements in unit-level QIs regardless of availability of the QI/CP features. During interviews, participants expressed a preference for the app over a paper version of the PACSLAC-II due to reasons such as the app’s ability to summarize information. Utilization of the community portal websites was unrelated to staff questionnaire-assessed stress/burnout.

Conclusions

Despite the positive effects on the care of residents, the COVID-19 pandemic presented challenges and interfered with the long-term maintenance of the QI results.

Introduction

Related to the limitations in ability to communicate that accompany moderate to severe dementia, pain is often underassessed and under-addressed amongst older adults in long-term care (LTC; Jonsdottir & Gunnarsson, Citation2021), a large portion of whom have dementia and persistent pain (Kao et al., Citation2022; Thomas et al., Citation2020). Resident pain negatively affects healthcare professionals contributing to caregiver stress and burnout (Costello et al., Citation2019). Challenging behaviors exhibited by many residents with dementia and the potential difficulties in identifying their pain may cause healthcare professionals to experience uncertainty about resident treatment needs (Jonsdottir & Gunnarsson, Citation2021) with this uncertainty contributing to burnout. Frequent LTC pain assessments have been shown to improve resident care while at the same time reducing stress and burnout for nursing staff (Fuchs-Lacelle et al., Citation2008). Pain assessments could reduce burnout (Fuchs-Lacelle et al., Citation2008) if they led to increases in caregiver confidence in managing resident distress (Ashton-James et al., Citation2021). Moreover, frequent pain assessments could also have a positive impact on staff burnout through the possible reduction in resident responsive behaviors that frequently result from pain (Atee et al., Citation2021; Fuchs-Lacelle et al., Citation2008).

PACSLAC-II

An observational assessment tool that has well established psychometric properties in assessing pain in dementia is the Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate-II (PACSLAC-II; Chan et al., Citation2014; Hadjistavropoulos et al., Citation2018). Previous LTC studies have demonstrated that use of the PACSLAC-II has resulted in improved pain care (e.g. Hadjistavropoulos et al., Citation2016; Zahid et al., Citation2020).

In line with other work focusing on implementation of electronic measurement of health-related data (e.g. Lam et al., Citation2021; Ng et al., Citation2022), an app version of the PACSLAC-II has been developed and allows for easy tracking of pain fluctuations over time (Zahid et al., Citation2020). Unlike many mHealth apps created specifically for pain (Portelli & Eldred, Citation2016), the PACSLAC-II app is based on a validated method, its targeted clinical population consists of older adults who are living in LTC and is specifically designed for healthcare professionals. Zahid et al. (Citation2020) found improvements in pain assessment frequency when the app was implemented in LTC. Moreover, use of the PACSLAC-II app was associated with lower stress and burnout among care staff, compared to use of a paper version of the PACSLAC-II, although these results were not maintained during the follow-up period. Nonetheless, staff expressed a preference for the PACSLAC-II app compared to the paper version (Zahid et al., Citation2020).

Some mHealth apps allow patients and caregivers to seek information and gain social support from other users. Similar social support communities but for healthcare professionals are referred to as virtual communities of practice (vCOPS). vCOPs provide users with opportunities to collaborate and find solutions for work-related problems, and for sharing the results of these collaborations across multiple organizations (Shaw et al., Citation2022). In the realm of mHealth and pain, there are very few apps that offer a platform for social support (Lalloo et al., Citation2017). As this social support and community may potentially achieve positive health-related outcomes (i.e. improved pain quality indicators; QIs; ) in their specific target populations (e.g. Ford et al., Citation2015), we explored the integration of an mHealth community with an internet resource community portal (CP) as a tool for healthcare professionals. The CP was comprised of two features: a QI website to allow healthcare professionals to share their QI scores with other facilities, and a resource aimed at facilitating user interaction, the sharing of knowledge, and continuing education. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the effects of an app-based community platform on LTC health professionals’ questionnaire-assessed stress/burnout as well as their self-reported experiences using the platform.

Table 1. Pain quality indicators (based on Hadjistavropoulos et al., Citation2009).

Purpose

We implemented and evaluated a new community platform on the PACSLAC-II app. This work is a replication and extension of Zahid and associates’ (2020) study. Specifically, Zahid et al. (Citation2020) examined the clinical feasibility of an earlier version of the PACSLAC-II app. Our objectives were to: 1) evaluate LTC unit-wide pain QI scores (e.g. % of residents assessed for pain at least weekly) with the updated app and new community platform; 2) evaluate the impact of the associated community portal resources on healthcare professionals’ questionnaire-assessed stress and burnout levels; and 3) gain an understanding of healthcare professionals’ experiences and perspectives on the use of the app and its associated websites through analysis of interview responses.

Based on the job demands-resources model (JD-R; Bakker & de Vries, Citation2021), the PACSLAC-II app and its associated community portal features presumably act as job resources for the healthcare professionals and could work to offset job demands and the challenge of assessing pain in residents with limited ability to communicate. Therefore, it was anticipated that LTC units that were randomly assigned to the app and both CP features would see the most positive gains including reduced questionnaire-assessed staff stress, as well as increased QI scores and interview-assessed staff satisfaction with the app due to access to the extra resources available to them (e.g. educational material, relative performance feedback etc.). This would be followed by units that were randomly assigned to the app and only one feature, and lastly by units assigned to the PACSLAC-II app with no additional features.

Methods

Participating LTC units

Following ethics clearance from our institutional review board (#2020-210), eleven LTC units participated with each unit acting as an independent case series. The number of units was established to ensure a counterbalanced design and to maintain a minimum of two units for each of five study conditions which varied with respect to the combination and sequencing of app features available (i.e. app with no features, the QI app-associated website and/or the resource aimed to facilitate knowledge sharing and participant interaction; see Procedure section). All 11 units were located in two mid-sized metropolitan cities. They ranged in size from 22—65 beds (). Six units were located within one facility (A, D, F, G, J, K), two within another facility (B & H), and three were from separate facilities (C, E, I). Care was taken to ensure that there was minimal or no overlap of staff among participating units. Unit D discontinued halfway through the study due to multiple reported COVID-19 outbreaks and subsequent staff shortages.

Table 2. Quality indicator (QI) scores for all units.

A Pain Champion (a senior nurse with an interest in pain assessment) was appointed by each unit as previous research has demonstrated that having a designated Pain Champion facilitates pain management/assessment implementation (Hadjistavropoulos et al., Citation2016; Kaasalainen et al., Citation2016; Zahid et al., Citation2020). The Pain Champion helped oversee the implementation protocol and support the use of the PACSLAC-II app and CP throughout the study. While we did not record the amount of time that Pain Champions spent each week on the study, it is our best estimate, based on informal discussions, that they devoted 2–5 h per week. The number of hours varied primarily as a function of study phase with the most time spent during the first week or two of the assessment phase of the study at each facility.

Questionnaire and interview participants

Healthcare professionals from participating units were invited to share their experiences using the app and to provide demographic information, questionnaire responses, and participate in an interview. Participants who completed both self-report measures received a $10 gift card for each set of questionnaires and a $20 gift card for the interview. The final sample included 34 individuals who completed the questionnaires and 32 participants in semi-structured interviews. Participants had an average age of 43.4 years (SD = 12.9), had worked for an average of 11.4 years in LTC (SD = 7.2) and 85% were female. Seventy one percent were nurses and the remaining were care aides (See Supplementary Online Appendix A for a detailed breakdown).

Materials

PACSLAC-II App

Unlike the previous version of the app, which was designed to be a simple adaptation of the paper PACSLAC-II (Zahid et al., Citation2020), this version was modified to enhance users’ experience with an updated interface. The updated version of the PACSLAC-II was developed for the Android operating system. Two computer tablets were provided to each LTC unit. The use of private servers, encryption through HTTPS, and firewall protection were established to ensure that data collected from the app were securely stored. Additionally, a two-step verification process was employed to ensure resident confidentiality. Contextual information was added to the updated version of the app such as assessment duration and observed resident activity, allowing for more accurate assessments. The app automatically stored the checklist scores for each assessment and graphed the scores of multiple assessments over time for the same resident. Additionally, the app compiled all resident assessment administrations including which pain behaviors were observed, creating a comprehensive assessment history for each resident (Zahid et al., Citation2020). To ease the integration of the PACSLAC-II app reports with paper record-keeping practices, an option to email the pain graph and residents’ assessment history was available so that the information could be easily printed and added to residents’ charts (Zahid et al., Citation2020). Nurses and supervised care aides used the PACSLAC-II app. However, nurses were responsible for the supervision, interpretation of the assessments as well as clinical decision-making.

Feature 1: Quality indicator website

The pain assessment quality indicators (QIs) in this feature (see ) are based on previous work (e.g. Gallant et al., Citation2022; Hadjistavropoulos et al., Citation2009; Citation2016). These QIs were collected automatically by the app on a real-time basis. This QI feature was accessed through a separate website via a link on the app so that the QIs themselves could not be viewed on the app. Participants assigned to the QI website created their own accounts to use the website and gained access as the study progressed. Access to the website was controlled by the researchers to ensure that participants in the app-only condition did not have access to these QIs. Pain Champions were asked to regularly update their resident list to ensure accurate QI calculations. The QIs were presented to participants in several ways through graphs, visuals, and interactive maps. Participants were able to see their facility’s QIs compared to other individual facilities’ scores. Participants were also able to see changes in their QI scores over time.

Feature 2: Community portal website

The CP feature was created to encourage a culture of sharing information and facilitate success of the mHealth community (Spallek et al., Citation2008). Continuing education materials were available to the participants through a separate website accessible through the app. This was to ensure that participants in the app-only condition did not have access to these resources. Participants were asked to create individual accounts to access the website and access authorization was monitored by the researchers. Resources included educational videos, links to relevant literature, best practice recommendations, and user toolkits. All participants had the ability to upload resources to share with other users. Users were also able to comment on and discuss individual resources. In addition, participants could easily create forums to discuss relevant pain management practices. Pain Champions in the facility were asked, as part of their role, to encourage the use of the CP website and help to promote discussion of the resources in their unit as well. Activity on the website was monitored throughout the study.

Measures

Participant demographic information

Healthcare professionals who consented to be part of the evaluation portion of the study provided basic demographic information (e.g. age, years of experience, professional designation).

QI scores

The QIs () are objective measurements of the performance of each LTC unit regarding the frequency of their pain assessment practices. These QIs are based on recommended clinical guidelines developed by pain and public policy experts (Hadjistavropoulos et al., Citation2009) and have been used successfully in prior research on the implementation of pain assessment in LTC (e.g. Gallant et al., Citation2022; Hadjistavropoulos et al., Citation2016; Zahid et al., Citation2020).

Maslach burnout inventory

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981) consists of 22 items focusing on experiences or situations healthcare professionals may face. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). The MBI contains three subscales: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment. Low scores on the personal accomplishment subscale and higher scores on the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales indicate higher perceived burnout. Overall, the MBI has demonstrated good psychometric properties including in LTC (Fuchs-Lacelle et al., Citation2008; Shoman et al., Citation2021; Zahid et al., Citation2020). In the present study, internal consistency was satisfactory for emotional exhaustion (α = .90) and depersonalization (α = .72) but unsatisfactory for personal accomplishment (α = .41) subscale. Hence, the latter subscale was not included in our analysis.

App and websites usage questionnaire

A brief measure created by the researchers was included in the second questionnaire package to determine the frequency of use of the PACSLAC-II app, QI website, and CP website. Participants indicated how often they used each resource by selecting one of the following: Never, 1-2 times, 3-5 times, or more than 5 times.

Individual interviews

Interviews were conducted for all LTC units in the study. These took place over the phone or in person and were audio-recorded. The interview moderator guide was adapted from Zahid and associates (2020) and followed a semi-structured approach. The interviews queried participants’ experiences using the, QI website, and CP website, perceived clinical benefits and areas of improvement. By the end of the interview process, saturation was achieved as no new information was introduced.

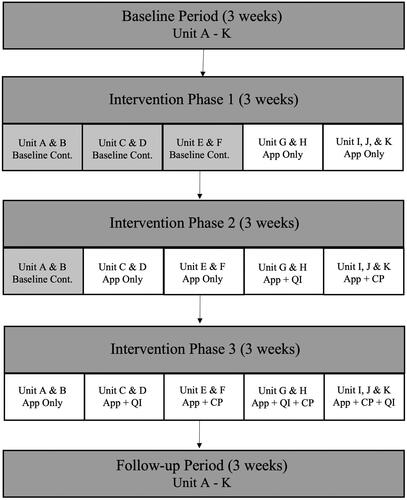

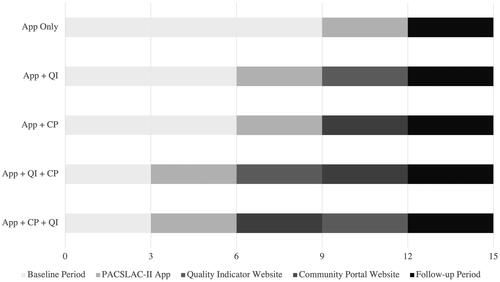

Procedure

Participating units were randomly assigned to one of the following conditions: App-only condition, App + QI, App + CP, App + QI + CP, App + CP + QI. There were three phases in this study: a baseline period, an intervention period, and a follow-up period (). During the baseline period, LTC units were asked to collect the QI data without changing their current pain management practices. The baseline period varied between three to nine weeks and was dependent on which condition the units were assigned to. Training was provided through a small group format, via videoconference or in-person, by a graduate student in clinical psychology with expertise in behavioral pain assessment and familiarity with the app. Training incorporated an implementation protocol that encouraged: a) the assessment of each resident at minimum once per week; b) intervention planning within 24 h of findings of suspected pain; c) re-assessment following implementation of intervention; and d) evaluation of possible side effects of any implemented intervention. The training also included instruction on the use of the PACSLAC-II app and each associated website. Written materials were provided to reinforce the instruction. Pain Champions, who were in regular contact with the research team, assisted other staff as issues arose. Pain Champions worked collaboratively with nursing staff to encourage and monitor the implementation process. Once a unit’s baseline period was complete, healthcare professionals, interested in sharing their experience, provided informed consent and completed the demographic information sheet and MBI.

During the intervention periods, units were asked to follow the implementation protocol described above. Pain Champions were asked to complete weekly QI sheets and send a copy to the researchers during the study period. Participating units were randomly assigned to conditions via block randomization (see ). This design allowed researchers to determine which features of the app had the most impact on the QIs, whether the order the features were presented affected outcomes measures, and whether the same results could be observed with fewer features. All eleven units were introduced to the first feature, which was the PACSLAC-II app for a three-week period. However, not every unit was subsequently introduced to the accompanying websites as the second and third features were presented in a counterbalanced fashion. Feature access was turned on for each participating unit remotely by the research team. As new features were introduced previous features such as the app were not withdrawn. New features were introduced every three weeks depending on the units’ assigned condition. The last phase of the study was a three-week follow-up period for all participating units. At the end of this follow-up period, the second round of questionnaires was administered, and individual interviews were held with care staff who had used the app and volunteered for the interviews.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the unit-level QI data. Percentages of the weekly QI data were calculated to evaluate changes throughout the study period using an applied behavior analysis approach. In applied behavior analysis, researchers are looking for large, dramatic and consistent (across units) increases in behaviors or practices that follow specific interventions or intervention components (Kazdin, Citation2021). Two regression equations were used to determine whether the use of QI and CP websites was associated with staff burnout levels after controlling for demographic characteristics (i.e. professional title, years of experience and age).

Interview responses were transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis with NVivo (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia), a qualitative data analysis software. Thematic analysis involves identifying and analyzing common themes within data, allowing researchers to capture and organize common experiences among participants (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2022). Several steps were taken to improve the trustworthiness of the data including prolonged engagement with data, the use of a coding framework, researcher triangulation (involving two coders), and the vetting of themes and subthemes by team members (O’Connor & Joffe, Citation2020). Lastly, to assist in the interpretation of the results, the primary findings for each thematic category were reported along with corresponding quotes.

Results

Unit-level quality indicator data

presents data for all units. Overall, the table shows improvements in all four QI (over 25%) during the study period, reflecting meaningful change, although these changes were not maintained through follow-up. The first QI (percentage of new residents assessed within 24 h of admission) showed the most consistent improvements in most of the units. Apart from Units A (App only condition) and K (App + CP + QI condition), 100% of new residents were assessed during the intervention phase. The second QI (percentage of residents assessed a minimum of once a week) was more variable but generally increased with some units reaching 100% of residents compared to the average baseline (0%). Gains were not maintained during the follow-up period except for Unit I (App + CP + QI condition) which continued to assess 100% of their residents weekly at three weeks follow-up. The third QI (percentage of residents with moderate-severe pain with a documented treatment plan) also had high uptake across units except for Units B (App only condition) and G (App + QI + CP). The fourth QI (percentage of residents with moderate-to-severe pain were reassessed within 24 h), was also increased except for Units A (App only condition), B (App only condition), and K (App + CP + QI condition). Although Units E & F (App + CP) had achieved high QI scores by using the app, the addition of the CP website did not appear to play a role in QI scores as scores were high throughout the study period. Overall, improvements in QI indicator scores did not appear substantially different across conditions.

Usage of app and websites

Responses from the usage of app and website questionnaire indicated that only a small portion of participants with access to the community platform features (QI website and CP website) utilized the websites. With regards to the PACSLAC-II app, 31 out of the 34 participants (91%) reported that they utilized the app more than once, while 55% indicated that they used the app more than five times during the study period. Therefore, based on this questionnaire, out of the three possible resources, the PACSLAC-II app was reportedly utilized the most, with the majority indicating that they used it more than five times, followed by the CP website at least once, and the QI website at least once.

Stress and burnout scores

Two regression equations were used to determine whether the use of QI and CP websites was associated with staff burnout levels after controlling for demographic characteristics (i.e. professional title, years of experience and age). The regression models were not statistically significant.

Thematic analysis

Interviews were coded by two researchers based on four main areas of questioning: a) LTC pain assessment and pain management practices; b) PACSLAC-II app; c) QI website; and d) CP website. Approximately 20% of the interview files were randomly selected and were initially assessed for intercoder reliability. Moderate agreement between the coders was observed, κ = 0.61. Although moderate agreement was observed, steps were taken to increase coder consensus such as refining the coding manual and utilizing a negotiated agreement approach for any identified disagreements. Another randomly selected subset of data, approximately 15% of the interviews, was evaluated utilizing the new code books. Substantial agreement between the coders was observed, κ = 0.75. Utilizing these revised code manuals, the remaining interviews were organized into thematic categories by the first and second coder. All identified disagreements underwent negotiated agreement until consensus was reached.

PACSLAC-II App

Benefits of the PACSLAC-II app

Supplementary Online Appendix B includes representative quotes for each theme. Overall, many participants reported enjoying using the PACSLAC-II app for a variety of reasons such as its design, ease of use, and convenience which allowed participants to save time when conducting pain assessments. Fifty-six percent of participants reported that having previous assessments readily available on the app allowed them to easily access residents’ graphs and summaries compared to physically searching for the information in resident charts, 56% of staff reported that the app was easy to use and intuitive due to its user-friendly design. Initial training, as well as support from the Pain Champion, also contributed to staff members’ uptake and implementation.

Another theme that emerged was the app’s ability to provide useful contextual information such as the circumstances surrounding an assessment (i.e. observed activity, time of day) as well as which staff member conducted the assessment. This reportedly provided participants with a broader perspective of residents’ pain over time and the circumstances surrounding it. Feedback from the app resident pain graphs was also positive as 28% of participants, reported that it allowed for easy interpretation of the PACSLAC-II assessments, tracking of resident’s pain over time, evaluation of the effectiveness of treatment interventions, and communication with other health professionals (i.e. sending the graph to physicians).

Another perceived benefit of utilizing the PACSLAC-II app was that it helped prioritize pain in their units. Staff members in one unit reported that the assessment tool being presented in an electronic format, eliminated instances where assessments were not fully completed. For example, with paper assessments, sometimes some information may not be filled in due forgetting to follow up or other competing tasks requiring the staff’s attention. However, with the app, specific prompts such as “Please indicate the activity” eliminated these instances. Follow-up was also more immediate as a prompt would appear asking for a nurse to review the assessment results. Therefore, nurses were able to follow up and introduce interventions within a more appropriate timeframe rather than the long delays between initial pain identification and appropriate pain management.

Data security (mentioned by 22% of participants) was a theme that emerged during the interview as a potential benefit of using the app. Participants explained that often with pen-and-paper systems, data might become lost or misplaced, or the information may be changed without the staff member’s knowledge. Therefore, by having the pain assessments stored electronically, and with the name of the staff member who completed the assessment automatically collected, staff believed that the data was more secure, and were able to more easily follow up with the original assessor if they required information. Moreover, 74% of participants reported that the app had minimal or no impact on their workload suggesting the feasibility of the app in assisting pain assessment and pain management. For these reasons, 87% of participants reported an overall positive experience using the app and 74% reported a preference for the app over the paper version of the PACSLAC-II.

Barriers towards PACSLAC-II app and suggestions for improvement

Supplementary Online Appendix B includes representative quotes for each theme. Although most participants felt positively about the app, some themes reflected barriers to using the app including limited technological infrastructure (e.g. inadequate Wi-Fi signal), incongruence with the unit’s current paper health records system, and discomfort with technology or difficulties adjusting to change.

Another example of limited technological infrastructure is staff members not having assigned email addresses from their employer. As such, staff in one unit expressed that the app could only take them so far as they could not print off the resident graphs. However, many participants, particularly managers and care coordinators, mentioned that although the app was not compatible with their current system, they still found the app to be helpful and user-friendly and would consider implementing it in their units again if their units shifted to electronic record keeping.

Regarding incongruence with the unit’s current health record system a participant stated, “the way of nursing is pen and paper”. Although there has been a gradual shift to move to electronic charting, many LTC units still heavily relied on paper charting for their daily progress notes. Therefore, the app was often the only tool that was not paper-based. As many participants do not use technology as part of their daily activities at work, some expressed hesitancy or discomfort with technology. Others experienced a learning curve or relied more heavily on their Pain Champion. However, by the end of the study, there was an overall impression that participants were able to comfortably use the app without support. With regards to areas for improvement, many staff members reported that they enjoyed the app and believed that no improvement was needed. Limited suggestions were brought forward, but the most common included simplifying the log-in process for staff members and creating the ability to view pain scores of residents at the unit level rather than just at the resident level to assist in follow-up.

Quality indicator and community portal websites

For the units that were assigned to the QI website, it was clear that although the researchers and Pain Champions encouraged the use of the website, many staff members did not regularly use the website (83%). Reasons for not using the website included lack of time during their shift or perceived lack of applicability to their daily role assessments. For example, some care aides and nurses reported that the website might be more helpful for their care coordinator or manager. Of the few staff members who used the website, 80% perceived the website to be easy to use and had limited suggestions for improvement. Similar results were obtained for the CP website. Although not many individuals regularly used the website due to limited time (82%), the staff that did look at the website described the resources as useful (70%) and the website as easy to use (60%). All staff members who used the website were passive participants of the website (i.e. looking at resources) rather than active participants (i.e. commenting, sharing new resources). No suggestions for improvement were identified during the interviews (see Supplementary Online Appendix B).

Perceived barriers to study implementation

A theme that was revealed from the interview data was participants’ perceived barriers to the assessment protocol implementation. The barriers that were the most highly reported included the increased frequency of pain assessments as required by the protocol (22%) and inadequate staffing resources (22%). Although individual pain assessments typically took less than five minutes to complete, there was a significant increase in the number of pain assessments that were completed weekly compared to a unit’s standard practice assessments. Insufficient staffing was another reported difficulty due to a combination of reasons such as units being short-staffed, high resident-to-staff ratios, or staff vacations. Staff vacations were especially difficult to navigate when Pain Champions were away for an extended period and were unable to facilitate the study protocol. Lastly, 9% of participants acknowledged that the timing of the study was also another barrier, as they experienced an increased workload associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e. infection control measures and vaccinations). Hence, units were unable to dedicate adequate added resources to the study. See Supplementary Online Appendix B for other representative quotes.

Discussion

This study replicated and extended key findings from Zahid et al. (Citation2020) and is the first to examine the impact of an app-based community platform and a validated pain assessment app on LTC-facility-wide quality indicators (e.g. % of residents assessed for pain at least once a week) and questionnaire-assessed LTC staff stress and burnout. Staff were also interviewed about their experience using the app and associated community platform. In contrast to the practices of many unregulated app developers (Portelli & Eldred, Citation2016), the PACSLAC-II app has undergone systematic evaluations in LTC, providing support for the efficacy of mHealth technology in such settings. Specifically, this study provides further support for the utilization of the app (Zahid et al., Citation2020) to improve QIs for resident pain in LTC facilities (Hadjistavropoulos et al., Citation2009; Citation2016).

One strength of the study is that its multiple-baseline between-facilities design allowed for the evaluation of differences not only between conditions but also within the same unit without the need for treatment withdrawal as new resources are introduced. Across all conditions, QI scores were elevated up to 100% after the introduction of the PACSLAC-II app where the average baseline scores were between approximately 0–5%. We did note that for 4 of the 11 participating units (i.e. Units C, G, J, and K), the percentage of residents assessed for pain at least once a week dropped during the last active phase of the study (although, even in the last active phase of the study, this percentage remained considerably higher than the initial baseline). We know that at least 3 of these 4 units experienced considerable staffing challenges which were compounded by vacation schedules and the COVID-19 pandemic. We believe that the drops over time in these specific units were due primarily to these staffing challenges that interfered with ability to conduct assessments as the study progressed.

The multiple baseline design is rigorous as improvements in QI are observed multiple times, for different units, and at different points in time. This strengthens both the internal and external validity of the effectiveness of the intervention of the PACSLAC-II app (Levin & Ferron, Citation2021).

It was hypothesized that according to the job demands-resources (JD-R) model, the PACSLAC-II app and its associated websites would presumably act as job resources for the healthcare professionals and would facilitate coping with job demands and resident assessments. Therefore, it was anticipated that use of the app as well as both of its complementary features would be associated with the most gains. Based on the units’ QI scores, however, the community features did not appear to have added much to the use of the app. This is likely due to the low usage of these resource websites. According to the JD-R model, it is possible that staff did not readily use these websites if they did not find the websites helpful in reducing job demands or in achieving work goals (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007). For example, increased job demands associated with COVID-19 may be much higher than what these job resources may be capable of buffering. As such, given the added stresses of the pandemic, burnout scores would not have been managed adequately by peripheral resources (e.g. the CP). Nonetheless, when focusing specifically on the PACSLAC-II app, 87% of the healthcare professionals had a positive experience with the app due to several reasons such as perceived usefulness, convenience, clinical feasibility, and helpful information that it provides (i.e. resident graphs, contextual information). These experiences were especially true for healthcare professionals with access to established technological infrastructure. Hence, it can be assumed due to the high proportion of app versus website utilization that the increases in observed QI scores were due to the app itself rather than the websites, which speaks to the clinical utility of the app in assisting healthcare professionals to improve their pain assessment practices.

Limitations and future directions

In this study, we used an applied behavior analysis approach to evaluate QI changes in 11 units. This work can be extended through large-scale investigations employing large numbers of LTC facilities which could allow for statistical analysis at the resident level and accounting for the nesting of residents within units.

One of the challenges associated with this study was the timing of the research in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic and frequent outbreaks which created tremendous competing demands for staff. These concerns were identified most often by nurses, managers, and resident care coordinators rather than care aides. Nurses described that the high resident-to-nurse ratio, increased frequency of assessments, and lack of available nursing staff posed challenges to the successful completion of pain assessments and appropriate follow-up. These factors may have contributed to elevated burnout and fewer healthcare professionals using the CP and QI websites. Inadequate technological infrastructure may have negatively impacted the facilitating conditions needed for the study. Competing tasks may have contributed to lower QI scores at follow-up, as the frequency of pain assessments was not maintained once the encouragement and support of our research team ceased. Previous research (Hadjistavropoulos et al., Citation2016) conducted prior to the pandemic demonstrated that similar gains in QI were sustained during the follow-up period. These results support this interpretation that the pandemic contributed to the decreased scores of QIs during the follow-up period.

As the PACSLAC-II has already been translated and validated in several different languages such as French (Poulin et al., Citation2021), Korean (Kim et al., Citation2014), and Turkish (Büyükturan et al., Citation2018), creating different language versions of the app is the natural next step. Simple suggestions participants brought forward during the interviews such as improved log-in processes are being currently addressed for the next update. Lastly, with regards to the QI website and CP website, although the care aides and nurses found the information interesting, it was reportedly not as applicable to their role of assessment and pain management at the resident level. Therefore, these websites may be more geared toward managers and directors, as indicated by participants, as their roles may be more focused on improving the quality of care at a broader level.

Nonetheless, given that some participants reported a lack of applicability of the QI website to their daily role assessments, it would be fruitful for future research to explore the needs of health professionals and redevelop these websites with them involved at the design stage (i.e. co-design).

Based on the results of this study, the following recommendations may improve the implementation of the PACSLAC-II app or other mHealth apps in LTC settings. Facilities with an established infrastructure for technology, such as stable Wi-Fi and electronic health record systems, may find the app more beneficial, as they may need less adjustment to technology and experience fewer technical difficulties. In contrast, absence of adequate technological infrastructure has been noted as a barrier to implementation in previous related research (Or et al., Citation2014) as well as in models of health information technology applications in complex health care systems (Pelayo & Ong, Citation2015; Sittig & Singh, Citation2010). As such, for facilities that have limited technological infrastructure, focus groups to determine ways in which the app can be better introduced and integrated into their units may be beneficial before the app is implemented (Kaasalainen et al., Citation2010). Lastly, the incorporation of Pain Champions is essential as they help to oversee and facilitate the implementation of the app and provide additional support to staff members.

Conclusions

Although the pandemic brought about logistical challenges, it also provided a unique opportunity to assess the clinical utility of the app in a setting where workload and competing demands were even more prominent than usual. Even during these challenging times, the updated version of the PACSLAC-II app demonstrated positive effects in the care of residents and was positively received by healthcare professionals working in LTC settings. The pandemic has also highlighted the systematic gaps in the funding and care provided to residents in LTC. With the growth of our aging population and expected development of mHealth, it is essential that high-quality apps, such as the PACSLAC-II app, which are informed and validated by research, be available for residents and professionals in LTC settings. The PACSLAC-II app and its novel CP represent a positive direction toward continued innovation and technological advancements in LTC.

Statement of ethical approval

This research has been approved by the University of Regina Research Ethics Board (#2020-210)

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.8 KB)Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part from funding from the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation and the AGE WELL Network of Centres of Excellence. We are grateful to the participating long-term care units for their support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ashton-James, C. E., McNeilage, A. G., Avery, N. S., Robson, L. H. E., & Costa, D. (2021). Prevalence and predictors of burnout symptoms in multidisciplinary pain clinics: A mixed-methods study. Pain, 162(2), 503–513. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002042

- Atee, M., Morris, T., Macfarlane, S., & Cunningham, C. (2021). Pain in dementia: Prevalence and association with neuropsychiatric behaviors. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 61(6), 1215–1226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.10.011

- Bakker, A. B., & de Vries, J. D. (2021). Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 34(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1797695

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands–Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 9(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000196

- Büyükturan, Ö., Büyükturan, B., Yetiş, A., Naharcı, M. İ., & Kırdı, N. (2018). Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate (PACSLAC-T). Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences, 48(4), 805–810. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-1801-120

- Chan, S., Hadjistavropoulos, T., Williams, J., & Lints-Martindale, A. (2014). Evidence-based development and initial validation of the pain assessment checklist for seniors with limited ability to communicate-II (PACSLAC-II). The Clinical Journal of Pain, 30(9), 816–824. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000039

- Costello, H., Walsh, S., Cooper, C., & Livingston, G. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and associations of stress and burnout among staff in long-term care facilities for people with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 31(8), 1203–1216. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610218001606

- Ford, J. R., Korjonen, H., Keswani, A., & Hughes, E. (2015). Virtual communities of practice: Can they support the prevention agenda in public health? Online Journal of Public Health Informatics, 7(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5210/ojphi.v7i2.6031

- Fuchs-Lacelle, S., Hadjistavropoulos, T., & Lix, L. (2008). Pain assessment as intervention: A study of older adults with severe dementia. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 24(8), 697–707. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e318172625a

- Gallant, N., Hadjistavropoulos, T., Winters, E. M., Feere, E. K., & Wickson-Griffiths, A. (2022). Development, evaluation, and implementation of an online pain assessment training program for staff in rural long-term care facilities: A case series approach. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 336. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03020-8

- Hadjistavropoulos, T., Browne, M. E., Prkachin, K. M., Taati, B., Ashraf, A., & Mihailidis, A. (2018). Pain in severe dementia: A comparison of a fine-grained assessment approach to an observational checklist designed for clinical settings. European Journal of Pain (London, England), 22(5), 915–925. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1177

- Hadjistavropoulos, T., Hunter, P., & Dever Fitzgerald, T. (2009). Pain assessment and management in older adults: Conceptual issues and clinical challenges. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 50(4), 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015341

- Hadjistavropoulos, T., Marchildon, G. P., Fine, P. G., Herr, K., Palley, H. A., Kaasalainen, S., & Béland, F. (2009). Transforming long-term care pain management in North America: The policy-clinical interface. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.), 10(3), 506–520. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00566.x

- Hadjistavropoulos, T., Williams, J., Kaasalainen, S., Hunter, P. V., Savoie, M. L., & Wickson-Griffiths, A. (2016). Increasing the frequency and timeliness of pain assessment and management in long-term care: Knowledge transfer and sustained implementation. Pain Research & Management, 2016, e6493463. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6493463

- Jonsdottir, T., & Gunnarsson, E. C. (2021). Understanding Nurses’ Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Pain Assessment in Dementia: A Literature Review. Pain Management Nursing: Official Journal of the American Society of Pain Management Nurses, 22(3), 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2020.11.002

- Kaasalainen, S., Wickson-Griffiths, A., Akhtar-Danesh, N., Brazil, K., Donald, F., Martin-Misener, R., DiCenso, A., Hadjistavropoulos, T., & Dolovich, L. (2016). The effectiveness of a nurse practitioner-led pain management team in long-term care: A mixed methods study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 62, 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.07.022

- Kaasalainen, S., Williams, J., Hadjistavropoulos, T., Thorpe, L., Whiting, S., Neville, S., & Tremeer, J. (2010). Creating bridges between researchers and long-term care homes to promote quality of life for residents. Qualitative Health Research, 20(12), 1689–1704. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732310377456

- Kao, Y.-H., Hsu, C.-C., & Yang, Y.-H. (2022). A nationwide survey of dementia prevalence in long-term care facilities in Taiwan. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(6), 1554. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11061554

- Kazdin, A. E. (2021). Single-case experimental designs: Characteristics, changes, and challenges. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 115(1), 56–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.638

- Kim, E.-K., Kim, S. Y., Eom, M. R., Kim, H. S., & Lee, E. (2014). Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the pain assessment checklist for seniors with limited ability to communicate. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 44(4), 398–406. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2014.44.4.398

- Lalloo, C., Shah, U., Birnie, K. A., Davies-Chalmers, C., Rivera, J., Stinson, J., & Campbell, F. (2017). Commercially available smartphone apps to support postoperative pain self-management: Scoping review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 5(10), e8230. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.8230

- Lam, C. L. K., Tse, E. T. Y., Wong, C. K. H., Lam, J. S. M., Chen, S. S., Bedford, L. E., Cheung, J. P. Y., Or, C. K., & Kind, P. (2021). A pilot study on the validity and psychometric properties of the electronic EQ-5D-5L in routine clinical practice. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 19(1), 266. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01898-3

- Levin, J. R., & Ferron, J. M. (2021). Different randomized multiple-baseline models for different situations: A practical guide for single-case intervention researchers. Journal of School Psychology, 86, 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2021.03.003

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

- Ng, A. P. P., Liu, K. S. N., Cheng, W. H. G., Wong, C. K. H., Cheng, J. K. Y., Lam, J. S. M., Or, C. K., Tse, E. T. Y., & Lam, C. L. K. (2022). Feasibility and acceptability of electronic EQ-5D-5L for routine measurement of HRQOL in patients with chronic musculoskeletal problems in Hong Kong primary care. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 20(1), 137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-022-02047-0

- O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 160940691989922. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

- Or, C., Dohan, M., & Tan, J. (2014). Understanding critical barriers to implementing a clinical information system in a nursing home through the lens of a socio-technical perspective. Journal of Medical Systems, 38(9), 99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-014-0099-9

- Pelayo, S., & Ong, M. (2015). Human factors and ergonomics in the design of health information technology: Trends and progress in 2014. Yearbook of Medical Informatics, 10(1), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.15265/IY-2015-033

- Portelli, P., & Eldred, C. (2016). A quality review of smartphone applications for the management of pain. British Journal of Pain, 10(3), 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463716638700

- Poulin, A., Verreault, R., Aubin, M., Desbiens, J. F., Hadjistavropoulos, T., Savoie, M., & Lafond, M. F. (2021). Une version abrégée de l’échelle PACSLAC. Les déficits cognitifs et l’évaluation de la douleur en CHSLD. Perspective Infirmière, 18(1), 47–52.

- Shaw, L., Jazayeri, D., Kiegaldie, D., & Morris, M. E. (2022). Implementation of virtual communities of practice in healthcare to improve capability and capacity: A 10-year scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 7994. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137994

- Shoman, Y., Marca, S. C., Bianchi, R., Godderis, L., van der Molen, H. F., & Guseva Canu, I. (2021). Psychometric properties of burnout measures: A systematic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 30, e8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020001134

- Sittig, D. F., & Singh, H. (2010). A new socio-technical model for studying health information technology in complex adaptive healthcare systems. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 19(Suppl 3), i68–i74. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2010.042085

- Spallek, H., Butler, B. S., Schleyer, T. K., Weiss, P. M., Wang, X., Thyvalikakath, T. P., Hatala, C. L., & Naderi, R. A. (2008). Supporting emerging disciplines with e-communities: Needs and benefits. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 10(2), e19. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.971

- Thomas, K. S., Zhang, W., Cornell, P. Y., Smith, L., Kaskie, B., & Carder, P. C. (2020). State variability in the prevalence and healthcare utilization of assisted living residents with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(7), 1504–1511. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16410

- Zahid, M., Gallant, N. L., Hadjistavropoulos, T., & Stroulia, E. (2020). Behavioral pain assessment implementation in long-term care using a tablet app: Case series and quasi-experimental design. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(4), e17108. https://doi.org/10.2196/17108