Abstract

Objectives: Feeling safe in the daily environment is important in late life. However, research on configuration of vulnerability factors for perceived unsafety in older adults is scarce. The current study aimed to identify latent subgroups of older adults based on their vulnerability for perceived unsafety.Method: We analyzed the data from a cross-sectional survey of residents in senior apartments in a mid-sized Swedish municipality (N = 622).Results: The results of the latent profile analysis based on frailty, fear of falling, social support, perceived neighborhood problems, and trust in others in the neighborhood indicated the presence of three profiles. These profiles were labelled as compromised body and social networks (7.2%), compromised context (17.9%) and non-vulnerable (74.9%). Profile membership was statistically predicted by age, gender, and family status and profiles differed in perceived unsafety, anxiety and life satisfaction.Conclusion: Overall, the study findings suggested the existence of latent subgroups of older people based on patterns of vulnerability.

SUBJECT CLASSIFICATION CODES:

Introduction

Perceiving one’s daily environment as safe is crucial for quality of life in advanced age. Living in safe environments is essential for aging well according to World Health Organization’s (WHO) active ageing paradigm (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2002). Lack of perceived safety is related to reduced health and well-being of older adults (Won et al., Citation2016) and challenges the opportunity for ageing in place (Fonseca, Citation2020). Recent research showed that multiple personal and environmental factors contributed to perceived unsafety among older adults. Among such factors were diminished health, lack of social support, and perceived neighborhood characteristics (De Donder et al., Citation2012; Olofsson et al., Citation2012; Velasquez et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2022). The diversity of these factors might indicate potential differences in the vulnerability factors that predispose older adults to feeling unsafe. Although previous studies indicated that feelings of unsafety could be a manifestation of a range of insecurities (Hale, Citation1996), there has been limited research addressing the potential diversity of factors of vulnerability among older adults simultaneously. Therefore, gaining a better understanding of such vulnerability factors potentially predisposing older adults to feeling unsafe is important for further explaining perceived unsafety in advanced age.

Theoretically, the presence of multiple underlying vulnerability factors could be explained by the Generalized Unsafety Theory of Stress (GUTS; Brosschot et al., Citation2017, Citation2018). This theory posits that unsafety is experienced when safety signals are lacking and is not necessarily evoked by a specific threatening stimulus. Rather, such generalized perceived unsafety results from chronic compromises in important life domains, namely, health and functioning (compromised bodies), social engagement (compromised social network), and overall environment (compromised contexts) (Brosschot et al., Citation2017, Citation2018). Consequently, deficits in any of these life domains indicate vulnerability for perceived unsafety.

Considering older adults, GUTS predicts greater perceived unsafety in late life due to functional changes (e.g. increasing reaction time) and health problems related to ageing (Brosschot et al., Citation2018). However, the theory does not articulate potential differences among older adults in relation to their vulnerability for perceived unsafety. Gerontological research suggests significant heterogeneity of late life in terms of health, lifestyles, social relationships, living conditions, coping with challenges of ageing and other life aspects crucial to understanding perceived unsafety (Diehl & Wahl, Citation2020; Márquez González et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, research on multiple factors of underlying vulnerability for perceived unsafety, their possible configurations, and associations with aspects of perceived unsafety and well-being is very limited. The current study addressed this research gap by applying a person-oriented approach to studying possible vulnerability profiles and their associations with socio-demographic factors, perceived unsafety in the neighborhood and at home, fear of crime, anxiety and life satisfaction.

The person-oriented approach follows the holistic view on an individual and aims to identify patterns of characteristics within an individual and to classify individuals into subgroups based on these patterns (Asendorpf, Citation2002; Bergman et al., Citation2003). When applied to studying perceived unsafety, person-oriented research aims to identify the profiles of vulnerability reflecting the configuration of indicators of physical, psychosocial and environmental vulnerability. Specifically, latent profile analysis (LPA) as a data-driven, person-oriented method allows the identification of the number of existing profiles, the prediction of belongingness to a profile and the estimation of the associations between the profiles and relevant study variables (Ferguson et al., Citation2020).

Indicator variables

In LPA, the latent profiles are identified based on preselected indicator variables (Wang & Wang, Citation2020). For the current study, the selection of indicator variables was theoretically guided by the GUTS (Brosschot et al., Citation2017, Citation2018), as well as environmental gerontology perspective (Wahl & Gitlin, Citation2019) and the social capital theory (De Donder et al., Citation2012). Specifically, variables corresponding to potentially compromised life domains that were relevant in the ageing context were selected for the analysis. These indicator variables represent various factors of vulnerability which are a potential source of perceived unsafety.Footnote1

First, frailty and fear of falling corresponded to the compromised body domain. Frailty encompasses a multidimensional decline in health including physical, psychosocial, and daily functioning aspects, specific for advanced age (Clegg et al., Citation2013; Schuurmans et al., Citation2004). Fear of falling is a highly prevalent age-specific health problem associated with poor subjective health and reduced quality of life (Lenze & Wetherell, Citation2011; Zijlstra et al., Citation2007).

Second, lack of perceived social support corresponded to the compromised social networks domain. Previous research highlighted the importance of social capital in preventing feelings of unsafety in late life (De Donder et al., Citation2012; Kang & Seo, Citation2020). In the current study, we explored social support as a form of individual social capital (Mathis et al., Citation2015) and differentiated between social support from the significant other, friends, and family (Zimet et al., Citation1988). Differentiating between sources of social support is important since previous research indicated that older adults’ social relations with friends but not close relatives were associated with reduced feelings of unsafety (De Donder et al., Citation2012).

Third, experiencing problems in the neighborhood and lack of trust in others living in the neighborhood corresponded to the compromised context domain, because it was previously shown that perception of the neighborhood in its physical and social aspects is important for older adults’ perceived safety (Fonseca, Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2022). In line with the propositions of environmental gerontology, the quality of both physical and social environments is important for the perceived safety and well-being of older adults (Oswald et al., Citation2011; Wahl & Gitlin, Citation2019). Therefore, as neighborhood can be considered the immediate environment of older people, physical and social neighborhood aspects were chosen to reflect the compromised context domain.

Covariate variables

Several socio-demographic factors have been shown to be related to perceived unsafety (Henson & Reyns, Citation2015; Killias & Clerici, Citation2000; Rader et al., Citation2012). Specifically, being female, older in age, having a lower level of education and socio-economic status, and living alone was shown to contribute to perceived unsafety (Henson & Reyns, Citation2015). Additionally, an association between previous victimization of older adults and perceived unsafety was reported (Olofsson et al., Citation2012). Therefore, age, gender, education, family status, financial situation and previous victimization were selected as covariate variables.Footnote2

Outcome variables

Perceived unsafety as well as anxiety and life satisfaction were outcome variables in this study, all reflecting negative aspects of well-being. Because of previously reported differences between perceived unsafety in the neighborhood and at home (Allik & Kearns, Citation2017), as well as between feeling unsafe and being fearful of crime (Golovchanova et al., Citation2022), these aspects of unsafety (i.e. perceived unsafety in neighborhood and at home, and fear of crime) were explored as separate outcome variables. Anxiety and life satisfaction were included in order to understand the vulnerability for perceived unsafety in its relation to overall mental health and well-being aspects as important healthy ageing outcomes (Fernandez-Ballesteros, Citation2019). While unsafety, anxiety and life satisfaction are known to be interrelated (Adams & Serpe, Citation2000; Kuin & Spaans, Citation2017; Stafford et al., Citation2007), less is known about the associations between factors of underlying vulnerability for feeling unsafe and anxiety and life satisfaction, respectively. As stated by the GUTS, perceived unsafety is closely linked to the anxiety (stress) response (Brosschot et al., Citation2018). A positive association of perceived unsafety with anxiety is well established (Hollway & Jefferson, Citation2000; McKee & Milner, Citation2000; Olofsson et al., Citation2012; Stafford et al., Citation2007). Aspects of perceived unsafety were also shown to have a negative association with life satisfaction (Adams & Serpe, Citation2000; Hanslmaier, Citation2013). Thus, including different aspects of unsafety and anxiety as well as life satisfaction as outcomes provided the opportunity to study possible differences in the contribution of various constellations of vulnerability factors related to these outcomes.

The current study

Overall, the current study aimed to identify profiles of vulnerability for feeling unsafe among older adults and to explore associations of these profiles with socio-demographic factors, perceived unsafety in the neighborhood and at home, fear of crime, anxiety, and life satisfaction. Specifically, the study addressed the following research questions: (1) Which profiles of vulnerability can be identified based on variables corresponding to potentially compromised life domains? (2) Are socio-demographic factors associated with profile membership? (3) Do the profiles differ on perceived unsafety aspects, anxiety and life satisfaction?

Method

Sample and procedure

The current study is based on the 65+ and Safe Study data, a postal and web survey performed in 2019 in a mid-sized municipality in Sweden (approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Agency, dnr: 2019-02248). This cross-sectional study aimed to improve understanding of perceived safety and fear of crime among residents of senior apartments. The inclusion criteria for the study were being 65 years in the year of data collection or older, residing in a municipal senior apartment, and absence of severe cognitive impairment. A total of 622 responses were available in the 65+ and Safe Study data (49.5% response rate). Comparison of the responders and non-responders showed that those who responded to the questionnaire did not significantly differ from non-responders in terms of gender, but were on average younger (M = 77.6, SD = 7.22) compared to non-responders (M = 79.09, SD = 8.12) (for a detailed description of data collection, see Golovchanova et al. (Citation2022) . Further, one participant had missing data on all variables of interest in the current study and was therefore excluded from the analysis. Thus, the analytic sample for the current study included 621 participants ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants and descriptive statistics.

Instruments

Indicator variables

Frailty was measured with the Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI; Steverink et al., Citation2001). This instrument is multidimensional and includes 15 items tapping into physical, cognitive, social and psychosocial aspects of frailty. Responses on individual items were assigned scores according to the recommended scale scoring (Schuurmans et al., Citation2004). The mean scale score was computed based on at least nine valid answers. The instrument demonstrated good reliability in our sample (Kuder-Richardson (KR) 20 = .70).

Fear of falling was assessed with a single item asking the respondents to rate how afraid they feel to experience a fall accident, with response alternatives ranging from 0 (‘Not afraid at all’) to 10 (‘Very much afraid’).

Social support was measured by means of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al., Citation1988). Twelve items included in the instrument form three subscales assessing perceived social support from the significant other, family and friends. Each subscale contains four items, for example ‘I have a special person who is a real source of comfort to me’ (Social support from significant other), ‘I get the emotional support and help I need from my family’ (Social support from family) and ‘I can count on my friends when thing go wrong’ (Social support from friends). Study respondents scored each item on a 7-point Likert scale from ‘Very strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘Very strongly agree’ (7). In the current study, the Significant other, the Family and the Friends subscales were used as separate variables. The subscale scores were computed by calculating the means based on at least three valid answers for each subscale. Each subscale showed very good reliability with Cronbach’s alpha being 0.92 (Significant other), 0.93 (Family) and 0.93 (Friends).

Neighborhood problems were assessed by rating the presence of six potential problematic characteristics of neighborhoods. The respondents were asked to rate to what extent the following is a problem in the area where they live: (a) Litter; (b) Vandalism; (c) Graffiti; (d) Reckless driving with motorbike or with other vehicles; (e) Individuals or gangs who cause trouble or disturbances; (f) Open drug trafficking. Response options for rating each of these six problems varied from ‘Not at all’ (1) to ‘To a great extent’ (4). The neighborhood problems index was calculated by computing the mean score based on valid responses on at least four items. The index showed very good reliability in our sample (Cronbach’s alpha 0.91).

Trust in other people in the neighborhood was assessed by a single item ‘How much do you trust people in your neighborhood?’. Response options varied from ‘Not at all’ (1) to ‘To a great extent’ (4).

Covariate variables

Socio-demographic variables. Age was assessed as a continuous variable, and gender was coded dichotomously as ‘0’ = Male and ‘1’ = Female. Responses on the level of education were dichotomized into ‘1’ = High school degree or lower; and ‘2’ = Education above high school. Family status was coded as ‘1’—with partner (married, living together or separately with a partner), and ‘2’—without partner (single, divorced or widowed). Current financial situation was assessed with a question on whether the responder would be able to get a hold of 15,000 SEK in 1 week in case of necessity. To assess previous victimization, we inquired whether the responder had been a victim of crime in the past year.

Outcome variables

Perceived unsafety in the neighborhood and at home was assessed with two single items: ‘During the last year, did you ever feel unsafe in the area where you live?’ and ‘During the last year, did you ever feel unsafe in the apartment in which you live?’. Both items were rated on a scale from ‘Never’ (1) to 5 ‘Very often’ (5). These items were treated as separate outcome variables.

Fear of crime (affective aspect) was assessed with a six-item index in which each item represented worry about a specific type of crime (e.g. ‘Has it happened in the past year that you have been worried that you will be attacked or assaulted’?). The types of crime included break-in (burglary); attack or assault; robbery; rape or sexual assault; crime committed by individuals having access to the respondent’s apartment (e.g. those delivering service or assistance at home); and worry that a close person might become victimized. Each item was rated with response options ranging from ‘Never’ (1) to ‘Very often’ (5). The index showed very good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80). The index variable was computed using a mean score of at least four valid responses.

Anxiety was assessed with the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A) (Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983). The subscale consists of seven items each rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 to 3 (e.g. ‘Worrying thoughts go through my mind’; ‘I get sudden feelings of panic’). The Anxiety scale was computed using the mean score of at least five of the total seven items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85).

Life satisfaction was measured with The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., Citation1985). This instrument includes five items which are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, from ‘Strongly disagree’ to ‘Strongly agree’ (e.g. ‘In most ways my life is close to my ideal’, ‘So far I have gotten the important things I want in life’). The scale showed very good reliability in our sample (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88). The scale variable was computed using the mean score of at least three valid responses.

Analytic strategy

As the first step, we performed the LPA to determine the model with the number of profiles that best fitted the data. LPA is a person-oriented analysis which aims to identify latent groups (profiles) of individuals by examining the distribution of means of several continuous indicator variables (Ferguson et al., Citation2020; Wang & Wang, Citation2020). In the current study, we used the following seven indicator variables to estimate the latent profiles: frailty; fear of falling; social support from the significant other, social support from family; social support from friends; neighborhood problems and trust in others in the neighborhood. Models including from one to five latent profiles were considered, and each following model was assessed for model fit in comparison to the previous model. The model fit was assessed by means of Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Sample-Adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (sBIC), the log-likelihood values with lower levels indicating better model fit and the Lo, Mendell, and Rubin (LMR) test with significant test results indicating preference for the model with more profiles (Ferguson et al., Citation2020). We considered the smallest class size with profiles including more than 5% of the sample and more than 30 individuals as sufficient (Ferguson et al., Citation2020). Moreover, we considered the theoretical interpretability of the profiles when selecting the best fitting model. Entropy was examined after determining the model with the best fit. Values above 0.80 were considered indicative of the model assigning individuals into profiles well (Ferguson et al., Citation2020). The assumption of local independence was assessed by calculating the percentage of significant covariances within profiles for each model (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2015).

In the second step, we performed a multinomial logistic regression with profile as the dependent variable and socio-demographic variables as predictors in order to estimate whether profile membership could be predicted by age, gender, education, family status, financial situation, and previous victimization. Our alpha cut-off of 0.05 was Bonferroni-corrected to p < 0.0028 (18 tests) to determine statistical significance in this step.

In the third step, a series of Kruskall-Wallis H-tests was applied to examine the differences among the profiles in perceived unsafety in the neighborhood and at home, fear of crime, life satisfaction, and anxiety. We opted for a non-parametric statistical test because perceived unsafety in the neighborhood, perceived unsafety at home, fear of crime, and anxiety were significantly skewed. We used a Bonferroni-corrected alpha cut-off of p < 0.003 (15 tests) to determine statistical significance.

Steps one and two of the analyses were performed in Mplus Version 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–Citation2017), and step three was performed in IBM SPSS 27.

Results

Which profiles of vulnerability can be identified?

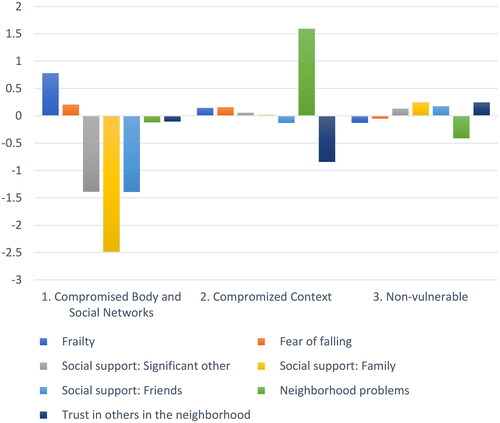

The model with the number of profiles that best fitted the data was determined based on the model fit statistics (). Models with one to five profiles were estimated. For the model with five profiles, the maximum likelihood was not successfully replicated and therefore this model was not considered as fitting the data. We inspected the model fit indicators for the four models including one to four profiles. The log-likelihood, AIC and sBIC values decreased with each additional profile, and the smallest class size was sufficient for all the models. The LMR test for the model with four profiles was not significant indicating that the model with three profiles fitted the data better. Interpretability of the three-profile model was considered as good and theoretically meaningful, while adding the fourth profile did not improve interpretability of the model. Hence the three-profile model was selected as optimal. shows the z-scores on each item for the three profiles.

Table 2. Summary of model fit statistics for models with one to four classes.

In line with the terminology of the Generalized Unsafety Theory of Stress (Brosschot et al., Citation2018), we labelled the profiles as (1) Compromised body and social networks (n = 45, 7.2%). This profile was characterized by highest frailty and fear of falling and lowest social support relative to the other profiles; (2) Compromised context (n = 111, 17.9%). This profile was characterized by highest experience of neighborhood problems and lowest trust in others in the neighborhood relative to the other profiles and (3) Non-vulnerable (n = 465, 74.9%). This profile was characterized by lowest frailty and fear of falling, highest social support, lowest experience of neighborhood problems, and highest trust in others in the neighborhood relative to the other profiles.

Are socio-demographic factors associated with profile membership?

A multinomial logistic regression model with profile as dependent variable and age, gender, education, family status, financial situation and victimization as predictors was estimated to examine whether socio-demographic factors predicted profile membership (). The results indicated that men were significantly more likely to be classified in the Compromised body and social networks profile compared to both the Compromised context and Non-vulnerable profiles. Moreover, respondents without a partner were significantly more likely to be classified in the Compromised body and social networks profile, whereas younger respondents were more likely to be included in the Compromised context profile compared to the Non-vulnerable profile.

Table 3. Multinomial logistic regression predicting profile membership.

Do the profiles differ on perceived unsafety aspects, anxiety and life satisfaction?

As the last step of the analysis, we assessed whether the three profiles differed significantly in terms of perceived unsafety, fear of crime, life satisfaction and anxiety (). Results of the Kruskall-Wallis H tests and post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that individuals belonging to the Compromised context profile reported significantly more frequent perceived unsafety in the neighborhood, at home, and fear of crime compared to the Non-vulnerable. Moreover, respondents in the Compromised context profile reported significantly more fear of crime compared to the Compromised body and social networks profile. Further, respondents in the Non-vulnerable profile reported significantly less anxiety compared to the Compromised context profile. Finally, all profiles differed significantly in their life satisfaction, with the highest life satisfaction experienced by those in the Non-vulnerable profile and the lowest in the Compromised body and social networks profile.

Table 4. Results of the Kruskall-Wallis H tests (post-hoc pairwise comparisons of differences between the profiles).

Discussion

Applying the GUTS as a guiding framework, the current study aimed to identify the profiles of vulnerability for perceived unsafety among older adults. The latent profile analysis determined the presence of three distinct profiles in our sample. Older adults in the Compromised body and social networks profile reported more health problems and deficits in social support compared to the other profiles. Although this was the smallest profile including just over 7% of the sample, it is important to identify this subgroup of older adults whose vulnerability lies mainly in their diminished health and lack of social support. Men and those without a partner were significantly more likely to belong to this profile which draws special attention to these groups of older adults.

Interestingly, older adults in this compromised profile did not feel significantly more unsafe compared to the Non-vulnerable group. Respondents in this profile also worried less about crime compared to the Compromised context profile. Thus, we can clearly distinguish older people in this profile from older adults experiencing significant problems in the neighborhood regarding their perceived unsafety. This finding might indicate that different patterns of vulnerability are differentially associated with perceived unsafety in older adults. However, the respondents in this profile appeared to be at most risk for reduced life satisfaction (compared to the other two profiles).

Older adults in the Compromised context profile reported relatively high neighborhood problems and low trust in other residents. This profile included almost 18% of the sample and respondents in this profile were on average younger compared to the Non-vulnerable profile. Previous research has shown that, with increasing age, older adults tend to spend more of their time indoors compared to younger older adults who are generally more active outside (Köber et al., Citation2022; Oswald et al., Citation2011). This might explain why relatively younger older adults might be more exposed to adverse neighborhood conditions.

Respondents in the Compromised context profile felt more unsafe according to all applied measures, compared to the Non-vulnerable profile, and worried more about crime compared to the Compromised body and social networks profile. This result highlights the importance of the neighborhood context for perceived safety of older adults, which is in line with previous research findings (Velasquez et al., Citation2021). Moreover, older adults in this profile reported higher anxiety and lower life satisfaction compared to the Non-vulnerable profile. However, their life satisfaction was higher compared to the Compromised body and social networks profile. This difference might point out the combination of health problems and social isolation as potentially more detrimental for life satisfaction in older adults compared to neighborhood level problems only.

Older adults in the Non-vulnerable profile which included almost 75% of the sample displayed relatively less deficits across the body, the social networks, and the environmental context domains. Women and older adults having a partner were more likely to be classified in this profile compared to the Compromised body and social networks profile, and respondents of higher age were more likely to be in this profile compared to the Compromised context profile. Interestingly, respondents in the Non-vulnerable profile felt significantly safer on all measures compared to Compromised context profile, but not compared to Compromised body and social networks profile. Moreover, older adults in this Non-vulnerable profile experienced significantly less anxiety compared to the Compromised context profile. This is in line with the reasoning of the GUTS which highlights the association between perceived unsafety and anxiety (stress response) (Brosschot et al., Citation2018). However, since only one compromised profile differed from the Non-vulnerable in terms of anxiety, more research is needed to understand the anxiety characteristics in different compromised profiles. The respondents in the Non-vulnerable profile also reported significantly higher life satisfaction compared to the other two profiles, which highlights the importance of well-being in the important life domains (body, social networks, and context) not only for experienced safety, but also for the overall satisfaction with life in advanced age.

Theoretical implications of the study include further understanding of GUTS propositions regarding perceived unsafety in older adults. The study findings indicated two distinct patterns of vulnerability which characterized the Compromised body and social networks and the Compromised context profiles. These two compromised profiles were differentially associated with fear of crime and life satisfaction. Therefore, further research might address further differences in compromised domains and their interrelation with perceived unsafety aspects and well-being outcomes in late life. Further, these findings are in line with the environmental gerontology perspective (Wahl & Gitlin, Citation2019) and social capital theory applied to perceived unsafety in advanced age (De Donder et al., Citation2012). Specifically, compromises in the physical and social environment (Compromised context profile) and compromises in the social capital of older people (Compromised body and social networks profile) appeared to be important for differentiating among the two compromised profiles in our study.

Moreover, since almost 75% of the sample were classified as non-vulnerable, considering older age as a predisposition for perceived unsafety, as suggested by GUTS, should be taken with caution. Our findings demonstrated that health-related, social, and environmental vulnerability for perceived unsafety was experienced by certain subgroups, but not by the majority of older adults. However, the study was performed in the Nordic welfare and cultural context which is generally characterized by lower feelings of unsafety in the population compared to other countries (Ejrnæs & Scherg, Citation2022; Visser et al., Citation2013). Regarding aging, Sweden has been described as being at the forefront of introducing policies and services for older adults (Davey et al., Citation2014). Therefore, further research might explore the distribution of older adults among the non-vulnerable and the compromised profiles in a variety of welfare and cultural contexts.

Practical implications of the study refer to the possibility to guide policy and practice interventions for promoting safety and well-being among older adults. Considering that feeling safe is important for ageing in place (Aung et al., Citation2022; Fonseca, Citation2020), differentiating between health, social, and environmental vulnerabilities that predispose older people for feeling unsafe is important for policy and practice interventions. Such differentiation enables the identification of those at increased risk for feeling unsafe due to specific combinations of vulnerability factors. Specifically, interventions for older people exposed to neighborhood problems might aim to improve neighborhood conditions and increase trust among residents, whereas interventions for older people with diminished health might target adapting indoor and outdoor infrastructure to their needs. Furthermore, interventions for those older people lacking social support and integration in social relationships might aim to help them (re)establish their social networks. It is important to consider that some older adults might experience a combination of compromises in their life domains (e.g. compromised body and social networks profile) which might require a set of targeted interventions. Such differentiation might be considered by policy makers in order to further improve intervention efforts for promoting safety and, consequently, the well-being of older people.

Strengths and limitations

The study addressed an important knowledge gap in understanding the configurations of vulnerability for perceived unsafety in advanced age. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies on perceived unsafety in advanced age that employed a person-oriented approach. Importantly, this allowed us to identify distinct subgroups of older adults and describe the differences among them. Moreover, the study applied a theoretical explanation of multiple factors of vulnerability for perceived unsafety which is relatively new in the field of research on unsafety. Furthermore, the sample comprised a broad age range (64 to 106 years) which allowed us to capture a wide range of older adults’ experiences. Finally, the specific measurements of perceived unsafety in the current study were chosen with careful consideration of their relevance for advanced age (e.g. we excluded inquiring about being in one’s neighborhood alone at night, and included reference to crimes potentially relevant for older people). Thus, overall, this study contributes to the existing literature on perceived unsafety in advanced age by highlighting the differences among older adults in their vulnerability for perceived unsafety.

The following limitations of the study should be mentioned. First, the study sample included older adults who were residents of municipality-owned senior apartments. These older adults could be considered a relatively homogeneous group in terms of their socio-economic status, and this could explain the fact that education level and financial situation were not associated with profile membership in our study. Therefore, the study results should be generalized to overall older adult population with caution. Second, the study questionnaire was introduced to prospective respondents as a study of experiences of unsafety and fear of crime, which could have primed the respondents regarding their feelings of unsafety in the context of criminal victimization. This may have prevented older adults from reflecting on unsafety in a non-criminal context (e.g. traffic related unsafety, financial unsafety, etc.). Third, only residents who could reply to the questionnaire in Swedish or English could participate in the study because the questionnaire was not available in other languages. Therefore, it is likely that older people with a foreign background were underrepresented in our sample. Considering that ethnic composition had been previously associated with perceived unsafety (Visser et al., Citation2013), the distribution of older people among the profiles shown in this study could have been different in a more ethnically diverse sample. For example, given that those belonging to an ethnic minority might be at increased risk for compromises in their social context (Brosschot et al., Citation2018), the non-vulnerable profile might have been less prevalent. This is important to consider in future research on perceived unsafety in multicultural societies.

Conclusion

The study findings revealed substantial heterogeneity in the patterns of underlying vulnerability for perceived unsafety among residents of the senior apartments in a Swedish municipality. These findings suggest that subgroups of older people may exist that are characterized by different patterns of the presence or absence of compromises in the life domains of health, social networks, and overall environmental context. The results made it evident that although the Compromised context profile reported highest perceived unsafety, those in the Compromised body and social networks profile reported the lowest life satisfaction. This is important to consider in the overall context of well-being among older adults. Yet, since almost three quarters of the participants were classified into the Non-vulnerable profile, the findings challenged the assumption that perceived unsafety is an inevitable attribute of later life. Rather, the study identified the important differences among older adults in their vulnerability for feeling unsafe.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Örebro bostäder AB (ÖBO) for their assistance with access to the target sample. This study was accomplished within the context of the Swedish National Graduate School on Ageing and Health.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data presented in this article are not readily available because of participant confidentiality. Requests to access the data should be directed to [email protected].

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In accordance with the GUTS theory reasoning, variables measuring perceived unsafety were not included among the indicator variables, but rather served as outcome variables in the study.

2 In the framework of LPA, covariates are used to explore the differences among latent classes by regressing the retained latent subgroups on selected covariate variables. Covariates are ‘considered antecedents and not outcomes’ in the LPA modelling (Ferguson et al., Citation2020, p. 461).

References

- Adams, R. E., & Serpe, R. T. (2000). Social integration, fear of crime, and life satisfaction. Sociological Perspectives, 43(4), 605–629. https://doi.org/10.2307/1389550

- Allik, M., & Kearns, A. (2017). “There goes the fear”: Feelings of safety at home and in the neighborhood: The role of personal, social, and service factors. Journal of Community Psychology, 45(4), 543–563. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21875

- Asendorpf, J. B. (2002). The puzzle of personality types. European Journal of Personality, 16(1_suppl), S1–S5. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.446

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2015). Residual associations in latent class and latent transition analysis. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 22(2), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.935844

- Aung, M. N., Koyanagi, Y., Ueno, S., Tiraphat, S., & Yuasa, M. (2022). Age-friendly environment and community-based social innovation in Japan: A mixed-method study. The Gerontologist, 62(1), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab121

- Bergman, L. R., Magnusson, D., & El-Khouri, B. M. (2003). Studying individual development in an interindividual context. A person-oriented approach (Vol. 4) Psychology Press.

- Brosschot, J. F., Verkuil, B., & Thayer, J. F. (2017). Exposed to events that never happen: Generalized unsafety, the default stress response, and prolonged autonomic activity. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 74(Pt B), 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.019

- Brosschot, J. F., Verkuil, B., & Thayer, J. F. (2018). Generalized unsafety theory of stress: Unsafe environments and conditions, and the default stress response. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(3), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030464

- Clegg, A., Young, J., Iliffe, S., Rikkert, M. O., & Rockwood, K. (2013). Frailty in elderly people. Lancet (London, England), 381(9868), 752–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)62167-9

- Davey, A., Malmberg, B., & Sundström, G. (2014). Aging in Sweden: Local variation, local control. The Gerontologist, 54(4), 525–532. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt124

- De Donder, L., De Witte, N., Buffel, T., Dury, S., & Verté, D. (2012). Social capital and feelings of unsafety in later life. Research on Aging, 34(4), 425–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027511433879

- Diehl, M., & Wahl, H.-W. (2020). The psychology of later life: A contextual perspective. American Psychological Association.

- Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Ejrnæs, A., & Scherg, R. H. (2022). The impact of victimization on feelings of unsafety in different welfare regimes. European Journal of Criminology, 19(6), 1304–1326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370820960025

- Ferguson, S. L., G. Moore, E. W., & Hull, D. M. (2020). Finding latent groups in observed data: A primer on latent profile analysis in Mplus for applied researchers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(5), 458–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419881721

- Fernandez-Ballesteros, R. (2019). The concept of successful aging and related terms. In R. Fernandez-Ballesteros, A. Benetos, & J.-M. Robine (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of successful aging (pp. 6–22). Cambridge University Press.

- Fonseca, A. (2020). Aging in place in Portugal. Ciências e Políticas Públicas/Public Sciences & Policies, 6(2), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.33167/2184-0644.CPP2020.VVIN2/pp.41-58

- Golovchanova, N., Andershed, H., Boersma, K., & Hellfeldt, K. (2022). Perceived reasons of unsafety among independently living older adults in Sweden. Nordic Journal of Criminology, 23(1), 44–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/2578983X.2021.1920756

- Hale, C. (1996). Fear of crime: A review of the literature. International Review of Victimology, 4(2), 79–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/026975809600400201

- Hanslmaier, M. (2013). Crime, fear and subjective well-being: How victimization and street crime affect fear and life satisfaction. European Journal of Criminology, 10(5), 515–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370812474545

- Henson, B., & Reyns, B. W. (2015). The only thing we have to fear is fear itself… and crime: The current state of the fear of crime literature and where it should go next. Sociology Compass, 9(2), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12240

- Hollway, W., & Jefferson, T. (2000). The role of anxiety in the fear of crime. In T. Hope & R. Sparks (Eds.), Crime, risk and insecurity (pp. 31–49). Routledge.

- Kang, S. J., & Seo, W. (2020). The effects of multilayered disorder characteristics on fear of crime in Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249174

- Killias, M., & Clerici, C. (2000). Different measures of vulnerability in their relation to different dimensions of fear of crime. The British Journal of Criminology, 40, 437–450.

- Köber, G., Oberwittler, D., & Wickes, R. (2022). Old age and fear of crime: Cross-national evidence for a decreased impact of neighbourhood disadvantage in older age. Ageing and Society, 42(7), 1629–1658. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20001683

- Kuin, Y., & Spaans, H.-P. (2017). Emotie en stemming. In M. Vink, Y. Kuin, G. Westerhof, S. Lamers, & A. M. Pot (Eds.), Handboek ouderenpsychologie (2nd ed., pp. 83–122). De Tijdstroom.

- Lenze, E. J., & Wetherell, J. L. (2011). A lifespan view of anxiety disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13(4), 381–399. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.4/elenze

- Márquez González, M., Cheng, S.-T., & Losada, A. (2019). Coping mechanisms through successful aging. In R. Fernández-Ballesteros, A. Benetos, & J.-M. Robine (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of successful aging. Cambridge University Press.

- Mathis, A., Rooks, R., & Kruger, D. (2015). Improving the neighborhood environment for urban older adults: Social context and self-rated health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(1), ijerph13010003. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13010003

- McKee, K. J., & Milner, C. (2000). Health, fear of crime and psychosocial functioning in older people. Journal of Health Psychology, 5(4), 473–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910530000500406

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide. Muthén & Muthén.

- Olofsson, N., Lindqvist, K., & Danielsson, I. (2012). Fear of crime and psychological and physical abuse associated with ill health in a Swedish population aged 65–84 years. Public Health, 126(4), 358–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2012.01.015

- Oswald, F., Jopp, D., Rott, C., & Wahl, H. W. (2011). Is aging in place a resource for or risk to life satisfaction? The Gerontologist, 51(2), 238–250. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnq096

- Rader, N. E., Cossman, J. S., & Porter, J. R. (2012). Fear of crime and vulnerability: Using a national sample of Americans to examine two competing paradigms. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(2), 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2012.02.003

- Schuurmans, H., Steverink, N., Lindenberg, S., Frieswijk, N., & Slaets, J. P. J. (2004). Old or frail: What tells us more?. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 59A(9), 962–965.

- Stafford, M., Chandola, T., & Marmot, M. (2007). Association between fear of crime and mental health and physical functioning. American Journal of Public Health, 97(11), 2076–2081. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH

- Steverink, N., Slaets, J. P. J., Schuurmans, H., & Van Lis, M. (2001). Measuring frailty: Developing and testing the GFI (Groningen Frailty Indicator). The Gerontologist, 41, 236.

- Velasquez, A. J., Douglas, J. A., Guo, F., & Robinette, J. W. (2021). What predicts how safe people feel in their neighborhoods and does it depend on functional status? SSM—Population Health, 16, 100927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100927

- Visser, M., Scholte, M., & Scheepers, P. (2013). Fear of crime and feelings of unsafety in European countries: Macro and micro explanations in cross-national perspective. The Sociological Quarterly, 54(2), 278–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/tsq.12020

- Wahl, H.-W., & Gitlin, L. N. (2019). Linking the socio-physical environment to successful aging: From basic research to interventino to implementation science considerations. In R. Fernandez-Ballesteros, A. Benetos, & J.-M. Robine (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of successful aging (pp. 570–593). Cambridge University Press.

- Wang, J., & Wang, X. (2020). Structural equation modeling. Applications using Mplus (2nd ed.) Wiley.

- Won, J., Lee, C., Forjuoh, S. N., & Ory, M. G. (2016). Neighborhood safety factors associated with older adults’ health-related outcomes: A systematic literature review. Social Science & Medicine, 165, 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.024

- World Health Organization. (2002). Active ageing: A policy framework [No. WHO/NMH/NPH/02.8]. World Health Organization.

- Zhang, K., Wu, B., & Zhang, W. (2022). Perceived neighborhood conditions, self-management abilities, and psychological well-being among Chinese older adults in Hawai’i. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(4), 1111–1119. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648211030072

- Zijlstra, G. A., van Haastregt, J. C., van Eijk, J. T., van Rossum, E., Stalenhoef, P. A., & Kempen, G. I. (2007). Prevalence and correlates of fear of falling, and associated avoidance of activity in the general population of community-living older people. Age and Ageing, 36(3), 304–309. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afm021

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta psychiatrica scandinavica, 67(6), 361-370.

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2